Abstract

Purpose:

To determine classification criteria for syphilitic uveitis

Design:

Machine learning of cases with syphilitic uveitis and 24 other uveitides.

Methods:

Cases of anterior, intermediate, posterior, and panuveitides were collected in an informatics-designed preliminary database, and a final database was constructed of cases achieving supermajority agreement on the diagnosis, using formal consensus techniques. Cases were analyzed by anatomic class, and each class was split into a training set and a validation set. Machine learning using multinomial logistic regression was used on the training set to determine a parsimonious set of criteria that minimized the misclassification rate among the different uveitic classes. The resulting criteria were evaluated on the validation set.

Results:

Two hundred twenty-two cases of syphilitic uveitis were evaluated by machine learning with cases evaluated against other uveitides in the relevant uveitic class. Key criteria for syphilitic uveitis included a compatible uveitic presentation, (1) anterior uveitis, 2) intermediate uveitis, or 3) posterior or panuveitis with retinal, retinal pigment epithelial, or retinal vascular inflammation) and evidence of syphilis infection with a positive treponemal test. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reverse screening algorithm for syphilis testing is recommended. The misclassification rates for syphilitic uveitis in the training sets were: anterior uveitides 0%, intermediate uveitides 6.0%, posterior uveitides 0%, panuveitides 0%, and infectious posterior/panuveitides 8.6%. The overall accuracy of the diagnosis of syphilitic uveitis in the validation set was 100% (99% CI 99.5, 100) – i.e. the validation sets misclassification rates were 0% for each uveitic class.

Conclusions:

The criteria for syphilitic uveitis had a low misclassification rate and appeared to perform sufficiently well for use in clinical and translational research.

PRECIS

Using a formalized approach to developing classification criteria, including informatics-based case collection, consensus-technique-based case selection, and machine learning, classification criteria for syphilitic uveitis were developed. Key criteria included a compatible uveitic syndrome and evidence of syphilis with a positive treponemal test. The resulting classification criteria had a low misclassification rate.

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. If untreated, it results in a life-long infection and typically progresses through identifiable stages. Primary syphilis is a genital ulcerative disease, though other tissues may be affected; secondary syphilis typically results in a disseminated rash often with other systemic manifestations, such as fever, fatigue, mylagias, and adenopathy. Even if untreated, the symptoms and signs of primary and secondary syphilis spontaneously resolve, resulting in a state of latent infection, which may last indefinitely. Tertiary syphilis results in gumma formation and/or cardiac disease. Neuro-syphilis may occur with any stage of syphilis. In 2000 and 2001, the rates of primary and secondary syphilis in the United States were at their lowest since reporting began in 1941, at a rate of 2.1 cases/100,000 population.1,2 Since 2001, rates of primary and secondary syphilis have steadily risen in the United States, and by 2017 the rate was 9.5 cases/100,000 population, an increase mirrored elsewhere in the world.1,2 This increase in the United States has occurred in all races and ethnicities and in both genders, although the majority of cases occur in men, with approximately one-half of cases occurring in men who have sex with men. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection is a frequent co-infection among patients with syphilis, and a diagnosis of syphilis should lead to testing for HIV infection.1,2

Serologic testing for syphilis relies on the use of non-treponemal tests, such as the rapid plasmin regain (RPR) test and the Venereal Diseases Research Laboratory (VDRL) test, and treponemal tests, which may be enzyme immunoassays (e.g. the syphilis IgG test), chemoluminescence immunoassays (e.g. Fluorescent Treponemal Antibody [FTA] test), or Treponemal Pallidum Particle Agglutination (TP-PA) tests. The traditional screening algorithm involved screening with a non-treponemal test first and confirmation with a treponemal test.2 More recently, a reverse sequence screening algorithm has been proposed and used in some laboratories, and it employs screening with a treponemal test followed by confirmation with a non-treponemal test or an alternate treponemal test.3 Although the rate of false positive treponemal tests for syphilis is low (<1%), because they occur, diagnosis requires 2 positive tests, with at least one treponemal test.1–3 Non-treponemal test titers should fall with successful treatment and may convert to negative, whereas treponemal test results may remain positive despite successful treatment, indicating the utility of non-treponemal tests in disease management.2

Ocular syphilis rates also have been increasing since 2000–2001.4–6 Syphilis may cause any anatomic class of uveitis, including anterior uveitis, intermediate uveitis, posterior uveitis, or panuveitis, although posterior and panuveitis have been reported as most common.7–12 Syphilitic uveitis accounts for ~1% to 2.5% of uveitis cases at tertiary referral centers, and an estimated 0.5% to 0.65% of syphilis cases.4,6,7,11,12 In Brazil, syphilis increased from 1.8% of uveitis cases in 1980 to 6.1% in 2012–2013.6 Ocular syphilis has been reported to occur in as many as 9% of HIV-infected persons with syphilis, and has been reported to be the most frequent cause of uveitis in HIV-infected persons in the era of modern antiretroviral therapy.13–15 The British Ocular Syphilis Study estimated the annual incidence of ocular syphilis in the United Kingdom 0.3 cases per one million adult population.5

Because as many as one-third of cases of ocular syphilis may be treponemal test-positive and non-treponemal-test negative,7 many uveitis experts recommend that patients with uveitis be screened for syphilis using the reverse sequence screening algorithm (i.e. screening with a treponemal test, such as the FTA or syphilis IgG).16 Because of the frequent occurrence of neuro-syphilis with ocular syphilis, estimated to be as high has 50%,7,10 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend that patients with ocular syphilis undergo lumbar puncture, and that patients with ocular syphilis be treated with a neuro-syphilis regimen, regardless of the results of cerebrospinal fluid examination.2 A summary of the reverse sequence screening algorithm for syphilis is outlined in Table 1, and a summary of the CDC treatment recommendations for ocular syphilis management is outlined in Table 2.

Table 1.

Reverse Sequence Syphilis Screening Algorithm

| 1. Screen with a treponemal test, either an enzyme immunoassay (e.g. syphilis IgG) or a chemoluminescence assay (e.g. FTA*) |

| a. If treponemal test negative, syphilis is not present |

| b. If treponemal test positive, perform a non-treponemal test (e.g. RPR† or VDRL‡) |

| 2. Confirmation with non-treponemal test result |

| a. If non-treponemal test positive, patient has syphilis |

| b. If non-treponemal test negative, perform a different specific test (e.g. TP-PA§) |

| 3. Second (different) treponemal test result |

| a. If second treponemal test result positive, patient has syphilis |

| b. If second treponemal test result negative, patient does not have syphilis (may have false positive test or treated syphilis) |

FTA = fluorescent treponemal antibody.

RPR = rapid plasmin reagin.

VDRL = Venereal Disease Research Laboratory.

TP-PA = Treponemal pallidum particle agglutination.

Adapted from references 2 and 3.

Table 2.

United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations for the Treatment of Ocular Syphilis

| Test for HIV* (frequent co-infection) |

| Lumbar puncture even in the absence of clinical neurologic findings (neuro-syphilis frequently present) for CSF examination† |

| • If CSF examination abnormal, follow CSF with serial lumbar punctures as for neuro-syphilis to assess treatment response |

| Treat as neuro-syphilis regardless of lumbar puncture results |

| • 3–4 million units aqueous crystalline penicillin G intravenously every 4 hours for 10–14 days (or 18 to 24 million units per day continuous infusion) |

| • Consider adding following after completion of initial 10–14 days of treatment: benzathine penicillin, 2.4 million units once per week for up to 3 weeks |

| If non-treponemal serologic test abnormal pre-treatment, follow titer at 6, 12, and 24 months to assess response to therapy |

| • Titers ≥1:32 should have a 4-fold decline in titer by 12–24 months |

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

CSF = cerebrospinal fluid.

Adapted from reference 2.

The Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group is an international collaboration, which has developed classification criteria for the leading 25 uveitides using a formal approach to development and classification. Among the diseases studied was syphilitic uveitis.17–23

Methods

The SUN Developing Classification Criteria for the Uveitides project proceeded in four phases as previously described: 1) informatics, 2) case collection, 3) case selection, and 4) machine learning.19–22

Informatics.

As previously described, the consensus-based informatics phase permitted the development of a standardized vocabulary and the development of a standardized, menu-driven hierarchical case collection instrument.19

Case collection and case selection.

De-identified information was entered into the SUN preliminary database by the 76 contributing investigators for each disease as previously described.20,22 Cases in the preliminary database were reviewed by committees of 9 investigators for selection into the final database.20,22 Because the goal was to develop classification criteria,23 only cases with a supermajority agreement (>75%) that the case was the disease in question were retained in the final database (i.e. were “selected”), using formal consensus techniques described in the accompanying article..21,22

Machine learning.

The final database then was analyzed by anatomic class, and cases in each class were randomly separated into a learning set (~85% of the cases) and a validation set (~15% of the cases) for each disease as described in the accompanying article.22 Machine learning was used on the learning set to determine criteria that minimized misclassification. The criteria then were tested on the validation set; for both the learning set and the validation set, the misclassification rate was calculated for each disease. The misclassification rate was the proportion of cases classified incorrectly by the machine learning algorithm when compared to the consensus diagnosis. Because syphilis can present as any class of uveitis, relevant cases were analyzed within each class of uveitides. Cases of syphilitic anterior, intermediate, posterior, and panuveitis were evaluated in the machine learning phase against: anterior uveitides (cytomegalovirus [CMV] anterior uveitis, herpes simplex virus anterior uveitis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis-associated anterior uveitis, sarcoidosis-associated anterior uveitis, spondyloarthritis/HLA-B7-assoicated anterior uveitis, tubulointerstitial nephritis with uveitis, varicella zoster virus anterior uveitis), intermediate uveitides (multiple sclerosis-associated intermediate uveitis; pars planitis; intermediate uveitis, non-pars planitis type; sarcoidosis-associated intermediate uveitis), non-infectious posterior uveitides (acute posterior multifocal placoid pigment epitheliopathy, birdshot chorioretinitis, multifocal choroiditis with panuveitis, punctate inner choroiditis, sarcoidosis-associated posterior uveitis, serpiginous choroiditis), non-infectious panuveitides, (Behçet disease, sarcoidosis-associated panuveitis, sympathetic ophthalmia, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease), and infectious posterior and panuveitides (acute retinal necrosis [ARN], CMV retinitis, tubercular uveitis, and toxoplasmic retinitis).

The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) at each participating center reviewed and approved the study; the study typically was considered either minimal risk or exempt by the individual IRBs.

Results

Two hundred fifty cases of syphilitic uveitis were collected; 222 of these cases (89%) achieved supermajority agreement on the diagnosis during the “selection” phase and were used in the machine learning phase. The details of the machine learning results for these diseases are outlined in the accompanying article.22 The characteristics of cases with syphilitic uveitis are listed in Table 3. The characteristics of the cases with syphilitic uveitis by anatomic class are listed in Table 4. Review of images for posterior segment involvement by syphilitic uveitis suggested that posterior uveitis and posterior segment involvement in panuveitis typically presents as either: 1) placoid inflammation of the retinal pigment epithelium (sometimes previously termed “placoid chorioretinitis”, even though it is the retinal pigment epithelium and not the choroid that is involved, Figures 1 and 2); 2) necrotizing retinitis akin to that seen with cytomegalovirus retinitis or acute retinal necrosis (Figure 3); 3) a multifocal inflammation of the retina and/or retinal pigment epithelium (Figures 4 and 5); and 4) retinal vascular disease with either an occlusive retinal vasculitis or with retinal vascular sheathing and/or leakage. The multifocal lesions were typically 250 to 500 μm in size with some variability. In the SUN database necrotizing retinitis was seen only in cases with HIV infection. The criteria developed after machine learning are listed in Table 5. Because any anatomic class of uveitis can be caused by syphilis, and because of its protean manifestations, a positive treponemal test for syphilis was selected as the key diagnostic feature. For anterior and intermediate uveitis, the clinical features were not distinct from other anterior or intermediate uveitides. However, for posterior uveitides, the posterior segment involvement is inflammation of the retina or retinal pigment epithelium with a limited number of presentations. The overall accuracies by anatomic class were: anterior uveitides, learning set 97.5% and validation set 96.7% (95% confidence interval [CI] 92.4, 98.6); intermediate uveitides, learning set 99.8% and validation set 99.3% (95% CI 96.1, 99.9); non-infectious posterior uveitides, learning set 93.9% and validation set 98.0% (95% CI 94.3, 99.3); non-infectious panuveitides, learning set 96.3% and validation set 94.0% (95% CI 89.0, 96.8); and infectious posterior/panuveitides, learning set 92.1% and validation set 93.3% (95% CI 88.1, 96.3).22 The misclassification rates for syphilitic uveitis in the learning set were as follows: against anterior uveitides 0%, intermediate uveitides 6%, non-infectious posterior uveitides 0%, non-infectious panuveitides 3.4%, and against infectious posterior and panuveitides 8.6%. In the validation set the misclassification rates were as follows: against anterior uveitides 0%, intermediate uveitides 0%, non-infectious posterior uveitides 0%, non-infectious panuveitides 0%, and infectious posterior and panuveitides 0%. The overall accuracy of the diagnosis of syphilitic uveitis in the test set was 100% (95% CI 99.5, 100).

Table 3.

Characteristics of Cases with Syphilitic Uveitis

| Characteristic | Result |

|---|---|

| Number cases | 222 |

| Demographics | |

| Age, median, years (25th 75th percentile) | 49 (37, 56) |

| Gender (%) | |

| Men | 80 |

| Women | 20 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 50 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 14 |

| Hispanic | 12 |

| Asian, Pacific Islander | 5 |

| Other | 8 |

| Missing | 11 |

| Uveitis History | |

| Uveitis course (%) | |

| Acute, monophasic | 62 |

| Acute, recurrent | 2 |

| Chronic | 24 |

| Indeterminate | 12 |

| Laterality (%) | |

| Unilateral | 44 |

| Unilateral, alternating | 0 |

| Bilateral | 56 |

| Ophthalmic examination | |

| Keratic precipitates (%) | |

| None | 45 |

| Fine | 33 |

| Round | 11 |

| Stellate | 2 |

| Mutton Fat | 9 |

| Anterior chamber cells (%) | |

| Grade 0 | 26 |

| ½+ | 9 |

| 1+ | 21 |

| 2+ | 24 |

| 3+ | 17 |

| 4+ | 3 |

| Hypopyon (%) | 0 |

| Anterior chamber flare (%) | |

| Grade 0 | 50 |

| 1+ | 25 |

| 2+ | 17 |

| 3+ | 8 |

| 4+ | 1 |

| Iris (%) | |

| Normal | 86 |

| Posterior synechiae | 10 |

| Iris nodules | 4 |

| Sectoral iris atrophy | 0 |

| Patchy iris atrophy | 0 |

| Diffuse iris atrophy | 0 |

| Heterochromia | 0 |

| Intraocular pressure (IOP), involved eyes | |

| Median, mm Hg (25th, 75th percentile) | 15 (13, 18) |

| Proportion patients with IOP>24 mm Hg either eye (%) | 12 |

| Vitreous cells (%) | |

| Grade 0 | 18 |

| ½+ | 11 |

| 1+ | 24 |

| 2+ | 25 |

| 3+ | 17 |

| 4+ | 5 |

| Vitreous haze (%) | |

| Grade 0 | 33 |

| ½+ | 10 |

| 1+ | 20 |

| 2+ | 18 |

| 3+ | 11 |

| 4+ | 7 |

| Vitreous snowballs (%) | 6 |

| Pars plana snowbanks (%) | 0 |

| Optic disc edema (%) | 19 |

| Placoid inflammation of the retinal pigment epithelium (%) | 16 |

| Multifocal inflammation of the retina/retinal pigment epithelium (%) | 21 |

| Necrotizing retinitis | 7 |

| Occlusive retinal vasculitis (%) | 5 |

| Retinal vascular sheathing/leakage (%) | 34 |

| Systemic disease | |

| Immunocompromised patient (%)* | 40 |

| Anatomic uveitic class (%) | |

| Anterior | 13 |

| Intermediate | 39 |

| Posterior | 15 |

| Panuveitis | 33 |

All immunocompromised cases were Human Immunodeficiency Virus-infected.

Table 4.

Characteristics of Cases with Syphilitic Uveitis by Anatomic Class

| Characteristic/Uveitic Anatomic Class | Anterior Uveitis | Intermediate Uveitis | Posterior Uveitis | Panuveitis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number cases | 32 | 85 | 35 | 70 |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, median, years (25th 75th percentile) | 50 (34, 61) | 48 (38, 55) | 52 (39, 55) | 46 (35, 56) |

| Gender (%) | ||||

| Men | 84 | 79 | 83 | 82 |

| Women | 16 | 21 | 17 | 18 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 50 | 45 | 57 | 57 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 28 | 12 | 3 | 15 |

| Hispanic | 6 | 18 | 6 | 7 |

| Asian, Pacific Islander | 9 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Other | 6 | 5 | 19 | 7 |

| Missing | 1 | 15 | 12 | 11 |

| Uveitis History | ||||

| Uveitis course (%) | ||||

| Acute, monophasic | 31 | 62 | 62 | 69 |

| Acute, recurrent | 0 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| Chronic | 41 | 21 | 26 | 23 |

| Indeterminate | 28 | 12 | 9 | 8 |

| Laterality (%) | ||||

| Unilateral | 56 | 35 | 46 | 53 |

| Bilateral | 44 | 65 | 54 | 47 |

| Ophthalmic examination | ||||

| Keratic precipitates (%) | ||||

| None | 41 | 40 | 94 | 23 |

| Fine | 28 | 36 | 6 | 49 |

| Round | 13 | 12 | 0 | 17 |

| Stellate | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 |

| Mutton Fat | 19 | 8 | 0 | 9 |

| Anterior chamber cells (%) | ||||

| Grade 0 | 0 | 26 | 94 | 3 |

| ½+ | 6 | 9 | 3 | 14 |

| 1+ | 38 | 24 | 0 | 20 |

| 2+ | 44 | 14 | 3 | 40 |

| 3+ | 13 | 22 | 0 | 20 |

| 4+ | 0 | 5 | 0 | 3 |

| Anterior chamber flare (%) | ||||

| Grade 0 | 53 | 47 | 97 | 31 |

| 1+ | 25 | 27 | 3 | 33 |

| 2+ | 19 | 13 | 0 | 24 |

| 3+ | 3 | 11 | 0 | 10 |

| 4+ | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Iris (%) | ||||

| Normal | 90 | 90 | 100 | 86 |

| Posterior synechiae | 6 | 8 | 0 | 14 |

| Iris nodules | 9 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Intraocular pressure (IOP), involved eyes | ||||

| Median, mm Hg (25th, 75th percentile) | 15 (14, 17) | 15 (13, 18) | 15 (12, 20) | 15 (12, 17) |

| Percent patients with IOP>24 mm Hg either eye | 6 | 9 | 28 | 4 |

| Vitreous cells (%) | ||||

| Grade 0 | 59 | 1 | 43 | 7 |

| ½+ | 25 | 8 | 6 | 10 |

| 1+ | 13 | 26 | 17 | 36 |

| 2+ | 3 | 35 | 20 | 23 |

| 3+ | 0 | 21 | 11 | 20 |

| 4+ | 0 | 8 | 3 | 4 |

| Vitreous haze (%) | ||||

| Grade 0 | 0 | 18 | 51 | 23 |

| ½+ | 0 | 13 | 11 | 10 |

| 1+ | 0 | 27 | 9 | 23 |

| 2+ | 0 | 15 | 17 | 26 |

| 3+ | 0 | 12 | 6 | 17 |

| 4+ | 0 | 15 | 6 | 1 |

| Vitreous snowballs (%) | 0 | 9 | 14 | 0 |

| Optic disc edema (%) | 1 | 21 | 14 | 26 |

| Placoid inflammation of the retinal pigment epithelium (%) | 0 | 0 | 34 | 36 |

| Multifocal inflammation of the retina/retinal pigment epithelium (%) | 0 | 0 | 49 | 43 |

| Necrotizing retinitis (%) | 0 | 0 | 12 | 16 |

| Occlusive retinal vasculitis (%) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 9 |

| Retinal vascular sheathing or leakage (%) | 0 | 34 | 48 | 41 |

| Systemic disease | ||||

| HIV-infected* (%) | 47 | 35 | 40 | 36 |

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

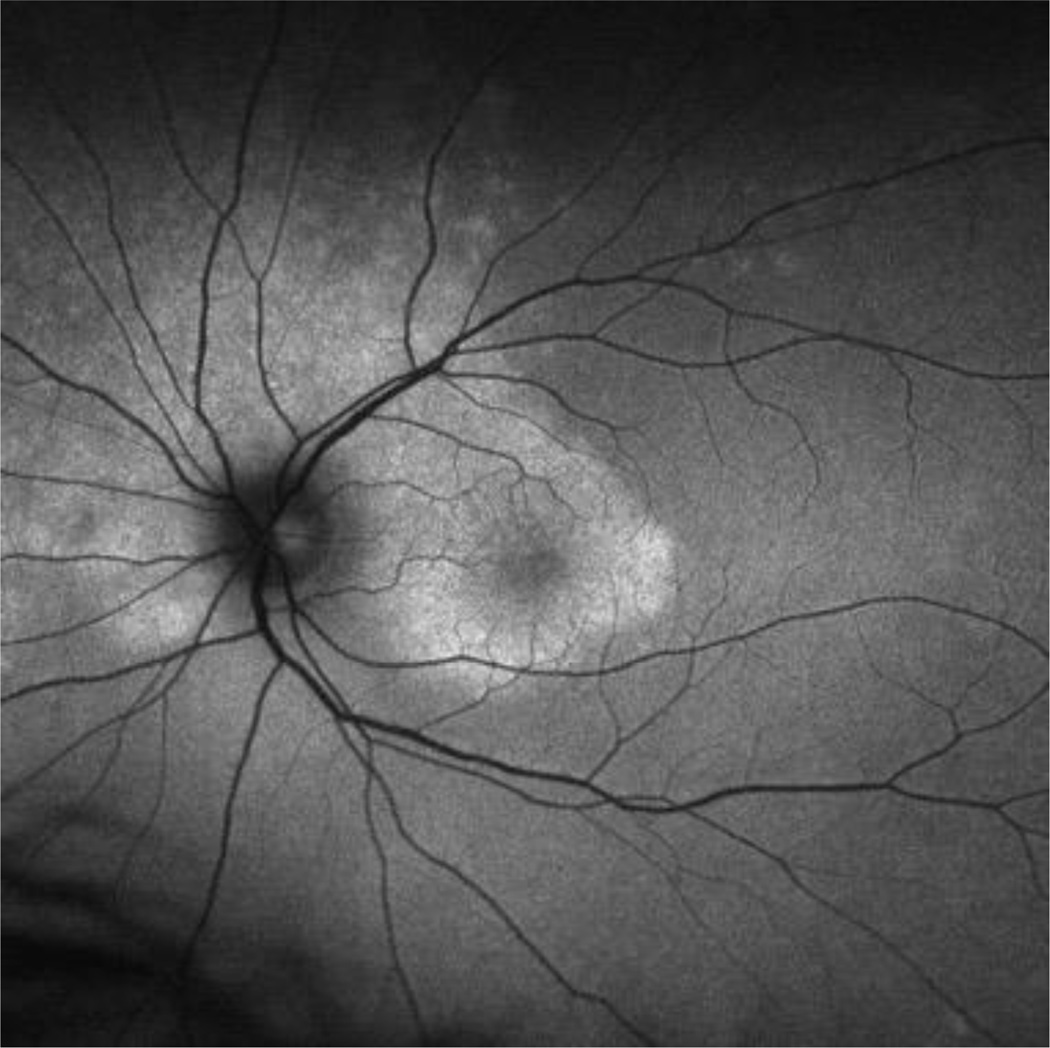

Figure 1.

Red-free fundus of a case of ocular placoid syphilis, demonstrating the placoid-appearing area of abnormality.

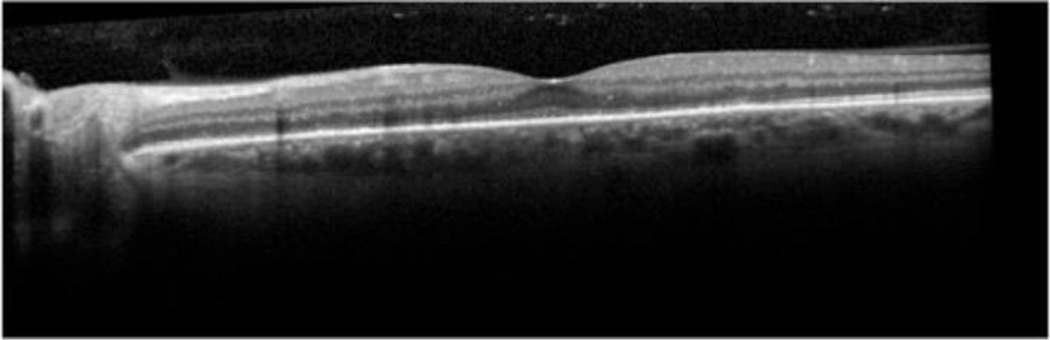

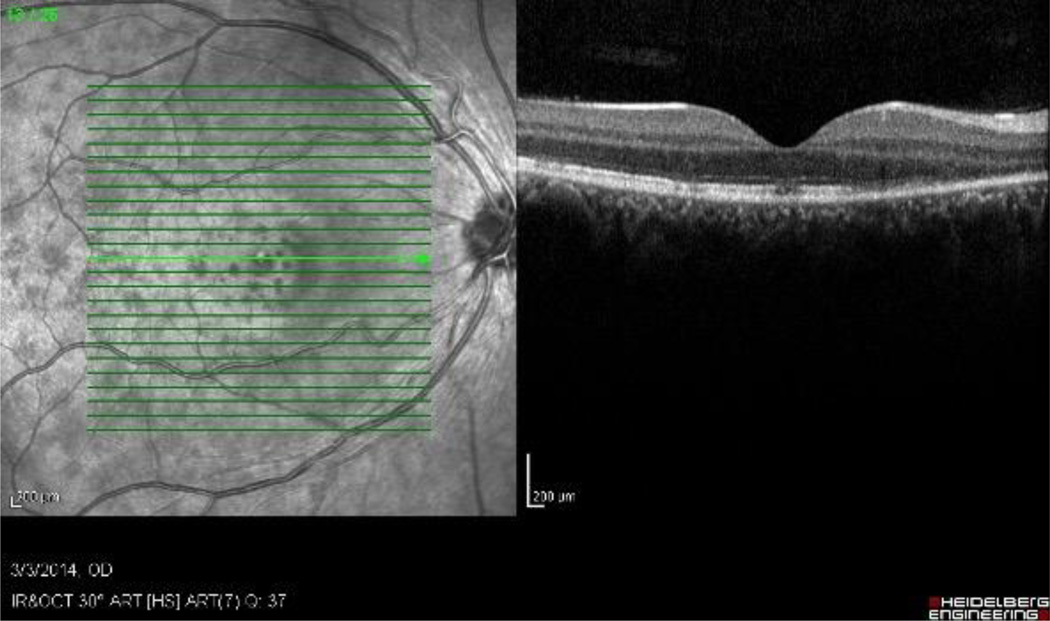

Figure 2.

Optical coherence tomogram of a case of ocular placoid syphilis, demonstrating the irregular appearance to the retinal pigment epithelium.

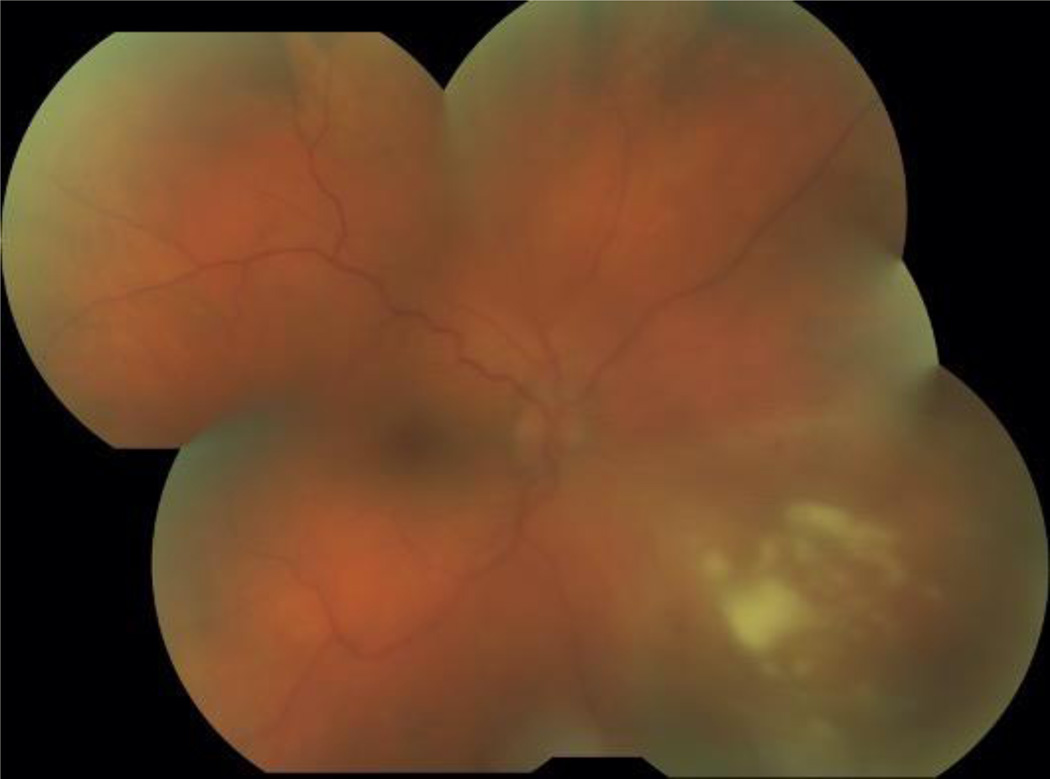

Figure 3.

Fundus photograph of necrotizing retinitis in a patient with ocular syphilis.

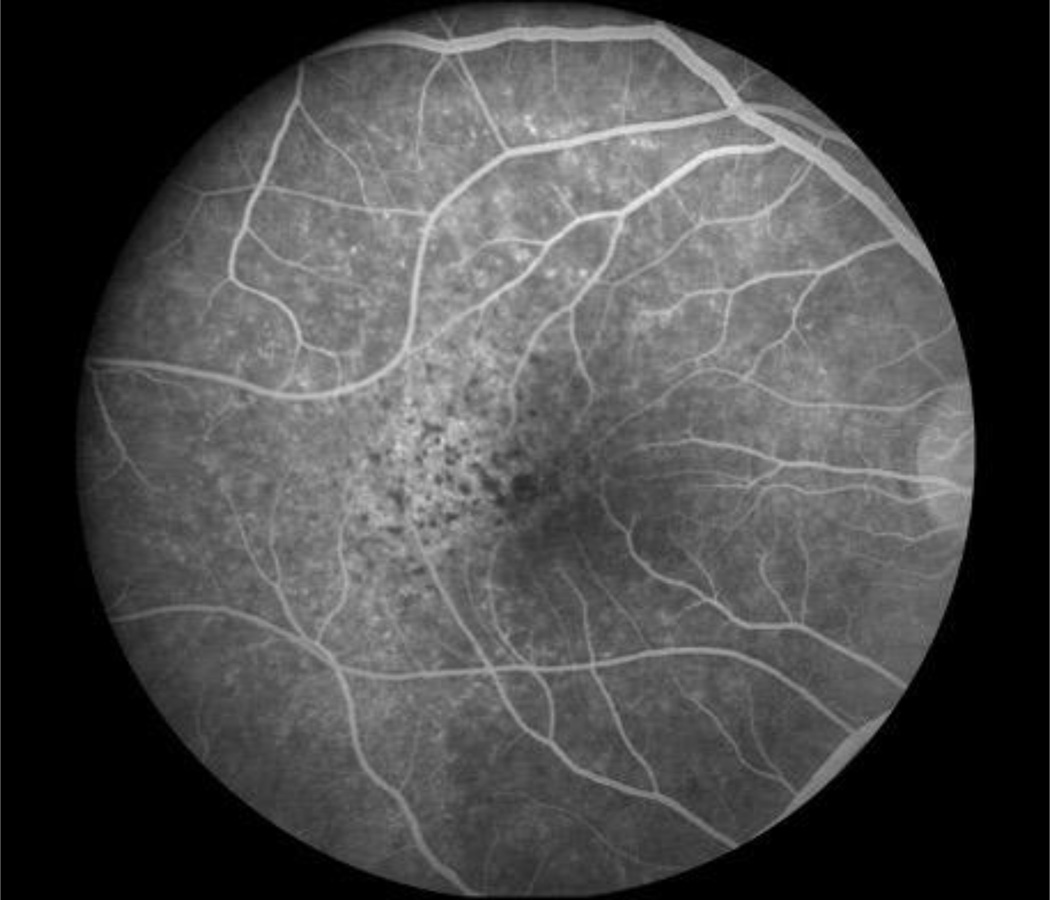

Figure 4.

Fluorescein angiogram of multifocal retinal/retinal pigment epithelium inflammation in a patient with ocular syphilis.

Figure 5.

Optical coherence tomogram of a case of multifocal retinitis in a patient with ocular syphilis, demonstrating multiple, variably sized areas of ellipsoid zone and outer retinal damage.

Table 5.

Classification Criteria for Syphilitic Uveitis

| Criteria | |

| 1. Uveitis with a compatible uveitic presentation, including | |

| a. Anterior uveitis OR | |

| b. Intermediate uveitis or anterior/intermediate uveitis OR | |

| c. Posterior or panuveitis with one of the following presentations | |

| a. Placoid inflammation of the retinal pigment epithelium or | |

| b. Multifocal inflammation of the retina/retinal pigment epithelium or | |

| c. Necrotizing retinitis or | |

| d. Retinal vasculitis | |

| AND | |

| 2. Evidence of infection with Treponema pallidum, either | |

| a. Positive treponemal test and non-treponemal test | |

| b. Positive treponemal test with two different treponemal tests | |

| Exclusions | |

| 1. History of adequate treatment for syphilitic uveitis* |

Adequate treatment outlined in Table 2.

Results of treponemal tests for syphilis were available on 2608 cases in the data base, of which 222 had syphilitic uveitis. All cases of syphilitic uveitis had a positive treponemal test for syphilis. Nine cases of other diseases had a positive treponemal test for syphilis, typically with a history of treated syphilis and a well characterized alternative disease. There were 2377 cases of other uveitides with a negative treponemal test. Using this population, the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values for syphilitic uveitis would be calculated as: 100%, 99.6%, 96.1%, and 100%, respectively.

Discussion

The classification criteria developed by the SUN Working Group for syphilis have a low misclassification rate, indicating good discriminatory performance against other uveitides.

Syphilitic uveitis can present as any anatomic class of uveitis. Previous case series have suggested that anterior uveitis occurs in 18% to 29%, intermediate uveitis in 6% to 25%, isolated posterior uveitis in 9% to 19%, and pan-uveitis in 47% to 49%.7,8 In this series nearly half the cases had posterior segment in involvement. Because of its protean manifestations, syphilis typically is in the differential for most uveitides, and its exclusion typically is needed. No ocular findings routinely identified syphilitic uveitis, so serologic testing is needed, particularly for anterior and intermediate uveitic presentations. For posterior and panuveitic presentations, imaging suggested that syphilis typically involves the retina, retinal pigment epithelium, or retinal blood vessels. Ocular “placoid” syphilis is a form of posterior segment syphilis that has a characteristic appearance, hyper-autofluorescence on fundus autofluorescence (Figure 1), a characteristic fluorescein angiogram (late diffuse hyperfluorescence with a well-demarcated circular border), and a characteristic optical coherence tomographic appearance (“ratty” irregular retinal pigment epithelium, Figure 2),24 but it accounts for a minority of cases and still requires serologic testing for diagnosis. Other posterior segment involvement included necrotizing retinitis (Figure 3) and a multifocal inflammation of the retina and/or retinal pigment epithelium (Figure 4), both of which also require serologic testing for diagnosis. Necrotizing retinitis was seen only in cases with HIV-infection and may be a variant associated with immune compromise. The SUN database did not contain sufficient information on immune status, such as CD4+ T cells, which might have enabled us to establish a relationship between necrotizing retinitis and immune compromise.

Serologic diagnosis of syphilis requires two positive tests, at least one of which must be a treponemal test.1–3 Because of the possibility (albeit rare) of a false positive treponemal test, CDC guidelines require a second test also be positive. With the reverse sequence screening algorithm, this can be either a non-treponemal test or a treponemal test.1–3 Although all cases in the database had a positive treponemal test, the data were not granular enough to confirm that all cases had two positive tests. Nevertheless, we recommend that CDC guidelines should be followed and that the reverse sequence screening algorithm should be used.3 Although our data suggest good performance for the use of a treponemal test for syphilis in the classification of syphilitic uveitis, some caution should be exercised. The cases collected do not represent a prospectively-collected cohort but rather a retrospectively collected cohort with an attempt to obtain similar numbers of individual diseases. As such, positive and negative predictive values, which are population dependent, might vary from our calculated numbers in other situations. Nevertheless, the sensitivity and specificity of the SUN data are in line with reported values for treponemal tests for diagnosing secondary, latent and tertiary syphilis,25 providing some reassurance of their performance in diagnosing syphilitic uveitis.

The results of serologic testing for syphilis should be interpreted in the context of the history of treatment for syphilis. Adequate (a neuro-syphilis treatment regimen) treatment for syphilis suggests that the uveitis may not be due to syphilis, as a positive treponemal test typically persists despite adequate treatment.26 However, remote treatment may be associated with reinfection and may require careful interpretation of non-treponemal test (e.g. the VDRL or RPR) titer data. Treatment for earlier stages of syphilis with inadequate treatment regimen for the syphilitic uveitis may not exclude a diagnosis of syphilitic uveitis, and syphilitic uveitis may still be present. Nevertheless, a history of adequate treatment for syphilis should exclude classification as syphilitic uveitis, despite the presence of a positive treponemal test, especially if there is evidence of an adequate treatment response (e.g. a ≥4-fold decline in non-treponemal test titer).

In retrospective studies response to treatment of the uveitis has been and could be used as a criterion for diagnosis of syphilitic uveitis. However, the SUN criteria were developed for prospective use, including possible treatment trials. As such, treatment response is not part of the SUN criteria. Nevertheless, some investigators may choose to add that the uveitis responds to adequate treatment as a criterion when conducting retrospective studies.

Classification criteria are employed to diagnose individual diseases for research purposes.23 Classification criteria differ from clinical diagnostic criteria, in that although both seek to minimize misclassification, when a trade-off is needed, diagnostic criteria typically emphasize sensitivity, whereas classification criteria emphasize specificity,23 in order to define a homogeneous group of patients for inclusion in research studies and limit the inclusion of patients without the disease in question that might confound the data. The machine learning process employed did not explicitly use sensitivity and specificity; instead it minimized the misclassification rate. Because we were developing classification criteria and because the typical agreement between two uveitis experts on diagnosis is moderate at best,20 the selection of cases for the final database (“case selection”) included only cases which achieved supermajority agreement on the diagnosis. As such, some cases which clinicians might diagnose with syphilitic uveitis may not be so classified by classification criteria.

In conclusion, the criteria for syphilitic uveitis outlined in Table 5 appear to perform sufficiently well for use as classification criteria in clinical research.22

Acknowledgments

Grant support: Supported by grant R01 EY026593 from the National Eye Institute, the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA; the David Brown Fund, New York, NY, USA; the Jillian M. And Lawrence A. Neubauer Foundation, New York, NY, USA; and the New York Eye and Ear Foundation, New York, NY, USA.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Douglas A. Jabs: none; Rubens Belfort: none; Bahram Bodaghi: none; Elizabeth Graham: none; Gary N. Holland: none; Susan L. Lightman: none; Neal Oden: none; Alan G. Palestine: none; Justine R. Smith: none; Jennifer E. Thorne: Dr. Thorne engaged in part of this research as a consultant and was compensated for the consulting service; Brett E. Trusko: none.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance; 2017. Accessed 11 April 2019 at cdc.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syphilis. 2015. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. Accessed 11 April 2019 at cdc.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Discordant results from reverse syphilis screening – five laboratories, United States, 2006–10. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:133–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliver SE, Aubin M, Atwell L, et al. Ocular syphilis – eight jurisdictions, United States, 2014–5. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:1185–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathew RG, Goh BT, Westcott MC. British ocular syphilis study (BOSS); 2-year national surveillance study of intraocular inflammation secondary to ocular syphilis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014;55:5394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez DG, Nascimento H, Nascimento C, Muccioli C, Belfort R Jr., Uveitis in Sao Paulo, Brazil: 1,053 new patients in 15 months. Ocular Immunol Inflamm 2019; ePub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tamesis RR, Foster CS. Ocular syphilis. Ophthalmology 1990;97:1281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moradi A, Salek S, Daniel E, et al. Clinical features and incidence rates of ocular complications in patients with ocular syphilis. Am J Ophthalmol 2015;159:344–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gass JD, Braunstein RA, Chenoweth RG. Acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis. Ophthalmology 1990;97:1288–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Browning DJ. Posterior segment manifestations of active ocular syphilis, their response to a neurosyphilis regimen of penicillin therapy, and the influence of human immunodeficiency virus status on response. Ophthalmology 2000;107:2015–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dutta Majumder P, Chen EJ, Shah J, et al. Ocular syphilis: an update. Ocular Immunol Inflamm 2017;ePub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furtado JM, Arantes TE, Nascimento H, et al. Clinical manifestations and ophthalmic outcomes of ocular syphilis at a time of re-emergence of the systemic infection. Scientific Reports 2018;8:12071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balba GP, Kumar PN, James AN, et al. Ocular syphilis in HIV-positive patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Med 2006;119:448.e21–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rose-Nussbaumer J, Goldstein DA, Thorne JE, et al. Uveitis in human immunosdeficiency virus-infected persons with CD4+ T lymphocyte count over 200 cells/μL. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2014;42:118–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jabs DA. Ocular manifestations of HIV infection. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1995;623–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliver GF, Stathis RM, Furtado JM, Arantes TE, McCluskey PJ, Matthews JM, International Ocular Syphilis Study Group, Smith JR. Current ophthalmology practice patterns for syphilitic uveitis. Br J Ophthalmol 2019; 103;1645–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jabs DA, Rosenbaum JT, Nussenblatt RB, the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Report of the first international workshop. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;140:509–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jabs DA, Busingye J. Approach to the diagnosis of the uveitides. Am J Ophthalmol 2013;156:228–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trusko B, Thorne J, Jabs D, et al. Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working Group. The SUN Project. Development of a clinical evidence base utilizing informatics tools and techniques. Methods Inf Med 2013;52:259–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okada AA, Jabs DA. The SUN Project. The future is here. Arch Ophthalmol 2013;131:787–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jabs DA, Dick A, Doucette JT, Gupta A, Lightman S, McCluskey P, Okada AA, Palestine AG, Rosenbaum JT, Saleem SM, Thorne J, Trusko, B for the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working Group. Interobserver agreement among uveitis experts on uveitic diagnoses: the Standard of Uveitis Nomenclature Experience. Am J Ophthalmol 2018; 186:19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) Working Group. Development of classification criteria for the uveitides. Am J Ophthalmol 2020;volume:pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aggarwal R, Ringold S, Khanna D, et al. Distinctions between diagnostic and classification criteria. Arthritis Care Res 2015;67:891–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pichi F, Ciardella AP, Cunningham ET, et al. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography findings in patients with acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinopathy. Retina 2014;34:373–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cantor A, Nelson HD, Daeges M, et al. Screening for syphilis in non-pregnant adolescents and adults: systematic review to update the 2004 US Preventative Services Task Force Recommendation. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US) 2016. June. (Evidence Synthesis No. 136). Table 3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.gov/books/NBK368468/table/ch1.t3/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romanowski B, Sutherland R, Fick GH, et al. Serologic response to treatment of infectious syphilis. Ann Intern Med 1991;114:1005–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]