Summary

Proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) represent a new direction in small-molecule therapeutics whereby a heterobifunctional linker to a protein of interest (POI) induces its ubiquitination-based proteolysis by recruiting an E3 ligase. We show here that charge reduction, native mass spectrometry, and gas-phase activation methods combine for an in-depth analysis of a PROTAC-linked ternary complex. Electron-capture dissociation (ECD) of the intact POI-PROTAC-VCB complex (a trimeric subunit of an E3 ubiquitin ligase) promotes POI dissociation. Collision-induced dissociation (CID) causes elimination of the non-peripheral PROTAC, producing an intact VCB-POI complex not seen in solution but consistent with PROTAC-induced protein-protein interactions. Additionally, we used ion mobility spectrometry (IMS) and collisional activation to identify the source of this unexpected dissociation. Together, the evidence shows that this integrated approach can be used to screen for ternary complex formation and PROTAC-protein contacts and may report on PROTAC-induced protein-protein interactions, a characteristic correlated with PROTAC selectivity and efficacy.

Keywords: PROTACs (proteolysis targeting chimeras), ternary complex, MZ1, native mass spectrometry, ECD (electron capture dissociation), CID (collision-induced dissociation), CIU (collision-induced unfolding), IMS (ion mobility spectrometry), charge reducing agent, E3 ligase, Bromodomain-containing protein 4, von Hippel-Lindau protein (VHL)

TOC Blurb

Song et al. demonstrate the utility of native mass spectrometry, ion mobility spectrometry, and multiple activation methods to characterize PROTAC-induced complex topologies and conformation-specific protein-protein interactions.

Introduction

Proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) are heterobifunctional small molecules that consist of two protein-binding ligands connected by a linker. Each ligand binds either an E3 ubiquitin ligase or the protein of interest (POI) to promote ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of the POI (Pettersson and Crews, 2019; Roy et al., 2019). The use of these small molecules represents a new direction in protein therapeutics whereby disease-related proteins can be directly targeted for degradation (Farnaby et al., 2019). The development of PROTACs as potential therapeutic agents, however, presents unique challenges (Edmondson et al., 2019). One is to understand the positive protein-protein interactions between the E3 ligase and the POI that are reportedly more indicative of PROTAC selectivity and efficacy than the affinity of bonding the PROTAC (Bondeson et al., 2018). Thus, a structure-guided approach that identifies positive protein-protein interactions is critical to screen for effective PROTACs, and we show here an alternative approach to achieve that goal.

Bromodomain-containing protein 4 (BRD4) is a common target for PROTAC-induced degradation; BRD4 plays an important role in transcriptional regulation, epigenetics, and cancer, and the inhibition of BRD4 causes antiproliferative activities in several cancer cells (Bondeson et al., 2015; Zengerle et al., 2015; Zorba et al., 2018). As of 2020, at least twelve BRD4 targeting PROTACs have been reported (Li and Song, 2020). The PROTAC MZ1 forms a noncovalent ternary complex linking BRD4 and von Hippel-Lindau protein (VHL), the substrate recognition subunit of the VCBCR (or CRL2VHL) E3 ubiquitin ligase (Collins et al., 2017). The VCBCR complex consists of VHL, elongin B, elongin C (together the VCB complex), cullin-2, and Rbx1. The first crystal structure of the BRD4BD2-MZ1-VCB complex became available in 2017, (Gadd et al., 2017) supporting the mechanism of action (Figure 1) (Ottis and Crews, 2017). In addition to showing the expected contacts between MZ1 and the two proteins, the crystal structure revealed contacts between the linked BRD4 and VHL. Mutation of key MZ1-induced BRD4 contacts with VHL largely attenuates cooperative formation of the ternary complex despite exhibiting no effect on the MZ1 affinity for both VHL and BRD4. Other PROTACs such as AT1 have higher selectivity with BRD4BD2 but poor efficacy because their binding is associated with weaker protein-protein interactions (Beveridge et al., 2020). Thus, the route to understanding the complex may go through the protein-protein interactions.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the PROTAC mechanism of action for MZ1, linking the VCBCR E3 ubiquitin ligase substrate-recognition subunit VHL (large red triangle) and the target protein hBRD4 (large blue circle); the PROTAC ligands specific to VHL and hBRD4 are shown as a smaller red triangle and blue circle, respectively. The E3 ubiquitin ligase is a hetero pentamer that also includes elongin B (green rectangle), elongin C (yellow circle), Cullin-2 (gray shape), and Rbx1 (orange tear drop). Upon PROTAC-induced binding of hBRD4 to VHL, the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (orange pentagon) then ubiquitinates hBRD4, which the proteasome can now recognize and degrade.

Our integrated approach utilizes native mass spectrometry (MS), several gas-phase fragmentation approaches, and ion mobility to characterize the MZ1-induced noncovalent ternary complex. Native MS has emerged as a powerful tool for the characterization of intact protein complexes (Boeri Erba et al., 2020; Gault et al., 2020; Heck, 2008; Xie et al., 2006); more specifically, native MS can quickly and with minimal sample consumption (picomoles) characterize binding stoichiometry, topology, and dynamics of protein complexes existing in heterogenous protein mixtures (Pukala et al., 2009). Native MS accomplishes the direct ionization of biological analytes from aqueous solution and their transfer to the gas phase by using electrospray ionization (ESI). This transfer not only preserves, at least temporarily, intact protein complexes but also maintains intra- and intermolecular interactions of a “native-like” protein or protein complex (Breuker and McLafferty, 2008). The use of charge-reducing agents (such as triethylammonium acetate (TEAA) and ethylenediamine diacetate (EDDA)) reduces the coulombic repulsion that often induces gas-phase unfolding and helps maintain the native or near-native gas-phase structures (Catalina et al., 2005; Hogan et al., 2009; Lemaire et al., 2001; Mehmood et al., 2014; Pacholarz and Barran, 2016).

This ability to introduce “native-like” structures to a mass spectrometer enables utilization of methodologies to provide information on protein assemblies. Collision-induced dissociation (CID) (Laganowsky et al., 2013), electron-capture dissociation (ECD) (Lermyte et al., 2018; Zhurov et al., 2013), infrared multiphoton dissociation (IRMPD) (Brodbelt, 2014), surface-induced dissociation (SID)(Yan et al., 2017), and ultraviolet photodissociation (UVPD) (Brodbelt et al., 2020) are possibilities. Each can preserve some noncovalent interactions and together provide complementary information. We used both CID and ECD in this study.

CID is most widely applied, wherein ions are accelerated into a buffer gas, converting some kinetic energy into vibrational internal energy and causing the ions to fragment via low-energy dissociation pathways. The dominant CID pathway of a protein complex is ejection of a peripheral subunit with a disproportionally high charge state via subunit unfolding (i.e., asymmetric charge partitioning (ACP) (Jurchen and Williams, 2003; Konermann, 2009; McAllister et al., 2015; Popa et al., 2016); however, alternative dissociation pathways have been reported for charge reduced protein complexes via ejection of nonperipheral subunits (Wang et al., 2020) and lower charged, relatively folded subunits (Pagel et al., 2010). Alternatively, ECD occurs via fast activation achieved by interaction of a multiply charged precursor ion with low-energy electrons to induce charge reduction, fragmentation at peptide bonds, and subunit disassociation (Cui et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2011). CID and ECD yield complementary information on protein complex topology, and their integration provides insight into noncovalent protein assemblies relevant to interactomics, structural biology, subunit identification, post-translational modification detection, among others (Allison and Bechara, 2019; Boeri Erba et al., 2020). Our hypothesis is that use of these activation methods can bring new insights to PROTACS and their protein binding.

Another approach commonly coupled with native MS is ion mobility spectrometry (IMS)(Beveridge et al., 2019; Eschweiler et al., 2017; Hall et al., 2012), which allows gas-phase separation based on three-dimensional shape, size, and charge (i.e., their ion-neutral collision cross-section (CCS)). IMS can sensitively report perturbations of protein complex secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structure in both solution and the gas-phase, and IMS-MS is becoming widely applied to separate proteins and protein complexes ions from mixtures and to identify their conformational heterogeneity. In the gas-phase, pre-IMS CID (termed collision-induced unfolding or CIU) probes gas-phase unfolding pathways of protein complexes. Alternatively, post-IMS CID characterizes ions separated according to their CCS, commonly utilized for additional separation in bottom-up analyses (Wells and McLuckey, 2005).

In this article, we describe the use of ECD and CID to identify two distinct subunit dissociation pathways pointing to two general topology classes for PROTAC complexes. These classes are further characterized by IMS to be a heterogeneous distribution of ternary complex conformations whose distinctive dissociation pathways are assigned.

Results and Discussion

The PROTAC ternary complex can be introduced to the gas phase by native MS

Initially, we established that the intact VCB-MZ1-hBRD4 ternary complex can be observed using native MS, consistent with previous reports where it was used to screen PROTACs (Beveridge et al., 2020). Native MS was also used in an hydrogen/deuterium exchange study to verify the preparation of the ternary complex (Zorba et al., 2018). Using native MS, we observed the intact MZ1-VCB-hBRD4 ternary complex with charge states of 16+, 15+, and 14+ (Figure 2A). These charge states are lower than the Rayleigh charge limit of water droplets for analytes of this size, and the average number of charges on each protein is proportional to the square of the gas-phase protein diameter (Hogan et al., 2009; Konermann, 2009; McAllister et al., 2015). In the absence of MZ1 in the solution submitted to native MS, we did not see a [VCB-hBRD4] binary complex (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Native MS of VCB and hBRD4 (A) with MZ1 and (B) without MZ1; spectra acquired with a Thermo QE EMR. Protein subunit ratio of (A) VCB:hBRD4:MZ1 = 1:1:5; (B) VCB: hBRD4 = 1:1 in 200 mM ammonium acetate, pH 7.4. Identified peaks in the mass spectra are indicated according to the legend and labelled with their charge. The spectra are dependent on instrumental tune conditions; spectrum (A) was adjusted to show minimal fragmentation, which is desired.

Collisional activation and electron capture induce complementary fragmentation of the ternary complex

The use of charge reducing agents can preserve protein ions in a more native-like state in the gas-phase, a state that is resistant to coulombic repulsion-induced unfolding (Khristenko et al., 2019; Lemaire et al., 2001). After buffer exchange to the charge-reducing ethylenediamine diacetate (EDDA), we observed a shift to lower charge states (15+, 14+, 13+ and 12+, Figure 3B) vs. ammonium acetate (16+, 15+, 14+ and 13+, Figure 2A).

Figure 3.

Native MS of the ternary complex introduced from 100 mM EDDA and submitted to CID/ECD. (A) Schematic showing the experimental setup. (B) Mass spectrum of the intact ternary complex upon low ISCID. Product-ion mass spectra induced by (C) increased ISCID, (D) increased CID, and (E) low ISCID with ECD. Identified peaks in the mass spectra are indicated according to the legend and labelled with their charge state.

Following the success of native MS, we probed the noncovalent interactions characteristic of this ternary complex using gas-phase activation. One approach is the relatively fast fragmentation of ECD conducted on an FT-ICR mass spectrometer equipped with in-source collisional activation (ISCID), an additional activating region (CID), and ECD to examine subunit disassociation (Figure 3A).

ISCID at low translational energy up to 77 V of acceleration does not fragment the intact ternary complex (Figure 3B). Upon further increases in ISCID, elimination of MZ1 occurs to give the binary complex [VCB-hBRD4] (Figure 3C, for deconvolution of the mass spectra see Figure S1). The protein complexes with higher charge states are more prone to CID; the greater charging leads to higher relative translational energy and more internal energy deposition in addition to increased coulombic repulsion. At 90 V ISCID, the 14+ and 13+ ternary complexes are relatively depopulated via MZ1 disassociation whereas the 12+ ternary complex exhibits an apparent relative increase in abundance, indicating its higher stability and lower fragmentation. The only charge state observed for MZ1 is 1+, consistent with a decrease by one charge between the ternary complex ion and the binary complex product ion (i.e., a 1+ MZ1 is ejected from a 13+ ternary complex producing a 12+ binary complex). The ejection of a neutral MZ1 from the complex seems unlikely owing to the coulombic repulsion-based nature of CID fragmentation. With subsequent additional collisional activation (30 V), the fragments are further activated to give the product ions [VCB-hBRD4], VCB, hBRD4, MZ1, and an MZ1 fragment (Figure 3D). None of the ternary complex survives this second stage of collisional activation, and much of the [VCB-hBRD4] product ions have dissociated further via loss of the peripheral hBRD4.

With submission of the intact complex to ECD (ISCID 77 V), we observed charge reduction, formation of peptide fragment ions, dissociated hBRD4, and [VCB-MZ1] (Figure 3E). (Cui et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2011). ECD peptide product-ion mass spectra were complex owing to peak interference with abundant MZ1, its adduct ions (Figure S2), and extensive noncovalent interactions throughout the ternary complex. For example, ECD of a natively folded protein can result in electron capture but no dissociation (ECnoD) whereby backbone cleavage does occur upon electron capture, but noncovalent interactions between the fragment and the remaining complex do not allow separation of the two product ions. Thus, the ECD efficiency for a native species is often less than when it is denatured (Horn et al., 2000). To increase the ECD of this protein complex, we explored several ISCID activation conditions designed to overcome the protein-protein interactions; however, few products were definitively identified.

Overall, using CID, we observed sequential ejection of first the PROTAC, MZ1, followed by dissociation of the POI, hBRD4. Upon ECD, however, we observe ejection of the POI. Interestingly, the product ions containing VCB subunits (i.e., VHL, elongin B, or elongin C) are of relatively low abundance. This preservation of VCB in the fragments from the ISCID and ECD experiment strongly suggests that these techniques primarily probe PROTAC-induced interactions, with minimal complexity induced by VCB subunit dissociation.

CID and ion mobility show ternary complexes adopt a distribution of conformations

To understand better the topologies responsible for the gas-phase dissociation pathways, we conducted additional collisional activation experiments coupled with ion mobility spectrometry (IMS). Collisional activation can be applied both pre- and post-IM separation, yielding unique views of the ternary complex and its fragmentation pathways. It is now well established that scanning the collisional energy prior to measuring the ion mobility reports on collision induced unfolding (CIU) in the gas-phase (Dixit et al., 2018). Additionally, CID conducted post IM separation allows correlations of product ions with their precursor ion conformations (e.g., native or unfolded). In this and the next section, we use both pre- and post-IM collisional activation to study the relationship between the gas-phase structure of the ternary complex and their corresponding dissociations.

Using the Q-IMS-ToF instrument, we observed an intact ternary complex with 12+ through 15+ charge states (Figure 4A). Furthermore, we saw ions for [VCB + MZ1] and hBRD4, and these could result from either incomplete ternary complex formation in solution or fragmentation (as in Figure 3C). In the 2D IM-MS representation, two trendlines are clearly observed consistent with two conformational populations (Figure 4B). Each IM distribution represents a topological status of the protein ternary complex in the gas phase whose distribution is presumably a function of internal energy. The 13+ ternary complex shows preference for more compact conformations, the 15+ ternary complex preference for more extended conformations, and the 14+ ternary complex a mixture of both. After extraction of the IM chromatograms for each charge state and deconvolution, the IM chromatograms can further be described with six unique conformational populations (CCSs: ~ 4000, ~ 4500, ~ 5000, ~ 5500, ~ 6000 and ~ 6500 Å2, Figure 4C). Considering that the more extended conformers are preferred at increasing charge, we conclude that the most compact conformational population (~ 4000 Å2) is most likely to resemble the “native-like” ternary complex, whereas the more extended conformers are likely induced by collisional activation and coulombic repulsion prior to separation by IM. This most compact conformational population has a similar CCS to model protein complexes of similar molecular weight and charge (Bush et al., 2010) (avidin, 64 kDa, 15–17+, 4150–4160 Å2; transthyretin, 56 kDa, 14–16+, 3840–3880 Å2) further supporting the assignment as the most “native-like” conformers of the ternary complex.

Figure 4.

IM-MS analysis of the ternary complex introduced from 100 mM EDDA. (A) Native mass spectrum of the intact ternary complex. Other identified species are labelled using the symbols in the legend and charge state. (B) Square root scale of drift time vs m/z ion mobility spectrum. (C-E) Ion mobility profiles of the 13+, 14+, and 15+ intact ternary complex with Gaussian deconvolution in color, respectively.

The stepwise collisional activation of mass-selected ternary complex ions followed by IMS separation provides information on both the stepwise unfolding of the protein complex (CIU) and its dissociation (CID) to eliminate subunits (Figure 5). Low energy collisional activation of protein complex ions usually induces charge stripping and peripheral subunit unfolding (i.e., CIU). With increasing collisional activation, unfolding occurs to give loss of quaternary noncovalent interactions, and the charge migrates onto the increasingly unfolded subunit (as evidenced by asymmetric charge partitioning between the product ions) prior to eventual subunit dissociation (i.e., CID) (Jurchen and Williams, 2003; Konermann, 2009; McAllister et al., 2015; Popa et al., 2016). Alternatively, CID of some charge-reduced protein complexes follow an alternative pathway with nonperipheral and low charge state subunit ejection (Pagel et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2020).

Figure 5.

Pre-IMS collisional activation of the 14+ and 15+ ternary complex. (A) Schematic showing the experimental setup. (B) and (F) Deconvoluted ion mobility profiles of the surviving intact 14+ and 15+ ternary complexes, respectively, with variable pre-IMS collisional activation. (C) and (G) CIU fingerprints of the 14+ and 15+ ternary complex, respectively. (D) and (H) Mass spectra showing the CID products after mass isolation of the 14+ and 15+ ternary complexes, respectively. (E) and (I) the change in relative abundances (calculated from extracted IMS areas) of product ions relative to the starting conditions. The buffer was 100 mM EDDA, pH 7.4.

CIU of the intact ternary complex follows an expected pattern, showing distinct transitions from more compact to more extended conformers (Figure 5B, 5C, 5F, and 5G). Although the largely compact 13+ ternary complex undergoes very little CIU (Figure S3), the more compact conformers of the intact 14+ protein complex ions are increasingly converted to those with larger CCSs (~ 5000, ~ 5500, ~ 6000, and 6500 Å2, Figure 4C). At the highest collision energy, the compact conformers (~ 4000 and ~ 4500 Å2) are almost completely depopulated in favor of extended conformers, and ultimately a new, even more extended conformation appears (CCS ~ 6500 Å2). As noted previously, most of the 15+ ternary complex, in the absence of collisional activation, already exists as extended conformers, but those compact conformers that remain are also depopulated upon CIU (Figure 5F). At the highest collision energy, the majority conformer converts to a more extended conformer (~ 5500 Å2), but interestingly, the 15+ ternary complex, in the absence of collisional activation never populates the most extended conformations (~ 6000 and ~ 6500 Å2). In comparison with CIU of the relatively globular homotetramer avidin, the PROTAC-induced ternary complex populates a much broader distribution of intact conformers (Bornschein et al., 2016). Thus, CIU of the PROTAC-induced ternary complex is more consistent with dynamic conformers capable of a range of motion without undergoing dissociation. Because IMS profiles of VCB alone are relatively homogeneous (Figure S4) and because limited CID of VCB is observed (Figure 3), we posit that population of the more extended conformers is likely a function of VHL-MZ1-hBRD4 interface dynamics and/or hBRD4 unfolding, and not dynamic motion within VCB.

The product-ion mass spectra of the mass selected 14+ and 15+ ternary complex ions are interestingly unique (Figure 5D and 5H). To illustrate better the changing production abundances upon increasing collisional activation of the major species, we show the difference in their relative abundance (measured by IM integrated areas) from the starting conditions, combining all charge states (Figure 5E and 5I). The most abundant CID product ions of the mass-isolated 14+ intact ternary complex are the [VCB-hBRD4] binary complex and MZ1; the elimination of MZ1 1+ from the 14+ ternary complex produces 13+ binary complex fragment ions (Figure 5D). Other product ions are also released including the peripheral elongin B and a hBRD4 of low abundance. The relative abundances of ejected MZ1 and [VCB-hBRD4] from the mass selected 15+ ternary complex are lower than those of the 14+ ternary complex (Figure 5I). The relative abundance of released elongin B has not changed significantly, and that of hBRD4 has slightly increased. [VCB-MZ1] forms from the 15+ ternary complex despite not being observed previously using CID (Figure 3); the m/z of the mass-isolated 15+ ternary complex (m/z 3830) is very similar to that of the 11+ [VCB-MZ1] ions (m/z 3845), suggesting it was co-isolated with the 15+ ternary complex and is not a product of 15+ ternary complex fragmentation. Comparison of the IM profiles of binary complex product ions with those of their ternary complex parent ions provides further insight (Figure S3); the 12+ binary complex is similarly compact as the 13+ ternary complex ions, and the 14+ binary complex is similarly extended as the 15+ ternary complex ions. Together, these results suggest that minimal conformational changes are necessary for MZ1 ejection, and that some population of the extended conformers must retain some hBRD4-VHL protein-protein interactions necessary to retain the binary complex after MZ1 dissociation.

Ternary complex parent ion conformations correlate with CID fragmentation pathways

Although collisional activation prior to IM separation (i.e., CA-IMS-MS) induces CIU and yields some CID information, the source of the CID product ions with reference to their precursor ion conformations are lost. This can be regained with collisional activation following IM separation, whereby several ternary complexes are separated according to conformation and collisionally activated. With post-IM collisional activation, those ternary complex conformations that did not experience subunit dissociation can be examined by their IM profile; that is, the IM profiles of survivor ternary complex ions represent those conformations less prone to fragmentation. To establish a relationship between ternary complex conformation and dissociation patterns, we used pre-IM collisional activation to populate both the gas-phase compact and extended conformers, separated them by IM, and then used further collisional activation to correlate fragmentation pathways with the conformation of the ternary complex ion.

As noted previously (Figure 4C), the 13+ ternary complex is primarily compact (~ 4000 Å2). Upon low-energy activation following IM separation, the 13+ ternary complex (~ 4000 Å2) depopulates by subunit dissociation as seen by a relative decrease in its abundance (Figure 6B and 6C). At higher collision energies, subunit dissociation occurs preferentially from the more extended conformers (~ 4500 Å2 and ~ 5000 Å2). The dominant product ions are clearly MZ1 and the binary complex [hBRD4-VCB] (Figure 6D and 6E).

Figure 6.

Post-IMS collisional activation of the 13+, 14+ and 15+ ternary complexes. (A) Schematic showing the experimental setup. (B), (F) and (J) Deconvoluted ion mobility profiles of the surviving 13+, 14+ and 15+ ternary complexes, respectively, with variable post-IMS collisional activation. (C), (G) and (K) IM fingerprints of the surviving 13+, 14+ and 15+ ternary complex ions, respectively. (D), (H) and (L) CID mass spectra showing ionic products after mass isolation of the 13+, 14+ and 15+ ternary complex, respectively. (E), (I) and (M) the change in relative abundances (calculated from extracted IMS areas) of fragmentation product ions vs. that of the starting conditions. The buffer used to introduce the sample was 100 mM EDDA, pH 7.4.

The 15+ ternary complex populates at least three conformations with a clear preference for extended conformers. Aside from low collision energy dissociation from the compact conformers (~ 4500 Å2) to eject protein subunits, the IM profiles of surviving 15+ ternary complex ions indicate no clear preferential subunit dissociation from any of the conformers, but gradual shifts in survivor ion CCS do suggest a slight preference for CID of extended conformers (Figure 6J and 6K). The CID product-ion mass spectra of the 15+ ternary complex again indicate decreased ejection of MZ1 and a higher propensity for dissociation to hBRD4 (Figure 6L and 6M).

The 14+ ternary complex exists in the five IMS conformational populations comprised of all the conformers of the 13+ and 15+ ternary complexes. Interestingly, the IM profiles of survivor 14+ ternary complex ions suggest a clear preference for depopulation of the most compact conformers (~ 4000 Å2 and ~ 4500 Å2) (Figure 6F and 6G). This contrasts from the expected dissociation of an already unfolded protein complex. The CID product ions from depopulation of more compact conformers show a clear preference for MZ1 ejection in competition with formation of hBRD4 and elongin B (Figure 6H and 6I). These post-IM CID results are consistent with the 14+ ternary complex existing as a mixture of conformations seen for 13+ and 15+ ternary complexes.

ECD and CID fragmentation are complementary

Overall, collisional activation after ion mobility separation of charge-reduced ternary complex clearly shows that the more compact ternary complex conformers primarily eject MZ1 to form the binary complex, whereas the more extended conformers preferentially lose peripheral hBRD4 and elongin B. That MZ1 dissociates from the more compact ternary conformers (especially the 13+ ternary complex ions) indicates that these conformers must possess protein-protein interactions between VHL and hBRD4, consistent with a similar protein-protein interface reported in the crystal structure (Gadd et al., 2017) (Figure 7A). The more extended ternary complex conformers (especially 15+) are more likely to have weaker protein-protein interactions prior to CID, and as a result, product ions representing hBRD4 are more abundant (Figure 7B). Interestingly, CID of elongin B, positioned remotely from the PROTAC on the ternary complex, does not change significantly regardless of conformation, serving as a control for the differences seen in the MZ1 elimination (Figure 7C). The differences in fragmentation, now attributable to compact vs. extended conformations, offer an explanation for the ISCID results (Figure 3C and 3D). The most abundant ternary complex charge states introduced to the FT-ICR instrument are 13+, followed by 12+ and 14+ (Figure 3). According to the IMS-MS experiments, the 13+ ternary complex preferentially exists in a compact conformation(s) (Figure 4C), and collisional activation induces very little CIU (Figure S3). (We expect the 12+ ternary complex to be similarly compact and CIU resistant (Figure 4A, m/z = 4787)). Upon ISCID, the preferential ejection of MZ1 from all three charge states of the ternary complex and survival of the binary complex (Figure 3C) suggests that the 14+ ternary complex on the FT-ICR instrument is similarly compact. Together, these results suggest that under starting conditions for ECD (Figure 3B), native-like compact conformers are populated with minimal CIU. Furthermore, ECD is fast fragmentation accompanied by less gas-phase rearrangement. Dissociation of the protein subunits does occur upon ECD; low energy ISCID followed by ECD induces dissociation of the hBRD4 (the POI) from [VCB-MZ1], further highlighting the differences in energy input between CID and ECD (Figure 3E). Taken together, the IM, CIU, and CID results effectively offer an explanation of the unique fragmentation patterns for ISCID and ECD and their correlation to the protein complex topology induced by PROTAC linking.

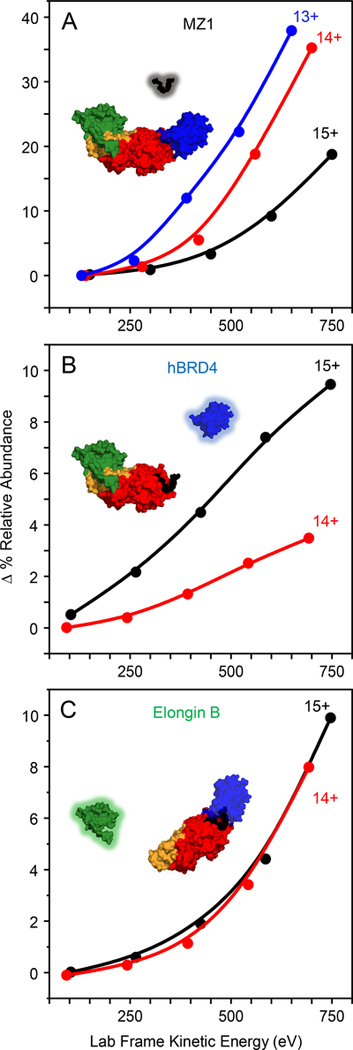

Figure 7.

CID fragmentation pathways of ternary complex ions are dependent upon the charge state and conformational preference of the parent ion. Summary of relative abundances (Δ%RA from IMS areas) of (A) MZ1, (B) hBRD4, and (C) Elongin B product ions as a function of post-IM activation energy, produced from mass isolated 13+, 14+, and 15+ ternary complex ions (blue, red, and black lines, respectively). Compiled from the data in Figure 6.

CID of charge-reduced protein complexes has been reported to proceed via alternative dissociation pathways. Most notably, Wang et al. observed non-peripheral subunit dissociation from charge reduced 20S proteasome complex; this effect was more pronounced with lower charge state parent ions and not observed without charge reduction (Wang et al., 2020). Furthermore, Pagel et al. observed that CID of charge reduced transthyretin produced subunit product ions with lower charge states (Pagel et al., 2010). Bornschein, et al. reported the collision induced compaction of charge reduced avidin (Bornschein et al., 2016). All are potentially explained by heterolytic ion pair scission and rearrangement (i.e., salt bridge rearrangement (Loo and Loo, 2016)). Similarly, salt-bridge rearrangement presents a potential explanation for the results of post-IM CID of the PROTAC-induced ternary complex.

Of note, the specific non-covalent interactions observed in solution inherently differ from those observed in the gas-phase; more specifically salt-bridges are strengthened by desolvation and the low dielectric environment of vacuum. Therefore, we cannot claim that the non-covalent interactions reported by the reported crystal structure are the same as those indicated by the results observed here; however, we instead posit that these results suggest protein-protein contact between VHL and hBRD4. For ternary complexes with weaker protein-protein interactions (such as AT1) and negative protein-protein interactions (such BRD4 mutants described in the introduction), we would not expect to observe PROTAC ejection and retention of a complementary binary complex. These experiments are the obvious next step in characterizing this methodology and establishing its generality for PROTACs.

Significance

POI-E3 ubiquitin ligase interactions may be more important for PROTAC efficacy than the affinity of binding the PROTAC, but heretofore, evidence of these intermolecular interactions comes only from mutational studies and x-ray crystallography, both limited by the slow turnaround for screening promising PROTACs. Here, we demonstrate that utilization of native MS and gas-phase fragmentation can assist the design of improved PROTACs. The relevance of their gas-phase properties to solution chemistry is assured by generating lower charged protein assemblies by electrospray from an EDDA solution, producing ions that are even more native-like than those formed from the often-used ammonium acetate solution. Several gas-phase fragmentations, induced by either collisions or electron capture, when used in combination, interrogate the VHL-hBRD4 interface correlated with the efficacy of MZ1. Using CID, we observed that the more compact ternary complexes have protein-protein interactions that allow a binary [VCB-hBRD4] complex to survive upon elimination of the MZ1 (the PROTAC linker); this protein complex is not seen in solution without the PROTAC. Alternatively, ECD induces dissociation of the POI from [VCB-MZ1] regardless of these intermolecular interactions. With improved understanding of the gas-phase fragmentations of PROTAC-bound ternary complexes, fast-screening of their topology and interactions by using CID and ECD analysis can be implemented. Furthermore, we may be able to elucidate protein-protein interactions of other novel complexes using native MS and gas-phase dissociation techniques, affording a measure of the effectiveness of small, therapeutically promising organic molecules designed to link protein complexes. The outcomes also add to the growing evidence of the biological relevance of structural mass spectrometry and demonstrate surprising fragmentations that are enabled.

Star Method Text

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

• Lead Contact

All requests for additional information and reagents should be directed to the Lead Contact, Michael L. Gross (mgross@wustl.edu).

• Materials Availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

• Data and Code Availability

This study did not generate any data sets or code.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

• Bacterial Strains

Escherichia coli (E. coli) BL21 (DE3) cells were used for protein expression. (Novagen, Cat#70235). After plasmid transformation, the cells were grown on LB-agar plates overnight at 37 °C. A single colony was selected and used to inoculate 50 mL starter cultures, then grown in LB broth (Cellgro, Cat#46–050-CM) overnight at 37 °C with 225 rpm rotary shaking. 1 L of TB medium (Cellgro, Cat#46–055-CM) was inoculated with an aliquot of the starter culture and grown at 37 °C with rotary shaking at 225 rpm until OD600 = 1.0 (~3.25 hrs) before induction.

METHOD DETAILS

• Sample Preparation

The PROTAC MZ1 and the protein subunits were provided by Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS). Detailed synthetic procedures of MZ1 are similar to those described elsewhere (Zengerle et al., 2015) and briefly described as follows.

To a solution of (2S,4R)-1-((S)-2-amino-3,3-dimethylbutanoyl)-4-hydroxy-N-(4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)benzyl)pyrrolidine-2-carboxamide (180 mg, 0.418 mmol), 1-(9H-fluoren-9-yl)-3-oxo-2,7,10,13-tetraoxa-4-azapentadecan-15-oic acid (215 mg, 0.502 mmol), diisopropylethylamine (0.219 mL, 1.254 mmol) in dimethylformamide (DMF) (2 mL) at RT was added (1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxide hexafluorophosphate (HATU) (191 mg, 0.502 mmol) in DMF (2 mL) dropwise. The reaction was stirred at RT for 10 min. The reaction was diluted with ethyl acetate (20 mL) and water (10 mL). The organic layer was separated and washed with water (3X) and brine (1X). The organic layer was then dried over MgSO4, filtered and concentrated to give crude (9H-fluoren-9-yl)methyl ((S)-13-((2S,4R)-4-hydroxy-2-((4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)benzyl)carbamoyl)pyrrolidine-1-carbonyl)-14,14-dimethyl-11-oxo-3,6,9-trioxa-12-azapentadecyl)carbamate (350 mg, 0.374 mmol, 89% yield), which was used without further purification. MS: [M + H]+ = 842.2

To a solution of (9H-fluoren-9-yl)methyl ((S)-13-((2S,4R)-4-hydroxy-2-((4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)benzyl)carbamoyl)pyrrolidine-1-carbonyl)-14,14-dimethyl-11-oxo-3,6,9-trioxa-12-azapentadecyl)carbamate (350 mg, 0.416 mmol) in 20% piperdine in DMF (2 mL, 0.416 mmol) at room temperature (RT). The mixture was stirred at RT for 2 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo and to the resulting residue was added acetonitrile (ACN) (5 mL). The resulting precipitate was filtered off and the filtrate purified with reversed-phase ISCO (50 g C18 gold column, flow rate: 40 mL/min, solvent A: 5% ACN, 95% H2O, 0.01M NH4OAc solvent B: 5% H2O, 95% ACN, 0.01M NH4OAc, gradient: 0% B to 100% B in 40 min). The desired fractions were freeze dried to afford (2S,4R)-1-((S)-14-amino-2-(tert-butyl)-4-oxo-6,9,12-trioxa-3-azatetradecanoyl)-4-hydroxy-N-(4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)benzyl)pyrrolidine-2-carboxamide as a white solid (120 mg, 0.190 mmol, 45.6% yield). MS: [M + H]+ = 620, 1H NMR (400 MHz, dimethylsulfoxide-d6) δ 9.03 (s, 1H), 7.51 – 7.42 (m, 4H), 4.60–4.21 (m, 6H), 4.02 (s, 3H), 3.80–3.52 (m, 8H), 2.60 – 2.57 (m, 2H), 2.52 – 2.46 (m, 3H), 2.25 – 2.04 (m, 2H), 1.98 – 1.91 (m, 2H), 1.04 – 0.92 (m, 9H).

To a solution of (2S,4R)-1-((S)-14-amino-2-(tert-butyl)-4-oxo-6,9,12-trioxa-3-azatetradecanoyl)-4-hydroxy-N-(4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)benzyl)pyrrolidine-2-carboxamide (23.19 mg, 0.037 mmol) and (S)-2-(4-(4-chlorophenyl)-2,3,9-trimethyl-6H-thieno[3,2-f][1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a][1,4]diazepin-6-yl)acetic acid (15 mg, 0.037 mmol) in DMF (1.0 mL) at RT was added diisopropylethylamine (0.020 mL, 0.11 mmol). To the resulting solution was slowly added HATU (0.017 g, 0.045 mmol) in DMF (0.25 mL). The reaction was stirred at RT for 2h. The mixture was diluted with methanol (MeOH) and purified by preparative reversed-phase HPLC (Phen Luna 5 μm 30 × 100 mm, 40 mL/min flow rate with gradient of 20% B - 100% B over 10 min, hold at 100% B for 5 min. (A: 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water/MeOH (90:10), B: 0.1% TFA in water/MeOH (10:90) monitoring at 254 nm). The fractions containing product were concentrated and freeze dried to give (2S,4R)-1-((S)-2-(tert-butyl)-17-((S)-4-(4-chlorophenyl)-2,3,9-trimethyl-6H-thieno[3,2-f][1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a][1,4]diazepin-6-yl)-4,16-dioxo-6,9,12-trioxa-3,15-diazaheptadecanoyl)-4-hydroxy-N-(4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)benzyl)pyrrolidine-2-carboxamide MZ-1 (12 mg, 0.011 mmol, 30.4% yield) MS: [M + H]+ = 1002.4, 1H NMR (400 MHz, methanol-d4) δ 9.01 (s, 1H), 7.49 – 7.40 (m, 8H), 4.77 – 4.64 (m, 3H), 4.61 – 4.47 (m, 3H), 4.11 – 4.02 (m, 3H), 3.74 – 3.54 (m, 12H), 3.51 – 3.40 (m, 3H), 3.31–3.33 (m, 2H), 2.73 (s, 3H), 2.51 – 2.43 (m, 6H), 1.73 – 1.68 (m, 3H), 1.07 – 1.00 (m, 9H).

Protein expression and purification procedures were similar to those described elsewhere (Gadd et al., 2017). Briefly, N-terminally His6-TEV-tagged VHL (aa 54–213) in pET28 (Galdeano et al., 2014)and Elongin C (aa 17–112) plus Elongin B (aa 1–104) in a bi-cistronic pACYC-Duet-1 vector (Uniprot accession numbers listed in SI Table 1) were co-expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells (Novagen Cat#70235, Merck KGaA)(Galdeano et al., 2014). Purified plasmid DNA for the two expression vectors was co-transformed into the competent cells according to the manufacturer’s instructions and plated onto LB-agar plates containing 30 μg/mL each chloramphenicol and kanamycin. After incubating the plates overnight at 37 °C, a single colony was selected and used to inoculate 50 mL starter cultures grown overnight with rotary shaking at 225 rpm at 37 °C in LB (Cellgro Cat#46050-CM) plus 30 μg/mL each chloramphenicol and kanamycin. Thomson 2.5 L ultra-yield flasks containing 1 L of Terrific Broth (TB) medium (Corning Cat#46–055-CM) plus 30 μg/mL each chloramphenicol and kanamycin were inoculated with 14 mL of the saturated starter culture and grown at 37 °C with rotary shaking at 225 rpm. The cultures were grown until they reached an OD600nm = 1.0 (about 3.25 h), and the flasks were pulled from the shaking incubator and placed on ice for 30 min. The cultures were induced by adding isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 0.5 mM, returning to the shaking incubator, and incubating at 20 °C for 20 h. The cell paste was harvested from the cultures by sedimentation at 5,000 rpm using a F9S-4×1000Y rotor in a Sorvall RC6plus centrifuge chilled at 4 °C. The pellets of cell paste were collected and stored at − 80 °C. Frozen cell paste from 2 L of culture (28 g) was thawed by suspending with stirring in 200 mL of Lysis Buffer (20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) (pH 7.5), 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), cOmplete™, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, 4 tablets), 20 U/mL Benzonase® (Merck KGaA; 16 μL of 250 U/μL Benzonase® stock; 4,000 Units) and sonicating on ice with a Branson Digital Sonifier at 70% power using a flat tip (1.2 s on; 0.6 s off for 30 s-; repeating 4 times with 5 min rests on ice in between). The lysate was clarified by sedimentation at 26,000 rpm for 30 min in a Thermo ultracentrifuge with a F40L-8×100 rotor. The complex was purified from the clarified lysate by affinity capture using a 5 mL column packed with Nickel Sepharose 6 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare Cat#17–5318-01) and imidazole elution. The component corresponding to the elution peak was concentrated by centrifugal ultrafiltration (Amicon Ultra-15 10 KDa, Millipore-Sigma) and further purified on a Superdex 200 16/60 column equilibrated with 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 250 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA. Fractions containing the enriched complex, eluting as a major peak centered at 86 mL, were pooled and treated with TEV protease (AcTEV, ThermoFisher Cat #12575015). The complex, minus the tag, was collected in the flow through following chromatography on a 1 mL column packed with Nickel Sepharose 6 Fast Flow. The purified complex was buffer exchanged into a final storage buffer of 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA using PD10 desalting columns (GE Healthcare Cat#17–0851-01), flash-frozen, and stored at −80 °C. N-terminally His6-TVMV-tagged human BRD4 bromodomain 2 (aa 333–460) (Uniprot accession number listed in SI Table 1) in a pET28 expression vector transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells was expressed and lysed using similar methods as described above, except only 30 μg/mL kanamycin was included in the culture medium to maintain selection for the expression vector. The His6-tagged BRD4(333–460) was purified from the clarified lysate by affinity capture using a 15 mL column packed with Nickel Sepharose 6 Fast Flow and imidazole elution. Elution fractions enriched in His-BRD4(333–460) were pooled and treated with His-tagged Tobacco Vein Mottling Virus (TVMV) protease (Nallamsetty et al., 2004) to remove the His-tag. BRD4(333–460), minus the tag, was collected in the flow through following chromatography on a 15 mL column packed with Nickel Sepharose 6 Fast Flow. BRD4(333–460) was further purified by size-exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 26/60 column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), and the purified protein was flash-frozen and stored at −80 °C.

For native MS experiments, each subunit of the protein complex was submitted to buffer exchange with two different buffer salts. To acquire the data in Figure 2, the buffer was 200 mM ammonium acetate, and for all others, 100 mM EDDA (pH = 7.4) (Millipore Sigma, Saint Louis, MO). VivaSpin 500 centrifugal concentrators (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany), MWCO 5 kDa, were used for buffer exchange of hBRD4, and MWCO 10 kDa for VCB. To prepare the ternary complex, the components were mixed at a molar ratio of VCB:hBRD4:MZ1 of 1:1:5 to give a final ternary protein complex concentration of ~5 μM. The sample solution was then incubated for 30 min at 4 °C.

• Native MS

Approximately 4 μL of incubated sample buffer exchanged into 200 mM ammonium acetate (pH = 7.4) was loaded in a platinum-coated emitter (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and electrosprayed directly into the mass spectrometer via a nanoESI source. An Exactive Plus EMR Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) was used to obtain the native mass spectrum of the complex with the following settings: capillary voltage of 1.5 kV, capillary temperatures of 100 °C and 50 °C, in-source CID of 10 V, and HCD collision energy of 10 V. The AGC target was set to 5 e6. The mass resolving power was 140,000 at m/z = 200. The spectra were dependent on instrumental tune conditions, and the conditions for data in Figure 2A were adjusted to show minimal fragmentation, which is desired. Data processing was done by using Thermo Xcaliber Qual Browser 4.0.

• Native MS and top-down ECD

ISCID and ECD product-ion mass spectra were acquired on a Bruker Scientific 12 T FT-ICR mass spectrometer (Bruker, Bremen, Germany) using 4 μL of incubated sample buffer exchanged into 100 mM EDDA (pH = 7.4), loaded into a platinum-coated emitter (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA), and infused directly into the mass spectrometer via a nanoESI source. The source settings were capillary voltage 1.5 kV, drying gas temperature 100 °C, and drying gas flow rate 1.5 L/min. Skimmer I voltage was varied to pre-activate ions, and the downstream collision voltage was optimized for subsequent collisional activation. Other ion-optics parameters were adjusted to optimize signal intensities. Ion accumulation time was 3 s, and the time-of-flight cycle was 2.4 ms. All charge states in a narrow distribution were subjected to ECD with a pulse length of 0.03 s, bias of 1.4 V, lens of 14 V, and hollow-cathode current of 1.5 A. Peak picking was performed by calculating the FTMS centroid peak on Bruker Data Analysis. Peak deconvolution was performed by auto mass peak picking on Intact Mass™ (Protein Metrics Inc., Cupertino, CA).

• Native IMS-MS and Hybrid IMS-CID-MS

Approximately 4 μL of incubated sample buffer exchanged into 100 mM EDDA (pH = 7.4) was loaded into a platinum coated emitter (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and infused directly into a hybrid quadrupole ion mobility time-of-flight mass spectrometer Synapt G2 HDMS (Waters, Milford, MA) for IMS-MS, pre-IMS CIU/CID, and post-IMS CID analyses. Briefly, the instrument consisted of a quadrupole, a travelling wave ion guide (TWIG) trap infused with argon, a helium cell for collisional cooling, a nitrogen-infused travelling wave ion mobility device (TWIMS), a TWIG transfer cell, and an orthogonal time-of-flight mass spectrometer (oTOF). Voltage drops for pre-IMS and post-IMS collisional activation were applied between the exit of the previous device and the entrance to the TWIG trap and transfer cells, respectively. For ion transmission, the settings were: capillary voltage of 1.4 kV, sampling cone of 32 V, extraction cone of 2.2 V, and source temperature of 60 °C. The backing pressure was 7 ~ 8 mbar for better transferring the intact protein-complex ions. These source conditions were screened and determined to be necessary for desolvation and transmission of the intact ternary complex. Nitrogen was used as the carrier gas for ion-mobility experiments at a flow rate of 60 mL/min. The trap bias was 90 V, and helium cell gas flow was 120 mL/min. IMS wave velocity and wave height were 300 m/s and 20 V. For pre-IMS collisional activation, quadrupole mass isolated 13+, 14+ and 15+ ternary complex precursor ions were submitted to collisional activation in the TWIG trap region by using a potential difference of 0 to 50 V applied between the exit of the quadrupole and entrance of the TWIG-trap to induce gas-phase unfolding. The ions were then thermalized via subsequent collisional cooling in the argon-filled TWIG-trap and helium cell. For post-IMS CID, quadrupole mass isolated 13+, 14+ and 15+ ternary complexes were submitted to a constant potential difference of 20 V applied between the exit of the quadrupole and entrance of the TWIG-trap as before. The ions were mobility separated in the TWIMS, and subsequent collisional activation was applied using a potential difference of 10 ~ 50 V from the exit of the TWIMS device and entrance to the TWIG transfer cell.

MassLynx (Waters, Milford, MA) was used to extract ion mobility profiles and mass spectra. IM drift times were converted to CCS values as previously reported (Bush et al., 2010; Ruotolo et al., 2008) by using protein standards avidin, β-lactoglobulin monomer and dimer. The IM calibration yielded an R2 value of 0.9983 for the calibration plot. CIU Suite 2.0 was used to compile CIU fingerprints and to deconvolute the IM profiles (Polasky et al., 2019). Lab-frame kinetic energy was calculated as the charge state times the applied collision voltage drop. To calculate the delta % relative abundance (IMS area) of the different product ions, the extracted ion mobility chromatograms for each product ion were integrated within MassLynx. The resulting areas for each species of several charge states were then combined. The relative IMS area of each product ion was then normalized by calculating the % relative abundance normalized to the total ion abundance of the identified product ions (i.e., by dividing each product ion IMS area by the sum of all IMS areas * 100). To remove the potential influence of activation within other regions of the instrument, the % relative abundance for each product ion from the starting conditions (for pre-IM collisional activation both trap and transfer collision voltage drop of 4 V and 0 V, respectively; for post-IM collisional activation, 20 V of pre-IM collisional activation and 0 V of post-IM collisional activation) was subtracted from the % relative abundance calculated from different collisional activation parameters (for pre-IM collisional activation, trap voltage drop varied from 5 – 50 V; for post-IM collisional activation, the transfer voltage drops were from 10 – 45 V).

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | Novagen | Cat#70235 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| (2S,4R)-1-((S)-2-amino-3,3-dimethylbutanoyl)-4-hydroxy-N-(4-(4-methylthiazol-5-yl)benzyl)pyrrolidine-2-carboxamide | Millipore Sigma | Cat#901490 CAS: 1448189–80-7 |

| 1-(9H-fluoren-9-yl)-3-oxo-2,7,10,13-tetraoxa-4-azapentadecan-15-oic acid | Millipore Sigma | Cat#CDS020947 CAS: 139338–72-0 |

| (1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxide hexafluorophosphate (HATU) | Millipore Sigma | Cat#445460 CAS: 148893–10-1 |

| (S)-2-(4-(4-chlorophenyl)-2,3,9-trimethyl-6H-thieno[3,2-f][1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a][1,4]diazepin-6-yl)acetic acid | Millipore Sigma | Cat#SML1524 CAS: 1268524–70-4 |

| MZ1 | This paper (as Zengerle et al., 2015) | N/A |

| Cellgro Miller’s LB broth | Corning | Cat#46–050-CM |

| Cellgro Terrific Broth® (TB) | Corning | Cat#46–055-CM |

| Chloramphenicol | Millipore Sigma | Cat#C0378 |

| Kanamycin Sulfate | Millipore Sigma | Cat#60615 |

| Isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) | Millipore Sigma (Roche) | Cat#10724815001 |

| cOmplete™ EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail | Millipore Sigma (Roche) | Cat#11873580001 |

| Benzonase® endonuclease | Millipore Sigma (Merck KGaA) |

Cat#E1014 |

| AcTEV protease | ThermoFisher | Cat#12575015 |

| His6-TVMV protease | Nallamsetty, et al., 2004 | N/A |

| Ammonium acetate, 99.999% purity | Millipore Sigma | Cat#372331; CAS: 631–61-8 |

| Ethylene diamine diacetate | Millipore Sigma | Cat#420352; CAS: 38734–69-9 |

| hBRD4 (333–460) | This paper (as Gadd et al., 2017) | Uniprot Q60885 |

| VHL (54–213) | This paper (as Gadd et al., 2017) | Uniprot P40337 |

| Elongin C (17–112) | This paper (as Gadd et al., 2017) | Uniprot Q15369 |

| Elongin B (1–104) | This paper (as Gadd et al., 2017) | Uniprot Q15370 |

| Deposited data | ||

| hBRD4 | Gadd et al.,2017 | PDB: 2OUO |

| VCB | Gadd et al.,2017 | PDB: 1VCB |

| hBRD4-MZ1-VCB complex | Gadd et al.,2017 | PDB: 5T35 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pET28-His6-VHL54–213 | Galdeano et al., 2014 | N/A |

| pACYC-Duet-1-ElonginC17–112-ElonginB1–104 | Galdeano et al., 2014 | N/A |

| pET28-His6-BRD4333–460 | Gadd et al., 2017 | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| MassLynx 4.2 | Waters Corp. | https://www.waters.com |

| CIUSuite 2.0 | Polasky et al., 2019 | https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/ruotolo/software/ |

| Intact Mass™ | Protein Metrics Inc. | https://proteinmetrics.com |

| Other | ||

| 12 T FT-ICR MS | Bruker Daltonics | https://www.bruker.com |

| Synapt G2 HDMS | Waters Corporation | https://www.waters.com |

| Exactive Plus EMR orbitrap MS | Thermo Scientific | https://www.thermofisher.com |

Highlights.

Native MS yields structural analysis of a PROTAC-induced ternary complex.

Multiple activation methods probe unique subunit dissociation pathways.

Conformational analysis identifies two gas-phase PROTAC complex topologies.

Subsequent subunit dissociation interrogates relevant protein-protein interactions.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Susan E. Kiefer, Frank Marsilio, Weifang Shan, Drs. Mark Witmer, Louis Lombardo, and Olafur Gudmundsson of Bristol Myers Squibb Company for their support of this project and the members of M.L.G. lab for assistance. This work was supported by a research collaboration with Bristol Myers Squibb Company and by the National Institutes of Health (P41GM103422 and R24GM136766).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

Michael L Gross is an unpaid member of the scientific advisory boards of Protein Metrics Inc. and Gen Next Technologies, two companies pursuing ideas in structural mass spectrometry.

Supplemental Information

Supplemental information includes deconvolution of CID and ECD spectra of the ternary complex acquired on the 12T FT-ICR-MS; full and expanded mass spectrum showing ECD products; pre-IMS CIU ion mobility profiles; IMS analysis of VCB; a table of protein constructs used throughout the study: which can be found with this article online.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- Allison T, and Bechara C (2019). structural mass spectrometry comes of new age: new insight into protein structure, function and interactions. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 47, 317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge R, Kessler D, Rumpel K, Ettmayer P, Meinhart A, and Clausen T (2020). Native Mass Spectrometry Can Effectively Predict PROTAC Efficacy. ACS Central Science 6, 1223–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge R, Migas LG, Das RK, Pappu RV, Kriwacki RW, and Barran PE (2019). Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry Uncovers the Impact of the Patterning of Oppositely Charged Residues on the Conformational Distributions of Intrinsically Disordered Proteins. J Am Chem Soc 141, 4908–4918. 10.1021/jacs.8b13483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeri Erba E, Signor L, and Petosa C (2020). Exploring the structure and dynamics of macromolecular complexes by native mass spectrometry. J Proteomics 222, 103799. 10.1016/j.jprot.2020.103799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondeson DP, Mares A, Smith IE, Ko E, Campos S, Miah AH, Mulholland KE, Routly N, Buckley DL, Gustafson JL, et al. (2015). Catalytic in vivo protein knockdown by small-molecule PROTACs. Nat Chem Biol 11, 611–617. 10.1038/nchembio.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondeson DP, Smith BE, Burslem GM, Buhimschi AD, Hines J, Jaime-Figueroa S, Wang J, Hamman BD, Ishchenko A, and Crews CM (2018). Lessons in PROTAC Design from Selective Degradation with a Promiscuous Warhead. Cell Chem Biol 25, 78–87.e75. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornschein RE, Niu S, Eschweiler J, and Ruotolo BT (2016). Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry Reveals Highly-Compact Intermediates in the Collision Induced Dissociation of Charge-Reduced Protein Complexes. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 27, 41–49. 10.1007/s13361-015-1250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuker K, and McLafferty FW (2008). Stepwise evolution of protein native structure with electrospray into the gas phase, 10(−12) to 10(2) s. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 18145–18152. 10.1073/pnas.0807005105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodbelt JS (2014). Photodissociation mass spectrometry: new tools for characterization of biological molecules. Chem Soc Rev 43, 2757–2783. 10.1039/c3cs60444f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodbelt JS, Morrison LJ, and Santos I (2020). Ultraviolet Photodissociation Mass Spectrometry for Analysis of Biological Molecules. Chem Rev 120, 3328–3380. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush MF, Hall Z, Giles K, Hoyes J, Robinson CV, and Ruotolo BT (2010). Collision cross sections of proteins and their complexes: a calibration framework and database for gas-phase structural biology. Anal Chem 82, 9557–9565. 10.1021/ac1022953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalina MI, van den Heuvel RH, van Duijn E, and Heck AJ (2005). Decharging of globular proteins and protein complexes in electrospray. Chemistry (Easton) 11, 960–968. 10.1002/chem.200400395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins I, Wang H, Caldwell JJ, and Chopra R (2017). Chemical approaches to targeted protein degradation through modulation of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Biochem J 474, 1127–1147. 10.1042/BCJ20160762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui W, Zhang H, Blankenship RE, and Gross ML (2015). Electron-capture dissociation and ion mobility mass spectrometry for characterization of the hemoglobin protein assembly. Protein Sci 24, 1325–1332. 10.1002/pro.2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit SM, Polasky DA, and Ruotolo BT (2018). Collision induced unfolding of isolated proteins in the gas phase: past, present, and future. Curr Opin Chem Biol 42, 93–100. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson SD, Yang B, and Fallan C (2019). Proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) in ‘beyond rule-of-five’ chemical space: Recent progress and future challenges. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 29, 1555–1564. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eschweiler JD, Martini RM, and Ruotolo BT (2017). Chemical Probes and Engineered Constructs Reveal a Detailed Unfolding Mechanism for a Solvent-Free Multidomain Protein. J Am Chem Soc 139, 534–540. 10.1021/jacs.6b11678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnaby W, Koegl M, Roy MJ, Whitworth C, Diers E, Trainor N, Zollman D, Steurer S, Karolyi-Oezguer J, Riedmueller C, et al. (2019). BAF complex vulnerabilities in cancer demonstrated via structure-based PROTAC design. Nat Chem Biol 15, 672–680. 10.1038/s41589-019-0294-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadd MS, Testa A, Lucas X, Chan KH, Chen W, Lamont DJ, Zengerle M, and Ciulli A (2017). Structural basis of PROTAC cooperative recognition for selective protein degradation. Nat Chem Biol 13, 514–521. 10.1038/nchembio.2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galdeano C, Gadd MS, Soares P, Scaffidi S, Van Molle I, Birced I, Hewitt S, Dias DM, and Ciulli A (2014). Structure-guided design and optimization of small molecules targeting the protein-protein interaction between the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) E3 ubiquitin ligase and the hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) alpha subunit with in vitro nanomolar affinities. J Med Chem 57, 8657–8663. 10.1021/jm5011258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gault J, Liko I, Landreh M, Shutin D, Bolla JR, Jefferies D, Agasid M, Yen HY, Ladds MJGW, Lane DP, et al. (2020). Combining native and ‘omics’ mass spectrometry to identify endogenous ligands bound to membrane proteins. Nat Methods 17, 505–508. 10.1038/s41592-020-0821-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall Z, Politis A, and Robinson CV (2012). Structural modeling of heteromeric protein complexes from disassembly pathways and ion mobility-mass spectrometry. Structure 20, 1596–1609. 10.1016/j.str.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck AJ (2008). Native mass spectrometry: a bridge between interactomics and structural biology. Nat Methods 5, 927–933. 10.1038/nmeth.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan CJ, Carroll JA, Rohrs HW, Biswas P, and Gross ML (2009). Combined charged residue-field emission model of macromolecular electrospray ionization. Anal Chem 81, 369–377. 10.1021/ac8016532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn DM, Ge Y, and McLafferty FW (2000). Activated ion electron capture dissociation for mass spectral sequencing of larger (42 kDa) proteins. Anal Chem 72, 4778–4784. 10.1021/ac000494i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurchen JC, and Williams ER (2003). Origin of asymmetric charge partitioning in the dissociation of gas-phase protein homodimers. J Am Chem Soc 125, 2817–2826. 10.1021/ja0211508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khristenko N, Amato J, Livet S, Pagano B, Randazzo A, and Gabelica V (2019). Native Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry: When Gas-Phase Ion Structures Depend on the Electrospray Charging Process. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 30, 1069–1081. 10.1007/s13361-019-02152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konermann L (2009). A simple model for the disintegration of highly charged solvent droplets during electrospray ionization. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 20, 496–506. 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laganowsky A, Reading E, Hopper JT, and Robinson CV (2013). Mass spectrometry of intact membrane protein complexes. Nat Protoc 8, 639–651. 10.1038/nprot.2013.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaire D, Marie G, Serani L, and Laprévote O (2001). Stabilization of gas-phase noncovalent macromolecular complexes in electrospray mass spectrometry using aqueous triethylammonium bicarbonate buffer. Anal Chem 73, 1699–1706. 10.1021/ac001276s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lermyte F, Valkenborg D, Loo JA, and Sobott F (2018). Radical solutions: Principles and application of electron-based dissociation in mass spectrometry-based analysis of protein structure. Mass Spectrom Rev 37, 750–771. 10.1002/mas.21560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, and Song Y (2020). Proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC) for targeted protein degradation and cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol 13, 50. 10.1186/s13045-020-00885-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo RR, and Loo JA (2016). Salt Bridge Rearrangement (SaBRe) Explains the Dissociation Behavior of Noncovalent Complexes. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 27, 975–990. 10.1007/s13361-016-1375-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister RG, Metwally H, Sun Y, and Konermann L (2015). Release of Native-like Gaseous Proteins from Electrospray Droplets via the Charged Residue Mechanism: Insights from Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 12667–12676. 10.1021/jacs.5b07913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehmood S, Marcoux J, Hopper JT, Allison TM, Liko I, Borysik AJ, and Robinson CV (2014). Charge reduction stabilizes intact membrane protein complexes for mass spectrometry. J Am Chem Soc 136, 17010–17012. 10.1021/ja510283g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nallamsetty S, Kapust RB, Tözsér J, Cherry S, Tropea JE, Copeland TD, and Waugh DS (2004). Efficient site-specific processing of fusion proteins by tobacco vein mottling virus protease in vivo and in vitro. Protein Expr Purif 38, 108–115. 10.1016/j.pep.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottis P, and Crews CM (2017). Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras: Induced Protein Degradation as a Therapeutic Strategy. ACS Chem Biol 12, 892–898. 10.1021/acschembio.6b01068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacholarz KJ, and Barran PE (2016). Use of a charge reducing agent to enable intact mass analysis of cysteine-linked antibody-drug-conjugates by native mass spectrometry. EuPA Open Proteom 11, 23–27. 10.1016/j.euprot.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagel K, Hyung SJ, Ruotolo BT, and Robinson CV (2010). Alternate dissociation pathways identified in charge-reduced protein complex ions. Anal Chem 82, 5363–5372. 10.1021/ac101121r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersson M, and Crews CM (2019). PROteolysis TArgeting Chimeras (PROTACs) - Past, present and future. Drug Discov Today Technol 31, 15–27. 10.1016/j.ddtec.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polasky DA, Dixit SM, Fantin SM, and Ruotolo BT (2019). CIUSuite 2: Next-Generation Software for the Analysis of Gas-Phase Protein Unfolding Data. Anal Chem 91, 3147–3155. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b05762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popa V, Trecroce DA, McAllister RG, and Konermann L (2016). Collision-Induced Dissociation of Electrosprayed Protein Complexes: An All-Atom Molecular Dynamics Model with Mobile Protons. J Phys Chem B 120, 5114–5124. 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b03035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukala TL, Ruotolo BT, Zhou M, Politis A, Stefanescu R, Leary JA, and Robinson CV (2009). Subunit architecture of multiprotein assemblies determined using restraints from gas-phase measurements. Structure 17, 1235–1243. 10.1016/j.str.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy MJ, Winkler S, Hughes SJ, Whitworth C, Galant M, Farnaby W, Rumpel K, and Ciulli A (2019). SPR-Measured Dissociation Kinetics of PROTAC Ternary Complexes Influence Target Degradation Rate. ACS Chem Biol 14, 361–368. 10.1021/acschembio.9b00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruotolo BT, Benesch JL, Sandercock AM, Hyung SJ, and Robinson CV (2008). Ion mobility-mass spectrometry analysis of large protein complexes. Nat Protoc 3, 1139–1152. 10.1038/nprot.2008.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Chaihu L, Tian M, Shao X, Dai R, de Jong RN, Ugurlar D, Gros P, and Heck AJR (2020). Releasing Nonperipheral Subunits from Protein Complexes in the Gas Phase. Anal Chem 92, 15799–15805. 10.1021/acs.analchem.0c02845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Eschweiler J, Cui W, Zhang H, Frieden C, Ruotolo BT, and Gross ML (2019). Native Mass Spectrometry, Ion Mobility, Electron-Capture Dissociation, and Modeling Provide Structural Information for Gas-Phase Apolipoprotein E Oligomers. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 30, 876–885. 10.1007/s13361-019-02148-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JM, and McLuckey SA (2005). Collision-induced dissociation (CID) of peptides and proteins. Methods Enzymol 402, 148–185. 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)02005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Zhang J, Yin S, and Loo JA (2006). Top-down ESI-ECD-FT-ICR mass spectrometry localizes noncovalent protein-ligand binding sites. J Am Chem Soc 128, 14432–14433. 10.1021/ja063197p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Zhou M, Gilbert JD, Wolff JJ, Somogyi Á, Pedder RE, Quintyn RS, Morrison LJ, Easterling ML, Paša-Tolić L, and Wysocki VH (2017). Surface-Induced Dissociation of Protein Complexes in a Hybrid Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometer. Anal Chem 89, 895–901. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zengerle M, Chan KH, and Ciulli A (2015). Selective Small Molecule Induced Degradation of the BET Bromodomain Protein BRD4. ACS Chem Biol 10, 1770–1777. 10.1021/acschembio.5b00216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Cui W, Wen J, Blankenship RE, and Gross ML (2011). Native electrospray and electron-capture dissociation FTICR mass spectrometry for top-down studies of protein assemblies. Anal Chem 83, 5598–5606. 10.1021/ac200695d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhurov KO, Fornelli L, Wodrich MD, Laskay Ü, and Tsybin YO (2013). Principles of electron capture and transfer dissociation mass spectrometry applied to peptide and protein structure analysis. Chem Soc Rev 42, 5014–5030. 10.1039/c3cs35477f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorba A, Nguyen C, Xu Y, Starr J, Borzilleri K, Smith J, Zhu H, Farley KA, Ding W, Schiemer J, et al. (2018). Delineating the role of cooperativity in the design of potent PROTACs for BTK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, E7285–E7292. 10.1073/pnas.1803662115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

This study did not generate any data sets or code.