Summary

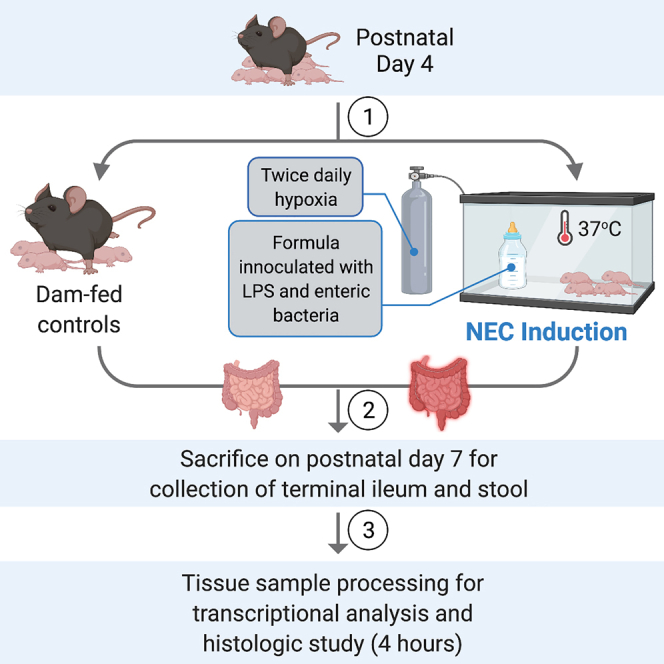

Recapitulating human NEC using animal models has been insightful in dissecting the signaling pathways, immune-mediated mechanisms, genetic signatures, and the intestinal architecture of NEC. This protocol describes an in vivo murine NEC model, using hypoxia and formula containing lipopolysaccharide and enteric bacteria derived from an infant with NEC. With this mouse model, we aim to further dissect NEC pathogenesis and develop new therapeutic strategies.

For complete details on the use and execution of this protocol, please refer to Mihi et al. (2021).

Subject areas: Developmental biology, Health Sciences, Microbiology, Model Organisms, Molecular Biology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

This protocol describes the induction of murine necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC)

-

•

This mouse model is based on the use of hypoxia and formula supplemented with LPS

-

•

This mouse model can be used to study NEC pathogenesis and therapeutic targets

Recapitulating human NEC using animal models has been insightful in dissecting the signaling pathways, immune-mediated mechanisms, genetic signatures, and the intestinal architecture of NEC. This protocol describes an in vivo murine NEC model, using hypoxia and formula containing lipopolysaccharide and enteric bacteria derived from an infant with NEC. With this mouse model, we aim to further dissect NEC pathogenesis and develop new therapeutic strategies.

Before you begin

Investigators are required to obtain appropriate ethical approval from their Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) or equivalent for the use of vertebrate animals. All animal experiments were performed in an American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited and specific pathogen-free animal facility at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. All mice were bred, maintained, and housed in accordance with the procedures outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals under a study proposal approved by the IACUC (protocol no. 20-0050) of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| C57BL/6J, M. musculus, Neonatal mice of both sexes, postnatal day 4–7 | The Jackson Laboratory | Stock No. 000664 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| GGCGACCTGGAAGTCCAACT | Integrated DNA Technologies | RPLO (Mouse) forward primer for quantitative PCR |

| CCATCAGCACCACAGCCTTC | Integrated DNA Technologies | RPLO (Mouse) reverse primer for quantitative PCR |

| AGTGTGGATCCCAAGCAATACCCA | Integrated DNA Technologies | Il1b (Mouse) forward primer for quantitative PCR |

| TGTCCTGACCACTGTTGTTTCCCA | Integrated DNA Technologies | Il1b (Mouse) reverse primer for quantitative PCR |

| CAGACAGAAGTCATAGCCACT | Integrated DNA Technologies | Cxcl2 (Mouse) forward primer for quantitative PCR |

| GGCACATCAGGTACGATCCA | Integrated DNA Technologies | Cxcl2 (Mouse) reverse primer for quantitative PCR |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| ImageJ | Schneider et al., 2012 | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij |

| GraphPad Prism Software, Version 9.0 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com |

| Other | ||

| Infant Incubator, C100-200-2 Series, set at 37°C | Air Shields-Vickers | N/A |

| Hypoxia Chamber | Billups-Rothenberg, Inc. | N/A |

| Handi+ Oxygen analyzer | Maxtec | N/A |

| Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter, 1.9 French, Single- Lumen | Utah Medical Products, Inc. | N/A |

| Esbilac Puppy Milk replacer | Pet-Ag, Inc. | N/A |

| Similac Advance® OptiGROTM with Iron infant formula | Abbott Nutrition | N/A |

Step-by-step method details

Preparing the enteric bacterial challenge

Timing: 10 min

Preparation of the bacterial suspension for inoculation into the mouse formula is based on the intestinal microbiota obtained from the enteric contents of an infant with the most severe form of NEC, NEC totalis (Good et al., 2014; Mihi et al., 2021). The enteric bacterial stock was generated by overnight (16 h) culturing of the fecal slurry in the resected intestinal tissue from an infant with NEC totalis. The bacteria culture was then centrifuged, resuspended in 50% glycerol, aliquoted in cryovials and stored at −80°C.

-

1.

The day before initiating the model, use a sterile pipette tip to scrape approximately 10 μL of an enteric bacterial glycerol stock from a frozen cryovial.

-

2.Place the sterile pipette tip containing the bacterial aliquot into a 15-mL culture tube containing 2 mL of LB Broth. Culture the bacteria overnight (16 h) in an orbital shaker at 37°C with agitation speed at 150 rpm.

-

a.A control culture tube with 2 mL of sterile LB broth should also be cultured simultaneously in the orbital shaker to ensure there is no concern for bacterial contamination of the LB broth.

-

a.

Preparing the formula and allocating pups into experimental groups

Timing: 2 h

-

3.

The following morning, transfer 100 μL of the bacterial culture into four T75 culture flasks each containing 20 mL LB broth.

-

4.

Culture this inoculum for a minimum of two hours in an orbital shaker with agitation speed at 150 rpm at 37°C.

-

5.At 7 AM on the first day of the model, in the animal facility, weigh the postnatal day 4 pups to be included in the model and randomly assign the animals into two experimental groups: dam-fed and formula-fed.

-

a.For the dam-fed group, allow the mouse pups to remain with the mother for the full duration of the model. These pups will be served as dam-fed negative controls.

-

b.For the formula-fed group, separate the pups from the mother into a new cage and place the cage into a pre-warmed infant incubator at 37°C. This group will be housed in the incubator for the full duration of the model.

-

a.

-

6.

Use a spectrophotometer to measure the density of the two-hour bacterial culture at 600 nm (OD600nm). Add 1 mL of sterile LB broth into a 1 cm cuvette and measure the OD600nm to serve as the blank. In a separate 1 cm cuvette, add 1 mL of the inoculum and measure the OD600nm.

Note: The OD600nm value should be 0.6 ± 0.02, corresponding with the exponential phase of bacterial growth.

Note: If the OD600nm is greater than 0.6, use LB broth to dilute the culture until the diluted culture results in a goal OD600nm. If the OD600nm is less than 0.6, continue to culture the inoculum until the OD600nm reaches 0.6.

-

7.

Once the inoculum has achieved the goal OD600nm, transfer 20 mL of the inoculum from each culture flask into separate 50-mL conical tubes and centrifuge at 3000 × g for 10 min. Discard the supernatant.

-

8.

Resuspend the bacterial pellets each in 1 mL sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in a 50-mL conical tube.

-

9.

Add 4 mL of the total resuspended bacteria into 20 mL of NEC formula (comprised of a 2:1 ratio of Similac Advance formula to Esbilac puppy milk) in a 50-mL conical tube.

-

10.

Using the average weight of the pups from the morning, add 5 μg/g lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to the NEC formula. LPS serves as a ligand for innate immune receptor toll-like receptor 4 signaling, which has been shown to be required for the development of NEC via impairment of the integrity of the intestinal epithelial barrier (Mihi and Good, 2019).

Note: The addition of both enteric bacteria and LPS to the NEC formula is necessary for the induction of NEC-like pro-inflammatory response in this model.

Note: This NEC formula with LPS contains the volume to be used for 6 feeds per 24-h period, with the first feeding timed for 10 AM on day 1 of the model and newly made formula at 10AM on days 2–3 of the model.

Induction of experimental NEC

Timing: 3 days

-

11.

Perform scheduled feedings of the mouse pups beginning at 10 AM on Day 1 of the model. Fill a 1-mL syringe with NEC formula and attach it to a 1.9 French single-lumen PICC line.

-

12.Provide the mouse pups with oral gavage feedings of the NEC formula.

-

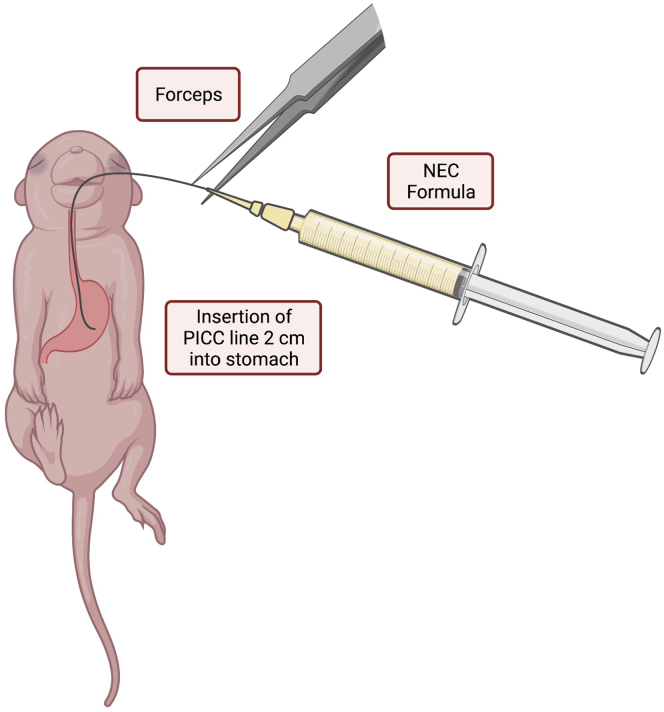

a.Gently hold the pup by grasping the loose skin at the base of the neck and use forceps to grasp the distal end of the PICC line to gently introduce 2 cm of the PICC into the oropharynx and esophagus (Figure 1).

-

b.There should be no significant resistance with the insertion of the PICC line.

-

c.Slowly dispense 80 μL of NEC formula into the stomach.

-

d.Then slowly withdraw the PICC line from the oral cavity.

-

e.Monitor the animal for increased respiratory effort or emesis associated with a malpositioned PICC line.

-

a.

Note: In our model, mouse pup feedings occur at 7 AM (starting on model day 2), 10 AM, 1 PM, 4 PM, 7 PM and 10 PM. Repeat step 12 at each of these time points.

-

13.Twice daily, immediately following the 1 PM and 7 PM feedings, subject the mouse pups to hypoxia.

-

a.Place the pups in a hypoxia chamber connected to a gas tank containing 95% nitrogen and 5% oxygen for 10 min.

-

b.Carefully monitor the mouse pups for signs of apnea, cyanosis or pale discoloration, or abdominal distension in between feeds. Pups that present with these signs should be immediately euthanized per IACUC policy.

-

a.

-

14.

At 3 PM on model days 1 and 2, prepare the bacterial culture for the next day, as described in steps 3 and 4, in order to prepare and provide NEC formula for the full duration of the model.

-

15.On model days 2 and 3, at 7 AM, obtain the daily weight of each pup to identify the daily average weight of the pups in each group and then provide oral gavage feeding using the formula prepared from the day prior.

-

a.Be sure to first invert the 50-mL conical gently several times while avoiding the formation of air bubbles in the formula.

-

b.Prepare the new daily NEC formula as in steps 6–10. Perform scheduled oral gavage feedings and hypoxia exposure per steps 11–13 to complete the 72-h mouse model of NEC.

-

a.

Figure 1.

Illustration of insertion of the PICC line into the oropharynx and esophagus for delivery of NEC formula

Using forceps, the PICC line is gently inserted 2 cm for delivery of NEC formula into the stomach of the mouse pup. Figure created with biorender.com.

Sacrificing animals and harvesting tissue

Timing: 10 min per animal

-

16.

On the morning of model day 4, obtain the daily weight of each pup. Euthanize the pups in accordance with IACUC and institutional policies. Make a vertical incision along the abdominal wall to expose the gastrointestinal tract.

-

17.

Locate and resect the intestine from the duodenum to the distal rectum. Place the intestine in a petri dish containing ice-cold PBS. Isolate the desired segments of the intestine for tissue collection and processing.

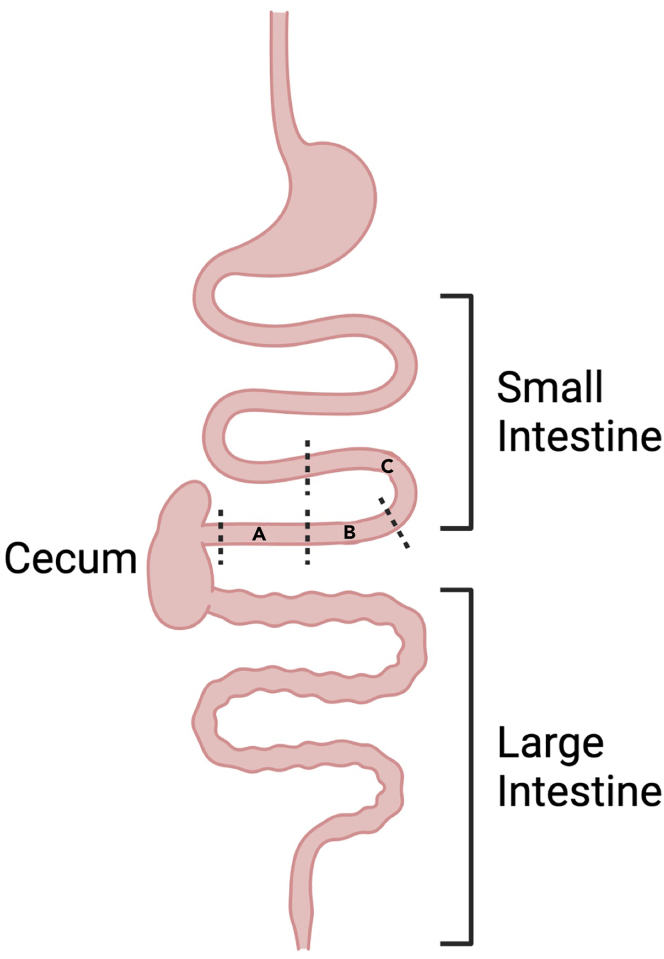

Note: This model focuses primarily on pathology within the ileum. The terminal part of the ileum, which is approximately 3 cm from the cecum, is resected. A small piece of the terminal ileum (1 cm) is placed in RNA-laterTM for transcriptional analysis (Figure 2A). Another small piece of terminal ileum (1 cm) is snap-frozen in a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube and kept frozen at −80°C for protein analysis (Figure 2B).

Note: For analysis of intestinal microbial communities, mouse fecal contents can be collected for 16s rRNA microbial analysis (Mihi et al., 2021). Locate and resect the intestine at the proximal colon, adjacent to the cecum and place the tissue on a clean surface. Using forceps, gently press on the exterior of the colon to allow fecal contents to pass along to the distal end of the intestinal lumen for collection. Fecal samples should be snap-frozen in a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube and stored at −80°C for later 16s rRNA microbial sequencing (Mihi et al., 2021). Mouse pups subjected to experimental NEC will exhibit an intestinal microbiome with an overabundance of Gammaproteobacteria species similar to human infants with NEC (Mihi et al., 2021; Nolan et al., 2021).

Figure 2.

Recommended segmental transection of small intestine during tissue collection

(A–C) During postmortem dissection, segment (A) of the terminal ileum is collected for transcriptional analysis, segment (B) is collected for protein analysis and segment (C) is resected for histological study. Figure created with Biorender.com.

Preparation of intestines for cross-sectional histological analysis

Timing: 5 min per animal

-

18.

The remaining segment of the terminal ileum (Figure 2C) is flushed with PBS and then with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) using a 24-gauge gavage needle.

-

19.

The tissue segment is transected longitudinally using fine scissors, doused in 4% PFA, and transferred to a container for immersion in 4% PFA for fixation. After 24 h at 4°C, discard the PFA and wash with PBS twice for 15 min.

-

20.

Discard the PBS and then dehydrate with 50% ethanol for 15 min and then 70% ethanol for storage prior to embedding.

Note: The fixation, wash and dehydration steps should be carried out at 4°C on a rocker.

-

21.

The intestinal specimens are then carefully embedded in agar first and then paraffin. Tissue sections are cut on a microtome at 5-μm thickness and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histological study.

Tissue processing for transcriptional analysis

Timing: 4 h

-

22.

For RNA isolation from the transected terminal small intestine, add 1 mL TRIzolTM to the resected intestinal tissue stored in RNA Later (Invitrogen).

-

23.Add one steel bead per tube and homogenize the tissue using the Qiagen TissueLyser for 7 min at 50 oscillations per second.

-

a.Once the tissue is completely homogenized, remove the steel bead, and add 200 μL of chloroform.

-

b.Vigorously invert the tube ten times and allow the samples to incubate at 68–77°F (20°C–25°C) for five minutes.

-

a.

-

24.Centrifuge the samples for 10 min at 18,000×g and 4°C.

-

a.The solution will separate into three layers: a top aqueous layer, a white middle layer, and a bottom pink layer of Trizol.

-

a.

-

25.

Transfer 500 μL of the aqueous layer into a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. Add 500 μL of isopropanol and 3 μL glycogen, and gently invert the sample 10 times.

-

26.

Incubate the samples at -20°C for 20 min.

-

27.

Centrifuge the samples for 10 min at 18000×g and 4°C. Decant the supernatant and add 0.5 mL of 70% ethanol to each sample.

-

28.

Centrifuge the samples for 5 min at 18000×g and carefully decant the supernatant.

-

29.

Centrifuge the samples again for 1 min at 18000×g. Remove the remaining ethanol with a fine-tip pipette and allow the samples to air dry for at least 15 min.

-

30.When the pellet appears transparent, add 50 μL of RNase-free water and allow the pellets to hydrate for approximately 10 min.

-

a.Vortex the samples and measure the RNA concentration using a spectrophotometer before storing the samples at −80°C.

-

b.Use the Qiagen QuantiTec Reverse Transcription Kit to synthesize the complementary DNA following the manufacturer’s protocol: https://www.qiagen.com/us/resources/resourcedetail?id=f0de5533-3dd1-4835-8820-1f5c088dd800&lang=en.

-

a.

-

31.Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) is performed using IQ SYBR Green Supermix and CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

-

a.The CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System utilizes a two-step amplification process by heating the samples to 95°C for five minutes, then alternating between 95°C for ten seconds and 55°C for 30 s, repeated for 40 cycles as described in the manufacturer’s instructions: https://www.bio-rad.com/webroot/web/pdf/lsr/literature/10000068707.pdf.

-

b.The primers are listed in Table 1, and a melting curve was added to the amplification protocol to ensure the absence of primer dimer formation or multiple amplicons.

-

c.The expression of genes assessed by qRT-PCR was quantified relative to the housekeeping gene RPLO.

-

a.

Table 1.

Primers for qRT-PCR analysis of pro-inflammatory gene expression

| Gene | Species | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Amplicon size (base pairs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPLO | Mouse | GGCGACCTGGAAGTCCAACT | CCATCAGCACCACAGCCTTC | 143 |

| Il1b | Mouse | AGTGTGGATCCCAAGCAATACCCA | TGTCCTGACCACTGTTGTTTCCCA | 175 |

| Cxcl2 | Mouse | CCAGACAGAAGTCATAGCCACT | GGCACATCAGGTACGATCCA | 217 |

Expected outcomes

Assessment of NEC severity and intestinal injury

As NEC continues to have a high morbidity and mortality rate in preterm infants, the importance of reliable modeling to investigate the pathogenesis and potential therapeutics remains a priority in NEC research. Experimental modeling of NEC using rodents is commonly used due to low cost of maintenance and ease of breeding (Sulistyo et al., 2018). Barlow and colleagues described an early model of NEC in 1974 using neonatal rats (Barlow et al., 1974). The Barlow model incorporated factors that are recognized as contributing factors in NEC development, including intestinal immaturity, hyperosmolar feeds, hypoxic stress and dysbiosis (Barlow et al., 1974). Subsequent experimental NEC models using rodents have been modified to include exposure to 100% nitrogen, cold stress or the addition of lipopolysaccharide to recapitulate the intestinal inflammation and injury observed human NEC (Sulistyo et al., 2018). Additionally, some investigators have used piglet or rabbit models of NEC in the attempt to create a model that more closely mimics the human disease; however, these models are limited by differences in pathologic intestinal changes when compared to human NEC, high cost of maintenance and challenges involved in creating transgenic animals (Sulistyo et al., 2018). Therefore, this protocol describes a method of inducing intestinal injury and an inflammatory response in neonatal mice to model the findings observed in human NEC (Neu and Walker, 2011; Patel et al., 2020).

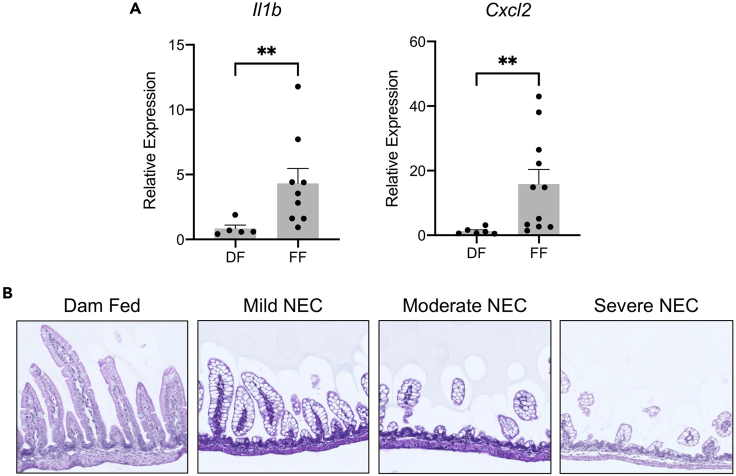

During postmortem analysis, mouse pups with NEC demonstrate abdominal distension. In the assessment of gross organ disease severity, pups subjected to the NEC model exhibit significant and diffuse intestinal gaseous dilation, and they may occasionally develop intestinal perforation. When small intestinal tissue is collected for transcriptional analysis, formula-fed pups (FF) with experimental NEC have a significantly upregulated expression of pro-inflammatory markers, including Il1b and Cxcl2 when compared with dam-fed (DF) control littermates (Figure 3A). The histological features of the small intestine from dam-fed pups compared with progressive severity of NEC injury are detailed in Figure 3B, in which pups with severe NEC experience disruption of the intestinal epithelial architecture and destruction of the intestinal villi. These findings recapitulate several of the features seen in human NEC.

Figure 3.

Experimental murine NEC recapitulates inflammatory and histologic features of human NEC

(A) Formula-fed pups (FF) subjected to experimental NEC demonstrate significantly upregulated mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory markers Il1b and Cxcl2 when compared with dam-fed (DF) control littermates.

(B) Representative histology from dam-fed pups compared with pups with progressive severity of NEC-like injury reveals intestinal villous destruction and disrupted overall intestinal architecture. ∗∗p < 0.001 by Mann-Whitney U test.

Limitations

This protocol is optimized to induce an NEC-like intestinal injury in 4-day-old neonatal mouse pups using a 72-h model. As this protocol requires young mice with intestinal immaturity, performing the model on older mice may not provide the same degree of intestinal injury and inflammation. Additionally, individual mouse or strain differences may impact the outcomes of this experimental NEC induction model.

Troubleshooting

Problem 1

Pups develop signs of apnea while in the hypoxia chamber (step 13b).

Potential solution

Gently rock the chamber during the induction of hypoxia to stimulate spontaneous breathing reflexes.

Problem 2

Pups develop respiratory distress or vomiting after the gavage of formula (step 12).

Potential solution

Ensure that the PICC line is being inserted slowly into the oral cavity. There should be no significant resistance to the insertion of the PICC line. Resistance or bouncing of the PICC line when inserted into the oral cavity is concerning for curling of the PICC line in the oropharynx or accidental insertion into the trachea, and the PICC line should be immediately withdrawn and reinserted.

Problem 3

Intestinal specimens are difficult to flush with PBS or 4% PFA during histology preparation (step 18).

Potential solution

The induction of NEC results in very friable intestinal tissue. Flush the intestine gently to prevent damage to the intestinal architecture.

Problem 4

The mortality rate of the model can be up to 50%.

Potential solution

Different mouse strains may differ in the degree of intestinal injury or mortality rate when subjected to experimental NEC. To reduce the risk of iatrogenic deaths, it is important to carefully dose the LPS per the daily weight of the pups, use fresh stocks of puppy milk and infant formula and ensure that the enteric bacterial stock is stored at −80°C when not in use. It is also important to train personnel on careful handling and gavage feeding of pups to avoid unintentional deaths. The mouse mortality should be assessed daily during the model to ensure an avoidance of preventative harm during the model. While inducing NEC-like disease in animals, the mice are euthanized if they exhibit signs of distress, pain, or discomfort and each animal is autopsied to determine their cause of death (whether iatrogenic or due to disease).

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Dr. Misty Good at mistygood@wustl.edu.

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Acknowledgments

L.S.N. receives funding support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH; F32DK130248) and the American Academy of Pediatrics Marshall Klaus Award. M.G. receives funding from the NIH (R01DK118568, R01DK124614, and R01HD105301), the St. Louis Children’s Hospital Foundation, the Children's Discovery Institute of Washington University and St. Louis Children's Hospital, and the Department of Pediatrics at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. M.G. has also received sponsored research agreement funding from Takeda Pharmaceuticals and Evive Biotech in the past year, but these funders did not play any role in this study.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, L.S.N. and M.G.; methodology, all authors; investigation, all authors.; writing – original draft, L.S.N. and M.G..; writing – review & editing, all authors; funding acquisition, L.S.N. and M.G.; resources, M.G.; supervision, M.G.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data and code availability

The published article includes all datasets generated or analyzed during this study. This study did not generate any code.

References

- Barlow B., Santulli T.V., Heird W.C., Pitt J., Blanc W.A., Schullinger J.N. An experimental study of acute neonatal enterocolitis–the importance of breast milk. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1974;9:587–595. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(74)90093-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good M., Sodhi C.P., Ozolek J.A., Buck R.H., Goehring K.C., Thomas D.L., Vikram A., Bibby K., Morowitz M.J., Firek B., et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 decreases the severity of necrotizing enterocolitis in neonatal mice and preterm piglets: evidence in mice for a role of TLR9. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2014;306:G1021–G1032. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00452.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihi B., Gong Q., Nolan L.S., Gale S.E., Goree M., Hu E., Lanik W.E., Rimer J.M., Liu V., Parks O.B., et al. Interleukin-22 signaling attenuates necrotizing enterocolitis by promoting epithelial cell regeneration. Cell Rep. Med. 2021;2:100320. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihi B., Good M. Impact of toll-like receptor 4 signaling in necrotizing enterocolitis: the state of the science. Clin. Perinatol. 2019;46:145–157. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu J., Walker W.A. Necrotizing enterocolitis. New Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:255–264. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1005408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan L.S., Mihi B., Agrawal P., Gong Q., Rimer J.M., Bidani S.S., Gale S.E., Goree M., Hu E., Lanik W.E., et al. Indole-3-carbinol-dependent aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling attenuates the inflammatory response in experimental necrotizing enterocolitis. ImmunoHorizons. 2021;5:193–209. doi: 10.4049/immunohorizons.2100018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel R.M., Ferguson J., McElroy S.J., Khashu M., Caplan M.S. Defining necrotizing enterocolitis: current difficulties and future opportunities. Pediatr. Res. 2020;88:10–15. doi: 10.1038/s41390-020-1074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C.A., Rasband W.S., Eliceiri K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1515/iss-2017-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulistyo A., Rahman A., Biouss G., Antounians L., Zani A. Animal models of necrotizing enterocolitis: review of the literature and state of the art. Innovative Surg. Sci. 2018;3:87–92. doi: 10.1515/iss-2017-0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The published article includes all datasets generated or analyzed during this study. This study did not generate any code.