ABSTRACT.

Sporotrichosis is usually a subcutaneous infection caused by thermodimorphic fungi of the genus Sporothrix. The disease occurs worldwide, but endemic areas are located in tropical and subtropical regions. The epidemiology of sporotrichosis in Brazil is peculiar because of the cat’s entry in the chain of transmission of this mycosis, associated with Sporothrix brasiliensis, the most virulent species in the genus. Sinusitis caused by Sporothrix species is unusual and may be underdiagnosed or confused with other fungal etiologies, like mucormycosis. We report a case of sinusitis due to a Sporothrix species in a 6-year renal transplant recipient. Direct examination of smears of exudate of the sinus specimen (aspirate, biopsy) revealed budding yeasts and cigar-shaped cells. Sporothrix was subsequently recovered from the patient’s exudate culture and identified as S. brasiliensis using species-specific polymerase chain reaction, and she was successfully treated with antifungal therapy. Her parents also developed the disease a week later, both only cutaneous involvement. Sporotrichosis sinusitis is a rare disease, even in immunocompromised patients. Diagnosis is crucial, and benefits from good epidemiological history.

CASE PRESENTATION

We report a case of a 38-year-old female type 1 diabetic kidney transplant recipient who presented to the emergency service in November 2019 with acute facial pain, headache, mild cough, and nasal obstruction for 3 days. No fever or skin lesions were related. The patient had undergone a deceased donor renal transplant 6 years prior, and her immunosuppression regimen included tacrolimus, sirolimus, and prednisone. She had a history of several hospitalizations for urinary tract, skin, and soft tissue infections. The patient is a veterinarian but has not exercised her profession for many years. She lives in São Paulo and has several pet cats, with close contact also sharing bed, one of which died of sporotrichosis 2 weeks before the hospitalization.

After an initial evaluation, the patient was admitted for intravenous antibiotics. There was no leukocytosis or increase of C-reactive protein (CRP). Blood cultures later came negative, and symptoms did not improve after 14 days of treatment.

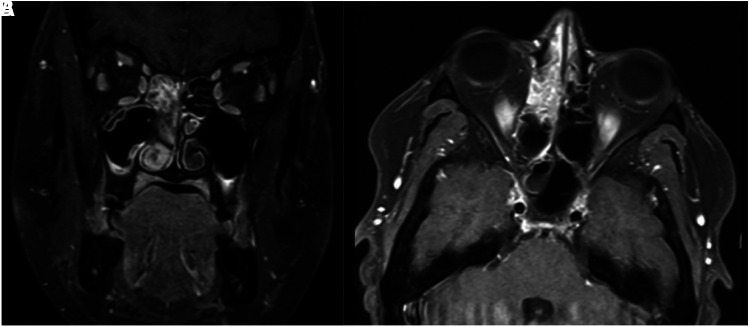

Nasopharyngoscopy evaluation revealed purulent discharge and crusts, with no mass or polyps. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed mucosal thickness and a soft tissue mass filling both maxillary sinuses, mainly at the right. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also showed thickening and enhancement of the paranasal and maxillary sinuses, protruding to the right (Figure 1). As facial pain and mucopurulent discharge worsened, antifungal therapy with 7 mg/kg/day of liposomal amphotericin B was added to treat presumptive mucormycosis, and the patient underwent sinusectomy. Histopathological analysis showed chronic granuloma formation with no yeasts visualized with Grocott’s methenamine silver stain. Because of the worsening of renal function with the need for hemodialysis, liposomal amphotericin was switched to posaconazole, and sirolimus was discontinued. After 10 days of antifungal therapy, we received the sinus culture results, in which grew Sporothrix species. Here, we applied a species-specific PCR assay to identify medically relevant Sporothrix species based on sequence polymorphisms from the calmodulin gene as previously described.1 The amplification of a single band of 469 bp using the primers Sbra-F and Sbra-R identified both isolates as S. brasiliensis. Additionally, molecular characterization of the mating-type locus revealed that the isolate harbors a MAT 1-2, the same genotype that emerged in the outbreak in Rio de Janeiro.1

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance images showing thickening and enhancement of the paranasal and maxillary sinuses, protruding to the right. (A) Coronal section. (B) Axial section.

After 2 months of posaconazole therapy, symptoms improved, and nasopharyngoscopy showed no lesions. She was discharged on oral itraconazole therapy, to be used for 10 more months. One month after discharge, the renal function improved and hemodialysis was stopped. The patient had two hospitalizations for another reason, and after the itraconazole treatment she was seen in the outpatient clinic. No symptoms or relapse have been related.

Two weeks before admission, her cat died of sporotrichosis despite treatment with itraconazole. She also has a dog that developed the disease and was also treated with itraconazole with full recovery. One week after the patient’s hospital admission, her father, a 70-year-old man with a medical history of type 1 diabetes, developed the lymphocutaneous form of sporotrichosis, and her mother, a 64-year-old obese woman, presented the fixed cutaneous form. Both parents had contact with the affected animals and were both treated with itraconazole.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first case of rhinosinusitis caused by a Sporothrix species in a kidney transplant recipient reported in the literature. Moreover, the first case of rhinosinusitis caused by S. brasiliensis, a species responsible for epizooties in domestic cats and consequently massive zoonotic transmission to humans since the 2000s.2

Acute rhinosinusitis is a common infection in adults, accounting for more than 1 in 5 antibiotic prescriptions in the United States. Bacteria and viruses are the most frequent cause of rhinosinusitis, but fungi have been increasingly recognized as emerging agents, especially in tropical areas.3

Fungal rhinosinusitis comprises a spectrum of disease processes, which vary in clinical presentation, histologic appearances, and biological significance, probably depending on the variety of host interactions and mechanism of fungal tissue invasion.4 Aspergillus spp. is the most common agent, but other fungal species such as Cryptococcus spp., Candida spp., Mucorales, Fusarium spp., and Scedosporium spp. have been reported, mainly in HIV-AIDS patients.4,5

Sporotrichosis is caused by the dimorphic fungus of the genus Sporothrix, first isolated in 1898. In Latin America, sporotrichosis is the most frequent subcutaneous mycosis and has emerged as a significant fungal infection over the last two decades.6 The estimated prevalence rates of sporotrichosis range from 0.5% to 1% in Brazil.7,8 Most of the registered cases in Brazil are concentrated in Rio de Janeiro, and it is a significant cause of hospitalization in the state.9,10

Sporothrix spp. lives saprophytically in nature, usually associated with plants, and can be isolated from soil and plants. It is usually an occupational disease affecting miners, forestry workers, gardeners, and florists. Some animals have been associated with the zoonotic transmission of sporotrichosis.

There are two important disease transmission routes for humans in Brazil, a sapronotic route involving direct contact with the soil and decomposing organic matter; and a zoonotic route, through cats. Feline sporotrichosis is unique among infections caused by endemic dimorphic fungi because it is directly transmitted in the yeast phase. The feline lesions typically harbor a high yeast-like fungal burden that can be acquired via cat scratches and bites, by nontraumatic ways, such as a cat’s cough or sneezing, and direct contact between patients integumental barriers and animal secretions.6 Sporothrix brasiliensis, the most virulent species of the genus, is the primary agent of zoonotic sporotrichosis in Brazil.10

The virulence profiles change depends on the pathogen characteristics and the host defenses. The average incubation time is 3 weeks. It is usually a cutaneous or subcutaneous infection but can progress to lymphatics, fascia, muscles, cartilage, and bones. It is associated with morbidity but rarely associated with mortality. The disease may evolve into different clinical forms, cellular and humoral immune responses, mode of inoculation, and fungal virulence appear to interfere with the clinical form of the disease.11

In this case, the decreased cellular and humoral immune response of the patient due to the use of immunosuppressive agents, diabetes, and the intimal contact with the cat appear to be determinant to the clinical presentation. The transmission route was probably from inhalation of Sporothrix propagules and posterior spread to paranasal sinus mucosa and bone.12 mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitors, such as sirolimus taken by the patient, and tacrolimus suppress T-cell proliferation.13,14 Decreased chemotaxis, phagocytic, and killing activities of macrophages and neutrophils were described in uncontrolled diabetic patients.15

Fungal rhinosinusitis related to Sporothrix spp. is very uncommon and remains anecdotal as only six reports have been published between 1963 and 2016. In these six reports, four involved immunocompetent patients,12,16–18 while the other, patients that were immunocompromised: diabetes,19 HIV,20 hematological neoplasias, and use of steroids.18 Pulmonary involvement seems to be more common, there are several related cases, and it was suggested that the infection occurred through inhalation of the fungal conidia as well, usually in immunocompromised patients.21,22 What would make the fungus establishes a sinus or pulmonary infection is not known.

Opportunistic infections are common in organ transplant patients, where fungal infections comprise approximately 5% of all infections, mostly by Candida species, Aspergillus species, and Cryptococcus neoformans complex.23 There are few cases reported of sporotrichosis in transplant recipients.23–36 Most of them in kidney transplant patients,23–25,28,29,33,34 and disseminated, as pulmonary and cerebral involvement, as shown in Table 1. Among solid organ transplant patients, sporotrichosis has been mostly reported in kidney transplantation, probably because it is the most frequent organ transplant carried out worldwide. To our knowledge, no case of sporotrichosis with sinusitis in a kidney transplant patient was described.

Table 1.

Cases of sporotrichosis in renal transplant recipients previously reported

| Author/year | Age, years/gender | Clinical manifestation | Time after transplantation | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gullberg et al., 1987 | 50/male | Cutaneous, osteoarticular, neurological | 4 years | AMB-d |

| Agarwal et al., 1994 | 23/male | Urinary tract | 9 months | None |

| Rao et al., 2002 | 49/female | Nasal mucosa | 6 months | None |

| Caroti et al., 2010 | 59/male | Cutaneous, osteoarticular | Unknown | FLZ |

| Gewehr et al., 2013 | 48/female | Cutaneous | 9 months | AMB-L, ITZ |

| 53/male | Cutaneous, osteoarticular | 1 month | AMB-L, ITZ | |

| Amirali et al., 2020 | 43/male | Cutaneous | 10 years | ITZ |

| 56/male | Neurological, pulmonary | 17 years | AMB-d; ITZ | |

| Fichman et al., 2020 | 41/female | Cutaneous, oral, and nasal mucosa | Unknown | AMB-d, AMB-L, ITZ, TRB |

| 34/male | lymphocutaneous | Unknown | TRB+ITZ | |

| 51/male | lymphocutaneous | Unknown | TRB | |

| 43/male | Cutaneous, oral, and nasal mucosa, osteoarticular | Unknown | AMB-L, ITZ | |

| 42/male | lymphocutaneous | Unknown | ITZ | |

| 54/male | lymphocutaneous | Unknown | TRB |

AMB-d = amphotericin B; AMB-L = liposomal amphotericin B; FLZ = fluconazole; ITZ = itraconazole; TRB = terbinafine.

Azotemia occurs in 80% of patients who receive amphotericin for deep mycoses, with dose-dependent toxicity, the lipid formulation is less nephrotoxicity and should be preferred in kidney transplant patients.37 Nevertheless, unfortunately, our patient required dialysis even after receiving the lipid formulation.

Because sinusitis sporotrichosis in the immunocompromised patient can have an extended incubation period and may go undiagnosed for a long time before worsening symptoms, its diagnosis remains challenging. The gold standard and the most reliable laboratory tool is the culture since serology is often not available. Moreover, the clinical presentation is atypical for Sporothrix spp., and no clinical distinction from sinusitis caused by other microbial and fungus agents, a broad differential diagnosis. Treatment consists of long-term use of antifungal drugs such as terbinafine, itraconazole, posaconazole, or amphotericin B. There are no clinical trials to guide therapy for disseminated sporotrichosis in immunosuppressed hosts, and some cases need life-long suppressive therapy.38

In conclusion, sinusitis sporotrichosis is a rare condition, and therefore the absence of specific symptoms can lead to possible confusion with other opportunistic agents, mainly in immunocompromised hosts. Therefore, the epidemiological history and biological confirmation are essential for the correct diagnosis.

REFERENCES

- 1. Teixeira Me M. et al. , 2015. Asexual propagation of a virulent clone complex in a human and feline outbreak of sporotrichosis. Eukaryot Cell 14: 158–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rodrigues AM, Della Terra PP, Gremiao ID, Pereira SA, Orofino-Costa R, de Camargo ZP, 2020. The threat of emerging and re-emerging pathogenic Sporothrix species. Mycopathologia 185: 813–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rosenfeld RM. et al. , 2015. Clinical practice guideline (update): adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 152: S1–S39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Montone KT, 2016. Pathology of fungal rhinosinusitis: a review. Head Neck Pathol 10: 40–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thompson GR, Patterson TF, 2012. Fungal disease of the nose and paranasal sinuses. J Allergy Clin Immunol 129: 321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chakrabarti A, Bonifaz A, Gutierrez-Galhardo MC, Mochizuki T, Li S, 2015. Global epidemiology of sporotrichosis. Med Mycol 53: 3–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Queiroz-Telles F, Nucci M, Colombo AL, Tobón A, Restrepo A, 2011. Mycoses of implantation in Latin America: an overview of epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Med Mycol 49: 225–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Conti Diaz IA, 1989. Epidemiology of sporotrichosis in Latin America. Mycopathologia 108: 113–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Silva MB, Costa MM, Torres CC, Galhardo MC, Valle AC, Magalhães Me A, Sabroza PC, Oliveira RM, 2012. Urban sporotrichosis: a neglected epidemic in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica 28: 1867–1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Freitas DF. et al. , 2012. Sporotrichosis in HIV-infected patients: report of 21 cases of endemic sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Med Mycol 50: 170–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Queiroz-Telles F, Buccheri R, Benard G, 2019. Sporotrichosis in immunocompromised hosts. J Fungi (Basel) 5: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mitra AN, Das S, Sinha R, Aggarwal N, Chakravorty S, 2016. Sporotrichosis of maxillary sinuses in a middle aged female patient from rural area of eastern India. J Clin Diagn Res 10: DD01–DD02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Iijima Y, Fujioka N, Uchida Y, Kobayashi Y, Tsutsui T, Kakizaki Y, Miyashita Y, 2018. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis mimicking organizing pneumonia after mTOR inhibitor therapy: a case report. Int J Infect Dis 69: 75–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Group KDIGOKTW , 2009. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 9 (Suppl 3): S1–S155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Geerlings SE, Hoepelman AI, 1999. Immune dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM). FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 26: 259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Haufe F, Osswald M, 1963. Atypical course of maxillary sinusitis caused by Sporotrichum schenckii . Z Arztl Fortbild (Jena) 57: 79–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Friedman SJ, Doyle JA, 1983. Extracutaneous sporotrichosis. Int J Dermatol 22: 171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morgan MA, Wilson WR, Neel HB, Roberts GD, 1984. Fungal sinusitis in healthy and immunocompromised individuals. Am J Clin Pathol 82: 597–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Agger WA, Caplan RH, Maki DG, 1978. Ocular sporotrichosis mimicking mucormycosis in a diabetic. Ann Ophthalmol 10: 767–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morgan M, Reves R, 1996. Invasive sinusitis due to Sporothrix schenckii in a patient with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis 23: 1319–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aung AK, Teh BM, McGrath C, Thompson PJ, 2013. Pulmonary sporotrichosis: case series and systematic analysis of literature on clinico-radiological patterns and management outcomes. Med Mycol 51: 534–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Callens SF, Kitetele F, Lukun P, Lelo P, Van Rie A, Behets F, Colebunders R, 2006. Pulmonary Sporothrix schenckii infection in a HIV positive child. J Trop Pediatr 52: 144–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Amirali MH, Liebenberg J, Pillay S, Nel J, 2020. Sporotrichosis in renal transplant patients: two case reports and a review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 14: 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guimarães LF, Halpern M, de Lemos AS, de Gouvêa EF, Gonçalves RT, da Rosa Santos MA, Nucci M, Santoro-Lopes G, 2016. Invasive fungal disease in renal transplant recipients at a Brazilian center: local epidemiology matters. Transplant Proc 48: 2306–2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Caroti L, Zanazzi M, Rogasi P, Fantoni E, Farsetti S, Rosso G, Bertoni E, Salvadori M, 2010. Subcutaneous nodules and infectious complications in renal allograft recipients. Transplant Proc 42: 1146–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arantes Ferreira GS, Watanabe ALC, Trevizoli NC, Jorge FMF, Cajá GON, Diaz LGG, Meireles LP, Araújo MCCL, 2019. Disseminated sporotrichosis in a liver transplant patient: a case report. Transplant Proc 51: 1621–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tambini R, Farina C, Fiocchi R, Dupont B, Guého E, Delvecchio G, Mamprin F, Gavazzeni G, 1996. Possible pathogenic role for Sporothrix cyanescens isolated from a lung lesion in a heart transplant patient. J Med Vet Mycol 34: 195–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gullberg RM, Quintanilla A, Levin ML, Williams J, Phair JP, 1987. Sporotrichosis: recurrent cutaneous, articular, and central nervous system infection in a renal transplant recipient. Rev Infect Dis 9: 369–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rao KH, Jha R, Narayan G, Sinha S, 2002. Opportunistic infections following renal transplantation. Indian J Med Microbiol 20: 47–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. da Silva RF, Bonfitto M, da Silva Junior FIM, de Ameida MTG, da Silva RC, 2017. Sporotrichosis in a liver transplant patient: a case report and literature review. Med Mycol Case Rep 17: 25–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bahr NC, Janssen K, Billings J, Loor G, Green JS, 2015. Respiratory failure due to possible donor-derived Sporothrix schenckii infection in a lung transplant recipient. Case Rep Infect Dis 2015: 925718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Morrison AS, Lockhart SR, Bromley JG, Kim JY, Burd EM, 2013. An environmental Sporothrix as a cause of corneal ulcer. Med Mycol Case Rep 2: 88–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gewehr P, Jung B, Aquino V, Manfro RC, Spuldaro F, Rosa RG, Goldani LZ, 2013. Sporotrichosis in renal transplant patients. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 24: e47–e49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fichman V, Marques de Macedo P, Francis Saraiva Freitas D, Carlos Francesconi do Valle A, Almeida-Silva F, Reis Bernardes-Engemann A, Zancopé-Oliveira RM, Almeida-Paes R, Clara Gutierrez-Galhardo M, 2020. Zoonotic sporotrichosis in renal transplant recipients from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Transpl Infect Dis 23: e13485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Agarwal SK, Tiwari SC, Dash SC, Mehta SN, Saxena S, Banerjee U, Kumar R, Bhunyan UN, 1994. Urinary sporotrichosis in a renal allograft recipient. Nephron 66: 485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kramer MR, Marshall SE, Denning DW, Keogh AM, Tucker RM, Galgiani JN, Lewiston NJ, Stevens DA, Theodore J, 1990. Cyclosporine and itraconazole interaction in heart and lung transplant recipients. Ann Intern Med 113: 327–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Laniado-Laborín R, Cabrales-Vargas MN, 2009. Amphotericin B: side effects and toxicity. Rev Iberoam Micol 26: 223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kauffman CA, Bustamante B, Chapman SW, Pappas PG, America IDSo , 2007. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of sporotrichosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 45: 1255–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]