Overview

In 2002, an estimated 41,000 new cases of rectal cancer will occur in the United States (22,600 cases in men and 18,400 cases in women). During the same year, it is estimated that 8,500 people will die from rectal cancer.1 Although colorectal cancer is ranked as the third most frequently diagnosed cancer in men and women, mortality from rectal cancer has decreased over the past 30 years. This decrease may be due to both earlier diagnosis through screening and better treatment modalities.

The recommendations in these clinical practice guidelines are classified as category 2A except where noted, meaning that there is uniform NCCN consensus, based on lower-level evidence, including clinical experience, that the recommendation is appropriate. The panel unanimously endorses patient participation in a clinical trial over standard or accepted therapy. This is especially true for cases of advanced disease and for patients with locally aggressive colorectal cancer who are receiving combined modality treatment.

The clinical practice guidelines for managing rectal carcinoma overlap considerably with the NCCN Colon Cancer Guidelines. First-degree relatives of patients with newly diagnosed adenomous2 or invasive carcinoma3 are at increased risk for colorectal cancer. Therefore, rectal cancer patients, especially those who are 50 years old or younger, should be counseled regarding their family history as outlined in the NCCN Colorectal Screening Guidelines (in this issue).

Staging

The NCCN Rectal Cancer Guidelines adhere to the current TNM staging system (Table 1 ).4,5In this version of the staging system, smooth metastatic nodules in the pericolic or perirectal fat are considered lymph node metastasis and should be counted in the N staging. Irregularly contoured metastatic nodules in the peritumoral fat are considered vascular invasion. Stage II is now subdivided into IIa (if the primary tumor is T3) and IIB (for T4 lesions). Stage III is subdivided into IIIA (T1–2, N1, M0), IIIB (T3–4, N1, M0), and IIIC (Any T, N2, M0). In addition, the current staging suggests that the surgeon mark the area of the specimen with the deepest tumor penetration so that the pathologist can directly evaluate the radial margin. The surgeon is encouraged to score the completeness of the resection as 1) R0 for complete tumor resection with all margins negative, 2) R1 for incomplete tumor resection with microscopic involvement of a margin, and 3) R2 for incomplete tumor resection with gross residual tumor not resected.

Table 1.

American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM Staging System for Colorectal Cancer*

| Primary Tumor (T) | |||||

|

| |||||

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | ||||

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | ||||

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ: intraepithelial or invasion of lamina propria† | ||||

| T1 | Tumor invades submucosa | ||||

| T2 | Tumor invades muscularis propria | ||||

| T3 | Tumor invades through the muscularis propria into the subserosa or into nonperitonealized pericolic or perirectal tissues | ||||

| T4 | Tumor directly invades other organs or structures and/or perforates visceral peritoneum‡ | ||||

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) § | |||||

|

| |||||

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | ||||

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | ||||

| N1 | Metastasis in one to three regional lymph nodes | ||||

| N2 | Metastasis in four or more regional lymph nodes | ||||

| Distant Metastasis (M) | |||||

|

| |||||

| MX | Distant metastasis cannot be assessed | ||||

| M0 | No distant metastasis | ||||

| M1 | Distant metastasis | ||||

| Stage Grouping | |||||

|

| |||||

| Stage | T | N | M | Dukes¶ | MAC¶ |

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 | – | – |

| 1 | T1 | N0 | M0 | A | A |

| T2 | N0 | M0 | A | B1 | |

| IIA | T3 | N0 | M0 | B | B2 |

| IIB | T4 | N0 | M0 | B | B3 |

| IIIA | T1-T2 | N1 | M0 | C | C1 |

| IIIB | T3-T4 | N1 | M0 | C | C2/C3 |

| IIIC | Any T | N2 | M0 | C | C1/C2/C3 |

| IV | Any T | Any N | M1 | – | D |

| Histologic Grade (G) | |||||

|

| |||||

| GX | Grade cannot be assessed | ||||

| G1 | Well differentiated | ||||

| G2 | Moderately differentiated | ||||

| G3 | Poorly differentiated | ||||

| G4 | Undifferentiated | ||||

This includes cancer cells confined within the glandular basement membrane (intraepithelial) or lamina propria (intramucosal) with no extension through the muscularis mucosae into the submucosa.

Direct invasion in T4 includes invasion of other segments of the colorectum by way of the serosa, for example, invasion of the sigmoid colon by a carcinoma of the cecum. Tumor that is adherent to other organs or structures macroscopically is classified T4; however, if no tumor is present in the adhesion microscopically the classification should be pT3. The V and L substaging should be used to identify the presence or absence of vascular or lymphatic invasion.

A tumor nodule in the pericolorectal adipose tissue of a primary carcinoma without histologic evidence of residual lymph node in the nodule is classified in the pN category as a regional lymph node metastasis if the nodule has the form and smooth contour of a lymph node. If the nodule has an irregular contour, it should be classified in the T category and also coded as V1 (microscopic venous invasion) or as V2 (if it was grossly evident) because there is a strong likelihood that it represents venous invasion.

Dukes B is a composite of better (T3 N0 M0) and worse (T4 N0 M0) prognostic groups, as is Dukes C (Any TN1 M0 and Any T N2 M0). MAC is the modified Astler-Coller classification.

Note: The y prefix is to be used for those cancers that are classified after pretreatment, whereas the r prefix is to be used for those cancers that have recurred.

Used with the permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original source for this material is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th Edition (2002), published by Springer-Verlag New York (www.springer-ny.com).

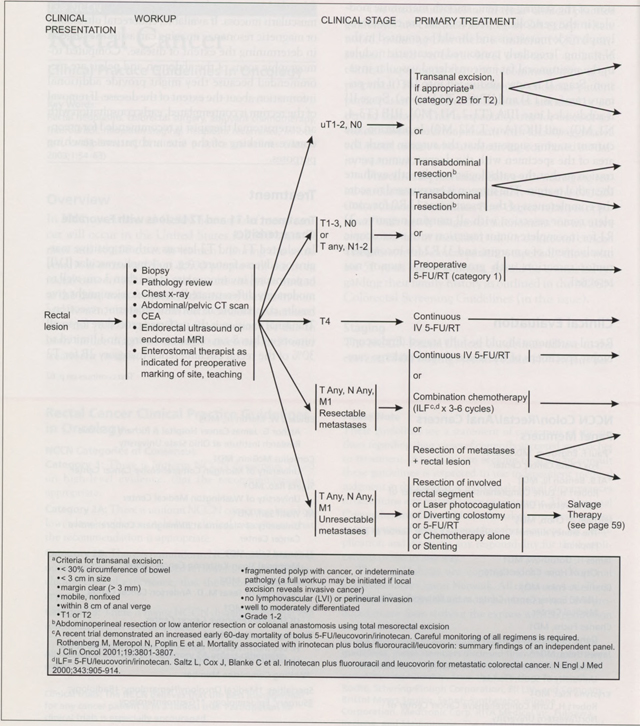

Clinical Evaluation

Rectal carcinoma should be fully staged. Endoscopic biopsy specimens of the lesion should undergo careful pathology review for evidence of invasion into the muscularis mucosa. If available, endorectal ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging can assist the surgeon in determining the extent of disease.6 Computed tomographic scans of the abdomen and pelvis are recommended because they might provide additional information about the extent of the disease. If removal of the rectum is contemplated, early consultation with an enterostomal therapist is recommended for preoperative marking of the site and patient teaching purposes.

Treatment

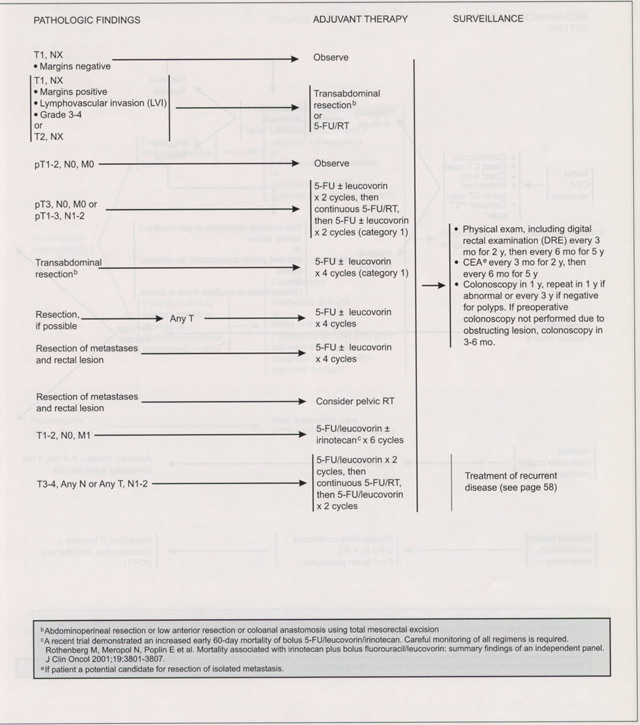

Treatment of T1 and T2 Lesions with Favorable Characteristics

In selected T1 and T2 lesions without positive margins or adverse features (eg, no lymphovascular [LVI] or perineural invasion; a size of less than 3 cm; well to moderately differentiated), local excision might give results comparable to anterior-posterior resection.’ Transanal excision is the preferred procedure for small tumors within 8 cm of the anal verge and limited to 30% of the rectal circumference (category 2B for T2 tumors). Transabdominal resection should be used when lesions are not suitable for transanal surgery. If postsurgical pathology review after local excision reveals grade 3 to 4, T1 lesions with positive margins, and LVI or T2 lesions, reresection, including radical surgery if necessary, should be performed.

Treatment of Invasive Carcinoma

For patients with T1 to T2 lesions not amenable to local excision, a radical resection is required. For lesions in the mid to upper rectum, a low anterior resection is the treatment of choice. For low rectal lesions, abdominoperineal resection or coloanal anastomosis is required. To reduce the risk of local recurrence, patients should undergo optimal pelvic dissection with sharp mesorectal excision, including mesentery distal to the tumor as an intact unit.8 No adjuvant therapy is indicated for patients with T1 or T2 lesions. Patients with lymph node-negative T3 or T4 lesions or any lymph node-positive cancer should receive adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy (category 1), either preoperatively or postoperatively. In Intergroup Trial U114, all patients received six cycles of postoperative chemotherapy plus concurrent radiation therapy during cycles 3 and 4. After a median follow-up of 4 years, neither the rate of local control nor survival differed among three different combinations of modulated 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) chemotherapy.9 In addition, the Mayo/NCCTG 86–47-51 trial showed that single-agent, continuous-infusion 5-FU was more effective than bolus 5-FU. As a result, continuous infusion 5-FU plus radiotherapy or bolus 5-FU plus radiotherapy is an acceptable chemoradiation regimen.10 Patients with T3 or T4 rectal carcinomas should be considered for preoperative combined-modality therapy. A major goal of preoperative therapy is to decrease the volume of the primary tumor and thus enhance sphincter preservation.11

For patients in whom radical resection is not indicated for medical reasons, adjuvant chemoradiotherapy is recommended after local excision to reduce local recurrence rates.12 Patients with stage IV lesions may be candidates for palliative resection fulguration or radiotherapy followed by systemic therapy.

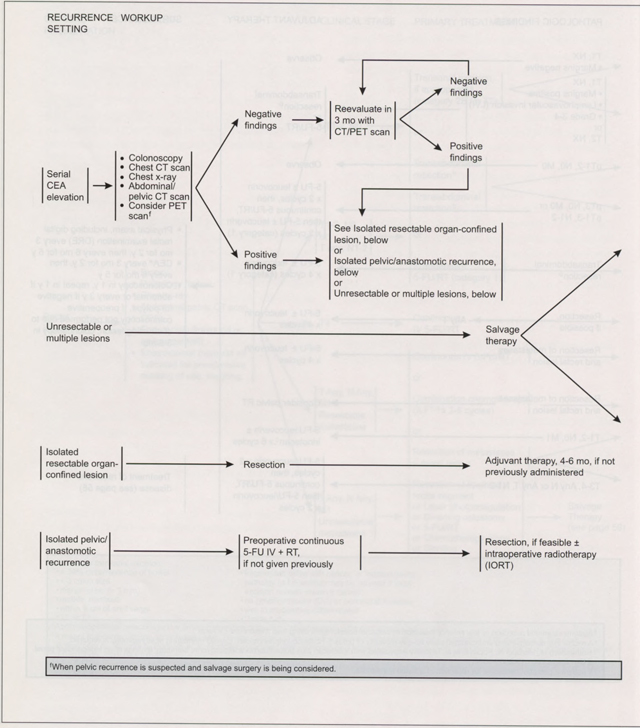

Surveillance and Management of Recurrence

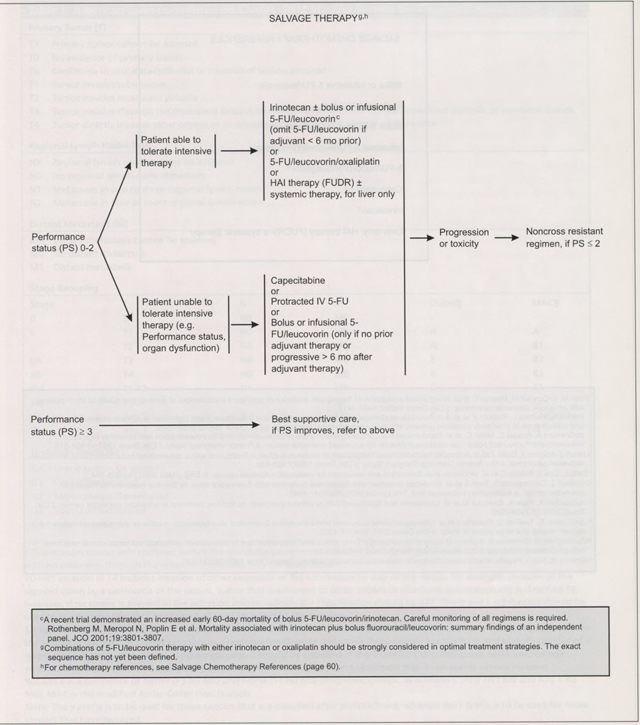

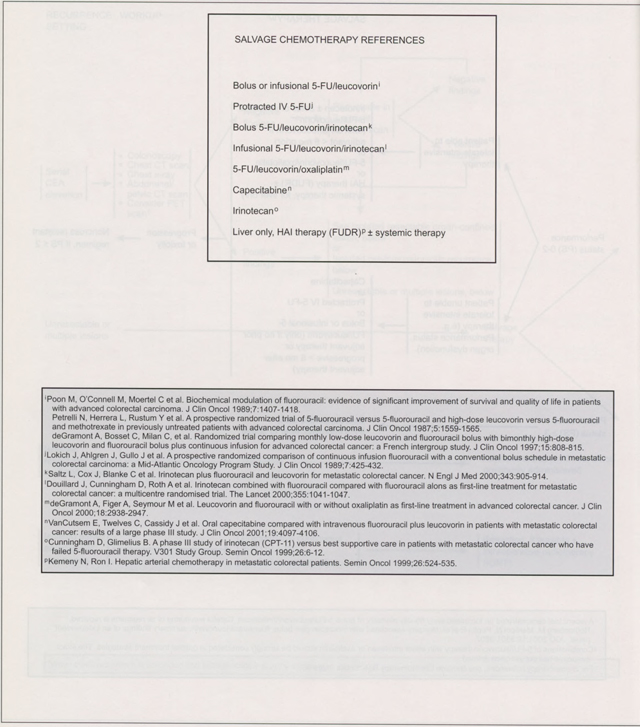

The approach to monitoring and surveillance of patients with rectal carcinoma is essentially the same as for colon cancer. Patients with suspected recurrence caused by rising carcinoembryonic antigen or suspicious computed tomographic scan should have a positron emission tomography scan, especially if salvage surgery is under consideration. The salvage chemotherapy treatments for metastatic or recurrent rectal cancer are similar to the recommendations for colon cancer. Patients with good performance status and an ability to tolerate intensive therapy should be considered for irinotecan alone or bolus or infusional 5-FU/leucovorin/irinotecan,13 or 5-FU/leucovorin/oxaliplatin.14 Patients who are unable to tolerate intensive therapy should be offered capecitabine, protracted intravenous 5-FU, or bolus or infusional 5-FU leucovorin. Because weekly bolus 5-FU/leucovorin/irinotecan may cause severe gastrointestinal toxicity, patients on this regimen should be carefully monitored during the first 60 days of therapy.

Summary

The NCCN Rectal Cancer Guidelines panel believes that a multidisciplinary approach is necessary for treating patients with colorectal cancer. Patients with T1 or T2 lesions that are node negative by endorectal ultrasound and who meet carefully defined criteria can be managed with a transanal excision. Abdominal peritoneal resection or low anterior resection with total mesorectal excision is appropriate for all other rectal lesions. Either preoperative chemoradiation or postoperative chemoradiotherapy is standard for patients with suspected or proven serosal invasion (pT3) or regional node involvement. Patients with recurrent localized disease should be considered for resection with or without radiotherapy. Chemotherapy regimens using irinotecan or oxaliplatin should be considered for patients with distant metastasis. The panel endorses the concept that treating patients in a clinical trial has priority over standard or accepted therapy.

NCCN Categories of Consensus

Category 1:

There is uniform NCCN consensus, based on high-level evidence, that the recommendation is appropriate.

Category 2A:

There is uniform NCCN consensus, based on lower-level evidence including clinical experience, that the recommendation is appropriate.

Category 2B:

There is nonuniform NCCN consensus (but no major disagreement), based on lower-level evidence including clinical experience, that the recommendation is appropriate.

Category 3:

There is major NCCN disagreement that the recommendation is appropriate.

All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise noted.

Clinical trials: The NCCN believes that the best management for any cancer patient is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

Please Note

These guidelines are a statement of consensus of the authors regarding their views of currently accepted approaches to treatment. Any clinician seeking to apply or consult these guidelines is expected to use independent medical judgment in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine any patient’s care or treatment. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network makes no representations or warranties of any kind regarding their content, use, or application and disclaims any responsibility for their applications or use in any way.

These guidelines are copyrighted by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. All rights reserved. These guidelines and the illustrations herein may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of the NCCN © 2003.

At the beginning of each panel meeting to develop NCCN guidelines, panel members disclosed financial support they have received. In the form of research support or advisory committee membership, from the following: Pharmacia, Roche, Schering-Plough Corporation, Eli Lilly and Company, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Digene Corporation, Medtronic Corp, RITA Medical Inc, Fujisawa, Imclone, and Medimmune. The panel did not regard any of these potential conflicts of Interest as sufficient reason to disallow participation in panel deliberations by any member.

Contributor Information

Paul F. Engstrom, Fox Chase Cancer Center.

AI B. Benson, III, Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University.

Michael A. Choti, The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins.

James H. Doroshow, City of Hope Cancer Center.

Charles A. Enke, UNMC Eppley Cancer Center at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Charles Fuchs, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

James Helm, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute at the University of South Florida.

Krystyna Kiel, Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University.

Kirk Ludwig, Duke Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Edward W. Martin, Jr., Arthur G. James Cancer Hospital & Richard J. Solove Research Institute at Ohio State University.

Cornelius McGinn, University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Sujata Rao, University of Washington Medical Center.

M. Wasif Saif, University of Alabama at Birmingham Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Leonard Saltz, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

John M. Skibber, University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center.

Alan P. Venook, UCSF Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Timothy J. Yeatman, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute at the University of South Florida.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Thomas A, Murray T et al. Cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 2002;52:23–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahsan H, Neugut AI, Garbowski GC et al. Family history of colorectal adenomatous polyps and increased risk for colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med 1998;128:900–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonelli L, Martines H, Conio M et al. Family history of colorectal cancer as a risk factor for benign and malignant tumours of the large bowel: A case-control study. Int J Cancer 1988;41:513–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greene FL, Stewart AK, Norton HJ. A new TNM staging strategy for node-positive (stage III) colon cancer. Am Surg 2002;236:416–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tempero M, Brand R, Haldeman K et al. New imaging techniques in colorectal cancer. Semin Oncol 1995;22: 448–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Willett CG, Compton CC, Shelleto PC et al. Selection factors for local excision or abdominoperineal resection of early stage rectal cancer. Cancer 1994;73:2716–2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guillem JG, Cohen AM. Current issues in colorectal cancer surgery. Semin Oncol 1999;26:505–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tepper JE, O’Connell MJ, Petroni GR et al. Adjuvant post-operative fluorouracil-modulated chemotherapy combined with pelvic radiation therapy for rectal cancer: Initial results of intergroup U114. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:2030–2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minsky BD. Adjuvant therapy of rectal cancer. Semin Oncol 1999;26:540–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagman R, Minsky BD, Cohen AM et al. Sphincter preservation with pre-operative radiation therapy (RT) and coloanal anastomoses: Long term follow up. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1998;42:51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minsky BD, Cohen AM, Enker WE et al. Sphincter preservation in rectal cancer by local excision and post-operative radiation therapy. Cancer 1991;67:908–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saltz LB, Locker PK, Piroha N et al. Weekly irinotecan (CPT-11) leucovorin (LV) and fluorouracil (FU) is superior to daily ×5 LV/ FU in patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer [abstract]. Proc ASCO 1999; 18:233a. [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Gramont A, Figer A, Seymour M et al. Leucovorin and fluorouracil with or without oxaliplatin as first-line treatment in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:2938–2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]