Abstract

Introduction

NUT (nuclear protein of the testis) carcinoma (NUTca) is a rare and aggressive cancer that is genetically hallmarked by a chromosomal abnormality in the NUT gene, and presents with tumors in the head, neck, and lungs. Currently there is no standard of care, but patients may undergo surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy. There is a lack of published research describing the patient experience of NUTca. The objective of this study was to develop a conceptual framework (CF) that describes patients’ experience of NUTca to inform the selection of outcome measures and design of patient-centric endpoints for future clinical research.

Methods

Individual, semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted with patients and caregivers of patients who have/had NUTca (caregivers interviewed due to recruitment challenges resulting from the rarity of NUTca). Participants were asked about their disease symptoms, impacts, and treatment experience. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using inductive coding. The CF was developed through inductive categorization of concepts, sub-domains, and domains.

Results

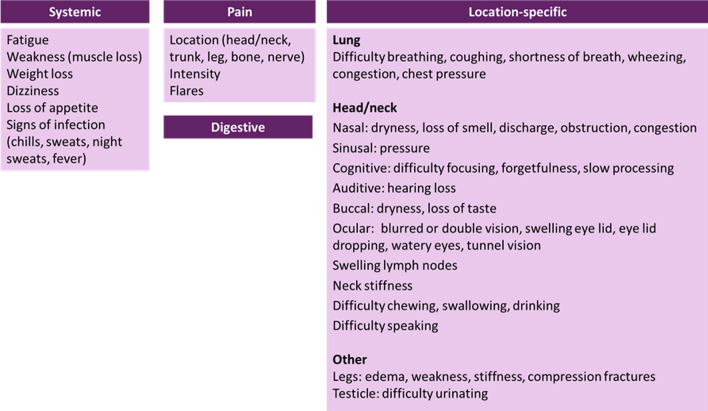

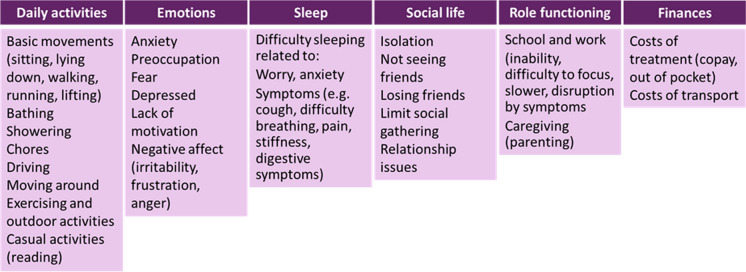

Twenty-seven interviews were completed (patients n = 10; caregivers n = 17). Participants reported systemic symptoms (e.g., fatigue) and symptoms related to the location of the tumor (e.g., nose blockage for head/neck tumor). Pain emerged as an important and bothersome symptom across tumor locations. Participants reported impacts on their daily activities (e.g., showering), emotions (e.g., preoccupation), sleep, social life (e.g., isolation), roles (e.g., caring for children), and finances. The final CF was organized into four symptom domains [systemic, location-specific (head/neck, lung), pain, and digestive] and six impact domains (daily activities, emotional, sleep, social, role, and financial).

Conclusions

This study describes the patient experience of NUTca and proposes an evidence-based CF that informs both the clinical community’s understanding of the disease and selection of a patient-reported outcome (PRO) measure to assess treatment benefit in future NUTca trials.

Keywords: NUT carcinoma, Patient-centered, Patient-reported outcomes, Qualitative research, Rare diseases

Key Summary Points

| This was a qualitative research study with semi-structured, one-on-one interviews with patients with nuclear protein of the testis (NUT) carcinoma and informal caregivers. |

| NUT carcinoma is a rare and newly established cancer occurring in relatively young patients (median age 16–21.9 years) for which there are no existing standards for treatment; median overall survival is 6.7 months from diagnosis. |

| Published qualitative literature describing the patient experience of NUT carcinoma is crucial to increase understanding of the condition, particularly given the rapid growth of tumors and associated symptoms and impacts; literature on NUT carcinoma is scarce. |

| Conceptualizing the patient experience is challenging due to the heterogeneity of the condition; our conceptual framework for NUT carcinoma based on patient interviews describes location-specific symptoms, pain, and systemic effects (e.g., weakness, fatigue, and weight loss). |

| Locations of NUT carcinoma tumors were variable (lung, head and neck, and other) as were affected symptoms and impacts experienced. |

| The resulting conceptual framework provides an evidence base for selecting patient-reported outcome measures and designing patient-centric endpoints in future trials to evaluate the benefit of new therapies. |

Introduction

NUT (nuclear protein of the testis) carcinoma (NUTca) is a genetically defined epithelial malignant neoplasm hallmarked by chromosomal rearrangement of the NUT gene. Also known as NUT midline carcinoma, NUTca can grow anywhere in the body, but it is mainly present in the midline supradiaphragmatic structures (head, neck, and lung). The sinonasal area is the most common midline tumor site. The true incidence and prevalence of NUTca is unknown, as the disease remains undiagnosed or misdiagnosed given its rarity. Only a minority of cases are diagnosed with NUTca at the beginning of the disease, while the most common incorrect diagnoses are “poorly differentiated carcinoma” or “poorly differentiated squamous carcinoma.” However, given the increased awareness and availability of easily applicable diagnostic tests, NUTca has been detected more frequently in the past decade, most specifically in adults [1–3]. In the small samples of patients studied, the median age at diagnosis ranges from 16 [2] to 21.9 years [3], but NUTca has been reported in patients aged 0.1–81.7 years [2–4].

NUTca runs a devastating clinical course. It usually presents with rapidly enlarging masses, characterized at advanced stages by early metastatic spread to either locoregional lymph nodes or less common, distant sites. Consequently, most patients present with mass-related symptoms (such as rhinorrhea, epistaxis, nasal obstruction, proptosis, diminished vision, dysphagia, persistent cough, shortness of breath, or pain), while nonspecific symptoms such as fever and weight loss have been seen only occasionally. In a cohort of 54 patients, the median overall survival was 6.7 months, with only 19% (CI 7–31%) of patients alive after 2 years [2].

Currently there is no standard of care for NUTca. Patients may undergo surgery, radiation therapy, and/or chemotherapy, although there is no evidence of the effectiveness of these treatments. These treatments have symptomatic adverse events of varying severity and impact on quality of life.

While increased survival is the primary goal, the symptomatic experience of patients and their functional status are also essential to inform our understanding of the benefit–risk profiles of therapies in development and address a high unmet need to better care for this vulnerable patient population. This study is, to our knowledge, the first attempt to conduct research directly with NUTca patients and their caregivers. No qualitative research manuscripts describing the experience of patients with NUTca were retrieved, and limited information was found on Facebook support groups or medical association websites. Additionally, there were no specific patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures identified in the literature. To provide this missing evidence, we conducted this qualitative research to describe the experience of patients with NUTca and propose a CF. The objective was to provide a first platform for an evidence base to inform the selection of outcome measures appropriate to assess the experience of patients and ensure that endpoint design in future trials is patient-centric, including methods employed in other rare disease areas as well [5].

Methods

Study Design and Procedure

As indicated by the guidance from the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the selection or development of a PRO measure should be supported by direct experience from patients [6]. We conducted semi-structured interviews using open-ended questions that allowed participants to spontaneously report their experience and that promoted discussion rather than following a prescriptive script with participants. We did not define a purposive sample with specific recruitment targets covering a range of tumor locations due to the anticipated recruitment challenges in this rare and aggressive cancer. Instead, we adopted a convenience sampling approach (using a volunteer-led online support group) while monitoring the variety of tumor locations in the sample interviewed. Given the nature of patient-centered research in rare disease [7], we also decided to interview caregivers of patients who were too sick to participate or had died, to collect their observation of the patient experience.

To participate, patients had to be 12 years old or older with a diagnosis of NUTca (either currently or in remission); caregivers had to be 18 years old or older and had to be (or have been at some point previously) a caregiver to a patient (any age) with NUTca. Both patients and caregivers had to be able to participate in one or two 1-h phone interview(s); be able to speak, read, write, and understand English; and reside in the United States. Patients treated for a cancer other than NUTca and patients or caregivers having any visual, auditory, cognitive, or language impairment that would prevent reading, understanding, or answering interview questions were excluded. Our goal was to interview n = 10 patients and n = 20 caregivers.

The semi-structured interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, with each lasting approximately 60 min. Patients and caregivers were interviewed individually, even if patients were under 18 years of age, assuming a parent or guardian was able to provide consent. There were separate patient and caregiver interview guides; both asked about the diagnostic process, symptoms experienced, and impacts of NUTca on various aspects of the patient’s daily life. The patient interview guide specifically had additional probes for in-depth descriptions of the way symptoms were experienced and about specific impacts (e.g., whether NUTca affected the way the patient thinks or communicates or affected their participation in daily activities). The caregiver interview guide had additional prompts that related to the impacts of caregiving (not reported in this manuscript). Demographic and health information was collected, including tumor location and treatments received.

Study documents were approved by a central institutional review board (Copernicus IRB tracking 20200591), and all procedures were conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines. Consent for publication was obtained. All guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and later amendments (relevant to this non-interventional, qualitative study) were followed. Patients were recruited through a NUTca Facebook support group in partnership with the moderator of the group. Interested participants completed an online screener and informed consent/consent for publication form and, if eligible, were called and scheduled for an interview. Participants received $85 for the interview.

All interviews were conducted over the phone. Interviewers were trained in Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines and had substantial experience (2+ years) conducting qualitative interviews with patients and caregivers. Additionally, all interviewers attended a mock interview to become familiar with the interview guide.

Coding and Analysis

De-identified transcripts were inductively coded and thematically analyzed [8–10]. Three researchers (AC, AL, MC) independently coded the first transcript before meeting to harmonize and create a codebook and format used for the remaining transcripts. To determine the adequacy of the sample size of participants interviewed, we performed a saturation analysis using chronologically ordered groups of five transcripts; new concepts (defined as analytical categories comprised of related codes supported by quotations) were tabulated in columns per group. Theoretical saturation had been reached and the sample size for the interviews was adequate if no new concepts emerged in the last group of five (i.e., low likelihood of new patient experience information being collected with additional interviews).

To develop the conceptual framework, codes and quotations were inductively categorized into higher-order, overarching categories referred to as concepts, sub-domains, and domains reflecting their conceptual underpinning. This involved an iterative process of cross-referencing and comparison between the different analytical categories (concepts, sub-domains, and domains) [9, 10, 11].

Results

Description of the Patients

We met our intended recruitment quota for patients with n = 10 interviews (n = 4 patients were patient/caregiver dyads). On average patients were approximately 40 years old and half were female (n = 5/10); most patients interviewed were Caucasian (n = 9/10) and married (n = 7/10), with a range of education and work statuses. None of the patients interviewed lived alone. About half of the patients (n = 6) were diagnosed with NUTca over 2 years prior to their interview; most patients reported receiving chemotherapy (n = 9/10), radiation (n = 7/10), and surgery (n = 8/10) as treatments for their NUTca tumors. Tumor location was primarily in the head/neck (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patient sample—patients (n = 10)

| Demographic information | |

| Age (mean, SD) | 38.8, 4.6 |

| Sex (n female) | 5 |

| Race (n) | 10 |

| Caucasian | 9 |

| Asian | 1 |

| Ethnicity (n) | 10 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 10 |

| Education (n) | 10 |

| Currently in high school | 1 |

| High school/GED | 1 |

| Some college | 1 |

| Associate | 1 |

| Bachelor’s | 4 |

| Postgraduate | 2 |

| Work status (n) | 10 |

| Full | 4 |

| Part | 2 |

| Retired | 1 |

| Disabled | 3 |

| Living situation (n) | 10 |

| With a partner or spouse, family, or friends | 10 |

| Health information | |

| Time since diagnosis (n) | 10 |

| Within the past 12 months | 4 |

| Over 2 years ago | 6 |

| Treatment taken (n)a | 10 |

| Chemotherapy | 9 |

| Radiation | 7 |

| Surgery | 8 |

| Tumor location(s) (n)a | 10 |

| Head | 6 |

| Neck | 3 |

| Lungs | 3 |

| Other | 3 |

| ECOG status ranking (n) | 10 |

| 0 | 2 |

| 1 | 5 |

| 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 0 |

| 4 | 1 |

aParticipants had more than one response

Description of the Caregivers

We interviewed n = 17 (/20 planned) caregivers (among them n = 4 patient/caregiver dyads).

On average, caregivers were 45 years old, mostly female (n = 15/17), and white, non-Hispanic (n = 16/17). About half of the patients of caregivers were diagnosed with NUTca more than 2 years prior to the interview (n = 8/17; includes if patients were deceased at time of interview). Like the patient sample, most patients of caregivers had received chemotherapy (n = 13/17), radiation (n = 12/17), and surgery (n = 9/17); discordantly, most patients of caregivers had lung tumors (n = 9/17) versus head/neck; there were a higher number of total tumors reported (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patient sample—caregivers (n = 17)

| Demographic information | |

| Age (mean, SD) | 44.8, 9.2 |

| Sex (n female) | 15 |

| Race (n) | 17 |

| Caucasian | 16 |

| Asian | 1 |

| Ethnicity (n) | 17 |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 16 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1 |

| Caregiver-reported patient health information | |

| Time since diagnosis (n) | 17 |

| Within the past 12 months | 6 |

| 1–2 years ago | 3 |

| Over 2 years ago | 8 |

| Treatment taken (n)a | 17 |

| Chemotherapy | 13 |

| Radiation | 12 |

| Surgery | 9 |

| Tumor location(s) (n)b | 17 |

| Head | 6 |

| Neck | 2 |

| Lungs | 9 |

| Other | 10 |

| ECOG status ranking (n) | 17 |

| 1 | 6 |

| 2 | 1 |

| 4 | 1 |

| N/A (deceased) | 9 |

aParticipants had more than one response

bOther locations included spine (5/10), pelvis (5/10), leg (2/10), hip (2/10), arm (1/10), testicle (1/10), ankle (1/10), and shoulder (1/10)

Codebook

The final codebook resulted in 270 codes describing signs and symptoms of NUTca and 230 codes describing impacts of NUTca. Codes were granular and provided nuances in the experience of associated concepts. The codes were also linked directly to the patient’s words, with as little researcher inference as possible from quote to code. Researchers, for example, coded “I feel nauseous every time I eat” as “nausea: when eating” but other codes for nausea included “nausea: new onset” or “nausea: worsens during day.” During analysis, codes were categorized into higher-level concepts (in the example provided, all grouped as “nausea”).

Codes that did not directly contribute to informing the conceptual framework of patient disease symptoms and impacts on daily life have not been retained [e.g., aspects of diagnostic history (misdiagnosed, biopsies) or burden of caregiving]. For symptomatic adverse events, we did not assume a patient’s symptoms were treatment-related unless specifically mentioned by the patient. Given that caregivers were reporting as proxies for patient experience, we did not distinguish between caregiver and patient codes in the analysis.

Symptoms Reported

Systemic (fatigue, weakness) and local symptoms were reported, dependent on tumor location: lung, head/neck, and other (included spine/back, shoulder/scapula, ankle, femur, pelvis, hip, lymph nodes, liver, arm, testicle). Severe pain was reported for all locations. Digestive symptoms were reported as well without clear association to a specific tumor location and possibly due to symptomatic adverse events (AEs) from treatment based on clinician opinion. Since digestive symptoms were not mentioned by patients as resulting from treatment, we retained them for completeness (Table 3).

Table 3.

Symptom domains, concepts, and exemplary quotations

| Domain | Concept | Exemplary quote |

|---|---|---|

| Systemic | Weakness | “Not being able to really move around to build up his muscle” “And he’s just so weak now” |

| Systemic | Fatigue | “He would sleep and sleep and sleep, and I would have to wake him up” “you constantly want to take a nap” “He just didn’t have his energy” |

| Systemic | Weight loss | “I think the weight loss shook him up a little bit “ “I want to say I lost like 20 pounds” “I think it was April, the end of April or 1st of May, she was real thin” |

| Systemic | Dizziness | “I think that was just that dizziness that he was feeling. He just kept saying he couldn’t focus. He couldn’t drive anymore.” “vertigo” |

| Systemic | Loss of appetite | “When his sodium was low … he would vomit from that. He had no appetite” “I think he had some nausea. He didn’t throw up, but he couldn’t eat” |

| Systemic | Signs of infections (chills, sweats, night sweats, fever) |

“He would have chills, so he would be very cold, and then he would break—the fever would break” “he was very like clammy to the touch, like he had like a cold sweat going constantly” “some pretty bad night sweats” |

| Lung | Difficulty breathing | "They were checking her blood oxygen, all that. She was having a hard time breathing.” “She’d have pillows like propped so she was upright. And she’d have like a humidifier going because she said that that would help.” “like a little trouble breathing, but I would say more along the lines of asthma” |

| Lung | Coughing | “It was nonstop” “it developed into violent coughing and some coughing up of blood.” “So then the cough did get more, oh, deeper, like where she was coughing so hard you thought, oh, she’s going to throw up” “dry” “a tiny little cough. It wasn’t a bad cough” |

| Lung | Shortness of breath | “I think there was some shortness of breath—or hard to breathe” “some shortness of breath with activity” “he would get winded going up and down the steps” |

| Lung | Wheezing | “I noticed myself feeling wheezy” “The wheezing—it’s just so sporadic” |

| Lung | Chest pressure | “He said he felt like someone was sitting on his chest most of the time” |

| Lung | Chest congestion | “He was experiencing chest congestion” |

| Lung | Chest swelling | “Some swelling in his neck and near his clavicle” “You could start to see some disease progression in his chest that was, again, going outward” |

| Head and neck | Nasal dryness | “He’s had some dryness” |

| Head and neck | Nasal congestion | “The sinus, he had a lot of congestion toward the end, now that I think of it. He was constantly blowing his nose, and there was some blood” |

| Head and neck | Loss of smell | “kind of lost…my…smell” “I can’t smell” |

| Head and neck | Nasal discharge | “A lot of mucus” “My nose actually, although completely plugged, would just drip like a slow, leaky faucet” |

| Head and neck | Nasal obstruction | “Nasal pressure along with blockage” “Well, the tumor was the nasal obstruction, actually” |

| Head and neck | Sinus pressure | “So again just because of where the tumor was at, in all of the sensitive areas that it was pushing on, it just again felt like just—I don’t even know how to describe it, just that area just sensitive to the touch and just achy” |

| Head and neck | Cognitive: difficulty focusing | “…he just kept saying he couldn’t focus” |

| Head and neck | Cognitive: forgetfulness | “I forget a lot of stuff” |

| Head and neck | Cognitive: slow processing | “I read a lot slow. I don’t process things the way that I did before” |

| Head and neck | Auditive: hearing loss | “Two weeks after radiation, it should be getting better, and it wasn’t. The hearing loss was worse” |

| Head and neck | Buccal: dryness | “I still have dry mouth. Inside my mouth, the sores are 90% gone.” “So with the fatiguing and all, it dries my mouth up, and then with drying the mouth up comes the shortness of breath” |

| Head and neck | Buccal: loss of taste | “I can’t taste” |

| Head and neck | Ocular: blurred vision | “He said his eyesight was getting blurry” |

| Head and neck | Ocular: double vision | “He started to see double vision” “the double vision was mostly when I looked up, down, side to side “ “the double vision was because the tumor was also behind my right eye” |

| Head and neck | Ocular: swelling eyelid | “Like someone punched me in my eye—right on top of my eye. On my eyelid, swollen.” |

| Head and neck | Ocular: eye drooping | ”So much drooping of my left eyelid that I couldn’t see…” |

| Head and neck | Ocular: watery eyes | “My eye watered” “it would never stop” “It basically acted as if I had allergies or just something where your eyes are just constantly watery” |

| Head and neck | Ocular: tunnel vision | “He said everything was just like tunnel vision” |

| Head and neck | Swelling lymph nodes | “It kept getting bigger and bigger and bigger every day” “It was like a big, huge lump” “And it was so big, it was uncomfortable for her to like turn her head” |

| Head and neck | Neck stiffness | “I also know that sitting for a long time, if I’m reading a book, and the way I sleep at night are all impacted by that stiffness in my neck” |

| Head and neck | Difficulty chewing | “If I eat any steak, that means that I’m going to have a hurting mouth for at least a week, just because of the chewing.” |

| Head and neck | Difficulty swallowing | “I’m not even able to really swallow effectively even to drink water “ |

| Head and neck | Difficulty drinking | “He had hiccups, and it would occur—it would make it difficult for him to eat or drink at times” |

| Head and neck | Difficulty speaking | “Tumor underneath his tongue was so large“ “Just within the first 24 to 48 h, he couldn’t talk. He couldn’t eat” “It was affecting his speech, like it started to sound like he had marbles in his mouth” |

| Other—site-specific | Testicle | “Hard to urinate” “hurt him when he peed” |

| Other—site-specific | Legs | “He also started having edema in both of the legs” |

| Pain | Bone pain | "He never complained about everything until he had the pain in his bones” |

| Pain | Back pain | “I had back pain” “metastasis to the spine at T7 and 8” “a lot of back pain” “pain jumps around hour by hour” “back pain around his shoulder blade” “nerve pain” “pain from his chest to his back” “It’d be a pain that radiated to your back” |

| Pain | Abdominal pain | “I had some hurting like my abdomen” “he would be standing there and just be like, damn when it hit him—in the abdomen” |

| Pain | Chest pain | “He just felt uncomfortable, like with chest pains and things” “She had a sharp pain in her chest because the thing was so big” “a little discomfort in the chest area—to not being able to lay flat on his back because of the tumors” “I had the tumor develop in my soft tissue under my left lung, I thought there’s a new pain there that’s not associated with my spine” “it was just like searing, really excruciating pain in my rib cage area” |

| Pain | Shoulder pain | “Around the scapula” “shoulder blade” “progressed from an intense aching, sharp pain, to also burning” “in the joint region, like she was thinking…did I injure my shoulder?” |

| Pain | Ear, nose, throat pain |

“I had pain above my eye, my head as well. My cheek” “A lot of pain underneath my left eye, where my cheekbone is” “the nose and the face and the forehead” |

| Pain | Headache | “Once a week” “behind eyes” “between eyes” “chronic” “come and go” “constant” “daily” “debilitating” “excruciating” “feels like somebody’s just punched him in the face” “if you took a sewing needle and just poked right in the back of your head” “throbby” “migraine” “mild” “pressure” “tight” “debilitating…just wanted to…try to sleep it away” “dull ache…across the forehead” |

| Pain | Neck pain | “For her to move her neck in certain—you know, tilt it in a certain way and move it—it was uncomfortable, and it was causing pain where the tumor was” |

| Pain | Sinus pain | “Sensitive to the touch and just achy” |

| Pain | Torso/Trunk pain | “Constant challenge with pain…around the trunk” |

| Pain | Intensity | “He ended up having really severe pain in his chest area” “my pain was to the point it was excruciating” |

| Pain | Flares | “Then I had a terrible flare up of pain” |

| Digestive | Constipation | “He had also developed constipation and was having difficulty moving his bowels” |

| Digestive | Diarrhea | “was kind of having diarrhea at the very end” |

| Digestive | Nausea | “He felt very like just nauseous” “bout of nausea” “every time I eat” |

| Digestive | Vomiting | “He couldn’t keep anything down. He was throwing up.” “had the vomiting because of the wheezing” |

| Digestive | Distension | “His abdomen was getting distended” |

| Digestive | Digestive: swelling | “I start experiencing the abdomen pain and the swelling, the fluid” |

| Digestive | Cramping | “Some abdominal cramping” “so much cramping” |

Impacts Reported

Patients reported a range of impacts on different aspects of their life: daily activities, sleep, roles, social life, and finances. Patients reported that their experience and satisfaction with and access to care were important when considering their overall experience of NUTca (not included in the framework) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Impact domains, concepts, and exemplary quotations

| Domain | Concept | Exemplary quote |

|---|---|---|

| Daily activities | Basic movements (sitting, lying down, walking, running, lifting) | “Bedridden” “severe difficulty with getting comfortable with positioning” “don’t really lift too much heavy stuff” “had difficulty lying flat” “for her to move her neck in certain…way[s]…uncomfortable” “he could barely walk” “couldn’t even walk up a flight of stairs” |

| Daily activities | Bathing | “Bathing—he was able to do a lot of it on his own, but I had to spot him to help him get situated in the tub” |

| Daily activities | Showering | “Like showering, that was the most difficult for him” |

| Daily activities | Chores | “Things just around the house…I’m not doing like painting a ceiling would be really hard…limits the amount of time I can be…doing some manual task” |

| Daily activities | Driving | “He couldn’t drive anymore” |

| Daily activities | Exercising and outdoor activities | “Outdoor activities sometimes are difficult” “I can’t do as much exercise anymore” |

| Daily activities | Casual activities (reading) | “Can’t sit in a chair very long to sew” “hard for him to read” |

| Emotions | Anxiety | “suffering from a lot of panic attacks and anxiety” “the anxiety part is awful” “overall anxiety, being afraid of it coming back” |

| Emotions | Preoccupation | “Like in the back of my mind, I’ve just got this thing, like when is a symptom going to happen again?” |

| Emotions | Fear | “Fear of dying quickly” “always afraid it’s going to come back” |

| Emotions | Depressed | “The depression had just kind of eating—eaten away. Apparently I didn’t realize it, but there’s—as much as I try, there’s nothing that I can do to get out of it” |

| Emotions | Lack of motivation | “It’s really tough just to have any kind of motivation to do anything” |

| Emotions | Negative affect (irritability, frustration, anger) | “He’s really frustrated…He kind of becomes really angry” he’s really frustrated, where he doesn’t want to talk” |

| Sleep | Difficulty sleeping related to: worry, anxiety | “It was difficult for me to sleep through the night…anxiety” |

| Sleep | Difficulty sleeping related to: symptoms (cough, difficulty breathing, pain, stiffness, digestive symptoms) | “Coughing makes it difficult to sleep” “lots of drainage in my throat, and just…it was a while before I could even lay down in my bed and sleep” |

| Social life | Isolation | “It’s incredibly isolating” “having to be isolated” |

| Social life | Not seeing friends | “She wasn’t seeing any of her friends at all” |

| Social life | Losing friends | “Withdrawn from my friends…because they don’t know what to say” |

| Social life | Limit social gatherings | “There were weddings that we weren’t able to go to” “we don’t have the social life that we used to…it’s pretty much nonexistent” |

| Social life | Relationship issues | “Uncertainty about her partner” “I had a friend group in middle school, and I don’t know really what happened. Right after I finished chemo, they didn’t like me anymore.” |

| Role functioning | School and work (inability, difficulty to focus, slower, disruption by symptoms) | “The clinic’s only open until 4:00…I’ll get off at 5:00 at my job…how am I going to make this work?” “…started to get really difficult to focus on work” |

| Role functioning | Caregiving (parenting) | “Really difficult even to just take care of my [son]—to have the energy to do that” |

| Finances | Cost of treatment | “And the insurance didn’t pay for—my deductible was over $4000 a year. So I’ve been $4,000 in debt each year for—I had to draw money out of savings to be able to pay it” |

| Finances | Cost of transport | “And then the transportation back and forth to the hospital and then the parking…it’s a fortune” |

Saturation of Concepts

Most of the concepts arose in the first 20 transcripts; in the fifth group of five transcripts, the only concepts reported related to hearing problems, forgetfulness, slow processing, and difficulty urinating. No new concepts emerged in the last two transcripts. These results indicated that conceptual saturation was acceptable in the sample interviewed and that the sample size was sufficient despite the heterogeneous nature of the condition.

Conceptual Framework

The CF was organized into four symptom domains (systemic, location-specific, pain, and digestive) and six impact domains (daily activities, emotions, sleep, social, role, and financial). Some social life impact concepts (isolation, not seeing friends, and limited social gatherings) may be related to AEs of treatment (Figs. 1, 2).

Fig. 1.

Symptom conceptual framework

Fig. 2.

Impact conceptual framework

Discussion

Most patients interviewed had tumors in the head, neck, or lungs, which based on the epidemiology of NUTca are the most frequently reported tumor sites [12]. Importantly, the few concepts on the experience of patients retrieved from the review of the limited available literature and clinical sources were expanded by the patient interviews. The comprehensiveness of the findings was difficult to evaluate since NUTca has many possible tumor site locations, presents differently depending on tumor location, and spans across age groups; given the rarity of NUTca, purposive sampling methods to account for a full range of experiences was difficult. However, given the acceptable saturation of concepts in the sample interviewed, the sample size was deemed sufficient to draw conclusions on the experience of patients with the most frequent tumor locations (head/neck and lung).

Our choice to use caregivers as proxies for patients was justified by anticipated recruitment challenges and feasibility of interviewing patients with hard-to-reach, rapidly progressing, rare carcinoma; this methodology serves as an example of the needed pragmatism and practical considerations of conducting research in similar populations. We found that the caregivers were extremely involved in the lives of patients (or previously were if patients were deceased) and provided useful information on the experience of patients. We did not analyze patients and caregivers separately due to the small sample size but acknowledge the potential differences between caregiver reporting and patient reporting. Over half (6/10) of the patients interviewed can be considered long-term survivors in comparison to the medium short life expectancy in NUTca. Due to the small sample size, no analyses comparing subgroups of patients according to the time since diagnosis were performed. This may call into question the generalizability of our findings, but in rare conditions, research design and analysis must be pragmatic in order to accumulate evidence to serve the research objectives [13].

One of the biggest challenges was creating a CF for a disease with such heterogeneity of reported concepts given the varying tumor locations; our goal was to create a CF that captured the patient experience of NUTca in a comprehensive way; this will allow researchers designing trials for NUTca to ensure that outcome measures are reflective of the experience of patients and that treatment benefit can be meaningfully interpreted in the context of this experience. We chose to separate the location-specific symptoms and impacts in order to create a CF that could potentially be updated with new tumor locations as add-ons, without questioning its structure. This CF can serve as a foundation and potentially maximize efficiency for future clinical research as further information is gathered on the experience of NUTca. As more clinical and patient experience data become available, the typicality of some concepts included in the current framework for comprehensiveness can be reviewed.

Pain emerged as a unique domain because of its importance in the experience of patients. Pain was reported for many tumor locations, but also as “radiating” to other parts of the body, making it sometimes difficult to pinpoint. To reflect the experience of patients and ensure its proper assessment, pain was proposed as a separate domain relevant across locations rather than being integrated with location-specific symptom domains. Further information on the patient experience of pain is warranted.

Conclusions

This qualitative research generated valuable information on the symptoms and impacts on daily life experienced by patients with the most frequent locations of NUTca. The resulting CF provides an evidence base for selecting patient-reported outcome measures to evaluate the benefit of new therapies and for designing meaningful endpoints for future clinical trials. This research illustrates how in rapidly progressing disorders such as NUTCa with diverse locations and manifestations, a patient-centric approach can be used to inform decisions [7]. We structured the framework to account for location-specific symptoms and to allow for the addition of concepts relevant to the patient experience of NUTca that were not captured based on the patient sample interviewed in this research.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of this study as well for providing us with information about their experience.

Funding

Boehringer Ingelheim funded this study, including the Journal’s Rapid Service Fees, and worked with Modus Outcomes on the design and development of this manuscript.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Anders Ingelgard (review), Madison Castle (coding), and Adele Levine (coding).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship contributions

Researchers Farrah Pompilus and Anna Ciesluk were responsible for interviews, coding, and analysis. Patrick Marquis, Ingolf Griebsch, and Marten Voorhaar reviewed data and synthesized results to form conclusions.

Disclosures

Modus Outcomes conducted this research sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Study documents were approved by a central institutional review board (Copernicus IRB tracking 20200591), and informed consent was obtained for all participants. Consent for publication was obtained. All guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and later amendments (relevant to this non-interventional, qualitative study) were followed.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they are qualitative transcripts and cannot be completely de-identified.

Contributor Information

Farrah Pompilus, Email: Farrah.pompilus@gmail.com.

Anna Ciesluk, Email: anna.ciesluk@modusoutcomes.com.

Patrick Marquis, Email: patrick.marquis@modusoutcomes.com.

Ingolf Griebsch, Email: ingolf.griebsch@boehringer-ingelheim.com.

Maarten Voorhaar, Email: maarten.voorhaar@boehringer-ingelheim.com.

References

- 1.Napolitano M, Venturelli M, Molinaro E, Toss A. NUT midline carcinoma of the head and neck: current perspectives. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:3235–3244. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S173056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer DE, Mitchell CM, Strait KM, Lathan CS, Stelow EB, Luer SC, et al. Clinicopathologic features and long-term outcomes of NUT midline carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(20):5773–5779. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chau NG, Hurwitz S, Mitchell CM, Aserlind A, Grunfeld N, Kaplan L, et al. Intensive treatment and survival outcomes in NUT midline carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 2016;122(23):3632–3640. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.French CA, Kutok JL, Faquin WC, Toretsky JA, Antonescu CR, Griffin CA, et al. Midline carcinoma of children and young adults with NUT rearrangement. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(20):4135–4139. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon A, Pompilus F, Querbes W, Wei A, Strzok S, Penz C, et al. Patient perspective on acute intermittent porphyria with frequent attacks: a disease with intermittent and chronic manifestations. Patient. 2018;11(5):527–537. doi: 10.1007/s40271-018-0319-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: guidance for industry. 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/131230/download. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Morel T, Cano SJ. Measuring what matters to rare disease patients–reflections on the work by the IRDiRC taskforce on patient-centered outcome measures. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12(1):171. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0718-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–90. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bryman A, Burgess B. Analyzing qualitative data. New York: Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bowling A. Research methods in health: investigating health and health services. 3. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klassen A, et al. Satisfaction and quality of life in women who undergo breast surgery: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2009;9:11–18. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Cancer Institute. NUT Carcinoma. 2020. https://www.cancer.gov/pediatric-adult-rare-tumor/rare-tumors/rare-soft-tissue-tumors/nut-carcinoma.

- 13.Morel T, Cano SJ. Measuring what matters to rare disease patients- reflections on the work by the IRDiRC taskforce on patient-centered outcome measures. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:171. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0718-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they are qualitative transcripts and cannot be completely de-identified.