Abstract

Public health advocates highlight the role of corporate actors and food marketing in shaping diets and health. This study analyses insider-oriented communications in food industry magazines in the UK to analyse actions and narratives related to health and nutrition, providing insights into relatively overlooked areas of marketing strategy including inter-firm dynamics.

From a sample of four specialized food industry magazines covering the main industry segments we identified 319 articles (published 2007–2018) mentioning health or nutrition together with industry actions affecting the food environment. We identified health-related actions and analysed underlying strategies through content and thematic analyses.

Health and nutrition have a rapidly growing role in food marketing strategy. Content analysis revealed a focus on ultra-processed foods, as well as product and nutrient-specific trends including increased health-based marketing of snacks and “protein rich” products. Health-related actions predominantly relied on consumer agency rather than invoking structural food environment changes. Thematic analysis identified proactive and defensive marketing strategies. Proactive approaches included large investments in health-related promotion of ultra-processed foods which are made highly visible to competitors, and the reliance on a “credence goods” differentiation strategies. Defensive strategies included a ‘Red Queen’ effect, whereby firms take health-related actions to keep up with competitors.

These competitive strategies can create challenges, as well as some opportunities, for public health promotion. Challenges can include undermining efforts to support product comparison and healthier choice, and limiting firms’ engagement in specific health improving actions. Systematic analysis of health-oriented marketing strategies could support more effective public health intervention.

Keywords: Health, Nutrition, Corporate, Marketing, Strategy, Differentiation

Highlights

-

•

We analyse a decade of insider-oriented news from UK food industry magazines.

-

•

We focus on health-related food marketing strategy and public health implications.

-

•

Important drivers include policy, consumer awareness and inter-firm dynamics.

-

•

There is potential for misalignment between key strategies and public health goals.

-

•

Marketing strategy and inter-firm dynamics monitoring can support effective policy.

1. Introduction

Obesity rates and the related burden of non-communicable disease (NCD) have increased in the last decade across high, middle and low income countries, constituting one of the main drivers of disease globally (Malik et al., 2020). In the UK, around 25% of adult women and over 20% of men are obese (OECD, 2020), which is one of the highest rates of obesity prevalence in Europe and globally. Unhealthy, obesogenic “food environments”, encompassing the availability, affordability convenience and desirability of food products, have been identified as a key driver of inadequate diets (Herforth & Ahmed, 2015), (Turner et al., 2017).

In response to this threat, governments have imposed taxes on unhealthy food products and introduced regulations to food processing, labelling and advertising, while calling for food industry voluntary action. (Hawkes et al., 2013)., (Kumanyika & Dietz, 2020)

These government policies have been accompanied by civil society efforts (Shekar & Popkin, 2020), (Knai, Petticrew et al., 2015), increasing consumer interest in healthy diets (Scrinis, 2013) and the adoption of a number of health-oriented pledges and actions by the food industry, including product reformulation, changes in labelling or portion size and launches of products claiming to have health benefits (Scrinis, 2016).

Although there has been progress towards some public health goals, such as a small reduction in the sugar content of foods (Berger et al., 2019) and a reduction in the contents and overall purchases of sugar from non-alcoholic drinks, as a result of the Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL) introduced in 2018 (UK government, 2020) (Scarborough et al., 2020) (Pell et al., 2021), there is also widespread concern among public health experts about the limited effectiveness of government policies, and particularly about the role of food industry actions in undermining public health goals (Hilton et al., 2019), (Scrinis, 2016).

This includes corporate efforts aimed at reframing the issue of obesity to deflect responsibility away from food companies to the individual, co-option of narratives around nutrition and physical activity and the avoidance of regulation through voluntary actions which have often been shown to lack additionality with respect to changes already planned and thus have limited effectiveness (Clapp & Scrinis, 2017), (Scott et al., 2017), (Durand et al., 2015). The use of health-related language and branding to promote ultra-processed and HSSF products, such as breakfast cereals, ultra-processed snacks and high fat spreads (Whalen et al., 2018) is also controversial. The related trends of “nutritionism” (the reduction of food's nutritional value to its individual nutritional components) (Scrinis, 2008) and functionalisation (promotion of foods as providing specific health benefits) (Scrinis, 2016) have also been identified as potentially risky for health.

These industry actions are driven by companies’ strategies in their inter-related socio-political and economic environments (Geels, 2014). Research into health-related industry strategies has thus far focussed mainly on the former, analysing narratives aimed at “outsider” stakeholders such as government and the general public (Clapp & Scrinis, 2017), (Scott et al., 2017), (Hilton et al., 2019), (Lauber et al., 2020). This literature provides valuable insights into how industry uses lobbying, corporate social responsibility and other “outsider” communications to: gain political power and influence; improve the image and societal legitimacy of the industry as a whole; and prevent and delay regulation (Clapp & Scrinis, 2017), (Scott et al., 2017).

However, the analysis of narratives concerning health-related competitive strategy, or “marketing strategy”, taking place in firms' economic environment and including inter-firm dynamics, has been comparatively neglected (Porter, 1980). Marketing strategy includes decisions such as which markets to enter and how to position a company's products in relation to their competitors' in terms of quality, differentiation versus similarity or price and, as such, can have direct impacts on food environments and, through them, on dietary outcomes. Firms' marketing strategies can also interact with public health interventions aimed at shaping food environments, in ways that amplify or undermine their goals. Analysis of discourse and narratives surrounding health-oriented marketing strategies can greatly benefit, therefore, from the analysis of communications aimed at industry “insiders”, such as competitors, suppliers, distributors and investors, which describe economic considerations as well as dynamics and interactions among industry actors.

In order to address this gap in the literature, this study provides an analysis of trends in discourse around health-related food product marketing in specialized food industry magazines, published between 2007 and 2018. These magazines are aimed at supply chain managers, decision-makers and investors in the UK food sector and draw on market analysts’ assessments as well as press releases and direct quotes from companies.

In particular, the aim of this study is to analyse how food environments and, in particular, health-related food product availability, characteristics, pricing, information and potential desirability can be shaped by companies' marketing strategies and their main societal and sectoral driving forces (including, for example, threats from competitors and policymakers’ decisions). Health-related marketing of food products includes actions such as reformulation, addition of labels highlighting nutritional or health properties, increased prices for unhealthy food options or discounts for healthier foods among other strategies.

The period chosen for our analysis coincides with an increasing policy focus on improving diets in the UK, starting with the 2007 Foresight report entitled “Tackling Obesities: future choices” (Butland et al., 2007).

We focus on health-oriented industry actions that affect the proximal food environment (Hollands et al., 2017), which shapes consumer choices at the point of purchase.

Through a content and thematic analysis, we address the following research questions:

What types of health-oriented actions affecting the proximal food environment have been discussed in insider-oriented industry magazines? How do these actions relate to underlying marketing strategy and its driving forces (given by consumer demand, inter-firm dynamics and socio-political context). Finally, we discuss the implications of our findings from the point of view of public health policy, focussing on how different marketing strategies might affect policy success or alignment of industry and policy objectives, and how increased awareness of health-related marketing strategies might support more effective policy.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy and inclusion criteria

We searched a purposive sample of four food industry magazines which cover the four market segments: supermarkets, general convenience stores, caterers, and other food services. Magazines were selected based on: 1) online availability of articles; 2) presence of a search engine; 3) not product-specific; 4) pilot searches showing relevant content, and 5) content available for the entire period of study or, at minimum, for the years 2015–2018 where most health-related content can be found. The four magazines were: The Grocer,1 Convenience Store,2 FMCG- Food and Drink Industry Magazine,3 and The Caterer.4

The search strategy is described in Fig. 1 and detailed lists of search terms and nutrition or health key terms used for double-checking are provided in Tables S1 and S2. The search and inclusion criteria were informed by the TIPPME framework (Hollands et al., 2017), described in Section 2.2.1.

Fig. 1.

Search results and strategy: PRISMA diagram.

2.2. Theoretical background and conceptual framework

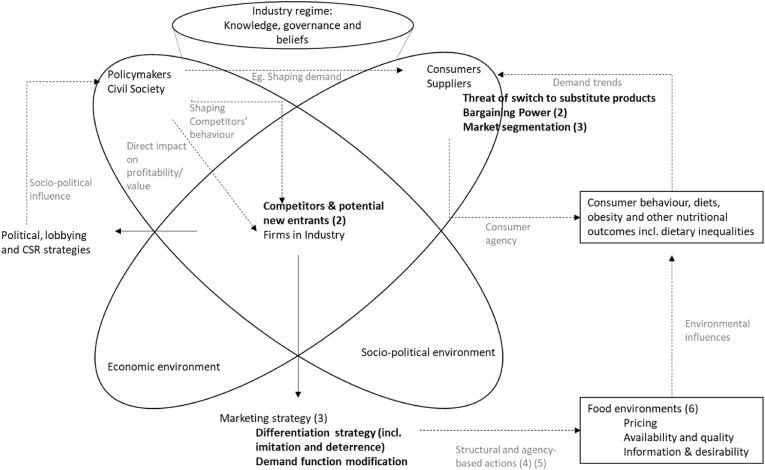

The analysis is supported by a conceptual framework that builds on Geels (2014) “Triple Embeddedness Framework” (TEF). The original framework was explicitly designed to be applied to large-scale societal challenges, such as climate change and obesity, identifying the roles and potential contributions of firms within sectors, which are understood to be embedded in and co-evolving with their economic, and socio-political environments, as well as a specific “industry regime”, given by the norms and beliefs prevalent in the sector.

We expand on the characterization of the economic environment, introducing core concepts from the classic marketing and monopolistic competition literature, (Chamberlin, 1933), (Porter, 1997), (Dickson & Ginter, 1987), which Geels (2014) refer to but does not incorporate in detail. We then adapt the framework for its application to the analysis of food environments and nutritional outcomes as a societal challenge.

Fig. 2 depicts how food companies' marketing strategy, also referred to as competitive strategy, is shaped to a large extent by key forces within the economic environment, as described in the classic theory developed by Porter (1997). These key forces include the threats from competitors and new entrants, dependent to a large extent on industry structure; the threats from a potential switch of consumers or buyers to substitute products, and the bargaining power of buyers/consumers or suppliers. Although not described by Porter as one of the main forces, the segmentation of the market into sub-categories described by different demand functions, or demand patterns, has subsequently been recognised as a key feature of firms’ economic environment which contributes to shaping competitive strategy (Dickson & Ginter, 1987).

Fig. 2.

Conceptual framework.

Socio-political actors can influence marketing strategies through their influence on these key forces, for example, affecting demand or competitors' behaviour, or by directly impacting on a companies’ profitability or value (eg. through taxation, bans or fines).

The combination of these forces and influences shapes marketing strategy which, following (Dickson & Ginter, 1987) can be described as consisting of a combination of differentiation strategies and demand function modification. The former involves creating products that differ from those of competing firms in their characteristics, or in how they are perceived by consumers. One important feature of differentiation strategy is the deterrence of imitators, which can be attempted through various approaches (Fisher, 1991), (Piazzai & Wijnberg, 2019).

Demand function modification involves attempts at influencing consumers’ preferences or, in other words, the relationship between product characteristics and demand.

Both elements of marketing strategy contribute to shaping food environments (Herforth & Ahmed, 2015), by determining which products are available, at what price, and how they are presented to consumers. Food environments, in turn, are recognised as having a crucial influence in consumer behaviour and related dietary outcomes, including obesity as well as other nutrition-related disease (Herforth & Ahmed, 2015).

Public health researchers have classified specific actions or interventions in terms of how they affect food environments and consumer behaviour. Hollands et al. (2017) developed a reliable typology of interventions in terms of the changes they produce in the proximal physical food environment, including standardized definitions (see Table 1). The original typology includes the following categories: availability, position, functionality, presentation, size and information. We expanded the typology to include price which, although not strictly a physical component of the proximal food environment, is an important component of marketing strategies at the point of purchase. This typology is mainly descriptive in nature, and used as such in this study, to map actions identified as part of the content analysis.

Table 1.

Types and number of actions discussed.

| Food industry actions affecting the proximal food environment (number of articles mentioning) | Primarily Agency-baseda | Primarily structuralb |

|---|---|---|

| Availability and reformulation | New, “healthier” products available (n=195) | Reformulation of existing products or total/partial removal of less healthy products (n=57) |

| Size | Smaller version available, snack versions (n=30) | Reduce default portion or size (n=9) |

| Information | Health or nutritional claims on specific products (n=42) | Traffic light labelling, GDA, removal of misleading health claims according to regulation (n=11) |

| Position, Presentation and Functionality | Easy-open/sealable products or other formats to facilitate portion control (n=8) | Positioning unhealthy products/menu items in less visible places etc, plain packaging, appealing packaging to promote healthier products (n=13) |

| Pricing | Discounts for healthier food/price increases from taxation passed on to consumer (n=5) |

Authors' own elaboration based on Agento-Structural classification (Backholer et al., 2014), TIPPME typology (Hollands et al., 2017). . See Section 2.2 for a full description and discussion.

Primarily agency-based actions are those that rely on consumers' active health-seeking behaviour to affect health.

Primarily structural actions are those that can promote healthier choices even in the absence of active health-seeking behaviour. According to this definition, primarily structural actions do not necessarily restrict choice but might “nudge” consumers, for example by changing the default choice.

Backholer (2014) developed a more analytical approach, classifying obesity prevention strategies along an agency-structure continuum. The underlying hypothesis is that structural interventions in the food environment tend to lead to larger and more equitable changes in behaviour, whereas interventions relying strongly con consumer agency tend to be less effective and produce less equitable outcomes. This classification was developed to be applied to policy interventions and public health-prevention strategies, rather than to industry actions. For the sake of simplicity, and to adapt the classification to our context, we propose two categories: a) primarily agency-based actions that rely on consumers’ active health-seeking behaviour to affect health and b) primarily structural actions that can promote healthier choices even in the absence of active health-seeking behaviour. According to this definition, primarily structural actions do not necessarily restrict choice but might “nudge” consumers, for example by changing the default choice. These broad categories are used to classify the different TIPPME food environment actions (Hollands et al., 2017).

This framework builds on: (1) (Geels, 2014); (2) (Porter, 1997); (3) (Dickson & Ginter, 1987); (4) (Backholer et al., 2014) (5) (Hollands et al., 2017), and (6) (Herforth & Ahmed, 2015). Elements and detail added or expanded with respect to the original framework are either framed in boxes, highlighted in bold or shown in light grey. Solid arrows point towards firms' strategies emerging from the interaction of forces in the economic and socio-political environments. Dotted lines represent influences between actors’ behaviours and societal phenomena. Light grey labels describe the nature of these influences.

2.3. Analysis

The documents were analysed using content and thematic analysis, facilitated by NVivo12 software (NVivo, n.d.).

2.3.1. Content analysis

Given the large number (n=319) of articles, we first carried out a descriptive and quantitative analysis of content. This process serves to characterise the body of data, contextualise the analysis and highlight relevant trends and changes in content across time.

The content analysis focussed on the frequency of health as a theme and mentions relating to nutritional content and composition, specific consumer groups, types of health-oriented action, meal occasion and type of product. The latter was determined based on the NOVA classification dividing foods and beverages into four categories: unprocessed or minimally processed foods and drinks; processed culinary ingredients; processed foods; ultra-processed food or drink products (Monteiro et al., 2016)).

All of the above categories except for the different types of health-oriented actions were coded based on automatic text search of key words. The lists of key words for content analysis were elaborated iteratively. We started with a pre-defined list based on researchers’ prior knowledge of the topics, and then refined these based on preliminary analysis of the text. All coding categories were manually checked to ensure appropriate interpretation of the terms in context. Health-oriented actions on the food environment were manually sorted into two categories, based on the framework proposed by Backholer (2014) (See Section 2.2.1).

2.3.2. Thematic analysis

Focussing on the main types of actions and product categories identified in the content analysis, key themes were identified and analysed. An inductive-deductive analysis (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006) was carried out. The analysis built upon the codes presented in the descriptive content analysis. A thematic analysis seeks to identify patterns of language-use and interpretation. based on a relativist and interpretive approach, involving constant comparison and theoretical sampling (Aronson, 1994). Open coding was used to identify and categorise descriptions of the drivers of action, actors involved and notions of challenge and opportunity. Selective coding was used to identify the values and motivations that linked codes. Finally, a coding frame was developed and refined to capture the main concepts and then used to group codes into themes around the defensive and proactive deployment of health in processed food launches, labelling and reformulation.

3. Results

3.1. Content analysis: emerging trends and patterns

Overall, in the first years of the period of analysis (2007–2014) only a small proportion of all articles published discussed health and nutrition-oriented actions affecting the proximal food environment. However, from 2015 the number and share over total articles published starts to grow rapidly (Fig. 2). The increase in the share of health related news articles is broadly consistent across the magazines (Table S3 shows figures disaggregated by magazine), and coincides with policy developments, such as the announcement of UK Government's Childhood Obesity Strategy (UK Government, 2016a), Public Health England's sugar reduction programme (UK Government, 2015) and the Soft Drinks Industry Levy (UK Government, 2016b). It should be noted that a small proportion of the post-2015 increase is due to the higher proportion of health-related articles in the FMCG Magazine, whose online archive coverage starts in 2015.

Next, we will breakdown nutrition related trends including: product formulation; product type; targeting of population groups; eating occasions and types of action based on the modified TIPPME framework.

3.1.1. Nutrition-related trends

Fig. 3 shows mentions of different nutrition-related key terms used in the articles over time (corresponding figures shown in Table S4). The most common term is ‘sugar’, which is unsurprising given that much of the public health focus is on reducing sugar consumption in fighting obesity as well as the moderate success of the sugar reduction programme (Berger et al., 2019). Second-most common terms related to calories and portion control, followed by artificial ingredients. A noticeable switch occurs between salt and protein with the latter becoming more prominent in 2018 and salt relatively less mentioned. The notable absence of increased references to salt could be explained by the ending of the salt reduction programme in 2017 (PHE, 2017). Proportion of mentions of saturated fats also declines over time.

Fig. 3.

Proportion of included articles discussing health-oriented industry actions over total published.

Note: Percentages calculated based on three of the four magazines for which total number of articles was retrieved. These represent 96% of all included articles.

3.1.2. Product categories, consumer targeting and eating occasions

Of the 41 articles where a target population was identified, 24 mentioned children, mums or parents, while the remaining 17 identified other groups such as adults or professionals. In terms of the meal occasions targeted. There is a marked shift towards articles mentioning snacks or snacking as opposed to meals as an eating occasion (see Fig. 4, Table S5 in the Supplementary File) (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Number of included articles mentioning different nutrition-related key terms (1).

Note: Because we code the first mention of each key word in each article, with many articles mentioning several key terms we show total numbers instead of proportions in this graph.

Fig. 5.

Number of included articles mentioning different eating occasions.

Of the 319 included articles, 303 identified specific products or product ranges. Using the NOVA classification for food groups (Monteiro et al., 2016), 83% of the products or product ranges mentioned are considered ultra-processed food or drink products.

3.1.3. Type of action discussed

Most health-oriented actions discussed in the articles rely strongly on consumer health-seeking behaviours (Table 1 below shows summary figures for types of action; Table S6 in the Supplementary File shows figures disaggregated by year).

These agency-based actions most commonly involve a healthier option or alternative being made available for consumers to choose. More structural actions were also announced and discussed, predominantly consisting of reformulation, adoption of traffic-light labelling and fewer mentions of reductions in default portion size. Other structural actions that have been researched and proposed in the public health literature are very infrequently mentioned, including positioning less healthy products away from visible places, adoption of plain packaging for less healthy foods, appealing packaging for healthier products, and price incentives to switch to healthier foods. However, this is not necessarily a reflection of the actual frequency of adoption of these measures, and could reflect a lack of interest in revealing this type of action in outward communication.

3.2. Thematic analysis: defensive and proactive deployments of ‘health’ in marketing strategy

The content analysis showed that the most frequently discussed actions in the context of statements about health were new product launches, followed by reformulation and nutritional labelling or health claims, all of which concern mainly ultra-processed foods. As these appear to be the health-related actions that generate the most discursive interest, they are the main focus of our thematic analysis, and are henceforth referred to as “health-oriented actions” or “health-related actions”.

In the rest of this section we analyse discourse surrounding health-related actions, organising emerging themes in terms of the main underlying marketing strategies and their driving forces as presented in the framework (Fig. 2). This includes differentiation strategies, imitation deterrence, demand creation and direct responses to external pressure. We also identify those themes and strategies discussed as mainly proactive and those discussed as predominantly defensive.

3.2.1. Health-based differentiation: proactive and defensive strategies

3.2.1.1. Health-based differentiation as a proactive strategy

Health-oriented actions were frequently discussed as attempts to achieve “product differentiation”, presented as an opportunity to capture a share of a growing market. Increased health consciousness is predicted to create a demand, and it is suggested that early positioning of the brand within that market will confer some advantage over competitors. According to this narrative, companies prospectively identify an opportunity based on market analysis and projected trends, and address this through health-related actions. Companies, therefore, are depicted as proactive in the sense of actively seeking opportunities. However, they are presented as reactive with respect to consumer preferences which are discussed as exogenous forces to be analysed and incorporated into the firm's strategy, rather than influenced by companies.

Cold pressed juices brand [BRAND X] is aiming for a bigger share of the health drink industry with the launch of new [PRODUCT X MILK DRINK]. With one in five households having made the switch to dairy-free milk, [BRAND X] is positioning itself well with its product which contains three times the amount of almonds found in other almond milk products (7% compared to the industry standard of 2–3%). The market for almond milk is valued at £198m and a steady category growth through to 2019 (Mintel April 2015) is predicted. With consumers becoming more health conscious and intolerances on the rise, the dairy free market has grown at a rate of 70%–80% year on year to date. (Convenience Store, 2015)

[PRODUCT X] are a range of fruit and vegetable juices enriched with vitamins A, C and E and provide 100% of the recommended intake in each one litre carton. […] “We identified a clear opportunity in the market to meet a growing consumer need, across both dairy and non-dairy offerings, which we are confident has been met by the [BRAND X] brand. (Convenience Store, 2017)

In terms of the action itself, these portrayals emphasize how a health-oriented innovation will affect brand image (generally positively) and the “uniqueness” of the product.

The company believes that there is growing demand from busy consumers for a ready mixed high energy drink with functional benefits from Vitamin B6 and BCAAs. The unique recipe for its product, marketed under the ‘[BRAND X]’ brand, includes BCAAs or branched chain amino acids, which are the building blocks of protein that aid the body's recovery and performance. (Convenience Store, 2017)

Rapidly growing UK nutrition brand [X] is next week launching a new protein cookie. […] It is believed to be the only protein cookie on the market which uses plant-based protein and is both gluten free and vegan. […] The current ‘clean eating’ trend has seen this type of nutritious snacking becoming more mainstream with many consumers now looking for a grab ‘n’ go healthy protein snack and consequently we're keen to talk to new retailer partners throughout the UK […]. (FMCG, 2017)

Sugar reduction features prominently in this theme, as it does throughout the data. This theme, however, is strongly associated with changes whose health benefits are comparatively unclear, compared to sugar or salt content which are shown on standardized content labels. These include claims related to “natural ingredients”, vitamins, dairy-free formulations “branched chain amino acids”, “functional benefits” or high protein and “free-from” formulations. These claims are also harder for consumers to verify, compared to sugar or salt levels, which are included in ingredients lists and often reflected in standardized front of pack labels.

In industrial organization and marketing strategy theory, products such as those described above can be characterised as “credence goods”; goods for which, even after trying them, the consumer does not have sufficient information to decide whether or not they need more of them, and are unable to assess their quality or compare with alternatives, (Emons, 1997; Veeman, 2002).

Theory posits that, when consumers' difficulty comparing across products (evaluation cost) is high, the purchase decision will rely strongly on the producer's reputation, creating a barrier against imitation from competitors (Fisher, 1991; Makadok, 2010). This results in a more “durable” differentiation strategy (Fisher, 1991), whereby the advantage obtained by the innovator can endure and is not easily eroded by imitations. The role of “credence goods” in health-based differentiation is apparent also in the sub-theme “Escaping the Red Queen” (see section c) below).

3.2.1.2. Keeping up with competitors’ health-oriented actions: the Red Queen effect

The analysis revealed considerable pressure to adopt health-orientated actions in order to keep pace with competitors, particularly with regard to factors such as labelling. In marketing literature, this type of competitive dynamics are sometimes referred to as the “Red Queen effect” (Derfus et al., 2008), in reference to the Lewis Carroll character, who ran as fast as she could just to “keep in the same place” (Carroll, 1917).5 This term has also been used in the context of evolutionary theory (Van Valen, 1977), where it was first coined to refer to the fact that species must constantly evolve and adapt simply to keep a constant probability of survival, because they are competing with equally evolving species in the context of environmental changes and pressures. This was originally used to explain the finding that species that have existed for longer and, therefore, evolved for longer are not less likely to become extinct (Liow et al., 2011).6 Similarly, firms must often take actions, health-related or otherwise, simply to keep up with competitors. This results in constant innovation and defensive competitive moves. These constitute a form of differentiation, insofar as they involve changes in products characteristics to better respond to demand. These actions, however, are not necessarily expected to lead to long-term increases in profits.

In the extract below, the adoption of front of pack labelling is presented as “a climbdown”, suggesting a defensive response to external pressures. The first company's action, it is implied, creates its own incentives for competitors to follow (it is “pivotal”), in order to avoid being left behind, as “the only big mults [multinationals]” not adopting taking the specific health-oriented action.

A week after [COMPANY X's] traffic light labelling climbdown, [COMPANY Y] is set to follow in adopting a hybrid food labelling system. […] [COMPANY X's] decision to drop its years of opposition to traffic lights is being decision seen by many as a pivotal move in one of the industry's longest-running disputes. [COMPANY Y's] move leaves [COMPANIES Z and V] as the only big mults not using some form of traffic lights. [COMPANY Z] said last week it was “open-minded” about FoP labelling. (The Grocer, 2012)

There are two important implications of the above narrative. Firstly, the action is not in itself seen as profitable for each company. Secondly, adoption by competitors creates pressure for each firm so that, if one company acts, others must follow.

Similar dynamics were described for other health actions including the adoption of calorie labelling for drinks companies (The Grocer, 2016) or the reduction of salt and sugar in sauces, which was described as part of a “bruising corporate standoff” (The Grocer, 2018).

3.2.1.3. Escaping the Red Queen's race: deployment of credence goods as a defensive differentiation strategy

A third sub-theme was related to firms’ attempts to escape the Red Queen effect, discussed in the above section. This can clearly be seen in material relating to sugar reduction actions.

This is where Nordic brand [X] found its niche. Spotting the demand for so-called ‘clean labelling’, it launched its sweets without e-numbers in 2015. […]

So many have rushed to bring out their own reduced sugar lines. […] All this focus on sugar reduction is good for consumers and public health. But the numbers suggest it's not necessarily translating into growth for brands. According to [SPOKESPERSON X], four of the five top brands - including sugar-reducing [COMPANY Y]- suffered a decline in sales. So to win in the sweets market, perhaps the big boys need to take a look at the strategy of their smaller rivals. After all, it takes more than sugar to make your mark. (The Grocer, 2018)

With other players in the sector reporting success with similar functional products [offering immune support], such efforts could help, although more needs to be done to counter the hammering fruit juice is getting from the health lobby at present. (The Grocer, 2015)

Alongside turmeric's health benefits Blood Orange itself is cited for having antioxidant properties as well as being rich in vitamin C, a perfect combination for [BRAND X's] no added sugar, low calorie and vegan friendly range. [BRANDX's] range of drinks offer a natural alternative to many sugary sodas, especially at a time when more and more consumers are concerned about sugar in soft drinks. The launch is also coinciding with the sugar tax*** that has come into effect in April. (FMCG, 2018)

The first quote argues that companies are engaging in sugar reduction actions that do not increase their profits (“sugar reduction is good for consumers … but … it's not necessarily translating into growth for brands”), and suggests that other health claims such as “clean labelling” or the absence of artificial ingredients in sweets might be more likely to improve their economic performance, helping companies “make their mark”.

The second quote makes a similar argument in less explicit terms. Innovation around “functional foods” (foods claiming immune system benefits, in particular) is recommended, although we know that the “hammering” of fruit juice by the health lobby was related to sugar content, and not to insufficient immune system benefits (UK Government, 2015).

In both cases, the sugar reduction is implicitly or explicitly characterised as unprofitable while vaguer, less verifiable claims such as “natural ingredients” in sweets or “immune support” in juice are framed as potentially more profitable. In the third quote, a drink “rich in antioxidants” is launched in response to sugar-related pressure, this time framing the action as complementary to actual sugar reduction.

It is plausible to consider that sugar reduction, which may be unprofitable, is happening as part of a “Red Queen” dynamic, analogous to those discussed earlier in the analysis, or as a result of external pressure. Our analysis has emphasized how companies feel pressured to carry out this action in order not to be left behind with respect to their competitors. However, sugar content is very easy to verify, given that branded products generally include detailed and regulated nutritional content labelling. Companies, therefore, are likely to be aware that their action is easy to imitate. According to industrial organization literature, and as discussed in section 3.2.1 a), imitation can be expected to eliminate or greatly erode an innovators’ advantage (Fisher, 1991). The fact that the recommended health claims are comparatively difficult to verify, therefore, could be precisely what makes them advantageous from a commercial point of view. Consumer choice in these cases becomes heavily dependent on brand reputation, which means that once a company develops an innovation and creates a reputation around it, it is harder for competitors to imitate them.

In other words, companies might attempt to respond to external health-related pressures by producing health-oriented “credence goods” discussed at the beginning of the analysis, and therefore taking the health conversation to a more profitable territory, adopting the differentiation strategies they normally would in the absence of strong external pressures.

3.2.2. Proactive investment in health-oriented promotion, branding and advertising: deterring imitators or creating demand?

There was a strong emphasis on branding, promotion and advertisement investment as opposed to other types of investment, such as in product formulation, packaging or equipment. It is worth noting that the use of the term “marketing” in the quotes below, to refer to product promotion, differs from the more academic use of “marketing strategy” in this study and elsewhere, which refers to overall competitive strategy involving various forms of differentiation and demand modification. Twenty-nine (29) articles mentioned investment in health-related innovations, out of which only twenty (20) specified the nature of the investments. Fourteen (14) of these articles discussed investments in branding/advertising, and only six (6) mention any other type of investment, such as product formulation, functional packaging or equipment.

Food companies tended to emphasize the (large) size of the investments as a way of highlighting its significance. For example, a spokesperson from a major soft drinks company was quoted saying:

“That's important because we know a growing number of people want to reduce their sugar intake but have been reluctant to try a no-sugar option. As well as ensuring it tastes great, we're putting our biggest marketing investment in a decade behind this launch,” he said. (The Grocer, 2016).

The above quote emphasizes the fact that this is their “biggest marketing investment in a decade”. Other articles about this launch described it as “a heavyweight campaign” (Convenience Store, 2016), “a huge marketing investment” (The Grocer, 2018), or specified the amounts invested.

The importance of branding and advertisement investment is consistent with the fact that many health innovations can be characterised as credence goods, as discussed in the above section, where brand reputation can be key for consumer's decisions.

The apparent interest in highlighting the large sums invested could be an attempt at dissuading imitators. According to literature on industrial organization, large up-front investments in innovation can lead to more durable and profitable differentiation by raising the barriers to imitation from competitors (Fisher, 1991) (Piazzai & Wijnberg, 2019). If the technical and production costs of a specific innovation are not high, and competitors know this, then branding and advertising investment might be the only way to create such barriers.

Consumer demand for health was portrayed here, and in the rest of the analysis, as an exogenous force that companies tried to adapt to, while at the same time insisting on the importance of marketing investment whose purported goal is, precisely, shaping consumers’ choices. This contradictory narrative is further illustrated in the following quote:

“Shoppers are more ingredient-savvy than ever so, by simplifying the packaging, perfecting the recipe and supporting the launch with a £10m media investment, we're certain shoppers will be seeking out the new cereal bars on shelves.” (Convenience Store, 2017)

To an extent, the portrayal of companies as merely reactive to consumers’ desires can be a discursive device to deflect responsibility for the healthiness of consumers. However, an additional explanation is that companies might indeed not be interested in creating demand for a specific characteristic (e.g. foods low in sugar), which is easily imitated by competitors. Rather, they are more likely to be interested in positioning themselves within that niche and creating demand for their particular products and characteristics that might be more clearly associated with their brand and therefore harder to imitate.

3.2.3. Health-related actions as defensive strategies against external pressures

Some “defensive” health-related actions were described as attempts to prevent future losses in sales or share value. As such, these health-oriented actions often function, more or less explicitly, as a signal to investors regarding the level of exposure of a company to external health-related pressures from regulators, civil society or consumers.

This week [BRAND X] owner,[COMPANY X], whose shares are down 5% since Osborne's plans were revealed, said at least two-thirds of its portfolio would be made up of lower or no-sugar drinks when the tax comes into force, escaping any levy. Others are also racing to launch products with lower sugar, with [BRAND X] the latest to reveal “zero calorie” varieties this week. (The Grocer, 2016)

Apart from emphasizing loss-prevention, these defensive strategies were often discussed in terms of “compliance” with policy demands, making commitments, meeting targets or “supporting” government initiatives, setting a distinct discursive tone compared to proactive or “opportunity” framed actions discussed in the previous sections. Multiple external pressures were mentioned including governmental policies, (particularly the Soft Drink Industry Levy), growing consumer awareness, civil society campaigns or pressure from the “health lobby”. Actions included reformulation to avoid penalties, or changes in labelling and removal of health claims to comply with regulations or policy-driven standards.

As new government initiatives push the less-than-100kcals messaging, families are looking for new innovative ways to replace the traditional household biscuit options currently available.” That's why [BRAND X], which has lost £4.9m in value sales over the past 12 months, recently added [PRODUCT X] with just 78 calories per 18g mini-bag (433kcals per 100g). (The Grocer, 2018)

As in the two above quotes, information about nutritional content and ingredients was frequently presented only at the portfolio level. In these cases, the focus is implicitly on how an action will affect overall company exposure to health-related “risks” (eg. public health policy, consumer concerns), rather than on the potential impact of the action on consumer health. While not surprising, given the audience of these publications, this serves as a reminder that, even when directly responding to health campaigns or policies, company incentives are not necessarily aligned with public health goals. This can lead to actions that comply with the letter, but not necessarily the spirit, of a specific public health initiative. The quote below further illustrates this point.

[PRODUCTS X and Y] have reduced the size of their individual snack packs to 19.8g from 25g to ensure 100 kcals per portion. However, an additional pack has been added to offer “continued value for money”. At 139g, the new [PRODUCT X] multipacks will be 8% smaller but the RSP retail selling price] will not change. (The Grocer, 2018)

4. Discussion

This paper analysed health-related actions as presented in industry magazines through thematic and content analysis which revealed a number of insights with important implications for public health and policy making. For each theme we discuss our findings in context with the literature and outline their policy implications.

4.1. Credence goods strategies and “Red Queen” dynamics underlying health-based differentiation: policy implications

Previous research has suggested that functional foods, whose benefits are hard to verify for consumers, could be characterised as “credence goods” (Veeman, 2002). The present study shows how credence goods are systematically used as part of proactive strategies to achieve durable differentiation and to compensate for or escape less profitable reformulation dynamics that result from policy, societal pressure and competitor dynamics (e.g. Red Queen effects). For credence goods, brands become crucial to consumer choice, which acts as a barrier for imitation, potentially providing more durable differentiation, and therefore supporting a longer-term strategic advantage.

In terms of policy implications, the deployment of a “credence goods” differentiation strategy has the potential to generate tension between industry and policy goals. In particular, public health strategies aimed at improving consumers' information to support healthier choice can be in conflict with firms’ push to build reliance on specific brands for “healthiness” and to reduce the threat from consumer switch to substitute products.

The likelihood of this ongoing tension perhaps reinforces the importance of public health policy going beyond agency-based information and educational policies and towards more structural incentives. Additionally, policymakers can try to trigger “Red Queen” dynamics involving competitive health-oriented actions, while simultaneously monitoring emerging product differentiation and regulating where necessary to avoid misinformation and facilitate consumers’ comparison across products.

4.2. The central role of advertising and promotional investments

The discursive emphasis on promotion, branding and advertising investments to support health-oriented actions stands in contrast with findings from previous literature that analysed industry submissions to policy consultations, which tended to emphasize technical difficulty of reformulation and the associated economic investment (Scott et al., 2017). The different audience and aims of the documents analysed (policy consultation versus specialized industry magazine) are the most likely explanation for these diverging findings. Where in the former there is an incentive to emphasize costs in order to influence or avoid policy intervention, the latter is mainly aimed at informing investors, competitors, suppliers and distributors. Such industry insiders are likely to have more information about technical and production costs associated to, for example, reformulation or re-labelling and would not interpret higher-than-average technical costs as conferring commercial advantage.

It is helpful, then to think of large promotional investments and efforts to announce these investments to competitors and other industry stakeholders, as fulfilling a dual purpose: sending a signal to competitors about the firms' commitment to a specific health-based differentiation strategy in order to deter potential imitators, and shaping consumers’ preferences for health-related attributes.

Policymakers, therefore, should consider the potential impacts of such investments in the context of agency-based interventions aimed at modifying consumers’ health-oriented choices, as well as in the context of policies whose success might depend on strategic interaction among competitors.

In terms of the former, it is hard to make general predictions, given the complex and case-specific impacts of health-oriented advertising campaigns on consumer demand. Overall, however, our analysis suggests that there is no reason to assume that such health-oriented promotional investments can be leveraged for public health purposes, given that marketing strategies are often aimed at differentiating one “healthy” ultra-processed food product from a very similar one, creating demand for specific characteristics that can be associated to a particular brand. With regards to the latter effect, policymakers should anticipate that large and widely publicised promotional investments, by deterring imitators, might reduce the success of initiatives that depend on firms following market leaders or early adopters/compliers in implementing particular health-oriented actions. This could be the case of voluntary labelling or reformulation schemes, for example. In these cases, policymakers could anticipate the need for additional incentives or regulatory approaches to ensure adoption.

4.3. Health-oriented actions as a defensive strategy against external pressure

We found that some actions were clearly framed as defensive against pressure from policymakers, civil society or consumer demands. In these cases, the impact of such pressure on share values and profitability tended to be emphasized, and reactive health-oriented actions were often framed in terms of compliance with specific requirements (eg. specific information on labels, nutritional contents below a particular threshold). However, the analysis also suggested potential misalignments between public health policy goals and firms’ strategies. In particular, defensive strategies were often defined at the product portfolio level, and involved launches of new “compliant” products, while often maintaining the original, less healthy products. Additionally, defensive actions could involve sticking to the letter, rather than the spirit of the specific policy (eg. reducing each individual portion size while increasing the number of portions in each multipack).

Policymakers should pay increased attention to how such misalignments can have the potential to increase health-related market segmentation and undermine the intended goals of a policy or civil society campaign, or exclude certain consumer segments from their benefits. Ongoing monitoring and perhaps targeted interventions aimed at specific consumer segments which disproportionately consume the “least healthy” product versions could potentially increase policy effectiveness.

4.4. Product-specific trends: protein-rich foods and “healthier” snacks

The broad terms identified in the content analysis, in terms of focus on ultra-processed foods and emphasis on actions reliant on consumer agency as opposed to structural change, were used to frame the thematic analysis and its discussion. However, some additional specific trends were identified which can have significant public health implications. The increased focus on marketing of protein-rich foods coincides with a recent study showing an increase in protein purchase per capita in the UK (Berger et al., 2019). This trend warrants further analysis because some recent studies have warned about potentially negative effects of excessive protein intakes that might result from it (Mittendorfer et al., 2020), while others suggest it might benefit some population groups where the contribution of protein to dietary energy is still below recommended levels (Bennett et al., 2018).

The increased focus on “healthy” snack promotion is likely to mirror an increased consumption of snacks overall (Kantar Worldpanel, 2018, 2019), and the fact that snacks offer opportunities for “additional” sales [and calories] through added eating occasions, rather than mere substitution of one product for another. Overall, this trend and the extent of commercial interest and discussion can constitute an opportunity for policy-makers to support healthier choices by going beyond the current focus on calorie content and making it easier for consumers to access truly healthier snacks instead of accessing same types of ultra-processed snacks but in smaller package size, often sold in larger multipacks.

4.5. Study limitations

The analysis, while thorough within its remit, cannot be considered comprehensive, in that only a purposive sample of food industry magazines were screened. However, the risk of bias was minimised by sampling one magazine from each of the four main industry segments and by carrying out a thorough content analysis which confirmed that the broad trends identified in terms of product and nutrient focus, corroborated with those identified in previous studies (Berger et al., 2019), (Scrinis, 2016), (Samoggia et al., 2019).

The thematic analysis focusses only on a sub-set of actions aimed at the proximal food environment. There was insufficient depth of information about certain strategies to inform a full thematic analysis. These included “nudge” strategies such as repositioning foods in the aisles or away from the counter, introducing plain packaging for unhealthy food or about price subsidies for healthier foods. While these are potentially relevant to public health, they seem to generate comparatively little discursive interest in communications aimed at industry insiders.

5. Conclusions

Using an adapted “triple embeddedness” framework (Geels, 2014), this study analyses how health-oriented or health-framed actions can be used by companies as part of strategies to differentiate their products, discourage imitation, react to competitors’ actions, adapt to changes in demand and limit share value losses related to public health policy pressures.

Our analysis suggests that there is the potential for inherent misalignment between public health policy goals and some health-oriented competitive strategies. This can be the case, particularly, in the context of policies aimed at facilitating comparison across products in terms of their healthiness and supporting health-based consumer choice, for initiatives that rely on firms following market leaders’ adoption of specific health-related actions, or for interventions that aim to economically incentivize firms to comply with a specific standard.

Firms’ attempts to adopt “credence goods” differentiation strategies, deter imitators through widely advertised promotional investments and design their portfolios to achieve market segmentation, among others, can undermine the effectiveness of these polices.

We recommend that policymakers should carefully consider the interaction of each intervention with firms' health-related marketing strategies and, in particular, the strategies described in this study. An analytical framework similar to the one proposed here could be used to assess how each intervention can affect firms' share values under different strategies, consumer demand including switching behaviour and segmentation, and inter-firm dynamics including imitation and deterrence. This could support more effective policy design with compensatory interventions to avoid undesirable impacts, while allowing policymakers to leverage any opportunities for alignment between policy and industry strategy, for example, encouraging “Red Queen” inter-firm competition where companies carry out health-oriented product differentiation to keep up with competitors’ moves.

Funding

SC is funded by a grant from the Wellcome Trust (grant number 205200) under its ‘Our Planet, Our Health’ initiative. LC is funded by a UK Medical Research Council fellowship (MR/P021999/1). CT is funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration East of England (ARC EoE) programme. The view expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. Funding bodies had no involvement in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Co-author contributions

Soledad Cuevas: Conceptualization, analysis and writing; Nishali Patel: Conceptualization, analysis and writing; Claire Thompson: Conceptualization, and writing; Mark Petticrew: Feedback on conceptualization, contribution to draft writing, revision and editing; Richard Smith: Feedback on conceptualization, contribution to draft writing, revision and editing; Steven Cummins: Feedback on conceptualization, contribution to draft writing, revision and editing; Laura Cornelsen: Conceptualization, analysis, writing, super.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Footnotes

The Grocer covers grocery sales, finance and marketing, including in-depth coverage of the supermarket sector in the UK (TheGrocer, n.d.).

Convenience Store provides business information for and about UK convenience retailers (ConvenienceStore, n.d.).

The Food and Drink Industry Magazine covers the production, distribution and sales food products in the category of fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG -The Food and Drink Industry Magazine, n.d.).

The Caterer covers the catering and hospitality sector (TheCaterer, n.d.).

Originally published in 1871.

The term has since acquired different meanings in biology and the above use is sometimes referred to as “Van Valen's Red Queen”.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100953.

Contributor Information

Soledad Cuevas, Email: sol.cuevas@lshtm.ac.uk.

Nishali Patel, Email: patelnk@uw.edu.

Claire Thompson, Email: c.thompson25@herts.ac.uk.

Mark Petticrew, Email: mark.petticrew@lshtm.ac.uk.

Steven Cummins, Email: steven.cummins@lshtm.ac.uk.

Richard Smith, Email: rich.smith@exeter.ac.uk.

Laura Cornelsen, Email: laura.cornelsen@lshtm.ac.uk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Aronson . 1994. A pragmatic view of thematic analysis (The Qualitative Report 2) [Google Scholar]

- Backholer K., Beauchamp A., Ball K., Turrell G., Martin J., Woods J., Peeters A. A framework for evaluating the impact of obesity prevention strategies on socioeconomic inequalities in weight. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104(10):e43–e50. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett E., Peters S.A., Woodward M. Sex differences in macronutrient intake and adherence to dietary recommendations: Findings from the UK Biobank. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger N., Cummins S., Smith R., Cornelsen L. Recent trends in energy and nutrient content of take-home food and beverage purchases in Great Britain: An analysis of 225 million food and beverage purchases over 6 years. BMJ Nutrition, Prevention & Health. 2019;2(2):63. doi: 10.1136/bmjnph-2019-000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butland B., Jebb S., Kopelman P., McPherson K., Thomas S., Mardell J., Parry V. Vol. 2. 2007. (Foresight. Tackling obesities: Future choices. Project report). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll L. 1917. Through the looking glass: And what Alice found there. Rand, McNally. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin E.M. Harvard University Press; 1933. The theory of monopolistic competition. [Google Scholar]

- Clapp J., Scrinis G. Big food, nutritionism, and corporate power. Globalizations. 2017;14(4):578–595. [Google Scholar]

- Convenience Store. (n.d). https://www.conveniencestore.co.uk/.

- Derfus P.J., Maggitti P.G., Grimm C.M., Smith K.G. The Red Queen effect: Competitive actions and firm performance. Academy of Management Journal. 2008;51(1):61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson P.R., Ginter J.L. Market segmentation, product differentiation, and marketing strategy. Journal of Marketing. 1987;51(2):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Durand M.A., Petticrew M., Goulding L., Eastmure E., Knai C., Mays N. An evaluation of the Public Health Responsibility Deal: Informants' experiences and views of the development, implementation and achievements of a pledge-based, public–private partnership to improve population health in England. Health Policy. 2015;119(11):1506–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emons W. Credence goods and fraudulent experts. The RAND Journal of Economics. 1997:107–119. [Google Scholar]

- Fereday J., Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2006;5(1):80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher R.J. Durable differentiation strategies for services. Journal of Services Marketing. 1991;5(1):19–28. [Google Scholar]

- FMCG The food and drink industry magazine. https://fmcgmagazine.co.uk/ n.d.

- Geels F.W. Reconceptualising the co-evolution of firms-in-industries and their environments: Developing an inter-disciplinary Triple Embeddedness Framework. Research Policy. 2014;43(2):261–277. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes C., Jewell J., Allen K. A food policy package for healthy diets and the prevention of obesity and diet‐related non‐communicable diseases: The NOURISHING framework. Obesity Reviews. 2013;14:159–168. doi: 10.1111/obr.12098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herforth A., Ahmed S. The food environment, its effects on dietary consumption, and potential for measurement within agriculture-nutrition interventions. Food Security. 2015;7(3):505–520. [Google Scholar]

- Hilton S., Buckton C.H., Patterson C., Katikireddi S.V., Lloyd-Williams F., Hyseni L., Elliott-Green A., Capewell S. Following in the footsteps of tobacco and alcohol? Stakeholder discourse in UK newspaper coverage of the soft drinks industry levy. Public Health Nutrition. 2019;22(12):2317. doi: 10.1017/S1368980019000739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollands G.J., Bignardi G., Johnston M., Kelly M.P., Ogilvie D., Petticrew M., Prestwich A., Shemilt I., Sutton S., Marteau T.M. The TIPPME intervention typology for changing environments to change behaviour. Nature Human Behaviour. 2017;1(8) [Google Scholar]

- Kantar Worldpanel . 2018. Out of home, Ingredients for sustained growth (thoughts on.) [Google Scholar]

- Kantar Worldpanel . 2019. EAT, drink & be healthy HOW at-home consumption IS changing. [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika S., Dietz W.H. Solving population-wide obesity—progress and future prospects. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383(23):2197–2200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2029646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauber K., Ralston R., Mialon M., Carriedo A., Gilmore A.B. Non-communicable disease governance in the era of the sustainable development goals: A qualitative analysis of food industry framing in WHO consultations. Globalization and Health. 2020;16(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00611-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liow L.H., Van Valen L., Stenseth N.C. Red Queen: From populations to taxa and communities. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2011;26(7):349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makadok R. The interaction effect of rivalry restraint and competitive advantage on profit: Why the whole is less than the sum of the parts. Management Science. 2010;56(2):356–372. [Google Scholar]

- Malik V.S., Willet W.C., Hu F.B. Nearly a decade on—trends, risk factors and policy implications in global obesity. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2020;16(11):615–616. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-00411-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittendorfer B., Klein S., Fontana L. A word of caution against excessive protein intake. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2020;16(1):59–66. doi: 10.1038/s41574-019-0274-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro C.A., Cannon G., Levy R., Moubarac J.-C., Jaime P., Martins A.P., Canella D., Louzada M., Parra D. NOVA. The star shines bright. World Nutrition. 2016;7(1–3):28–38. [Google Scholar]

- NVivo (Version 12). (n.d.). [Computer software]. QSR international.

- OECD Health at a glance. 2020. https://www.oecd.org/health/health-at-a-glance-europe/

- Pell D., Mytton O., Penney T.L., Briggs A., Cummins S., Penn-Jones C., Rayner M., Rutter H., Scarborough P., Sharp S.J. Changes in soft drinks purchased by British households associated with the UK soft drinks industry levy: Controlled interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2021:372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- PHE . Public Health England; 2017. Salt targets progress report.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/765571/Salt_targets_2017_progress_report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Piazzai M., Wijnberg N.M. Product proliferation, complexity, and deterrence to imitation in differentiated‐product oligopolies. Strategic Management Journal. 2019;40(6):945–958. [Google Scholar]

- Porter M.E. 1980. Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. Competitive strategy. New york: Free. [Google Scholar]

- Porter M.E. Measuring Business Excellence; 1997. Competitive strategy. [Google Scholar]

- Samoggia A., Bertazzoli A., Ruggeri A. Food retailing marketing management: Social media communication for healthy food. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- Scarborough P., Adhikari V., Harrington R.A., Elhussein A., Briggs A., Rayner M., Adams J., Cummins S., Penney T., White M. Impact of the announcement and implementation of the UK soft drinks industry levy on sugar content, price, product size and number of available soft drinks in the UK, 2015-19: A controlled interrupted time series analysis. PLoS Medicine. 2020;17(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott C., Hawkins B., Knai C. Food and beverage product reformulation as a corporate political strategy. Social Science & Medicine. 2017;172:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scrinis G. On the ideology of nutritionism. Gastronomica. 2008;8(1):39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Scrinis G. Columbia University Press; 2013. Nutritionism: The science and politics of dietary advice. [Google Scholar]

- Scrinis G. Reformulation, fortification and functionalization: Big Food corporations' nutritional engineering and marketing strategies. Journal of Peasant Studies. 2016;43(1):17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Shekar M., Popkin B. World Bank Publications; 2020. Obesity: Health and economic consequences of an impending global challenge. [Google Scholar]

- The Caterer https://www.thecaterer.com/ n.d.

- The Grocer https://www.thegrocer.co.uk/ n.d.

- Turner C., Kadiyala S., Aggarwal A., Coates J., Drewnowski A., Hawkes C., Herforth A., Kalamatianou S., Walls H. 2017. Concepts and methods for food environment research in low and middle income countries. Technical brief, agriculture, nutrition and health academy food environments working group on innovative methods and metrics for agriculture and nutrition, London. [Google Scholar]

- UK Government Sugar reduction: Responding to the challenge. 2015. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/324043/Sugar_Reduction_Responding_to_the_Challenge_26_June.pdf

- UK Government Childhood obesity: A plan for action. 2016. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/546588/Childhood_obesity_2016__2__acc.pdf

- UK Government Soft drinks industry levy. 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/soft-drinks-industry-levy/soft-drinks-industry-levy

- UK government Tackling obesity. 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/tackling-obesity-government-strategy

- Van Valen L. The red queen. The American Naturalist. 1977;111(980):809–810. [Google Scholar]

- Veeman M. Policy development for novel foods: Issues and challenges for functional food. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics/Revue Canadienne d’agroeconomie. 2002;50(4):527–539. [Google Scholar]

- Whalen R., Harrold J., Child S., Halford J., Boyland E. The health halo trend in UK television food advertising viewed by children: The rise of implicit and explicit health messaging in the promotion of unhealthy foods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018;15(3):560. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15030560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.