Abstract

This cohort study of children in a single day care examines their ability to correctly identify emotions of caregivers with and without face masks.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, health policy requires staff working in preschool education to wear face masks. This has prompted worries about the ability of young children to recognize emotions and the possible impact on their development. Without face masks, preschoolers aged 36 to 72 months had a rate of correctly identified emotions on pictures of 11.8% to 13.1%.1 Recent studies using photographs with digitally added face masks showed that participants had worse emotional recognition of the images with face masks; the first of these2 tested preschoolers on a smartphone at home, and the second3 tested children aged 7 to 13 years. We therefore aimed to study the role of actual face masks on the recognition of joy, anger, and sadness in younger preschool children.

Methods

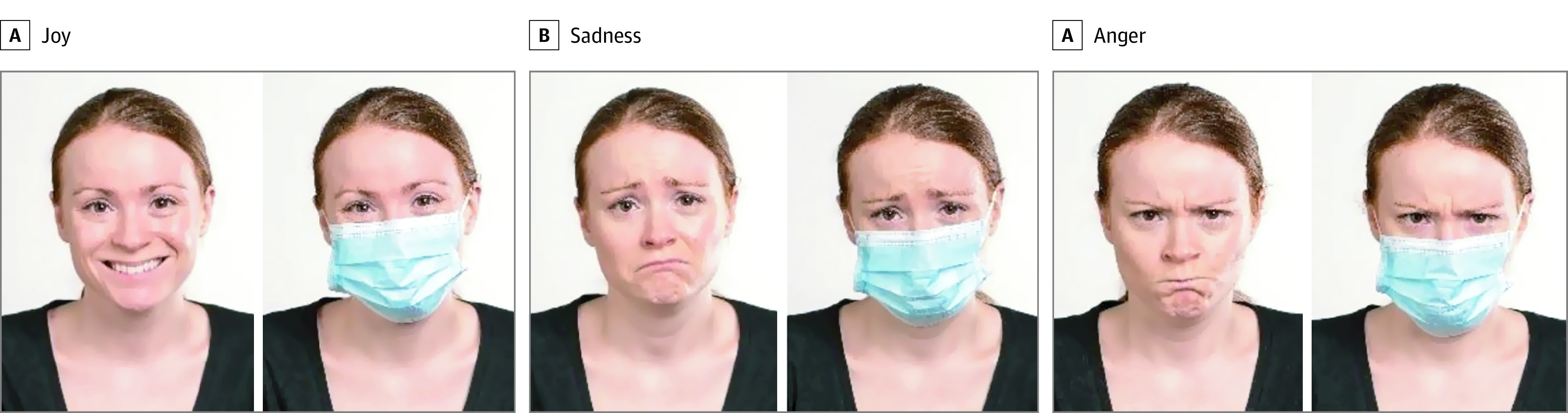

The primary outcome of this cross-sectional experimental study was the rate of correct responses using pictures of adults displaying joy, anger, or sadness. With 15 actors with and without a surgical face mask (10 women and 5 men, based on demographic information of childminders in local public day care centers), we created a data set of 90 pictures displaying joy, anger, or sadness (Figure 1). We built the experiment with E-Prime version 3.0 (Psychology Software Tools). The ethics committee for human research of the Canton Vaud approved the study and accepted that, given the pandemic situation, consent could be waived. Parents of children attending public day care centers received written, oral, and filmed information, with the possibility to opt out. Children aged 36 to 72 months without a treated neurodevelopmental impairment were eligible to participate. They sat in front of a computer, with a known caretaker if they wanted, and a trained pediatrician randomly showed the 90 pictures. Children could either name the emotion, point on a card showing emoticons of these 3 emotions, or choose the response options “I don’t know” or “Quit the experiment.” The responses of children who stopped the session prematurely were included in analyses. The statistical analysis included a comparison of the correct response rates in the different conditions with χ2 tests and bias-corrected Cramer V to calculate effect sizes. Data were analyzed with SPSS Statistics version 27 (IBM) and R studio version 1.3.1093 using R version 4.1.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Figure 1. Facial Expressions.

Results

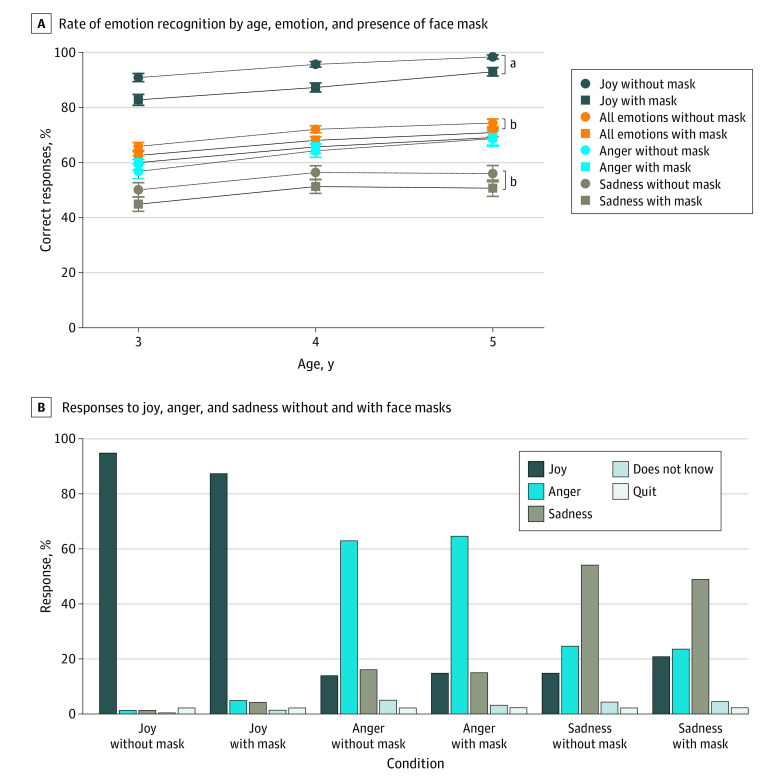

Data were collected in 9 public day care centers. The sample consisted of 276 children (girls: 135 [48.9%]; mean [SD] age, 52.4 [9.6] months). The test lasted a median (IQR) of 6.74 (4.22-9.26) minutes per child. The rate of “I don’t know” responses was 3.1% (n = 781), and 551 responses (2.2%) were “Quit the experiment.” The global correct response rate was 68.8%: 70.6% without face mask vs 66.9% with face mask (χ21 = 37.783; P < .001; V, 0.0385 [95% CI, 0.0266-0.0515]), with a difference for joy (94.8% vs 87.3%; χ21 = 140.260; P < .001; V, 0.1301 [95% CI, 0.1090-0.1521]) and sadness (54.1% vs 48.9%; χ21 = 21.937; P < .001; V, 0.0505 [95% CI, 0.0266-0.0515]) but not anger (62.2% vs 64.6%; χ21 = 2.7094; P = .10; V, 0.0147 [95% CI, 0-0.0399]). There was no difference between boys and girls. The rate of correct responses increased with age (χ22 = 136.680; P < .001; V, 0.07363 [95% CI, 0.0615-0.0864]; Figure 2A). Finally, the analysis of the mistakes showed that up to 1018 preschoolers (25%) confused anger and sadness and 862 (21%) answered joy for anger or sadness (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Correct Responses.

A, Percentage of mean correct responses for each emotion, age, and condition. B, Percentage of different responses for each emotion and condition.

Discussion

Actual face masks depicted in static pictures were significantly associated with emotion recognition in healthy preschool children, although differences were small and effect sizes were weak (Cramer V ≤0.2). Joy was more often recognized and mistakenly chosen for anger or sadness, probably because of a positivity bias in children.4,5 Overall, participants in this study, who had been exposed to face masks for nearly a year, recognized emotions on pictures better than has been reported in previous research, even with face masks.1,5 This study has several limitations, including the generalizability of its findings using static pictures instead of live actors and the validity of the outcomes. Investigating the role of face masks in other aspects of development and with children with developmental issues remains important, particularly in the wake of a fourth wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

- 1.Covic A, von Steinbüchel N, Kiese-Himmel C. Emotion recognition in kindergarten children. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2020;72(4):273-281. doi: 10.1159/000500589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gori M, Schiatti L, Amadeo MB. Masking emotions: face masks impair how we read emotions. Front Psychol. 2021;12:669432. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.669432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruba AL, Pollak SD. Children’s emotion inferences from masked faces: implications for social interactions during COVID-19. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0243708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia SE, Tully EC. Children’s recognition of happy, sad, and angry facial expressions across emotive intensities. J Exp Child Psychol. 2020;197:104881. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2020.104881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen TT, Nelson NL. Winners and losers: recognition of spontaneous emotional expressions increases across childhood. J Exp Child Psychol. 2021;209:105184. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2021.105184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]