Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to characterize the individual contribution of multiple fat peaks to the measured chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) signal when using water-selective binomial-pulse excitation and to determine the effects of multiple fat peaks in the presence of B0 inhomogeneity.

Methods

The excitation profiles of multiple binomial pulses were simulated. A CEST sequence with binomial-pulse excitation and modified point-resolved spectroscopy localization was then applied to the in vivo lumbar spinal vertebrae to determine the signal contributions of three distinct groups of lipid resonances. These confounding signal contributions were measured as a function of the irradiation frequency offset to determine the effect of the multi-peak nature of the fat signal on CEST imaging of exchange sites (at 1.0, 2.0 and 3.5 ppm) and robustness in the presence of B0 inhomogeneity.

Results

Numerical simulations and in vivo experiments showed that water excitation (WE) using a 1-3-3-1 (WE-4) pulse provided the broadest signal suppression, which provided partial robustness against B0 inhomogeneity effects. Confounding fat signal contributions to the CEST contrasts at 1.0, 2.0 and 3.5 ppm were unavoidable due to the multi-peak nature of the fat signal. However, these CEST sites only suffer from small lipid artifacts with ΔB0 spanning roughly from −50 to 50 Hz. Especially for the CEST site at 3.5 ppm, the lipid artifacts are smaller than 1% with ΔB0 in this range.

Conclusion

In WE-4-based CEST magnetic resonance imaging, B0 inhomogeneity is the limiting factor for fat suppression. The CEST sites at 1.0, 2.0 ppm and 3.5 ppm unavoidably suffer from lipid artifacts. However, when the ΔB0 is confined to a limited range, these CEST sites are only affected by small lipid artifacts, which may be ignorable in some cases of clinical applications.

Keywords: CEST, Lipid artifact, Water excitation, B0 inhomogeneity, Body imaging

Introduction

Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has recently been exploited as a novel methodology in the field of molecular imaging [1–5]. CEST MRI has shown great potential in the diagnosis of brain diseases [6]. Recently, body imaging applications of CEST have also been reported by various studies, including studies of breast tumors [7–17], prostate cancer [18], and changes in the metabolic composition of the liver [19]. However, since CEST seeks to indirectly measure proteins and metabolites via the spin-exchange with water, this approach is susceptible to confounding signal contributions from fat in body tissues.

One approach to fat suppression is water-selective excitation (WE) using a binomial RF pulse. This approach has been utilized to remove lipid artifacts in body CEST studies [7, 8, 10, 19], with insensitivity to B1 inhomogeneities and no additional acquisition time requirements. The binomial RF pulse approach is designed to emphasize the suppression of the main fat peak [20, 21], ignoring the inferior peaks in the fat signal that still may introduce lipid artifacts into the CEST contrast. A previous study [22] demonstrated that body fat contains six clear spectral peaks, and more than 30% of the fat signals are not from the main peak (CH2) at −3.40 ppm. Usually, the asymmetric magnetic transfer ratio (MTRasym) is used to extract the CEST signal, which would lead to the CEST sites at 1.0, 2.0 and 3.5 ppm under the contamination of lipid artifacts. CEST contrast at 3-T is small, hence, susceptible to artifacts that would be negligible in conventional relaxation-weighted imaging. Furthermore, body MRI is more prone to B0 inhomogeneity than brain MRI, and binomial water-selective excitation is relatively sensitive to such inhomogeneities.

The goal of this paper was to study the potential artifacts originating from the multi-peak nature of the fat signal and the B0 inhomogeneity when using water-selective binomial-pulse excitation, with an emphasis on the artifact effect on typical CEST exchange sites at 1.0 ppm, 2.0 ppm and 3.5 ppm. Common binomial pulse WE techniques for the suppression of fat signal include 1-1 (WE-2), 1-2-1 (WE-3) [23], and 1-3-3-1 (WE-4) [24] pulses. A previous study showed that the wider suppression bandwidth of the 1-3-3-1 pulse led to increased suppression of the inferior fat peaks near the main peak [25]. Hence, only WE-4 pulse [24] was used in the in vivo study to characterize the lipid artifacts. Besides, this work complements a previous study that characterized artifactual lipid contributions when applying a distinct lipid suppression pulse [26]. To distinguish the individual contribution of fat peaks to the WE-based CEST signals in this study, a modified point-resolved spectroscopy (mPRESS) was used for signal acquisition after CEST preparation.

Materials and methods

Simulation

A simulation based on the numerical solution of the Bloch equation was conducted in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natwick, MA, USA) to investigate the performance of WE. In the simulation, evolutions of the spins under the WE were calculated numerically as a function of frequency offset, with the excitation profile equated to the resulting magnitude of transverse magnetization. Since the duration of the WE pulse was much less than T1 and T2 of biological tissues, these relaxation processes were ignored in the simulation. Although the water-selective excitation with binomial pulses have been reported previously [25], simulations for the three types of WE (WE-2, WE-3 and WE-4) were still performed to clarify the relevant excitation profile. The timing parameters of WE with the emphasis on the suppression of the fat signal at −3.4 ppm were identical to those for in vivo experiments in the scanner (2.89 T). Furthermore, the simulation is used to investigate the influence of B0 inhomogeneity on the excitation profile and the excitation efficiency of the individual fat peak. The details of simulation were included in supplementary material.

In vivo experiments

All in vivo experiments were performed on a clinical 3 T MRI system (MAGNETOM Prisma Fit, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) using a standard spinal coil for the in vivo study. Three volunteers were recruited for the in vivo experiments. The human studies were approved by the institutional research ethics committee of our institution, and written informed consent was obtained from all volunteers.

The volume of interest (VOI) with a high proton-density fat fraction (PDFF) for the CEST-mPRESS sequence was located in the lumbar vertebrae, where the measurement of the PDFF was conducted using the established Siemens sequence, namely, single-voxel high-speed T2-corrected multiple-echo 1H-MRS acquisition (HISTO) [27]. Then, a conventional PRESS was conducted to determine the raw composition of the fat (including chemical shifts and relative amplitudes of fat peaks) with the VOI same as those of HISTO. The parameters of PRESS were as follows: repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE) = 6000/20 ms, VOI = 2 × 2 × 2 cm3, acquisition bandwidth = 1200 Hz, data points = 1024.

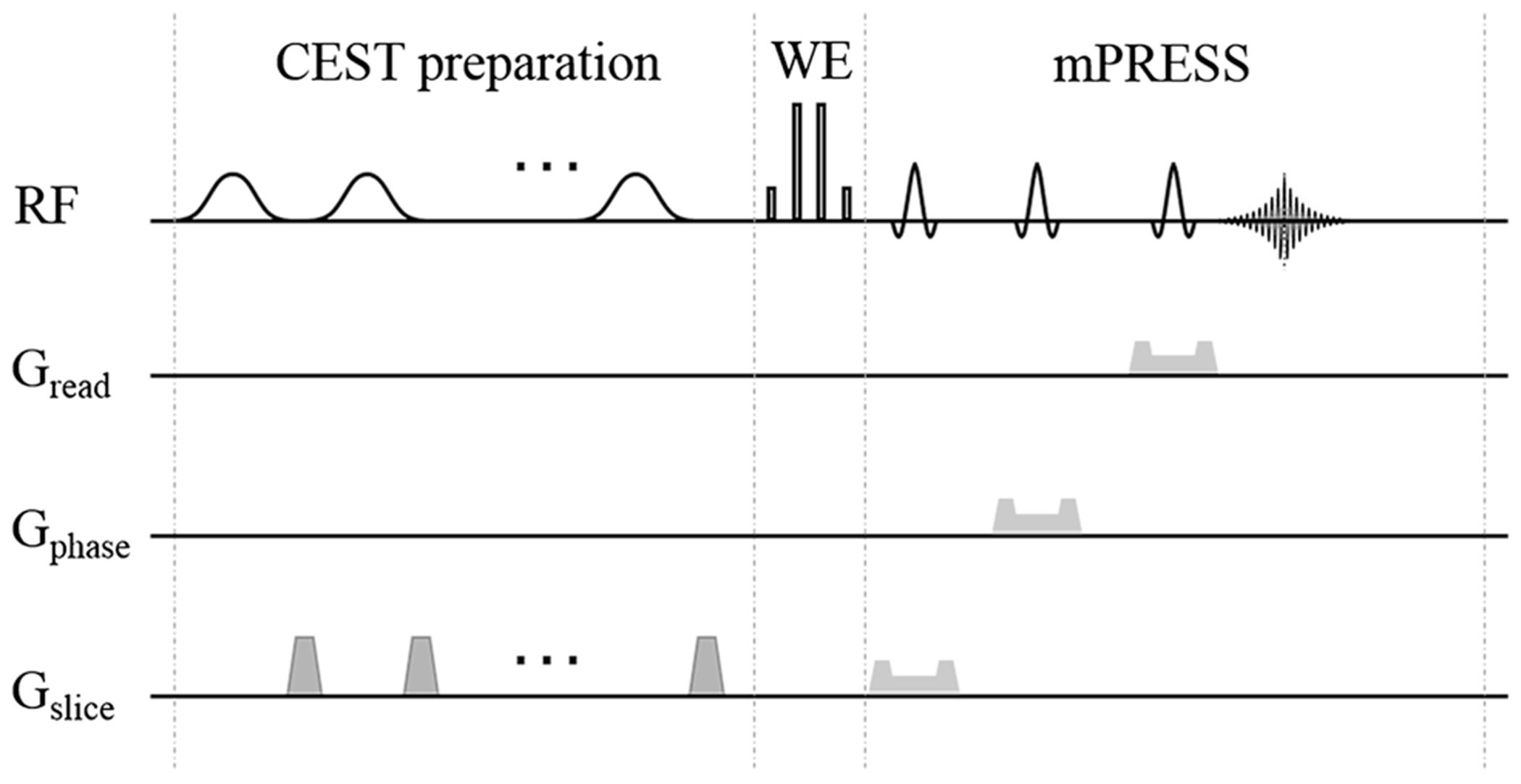

The CEST-mPRESS sequence was developed in-house on the Siemens pulse sequence development platform. The CEST-mPRESS sequence (Fig. 1) consists of three parts: the CEST preparation, WE-4 excitation, and mPRESS signal acquisition. The CEST preparation contains six Gaussian-shaped pulses, each 200-ms long, with an average B1 of 1.6 μT, and interleaved with 5-ms duration of spoiling gradients. A total of 61 frequency offsets were acquired in the Z-spectrum from −5 to 5 ppm with an increment of 0.25 ppm, and one reference acquisition without the saturation RF pulses was also acquired. WE-4 excitation contains four hard pulses with the timing parameters: duration of hard pulse = 40 μs and delay of pulses = 1200 μs (Fig. S1). In mPRESS signal acquisition, the first slice-selective 90° RF pulse in conventional PRESS was replaced by the non-slice-selective WE-4 followed by a slice-selective 180° RF pulse. The scanning parameters of mPRESS were same as those of PRESS. Additionally, to investigate the influence of B0 inhomogeneity on fat suppression, the frequency offset of the numerically controlled oscillator (NCO) was set during the WE block to generate an off-resonance effect that was equivalent to the off-resonance effect induced by B0 inhomogeneity, though this approach did not model any possible intra-voxel dephasing effects. The frequency offsets of the NCO were turned on only during the implementation of WE-4; hence, it had no influence on the CEST preparation or slice selection. In the conventional CEST experiments, B0 inhomogeneity would lead to a shift of Z-spectrum, which can be avoided with the equivalent B0 inhomogeneity produced by the frequency offset of NCO. The frequency offsets of the NCO were set to provide values of ΔB0 spanning from −100 to 100 Hz, with an increment of 10 Hz.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of CEST-mPRSS sequence. This sequence contains three blocks: CEST preparation, water excitation (WE), the MRS acquisition (mPRSS). Gread the gradient in the readout direction, Gphase the gradient in the phase-encoding direction, Gslice the gradient in the slice-selected direction

Data processing

The total signal acquired in the WE-4-based CEST MRI and MRS can be described as:

| (1) |

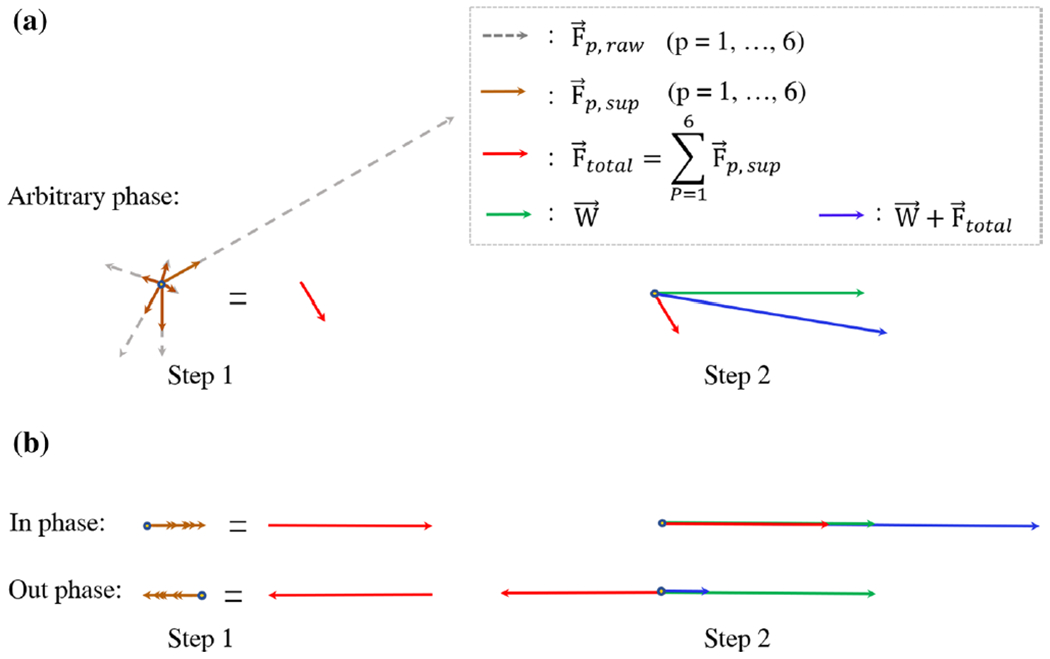

where ρW and ρFp are the amplitudes of the water peak and the pth fat peak(p = 1, …, P), respectively; Δω is the frequency offset of CEST pre-saturation; φw and φFp are the phases of the water and the pth fat peak, respectively. The phase of each component stems from the precessions during the WE-4 pulses and the acquisition delay. The residual fat signals in Eq. (1) are determined by the CEST preparation and WE. During the CEST preparation, RF pulses saturates each fat peak at different levels. Then the residual fat magnetizations would be partly excited by WE-4, which leads to the confounding signals in the CEST imaging. Furthermore, the residual fat signals depend on the phases of the fat components (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The fat-contaminated signals in the WE-4 CEST MRI and MRS. is the component of a fat peak (p, p = 1, …, 6) without suppression, which show the raw relative amplitude of the fat peak. is the component of the fat peak with the suppression from the CEST pre-saturation and WE. The two-step vector summation is used to show how the water signal is polluted by the fat components with an arbitrary phase (a). The signals with the maximum fat contamination are obtained when the fat components are in and out phase with the water component (b). Note that only the maximum fat contamination is calculated during post-processing although the fat components with an arbitrary phase is a more general case

In the conventional CEST imaging, CEST effect is usually extracted by the asymmetry of the magnetization transfer ratio (MTRasym). The fat components in Z-spectrum are asymmetric relative to the water resonance, resulting in lipid artifacts in the asymmetry analysis. The lipid artifacts in the CEST imaging depend on the phase of fat peaks, which have been investigated in the previous study [15]. The maximum lipid artifacts from all fat peaks are obtained when φFW − φFP = nπ, where n is an integer, i.e., when an individual fat component was completely in or out of phase with water (Fig. 2b). In this study, we only examined this maximum artifact by adding together the lipid artifacts of the individual fat peak, rather than having a more general and complex case that allows for arbitrary phase values. The probable maximum lipid artifact in the asymmetry analysis form all fat peaks can be described as:

| (2) |

where Sref is the total signal intensity in the reference scan without CEST pre-saturation pulse.

The spectral peaks of fat obtained from the CEST-mPRESS sequence have complex phases because these spectral peaks of fat undergo complicated precessions during the WE-4 that cannot be corrected using the conventional methods of the zero and first order phasing. Hence, 1H spectra are displayed as the amplitude of the signal in this study. The Z-spectrum from each individual fat peak was based on the areas under the corresponding peak in the 1H spectra. Adjacent fat peaks were analyzed as a group for Z-spectra analysis since they overlapped and were difficult to be completely separated. After obtaining the Z-spectra from the water peak and each group of the adjacent fat peaks individually, LAasym was calculated to quantify the lipid artifacts. Finally, the probable maximum LAasym from all fat peaks were estimated by adding together the magnitudes of these residual fat peaks as described in Eq. (2).

Results

Simulation

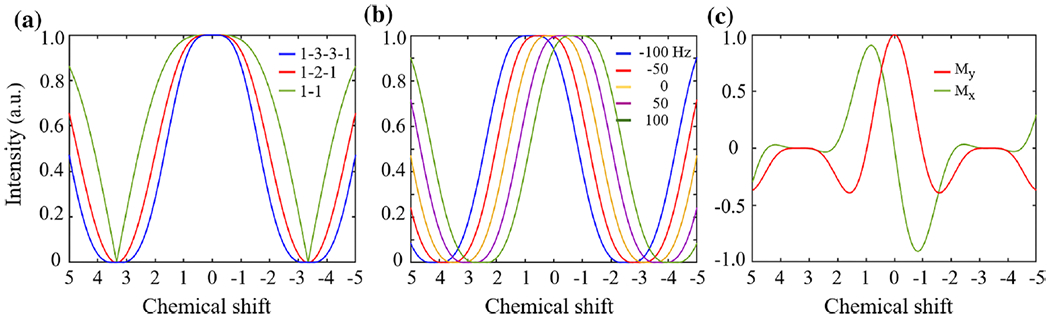

Figure 3 shows the predicted excitation profile from the numerical simulation for WE-2, WE-3, and WE-4. The excitation profiles are plotted on chemical shift scales rather than on frequency scales to show the relationship between the excitation profile and fat peaks. Therefore, the frequency of excitation profiles equals the frequency of the spin with the corresponding chemical shift at 2.89 T. In the excitation profiles, the null point appears at the main spectral peak of fat, and a broad near-zero range exists near this point. As shown in Fig. 3a, WE-4 has a broader bandwidth for suppression than do WE-2 and WE-3. Figure 3b demonstrates that B0 inhomogeneity leads to a corresponding shift in the excitation profile along the axis of chemical shift. In Fig. 3c, the real and imaginary components of the excitation profile display the complicated phase responses of WE-4 at different offsets.

Fig. 3.

The predicted excitation profile of WE techniques from the numerical simulation. The excitation profiles of frequency are plotted with their chemical shift scales referring to the water resonance frequency, and the x-axis is taken as the absolute coordinate of the chemical group. The magnitudes of the transverse magnetization (a) are displayed as the excitation profiles of WE techniques in the types of [26] (green line), {1-2-1} (red line) and {1-3-3-1} (blue line). The excitation profile is shifted with the field inhomogeneity, where three values of ΔB0 (−100, −50, 0 50, and 100 Hz) are used to simulate the excitation profiles of WE in the type of {1-3-3-1} (b). The real part (read line) and imaginary part (green line) of transverse magnetization show the phase response of the WE in the type of {1-3-3-1} (c)

Figure 4 shows the excitation on the individual fat peaks when WE-4 is applied with varying B0 inhomogeneity. The raw relative amplitudes of six fat peaks (P1–P6) measured in the in vivo experiment were used as initial values in this simulation, which also provide a reference for the residual signals of fat peaks after WE-4. As shown in Fig. 4, P3–P6 can be suppressed by WE-4 when B0 inhomogeneity is limited in a corresponding range of frequency, while P1 and P2 are always out of the strong-suppression range of WE-4.

Fig. 4.

The excitation of WE-4 on the individual fat peaks with varying B0 inhomogeneity. The excitation of WE-4 on the individual fat peaks is displayed separately. The raw relative amplitudes of six fat peaks (P1–P6) measured in the in vivo experiment are shown as a reference for the residual signals of fat peaks after WE-4. P1–P6 denote the fat peaks ranging from low field to high field

In vivo experiment

Three volunteers with different PDFF (43%, 49% and 57%) demonstrated similar results. The spectra from the volunteer with the highest PDFF in the VOI of lumbar vertebrae, and the highest potential for artifacts, are displayed in Figs. 5 and 6. The results from the other two volunteers are shown in Fig. S2 and S3 in supplementary material.

Fig. 5.

The 1H spectra of the in vivo lumbar vertebrae experiment measured using (a) the conventional PRESS sequence and (b) the CEST-mPRESS sequence with various ΔB0. VOI of the MRS sequence was labeled by a red square in an anatomic image. 1H spectra were plotted with their chemical shift scales referring to the water resonance frequency. Note that the x-axis is the conjugate space after Fourier transform of the signal, and not the CEST preparation irradiation frequency. P1–P6 denote the fat peaks ranging from low field to high field. In (b) 1H spectra were acquired with ΔB0 ranging from −100 Hz (down) to 100 Hz (up) with an increment of 10 Hz

Fig. 6.

The Z-spectrum (blue line), MTRasym of water (red line in the 1st row) or LAasym of fat (red line in the 2nd to 4th row) as a function of irradiation offset from the in vivo lumbar vertebrae of a volunteer with ΔB0 = −100 Hz (1st column), 0 Hz (2nd column) and 100 Hz (3rd column). The LAasym from three groups of fat peaks are displayed separately. The first group (P1) contains one fat peak that is located at 0.60 ppm. The second and third groups contain two peaks which are difficult to be separated (P3 and P4 corresponding to the peaks located at −1.94 and −2.60 ppm; P5 and P6 corresponding to the peaks located at −3.40 and −3.80 ppm). The total Z-spectrum are built by adding the absolute values of the Z-spectra. MTRasym of the total Z-spectrum show that the CEST contrasts are concomitated by LAasym

Figure 5 shows two types of 1H spectra from a VOI in the lumbar vertebrae, both using the CEST convention of setting their chemical shift scales relative to the water resonance frequency. In Fig. 5a, a 1H spectrum from a conventional PRESS sequence shows six clear fat peaks (P1–P6) with chemical shifts of 0.62, −0.39, −1.93, −2.66, −3.38, and −3.81 ppm (relative to the water resonance) and with relative amplitudes of 0.051, 0.037, 0.009, 0.124, 0.683, and 0.096, respectively. The measured composition of fat agrees well with the previous study [22]. Figure 5b displays the 1H spectrum from the CEST-mPRESS with no preparation pulses (i.e., the “reference scan”) and with ΔB0 spanning from −100 to 100 Hz. The key difference between the spectra in Fig. 5a and b is the effect of the WE-4 excitation profile, which at ΔB0 = 0 suppresses P2–P5. Additionally, Fig. 5b shows the effect of varying the field inhomogeneity ΔB0 from −100 to 100 Hz. Within a limited range (very roughly |ΔB0|< 50 Hz), P3–P5 remained suppressed.

Figure 6 shows how the residual lipid signals from each spectral peak produce artifacts in the CEST signal and metric and how these artifacts change with ΔB0 = −100 Hz, 0 Hz and 100 Hz. The fat peaks are separated into three groups by considering adjacent fat peaks as a group (P1 as a group; P3 and P4 as a group; and P5 and P6 as a group). It is difficult to separate P2 from the water peak accurately; hence, the Z-spectrum is not built for P2 and the Z-spectrum of water contains the signal component of P2. Z-spectrum and MTRasym built from each group of fat peaks and the water peak are displayed separately, which gives insight into the composition of lipid artifacts. There is no obvious CEST contrasts in MTRasym obtained from the water signal (Fig. 6a–c). For ΔB0 = 0 Hz, the obvious lipid artifacts only appear at P1. However, for ΔB0 = −100 Hz, the Z-spectrum built on P5 and P6 provide obvious contributions to the lipid artifacts; for ΔB0 = 100 Hz, the Z-spectrum built on P3 and P4 and on P5 and P6 provide obvious contributions to the lipid artifacts. Furthermore, it is noticeable that each single fat peak or group without effective suppression can produce lipid artifacts for a broad range of frequencies.

Figure 7 shows LAasym in the in vivo experiments of three volunteers when imaging the typical CEST sites at 1.0, 2.0, 3.5 ppm with ΔB0 spanning from −100 to 100 Hz. The lipid artifacts originating from three distinct lipid peak groups, along with the probable maximum LAasym, are displayed separately. As shown in Fig. 7, the probable maximum LAasym on the three typical CEST sites increase with PDFF. The lipid artifacts on the CEST sites at 1.0, 2.0 and 3.5 ppm occur in the range of ΔB0 from −100 to 100 Hz. However, these CEST sites only suffer from small LAasym with ΔB0 spanning roughly from −50 to 50 Hz. Especially for the CEST site at 3.5 ppm, LAasym is smaller than 1% with ΔB0 in this range.

Fig. 7.

LAasym on the CEST sites at 1.0 (a–d), 2.0 (e–h) and 3.5 ppm (i–l) obtained from in vivo experiments with ΔB0 ranging from −100 to 100 Hz. LAasym originating from three distinct lipid peak groups, along with the probable maximum LAasym, are displayed separately. The probable maximum LAasym was estimated by adding together LAasym from all lipid peak groups. The probable maximum LAasym on the three typical CEST sites increase with PDFF. LAasym at the CEST sites at 1.0, 2.0 and 3.5 ppm occur in the range of ΔB0 from −100 to 100 Hz. However, these CEST sites suffer from small lipid artifacts with ΔB0 spanning roughly from −50 to 50 Hz

Discussion

WE techniques are designed with an emphasis on the suppression of the main fat peak. However, fat signals contain multiple peaks distributed over a broad frequency range, which could result in insufficient suppression of some inferior fat peaks and lead to lipid artifacts in a CEST image. Furthermore, body imaging with WE techniques is sensitive to B0 inhomogeneity. There are several factors leading to B0 inhomogeneity in body MRI, including the cavities with air surrounding the organs in body (such as breast, liver and prostate), the potential eccentric position in the magnet, and the different magnetic susceptibilities of fat and water in body tissue [28]. After B0 shimming based on the vendor’s protocol, the B0 inhomogeneity in body MRI can be confined to be in the range from −100 to 100 Hz [14]. Therefore, we investigated the influence of B0 inhomogeneity on lipid suppression in the same range of B0 inhomogeneity. In this study, the lumbar vertebrae of human was selected for the VOI localization, because it is less susceptible to the physiologic motion.

WE-4 provides effective and broad signal suppression covering roughly the lipid peaks P3–P6 with perfect field homogeneity. This result can be demonstrated in numeric simulations (Fig. 3a, which also shows the broader suppression of WE-4 vs. WE-2 or WE-3) and in in vivo spectra (Fig. 5b, with 0 Hz offset caused by ΔB0). Considering that no direct saturation of the fat peaks is seen in the reference scan shown in Fig. 5, the disappearance of the fat peaks stems only from the suppression of WE-4. Note that the P1 and P2 peaks are outside the chemical-shift range of strong suppression (Fig. 4).

Field inhomogeneity is a confounding effect in CEST imaging. To clarify the mechanism and its consequence for fat suppression, we isolated the effects of field inhomogeneity during the excitation pulse, ignoring the distinct effects on CEST preparation irradiation, since these have been dealt with extensively in the literature. Figure 5b shows that (1) there are no obvious signals from P5 and P6 (near the main fat peak) when ΔB0 is approximately confined to the frequency range from −50 to 50 Hz, (2) there is no strong suppression of P1 when ΔB0 is in the range from −100 to 100 Hz, and (3) P3 and P4 display low signals with ΔB0 in the broad frequency range from −100 to 50 Hz (Fig. 5b). A key summary is that P3 to P6 can be suppressed simultaneously with ΔB0 in the frequency from −50 to 50 Hz. The results of the in vivo experiments agree well with the results of simulation (Fig. 4).

While Fig. 5b illustrates the dependency of lipid-peak suppression on field inhomogeneity that is modeled with the frequency offset of the WE-4 excitation pulse, Fig. 6 show how any failure to suppress the lipid peaks results in artifactual contributions to the CEST metric, MTRaysm. P1, located at 0.60 ppm, is outside the chemical-shift range of strong suppression (Fig. 4a), and there are obvious residual signals from this peak (Fig. 5b). Lipid artifacts from P1 affect not only the CEST site at 1.0 ppm, but also the CEST site at 2.0 ppm (Fig. 6d–f). Therefore, it is not possible to prevent the CEST sites at 1.0 and 2.0 ppm from being affected by the lipid artifacts of P1 in WE-4-based CEST. However, the relative amplitude of P1 is small, hence it has a limited contribution to the total lipid artifacts. The residual fat signal from P3 to P6 can also generate lipid artifacts across a broad range. Since the relative amplitudes of these fat peaks are considerable, they have major contributions to total lipid artifacts. It is noticeable hat the lipid artifacts from single fat peak can spread across a broad range, which was also observed in a previous study [26]. In this study, lipid artifacts from P2 are not investigated because P2 cannot be separated with the water peak. P2 at −0.39 ppm is adjacent to the water peak and has a small relative amplitude of 0.037, hence it can be inferred that lipid artifacts from P2 would be smaller than those from P1 and would be ignorable.

The CEST sites at 1.0, 2.0 and 3.5 ppm suffer from small LAasym with ΔB0 spanning roughly from −50 to 50 Hz (Fig. 7). Especially for the CEST at 3.5 ppm, the LAasym is smaller than 1% with ΔB0 in this range. This is consistent with the fact that the fat peaks from P3 to P6 are suppressed simultaneously with ΔB0 in this frequency range, which is in line with Fig. 5b. In some previous studies, the changes of CEST contrast between the tissues in different physiological and pathological conditions are significantly greater than this level of lipid artifacts [7, 12, 29]. In these cases, the lipid artifacts at this level may be tolerable. Our results also suggest that the influence of lipid artifacts on CEST contrast can be evaluated by monitoring B0 inhomogeneity when WE-4 is used in the body CEST imaging. The fat signals in the pixels with large ΔB0 cannot be sufficiently suppressed in the WE-4 based image, hence these pixels should be considered as the unreliable pixels due to lipid artifacts. The conclusions mentioned above is based on the data from the voxels with PDFF lower than 57%. If the PDFF is more than 57%, the lipid artifacts would increase, and the conclusions may be invalid. In fact, for pixels with high PDFF, the CEST contrast would have a low signal-to-noise ratio. Hence, the pixels with PDFF greater than a specific threshold should be removed from the CEST images, which also reported in the previous study [15]. In the future study, by simultaneously monitoring B0 inhomogeneity and DPFF, the pixels with obvious lipid artifacts can be removed to guarantee the accuracy of the presented CEST images.

The water-selective excitation was based on hard RF pulses without spectral selectivity in this study, which allowed that the equivalent B0 inhomogeneity produced by the frequency offset of NCO had no influence on the point-resolved spectroscopy localization. In the practical WE-based CEST imaging, the spectral-selective soft pulses accompanied by gradient field is used to achieve a slice-selective excitation. In this way, the frequency offset of NCO would lead to a spatial displacement in the slice-selective excitation. Therefore, the hard pulses were selected in this study for the non-slice-selective excitation, followed by three slice-selective 180° RF pulses which were used to achieve the point-resolved spectroscopy localization. The slice-selective WE pulses can excite the water magnetization in the same way as the non-slice-selective WE, hence it can be inferred that the conclusions in study would apply to the CEST imaging based on the slice-selective WE.

In this study, the CEST pre-saturation in the CEST-mPRESS sequence consisted of six Gaussian-shaped pulses with pulse duration of 200 ms for each pulse and an average B1 of 1.6 μT. As shown in supplementary material, the results from other two volunteers show that the parameters of CEST pre-saturation ensure obvious CEST contrasts at 2.0 and 3.5 ppm. It is noticeable that no obvious CEST contrasts are observed in the case shown in Fig. 6, which would arise from the specific physiological status of the measured tissues rather than the parameters of CEST pre-saturation. The value of B1 was selected based on the previous studies of body CEST imaging at 3 T [7, 12, 14, 30]. Large B1 values are beneficial to imaging of CEST sites with fast exchange rate [31]. However, the direct saturation on water become more serious with the increase of B1 value especially at 3 T, which reduces the CEST contrast [31, 32]. For the body CEST, transverse relaxation is an additional factor leading to a strong direct saturation. The relatively large value of R2 in the body tissue can increase the effect of direct saturation [14, 33]. Therefore, optimal B1 value depends on the exchange rate of CEST sites and the observed tissues when WE-4-based CEST is applied on the body at 3 T.

This preliminary work has the following additional limitations, which could be addressed in future studies. The WE-4-based CEST imaging sequences are not further conducted to investigate the lipid artifact in CEST images in this study, because the lipid artifacts cannot be analyzed properly in the WE-4-based CEST MRI for two main reasons. Firstly, the true CEST contrast and lipid artifacts are not distinguishable in the WE-4-based CEST imaging. Secondly, a clear analysis of the lipid artifacts in the CEST images would rely on the phases of the individual fat resonances. However, each fat resonance usually has arbitrary phase value, which cannot be investigated in the WE-4-based CEST imaging. In this study, MRS acquisition was used to distinguish the water and fat resonances, and the probable maximum lipid artifacts were measured by adding together all the lipid artifacts of the individual fat peak. The probable maximum lipid artifacts in the WE-4-based CEST imaging can be estimated by those measured in the study. Therefore, the conclusions obtained in this study still provide the instructive information to avoid the lipid artifacts in the WE-4-based CEST MRI. Besides, the effectiveness of fat suppression using WE-4 is only investigated at the held strength of 2.89 T. The timing and effectiveness of fat suppression of WE-4 for the MR scanners with the other held strengths need to be investigated in the future work.

Conclusion

WE-4 provides suppression of fat signals across a broad frequency range, which is sufficient to cover the primary, but not the minor, fat peaks. Additionally, this suppression is sensitive to changes in ΔB0. The CEST sites at 1.0, 2.0 ppm and 3.5 ppm unavoidably suffer from lipid artifacts. However, when the ΔB0 is confined to a limited range, these CEST sites are only affected by small lipid artifacts, which may be ignorable in some cases of clinical applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant Number 81271533]; the Social Science Foundation of China [Grant Number 15ZDB016]; and National Institutes of Health [Grant Numbers R01CA184693, R01EB017767].

Abbreviations

- CEST

Chemical exchange saturation transfer

- B0

Main magnetic held

- ΔB0

Main field inhomogeneity

- WE

Water-selective excitation

- WE-2

Water-selective excitation using the 1-1 pulse

- WE-3

Water-selective excitation using the 1-2-1 pulse

- WE-4

Water-selective excitation using the 1-3-3-1 pulse

- PRESS

Point-resolved spectroscopy

- mPRESS

Modified point-resolved spectroscopy

- MTRasym

Asymmetric magnetic transfer ratio

- VOI

Volume of interest

- PDFF

Proton-density fat fraction

- HISTO

Single-voxel high-speed T2-corrected multiple-echo 1H-MRS acquisition

- NCO

Numerically controlled oscillator

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10334-020-00851-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval The study was approved by the University Committee on Human Research Protection of East China Normal University.

Informed consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Ward KM, Aletras AH, Balaban RS (2000) A new class of contrast agents for MRI based on proton chemical exchange dependent saturation transfer (CEST). J Magn Reson 143(1):79–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou JY, Payen JF, Wilson DA et al. (2003) Using the amide proton signals of intracellular proteins and peptides to detect pH effects in MRI. Nat Med 9(8):1085–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Zijl PCM, Yadav NN (2011) Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST): what is in a name and what isn’t? Magn Reson Med 65:927–948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gore JC, Zu ZL, Wang P et al. (2017) “Molecular” MR imaging at high fields. Magn Reson Imaging 38:95–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMahon MT, Gilad AA, DeLiso MA et al. (2008) New “multicolour” polypeptide diamagnetic chemical exchange saturation transfer (DIACEST) contrast agents for MRI. Magn Reson Med 60(4):803–812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vinogradov E, Sherry AD, Lenkinski RE (2013) CEST: from basic principles to applications, challenges and opportunities. J Magn Reson 229:155–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dula AN, Arlinghaus LR, Dortch RD et al. (2013) Amide proton transfer imaging of the breast at 3 T: establishing reproducibility and possible feasibility assessing chemotherapy response. Magn Reson Med 70(1 ):216–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klomp DW, Dula AN, Arlinghaus LR et al. (2013) Amide proton transfer imaging of the human breast at 7T: development and reproducibility. NMR Biomed 26(10):1271–1277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donahue MJ, Donahue PCM, Rane S et al. (2016) Assessment of lymphatic impairment and interstitial protein accumulation in patients with breast cancer treatment-related lymphedema using CEST MRI. Magn Reson Med 75(1):345–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dula AN, Dewey BE, Arlinghaus LR et al. (2016) Optimization of 7-T chemical exchange saturation transfer parameters for validation of glycosaminoglycan and amide proton transfer of fibroglandular breast tissue. Radiology 275(1):255–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmitt B, Zamecnik P, Zaiss M et al. (2011) A new contrast in mr mammography by means of chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging at 3 Tesla: preliminary results. Rofo-Fortschr Rontg 183(11):1030–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang S, Seiler S, Wang X et al. (2018) CEST-dixon for human breast lesion characterization at 3 T: a preliminary study. Magn Reson Med 80(3):895–903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang S, Keupp J, Wang X et al. (2018) Z-spectrum appearance and interpretation in the presence of fat: Influence of acquisition parameters. Magn Reson Med 79(5):2731–2737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao Y, Yan X, Zhang ZS et al. (2019) Self-adapting multi-peak water-fat reconstruction for the removal of lipid artifacts in chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging. Magn Reson Med 82(5):1700–1712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zimmermann F, Korzowski A, Breitling J et al. (2020) A novel normalization for amide proton transfer CEST MRI to correct for fat signal-induced artifacts: application to human breast cancer imaging. Magn Reson Med 83(3):920–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krikken E, van der Kemp WJM, Khlebnikov V et al. (2019) Contradiction between amide-CEST signal and pH in breast cancer explained with metabolic MRI. NMR Biomed 32(8):e4110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krikken E, Khlebnikov V, Zaiss M et al. (2018) Amide chemical exchange saturation transfer at 7 T: a possible biomarker for detecting early response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res 20(1):51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jia GA, Abaza R, Williams JD et al. (2011) Amide proton transfer MR imaging of prostate cancer: a preliminary study. J Magn Reson Imaging 33(3):647–654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng M, Chen SZ, Yuan J et al. (2016) Chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) MR technique for liver imaging at 3.0 Tesla: an evaluation of different offset number and an after-meal and over-night-fast comparison. Mol Imaging Biol 18:274–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin HY, Raman SV, Chung YC et al. (2008) Rapid phase-modulated water-excitation steady-state free precession for fat-suppressed cine cardiovascular MR. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 10(1):1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bastiaansen JAM, Stuber M (2018) Flexible water excitation for fat-free MRI at 3T using lipid insensitive binomial off-resonant RF excitation (LIBRE) pulses. Magn Reson Med 79(6):3007–3017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamilton G, Yokoo T, Bydder M et al. (2011) In vivo characterization of the liver fat 1H MR spectrum. NMR Biomed 24(7):784–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sklenar V, Starcuk Z (1982) 1-2-1 pulse train: a new effective method of selective excitation for proton NMR in water. J Magn Reson 50:495–501 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hore P (1983) Solvent suppression in fourier transform nuclear magnetic resonance. J Magn Reson 55:283–300 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hardy PA, Recht MP, Piraino DW (1998) Fat suppressed MRI of articular cartilage with a spatial-spectral excitation pulse. J Magn Reson Imaging 8(6):1279–1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu J, Zhou J, Cai C et al. (2015) Observation of true and pseudo NOE signals using CEST-MRI and CEST-MRS sequences with and without lipid suppression. Magn Reson Med 73(4):1615–1622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pineda N, Sharma P, Xu Q et al. (2009) Measurement of hepatic lipid: high-speed T2-corrected multiecho acquisition at 1H MR spectroscopy—a rapid and accurate technique. Radiology 252(2):568–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dimov AV, Liu T, Spincemaille P et al. (2015) Joint estimation of chemical shift and quantitative susceptibility mapping (chemical QSM). Magn Reson Med 73(6):2100–2110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.By S, Barry RL, Smith AK et al. (2018) Amide proton transfer CEST of the cervical spinal cord in multiple sclerosis patients at 3T. Magn Reson Med 79(2):806–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schleich C, Muller-Lutz A, Matuschke F et al. (2015) Glycosaminoglycan chemical exchange saturation transfer of lumbar intervertebral discs in patients with spondyloarthritis. J Magn Reson Imaging 42(4):1057–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zu Z, Li K, Janve VA et al. (2011) Optimizing pulsed-chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging sequences. Magn Reson Med 66(4):1100–1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark DJ, Smith AK, Dortch RD et al. (2016) Investigating hydroxyl chemical exchange using a variable saturation power chemical exchange saturation transfer (vCEST) method at 3 T. Magn Reson Med 76(3):826–837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu J, Yadav NN, Bar-Shir A et al. (2014) Variable delay multipulse train for fast chemical exchange saturation transfer and relayed-nuclear overhauser enhancement MRI. Magn Reson Med 71(5):1798–1812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.