Abstract

Background and purpose

The spread of COVID-19 has restricted the delivery of standard medical care to surgical patients dramatically. Surgical triage is performed by considering the type of disease, its severity, the urgency for surgery, and the condition of the patient, in addition to the scale of infectious outbreaks in the region. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the number of surgical procedures performed and whether the effects were more prominent during certain periods of widespread infection and in the affected regions.

Methods

We selected 20 of the most common procedures from each surgical field and compared the weekly numbers of each operation performed in 2020 with the respective numbers in 2018 and 2019, as recorded in the National Clinical Database (NCD). The surgical status during the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the relationship between surgical volume and the degree of regional infection were analyzed extensively.

Results

The rate of decline in surgery was at most 10–15%. Although the numbers of most oncological and cardiovascular procedures decreased in 2020, there was no significant change in the numbers of pancreaticoduodenectomy and aortic replacement procedures performed in the same period.

Conclusion

The numbers of most surgical procedures decreased in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic; however, the precise impact of surgical triage on decrease in detection of disease warrants further investigation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00595-021-02406-2.

Keywords: COVID-19, Surgical triage, National clinical database

Introduction

The rapid spread of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which first appeared in Wuhan, China, evolved into a global pandemic, disrupting all aspects of life across the world, including Japan [1, 2]. The number of infected people has increased dramatically since the first case was reported in Japan on January 15, 2020; however, a comprehensive strategy for the diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 is yet to be established. Although approximately 80% of patients who acquire COVID-19 recover, there is a high risk of COVID-19 infection resulting in severe disease or death, especially among elderly people with comorbidities such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, hypertension, cerebrocardiovascular disease, obesity, and people with malignant tumors [3].

Medical resources such as labor, space, and equipment often needed to be reallocated to manage the influx of COVID-19 patients and this restricted the ability to deliver standard medical care to patients with other diseases. However, surgical care should not be interrupted even under such circumstances, as surgeons have multiple responsibilities to continue surgical treatment even in difficult situations such as a pandemic. Nevertheless, surgeons must select which surgical procedures to perform with careful consideration of many factors, ensuring the management of in-hospital surgical systems and preventing nosocomial infections, especially among perioperative patients. Surgical triage should be performed under comprehensive consideration of the type of disease, its severity, the urgency of surgery, and the condition of the patient, as well as the scale of infectious outbreak in the region and the status of medical care provision in the facility [4].

To manage these conditions, the Japan Surgical Society’s “Guidelines for performing surgical triage during the COVID-19 pandemic”, has classified the status of the medical care system into a ‘stable period’ and a ‘restricted period’ [5]. Diseases or indications for surgery have been divided into three levels:

(A) A disease or condition that is nonfatal or does not require urgent medical intervention.

(B) A disease or condition unlikely to be fatal, but is at risk of becoming severe and being potentially fatal.

(C) A disease or condition that may be fatal in a few days or months without any surgical intervention.

If surgical triage is performed with reference to these guidelines, the number of operations should fluctuate and act as an indicator of the impact of COVID-19 infection on surgical treatment. However, given that little is known about the exact number of operations that were cancelled or postponed and which specialties were most affected during this period in Japan, the current survey of major surgical procedures performed in 2020 represents an overview of surgical practices during the COVID-19 pandemic. It will be an important resource for creating a system to allow continuity of surgical treatment in the event of a disaster, such as the outbreak of a new highly transmissible infection.

Method

The members of the novel coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak committee of the Japan Surgical Society selected 20 of the most common surgical procedures performed in each surgical field.

Digestive surgery: gastrectomy (including distal gastrectomy, pylorus-preserving gastrectomy and segmental gastrectomy), low anterior resection of the rectum, hepatectomy of one section or more (excluding left lateral section), pancreatoduodenectomy, appendectomy, and cholecystectomy

Cardiovascular surgery: valve replacement + valve plasty, ascending aorta replacement + aortic arch replacement, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), abdominal aorta replacement (below renal artery), ventricular septal defect closure

General thoracic surgery: lobectomy (+ mediastinal lymph node dissection), resection of a mediastinal tumor

Breast surgery: total mastectomy, breast-conserving surgery, sentinel node biopsy

Endocrine surgery: thyroidectomy, parathyroidectomy

Pediatric surgery (under 16 years of age): inguinal hernia repair, appendectomy

For this study, lobectomy and thoracic aorta replacement refer to pulmonary lobectomy and ascending aorta replacement + aortic arch replacement, respectively.

The primary outcome measure of this study was to identify the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical care, including any decrease in the number of surgeries. This was analyzed by extracting essential data from the National Clinical Database (NCD). The NCD is a nationwide web-based surgical patient registration system, which enables the collection of data on all surgical procedures performed in Japan, in addition to perioperative factors. More than 14,340,000 procedures, accounting for more than 90% of all surgeries performed in Japan during this period, have been registered by approximately 5,000 hospitals [6, 7]. The NCD constructed software for an Internet-based data collection system and data managers in participating hospitals were responsible for forwarding their data to the NCD office [7]. Using the NCD to investigate all surgeries performed in 2020 is an ideal means to evaluate this extraordinary change in Japanese surgical practices caused by the spread of COVID-19. The total number and change in numbers of each procedure performed in 2020 were analyzed weekly (STATA 17, STATA Corp., TX, USA) and compared with the status in 2018 and 2019.

Some concerns were raised about the possibility of a stronger impact on surgery during certain periods of widespread infection or in areas with high numbers of infected people. The following two settings were used to clarify such speculation.

Period of COVID-19 pandemic

The first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan were recognized as periods, or phases, when the spread of infection was remarkable. There is no fixed definition for this specific period in the pandemic; therefore, we determined these periods for our study based on changes in the number of infected people nationwide and the objective public view.

The first pandemic wave was stipulated as being from February 26 to May 26, 2020, because the government decided on the basic policy for infection control on February 25 [8] and the state of emergency was lifted nationwide on May 25 [9]. The second wave was from July 1 to September 29, 2020, as the government called for thorough countermeasures to address the increase in the number of infected people on June 30 [10]. The dramatic increase in the number of newly infected people as of September 30 was also the focus of discussion during the Tokyo Metropolitan Coronavirus Infection Monitoring Conference [11].

Classification of prefectures according to the degree of infection

The cumulative number of infected people per population of prefectures (as of the end of 2020) [12] was used as an index of the degree of infection. Based on this value, the degree of infection in prefectures was classified into three groups: high, medium and low.

High group: Aichi, Chiba, Fukuoka, Hokkaido, Hyogo, Kanagawa, Kyoto, Nara, Okinawa, Osaka, Saitama, and Tokyo (12 prefectures)

Medium group: Fukushima, Gifu, Gunma, Hiroshima, Ibaragi, Ishikawa, Kagoshima, Kochi, Kumamoto, Mie, Miyagi, Miyazaki, Nagano, Oita, Okayama, Saga, Shiga, Shizuoka, Tochigi, Toyama, Yamanashi, and Wakayama (22 prefectures)

Low group: Akita, Aomori, Ehime, Fukui, Iwate, Kagawa, Nagasaki, Niigata, Shimane, Tokushima, Tottori, Yamagata and Yamaguchi (13 prefectures)

We compared the total number of each of the 20 surgical procedures performed in 2019 and 2020 and investigated whether there was a significant decrease in the number of these operations performed in the first and second wave periods in 2020, compared with the same period in 2019.

We also analyzed whether the numbers decreased more significantly in prefectures with higher infection levels throughout the year or during the first and second waves compared with other regions. The two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (two-way RMANOVA) was used for statistical analysis. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

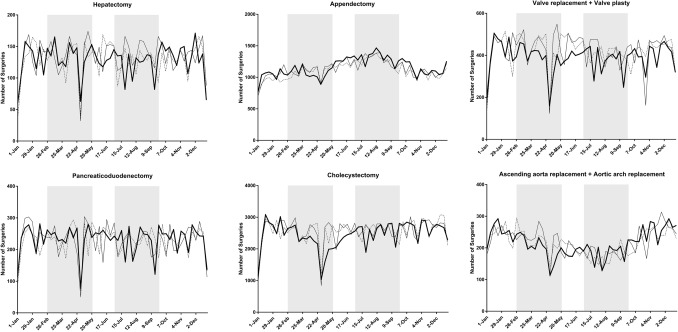

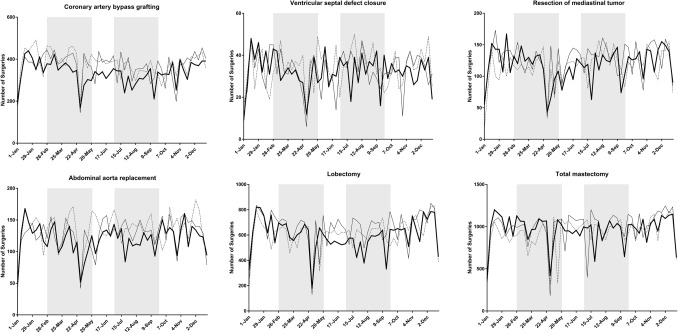

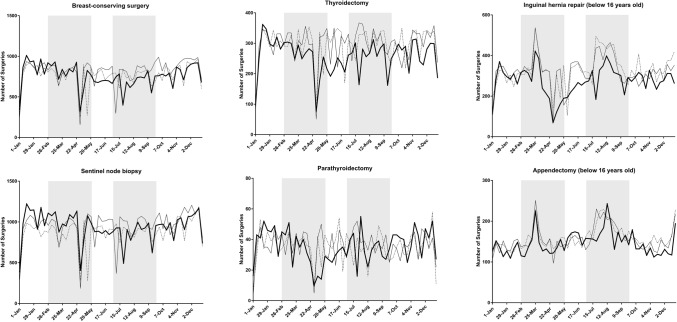

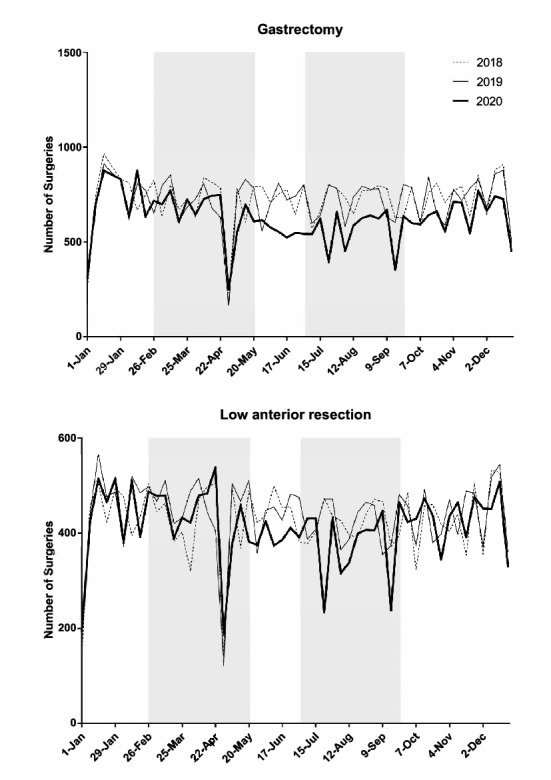

Table 1 summarizes the status of surgery for the 20 procedures. A total of 530,701 operations were scheduled between January 1 and December 31, 2020, which corresponded to 95.0% and 97.5% of the total number of surgeries performed in 2018 and 2019, respectively. Cases of unknown age and gender were excluded from the analysis. Figure 1 shows the weekly number of each of the 20 procedures in 2020 as line graphs and the status in 2018 and 2019 for comparison.

Table 1.

Number of operations performed for each procedure in 2020 vs. 2018 and 2019

| Procedure | Number of operations (2018) | Number of operations (2019) | Number of operations (2020) | vs. 2018 | vs. 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrectomy | 37,733 | 37,173 | 32,723 | 86.7% | 88.0% |

| Low anterior resection | 22,099 | 22,763 | 21,506 | 97.3% | 94.5% |

| Hepatectomy | 6734 | 7019 | 6707 | 99.6% | 95.6% |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 11,774 | 11,963 | 12,074 | 102.5% | 100.9% |

| Appendectomy | 57,742 | 59,152 | 60,094 | 104.1% | 101.6% |

| Cholecystectomy | 132,766 | 133,441 | 127,621 | 96.1% | 95.6% |

| Valve replacement + valve plasty | 21,938 | 21,887 | 20,355 | 92.8% | 93.0% |

| Ascending aorta replacement + aortic arch replacement | 11,170 | 11,375 | 11,186 | 100.1% | 98.3% |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 19,704 | 19,109 | 17,452 | 88.6% | 91.3% |

| Abdominal aorta replacement | 6985 | 6624 | 6249 | 89.5% | 94.3% |

| Ventricular septal defect closure | 1791 | 1698 | 1681 | 93.9% | 99.0% |

| Lobectomy | 31,677 | 33,815 | 31,174 | 98.4% | 92.2% |

| Resection of mediastinal tumor | 6011 | 6575 | 6152 | 102.3% | 93.6% |

| Total mastectomy | 48,276 | 51,435 | 50,283 | 104.2% | 97.8% |

| Breast-conserving surgery | 40,003 | 42,475 | 39,495 | 98.7% | 93.0% |

| Sentinel node biopsy | 45,501 | 49,728 | 48,848 | 107.4% | 98.2% |

| Thyroidectomy | 15,262 | 15,405 | 13,449 | 88.1% | 87.3% |

| Parathyroidectomy | 1824 | 1879 | 1827 | 100.2% | 97.2% |

| Inguinal hernia repair (under age 16) | 17,171 | 16,736 | 14,232 | 82.9% | 85.0% |

| Appendectomy (under age 16) | 8269 | 8150 | 7593 | 91.8% | 93.2% |

| Total | 544,430 | 558,402 | 530,701 | 97.5% | 95.0% |

Fig. 1.

Trends in the weekly volume of each procedure (2018–2020) Shaded areas show the periods of the first and second pandemic waves (February 26-May 26, and July 1-September 29, respectively)

Table 2 compares the total numbers of each of the 20 surgical procedures during the first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic and outlines the differences in surgical situations among the three prefectural groups according to the degree of infection. Detailed results are described below.

Table 2.

Number of surgeries performed in the pandemic period and regional infection level classifications

| Procedure | Period | Infection level | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | vs 2018 | vs 2019 | p value vs 2019 | p value high vs medium + low |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrectomy | 1st pandemic period | High | 5176 | 5166 | 4676 | 90.3% | 90.5% | ||

| Medium | 2795 | 2597 | 2586 | 92.5% | 99.6% | ||||

| Low | 1177 | 1215 | 1223 | 103.9% | 100.7% | ||||

| Subtotal | 9148 | 8978 | 8485 | 92.8% | 94.5% | 0.084 | 0.087 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 5222 | 5255 | 4018 | 76.9% | 76.5% | |||

| Medium | 2848 | 2836 | 2316 | 81.3% | 81.7% | ||||

| Low | 1321 | 1244 | 1012 | 76.6% | 81.4% | ||||

| Subtotal | 9391 | 9335 | 7346 | 78.2% | 78.7% | < 0.001 | 0.122 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 37,733 | 37,173 | 32,723 | 86.7% | 88.0% | < 0.001 | 0.046 | |

| Low anterior resection | 1st pandemic period | High | 3193 | 3404 | 3255 | 101.9% | 95.6% | ||

| Medium | 1659 | 1661 | 1669 | 100.6% | 100.5% | ||||

| Low | 630 | 715 | 668 | 106.0% | 93.4% | ||||

| Subtotal | 5482 | 5780 | 5592 | 102.0% | 96.7% | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 3152 | 3341 | 2941 | 93.3% | 88.0% | |||

| Medium | 1617 | 1558 | 1428 | 88.3% | 91.7% | ||||

| Low | 662 | 643 | 567 | 85.6% | 88.2% | ||||

| Subtotal | 5431 | 5542 | 4936 | 90.9% | 89.1% | 0.090 | 0.003 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 22,099 | 22,763 | 21,506 | 97.3% | 94.5% | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Hepatectomy | 1st pandemic period | High | 999 | 1017 | 978 | 97.9% | 96.2% | ||

| Medium | 494 | 544 | 544 | 110.1% | 100.0% | ||||

| Low | 201 | 184 | 213 | 106.0% | 115.8% | ||||

| Subtotal | 1694 | 1745 | 1735 | 102.4% | 99.4% | 0.886 | 0.333 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 970 | 1083 | 950 | 97.9% | 87.7% | |||

| Medium | 486 | 568 | 474 | 97.5% | 83.5% | ||||

| Low | 171 | 169 | 182 | 106.4% | 107.7% | ||||

| Subtotal | 1627 | 1820 | 1606 | 98.7% | 88.2% | 0.018 | 0.543 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 6734 | 7019 | 6707 | 99.6% | 95.6% | 0.034 | 0.520 | |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 1st pandemic period | High | 1724 | 1758 | 1783 | 103.4% | 101.4% | ||

| Medium | 897 | 871 | 919 | 102.5% | 105.5% | ||||

| Low | 349 | 361 | 342 | 98.0% | 94.7% | ||||

| Subtotal | 2970 | 2990 | 3044 | 102.5% | 101.8% | 0.612 | 0.970 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 1685 | 1791 | 1748 | 103.7% | 97.6% | |||

| Medium | 892 | 801 | 842 | 94.4% | 105.1% | ||||

| Low | 341 | 347 | 339 | 99.4% | 97.7% | ||||

| Subtotal | 2918 | 2939 | 2929 | 100.4% | 99.7% | 0.935 | 0.536 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 11,774 | 11,963 | 12,074 | 102.5% | 100.9% | 0.627 | 0.429 | |

| Appendectomy | 1st pandemic period | High | 8609 | 8753 | 8268 | 96.0% | 94.5% | ||

| Medium | 3958 | 4113 | 4081 | 103.1% | 99.2% | ||||

| Low | 1556 | 1538 | 1474 | 94.7% | 95.8% | ||||

| Subtotal | 14,123 | 14,404 | 13,823 | 97.9% | 96.0% | 0.038 | 0.155 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 9854 | 9916 | 10,325 | 104.8% | 104.1% | |||

| Medium | 4704 | 4874 | 4920 | 104.6% | 100.9% | ||||

| Low | 1828 | 1694 | 1801 | 98.5% | 106.3% | ||||

| Subtotal | 16,386 | 16,484 | 17,046 | 104.0% | 103.4% | 0.037 | 0.326 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 57,742 | 59,152 | 60,094 | 104.1% | 101.6% | 0.080 | 0.808 | |

| Cholecystectomy | 1st pandemic period | High | 17,991 | 18,290 | 15,688 | 87.2% | 85.8% | ||

| Medium | 9705 | 9984 | 9012 | 92.9% | 90.3% | ||||

| Low | 4036 | 3971 | 3699 | 91.7% | 93.2% | ||||

| Subtotal | 31,732 | 32,245 | 28,399 | 89.5% | 88.1% | 0.001 | 0.201 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 18,806 | 19,373 | 18,778 | 99.9% | 96.9% | |||

| Medium | 10,381 | 10,526 | 10,276 | 99.0% | 97.6% | ||||

| Low | 4223 | 4029 | 3975 | 94.1% | 98.7% | ||||

| Subtotal | 33,410 | 33,928 | 33,029 | 98.9% | 97.4% | 0.300 | 0.734 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 132,766 | 133,441 | 127,621 | 96.1% | 95.6% | 0.001 | 0.337 | |

| Valve replacement + valve plasty | 1st pandemic period | High | 3454 | 3547 | 3019 | 87.4% | 85.1% | ||

| Medium | 1553 | 1557 | 1418 | 91.3% | 91.1% | ||||

| Low | 581 | 548 | 501 | 86.2% | 91.4% | ||||

| Subtotal | 5588 | 5652 | 4938 | 88.4% | 87.4% | 0.001 | 0.066 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 3353 | 3370 | 3085 | 92.0% | 91.5% | |||

| Medium | 1487 | 1496 | 1315 | 88.4% | 87.9% | ||||

| Low | 525 | 505 | 532 | 101.3% | 105.3% | ||||

| Subtotal | 5365 | 5371 | 4932 | 91.9% | 91.8% | 0.068 | 0.573 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 21,938 | 21,887 | 20,355 | 92.8% | 93.0% | < 0.001 | 0.047 | |

| Ascending aorta replacement + aortic arch replacement | 1st pandemic period | High | 1859 | 1833 | 1633 | 87.8% | 89.1% | ||

| Medium | 747 | 786 | 733 | 98.1% | 93.3% | ||||

| Low | 283 | 298 | 234 | 82.7% | 78.5% | ||||

| Subtotal | 2889 | 2917 | 2600 | 90.0% | 89.1% | 0.008 | 0.453 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 1468 | 1532 | 1538 | 104.8% | 100.4% | |||

| Medium | 597 | 616 | 663 | 111.1% | 107.6% | ||||

| Low | 213 | 218 | 196 | 92.0% | 89.9% | ||||

| Subtotal | 2278 | 2366 | 2397 | 105.2% | 101.3% | 0.745 | 0.842 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 11,170 | 11,375 | 11,186 | 100.1% | 98.3% | 0.391 | 0.595 | |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 1st pandemic period | High | 3253 | 3145 | 2738 | 84.2% | 87.1% | ||

| Medium | 1449 | 1362 | 1206 | 83.2% | 88.5% | ||||

| Low | 529 | 495 | 422 | 79.8% | 85.3% | ||||

| Subtotal | 5231 | 5002 | 4366 | 83.5% | 87.3% | < 0.001 | 0.178 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 2924 | 2919 | 2524 | 86.3% | 86.5% | |||

| Medium | 1252 | 1262 | 1043 | 83.3% | 82.6% | ||||

| Low | 420 | 435 | 415 | 98.8% | 95.4% | ||||

| Subtotal | 4596 | 4616 | 3982 | 86.6% | 86.3% | < 0.001 | 0.311 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 19,704 | 19,109 | 17,452 | 88.6% | 91.3% | < 0.001 | 0.196 | |

| Abdominal aorta replacement | 1st pandemic period | High | 943 | 847 | 759 | 80.5% | 89.6% | ||

| Medium | 577 | 539 | 535 | 92.7% | 99.3% | ||||

| Low | 166 | 153 | 141 | 84.9% | 92.2% | ||||

| Subtotal | 1686 | 1539 | 1435 | 85.1% | 93.2% | 0.133 | 0.293 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 1022 | 979 | 868 | 84.9% | 88.7% | |||

| Medium | 601 | 594 | 482 | 80.2% | 81.1% | ||||

| Low | 178 | 156 | 180 | 101.1% | 115.4% | ||||

| Subtotal | 1801 | 1729 | 1530 | 85.0% | 88.5% | 0.006 | 0.730 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 6985 | 6624 | 6249 | 89.5% | 94.3% | 0.003 | 0.892 | |

| Ventricular septal defect closure | 1st pandemic period | High | 282 | 253 | 252 | 89.4% | 99.6% | ||

| Medium | 121 | 123 | 116 | 95.9% | 94.3% | ||||

| Low | 45 | 41 | 32 | 71.1% | 78.0% | ||||

| Subtotal | 448 | 417 | 400 | 89.3% | 95.9% | 0.504 | 0.555 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 303 | 306 | 271 | 89.4% | 88.6% | |||

| Medium | 118 | 119 | 132 | 111.9% | 110.9% | ||||

| Low | 46 | 27 | 34 | 73.9% | 125.9% | ||||

| Subtotal | 467 | 452 | 437 | 93.6% | 96.7% | 0.673 | 0.130 | ||

| yearly | Total | 1791 | 1698 | 1681 | 93.9% | 99.0% | 0.774 | 0.353 | |

| Lobectomy | 1st pandemic period | High | 4390 | 4697 | 4503 | 102.6% | 95.9% | ||

| Medium | 2049 | 2235 | 2214 | 108.1% | 99.1% | ||||

| Low | 867 | 955 | 978 | 112.8% | 102.4% | ||||

| Subtotal | 7306 | 7887 | 7695 | 105.3% | 97.6% | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 4600 | 4998 | 4173 | 90.7% | 83.5% | |||

| Medium | 2363 | 2476 | 1914 | 81.0% | 77.3% | ||||

| Low | 973 | 1003 | 895 | 92.0% | 89.2% | ||||

| Subtotal | 7936 | 8477 | 6982 | 88.0% | 82.4% | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| yearly | Total | 31,677 | 33,815 | 31,174 | 98.4% | 92.2% | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Resection of mediastinal tumor | 1st pandemic period | High | 839 | 956 | 872 | 103.9% | 91.2% | ||

| Medium | 412 | 419 | 443 | 107.5% | 105.7% | ||||

| Low | 157 | 147 | 147 | 93.6% | 100.0% | ||||

| Subtotal | 1408 | 1522 | 1462 | 103.8% | 96.1% | 0.528 | 0.260 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 984 | 1055 | 919 | 93.4% | 87.1% | |||

| Medium | 482 | 471 | 430 | 89.2% | 91.3% | ||||

| Low | 160 | 183 | 156 | 97.5% | 85.2% | ||||

| Subtotal | 1626 | 1709 | 1505 | 92.6% | 88.1% | 0.014 | 0.386 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 6011 | 6575 | 6152 | 102.3% | 93.6% | 0.007 | 0.109 | |

| Total mastectomy | 1st pandemic period | High | 6679 | 7415 | 7609 | 113.9% | 102.6% | ||

| Medium | 3061 | 3555 | 3582 | 117.0% | 100.8% | ||||

| Low | 1123 | 1288 | 1420 | 126.4% | 110.2% | ||||

| Subtotal | 10,863 | 12,258 | 12,611 | 116.1% | 102.9% | 0.270 | 0.912 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 7581 | 7899 | 7252 | 95.7% | 91.8% | |||

| Medium | 3688 | 3648 | 3570 | 96.8% | 97.9% | ||||

| Low | 1375 | 1389 | 1363 | 99.1% | 98.1% | ||||

| Subtotal | 12,644 | 12,936 | 12,185 | 96.4% | 94.2% | 0.245 | 0.398 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 48,276 | 51,435 | 50,283 | 104.2% | 97.8% | 0.195 | 0.325 | |

| Breast-conserving surgery | 1st pandemic period | High | 5766 | 6233 | 6191 | 107.4% | 99.3% | ||

| Medium | 2708 | 2874 | 2863 | 105.7% | 99.6% | ||||

| Low | 1024 | 1064 | 1078 | 105.3% | 101.3% | ||||

| Subtotal | 9498 | 10,171 | 10,132 | 106.7% | 99.6% | 0.903 | 0.888 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 5940 | 6313 | 5428 | 91.4% | 86.0% | |||

| Medium | 2797 | 2916 | 2492 | 89.1% | 85.5% | ||||

| Low | 1053 | 1041 | 982 | 93.3% | 94.3% | ||||

| Subtotal | 9790 | 10,270 | 8902 | 90.9% | 86.7% | 0.017 | 0.457 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 40,003 | 42,475 | 39,495 | 98.7% | 93.0% | < 0.001 | 0.259 | |

| Sentinel node biopsy | 1st pandemic period | High | 6675 | 7481 | 7922 | 118.7% | 105.9% | ||

| Medium | 2905 | 3325 | 3478 | 119.7% | 104.6% | ||||

| Low | 930 | 1091 | 1234 | 132.7% | 113.1% | ||||

| Subtotal | 10,510 | 11,897 | 12,634 | 120.2% | 106.2% | 0.034 | 0.663 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 7270 | 7821 | 7050 | 97.0% | 90.1% | |||

| Medium | 3142 | 3290 | 3034 | 96.6% | 92.2% | ||||

| Low | 1034 | 1058 | 1102 | 106.6% | 104.2% | ||||

| Subtotal | 11,446 | 12,169 | 11,186 | 97.7% | 91.9% | 0.142 | 0.396 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 45,501 | 49,728 | 48,848 | 107.4% | 98.2% | 0.339 | 0.336 | |

| Thyroidectomy | 1st pandemic period | High | 2267 | 2311 | 1887 | 83.2% | 81.7% | ||

| Medium | 1084 | 1192 | 1087 | 100.3% | 91.2% | ||||

| Low | 343 | 299 | 271 | 79.0% | 90.6% | ||||

| Subtotal | 3694 | 3802 | 3245 | 87.8% | 85.3% | < 0.001 | 0.010 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 2353 | 2481 | 1911 | 81.2% | 77.0% | |||

| Medium | 1218 | 1228 | 1170 | 96.1% | 95.3% | ||||

| Low | 347 | 318 | 281 | 81.0% | 88.4% | ||||

| Subtotal | 3918 | 4027 | 3362 | 85.8% | 83.5% | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 15,262 | 15,405 | 13,449 | 88.1% | 87.3% | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Parathyroidectomy | 1st pandemic period | High | 270 | 273 | 222 | 82.2% | 81.3% | ||

| Medium | 144 | 154 | 143 | 99.3% | 92.9% | ||||

| Low | 46 | 39 | 38 | 82.6% | 97.4% | ||||

| Subtotal | 460 | 466 | 403 | 87.6% | 86.5% | 0.095 | 0.292 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 272 | 301 | 262 | 96.3% | 87.0% | |||

| Medium | 125 | 158 | 145 | 116.0% | 91.8% | ||||

| Low | 45 | 29 | 30 | 66.7% | 103.4% | ||||

| Subtotal | 442 | 488 | 437 | 98.9% | 89.5% | 0.204 | 0.496 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 1824 | 1879 | 1827 | 100.2% | 97.2% | 0.477 | 0.241 | |

| Inguinal hernia repair (under age 16) | 1st pandemic period | High | 2426 | 2409 | 1801 | 74.2% | 74.8% | ||

| Medium | 1307 | 1269 | 1059 | 81.0% | 83.5% | ||||

| Low | 430 | 448 | 361 | 84.0% | 80.6% | ||||

| Subtotal | 4163 | 4126 | 3221 | 77.4% | 78.1% | < 0.001 | 0.145 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 2818 | 2718 | 2252 | 79.9% | 82.9% | |||

| Medium | 1494 | 1405 | 1225 | 82.0% | 87.2% | ||||

| Low | 616 | 512 | 441 | 71.6% | 86.1% | ||||

| Subtotal | 4928 | 4635 | 3918 | 79.5% | 84.5% | 0.002 | 0.301 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 17,171 | 16,736 | 14,232 | 82.9% | 85.0% | < 0.001 | 0.045 | |

| Appendectomy (under age 16) | 1st pandemic period | High | 1192 | 1155 | 1066 | 89.4% | 92.3% | ||

| Medium | 602 | 582 | 557 | 92.5% | 95.7% | ||||

| Low | 223 | 243 | 187 | 83.9% | 77.0% | ||||

| Subtotal | 2017 | 1980 | 1810 | 89.7% | 91.4% | 0.009 | 0.895 | ||

| 2nd pandemic period | High | 1391 | 1379 | 1291 | 92.8% | 93.6% | |||

| Medium | 732 | 719 | 614 | 83.9% | 85.4% | ||||

| Low | 295 | 261 | 270 | 91.5% | 103.4% | 0.936 | |||

| Subtotal | 2418 | 2359 | 2175 | 90.0% | 92.2% | 0.076 | 0.936 | ||

| Yearly | Total | 8269 | 8150 | 7593 | 91.8% | 93.2% | < 0.001 | 0.679 |

Comparison between 2019 and 2020

Digestive surgery

We did not identify a significant change in the number of pancreaticoduodenectomies or appendectomies from 2019; however, the numbers of gastrectomy, low anterior resection of the rectum, hepatectomy, and cholecystectomy, decreased significantly. Among these, the rate of decline in gastrectomies and low anterior resections of the rectum was more prominent in prefectures with high infection levels than in those with moderate or low infection levels. (p < 0.001).

Cardiovascular surgery

The numbers of thoracic aorta replacement and ventricular septal defect closure procedures did not change significantly from 2019, but the numbers of other procedures, such as valve replacement + valve plasty, CABG and abdominal aorta replacement, decreased significantly (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, p = 0.003, respectively). The rate of decline of CABG and abdominal aorta replacements did not differ by region.

General thoracic surgery

The numbers of lobectomy and resection of mediastinal tumors in 2020 decreased from the previous year (p < 0.001, both) and the rate of decrease in lobectomies was more significant in prefectures with high infection levels (p < 0.001).

Breast surgery and endocrine surgery

The operative status for total mastectomy and parathyroidectomy was not significantly different from that in 2019. The number of breast-conserving surgeries and thyroidectomies was significantly lower in 2020 (p < 0.001, both) and the rate of decrease for the latter was more prominent in prefectures with high infection levels.

Pediatric surgery

The numbers of inguinal hernia repairs and appendectomies were significantly lower in 2020. The rate of decrease in inguinal hernia repairs performed was more pronounced in prefectures with high infection levels, but the rate of decrease in the numbers of appendectomies performed did not differ by region.

Period of COVID-19 pandemic

There was a marked decrease in the numbers of low anterior resection of the rectum, lobectomy of the lung (Fig. 2) and thyroidectomy in prefectures with high rates of infection compared with the numbers in other areas during the first and second waves of the pandemic in 2020. On the other hand, no such regional differences were evident for pancreaticoduodenectomy, appendectomy, thoracic aorta replacement (Fig. 2), VSD closure, total mastectomy, or parathyroidectomy. (Supplemental Fig. 1 shows representative graphs for the other 15 procedures).

Fig. 2.

Weekly volume of five procedures according to the three groups (high, medium, low) of regional infection level. Shaded areas show the periods of the first and second pandemic waves (February 26-May 26, and July 1-September 29, respectively)

Discussion

We conducted this study to establish the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the number of surgical procedures performed in Japan during this period by comparing the total number of operations for 20 representative surgical procedures in 2020 with that of those in the 2 pre-pandemic years. We also evaluated whether the effects of COVID-19 were more serious during certain periods and in regions where the infection was more widespread.

Although the numbers of most operative procedures decreased in 2020, we were able to identify differences in the rate of decline in the numbers for each procedure and evaluate the impact of the scale of infection on surgical treatment. Since the purpose of this study was to provide an overview of surgical procedures in 2020, we did not investigate details such as preoperative disease status, stage of malignancy, or postoperative course. In addition to surgical triage, the decrease in the numbers of surgeries performed may be attributable to multiple factors, such as fewer new patients and postponement of examinations, which will also be the subject of our next study.

Ultimately, surgery should be performed as usual and without delay for symptomatic advanced cancer, although non-aggressive cancers differentiated by improved diagnostic methods may be postponed until the pandemic subsides [4, 13]. Moreover, for high-risk patients with multiple comorbidities, postponing surgery may be necessary to avoid the risk of postoperative infection.

According to a large-scale surgical triage survey of 359 hospitals in 71 countries, including Japan, 73% (approximately 1.4 million) of operations, including upper and lower gastrointestinal, hepatobiliary, urological, head and neck, gynecological, plastic, orthopedic, and obstetric operations, which were scheduled to take place over a 12-week period, from late March 2020, were cancelled or postponed. Among these, approximately 98,000 were procedures for cancer (30%) and 1,253,000 were procedures for benign diseases (84%) [14]. An international, prospective, cohort study including 20,006 patients from 466 hospitals in 61 countries was conducted to reveal the effect of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns on elective cancer surgery. Of eligible patients awaiting surgery, 0.6% had their surgery postponed during light restrictions, 5.5% in moderate lockdowns, and 15.0% in full lockdowns [15]. We want to entrust further analysis of clinical factors, disease severity, stage, and histological type of malignant tumors and postoperative course to the research in each specialized surgical field in the near future.

Although our study was limited to typical surgical procedures, the results showed that the rate of decline for surgery was no more than 10–15%. It is possible that since Japan had far fewer patients with COVID-19 infection than most Western countries, surgeons could schedule high-priority operations even during the pandemic when the number of COVID-19 cases was growing. Okuno used the Diagnosis Procedure Combination (DPC) data from the Quality Indicator/Improvement Project (QIP) database to compare surgical volume between the two periods of July 2018–March 2020 and April–June 2020. That analysis revealed that the decline in oncological procedures for gastrointestinal, hepato-pancreato-biliary, lung, breast, and genitourinary cancer was not significant, even though the numbers were lower than for the same period in the previous year [16]. Miyawaki compared the number of surgeries across specialties in weeks 2 to 9 versus weeks 10 to 17 in 2020 using the de-identified hospital administrative database from Japanese acute-care hospitals. The rates of decline in cardiovascular surgery and gastrointestinal or hepato-pancreato-biliary system were 9.9% and 9.5%, respectively; however, the number of breast operations did not decrease significantly [17]. There are variations in the trends of the affected number of surgical procedures based on the region and time period [18]. Our study shows that the numbers of low anterior resections of the rectum, CABG, lung lobectomies, thyroidectomies, and inguinal hernia repairs were significantly lower during the first and second COVID-19 pandemic waves. There are various reasons for each disease, such as surgical triage, fewer new patients, and implementation of alternative treatments.

Patients with potentially curable pancreatic carcinoma, pancreatic cystic lesions with confirmed high-grade dysplasia, duodenal cancer, ampullary cancer, as well as curable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and cholangiocarcinoma should undergo surgical resection even during a pandemic [19]. Our results showed that the number of pancreaticoduodenectomies did not decline in 2020, in accordance with consensus statements supported by seven international pancreatic associations [20]. However, other surgical procedures for gastric, colon, liver, lung, and breast cancers, decreased significantly. Another possible cause, along with the impact of triage, may be the 30% decrease in the number of people being screened for cancer in Japan in 2020 [21]. For hepatic malignancies, such as HCC, treating practitioners may select alternative procedures, including radiofrequency ablation and transarterial chemoembolization as locoregional therapies, and molecular targeting drugs for the advanced disease instead of resection for some patients [22].

During the COVID-19 pandemic era, opportunities for cancer screening by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGI) or colonoscopy may have decreased because it is an aerosol-generating procedure [23]. In fact, it was reported that the total volume of endoscopic procedures decreased by 44% during this time [24]. The decline in the number of gastrectomies or anterior resections of the rectum may be related to the decrease in these endoscopic screening procedures.

However, early cancer that is left unscreened might be detected as advanced cancer in the future. Further detailed studies for each cancer could help to verify whether there is a stage shift in surgical cases in the next few years. The significant decrease in the number of cholecystectomies in the present study is in line with an international survey including 14 countries [25], where the majority (72%) of hepato-pancreato-biliary surgeons reported an “alarming decrease” in the number of cholecystectomies during the pandemic. An increase in non-surgical treatment for acute cholecystitis was also reported by multicenter studies from the U.K. and Spain [26, 27], although a multisocietary position statement concluded that laparoscopic cholecystectomy remains the treatment of choice for acute cholecystitis even during the COVID-19 pandemic [28]. Whether the choice of non-surgical treatment for complicated gallstone disease negatively impacted the outcomes of patients warrants further investigation.

Cardiovascular surgery frequently requires transfer of the patient to an intensive care unit and ventilatory support in the postoperative period. However, if there are many patients with respiratory failure caused by COVID-19 pneumonia in the same region, the resources related to intensive care must be reallocated and there may be situations where surgery is limited to life-threatening emergencies. In the United States, there was a 53% reduction in adult cardiac surgeries nationwide during the early half of 2020 compared with 2019, with a 65% decrease in elective surgical cases and a 40% decrease even in non-elective cases [29]. Our results showed that the number of aortic surgeries was the same as in pre-pandemic years because the urgent intervention was required. A global survey of cardiac surgery centers was conducted among the 61 participating centers of the Randomization of Single vs Multiple Arterial Grafts (ROMA) trial, 60 of which responded: 7 from Asia, 2 from Australia, 31 from Europe, 16 from North America, and 4 from South America. The Survey revealed a greater than 50% reduction in ICU bed availability for cardiac surgery and a median reduction in cardiac surgery case volume of 50% to 75% [30].

The number of CABG procedures decreased significantly in 2020, but this could be due to a decrease in the number of new patients or the possibility that catheter-based treatment was performed instead of surgery. The rate of total mastectomies for breast cancer decreased by only about 6% at the time of the second wave, but there was a 13% reduction in breast-conserving surgery. Possible reasons for this include the avoidance of postoperative radiotherapy during the pandemic, or fewer new patients being referred for surgery due to refrained hospital visits. The number of thyroidectomies also decreased in 2020, especially in prefectures with high infection levels, probably because elective surgeries were reserved for patients with very-low risk differentiated thyroid carcinoma or indeterminate thyroid nodules [31].

Most appendectomies are emergency procedures; hence, the numbers of appendectomies in 2020 and 2019 were similar. The number of appendectomies in children decreased, probably due to triage or selection of conservative treatment. Our speculation is supported by a report from a tertiary hospital in New York State, the epicenter of the pandemic in the U.S., where it expanded inclusion criteria for non-operative management of acute appendicitis to reduce operating room utilization [32]. It is noteworthy that multiple publications have described increased incidences of complicated appendicitis during the outbreak [33, 34]. A recent cross-sectional retrospective study based on the Pediatric Health Information System in the U.S. collected data for all patients diagnosed with appendicitis from 52 children’s hospitals between 2017 and 2020 (n = 19,431). That study concluded that the increased proportion of complicated appendicitis presentations by 4.4% (from 46.5% to 50.9%) during the COVID-19 pandemic was driven by a decrease in uncomplicated appendicitis [35]. Whether the difference in presentation and management of pediatric appendicitis has resulted in inferior clinical outcomes is subject to further investigation. It will be necessary to investigate the number of operations postponed or canceled. It is also an important issue to proceed with a fact-finding survey on how many patients were disadvantaged by delayed surgery or by receiving alternative treatment.

It is known that perioperative infection is highly likely to cause severe disease. An analysis of 1128 patients (94 with preoperative infection) who were confirmed to be positive for novel coronavirus in the perioperative period revealed a very high 30-day postoperative mortality rate of 23.8% (268 patients), with 81.7% of these patients dying of pulmonary complications [36]. Moreover, 15 (44%) of the 34 patients with confirmed infection required ICU management, with a postoperative mortality rate of 20.5% [37]. Osorio J, et al. also reported that COVID-19 positive patients who underwent emergency general and gastrointestinal surgery during the pandemic had more complications and a higher likelihood of failure rescue than COVID-19 negative patients [38].

It should be noted that the rate of asymptomatic patients diagnosed as positive for infection by PCR testing was reported to range from 6.3% to 91.7% [39]; therefore, asymptomatic infected patients cannot be screened by examination alone, which may lead to serious postoperative complications and consequent nosocomial infections. It is necessary to verify whether the status of postoperative complications in surgical patients differs from that in previous years and to identify complications strongly related to COVID-19 infection.

Since May 2020, the cost of preoperative PCR-based screening for infection has been covered by insurance [40] and is expected to contribute to the recovery of surgical volumes. According to a questionnaire survey conducted by the Japan Surgical Society, 41.7% of all facilities performed PCR testing on patients scheduled for operations, and the implementation of this increased from 23.8% in April 2020 to 54.4% in December 2020 [41]. In the future, it will be necessary to flexibly update surgical treatment algorithms in view of the generalization of preoperative PCR testing and the increased vaccination status of the general population.

In conclusion, this real-world data analysis of surgeries based on NCD data could provide an objective picture of the status of surgical treatment under COVID-19 infection. Although a decrease in the numbers of each surgical procedure during the COVID-19 pandemic is evident, more detailed studies are needed to demonstrate the difference in management according to the severity of disease and the condition of the patient. There are multiple causes for the decline in the number of surgeries, including triage, fewer new patients, and postponement of examinations. An evaluation of the impact of these factors should be performed as the next step of the analysis. We hope that the findings of our study will contribute to even better infection control, strengthen the intensive care system, and secure medical resources to enable a sustainable medical supply system in the event of a pandemic.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 Weekly volume of 15 procedures according to the three groups (high, medium, low) of regional infection level. Shaded areas show the periods of the first and second pandemic waves (February 26-May 26, and July 1-September 29, respectively) (PDF 7242 KB)

Acknowledgements

We thank Associate Professor Takako Kojima, Department of International Medical Communications, Tokyo Medical University for reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by MHLW Special Research Program Grant Number JPMH20CA2046.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

We have no conflicts of interest to report. Hiroyuki Yamamoto, Urara Isozumi, and Hiroaki Miyata are affiliated with the Department of Healthcare Quality Assessment at the University of Tokyo. The department is a social collaboration department supported by grants from National Clinical Database, Johnson & Johnson K.K., and Nipro Co.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/newpage_08906.html. (in Japanese). Accessed 6 Aug 2021.

- 2.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000668291.pdf. (in Japanese).

- 4.Mori M, Ikeda N, Taketomi A, Asahi Y, Takesue Y, Orimo T, et al. COVID-19: clinical issues from the Japan surgical society. Surg Today. 2020;50:794–808. doi: 10.1007/s00595-020-02047-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Japan Surgical Society. http://www.jssoc.or.jp/aboutus/coronavirus/info20200402.html. (in Japanese).

- 6.Miyata H, Gotoh M, Hashimoto H, Motomura N, Murakami A, Tomotaki A, et al. Challenges and prospects of a clinical database linked to the board certification system. Surg Today. 2014;44:1991–1999. doi: 10.1007/s00595-013-0802-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikeda N, Endo S, Fukuchi E, Nakajima J, Yokoi K, Chida M, et al. Current status of surgery for clinical stage IA lung cancer in Japan: analysis of the national clinical database. Surg Today. 2020;50:1644–1651. doi: 10.1007/s00595-020-02063-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/000599698.pdf. (in Japanese). Accessed 6 Aug 2021.

- 9.Cabinet Secretariat. https://corona.go.jp/news/pdf/kinkyujitaisengen_gaiyou0525.pdf. (in Japanese). Accessed 6 Aug 2021.

- 10.NHK. https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/html/20200630/k10012488521000.html. (in Japanese). Accessed 6 Aug 2021.

- 11.Disaster Prevention Information. https://www.bousai.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/_res/projects/default_project/_page_/001/011/762/13kai/20201001.pdf. (in Japanese). Accessed 6 Aug 2021.

- 12.Official media of prefecture. https://uub.jp/cvd/cvd2.html. (in Japanese). Accessed 6 Aug 2021.

- 13.American College of Surgeons. COVID-19: elective case triage guidelines for surgical care. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-case. Accessed 20 July 2021.

- 14.CovidSurg Collaborative Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. Br J Surg. 2020;107:1440–1449. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.CovidSurg Collaborative Effect of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns on planned cancer surgery for 15 tumour types in 61 countries: an international, prospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00493-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okuno T, Takada D, Shin JH, Morishita T, Itoshima H, Kunisawa S, et al. Surgical volume reduction and the announcement of triage during the 1st wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: a cohort study using an interrupted time series analysis. Surg Today. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00595-021-02286-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyawaki A, Tomio J, Nakamura M, Ninomiya J, Kobayashi Y. Changes in surgeries and therapeutic procedures during the COVID-19 outbreak a longitudinal study of acute care hospitals in Japan. Ann Surg. 2021;273:e132–e134. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Jabir A, Kerwan A, Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Khan M, Sohrabi C, et al. Impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on surgical practice—part 2 (surgical prioritisation) Int J Surg. 2020;79:233–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ACS. Guidelines for triage and management of elective cancer surgery cases during the acute and recovery phases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. 2020. https://www.facs.org//media/files/covid19/acs_triage_and_management_elective_cancer_surgery_during_acute_and_recovery_phases.ashx. Accessed 29 Aug 2021.

- 20.Oba A, Stoop TF, Löhr M, Hackert T, Zyromski N, Nealson WH, et al. Global survey on pancreatic surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Surg. 2020;272(2):e87–e93. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Japan Cancer Society. https://www.jcancer.jp/wp-content/uploads/TAIGAN-04_4c-1.pdf. (in Japanese). Accessed 6 Aug 2021.

- 22.Inchingolo R, Acquafredda F, Tedeschi M, Laera L, Surico G, Surgo A, et al. Worldwide management of hepatocellular carcinoma during the COVID-19 pandemic. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:3780–3789. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i25.3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sagami R, Nishikiori H, Sato T, Tsji H, Ono M, Togo K, et al. Aerosols produced by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a quantitative evaluation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:202–205. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maruyama H, Hosomi S, Nebiki H, Fukuda T, Nakagawa K, Okazaki H, et al. Gastrointestinal endoscopic practice during COVID-19 pandemic: a multi-institutional survey. Rom J Intern Med. 2021;59:166–173. doi: 10.2478/rjim-2020-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manzia TM, Angelico R, Parente A, Muiesan P, Tisone G. Global management of a common, underrated surgical task during the COVID-19 pandemic: gallstone disease-an international survery. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2020;57:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peckham-Cooper A, Coe PO, Clarke RW, Burke J, Lee MJ. The role of cholecystostomy drains in the management of acute cholecystitis during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. What can we expect? Br J Surg. 2020;107:e447. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caballero JM, González LG, Cuéllar ER, Herrero EF, Algar CP, Jodra VV, et al. Multicentre cohort study of acute cholecystitis management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2021;47:683–692. doi: 10.1007/s00068-021-01631-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campanile FC, Podda M, Arezzo A, Botteri E, Sartori A, Guerrieri M, et al. Acute cholecystitis during COVID-19 pandemic: a multisocietary position statement. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:38. doi: 10.1186/s13017-020-00317-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Society of Thoracic Surgeons. https://www.sts.org/media/news-releases/covid-effect-leads-fewer-heart-surgeries-more-patient-deaths. Accessed 6 Aug 2021.

- 30.Gaudino M, Chikwe J, Hameed I, Robinson NB, Fremes SE, Ruel M. Response of cardiac surgery units to COVID-19: an internationally-based quantitative survey. Circulation. 2020;142:300–302. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Medas F, Ansaldo GL, Avenia N, Basili G, Bononi M, Bove A, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgery for thyroid cancer in Italy: nationwide retrospective study. BJS. 2021;108:e166–e167. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znab012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kvasnovsky CL, Shi Y, Rich BS, Drick RD, Soffer SZ, Lipskar AM, et al. Limiting hospital resources for acute appendicitis in children: lessons learned from the U.S. epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pediatr Surg. 2021;56:900–904. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee-Archer P, Blackall S, Campbell H, Boyd D, Patel B, McBride C. Increased incidence of complicated appendicitis during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Paediatr Child Health. 2020;56:1313–1314. doi: 10.1111/jpc.15058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher JC, Tomita SS, Ginsburg HB, Gordon A, Walker D, Kuenzler KA. Increase in pediatric perforated appendicitis in the New York city metropolitan region at the epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak. Ann Surg. 2021;273:410–415. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hayatghaibi SE, Trout AT, Dillman JR, Callahan M, Iyer R, Nguyen H, et al. Trends in pediatric appendicitis and imaging strategies during Covid-19 in the United States. Acad Radiol. 2021;S1076–6332(21):00363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2021.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.COVID Surg Collaborative Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS-CoV-2 infection: an international cohort study. Lancet. 2020;396:27–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31182-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lei S, Jiang F, Su W, Chen C, Chen J, Mei W, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing surgeries during the incubation period of COVID-19 infection. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;21(2020):100331. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osorio J, Madrazo Z, Videla S, Sainz B, Rodríguez-González A, Campos A, et al. Analysis of outcomes of emergency general and gastrointestinal surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Surg. 2021 doi: 10.1093/bjs/znab299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oran DP, Topol EJ. The proportion of SARS-CoV-2 infections that are asymptomatic a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2021 doi: 10.7326/M20-6976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Japan Surgical Society. http://www.jssoc.or.jp/aboutus/coronavirus/info20200518.pdf. (in Japanese). Accessed 6 Aug 2021.

- 41.Japan Surgical Society. http://www.jssoc.or.jp/other/info/info20210603-02.pdf. (in Japanese). Accessed 6 Aug 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 Weekly volume of 15 procedures according to the three groups (high, medium, low) of regional infection level. Shaded areas show the periods of the first and second pandemic waves (February 26-May 26, and July 1-September 29, respectively) (PDF 7242 KB)