Abstract

Objective

To review and recommend patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures assessing multidimensional domains of quality of life (QoL) to use as clinical endpoints in medical and psychosocial trials for children and adults with neurofibromatosis (NF) type 1, NF2, and schwannomatosis.

Methods

The PRO working group of the Response Evaluation in Neurofibromatosis and Schwannomatosis (REiNS) International Collaboration used systematic methods to review, rate, and recommend existing self-report and parent-report PRO measures of generic and disease-specific QoL for NF clinical trials. Recommendations were based on 4 main criteria: patient characteristics, item content, psychometric properties, and feasibility.

Results

The highest-rated generic measures were (1) the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) Generic Core Scales for NF clinical trials for children or for children through adults, (2) the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General for adult medical trials, and (3) the World Health Organization Quality of Life–BREF for adult psychosocial trials. The highest-rated disease-specific measures were (1) the PedsQL NF1 Module for NF1 trials, (2) the NF2 Impact on Quality of Life Scale for NF2 trials, and (3) the Penn Acoustic Neuroma Quality of Life Scale for NF2 trials targeting vestibular schwannomas. To date, there are no disease-specific tools assessing multidimensional domains of QoL for schwannomatosis.

Conclusions

The REiNS Collaboration currently recommends these generic and disease-specific PRO measures to assess multidimensional domains of QoL for NF clinical trials. Additional research is needed to further evaluate the use of these measures in both medical and psychosocial trials.

Neurofibromatosis (NF) 1, NF2, and schwannomatosis are a group of neurogenetic disorders that exhibits the predisposition to develop nerve sheath tumors, but each displays its own distinct characteristics. NF1 is associated with plexiform neurofibromas, cutaneous manifestations, gliomas, bone abnormalities, pain, and learning disabilities.1 NF2 is characterized by bilateral vestibular schwannomas and other benign tumors of the nervous system, as well as complications such as hearing loss or deafness, tinnitus, balance problems, facial paresis, ophthalmic manifestations, and skin lesions.2 Schwannomatosis is characterized by peripheral schwannomas and associated chronic disabling pain.2 These histologically benign tumors and other complications can cause significant morbidity and negatively affect quality of life (QoL) regardless of age and type of NF.3,4

Clinical trials are underway to evaluate the efficacy of medical therapies to treat the tumors and other clinical manifestations associated with NF,5,6 as well as psychosocial interventions to help patients cope with NF-related symptoms and to improve QoL.7,8 For individuals with chronic and progressive diseases like NF, it is critically important to assess the effects of the treatment on the patients' symptoms, functioning, and well-being in clinical trials.9 While objective trial endpoints (e.g., laboratory tests or imaging analyses) document changes in physiologic disease severity, assessing the patients' perspective about aspects of their functioning and QoL using patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures provides a unique indicator of the beneficial or detrimental effects of treatment beyond biomedical outcomes.9,10

The Federal Drug Administration, European Medicines Agency, and several professional oncology societies support the use of PRO measures in clinical trials and the development of standardized approaches and consensus-based guidance.9,10 Harmonization of clinical outcome measures facilitates implementing multicenter studies, comparing findings across similar treatment trials, and pooling data when appropriate,11 which are particularly important in rare diseases like NF. The Response Evaluation in Neurofibromatosis and Schwannomatosis (REiNS) International Collaboration is an interdisciplinary group tasked with reaching a consensus on appropriate endpoints for NF clinical trials. More specifically, the REiNS PRO group is working to provide guidance on the most appropriate PRO measures for medical and psychosocial NF trials. The PRO group previously developed a systematic method for evaluating available PRO measures for use in NF clinical trials, which was used to formulate recommendations for assessing pain and physical function.12,13 In the current study, this method was applied to generic and disease-specific PRO measures assessing multidimensional domains of QoL.

QoL is a multidimensional construct comprising a range of domains such as physical, social, emotional, and role functioning.14 PRO measures assessing aspects of QoL vary widely in their content and may consist of items related to the perception of one's own functioning, disability, health, and satisfaction with life.15 Two types of PRO measures evaluate multidimensional domains of QoL: generic and disease specific. Generic measures assess a broad range of concepts in the general population, including individuals with or without chronic illness.16 Generic scales allow comparison of results between a specific disease and the general public and across different diseases such as when individuals with NF1 and NF2 participate in a single psychosocial trial. However, generic measures often do not capture unique issues specific to a particular disease such as skin conditions, which are important in NF1, or hearing and balance, which are relevant for NF2.

Disease-specific measures, in contrast, are developed for a particular patient population16 and assess the symptoms and physical functions typically affected by a specific medical condition. Thus, disease-specific measures are often more sensitive to capturing change after interventions aimed to improve specific signs and symptoms.16 However, disease-specific measures do not allow comparing or combining various diseases (e.g., NF1, NF2) within a psychosocial study.

With many multidimensional PRO measures available, NF researchers have used a number of different existing scales3,4 that evaluate varied domains and item content, assess various age ranges, and may not be developed specifically for NF. However, there is a current need to assess clinical outcomes in NF trials and to use consistent measures when feasible to facilitate comparisons across studies. Thus, the primary aim of this study was to identify existing PRO measures assessing multidimensional domains of QoL that are most appropriate to evaluate changes in clinical outcomes in NF trials. This article presents the results of the REiNS PRO working group's efforts examining generic and disease-specific measures using published literature and provides the current REiNS consensus recommendations in these domains to serve as a guide for NF researchers.

Methods

The REiNS PRO group consists of an interdisciplinary group of clinical researchers with expertise in NF and several patient representatives, including adults with NF and caregivers of children with NF. We used a systematic process to review and rate existing PRO measures, as previously described in detail.12,13 To summarize, we first discussed and selected the most promising multidimensional generic and disease-specific PRO measures published before May 1, 2019, on the basis of literature reviews. Next, we initially reviewed and rated these measures according to 6 established criteria using our Patient Reported Outcomes–Rating and Acceptance Tool for Endpoints system.12 These criteria include (1) patient characteristics (age range, normative data), (2) use in published studies (validation, descriptive, clinical trials, and NF clinical trials), (3) domain and item content (content of domains and items, wording, format), (4) scores available (raw, standardized, item, domain), (5) psychometric data (reliability, validity, sensitivity to change, factor analysis), and (6) feasibility (cost, languages, length, ease of administration and scoring, recall period). Each criterion was rated on a scale of 0 (no to poor data or information) to 3 (solid published data and information supporting use in NF trials), which were averaged to produce an overall group rating. To make our final ratings and selections, we predominantly considered 4 of the criteria: patient characteristics, domains and item content, psychometric data, and feasibility for NF clinical trials. When ≥2 of the PRO tools in a particular domain were rated the highest with close total scores, we conducted a detailed side-by-side comparison to rereview, rate, and discuss the strengths and limitations of each measure.

We focused our discussions, ratings, and recommendations specific to identifying PRO measures to evaluate change in clinical trials for individuals with NF rather than for descriptive studies or for general chronic illness. Thus, under these 4 main criteria, we took several issues into account when identifying and rating measures. NF trials involving young children or even older individuals with learning disabilities require self-report PRO measures that are easy to understand in addition to parallel parent-report forms to obtain observer-reported outcomes. For trials enrolling children through adults, measures are needed that assess a wide age range with similar domains and items. Of utmost importance, we carefully considered each measure for item content most relevant to individuals with NF and that may demonstrate change with treatment in clinical trials. To be used as trial endpoints, good psychometric properties are imperative. Finally, multicenter and international NF trials are ongoing that necessitate PRO measures in multiple languages.

Results

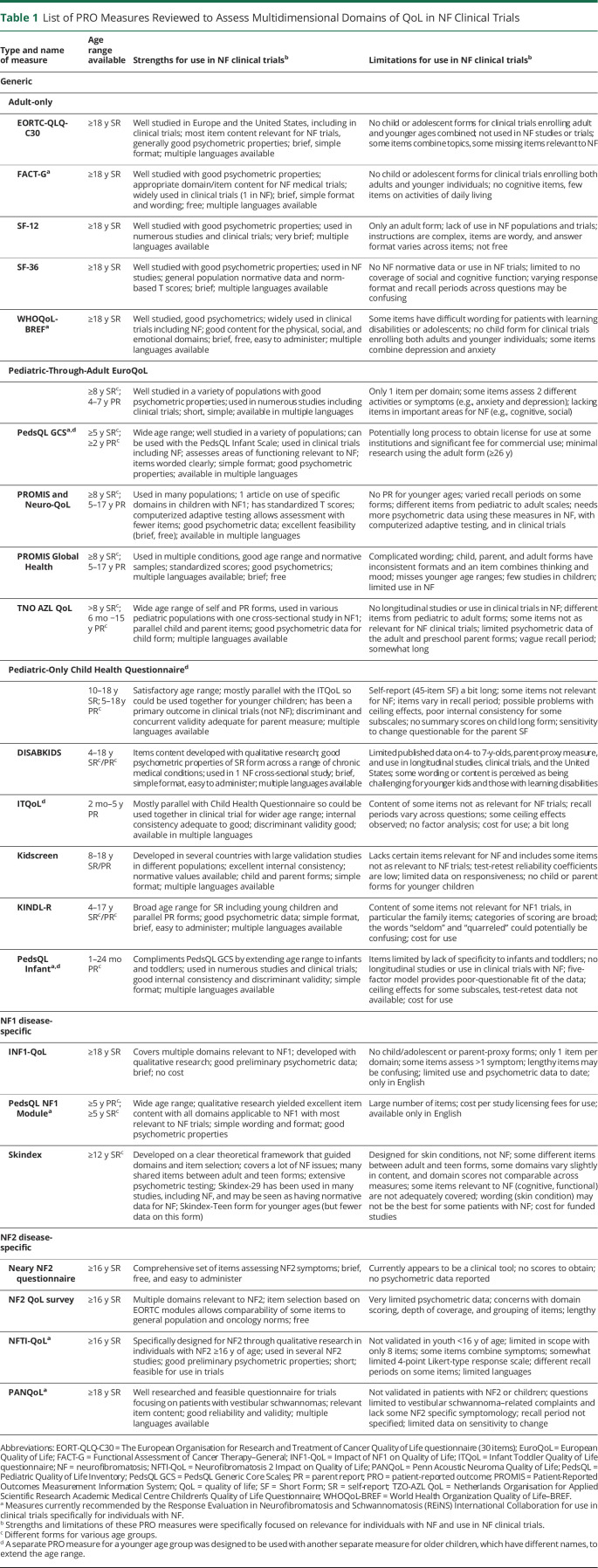

Table 1 lists all 23 PRO measures evaluated by our group and their strengths and limitations specifically for use in NF clinical trials according to our extensive reviews and Patient Reported Outcomes–Rating and Acceptance Tool for Endpoints criteria. Below we provide information about the multidimensional generic and disease-specific PRO measures rated the highest and the type of trials and study populations for which they were considered. In addition, tables 2 through 6 present detailed information about each of the PRO measures described below and their final group ratings.

Table 1.

List of PRO Measures Reviewed to Assess Multidimensional Domains of QoL in NF Clinical Trials

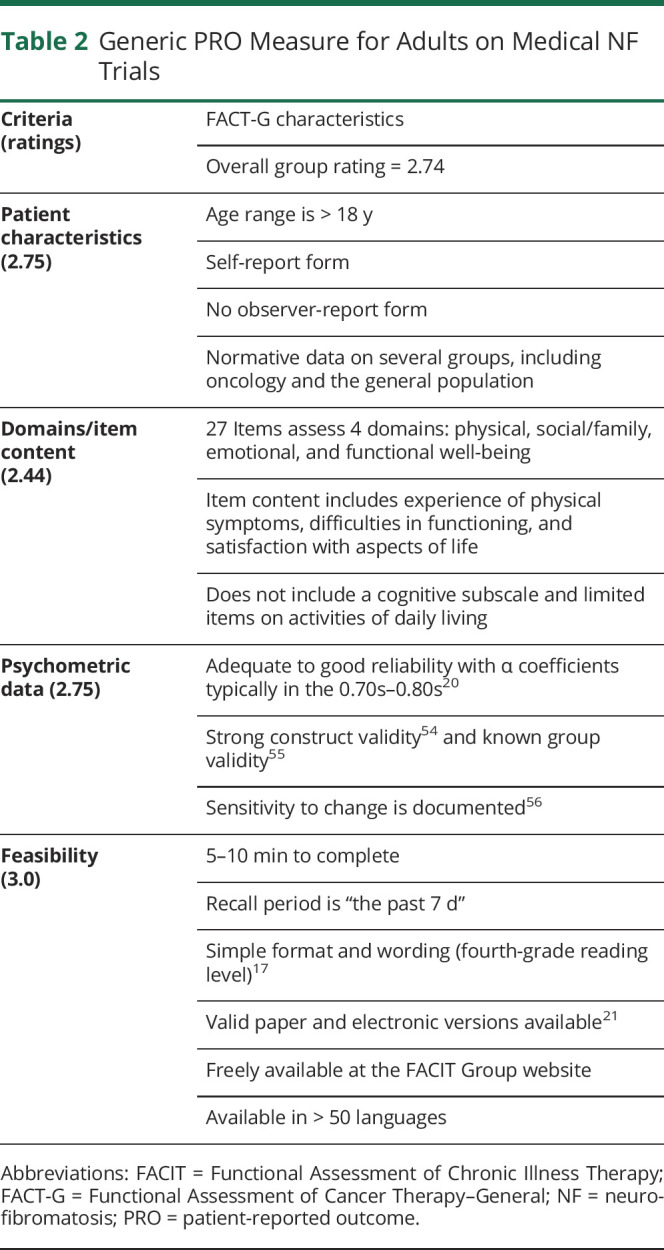

Table 2.

Generic PRO Measure for Adults on Medical NF Trials

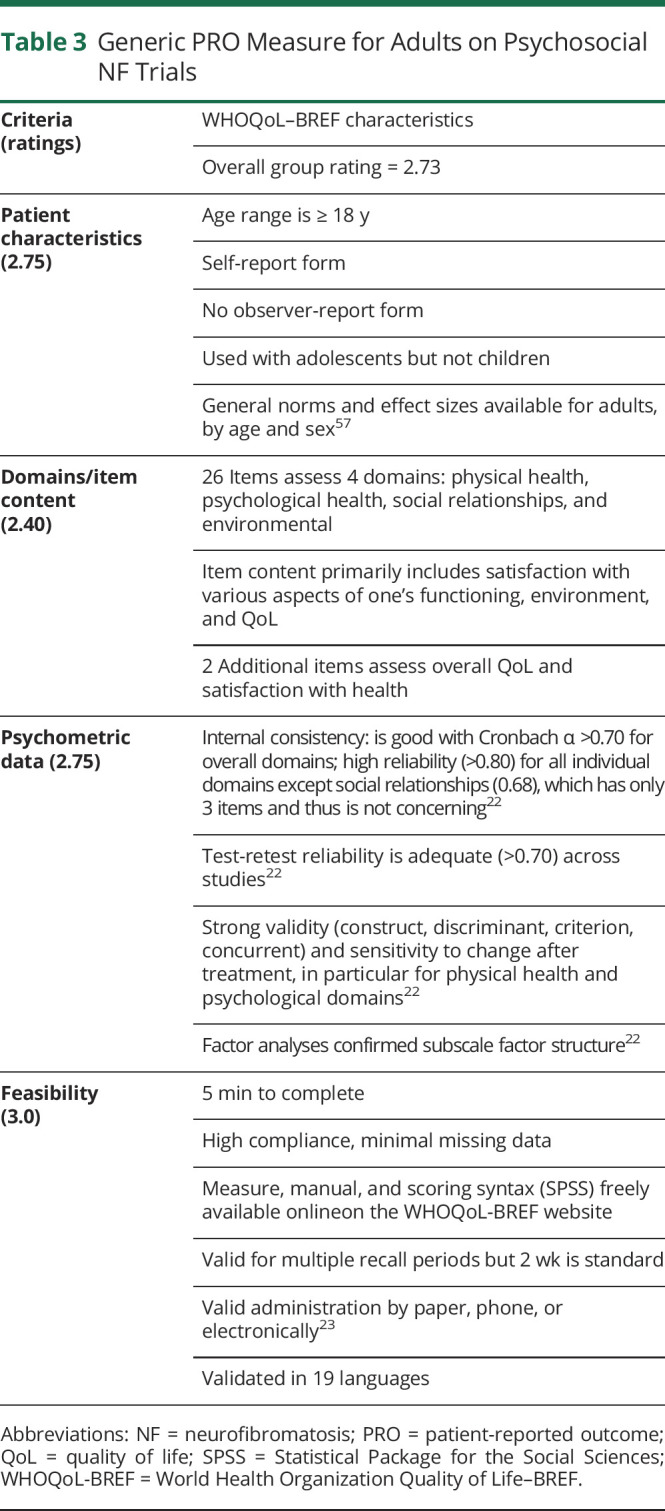

Table 3.

Generic PRO Measure for Adults on Psychosocial NF Trials

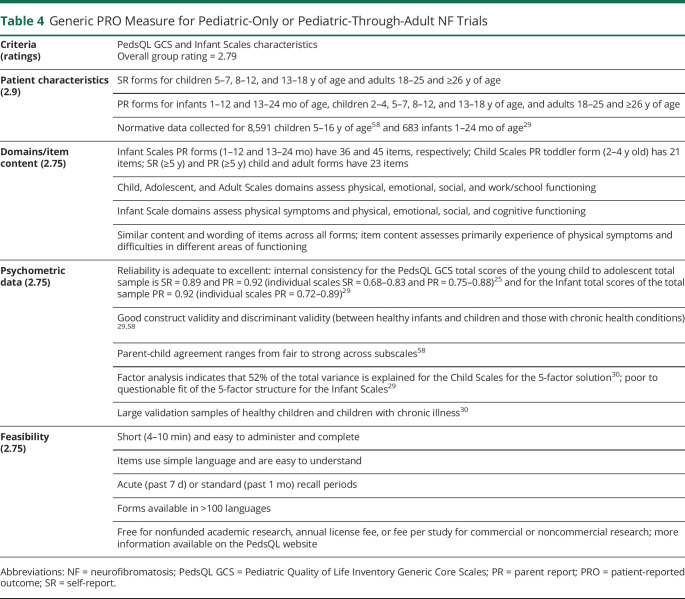

Table 4.

Generic PRO Measure for Pediatric-Only or Pediatric-Through-Adult NF Trials

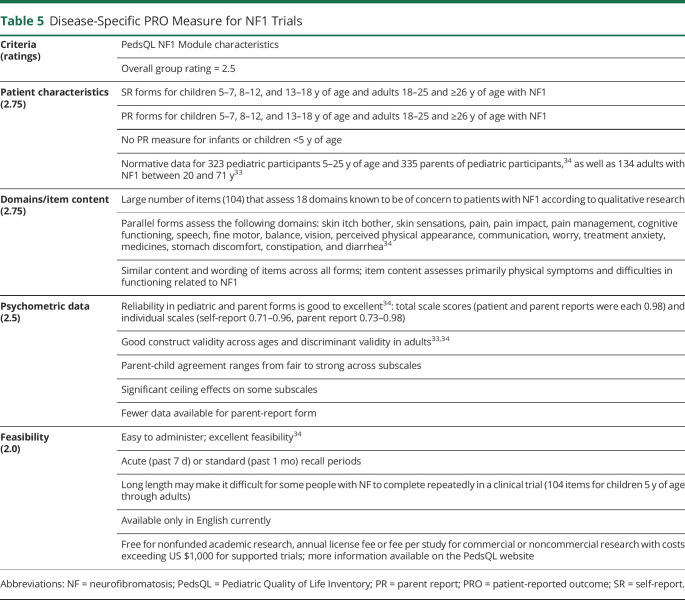

Table 5.

Disease-Specific PRO Measure for NF1 Trials

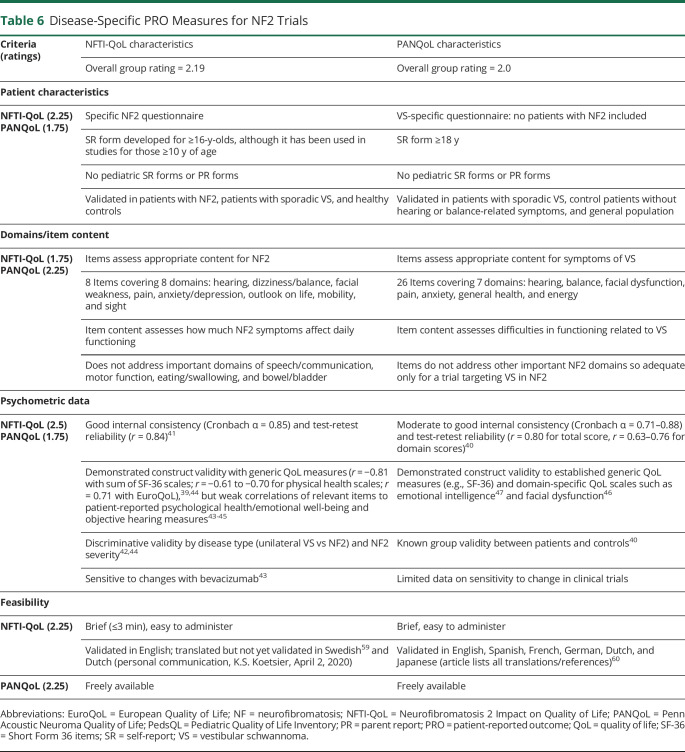

Table 6.

Disease-Specific PRO Measures for NF2 Trials

Generic Measures

Due to the wide age range of individuals to be enrolled and the different domains to be assessed when evaluating medical and psychosocial treatments for NF, we present the 3 highest-rated generic measures our group evaluated for adult-only, pediatric-only, and adult-through-pediatric trials.

Adult-Only Clinical Trials

Our group identified 5 adult-only and 5 pediatric-through-adult generic measures assessing domains of QoL as potential tools suitable for use in adult NF clinical trials. After our initial reviews, the 2 highest-rated measures for adult trials were the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G)17 and World Health Organization Quality of Life–BREF (WHOQoL-BREF)14 scales. Side-by-side comparisons of these 2 measures resulted in very similar ratings that informed our recommendations.

Adult Medical Trials

The FACT-G was the highest-rated generic PRO measure assessing multidimensional domains of QoL for use in medical clinical trials for adults with NF (table 2). This measure assesses 4 domains (physical, emotional, social/family, and functional well-being) and consists of 27 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale17 that were deemed relevant to evaluating meaningful changes in NF treatment trials. Scores are computed for the 4 subscales and summed to produce a total score. The FACT-G has been used extensively in medical trials,18 including 1 trial in NF1.19 Moreover, it has strong reliability20 and is valid when administered by paper, interviewer, or electronically.21 This scale takes 5 to 10 minutes to complete, is easy to read, has a simple format, and is freely available in >70 languages. Limitations our group identified for using this measure in NF trials are the lack of items assessing cognitive function and the absence of normative and psychometric data for patients with NF.

Adult Psychosocial Trials

The WHOQoL-BREF14 was the highest-rated generic PRO measure to evaluate clinical changes in psychosocial trials for adults with NF (table 3). It was developed from the parent measure WHOQoL-100 through field testing in 25 countries. The WHOQoL-BREF comprises 4 domains of QoL: physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment. In addition, 2 items measure overall QoL and satisfaction with general health. All items are answered on a 5-point Likert scale,22 and within each domain, items are summed and transformed into domain scores. This scale can be administered in ≈5 minutes via paper and is validated for administration by phone or electronic devices.23 It has been translated into 19 languages and used in hundreds of psychosocial clinical trials, including NF.7,8,24 Limitations include no normative data as yet for patients with NF. In addition, some of the wording may be difficult for individuals with NF1 who have learning disabilities, and the Environment domain may not be relevant or sensitive to change in NF trials, although it does not have to be administered.

Pediatric-Only or Pediatric-Through-Adult Clinical Trials

Our group identified 6 pediatric and 5 pediatric-through-adult generic PRO measures that assess multidimensional domains of QoL that we deemed appropriate for further review for NF trials. The top 3 rated measures for pediatric-only trials included the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) version 4.0 Generic Core Scales (GCS),25 the KINDL-R questionnaire,26 and the DISABKIDS questionnaire.27 The 2 highest-rated generic measures for trials enrolling children through adults were the PedsQL GCS25 and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System/Neuro-QoL measures.28 In our side-by-side comparisons, the PedsQL GCS received the highest overall group rating.

Pediatric-Only and PEDIATRIC-Through-Adult Medical and Psychosocial Trials

The PedsQL GCS was the generic measure that we rated the highest for both medical and psychosocial trials targeting only children and adolescents, as well as trials including children through adults (table 4). The PedsQL GCS has self-report forms for children ages 5 to 18 years (preschool, child, teen), young adults (18–25 years), and adults (>26 years) and parallel parent-report forms for ages ≥2 years. In addition, the PedsQL has parent-report forms for infants ages 1 through 24 months, thus allowing similar measures to be used across all ages.29-31 Although the PedsQL has a self-report version for adults (>26 years), there currently is scant research using this form, so we decided to recommend separate adult-only measures for trials that do not include children or adolescents at this time.

The PedsQL Infant Scales assess physical symptoms, physical functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, and cognitive functioning,29 while the PedsQL GCS child, adolescent, young adult, and adult forms assess physical functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, and work/school functioning.30 Items are rated on 5-point Likert scales that are transformed to a 0 to 100 scale and yield domain and total scores. The PedsQL GCS has good psychometric properties in a variety of patient populations,30 is brief, and is available in >100 languages. The PedsQL GCS was used to evaluate generic QoL in clinical trials with individuals with NF1,5,19 and additional NF trials using the PedsQL GCS are underway. The main limitations of these PedsQL measures include the poor to questionable fit of the 5-factor structure of the Infant Scales29 and the lack of research on the adult form.

Disease-Specific Measures

NF1 Disease-Specific QoL

Our group identified and reviewed 3 published disease-specific measures used for the evaluation of patients with NF1: Impact of NF1 on Quality of Life questionnaire,32 Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Module (PedsQL NF1),33,34 and Skindex, including the Skindex-2935 and Skindex-Teen.36

In our review process, the PedsQL NF1 Module33,37 was rated the highest to assess multidimensional domains of disease-specific QoL in trials for individuals with NF1 (table 5). This measure was developed through a collaboration between experts in the field of NF and the author of the PedsQL using a process that was similar to that of other PedsQL modules.33 The 104-item scale assesses 18 domains determined to be affected in NF1 through rigorous qualitative research.37 It yields domain and total scores and has acceptable to excellent psychometric properties.33,34 Furthermore, the adolescent and adult modules were used in 2 recent clinical trials that documented changes in several domains scores with treatment to reduce plexiform neurofibromas.6,38 Limitations of this measure include the lack of a parent-report form for children <5 years of age, long length (particularly for repeated administration in trials), availability in only English, and lack of clinical trial data in children to date.

NF2 Disease-Specific QoL

Our group identified 4 measures of NF2-related QoL to be reviewed and rated. Of these, the Neurofibromatosis 2 Impact on Quality of Life (NFTI-QoL)39 and Penn Acoustic Neuroma Quality of Life (PANQoL)40 scales were the highest-rated measures with close side-by-side ratings (table 6).

The NFTI-QoL is freely available, brief, and easy to administer. It consists of only 8 items but addresses the complications relevant to NF2 based on qualitative research.39 The items are rated on 4-point Likert scales, and a total score (ranging from 0–24) is calculated as the sum of all items. Clinical studies generally report good reliability and validity.41-44 However, some studies have demonstrated limited construct validity for psychological functioning and emotional well-being.44,45 Our group noted some limitations of this measure. The wording of response options and recall periods are not consistent across all items. The measure does not address potentially important facets of NF2-related QoL, including speech/communication, motor function, eating/swallowing, bowel/bladder issues, and potential meningioma symptoms such as fatigue and cognitive difficulties. In addition, it has only 1 question per domain, with some items addressing multiple related domains, leading to concerns regarding sensitivity to change and interpretability of changes over time. However, the NFTI-QoL reflected improvement in response to treatment with bevacizumab during routine clinical care,43 and it is being used in current NF2 clinical trials, so additional longitudinal data will be forthcoming.

The PANQoL is a 26-item scale that assesses 7 QoL domains affected by vestibular schwannomas40 and includes more items on emotional well-being than the NFTI-QoL. Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale; scores are then summed and transformed to a 0 to 100 scale. An overall score and 7 domain scores are available. The measure has moderate to good internal consistency and test-retest reliability.40 Convergent validity has been demonstrated across multiple domains (fatigue, facial paresis, and emotional intelligence).46-48 The PANQoL was recommended to be used only as an exploratory outcome measure because patients with NF2 were excluded during the development of this scale and in all currently published studies. Therefore, it does not address all aspects of NF2-related QoL and does not account for all potential etiologies of NF2-related symptoms (e.g., questions address difficulties in walking due to balance issues but not neuropathies or muscle atrophy).

Schwannomatosis Disease-Specific QoL

Our group was not able to identify any disease-specific measures developed for individuals with schwannomatosis. Prior systematic reviews have documented a relative paucity of published studies assessing QoL in patients with schwannomatosis, highlighting the need for additional investigation in this area.3,49

Discussion

PRO measures provide unique and critical data to evaluate treatment effects in medical and psychosocial trials by assessing patients' subjective experiences. In this study, the REiNS PRO group, including the patient representatives, used their established methodology12 to review, rate, and recommend existing generic and disease-specific PRO measures to assess multidimensional domains of QoL in individuals with NF1, NF2, and schwannomatosis who are participating in clinical trials. Our ratings and recommendations target the specific, unique needs of PRO assessments for clinical trials involving individuals with NF and may not reflect the appropriateness of these measures for other types of NF research or patient populations.

For the domain of generic PRO measures, we currently recommend 3 measures due to the wide age range of individuals who may participate in NF clinical trials and the different domains and items that are important to assess in medical vs psychosocial trials. For adult-only medical trials, we recommend the FACT-G because it covers a range of domains and items important for evaluating the impact of treatments on symptoms, functioning, and aspects of QoL for adults with NF, is easy to complete, and is available in multiple languages. Additional strengths include its excellent psychometric properties in the adult cancer population and frequent use in clinical trials and regulatory submissions,18 including 1 NF1 trial evaluating a drug treatment for plexiform neurofibromas.19 However, further research is needed to examine the use of the FACT-G in adult NF clinical trials and to obtain additional measurement data from the various types of NF. For medical trials seeking drug approval, the Food and Drug Administration prefers PRO assessments of proximal concepts such as symptoms rather than more distal concepts like generic QoL, while the European Medicines Agency is more accepting of QoL data.18,50 However, because the domains in multidimensional PRO measures yield scores from the same normative sample,9 separate analyses of the individual domains (e.g., functional well-being) can be performed to provide a focused evaluation of a particular area when needed. Furthermore, specific symptoms or complications may influence functioning and QoL,51 thus supporting the use of generic measures in clinical trials.

We recommend the WHOQoL-BREF for adult-only psychosocial trials for several reasons. This scale assesses both overall QoL and domain-specific satisfaction with one's physical, social, and psychological health, which are highly modifiable with psychosocial interventions. It is available in many languages and has been used widely in research, including mind-body interventions among adults with NF1, NF2, and schwannomatosis8,24 and adolescents with NF1 and NF2.7 Future studies should examine the psychometric properties of the WHOQoL-BREF in individuals with NF. Although our group attempted to identify 1 adult measure for both medical and psychosocial trials for all 3 types of NF to facilitate comparability across studies, the items and domains of each of the measures did not seem suitable for both types of trials. Because the 2 measures we recommend are brief, it would be useful to administer both measures in future trials when possible to determine whether only 1 of them is sufficient for both kinds of trials.

For medical and psychosocial NF trials that enroll only children and adolescents or a wider age range from children/adolescents through adults, we recommend the PedsQL, consisting of the GCS and Infant Scales. The main strengths of these measures include that they consist of parallel and simply worded items and assess similar domains of functioning across child to adult age groups with both self-report and parent-report versions. The PedsQL GCS has good psychometric properties and has been used in numerous studies and clinical trials, including those with NF1.5,19 This generic measure also may be administered in combination with the PedsQL NF1 disease-specific module to obtain a more comprehensive PRO assessment. However, 1 gap to be addressed is that the parent-report Infant Scales have not been used in an NF trial to date, but they currently are being considered for a pediatric treatment trial being planned for very young children with NF1. Additional research is needed on (1) the general psychometric properties of the PedsQL Adult form, because the lack of data prohibited us from recommending it for adult-only trials, and (2) the use of the PedsQL GCS and Infant Scales in the NF population. Another limitation is that the new licensing agreements for the PedsQL forms are very complicated for PRO measures, which currently make it difficult and time-consuming for the NIH and other federal government research facilities to obtain the appropriate permissions for its use in studies.

For the NF1 disease-specific QoL measure, we recommend the PedsQL NF1 Module. Strengths include rigorous qualitative research that was conducted to develop the item content so that it assesses the many domains affecting the QoL of individuals with NF137 and the ability to evaluate children through adults with similar domains and items. Future research on this new scale is needed to develop a related parent-report measure for children <5 years of age because NF medical trials are enrolling younger children. In addition, it will be important to examine further the psychometric properties of the parent-report form, to analyze the factor structure, and to determine the minimally clinically important difference (MCID). Another critical step is to translate the forms into languages other than English. Finally, the PedsQL NF1 Module has been used in 2 adult NF treatment trials,6,38 but it has not been used in a pediatric trial to date.

We are recommending 2 measures to assess disease-specific QoL in individuals with NF2: the NFTI-QoL for all NF2 clinical trials and the PANQoL as an exploratory measure for NF2 trials targeting vestibular schwannomas. The NFTI-QoL was developed specifically to assess the domains affected in patients with NF2; it is brief to facilitate repeated evaluations in clinical trials; and it has good reliability and validity.39,41,44 Future research should address calculating the MCID, examining its use and sensitivity to change in NF2 clinical trials, and developing measures in additional languages. There also is a need for validated NF2 disease-specific pediatric and parent-proxy forms given recent NF2 trials with lower age limits. The PANQoL was recommended for clinical trials enrolling individuals with NF2 and vestibular schwannomas because it is a well-studied tool with good psychometric data, comprehensively assesses domains important to these patients, and is available in several languages. However, future research is needed to validate the PANQoL in patients with NF2. For both of these NF2 disease-specific tools, there is a lack of items covering social issues (and emotional concerns in the NFTI-QoL), communication/speech, eating/swallowing, cognitive functioning, and bowel/bladder issues. Given recent treatment advances for NF2-related vestibular schwannomas and reduction of related complications, symptoms associated with other manifestations of NF2 (e.g., meningiomas, ependymomas, peripheral neuropathy) may become more apparent; thus, current NF2-specific measures may not be adequate to fully capture the impact of these manifestations on functioning and QoL. Adding a generic QoL or a specific symptom measure in a clinical trial may be needed to thoroughly assess these other domains important to patients with NF2.

There are no published multidimensional PRO measures developed for schwannomatosis. Given that chronic pain is the most common and concerning symptom of schwannomatosis,52 we recommend that researchers seeking to assess aspects of QoL in schwannomatosis clinical trials use previously recommended measures for pain intensity and pain interference13 in combination with 1 of the age-appropriate generic measures described here.

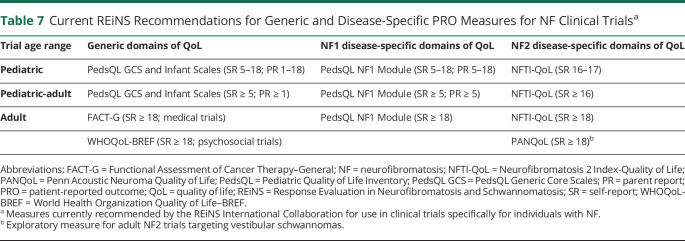

Table 7 summarizes our current recommendations for the most appropriate PRO measures to assess the multidimensional aspects of QoL in NF trials from the published literature, but researchers still must determine which measures to use in specific trials. During the selection of the most appropriate PRO measures to use, it is important to consider carefully the objectives of the trial, age range of patients, domains that may be affected by NF, wording and content of the items, and areas that might be improved by therapy or possible toxicities that may be related to the treatment. The generic measures can be used for clinical trials enrolling any of the 3 types of NF, unlike the disease-specific tools. In some cases, unidimensional PRO tools that assess disease-specific symptoms such as pain intensity or pain interference13 in NF1 or schwannomatosis trials and specific functions such as communication in NF2 trials may need to be administered in addition to a generic measure. In other cases, 1 multidimensional NF1 or NF2 disease-specific tool may be sufficient for measuring the particular domains of interest in a medical trial. For a more comprehensive assessment, a generic and NF disease-specific measure (e.g., PedsQL GSC and NF1 Module) can be administered together. Given the cognitive difficulties in individuals with NF1,53 we recommend administering self-report measures in children starting at 8 years of age. Finally, it is important to acknowledge that some patients enrolling in clinical trials may need assistance with completing PRO self-report measures due to physical or cognitive impairments. Helping patients who have difficulties with reading items, writing down responses, or pushing the desired button on an electronic tablet is appropriate for the administration of PRO measures so that most of the participants in a trial can provide these important clinical endpoint data. REiNS PRO group members and other experts in PRO assessment can be consulted to assist with these choices when needed.

Table 7.

Current REiNS Recommendations for Generic and Disease-Specific PRO Measures for NF Clinical Trialsa

There are limitations to our current recommendations. First, although our systematic method evaluates existing PRO measures on several important criteria12 and involves NF experts and patient representatives to carefully examine and compare the item content to ensure a fit for the NF population, we did not use the World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health to standardize terminology and conceptual frameworks as is being recommended by some PRO researchers.15 We also did not use a mapping methodology to compare the items and domains between measures. Updates to these recommendations in the future should consider using a specific methodology such as the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health to define the domains and items assessed to be consistent with these new methods and to evaluate and compare the PRO measures in a more precise manner. Second, the generic measures have limited psychometric and normative data in patients with the different types of NF. We are recommending these PRO measures partially on the basis of their strong psychometric properties in other populations and the item content deemed important for NF clinical trials by our group's expertise and patient input, despite not necessarily being a perfect fit for NF. These generic measures have yet to undergo the rigorous testing needed to determine their reliability, validity, sensitivity to change, and MCID specifically in NF populations, which is critical for PRO measures being used in clinical trials seeking drug approval and for product labeling. However, researchers need PRO measures to assess clinical outcomes in NF trials at this time. In response to this critical need, we made these recommendations for existing tools on the basis of the current literature. As the field gains experience using these tools in patients with NF across the lifespan, collects longitudinal data on trials, and develops new measures, some recommendations may need to be updated. For the NF1 and NF2 disease-specific tools, preliminary psychometric findings are promising, but more work is necessary to further examine the use of these new PRO measures for assessing meaningful change in trial outcomes. Third, most measures do not evaluate young children, although NF clinical trials already are assessing children as young as 3 years of age and new trials are being planned for infants. Thus, parent-report measures or other functional methods of assessment for the youngest children need to be explored. Finally, these recommendations are made to serve as a current guide for the researchers to help promote harmonization in the selection of PRO tools and to suggest areas for further outcomes research in the NF community. However, researchers should consider using other existing PRO measures or developing new tools if needed to match the specific objectives of their clinical trials.

Our REiNS PRO group continues to review existing PRO measures in various domains to provide recommendations for NF clinical trials. Future domains our group may address include disfigurement, fatigue, sleep, tinnitus, skeletal issues, and specific social-emotional domains such as anxiety and depression. In addition, we plan to revisit previous recommendations and to provide updates based on any new data reported in subsequent publications. Thus, our group encourages the NF scientific community to use the recommended PRO measures in studies to collect additional data on their psychometric properties and to further evaluate their appropriateness for both medical and psychosocial trials in NF1, NF2, and schwannomatosis. Researchers also need to continue to develop new measures specifically designed for NF using rigorous methodologies, including qualitative research involving patients, in an effort to increase the pool of reliable and valid PRO measures critically needed as endpoints for various NF clinical trials.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge and thank additional members of the REiNS PRO working group who participated in phone calls and discussions to review and rate the PRO measures assessing generic and disease-specific QoL discussed in this article: Dale Berg, BA, Amanda Bergner, MS, Ann Blanton, PhD, CCC-SLP, Alexandra Cellucci, LPN, Kathy L. Gardner, MD, Andrés J. Lessing, MBA, Melissa Reider-Demer, NP, Tena Rosser, MD, and Karin Walsh, PsyD. The authors acknowledge the support of the Children's Tumor Foundation for the REiNS International Collaboration.

Glossary

- FACT-G

Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General

- MCID

minimally clinically important difference

- NF

neurofibromatosis

- NFTI-QoL

Neurofibromatosis 2 Impact on Quality of Life

- PANQoL

Penn Acoustic Neuroma Quality of Life

- PedsQL

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory

- PedsQL GCS

PedsQL Generic Core Scales

- PedsQL NF1

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Module

- PRO

patient-reported outcome

- QoL

quality of life

- REiNS

Response Evaluation in Neurofibromatosis and Schwannomatosis

- WHOQoL-BREF

World Health Organization Quality of Life–BREF

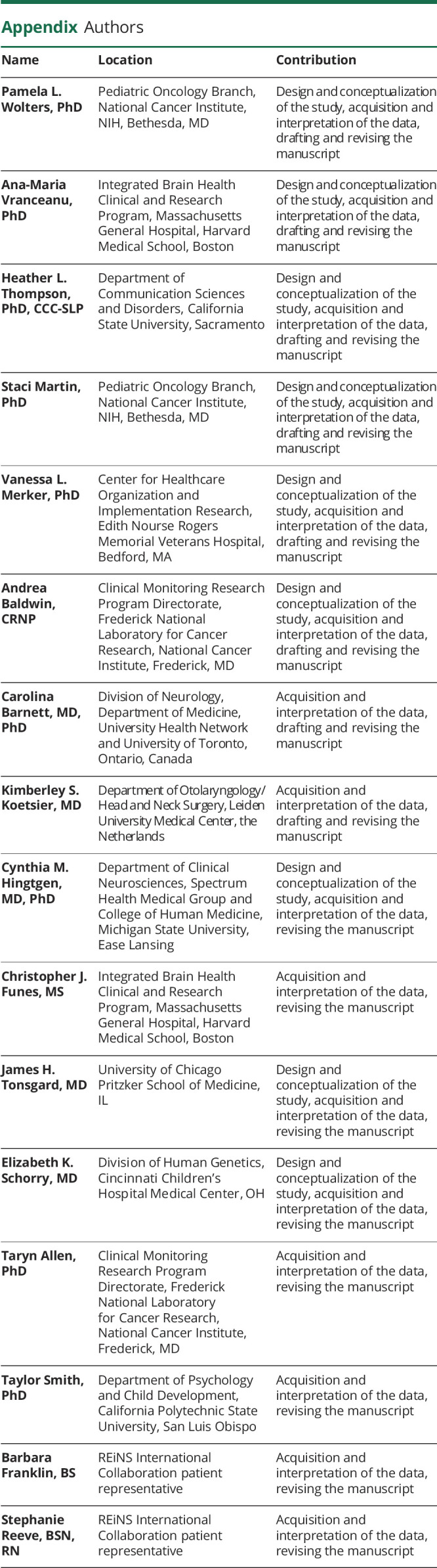

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute. Writing of this manuscript was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Fellowship Program in Health Services Research, the Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research, and the Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government. Writing of this article also was supported by the Department of Defense grants W81XWH-19-1-0184 and W81XWH-17-1-0121.

Disclosures

P. Wolters receives funding from the Neurofibromatosis Therapeutics Acceleration Program. A.M. Vranceanu received funding from the Department of Defense (W81XWH-19-1-0184 and W81XWH-17-1-0121), NF Midwest, NF Northeast, and NF Texas. H. Thompson reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. S. Martin receives funding from the Neurofibromatosis Therapeutics Acceleration Program. V. Merker reports consulting income from the Neurofibromatosis Network. A. Baldwin, C. Barnett, K. Koetsier, C. Hingtgen, and C. Funes, report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. J. Tonsgard receives funding from the Department of Defense Army Research Command as part of the NF Consortium and from Midwest NF, Inc. E. Schorry receives funding from the Department of Defense as a site principal investigator for the NF Consortium and as a coinvestigator for a clinical trial of vitamin D for adults with NF1. T. Allen, T. Smith, B. Franklin, and S. Reeve report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Lu-Emerson C, Plotkin SR. The neurofibromatosis, part 1: NF1. Rev Neurol Dis. 2009;6(2):E47-E53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu-Emerson C, Plotkin SR. The neurofibromatosis, part 2: NF2 and schwannomatosis. Rev Neurol Dis. 2009;6(2):E81-E86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vranceanu AM, Merker VL, Park E, Plotkin SR. Quality of life among adult patients with neurofibromatosis 1, neurofibromatosis 2 and schwannomatosis: a systematic review of the literature. J Neurooncol. 2013;114(3):257-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vranceanu AM, Merker VL, Park ER, Plotkin SR. Quality of life among children and adolescents with neurofibromatosis 1: a systematic review of the literature. J Neurooncol. 2015;122(2):219-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gross AM, Wolters PL, Dombi E, et al. Selumetinib in children with inoperable plexiform neurofibromas. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(13):1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiss BD, Wolters PL, Plotkin SR, et al. NF106: a neurofibromatosis clinical trials consortium phase II trial of the mek inhibitor mirdametinib (PD-0325901) in adolescents and adults with NF1-related plexiform neurofibromas. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(7):797-806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lester E, DiStefano S, Mace R, Macklin E, Plotkin S, Vranceanu AM. Virtual mind-body treatment for geographically diverse youth with neurofibromatosis: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2019;62(2):72-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vranceanu AM, Riklin E, Merker VL, Macklin EA, Park ER, Plotkin SR. Mind-body therapy via videoconferencing in patients with neurofibromatosis: an RCT. Neurology. 2016;87(8):806-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Acquadro C, Berzon R, Dubois D, et al. Incorporating the patient's perspective into drug development and communication: an ad hoc task force report of the Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Harmonization Group meeting at the Food and Drug Administration. Value Health. 2003;6:522-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mercieca-Bebber R, King MT, Calvert MJ, Stockler MR, Friedlander M. The importance of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials and strategies for future optimization. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2018;9:353-367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113:9-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolters PL, Martin S, Merker VL, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in neurofibromatosis and schwannomatosis clinical trials. Neurology. 2013;81(2):S6–S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolters PL, Martin S, Merker VL, et al. Patient-reported outcomes of pain and physical functioning in neurofibromatosis clinical trials. Neurology. 2016;87:S4–S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQoL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(12):1569-1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fayed N, de Camargo OK, Kerr E, et al. Generic patient-reported outcomes in child health research: a review of conceptual content using World Health Organization definitions. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54(2):1085-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patrick DL, Deyo RA. Generic and disease-specific measures in assessing health status and quality of life. Med Care. 1989;27(3):S217-S232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webster K, Cella D, Yost K. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gnanasakthy A, Barrett A, Evans E, D'Alessio D, Romano CD. A review of patient-reported outcomes labeling for oncology drugs approved by the FDA and the EMA (2012-2016). Value Health. 2019;22(2):203-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiss B, Widemann BC, Wolters P, et al. Sirolimus for non-progressive NF1-associated plexiform neurofibromas: an NF Clinical Trials Consortium phase II study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(6):982-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Victorson D, Barocas J, Song J, Cella D. Reliability across studies from the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) and its subscales: a reliability generalization. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(9):1137-1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luckett T, King MT, Butow PN, et al. Choosing between the EORTC QLQ-C30 and FACT-G for measuring health-related quality of life in cancer clinical research: issues, evidence and recommendations. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(10):2179-2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O'Connell KA, Group W. The World Health Organization's WHOQoL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial: a report from the WHOQoL group. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(2):299-310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shawver Z, Griffith JD, Adams LT, Evans JV, Benchoff B, Sargent R. An examination of the WHOQoL-BREF using four popular data collection methods. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;55:446-454. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Funes CJ, Mace RA, Macklin EA, Plotkin SR, Jordan JT, Vranceanu AM. First report of quality of life in adults with neurofibromatosis 2 who are deafened or have significant hearing loss: results of a live-video randomized control trial. J Neurooncol. 2019;143(3):505-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Seid M, Skarr D. The PedsQL 4.0 as a pediatric population health measure: feasibility, reliability, and validity. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3(6):329-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bullinger M, Brutt AL, Erhart M, Ravens-Sieberer U, Group BS. Psychometric properties of the KINDL-R questionnaire: results of the BELLA study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;17(suppl 1):125-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt S, Debensason D, Muhlan H, et al. The DISABKIDS generic quality of life instrument showed cross-cultural validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(6):587-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(7):873-880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Varni JW, Limbers CA, Neighbors K, et al. The PedsQL Infant Scales: feasibility, internal consistency reliability, and validity in healthy and ill infants. Qual Life Res. 2011;20(1):45-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 Generic Core Scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001;39(8):800-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varni JW, Limbers CA. The PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales young adult version: feasibility, reliability and validity in a university student population. J Health Psychol. 2009;14(4):611-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferner RE, Thomas M, Mercer G, et al. Evaluation of quality of life in adults with neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) using the Impact of NF1 on Quality of Life (INF1-QoL) questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nutakki K, Hingtgen CM, Monahan P, Varni JW, Swigonski NL. Development of the adult PedsQL neurofibromatosis type 1 module: initial feasibility, reliability and validity. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nutakki K, Varni JW, Swigonski NL. PedsQL Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Module for children, adolescents and young adults: feasibility, reliability, and validity. J Neurooncol. 2018;137(2):337-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chren MM, Lasek RJ, Quinn LM, Mostow EN, Zyzanski SJ. Skindex, a quality-of-life measure for patients with skin disease: reliability, validity, and responsiveness. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107(5):707-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smidt AC, Lai JS, Cella D, Patel S, Mancini AJ, Chamlin SL. Development and validation of Skindex-Teen, a quality-of-life instrument for adolescents with skin disease. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(8):865-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nutakki K, Varni JW, Steinbrenner S, Draucker CB, Swigonski NL. Development of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Neurofibromatosis Type 1 Module items for children, adolescents and young adults: qualitative methods. J Neurooncol. 2017;132(1):135-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fisher MJ, Shih CS, Rhodes SD, et al. Cabozantinib for neurofibromatosis type 1-related plexiform neurofibromas: a phase 2 trial. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):165-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hornigold RE, Golding JF, Leschziner G, et al. The NFTI-QoL: a disease-specific quality of life questionnaire for neurofibromatosis 2. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2012;73(2):104-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaffer BT, Cohen MS, Bigelow DC, Ruckenstein MJ. Validation of a disease-specific quality-of-life instrument for acoustic neuroma: the Penn Acoustic Neuroma Quality-of-Life Scale. Laryngoscope. 2010;120(8):1646-1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferner RE, Shaw A, Evans DG, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of quality of life in 288 patients with neurofibromatosis 2. J Neurol. 2014;261(5):963-969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Halliday D, Emmanouil B, Pretorius P, et al. Genetic Severity Score predicts clinical phenotype in NF2. J Med Genet. 2017;54(10):657-664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morris KA, Golding JF, Axon PR, et al. Bevacizumab in neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) related vestibular schwannomas: a nationally coordinated approach to delivery and prospective evaluation. Neurooncol Pract. 2016;3(4):281-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shukla A, Hsu FC, Slobogean B, et al. Association between patient-reported outcomes and objective disease indices in people with NF2. Neurol Clin Pract. 2019;9(4):322-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Quarmby LM, Dalton LJ, Woolrich RA, et al. Screening and intervening: psychological distress in neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2). Psychooncology. 2019;28(7):1583-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lodder WL, Adan GH, Chean CS, Lesser TH, Leong SC. Validation of the facial dysfunction domain of the Penn Acoustic Neuroma Quality-of-Life (PANQoL) Scale. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274(6):2437-2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van Leeuwen BM, Borst JM, Putter H, Jansen JC, van der Mey AG, Kaptein AA. Emotional intelligence in association with quality of life in patients recently diagnosed with vestibular schwannoma. Otol Neurotol. 2014;35(9):1650-1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dhayalan D, Lund-Johansen M, Finnkirk M, Tveiten OV. Fatigue in patients with vestibular schwannoma. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2019;161(9):1809-1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanagoo A, Jouybari L, Koohi F, Sayehmiri F. Evaluation of QoL in neurofibromatosis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis study. BMC Neurol. 2019;19:123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guidance for Industry FDA: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Food and Drug Administration; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gutmann DH, Ferner RE, Listernick RH, Korf BR, Wolters PL, Johnson KJ. Neurofibromatosis type 1. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3(2):17004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Merker VL, Esparza S, Smith MJ, Stemmer-Rachamimov A, Plotkin SR. Clinical features of schwannomatosis: a retrospective analysis of 87 patients. Oncologist. 2012;17(2):1317-1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torres Nupan MM, Velez Van Meerbeke A, Lopez Cabra CA, Herrera Gomez PM. Cognitive and behavioral disorders in children with neurofibromatosis type 1. Front Pediatr. 2017;5(10):227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yost KJ, Thompson CA, Eton DT, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - General (FACT-G) is valid for monitoring quality of life in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54(2):290-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Teckle P, Peacock S, McTaggart-Cowan H, et al. The ability of cancer-specific and generic preference-based instruments to discriminate across clinical and self-reported measures of cancer severities. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pavel ME, Singh S, Strosberg JR, et al. Health-related quality of life for everolimus versus placebo in patients with advanced, non-functional, well-differentiated gastrointestinal or lung neuroendocrine tumours (RADIANT-4): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(10):1411-1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hawthorne G, Herrman H, Murphy B. Interpreting the WHOQoL-bref: preliminary population norms and effect sizes. Soc Indicators Res. 2006;77:37-59. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Varni JW, Limbers CA, Burwinkle TM. How young can children reliably and validly self-report their health-related quality of life? An analysis of 8,591 children across age subgroups with the PedsQL 4.0 Generic Core Scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lundin K, Stillesjo F, Nyberg G, Rask-Andersen H. Self-reported benefit, sound perception, and quality-of-life in patients with auditory brainstem implants (ABIs). Acta Otolaryngol. 2016;136(1):62-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nishiyama T, Oishi N, Kojima T, et al. Validation and multidimensional analysis of the Japanese Penn Acoustic Neuroma Quality-of-Life Scale. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(12):2885-2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]