Highlights

-

•

The main properties of coordinated magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) including magnetic moment and saturated magnetisation).

-

•

The doping of transition metal ions into ferrite to precisely modulate its magnetic properties.

-

•

the potential mechanisms and recent advances in transition metal ion-doped MNPs (TMNPs) for bioimaging: magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic particle imaging and tumour therapy: e.g., magneto-mechanical killing, magnetothermal therapy, and drug delivery.

-

•

the current challenges and future trends of TMNPs in the biomedical field based on the latest advances by researchers.

Keywords: MNPs, Magnetic nanoparticles; TMNPs, Transtion metal ion-doped MNPs; Ms, Saturated magnetization; Mr, Remanet magnetization; MRI, Magnetic resonance imaging; MOF, Metal-organic framework; CT, Computed tomography; MPI, Magnetic particle imaging; FFP, Field-free point; SPECT, Single-photo emission computed tomography; PET, Positron emission tomography; SFNPs, Superparamagnetic ferrite nanoparticles; DDS, Drug delivery systems; MPS, Mononuclear phagocyte system; AMF, Applied magnetic field; MH, Magnetic hyperthermia; PDT, Photodynamic therapy; PTT, Photothermal therapy; SLP, Specific loss rate; SAR, Specific absorption rate; MMT, Magnetic mechanotransduction; RMF, Rotating magnetic field; TNF, Tumour necrosis factor; EGF, Epidermal growth factor

Keywords: Magnetic nanomaterials, Transition metals, Dopant, Bioimaging, Cancer therapy

Abstract

Magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) have been extensively researched and implemented in biomedicine for more than half a century due to their non-invasive nature, ease of temporal and spatial manipulation, and considerable biocompatibility. However, the complex magnetic behaviour of MNPs is influenced by several parameters (e.g., particle size, shape, composition, core-shell structure, etc.), among which the amount of transition metal doping plays an important factor. For this reason, the doping of ferrite with transition metals has been used as an effective strategy to precisely tailor MNPs to achieve satisfactory performance in biomedical applications. In this review, we first introduced the main properties of coordinated MNPs (including magnetic moment and saturated magnetisation) and provide a comprehensive overview of the mechanistic studies related to the doping of transition metal ions into ferrite to precisely modulate its magnetic properties. We also highlighted the potential mechanisms and recent advances in transition metal ion-doped MNPs (TMNPs) for bioimaging (magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic particle imaging) and tumour therapy (e.g., magneto-mechanical killing, magnetothermal therapy, and drug delivery). Finally, we summarised the current challenges and future trends of TMNPs in the biomedical field based on the latest advances by researchers.

Graphical abstract

Transition metal doped magnetic nanoparticles (TMNPs) for biomedical applications

Introduction

Since the end of the 20th century, with the rapid development of nanotechnology, magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), particularly iron-based nanomaterials, have received extensive attention from numerous researchers due to their tuna magnetic properties, ease of manipulation, and non-intrusiveness. From methods for synthesising MNP with anisotropic and compound structures to the emergence of substantially related characterization instruments (e.g. Vibration sample magnetometer, Magneto-optical Kerr effect, Mössbauer spectrum, etc.) and a focus on MNPs in biomedical applications such as bioimaging, drug delivery, and tumour therapy [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. It has been shown that the magnetic moment and magnetic anisotropy of each atom in MNPs differ significantly from those of bulk materials [6]. The relevant performance parameters of MNPs are closely related to their intrinsic physical and chemical properties, like composition, shape, particle size, and core-shell structure [7]. Therefore, to satisfy the requirements for practical applications, the adjustment of the relevant parameters will be of great significance in improving the performance of MNPs [8,9].

Remarkably, transition metal ion doping plays an important role in modulating the properties of MNPs. This review focuses on the mechanism of modulating the magnetic properties of MNPs by doping divalent transition metal ions and summarises recent advances in transition metal-doped iron-based nanoparticles (TMNPs) for bioimaging (e. g., magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic particle imaging) and tumour therapy (e. g., magnetothermia, magneto-mechanical force, etc.), and finally concludes with a summary and outlook on the development prospects (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Transition metal-doped magnetic nanoparticles (TMNPs) for biomedical applications. (a) Mechanistic diagram of transitional metal ions doped into magnetic nanoparticles by substituting iron ions. (b) The influence of doped transition metal ions on various parameters of magnetic nanomaterials. (c) Applications of TMNPs in bioimaging assays and tumour therapy.

Coordinating the magnetism of magnetic nanomaterials

Tunable properties of magnetic nanomaterials

The design of MNPs with customized properties for practical applications depends essentially on some basic principles of nano-magnetism, which can facilitate a better understanding of the correlation between multiple exogenous and inogenous factors [10]. Magnetic nanomaterials can generally be classified into five categories, including antimagnetic, paramagnetic, ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic, based on the inherent net magnetisation strength and the response of magnetic dipoles when an applied magnetic field is present or absent [11,12].

The net magnetic dipoles alignment for each magnetic material is shown in Fig. 2a. In the case of antimagnetic materials, no magnetic dipoles exist in the absence of an applied magnetic field (AMF). Nevertheless, under the effect of a magnetic field, the material produces magnetic dipoles opposite to the applied magnetic field. Hence, materials with strong anti-magnetic properties can be rejected by an external magnetic field. In the case of paramagnetic materials, the magnetic dipoles are only aligned in the parallel direction of the magnetic field when a certain external magnetic field is imposed, whereas without an external magnetic field they are in a disordered state (weak bonding of magnetic domain walls). In contrast to paramagnetic materials, ferromagnetic or ferrimagnetic materials still possess a certain pure magnetic dipole moment, despite the withdrawal of the surrounding magnetic field. The difference between ferromagnetic and ferrimagnetic materials is that the magnetic moments in the opposite direction of the ferrimagnetic material are partially neutralised when no external magnetic field is applied, due to the exchange of electrons between neighbouring atoms. In addition, although antiferromagnetic materials have atomic-scale magnetic dipole moments comparable to that of ferromagnetic materials in the absence of applied fields. However, their magnetisation is close to zero due to the opposite direction of the adjacent electron spins.

Fig. 2.

(a) Schematic diagram of the magnetic dipoles arrangement of five types of magnetic material with the absence or presence of the external magnetic field. (b) Magnetisation curves of a ferro- or ferrimagnetic material under the applied magnetic field. (c) Schematic diagram of the correlation between magnetic coercivity and particle size.

Further, for ferro- or ferrimagnetic materials, the magnetic behaviour can be described using some basic parameters derived from typical magnetisation curves (Fig. 2b). In the magnetization curve, the saturated magnetization (Ms, maximum magnetization) occurs when all magnetic dipoles are parallel in the external magnetic field. Alternatively, the remanent magnetization (Mr) and the coercivity (Hc) represent the remaining induced magnetisation after removal of the applied magnetic field and the external coercivity required for the magnetisation strength to be zero, respectively. Notably, the response of superparamagnetic nanoparticles to external fields is more sensitive and hysteresis-free compared to the hysteresis observed for ferromagnetic nanoparticles.

The critical size (rc) represents the maximum size at which a particle can grow without the presence of multidomain walls, corresponding to the transition from single to multiple domains, which is closely related to the coercivity (Hc) and the magnetocrystalline anisotropy [13,14]. Furthermore, MNPs exhibit superparamagnetism when they are below the critical size (ro), the magnetic moment of MNPs can therefore be estimated from this property [15]. Briefly, without the constraint of a magnetic domain wall, magnetic dipoles are randomly arranged with an average magnetic moment of zero when an applied magnetic field is inapplicable, while the magnetic moment increases rapidly under an available magnetic field (Fig. 2c). On this basis, superparamagnetic materials are particularly important in drug delivery and bioimaging. In these applications, MNPs are not attracted to each other after the removal of the external magnetic field, thus depriving the main force driving the agglomeration of MNPs. Most importantly, the magnetic behaviour of superparamagnetic nanoparticles is better controlled because of their robust response to the external magnetic field.

The magnetic coordination mechanism of TMNPs

Changing the chemical composition of MNPs (doping with transition metals) is one of the common ways to modify their magnetic properties and improve their performance in biomedical applications. The main parameters of magnetism include magnetic moment (μ), saturation magnetisation (Ms), coercivity (Hc), anisotropy (K), and relaxation time (τN and τB). In addition, these magnetic properties are present in the unpaired valence electrons of the metal ions in MNPs, and the orientation of the magnetic moment related to the electrons determines this magnetic behaviour. Generally, the individual electron has a magnetic moment of 1.73 Bohr magnetons [16]. The magnetic moment of MNPs can therefore be estimated from this property, highlighting the remarkably close correlation between the magnetic performance of the material and the specific elements in the composition.

On the other hand, the allocation of cations in the octahedral (Oh) and tetrahedral positions (Td) in iron-based materials with a crystalline structure of spinel or anti-spinel is one of the key factors determining their magnetic moment, which is primarily influenced by the type of metal ions in the Oh-sites and Td-sites [17]. In the case of Fe3O4 anticline, Fe2+ and half of Fe3+ occupy Oh-sites and the residual half of Fe3+occupies Td-sites in the face-centred cubic crystal structure of Fe3O4, i.e., Fe3+Oh: Fe3+Td: Fe2+Oh = 1:1:1, with the total magnetic moment per unit of (Fe3+)Td (Fe2+Fe3+)OhO4 being 4 μB [18]. Since the quantities of Fe3+ are the same at Oh-sites and Td-sites, the μ macroscopically mutually offset due to antiferromagnetic coupling, thus the net magnetic moment depends mainly on the cation present in the specific positions. Therefore, the doping of MNPs with divalent transition metal ions (Fe2+, Mn2+, Zn2+, Ni2+, Co2+, etc.) further influences the lattice occupation of cations within the face-centred cubic crystal structure [19]. In accordance with their spin structures, it can be evaluated as 5, 3 and 2 μB per unit magnetic moment for MnFe2O4, CoFe2O4 and NiFe2O4 separately, with Mn2+ exhibiting the strongest magnetic moment due to its five unpaired d-orbiting electrons [20]. The disordered arrangement of transition metal ions and iron ions induces sub-stability in TMNPs, which in turn coordinates the magnetic moment and improves the properties associated with TMNPs.

It has been found that for the same transition metal ion with different synthesis methods (e. g. co-precipitation, high temperature hydrothermal and pulsed laser deposition), the doping method changes and the optimum doping amount is different [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. Moreover, for different divalent transition metal ions with the same synthesis method, the optimum doping amount is also inconsistent. Lee et al. [20] investigated the effect of transition metal doping on the magnetic behaviour of MNPs by comparing the MS of MnFe2O4, FeFe2O4, CoFe2O4, and NiFe2O4 at 12 nm. Gabal and Bayoumy et al. [21] investigated the effect of varying cation content on the saturated magnetisation of Ni0.8-xZn0.2MgxFe2O4 (x ≤ 0.8) and Ni1-xCuxFe2O4 (x ≤ 1) nanoparticles and found that the saturation magnetization increased significantly when the non-magnetic Cu2+or Mg2+ were replaced by Ni2+ with a higher magnetic moment. In addition, in contrast with the doping of other divalent transition metal ions, Zn2+ is extremely biocompatible due to being an essential trace element with toxic measures up to 450 mg per day [22,23]. As a consequence, numerous researchers have modulated the properties of magnetic nanomaterials by doping with zinc for biological applications. For instance, Ma et al. [24] synthesized hydrophobic ZnxFe3-xO4with different Zn doping levels (x = 0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3 and 0.4) and found that the saturation magnetization reached a maximum of 66.8 emu/g at 0.2 and obtained the doping mechanism of Zn2+ in this system (Fig. 3a) . When x = 0, the antiferromagnetic coupling between Fe3+will partially disappear at Oh-sites and Td-sites; when x ≤ 0.2, Zn2+ will prefer to dominate the Td-sites, replacing part of the Fe3+ positions and for maintaining charge balance, part of Fe2+-Oh will be converted to Fe3+-Oh to keep the oxygen stoichiometry at 4, resulting in a higher overall magnetic moment, while at x ≥ 0.2, a portion of Zn2+will replace Fe3+-Td, but at higher Zn2+ doping levels, the overall magnetic moment will decrease as it tends to occupy Fe2+-Oh. And as previously reported, the different Zn-doped ferrite nanomaterials (ZnxFe3-xO4) prepared using high-temperature thermal decomposition reached a maximum saturation magnetization at Zn doping levels close to 0.4 [18].

Fig. 3.

(a) The doping mechanism of ferrite with different amounts of zinc doping in the hydrophobic phase and the variation of its total magnetic moment. Reproduced with permission [24]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. (b) The effect of Co2+doping into ferrite in the form of ion-exchange on its coercivity and blocking temperature. Reproduced with permission [10]. Copyright 2013, American Chemical Society.

Apart from the saturated magnetisation, the anisotropy (K-value) of magnetic crystals is an inherent characteristic of MNP and is mainly dependant on the specific composition and crystalline structure. Therefore, it is feasible to increase the K value significantly by using more anisotropic transition metal ions instead of iron ions, such as Co2+ and Ni2+ [10,25]. Heiss et al. [7] found that superparamagnetic blocking temperature and coercivity could be enhanced by gradually doping ferrite with Co2+ to increase the anisotropy of the magnetic crystals (Fig. 3b) .

TMNPs for bioimaging

TMNPs as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents

MRI is widely applied to the detection of various malignant lesions, tissue necrosis, and local ischaemia in clinics due to its excellent soft-tissue resolution, no radiation damage and bone artefacts, as well as multi-core and multi-parameter imaging [26,27]. However, MRI technology is designed to obtain physiological and biochemical information about the tissue by detecting the environment surrounding the water protons in tissues. It is only when the contrast between different tissues in the image is relatively strong that it is easier to identify the diseased tissue for accurate diagnosis of the disease [28]. For this reason, the imaging signal is poor and the tissue imaging resolution is limited for tissues with little difference in biophysical characteristics. Consequently, it is imperative to employ contrast enhancement techniques to enhance the contrast of the image. MNPs have been extensively studied as MRI contrast agents since the 1980s, with several MNP-based nano-agents approved for clinical MRI.

Normally it is difficult to detect patients in the early stages of cancer with conventional diagnostic tools, hence MNPs probes with high MRI contrast can play an important role in early cancer diagnosis. MNPs as an MRI contrast agent can remarkably increase the level of imaging from the current anatomical level to the molecular level, thus enabling accurate real-time imaging. The operation is based on the principle that, in the existence of an applied magnetic field (B0), MNPs are magnetised to produce a magnetic moment with an ordered magnetic field, which disturbs the spin process of hydrogen protons in the body. This interference causes an enhancement of MRI contrast, which is reflected by a stronger signal in the relevant portion of the T1–2 weighted imaging. Recently, TMNPs have been used as MRI contrast enhancers to significantly sharpen the resolution and sensitivity of MRI [18,24,[29], [30], [31], [32]].

The saturated magnetization of MNPs can be significantly increased by adjusting the doping of transition metals, which in turn is closely related to the T2-weighted imaging contrast of MRI. In this regard, precisely tuning the parameters of these nanoparticles can maximize the MRI contrast, leading to a considerable improvement in the sensitivity of MRI detection [18]. Fan et al. [29] prepared ultra-small Zn- and Mn-doped ferrite nanomaterials (UFNPs, ZnxFe3-XO4@ZnxMnyFe3-x-yO4) for T1-weighted MRI by ion-exchange method (Fig. 4a) . The Zn cores and Mn-substituted shells with optimal doping amount synergistically enhanced the T1 imaging effect of UFNPs with r1 values up to 22.2 mM−1S−1, which were 5.2 and 6.3 times higher than those of conventional ultra-small ferrite nanoparticles and clinically used gadolinium-based contrast agents (Gd-DTPA), respectively. In addition, this high-performance UFNPs nanoprobe combined with the targeted fraction AMD3100 can detect the pathological state of lung metastases in breast cancer tumour cells, which greatly improves the sensitivity of early diagnosis.

Fig. 4.

(a) Synthesis of ZnxFe3-xO4@ZnxMnyFe3-x-yO4 and its T1-weighted imaging effect at optimum Zn and Mn doping. Reproduced with permission [29]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. (b) Brain slices corresponding to several time points of 3D-MPI/2D-MRI after contrast injection. Reproduced with permission [33]. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society. (c) Dynamic monitoring of magnetothermal efficacy of manganese-doped ferrite in mice using BLI. Reproduced with permission [34]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society.

Shin et al. [30] developed an MRI T1-T2 dual-modality artefact filter (mAFIA), consisting of a manganese-containing metal-organic framework (MOF) shell and a Zn0.4Fe2.6O4 MNPs core with significant T1-T2 imaging effects, which improved the sensitivity and accuracy of early diagnosis. Later, Shin et al. [31] proposed a novel strategy related to magnetic biosensor (MRET) to exploit the phenomenon of nanoscale distance correlation by linking a superparamagnetic inhibitor (Gd-DOTA) to a paramagnetic enhancer (Zn0.4Fe2.6O4), whose T1-weighted imaging signal changes are influenced by changes in the distance, d, between the enhancer and the inhibitor. When d>dc (critical distance), the enhancer has sufficiently fast electron spin fluctuations to accelerate the water-quality sub-relaxation (presenting ON state: high T1); when d<dc, the imaging signal is weakened (presenting Off: low T1) due to slower electron spin fluctuations caused by dipole coupling between the two magnetic components. This is related to how the linker interacts with the target site location in the organism, which can cause a change in the distance [32].

Furthermore, TMNPS-based MRI technology is now widely used in combination with other imaging techniques (e.g., computed tomography (CT), optical imaging, ultrasound imaging, etc.) to achieve targeted tracking of cells and multimodal treatment of lesions [4].

TMNPs as magnetic particle imaging (MPI) tracers

MPI is an outstanding new imaging technology that has the extraordinary potential to develop into one of the effective diagnostic devices of medical imaging in the future. Gleich and Weizenecker of Philips Research in 2005 first introduced an imaging technique for MPI which utilizes an oscillating magnetic field for imaging and employs superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles as tracers [35]. Under strong magnetic gradients, the MPI signal originates from the orientation of the magnetic moment in MNPs. The local field-free point (FFP) is rasterised on the view field. And the MNPs outside the FFP are saturated and flipped for an instant when the signal is induced in the FFP by the coil in a specific position in 3D [36]. MPI has considerable advantages as an in vivo imaging modality compared to others used for detection and surveillance of disease, including tomography imaging capability, the low background of biological tissue, non-attenuation of signal in tissue, non-ionizing radiation, positively contrast analogue to nuclide imaging and a linear relationship of imaging signal to the level of tracer [37,38].

Unlike MRI, which measures changes in the magnetisation intensity of water nuclei, MPI detects changes in the electron magnetisation intensity of iron, a change 22 million times greater than the former (7T) [39]. Thus, MPI is expected to have a superior response to MRI (MPI achieved 7.8 nanograms of iron in vivo). Despite the improved sensitivity of MNP as an MRI T2 contrast agent, there are still many limitations in analysing negative contrast images of tissues with inherently poor MRI signals, such as lung and bone [40]. MPI, on the contrary, does not suffer from similar problems. In addition, comparable with single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET), MPI has minimal signal attenuation and background signal for deep tissue analysis with a spatial resolution (∼1 mm ) currently comparable to PET. In contrast, MPI trackers have steady activity since no radioactivity is required.

In 2017 Arami et al. [41] illustrated the potential of MPI for cancer imaging using targeted MNPs. In the same year, Ludewig et al. [33] demonstrated real-time imaging of blood circulation by MPI, which could revolutionise the diagnosis and treatment of stroke (Fig. 4b) . Also, the capacity of MPI for tracking cancer cells has been exemplified by Song et al. [42]. However, it is worth noting that MPI relies heavily on MNPs as tracers. Moreover, Trabesinger [35] suggested that following advances in superparamagnetic ferrite nanoparticles (SFNPs) and electronics, it is likely that the theoretical threshold of measurement for MPI will be 20 nM, compared to the existing limitation of 100 μM for commercial SFNPs. Owing to the physical differences of the MRI and MPI, it is unsuitable for MPI to adopt SFNPs developed for MRI on account of their small nucleus size (typically < 10 nm in diameter). This is why the development of magnetic tracers suitable for MPI is essential to exploit the full potential of MPI.

Sensitivity and spatial resolution are the key parameters that define the performance of MPI tracers. The magnetic behaviour of MNPs can be manipulated by doping with transition metals to optimize the resolution and sensitivity of MPI for visualizing the morphological details of tissues, which is of paramount importance for the detection and diagnosis of diseases. Bauer et al. [43] found that the signal of MPI could be intensified two-fold by doping Zn2+ into magnetite (Zn0.4Fe2.6O4). The nanomaterial provided a higher signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) than existing MPI tracers and also exhibited excellent magneto-thermal properties. Jiang et al. [44] designed extensive novel MPI trackers, including MFe2O4/C@PDA (M= Zn, Co and Mn) and γ-Fe2O3/C@PDA, of which ZnFe2O4/C@PDA showed optimal MPI behaviour in the total samples, with MPI signals that were 2.4 and 4.7 times higher than those of γ-Fe2O3/C@PDA and commercial MPI tracer (Vivotrax), respectively, which can be used to improve the detection limits of current MPI. Du et al. [34] optimised the performance of MNPs by doping manganese into ferrite and achieved the first magnetothermal therapy using dual-modality MRI/MPI image guidance (Fig. 4c).

TMNPs for oncology therapy

Magnetic targeting system drives TMNPs for drug delivery

Magnetic forces can be used to remotely trigger or direct TMNPs for specific in vivo processes, where TMNPs that respond to external magnetic fields play an important role in magnet-mediated biological applications [45], [46], [47]. Adequate aggregation of nanoparticles within the tumour is a prerequisite for the exertion of nanodrugs effect in vivo. However, drug delivery systems (DDS) inevitably suffer from bio barrier at several sites during the circulation, accumulation, penetration and internalisation of therapeutic agents into cancer cells [48,49]. Given the presence of the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) in vivo, the majority of nanoparticles cannot satisfy the criteria for freedom from ionisation effects. Thus, according to a ten-year survey of publications, it was found that the delivery of nanoparticles to tumours was generally inferior to 10% of the injected dose, with estimated median values of merely 0.7% [50]. For this reason, enhancing the accumulation of nanoparticles at the tumour site would be biologically and technically challenging.

It is possible that particular stimuli could create more promising opportunities for the insertion of molecular drugs into distal tumour cells, achieving more effective therapeutic outcomes [51]. Alongside negative and positive targeting approaches utilising internal biological mechanisms, there is a progressive development in the application of external physical forces to effectively drive nanoparticle targeting to focal sites [52]. It consists of the administration of MNPs intravenously into the body, followed by the application of AMF to specific areas [53]. Because of the strong permeability of the magnetic field to biological tissue, Magnetic targeting is likely to offer a novel endogenous physical mechanism to offset bio-barriers of DDS. In the 1960s, the concentration of MNPs flowing in blood vessels utilizing an external magnetic field was first proposed by Freeman et al. [54].

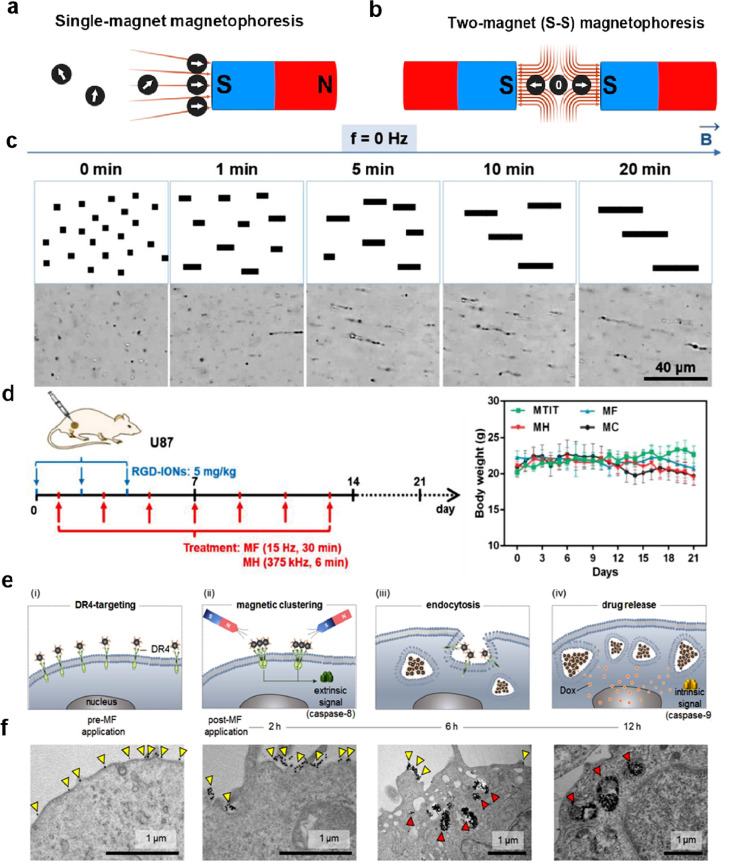

In spite of magnetic targeting systems use an exterior magnetic field to remotely control MNPs to augment their aggregation and endocytosis in vivo and have attracted widespread interest from researchers over the past decades for their drug delivery systems, this approach is currently unsuccessful in clinical studies due to problems such as inefficacy and uncontrolled allocation of MNPs [55], [56], [57]. Since conventional magnetic targeting systems typically use a sole magnet, the magnetic field gradient decreases dramatically with increasing distance from magnetic surfaces, which reduces the aggregation and endocytosis of MNPs (Fig. 5a) [58]. It has been shown that magnetic targeting is only effective when the tumour is less than 5 mm to the magnet surface, which considerably hampers the clinical implementation of this strategy [57,59]. Graeser et al. [60] first presented the use of two magnets to modulate the magnetic aggregation effect of MNPs on the manipulate of cell fate. Recently, Zhou et al. [61] developed a magnet configuration consisting of two magnets located in opposite polarisation directions (S-S), with the area requiring magnetic targeting placed between the two magnets (Fig. 5b). Remarkably, the intensity of the magnetic field within the bi-magnet setup does not have a fixed value, gradually decreases from the surface of each magnet to the centre, resulting in cyclic MNPs moving from the S-S dual magnet configuration at an almost constant rate. This customised dual-magnet device greatly enhances the aggregation and endocytosis of MNPs in solid tumour models and provides new ideas for the design of future magnetic targeting systems. Xie et al. [62] assembled 50 μm bacteriophage microrobot (BMMs) using MNPs and hydrogels under the induction of a magnetic field (280–320 Gs), mimicking the regular arrangement of magnetic vesicles in archaeal repellent magnetotactic bacteria, with a high velocity of 161.7 μm/s driven by a magnetic field, which is a promising candidate for microvascular thrombolytic targeting and controlled drug release.

Fig. 5.

(a) A conventional magnetic targeting system based on a mono-magnetic structure. (b) Dual magnet configuration with opposite S-S poles. Reproduced with permission [61]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. (c) linear self-assembly of RGD-IONs under a static magnetic field by optical images. (d) Therapeutic performance of RGD-IONs on mice with U87. Reproduced with permission [63]. Copyright 2020, John Wiley and Sons. (e) Mechanisms of m-TAT for the treatment of multidrug-resistant cancer (MDR) cells. (f) The uptake and movement of m-TAT by MDR cancer cells by Transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Reproduced with permission [64]. Copyright 2016, John Wiley and Sons.

However, there is still an enormous distance to go before precise magnetic targeting of deep human tissues can finally be applied in the clinic. For a specific type of MNP, the efficiency of magnetic targeting is highly dependant on the magnetic field configuration and the distance between the circulating MNPs and the treated target, and the magnetisation of the MNP within the magnetic localisation is driven by the AMF gradient rather than the intensity. For this reason, weak magnetic field gradients away from the magnet surface may not be capable of dragging MNPs into the target region. Furthermore, the extension of magnetic positioning systems from experimental animals to clinical patients remains a tricky challenge due to their distinctly different dimensions.

A major problem with the delivery of magnetomechanical forces mediated by TMNPs is currently that sites of effect at the cell level ought to be precisely controlled, depending on how the MNPs and cells interact with each other. Given this, it is valuable to precisely modulate the specificity and selectivity of TMNPs for targeting subcellular locations in vivo.

TMNPs for magnetic hyperthermia

Apart from cardiovascular disease, cancer is a major cause of death throughout the world [65]. Apart from surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy are the mainstays of oncology treatment. However, these options have their limitations, which may ultimately lead to suboptimal outcomes or ineffective treatment. Although all of these therapies have now achieved some technical breakthroughs, there is still an urgent need for novel treatments for cancer with superior effectiveness and safety.

Magnetic hyperthermia (MH) is currently used as an invaluable tool in biomedical research [66]. In comparison to other physical therapies such as photodynamic therapy (PDT) and photothermal therapy (PTT), MH offers significant advantages such as no penetration depth limitation and attenuation by tissue, non-invasiveness, remote controllability, nanoscale spatial resolution, and appreciable biocompatibility [67]. At present, it is well established that the use of magnetic heat is an effective means of treating tumours in vitro and in vivo [4,68].

In the use of heating by magnetism, MNPs take a predominant position by converting exterior electromagnetic energy into thermal energy using Neel-Brown relaxation [69]. The heat generated by the induction of these MNPs raises the local temperature above the normal physiological range (40 °C), denaturing the structure of proteins or disrupting cellular signalling channels, eventually causing apoptosis and necrosis of tumour cells. Additionally, the magnetothermal conversion efficiency of MNPs can be assessed by the specific loss rate (SLP, the amount of heat generated per unit mass of material per unit time under an alternating magnetic field) and specific absorption rate (SAR) [70], the relationship between which is shown in Eqs. (1) and (2).

| (1) |

| (2) |

where ∆T / ∆t is the initial slope, mM is the mass concentration of the magnetic element in the solution, c is the volumetric specific heat capacity of the solution, Vs is the volume of the sample and m is the mass of the magnetic element in the solution. The SLP is extremely dependant on the magnetic relaxation process and is approximately positively correlated with the magnetocrystalline anisotropy constant (K) and Ms, while it is adversely related to the dimensions of MNPs [71,72]. Normally, MNPs with high Ms and large coercivity (at 10 K) typically exhibit a higher SLP [73].

Nonetheless, current magnetothermal treatments regularly require the use of high doses of MNPs (typically 1‒2 M, several orders of magnitude greater than MRI contrast agents) or overly high excitation conditions (H×f > 1010A/ms) to attain therapeutic temperatures that trigger cancer cell death [68,74]. Notably, it is essential to enhance the chemical synthesis pathway of MNPs and augment magnetothermal conversion efficiency to make cancer therapy genuinely. For this purpose, doping transition metal ions into MNPs is an effective way to increase Ms and magnet crystal anisotropy [75,76]. Jang et al. [18] synthesized (ZnxFe1-x)Fe2O4 and (ZnxMn1-x)Fe2O4 and fkund that the SLP value (432 W•g−1) of (Zn0.4Mn0.6)Fe2O4 NPs was four times higher than that of commercial Feridex under the same conditions and killed 84% of HeLa cells in 10 min under AMF. Pardo et al. [77] synthesised 8.5 nm Mn2+, Co2+ and Zn2+ doped MNPs for magnetothermal therapy by pyrolysis in different combinations and ranges. The specific absorption ratio of Zn0.25Co0.29 Mn0.21Fe2.25O4 could reach 97 W•g−1 under an AMF at 850 kHz for 15 min, which was about 3 times higher than that of the undoped MNPs (37.3 W•g−1). Idoia et al. [78] prepared ZnxFe3-xO4@PEG NPs with various shapes, sizes and zinc dosage to investigate the effect of variation of zinc doping amount, size and shape on the magnetothermal conversion rate, and found that 25 nm Zn0.1Fe2.9O4@PEG could achieve the highest specific absorption under clinically safe excitation conditions (300 kHz, 60 mT) up to 1700 W/g. Jang et al. [79] fabricated a highly bio-compatible Mg-doped γ-Fe2O3 (Mg0.13-γFe2O3) nanomaterial with an unusually high-intrinsic loss of power (ILP, 14 NH m2 kg−1) approximately one hundred times superior to commercial Fe3O4 (Fe = 0.15 NH m2 kg−1).

However, the key challenge of magnetothermal therapy is not only to raise the temperature, but more importantly to control the temperature, i.e. utilizing mild heat therapy (40–45 °C) to induce apoptosis, effectively killing the tumour cells while reducing the damage to the surrounding normal tissue cells [80], [81], [82]. This has led to the development of dual-mode magnetothermal therapy, which employs anti-cancer molecules or other therapeutic means to make cancer cells more sensitive to heat, which can then be effectively killed by low concentrations or lightly heating of MNPs. For example, Yoo et al. [83] prepared a nanomaterial (RAIN) with two functional subunits (magnetothermal generators - 15 nm Zn0.4Fe2.6O4 NPs and heat shock protein suppressor), both of which were triggered only under an alternating magnetic field. And they proved that RAIN at hypothermia (i.e. 43 °C) can boost the apoptosis of cancer cells through thermal and gelatine release around the same time. Wu et al. [63] synthesised an RGD-modified Zn0.4Fe2.6O4 NPs (RGD-IONs) for the synergistic treatment of magnetomechanical forces and magnetothermal. The material can achieve self-assemble at a rotating magnetic field (RMF, 15 Hz) to form linear aggregates while generating ROS to enhance the thermal sensitization of tumour cells (Fig. 5c). The assembled RGD-IONs can then generate further moderate heat to kill sensitised cancer cells under RMF (375 kHz). It has been shown experimentally that only 43.6 °C is required to effectively control cancer cell death (Fig. 5d). Yin et al. [84] reported a novel strategy for specific activation of genes in stem cells through mild magnetic thermotherapy. In the study, they synthesized a compound consisting of ZnFe2O4 core and mesoporous silica shell for stimulating the delivery and activation of heat-inducible gene carriers in engineered stem cells, with the goal of achieving a molecular level of gene activation.

In principle, TMNPs, when combined with functional molecules such as antibodies, chemotherapeutic agents, aptamers, siRNAs and cell-penetrating peptides, can be a multifunctional plateau for the inherent long-range regulation of cellular activity with no penetration depth limitations and molecular level specificity. Given these characteristics, there is significant potential for the magnetic heating of MNPs to expand the objective from the individual cell level to the entire body, which allows for superior comprehension and accurate manipulation of biosystems.

TMNPs for magnetic mechanotransduction (MMT) to regulate cellular activity

MNPs take a crucial position in recognising magnetic fields and transferring signals into mechanical forces [85]. Mechanotransduction based on MNPs for cancer treatment is an emerging area of research with considerable potential for developmental applications [86]. MMT relies primarily on MNPs to transform the mechanical stimuli into biochemical signals that trigger various cellular reactions, such as differentiation, proliferation [87] and death [88].

Over the last decade, research related to mechanobiology has shown that mechanical stimuli have a significant impact on the physiological condition of cells [89]. Notably, functional MNPs with modifiable magnetic and surface properties are the material support for generating mechanical forces, targeting mechanosensitive proteins as well as permit non-invasive manipulation in biosystems. Therefore, ferromagnetic MNPs with a high magnetization are often preferred as intermediate materials for mechanical transduction [90]. In contrast to other technological approaches to study mechanic transduction (e.g., atomic force microscopy, optical tweezers), force mechanic transduction based on functional MNPs to regulate cell fate offers a new approach to non-invasive physical therapy of cancer due to the spatio-temporal controllability and deep tissue penetration of magnetic fields [91,92]. The magnetic moment is one of the critical intrinsic parameters for the generation of mechanical forces by MNPs. For this purpose, the magnetic moment of MNPs can be improved by means of composition optimisation methods such as doping, element selection and cation distribution. Besides, its magnetic domains rearrange or continually grow under the effect of the AMF and possess a certain net μ under no AMF.

Since transition metal-doped magnetic nanomaterials have relatively high Ms and thus respond effectively to external magnetic fields, which can take full advantage of changes in the strength and direction of external dynamic magnetic fields to modulate the movement of MNPs and generate a certain mechanical force to destroy tumour cells. One of the straightforward ways to eliminate cancer cells is to burst the cell membrane by strong oscillations by MNPs. Chenyang et al. [93] recently proposed a non-invasive and remotely controlled mechanochemical treatment method. Under the action of a low strength (45 mT) rotating magnetic field (RMF), the DOX- Zn0.2Fe2.8O4-PLGA superparamagnetic composite undergoes mechanical motion to control the release of chemotherapeutic anticancer drugs and to achieve controlled tumour treatment by precise manipulation of mechanical forces applied to the cell membrane. This synergistic treatment of chemotherapy and magneto-mechanical forces significantly boosts the killing effect of MCF-7 on tumour cells. A variety of bioactivities involve substantial aggregation of membrane acceptors to trigger stress-like responses. In this way, by modelling and exploiting this case, mechano-mechanical forces are being used as a promising pathway to aggregate receptors and initiate biochemical signals downstream to modulate cell behaviour, which applies to signals that activate apoptosis. In 2012, Cho et al. [64] developed a challenging strategy in which they used MNPs to remotely activate cell death signalling pathways and successfully converted force signals into biochemical signals. In the study, a 15 nm Zn0.4Fe2.6O4 was bound to a death receptor 4 (DR4) monoclonal antibody as a magnetic switch (m-TAT), which specifically interacts on the surface of colon cancer tumour cell membranes to promote the DR4 aggregation process (Fig. 5e, f). This mimics the apoptotic process associated with apoptosis-inducing tumour necrosis factor (TNF), to induce the expression of ligands (TRAIL) to promote apoptosis in cancer cells. It can be seen that the forces generated by MNPs in the presence of a magnetic field can be used as an effective means of triggering the passive aggregation of various receptors on the cell membrane and that the ligand molecules can be precisely engineered to activate a particular signalling pathway, and further modulating cell fate.

Furthermore, MNPs are also frequently used to deliver mechanical forces to organelles that activate cellular signalling pathways and lead to the destruction of targeted cancer cells. Relevant studies have shown that the shear force generated by the rotation of MNPs under a rotating external magnetic field can increase the permeability of the lysosomal membrane and release internal hydrolases, thus increasing the acidic environment of the cytoplasm and enabling it to trigger apoptosis in cancer cells [94]. Alternatively, MNPs decorated with epidermal growth factor (EGF) can destabilize lysosomal membranes and trigger programmed death pathways that destroy tumour cells under alternating magnetic fields [94]. Notably, mitochondria are important regulators of the apoptotic pathway by regulating the transport from the intracellular space to the cytoplasm, including pro-apoptotic proteins, and provide a central target for magnet mechanically stimulated apoptosis. Chen et al. [95] recently synthesised a 20 nm mitochondria-targeting Zn0.4Fe2.6O4 NPs, which effectively targeted the mitochondria of cancer cells and assembled linearly into an aggregate up to the 100 PN level under an applied spin magnetic field (RMF-15 Hz, 40mT). Due to the direct force exerted on the mitochondria, it causes a mechanical signal to initiate the apoptotic process resulting in effective cancer cell damage.

Conclusion

The magnetic behaviour of MNPs is dependant on several interrelated parameters. The results of many studies have shown a significant link between certain magnetic behaviour of MNPs (relaxation time, blocking temperature, coercivity and saturated magnetisation) and the physical characteristics of the transition metal doping. Therefore, the aim of optimising the properties of MNPs for practical applications is achieved by means of rational modulation. amongst the biomedical applications of TMNPs, biomedical imaging is developing rapidly with a high degree of technological maturity, e.g., T2 contrast agents have been widely available for clinical MRI. However, how to improve MRI contrast (e.g., cardiac and cerebral angiography), increase its blood circulation time, target the lesion precisely, enhance biocompatibility and at the same time metabolise the contrast agents out of the organism are the key challenges hitherto. Furthermore, MPI research has been focusing on the development of instrument hardware. This series of instruments can achieve a spatial resolution of <1 mm in seconds, comparable to the imaging accuracy of CT and ultrasound technologies, and also has the advantage of high sensitivity compared to PET and SPECT technologies, which will certainly be widely used in the field of medical imaging in the future.

Nevertheless, the recent findings of TMNPs in drug delivery and oncological therapy have been controversial [96]. Particularly a ferritin made of protein complexe containing iron atoms has been demonstrated as a magnetic bioprotein compass which isvery sensitive to magnetic fields [97]. Unlike the magnetite particles in magnetostrophic bacteria, the iron nuclei of the ferritin is too small (∼5 nm) to maintain a permanent dipole moment (blocking temperature ∼40 K) [98]. In addition, physical calculations have revealed some magnetic effects, such as force, torque and heat, which are generated by magnetic proteins. However, magnetic drive mechanisms acting at the cellular level are not compatible. On this basis, more magnetically responsive TMNPs are required to generate the required forces under this phenomenon. Furthermore, the main challenge facing TMNPs as mediators for the delivery of magneto-mechanical forces is the difficulty of achieving precise control of the site of effect at the cellular level, which depends on the mode of interaction between TMNPs and cells. Therefore, the development of smart responsive TMNPs-based nanomedicines for the treatment of tumours, and the precise targeting of focal sites and the enrichment of nanomedicines at lesion sites are critical directions for future development.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hui Du: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Ozioma Udochukwu Akakuru: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Chenyang Yao: Writing – original draft. Fang Yang: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Aiguo Wu: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFA0405603, 2018YFC0910601), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31971292, 51803228, 51873225), the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences Grant No. XDB36000000, Key Scientific and Technological Special Project of Ningbo City (2017C110022), Funding in Ningbo city (2020Z094), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2020C03110), and Ningbo Natural Science Foundation of China (2019A610192).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101264.

Contributor Information

Fang Yang, Email: yangf@nimte.ac.cn.

Aiguo Wu, Email: aiguo@nimte.ac.cn.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Hu Y., Mignani S., Majoral J.P., Shen M., Shi X. Construction of iron oxide nanoparticle-based hybrid platforms for tumor imaging and therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018;47:1874–1900. doi: 10.1039/c7cs00657h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poon W., Kingston B.R., Ouyang B., Ngo W., Chan W.C.W. A framework for designing delivery systems. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020;15:819–829. doi: 10.1038/s41565-020-0759-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J., Li Y., Nie G. Multifunctional biomolecule nanostructures for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021:1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41578-021-00315-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee N., Yoo D., Ling D., Cho M.H., Hyeon T., Cheon J. Iron oxide based nanoparticles for multimodal imaging and magnetoresponsive therapy. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:10637–10689. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu X., Zhang Y., Wang Y., Zhu W., Li G., Ma X., Zhang Y., Chen S., Tiwari S., Shi K., et al. Comprehensive understanding of magnetic hyperthermia for improving antitumor therapeutic efficacy. Theranostics. 2020;10:3793–3815. doi: 10.7150/thno.40805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morales M.P., Veintemillas-Verdaguer S., Montero M.I., Serna C.J., Roig A., Casas L., Martínez B., Sandiumenge F. Surface and Internal Spin Canting in γ-Fe 2 O 3 Nanoparticles. Chem. Mater. 1999;11:3058–3064. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolhatkar A.G., Jamison A.C., Litvinov D., Willson R.C., Lee T.R. Tuning the magnetic properties of nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:15977–16009. doi: 10.3390/ijms140815977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akg A., Mg B. Synthesis and surface engineering of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3995–4021. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.10.012. ScienceDirect. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willard M.A., Kurihara L.K., Carpenter E.E., Calvin S., Harris V.G. Chemically prepared magnetic nanoparticles. Metall. Rev. 2010;49:125–170. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sytnyk M., Kirchschlager R., Bodnarchuk M.I., Primetzhofer D., Kriegner D., Enser H., Stangl J., Bauer P., Voith M., Hassel A.W., et al. Tuning the magnetic properties of metal oxide nanocrystal heterostructures by cation exchange. Nano Lett. 2013;13:586–593. doi: 10.1021/nl304115r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lacheisserie dTd, Gignoux D., Schlenker M., Phenomenology of magnetism at the microscopic scale,Magnetism. (2002) 105-142.

- 12.Jeong U., Teng X., Wang Y., Yang H., Xia Y. Superparamagnetic colloids: controlled synthesis and niche applications. Adv. Mater. 2007;19:33–60. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mcintyre D. Critical size of magnetic particles with high uniaxial anisotropy. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. 1967;302:99–112. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kittel C. Physical theory of ferromagnetic domains. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1949;21:541–583. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bogdanov A.N. Magnetic domains. the analysis of magnetic microstructures. Low Temp. Phys. 1999;25:151–152. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams A.R., Moruzzi V.L., Gelatt C.D., Kübler J., Schwarz K. Aspects of transition-metal magnetism. J. Appl. Phys. 1982;53:2019–2023. [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Handley R.C., CO'Handley R. Wiley-VCH; 1999. Modern magnetic materials: principles and applications; p. 768. by ISBN 0-471-15566-7November 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jang J.T., Nah H., Lee J.H., Moon S.H., Kim M.G., Cheon J. Critical enhancements of MRI contrast and hyperthermic effects by dopant-controlled magnetic nanoparticles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2009;48:1234–1238. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu C., Zou B., Rondinone A.J., Zhang Z.J. Chemical control of superparamagnetic properties of magnesium and cobalt spinel ferrite nanoparticles through atomic level magnetic couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:6263–6267. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee J.H., Huh Y.M., Jun Y.W., Seo J.W., Jang J.T., Song H.T., Kim S., Cho E.J., Yoon H.G., Suh J.S., et al. Artificially engineered magnetic nanoparticles for ultra-sensitive molecular imaging. Nat. Med. 2007;13:95–99. doi: 10.1038/nm1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gabal M.A., Bayoumy W.A. Effect of composition on structural and magnetic properties of nanocrystalline Ni0.8−xZn0.2MgxFe2O4 ferrite. Polyhedron. 2010;29:2569–2573. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraga C.G. Relevance, essentiality and toxicity of trace elements in human health. Mol. Asp. Med. 2005;26:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landsiedel R., Ma-Hock L., Kroll A., Hahn D., Schnekenburger J., Wiench K., Wohlleben W. Testing metal-oxide nanomaterials for human safety. Adv. Mater. 2010;22:2601–2627. doi: 10.1002/adma.200902658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma Y., Xia J., Yao C., Yang F., Stanciu S.G., Li P., Jin Y., Chen T., Zheng J., Chen G., et al. Precisely tuning the contrast properties of znxfe3–xo4 nanoparticles in magnetic resonance imaging by controlling their doping content and size. Chem. Mater. 2019;31:7255–7264. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fantechi E., Campo G., Carta D., Corrias A., Sangregorio C. Exploring the effect of Co doping in fine maghemite nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2012;116:8261. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee N., Hyeon T. Designed synthesis of uniformly sized iron oxide nanoparticles for efficient magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012 doi: 10.1039/c1cs15248c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willmann J.K., Bruggen N.V., Dinkelborg L.M., Gambhir S.S. Molecular imaging in drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2008;7:591–607. doi: 10.1038/nrd2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kircher M.F., Willmann J.K. Molecular body imaging: MR imaging, CT, and US. Part I. principles. Radiology. 2012;263:633–643. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12102394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miao Y., Zhang H., Cai J., Chen Y., Ma H., Zhang S., Yi J.B., Liu X., Bay B.H., Guo Y., et al. Structure-relaxivity mechanism of an ultrasmall ferrite nanoparticle T1 MR contrast agent: the impact of dopants controlled crystalline core and surface disordered shell. Nano Lett. 2021;21:1115–1123. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c04574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shin T.H., Choi J.S., Yun S., Kim I.S., Cheon J. T-1 and T-2 Dual-Mode MRI contrast agent for enhancing accuracy by engineered nanomaterials. ACS Nano. 2014;8 doi: 10.1021/nn405977t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shin T.H., Kang S., Park S., Choi J.S., Kim P.K., Cheon J. A magnetic resonance tuning sensor for the MRI detection of biological targets. Nat. Protoc. 2018;13:2664–2684. doi: 10.1038/s41596-018-0057-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choi J.S., Kim S., Yoo D., Shin T.H., Kim H., Gomes M.D., Kim S.H., Pines A., Cheon J. Distance-dependent magnetic resonance tuning as a versatile MRI sensing platform for biological targets. Nat. Mater. 2017;16:537–542. doi: 10.1038/nmat4846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ludewig P., Gdaniec N., Sedlacik J., Forkert N.D., Szwargulski P., Graeser M., Adam G., Kaul M.G., Krishnan K.M., Ferguson R.M., et al. Magnetic particle imaging for real-time perfusion imaging in acute stroke. ACS Nano. 2017;11:10480–10488. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b05784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Du Y., Liu X., Liang Q., Liang X.J., Tian J. Optimization and design of magnetic ferrite nanoparticles with uniform tumor distribution for highly sensitive mri/mpi performance and improved magnetic hyperthermia therapy. Nano Lett. 2019;19:3618–3626. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b00630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trabesinger A. Particular magnetic insights. Nature. 2005;435:1173–1174. doi: 10.1038/4351173a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodwill P.W., Saritas E.U., Croft L.R., Kim T.N., Krishnan K.M., Schaffer D.V., Conolly S.M. X-space MPI: magnetic nanoparticles for safe medical imaging. Adv. Mater. 2012;24:3870–3877. doi: 10.1002/adma.201200221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pablico-Lansigan M.H., Situ S.F., Samia A. Magnetic particle imaging: advancements and perspectives for real-time in vivo monitoring and image-guided therapy. Nanoscale. 2013;5:4040–4055. doi: 10.1039/c3nr00544e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Talebloo N., Gudi M., Robertson N., Wang P. Magnetic particle imaging: current applications in biomedical research. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2019 doi: 10.1002/jmri.26875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lemaster J.E., Chen F., Kim T., Hariri A., Jokerst J.V. Development of a trimodal contrast agent for acoustic and magnetic particle imaging of stem cells. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018;1:1321–1331. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.8b00063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu L., Mendoza-Garcia A., Li Q., Sun S. Organic phase syntheses of magnetic nanoparticles and their applications. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:10473–10512. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arami H., Teeman E., Troksa A., Bradshaw H., Saatchi K., Tomitaka A., Gambhir S.S., Hafeli U.O., Liggitt D., Krishnan K.M. Tomographic magnetic particle imaging of cancer targeted nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2017;9:18723–18730. doi: 10.1039/c7nr05502a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song G., Chen M., Zhang Y., Cui L., Qu H., Zheng X., Wintermark M., Liu Z., Rao J. Janus iron oxides @ semiconducting polymer nanoparticle tracer for cell tracking by magnetic particle imaging. Nano Lett. 2018;18:182–189. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b03829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bauer L.M., Situ S.F., Griswold M.A., Samia A.C. High-performance iron oxide nanoparticles for magnetic particle imaging - guided hyperthermia (hMPI) Nanoscale. 2016;8:12162–12169. doi: 10.1039/c6nr01877g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang Z., Han X., Du Y., Li Y., Li Y., Li J., Tian J., Wu A. Mixed metal metal-organic frameworks derived carbon supporting ZnFe2O4/C for high-performance magnetic particle imaging. Nano Lett. 2021;21:2730–2737. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c04455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jordan A., Scholz R., Wust P., Fahling H., Rolix R. Applications of magnetic nanoparticles in biomedicine. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2014;201:413–418. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee J.H., Kim J.W., Levy M., Kao A., Noh S.H., Bozovic D., Cheon J. Magnetic nanoparticles for ultrafast mechanical control of inner ear hair cells. ACS Nano. 2014;8:6590–6598. doi: 10.1021/nn5020616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feng Q., Liu Y., Huang J., Chen K., Huang J., Xiao K. Uptake, distribution, clearance, and toxicity of iron oxide nanoparticles with different sizes and coatings. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:2082. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-19628-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pino P., Pelaz B., Zhang Q., Maffre P., Nienhaus G.U., Parak W. Protein corona formation around nanoparticles – from the past to the future. Mater. Horiz. 2013;1:301–313. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pu C.K., Lin S., Parak W.J., Davis T.P., Caruso F. A decade of the protein corona. ACS Nano. 2017;11:11773–11776. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b08008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilhelm S., Tavares A.J., Dai Q., Ohta S., Audet J., Dvorak H.F., Chan W.C.W. Analysis of nanoparticle delivery to tumours. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016;1:16014. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muntimadugu E., Jain A., Khan W. Targeted Drug Delivery: Concepts and Design. Springer International Publishing; 2015. Stimuli Responsive Carriers: Magnetically, Thermally and pH Assisted Drug Delivery; pp. 341–365. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qiu Y., Tong S., Zhang L., Sakurai Y., Myers D.R., Hong L., Lam W.A., Bao G. Magnetic forces enable controlled drug delivery by disrupting endothelial cell-cell junctions. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15594. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cole A.J., David A.E., Wang J., Galbán C., Hill H.L., Yang V.C. Polyethylene glycol modified, cross-linked starch-coated iron oxide nanoparticles for enhanced magnetic tumor targeting. Biomaterials. 2011;32:2183–2193. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Freeman M.W., Arrott A., Watson J.H.L. Magnetism in Medicine. J. Appl. Phys. 1960;31:S404–S405. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun C., Lee J., Zhang M. Magnetic nanoparticles in MR imaging and drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60(11):1252–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lübbe A., Bergemann C. (1997). Selected Preclinical and First Clinical Experiences with Magnetically Targeted 4′-Epidoxorubicin in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors Springer US.

- 57.Lubbe A.S., Alexiou C., Bergemann C. Clinical applications of magnetic drug targeting. J. Surg. Res. 2001;95:200–206. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2000.6030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rotariu O., Strachan N.J.C. Modelling magnetic carrier particle targeting in the tumor microvasculature for cancer treatment. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2005;293:639–646. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alexiou C., Arnold W., Klein R.J., Parak F.G., Hulin P., Bergemann C., Erhardt W., Wagenpfeil S., Lubbe A.S. Locoregional cancer treatment with magnetic drug targeting. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6641–6648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Graeser M., Thieben F., Szwargulski P., Werner F., Gdaniec N., Boberg M., Griese F., Moddel M., Ludewig P., van de Ven D., et al. Human-sized magnetic particle imaging for brain applications. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1936. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09704-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou Z., Shen Z., Chen X. Tale of two magnets: an advanced magnetic targeting system. ACS Nano. 2019;14:7–11. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.9b06842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xie M., Zhang W., Fan C., Wu C., Feng Q., Wu J., Li Y., Gao R., Li Z., Wang Q., et al. Bioinspired soft microrobots with precise magneto-collective control for microvascular thrombolysis. Adv. Mater. 2020;32 doi: 10.1002/adma.202000366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu J., Ning P., Gao R., Feng Q., Shen Y., Zhang Y., Li Y., Xu C., Qin Y., Plaza G.R., et al. Programmable ROS-mediated cancer therapy via magneto-inductions. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 2020;7 doi: 10.1002/advs.201902933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cho M.H., Kim S., Lee J.H., Shin T.H., Yoo D., Cheon J. Magnetic tandem apoptosis for overcoming multidrug-resistant cancer. Nano Lett. 2016;16:7455–7460. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b03122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R.L., Torre L.A., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Noh S-h, Moon S.H., Shin T.-.H., Lim Y., Cheon J. Recent advances of magneto-thermal capabilities of nanoparticles: from design principles to biomedical applications. Nano Today. 2017;13:61–76. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marmugi L., Renzoni F. Optical magnetic induction tomography of the heart. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:23962. doi: 10.1038/srep23962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thiesen B., Jordan A. Clinical applications of magnetic nanoparticles for hyperthermia. Int. J. Hyperth. 2008;24:467–474. doi: 10.1080/02656730802104757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rudolf H., Silvio D., Robert M., Matthias Z. Magnetic particle hyperthermia: nanoparticle magnetism and materials development for cancer therapy. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2006;18:S2919. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Guardia P., Corato R.D., Lartigue L., Wilhelm C., Espinosa A., Garcia-Hernandez M., Gazeau F., Manna L., Pellegrino T. Water-soluble iron oxide nanocubes with high values of specific absorption rate for cancer cell hyperthermia treatment. ACS Nano. 2012;6:3080–3091. doi: 10.1021/nn2048137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Obaidat I.M., Issa B., Haik Y. Magnetic properties of magnetic nanoparticles for efficient hyperthermia. Nanomaterials. 2015;5:63–89. doi: 10.3390/nano5010063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fortin J.P., Wilhelm C., Servais J., Ménager C., Bacri J.C., Gazeau F. Size-sorted anionic iron oxide nanomagnets as colloidal mediators for magnetic hyperthermia. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:2628–2635. doi: 10.1021/ja067457e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu T.Y., Hu S.H., Liu D.M., Chen S.Y., Chen I.W. Biomedical nanoparticle carriers with combined thermal and magnetic responses. Nano Today. 2009;4:52–65. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kossatz S., Ludwig R., Dahring H., Ettelt V., Rimkus G., Marciello M., Salas G., Patel V., Teran F.J., Hilger I. High therapeutic efficiency of magnetic hyperthermia in Xenograft models achieved with moderate temperature dosages in the tumor area. Pharm. Res. 2014;31:3274–3288. doi: 10.1007/s11095-014-1417-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Das P., Colombo M., Prosperi D. Recent advances in magnetic fluid hyperthermia for cancer therapy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2019;174:42–55. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2018.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lee J.H., Jang J.T., Choi J.S., Moon S.H., Noh S.H., Kim J.W., Kim J.G., Kim I.S., Park K.I., Cheon J. Exchange-coupled magnetic nanoparticles for efficient heat induction. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011;6:418–422. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pardo A., Pelaz B., Gallo J., Bañobre-López M., Parak W.J., Barbosa S., del Pino P., Taboada P. Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of superparamagnetic doped ferrites as potential therapeutic nanotools. Chem. Mater. 2020;32:2220–2231. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Castellanos-Rubio I., Arriortua O., Marcano L., Rodrigo I., Iglesias-Rojas D., Barón A., Olazagoitia-Garmendia A., Olivi L., Plazaola F., Fdez-Gubieda M.L., et al. Shaping up zn-doped magnetite nanoparticles from mono- and bimetallic oleates: the impact of Zn content, Fe vacancies, and morphology on magnetic hyperthermia performance. Chem. Mater. 2021;33:3139–3154. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.0c04794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jang J.T., Lee J., Seon J., Ju E., Kim M., Kim Y.I., Kim M.G., Takemura Y., Arbab A.S., Kang K.W., et al. Giant magnetic heat induction of magnesium-doped gamma-Fe2O3 superparamagnetic nanoparticles for completely killing tumors. Adv. Mater. 2018;30 doi: 10.1002/adma.201704362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Van D. Heating the patient: a promising approach? [DOI] [PubMed]

- 81.Fajardo L.F. Pathological effects of hyperthermia in normal tissues. Cancer Res. 1984;44:4826s–4835s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hilger I., Hiergeist R., Hergt R., Winnefeld K., Kaiser W.A. Thermal ablation of tumors using magnetic nanoparticles: an in vivo feasibility study. Invest. Radiol. 2002;37:580–586. doi: 10.1097/00004424-200210000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yoo D., Jeong H., Noh S.H., Lee J.H., Cheon J. Magnetically triggered dual functional nanoparticles for resistance-free apoptotic hyperthermia. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2013;52:13047–13051. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yin P.T., Shah S., Pasquale N.J., Garbuzenko O.B., Minko T., Lee K.B. Stem cell-based gene therapy activated using magnetic hyperthermia to enhance the treatment of cancer. Biomaterials. 2016;81:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Müller D.J., Helenius J., Alsteens D., Dufrêne Y.F. Force probing surfaces of living cells to molecular resolution. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:383–390. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cheng Y., Muroski M.E., Petit D., Mansell R., Vemulkar T., Morshed R.A., Han Y., Balyasnikova I.V., Horbinski C.M., Huang X., et al. Rotating magnetic field induced oscillation of magnetic particles for in vivo mechanical destruction of malignant glioma. J. Control. Release. 2016;223:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xia Y., Sun J., Zhao L., Zhang F., Liang X.J., Guo Y., Weir M.D., Reynolds M.A., Gu N., Xu H.H.K. Magnetic field and nano-scaffolds with stem cells to enhance bone regeneration. Biomaterials. 2018;183:151–170. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gahl T.J., Kunze A. Force-mediating magnetic nanoparticles to engineer neuronal cell function. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:299. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Golovin Y.I., Klyachko N.L., Majouga A.G., Sokolsky M., Kabanov A.V. Theranostic multimodal potential of magnetic nanoparticles actuated by non-heating low frequency magnetic field in the new-generation nanomedicine. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2017;19 [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yun H.M., Ahn S.J., Park K.R., Kim M.J., Kim J.J., Jin G.Z., Kim H.W., Kim E.C. Magnetic nanocomposite scaffolds combined with static magnetic field in the stimulation of osteoblastic differentiation and bone formation. Biomaterials. 2016;85:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang E., Kircher M.F., Koch M., Eliasson L., Goldberg S.N., Renstr?M E. Dynamic magnetic fields remote-control apoptosis via nanoparticle rotation. ACS Nano. 2014;8:3192–3201. doi: 10.1021/nn406302j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wu C., Shen Y., Chen M., Wang K., Li Y., Cheng Y. Recent advances in magnetic-nanomaterial-based mechanotransduction for cell fate regulation. Adv. Mater. 2018;30 doi: 10.1002/adma.201705673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chenyang Y., Fang Y., Li S., Yuanyuan M., Stanciu S.G., Zihou L., Chuang L., Akakuru O.U., Lipeng X., Norbert H., et al. Magnetically switchable mechano-chemotherapy for enhancing the death of tumour cells by overcoming drug-resistance. Nano Today. 2020;35 [Google Scholar]

- 94.Domenech M., Marrero-Berrios I., Torres-Lugo M., Rinaldi C. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization by targeted magnetic nanoparticles in alternating magnetic fields. ACS Nano. 2013;7:5091. doi: 10.1021/nn4007048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chen M., Wu J., Ning P., Wang J., Ma Z., Huang L., Plaza G.R., Shen Y., Xu C., Han Y., et al. Remote control of mechanical forces via mitochondrial-targeted magnetic nanospinners for efficient cancer treatment. Small. 2020;16 doi: 10.1002/smll.201905424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Markus M. Physical limits to magnetogenetics. Elife. 2016 doi: 10.7554/eLife.17210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Boles M.A., Ling D., Hyeon T., Talapin D.V. Erratum: the surface science of nanocrystals. Nat. Mater. 2016;15:364. doi: 10.1038/nmat4526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Papaefthymiou G.C. The Mossbauer and magnetic properties of ferritin cores. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta Gener. Subj. 2010;1800:886–897. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.