Abstract

Purpose:

To determine classification criteria for Fuchs uveitis syndrome.

Design:

Machine learning of cases with Fuchs uveitis syndrome and 8 other anterior uveitides.

Methods:

Cases of anterior uveitides were collected in an informatics-designed preliminary database, and a final database was constructed of cases achieving supermajority agreement on the diagnosis, using formal consensus techniques. Cases were split into a training set and a validation set. Machine learning using multinomial logistic regression was used on the training set to determine a parsimonious set of criteria that minimized the misclassification rate among the anterior uveitides. The resulting criteria were evaluated on the validation set.

Results:

One thousand eighty-three cases of anterior uveitides, including 146 cases of Fuchs uveitis syndrome, were evaluated by machine learning. The overall accuracy for anterior uveitides was 97.5% in the training set and 96.7% in the validation set (95% confidence interval 92.4, 98.6). Key criteria for Fuchs uveitis syndrome included unilateral anterior uveitis with or without vitritis and either: 1) heterochromia or 2) unilateral diffuse iris atrophy and stellate keratic precipitates. The misclassification rates for FUS were 4.7% in the training set and 5.5% in the validation set, respectively.

Conclusions:

The criteria for Fuchs uveitis syndrome had a low misclassification rate and appeared to perform well enough for use in clinical and translational research.

PRECIS

Using a formalized approach to developing classification criteria, including informatics-based case collection, consensus-technique-based case selection, and machine learning, classification criteria for Fuchs uveitis syndrome were developed. Key criteria included unilateral anterior uveitis with either: 1) heterochromia or 2) unilateral diffuse iris atrophy and stellate keratic precipitates. The resulting criteria had a low misclassification rate.

The Fuchs uveitis syndrome, also known as Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis, was described by Fuchs in 1906.1 In case series of patients with uveitis, Fuchs uveitis syndrome accounts for 1 to 3% of cases.2 Patients present with the insidious onset of floaters, and/or glare and decreased vision due to cataract formation, or may be asymptomatic and have the uveitis detected on routine examination. Typical features of the Fuchs uveitis syndrome include anterior chamber inflammation, characteristic stellate keratic precipitates, and iris atrophy, most often resulting in heterochromia; vitritis also may be present. When heterochromia is present, the involved eye appears “bluer”, but heterochromia may be difficult to assess in patients with dark brown irides. Posterior synechiae and peripheral anterior synechiae do not occur and suggest an alternative diagnosis. The uveitis follows a chronic course and is unilateral in nearly all cases.2–4 Elevated intraocular pressure often occurs, but typically it is not present at the initial visit. Nevertheless, with follow-up it has been estimated that over 50% of patients with Fuchs uveitis syndrome will develop elevated intraocular pressure.2 Over time posterior subcapsular cataracts develop in greater than 80% of eyes.2,3,5 Correct identification of Fuchs uveitis syndrome is important for management, as corticosteroid therapy makes little difference to the outcome and typically is not needed. Furthermore, because posterior synechiae do not form and the uveitis is not painful, cycloplegia is not needed.2,3

The Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group is an international collaboration which has developed classification criteria for 25 of the most common uveitides.6–10 One of the diseases for which classification criteria were developed was the Fuchs uveitis syndrome.

Methods

The SUN Developing Classification Criteria for the Uveitides project proceeded in four phases as previously described: 1) informatics, 2) case collection, 3) case selection, and 4) machine learning.7–9,11

Informatics.

As previously described, the consensus-based informatics phase permitted the development of a standardized vocabulary and the development of a standardized, menu-driven hierarchical case collection instrument.7

Case collection and case selection.

De-identified information was entered into the SUN preliminary database by the 76 contributing investigators for each disease as previously described.7–9,11 Cases in the preliminary database were reviewed by committees of 9 investigators for selection into the final database, using formal consensus techniques described in the accompanying article..9,11 Because the goal was to develop classification criteria,10 only cases with a supermajority agreement (>75%) that the case was the disease in question were retained in the final database (i.e. were “selected”).11

Machine learning.

The final database then was randomly separated into a training set (~85% of cases) and a validation set (~15% of cases) for each disease as described in the accompanying article.10 Machine learning was used on the training set to determine criteria that minimized misclassification. The criteria then were tested on the validation set; for both the training set and the validation set, the misclassification rate was calculated for each disease. The misclassification rate was the proportion of cases classified incorrectly by the machine learning algorithm when compared to the consensus diagnosis. For Fuchs uveitis syndrome, the diseases against which it was evaluated were: cytomegalovirus (CMV) anterior uveitis, herpes simplex virus (HSV) anterior uveitis, varicella zoster virus (VZV) anterior uveitis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)-associated anterior uveitis, spondyloarthritis/HLA-B27-associated anterior uveitis, tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis (TINU), sarcoidosis-associated anterior uveitis, and syphilitic anterior uveitis.

The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at each participating center reviewed and approved the study; the study typically was considered either minimal risk or exempt by the individual IRBs.

Results

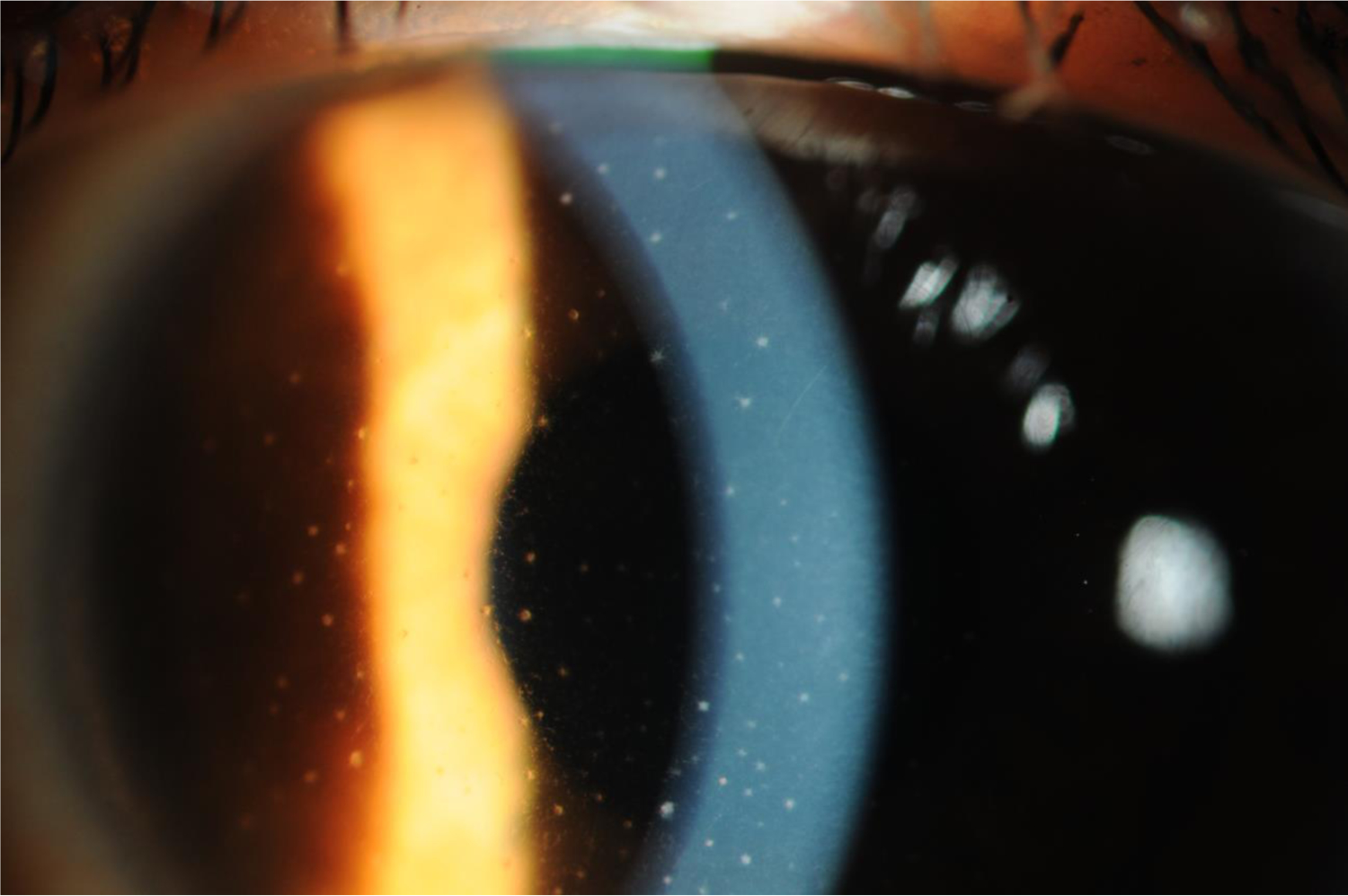

Two hundred forty-nine cases of Fuchs uveitis syndrome were collected, and 146 (59%) achieved supermajority agreement on the diagnosis during the “selection” phase and were used in the machine learning. These cases of Fuchs uveitis syndrome were compared to cases of other anterior uveitides, including 89 cases of CMV anterior uveitis, 123 cases of VZV anterior uveitis, 184 cases of spondyloarthritis/HLA-B27-associated anterior uveitis, 202 cases of JIA-associated anterior uveitis, 101 cases of HSV anterior uveitis, 94 cases of TINU, 112 cases of sarcoidosis-associated anterior uveitis, and 32 cases of syphilitic anterior uveitis. The details of the machine learning results for these diseases are outlined in the accompanying article.11 The characteristics at presentation to a SUN Working Group Investigator of cases with Fuchs uveitis syndrome are listed in Table 1. The relatively low proportion of cases with elevated intraocular pressure likely relates to the fact that data were collected for the initial presentation and not over time. The criteria developed after machine learning are listed in Table 2. Key clinical features for diagnosing Fuchs included evidence of an anterior uveitis with or without an accompanying vitritis, and either heterochromia (Figure 1) or both stellate keratic precipitates (Figure 2) and unilateral diffuse iris atrophy in the affected eye. The overall accuracy for anterior uveitides was 97.5% in the training set and 96.7% in the validation set (95% confidence interval 92.4, 98.6).11 The misclassification rate for Fuchs uveitis syndrome in the training set was 4.7%,11 and in the validation set 5.5%. The disease with which it most often was confused was HSV anterior uveitis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Cases with Fuchs Uveitis Syndrome

| Characteristic | Result |

|---|---|

| Number cases | 146 |

| Demographics | |

| Age, median, years (25th 75th percentile) | 35 (27, 45) |

| Age category, years (%) | |

| ≤16 | 5 |

| 17–50 | 82 |

| 51–60 | 8 |

| >60 | 5 |

| Gender (%) | |

| Men | 51 |

| Women | 49 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 75 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0 |

| Hispanic | 3 |

| Asian, Pacific Islander | 11 |

| Other | 7 |

| Missing | 4 |

| Uveitis History | |

| Uveitis course (%) | |

| Acute, monophasic | 0 |

| Acute, recurrent | 0 |

| Chronic | 92 |

| Indeterminate | 8 |

| Laterality (%) | |

| Unilateral | 98 |

| Unilateral, alternating | 0 |

| Bilateral | 2 |

| Ophthalmic examination | |

| Cornea | |

| Normal | 99 |

| Keratitis | 1 |

| Keratic precipitates (%) | |

| None | 1 |

| Fine | 25 |

| Round | 7 |

| Stellate | 68 |

| Mutton Fat | 0 |

| Other | 0 |

| Anterior chamber cells (%) | |

| Grade ½+ | 49 |

| 1+ | 26 |

| 2+ | 10 |

| 3+ | 1 |

| 4+ | 0 |

| Hypopyon (%) | 0 |

| Anterior chamber flare (%) | |

| Grade 0 | 66 |

| 1+ | 32 |

| 2+ | 1 |

| 3+ | 0 |

| 4+ | 0 |

| Iris (%) | |

| Normal | 6 |

| Posterior synechiae | 0 |

| Sectoral iris atrophy | 0 |

| Patchy iris atrophy | 3 |

| Diffuse iris atrophy | 45 |

| Heterochromia | 76 |

| Intraocular pressure (IOP), involved eyes | |

| Median, mm Hg (25th, 75th percentile) | 14 (12, 16) |

| Proportion patients with IOP>24 mm Hg either eye (%) | 8 |

| Vitreous cells (%) | |

| Grade 0 | 25 |

| ½+ | 25 |

| 1+ | 32 |

| 2+ | 16 |

| 3+ | 3 |

| 4+ | 0 |

| Vitreous haze (%) | |

| Grade 0 | 49 |

| ½+ | 13 |

| 1+ | 24 |

| 2+ | 13 |

| 3+ | 1 |

| 4+ | 0 |

Table 2.

Classification Criteria for Fuchs Uveitis Syndrome

|

Criteria

1. Evidence of anterior uveitis a. anterior chamber cells b. if vitreous cells are present, anterior chamber inflammation also should be present c. no evidence of active retinitis AND 2. Unilateral uveitis AND 3. Evidence of Fuchs uveitis syndrome a. heterochromia OR b. unilateral diffuse iris atrophy AND stellate keratic precipitates AND 4. Neither endotheliitis nor nodular, coin-shaped endothelial lesions Exclusions 1. Positive serology for syphilis using a treponemal test 2. Evidence of sarcoidosis (either bilateral hilar adenopathy on chest imaging or tissue biopsy demonstrating non-caseating granulomata) 3. Aqueous specimen PCR* positive for cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus or varicella zoster virus |

PCR = polymerase chain reaction

Figure 1.

Iris heterochromia in a patient with Fuchs uveitis syndrome.

Figure 2.

Stellate keratic precipitates in a patient with Fuchs uveitis syndrome.

Discussion

The classification criteria developed by the SUN Working Group for the Fuchs uveitis syndrome have a low misclassification rate, indicating good discriminatory performance against other anterior uveitides.

Fuchs uveitis syndrome can be diagnosed in the absence of heterochromia, particularly in eyes with dark brown irides. Hence, the term Fuchs uveitis syndrome has become preferred to Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis. Heterochromia was present in 76% of cases of Fuchs uveitis syndrome in the SUN database with stellate keratic precipitates and/or diffuse iris atrophy being present in eyes without evident heterochromia. Sectoral iris atrophy is a feature of HSV and VZV uveitis, and not of the Fuchs uveitis syndrome, and should lead to a diagnosis of one of these other two diseases.2,3,11 Unless cataract surgery has been performed, posterior synechiae are not seen in Fuchs and should lead to an alternate diagnosis.2,3 Other findings in Fuchs uveitis syndrome, such as iris nodules, iris crystals, and radial, twig-like angle vessels on gonioscopy,2,3 were either infrequent enough or not noted often enough to become part of the classification criteria.

A post-infectious etiology has been suggested for Fuchs uveitis syndrome.12–17 The finding of presumed intraocular antibody synthesis of antibodies to rubella on Goldman-Witmer analysis of aqueous obtained via paracentesis has been taken as evidence of prior rubella virus infection. Nevertheless, real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of aqueous samples for rubella viral RNA typically is positive only in a very small minority of cases and only in younger patients, suggesting previous rubella virus infection but not active infection is the norm.12,13 More recently an uncontrolled case series using metagenomic deep sequencing, a more sensitive method for RNA detection, detected rubella RNA in the aqueous of three patients with Fuchs uveitis syndrome, suggesting that Fuchs uveitis syndrome may be associated with some level of ongoing viral replication.14 Whether the disease is due to low level viral replication or to an immune response to previous infection or a combination of factors remains to be determined. The apparent decline in the incidence of Fuchs uveitis syndrome after adoption of widespread vaccination for rubella in the United States is consistent with a role for rubella virus infection in Fuchs uveitis syndrome.15 The association of Fuchs uveitis syndrome with occasional cases of toxoplasmic retinitis and the finding of elevated levels of intraocular antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in the aqueous of a few patients with Fuchs uveitis syndrome has been taken to suggest that some cases may be related epidemiologically to ocular toxoplasmosis,16,17 but there has been little evidence for active toxoplasmosis in the pathogenesis of Fuchs uveitis syndrome, and the evidence for a relationship to rubella appears stronger.

More problematic from a diagnostic perspective is the finding of similar clinical features between some eyes with a “Fuchs-like” anterior uveitis due to CMV anterior uveitis and eyes with Fuchs uveitis syndrome with negative PCR for CMV DNA in the anterior chamber. Although patients with CMV anterior uveitis were more likely to be older and male, the distribution is not sufficiently different for diagnostic purposes. Some features do suggest CMV anterior uveitis and should not be present when diagnosing Fuchs uveitis syndrome. These features of CMV anterior uveitis include: endotheliitis, endothelial cell loss, and nodular endothelial lesions with a surrounding halo and coin-shaped lesions.18,19 Although iris atrophy may be present in some patients with CMV anterior uveitis, it typically is patchy and rarely transilluminates, whereas the atrophy of Fuchs uveitis syndrome typically is diffuse and may transilluminate. Furthermore, the majority of cases of Fuchs uveitis syndrome have heterochromia, but heterochromia is rare in eyes with CMV anterior uveitis.18,19 The presence of features suggestive of CMV anterior uveitis should lead to consideration of aqueous paracentesis for PCR analysis for viral DNA, as PCR analysis of aqueous for CMV is able to reliably distinguish between the two diseases. Because of the relatively low yield in the United States of paracentesis for viruses when performed routinely on all cases of anterior uveitis,20 paracentesis for PCR to exclude viruses, such as CMV and HSV, was not included in the criteria.

More controversial is whether Fuchs uveitis syndrome is a morphological syndrome with several etiologies, akin to the acute retinal necrosis syndrome, or a specific diagnosis related to rubella virus infection. Because the Fuchs-like anterior uveitis with CMV anterior uveitis appears due to active viral infection in the anterior chamber, as evidenced by the PCR data and response to antiviral therapy,21,22 whereas the Fuchs uveitis syndrome has an infrequent and inconsistent relationship to active rubella virus infection and a stronger relationship to evidence of previous rubella virus infection (i.e. post-infectious), the SUN criteria currently treat CMV anterior uveitis and Fuchs uveitis syndrome as separate diseases and call CMV anterior uveitis with Fuchs-like features, “Fuchs-like” CMV anterior uveitis. In absence of a positive PCR for CMV from the aqueous or the characteristic endothelial lesions of CMV anterior uveitis, at this time the default diagnosis remains the Fuchs uveitis syndrome. Nevertheless, future studies using techniques such as metagenomic sequencing on aqueous specimens from a well-defined group of patients, classified using standardized criteria, could demonstrate that the Fuchs uveitis syndrome is a morphological syndromic diagnosis with several etiologies, resulting in a revised approach to classification.

The presence of any of the exclusions in Table 2 suggests an alternate diagnosis, and the diagnosis of Fuchs uveitis syndrome should not be made in their presence. In prospective studies many of these tests will be performed routinely, and the alternative diagnoses excluded. However, in retrospective studies based on clinical care, not all of these tests may have been performed. Hence the presence of an exclusionary criterion excludes Fuchs uveitis syndrome, but the absence of such testing does not exclude the diagnosis of Fuchs uveitis syndrome if the criteria for the diagnosis are met.

Classification criteria are employed to diagnose individual diseases for research purposes.10 Classification criteria differ from clinical diagnostic criteria, in that although both seek to minimize misclassification, when a trade-off is needed, diagnostic criteria typically emphasize sensitivity, whereas classification criteria emphasize specificity,10 in order to define a homogeneous group of patients for inclusion in research studies and limit the inclusion of patients without the disease in question that might confound the data. The machine learning process employed did not explicitly use sensitivity and specificity; instead it minimized the misclassification rate. Because we were developing classification criteria and because the typical agreement between two uveitis experts on diagnosis is moderate at best,9 the selection of cases for the final database (“case selection”) included only cases which achieved supermajority agreement on the diagnosis. As such, some cases which clinicians would diagnose with Fuchs uveitis syndrome will not be so classified by classification criteria.

In conclusion, the criteria for the Fuchs uveitis syndrome outlined in Table 2 appear to perform sufficiently well for use as classification criteria in clinical research.10,11

Acknowledgments

Grant support: Supported by grant R01 EY026593 from the National Eye Institute, the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; the David Brown Fund, New York, NY, USA; the Jillian M. And Lawrence A. Neubauer Foundation, New York, NY, USA; and the New York Eye and Ear Foundation, New York, NY, USA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fuchs E. About complications of heterochromia. Z Augenheilkd 1906;15:191–212. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones NP. Fuchs’ heterochromic uveitis: an update. Survey Ophthalmol 1993;37:253–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mohamed Q, Zamir E. Update on Fuchs’ uveitis syndrome. Current Opin Ophthalmol 2006;16:356–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jabs DA, Busingye J. Approach to the diagnosis of the uveitides. Am J Ophthalmol 2013;156:228–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tejwani S, Murthy S, Sangwan VS. Cataract extraction outcomes in patients with Fuchs heterochromic cyclitis. J Cataract Refract Surg 2006;32:1678–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jabs DA, Rosenbaum JT, Nussenblatt RB, the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Report of the first international workshop. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;140:509–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trusko B, Thorne J, Jabs D, et al. Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working Group. The SUN Project. Development of a clinical evidence base utilizing informatics tools and techniques. Methods Inf Med 2013;52:259–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okada AA, Jabs DA. The SUN Project. The future is here. Arch Ophthalmol 2013;131:787–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jabs DA, Dick A, Doucette JT, Gupta A, Lightman S, McCluskey P, Okada AA, Palestine AG, rosenbaum JT, Saleem SM, Thorne J, Trusko, B for the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working Group. Interobserver agreement among uveitis experts on uveitic diagnoses: the Standard of Uveitis Nomenclature experience. Am J Ophthalmol 2018; 186:19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aggarwal R, Ringold S, Khanna D, et al. Distinctions between diagnostic and classification criteria. Arthritis Care Res 2015;67(7):891–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Development of classification criteria for the uveitides. Am J Ophthalmol 2020;volume:pp. 96–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Quentin CD, Reiber H. Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis: rubella virus antibodies and genome in aqueous humor. Am J Ophthalmol 2004;138:46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruokonen PC, Metzner S, Ucer A, Torun N, Hofman J, Pleyer U. Introacular antibody synthesis against rubella virus and other microorganisms in Fuchs’ heterochromic cyclitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2010;248:565–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzales JA, Hinterwirth A, Shantha J, et al. Association of ocular inflammation with rubella virus persistence. JAMA Ophthalmol 2019;137:435–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birnbaum AD, Tessler HH, Schultz KL, et al. Epidemiologic relationship between Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis and the United States rubella vaccination program. Am J Ophthalmol 2007;144:424–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toledo de Abreu M, Belfort R Jr, Hirata PS. Fuchs’ heterochromic cyclitis and ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol 1982;93:739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akespi J, Terrada C, Bodaghi B, LeHoang P, Cassoux N. Fuchs’ heterochromic cyclitis: a post-infectious manifestation of ocular toxoplasmosis? Int Ophthalmol 2013;33:189–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chee SP, Jap A. Presumed Fuchs heterochromic iridocyclitis and Posner-Schlossman syndrome: comparison of cytomegalovirus-positive and negative eyes. Am J Ophthalmol 2008;146:883–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan NS-W, Chee S-P, Caspers L, Bodaghi B. Clinical features of CMV-associated anterior uveitis. Ocular Immunol Inflamm 2018;26:107–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anwar Z, Galor A, Albini TA, Miller D, Perez V, Davis JL. The diagnostic utility of anterior chamber paracentesis with polymerase chain reaction in anterior uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol 2013;155:781–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chee SP, Jap A. Cytomegalovirus anterior uveitis: outcome of treatment. Br J Ophthalmol 2010;94:1648–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Su CC, Hu FR, Wang TH et al. Clinical outcomes of cytomegalovirus-positive Posner Schlossman syndrome patients treated with topical ganciclovir therapy. Am J Ophthalmol 2014;158:1024–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]