ABSTRACT.

Vietnam is a rabies-endemic country where eating dog meat is customary. However, the risks of rabies transmission to dog slaughtering and processing workers have not been identified. This study aimed to determine the rabies neutralizing antibody (NTA) and risk factors in dog slaughterers to propose appropriate intervention methods for this occupational group. In 2016, a cross-sectional study on NTA against rabies virus and related factors was conducted among 406 professional dog slaughterers in Vietnam. The participants were interviewed using a structured questionnaire, and their sera were tested for rabies NTA by a rapid focus fluorescence inhibition test. Statistical algorithms were used to analyze the data. The results showed that most of the professional dog butchers (344/406 subjects, 84.7%) had no rabies NTA. Interestingly, 7.8% (29/373) had NTA without a rabies vaccination history. Over 5 years of experience as a dog butcher was positively associated with the presence of NTA in unvaccinated individuals (OR = 6.16, P = 0.001). The NTA in vaccinated butchers was present in higher titer and for longer persistence to those of other previously reported professionals, which is possibly as a result of multiple exposures to low levels of rabies virus antigens during dog slaughtering. Our study demonstrated that professional dog butchers in Vietnam are at a high risk of rabies virus infection, apart from those with common bite experiences. In countries where dog meat consumption is customary, rabies control and prevention activities should focus on safety during dog trading and slaughtering.

INTRODUCTION

Rabies is an acute viral encephalitis disease caused by the rabies virus, which is mainly transmitted from animal to animal or from animal to human, through a bite or lick on an open wound by an animal infected with the rabies virus.1,2

In Vietnam, a total of 497 human deaths as a result of rabies were reported by the National Rabies Program in the period 2008–2013, of which 475 (95.6%) deaths were caused by dog bites and 22 (4.4%) were caused by exposure to dog slaughtering. Of the victims who died of exposure to rabies virus during the slaughtering process, 50% were professional dog butchers and the remaining 50% were nonprofessional butchers.3,4 Every year in Vietnam, there are approximately five million dogs slaughtered for food5; Nguyen et al.6 reported that approximately 2% of dogs in slaughterhouses are infected with rabies. This suggests that those working in dog slaughterhouses are at an increased risk of rabies compared with the rest of the ordinary population. Despite this, there is little information on the incidence of rabies among professional dog butchers, on the measures they take to mitigate their risk of exposure and subsequent infection, and on the possibility of the acquired antibodies to rabies virus as a result of their continuous exposure.

Hanoi, the capital of Vietnam, contains many dog slaughterhouses that supply dog meat to the area and the surrounding cities and provinces. Dogs for slaughter are obtained from Vietnam or via illegal import from neighboring countries. There are concerns that the slaughtering of dogs and the methods used for processing dog meat may propagate transmission of rabies among those working as dog slaughterers. However, the likelihood of rabies infection occurring after exposure to an animal infected with the rabies virus depends on a number of factors, including dose, route of exposure, site of exposure, host immunity, and receipt of appropriate rabies pre-exposure or postexposure treatment regimen.1,2,7

The objective of this study was to investigate risk factors for rabies exposure and to determine the presence of neutralizing antibodies against rabies among professional dog butchers working in dog slaughterhouses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows: work as a dog butcher in dog slaughterhouses in Hanoi; age ≥ 18 years; perform dog slaughtering for business purposes continuously for ≥ 30 days; have a main income primarily from dog slaughtering activities; participate in one or more stages of the process, including catching dogs, dog feathering, preparing dog meat, and cleaning the dog slaughter areas; have no acute illness at the time of study participation; have available certificates of rabies vaccination (if rabies vaccination reported); and volunteer to participate in the study.

Information collection and laboratory testing.

The study was conducted between March 2016 and December 2016. The volunteers were interviewed by staff at the Hanoi Center for Disease Control at the community medical stations using a structured questionnaire. The collected information consisted of demographic information, years of experience as a professional dog butcher, history of rabies vaccination, number of dogs slaughtered daily, risk of acquiring rabies during butchering, and methods used to protect themselves against rabies during butchering. After the interview, 3–5 mL of blood was collected from the volunteers using aseptic techniques. Sera were separated and tested for neutralizing antibodies (NTA) against rabies by rapid fluorescence focus inhibition test (RFFIT).1,8

Sera were screened individually at 1:5, 1:25, 1:125, and 1:625 dilutions in cell culture medium. Each diluted serum sample (0.1 mL) was mixed with an equal volume of challenge virus (CVS strain) containing 50 FFD50 (Focus Forming Dose) in a cell culture plate. The mixture was incubated for 90 minutes at 37°C. After incubation, 0.2 mL of Neuroblastoma (NA) cells were added at a concentration of 1 × 106/mL. The plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 24 hours. After 24 hours of incubation, fluorescent staining with monoclonal antibodies against rabies virus was performed. The foci were observed and calculated under a fluorescence microscope at 450 nm and 160–200 magnification. The NTA of testing sera was calculated using the Reed and Muench formula.8 The serum sample was considered to be sufficiently protected against rabies virus when the NTA titer was ≥ 0.5 IU/mL.1,8

Data analysis.

Subject data were stratified by risk of exposure, rabies vaccination status, and the type of vaccine received. Separate analyses were conducted using the serological data. We drew a scatter plot, calculated the Pearson correlation number, and tested the correlation pairwise using STATA software version 14.2. Multivariate regression analysis was used to identify factors associated with the risk of rabies virus exposure. All statistical analyses were performed using Epidata 3.1 and SPSS version 16.

Ethics approval.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Department of Health, Hanoi, Vietnam.

RESULTS

A total of 406 participants were interviewed from of 92/92 dog slaughterhouses in 6/30 districts in Hanoi using a structured questionnaire; their sera samples were tested for NTA against rabies virus. Table 1 shows that the demographic details of the respondents. were aged 18–74 years (mean = 37.39 ± 12.26), with 53% (215/406) of respondents being male. Altogether, 221 (54.5%) respondents had secondary education, 100 (24.6%) graduated from high school, 63 (15.5%) graduated from primary school, and 22 (5.4%) had college degrees.

Table 1.

Demographics of butchers working at dog slaughterhouses in Vietnam (N = 406)

| Characteristics | Number of butchers (%) | Total n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||

| Sex | 215 (53.0) | 191 (47.0) | 406 (100) | |

| Age | ||||

| < 35 | 94 (23.2) | 75 (18.4) | 169 (41.6) | |

| 35–44 | 60 (14.8) | 64 (15.8) | 124 (30.6) | |

| ≥ 45 | 61 (15.0) | 52 (12.8) | 113 (27.8) | |

| Education background | ||||

| Primary school | 31 (7.6) | 32 (7.9) | 63 (15.5) | |

| Secondary school | 123 (30.3) | 98 (24.2) | 221 (54.5) | |

| High school | 52 (12.8) | 48 (11.8) | 100 (24.6) | |

| College/University | 9 (2.2) | 13 (3.2) | 22 (5.4) | |

| Period of employment (years) | ||||

| < 5 | 103 (25.4) | 91 (22.4) | 194 (47.8) | |

| 5–10 | 78 (18.9) | 71 (17.8) | 149 (36.7) | |

| > 10 | 34 (8.4) | 29 (7.1) | 63 (15.5) | |

| Vaccination history | ||||

| Unvaccinated | 193 (47.6) | 180 (44.3) | 373 (91.9) | |

| Vaccinated | 22 (5.4) | 11 (2.7) | 33 (8.1) | |

| Cell culture derived | 16 (3.9) | 10 (2.5) | 26 (6.4) | |

| Fuenzalida | 6 (1.5) | 1 (0.2) | 7 (1.7) | |

Among the butchers, 47.8% (194/406) had worked as a dog butcher for < 5 years and 36.7% (149) had been working for 5–10 years. Of the 406 participants, only 33 (8.1%) had been vaccinated against rabies (Table 1).

Regarding the risk of rabies virus exposure during the slaughtering process, 115/406 butchers (28.3%) were reported to be at risk of rabies exposure during the slaughtering process, which was from slaughtering of sick or dead dogs, getting bitten, scratched, or knife cut. The highest group at risk were butchers who had only been educated to a primary education level, accounting for 44.4% (28/63), followed by the group with 5–10 years of experience, accounting for 42.3% (63/149), and more than 10 years of experience, accounting for 36.5% (23/63) (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

The risk of rabies virus exposure related to seniority of butchers working at dog slaughterhouses in northern Vietnam (N = 406)

| Number of butchers (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period of employment (years) | Total | |||

| < 5 | 5–10 | > 10 | ||

| Hazardous risks* | 29/406 (7.1) | 63/406 (15.5) | 23/406 (5.7) | 115/406 (28.3) |

| Wound by knife/bone | 29 (14.9) | 63 (42.3) | 23 (36.5) | 115 (28.3) |

| Butchering sick dogs | 26 (13.4) | 24 (16.1) | 13 (20.6) | 63 (15.5) |

| Bitten by dogs | 15 (7.7) | 27 (18.1) | 12 (19.0) | 54 (13.3) |

| Butchering dead dogs | 15 (7.7) | 22 (14.8) | 10 (15.9) | 47 (11.6) |

| Total of people at risks | 29/194 (14.9) | 63/149 (42.3) | 23/63 (36.5) | 115/406 (28.3) |

Number of butchers who had at least one of the hazardous risks, including bitten by dogs, wound by knife, butchering sick dogs, and butchering dead dogs.

Table 4 shows that among 406 serum samples obtained from the study participants, 344 (84.7%) were seronegative, and 62 (15.3%) were seropositive for NTA. Thirty-five (8.6%) serum samples had sufficient protective antibody titers as per WHO recommendation (≥ 0.5 IU/mL) and 27 (6.7%) samples had NTA that were insufficient for protection. Additionally, 7.8% (29/373) of professional dog butchers were seropositive and had not been vaccinated against rabies. Among the unvaccinated group, eight butchers (2.1%) had NTA that was sufficient for protection (see Supplemental Table 1 for further information).

Table 4.

Titer of neutralizing antibodies of butchers working at dog slaughterhouses in northern Vietnam

| Number of butchers (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | Total | |||

| GMT | < 0.5 IU/mL | ≥ 0.5 IU/mL | |||

| Unvaccinated (N = 373) | 344/373 (92.2) | 0.25 | 21/373 (5.6) | 8/373 (2.1) | 29/373 (7.8) |

| Vaccinated (N = 33) | 0/33 (0.0) | – | 6/33 (18.2) | 27/33 (81.8) | 33/33 (100) |

| Cell culture derived vaccine | 0/26 (0.0) | 3.13 | 0/26 (0.0) | 26/26 (100) | 26/33 (78.8) |

| Fuenzalida vaccine | 0/7 (0.0) | 0.35 | 6/7 (85.7) | 1/7 (14.3) | 7/33 (21.2) |

| Total (N = 406) | 344/406 (84.7) | – | 27/406 (6.7) | 35/406 (8.6) | 62/406 (15.3) |

The geometric mean titer (GMT) was highest in the group that had been vaccinated with cell culture–derived vaccine (3.58 IU/mL). The GMT of the unvaccinated group was 0.25 IU/mL, which was lower than the 0.35 IU/mL seen in the group vaccinated with Fuenzalida vaccine (Table 4).

In the group that received the cell culture–derived vaccine, 100% (26/26) had NTA that was sufficient for protection, with antibody titers ranging from 0.66 IU/mL to 19.8 IU/mL. The shortest and longest duration between the receipt of the last vaccination and the start of the study was 3 months and 120 months, respectively. The NTA level of the subject who received three doses of cell culture–derived vaccine was 1.38 IU/mL even after 10 years, indicating adequate protective levels (see Supplemental Table 2 for further details).

In contrast, in the group vaccinated with Fuenzalida vaccine (suckling mouse–derived vaccine), only one person had sufficient protective antibodies, while six others had NTA that did not reach protective levels. However, 100% (7/7) of butchers vaccinated with Fuenzalida vaccine had NTA that lasted for more than 10 years (see Supplemental Table 3 for further details).

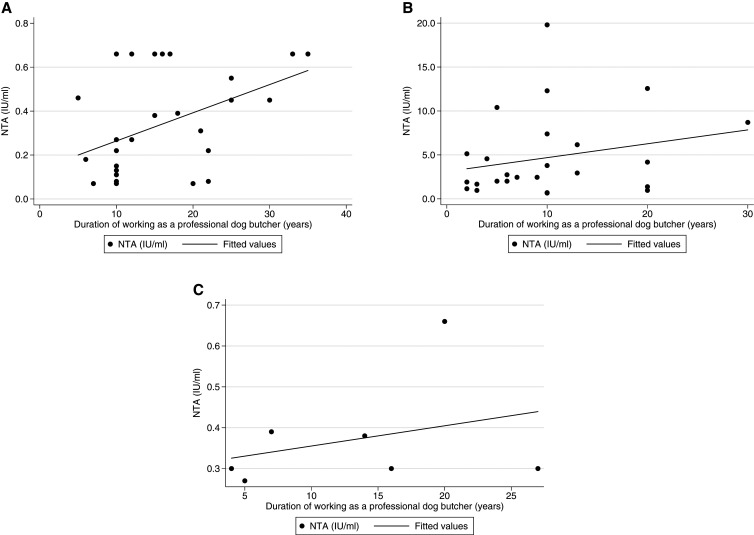

A moderate positive correlation (r = 0.64) between antibody titers and working time of professional dog butchers was observed in the butchers who had not been vaccinated against rabies. Meanwhile, there was a weak positive correlation between antibody titers and slaughtering time in the groups vaccinated with cell culture–derived (r = 0.23) and Fuenzalida (r = 0.31) vaccines (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Correlation between the neutralization antibody (NTA) titer and the duration of working as professional dog butcher (years) in butchers with different group of vaccination. (A) Unvaccinated group (r = 0.46); (B) Cell culture–derived vaccine group (r = 0.23) and (C) Suckling mouse–derived (Fuenzalida) vaccine group (r = 0.31).

Factors associated with the presence of rabies NTA among unvaccinated dog butchers were analyzed. The results showed that there was no significant association between the presence of rabies NTA and the number of dogs slaughtered on a daily basis, slaughtering sick or dead dogs, bites or knife cuts, and frequent use of gloves when butchering. However, having more than 5 years of experience as a dog butcher was positively associated with the presence of NTA (OR = 6.16, P = 0.001) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Risk factors associated with the presence of rabies neutralizing antibodies among unvaccinated professional dog butchers (N = 373)

| Hazardous risks | Number of butchers | OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NTA positive | NTA negative | ||||

| Number of dogs slaughtered daily | |||||

| < 5 dogs | 17 | 212 | 1 | – | 0.77 |

| ≥ 5 dogs | 12 | 132 | 0.88 | 0.38–2.04 | |

| Butchering sick dogs | |||||

| Yes | 5 | 48 | 1 | – | 0.39 |

| No | 24 | 296 | 1.61 | 0.54–4.76 | |

| Butchering dead dogs | |||||

| Yes | 7 | 39 | 1 | – | 0.14 |

| No | 22 | 305 | 2.16 | 0.75–6.21 | |

| Bitten by dogs | |||||

| Yes | 0 | 39 | – | – | – |

| No | 29 | 305 | |||

| Wound by knife | |||||

| Yes | 10 | 89 | 1 | – | 0.38 |

| No | 19 | 255 | 0.67 | 0.27–1.63 | |

| Period of employment | |||||

| < 5 years | 5 | 164 | 1 | – | 0.001 |

| ≥ 5 years | 24 | 180 | 6.16 | 2.20–17.25 | |

| Use of gloves | |||||

| Never | 23 | 317 | 1 | – | 0.75 |

| Regularly | 6 | 27 | 1.18 | 0.41–3.42 | |

Bold values indicate the significant difference between the two groups.

DISCUSSION

Rabies is the most recognized human health risk from dogs in Vietnam, with the highest case fatality ratio of any infectious disease. Despite concerns about the spread of rabies in Vietnam, the consumption of dog meat (legally or illegally acquired) is stable.5,9,10

One of the effective intervention methods to prevent human rabies is pre-exposure prophylaxis to people at high risk, including occupational groups such as veterinarians, dog trainers, rangers, laboratory workers, and professionals who are in direct contact with carnivores or other mammals associated with a rabies outbreak.1 However, in this study, there were 373/406 (91.9%) professional dog butchers not vaccinated against rabies (Table 1), which may be because of the fear of side effects of rabies vaccine, inability to afford vaccination, and incorrect knowledge of rabies prevention. Previously, Vietnam used a rabies vaccine derived from suckling-mouse brain (Fuenzalida vaccine). The side effects of this vaccine included local allergic reactions at the injection site as well as systemic allergies and neurological complications.3,11 As a result, the Fuenzalida vaccine was discontinued in 2007 and was replaced with a cell culture–derived vaccine. However, people are still concerned about using rabies vaccines, and the fear of side effects remains. In addition, the knowledge and practice of rabies prevention in health workers and veterinarians from northern provinces of Vietnam are low.12 Particularly, the inadequate and incorrect knowledge, poor practice of rabies control, and prevention of dog butchers as reported by Anh et al., with only 21/30 (70%) dog butchers acknowledging that rabies may be transmitted by butchering a rabid dog, and only 17/30 (56.7%) had correct knowledge on the control and prevention of rabies.13 This may be another reason influencing to the rate of rabies vaccination in this occupational group.

There were 115/406 (28.3%) butchers, of whom 42.3% (63/149) had 5–10 years of experience and 44.4% (28/63) had been educated to a primary education level and reported being at risk of exposure to rabies during the slaughtering process as a result of slaughtering sick or dead dogs, being bitten, or suffering cuts (Tables 2 and 3). Therefore, to further reduce the risk of rabies transmission to occupational dog butchers, slaughterhouses must be licensed and managed by the local government. Safety standards for slaughterhouse operations should be established. Comprehensive training and risk communication should be carried out to raise awareness of best practices for the prevention and control of rabies to professional dog butchers. Workers in slaughterhouses must be trained on safe butchering practices, including the appropriate use of personal protective equipment, with special focus on the group of butchers with primary education and under 10 years of experience.

Table 3.

The risk of rabies virus exposure related to educational background of butchers working at dog slaughterhouses in northern Vietnam (N = 406)

| Number of butchers (%) | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational background | |||||

| Primary | Secondary | High school | College/ University | ||

| Hazardous risks* | 28/406 (6.9) | 61/406 (15.0) | 21/406 (5.2) | 5/406 (1.2) | 115/406 (28.3) |

| Wound by knife/bone | 28 (44.4) | 61 (27.6) | 21 (21.0) | 5 (22.7) | 115 (28.3) |

| Butchering sick dogs | 17 (27.0) | 29 (13.1) | 16 (16.0) | 1 (4.5) | 63 (15.5) |

| Bitten by dogs | 11 (17.5) | 27 (12.2) | 14 (14.0) | 2 (9.1) | 54 (13.3) |

| Butchering dead dogs | 9 (14.3) | 27 (12.2) | 10 (10.0) | 1 (4.5) | 47 (11.6) |

| Total of people at risks | 28/63 (44.4) | 61/221 (27.6) | 21/100 (21.0) | 5/22 (22.7) | 115/406 (28.3) |

Number of butchers who had at least one of the hazardous risks, including bitten by dogs, wound by knife, butchering sick dogs, and butchering dead dogs.

Most butchers (84.7%) tested negative for NTA against rabies. Only 62/406 (15.3%) were positive for rabies NTA; among these, 8.6% showed protective antibody titers (≥ 0.5 IU/mL) (Table 4). In Vietnam, rabies is prevalent nationwide, with approximately 100 human rabies cases recorded annually. Dog meat consumption is frequent in many families across different regions of the country.3–5,9,10 However, dogs are supplied to most slaughterhouses without veterinary control, and these animals may be from within the country or may be illegally imported from abroad (Laos, Thailand, and China).3–5,9,10 In addition, in the period of 2006–2009, 2% of rabies-infected dogs were found in dog slaughterhouses in Hanoi, Vietnam.6 Every year, Vietnam consumes approximately five million dogs5,9 and given the rate of rabies infection is 2%, there may be thousands of rabid dogs being put into slaughterhouses. With only 8.6% of professional dog butchers meeting the WHO recommendation for NTA levels from the findings of this study, dog butchers are definitely an occupational group at high risk of rabies in Vietnam. In fact, a number of human rabies cases have been recorded after the butchering of a dog.3,4,14 Therefore, as part of a strategy to control human rabies, the government should take measures to strictly manage the transportation and consumption of dogs, ensure veterinary control at slaughtering houses and markets, implement risk communication interventions to improve people’s understanding of rabies prevention measures, and provide vaccination against rabies for professional dog butchers as an occupational group. There is also a need to conduct further research to study anti-rabies antibodies of other at-risk occupational groups such as veterinarians and pet owners.

Concerning the GMT of antibodies against rabies virus in the study group, the GMT of the group vaccinated with the cell culture–derived rabies vaccine was higher (3.58 IU/mL) than that of the Fuenzalida rabies vaccination group (0.35 IU/mL). In this study, 26/26 (100%) of the subjects vaccinated with the cell culture–derived rabies vaccine had an NTA titer at protection level (> 0.5 IU/mL) (Table 4). The longest persistence duration of NTA was 10 years, with an antibody titer of 1.38 IU/mL. The minimum and maximum number of injections were two and five shots, respectively (Supplemental Table 2). The titers and duration of NTA at the protection level in this study were higher and longer than those reported in a study from India among 19 cases vaccinated with purified Vero cell culture vaccine after exposure to suspected rabid foxes. In this study, 17/19 victims survived and were monitored for antibody levels. The results showed that their antibody titers dropped to < 0.5 IU/mL in five and four patients on days 870 and 1020 after the first vaccination, respectively.15 The existence of NTA to rabies virus at protection levels in our study subjects was 100% and lasted longer (up to 10 years), possibly as a result of the butchers’ continuous exposure to rabies virus antigens in the course of their jobs, which may be considered equivalent to receiving “booster shots.”

Similarly, for the Fuenzalida vaccination group, the antibody titer and persistence duration of NTA were also higher and longer than those reported in other studies. In our study, 7/7 (100%) dog butchers vaccinated with the Fuenzalida vaccine had NTA. One of the seven had protective antibody levels that existed for at least 9 years after the Ministry of Health of Vietnam officially stopped using Fuenzalida rabies vaccines nationwide on September 24, 2007.16 A study involving 57 subjects showed that the duration of residual rabies antibody when vaccinated with the Fuenzalida vaccine was relatively short and the antibody titer was not high when using three doses of the Fuenzalida rabies vaccine for pre-exposure prophylaxis. As a result, 7 (12%), 12 (21%), and 38 (67%) subjects did not have adequate immune responses at 3, 6, and 18 months after the first vaccination, respectively.17 The long-term persistence and higher titer of NTA against rabies virus in the vaccinated group in our study in comparison with some other studies may be as a result of their occupation that regularly exposes them to rabies virus antigens during slaughtering, which causes immune responses similar to a series of boosters with rabies virus antigens.

In this study, 29/373 (7.8%) dog butchers who had never been vaccinated with rabies vaccine, had NTA against rabies virus with a low titer (GMT= 0.25 IU/mL. This finding is similar to that of Garba et al.,18 who examined groups at risk of rabies, including dog meat consumers, butchers, owners, hunters, and veterinarians. They found that 14.8–25% of unvaccinated professional groups had NTA against rabies with titers ranging from 0.05 to 0.65 IU/mL.18 Our study results reinforce the scientific evidence of previous reports on natural immune responses with different variants of strains from dogs18 and bats.19 It may be hypothesized that as a result of constant exposure to small doses of virus antigens, an immune response occurs. However, it is unknown whether the natural antibody in this group is protective. Hence, further research on the immune response mechanism of natural rabies virus infection should be performed to understand the presence of NTA in unvaccinated risk groups. Additionally, the results of this study support the need to protect dog butchers through vaccination or revaccination and to educate this occupational group regarding best practices for rabies control and prevention.

According to the analysis results of the factors associated with the presence of rabies NTA in unvaccinated butchers, there was no significant association between the presence of rabies NTA and the number of dogs slaughtered on a daily basis, slaughtering sick or dead dogs, bites or knife cuts, and frequent use of gloves when butchering. However, having more than 5 years of experience as a dog butcher was positively associated with the presence of NTA (OR = 6.16, P = 0.001) (Table 5). It remained unidentified in this study why unvaccinated professional dog butchers with more than 5 years of experience had 6.16 times higher in NTA to rabies than those with less than 5 years of experience did. This is a limitation of the study, which resulted from our lack of access to information such as frequency of bites and knife cuts, the number and frequency of slaughtered sick/dead dogs, and dog butchers’ raw and cooked dog meat consumption during their career. This issue will be under consideration for our future research, so as to best contribute to the rabies prevention programs in Vietnam, especially with regard to the professional butcher group.

In conclusion, professional dog butchers in northern Vietnam are at a high risk of rabies virus infection. The presence of natural rabies NTA in unvaccinated butchers and the persistence and titer of NTA in the vaccinated group were higher and lasted longer than those of other previously reported professionals, which is possibly because of multiple exposures to rabies virus antigens during dog slaughtering. It is suggested that in rabies-endemic countries with customary dog meat consumption, rabies control and prevention activities should particularly focus on dog trading and slaughtering safety.

Supplemental tables

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the participants who kindly took the time to participate in the study. We also thank Dr. Vu Thanh Giang from Hanoi Center for Disease Control and our colleagues from district health centers of Hoai Duc, Ha Dong, Hoang Mai, Son Tay, Nam Tu Liem, and Quoc Oai, Hanoi City, for organizing the interviews.

Note: Supplemental tables appear at www.ajtmh.org

References

- 1. WHO , 2018. WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies: Third Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272364/9789241210218-eng.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 2. Child JE, Reeal LA, 2007. Epidemiology. Jackson AC, Wunner WH, eds. Rabies 2nd edition. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 143–144. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nguyen TH , 2013. Rabies in Vietnam: Opportunities and Challenges. Symposium of Multisetoral Conference on Rabies Control and Prevention. Hanoi, Vietnam: National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nguyen TTH, Hoang VT, Nguyen TH, 2013. Epidemiology of rabies in Vietnam, 2009–2011. J Prev Med (Wilmington) 7: 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thu P , 2014. 5 Million Dogs, 3 Billion Liters of Beer and 500,000 Tran Seals. Available at: https://baodatviet.vn/chinh-tri-xa-hoi/5-trieu-con-cho-3-ty-lit-bia-va-500000-an-den-tran-3001422/. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 6. Nguyen AK. et al. , 2011. Molecular epidemiology of rabies virus in Vietnam (2006–2009). Jpn J Infect Dis 64: 391–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jackson AC, 2007. Human disease. Jackson AC and Wunner WH, eds. Rabies 2nd edition. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 321–322. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith JS, Yager PA, Baer GM, 1996. A rapid fluorescent focus inhibition test (RFFIT) for determining rabies virus neutralizing antibody. Meslin FX, Kaplan MM, Koprowski H, eds. Laboratory Techniques in Rabies 4th edition. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hodal K , 2013. How Eating Dog Became Big Business in Vietnam. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/sep/27/eating-dog-vietnam-thailand-kate-hodal. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 10. Four Paws , 2020. Report Advises on How to End the Dog and Cat Meat Trade in Southeast Asia. Available at: https://www.eurogroupforanimals.org/news/report-advises-how-end-dog-and-cat-meat-trade-southeast-asia. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 11. Bonito RF, de Oliveira NM, de Andrade Nishioka S, 2004. Adverse reactions associated with a Fuenzalida-Palacios rabies vaccine: a quasi-experimental study. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 37: 7–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nguyen KA, Nguyen HT, Pham TN, Van KD, Hoang TV, Olowokure B, 2016. Knowledge of rabies prevention in Vietnamese public health and animal health workers. Zoonoses Public Health 63: 522–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Anh VH, Huan DD, Cam NN, Kieu Anh NT, 2015. Knowledge, practice and factors related to rabies control and prevention of professional dog butchers in Sonloc ward, Sontay town, Hanoi City, 2012. J Prevent Med 25-3: 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wertheim HFL. et al. , 2009. Furious rabies after an atypical exposure. PLoS Med 6: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matha IS, Salunke SR, 2005. Immunogenicity of purified vero cell rabies vaccine used in the treatment of fox-bite victims in India. Clin Infect Dis 40: 611–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Anh L, 2017. Stop Use of Fuenzalida Rabies Vaccine. Available at: https://dantri.com.vn/suc-khoe/tu-249-ngung-su-dung-vac-xin-dai-fuenzalida-1189929861.htm. Accessed March 23, 2020.

- 17. Preto AA, Gomes EM, Fernandes MJ, Hennig NA, Germano PML, 2000. Assessment of the plan for pre-exposition vaccination with Fuenzalida-Palacios anti-rabies vaccine. Braz Arch Biol Technol 43: 253–257. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Garba A, Umoh J, Kazeem H, Dzikwi A, Ahmed M, Ogun A, Okewole P, Habib M, Zaharaddeen A, 2015. Rabies virus neutralizing antibodies in unvaccinated rabies occupational risk groups in Niger State, Nigeria. Int J Trop Dis Health 6: 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gilbert AT, Petersen BW, Recuenco S, Niezgoda M, Gómez J, Laguna-Torres VA, Rupprecht C, 2012. Evidence of rabies virus exposure among humans in the Peruvian Amazon. Am J Trop Med Hyg 87: 206–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.