Significance

Chloroplast biogenesis is a fundamental process occurring during seedling ontogenesis and leading to plant autotrophy. Which membrane components sterically organize the light-triggered transition of etioplast prolamellar bodies (PLBs) into chloroplast thylakoids, and thus mediate cubic–lamellar transformation, is poorly understood. Here, we used combined two- and three-dimensional electron microscopy, spectroscopy, and biochemical methods to determine the role of CURT1 proteins in the formation of etioplast cubic membranes and their transformation to photosynthetically active chloroplast thylakoids. CURT1 proteins were previously recognized as significant contributors to thylakoid membrane folding. We found that CURT1 proteins are integral proteins of etioplast membranes and act as factors modulating PLBs and prothylakoid nanomorphology. They are also required for concerted thylakoid maturation under de-etiolation.

Keywords: CURT1, de-etiolation, prolamellar bodies, chloroplast biogenesis, photosynthesis

Abstract

The term “de-etiolation” refers to the light-dependent differentiation of etioplasts to chloroplasts in angiosperms. The underlying process involves reorganization of prolamellar bodies (PLBs) and prothylakoids into thylakoids, with concurrent changes in protein, lipid, and pigment composition, which together lead to the assembly of active photosynthetic complexes. Despite the highly conserved structure of PLBs among land plants, the processes that mediate PLB maintenance and their disassembly during de-etiolation are poorly understood. Among chloroplast thylakoid membrane–localized proteins, to date, only Curvature thylakoid 1 (CURT1) proteins were shown to exhibit intrinsic membrane-bending capacity. Here, we show that CURT1 proteins, which play a critical role in grana margin architecture and thylakoid plasticity, also participate in de-etiolation and modulate PLB geometry and density. Lack of CURT1 proteins severely perturbs PLB organization and vesicle fusion, leading to reduced accumulation of the light-dependent enzyme protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (LPOR) and a delay in the onset of photosynthesis. In contrast, overexpression of CURT1A induces excessive bending of PLB membranes, which upon illumination show retarded disassembly and concomitant overaccumulation of LPOR, though without affecting greening or the establishment of photosynthesis. We conclude that CURT1 proteins contribute to the maintenance of the paracrystalline PLB morphology and are necessary for efficient and organized thylakoid membrane maturation during de-etiolation.

The transition from etioplast to chloroplast is a highly dynamic process involving changes in membrane structure accompanied by reprogramming of nuclear and plastid gene expression as well as metabolism (1–3). Etioplasts contain an internal network of paracrystalline membranes known as prolamellar bodies (PLBs), from which porous prothylakoid (PT) membranes protrude (4). Recent studies using advanced electron tomography (ET) have elucidated the structural rearrangements in PLBs and PTs during de-etiolation (5). These investigations have shown that upon illumination, the regularity of the paracrystalline network of PLBs progressively declines, while PTs elongate from the margins of PLBs, forming parallel rows oriented along one axis of the etio-chloroplast. Over time, PTs undergo further morphological changes, which transform porous and discontinuous membranes into flat, layered lamellae—the first grana stacks (5). During this process, the protein and pigment content of the PTs changes drastically. Etioplasts contain not only high concentrations of ATPase precomplexes, ferredoxin-NADP+ oxidoreductase, and FtsH and Clp proteases (6) but also several glycolytic enzymes, including enolase and phosphoglyceromutase, and phosphoenolpyruvate translocators (7). Moreover, the PLBs in etioplasts accumulate copious amounts of the light-dependent enzyme NADPH:protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase (LPOR) and the precursor pigment protochlorophyllide (Pchlide), which together form a photoactivatable complex (1, 4, 6, 8). Upon illumination, LPOR-containing complexes drive the conversion of Pchlide to chlorophyllide and rapidly disintegrate, with the concomitant degradation of LPOR. The subsequent conversion of chlorophyllide into chlorophyll by downstream tetrapyrrole pathway enzymes is accompanied by the synthesis of chlorophyll-binding proteins, such as the light-harvesting complexes (LHCs) and PSI and PSII core proteins (4, 9, 10), and leads to the de novo assembly and organization of photosynthetic complexes in the thylakoid membranes (1, 11–13).

Various mutants that are defective in thylakoid development have been characterized. The genes affected code for assembly factors (e.g., sco2 and hcf222) (14, 15), enzymes of lipid biosynthesis (mgd1 and dgd1) (16, 17), and transcription factors (including the ABI4-HY5 cascade and OR-TCP14) (18, 19) among other functions. Their phenotypes range from mild defects in thylakoid biogenesis (i.e., mutants of the OR-TCP14 pathway) to severe effects in PLB and PT ultrastructure or plant death (e.g., lipid mutants). Indeed, only the use of DEX-inducible amiRNA-dgd1 and amir-RNA-mdg1 lines made it possible to explore the roles of monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) synthetase 1 (MGD1) and diacylgalactosyldiacylglycerol synthase 1 (DGD1), respectively, in lipid bilayer formation during thylakoid biogenesis (20). These studies have contributed significantly to our understanding of PLB biogenesis, especially the morphological impact of lipids, pigments, and photosynthesis-related proteins on this process. However, the components that mediate the morphological transformation of PLBs remain elusive, although the available evidence argues for participation of membrane-bending proteins (5).

Curvature Thylakoid 1 (CURT1) proteins are major contributors to the shaping of chloroplast thylakoid membranes (21). In Arabidopsis thaliana, they comprise a family of four thylakoid membrane-anchored proteins—named CURT1A to D—with molecular weights ranging between 11 and 15 kDa. CURT1A, the major isoform, induces thylakoid bending both in vitro and in planta (21). In the A. thaliana curt1abcd quadruple mutant (lacking all four CURT1 proteins), the grana diameter is increased, while the efficiency of light acclimation mechanisms such as state transitions and the PSII repair cycle (22) is impaired. The former effect can be expected to diminish the efficiency of plastocyanin-mediated electron transport (due to the longer distance covered by diffusion), which can in turn account for the latter phenotype (23). The cyanobacterial ortholog of CURT1A, synCurT, has been postulated to play a role in both thylakoid morphology and thylakoid biogenesis (24), raising questions regarding the possible role of CURT1 proteins during thylakoid biogenesis in land plants. In the present work, we explore the impact of CURT1 proteins on PLB structure and membrane reorganization during the formation of a functional photosynthetic apparatus upon induction of de-etiolation in A. thaliana seedlings.

Results

CURT1s Are Membrane-Integral Etioplast Proteins that Affect Chlorophyll Accumulation during De-etiolation.

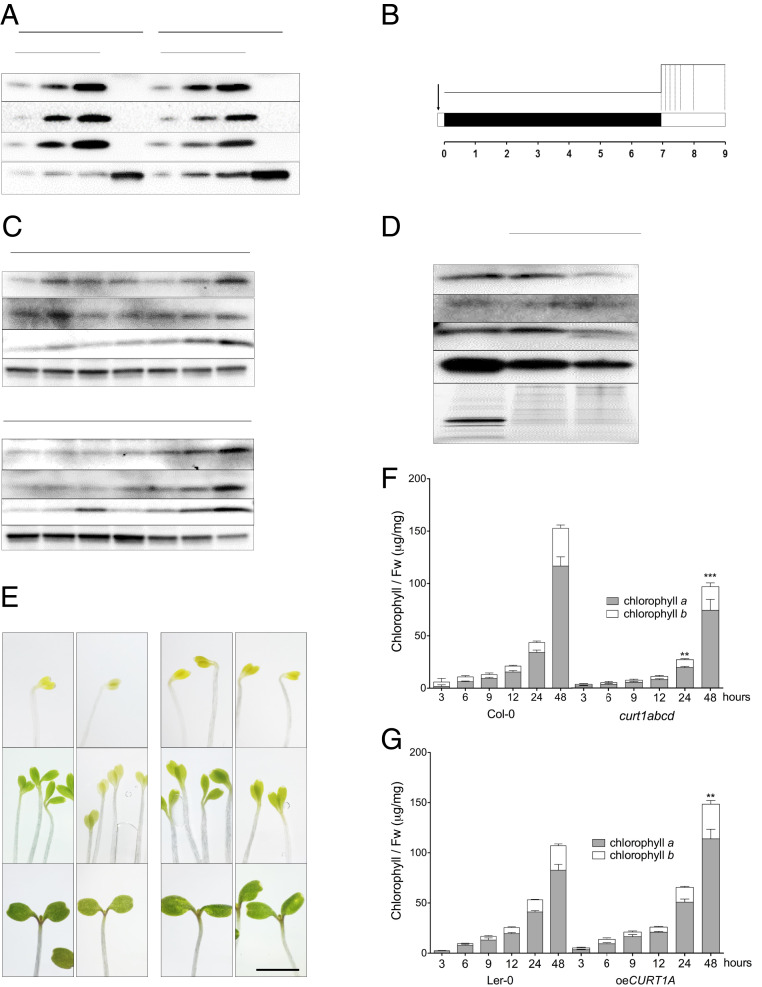

To determine CURT1 protein profiles in seedlings, total protein extracts obtained from cotyledons and roots of 7-d-old seedlings were analyzed by immunoblotting (Fig. 1A). CURT1 proteins (CURT1A-C) were detected only in cotyledons but not in roots of the wild-type (WT) A. thaliana ecotypes Columbia-0 (Col-0) and Landsberg erecta-0 (Ler-0) (Fig. 1A). In agreement with previous studies (21), CURT1D was undetectable by immunoblotting. As CURT1 proteins were only detectable in cotyledons, we followed their accumulation during de-etiolation in more detail (Fig. 1B). We detected similar levels of CURT1A, B, and C in total protein fractions of etiolated and de-etiolated seedlings throughout the first 24 h of de-etiolation. Only after 48 h of illumination, an increase in CURT1 amounts was observed which correlated with the appearance of leaves primordial (Fig. 1C). We further detected CURT1 protein accumulation in membrane fractions of de-etiolated seedlings after 6 h of illumination (Fig. 1D). The presence of CURT1A and LPOR in the same membrane fraction after 15 min of illumination (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), together with the concomitant decrease of LPOR after 6 h and 48 h of de-etiolation (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B), implies that CURT1 proteins are membrane localized within the etioplast.

Fig. 1.

CURT1 proteins are present in membrane fractions of cotyledons throughout de-etiolation. (A) Accumulation of CURT1A-C proteins in cotyledons and roots of 7-d-old Col-0 and Ler-0 seedlings grown under a 16/8 h light/dark cycle. ACTIN was used as the loading control. (B) Design of the de-etiolation assay. Seeds were stratified for 2 to 3 d and exposed to light for 1 h prior to dark acclimation for 1 wk. Seedlings were sampled at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, and 48 h after the onset of continuous light (dotted lines). (C) Immunoblotting analysis of CURT1A-C accumulation in total protein extracts from seedlings sampled at the times shown in B; 10 μg of protein was loaded in each lane. n = 3. (D) Membrane fractions (M. fractions) were prepared from cotyledons after 6 h of illumination. The accumulation of CURT1A-C proteins in mature thylakoids (T) and membrane fractions was analyzed in Col-0 and Ler-0. AtpB, a typical integral membrane protein, served as the loading control. n = 3. (E) Images of emerging cotyledons from Col-0, curt1abcd, Ler-0, and oeCURT1A at 0, 12, and 48 h after the onset of illumination. (Scale bar, 5 mm.) (F and G) Total chlorophyll content analyzed in (F) Col-0, curt1abcd, and (G) Ler-0 and oeCURT1A after 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, and 48 h of de-etiolation. The contributions of chlorophyll a (black columns) and chlorophyll b (white columns) to the total chlorophyll content are depicted. Error bars represent SDs of six biological replicates. Levels at 48 h were compared (by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest) between curt1abcd and Col-0 and between oeCURT1A and Ler-0. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

For an extensive study of the roles of CURT1 proteins during greening, we made use of two previously characterized A. thaliana mutant lines: curt1abcd, which is devoid of all four CURT1 isoforms in the Col-0 background, and oeCURT1A, a CURT1A::c-Myc–tagged overexpressor line in the Ler-0 background which accumulates around 2.3 times more CURT1A protein in mature plants than the respective WT (21, 22). Both of these lines and their corresponding WT controls were subjected to the de-etiolation protocol (Fig. 1B). We observed that CURT1A accumulated around 30-fold in oeCURT1A compared to Ler-0 in etiolated tissue and that CURT1A levels altered only marginally during de-etiolation (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 C and D). In addition, we observed a delay in the greening of curt1abcd seedlings (relative to Col-0) at 12 h postillumination (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Fig. S2), consistent with reduced contents of total chlorophyll after 24 and 48 h of illumination (Fig. 1F). Although no notable differences in greening were observed between oeCURT1A and Ler-0 (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Fig. S2), a clear increase in total chlorophyll content in oeCURT1A compared to Ler-0 was detected after 48 h of illumination (Fig. 1F). Together, our results show that CURT1A, B, and C are membrane-associated proteins present in etio-chloroplasts and have an impact on chlorophyll accumulation during de-etiolation.

CURT1A-Mediated Changes in LPOR Degradation and Accumulation of Photosynthetic Proteins Correlate with the Modifications in PLB and PT Structures.

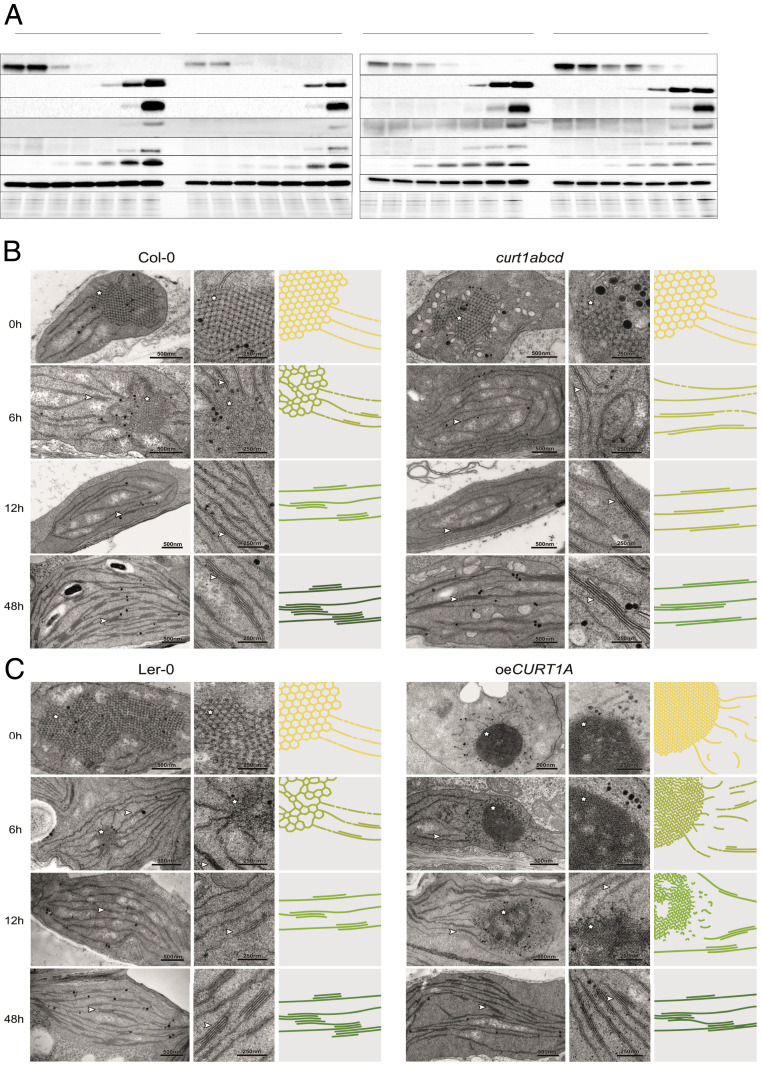

To unravel the function of CURT1 proteins in the development of the photosynthetic apparatus during de-etiolation, we analyzed the accumulation of photosynthesis-related proteins in total protein extracts from seedlings of all four genotypes at different stages of de-etiolation. We observed that in curt1abcd, LPOR was present in lower amounts in etiolated seedlings, while it was more abundant in oeCURT1A, relative to the WT controls (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, the degradation of LPOR appeared to be delayed in oeCURT1A, while it was accelerated in curt1abcd (Fig. 2A). In agreement with previous studies (4), all four genotypes exhibited a rapid decline in LPOR transcript accumulation upon illumination. Lower LPOR messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) levels were observed in etiolated seedlings of curt1abcd (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), which partially explains the lower protein content observed in etiolated tissue but not the faster degradation of LPOR proteins. In contrast, LPOR transcript levels in oeCURT1A behaved similarly to those in Ler-0 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), suggesting that protein degradation rather than LPOR transcription or mRNA stability is altered in oeCURT1A.

Fig. 2.

Protein profiles are affected by structural changes in PLBs and PTs in curt1abcd and oeCURT1A. (A) Protein profiles of 7-d-old seedlings were determined at 0 to 48 h of de-etiolation in the curt1abcd mutant and the corresponding WT Col-0 (Left) and in the oeCURT1A line and its respective WT control (Ler-0; Right). At each time point, 10-µg aliquots of total protein were fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and subjected to immunoblot analysis (n = 3). (B and C) Transmission electron micrographs of chloroplasts from (B) Col-0 and curt1abcd and (C) Ler-0 and oeCURT1A after 0, 6, 12, and 48 h of illumination (Left and Middle). Schematic depictions of the respective membrane morphologies (scaled by average PLB size and compactness, grana sizes, and grana thylakoid interconnectivity) are presented (Right). Note that for clarity, the PLB network is magnified threefold relative to the size of grana stacks (membrane thickness is fixed), and the color schemes depict relative levels of chlorophyll accumulating in the respective genotypes. Stars and arrowheads indicate PLBs and stacked membranes, respectively. (Scale bars, 500 nm [Left, TEM] and 250 nm [Middle, TEM magnification].)

In curt1abcd, we observed a delay in the accumulation of PSII and PSI core proteins, including D1 (PsbA), D2 (PsbD), CP43 (PsbC), and PsaB. Their levels remain lower than in Col-0 throughout the course of de-etiolation (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). While psbA transcript levels were lower in curt1abcd (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), no differences in psaA transcripts were observed between curt1abcd and Col-0 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). In contrast, no notable differences in PsaB, D1, or D2 protein concentrations were detectable between oeCURT1A and Ler-0, in agreement with the psaA and psbA transcript levels in both genotypes (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Notably, the amounts of CP43 were lower in oeCURT1A (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Although a decrease in LHCA1 transcripts was observed in curt1abcd after 24 h of illumination (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), levels of the Lhca1 protein were not notably affected (Fig. 2A). Amounts of both the PSII antenna protein Lhcb2 and its mRNA were altered in curt1abcd relative to Col-0 (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). In oeCURT1A, levels of Lhca1 exceeded those in Ler-0, while Lhcb2 amounts were lower (Fig. 2A). Consistent with previous studies (1, 6), no major changes in the accumulation of AtpB, RbcL, or PetA (cytochrome f) were detected in curt1abcd or oeCURT1A (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

The delayed greening in curt1abcd together with the altered transcript and protein profiles observed in both curt1abcd and oeCURT1A prompted us to study the course of membrane reorganization during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation in these lines using transmission electron microscopy (TEM; Fig. 2 B and C and SI Appendix, Figs. S5–S7). We observed that the disassembly of PLBs proceeded faster in curt1abcd than in Col-0 and was completed within the first 6 h after induction of de-etiolation (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). In contrast, PLB structures persisted for longer in oeCURT1A than in Ler-0 and were still visible after 24 h of illumination (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S6). The PT structures were also altered in oeCURT1A, exhibiting either discontinuous or tubular patterns visible in TEM cross-sections (from 0 to 9 h into the de-etiolation process) (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Given the intrinsic membrane-bending capacity of CURT1A (and other CurT proteins) previously observed in in vitro experiments (21, 24), we speculate that CURT1A provokes distortions within PTs that lead to discontinuity of PTs within the focal plane. However, regular grana-like pairing of folded single PT membranes also occurs in oeCURT1A, as shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S7. In addition, etioplasts of curt1abcd mutants showed loosely packed vesicle-like structures around the PLBs (Fig. 2B). These vesicle-like structures were in close proximity to the stroma-exposed PLB domains (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 A and B). We did not observe these structures in curt1abcd or in any other genotype between 3 and 24 h into the de-etiolation process. Only after 48 h of illumination, we again observed accumulation of vesicles in curt1abcd (Fig. 2). Higher-resolution images showed that similar to the observations in etiolated tissue, the vesicle-like structures were in close proximity to the membranes and exclusively in nonappressed areas near the grana stacks (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 C and D).

Immunogold electron microscopy confirmed the enrichment of CURT1A within the PLBs and PTs of Col-0, Ler-0, and oeCURT1A in etiolated samples (SI Appendix, Fig. S9A) and in etio-chloroplasts after 12 h of illumination (SI Appendix, Fig. S9B). This observation was confirmed by immunogold detection of the c-Myc-tagged version of CURT1A expressed in oeCURT1A (SI Appendix, Fig. S9 A and B). Notably, a marked enrichment of gold nanoparticles, indicative of the presence of CURT1A, was observed in PLBs of etio-chloroplasts of oeCURT1A after 12 h of illumination (SI Appendix, Fig. S8B).

PLBs Acquire an Unusual Morphology upon Excessive Accumulation of CURT1A.

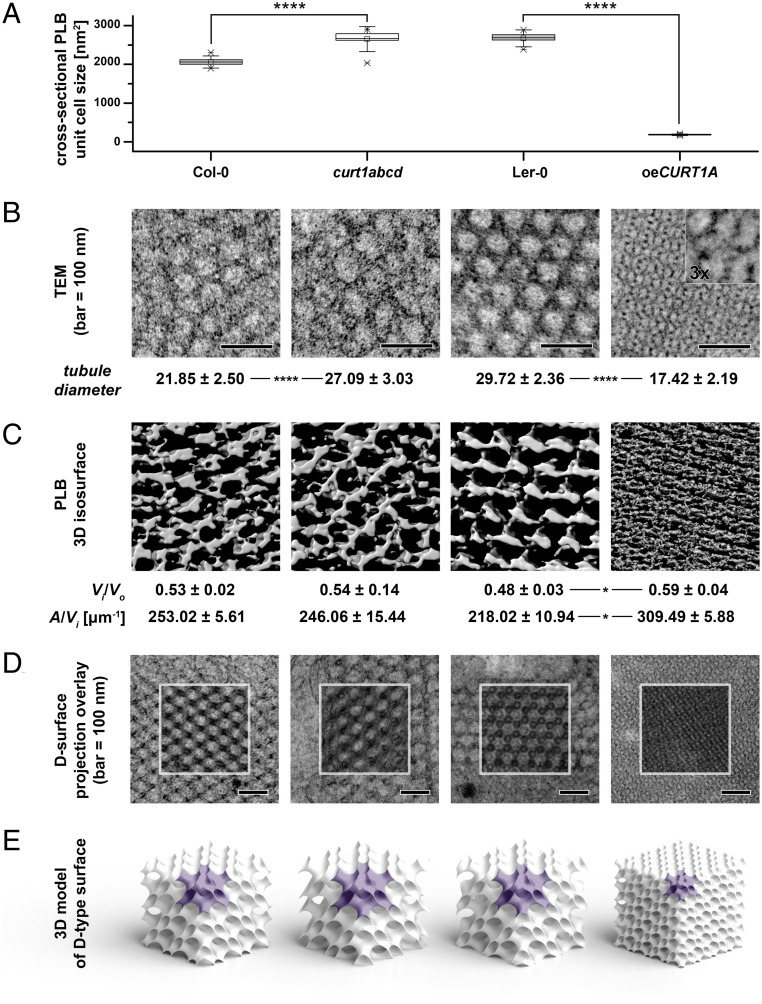

The pronounced and contrasting differences in PLB morphology between curt1abcd and oeCURT1A prompted us to characterize the PLB structure in more detail. We noted that the cross-sectional areas of the PLB unit cells in curt1abcd and oeCURT1A differed significantly from those of the respective WTs. The mean cross-sectional PLB unit cell area in curt1abcd was 1.3 times higher than in Col-0 (2,654 ± 105 nm2 and 2,060 ± 215 nm2, respectively), whereas oeCURT1A showed a 15-fold reduction in comparison to Ler-0 (183 ± 13 nm2 and 2,672 ± 145 nm2, respectively; Fig. 3A). In addition, we observed a higher PLB tubule diameter in curt1abcd (27.09 ± 3.03 nm) in comparison to Col-0 (21.85 ± 2.5 nm; Fig. 3B). In contrast, the tubule diameter was strongly reduced in oeCURT1A (17.42 ± 2.19 nm) in comparison to the corresponding WT Ler-0 (29.72 ± 2.36 nm; Fig. 3B). To obtain more detailed information on PLB geometry, we analyzed etiolated cotyledons from Col-0, Ler-0, curt1abcd, and oeCURT1A seedlings by ET (Fig. 3C). Using a surface projection, image recognition method that enables matching of TEM images with computed projections of bicontinuous phases (25), we found that the PLB lattice in all examined genotypes adopts a cubic membrane organization of a diamond type (D-type; Fig. 3 D and E). Significant differences between TEM images of the oeCURT1A PLB network and those of the other examined plants are therefore mostly related to a decreased size of the PLB unit cell in this genotype (Fig. 3 A and E—unit cell marked in purple). Moreover, we analyzed the spatial parameters of the PLB network inner-to-outer volume ratio (Vi/Vo) and the area-to-volume ratio (A/Vi) parameters (26) based on reconstructed three-dimensional (3D) tomograms. We observed an increase in the Vi/Vo of the paracrystalline structure in oeCURT1A plants, indicating significant changes in the balance between inner and outer aqueous channels of the PLB (Fig. 3C). In addition, we observed a higher A/Vi in oeCURT1A, which indicates increased PLB compactness calculated from actual 3D visualization of the periodic surface. The higher the A/Vi value, the more compact are PLBs (i.e., more membranes are present in a given volume; Fig. 3C). We also assessed the PLB morphology of a curt1a mutant in the Ler-0 background, an ecotype which is characterized by a larger unit cell size than Col-0 (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 A–F). This analysis revealed significant disturbances of PLB formation in etioplasts of curt1a plants. PLBs were fragmented and exhibited local irregularities, indicating the unstable nature of these structures at the level of both whole PLBs and particular unit cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 A–C). Measurements of the cross-sectional PLB unit cell size for recognized D-type surfaces showed a significant increase in the values registered for curt1a compared to Ler-0 (SI Appendix, Fig. S10 D–F). Moreover, we observed faster LPOR degradation and increased accumulation of Lhcb2 and AtpB in curt1a compared to Ler-0 (SI Appendix, Fig. S10G), which reflected in delayed greening (SI Appendix, Fig. S10H), similar to the observation made between Col-0 and curt1abcd.

Fig. 3.

Packing and morphology of PLBs is altered by either lack or excess of CURT1 proteins. (A) Mean cross-sectional areas of the unit cells of paracrystalline PLB lattices calculated from transmission electron micrographs of Col-0, curt1abcd, Ler-0, and oeCURT1A. Error bars represent the SD. Col-0 was compared with curt1abcd and Ler-0 with oeCURT1A by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni posttest; ****P < 0.001. (B) Sections obtained from Col-0, curt1abcd, Ler-0, and oeCURT1A and examined by TEM. The tubule diameters for Col-0, curt1abcd, Ler-0, and oeCURT1A are indicated below each image. (C) 3D isosurface reconstructions of TEM sections from Col-0, curt1abcd, Ler-0, and oeCURT1A. The spatial PLB parameters of inner-to-outer volume ratio (Vi/Vo), and area-to-inner volume ratio (A/Vi) were calculated based on PLB 3D isosurface reconstructions of electron tomographs of PLBs from Col-0, curt1abcd, Ler-0, and oeCURT1A. (D) Electron micrographs of PLB lattices and computed projections of D-type surfaces obtained with the SPIRE tool; regions marked with white squares show a superposition of computed projections and TEM images using multiply blend mode. (E) 3D spatial models of cubic D-type PLB grids generated based on parameters obtained with the SPIRE tool. Single PLB unit cells are marked with purple, and all models are shown to scale, representing actual differences between unit cell sizes and volume proportion of the PLB network in particular genotypes (n = 3 for tomograms and reconstructions).

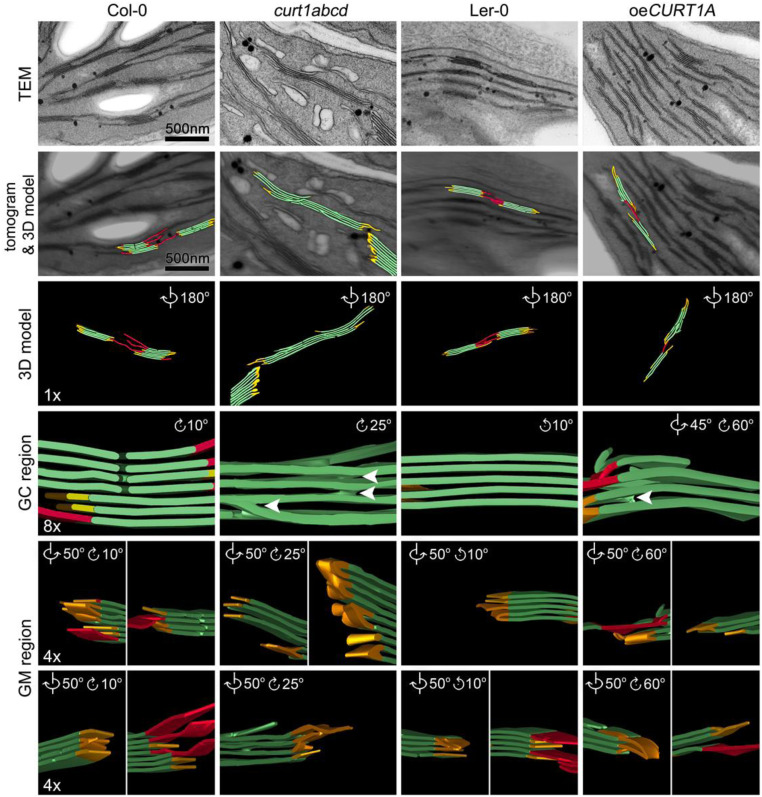

Despite these differences in PLB structure, all four tested genotypes (Col-0, Ler-0, curt1abcd, and oeCURT1A) exhibited grana stacking after 6 h of de-etiolation (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Next, we measured grana diameter and grana height after 6, 12, 24, and 48 h of illumination (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). In agreement with previous studies (5), grana height and grana diameter increased over time in both Col-0 and Ler-0. From the onset of grana formation, grana diameters in curt1abcd exceeded those in Col-0, without displaying much plasticity during thylakoid maturation (SI Appendix, Fig. S11A). In contrast, oeCURT1A showed a reduction in grana diameter compared to Ler-0, which was exacerbated upon illumination (SI Appendix, Fig. S11B). No striking differences in grana height were observed between Col-0 and curt1abcd or in Ler-0 versus oeCURT1A. To investigate whether the alterations in grana diameter observed in curt1abcd and oeCURT1A correlate with changes in 3D grana structure, we used ET to explore the changes in thylakoid spatial morphology after 48 h of de-etiolation (Fig. 4). Col-0, Ler-0, and oeCURT1A displayed a similar spatial distribution of thylakoid membrane structures (5), with well-defined grana core and margin areas, while curt1abcd showed perforated grana with numerous instances of local splitting of grana. Additionally, curt1abcd lacks the typical extended stroma thylakoids that normally connect neighboring grana stacks and exhibits accumulation of several vesicle-like structures. After 48 h, WT grana exhibited small membrane stacks with local membrane staggering, indicating the initiation of the typical helical arrangement of grana (27) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Electron tomographic reconstruction of thylakoid membranes after 48 h of illumination electron tomographic reconstructions of thylakoid membranes in Col-0 (Left), curt1abcd (Middle Left), Ler-0 (Middle Right), and oeCURT1A (Right) lines based on TEM sections. Each column shows (from Top to Bottom) the central section of the TEM stack (TEM), a surface model (colored in red for stroma thylakoids, green for grana thylakoids, and yellow for grana margins) superimposed on the reconstructed tomogram, a surface visualization shown in reversed view (3D model), and magnified and rotated views of the grana core (GC region) and grana margins (GM region). White arrowheads indicate the dichotomous splitting of the membranes observed in curt1abcd and oeCURT1A sections. Scale bars and magnifications are the same for all genotypes in each row.

Onset of Photosynthesis and PS Complex Assembly Are Markedly Delayed in curt1abcd.

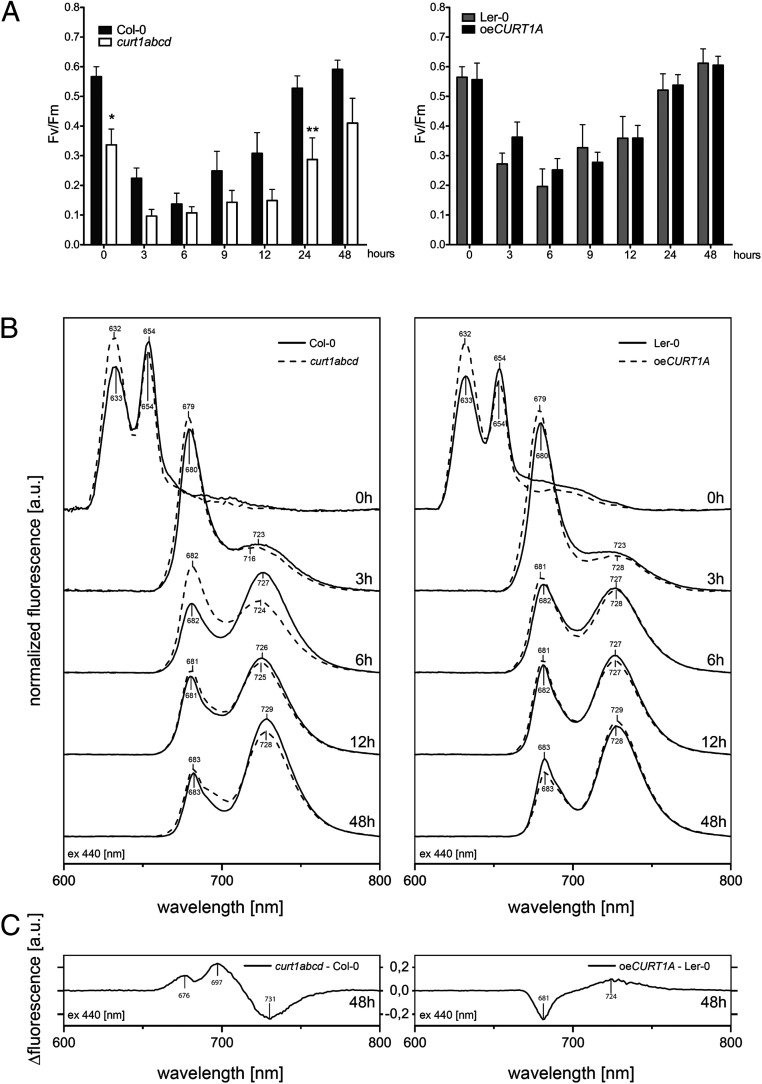

To analyze the influence of both altered thylakoid biogenesis and protein accumulation on the onset of photosynthetic activity, we measured light induction curves with the aid of pulse amplitude modulation (PAM) fluorometry. In accordance with previous reports (13), a fluorescence signal was registered in etiolated seedlings of all genotypes, and its intensity decreased during the first 6 h of illumination. In seedlings collected after 6 h of de-etiolation, a chlorophyll fluorescence peak originating from PSII (black arrows, SI Appendix, Fig. S11) was observed in Col-0, Ler-0, and oeCURT1A but appeared only after 9 h of illumination in curt1abcd. Compared to Col-0, etiolated curt1abcd seedlings generally displayed a reduced maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (Fv/Fm) over the course of de-etiolation, whereas oeCURT1A and Ler-0 showed similar Fv/Fm values (Fig. 5A). The initial decline in Fv/Fm values can be ascribed to Pchlide reduction upon illumination and the concomitant accumulation of various intermediates in chlorophyll biosynthesis, while its subsequent rise reflects the increase in chlorophyll levels (Fig. 5A) and the accompanying onset of PSII assembly after 6 h of illumination. After 9 h of illumination, PSII activity had increased more rapidly in Col-0, Ler-0, and oeCURT1A than in curt1abcd. Indeed, PSII function remained limited in curt1abcd throughout the stages of chloroplast biogenesis examined (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

The onset of photosynthesis and the assembly of photosynthetic complexes is markedly delayed in curt1abcd. (A) Comparisons of Fv/Fm values derived from PAM measurements of etiolated Col-0 and curt1abcd (Left) and Ler-0 and oeCURT1A (Right) seedlings after 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, and 48 h of illumination (n = 5; two-way ANOVA, with Bonferroni posttest; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01). (B) Low-temperature (77 K), steady-state fluorescence curves for Col-0 (solid line) and curt1abcd (dashed line) (Left) and Ler-0 (solid line) and oeCURT1A (dashed line) (Right) at the indicated times after induction of de-etiolation. (C) Fluorescence difference spectra (excitation at 440 nm) for the indicated genotypes after 48 h of illumination. Spectra are representative of three independent measurements.

To address the differences in PSII functionality observed in curt1abcd, the assembly of photosystem I and II complexes was analyzed using 77 K fluorescence spectroscopy (Fig. 5 B and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S12). Fluorescence emission spectra of etiolated cotyledons showed two distinct maxima at 632 and 654 nm, which derive from free Pchlide and photoactive Pchlide:LPOR:NADPH complexes, respectively (12). In both Col-0 and Ler-0, the 654-nm peak was higher than the 632-nm peak, while the opposite was observed for curt1abcd and oeCURT1A (Fig. 5B). After 3 h of illumination, these peaks had transitioned into a sharp peak at 679 nm, corresponding to chlorophyll that is not yet associated with photosystems (13), and a second broad peak between 716 and 728 nm in all genotypes examined (Fig. 5B). The two peaks at 723 nm and 716 nm indicate the appearance of PSI core complexes in Col-0 and curt1abcd, respectively (Fig. 5B). Both Col-0 and Ler-0 exhibited the PSI core complex peak at 723 nm (Fig. 5B). However, oeCURT1A exhibited a peak at 728 nm that was previously attributed to assembled PSI-LHCI (13, 28), which is consistent with the earlier appearance of the PSI antenna protein Lhca1 as observed by immunoblotting in oeCURT1A (Fig. 2A).

All genotypes displayed similar and progressive formation of PSII-LHCII complexes, represented by a peak at 680 nm, which first emerged after 6 h of illumination (Fig. 5B). However, in curt1abcd, formation of PSI-LHCI was noticeably delayed, as indicated by the retarded appearance of the shift in peak maximum from 716 to 728 nm. Despite the differences observed in curt1abcd and oeCURT1A at early stages of de-etiolation, chlorophyll emission spectra after 48 h of illumination were qualitatively similar to those observed in mature plants (SI Appendix, Fig. S12A). The difference spectrum curt1abcd versus Col-0 at 48 h featured a higher 697-nm peak on excitation at 470 nm than at 412 nm, which indicates that the higher contribution of the PSII-related peak in this genotype is mainly due to an increased LHCII antenna content (probably in aggregated states) rather than the typical PSII supercomplexes (Fig. 5C and SI Appendix, Fig. S13B). These differences in fluorescence are also consistent with the differences in the accumulation of PSII core proteins and LHCII proteins between curt1abcd and Col-0 detected by immunoblotting (Figs. 2A and 5 B and C). Finally, we explored the possible effects of CURT1A-mediated changes on the dynamics of Pchlide to Chlide conversion using either flash illumination of the samples for 1 ms (FL) or 15 s of dim-light exposition (LL) (SI Appendix, Fig. S14). Such illumination conditions affected mainly the ∼654-nm photoactive Pchlide peak. A lack of this band was seen in flash-illuminated samples, and instead, a new 685-nm peak corresponding to Chlide bound to LPOR-NADP+ was observed. Dim-light illumination (15 s) resulted in reduced intensity of the ∼654-nm band and the presence of a broad 675-nm peak representing Chlide after the Shibata shift. In both illumination conditions, the spectra of curt1abcd seedlings were very similar to the WT, with a lower contribution of the ∼654-nm peak in 15 s LL and the 685-nm peak after 1 ms of FL in the curt1abcd mutant (SI Appendix, Fig. S14 A). These results are consistent with the lower levels of LPOR protein in curt1abcd compared to Col-0 (Fig. 2A). We did not observe any delay in photoactive Pchlide conversion in oeCURT1A in any of the applied light settings in comparison to Ler-0 seedlings (SI Appendix, Fig. S13B). Moreover, an increase in the 675-/685-nm peaks was visible in oeCURT1A compared to Ler-0 (SI Appendix, Fig. S14B), in line with the higher LPOR levels detected in this genotype (Fig. 3A). Taken together, our results demonstrate that CURT1 proteins play a role in the concerted assembly of photosynthetic complexes and the timing of the onset of photosynthesis but do not contribute to LPOR oligomerization.

Discussion

For decades, the formation of PLBs, their disassembly upon illumination, and the latter’s contribution to autotrophic growth have been the subject of many studies in model plants, including rice, wheat, bean, pea, tobacco, and A. thaliana (2, 3, 29, 30). These studies have suggested that the morphology and geometry of PLBs depend on their lipid composition, protein content, and pigment accumulation. Loss of either of the galactolipid biosynthesis-related genes MGD1 and DGD1, which are required for the synthesis of monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) and digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG), respectively, has severe effects on the size and the arrangement of the paracrystalline membranes of PLBs and on PT protrusion, suggesting that the morphology and biogenesis of PLBs depends on the MGDG/DGDG ratio (31). Similarly, accumulation of the LPOR protein has been proposed as a key requirement for PLB formation (32). The absence of PLB structures from the porA mutant negatively affects chloroplast differentiation and plant development, indicating that PORA plays a role in PLB organization and chloroplast differentiation, and its content is also influenced by the MGDG/DGDG ratio (33, 34). Indeed, overexpression of PORA rescues the abnormal PLB morphology observed in the cop1 mutant (in which photomorphogenesis is disrupted) (35), which supports a role for LPOR in PLB formation. Additionally, the carotenoid-related mutant ccr2 lacks PLBs but expresses WT levels of LPOR and has normal Pchlide contents (36). The finding that the loss of PLBs is rescued by additional mutations in the ζ-carotene isomerase (37) argues for a role for carotenoids in PLB biogenesis but not in disassembly upon illumination. It has been proposed that CURT1 proteins could contribute to thylakoid maturation during proplastid-to-chloroplast differentiation (38). Our results reported here demonstrate that CURT1 proteins accumulate in membrane fractions of etioplasts and influence the architecture and packing density of PLBs as well as the arrangement of PTs in etiolated seedlings. Although lower levels of the Pchlide:LPOR:NADPH complex were observed in both etiolated curt1abcd and oeCURT1A seedlings (compared to the WT), in all genotypes, the complex had disappeared after 3 h of illumination. Nevertheless, the accumulation of LPOR, and its subsequent degradation upon light exposure is influenced by the CURT1-mediated alterations in PLB morphology, as reflected in the lower abundance and slightly faster degradation of LPOR in curt1abcd, and its greater abundance and delayed degradation in oeCURT1A (Fig. 6). Our results strongly suggest that the Pchlide:LPOR:NADPH complex is not the only essential component for PLB maintenance, as suggested previously, since it becomes undetectable after 3 h of illumination in all genotypes studied here. Further, we cannot reject the notion that LPOR, either by itself or in association with other proteins/pigments, or the previously proposed VIPP1 (39) contributes to the maintenance of PLBs (32, 40). Although the lower content of LPOR in curt1abcd is directly related to the reduced accumulation of the corresponding transcript, we speculate that the size of the PLB unit cell defines the content of LPOR and/or its accessibility to lipid/membrane-remodeling proteins (e.g., proteases responsible for LPOR degradation). In this scenario, the higher LPOR content observed in oeCURT1A, even after 24 h of illumination, could be related to the supercondensed nature of PLBs in this mutant line. In addition, we speculate that CURT1 proteins might be involved in the tubular-to-lamellar transition and may contribute to establishing the optimal MGDG/DGDG ratio required for the regulation of Pchlide:LPOR:NADPH complex activity (41) and for the effective redistribution of membranes from disassembled PLBs into thylakoid membranes. However, this hypothesis remains to be tested.

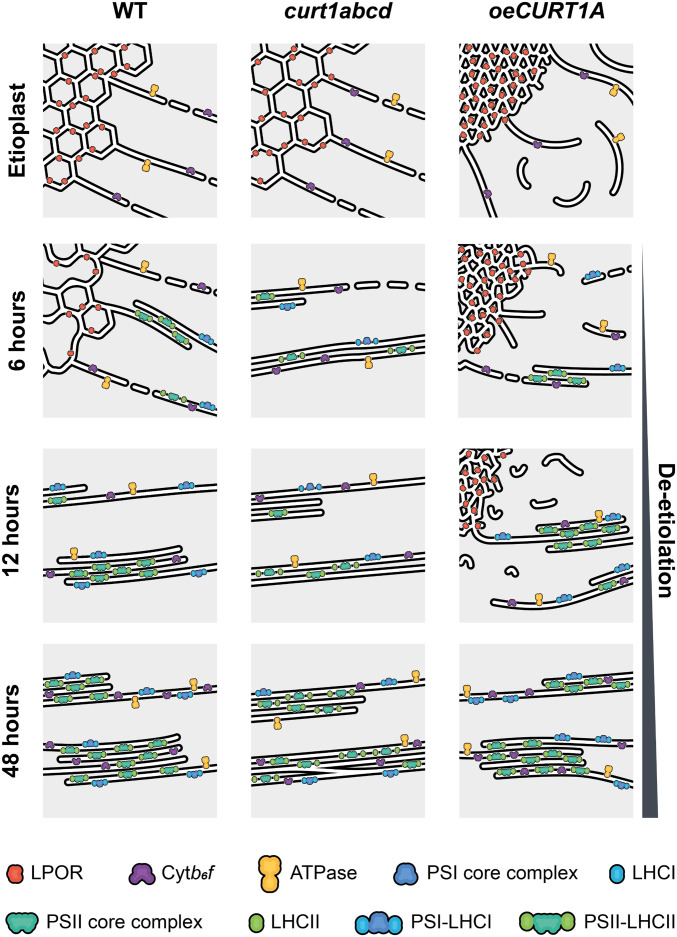

Fig. 6.

Proposed model for changes in membrane morphology and the distribution of proteins across membranes observed during de-etiolation in WT, curt1abcd, and oeCURT1A seedlings. The model summarizes the correlations between structure, protein accumulation, and assembly of photosynthetic complexes observed in WT (Left), curt1abcd (Middle), and oeCURT1A (Right) etioplasts before and after 6, 12, and 48 h of illumination.

We note the presence of abundant swollen vesicles exclusively in etiolated tissue in curt1abcd, in the context of PLB synthesis, and after 48 h of de-etiolation, when de novo membrane synthesis is already active. Vesicles are not observed between 3 and 24 h, during which time formation of the lamellar membrane system mainly proceeds by the direct transformation of already synthesized PLB membranes that signals their structural transition from tubular to lamellar (5). No delay in the initiation of grana formation was observed in curt1abcd, since the tubular-to-lamellar transformation at the onset of de-etiolation is fed by membrane material derived from the PLBs and does not require extensive transport from the envelope. Therefore, lack of CURT1 proteins presumably results in de novo synthesis of the thylakoid network through formation of swollen vesicles rather than direct connection of the envelope with the internal plastid membrane network. This hypothesis is supported by the lack of contact sites between thylakoids and plasma membrane in the Synechocystis CurT mutant (24) and argues for a role of CURT1 proteins in the transport of lipids and proteins from the inner envelope to the thylakoid membranes, as previously suggested (38).

As has been shown in earlier studies, we observed an increase in the accumulation of photosynthesis-related proteins during de-etiolation. We also confirmed the presence of Cytb6f, ATPase, and Rubisco-related proteins in the etioplast (1, 9). Interestingly, the accumulation of PSI- and PSII-related proteins is delayed in curt1abcd, which is consistent with the delay in chlorophyll accumulation. In contrast, the protein profiles of oeCURT1A and Ler-0 were similar overall, except for Lhca1, Lhcb2, and CP43. Despite the lower content of Lhcb2 and higher content of Lhca1 proteins observed in oeCURT1A, we did not observe any major changes in chlorophyll accumulation relative to Ler-0 within the first 24 h of de-etiolation. Rates of accumulation of mRNA and protein contents are poorly correlated during chloroplast development (42, 43), as is prominently exemplified by the LHC-related genes. Both Lhca1 and Lhcb2 transcripts exhibited two expression peaks at 3 and 24 h, corresponding to the two distinct developmental phases previously reported (3, 44). However, the magnitude of transcript accumulation was lower in curt1abcd compared to Col-0. Since Lhcb2 has been used as a marker for retrograde signaling (45), we presume that communication between chloroplasts and the nucleus is, to some extent, affected in curt1abcd. One of the most-studied regulatory feedback mechanisms in retrograde signaling is the tetrapyrrole pathway, which involves Pchilide-dependent anchoring of glutamyl-transefer ribonucleic acid reductase (GluTR) to the thylakoid membranes by protein FLUORESCENT (FLU) (46, 47). We speculate that the morphological changes in the thylakoid membranes might negatively affect the interaction between LPOR and FLU, resulting in faster accumulation of active GluTR in oeCURT1A, which might explain the slightly higher chlorophyll content after 48 h of illumination, compared to Ler-0. In contrast, curt1abcd showed reduced chlorophyll content, most likely due to decreased photoactive LPOR rather than alterations in FLU–Pchilide interaction. In agreement with this hypothesis, our results show that the Pchlide to Chlide conversion is not affected in curt1abcd or oeCURT1A, suggesting that the morphological changes in PLBs do not affect LPOR oligomerization. However, we did observe differences in Pchlide and Chlide profiles in oeCURT1A, which might be explained by a higher LPOR content and possibly a higher content of active GluTR.

The stacking of grana has been attributed to the accumulation of LHCII and PSII complexes and develops from lateral extension (increase in granum diameter) to vertical grana stacking, providing a protective milieu for the assembly of PSII (5, 48–50). Our results show that all studied genotypes display membrane-stacking after 6 h of light exposure, suggesting that CURT1 proteins are not required for the initiation of grana formation during de-etiolation (Fig. 6). However, the curt1abcd mutant is impaired in the regulation of grana diameter throughout de-etiolation, which points to a role for CURT1 proteins in the shaping of grana or, more specifically, the establishment of defined grana margins within stroma thylakoids, as proposed before (38). In contrast, the process of vertical grana stacking itself proceeds in a similar fashion in all the genotypes after 6 h of illumination and is correlated with the onset of and subsequent increase in photosynthetic activity (as determined by PAM fluorometry) and the formation of PSII and PSI complexes, as detected by 77-K spectroscopy (Fig. 6). However, ET of thylakoid membranes derived from Col-0, curt1abcd, Ler-0, and oeCURT1A after 48 h of illumination supports the assumption that thylakoid maturation has not reached completion in any of these genotypes by that point, as their thylakoids did not show the spatial organization of grana typical of mature leaves (21). Moreover, in curt1abcd and oeCURT1A in particular, thylakoid membranes continue to show splits/discontinuities within the grana stacks (Fig. 6). Only curt1abcd showed fewer stroma thylakoids and multiple grana membrane perforations that might facilitate the movement of elements from stroma to grana, in a manner similar to that proposed for cyanobacteria (51). Though oeCURT1A showed structural differences from WT, the overall composition of its major photosynthetic complexes was unchanged, whereas the changes observed in curt1abcd were correlated with abnormalities in the assembly of photosynthetic complexes and the attachment of LHCII to PSII. However, we cannot disregard the possibility that the aberrant LHCII-PSII association might reflect the action of nonphotochemical quenching mechanisms that are active at early stages of de-etiolation (48, 52).

Although the mechanisms behind CURT1-mediated regulation of thylakoid biogenesis are still not fully understood, our results demonstrate that CURT1 proteins are present in etioplasts and localize to PLB and PT membranes. Loss of CURT1 proteins results in a looser packing of the PLB paracrystalline lattice and leads to faster disassembly of PLBs, delayed protein accumulation, reduced chlorophyll synthesis, and accumulation of LHCII that does not become associated with PSII, all of which ultimately results in delayed onset of photosynthesis (Fig. 6). In contrast, overaccumulation of CURT1A primarily induces denser packing of PLBs, which correlates with increased LPOR content, but has no negative effects on protein or chlorophyll accumulation, complex assembly, or photosynthetic capacity after 48 h of de-etiolation (Fig. 6). Further studies using both curt1abcd and oeCURT1A will help us to gain a deeper understanding of the structural roles of PLBs and PTs, and their impact on MGDG/DGDG lipid ratios, carotenoid contents, and retrograde signaling between chloroplasts and the nucleus.

Materials and Methods

Information on plant material used, growth conditions, and experimental procedures employed in this study are detailed in SI Appendix. The provided methods comprise specifics on (thylakoid-) protein extraction and immunodecoration, RNA extraction and qRT-PCR, chlorophyll quantification, PAM fluorometry, and low-temperature (77 K) steady-state fluorescence measurements. Further, details about imaging techniques used (i.e., TEM, ET, and immuno-electron microscopy) are supplied.

Acknowledgments

M.P. acknowledges funding from the Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF15OC0016586), the Danish Council for Independent Research (7017-00122A), and the Copenhagen Plant Science Centre, University of Copenhagen. Ł.K. acknowledges funding from the National Science Centre, Poland, under Grant No. 2019/35/D/NZ3/03904. R.B. acknowledges financial support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (FOR 2092; BO 1482/17-2). A.S. was the recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship from the Carlsberg Foundation. We thank the Center for Advanced Bioimaging at the University of Copenhagen for providing facilities for TEM sample preparation and microscopy and the Core Facility for Integrated Microscopy in the Panum Institute (University of Copenhagen) for assistance with immunogold labeling and microscopy.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2113934118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix and all raw data are available upon request from the corresponding authors.

References

- 1.Kanervo E., et al., Expression of protein complexes and individual proteins upon transition of etioplasts to chloroplasts in pea (Pisum sativum). Plant Cell Physiol. 49, 396–410 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armarego-Marriott T., Sandoval-Ibañez O., Kowalewska Ł., Beyond the darkness: Recent lessons from etiolation and de-etiolation studies. J. Exp. Bot. 71, 1215–1225 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armarego-Marriott T., et al., Highly resolved systems biology to dissect the etioplast-to-chloroplast transition in tobacco leaves. Plant Physiol. 180, 654–681 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong G. A., Runge S., Frick G., Sperling U., Apel K., Identification of NADPH:protochlorophyllide oxidoreductases A and B: A branched pathway for light-dependent chlorophyll biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 108, 1505–1517 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kowalewska Ł., Mazur R., Suski S., Garstka M., Mostowska A., Three-dimensional visualization of the tubular-lamellar transformation of the internal plastid membrane network during runner bean chloroplast biogenesis. Plant Cell 28, 875–891 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blomqvist L. A., Ryberg M., Sundqvist C., Proteomic analysis of highly purified prolamellar bodies reveals their significance in chloroplast development. Photosynth. Res. 96, 37–50 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Zychlinski A., et al., Proteome analysis of the rice etioplast: Metabolic and regulatory networks and novel protein functions. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 4, 1072–1084 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryberg M., Sundqvist C., Spectral forms of protochlorophyllide in prolamellar bodies and prothylakoids fractionated from wheat etioplasts. Physiol. Plant. 56, 133–138 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleffmann T., et al., Proteome dynamics during plastid differentiation in rice. Plant Physiol. 143, 912–923 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sundqvist C., Dahlin C., With chlorophyll pigments from prolamellar bodies to light-harvesting complexes. Physiol. Plant. 100, 748–759 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu Y., Identification and roles of photosystem II assembly, stability, and repair factors in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 168 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franck F., et al., Regulation of etioplast pigment-protein complexes, inner membrane architecture, and protochlorophyllide a chemical heterogeneity by light-dependent NADPH:protochlorophyllide oxidoreductases A and B. Plant Physiol. 124, 1678–1696 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudowska L., Gieczewska K., Mazur R., Garstka M., Mostowska A., Chloroplast biogenesis–Correlation between structure and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 1380–1387 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartings S., et al., The DnaJ-like zinc-finger protein HCF222 is required for thylakoid membrane biogenesis in plants. Plant Physiol. 174, 1807–1824 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zagari N., et al., SNOWY COTYLEDON 2 promotes chloroplast development and has a role in leaf variegation in both Lotus japonicus and Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant 10, 721–734 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobayashi K., Fujii S., Sato M., Toyooka K., Wada H., Specific role of phosphatidylglycerol and functional overlaps with other thylakoid lipids in Arabidopsis chloroplast biogenesis. Plant Cell Rep. 34, 631–642 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi K, et al. Role of galactolipid biosynthesis in coordinated development of photosynthetic complexes and thylakoid membranes during chloroplast biogenesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 73, 250–261 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu X., et al., Convergence of light and chloroplast signals for de-etiolation through ABI4-HY5 and COP1. Nat. Plants 2, 16066 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun T., et al., ORANGE represses chloroplast biogenesis in etiolated Arabidopsis cotyledons via interaction with TCP14. Plant Cell 31, 2996–3014 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujii S., Nagata N., Masuda T., Wada H., Kobayashi K., Galactolipids are essential for internal membrane transformation during etioplast-to-chloroplast differentiation. Plant Cell Physiol. 60, 1224–1238 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Armbruster U., et al., Arabidopsis CURVATURE THYLAKOID1 proteins modify thylakoid architecture by inducing membrane curvature. Plant Cell 25, 2661–2678 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pribil M., et al., CURT1-mediated thylakoid plasticity is required for fine-tuning photosynthesis and plant fitness. Plant Physiol. (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hohner R., et al., Plastocyanin is the long-range electron carrier between photosystem II and photosystem I in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 15354–15362 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heinz S., et al. Thylakoid membrane architecture in synechocystis depends on CurT, a homolog of the granal CURVATURE THYLAKOID1 proteins. Plant Cell 28, 2238–2260 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hain T. M., et al. SPIRE, surface projection image recognition environment for bicontinuous phases: Application for plastid cubic membranes. bioRxiv [Preprint] (2021). 10.1101/2021.04.28.441812 (Accessed 29 April 2021). [DOI]

- 26.Bykowski M., et al., Spatial nano-morphology of the prolamellar body in etiolated Arabidopsis thaliana plants with disturbed pigment and polyprenol composition. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 586628 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bussi Y., et al., Fundamental helical geometry consolidates the plant photosynthetic membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 22366–22375 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andreeva A., Stoitchkova K., Busheva M., Apostolova E., Changes in the energy distribution between chlorophyll-protein complexes of thylakoid membranes from pea mutants with modified pigment content. I. Changes due to the modified pigment content. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 70, 153–162 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seluzicki A., Burko Y., Chory J., Dancing in the dark: Darkness as a signal in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 40, 2487–2501 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fujii S., Wada H., Kobayashi K., Role of galactolipids in plastid differentiation before and after light exposure. Plants 8, 357 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujii S., Kobayashi K., Nagata N., Masuda T., Wada H., Digalactosyldiacylglycerol is essential for organization of the membrane structure in etioplasts. Plant Physiol. 177, 1487–1497 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Floris D., Kühlbrandt W., Molecular landscape of etioplast inner membranes in higher plants. Nat. Plants 7, 514–523 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paddock T., Lima D., Mason M. E., Apel K., Armstrong G. A., Arabidopsis light-dependent protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase A (PORA) is essential for normal plant growth and development. Plant Mol. Biol. 78, 447–460 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fujii S., Kobayashi K., Nagata N., Masuda T., Wada H., Monogalactosyldiacylglycerol facilitates synthesis of photoactive protochlorophyllide in etioplasts. Plant Physiol. 174, 2183–2198 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sperling U., et al., Etioplast differentiation in arabidopsis: Both PORA and PORB restore the prolamellar body and photoactive protochlorophyllide-F655 to the cop1 photomorphogenic mutant. Plant Cell 10, 283–296 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park H., Kreunen S. S., Cuttriss A. J., DellaPenna D., Pogson B. J., Identification of the carotenoid isomerase provides insight into carotenoid biosynthesis, prolamellar body formation, and photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell 14, 321–332 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cazzonelli C. I., et al., A cis-carotene derived apocarotenoid regulates etioplast and chloroplast development. eLife 9, e45310 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang Z., et al., Thylakoid-bound polysomes and a dynamin-related protein, FZL, mediate critical stages of the linear chloroplast biogenesis program in greening Arabidopsis cotyledons. Plant Cell 30, 1476–1495 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Theis J., et al., VIPP1 rods engulf membranes containing phosphatidylinositol phosphates. Sci. Rep. 9, 8725 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wietrzynski W., Engel B. D., Chlorophyll biogenesis sees the light. Nat. Plants 7, 380–381 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gabruk M., Mysliwa-Kurdziel B., Kruk J., MGDG, PG and SQDG regulate the activity of light-dependent protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase. Biochem. J. 474, 1307–1320 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zoschke R., Bock R., Chloroplast translation: Structural and functional organization, operational control, and regulation. Plant Cell 30, 745–770 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chotewutmontri P., Barkan A., Dynamics of chloroplast translation during chloroplast differentiation in maize. PLoS Genet. 12, e1006106 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dubreuil C., et al., Establishment of photosynthesis is controlled by two distinct regulatory phases. Plant Physiol. 176, 1199–1214 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCormac A. C., Terry M.J., The nuclear genes Lhcb and HEMA1 are differentially sensitive to plastid signals and suggest distinct roles for the GUN1 and GUN5 plastid-signalling pathways during de-etiolation. Plant J. 40, 672–685 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fang Y., et al., The Arabidopsis glutamyl-tRNA reductase (GluTR) forms a ternary complex with FLU and GluTR-binding protein. Sci. Rep. 6, 19756 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hou Z., Yang Y., Hedtke B., Grimm B., Fluorescence in blue light (FLU) is involved in inactivation and localization of glutamyl-tRNA reductase during light exposure. Plant J. 97, 517–529 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shevela D., et al., ‘Birth defects’ of photosystem II make it highly susceptible to photodamage during chloroplast biogenesis. Physiol. Plant. 166, 165–180 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kouřil R., Dekker J. P., Boekema E. J., Supramolecular organization of photosystem II in green plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1817, 2–12 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Albanese P., Tamara S., Saracco G., Scheltema R. A., Pagliano C., How paired PSII-LHCII supercomplexes mediate the stacking of plant thylakoid membranes unveiled by structural mass-spectrometry. Nat. Commun. 11, 1361 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nevo R., et al., Thylakoid membrane perforations and connectivity enable intracellular traffic in cyanobacteria. EMBO J. 26, 1467–1473 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sacharz J., Giovagnetti V., Ungerer P., Mastroianni G., Ruban A. V., The xanthophyll cycle affects reversible interactions between PsbS and light-harvesting complex II to control non-photochemical quenching. Nat. Plants 3, 16225 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix and all raw data are available upon request from the corresponding authors.