Abstract

Background

Young people in secure services present with multiple vulnerabilities; therefore, transition periods are especially challenging for this group. In this study, we followed up young people discharged from adolescent medium secure services to adult and community settings with the aim to explore transition experiences and outcomes.

Methods

Participants were recruited from 15 child and adult mental health services in England. We conducted qualitative semi-structured interviews with 13 young people, aged 18–19 years, moving from adolescent medium secure units 2–6 months post-transition, and five carers 1–3 months pre-transition. Thematic analysis was performed to identify predetermined or data-driven themes elicited from face-to-face interviews.

Results

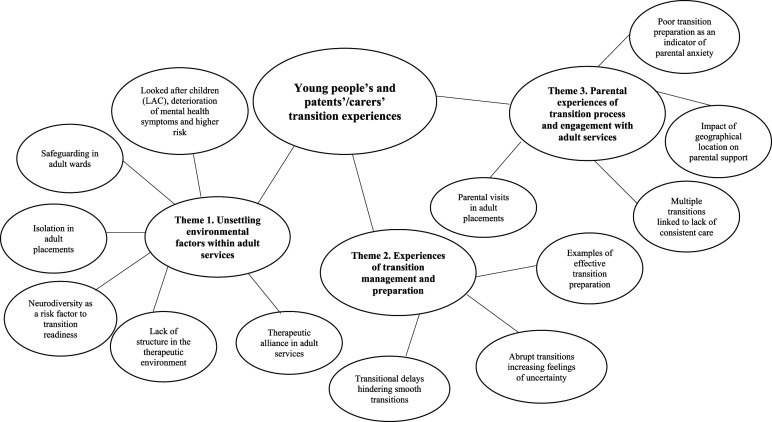

The findings indicated poor transition outcomes for young people with the most severe mental health symptoms and those who committed serious offences. Three overarching themes were identified: (1) unsettling environmental factors within adult services; (2) experiences of transition management and preparation and (3) parental experiences of transition process and engagement with adult services.

Conclusion

The findings of this study indicate that young people and carers value ongoing involvement in the transition process by well-informed parallel care. They also highlight the need for a national integrative care model that diverges from the traditional ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach.

Keywords: Young people, child and adolescent medium secure services, poor transition, discharge destination, integrative care

Introduction

Adolescents experience a number of emotional, cognitive and biological developments before adulthood (Singh et al., 2008). Young people with mental health problems encounter additional difficulties during this period due to the interface of traversing multiple services and the emergence of presenting complex needs. Those in adolescent secure services with ongoing mental health problems and presenting risk to self and/or others and offending behaviour are considered one of the most challenging groups (Campbell et al., 2014). Furthermore, those in secure settings are found to have unique and elevated care needs, with significantly higher levels of mental health disorders, emotional dysregulation, emerging personality disorders and neurodevelopmental needs compared to adolescents within the community (Hales et al., 2018).

Recent reports have commented on young people’s needs in adolescent inpatient services and have highlighted that stability and security offered in these child-oriented services are the most recurrent themes associated with positive transition outcomes (Wheatley et al., 2013). Healthcare professionals refer to difficulties of young people separating from adolescent services and adult services’ lack of confidence in responding properly to this group’s set of needs (Kane, 2008). As such, the culture difference between child and adult mental health services may be accountable for poor transition outcomes. Adolescent secure services are designed around a trauma-attachment model embedding the developmental perspective, which addresses their current needs while adult services are tailored around a more independent treatment style (Hill et al., 2014).

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2016) guidelines highlight that young people need to be central in any decision-making, and that this should be a shared process. The National Health Service (NHS) outlines within its Five Year Forward View (National Health Service, 2014) that mental health services should strive for ‘personalised care’ and co-production, whereby individuals are empowered using a strength-based approach. Within this approach, statutory services need to recognise the importance of family, carer and community support when promoting health, well-being and recovery outcomes for patients.

The importance of joint decision-making and familial involvement within mental health services is evidenced in an extensive literature review by Kelly and Coughlan (2019). Parental involvement in the youth mental health recovery process was identified as the most important theme (Kaplan & Racussen, 2013). However, previous findings from mainstream Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) show that shared decision-making is not standard practice (Paul et al., 2015). Such evidence highlights the importance of including parents and wider support providers when reviewing, designing and implementing mental health service provisions for young people.

Aims of the study

Young people’s subjective experiences are overlooked in the extant literature and, therefore, we do not fully understand their needs during periods of transitions from child to adult mental health services. It is evident from the outlined literature that more research is needed to investigate the unique lived experiences of young people within secure settings, to gain an in-depth understanding of the transition outcomes for this group. This research aims to fill this gap while informing policy and treatment improvement within mental health services. Services can use this information to help promote individualised, person-centred care, which the NHS aspires to adopt service-wide.

This study aimed to reflect on the experiences of young people and their families transitioning from all nationally commissioned medium secure services in England and receiving adult and community services. Using semi-structured interviews, we aimed to explore the transition experiences of young people and carers, to understand what aspects of the transition process worked for them and what did not.

Methods

Procedure

We conducted 18 qualitative semi-structured interviews with 13 young people and five parents/carers. Purposive sampling was applied by identifying potential participants in a consecutive manner. Young people and carers were recruited from all six nationally funded medium secure services for adolescents in England aiming for a diverse sample of young people in secure hospitals. The principal researcher (ML) visited all sites to introduce the study and meet with local collaborators and the multidisciplinary team (MDT). The responsible clinicians (RCs) who acted as local collaborators informed the principal researcher about participant eligibility and arranged meetings with the adolescents on the wards to explain the study objectives. The RCs invited parents/carers via post or email to participate. All local collaborators (five consultant forensic psychiatrists and one consultant forensic psychologist) completed a mapping exercise a priori regarding the number of young people eligible to transition within the next 6–9 months. The mapping tool was distributed to local collaborators between May 30th, 2016 and November 30th, 2016 and collected information about annual transition caseloads, demographics of the cohort and standard transition preparation procedures (Livanou et al., 2020). The same mapping exercise was used in the TRACK study which is the largest UK study exploring transition outcomes from mainstream CAMHS to adult-oriented settings (Singh et al., 2008). Participants were followed up at selected adult services based on young people’s transition destination at the time of the interviews (December 2016–June 2017).

Participants and recruitment

Young people

The target sample of young people was recruited from adolescent medium secure services meeting the inclusion criteria:

(a) be close to the age transition boundary to move to adult services 17.5–18 years;

(b) be beyond the age transition boundary to adult services 19 > 18 years and

(c) have capacity to consent in writing.

Participants in the acute phase of their mental illness were excluded. Participant demographic, index offence and clinical characteristics are summarised in Tables 1 and 2. Two adolescent medium secure units admitted young people with specialised needs. Seven young people were diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and five with a learning disability (LD). Seven participants presented with multiple comorbidities and complex needs including emerging borderline personality disorder (BPD), psychosis, schizoaffective and bipolar affective disorder. The names of the wards are not included in this article to maintain confidentiality, specifically to protect the participants’ identities considering the small numbers admitted to these units.

Table 1.

Demographic information for young people participants.

| Gender | |

| Female | 4 |

| Male | 9 |

| Age (n = 13) | Mean (SD) |

| 18.85 (.38) | |

| Ethnicity | |

| White/caucasian | 12 |

| Black | 1 |

| Mixed | 1 |

| Index offence | |

| Murder | 1 |

| Body assault | 8 |

| Sexual assault | 1 |

| Arson | 1 |

| Risk | 2 |

Table 2.

Cases of young people interviewed within 5 months of their transition between January 2017 and December 2017.

| Case | Evidence of joint working | Diagnosis | Transition destination | Parent interviewed | Transition outcome a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joanne | No | Emerging BPD | Community setting | No | Poor |

| Miriam | Yes | Schizophrenia and personality disorders | MSU | No | Poor |

| Ruth | Yes | ASD | MSU | Yes | Poor |

| Kelly | No | Emerging BPD | MSU | Yes | No transition |

| Mike | No | ASD and psychotic episode | HSU | No | Poor |

| Kenny | Yes | Asperger’s syndrome, mild LD and bipolar affective disorder | Community forensic unit | No | Good |

| William | No | Bipolar affective disorder, mild LD and ASD | MSU | Yes | Poor |

| Noah | Yes | Emerging ASPD and mild LD | LSU | Yes | Good |

| Elijah | Yes | Schizophrenia | MSU | No | Ok |

| Ethan | No | Schizoaffective disorder, mild LD and ASD | MSU | No | No transition |

| Ben | No | ASD | MSU | No | Poor |

| Liam | Yes | ASD | LSU | No | Good |

| Henry | No | Bipolar affective disorder and mild LD | MSU | No | Poor |

HSU = high secure unit; MSU = medium secure unit; LSU = low secure unit; BPD = borderline personality disorder. ASD = autism spectrum disorder; ASPD = antisocial personality disorder; LD = learning disability.

aTransition outcome was determined according to interview content, self-reported experiences, reflective summaries and researcher’s observations during the interviews. In addition, the Responsible Clinicians’ input was considered to report transition outcomes based on symptom severity, therapeutic alliance and treatment engagement in adult services.

The sample moved to adult services at different times and follow-up visits ranged between 2 and 6 months post-transition. Interviewing young people post-transition helped to explore similarities and differences in care pathways. The principal researcher (ML) met with each young person before their prospective transition to establish rapport and receive consent and after their transition to adult services to reflect on recent experiences. The follow-up period facilitated understandings of transition outcomes. Two participants had not moved by the study’s end date due to multiple complexities based on their mental health and legal status, and infrastructural weaknesses in adult services (e.g., lack of bed availability). Therefore, these patients were visited again in adolescent medium secure units to understand the impact of transitional delay. The remaining 11 young people moved to nine different adult placements including low, medium and high secure services, community support accommodations and forensic community mental health teams. The adult placements were in nine different geographical locations, with four young people not returning to their catchment area due to lack of available services in the region. Table 2 displays participants’ discharge characteristics and transition outcomes determined based on interview content, self-reported experiences, reflective summaries and researcher observations during the interviews. Additionally, the RCs’ input informed our reports about transition outcomes related to symptom severity, therapeutic alliance and treatment engagement in adult services.

Families and carers

Five parents/carers who were preferably primary carers and/or had been or were living with the young people were recruited. All interviews were audio-recorded and participant names were pseudonymised at the point of transcription for confidentiality purposes. Parents/carers were interviewed 1–3 months pre-transition to ensure involvement in the study. Parents/carers are more likely to engage in young people’s treatment while they are still in CAMHS. Accordingly, RCs in adolescent medium secure units had built rapport with parents/carers and had the opportunity to encourage study participation.

Materials

Semi-structured interviews were used to explore key themes and to allow for themes to be generated by the respondents. The interview topic and question guides were developed in line with the TRACK study (Singh et al., 2008). The interview schedules were piloted with staff members and service users from the lead participating site (adolescent medium secure service). Interview schedules for parents/carers asked about their experiences with forensic child and adolescent services and how they were informed about their child’s prospective transition. The interviews with the young people pertained to their experiences with both services.

Data analysis and interpretation

The principal researcher (ML) developed a codebook including encoded and predetermined terms such as liaison among services, referral criteria, barriers/facilitators to transition, transition preparation, emotional readiness, waiting time, service satisfaction, transition barriers/facilitators, family involvement, continuity of care and service coordination. The codes determined a priori were in line with previous research on transitions (Singh et al., 2008). This codebook was revised by SS (co-author and supervisor researcher), ML and a third reviewer (second supervisor of the study) during the interview period and the codes were refined using a reflexive approach. This allowed the in-depth exploration of all topics brought up by young people (Shaw, 2010). After interviewing each young person, a reflective summary was written up based on the semi-structured interview to contextualise the data. The reflexive approach promoted self-awareness of power dynamics, biases and facilitated in-depth understandings. This process enhanced the validity of the research findings in the interpretation stage.

The codes were aligned with themes elicited in the TRACK study, and a peer-debriefing followed in which codes were adjusted to fit in forensic transitions. The principal researcher conducted line-by-line coding independently by constant comparisons of similarities and differences across the 18 transcripts. The transcripts were checked against the audio-recorded interviews to ensure accuracy. Thirty percent of the transcripts were coded independently twice to minimise any potential biases and focused on reflecting the transition experiences of young people and carers. Cohen’s kappa inter-rater reliability across two raters (ML and SS) was .84 which measured agreement between coders. Inter-rater reliability was based on code frequency (unit of analysis) and whether a code was present or absent. Discrepancies were discussed between the two raters and resolved through reflecting on post-interview interpretation of the data with the participants. When the two coders agreed, the final definition of the code was assigned. Before coding, ML discussed and reflected on transition key themes with the parents/carers and RCs post-interview to ensure credibility. There was concept of consistency between participants and researchers. Coding reflected the transition experiences and perceptions of young people and parents/carers. The codes were turned into themes which reflected the data and were reviewed and refined by the two coders.

The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed using thematic analysis as proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006). Where interview recording was not possible due to ward restrictions (n = 4), detailed field notes were taken instead during interviews. Detailed field notes included participants’ demographics, geographical location, clinical diagnosis and transition experiences. Nonverbal behaviours were documented and reported in the reflective summaries. Reflective summaries were written immediately post-interview and entailed the researcher’s personal thoughts and critical reflections (e.g., biases and feelings). Field notes provided contextual depth and enriched data analysis and were integrated with interview data. The content was reported in the transcripts. The principal researcher (ML) discussed the content and interpretation of field notes with the co-researcher of the study (SS) to minimise biases and facilitate reflexivity.

Transcripts were read multiple times to identify emerging patterns and trends including differences, similarities, contradictions, repetitions, summaries and use of language (Pope et al., 2000). The principal researcher became familiar with the data and then transcribed and reread the dataset multiple times. Finally, agreed themes were linked to corresponding quotes. Constant comparison between old and new themes took place with an ‘audit trail’, where all decisions and activities were documented to enhance trustworthiness and minimise researcher bias. The detailed field notes for the four interviews were summarised manually using a reflective approach and then imported to MAXQDA software where the same coding and analysis procedures were followed.

A contextualist approach was used as the main epistemological position, which lies in between constructionism and essentialism, as proposed by Braun and Clarke (2006). Adolescent secure hospitals provide confined settings which can impact young people’s mental health and feelings of safety considering they are exposed to additional risks including bullying, isolation and anxiety (constructionist approach based on subjective experiences). From an essentialist perspective, young people are detained under the legislation of the Mental Health Act either due to high-risk presentation or to offending, which reflects the objective reality.

Ethics

HRA ethical approval for the study was granted in January 2016. All parties involved in this research have provided written consent.

Results

Overview of themes

Participants’ transition experiences were reflected on three overarching themes (displayed in Figure 1): (1) unsettling environmental factors within adult services, (2) experiences of transition management and preparation and (3) parental experiences of transition process and engagement with adult services.

Figure 1.

Thematic map with the main themes and subthemes found in thematic analysis of interview transcripts.

Theme 1: Unsettling environmental factors within adult services

It was understood that young people had negative experiences within adult services, mainly due to unsettling factors within adult services.

Safeguarding in adult wards

Four young people reported feeling unsafe in adult secure hospitals and being the youngest on the ward. Parents/carers expressed similar views regarding appropriateness of adult placements. These young people had been in contact with CAMHS from an early age and had also been admitted to an adult hospital due to shortage of beds in child and adolescent inpatient services.

‘There is one guy bullying me. I am worried this will affect my progress...I have told staff and they said they will help me file a formal complaint. I have told my parents. My parents are trying their best with this’ (William).

Isolation in adult placements

Being surrounded by older peers was described as a main barrier to adjustment in adult placements. Young people felt isolated on adult wards and had fewer social interactions with peers they could relate to.

‘The other patients are much older in the ward. There are 8 patients in this ward. I am the youngest. I would prefer to be with younger people…There are two people I like; yes, they are really nice’ (Ethan).

Young people with comorbid mental health problems, neurodevelopmental needs and emerging personality disorder traits reported feeling alienated from their older peers on the ward due to the large age gap.

‘However, most people here like to keep themselves for themselves. You know they all have ASD or Asperger’s that falls in the spectrum and I know lots about ASD, I have read, and I understand why they like to be alone’ (Liam).

Young people reported that they could not adjust to adult hospitals due to different institutional circumstances. Their experience of hospital was likened to incarceration given the lack of freedom. There was lots of noise throughout the day and older peers wandering around without being occupied in activities and/or treatment.

‘It’s like being in prison; I can’t do anything here-it’s like they hold on to me...it is too loud here, and I want a quieter place and I want to move on with my life’ (Henry).

Neurodiversity as a risk factor to transition readiness

Parents/carers expressed concern over the comorbid needs of their children, for example, ASD, learning disability and mental health problems, and concerns over their developmental readiness to be in adult services. Young people lacked developmental readiness, especially those with learning disabilities and ASD, as well as close and structured support. These individual- and institutional-level factors sometimes manifested through violent incidents on the ward and self-harm behaviours, according to parent reports. Two of the participants could not be seen the first time visited for interviews in adult services because they were in seclusion after engaging in self-harm and/or being involved in physical fights with other peers.

‘They haven’t told me where he is moving and because he has ASD and a learning disability and a mental disorder, he is very vulnerable. I don’t think he’s ready to be surrounded by adults’ (Parent 3).

One parent was particularly concerned about their son’s prospective transition to an adult placement and the effects of this transfer on his mental health. This parent emphasised that the institutional change would worsen his symptoms, given the falling away of more intensive and structured support.

‘My child has a learning disability and chronologically might be an adult but emotionally is like 12 years. This is my real worry going to an adult ward. He needs people to be there, he needs a lot of structure, a lot of support. I don’t think he is ready to move to adult services. When he goes to a new place makes the worst thing to happen to feel safe’ (Parent 2).

Lack of structure in the therapeutic environment

The majority of the young people stated that they had much more free time and independence in adult services and they were involved in fewer or no activities in the routine days. Adolescent secure services provided a daily-structured routine including education, therapy and ward activities.

‘I like it here [adult service] better; I’m watching tv all-day because in child you know I had all these things to do. I have freedom now.’ (Elijah)

‘Not much going on really. I do some sports; it’s all I’m doing sports. I do rugby training and I do football sometimes. Most of the time I stay in my room and play my game because the ward is tiny and there’s so much going on’ (Ben).

Therapeutic alliance in adult services

Young people described their relationship with adult healthcare staff as infrequent and distant. They spent less therapeutic time with clinicians compared to child and adolescent services.

‘My new RC seems really nice, but I have met her only a few times during some Friday sessions’ (Mike).

The same patient reported that it was difficult to communicate with healthcare staff on the ward because they had limited understanding of his needs due to his autism. This was corroborated with his clinical team. In addition, this young male had committed a serious offence which had caught the attention of his peers in the adult ward.

‘I don’t think they know me here like in child services. They don’t understand what and when I want something or even when I’m joking’ (Mike).

Looked after children, deterioration of mental health symptoms and higher risk

One young person with psychotic symptoms and emerging personality disorder traits moved to an adult medium secure unit where their symptoms worsened and risk increased. The interview with this young female was brief due to deteriorating mental health status. The RC in adult services reported that the patient had become more violent and had to stay in seclusion for a long period to minimise risk and harm towards self and/or others. This young female had not adjusted well on the adult ward and would often pose other patients at risk as a result of her violent outbursts.

‘I didn’t want to move here…I don’t understand why…’ (Miriam). This quote was documented in field notes.

Theme 2: Experiences of transition management and preparation

Interviews with the young people revealed that, overall, there is poor transition preparation leading to delays.

Transitional delays hindering smooth transitions

Transitional delays occurred for a number of reasons including shortage of beds in adult hospitals, community services unable to respond to high-risk cases and changes in risk level. One young person was anticipating her transition for 10 months but due to several complications in her case such as neurodevelopmental needs, the discharge destination was still unknown when she was visited. Her engagement in the interview was minimal and the only theme that was repeated was her resentment of being detained in secure services. This young female was particularly still and quiet throughout the interview and seemed disengaged and lost. The data for this interview were captured from field notes.

‘I don’t know when I am moving. I’m not sure...I don’t feel anything. I don’t want to be in hospital, so I don’t care’ (Kelly).

Abrupt transitions increasing feelings of uncertainty

Based on the principal researcher’s observations and discussions with the RCs (psychiatrists) in adolescent secure services, the majority of young people were distressed about their prospective transitions and about a third did not know the specific details of their transfer to adult services due to ongoing complications with their case. This was also evident during the interviews where young people appeared agitated when referring to their transitions Supplementary Material.

Lack of preparation and support for prospective transitions to adult services was a strong recurring theme. Young people echoed their frustrations due to the service barriers they encountered while waiting to be moved from adolescent medium secure services. They expressed resentment about not being prepared for the upcoming transition and pointed to the lack of proper transition planning.

‘They don’t prepare you at forensic child services, they just tell you where you are moving…and you don’t get to visit the new place…’ (Mike).

The following young male felt unprepared and quite frustrated throughout the process. He presented with high risk to others and autistic traits and had committed a serious offence; often he would threaten staff members in adolescent services reflecting their uncertainty and lack of containment.

‘Two weeks before they told me. Where am I going? You’re going to X hospital. Then they brought me straight down here by car. That’s when they told me’ (Henry).

Examples of effective transition preparation

However, four young people had visited the place before their transition and had met with the key workers at the adult setting. Those young people who moved to the community and presented with less risk had the opportunity to use extended leave and stay overnight at the adult placement before their final discharge from adolescent medium secure services. This gradual transition process seemed to provide young people with a sense of agency and familiarity with the new environment that might not otherwise exist.

‘It was really good that I got to stay in the new placement for a 4-week period to see if I liked it or not and also got to know the staff and the people here and could get used to them’ (Kenny).

Theme 3: Parental experiences of transition process and engagement with adult services

Parents/carers were deeply involved in the transition process; similar to young people they have their own challenges. They have expressed their anxiety regarding the readiness of their child.

Multiple transitions linked to lack of consistent care

The five parents/carers included in this study had all experienced multiple transitions across services being involved in their children’s complex care pathways and transitions to adult services. Parents described having a positive relationship with the RC from adolescent services while these therapeutic dynamics shifted once the young person moved to adult services.

‘My child moved to a community placement near home and we were very happy in the beginning. But then they told us she has to move back because they can’t manage her risk and needs support in her everyday routine… (Parent 1).

Poor transition preparation as an indicator of parental anxiety

Parents/carers expressed anxiety about their children’s prospective transitions. They were concerned about not being well informed and not being sufficiently involved in the process. One parent felt extremely worried about their child being in limbo and waiting for months to be moved. The major concern was about the identified-suggested adult placement that had not formally accepted the young person and the suitability of this service for the vulnerable service user. The family carer felt that this placement would worsen the young person’s mental health symptoms and they would not cope in an adult environment due to their developmental age.

‘I don’t want her to go into that adult placement…she will get worse and imagine how they will be treating her…she is a child…I don’t know what it’s going to happen’ (Parent 4).

Parental visits in adult placements

Parental visits in adult services were described as less frequent compared to child and adolescent services. In cases where parental visits were ongoing, this reportedly had a stabilising effect and aided continuity of the parent–child relationship which was described by young people as facilitative to the transition experience. Young people understood that being an adult required more independence although missed the emotional support received from their parents previously.

‘My mum used to visit me a lot more in child services…Now I moved here she doesn’t come that often. I guess because I am an adult. I preferred when she used to come and visit me. I do miss her sometimes. But it’s fine’ (Noah).

Impact of geographical location on parental support

Parents/carers reported that geographical distance was a major issue once young people moved to adult placements. Clinicians informed carers with short notice about bed shortage, predominantly in specialised services located in the southeast region.

‘I have to travel 3.5 hours in order to get to the hospital. They make it so difficult…we have to pay out of pocket’ (Parent 2).

However, this parent visited their child almost every other weekend in child services and this impacted positively the young person’s future transition outcome. The young person appeared to be more settled and confident in the adult service considering also that geographical proximity facilitated the process. This young male had ASD and, therefore, consistency with family involvement contributed to the optimal transition outcome.

‘The adult destination where my child is moving is of close proximity to our home and access will be easier compared to this hospital’ (Parent 3).

Discussion

This is the first study to follow-up with young people in transition from adolescent secure care to explore short- and long-term outcomes. The findings provide important new knowledge about the transition experiences of young people and carers leaving child and adolescent secure services. Young people and their carers expressed various challenges in the transition process. Carers voiced similar views to young people and pointed out how the uncertainty of institutional change impacts their children. This study extends the descriptive data from the previous studies and adopts an interactionist approach to understand, reflect and give meaning to this group’s experiences. The current findings revealed that those young people with the most severe mental health symptoms (psychosis, psychiatric comorbidities and emerging BPD) along with serious offences (murder, sexual assault and arson) experienced poor transition outcomes.

Safeguarding issues

As evidenced within such subthemes as ‘safeguarding in adult wards’ and ‘abrupt transitions increasing feelings of uncertainty’, young people described transitions as abrupt incidents and unsafe rather than an ongoing well-informed process with a beginning, middle and end. Transitions in most cases represented disruptive events characterised by lack of consistency and poor or little preparation in place. Lack of emotional and developmental readiness along with often unsafe adult settings, where young people were placed with much older peers, increased anxiety and feelings of isolation. As a result, the mental health symptoms of young people deteriorated during that time and, especially among those experiencing transitional delays on account of bed shortages and infrastructural barriers in the process. Young people were at increased risk of being secluded due to violent incidents on the ward such as assaulting staff or self-harming.

These findings are substantiated further by the subthemes ‘isolation in adult placements’ and ‘multiple transitions linked to a lack of consistent care’. Repeated trauma and loss through isolation and inconsistent service transitions builds on frustration and anger that might result in violent incidents (Tolan & Guerra, 1994). The majority of young people in adolescent medium secure services would meet the criteria for developmental trauma with early years marked by unsteady relationships with parents, abuse (sexual, physical), neglect and parental mental health problems (Van der Kolk, 2017). The subthemes ‘safeguarding in adult wards’ and ‘lack of consistent care’ suggests that these traumatic triggers may be perpetuated or re-emerge as a result of being at a higher risk of being bullied and having unsteady relationships with their care providers. Furthermore, moving to an adult placement which is tailored around a more independent, less trauma-attachment oriented care approach (Hill et al., 2014) is a major barrier for young people’s mental health improvement alongside being alienated from older peers.

Parental involvement

Parental involvement was a protective factor to young people’s transitions in this study. However, only in a few cases was the parent involved throughout the different stages of transition. Further, young people stated that their parents’ or carers’ involvement reduced once they moved to adult services. These findings are in line with previous research reporting on limited parental involvement when young people are transferred to adult services and parents feeling excluded from adult care (Bownas & Wilson, 2012). Geographical distribution of current national services hinders travelling for parents/carers living out of area. Geographical displacement is also a financial burden due to travelling expenses for these families. It has been reported that there is a shortage of hospital units in the southwest of England to meet this group’s needs (Hales et al., 2018). This unequal distribution of services has further implications for young people and their families and can be linked to poor transition outcomes (O’Herlihy et al., 2003).

Implications for clinicians and policy makers

The findings of this research illustrate the need for a national integrative care model diverging from the traditional ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach and acknowledging the vulnerabilities of each young person. Personalised care plans need to be prioritised for young people in secure services presenting with multiple and complex needs and more emphasis should be put on co-production of treatment and transition preparation (National Health Service, 2014). Subthemes found in this research such as ‘transitional delays hindering smooth transitions’ and ‘multiple transitions linked to a lack of consistent care’ show that there are vast inconsistencies throughout service transitions. These chaotic transitions need to be replaced by supportive services that promote continuity and consistency of care, and joint working.

Furthermore, it can be observed by such subthemes as ‘isolation in adult placement’ and ‘impact of geographical location on parental support’ that the well-being of these young people is being impacted by the loss of connections with their care providers (professional and personal). It is vital for these individuals to maintain close links with such care providers (Bownas & Wilson, 2012), and for the patients and family members to maintain involvement in their own care plans. A paper on new models of care (Appleton et al., 2020) emphasises the need to integrate primary care into transitions for young people moving to the community to promote a more collaborative care model. This model suggests ongoing monitoring by GPs and mental health professionals into primary care.

Further, findings show that individuals with specific vulnerabilities as LD and ASD experience poorer transitional outcomes. While integrating person-centred, individualised care, policy makers and clinical practitioners need to recognise these vulnerabilities and integrate gradual transitional models to adult-oriented services for these at-risk groups. Person-centred care contemplates the multiple vulnerabilities of this particular group and promises to tailor transitions around individualised needs. To date, the clinical significance of such service transformations is undervalued.

The participants in the present study felt that adult key workers were distant due to a lack of frequent clinical contact and reported that therapeutic alliance in adult mental health services differed significantly from CAMHS. The gap in care approach between the two services was particularly emphasised and, therefore, it might be helpful for key workers in adult and child services to work jointly in parallel care. The disconnect of services has been cited multiple times in the existing literature along with the undefined role of social services (Signorini et al., 2020). It is suggested that joint meetings with adolescent and adult services are prioritised in transition periods to enhance treatment outcomes and improve transitions from hyper-supportive environments such as child and adolescent medium secure units to more independent ones such as adult-oriented care.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first prospective study exploring young people’s experiences of transitions to adult services in the United Kingdom using a national sample across adolescent medium secure units which provides a novel insight into the transition experiences of young people and carers. However, this study included several challenges, as young people in adolescent medium secure services comprise an exceptionally sensitive group. Firstly, recruitment was particularly difficult, and the sample size was small reaching only 38% of the desirable sample of young people. Considering the small number of young people admitted to adolescent medium secure units annually in line with one unit’s data (they had admitted 55 young people within a 5-year period), the included subsample of young people can be justified (Dimond & Chiweda, 2011). Additionally, 10 young people were interviewed without the presence of a key worker; however, for three young people, adult key workers had to be present during the interviews due to high-risk presentation. Therefore, these young people may have been cautious about disclosing information considering that their responses could be affected by exogenous factors (i.e., authority figures). Families of the young people were not easy to reach due to reasons, such as geographical location, lack of involvement and distrust in services.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-ccp-10.1177_13591045211026048 for Transition outcomes for young people discharged from adolescent medium secure services in England: A qualitative study exploring adolescents’ and carers’ experiences by Maria I Livanou, Marcus Bull, Rebecca Lane, Sophie D’Souza, Aiman El Asam and Swaran P Singh in Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support of all participating sites and local collaborators for the conduct of this study. Swaran Singh is part funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) West Midlands. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Author biographies

Maria Livanou is a Senior Lecturer in Forensic Psychology at Kingston University and the Course Director of the BSc Programme in Forensic Psychology. She has an interest in mental health transitions and policy.

Marcus Bull is a fully-funded PhD student at Kingston University. His research focuses on conduct problems in youth and buffering protective factors.

Rebecca Lane is a research assistant at Kingston University and is affiliated with the University College London and the Anna Freud Centre for Children and Families.

Sophie D’ Souza is affiliated with the University College London and the Anna Freud Centre for Children and Families. She is a graduate of the MSc in Human Development and Psychology at the University of Harvard.

Aiman El Asam is a Senior Lecturer in Forensic Psychology at Kinsgton University with specific interest in cognitive interviewing, online safety (e-safety) and mental health, cyber-bullying and psychopathology.

Swaran P Singh is a Professor of Social and Community Psychiatry at the University of Warwick with specific interest in health services, with focus on early psychosis, somatisation, and deliberate self-harm, cultural and ethnic factors in mental illness, mental health law, transitions and medical education.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaborating in Applied Health Research (CLAHRC) West Midlands which was part of the PhD thesis for ML.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD

Maria I Livanou https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7864-5878

References

- Appleton R., Mughal F., Giacco D., Tuomainen H., Winsper C., Singh S. P. (2020). New models of care in general practice for the youth mental health transition boundary. BJGP Open, 4(5), bjgpopen20X101133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bownas J., Wilson E. (2012). Warm welcomes in unfamiliar places: A systemic approach to including families in a secure adolescent mental health inpatient unit. In Davies A., Doran J. (Eds.), Working in forensic contexts. Context (Vol. 124, pp. 9-14). [Google Scholar]

- Braun V.,, Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S., Abbott S., Simpson A. (2014). Young offenders with mental health problems in transition. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 9(4), 232-243. [Google Scholar]

- Dimond C.,, Chiweda D. (2011). Developing a therapeutic model in a secure forensic adolescent unit. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 22(2), 283-305. [Google Scholar]

- Hales H., Warner L., Smith J., Bartlett A. (2018). Census of young people in secure settings on 14 September 2016: Characteristics, needs and pathways of care. [Google Scholar]

- Hill S. A., Brodrick P., Doherty A., Lolley J., Wallington F., White O. (2014). Characteristics of female patients admitted to an adolescent secure forensic psychiatric hospital. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 25(5), 503-519. [Google Scholar]

- Kane S. (2008). Managing the transitions from adolescent psychiatric in-patient care: Toolkit. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; 27(4): 228–235. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan T.,, Racussen L. (2013). A crisis recovery model for adolescents with severe mental health problems. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 18(2), 246-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly M.,, Coughlan B. (2019). A theory of youth mental health recovery from a parental perspective. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 24(2), 161-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livanou M. I., Lane R., D’Souza S., Singh S. P. (2020). A retrospective case note review of young people in transition from adolescent medium secure units to adult services. The Journal of Forensic Practice, 22(3), 161-172. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service . (2014). Five year forward view. Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf (accessed 15 October 2020).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . (2016). Transition from children’s to adults’ services for young people using health or social care services (p. NG43). Clinical guideline. [Google Scholar]

- O'Herlihy A., Worrall A., Lelliott P., Jaffa T., Hill P., Banerjee S. (2003). Distribution and characteristics of in-patient child and adolescent mental health services in England and Wales. British Journal of Psychiatry, 183(6), 547-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul M., Street C., Wheeler N., Singh S. P. (2015). Transition to adult services for young people with mental health needs: A systematic review. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 20(3), 436-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C., Ziebland S., Mays N. (2000). Qualitative research in health care: Analysing qualitative data. British Medical Journal, 320(7227), 114-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw R. (2010). Embedding reflexivity within experiential qualitative psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 7(3), 233-243. [Google Scholar]

- Signorini G., Davidovic N., Dieleman G., Franic T., Madan J., Maras A., Santosh P. (2020). Transitioning from child to adult mental health services: What role for social services? Insights from a European survey. Journal of Children’s Services, 14(3): 358-361. [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. P., Paul M., Ford T., Kramer T., Weaver T. (2008). Transitions of care from child and adolescent mental health services to adult mental health services (TRACK study): A study of protocols in Greater London. BMC Health Services Research, 8(1), 135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan P.,, Guerra N. (1994). What works in reducing adolescent violence. The Center for the Study and Prevention of Violence. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kolk B. A. (2017). Developmental trauma disorder: Toward a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories. Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), 401-408. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley M. D., Long C. G. L., Dolley O. (2013). Transitions of females from adolescent secure to adult secure services: A qualitative pilot project. Journal of Mental Health, 22(3), 207-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-ccp-10.1177_13591045211026048 for Transition outcomes for young people discharged from adolescent medium secure services in England: A qualitative study exploring adolescents’ and carers’ experiences by Maria I Livanou, Marcus Bull, Rebecca Lane, Sophie D’Souza, Aiman El Asam and Swaran P Singh in Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry