ABSTRACT.

This study aims to explore various barriers in accessing outpatient care among the participants from different age groups and to identify determinants associated with physician visits. The study had adopted Andersen’s Behavioral Model (ABM) of Health Services Use. A cross-sectional study design was adopted to collect data from 417 participants through a questionnaire survey. Poisson regression models were used to explore determinants for explaining the differences in outpatient care use. The regression results revealed that divergent relationships existed among age groups. Children and elderly participants tended to decrease the probability of seeking care. Elderly participants confronted more difficulties in access and were dependent on family members. Despite free care provisions, participants visited and spent their out-of-pocket expenditure mostly at non-universal health coverage (non-UHC) facilities. Convenience and the availability of specialist physicians led the higher-income parents to seek care of their children at non-UHC facilities. Highly educated people of working age preferred more self-care or institutionalized care to save time. Children up to the primary level of education were more likely to visit a doctor. We concluded that investments in education or well-informed health services provision would improve health care utilization. Findings of Andersen’s Behavioral Model variables suggested that improvements in the quality of services, medical professional skills, and efficient resource allocation may induce seeking care at UHC facilities. Consequently, it will reduce the number of referred cases, caseloads at tertiary care units, and visits to non-UHC facilities at longer distances.

INTRODUCTION

Health care services utilization faces challenges in access to care for rural populations.1 Health care service accessibility is a combination of the physical availability of services offered by health care providers and the way people access care.2 Difficulties in accessing quality health care services in rural areas lead to high levels of chronic disease and poor health outcomes.3 Obstacles in access to care are often affected by the availability of transportation and communication, physical distance, and time required to reach the facility.4–8 Furthermore, spatial accessibility to care facility contributes to appropriate health care use. Limited access to primary care causes avoidable hospitalizations and emergency department visits.9

One of the most significant attributes that affect health care utilization in rural settings is the large distance between residences and health care facilities. It is also a determinant of how long patients delay before seeking care.4,5 However, at a short distance from a health care facility, unaffordable transportation becomes a barrier.8,10,11 In addition to this, financial constraints are critical obstacles in accessing health care facilities in rural settings.3,6,12 Health care spending is a source of the economic risk of illness.13,14 Furthermore, travel cost is considered as a hurdle for seeking care at secondary and tertiary health care services.15,16 Rural residents travel more to seek care at a higher expense,16,17 which not only decreases the demand for care near to their homes but also undermines public health system’s efficiency. Furthermore, it aggravates the problem of overcrowded tertiary hospitals.18,19 Therefore, physical distance and health care costs are considered important determinants of accessing care in low- and middle-income countries.20 In response, national governments are framing different health care policies to increase the utilization of health care facilities.21

To enhance health care utilization and decrease the financial burden of diseases, health insurance is one of policies the governments had implemented. However, health insurance influences health care utilization differently among socioeconomic groups even with a high coverage rate in a country.22,23 Disparities in health care use from care-seeking behavior is influenced by factors other than insurance coverage.12,16,24–26 In developing countries, people are faced with income uncertainty risks.13 Furthermore, the poor are more vulnerable in terms of economic ability to satisfy their needs for health care and choice of health care providers.16,23,27–29 Out-of-pocket payments may push poor populations into health-related poverty.17,23,30 Besides, high fees for services are the major deterring factors of health care services use among rural residents.8,10,31 Inequalities among socioeconomic groups in health services utilization are related to timely access to care, opening hours, waiting times to see a doctor, and service quality.2,4,12,32–34 Moreover, individuals living in rural areas generally have less access to specialist doctors compared with urban populations.1,35,36

In Thailand, the universal national health service has been provided for all Thai residents under the National Health Security Act, 2002.37 However, the rural population is still confronting various barriers resulting from poor physical accessibility,4,5,10,11,31 financial burden,3,6,13,15,30 drawbacks in the quality of services under Universal Health Coverage (UHC),2,33,34,38 and willingness to visit the non-UHC facilities.16 Although Thailand is currently working on the implementation of UHC to improve access to care for all age groups of the populations.39,40 However, limited empirical work considered the dimensions of access that affect rural people. Previous studies have focused on a particular group,41–44 illness,45,46 and a comparison between locations, race, or sex.21,47–50 Moreover, the existing research in Thailand has emphasized comparison between pre- and post-UHC implementation, supply-side reform, and its achievement and monitoring progress.12,51–56 Thai government has prioritized pro-rural health development, which focuses on district hospitals and health centers.57 The policy has failed to tackle problems of underutilization of health services at UHC facilities in rural settings.16,17,25 Consequently, Thailand is unlikely to be on track and achieve the targets and indicators of health-related Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.55

Available literature regarding UHC in Thailand has focused on a health systems development using macro-level data.12,17,19,35,57 Furthermore, limited literature has assessed health care utilization in the rural settings. To the best of our knowledge, no study has assessed health care utilization among age group differences in response to the Ministry of Public Health's policy.39 Poor populations and those living in rural areas are confronted with more barriers caused by other determinants in accessing health care even under free care provision.16,36,49,51 Hence, scientific evidence to understand how influential factors affect rural residents’ care-seeking behavior is essential to achieve the desired enhancement in the utilization of UHC facilities. Therefore, this study explores different barriers in accessing health care for rural residents and care-seeking behavior among different age groups. We also examine the association of predisposing, enabling, and need factors with health services utilization. The study offers policymakers and health providers an opportunity to make improvements in health care more appropriate for each age group. It may enhance the quality of health services use among rural populations. Consequently, it will help to reduce the number of referred cases from registered hospitals in rural areas and caseloads at tertiary hospitals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study area selection and sampling.

This study was carried out in the San Kamphaeng district located in Chiang Mai province, which is connected with the Shan State of Myanmar. The topography is generally mountainous areas and grove wood with a central plain area along the Ping River. In 2016, 1,735,762 people were living in this province.58 Most of the population was in the working age (56.34%), followed by elderly (16.31%) and adolescent populations (6.79%). Gross Provincial Product increased from 222,488 million THB (Thai Baht is the official legal currency of Thailand; $US1 was 34.7984 Thai Baht during the survey)1 in 2016 to 247,831 million THB in 2018. There were 48 health care facilities that provided in-patient service.40 The district was purposively selected due to the availability of users under UHC. From this district, two-sub districts named “San Kamphaeng” and “Ton Pao” were selected.

A six-stage stratified random sampling design was applied for selecting the participants for the questionnaire survey. First, Chiang Mai province was selected because it contained the largest proportion of beneficiaries under UHC. Second, the San Kamphaeng district was selected after discussion with key informants including public health officials due to the high number of UHC enrollees. In the third stage, San Kamphaeng and Ton Pao subdistricts were chosen because they contained the largest number of beneficiaries under UHC. At step four, three villages were selected following simple random sampling. Step five included the selection of individual beneficiaries, people who had registered under UHC, through simple random sampling. Last, people in selected villages were selected according to age groups. The total population in the subdistricts was 16,151. The sample size was decided based on Yamane’s formula59 (Eq. 1). The calculated sample size was 417 and comprised 72 children (≤ 14 years), 153 working-age (15–59 years) persons, and 192 elderly (≥ 60 years) persons.

| (1) |

where n = sample size, N = total number of beneficiaries under UHC, and e = precision to be applied at 5% (0.05).

Data collection and analysis.

Data for this study were obtained from the interviewer-administered questionnaire survey in the study area. The level of health care utilization was determined by several factors as explained in Andersen’s Behavioral Model of health service use.60–62 In this study, the focus of the model remained on determinants that were associated with their use of outpatient services, physical accessibility, and out-of-pocket expenses. Information on correlated variables according to Andersen’s Behavioral Model was collected included predisposing, enabling, and need factors. Participants of the study were enrollees under UHC.

A Poisson regression model was used to examine the effect of national health insurance on health services use. The dependent variable (number of doctor visits) was discrete. It can be counted as non-negative integers. Count data models were the most appropriate for analyzing this type of data;63–66 therefore, in this study, the Poisson regression model was used to estimate the effects of factors on the magnitude change of outpatient services use. Moreover, a test for overdispersion was carried out using the Negative Binomial model, which resulted in the non-existence of the overdispersion problem. In addition to this, perceived health status was measured on a five-point Likert scale. The assigned values for its weighted average index were very poor (0.2), poor (0.4), moderate (0.6), good (0.8), and very good (1.0). Qualitative statements were noted, later refined, and applied to describe users’ reasons for utilizing out patient services, quality of health services offered by registered health care providers under UHC, and problems and needs regarding UHC.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics of study variables.

The dependent variable was the frequency of outpatient visits in the past year. Outpatient services were referred to primary care units’ visits under UHC, namely Tambon Health Promoting Hospitals, private clinics, or outpatient departments in hospitals. Information on other correlated variables was collected according to Andersen’s model. The measurement of study variables and descriptive statistics are briefly described in Supplemental Table S1.

Predisposing factors.

The findings in Supplemental Table S1 showed that the maximum number of outpatient visits increased by age. The highest amount was 11 times per person per year on average. The results reported that about 60% of both working-age and the elderly groups were married. Although more than half of the participants graduated from primary school, there was a considerable difference between working-age participants, who graduated from a higher level than primary school (49.01%), and the other two groups. Approximately 45% of working-age respondents worked in the informal sector, and more than 30% of the elderly participants were unemployed. The number of family members was three to four persons on average.

The household that belong to the children group had the highest average income at 247,383 THB per year (Supplemental Table S1), followed by the working-age (126,253 THB) and elderly groups (57,742 THB). This result indicates that more than 70% of working-age and older participants visited UHC facilities as a usual source of care, compared with about 38% for children. Moreover, older participants visited primary care units within the shortest distance on average. However, they paid a high amount of out-of-pocket medical and medicine expenses at 364.3 THB per person per year on average (range: 0–14,800 THB) and other expenses at 193.4 THB (range: 0–32,680 THB). Results revealed that the average distance and time to secondary care units increased by age. On average, children consumed the lowest time to secondary care units (22.2 minutes) and had the highest travel expense at 127.8 THB per one-way visit (range: 0–1,050 THB).

Enabling factors.

Individual income.

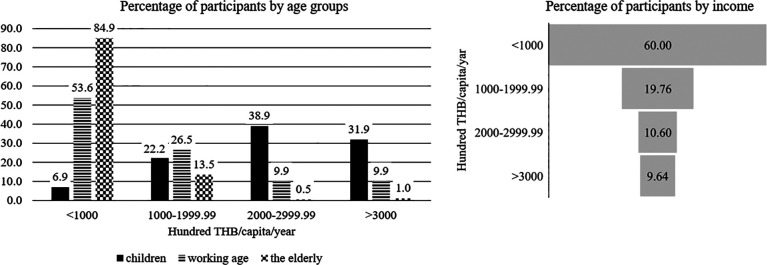

Three-fifths (60%) of the participants had the lowest income, and the percentage increased by age (84.9% for the elderly, followed by the working-age group [53.6%] and the children group [6.9%]) (Figure 1). Results showed that one out of four of the participants living in rural areas were living under the poverty line of Thailand (2,667 THB per month).67 Similarly, the percentage of those living under the poverty line increased by age. Within each group, 37.5% of elderly participants were under the poverty line, followed by the working-age (19.87%) and children’s groups (2.78%) (Supplemental Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Percentage distribution of participants by income versus age groups.

Distance and travel time to care.

Although Tambon Health Promoting Hospitals and District hospitals were designed to be located near the enrollees’ homes, participants still visited other health care units with longer distances and time. In comparison, all participants visited non-UHC units with more than one-time longer and greater time to reach Tambon Health Promoting Hospitals (Supplemental Figures S2 and S3). Surprisingly, children and elderly participants traveled/took about three times longer distance/time than traveling to District hospitals under UHC. Likewise, it was about two times greater for the working-age group.

Modes of transportation.

A motorbike was the most popular type of transport to reach primary care units. More than 70% of children, 85% of the working age, and 59% of the elderly traveled to primary care units by motorcycles (Supplemental Table S2). However, the elderly participants had a greater percentage (7.8%) of visiting primary care units by public transport (minibus) and by walking, compared with 5.2% in children and 1.2% in working-age respondents. Older persons were confronted with more mobility problems and were unable to reach even primary care units by themselves. Thus, they substituted a trip to the pharmacy or waited for a family member, which consequently caused the treatment delay or low utilization of health services (Focus Group Discussion, 2016).

In the case of the modes of transportation to reach secondary care units, the most usual type of transport was motorcycles (51%), which helped in reducing travel costs and avoided parking problems. About half of the children visited secondary care units by cars. A limited percentage of them (4.3%) traveled to secondary care units by using public transport. Nonetheless, there was a considerable difference in the percentage for the working-age group. For instance, about two-thirds (63.6%) of them reached secondary care units by motorcycles compared with those who reached by cars (22.7%). Likewise, it was about two times for the elderly. Elderly persons visited secondary care units by other modes of transportation (e.g., “sidecars, motorcycle taxis, and municipality’s ambulance services”) at a higher percentage (19.7%) than the others. Public transportation was inadequate in the study area; therefore, patients did not meet a doctor in time. The necessity of using public transport increased by age (i.e., 4% for children, 7% for working-age and 10% for elder participants, respectively) (Supplemental Table S2).

Out-of-pocket expenditures.

The participants can obtain free care under UHC. However, the burden of the cost of health care persists. Out-of-pocket expenditure was mostly due to non-UHC facility visits with 86.15% of the working-age group and 96.10% from the other two groups visiting a non-UHC facility (Supplemental Figure S4). The largest amount of out-of-pocket treatment cost and medicines was 388.1 THB per time on average (range: 0–2,000 THB) for children, followed by the elderly and working-age participants at 364.3 THB per time (range: 0–14,800 THB) and 269.1 THB per time (range: 0–5,600 THB), respectively.

Patients also had to pay for other expenses such as medical instruments, food, snacks, and drinks. Other expenses generally occurred during their visits to health care units. Participants in the working-age group mostly incurred these expenses while visiting UHC health care providers at about 76% (32.3 THB per time on average). The elderly group spent 80% (193.4 THB per time) in visiting UHC facilities (Supplemental Figure S5), ranging from 0 to 32,680 THB (Supplemental Table S1). However, the children group still paid for other expenses by themselves at non-UHC facilities (62.07%; 53.5 THB per time; range: 0–600 THB) at a higher percentage than UHC facilities (37.93%).

Out-of-pocket travel costs.

Another financial burden that occurred during visits was travel costs. In comparison, children preferred spending about 5 times higher to reach non-UHC than UHC facilities (Supplemental Figure S6). However, it was not much different among elderly and the working-age participants.

Results from Poisson regressions showed that working-age participants with higher incomes were more likely to visit a physician, although the opposite was seen among elderly participants. Moreover, working-age persons were less likely to visit a doctor for all types of occupations. The elderly participants who were self-employed tended to have a 14.5% increase in outpatient visits. Children who were not in a labor force or students tended to have a 43.6% increase in visits (Table 1). The number of visits was not affected by holding other valid health insurance for working-age groups. However, participants who visited UHC facilities as their usual sources of care tended to have increases of 33.7%, 16.74%, and 49.6% in the number of outpatient visits for children, working-age, and the elderly groups, respectively. Children tended to have a 4.3% decrease in visits with a longer distance to primary care units. Even with longer distances to primary care and secondary care units, elder persons were more likely to visit a doctor, and working-age participants were more likely to visit primary care units with longer time consumption. Despite a very limited increase in the percentage of visits, participants preferred spending out-of-pocket expenses at health care facilities. Nonetheless, with the higher the cost of travel, fewer elderly participants were expected to visit a doctor.

Table 1.

Results of outpatient services use from the Poisson regression model

| Children (N = 72) | Working age (N = 151) | Elderly (N = 192) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Coefficient | P value | Coefficient | P value | Coefficient | P value |

| Predisposing factors | ||||||

| Age | −0.0480** | 0.048 | 0.0025 | 0.593 | −0.0237*** | 0.000 |

| Sex | −0.0440 | 0.705 | −0.1693* | 0.054 | 0.4121*** | 0.000 |

| Education (up to primary) | 0.3990*** | 0.002 | −0.0157 | 0.865 | 0.0440 | 0.634 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | – | – | 0.0950 | 0.533 | −0.3449*** | 0.000 |

| Couple | – | – | 0.0750 | 0.5 | −0.4568*** | 0.000 |

| Family size | 0.0003 | 0.995 | −0.0634** | 0.028 | 0.0764*** | 0.000 |

| Enabling factors | ||||||

| Current income | −1E−06 | 0.126 | 0.0000* | 0.077 | −3E−06*** | 0.000 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| Informal sector | – | – | −1.8760*** | 0.000 | −0.0793 | 0.247 |

| Self-employed | – | – | −2.0110*** | 0.000 | 0.1454** | 0.048 |

| Unemployed | 0.4360* | 0.053 | −1.9040*** | 0.000 | – | – |

| Having other valid health insurances | 0.0300 | 0.802 | −0.3530** | 0.014 | −0.6340*** | 0.000 |

| UHC as usual sources | 0.3370*** | 0.008 | 0.1674** | 0.047 | 0.4959*** | 0.000 |

| Distance to care | ||||||

| PCUs | −0.04330* | 0.059 | −0.0050 | 0.638 | 0.0319** | 0.017 |

| SCUs | 0.00230 | 0.868 | −0.0033 | 0.581 | 0.0476*** | 0.000 |

| Travel time to care | ||||||

| PCUs | 0.0116 | 0.181 | 0.0084* | 0.087 | 0.0095* | 0.070 |

| SCUs | 0.0043 | 0.449 | 0.0026 | 0.246 | −0.0048*** | 0.000 |

| Out-of-pocket expenses | ||||||

| Medical and medicines | 0.0003* | 0.05 | 0.0001** | 0.026 | 0.0000*** | 0.000 |

| Travel and others | 0.0005* | 0.074 | 0.0008** | 0.021 | −0.0007*** | 0.002 |

| Need factors | ||||||

| Health status | −0.3620 | 0.329 | −0.1700 | 0.421 | −0.5250*** | 0.000 |

| Number of chronic illnesses | 0.2920* | 0.089 | 0.2682*** | 0.000 | 0.1325*** | 0.000 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Never | – | – | −0.0420 | 0.789 | 0.5880*** | 0.000 |

| Yes | – | – | −0.0620 | 0.721 | 0.0130 | 0.916 |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||

| Never | – | – | −0.2260 | 0.241 | −0.1690 | 0.104 |

| Yes | – | – | −0.2780 | 0.152 | 0.2190** | 0.032 |

| Constant | 1.6570*** | 0.000 | 3.7040*** | 0.000 | 2.8790*** | 0.000 |

* P ≤ 0.1, ** P ≤ 0.05, and *** P ≤ 0.01. PCUs = primary care units; SCUs = secondary care units; UHC = universal health coverage.

Need factors.

Percentages of participants with at least one physician-diagnosed chronic disease increased by age (70% for the elderly, 42.38% for the working-age, and 11.11% for children groups; Supplemental Table S1). The number of chronic illnesses significantly affected the number of outpatient visits for all age groups. Children tended to have a 29.2% increase in visits, followed by the working-age (26.8%) and the elderly (13.3%) groups (Table 1). Health services use was influenced by health status only for the elderly, who tended to have a 52.5% decrease in visits when they perceived their health as good. Elderly participants who had consumed alcohol tended to have a 21.9% increase in the number of visits. The working-age group had the highest percentage of persons who had continued smoking (14.57%) and consuming alcohol (34.44%) within the past year (Supplemental Table S1).

Health services utilization.

Results revealed that the majority of working-age and older participants visited UHC facilities as their usual source of care, whereas children visited non-UHC facilities as their usual sources of care within the past year (Supplemental Table S3). If they had choices, parents preferred visiting non-UHC facilities at 76.39%, whereas about 50% of the working age and the elderly preferred visiting UHC facilities as their first choice of treatment.

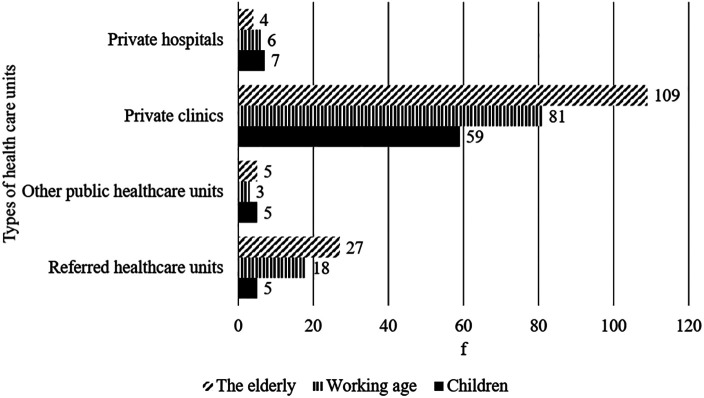

Among our study subjects, more than 100 elderly persons used to visit private clinics, followed by working-age (81 persons), and children participants (59 persons), at an average of 3 to 4 times per year (Supplemental Table S4; Figure 2). Surprisingly, 50 persons were referred from registered health care units. Also, the number increased by age, with a maximum of 96 times per year or eight 8 per year on average within the elderly group. Thirty persons visited other public health care units or private hospitals and spent health care costs without reimbursement. Also, children visited private hospitals at a maximum of 12 and 6 times per year on average, which was about double that among working-age groups.

Figure 2.

Number of participants who used to obtain outpatient care at other health care units.

Results of statistical analysis.

A description of the variables used in the analysis while using Poisson regression models is illustrated in Supplemental Table S1. The significance of the likelihood ratio test for all three models showed that they were pointing toward the appropriateness of the selected independent variables. Three dimensions associated with the frequency of outpatient visits (predisposing, enabling, and need factors) are represented in Table 1.

Participants’ needs and suggestions.

This issue reflected needs and suggestions concerning the participation under UHC facilities. The main drawbacks of health services provided under UHC facilities are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Qualitative statement analysis

| 1. Difficulties in access | 5. Limitation of choices in health care facility selection |

| 2. Less availability of staff | 6. Poor service quality |

| 3. Long waiting time for services | 7. Demeanor of health personnel |

| 4. Expansion of coverage for benefit packages | 8. Increase in information dissemination |

Source: Field survey 2016.

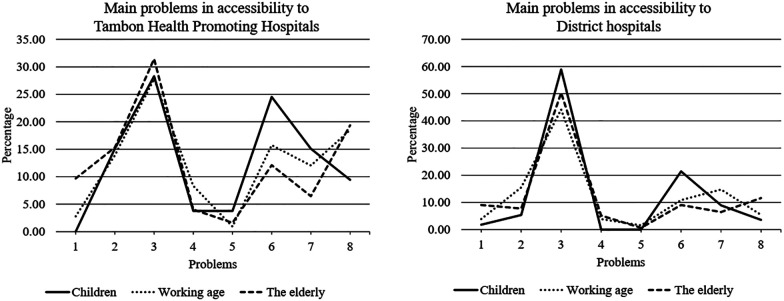

The participants perceived that a long waiting time was the major obstacle for obtaining services at UHC facilities (30%) at Tambon Health Promoting Hospitals; this was also found among about 60% for children, followed by the elderly (50.32%) and working-age participants (44.19%) at District hospitals (Figure 3). After a long waiting time for services, children were not satisfied with the service quality provided under Tambon Health Promoting Hospitals at 24.53%, followed by working-age (15.74%) and older respondents (12.10%). However, about 40% of working-age participants perceived that UHC health care providers should have increased the dissemination of UHC information. The third aspect that all participants suggested was a lack of staff, which might be related to long waiting times at Tambon Health Promoting Hospitals. Also, the second problem children participants perceived at District hospitals was service quality (21.43%), followed by the demeanor of health personnel. However, 15.50% of working-age respondents also reported that there was an inadequacy of staff at District hospitals, problems of the demeanor of health personnel (14.73%), and poor service quality (10.85%). Similar to Tambon Health Promoting Hospitals, elderly participants perceived that insufficient information dissemination was the second main drawback for District hospitals. In contrast to the other two groups, 9.03% of the elderly confronted difficulties in access to District hospitals.

Figure 3.

Accessibility problems to Tambon Health Promoting Hospitals and District hospitals.

DISCUSSION

Despite free care provision, disparities in access to care existed in rural Thailand. These disparities resulted from other factors besides health insurance, implying that having health insurance may not guarantee the use of needed health services.68 Differences in health care use among socioeconomic groups can be influenced by health insurance even a high coverage rate, which is also confirmed in the literature.12,16,24–26 The findings showed that the number of outpatient visits increased by age. Participants in the working-age group had more health care visits for chronic conditions or regular checkups.10 However, children and elderly participants tended to decrease the probability of seeking care. Children had better health status by receiving health services provided by Tambon Health Promoting Hospitals, such as vaccination and dentistry services, regularly at school. However, elderly persons were confronted with more barriers to reach the facilities in comparison. Elderly participants depended more on family members than on their spouses to visit health care units. Previous study revealed that family support is needed for older people.69 Therefore, local administration may be involved in providing ambulance services, especially for people who need to follow up at District hospitals regularly. Home visit activities associated with Tambon Health Promoting Hospitals and communities will also enhance the health status of persons with high dependency. Our findings showed that elderly men were more likely to seek care than elderly women. In contrast, men and a higher number of family members decreased the probability of seeking treatment of working-age participants. Although about half of the participants finished primary school, half of the working-age participants graduated at a higher level than primary. Our findings suggest that high-educated people preferred self-care or institutionalized care to save time.16 Forty-five percent of them worked in the informal sector on a daily basis. Children who studied up to primary school were expected to have an increase in the number of doctor visits, implying that education or well-informed health services provision would increase visits. It has been reported that investments in education can improve health care utilization.69

The findings of this study showed that one out of four of the participants was living under the poverty line.67 Moreover, the percentage of individuals within the lowest income group increased by age. However, income still reflected different choices of health care unit selection. Higher-income participants were more likely to seek care than low-income participants. Our findings are consistent with earlier studies that revealed that the use of health services is greater among higher-income group participants.16,27–29 The results reported that having other health insurance did not help to increase the number of outpatient visits, whereas having UHC facilities as a usual source of care did, implying that free care is still necessary for the poor in rural settings. The results showed that the average distance and time to health care units increased by age. Moreover, participants still visited non-UHC facilities with more than one to three times longer distance and time than the registered ones under UHC. Results from Poisson regression models indicated that fewer children visited health care facilities the longer the distance to primary care units; the same was found among elderly participants visiting secondary care units with higher time consumption, travel cost, and other expenses. In contrast, working-age participants were more likely to seek care at non-UHC primary care units despite long travel distance or time consumption. Previous studies revealed that increased travel distance, time, and transportation are often mentioned as problems in discussions of health services utilization.3,10,31,70 A lack of physical accessibility and inconvenient transport were the leading causes of low utilization, treatment delay, and visits to non-UHC facilities. Previous studies showed that a lack of specialist doctors may influence people's decision to visit non-UHC facilities that are at longer distances and when medical and medicine expenses are paid for.6,16 Furthermore, a study reported that rural residents were found to have poor health because of difficulty in attracting and retaining physicians and maintaining health services in rural settings.3

Most of the participants could not afford a car or their own vehicle. Furthermore, the results showed that more than half of them reached health care units through motorcycles. Our findings are consistent with an earlier study reporting that financial and geographic barriers to health care services are reduced by the use of motorcycles.20 Half of the children participants could afford a car, especially for reaching secondary care units; however, a limited percentage of them traveled by public transportation. In contrast, elderly persons had a greater percentage of visiting primary care units by minibus or walking as well as other types of transport (e.g., “motorcycle taxis and ambulance services”). Reluctance to seek care in rural areas was often caused by insufficient public transportation,3 which may cause a treatment delay or self-treatment, especially when patients are referred to other health care providers a long distance away with higher time consumption and cost. People who had family members or friends who could provide transportation had more visits than those who did not.10 Therefore, sufficient routine public transportation and the availability of ambulance services, especially for referred and emergency cases from registered hospitals, should be provided to mitigate problems with access.

The findings of this study revealed that out-of-pocket expenditures were positively associated with the number of visits for the children and working-age participants. Most of these out-of-pocket expenses resulted from visiting non-UHC facilities. In addition, a service charge per visit and some medical instruments were not reimbursable under UHC. Previous studies also revealed that the financial burden of illnesses in poor households is high, with estimates ranging between 10 and 20% of the household’s per capita consumption.71,72 Hence, government intervention through UHC should help in reducing out-of-pocket expenditures for beneficiaries.73 However, distance costs are often seen to negatively affect health care utilization.74 Thus, health care units located near home may help to reduce travel costs and increase health care services utilization. Also, improving the quality of UHC facilities, which should be the nearest health care providers, may gain more trust, reduce referred cases, and easier access to care for enrollees. Our results showed that the number of physician-diagnosed chronic illnesses was the most crucial need factor for all age groups and increased by age. Besides, health services use was affected by health status, especially for the elderly. More than half of elderly aprticipants decreased their number of visits when they perceived their health as good. A study also revealed that lower health status was associated with increased health care visits.10

Although UHC guarantees health care coverage for all Thai citizens, some rural populations still seek care at non-UHC facilities. The long waiting time and service quality were major obstacles in access to both Tambon Health Promoting Hospitals and District hospitals for all age groups. Previous studies revealed that delaying care caused by previous bad health care experiences is a barrier in access to health care units,75 in addition to problems with availability of staff, which may be related to long waiting times for services at UHC facilities. Also, a lack of trained physicians and a scarcity of services caused reluctance to seek health care in rural areas.3 The elderly perceived difficulty in access to District hospitals. Our findings are consistent with a study that revealed that difficulty in access to health care decreases health care utilization.76 Therefore, improving the provision of services under UHC, including promotion, training, and career development of rural health care professionals, may increase the demand for outpatient care at UHC facilities. Furthermore, it is essential to align resource allocation with the preferences of the rural populations and mitigate financial constraints in rural areas.3,18

Study limitations.

This study was conducted among UHC health care providers located in San Kamphaeng District. Factors affecting health care use may be different in other parts of the country. The study has focused on the demand-side factors. Supply-side factors might produce different findings. We measured the use of health services only within 12 months prior the interview, which might not represent the continuity of care.

CONCLUSION

Thai citizens have been covered by UHC. However, rural residents were confronted with barriers in access and financial burden across different age groups. The problems caused by health care–seeking behavior, a lack of choice of transport, and out-of-pocket expenses influenced the frequency of outpatient visits through predisposing, enabling, and need factors. Drawbacks while obtaining health services, such as long waiting time, insufficient health personnel, and lack of information dissemination, has reduced utilization of UHC facilities. Consequently, some beneficiaries visited non-UHC facilities as an alternate source of health care. However, UHC is still essential for the poor. It helps to diminish their health care cost burden, distance to care, and time consumption compared with visiting non-UHC health care units. The findings of the study help planners and policymakers to coordinate efforts to improve the accessibility of health care services for people living in rural areas based on the understanding of different problems regarding physical access. Moreover, improving the quality of health services at UHC facilities and allocating resources to health care providers in rural areas may help lessen the number of referred cases, caseloads at tertiary health care units, and visits to non-UHC facilities at longer distances with higher health care costs.

Supplemental material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all public health officials and staff for their support during data collection, all study participants who spared their time for interviews, and the two anonymous reviewers and editor of this journal for their constructive comments, whose comments improved the quality of our work. The first author accredits the support of the Royal Thai Government Fellowship for the award of a Ph.D. scholarship.

Note: Supplemental material appears at www.ajtmh.org.

References

- 1.Caldwell JT, Ford CL, Wallace SP, Wang MC, Takahashi LM, 2017. Racial and ethnic residential segregation and access to health care in rural areas. Health Place 43: 104–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan K, 2015. Introduction to Comparative Health Systems. Available at: http://cugh.org/sites/default/files/content/resources/modules/To Post Both Faculty and Trainees/34_Introduction_To_Comparative_Health_Care_Systems_FINAL.pdf. Accessed June 7, 2016.

- 3.Douthit N, Kiv S, Dwolatzky T, Biswas S, 2015. Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Public Health 129: 611–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ensor T, Cooper S, 2004. Overcoming barriers to health service access: influencing the demand side. Health Policy Plan 19: 69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Segall M, Tipping G, Lucan H, Dung TV, Tam NT, Vinh DX, Huong DL, 2000. Health Care Seeking by the Poor in Transitional Economies: The Case of Vietnam. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaikh BT, Hatcher J, 2004. Health seeking behaviour and health service utilization in Pakistan: challenging the policy makers. J Public Health (Bangkok) 27: 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strasser R, 2003. Rural health around the world: challenges and solutions. Fam Pract 20: 457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tamiya N, Araki S, Kobayashi Y, Yamashita K, Murata K, Yano E, 1996. Gender difference in the utilization and users’ characteristics of community rehabilitation programs for cerebrovascular disease patients in Japan. Int J Qual Health Care 8: 359–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mudd AE, Michael YL, Diez-Roux AV, Maltenfort M, Moore K, Melly S, Lê-Scherban F, Forrest CB, 2020. Primary care accessibility effects on health care utilization among urban children. Acad Pediatr 20: 871–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arcury TA, Preisser JS, Gesler WM, Powers JM, 2005. Access to transportation and health care utilization in a rural region. J Rural Health 21: 31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barber C, Jeremy C, Rossi E, Phelan J, 2016. Redefining access: how community managed transport is improving access to essential health care services in rural madagascar. J Transp Health 3: 4–61. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Limwattananon S, Neelsen S, O’Donnell O, Prakongsai P, Tangcharoensathien V, van Doorslaer E, Vongmongkol V, 2015. Universal coverage with supply-side reform: the impact on medical expenditure risk and utilization in Thailand. J Public Econ 121: 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yaya Bocoum F, Grimm M, Hartwig R, 2018. The health care burden in rural Burkina Faso: consequences and implications for insurance design. SSM Popul Health 6: 309–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neelsen S, Limwattananon S, O’Donnell O, van Doorslaer E, 2019. Universal health coverage: a (social insurance) job half done? World Dev 113: 246–258. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cockroft A, Monasta L, Onishi J, Omer K, 2001. Service Delivery Survey: Second Cycle 2000. Dhaka, Bangladesh: CIETcanada and Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

- 16.Suraratdecha C, Saithanu S, Tangcharoensathien V, 2005. Is universal coverage a solution for disparities in health care? Findings from three low-income provinces of Thailand. Health Policy (New York) 73: 272–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Limwattananon S, Tangcharoensathien V, Prakongsai P, 2007. Catastrophic and poverty impacts of health payments: results from national household surveys in Thailand. Bull World Health Organ 85: 600–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Kong Q, de Bekker-Grob EW, 2019. Public preferences for health care facilities in rural China: a discrete choice experiment. Soc Sci Med 237: 112396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thoresen SH, Fielding A, 2011. Universal health care in Thailand: concerns among the health care workforce. Health Policy (New York) 99: 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muir JA, 2018. Another mHealth? Examining motorcycles as a distance demolishing determinant of health care access in south and Southeast Asia. J Transp Health 11: 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panezai S, Ahmad MM, Saqib SE, 2017. Factors affecting access to primary health care services in Pakistan: a gender-based analysis. Dev Pract 27: 813–827. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makinen M. et al. , 2000. Inequalities in health care use and expenditures: empirical data from eight developing countries and countries in transition. Bull World Health Organ 78: 55–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pannarunothai S, Mills A, 1997. The poor pay more: health-related inequality in Thailand. Soc Sci Med 44: 1781–1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng SH, Chiang TL, 1997. The effect of universal health insurance on health care utilization in Taiwan. JAMA 278: 89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donnell OO, 2007. Access to health care in developing countries: breaking down demand side barriers. Cad Saude Publica 23: 2820–2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mendoza-Sassi R, Béria JU, Barros AJD, 2003. Outpatient health service utilization and associated factors: a population-based study. Rev Saude Publica 37: 372–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asenso-Okyere WK, Anum A, Osei-Akoto I, Adukonu A, 1998. Cost recovery in Ghana: are there any changes in health care seeking behaviour? Health Policy Plan 13: 181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hidayat B, Thabrany H, Dong H, Sauerborn R, 2004. The effects of mandatory health insurance on equity in access to outpatient care in Indonesia. Health Policy Plan 19: 322–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nyamongo IK, 2002. Health care switching behaviour of malaria patients in a Kenyan rural community. Soc Sci Med 54: 377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sauceda-Valenzuela AL, Wirtz VJ, Santa-Ana-Téllez Y, de la Luz Kageyama-Escobar M, 2010. Ambulatory health service users’ experience of waiting time and expenditure and factors associated with the perception of low quality of care in Mexico. BMC Health Serv Res 10: 178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nemet GF, Bailey AJ, 2000. Distance and health care utilization among the rural elderly. Soc Sci Med 50: 1197–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng SH, Yang MC, Chiang TL, 2003. Patient satisfaction with and recommendation of a hospital: effects of interpersonal and technical aspects of hospital care. Int J Qual Health Care 15: 345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hasin MAA, Seeluangsawat R, Shareef MA, 2001. Statistical measures of customer satisfaction for health care quality assurance: a case study. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 14: 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunt KA, Gaba A, Lavizzo-Mourey R, 2005. Racial and ethnic disparities and perceptions of health care: does health plan type matter? Health Serv Res 40: 551–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Towse A, Mills A, Tangcharoensathien V, 2004. Learning from Thailand’s health reforms. BMJ 328: 103–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wibulpolprasert S, Pengpaibon P, 2003. Integrated strategies to tackle the inequitable distribution of doctors in Thailand: four decades of experience. Hum Resour Health 1: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Office of the Council of State, 2002. The National Health Security Act, 2002. Available at: http://nih.dmsc.moph.go.th/law/pdf/031.pdf. Accessed February 11, 2021.

- 38.Wattanapisit A, Saengow U, 2018. Patients’ perspectives regarding hospital visits in the universal health coverage system of Thailand: a qualitative study. Asia Pac Fam Med 17: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ministry of Public Health, 2019. Directions for Driving the Accelerated Policy Implementation under the Ministry of Public Health, Fiscal Year 2020. Available at: https://www.rbpho.moph.go.th/upload-file/doc/files/30092019-040533-7050.pdf. Accessed February 11, 2021.

- 40.Chiang Mai Provincial Office, 2020. Summary Report of Chiang Mai Province. Available at: http://www.chiangmai.go.th/managing/public/D8/8D22Oct2020145452.pdf. Accessed February 4, 2021.

- 41.Terraneo M, 2015. Inequities in health care utilization by people aged 50+: evidence from 12 European countries. Soc Sci Med 126: 154–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vázquez ML, Terraza-Núñez R, S-Hernández S, Vargas I, Bosch L, González A, Pequeño S, Cantos R, Martínez JI, López LA, 2013. Are migrants health policies aimed at improving access to quality healthcare? An analysis of Spanish policies. Health Policy (New York) 113: 236–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bright T, Felix L, Kuper H, Polack S, 2017. A systematic review of strategies to increase access to health services among children in low and middle income countries. BMC Health Serv Res 17: 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Limwattananon S, Tangcharoensathien V, Prakongsai P, 2010. Equity in maternal and child health in Thailand. Bull World Health Organ 88: 420–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zahnd WE, McLafferty SL, Eberth JM, 2019. Multilevel analysis in rural cancer control: a conceptual framework and methodological implications. Prev Med (Baltim) 129: 105835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Buys KC, Selleck C, Buys DR, 2019. Assessing retention in a free diabetes clinic. J Nurse Pract 15: 301–305. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Varga LM, Surratt HL, 2014. Predicting health care utilization in marginalized populations: black, female, street-based sex workers. Womens Health Issues 24: e335–e343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Herberholz C, Phuntsho S, 2018. Social capital, outpatient care utilization and choice between different levels of health facilities in rural and urban areas of Bhutan. Soc Sci Med 211: 102–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yiengprugsawan V, Carmichael GA, Lim LLY, Seubsman SA, Sleigh AC, 2010. Has universal health insurance reduced socioeconomic inequalities in urban and rural health service use in Thailand? Health Place 16: 1030–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sricharoen T, Buchenrieder G, Dufhues T, 2008. Universal health-care demands in rural Northern Thailand: gender and ethnicity. Asia-Pac Dev J 15: 65–87. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yiengprugsawan V, Carmichael GA, Lim LLY, Seubsman S, Sleigh AC, 2011. Explanation of inequality in utilization of ambulatory care before and after universal health insurance in Thailand. Health Policy Plan 26: 105–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mee-Udon F, 2014. Universal health coverage scheme impact on well-being in rural Thailand. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 27: 456–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aungkulanon S, Tangcharoensathien V, Shibuya K, Bundhamcharoen K, Chongsuvivatwong V, 2016. Post universal health coverage trend and geographical inequalities of mortality in Thailand. Int J Equity Health 15: 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ghislandi S, Manachotphong W, Perego VME, 2014. The impact of universal health coverage on health care consumption and risky behaviours: evidence from Thailand. Health Econ Policy Law 10: 251–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Witthayapipopsakul W, Kulthanmanusorn A, Vongmongkol V, Viriyathorn S, Wanwong Y, Tangcharoensathien V, 2019. Achieving the targets for universal health coverage: how is Thailand monitoring progress? WHO South-East Asia J Public Health 8: 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tangcharoensathien V, Limwattananon S, Patcharanarumol W, Thammatacharee J, Jongudomsuk P, Sirilak S, 2015. Achieving universal health coverage goals in Thailand: the vital role of strategic purchasing. Health Policy Plan 30: 1152–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tangcharoensathien V, Witthayapipopsakul W, Panichkriangkrai W, Patcharanarumol W, Mills A, 2018. Health systems development in Thailand: a solid platform for successful implementation of universal health coverage. Lancet 3⩽1: 6736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Department of Provincial Administration, 2021. Number of Population in Chiang Mai Province. Available at: https://stat.bora.dopa.go.th/new_stat/webPage/statByYear.php. Accessed February 5, 2021.

- 59.Yamane T, 1973. Statistics: An Introduction Analysis, 3rd edition. New York, NY: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aday LA, Andersen R, 1974. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res 9: 208–220. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Andersen RM, Davidson PL, Baumeister SE, 2013. Changing the US Healthcare System: Key Issues in Health Services Policy and Management, 4th edition. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown C, Barner J, Bohman T, Richards K, 2009. Andersen health care utilization model for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) use in African Americans. J Altern Complement Med 5: 911–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coxe S, West SG, Aiken LS, 2009. The analysis of count data: a gentle introduction to Poisson regression and its alternatives. J Pers Assess 91: 121–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Deb P, Norton EC, 2018. Modeling health care expenditures and use. Annu Rev Public Health 39: 489–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Famoye F, Wulu JT, Singh K, 2004. On the generalized Poisson regression model with an application to accident data. J Data Sci 2: 287–295. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu B, Meng Q, Collins C, Tolhurst R, Tang S, Yan F, Bogg L, 2010. How does the new cooperative medical scheme influence health service utilization? A study in two provinces in rural China. BMC Health Serv Res 10: 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Office of The National Economic and Social Development Board, 2018. Situations Report on Regional Poverty and Income Inequality in Thailand. Available at: https://www.nesdc.go.th/ewt_w3c/ewt_dl_link.php?filename=social&nid=10858. Accessed June 29, 2020.

- 68.Hong YR, Samuels SK, Huo JH, Lee N, Mansoor H, Duncan RP, 2019. Patient-centered care factors and access to care: a path analysis using the Andersen behavior model. Public Health 171: 41–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Quashie NT, Pothisiri W, 2019. Rural-urban gaps in health care utilization among older Thais: the role of family support. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 81: 201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Collins B, Borders TF, Tebrink K, 2007. Utilization of prescription medications and ancillary pharmacy services among rural elders in west Texas: distance barriers and implications for telepharmacy. J Health Hum Serv Adm 30: 75–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Counts CJ, Skordis-Worrall J, 2016. Recognizing the importance of chronic disease in driving healthcare expenditure in Tanzania: analysis of panel data from 1991 to 2010. Health Policy Plan 31: 434–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang Q, Fu AZ, Brenner S, Kalmus O, Banda HT, De Allegri M, 2015. Out-of-pocket expenditure on chronic non-communicable diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa: the case of rural Malawi. PLoS One 10: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Singh P, Mukherjee K, 2017. Cost-benefit analysis and assessment of quality of care in patients with hemophilia undergoing treatment at National Rural Health Mission in Maharashtra, India. Value Health Reg Issues 12: 101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ha NTH, Berman P, Larsen U, 2002. Household utilization and expenditure on private and public health services in Vietnam. Health Policy Plan 17: 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tabaac AR, Solazzo AL, Gordon AR, Austin SB, Guss C, Charlton BM, 2020. Sexual orientation-related disparities in healthcare access in three cohorts of U.S. adults. Prev Med (Baltim) 132: 105999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goins RT, Williams KA, Carter MW, 2005. Perceived barriers to health care access among rural older adults: a qualitative study. J Rural Health 21: 206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.