ABSTRACT.

This study aimed to determine the occurrence of antibiotic resistance genes for β-lactamases; blaTEM and blaCTX-M in uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates from urinary tract infection (UTI) suspected diabetic and nondiabetic patients. A hospital-based cross-sectional study was conducted in Kathmandu Model Hospital, Kathmandu, in association with the Department of Microbiology, GoldenGate International College, Kathmandu, Nepal, from June to December 2018. A total of 1,267 nonduplicate midstream urine specimens were obtained and processed immediately for isolation of uropathogens. The isolates were subjected to antibiotic susceptibility testing and extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) confirmation. In addition, blaTEM and blaCTX-M genes were detected using specific primers. The overall prevalence of UTI was 17.2% (218/1,267), of which patients with diabetes were significantly more infected; 32.3% (31/96) as compared with nonpatients with diabetes, 15.9% (187/1,171). A total of 221 bacterial isolates were obtained from 218 culture-positive specimens in which E. coli was the most predominant; 67.9% (150/221). Forty-four percent (66/150) of the total E. coli was multidrug resistant and 37.3% (56/150) were ESBL producers. Among 56 isolates, 92.3% (12/13) were from patients with diabetes, and 83.0% (44/53) were from nondiabetics. Furthermore, 84.9% of the screened ESBL producers were confirmed to possess either single or both of blaTEM and blaCTX-M genes. The blaTEM and blaCTX-M genes were detected in 53.6% and 87.5% of the phenotypically ESBL confirmed E. coli, respectively. Higher rates of ESBL producing uropathogenic E. coli are associated among patients with diabetes causing an alarming situation for disease management. However, second-line drugs with broad antimicrobial properties are still found to be effective drugs for multidrug resistance strains.

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is an emerging chronic noninfectious disease characterized by hyperglycemia that occurs as a result of insufficient production of insulin from the pancreas. Of the top 10 diseases with higher mortality, diabetes caused around four million deaths worldwide in 2017 among adults.1 Patient with diabetes is highly susceptible to infectious diseases most frequently by urinary tract infection (UTI). The major predisposing factors for UTI among patients with diabetes are impairment of the immune system, poor metabolic control, and incomplete bladder emptying because of autonomic neuropathy.2–4 Older age is another crucial influencing factor to enhance the risk of UTI among patients with diabetes.5,6

UTI involves the invasion of microbes, and their multiplication and colonization in genito-urinary organs.7 The degree of UTI among patients with diabetes ranges from asymptomatic infection to various severe lower UTI including cystitis, pyelonephritis, and urosepsis.8 UTI also remains a widespread nosocomial infection and is commonly diagnosed among outpatients and inpatients.9,10 Escherichia coli is the most dominant bacteria causing UTI followed by other members of Enterobacteriaceae; Klebsiella pneumoniae, Citrobacter spp., Proteus spp., Enterobacter spp. And so on.9,11,12 Recently, the rapid widespread of multidrug resistance (MDR) bacteria has been a major public health problem especially caused by β-lactamases producing MDR strains. The production of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) has helped bacteria to expand their activity even against the newly developed β-lactam antibiotics.13 ESBL producing microorganisms pose tremendous therapeutic consequences and significant clinical challenges when they remain undetected. They confer decreased susceptibility to narrow- and expanded-spectrum cephalosporins and monobactams but do not affect cephamycin and carbapenem compounds.14 They are usually resistant to fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and co-trimoxazole.15,16 Besides mutations in chromosomal genes that result in the development of an intrinsic resistance mechanism, the bacteria from the Enterobacteriaceae family commonly bear mobile genetic elements carrying resistant genes mainly plasmid-encoding β-lactamases and aminoglycosides-modifying enzymes.17 In addition, the nonenzymatic mechanisms such as Qnr (several qnr genes) for fluoroquinolones are frequently present in these bacteria.17,18 These plasmids are not only responsible for multiple resistant determinants but also horizontally transfer to other pathogens during congujation.17 More than 300 different ESBL variants have been identified. TEM and SHV being the major types with increasing occurrence of CTX-M enzymes.19,20 Almost all Enterobacteriaceae harbor ESBL with a higher prevalence among E. coli isolates in community-acquired infections.

The increased risk of UTI among patients with diabetes and enhanced urinary complications related to MDR strains may pose high morbidity and mortality rates. Therefore, screening for UTI and their causative agents among patients with diabetes is crucial to properly treat infections. Moreover, identifying the exact drug resistance pattern is equally important to managing the disease and further preventing the development of urinary-related complications among patients with diabetes.21,22 Hence, the study aimed to evaluate microbiological agents and their resistance patterns by both phenotypic and genotypic methods associated with UTI in patients with diabetes and nondiabetics. The results of the study had also suggested the need for differential antimicrobial treatment of infections in diabetic and nondiabetic patients to minimize the increased risk of mortality and morbidity of diabetic patients because of urinary tract infections. Through the literature review, TEM and CTX were found to be the most common genes among E. coli. SHV was detected at a lower percentage in our review.23,24 The percentage of SHV was also found very low in the recent study by Pandit et al.25 Many studies reported a higher occurrence of SHV gene in Klebsiella spp. Because the number of Klebsiella isolated in this study was very few compared with E. coli, we conducted our study using two predominant genes of ESBL; blaTEM and blaCTX-M genes among uropathogenic E. coli isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design, duration, and site.

A hospital-based cross-sectional study was conducted from June 20 to December 2018, among the clinically suspected patients with UTI patients visiting the hospital. The urine sample processing was followed by identifying uropathogens in the Microbiology Laboratory of Kathmandu Model Hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal, while extracting nucleic and amplifying ESBL-specific genes using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were performed in the Department of Microbiology, GoldenGate International College, Kathmandu.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

This study included patients of both sexes and all age groups attending the hospital with suspicion of UTI. Patients attending the hospital during the study period providing consent to participate in this study were enrolled. Samples that were adequately collected and properly labeled, were included in the study. Those samples that were not collected with standard collection procedure, inadequately collected, improperly labeled, and samples with visible contamination were excluded from the study. A repeated sample was requested in such cases. The urine samples from patients whose health status was not mentioned as diabetic and nondiabetic and those who were taking antibiotics less than 24 hours at the time of hospital visit were also excluded.

Study variables.

The study variables: age, sex, outpatient, inpatient, the health status of patients: diabetic or nondiabetic, and the history of taking antibiotics within 24 hours at the time of attending the hospital were obtained using a standard data form assigned by the hospital. The medical status of patients (diabetic or non-diabetic) was confirmed by a physician based on the blood glucose level.

Sample size.

Consent for participation was collected from all participants during enrolment and before data and sample collection. Patients with UTI or suspected patients were instructed to collect midstream urine (MSU) samples in sterile, clean, and leakproof vials. A total of 1,267 nonduplicate MSU specimens were obtained and processed immediately in the Microbiology Laboratory of Kathmandu Model Hospital.

Sample processing.

The urine samples were cultured onto the Cysteine Lactose Electrolyte Deficient (CLED) agar by the semiquantitative culture technique using a standard calibrated loop.26 The agar plates were incubated at 37°C overnight. Bacteria developed in pure culture with a load greater than 105 CFU/mL were considered as significant growth. The bacteria were identified by standard microbiological procedures including microscopy, colony microbiology, and biochemical tests as described by Isenberg 2004.27 Among different bacterial isolates, only E. coli isolates were further processed for molecular studies.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Susceptibility tests of the bacterial isolates toward various antibiotics were performed by the modified Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method using Mueller Hinton Agar.28 Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as the control strain. Antibiotics such as amoxicillin (10 µg), cefixime (5 µg), co-trimoxazole (25 µg), cefotaxime (30 µg), ceftazidime (30 µg), ceftriaxone (30 µg), gentamicin (10 µg), levofloxacin (5 µg), ofloxacin (5 µg), norfloxacin (5 µg), and nitrofurantoin (300 µg) were used in the primary testing. For MDR isolates, amikacin (30 µg), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (20/10 µg), cefoperazone/sulbactam (75/30 µg), cefepime (50 µg), doxycycline (30 µg), imipenem (10 µg), meropenem (10 µg), and piperacillin/tazobactam (100/10 µg) were used for further testing. In addition, polymyxin B (300 µg), colistin (10 µg), and tigecycline (15 µg) were used for 14 bacterial isolates for preliminary screening. The resistant strains were confirmed by the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) method following Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) guidelines.28 Escherichia coli isolates that are nonsusceptible to at least 1 agent in ≥ 3 antimicrobial categories are considered as MDR E. coli.29 Subsequently, the rate of MDR E. coli was determined.

Phenotypic characterization of the ESBL producers.

Escherichia coli isolates were screened for possible ESBL production using ceftazidime (30 µg) and cefotaxime (30 µg). The suspected ESBL producing E. coli were subjected to combined disk (CD) assay using ceftazidime (30 µg) with ceftazidime plus clavulanic acid (30/10 µg) and cefotaxime (30 µg) with cefotaxime plus clavulanic acid (30/10 µg) for phenotypic confirmation.30

Detection of blaTEM and blaCTX-M genes.

Plasmid DNA was extracted from phenotypically confirmed ESBL producing E. coli using the alkaline lysis method followed by the phenol: chloroform purification method.31,32 Conventional linear PCR was used to amplify the blaTEM and blaCTX-M genes in the extracted plasmid DNA. The blaTEM gene was amplified using a set of forward primer of sequence 5′-GAGACAATAAGGGTGGTAAAT-3′ and reverse primer of nucleotide sequence 5′-AGAAGTAAGTTGGCAGCAGTG-3′.33 Similarly, the blaCTX-M gene was amplified using a forward primer of sequence 5′-TTTGCGATGTGCAGTACCAGTAA-3′ and a reverse primer of nucleotide sequence 5′-CTCCGCCTGCCGGTTTTAT-3′. The master mix containing 200 µM of dNTPs, 0.5 U/µL of Taq polymerase in 1X PCR buffer, and 25 mM MgCl2 from Qiagen was used.34 The PCR was performed in a final volume of 25 µL prepared by mixing the 13 µL of the master mix, 8 µL of the double-distilled water, 0.5 µL each of the forward and reverse primer, and 3 µL of the template DNA. Amplification reactions were performed using the PCR reaction conditions of initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 minutes; followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 45 seconds, annealing at 55°C for blaTEM genes and 56°C for the blaCTX-M gene for 30 seconds, extension at 72°C for 3 minutes and a final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes. The PCR products were analyzed on 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis with 0.2 µg/mL concentration of ethidium bromide and then visualized by UV-trans illuminator. The protocol from Sharma et al. and Edelstein et al. were followed with slight modification.33,34

Quality control.

Escherichia coli ATCC 35218 and E. coli ATCC 25922 were obtained from the Central Department of Microbiology, Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, and used as a positive control for the screening of blaTEM and blaCTX-M genes and a negative control strain, respectively.

Data analysis.

All data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) Software (Version 22.0) and MS Excel (Version 10).

RESULTS

Bacterial growth profile.

Among the 1,267 MSU specimens, 17.2% (218/1,267) of specimens showed significant growth. Of the 218 significant cases of bacterial growth, 22.0% (48/218) were from males and 77.9% (170/218) were from females. The prevalence of UTI was found to be significantly higher among females in the age group 21–40 (P < 0.001) (Table 1). Likewise, a significantly higher percent of diabetic patients who were infected with UTI accounting for 32.3% (31/96) as compared with nondiabetics, 15.9% (187/1,171) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Bacterial growth profile based on gender and age groups

| Age groups (years) |

Gender | Total bacterial growth (%) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | Female (%) | |||

| 1–20 | 10 (34.48) | 19 (65.52) | 29 (13.30) | – |

| 21–40 | 10 (10.30) | 87 (89.70) | 97 (44.49) | 0.001 |

| 41–60 | 9 (23.07) | 30 (76.93) | 39 (17.9) | – |

| > 60 | 19 (35.85) | 34 (64.15) | 53 (24.31) | – |

| Total | 48 (22.02) | 170 (77.98) | 218 | – |

Table 2.

Bacterial growth profile based on medical status (diabetic and out/inpatients)

| Medical status | Growth | Total number | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not significant (%) | Significant (%) | |||

| Nondiabetic | 984 (84.03) | 187 (15.97) | 1,171 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetic | 65 (67.71) | 31 (32.29) | 96 | |

| Total | 1,049 | 218 | 1,267 | – |

| Outpatients | 966 (83.35) | 193 (16.65) | 1,159 | 0.087 |

| Inpatients | 83 (76.85) | 25 (23.15) | 108 | |

| Total | 1,049 | 218 | 1,267 | – |

Frequency of uropathogenic bacteria.

A total of 221 bacteria were isolated from 218 culture-positive specimens in which 215 (98.6%) specimens showed monobacterial infection and polymicrobial infection was observed in 3 (1.4%) samples. Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial isolates comprised 89.1% (197/221) and 10.9% (24/221) respectively. Escherichia coli was the most predominant Gram-negative bacteria accounting for 67.9% followed by K. pneumoniae (14.9%). In other hand, Staphylococcus saprophyticus was the most frequently isolated pathogen followed by Enterococcus faecalis. Escherichia coli was found to be the most predominant bacteria in both patients with diabetes (67.2%) and nondiabetics (71.9%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Distribution of bacterial isolates from specimens of diabetic and nondiabetic

| Bacterial isolates | Nondiabetic patients | Diabetic patients | Total number of bacterial isolates | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Number (%) | |||

| Acinetobacter spp. | 0 | 1 (3.13) | 1 (0.45) | > 0.05 (0.670) |

| Enterobacter aerogens | 2 (1.06) | 0 | 2 (0.9) | |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 6 (3.17) | 0 | 6 (2.71) | |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 6 (3.17) | 1 (3.13) | 7 (3.17) | |

| Escherichia coli | 127 (67.2) | 23 (71.86) | 150 (67.87) | |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | 1 (0.52) | 0 | 1 (0.45) | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 28 (14.81) | 5 (15.63) | 33 (14.93) | |

| Proteus vulgaris | 1 (0.52) | 0 | 1 (0.45) | |

| Proteus mirabilis | 1 (0.52) | 0 | 1 (0.45) | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 2 (1.06) | 0 | 2 (0.9) | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 1 (0.52) | 0 | 1 (0.45) | |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus | 14 (7.40) | 2 (6.25) | 16 (7.24) | |

| Total | 189 | 32 | 221 | – |

Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of E. coli.

The highest number of bacteria was resistant toward amoxicillin and the lowest resistance was observed to nitrofurantoin among E. coli isolates from both diabetic and nondiabetic patients. Among 44 MDR E. coli from nondiabetics, the highest number (86.4%) was resistant to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid and the lowest (13.6%) was resistant to amikacin and carbapenems. Similarly, of 12 MDR E. coli from patients with diabetes, 66.7% of bacteria were resistant to cefepime and 8.3% were resistant to piperacillin/tazobactam and carbapenems (Table 4).

Table 4.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing of Escherichia coli isolates from urine samples

| Antibiotic category | No. of resistant E. coli isolates (%) from | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nondiabetic patients | Diabetic patients | ||

| First-line drugs | Antibiotics used | (N = 127) | (N = 23) |

| Penicillin + β-lactamase inhibitors | Amoxicillin* | 83 (65.35) | 15 (65.22) |

| Extended spectrum cephalosporins; third and fourth generation cephalosporins | Cefixime* | 53 (41.74) | 13 (56.51) |

| Cefotaxime* | 53 (41.74) | 13 (56.51) | |

| Ceftriaxone* | 53 (41.74) | 13 (56.51) | |

| Ceftazidime* | 53 (41.74) | 13 (56.51) | |

| Folate pathway inhibitors | Co-trimoxazole* | 59 (46.46) | 12 (52.17) |

| Aminoglycosides | Gentamicin* | 14 (11.11) | 3 (13.04) |

| Fluoroquinolones | Levofloxacin* | 48 (37.8) | 11 (47.83) |

| Ofloxacin* | 51 (40.16) | 12 (52.17) | |

| Norfloxacin* | 55 (43.3) | 13 (56.51) | |

| Nucleic acid synthesis inhibitors | Nitrofurantoin* | 6 (4.72) | 2 (8.7) |

| Second line drugs | Antibiotics used | (N = 44) | (N = 12) |

| Aminoglycosides | Amikacin* | 6 (13.64) | 0 |

| Penicillin + β-lactamase inhibitors | Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid*a | 38 (86.36) | 7 (58.33) |

| Extended spectrum cephalosporins; 3rd and 4th generation cephalosporins | Cefoperazone/Sulbactam* | 28 (63.64) | 5 (41.67) |

| Cefepime* | 31 (70.45) | 8 (66.67) | |

| Tetracyclines | Doxycycline* | 13 (29.55) | 4 (33.33) |

| Carbapenems | Imipenem* | 6 (13.64) | 1 (8.33) |

| Meropenem* | 6 (13.64) | 1 (8.33) | |

| β-lactamase inhibitors | Piperacillin/Tazobactam* | 8 (18.18) | 1 (8.33) |

| Third-/last line drugs | Antibiotics used | (N = 7) | (N = 3) |

| Polymyxins | Colistin† | 0 | 0 |

| Polymyxin B† | 0 | 0 | |

| Glycylcyclines | Tigecycline† | 0 | 0 |

P value is greater than 0.05 (not significant).

No statistics are computed since the value in colistin, polymyxin B, and tigecycline are constant.

ESBL producing MDR E. coli.

Of the 66 ESBL suspected isolates, 56 were confirmed as ESBL producers. The combination disk using ceftazidime, CAZ (30 µg) with ceftazidime plus clavulanic acid CCAZ [30 µg] + CV [10 µg]) confirmed 52 as ESBL producers wheras cefotaxime, CTX (30 µg) with cefotaxime with clavulanic acid (CTX [30 µg] + CV [10 µg]) showed 56 ESBL producing E. coli. A total of 37.3% (56/150) was considered as the ESBL producers including 92.3% (12/13) from patients with diabetes and 83.0% (44/53) from nondiabetics. Similarly, 87.5% ESBL producing E. coli were isolated from outpatients, whereas 12.5% were isolated from inpatients.

Antimicrobial resistance pattern among non-ESBL and ESBL E. coli.

Among nondiabetics, amoxicillin was the most resisted antibiotic, whereas the least resistance was observed toward nitrofurantoin. Similarly, among patients with diabetes, the non-ESBL E. coli were 100% resistant to gentamicin and nitrofurantoin, whereas the cephalosporins were the least effective antibiotics. The ESBL producing E. coli showed 100% resistance to amoxicillin, whereas the least resistance was found toward nitrofurantoin (Table 5).

Table 5.

Antibiotic resistivity pattern of non-ESBL and ESBL Escherichia coli

| Antibiotics used | Resistance pattern in nondiabetic (%) | Resistance pattern in diabetic (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-ESBL producers | ESBL producers | Non-ESBL producers | ESBL producers | |

| First-line drugs (N = 150) | (N = 83) | (N = 44) | (N = 11) | (N = 12) |

| Amoxicillin* | 39 (46.99) | 44 (100) | 3 (27.27) | 12 (100) |

| Cefixime* | 9 (10.84) | 44 (100) | 1 (9.09) | 12 (100) |

| Co-trimoxazole* | 34 (40.97) | 25 (56.82) | 4 (36.36) | 8 (66.67) |

| Gentamicin† | 9 (10.84) | 5 (11.36) | 0 | 3 (25) |

| Levofloxacin* | 19 (22.89) | 29 (65.9) | 4 (36.36) | 7 (58.33) |

| Ofloxacin* | 20 (24.1) | 31 (70.45) | 4 (36.36) | 8 (66.67) |

| Norfloxacin* | 23 (27.71) | 32 (72.73) | 5 (45.45) | 8 (66.67) |

| Nitrofurantoin* | 2 (2.4) | 4 (9.1) | 0 | 2 (16.67) |

| Second-line drugs (N = 56) | (N = 11) | (N = 33) | (N = 2) | (N = 10) |

| Amikacin† | 5(45.45) | 1 (3.03) | 0 | 0 |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid* | 8 (72.78) | 30 (90.91) | 1 (50) | 6 (60) |

| Cefoperazone/Sulbactam† | 8 (72.78) | 20 (60.61) | 1 (50) | 4 (40) |

| Cefepime* | 7 (63.67) | 24 (72.73) | 1 (50) | 7 (70) |

| Doxycycline† | 6 (54.55) | 7 (21.21) | 1 (50) | 3 (30) |

| Imipenem† | 6 (54.55) | 0 | 1 (50) | 0 |

| Meropenem† | 6 (54.55) | 0 | 1 (50) | 0 |

| Piperacillin/Tazobactam† | 6 (54.55) | 2 (6.06) | 1 (50) | 0 |

ESBL = extended spectrum β-lactamase. The Chi square test was applied between antibiotic susceptibility testing in ESBL producers and non-ESBL producers.

P value is greater than 0.05 (not significant).

P value is less than 0.05 (Gentamicin = 0.019, Amikacin < 0.001, Cefoperazone/Sulbactam = 0.033, Doxycycline = 0.006, Imipenem < 0.001, Meropenem < 0.001 and Piperacillin/Tazobactam < 0.001).

Detection of ESBL genes.

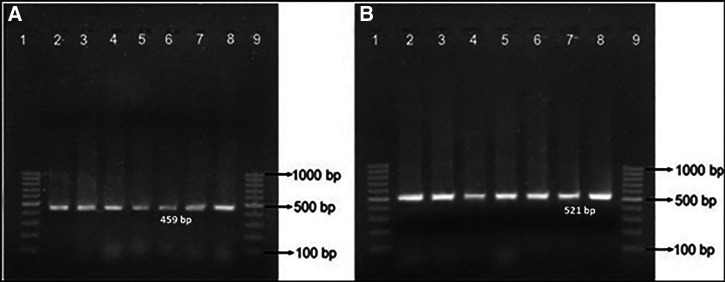

Of the 56 phenotypically confirmed ESBL producing isolates of E. coli, the blaTEM gene was detected in 53.6% of isolates. Similarly, the blaCTX-M gene was detected in 87.5% of E. coli isolates. Both blaTEM and blaCTX-M genes were detected in 50% (Table 6, Figure 1).

Table 6.

Status of ESBL and representative ESBL genes among uropathogenic Escherichia coli from diabetic and nondiabetic patients

| Methods used | ESBL parameters | Number (%) in | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetic | Nondiabetic | |||

| Phenotypic, N = 66 (CD test) | ESBL producer | 12 (92.3) | 44 (83.0) | > 0.05 |

| ESBL non producer | 1 (7.7) | 9 (17.0) | ||

| Total | 13 | 53 | – | |

| Genotypic, N = 56 (blaTEM gene screening) | blaTEM detected | 5 (41.7) | 25 (56.8) | > 0.05 |

| blaTEM not detected | 7 (58.3) | 19 (43.2) | ||

| Total | 12 | 44 | – | |

| Genotypic, N = 56 (blaCTX-M gene screening) | blaCTX-M detected | 10 (83.3) | 39 (88.6) | > 0.05 |

| blaCTX-M not detected | 2 (16.7) | 5 (11.4) | ||

| Total | 12 | 44 | – | |

ESBL = extended spectrum β-lactamase.

Figure 1.

Electrophoresis of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products of (A) blaTEM gene (459 bp) and (B) blaCTX-M gene (521 bp) of Escherichia coli on an agarose gel. Lanes 1 and 9 in both gels are DNA marker (GeneRuler 100 bp DNA Ladder, Thermo Fisher Scientific), lane 2 in both gels are positive controls (E. coli ATCC 35218), lanes 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8 are PCR products from E. coli isolates obtained from specimen.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of UTI was found to be 17.2%, which was lower than the studies by Kattel et al., and Rijal et al.35,36 MSU specimens were collected from patients under treatment, so infections because of slow-growing bacteria or those which might not be able to grow in routine culture media used in the study might be possible causes of a low rate of culture positivity.37

The prevalence of UTI among females was 77.9% which was significantly higher than that among males (22.1%). The results were in agreement with the findings by many other investigators.38–40 The proximity of the vaginal and anal opening among females and the absence of the prostatic fluid that has a bactericidal property may make them more susceptible to UTIs.41,42 The patients in the age group 21–40 showed the highest significant growth, that is, 44.5% which was similar to the study by Yadav and Prakash 2017 and Khan et al., 2013.10,39 Ranjbar et al. also reported a significantly higher UTI infection rate among the age group 30–40 years.42 The age group 1–20 showed the least significant growth, that is, 13.3%. Dash et al. (2013) and Thapa et al. (2013) reported the incidence of UTI was greater among sexually active females of reproductive age.43,44

The overall prevalence of UTI was 32.3% among patients with diabetes and 15.9% among nondiabetics. A similar prevalence rate, that is, 34.5% among patients with diabetes and 26.7% among nondiabetics was found in the study conducted in the Dhulikhel Hospital, Kathmandu University.45 Similarly, another study found the prevalence of UTI among patients with diabetes and nondiabetics to be 32% and 13%, respectively.46 Mubarak et al., 2012 reported a higher prevalence of UTI among patients with diabetes.47 It might have been because of diabetic nephropathy and incomplete bladder emptying in the hyperglycemic condition of the patients with diabetes.48 Every 10 years of diabetes duration increases a 1.9-fold prevalence of bacteriuria.49 However, the culture positivity among patients with diabetes and nondiabetics did not differ much accounting for 43.8% and 42.9%, respectively, in a study conducted in Bangladesh.50 The prevalence of UTI among female patients with diabetes was 46%, which was higher compared with the prevalence among male patients with diabetes (43%).51 These variations in the results may have been because of differences in the sample size and clinical conditions in the study population as mentioned in many studies.

Among the heterogeneous bacterial etiological agents of UTI, members of the Enterobacteriaceae family remain the predominant pathogens. The members of Enterobacteriaceae, being the normal flora of the human intestine, can easily invade and attach to the uro-epithelium causing UTI infections. Recently, Gram-positive bacteria were significantly isolated from patients with UTIs. The increasing rate of Gram-positive bacteria in UTIs is due to a number of virulence factors including their pathogenicity and high affinity to the epithelial lining of the urinary tract.52 We had also reported nearly 11% Gram-positive pathogens. Among Gram-negative bacteria, E. coli and K. pneumoniae were the most predominant ones. Similar results were present in other studies as well.51,53,54 However, 19.6% of E. coli was involved in bacteriuria followed by 2.7% K. pneumoniae in the study conducted in the International Friendship Children Hospital,53 of which 33.3% were MDR isolates. Similarly, 7.0% of E. coli and 2.3% of K. pneumoniae were isolated from significant bacteriuria in the study conducted by Chander and Shrestha.55 Among Gram-positive isolates, S. saprophyticus was the most predominant one followed by E. faecalis in this study. However, a study by Gajdács et al. reported E. faecalis as the most predominant one.52

The bacteria involved in UTI were similar in both patients with diabetes and nondiabetics. Escherichia coli was the predominant pathogen involved with 71.9% among patients with diabetes and 67.2% among nondiabetics followed by K. pneumoniae, that is, 15.6% among patients with diabetes and 14.8% among nondiabetics. Gurung et al. had also reported E. coli as the most predominant one followed by K. pneumoniae among uropathogens from a tertiary care hospital in Kathmandu.56 Similar to a study by Jankhwala et al.,46 Bonadio et al. found that E. coli constituted 32.5% and 31.4% followed by Enterococcus spp. 9.4% and 14.5%, respectively, among patients with diabetes and nondiabetics.57 They have also reported Pseudomonas spp. as the third most frequently isolated bacteria among male patients with and without diabetes with the occurrence at 8.5% and 17.2%, respectively. Similar to the results among males, female patients were found to be infected with 54.1% and 58.2% by E. coli, followed by Enterococcus spp. 8.3% and 6.5% and Pseudomonas spp. 3.9% and 4.7%, respectively, with and without diabetes. Although E. coli was the most common bacteria in both CA-UTI and hospital-acquired UTI among nondiabetics in many studies, Akbar observed Pseudomonas spp. as the most common bacterium among hospital-acquired UTI among patients with diabetes.58

Regarding the antimicrobial susceptibility testing of E. coli isolates, most were resistant to amoxicillin and third-generation cephalosporins, which could be due to the production of beta lactamases.59 The highest number of bacteria was sensitive to nitrofurantoin. Amikacin was another most effective drug against MDR isolates. More than 70% of isolates were resistant to cefepime, whereas 100% of isolates were sensitive to imipenem and meropenem. This result highly agreed with the study by Raeispour and Ranjbar.60 Although CLSI guidelines do not recommend disc diffusion methods for colistin and polymyxin B for antibiogram assay, the tertiary care hospitals in Nepal have been using these antibiotics in disc diffusion tests because of a high number of samples per day. They will perform MIC only if they find the isolates resistant to these antibiotics for confirmation. The results shown in Table 4 were just a screening protocol for those antibiotics routinely done in the hospitals.

Nearly one-half of E. coli isolates were found to be MDR strains. Out of 56 ESBL producers, 84.9% were confirmed to possess either single or both of the blaTEM and blaCTX-M genes. The incidence of ESBL producing E. coli among outpatients (89.1%) was higher than that among inpatients (63.6%) which was in contrast to the findings,61 revealing that the incidence of ESBL producing E. coli among inpatients was higher than that among outpatients. In this study, the ESBL producing E. coli was found comparatively higher in number than in the studies by Parajuli et al.24 and Seyedjavadi et al.62 Pokhrel et al. (2014) and Chander and Shrestha (2013) revealed even less ESBL producing E. coli.23,55 In our related study at the same hospital, we reported a higher rate of ESBL producers among uropathogenic E. coli.63 Patients with diabetes showed an increase in the number of infections compared with nondiabetics. The number, however, was not statistically significant. The emergence of more ESBL producing E. coli isolates from patients with UTI in recent years compared with the previous study can be associated with disease chronicity and long antibiotic therapy among patients experiencing diabetes, heart diseases, and other noncommunicable complications. These resistant strains are rapidly spreading in different clinical settings. These ESBL producing strains are highly resistant to the oxy-imino-cephalosporins. However, certain β-lactams may not be resisted by these strains creating challenges in the treatment procedures.

The prevalence of the blaCTX-M gene was found to be higher than that of the blaTEM gene similar to the study by Pokhrel et al. (2014) and Parajuli et al. (2016).23,24 Many other studies have also shown that the genes responsible for the production of CTX-M-type were more prevalent among the tested strains compared with the genes encoding other ESBL like SHV-type or TEM-type β-lactamases. Likewise, a study at Imam Khomeini and Baqiyatallah Hospitals, Tehran, Iran, showed the frequency of bla CTX-M, bla TEM, bla SHV, and qnrA genes was 87%, 82%, 65%, and 39%, respectively, among the ESBL producing E. coli isolates from patients with UTI.64 Halaji et al. had reported 53.2% (59/111), 45% (50/111), and 5.4% (6/111) of isolates harboring blaCTX-M, blaTEM, and blaSHV genes, respectively, from uropathogenic E. coli isolates from kidney transplant patients.65 Ojdana et al. and Valenza et al. also found the higher prevalence rates of the blaCTX-M genes.66,67 Sah et al. also detected 58.4% (7/12) blaCTX-M gene and 41.6% (5/12) blaTEM gene among ESBL producer E. coli isolates from a tertiary care hospital in Kathmandu.68 However, in contrast to this study, a higher prevalence of the blaTEM genes was detected in E. coli followed by blaCTX-M by Rezai et al. in northern Iran.69 Among the different types of the blaTEM genes, blaTEM-1 gene was reported as the most frequently detected gene. 55.2% ESBL producing uropathogenic E. coli harbored the blaTEM-1 gene.42 However, the presence of genes was unassociated with the diabetic condition of patients.

CONCLUSION

The comparative study of etiology and resistant profile of uropathogens among patients with diabetes and nondiabetics showed that patients with diabetes are more prone to UTI. Moreover, a higher prevalence of multidrug resistant especially ESBL producing uropathogens were associated with UTIs among the patients with diabetes which seems to be one of the major threats in disease management leading to a high rate of mortality and morbidity. Although first-line drugs seem to be ineffective, using second-line drugs with broad antimicrobial agents empirically in diabetic patients will help treat UTIs caused by MDR-ESBL strains. In addition, personal health hygiene and special precautions can reduce the incidence of UTIs among diabetic patients.

Limitations.

Because of the limited molecular resources and budget, all possible ESBL genes were not screened from those E. coli isolates. One more limitation of this study was we couldn’t do sequencing for further confirmation of those genes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all laboratory and technical staff at Microbiology Laboratory, Kathmandu Model Hospital and Microbiology Department, GoldenGate International College, Kathmandu, for their generous support throughout the research work and to GoldenGate International College for financial support for the molecular work. The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) assisted with publication expenses.

REFERENCES

- 1. International Diabetes Federation , 2017. IDF Diabetes Atlas , 8th edition. Brussels, Belgium: IDF. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Delamaire M, Maugendre D, Moreno M, Le Goff MC, Allannic H, Genetet B, 1997. Impaired leucocyte functions in diabetic patients. Diabet Med 14: 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fünfstück R, Nicolle LE, Hanefeld M, Naber KG, 2012. Urinary tract infection in patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Nephrol 77: 40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Truzzi JC, Almeida FM, Nunes EC, Sadi MV, 2008. Residual urinary volume and urinary tract infection—when are they linked? J Urol 180: 182–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown JS, Wessells H, Chancellor MB, Howards SS, Stamm WE, Stapleton AE, Steers WD, Van Den Eeden SK, MxVary KT, 2005. Urologic complications of diabetes. Diabetes Care 28: 177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gajdacs M, Urban E, 2019. Comparative epidemiology and resistance trends of proteae in urinary tract infections of inpatients and outpatients: a 10-year retrospective study. Antibiotics (Basel) 8: 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ifeanyichukwu I, Emmanuel N, Chika E, Anthonia O, Esther U, Ngozi A, Justina N, 2013. Frequency and antibiogram of uropathogens isolated from urine samples of HIV infected patients on antiretroviral therapy. Am J BioSci 1: 50–53. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Behzadi P, Urban E, Matuz M, Benko R, Gajdacs M, 2021. The role of Gram-negative bacteria in urinary tract infections: current concepts and therapeutic options. Adv Exp Med Biol 1323: 35–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Akram M, Shahid M, Khan AU, 2007. Etiology and antibiotic resistance patterns of community-acquired urinary tract infections in J N M C Hospital Aligarh, India. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 6: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yadav K, Prakash S, 2017. Screening of ESBL producing multidrug-resistant E. coli from urinary tract infection suspected cases in Southern Terai of Nepal. J Infect Dis Diagn 2: 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cullen IM. et al. , 2011. The changing pattern of antimicrobial resistance within 42,033 Escherichia coli isolates from nosocomial, community and urology patient-specific urinary tract infections, Dublin, 1999–2009. BJU Int 109: 1198–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yasmeen BHN, Islam S, Islam S, Uddin MM, Jahan R, 2015. Prevalence of urinary tract infection, its causative agents and antibiotic sensitivity pattern: a study in Northern International Medical College Hospital, Dhaka. North Int Med Coll J 7: 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pitout JD, Laupland KB, 2008. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: an emerging public-health concern. Lancet Infect Dis 8: 159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Paterson DL, Bonomo RA, 2005. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase: a clinical up to date. Clin Microbiol Rev 18: 657–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia LS, Isenberg HD, 2010 Clinical Microbiology Procedures Handbook. Third Edition. Washington, DC: ASM Press.

- 16. Abbasi H, Ranjbar R, 2018. The prevalence of quinolone resistance genes of A, B, S in Escherichia coli strains isolated from three major hospitals in Tehran, Iran. Cent European J Urol 71: 129–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ruppe E, Woerther PL, Barbier F, 2015. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in Gram-negative bacilli. Ann Intensive Care 5: 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sadeghi A, Halaji M, Fayyazi A, Havaei SA, 2020. Characterization of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance and serogroup distributions of uropathogenic Escherichia coli among Iranian kidney transplant patients. BioMed Res Int 2020: 2850183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cantón R, Novais A, Valverde A, Machado E, Peixe L, Baquero F, Coque TM, 2008. Prevalence and spread of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect 14: 144–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martinez P, Garzón D, Mattar S, 2012. CTX-M-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from community-acquired urinary tract infections in Valledupar, Colombia. Braz J Infect Dis 16: 420–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kunin CM, 1987. Detection, Prevention and Management of Urinary Tract Infections , 4th edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lea and Febiger. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gajdacs M, Batori Z, Abrok M, Lazar A, Burian K, 2020. Characterization of resistance in Gram-negative urinary isolates using existing and novel indicators of clinical relevance: a 10-year data analysis. Life (Basel) 10: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pokhrel RH, Thapa B, Kafle R, Shah PK, Tribuddharat C, 2014. Co-existence of beta-lactamases in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli from Kathmandu, Nepal. BMC Res Notes 7: 694–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Parajuli NP, Maharjan P, Joshi G, Khanal PR, 2016. Emerging perils of extended-spectrum β-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates in a teaching hospital of Nepal. BioMed Res Int 2016: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pandit R, Awal B, Shrestha SS, Joshi G, Rijal BP, Parajuli NP, 2020. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) genotypes among multidrug-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli clinical isolates from a Teaching Hospital of Nepal. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis 2020: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cheesbrough M, 2006. District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries, Part II , 2nd edition. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 112–113. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Isenberg HD, 2004. Clinical Microbiology Procedures Handbook, 2nd edition. Washington, DC: ASM Press. [Google Scholar]

- 28. CLSI , 2018. Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute: Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 28th edition. CLSI supplement M100. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standrads Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Magiorakos A-P. et al. , 2012. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pan drug resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 18: 268–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gajdacs M, Abrok M, Lazar A, Janvari L, Toth A, Terhes G, Burian K, 2020. Detection of VIM, NDM and OXA-48 producing carbapenem resistant Enterobacterales among clinical isolates in southern Hungary. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung 67: 209–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T, 1989. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual , 2nd edition. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thapa Shrestha U, Adhikari N, 2014. A Practical Manual for Microbial Genetics. Central Department of Microbiology, Tribhuvan University. Kathmandu, Nepal: Max Printing Press, 68–92. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sharma M, Pathak S, Srivastava P, 2013. Prevalence and antibiogram of extended spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) producing Gram negative bacilli and further molecular characterization of ESBL producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp. J Clin Diagn Res 7: 2173–2177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Edelstein M, Pimkin M, Palagin I, Edelstein I, Strachounski L, 2003. Prevalence and molecular epidemiology of CTX-M extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in Russian Hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47: 3724–3732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kattel HP, Acharya J, Mishra SK, Rijal BP, Pokhrel BM, 2008. Bacteriology of urinary tract infection among patients attending Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital Kathmandu, Nepal. J Nepal Assoc Med Lab Sci 9: 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rijal A, Ghimire G, Gautam K, Barakoti A, 2012. Antibiotic susceptibility of organisms causing urinary tract infection in patients presenting to a teaching hospital. J Nepal Health Res Counc 10: 24–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Joshi YP, Shrestha S, Kabir R, Thapa A, Upreti P, Shrestha S, 2016. Urinary tract infections and antibiotic susceptibility among the patients attending B & B hospital of Lalitpur, Nepal. Asian J Med Sci 7: 47–51. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pradhan B, Pradhan SB, 2017. Prevalence of urinary tract infection and antibiotic susceptibility pattern to urinary pathogens in Kathmandu Medical College and Teaching Hospital, Duwakot. Birat J Health Sci 2: 134–137. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Khan G, Ahmad S, Anwar S, 2013. Frequency of uropathogens in different gender and age groups. Gomal J Med Sci 11: 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Khatiwada S, Khanal R, Karn SL, Raut S, Poudel A, 2018. Antimicrobial susceptibility profile of urinary tract infection: a single centre hospital-based study from Nepal. J Univer Coll Med Sci 6: 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bhatt CP, Shrestha B, Khadka S, Swar S, Shah B, Pun K, 2012. Etiology of urinary tract infection and drug resistance cases of uropathogens. J Kathmandu Med Coll 1: 114–120. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ranjbar R, Ahmadnezhad B, Jonaidi N, 2014. The prevalance of beta lactamase producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from the urine samples in Valiasr Hospital. Biomed Pharmacol J 7: 425–431. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dash M, Padhi S, Mohanty I, Panda P, Parida B, 2013. Antimicrobial resistance in pathogens causing urinary tract infections in a rural community of Odisha, India. J Family Community Med 20: 20–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thapa P, Parajuli K, Poudel A, Thapa A, Manandhar B, Laudari D, Malla HB, Katiwada R, 2013. Causative agents and susceptibility of antimicrobials among suspected females with urinary tract infection in tertiary care hospitals of western Nepal. J Chitwan Med Coll 3: 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Acharya D, Bogati B, Shrestha G, Gyawali P, 2015. Diabetes mellitus and urinary tract infection: spectrum of uropathogens and their antibiotic sensitivity. J Manmohan Mem Inst Health Sci 1: 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jankhwala S, Singh S, Nayak S, 2014. A comparative study of profile of infections in diabetic and non-diabetic patients. Int J Med Sci Public Health 3: 982–985. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mubarak AA, Ashraf AM, El-hag M, Raza MA, Majed A, 2012. Prevalence of urinary tract infections among diabetes mellitus and non-diabetic patients attending a teaching hospital in Ajman, UAE. Gulf Med J 1: 228–232. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Keane EM, Boyko EJ, Reller LB, Hamman RF, 1988. Prevalence of asymptomatic in bacteriuria subjects with NIDDM in San Luis Valley of Colorado. Diabetes Care 11: 708–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Aswani SM, Chandrashekar UK, Shivashankara KN, Pruthvi BC, 2014. Clinical profile of urinary tract infections in diabetics and non-diabetics. Australas Med J 7: 29–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Saber M, Barai L, Haq J, Jilani M, Begum J, 2010. The pattern of organism causing urinary tract infection in diabetic and non-diabetic patients in Bangladesh. Bangladesh J Med Microbiol 4: 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chaudhury A, Ramana BV, 2012. Prevalence of uropathogens in diabetic patients and their resistance pattern at a tertiary care centre in south India. Int J Biol Med Res 3: 1433–1435. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Gajdacs M, Abrok M, Lazar A, Burian K, 2020. Increasing relevance of Gram-positive cocci in urinary tract infections: a 10-year analysis of their prevalence and resistance trends. Sci Rep 10: 17658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nithyalakshmi J, 2014. Bacterial profile and antibiogram pattern of UTI in pregnant women at tertiary care teaching hospital. Int J Pharma Bio Sci 5: 201–207. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Chaudhary P, Bhandari D, Thapa K, Thapa P, Shrestha D, Chaudhary HK, Shrestha A, Parajuli H, 2016. Prevalence of extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolated from urinary tract infected patients. J Nepal Health Res Counc 14: 111–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chander A, Shrestha CD, 2013. Prevalence of extended spectrum beta lactamase producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae urinary isolates in a tertiary care hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal. BMC Res Notes 6: 487–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Gurung S, Kafle S, Dhungel B, Adhikari N, Thapa Shrestha U, Adhikari B, Banjara MR, Rijal KR, Ghimire P, 2020. Detection of OXA-48 gene in carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae from urine samples. Infect Drug Resist 13: 2311–2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bonadio M, Costarelli S, Morelli G, Tartaglia T, 2006. The influence of diabetes mellitus on the spectrum of uropathogens and the antimicrobial resistance in elderly adult patients with urinary tract infection. BMC Infect Dis 6: 54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Akbar DH, 2011. Urinary tract infection diabetics and non-diabetics. Saudi Med J 22: 326–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Maharjan A, Bhetwal A, Shakya S, Satyal D, Shah S, Joshi G, Khanal PR, Parajuli NP, 2018. Ugly bugs in healthy guts! Carriage of multidrug-resistant and ESBL-producing commensal Enterobacteriaceae in the intestine of healthy Nepalese adults. Infect Drug Resist 11: 547–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Raeispour M, Ranjbar R, 2018. Antibiotic resistance, virulence factors and genotyping of Uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 3: 118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Rimal U, Thapa S, Maharjan R, 2017. Prevalence of extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species from urinary specimens of children attending Friendship International Children’s Hospital. Nepal J Biotechnol 5: 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Seyedjavadi SS, Goudarzi M, Sabzehali F, 2015. Relation between bla TEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M genes and acute urinary tract infections. J Acute Dis 5: 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Thapa Shrestha U, Shrestha S, Adhikari N, Rijal KR, Shrestha B, Adhikari B, Banjara MR, Ghimire P, 2020. Plasmid profiling and occurrence of β-lactamase enzymes in multidrug-resistant uropathogenic Escherichia coli in Kathmandu, Nepal. Infect Drug Resist 13: 1905–1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Abdi S, Ranjbar R, Vala MH, Jonaidi N, Bejestany OB, Bejestany FB, 2014. Frequency of bla TEM, bla SHV, bla CTX-M, and qnrA among Escherichia coli isolated from urinary tract infection. Arch Clin Infect Dis 9: e18690. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Halaji M, Shahidi S, Atapour A, Ataei B, Feizi A, Havaei SA, 2020. Characterization of Extended-spectrum beta-Lactamase-producing uropathogenic Escherichia coli among Iranian kidney transplant patients. Infect Drug Resist 13: 1429–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ojdana D, Sacha P, Wieczorek P, Czaban S, Michalska A, Jaworowska J, Jurczak A, Poniatowski B, Tryniszewska E, 2014. The occurrence of bla CTX-M, bla SHV, and bla TEM Genes in extended-spectrum β-lactamase-positive strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and Proteus mirabilis in Poland. Int J Antibiot 2014: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Valenza G, Nickel S, Pfeifer Y, Eller C, Krupa E, Lehner-Reindl V, Höller C, 2014. Extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli as intestinal colonizers in the German community. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58: 1228–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sah RSP, Dhungel B, Yadav BK, Adhikari N, Thapa Shrestha U, Lekhak B, Banjara MR, Adhikari B, Ghimire P, Rijal KR, 2021. Detection of TEM and CTX-M genes in Escherichia coli isolated from clinical specimens at tertiary care heart hospital, Kathmandu, Nepal. Diseases 9: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Rezai MS, Salehifar E, Rafiei A, Langaee T, Rafati M, Shafahi K, Eslami G, 2015. Characterization of multidrug-resistant extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli among uropathogens of pediatrics in the north of Iran. BioMed Res Int 2015: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]