Abstract

This study examined whether early institutional rearing and attachment security influence the quality and quantity of friendships at age 16 in 138 participants, including children abandoned to institutions in Bucharest, Romania, who were randomized to care as usual (n=45, 26 female), or foster care (n=47, 25 female), and a never-institutionalized group (n=46, 18 female). Adolescents in the foster care group with secure attachment to their foster mothers at 42 months were comparable to never-institutionalized adolescents in having more friends and more positive behaviors with their friend during dyadic interactions, compared to the foster care group with insecure attachment and care as usual group. Interventions targeting early child-caregiver attachment relationships may help foster the ability to build positive friendships in adolescence.

Keywords: Friendship, Neglect, Attachment, Adolescence, Social support

Decades of research highlight the importance and function of friendships (Bukowski, Newcomb, & Hartup, 1998; Hartup & Stevens, 1997; Sullivan, 2013). Friendships provide social support and intimacy in adolescence (Sullivan, 2013), a period in which supportive social figures shift from parents to peers, and contribute to better adjustment in adulthood. Children and adolescents with at least one supportive friendship are more likely to be protected against social and emotional problems, such as loneliness, social withdrawal and depressive symptoms (Asher & Paquette, 2003; Bolger, Patterson, & Kupersmidt, 1998; Criss, Pettit, Bates, Dodge, & Lapp, 2002; Lansford, Criss, Pettit, Dodge, & Bates, 2003; van Harmelen et al., 2016; Waldrip, Malcolm, & Jensen-Campbell, 2008). In contrast, adolescents without close friends are less well-adjusted and have less opportunities to improve social skills (Rubin, Wojslawowicz, Rose-Krasnor, Booth-LaForce, & Burgess, 2006; Vitaro, Boivin, & Bukowski, 2009).

Although the ability to develop a network of social support and to maintain intimate relationships are critical for well-being over time, these tasks are challenging for some children. Previously institutionalized youth may have difficulties forming and maintaining friendships, because they often lack significant sources of security and support (Zeanah, Smyke, Koga, Carlson, & Group, 2005), social skills, and express disinhibited social behaviors towards strangers and peers (Almas et al., 2012; Bruce, Tarullo, & Gunnar, 2009; Guyon-Harris, Humphreys, Fox, Nelson, & Zeanah, 2018; Sonuga-Barke, Schlotz, & Kreppner, 2010). Indeed, difficulties in relating and interacting with peers are widely reported in previously institutionalized children (Almas et al., 2015; Pitula et al., 2014; Raaska et al., 2012); however, less is known about their friendship quality and interactions with friends during adolescence.

The small set of studies on the friendships of previously institutionalized adolescents have relied on self- or parent-report to measure the number of friends and the presence of a best friend. These studies report mixed evidence of both less supportive friendships (Hodges & Tizard, 1989), as well as comparable friendship quality in post-institutionalized compared to never-institutionalized youth (Hawk & McCall, 2014; Vorria, Ntouma, & Rutter, 2014). Although previously institutionalized youth report having fewer friends than those in family care (Erol, Simsek, & Münir, 2010), the majority (97%) report having a best friend (Hawk & McCall, 2014). These findings suggest that the ability to build a close friendship is not completely compromised in previously institutionalized youth. Yet, no studies to date have used structured laboratory tasks to observe and characterize the friendship quality of previously institutionalized adolescents during dyadic interactions; only two studies have used structured laboratory tasks to observe how previously institutionalized children interact with an unfamiliar peer (Almas et al., 2015; DePasquale & Gunnar, 2020). To provide a comprehensive examination of previously institutionalized adolescents’ friendships, the present study uses a multidimensional assessment of friendships including self- and friend-report, as well as behavioral observations during multiple interactions with a friend in the laboratory.

Research has also been devoted to studying how early close emotional bonds between infants-and-caregivers create a foundation upon which later interpersonal skills and competence develop, following a central theme of attachment theory (Bowlby, 1982). A caregiver who is available and responsive to the infants’ needs is thought to build positive social expectations, reciprocity, empathy and self-worth, which contribute to the development of social competence (Bowlby, 1982; Van IJzendoorn, 1990). Indeed, studies suggest early attachment security with a caregiver is associated with social competence in peer relationships and positive interpersonal outcomes compared to those with insecure and other attachment styles (Englund, Kuo, Puig, & Collins, 2011; Fraley, Roisman, Booth-LaForce, Owen, & Holland, 2013; Groh et al., 2017; Pallini, Baiocco, Schneider, Madigan, & Atkinson, 2014; Weinfield, Ogawa, & Sroufe, 1997). Unlike children who have never spent time in an institution and who develop attachment to a primary caregiver, children reared in institutions often do not express attachment behaviors in a differentiated way toward a single caregiver or show atypical and disorganized patterns, characterized by disoriented and frightened behaviors (Chisholm, 1998; O’Connor, Bredenkamp, Rutter, English, & Team, 1999; Tizard & Rees, 1975; Vorria et al., 2003; Zeanah et al., 2005). Though, attachment quality can be enhanced after removal from institutions and integration into foster or family care (Chisholm, 1998; O’Connor et al., 2003; Smyke, Zeanah, Fox, Nelson, & Guthrie, 2010; Tizard & Hodges, 1978). Nevertheless, prospective longitudinal studies examining the quality of early attachment experiences among previously institutionalized children in foster care and their impact on adolescent friendships are lacking. Research of this nature has implications for understanding the effectiveness of interventions and adjustment in adulthood following early institutional rearing, as adolescents shift their attachment-related functions from parents to peers, relying on friends as support systems. From an attachment perspective, friendships serve important attachment functions and may compensate for missing or poor caregiver relationships among previously institutionalized adolescents who lack security from parents. For example, prior work has shown that adolescents who lack secure attachment to their parents are likely to select peers to fulfill attachment functions (Nickerson & Nagle, 2005). From a developmental perspective, positive friendships may help previously institutionalized adolescents adjust to challenges in their transition to adulthood. For example, high quality friendships serve as social buffers against maladjustment and psychopathology among children and adolescents exposed to early adversity or those who were adopted (Bolger et al., 1998; Criss et al., 2002; Paniagua, Moreno, Rivera, & Ramos, 2019).

The present study is part of the Bucharest Early Intervention Project (BEIP), a randomized controlled trial of foster care as an alternative to institutional care. Participants include three groups: 1) adolescents who as infants were abandoned and randomized to the care as usual group within institutions, 2) adolescents who as infants were abandoned and after 6-30 months of institutional rearing were randomized to the foster care group, and 3) adolescents who never experienced institutional care (i.e., the never-institutionalized group). A prior study on this sample found that the majority of infants assessed in institutions (~80%) lacked an organized attachment (Zeanah et al., 2005). Though after placement into foster care at 42 months, a greater proportion (~50%) of the foster care children exhibited secure attachment compared to the care as usual group (Smyke et al., 2010). Additionally, earlier age of placement, before 24-months of age, increased the likelihood of developing secure attachment at 42 months (Smyke et al., 2010). In the current assessment at age 16 years, we used a combination of questionnaires and observations during dyadic interactions with a friend to examine four types of friendship outcomes: 1) Friendship quality (i.e., measured through the participant and the friend’s perception using questionnaires and through behavioral observations of the dyadic interaction with the friend); 2) Friendship quantity (i.e., number of close friends); 3) The prevalence of reciprocal friendship (i.e., identified through mutual nomination by the participant and the friend); and 4) Who the participants befriend (i.e., descriptions of the friend’s characteristics, including age, sex, and whether they experienced institutional rearing). These outcomes have predictive utility for later psychosocial health, as they reflect functional (e.g., emotional support) and structural (e.g., size of friendship network) aspects of social support (Hakulinen et al., 2016; Rubin et al., 2004). Also, people tend to befriend others who have similar characteristics (Hartup & Stevens, 1997; Laninga-Wijnen et al., 2019).

We had three aims. First, our randomized trial was designed to test the effectiveness of foster care versus care as usual in institutions, as such the main goal of the study was to use a confirmatory approach to assess the intervention effect of foster care on adolescent friendships. We hypothesized that adolescents, who were assigned to the foster care group between 7 to 33 months of age, would have higher friendship quality and more friends compared to those who were in the care as usual group. Furthermore, we hypothesized that adolescents, who were assigned to the care as usual group would have lower quality friendships and fewer friends compared to the never-institutionalized group. Second, following empirical evidence and attachment theory suggesting the positive effects of attachment security, we took a confirmatory approach to examine the effect of attachment security during early childhood on adolescent friendships across study groups, as well as additive effects of foster care and attachment security. We hypothesized that secure attachment to a caregiver at 42 months of age would predict better friendship outcomes relative to insecure attachment, across groups. In terms of additive effects, we expected individuals in the foster care group with secure attachment to caregivers at 42 months to have higher quality friendships and more friends compared to those in foster care who had insecure attachment, and the care as usual group. Third, the timing of foster care placement varied between 7 to 33 months of age, this enabled us to further explore timing effects of intervention within the foster care group. We expected earlier age of foster care placement to be associated with more positive friendship outcomes. Additionally, given that earlier age of placement was associated with attachment security at 42 months in the foster care group (Smyke et al., 2010), we expected attachment security with foster caregivers to mediate the associations between earlier age of placement and positive friendship outcomes.

Method

Participants

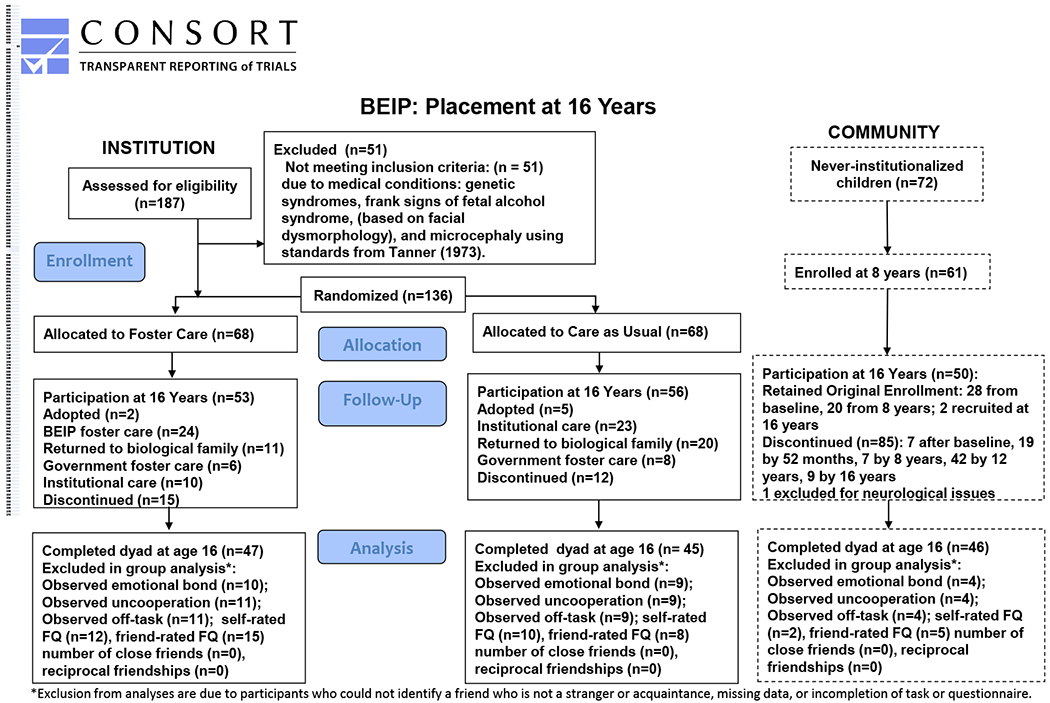

Participant selection and trial design are summarized in the consort diagram (Figure 1). In 2001, 187 infants ranging from ages 6 to 31 months who were living in one of six institutions for young children in Bucharest, Romania, completed physical examinations; 51 children were excluded for serious medical conditions (e.g., genetic and fetal alcohol syndromes). The final sample at baseline included 136 children (ages 6- 30 months). After the baseline assessment, half of the children were randomly assigned to care as usual (CAUG: n=68; 33 female, 48.5%; 34 Romanian, 50%, 21 Roma, 20.9%, 13 other or unknown, 19.1%) and half to foster care (FCG: n=68; 34 female, 50%; 42 Romanian, 61.8%, 18 Roma, 26.5%, 8 other or unknown, 11.8%). The age at which children were placed into foster care ranged from 6.81 to 33.01 months (M age= 22.63, SD= 7.33). At baseline, a group of sex- and age-matched never institutionalized children (NIG: n= 72; 41 female, 56.9%; 66 Romanian, 91.7%, 4 Roma, 5.6%, 2 other or unknown, 2.8%) was recruited from pediatric clinics in Bucharest, and because the NIG did not always return to the study, additional NIG were recruited at age 8 (n= 61) and age 16 (n=2).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram.

The number of participants varied across visits. At age 42 months, 169 participants (57 CAUG, 29 female; 61 FCG, 29 female; 51 NIG, 27 female) completed the Strange Situation Procedure (Ainsworth, Blehar, & Waters, 1978). At age 16, 138 participants (45 CAUG, 26 female, 23 Romanian, 17 Roma, and 5 other or unknown; 47 FCG, 25 female, 28 Romanian, 15 Roma, 4 other or unknown; 46 NIG, 18 female, 44 Romanian, 1 Roma, 1 other or unknown) completed dyadic tasks and questionnaires on friendship with a self-selected close friend (see Table 1). Individuals with missing data did not differ on key variables, such as attachment security at 42 months (p= .871), intelligence quotient (p=.976) and social skills (p=.119) at age 8, or demographic variables, such as sex (p=. 716). However, the NIG had more missing data compared to CAUG and FCG (p< .001) since they did not consistently return to the study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants, their friends, and group differences in quantity, length, and perceived quality of friendships.

| P values from group contrasts |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAUG | FCG | NIG | FCG vs CAUG | CAUG vs NIG | FCG vs NIG | |

| Median age of best friend (range)a | 16 (12–20) | 16 (10–29) | 17 (12–20) | .068 | .002 | .834 |

| Length of best friendship (n, %)a | .433 | .476 | .952 | |||

| Less than 1 year | 6 (13.4%) | 4 (8.4%) | 4 (8.9%) | |||

| Over 1 year | 39 (86.6%) | 44 (91.6%) | 41(91.1%) | |||

| Median age of all close friends (IQR)a | 16 (2) | 16 (1.5) | 17 (1.1) | .305 | .023 | .486 |

| Number of close friends (Median, IQR)a | 2 (1.5) | 3 (2) | 4 (3) | .296 | .004 | .079 |

| Reciprocated best friendship (n, %)b | 28 (63.6%) | 30 (62.5%) | 34 (75.6%) | .854 | .309 | .224 |

| Reciprocated close friendship (n, %)b | 30 (68.2%) | 33 (68.8%) | 36 (80.0%) | .984 | .297 | .279 |

| Self-rated FQ (Mean, SD)c | 2.74 (.66) | 2.79 (.69) | 3.01 (.69) | .742 | .082 | .166 |

| Friend-rated FQ (Mean, SD)c | 2.76 (.68) | 2.71 (.75) | 2.84 (.64) | .763 | ..590 | .412 |

| Participant age (Mean, SD) | 16.77 (.50) | 16.77 (.74) | 17.01 (.63) | |||

| Participant sex (n female, %) | 26 (54.17%) | 25 (50.0%) | 18 (37.5%) | |||

| Participant ethnicity (n, %) | ||||||

| Romanian | 23 (51.1%) | 28 (59.6%) | 44 (95.7%) | |||

| Roma | 17 (37.8%) | 15 (31.9%) | 1 (2.2%) | |||

| Other or unknown | 5 (11.1%) | 4 (8.5%) | 1 (2.1%) | |||

Note. IQR= Interquartile range. FQ=friendship quality.

All analyses adjust for sex differences.

n=138.

n=137.

Analyses on friend and self-rated FQ exclude those paired with acquaintances or strangers and further adjust for whether the peer had a history of institutional rearing:

self-rated, n= 112; friend-rated, n=113.

Over the years of the study, the Romanian government has made policy changes that led to the formation of a public foster care program to reduce the number of children living in institutions. As a result of these policies, many of the CAUG and FCG children from our study were removed from institutions or the BEIP’s foster care and placed into government foster care, reunited with their biological families or adopted (see Figure 1). The number of caregiving disruptions varied in these children: The CAUG experienced between 2-10 disruptions up to age 16, and the FCG experienced 1-7 disruptions. Notably, the number of caregiving disruptions is not related to friendship outcomes (Supplemental Table 8). Although many of the CAUG and FCG children were no longer in their randomized placements at age 16, we adopted an intent-to-treat approach for the data presented in this paper. This approach considers each participant as a member of their initial randomly assigned group and allows the comparison of foster care intervention by comparing the intervention (FCG) and institutionalized (CAUG) group.

Strange Situation: Attachment Classification at 42 months

Quality of attachment to caregivers was measured at 42 months (Smyke et al., 2010) using the Strange Situation Procedure (Ainsworth et al., 1978) and was coded using the MacArthur Preschool system (Cassidy, Marvin, & the MacArthur Working Group, 1992). The foster care children were seen with their foster mothers, and the institutionalized children were seen with their “favorite” caregivers who regularly worked with the child at the institution and knew the child well. Coders, blinded to group status, were trained to reliability on the MacArthur Preschool System to classify attachment behaviors, including secure, avoidant, ambivalent, disorganized-controlling, and insecure-other. Secure vs. insecure (all other) attachment classifications and continuous scores of attachment security were used in analyses. As previously reported, 30 FCG (49.2 %), 10 CAUG (17.5 %), and 33 NIG (64.7 %) were securely attached to a caregiver at 42 months of age (Smyke et al., 2010). Across groups, children classified with secure attachment received higher ratings on the continuous measure of attachment security than those with insecure attachment, p <.001.

Observed Friendship Quality and Behaviors in Dyadic Interactions with a Peer at age 16

Procedure of the dyad.

Participants were asked to nominate three of their closest friends and invite one of the three friends to accompany them to the laboratory to play games together. In the nomination process, participants were asked to nominate friends of the same age and sex. If no friend was nominated within this criterion, the research assistant prompted participants to generate potential friends using broader criteria, in the following order: a) same-sex friends of a similar age (i.e., within 5 years), b) opposite-sex friends of the same age, c) opposite-sex friends of a similar age, d) a child living in the same home as the participant who is not in the study and is not a sibling, e) a cousin, f) a sibling.

At the laboratory visit, demographic characteristics of the peers, including age, sex, and relationship with the participant were collected. Participants and their friend completed three tasks in the following order: Lego, Planning an Outing, and Happy-Angry. For the Lego task (8 minutes), each participant and their friend were asked to choose an animal (a monkey, teddy bear, or squirrel) and build it together using Lego blocks. For the Planning an Outing task (8 minutes), each participant and their friend were asked to discuss and write down some things that they would do together on an outing the next weekend. For the Happy-Angry task (5 minutes), each participant and their friend were asked to think about what the other person has done in the past to make them happy and angry, and to discuss these incidences with each other. The order of the happy and angry discussions was counterbalanced across dyads.

Behavioral coding of the dyad.

The tasks were video-recorded. A pair of blinded-observers whose first language was Romanian coded the participants’ behaviors in 30 second epochs. A subset of recordings (20% of each task) was coded by both observers to determine reliability (inter-class correlations, or ICCs); once reliability was achieved, the remaining recordings were coded by one observer. We used a similar behavioral coding scheme of social behaviors that was previously applied to this sample’s social behaviors in a dyadic interaction at age 8 (Almas et al., 2015). In the Lego task, which required working together, the presence and absence of the participants’ cooperative behavior (i.e., coordinating actions with the friend to complete the task), conversation (i.e., verbal interactions with the friend), and independent working behaviors (i.e., completing the task without interacting with the friend) were coded every 30 seconds (1=present; 0=absent). In the Planning an Outing and Happy-Angry tasks, which required discussions of ideas and feelings, participants’ emotions (i.e., 2=positive, 1=neutral, or 0=negative), arousal (i.e., 1= completely unaroused with monotone voice, neutral facial expression, and no gesturing or body movement; 4=completely aroused with animated voice, facial expressions, and energetic or enthusiastic gesturing and body movements), as well as the presence and absence of off-task behaviors (i.e., focusing on other activities or talking about something unrelated to the tasks, 1=present; 0=absent) were coded every 30 seconds. Each of the coded behaviors was averaged across all of the 30 second epochs. At the end of each task, a global score of friendship quality (1= low; 5= high) was also coded for the entire task based on the degree to which the dyad members appeared to enjoy each other’s company, showed signs of working well together, and displayed warmth and mutual joy during the interaction. Inter-rater reliability (ICCs) of the behavioral codes was acceptable across tasks (Lego task: Cooperation, .95, Conversation, .86, Independent Work, .98, Friendship Quality, .85; Planning an Outing task: Emotions, .77, Arousal, .83, Off-task, .99, Friendship Quality, .85; Happy-Angry task; Emotions, .82, Arousal, .75, Off-task, .79, Friendship Quality, .80).

To reduce the dimensionality of the data, correlations among the coded behaviors across the three tasks were examined and a principle component analysis (PCA) with a quartimax rotation was performed. Correlations among coded behaviors are shown in Supplemental Table 1. Observed friendship quality, emotion, and arousal positively correlated with each other, r’s= .24 to .66, p’s < .05. Cooperation, conversation, and independent work positively correlated with each other, r’s= .67 to .82, p’s < .05. Off-task behaviors positively correlated with each other across tasks, r= .43, p’s < .05. Results from the PCA suggested three orthogonal factors, each with an eigenvalue over 1.4 and together explained 65.58% of the variance (Supplemental Table 2): 1) Positive Emotional Bond composed of emotion, arousal and friendship quality; 2) Cooperation composed of cooperation, conversation and independent work (reversed); and 3) Off-task behaviors in the Happy-Angry and Planning an Outing tasks. A composite score of emotional bond was calculated by averaging the standardized scores of the indicators; higher scores indicate a more positive emotional bond. Because cooperative and off-task behaviors were negatively and positively skewed with ceiling and floor scores, respectively, they were transformed into binary variables by counting individuals who were always cooperative and on-task versus those who exhibited any uncooperative and off-task behaviors. These composite scores of Positive Emotional Bond, Cooperation, and Off-task behaviors were used in subsequent analyses.

Perceived Friendship Quality, Friendship Quantity, and Prevalence of Reciprocal Friendships at age 16

Participants and friends were each asked to complete measures of friendship quality with respect to their best friend using the Friendship Quality Questionnaire (FQQ) (Parker & Asher, 1993). The FQQ measures multiple dimensions of relationship quality, including validation and caring, conflict resolution, conflict and betrayal, help and guidance, companionship and recreation, and intimate exchange. Prior studies have shown strong reliability and convergent validity of the FQQ with measures of reciprocal friendship and peer acceptance (Parker & Asher, 1993), as well as predictive validity for less internalizing and externalizing problems (Rubin et al., 2004). Total scores of self-and friend-reported friendship quality were calculated by averaging the five dimensions which were intercorrelated (r’s= .27‐.75, p’s <.001), excluding conflict and betrayal. The total score showed strong internal consistency across friend- and self-report (α= .84- .85).

Additionally, participants and friends completed a modified version of the Network of Relationship Inventory (NRI; (Furman & Buhrmester, 2009) to provide complimentary descriptions of how many friends they have, whom they befriend, and whether there is mutual agreement in the friendships. The original NRI, which assesses multiple relationships with parents as well as friends and multiple facets of positive and negative relationship qualities, has demonstrated strong reliability and validity (i.e., convergence among reporters) in adolescent samples (Furman & Buhrmester, 2009; Furman, Stephenson, & Rhoades, 2014). In the modified NRI, we only asked participants and their friends to each nominate up to eight of their closest friends, and the age and sex of each friend, beginning with the best friend. We coded the number of close friends, as well as the length of the best friendship using an item asking how long the participant has known the friend. Responses included “1-6 months”, “6-12 months”, and “over 1 year”. Only a small percentage (~4%) of participants have known their best friends for 1-6 months, thus length of friendship was recoded as a binary variable (“less than 1 year” and “over 1 year”). Reciprocal best-friendship (yes or no) was coded when the participant and the best friend mutually nominated each other as the first (i.e., closest) friend. Reciprocal close-friendship (yes or no) was coded when the participant nominated the friend as the first friend, but the friend nominated the participant as the second to eighth close friend.

Data Analyses

Main analyses.

The first aim was to examine the effects of foster care and institutional care on friendship outcomes. Following an intent-to-treat analysis approach, we examined the intervention effect of foster care by comparing the FCG to the CAUG on friendship outcomes (i.e., friendship quality, quantity, and behaviors with the friend) at age 16. To examine the effects of early institutionalization, we compared the CAUG and FCG to the NIG. We conducted pairwise non-parametric approximate general independence permutation tests with 10000 Monte Carlo resamplings in the R package “coin” (Hothorn, Hornik, Van De Wiel, & Zeileis, 2008). Permutation tests randomly reshuffle subjects in the groups to create valid distributions without assumptions of normality, which are ideal for our data (e.g., counts of friends, age of friends). For binary outcomes, logistic regression models were used. In all analyses, we accounted for sex differences. In analyses involving self- and friend-rated friendship quality and observed behaviors, we further accounted for whether the peer had exposure to institutional rearing as 33% of the CAUG and 26% of the FCG brought in a peer who has experienced institutionalization (see Table 2A); we also excluded 19 participants (8 CAUG, 9 FCG, 2 NIG) because they were unable to bring in a friend defined as someone with whom they had a close relationship (i.e., those paired with an acquaintance or stranger were excluded) (Table 2B).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the peer (A) and observed behaviors of the participant (B) at the dyadic assessment at age 16.

| Group contrasts |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAUG | FCG | NIG | FCG vs CAUG | CAUG vs NIG | FCG vs NIG | |

| (A) Characteristics of the friend | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Relationship with participant (n,%) | ||||||

| Friend | 28 (62.2%) | 25 (53.2%) | 39 (84.8 %) | OR= .69, p=.396 | OR= .26, p=.010 | OR=.18, p=.001 |

| Sibling or cousin | 8 (17.8%) | 9 (19.1%) | 2 (4.3%) | |||

| Boy/girlfriend | 1 (2.2%) | 4 (8.5%) | 3 (6.5 %) | |||

| Acquaintance | 1 (2.2%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| No relationship | 7 (15.6%) | 8 (17.1%) | 2 (4.3%) | |||

| Peer is same sex as participant (n, %) | 36 (85.7%) |

35 (76.1%) |

39 (84.8%) |

OR=.60, p=.346 | OR= .97, p=.964 | OR=.59, p=.321 |

| Peer’s age (Median, range) | 16.40 (12 – 20) |

16.62 (10 – 28) |

17.19 (12 – 20) |

p=.224 |

p=.010 | p=.801 |

| Peer has history of institutional rearing (n, %)a | 14 (32.6%) | 12 (25.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | OR=.00, p=.997 | NA | NA |

|

| ||||||

| (B) Observed behaviors | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Emotional bond (Mean, SD)b | 1.34 (.68) | 1.55 (.73) | 1.68 (.75) | p=.205 | p=.036 | p=.429 |

| Off-task (n, %)c | 12 (33.3%) | 10 (27.8%) | 6 (14.3%) | OR= .71, p=.512 | OR= 3.11, p=.058 | OR= 2.21, p=.185 |

| Uncooperation (n, %)d | 12 (33.3%) | 12 (33.3%) | 11 (26.8%) | OR=.936, p=.905 | OR=1.07, p=.905 | OR=1.10, p=.858 |

| Secure (vs insecure) attachment 42m (n, %)e | 3 (8.8%) | 18 (48.6%) | 18 (69.2%) | |||

| Organized (vs disorganized) attachment 42m (n, %)e | 20 (58.8%) | 26 (70.3%) | 23 (88.5%) | |||

Note. OR= odds ratio. NA= not available due to 0 occurrence in the reference group.

All analyses adjust for sex differences, except “whether peer is same sex”. 138 participants completed the dyadic assessment (45 CAUG, 47 FCG, 46 NIG).

n=136.

Analyses on observed behaviors exclude those paired with acquaintances or strangers and further adjust for whether the peer had a history of institutional rearing:

n= 115 (36 CAUG, 37 FCG, 42 NIG)

n=114 (36 CAUG, 36 FCG, 42 NIG)

n=113 (36 CAUG, 36 FCG, 42 NIG)

n with attachment data at 42 m= 97 (34 CAUG, 37 FCG, 26 NIG).

The second aim was to examine the effects of attachment security at 42 months on friendship outcomes at age 16 across groups, as well as additive effects with study groups. We first tested the association between secure attachment scores and friendship outcomes across groups using partial correlations adjusting for sex. We then examined these associations within each group and used Fisher’s r-to-z transformations to test whether the correlations were different across groups.

The third aim was to examine timing effects of the intervention, given that earlier age of foster care placement was associated with higher attachment security scores at 42 months in this sample (Smyke et al., 2010). We examined whether age of placement indirectly predicted friendship outcomes via its effect on attachment security within the FCG. Path models with indirect effects were performed in Mplus, version 8, for friendship outcomes that were significantly associated with attachment security in the prior correlational analyses. In all models, we adjusted for sex by adding regression paths to the outcome and included residual covariances between sex and age of placement. Weighted least square mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) and maximum likelihood (MLM) estimations, which provide robust standard errors to correct skewness, were used for categorical and continuous outcomes, respectively. Listwise deletion was used and participants paired with strangers and acquaintances were excluded in analyses involving observed behaviors and friendship quality. Statistical significance of indirect effects were determined with 10000 bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002).

Sensitivity analyses.

We conducted three sets of sensitivity analyses. First, we repeated the main analyses testing group differences and included only participants who brought in a friend (i.e., excluding those who were paired with siblings or cousins, boy- or girl-friends, in addition to excluding acquaintances and strangers in the primary analysis). Second, we examined whether secure attachment classifications (secure vs insecure) at 42 months would reveal the same results as continuous attachment security scores. The secure vs. insecure classes were disproportionately distributed within the CAUG and NIG—only 3 CAUG were securely attached and had usable data in the dyad and only 6 NIG were insecurely attached and had usable data in the dyad (Table 2). This limited our analysis to comparing secure and insecure subgroups within the FCG with the CAUG, and NIG. Third, to address whether the effects of study group and attachment security are independent predictors of friendships, we repeated the analyses by including additional covariates that could be on the causal pathway to positive friendships including (1) intelligence quotient (IQ) and (2) social skills measured at age 8. IQ was assessed by trained examiners using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-IV) (Williams, Weiss, & Rolfhus, 2003) and details have been previously reported (Fox, Almas, Degnan, Nelson, & Zeanah, 2011). Social skills were reported by parents and teachers using the Social Skills Rating System (Gresham & Elliott, 1990), which assesses children’s cooperation, responsibility, and other prosocial and empathic behaviors. Items include, “introduces self to new people without prompting” and “gives compliments to peers”. Responses were rated on a 3-point scale (0= never; 2= very often). Parent and teacher ratings were correlated (r= .40, p < .05), as such an average score was used in analyses.

Results

Characteristics of participants and their friends are shown in Table 1. Bivariate correlations showed significant correlations between self- and friend-rated friendship quality, r= .54, p <.05 (Supplemental Table 3). Reciprocal best and close friendships were significantly correlated with self-rated, but not friend-rated, friendship quality, r’s= .19, p’s <.05 (Supplemental Table 3). Also, self- and friend-rated friendship quality were significantly correlated with observed friendship quality in the Happy-Angry and Lego tasks (r’s= .19 to .25, p’s <.05), but not with friendship quality in the Planning an Outing task (Supplemental Table 4).

Intent-To-Treat Analysis: Foster Care Compared to Institutional Care

Perceived Quality, Quantity, and Reciprocal Friendships.

As seen in Table 1, the FCG did not differ from the CAUG on the prevalence of reciprocal best- and close-friendships, length of best- friendships, number of close friends, age of their friends, nor self- and friend-rated friendship quality.

Characteristics of the friend in the dyad.

Table 2A shows characteristics of the friend at the dyadic interaction. The majority of the participants brought in a same-sex friend. The FCG did not differ from the CAUG on the age of the friend, nor the odds of bringing a friend as opposed to bringing siblings or cousins, boy- or girl-friends, acquaintances, and strangers. Also, a comparable proportion of the CAUG (33%) and FCG (26%) brought in a friend who, like themselves, had a history of institutional rearing.

Observed behaviors with the friend.

Table 2B shows group differences in observed behaviors with the friend. There were no statistical differences between the FCG and CAUG on any of the observed behaviors (i.e., emotional bond, uncooperative, and off-task). Sensitivity analyses including only participants who brought in a friend showed the same pattern of findings (Supplemental Table 5). Also, sensitivity analyses that additionally adjusted for IQ and social skills at age 8 revealed the same results (Supplemental Table 6).

Institutional and Foster Care Compared to Typical Adolescents

Perceived Quality, Quantity, and Reciprocal Friendships.

As seen in Table 1, the institutionalized groups (both CAUG and FCG) did not differ from the NIG on the prevalence of reciprocal best-friendships (61-75%), nor the length of best-friendships, as the majority (87-92%) of adolescents across groups had known their best friends for more than one year. There were significant group differences in the age and quantity of close friends only: the CAUG reported having younger best- and close-friends, as well as fewer close friends than the NIG. In terms of the perceived friendship quality, there were no differences in the friends’ ratings or self-ratings across groups. The FCG and NIG were comparable on these outcomes.

Characteristics of the friend in the dyad.

As seen in Table 2A, both the CAUG and FCG were less likely to bring a friend (as opposed to siblings or cousins, boy- or girl-friends, acquaintances, and strangers) compared to the NIG. Furthermore, the friends of the adolescents in the CAUG were younger than the friends whom adolescents in the NIG brought in. There were no differences in the age of the friend of adolescents in the FCG compared to the NIG. Also, none of the friends of the NIG (0%) experienced institutional rearing.

Observed behaviors with the friend.

As seen in Table 2B, the CAUG showed less positive emotional bonding behaviors and more off-task behaviors (at trend level, p= .058) than the NIG. There were no group differences in uncooperative behaviors. The FCG and NIG were comparable on all observed behaviors. Sensitivity analyses which included only participants who brought in a friend (Supplemental Table 5) and sensitivity analyses adjusting for IQ and social skills showed the same pattern of results (Supplemental Table 6).

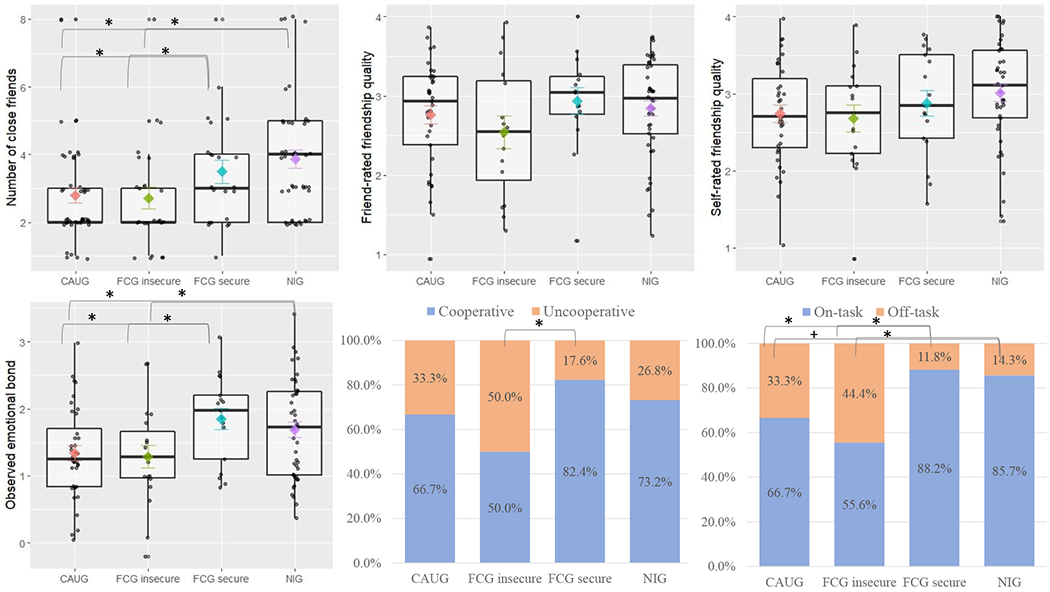

Effects of Early Attachment Security on Observed and Perceived Friendship quality and quantity

Attachment security was unrelated to whether the peer who participated in the dyad was a friend as opposed to a sibling or cousin, boy- or girl-friend, acquaintance, or stranger, b= −.005, SE= .139, p=.970. As seen in Table 3A, higher attachment security scores at 42 months were significantly correlated with more friends, higher emotional bonding behaviors, and were inversely correlated with uncooperative and off-task behaviors at age 16 in the full sample. When these relations were examined within groups, significant relations emerged for adolescents in the FCG, but not in the CAUG or NIG (Table 3A and Supplemental Figure 1). However, Fisher’s r-to-z transformations revealed no significant differences in the strength of associations between groups, p’s> .05. We noted that the majority of CAUG were insecurely attached and the majority of NIG were securely attached at 42 m (Table 2B), while attachment security in the FCG was evenly distributed. To further examine whether attachment security played a role in group differences, we used attachment classifications to split the FCG into secure and insecure subgroups and compared them with the CAUG and NIG in sensitivity analyses. Results are shown in Figure 2. The secure-FCG was comparable to the NIG on all outcomes; Both the secure-FCG and NIG had more friends and showed more positive bonding behaviors and less off-task behaviors than the insecure-FCG and CAUG. The insecure-FCG and CAUG were comparable on these outcomes. Sensitivity analyses adjusting for IQ and social skills showed the same pattern of results (Supplemental Table 7).

Table 3.

Partial correlations between (A) secure attachment scores at 42 m and friendship measures at age 16 across groups and within-group.

| (A) Secure scores 42 m | (B) Age of placement within FCG | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Measures at age 16 | Full Sample | CAUG | FCG | NIG | |

| Number of close friendsa | .33** | .19 | .36** | .16 | −.33* |

| Friend-rated FQb | −.07 | −.20 | .02 | −.15 | .20 |

| Self-rated FQb | .08 | .00 | .01 | .16 | −.00 |

| Observed emotional bondc | .26* | .23 | .31* | −.01 | −.12 |

| Observed uncooperationc | −.23* | .06 | −.33* | −.37 | .43** |

| Observed off-taskc | −.22* | −.02 | −.40* | .16 | −.02 |

Note. FQ= friendship quality.

p <.01.

p <.05.

All analyses adjust for sex differences:

n in secure scores=115 (42 CAUG, 47 FCG, 26 NIG), n in age of placement within the FCG= 46.

Analyses on friend and self rated FQ and observed behaviors exclude those paired with strangers and acquaintances and adjust for whether the peer had a history of institutionalization:

n with secure scores= 93 (33 CAUG, 34 FCG, 26 NIG), n with age of placement within the FCG= 31

n with secure scores=97 (34 CAUG, 37 FCG, 26 NIG), n with age of placement within the FCG=35.

Figure 2.

Results comparing secure and insecure subgroups within the FCG to the CAUG and NIG.

Note. *p< .05. +p< .06. Medians and means (diamonds) with standard errors are shown in box plots. All analyses adjust for sex differences. n in number of friends =137 (45 CAUG, 25 insecure-FCG, 22 secure-FCG, 45 NIG).

Analyses on friendship quality and observed behaviors exclude those paired with acquaintances or strangers and further adjusts for whether the peer had a history of institutionalization: n in friendship quality=112 (37 CAUG, 16 insecure-FCG, 15 secure-FCG, 44 NIG), n in observed behaviors= 114 (36 CAUG, 19 insecure-FCG, 17 secure-FCG, 42 NIG.

Timing Effects of Foster Care Intervention

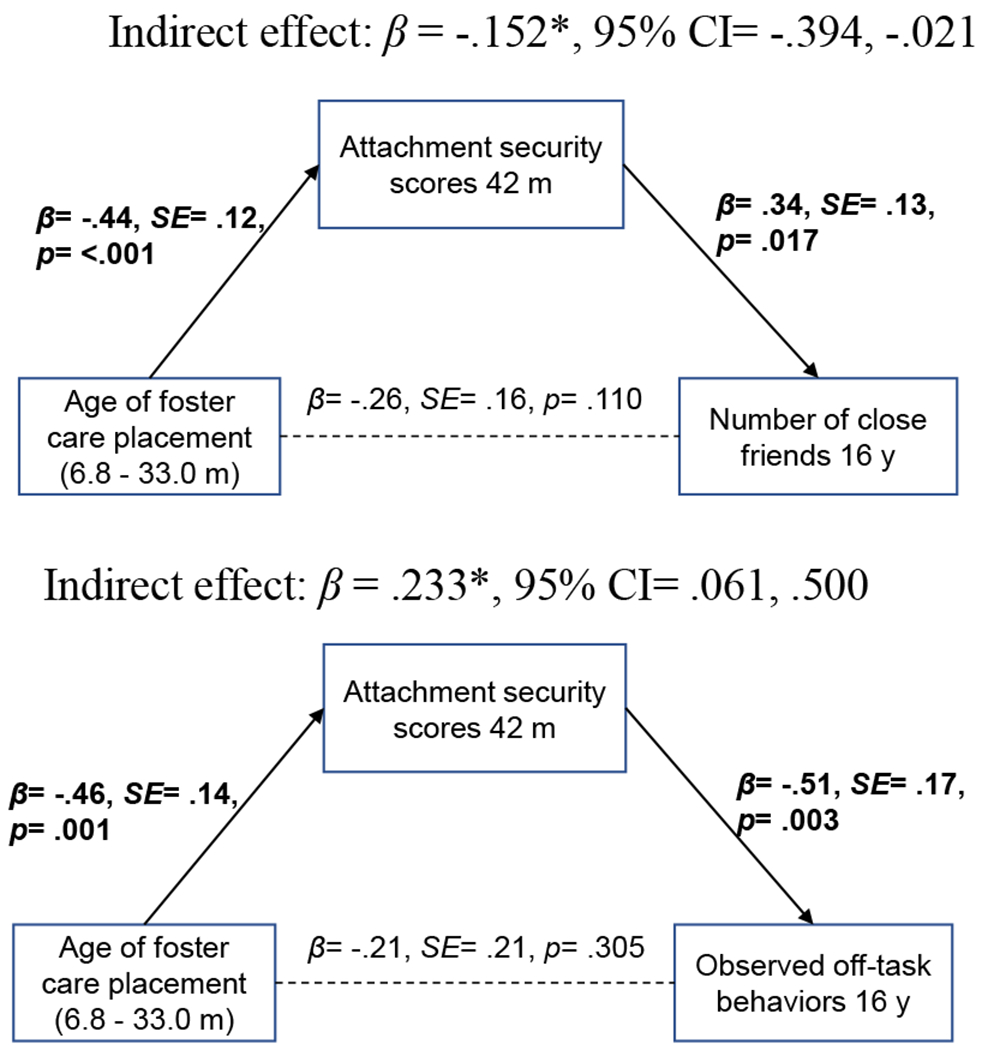

Among the FCG, timing effects of age of foster care placement was observed for some of the friendship outcomes. As seen in Table 3B, partial correlations adjusting for sex showed that earlier age of placement significantly correlated with more close friends and less uncooperative behaviors, but not with friendship quality or other behaviors. As previously reported (Smyke et al., 2010), earlier age of placement was related to higher attachment security scores, r= −.42, p< .001, and a greater likelihood of being categorized into the secure attachment class relative to the insecure class at 42 m, OR= .92, p= .047. Though, the effect of age of placement on secure attachment classification was not significant after adjusting for sex (OR=.93, p=. 092). Given these results, further path analyses testing indirect effects focused on attachment security scores and on outcomes that were significantly correlated with attachment security scores within the FCG (Table 3A), including the number of close friends and off-task behaviors.

Indirect effect of age of placement on friendship outcomes via attachment security within the foster care group.

Figure 3 shows results from path analyses testing indirect effects. As seen in Figure 3, earlier age of foster care placement predicted higher attachment security scores. In turn, higher attachment security scores predicted more close friends and less off-task behaviors when interacting with the friend. Follow-up analyses indicated that the indirect effects of attachment security in the associations between age of placement and number of close friends (β = −.152, 95% CI= −.394, −.021) and off-task behaviors (β = .233, 95% CI= .061, .500) were significantly different than zero. These results held in sensitivity analyses adjusting for IQ and social skills (see Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Indirect effects of age of placement on number of close friends and observed off-task behaviors through attachment security within the foster care group.

Note. Standardized estimates are shown.

All models adjust for sex differences: n=46 in analysis for number of close friends. The model testing observed off-task behaviors excludes those paired with strangers and acquaintances and further adjust for whether the peer had a history of institutionalization: n=35 in analysis of observed behaviors.

Discussion

The present prospective longitudinal study used a combination of questionnaire and observational measures to examine how early institutionalization and foster care intervention shape adolescent friendships. Our results revealed three notable findings. First, the friendships of adolescents with a history of institutionalization (both FCG and CAUG) are similar to those of typical adolescents in the NIG in terms of the prevalence of reciprocal friendships and length of friendships, at least according to their reports. However, when asked to bring in a friend, adolescents in both the FCG and CAUG were less likely to bring in a friend, typically defined as an unrelated same-sex peer, compared to the NIG. Further dissimilarities across groups appeared in the age of the friend, number of friends, and the observed emotional bonds. Compared to adolescents in the NIG, adolescents in the CAUG had fewer friends, and their friends were younger across self-report measures and the dyadic observation. Interestingly, adolescents in the CAUG exhibited less positive emotional bonding behaviors with the friend during the interactions compared to adolescents in the NIG, although self-reported friendship quality measured by questionnaires was comparable across groups. These findings extend prior studies examining friendships of previously institutionalized adolescents using self- and parent-report, which consistently report fewer friends but mixed evidence on friendship quality (Erol et al., 2010; Hawk & McCall, 2014; Hodges & Tizard, 1989; Vorria et al., 2014). Together, our findings and those from prior studies suggest that adolescents who experienced institutionalization are able to make and sustain friendships that they perceive as supportive. Nevertheless, adolescents with prolonged institutionalization (i.e., the CAUG) have fewer friends in their social network; they show less positive emotional connections with friends in situations that challenge them to cooperate or become emotionally vulnerable; and they are spending time with younger friends, possibly because they are less mature and easier to interact with. From a social capital perspective, these friends’ characteristics make them ineffective social resources in helping adolescents transition to adult roles because they are unlikely to provide age-appropriate advice nor opportunities to advance social skills (Sullivan, 2013). From an attachment perspective, these findings in the CAUG highlight the lasting influence of lacking an available primary caregiver in a depriving environment on friendships; the accumulation of poor relationships or a lack of relationships across development is expected to further shape poor romantic relationships in adulthood (Berlin, Cassidy, & Appleyard, 2008; Fraley & Davis, 1997; Sroufe, Egeland, Carlson, & Collins, 2005).

Second, we did not observe an intervention effect of foster care, as adolescents in the FCG were not significantly different from the CAUG on measures of friendship quality or quantity. The FCG were not significantly different from the NIG either. This pattern of overlap with both adolescents with prolonged institutionalization (i.e., the CAUG) and typical development (i.e., NIG) indicate that there is a great degree of variability or individual differences within the FCG. Possible individual differences that might shape friendship outcomes include different caregiving experiences in the FCG. Notably, even though we used an intent-to-treat approach to obtain conservative estimates of intervention effects, not all of the FCG children remained in the same foster home after their initial random assignment as the number of disruptions in foster care placements range from one to seven (Figure 1). Although the number of caregiving disruptions and friendship outcomes were unrelated within the FCG (Supplemental Table 8), the overlapping scores observed in the FCG compared to the two other groups prompted us to probe other factors, particularly the early child-caregiver attachment relationship, that might be responsible for promoting better or worse outcomes.

Third, examination of attachment security on adolescent friendship outcomes within the FCG suggested that enhanced early attachment security with the foster parent, resulting from earlier age of placement, accounted for some of the adolescent friendship outcomes. We found that adolescents in the FCG with secure attachment at 42 months reported having more friends and exhibited more positive behaviors with the friend in the dyadic interactions at age 16, manifest in more positive emotional bonding, cooperative, and less off-task behaviors, compared to FCG with insecure attachment at 42 months. Additional analyses comparing the secure and insecure subgroups within the FCG to the CAUG and NIG indicated that the FCG who were able to form secure attachment to their caregivers and never institutionalized adolescents were comparable; Both secure-FCG and NIG had more friends, and showed more positive behaviors with their friends in the dyad compared to insecure-FCG and CAUG. These findings highlight the critical and positive impact of early intervention focused on establishing a foundation of secure attachment for successful social development as posited by attachment theory (Bowlby, 1982; Van IJzendoorn, 1990). These findings suggest that it is not simply placement into foster care which impacts social development, but specifically the formation of secure attachment with a caregiver, that provides a new and strong foundation upon which children can develop into more socially competent adolescents who are able to form close friendships. These findings converge with prospective studies which find that early attachment security with caregivers is associated with social competence with peers (Englund et al., 2011; Fraley et al., 2013; Shulman, Elicker, & Sroufe, 1994; Weinfield et al., 1997). Furthermore, our findings extend studies using interventions to enhance child-caregiver attachment of maltreated children (Bernard et al., 2012; Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Toth, 2006; Fisher & Kim, 2007), by showing the lasting positive effects of such enhanced early child-caregiver relationships on social development into adolescence. A logical next step is to use a life course approach to provide insight into the timing of psychosocial risks on social functioning and health in adulthood. That is, the effects of psychosocial deprivation in early childhood, as well as the effects of chronic poor relationships across multiple development periods on adult romantic relationships, and how these relationships across the life course contribute to mental and physical health.

Our study is not without limitations. First, although the present study was based on a well-characterized sample in a randomized controlled trial followed from infancy to adolescence, the sample is relatively small. This limits the effects that we cannot detect and constrains the analyses that can be performed. A prior study on this sample at age 8 using a similar dyadic task to understand intervention effects on social behavior with an unfamiliar peer suggests that the detectable effect sizes between 49 CAUG and 51 FCG are small to moderate (d= .22 to .53) (Almas et al., 2015). A power analysis, using the prior estimate (d= .53) in a one-tailed t-test with two independent groups (α= .05, 1‐β= .80), suggests that at least 45 individuals in each group is required to reject the null hypothesis. However, many of our tests involving observed behaviors and perceived friendship quality excluded more individuals. As such, we may not have power to detect some effects. Due to small sample sizes, comparison of secure vs insecure classes within the CAUG or more specific attachment classifications within the institutionalized groups would not yield interpretable results. Also, due to small sample sizes, we are unable to examine interaction effects with sex. Past studies have found sex differences in how adolescent girls and boys express intimacy in friendships and some aspects of peer relationships (Hussong, 2000; Rose & Rudolph, 2006), though meta-analytic evidence suggests no sex difference in the relation between attachment security and social competence, including friendships (Groh et al., 2014). Future studies with larger samples will need to address the potential role sex differences may play. Second, in the dyadic interactions, there was variability in the nature of friendships, as some participants brought in boy- or girl-friends, cousins and siblings. We acknowledge that adolescents’ close friends often include a cousin, sibling, or a romantic partner, thus we allowed the inclusion of these types of “friends” to reflect the true closeness as identified by the participants themselves. Notably, some siblings of the FCG and CAUG were not biologically related, and they met through living in the same foster homes. Nonetheless, sensitivity analyses conducted on only participants who brought in a friend, defined as same-sex with no biological or familial relation, revealed the same pattern of results. To ensure replicability, future studies using larger samples sizes are needed. Lastly, because our sample is from one geographic region in Romania, future studies from other countries and cultures are needed to further examine the generalizability of the effects of early institutionalization and attachment relationships on adolescent friendships.

In summary, this study provides important insight into the nature of friendship in adolescents who experienced severe psychosocial deprivation in early life, and consequently missed out on some of the most critical early social bonds for the development of interpersonal skills. Our comprehensive examination of friendships and early attachment increases our understanding of the impact of institutionalization and foster care in remediating some of the negative effects of early deprivation on social development into adolescence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank the participants and families for supporting this research. We also thank Diana Serban and Cristina Serban for coding the videos. This research was supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Binder Family Foundation, the Jacobs Foundation, and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH091363) to CA Nelson and the Palix Foundation to CH Zeanah.

References

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, & Waters E (1978). wall, S (1978)Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation. Hillsdale, Lawlence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Almas AN, Degnan KA, Radulescu A, Nelson CA, Zeanah CH, & Fox NA (2012). Effects of early intervention and the moderating effects of brain activity on institutionalized children’s social skills at age 8. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109, 17228–17231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121256109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almas AN, Degnan KA, Walker OL, Radulescu A, Nelson CA, Zeanah CH, & Fox NA (2015). The effects of early institutionalization and foster care intervention on children’s social behaviors at the age of eight. Social Development, 24, 225–239. doi: 10.1111/sode.12089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher SR, & Paquette JA (2003). Loneliness and peer relations in childhood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 75–78. 10.1111/1467-8721.01233 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Cassidy J, & Appleyard K (2008). The influence of early attachments on other relationships. In Cassidy J & Shaver PR (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (p. 333–347). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard K, Dozier M, Bick J, Lewis-Morrarty E, Lindhiem O, & Carlson E (2012). Enhancing attachment organization among maltreated children: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Child development, 83, 623–636. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06166.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ, & Kupersmidt JB (1998). Peer relationships and self-esteem among children who have been maltreated. Child development, 69, 1171–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J (1982). Attachment and loss: retrospect and prospect. American journal of Orthopsychiatry, 52, 664–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce J, Tarullo AR, & Gunnar MR (2009). Disinhibited social behavior among internationally adopted children. Development and psychopathology, 21, 157–171. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, Newcomb AF, & Hartup WW (1998). The company they keep: Friendships in childhood and adolescence: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Marvin RS, & Group t. M. W. (1992). Attachment organization in preschool children: Procedures and coding manual. Unpublished manuscript, University of Virginia, 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm K (1998). A three year follow-up of attachment and indiscriminate friendliness in children adopted from Romanian orphanages. Child development, 69, 1092–1106. 10.2307/1132364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, & Toth SL (2006). Fostering secure attachment in infants in maltreating families through preventive interventions. Development and psychopathology, 18, 623–649. doi: 10.1017/s0954579406060329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criss MM, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA, & Lapp AL (2002). Family adversity, positive peer relationships, and children’s externalizing behavior: A longitudinal perspective on risk and resilience. Child development, 73, 1220–1237. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePasquale CE, & Gunnar MR (2020). Affective attunement in peer dyads containing children adopted from institutions. Developmental psychobiology, 62, 202–211. 10.1002/dev.21890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund MM, Kuo SI-C, Puig J, & Collins WA (2011). Early roots of adult competence: The significance of close relationships from infancy to early adulthood. International journal of behavioral development, 35, 490–496. doi: 10.1177/0165025411422994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erol N, Simsek Z, & Münir K (2010). Mental health of adolescents reared in institutional care in Turkey: challenges and hope in the twenty-first century. European child & adolescent psychiatry, 19, 113–124. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, & Kim HK (2007). Intervention effects on foster preschoolers’ attachment-related behaviors from a randomized trial. Prevention Science, 8, 161–170. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0066-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NA, Almas AN, Degnan KA, Nelson CA, & Zeanah CH (2011). The effects of severe psychosocial deprivation and foster care intervention on cognitive development at 8 years of age: findings from the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 919–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02355.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, & Davis KE (1997). Attachment formation and transfer in young adults’ close friendships and romantic relationships. Personal relationships, 4, 131–144. 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1997.tb00135.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Roisman GI, Booth-LaForce C, Owen MT, & Holland AS (2013). Interpersonal and genetic origins of adult attachment styles: A longitudinal study from infancy to early adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 817–838. doi: 10.1037/a0031435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, & Buhrmester D (2009). Methods and measures: The network of relationships inventory: Behavioral systems version. International journal of behavioral development, 33, 470–478. doi: 10.1177/0165025409342634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Stephenson JC, & Rhoades GK (2014). Positive interactions and avoidant and anxious representations in relationships with parents, friends, and romantic partners. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24, 615–629. doi: 10.1111/jora.12052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, & Elliott SN (1990). Social skills rating system: Manual: American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Groh AM, Fearon RP, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van IJzendoorn MH, Steele RD, & Roisman GI (2014). The significance of attachment security for children’s social competence with peers: A meta-analytic study. Attachment & Human Development, 16, 103–136. doi: 10.1080/14616734.2014.883636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh AM, Narayan AJ, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Roisman GI, Vaughn BE, Fearon RP, & van IJzendoorn MH (2017). Attachment and temperament in the early life course: A meta-analytic review. Child development, 88, 770–795. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyon-Harris KL, Humphreys KL, Fox NA, Nelson CA, & Zeanah CH (2018). Course of disinhibited social engagement disorder from early childhood to early adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57, 329–335. e322. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakulinen C, Pulkki-Råback L, Jokela M, Ferrie JE, Aalto A-M, Virtanen M, … Elovainio M (2016). Structural and functional aspects of social support as predictors of mental and physical health trajectories: Whitehall II cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health, 70, 710–715. DOI: 10.1136/jech-2015-206165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartup WW, & Stevens N (1997). Friendships and adaptation in the life course. Psychological bulletin, 121, 355–370. 10.1037/0033-2909.121.3.355 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawk BN, & McCall RB (2014). Perceived relationship quality in adolescents following early social-emotional deprivation. Clinical child psychology and psychiatry, 19, 439–459. doi: 10.1177/1359104513489978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges J, & Tizard B (1989). Social and family relationships of ex-institutional adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 30, 77–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn T, Hornik K, Van De Wiel MA, & Zeileis A (2008). Implementing a class of permutation pests: the coin package. Journal of Statistical Software, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM (2000). Distinguishing mean and structural sex differences in adolescent friendship quality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 17, 223–243. 10.1177/0265407500172004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laninga-Wijnen L, Gremmen MC, Dijkstra JK, Veenstra R, Vollebergh WA, & Harakeh Z (2019). The role of academic status norms in friendship selection and influence processes related to academic achievement. Developmental Psychology, 55, 337–350. DOI: 10.1037/dev0000611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Criss MM, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, & Bates JE (2003). Friendship quality, peer group affiliation, and peer antisocial behavior as moderators of the link between negative parenting and adolescent externalizing behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13, 161–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, & Sheets V (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological methods, 7, 83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson AB, & Nagle RJ (2005). Parent and peer attachment in late childhood and early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 25, 223–249. 10.1177/0272431604274174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Bredenkamp D, Rutter M, English, & Team RAS (1999). Attachment disturbances and disorders in children exposed to early severe deprivation. Infant Mental Health Journal, 20, 10–29. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor TG, Marvin RS, Rutter M, Olrick JT, Britner PA, English, & Team RAS (2003). Child–parent attachment following early institutional deprivation. Development and psychopathology, 15, 19–38. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallini S, Baiocco R, Schneider BH, Madigan S, & Atkinson L (2014). Early child–parent attachment and peer relations: A meta-analysis of recent research. Journal of Family Psychology, 28, 118–123. doi: 10.1037/a0035736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paniagua C, Moreno C, Rivera F, & Ramos P (2019). The sources of support and their relation on the global health of adopted and non-adopted adolescents. Children and Youth Services Review, 98, 228–237. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.01.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, & Asher SR (1993). Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology, 29, 611–621. 10.1037/0012-1649.29.4.611 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pitula CE, Thomas KM, Armstrong JM, Essex MJ, Crick NR, & Gunnar MR (2014). Peer victimization and internalizing symptoms among post-institutionalized, internationally adopted youth. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 42, 1069–1076. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9855-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raaska H, Lapinleimu H, Sinkkonen J, Salmivalli C, Matomäki J, Mäkipää S, & Elovainio M (2012). Experiences of school bullying among internationally adopted children: results from the Finnish Adoption (FINADO) study. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 43, 592–611. 10.1007/s10578-012-0286-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, & Rudolph KD (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological bulletin, 132, 98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Dwyer KM, Booth-LaForce C, Kim AH, Burgess KB, & Rose-Krasnor L (2004). Attachment, friendship, and psychosocial functioning in early adolescence. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 24, 326–356. doi: 10.1177/0272431604268530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Wojslawowicz JC, Rose-Krasnor L, Booth-LaForce C, & Burgess KB (2006). The best friendships of shy/withdrawn children: Prevalence, stability, and relationship quality. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 34, 139–153. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-9017-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman S, Elicker J, & Sroufe LA (1994). Stages of friendship growth in preadolescence as related to attachment history. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11, 341–361. 10.1177/0265407594113002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smyke AT, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Nelson CA, & Guthrie D (2010). Placement in foster care enhances quality of attachment among young institutionalized children. Child development, 81, 212–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01390.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke EJ, Schlotz W, & Kreppner J (2010). V. Differentiating developmental trajectories for conduct, emotion, and peer problems following early deprivation. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 75, 102–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2010.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Egeland B, Carlson E, & Collins WA (2005). Placing early attachment experiences in developmental context. Attachment from infancy to adulthood: The major longitudinal studies, 48–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan HS (2013). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tizard B, & Hodges J (1978). The effect of early institutional rearing on the development of eight year old children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 19, 99–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1978.tb00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tizard B, & Rees J (1975). The effect of early institutional rearing on the behaviour problems and affectional relationships of four-year-old children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 16, 61–73. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1975.tb01872.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Harmelen A-L, Gibson JL, St Clair MC, Owens M, Brodbeck J, Dunn V, … Kievit RA (2016). Friendships and family support reduce subsequent depressive symptoms in at-risk adolescents. PLoS One, 11, e0153715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van IJzendoorn MH (1990). Developments in cross-cultural research on attachment: Some methodological notes. Human Development, 33, 3–9. DOI: 10.1159/000276498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F, Boivin M, & Bukowski WM (2009). The role of friendship in child and adolescent psychosocial development. [Google Scholar]

- Vorria P, Ntouma M, & Rutter M (2014). The behaviour of adopted adolescents who spent their infancy in residential group care: the Greek Metera study. Adoption & Fostering, 38, 271–283. 10.1177/0308575914543237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vorria P, Papaligoura Z, Dunn J, Van IJzendoorn MH, Steele H, Kontopoulou A, & Sarafidou Y (2003). Early experiences and attachment relationships of Greek infants raised in residential group care. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 1208–1220. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldrip AM, Malcolm KT, & Jensen-Campbell LA (2008). With a little help from your friends: The importance of high-quality friendships on early adolescent adjustment. Social Development, 17, 832–852. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00476.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weinfield NS, Ogawa JR, & Sroufe LA (1997). Early attachment as a pathway to adolescent peer competence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 7, 241–265. 10.1207/s15327795jra0703_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams PE, Weiss PDLG, & Rolfhus PDE (2003). WISC–IV Technical Report# 1 Theoretical Model and Test Blueprint. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah CH, Smyke AT, Koga SF, Carlson E, & Group BEIPC (2005). Attachment in institutionalized and community children in Romania. Child development, 76, 1015–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.