Abstract

The c-Abl protein tyrosine kinase is activated by certain DNA-damaging agents and regulates induction of the stress-activated c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase (SAPK). Here we show that nuclear c-Abl associates with MEK kinase 1 (MEKK-1), an upstream effector of the SEK1→SAPK pathway, in the response of cells to genotoxic stress. The results demonstrate that the nuclear c-Abl binds to MEKK-1 and that c-Abl phosphorylates MEKK-1 in vitro and in vivo. Transient-transfection studies with wild-type and kinase-inactive c-Abl demonstrate c-Abl kinase-dependent activation of MEKK-1. Moreover, c-Abl activates MEKK-1 in vitro and in response to DNA damage. The results also demonstrate that c-Abl induces MEKK-1-mediated phosphorylation and activation of SEK1-SAPK in coupled kinase assays. These findings indicate that c-Abl functions upstream of MEKK-1-dependent activation of SAPK in the response to genotoxic stress.

c-Abl is a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase that is localized to the nucleus and cytoplasm. c-Abl is ubiquitously expressed as two 145-kDa isoforms (1a and 1b) as a result of alternative splicing of the first two exons (3). Targeted disruption of the c-abl gene in mice is associated with normal fetal development (59, 68). However, the animals are born runted, with head and eye abnormalities, and succumb as neonates with defective lymphopoiesis (59, 68). c-Abl is activated by ionizing radiation (IR) and certain other DNA-damaging agents (27, 30, 41). The DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) and the ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) gene product, effectors in the DNA damage response, contribute to the induction of c-Abl activity (2, 28, 60). Overexpression of c-Abl induces arrest in the G1 phase of the cell cycle by a mechanism dependent on p53 (18, 44, 58). Other work has shown that IR induces binding of c-Abl to p53 and G1 growth arrest by a p53-dependent, p21-independent mechanism (78). In addition, Rad51, a protein that promotes homologous DNA strand exchange and functions in recombinational DNA repair, is regulated by c-Abl-mediated phosphorylation (77). Activation of c-Abl by IR and certain other DNA-damaging agents also contributes to the induction of stress-activated protein kinases (SAPK; also known as c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase) (29, 30, 48). In concert with c-Abl functioning as an upstream effector of SAPK, other studies have shown that transient overexpression of active forms of Abl stimulates SAPK activity (50, 53, 57).

SAPK is a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family that also includes extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and the p38 MAPK (6, 9, 10, 19, 23, 34, 35, 43, 69, 73). In addition to DNA damage, SAPK is activated by cellular stress signals induced by the inflammatory cytokines, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and interleukin-1 (10, 35). The activity of SAPK is regulated by SAPK-ERK kinase 1 (SEK1) (57), also known as MKK4 (11), or MKK7 (67), which in turn is a substrate of MEK kinase 1 (MEKK-1) (76). The catalytic domain of MEKK-1 is homologous to the kinase domain of the STE 11 serine-threonine protein kinase involved in the control of mating in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (14). MEKK-1 is parallel to Raf-1 in the MAPK signaling cascade (38) and to MTK1 in the p38 MAPK pathway (63, 64). However, while a number of putative kinases, including MEKK-1, MEKK-2, MEKK-3, MEKK-4, TAK-1, MLK-3, SPRK, Tp12, and ASK1, have been reported to activate SEK1, MKK7, MKK3, or MKK6 (4, 20, 22, 39, 51, 56, 64, 76), the upstream activators of these MAPKKKs are largely unknown. The Rho GTPases, PAKs, and STE20-like kinases regulate SAPK activation by interacting with MEKK-1 (6–8, 33, 42, 49, 51, 65, 81). In addition, protein kinase Cβ (PKCβ) phosphorylates and activates MEKK-1 in phorbol ester-induced SAPK activation and differentiation of myeloid leukemia cells (24). By contrast, it is not known if MEKK-1 is involved in DNA damage-induced activation of SAPK.

The present studies demonstrate that c-Abl is an upstream effector of MEKK-1 in DNA damage-induced activation of SAPK. c-Abl associates with MEKK-1 in response to IR and other genotoxic agents. The results also demonstrate c-Abl-dependent activation of MEKK-1. These findings indicate that c-Abl functions upstream of MEKK-1 and that MEKK-1 controls activation of SAPK in the response to DNA damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Human U-937 myeloid leukemia cells (American Type Culture Collection Rockville, Md.) (suspension cells) were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (HI-FBS), 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, and 2 mM l-glutamine. Human embryonic kidney HEK293T (adherent) cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium with 10% HI-FBS and antibiotics. Irradiation was performed at room temperature using a Gammacell 1000 (Atomic Energy of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) under aerobic conditions with a 137Cs source emitting at a fixed dose rate of 13.3 Gy/min as determined by dosimetery. Cells were also treated with 20 ng of human recombinant TNF per ml (6.60 × 106 U/mg of protein; BASF, Inc., Worcester, Mass.) or 50 μM cisplatinum (CDDP; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.).

Subcellular fractionation.

Subcellular fractionation was performed as described previously (5). Cells were washed twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 1 ml hypotonic lysis buffer (1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 0.5 mM sodium orthovanadate, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 40 μg of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride per ml, 10 μg of leupeptin per ml, and 10 μg of aprotinin per ml; pH 7.2). After swelling on ice for 30 min, the cells were disrupted by Dounce homogenization (20 strokes). The homogenate was layered onto 1 ml of 1 M sucrose in lysis buffer and centrifuged at 1,600 × g for 15 min to pellet the nuclei. The supernatant above the sucrose cushion was collected and centrifuged at 150,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C to collect the soluble or cytoplasmic fraction. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer containing 1% NP-40 and 0.5% deoxycholate. The nuclear lysates were sonicated briefly on ice and centrifuged to remove the undissolved debris. The supernatant was used as a nuclear fraction.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis.

Cells (2 × 107 to 3 × 107) were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed in 1 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl; 0.5% NP-40; 0.5% Brij-96; 1 mM sodium vanadate; 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; 1 mM DTT; 10 μg of leupeptin and aprotinin per ml). Soluble proteins (ca. 200 μg) were incubated with anti-c-Abl (2 μg, K12; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, San Diego, Calif.) or anti-MEKK-1 (1 μg) (37) for 1 h and precipitated by using protein A-Sepharose for an additional 30 min. The immune complexes were washed three times with lysis buffer, separated by electrophoresis in 7.5 or 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels, and then transferred to nitrocellulose filters. After blocking with 5% milk in PBST (PBS in 0.05% Tween 20), the filters were incubated with anti-c-Abl (1:1,000 dilution, monoclonal antibody Ab-3; Oncogene Science) or anti-MEKK-1 (1:500 dilution) for 1 h and analyzed by chemiluminescence (ECL Detection System; Amersham).

Fusion protein binding assays.

Glutatione S-transferase (GST)–MEKK-1 was purified by affinity chromatography using glutathione-Sepharose beads. Lysates (200 to 250 μg) were incubated with 5 μg of immobilized GST or GST–MEKK-1 for 2 h at 4°C. The resulting protein complexes were washed three times with lysis buffer containing 0.1% NP-40 and boiled for 5 min in SDS sample buffer. The complexes were then separated by SDS–7.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-c-Abl (1:1,000 dilution). Lysates from irradiated U-937 cells were incubated with 5 μg of GST or GST–c-Abl SH3 (52) for 2 h at 4°C. The SH3 domain of c-Abl consists of 50 to 60 amino acids near the N terminus (nucleotides 209 to 408) that mediate protein-protein interactions by binding to proline-containing sites (52).

Coupled kinase assays.

Cells (2 × 107 to 3 × 107) were washed with PBS and lysed in 1 ml of lysis buffer. The cleared supernatants (600 μl) were incubated with preimmune rabbit serum (PIRS) or anti-c-Abl (2 μg, K12; Santa Cruz). The precipitated proteins were recovered on protein A-Sepharose beads and washed three times with lysis buffer, twice with 1 M LiCl, and twice with kinase buffer A (50 mM HEPES, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 0.1 mM NaV). The immunoprecipitated proteins were incubated with purified soluble GST-SEK1 (0.3 to 0.5 μg) in the presence of Mg2+ and ATP for 15 min at 30°C. The reaction was terminated by sedimentation of the beads. The supernatant was incubated with recombinant SAPK purified from bacteria for 15 min at 30°C followed by addition of GST-Jun and then incubation for an additional 15 min before termination with SDS.

Transient transfections and immunoprecipitations.

293T cells were seeded 24 h before transfection. Each plate was transfected in the presence of 1 ml of calcium phosphate coprecipitate containing 5 μg of DNA. After 12 h of incubation at 37°C, the medium was replaced and the cells were incubated for another 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared as described above and 200 to 250 μg of soluble proteins was incubated with PIRS, anti-c-Abl, anti-hemagglutinin (anti-HA), anti-GST, or anti-MEKK-1 and then analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. The protein complexes were washed with lysis buffer and then incubated in kinase buffer containing [γ-32P]ATP for 15 min at 30°C. Reactions were terminated by the addition of SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiling. Phosphorylated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

c-Jun kinase assays.

293T cells were transfected with pEBG-SAPK (57), pEBG-SEK1 (57), HA–MEKK-1 (75), HA–MEKK-1(K-R) (75), and c-Abl (58) or c-Abl(K-R) (58). After 12 h of incubation at 37°C, the medium was replaced and the cells were incubated for another 24 h. Cell lysates were prepared as described above, and 200 to 250 μg of soluble proteins was incubated with 5 μg of immobilized GST for 30 min at 4°C. The protein complexes were washed with lysis buffer and then incubated in kinase buffer containing [γ-32P]ATP for 15 min at 30°C. Reactions were terminated by the addition of SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiling. Phosphorylated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by autoradiography.

In vitro binding of c-Abl and MEKK-1.

The 85-kDa truncated form of MEKK-1 (70, 71) was labeled with [35S]methionine using pSupercatch–MEKK-1 (17, 21) in an in vitro translation system (TNT T7 Coupled Reticulocyte Lysate System; Promega). 35S-labeled MEKK-1 was incubated with glutathione-Sepharose beads bound to GST–c-Abl, GST–c-Abl(K-R), or GST in buffer A (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4; 10 mM MnCl2; 10 mM MgCl2; 100 μM ATP) for 30 min at 30°C. Adsorbates were assayed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

In vitro phosphorylation of MEKK-1.

GST–MEKK-1 (5 μg, Escherichia coli derived, 14-176; Upstate Biotechnology) or GST was incubated in buffer A with GST–c-Abl and [γ-32P]ATP for 30 min at 30°C. H6–MEKK-1 (amino acids 565 to 1100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was separately incubated with GST–c-Abl and [γ-32P]ATP for 30 min at 30°C. Phosphorylation of the reaction products was assessed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Kinase reactions were also performed in the presence of cold ATP, and the phosphorylated products were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-P-Tyr.

MEKK-1 activity assays in vitro.

A cDNA for the carboxy-terminal 80-kDa MEKK-1 was amplified by PCR using the rat full-length MEKK-1 (75) as a template and cloned into the yeast p426GAG expression vector which contains the GST domain under control of the yeast GAL1 promoter (63). GST–MEKK-1 (yeast derived; yMEKK-1) (24) or GST bound to glutathione beads was pretreated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (1 μl, 27.8 U/μl; GIBCO-BRL) for 1 h at 37°C. The beads were washed three times with lysis buffer containing 1% NP-40, twice with 0.5 M LiCl–100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), and once with kinase buffer B (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6; 20 mM MgCl2; 2 mM CaCl2). To purify c-Abl, Sf9 cells were infected with baculoviruses expressing GST–c-Abl or GST–c-Abl(K-R), and the lysates were purified by glutathione beads. GST–c-Abl or GST–c-Abl(K-R) fusion proteins were eluted from the beads and used in the kinase reactions. The beads containing GST–MEKK-1 were then incubated in buffer B in the presence of 1.0 μl of recombinant purified c-Abl or recombinant purified c-Abl(K-R) for 30 min at 30°C. After the kinase reaction, the beads were washed three times with lysis buffer containing 1% NP-40, twice with 0.5 M LiCl–100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) containing 1% NP-40 and 0.5% deoxycholic acid, and once with 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2. Kinase reactions were performed in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2, 20 μM ATP, [γ-32P]ATP, and 5 μg of GST–SEK1(K-R) (57) for 5 min at 30°C. The reaction was terminated by the addition of SDS sample buffer and boiling. The reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

RESULTS

Interactions of c-Abl with MEKK-1.

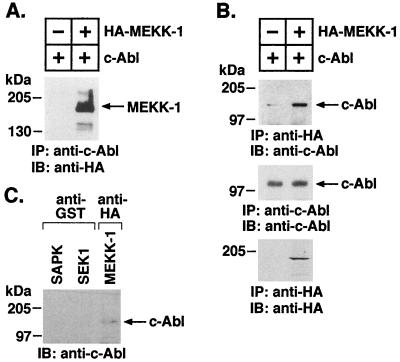

To determine whether c-Abl associates with MEKK-1, we transiently overexpressed HA–MEKK-1 with c-Abl in 293T cells and analyzed anti-c-Abl immunoprecipitates by immunoblotting with anti-HA. Reactivity of anti-HA with a >200-kDa protein supported the coprecipitation of MEKK-1 and c-Abl (Fig. 1A). In the reciprocal experiment, anti-HA immunoprecipitates were subjected to immunoblot analysis with anti-c-Abl. The results confirmed the identification of a complex containing MEKK-1 and c-Abl (Fig. 1B, upper panel). Analysis of anti-HA immunoprecipitates by immunoblotting with anti-HA demonstrated overexpression of HA-MEKK-1 (Fig. 1B, bottom panel). Lysates from transfected 293T cells were also subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-c-Abl. Analysis of protein precipitates by immunoblotting with anti-c-Abl demonstrated equal levels of c-Abl under both experimental conditions (Fig. 1B, middle panel). 293T cells were also transiently cotransfected with c-Abl and pEBG-SEK1, pEBG-SAPK, or HA–MEKK-1. GST-protein adsorbates or anti-HA immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-c-Abl. The results demonstrate that, in contrast to MEKK-1, there is no detectable association of c-Abl with SEK1 or SAPK (Fig. 1C). Analysis of anti-GST and anti-HA protein precipitates by immunoblotting with anti-GST and anti-HA, respectively, demonstrated equal expression of GST-SEK1, GST-SAPK, and HA–MEKK-1 (data not shown). Taken together, these findings indicate that c-Abl specifically associates with MEKK-1.

FIG. 1.

Association of c-Abl with MEKK-1. (A) 293T cells were transiently transfected with c-Abl (+) and vector (−) (lane 1) or c-Abl (+) and HA–MEKK-1 (+) (lane 2). Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-c-Abl, and the precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody. (B) 293T cells were transiently transfected with vector (−), c-Abl (+), or c-Abl and HA–MEKK-1. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA, and the precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-c-Abl antibody (upper panel). Anti-HA immunoprecipitates were also analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HA (middle panel). As a control, lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-c-Abl, and the precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-c-Abl (bottom panel). (C) 293T cells were transiently transfected with c-Abl and pEBG-SEK1, pEBG-SAPK, or HA–MEKK-1. Cell lysates were subjected to protein precipitation with GST or immunoprecipitation with anti-HA as indicated. The protein precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-c-Abl.

DNA damage induces the interaction of nuclear c-Abl and MEKK-1.

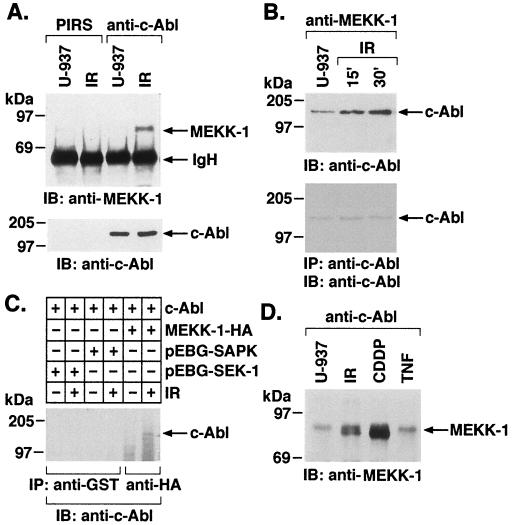

To assess potential interactions between c-Abl and MEKK-1 in response to DNA damage, U-937 cells were exposed to 20-Gy IR and harvested after 30 min, and total cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with PIRS or anti-c-Abl antibody. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MEKK-1. The full-length MEKK-1 cDNA encodes a 185- to 196-kDa protein (75), but in certain cell types MEKK-1 is expressed as an ∼80- to 85-kDa protein containing the kinase domain (70). There was little if any constitutive binding of c-Abl and the 80- to 85-kDa form of MEKK-1, whereas exposure to IR resulted in induction of this interaction (Fig. 2A). In the reciprocal experiment, anti-MEKK-1 immunoprecipitates were analyzed with anti-c-Abl. The results confirmed an IR-dependent association of c-Abl and MEKK-1 (Fig. 2B). U-937 cells were also exposed to 5- or 10-Gy IR and harvested after various intervals (0 or 30 min or 1 or 3 h). Lower exposures to IR resulted in induction of the interaction between c-Abl and MEKK-1 at 1 to 3 h (data not shown). To determine the specificity of c-Abl–MEKK-1 interactions in response to IR, 293T cells were transiently transfected with c-Abl and pEBG-SAPK, pEBG-SEK1, HA-SPRK (51) or HA–MEKK-1. Following transfection, cells were exposed to IR, and lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-GST or anti-HA. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-c-Abl. The results demonstrate that, in contrast to MEKK-1, there is no detectable association of c-Abl with SPRK, SAPK, or SEK1 (Fig. 2C and data not shown). Moreover, immunoblot analysis of total cell lysates with anti-GST and anti-HA demonstrated consistent equal expression of the transfected genes (data not shown). IR induces single and double DNA strand breaks, and cisplatinum (CDDP) forms DNA intrastrand cross-links (62). Treatment of U-937 cells with CDDP was also associated with increased binding of c-Abl and MEKK-1 (Fig. 2D). SAPK is activated by TNF (35), but by a c-Abl-independent mechanism (30). In this context, unlike IR and alkylating agents, TNF failed to induce the binding of c-Abl and MEKK-1 (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 2.

Genotoxic agents induce association of c-Abl and MEKK-1. (A) U-937 cells were treated with 20-Gy IR and lysed at 15 min. Equal amounts of proteins were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-c-Abl or PIRS. The precipitated proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MEKK-1 (upper panel) or anti-c-Abl (lower panel). IgH, the heavy chain of immunoglobulin G. (B) U-937 cells were treated with IR and harvested at the indicated times. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-MEKK-1. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-c-Abl (upper panel). As a control, anti-c-Abl immunoprecipitates were also analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-c-Abl (bottom panel). (C) 293T cells were cotransfected with c-Abl and pEBG-SEK1 or pEBG-SAPK. At 36 h after transfection, cells were exposed to 20-Gy IR and harvested after 1 h. Cell lysates were subjected to protein precipitation by GST, and the precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-c-Abl. Analysis of anti-GST and anti-HA immunoprecipitates by immunoblotting with anti-GST and anti-HA demonstrated equal expression of GST-SEK1, GST-SAPK, and HA–MEKK-1. (D) U-937 cells were treated with IR and harvested at 15 min. Cells were also treated with 50 μM CDDP for 1 h or 20 ng of TNF per ml for 10 min. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-c-Abl, and the precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MEKK-1.

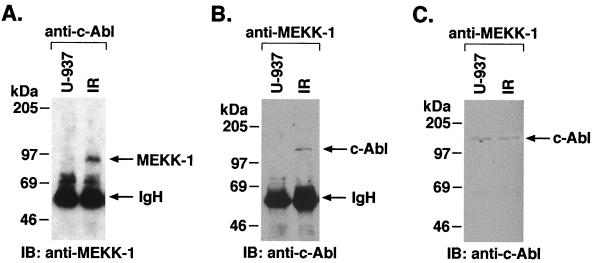

To define the subcellular localization of the interaction between c-Abl and MEKK-1, we subjected nuclear and cytoplasmic lysates from control and irradiated cells to immunoprecipitation with anti-c-Abl. Immunoblot analysis of the immunoprecipitates from control cells demonstrated little if any reactivity with MEKK-1 in the nuclear fraction. A low constitutive interaction between c-Abl and MEKK-1 was detected in the cytoplasmic fraction (Fig. 3C). By contrast, the association of c-Abl and MEKK-1 was significantly increased in the nuclear, but not cytoplasmic, lysates from irradiated cells (Fig. 3A and C). This interaction between c-Abl and MEKK-1 was further examined in a reciprocal experiment in which anti-MEKK-1 immunoprecipitates from nuclear extracts of control and irradiated cells were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-c-Abl. The results confirmed the association of nuclear c-Abl and MEKK-1 (Fig. 3B). To determine whether MEKK-1 translocates in response to genotoxic stress, anti-MEKK-1 immunoprecipitates from nuclear lysates of control and irradiated cells were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MEKK-1. The results demonstrate little, if any, change in nuclear MEKK-1 levels in the response to IR (data not shown). Taken together, these findings suggest that nuclear c-Abl associates with MEKK-1 in response to genotoxic stress.

FIG. 3.

Association of c-Abl and MEKK-1 in nuclei and cytoplasm. U-937 cells were exposed to IR and harvested at 15 min. (A) Nuclear lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-c-Abl, and the precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MEKK-1. (B) Nuclear lysates from control and irradiated cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-MEKK-1. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-c-Abl. (C) Cytoplasmic lysates from control and irradiated cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-MEKK-1, and the protein precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-c-Abl.

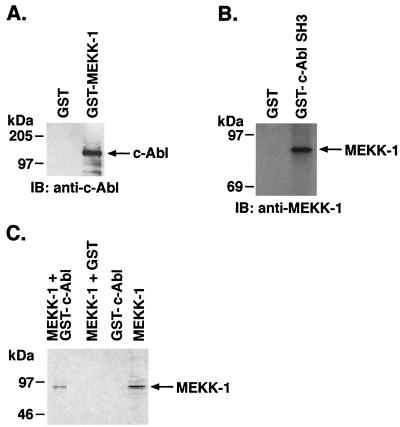

To determine the nature of the interaction of c-Abl and MEKK-1, lysates from irradiated U-937 cells were incubated with GST or GST–MEKK-1, and the resulting precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-c-Abl. In contrast to GST, c-Abl was detectable in the adsorbates to GST–MEKK-1 (Fig. 4A). Since MEKK-1 has a potential binding sequence for the c-Abl SH3 domain (PCSSAPSVP; aa 967 to 975) (16, 52), lysates from irradiated U-937 cells were incubated with GST or GST-Abl SH3 (52), and the resulting precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MEKK-1. The results demonstrate that, in contrast to GST, MEKK-1 was detectable in the adsorbates to GST–c-Abl SH3 (Fig. 4B). Of note, preparation of GST–MEKK-1 in bacteria may not accurately reflect the interaction of endogenous MEKK-1, which is subject to different posttranslational modifications in mammalian cells. To further assess the interaction of c-Abl and MEKK-1, we incubated purified recombinant c-Abl with in vitro-translated 35S-labeled His-tagged MEKK-1. Analysis of the anti-c-Abl immunoprecipitates by autoradiography demonstrated binding of c-Abl to MEKK-1 (Fig. 4C). While these findings suggest that c-Abl directly associates with MEKK-1, the results do not rule out the possibility of that protein from the reticulocyte lysates that mediates the interaction between c-Abl and MEKK-1.

FIG. 4.

Direct interaction of c-Abl and MEKK-1. (A) Lysates from irradiated U-937 cells were incubated with GST or GST–MEKK-1 fusion protein. Protein precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-c-Abl. (B) Lysates from irradiated U-937 cells were incubated with GST or GST–c-Abl SH3 domain. Protein precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MEKK-1. (C) The 80-kDa form of MEKK-1 was labeled with [35S]methionine using an in vitro translation kit. 35S-labeled MEKK-1 was incubated with glutathione-Sepharose beads bound to GST–c-Abl (lane 1) or GST (lane 2) for 30 min at 30°C. GST–c-Abl was also incubated with buffer in the absence of MEKK-1 (lane 3). 35S-labeled MEKK-1 was used as a positive control (lane 4). The adsorbates were assessed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

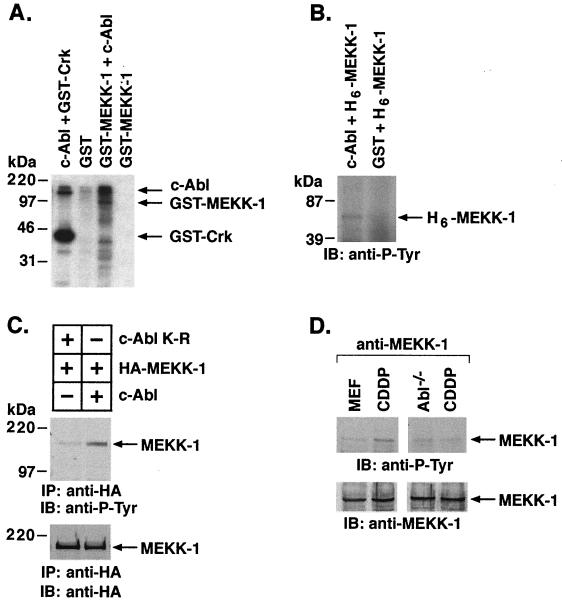

c-Abl phosphorylates MEKK-1.

To assess in part the functional significance of the interaction of c-Abl and MEKK-1, we incubated purified recombinant c-Abl with eluted and heat-inactivated GST–MEKK-1 (containing the carboxy-terminal portion of the 80- to 85-kDa MEKK-1) or GST in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. Analysis of the reaction products demonstrated phosphorylation of GST–MEKK-1 (Fig. 5A). Similar results were obtained when a purified His-tagged MEKK-1 (aa 565 to 1100) protein was used as a substrate for the active c-Abl kinase (data not shown). To confirm tyrosine phosphorylation of His-tagged MEKK-1, purified c-Abl was incubated with His-tagged MEKK-1 in the presence of cold ATP. The phosphorylated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-P-Tyr. The results demonstrate tyrosine phosphorylation of His-tagged MEKK-1 by c-Abl (Fig. 5B). To assess c-Abl-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of MEKK-1 in cells, 293T cells were cotransfected with HA–MEKK-1 and wild-type c-Abl or c-Abl(K-R). The lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-P-Tyr antibody. To monitor expression of HA–MEKK-1, anti-HA immunoprecipitates were also analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HA. The results demonstrate c-Abl kinase-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of MEKK-1 (Fig. 5C). To assess c-Abl-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of MEKK-1 in response to genotoxic stress, embryo fibroblasts from wild-type and Abl−/− mice were treated with CDDP, and anti-MEKK-1 immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-P-Tyr. The results demonstrate that treatment of wild-type, but not Abl−/−, fibroblasts with CDDP is associated with an increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of MEKK-1 (Fig. 5D). Taken together, these findings support c-Abl-mediated phosphorylation of MEKK-1 in vitro and in the response to genotoxic stress.

FIG. 5.

Phosphorylation of MEKK-1 by c-Abl. (A) Purified recombinant c-Abl was incubated with GST (lane 2) or kinase-inactive (heat-inactivated) GST–MEKK-1 (E. coli derived; 80-kDa catalytic fragment) (lane 3) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. Heat-inactivated GST–MEKK-1 was incubated with buffer (lane 4). As a control, purified c-Abl was incubated with GST-Crk in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. The reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (B) Purified recombinant c-Abl was incubated with His-tagged MEKK-1 (aa 565 to 1100; Santa Cruz) in the presence of cold ATP. After the kinase reactions, phosphorylated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose filters, and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-P-Tyr. (C) 293T cells were transiently cotransfected with HA–MEKK-1 and c-Abl (lane 1) or c-Abl(K-R) (lane 2). Total cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA, and the precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-P-Tyr. (D) Embryo fibroblasts from wild-type (MEF) or Abl−/− mice were treated with 50 μM CDDP for 1 h. Lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-MEKK-1, and the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-P-Tyr (upper panel). As a control, anti-MEKK-1 immunoprecipitates were also analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MEKK-1 (lower panel).

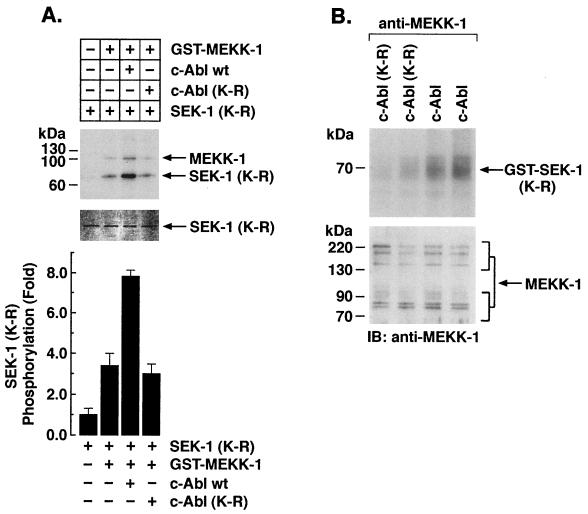

c-Abl activates MEKK-1 in vitro and in the response to DNA damage.

To determine whether c-Abl affects MEKK-1 activity, kinase-active (yeast-derived) yMEKK-1 bound to glutathione beads was incubated with alkaline phosphatase to inhibit constitutive autophosphorylation. After incubation, the beads were thoroughly washed and incubated in the presence of purified c-Abl or c-Abl(K-R) and ATP. The GST–MEKK-1-containing beads were washed again after the first kinase reaction and then incubated with purified SEK1(K-R) and [γ-32P]ATP. The phosphorylated products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The results demonstrate that, in contrast to c-Abl(K-R), preincubation of c-Abl with GST–MEKK-1 and then removal of c-Abl is associated with induction of MEKK-1 activity (Fig. 6A). The results also demonstrate that phosphorylation of GST–MEKK-1 is increased in the presence of c-Abl (Fig. 6A). As a control, protein analysis demonstrated equal amounts of SEK1(K-R) in the kinase reactions (Fig. 6A, middle panel). To determine if c-Abl activates MEKK-1 in cells, we transiently overexpressed wild-type c-Abl or c-Abl(K-R) (58) in 293T cells and measured phosphorylation of purified GST-SEK1(K-R) by anti-MEKK-1 immunoprecipitates. The results demonstrate increased phosphorylation of GST-SEK1(K-R) by endogenous MEKK-1 in cells overexpressing wild-type c-Abl, but not c-Abl(K-R) (Fig. 6B). U-937 cells were also exposed to IR and anti-c-Abl immunoprecipitates were incubated with GST-SEK1(K-R) in kinase reactions. The results demonstrate that anti-c-Abl immunoprecipitates from IR-treated, but not untreated, U-937 cells exhibit increased phosphorylation of GST-SEK1(K-R) (Fig. 7A). By contrast, incubation of purified c-Abl with GST-SEK1(K-R) demonstrated no detectable phosphorylation (Fig. 7B). To assess c-Abl-dependent activation of MEKK-1 in response to DNA damage, wild-type and c-Abl−/− mouse embryo fibroblasts were treated with CDDP, and anti-MEKK-1 immunoprecipitates were assayed by in vitro immune complex kinase assays by using GST-SEK1(K-R) as the substrate. The results demonstrate that treatment of wild-type, but not c-Abl−/−, fibroblasts with CDDP is associated with an increase in activation of MEKK-1 (Fig. 7C). These findings demonstrate that phosphorylation of MEKK-1 by c-Abl is associated with induction of MEKK-1 kinase activity in vitro and in response to genotoxic stress.

FIG. 6.

Activation of MEKK-1 by c-Abl. (A) Kinase-active GST–MEKK-1 (yeast derived; yMEKK-1) bound to glutathione beads was incubated with alkaline phosphatase. After being washed, the beads (lanes 2 to 4) were incubated in the presence (lanes 3 and 4) or absence (lanes 1 and 2) of purified recombinant c-Abl (lane 3) or c-Abl(K-R) (lane 4) and ATP. The GST–MEKK-1-containing beads were washed again and then incubated with SEK1(K-R) and [γ-32P]ATP (lanes 1 to 4). The reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography (upper panel). Amounts of GST-SEK1(K-R) protein in the kinase reactions were assessed by Coomassie blue staining (middle panel). The fold increase in GST-SEK1(K-R) phosphorylation is expressed as the mean ± the standard deviation of three independent experiments (bottom panel). (B) 293T cells were transiently transfected with c-Abl or c-Abl(K-R). After 48 h, lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-MEKK-1 (antibody 12851). The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by in vitro immune complex kinase assays with GST-SEK1(K-R) as the substrate (upper panel) and by immunoblotting with anti-MEKK-1 (lower panel). Two independent transfections are shown (lanes 1 and 3 and lanes 2 and 4).

FIG. 7.

Activation of MEKK-1 by c-Abl in vivo. (A) U-937 cells were treated with IR and harvested after 15 min. Lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-c-Abl. In vitro immune complex kinase assays were performed on the immunoprecipitates with GST-SEK1(K-R) as the substrate. The reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (B) Purified GST-SEK1(K-R) was incubated with [γ-32P]ATP in the presence or absence of recombinant c-Abl. Lane 1, purified c-Abl plus GST-SEK1(K-R); lane 2, c-Abl(K-R) protein plus GST-SEK1(K-R); lane 3, purified c-Abl plus GST-Crk(120-225). The reaction products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. (C) Embryo fibroblasts from wild-type (MEF) or c-Abl−/− mice were treated with 50 μM CDDP for 1 h. Lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-MEKK-1. The immunoprecipitates were assayed for phosphorylation of GST-SEK1(K-R).

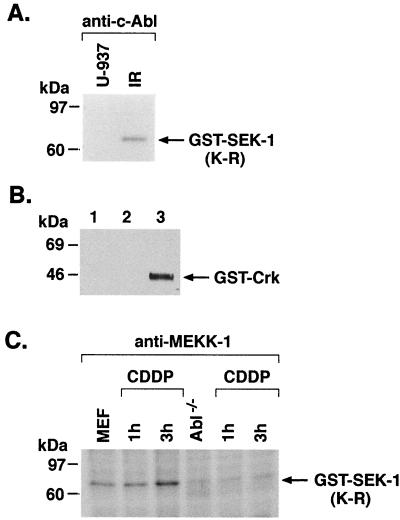

Induction of SAPK activity by c-Abl-mediated activation of MEKK-1.

Coupled kinase assays were performed to assess activation of MEKK-1 in the response to DNA damage. Lysates from control and IR-treated U-937 cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-c-Abl. After being washed, the immunoprecipitated proteins were incubated with purified GST-SEK1 in the presence of Mg2+ and ATP. The ability of activated GST-SEK1 to stimulate recombinant SAPK was determined by SAPK-catalyzed phosphorylation of GST-Jun(2-102). Anti-c-Abl immunoprecipitates from IR-treated, compared to untreated, cells exhibited increased phosphorylation of GST-Jun (Fig. 8A). GST-Jun phosphorylation was not induced if the anti-c-Abl immunoprecipitates containing MEKK-1 were incubated with purified, kinase-inactive SEK1(K-R), instead of SEK1, in the coupled kinase assays (Fig. 8B). Moreover, there was little if any GST-Jun phosphorylation when SEK1 or SAPK was not included in the assays (Fig. 8B). Taken together, these results support a model in which c-Abl activates SAPK by a MEKK-1-dependent mechanism. However, the present studies do not exclude the possibility that c-Abl stimulates the SAPK pathway by MEKK-1-independent mechanisms.

FIG. 8.

IR-induced activation of MEKK-1. (A) U-937 cells were treated with IR and harvested at 15 min. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-c-Abl (lanes 1 and 2) or rabbit anti-mouse (lanes 3 and 4) antibodies. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed for MEKK-1 activity in coupled-kinase assays. The bottom panel depicts the fold activation expressed as the mean ± the standard deviation of five independent experiments. (B) Lysates from IR-treated U-937 cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-c-Abl (lanes 1 to 5) or preimmune rabbit serum (not shown). The immunoprecipitates were analyzed for MEKK-1 activity by coupled-kinase assays. Lane 1, GST-SEK1 plus GST-SAPK plus GST-Jun; lane 2, GST-SEK1(K-R) plus GST-SAPK plus GST-Jun; lane 3, GST-SEK1 plus GST-Jun; lane 4, GST-SAPK plus GST-Jun; lane 5, GST-Jun. The fold activation is expressed as the mean ± the standard error (normalized to respective coupled-kinase assays performed with PIRS immunoprecipitates) of four independent experiments (bottom panel).

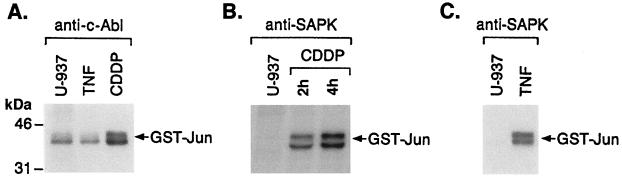

To determine whether other DNA-damaging agents activate SAPK by a c-Abl-mediated activation of MEKK-1, U-937 cells were treated with CDDP, and GST-Jun phosphorylation was assessed in anti-c-Abl immunoprecipitates by coupled-kinase assays. The results demonstrate that treatment of U-937 cells with CDDP is associated with a c-Abl-mediated increase in GST-Jun phosphorylation (Fig. 9A). The results also demonstrate that CDDP is a potent inducer of SAPK activity (Fig. 9B). In contrast to DNA-damaging agents, TNF induces SAPK activity by a c-Abl-independent mechanism (30, 48). In concert with these findings, anti-c-Abl immunoprecipitates from the TNF-treated cells failed to exhibit activation of recombinant SAPK in the coupled-kinase assays (Fig. 8A), although TNF exposure of cells was associated with activation of SAPK (Fig. 9C). These findings indicate that induction of SAPK by genotoxic stress is mediated at least in part by c-Abl-dependent activation of MEKK-1.

FIG. 9.

CDDP-induced activation of MEKK-1. (A) U-937 cells were treated with 50 μM CDDP for 1 h or 20 ng of TNF per ml for 10 min. Lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-c-Abl. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by coupled-kinase assays. (B) U-937 cells were treated with 50 μM CDDP and harvested after 2 and 4 h. Lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-SAPK and assayed for phosphorylation of GST-Jun(1-102). (C) Lysates from control and TNF-treated cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-SAPK, and in vitro immune complex kinase assays were performed using GST-Jun as substrate.

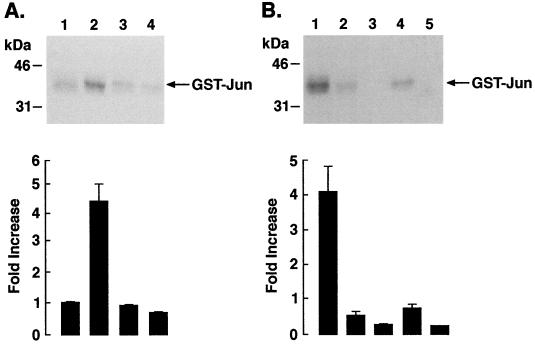

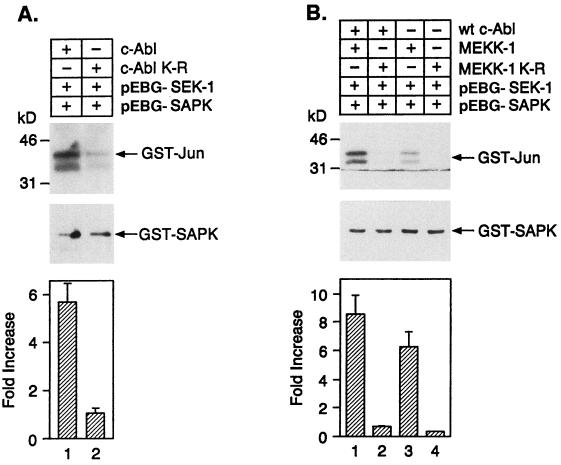

To further address the role of c-Abl in activation of SAPK, we transiently transfected 293T cells with wild-type c-Abl or c-Abl(K-R) in the presence of pEBG-SEK1 and pEBG-SAPK. The results demonstrate that transfection of c-Abl and not c-Abl(K-R) activates SAPK (Fig. 10A). To address the relationship between c-Abl and MEKK-1, we transiently transfected 293T cells with c-Abl in the presence or absence of MEKK-1 or MEKK-1(K-R) (76). The cells were also cotransfected with pEBG-SEK1 and pEBG-SAPK. Glutathione-agarose protein complexes were assayed for in vitro phosphorylation of GST-Jun. The results demonstrate that transfection of MEKK-1, but not MEKK-1 (K-R), stimulates SAPK activity and that cotransfection of c-Abl and MEKK-1 further induces SAPK activity (Fig. 10B). The results further demonstrate that expression of MEKK-1(K-R) blocks c-Abl-induced activation of SAPK (Fig. 10B). As a control, immunoblot analysis of total lysates with anti-GST demonstrated equal expression of SEK-1 and SAPK in the different experimental conditions (data not shown).

FIG. 10.

c-Abl is an upstream activator of MEKK-1. (A) 293T cells were cotransfected with SEK1, pEBG-SAPK, c-Abl, or c-Abl(K-R). After 48 h, glutathione-Sepharose protein precipitates were analyzed for GST-Jun(2-102) phosphorylation. (B) 293T cells were transiently transfected with SEK1 (lanes 1 to 4) and pEBG-SAPK (lanes 1 to 4) and equal amounts of the following: lane 1, c-Abl plus MEKK-1; lane 2, c-Abl plus MEKK-1(K-R); lane 3, MEKK-1; and lane 4, MEKK-1(K-R). After 48 h, glutathione-Sepharose protein precipitates were analyzed for GST-Jun(2-102) phosphorylation. Protein precipitates were also immunoblotted with anti-SAPK (middle panel). The fold activation (mean ± the standard error of five independent experiments) is shown in the bottom panel.

Previous studies have shown that dominant-negative mutants of the small GTPases Cdc42Hs and Rac1 block SAPK activation induced by inflammatory cytokines and tyrosine kinases (8, 66). In this context, TNF activates SAPK by a pathway involving the Pyk2 tyrosine kinase, Cdc42Hs, and Rac1 (8, 66). Importantly, overexpression of the Cdc42Hs or Rac1 dominant-negative mutants failed to block c-Abl-induced activation of SAPK (data not shown). Cdc42Hs and Rac1 function upstream to the protein kinase PAK1 (81) and MEKK-1 (8). Both PAK1 and MEKK-1 bind to Cdc42Hs and Rac1 (G. Fanger and G. Johnson, unpublished data). In concert with our results indicating the lack of involvement of Cdc42Hs and Rac1, the dominant-negative mutant of PAK1 failed to block activation of SAPK by c-Abl (data not shown). These findings provide support for a model in which MEKK-1 interacts with c-Abl in the response to DNA damage and with the Cdc42Hs-Rac1-PAK1 complex in the activation of SAPK by inflammatory cytokines.

DISCUSSION

DNA damage activates SAPK and c-jun gene expression.

Eukaryotic cells respond to DNA damage with cell cycle arrest, activation of DNA repair and, under certain circumstances, induction of apoptosis. The signals that determine cell fate, i.e., repair of DNA damage and survival or activation of cell death mechanisms, remain unclear. The exposure of diverse types of mammalian cells to IR and other DNA-damaging agents is associated with induction of SAPK activity (6, 7, 29–31, 69, 80). The findings that SAPK is also activated in cells treated with inflammatory cytokines, heat shock, anisomycin, and UV (9, 10, 35) have implicated the SAPK pathway in the response to a variety of cell stresses. However, the demonstration that SAPK is activated by mitogens (15, 46) and that certain SAPK isoforms are required for transformation and differentiation (24) have supported diverse functions for this kinase. The SAPK cascade induces the phosphorylation and activation of transcription factors that include c-Jun, Elk-1, and ATF-2 (45). The transactivation function of c-Jun is stimulated by SAPK-mediated phosphorylation of Ser-63 and Ser-73 sites (10, 12, 35). Binding of activated c-Jun to the AP-1 site in the c-jun gene promoter contributes to the activation of c-jun transcription (1, 25). In this context, induction of SAPK activity in the response to IR and other DNA-damaging agents is associated with activation of c-Jun and transcription of the c-jun gene (32, 54, 61). The functional significance of c-Jun activation and c-jun transcription to the DNA damage response is presumably related to the induction of later-response genes that determine cell fate. Activation of SAPK has been linked to the induction of apoptosis in the response to IR, TNF, and growth factor withdrawal (69, 73). Thus, DNA-damage-induced activation of SAPK appears to represent a signal that contributes at least in part to the apoptotic response.

Activation of c-Abl induces SAPK activity.

The mechanisms by which DNA damage is converted into intracellular signals that control cell behavior are largely unknown. Genetic studies have established that the DNA-PK complex is involved in the sensing of DNA double-strand breaks and in the repair of these lesions. The protein kinase catalytic subunit of DNA-PK (DNA-PKcs) is targeted to DNA breaks by association with the Ku DNA-binding heterodimer (Ku70-Ku80) (28). The DNA-PKcs interacts constitutively with c-Abl (28). Importantly, DNA-PKcs/Ku complexes phosphorylate and activate c-Abl in the presence of DNA (28). Other studies have supported a role for ATM like that found for DNA-PK, in which signals activated by DNA lesions are transduced to the c-Abl kinase as an effector of the DNA damage response (2, 60). The demonstration that Abl−/− cells exhibit a defective SAPK response to DNA-damaging agents has supported a role for c-Abl as an upstream effector of SAPK activation (30). Further support for involvement of c-Abl in SAPK signaling is provided by the finding that the introduction of c-Abl into Abl−/− cells restores DNA-damage-induced SAPK activation (30). By contrast, another study has reported that Abl−/− cells respond to IR with induction of SAPK (40). The apparent discrepancy in findings can be explained by the demonstration that activation of SAPK by IR and other DNA-damaging agents is c-Abl dependent in proliferating cells (30). However, confluent, growth-arrested cells fail to exhibit c-Abl-dependent activation of SAPK in the DNA damage response. These findings suggest that the SAPK response to IR and certain other genotoxic agents is regulated by c-Abl-dependent and -independent mechanisms that are dictated by the cell cycle or cell-cell interactions. In this context, recent studies have demonstrated that cell-cell and cell-matrix contacts play a critical role in the regulation of SAPK and p38 MAP kinases (36). Additional evidence in support of a role for c-Abl in the regulation of SAPK signaling has been derived from expression of constitutively activated forms of Abl. Overexpression of the kinase-active pGNG Abl deleted at the SH3 domain is associated with a pronounced induction of SAPK activity (29, 57). Other constitutively active forms, such as Bcr-Abl and v-Abl, have also been found to induce SAPK activity (50, 53). The present results demonstrate that the association of c-Abl with MEKK-1 is predominantly detectable in a nuclear complex. By contrast, activation of SAPK by oncogenic Abl variants is mediated primarily by cytoplasmic signals and MEKK-1-independent mechanisms. Taken together, these findings support a model in which c-Abl activation is an upstream effector of both nuclear and cytoplasmic SAPK signaling.

Interactions of c-Abl and MEKK-1.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the kinase domain of MEKK-1 interacts directly with Ras in a GTP-dependent manner (55). MEKK-1 also interacts with Rac and Cdc42 in the induction of SAPK by epidermal growth factor stimulation (15). In the response of cells to TNF, the germinal center kinase (GCK) interacts with MEKK-1 in coupling of the TNF receptor-associated factor 2 to SAPK activation (79). Also, in phorbol ester-induced monocytic differentiation, PKCβ interacts directly with MEKK-1 (24). In addition and in concert with functioning as an upstream effector of SAPK, the N-terminal, noncatalytic domain of MEKK-1 binds directly to SAPK isoforms (74). The present studies demonstrate that, while there is little, if any, constitutive association of c-Abl and MEKK-1 in cells, exposure to DNA-damaging agents induces the interaction. Overexpression of c-Abl and MEKK-1 by transient transfection also results in the formation of c-Abl–MEKK-1 complexes. Subcellular fractionation studies of IR-treated cells demonstrate that the interaction between c-Abl and MEKK-1 occurs predominantly in the nucleus. In addition, the finding that c-Abl phosphorylates MEKK-1 demonstrates that this interaction is direct. Other work has demonstrated that PKCβ phosphorylates and activates MEKK-1 in phorbol ester-treated cells (24). MEKK-1 is also phosphorylated by Pyk2 in the response of cells to TNF or UV light (13, 66). In the present study, c-Abl-mediated phosphorylation of MEKK-1 in vitro resulted in MEKK-1 activation. Our results also support a model in which the activation of c-Abl in the response of cells to DNA damage results in the induction of MEKK-1 activity. This model is further supported by the demonstration that DNA-damage-induced SAPK activity is dependent on c-Abl-mediated activation of MEKK-1.

Interaction of c-Abl and MEKK-1 in response to specific DNA lesions.

The demonstration that c-Abl interacts with MEKK-1 in the response to DNA damage positions c-Abl at a level of regulation comparable to that of the Ste20 kinase in S. cerevisiae. The HPK-1 and GCK serine-threonine kinases are mammalian homologs of Ste20 that function as upstream effectors of SAPK. HPK-1, a kinase found in hematopoietic precursors, activates SAPK by a mechanism involving the SH3-containing MLK-3 kinase (6, 7, 33, 65). HPK-1 interacts directly with the SH3 domain of c-Abl (33); however, it is not known if HPK-1 interacts with MEKK-1 or is required for c-Abl-dependent induction of SAPK activity. GCK is expressed in the germinal center B cells of lymphoid follicles and is activated by TNF (26, 49). The regulatory domain of GCK binds to both TRAF2 and MEKK-1 in coupling of the TNF receptor 1 to the SAPK pathway (79). TNF has no detectable effect on c-Abl activation, and TNF-induced SAPK activity is mediated by a c-Abl-independent mechanism (30, 48). These findings distinguish TNF- and DNA-damage-induced activation of SAPK by c-Abl-independent and -dependent mechanisms, respectively. UV-induced activation of SAPK involves induction of Pyk2 tyrosine kinase activity (13, 66). UV light damages DNA and also activates signaling at the cell membrane. The available evidence indicates that UV, like TNF, induces SAPK activity by a c-Abl-independent mechanism (30, 48). Activation of SAPK by the alkylating agent methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) is also mediated by a c-Abl-independent event (48, 72). In this regard, MMS activates Pyk2 and thereby activates SAPK (47). Thus, the available evidence indicates that UV light and MMS activate SAPK by Pyk2-dependent signals that originate at the cell membrane. The present findings support a distinct model in which genotoxic agents activate nuclear c-Abl and thereby activate the MEKK-1→SAPK pathway.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants CA75216 (S.K.) and CA55241 (D.K.) awarded by the National Cancer Institute, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

pEBG-SAPK, pEBG-SEK1, pEBG-SEK1(K-R) cDNAs were provided by Len Zon and Jim Woodgett. N17 Rac-1, N17 Cdc42Hs, and dominant-negative PAK-1 were provided by Jonathan Chernoff. MEKK-1 CF and the MEKK-1 CF(K-R) mutant were provided by Dennis Tempelton. Full-length HA–MEKK-1 was provided by Melanie Cobb. Wild-type c-Abl and kinase-inactive c-Abl(K-R) were provided by Charles Sawyers and Ruibao Ren. GST-SAPK, GST–SEK1(K-R), and GST-SEK1 were provided by Jim Woodgett.

REFERENCES

- 1.Angel P, Hattori K, Smeal T, Karin M. The jun proto-oncogene is positively autoregulated by its product, Jun/AP-1. Cell. 1988;55:875–885. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baskaran R, Wood L D, Whitaker L L, Xu Y, Barlow C, Canman C E, Morgan S E, Baltimore D, Wynshaw-Boris A, Kastan M B, Wang J Y J. Ataxia telangiectasia mutant protein activates c-abl tyrosine kinase in response to ionizing radiation. Nature. 1997;387:516–519. doi: 10.1038/387516a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Neriah Y, Bernards A, Paskind M, Daley G Q, Baltimore D. Alternative 5′ exons in c-abl mRNA. Cell. 1986;44:577–586. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90267-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blank J L, Gerwins P, Elliott E M, Sather S, Johnson G. Molecular cloning of mitogen-activated protein/ERK kinase kinases (MEKK) 2 and 3. Regulation of sequential phosphorylation pathways involving mitogen-activated protein kinase and c-Jun kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5361–5368. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen R H, Sarnecki C, Blenis J. Nuclear localization and regulation of erk- and rsk-encoded protein kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:915–927. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y-R, Meyer C F, Tan T-H. Persistent activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 (JNK1) in γ radiation-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:631–634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen Y-R, Wang X, Templeton D, Davis R J, Tan T-H. The role of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) in apoptosis induced by ultraviolet C and γ radiation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:31929–31936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.50.31929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coso O A, Chiariello M, Yu J, Teramoto H, Crespo P, Xu N, Miki T, Gutkind J S. The small GTP-binding proteins Rac1 and Cdc42 regulate the activity of the JNK/SAPK signaling pathway. Cell. 1995;81:1137–1146. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis R J. MAPKs: new JNK expands the group. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:470–473. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Derijard B, Hibi M, Wu I H, Barrett T, Su B, Deng T, Karin M, Davis R J. JNK1: a protein kinase stimulated by UV light and Ha-Ras that binds and phosphorylates the c-Jun activation domain. Cell. 1994;76:1025–1037. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derijard B, Raingeaud J, Barrett T, Wu I-H, Han J, Ulevitch R J, Davis R J. Independent human MAP-kinase signal transduction pathways defined by MEK and MKK isoforms. Science. 1995;267:682–685. doi: 10.1126/science.7839144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Devary Y, Gottlieb R A, Smeal T, Karin M. The mammalian ultraviolet response is triggered by activation of Src tyrosine kinases. Cell. 1992;71:1081–1091. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dikic I, Tokiwa G, Lev S, Courtneidge S A, Schlessinger J. A role for Pyk2 and Src in linking G-protein-coupled receptors with MAP kinase activation. Nature. 1996;383:547–550. doi: 10.1038/383547a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Errede B, Levin D E. A conserved kinase cascade for MAP kinase activation in yeast. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:254–260. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fanger G R, Johnson N L, Johnson G L. MEK kinases are regulated by EGF and selectively interact with Rac/Cdc42. EMBO J. 1997;16:4961–4972. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feller S, Ren R, Hanafusa H, Baltimore D. SH2 and SH3 domains as molecular adhesives: the interactions of Crk and Abl. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:453–458. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Georgiev O, Bourquin J P, Gstaiger M, Knoepfel L, Schaffner W, Hovens C. Two versatile eukaryotic vectors permitting epitope tagging, radiolabelling and nuclear localisation of expressed proteins. Gene. 1996;168:165–167. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00764-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goga A, Liu X, Hambuch T M, Senechal K, Major E, Berk A J, Witte O N, Sawyers C L. p53 dependent growth suppression by the c-Abl nuclear tyrosine kinase. Oncogene. 1995;11:791–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herskowitz I. MAP kinase pathways in yeast: for mating and more. Cell. 1995;80:187–197. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirai S, Izawa M, Osada S, Spyrou G, Ohno S. Activation of the JNK pathway by distantly related protein kinases, MEKK and MLK. Oncogene. 1996;12:641–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirano M, Osada S-I, Aoki T, Hirai S-I, Hosaka M, Inoue J-I, Ohno S. MEK kinase is involved in tumor necrosis factor α-induced NF-κB activation and degradation of IkBα. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13234–13238. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.13234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ichijo H, Nishida E, Irie K, ten Dijke P, Moriguchi T, Takagi M, Matsumoto K, Miyazono K, Gotoh Y. Induction of apoptosis by ASK1, a mammalian MAPKKK that activates SAPK/JNK and p38 signaling pathways. Science. 1997;275:90–94. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson N L, Gardner A M, Diener K M, Lange-Carter C A, Gleavy J, Jarpe M B, Minden A, Karin M, Zon L I, Johnson G L. Signal transduction pathways regulated by mitogen-activated/extracurricular response kinase kinase kinase induce cell death. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3229–3237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.3229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaneki M, Kharbanda S, Pandey P, Liou J-R, Stone R, Kufe D. Functional role for protein kinase Cβ as a regulator of stress-activated protein kinase activation and monocytic differentiation of myeloid leukemia cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:461–470. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karin M. The regulation of AP-1 activity by mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16483–16486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz P, Whalen G, Kehrl J H. Differential expression of a novel protein kinase in human B lymphocytes. Preferential localization in the germinal center. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16802–16809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kharbanda S, Bharti A, Pei D, Wang J, Pandey P, Ren R, Weichselbaum R, Walsh C T, Kufe D. The stress response to ionizing radiation involves c-Abl-dependent phosphorylation of SHPTP1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6898–6901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.6898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kharbanda S, Pandey P, Jin S, Inoue S, Bharti A, Yuan Z-M, Weichselbaum R, Weaver D, Kufe D. Functional interaction of DNA-PK and c-Abl in response to DNA damage. Nature. 1997;386:732–735. doi: 10.1038/386732a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kharbanda S, Pandey P, Ren R, Feller S, Mayer B, Zon L, Kufe D. c-Abl activation regulates induction of the SEK1/stress activated protein kinase pathway in the cellular response to 1-β-d-arabinofuranosylcytosine. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:30278–30281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.51.30278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kharbanda S, Ren R, Pandey P, Shafman T D, Feller S M, Weichselbaum R R, Kufe D W. Activation of the c-Abl tyrosine kinase in the stress response to DNA-damaging agents. Nature. 1995;376:785–788. doi: 10.1038/376785a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kharbanda S, Saleem A, Shafman T, Emoto Y, Weichselbaum R, Woodgett J, Avruch J, Kyriakis J, Kufe D. Ionizing radiation stimulates a Grb2-mediated association of the stress activated protein kinase with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18871–18874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kharbanda S, Sherman M L, Kufe D W. Transcriptional regulation of c-jun gene expression by arabinofuranosylcytosine in human myeloid leukemia cells. J Clin Investig. 1990;86:1517–1523. doi: 10.1172/JCI114870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiefer F, Tibbles L A, Anafi M, Janssen A, Zanke B W, Lassam N, Pawson T, Woodgett J R, Iscove N N. HPK1, a hematopoietic protein kinase activating the SAPK/JNK pathway. EMBO J. 1996;15:7013–7025. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kyriakis J M, Avruch J. Sounding the alarm: protein kinase cascades activated by stress and inflammation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24313–24316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kyriakis J M, Banerjee P, Nikolakaki E, Dai T, Rubie E A, Ahmad M F, Avruch J, Woodgett J R. The stress-activated protein kinase subfamily of c-Jun kinases. Nature. 1994;369:156–160. doi: 10.1038/369156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lallemand D, Ham J, Garbay S, Bakiri L, Traincard F, Jeannequin O, Pfarr C M, Yaniv M. Stress-activated protein kinases are negatively regulated by cell density. EMBO J. 1998;17:5615–5626. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lange-Carter C A, Johnson G L. Ras-dependent growth factor regulation of MEK kinase in PC12 cells. Science. 1994;265:1458–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.8073291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lange-Carter C A, Pleiman C M, Gardner A M, Blumer K J, Johnson G J. A divergence in the MAP kinase regulatory network defined by MEK kinase and Raf. Science. 1994;260:315–319. doi: 10.1126/science.8385802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin A, Minden A, Martinetto H, Claret F-X, Lange-Carter C, Mercurio F, Johnson G L, Karin M. Identification of a dual specificity kinase that activates the Jun kinases and p38-Mpk2. Science. 1995;268:286–290. doi: 10.1126/science.7716521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Z-G, Baskaran R, Lea-Chou E T, Wood L, Chen Y, Karin M, Wang J Y J. Three distinct signalling responses by murine fibroblasts to genotoxic stress. Nature. 1996;384:273–276. doi: 10.1038/384273a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu Z-G, Baskaran R, Lea-Chou E T, Wood L, Chen Y, Karin M, Wang J Y J. Three distinct signalling responses by murine fibroblasts to genotoxic stress. Nature. 1996;384:273–276. doi: 10.1038/384273a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manser E, Leung T, Salihuddin H, Zhao Z S, Lim L. A brain serine/threonine protein kinase activated by Cdc42 and Rac1. Nature. 1994;367:40–46. doi: 10.1038/367040a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marshall C J. Specificity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling: transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell. 1995;80:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mattioni T, Jackson P K, Bchini-Hooft van Huijsduijnen O, Picard D. Cell cycle arrest by tyrosine kinase Abl involves altered early mitogenic response. Oncogene. 1995;10:1325–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Minden A, Karin M. Regulation and function of the JNK subgroup of MAP kinases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1333:F85–104. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(97)00018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Minden A, Lin A, McMahon M, Lange-Carter C, Derijard B, Davis R J, Johnson G L, Karin M. Differential activation of ERK and JNK mitogen-activated protein kinases by Raf-1 and MEKK. Science. 1994;266:1719–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.7992057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pandey P, Avraham S, Place A, Kumar V, Majumder P, Cheng K, Nakazawa A, Saxena S, Kharbanda S. Bcl-xL blocks activation of related adhesion focal tyrosine kinase/proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 and stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase in the cellular response to methylmethane sulfonate. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:8618–8623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pandey P, Raingeaud J, Kaneki M, Weichselbaum R, Davis R, Kufe D, Kharbanda S. Activation of p38 MAP kinase by c-Abl-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23775–23779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.23775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pombo C M, Kehrl J H, Sanchez I, Katz P, Avruch J, Zon L I, Woodgett J R, Force T, Kyriakis J M. Activation of the SAPK pathway by the human STE20 homologue germinal centre kinase. Nature. 1995;377:750–754. doi: 10.1038/377750a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raitano A B, Halpern J R, Hambuch T M, Sawyers C L. The Bcr-Abl leukemia oncogene activates Jun kinase and requires Jun for transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11746–11750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rana A, Gallo K, Godowski P, Hirai S-I, Ohno S, Zon L, Kyriakis J M, Avruch J. The mixed lineage kinase SPRK phosphorylates and activates the stress-activated protein kinase activator, SEK-1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19025–19028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ren R, Ye Z-S, Baltimore D. Abl protein-tyrosine kinase selects the Crk adapter as a substrate using SH3-binding sites. Genes Dev. 1994;8:783–795. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.7.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Renshaw M W, Lea-Chou E, Wang J Y J. Rac is required for v-Abl tyrosine kinase to activate mitogenesis. Curr Biol. 1996;6:76–83. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00424-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rubin E, Kharbanda S, Gunji H, Kufe D. Activation of the c-jun protooncogene in human myeloid leukemia cells treated with etoposide. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;39:697–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Russell M, Lange-Carter C A, Johnson G L. Direct interaction between Ras and the kinase domain of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MEKK1) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:11757–11760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.11757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salmeron A, Ahmad T B, Carlile G W, Pappin D, Narsimhan R P, Ley S C. Activation of MEK-1 and SEK-1 by Tpl-2 proto-oncoprotein, a novel MAP kinase kinase kinase. EMBO J. 1996;15:817–826. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sanchez I, Hughes R T, Mayer B J, Yee K, Woodgett J R, Avruch J, Kyriakis J M, Zon L I. Role of SAPK/ERK kinase-1 in the stress-activated pathway regulating transcription factor c-Jun. Nature. 1994;372:794–798. doi: 10.1038/372794a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sawyers C L, McLaughlin J, Goga A, Havilik M, Witte O. The nuclear tyrosine kinase c-Abl negatively regulates cell growth. Cell. 1994;77:121–131. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90240-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schwartzberg P L, Stall A M, Hardin J D, Bowdish K S, Humaran T, Boast S, Harbison M L, Robertson E J, Goff S P. Mice homozygous for the ablTm1 mutation show poor viability and depletion of selected B and T cell populations. Cell. 1991;65:1165–1175. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90012-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shafman T, Khanna K K, Kedar P, Spring K, Kozlov S, Yen T, Hobson K, Gatei M, Zhang N, Watters D, Egerton M, Shiloh Y, Kharbanda S, Kufe D, Lavin M F. Interaction between ATM protein and c-Abl in response to DNA damage. Nature. 1997;387:520–523. doi: 10.1038/387520a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sherman M, Stone R, Datta R, Bernstein S, Kufe D. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of c-Jun expression during monocytic differentiation of human myeloid leukemic cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:3320–3323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sherman S E, Lippard S J. Structural aspects of platinum anticancer drug interaction with DNA. J Chem Rev. 1987;87:1153–1181. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takekawa M, Posas F, Saito H. A human homolog of the yeast Ssk2/Ssk22 MAP kinase kinase kinases, MTK1, mediates stress-induced activation of the p38 and JNK pathways. EMBO J. 1997;16:4973–4982. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.16.4973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Takekawa M, Saito H. A family of stress-inducible GADD45-like proteins mediate activation of the stress-responsive MTK1/MEKK4 MAPKKK. Cell. 1998;95:521–530. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tibbles L A, Ing Y L, Kiefer F, Chan J, Iscove N, Woodgett J R, Lassam N J. MLK-3 activates the SAPK/JNK and p38/RK pathways via SEK1 and MKK3/6. EMBO J. 1996;15:7026–7035. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tokiwa G, Dikic I, Lev S, Schlessinger J. Activation of Pyk2 by stress signals and coupling with JNK signaling pathway. Science. 1996;273:792–794. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5276.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tournier C, Whitmarsh A J, Cavanagh J, Barrett T, Davis R J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 is an activator of the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7337–7342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tybulewicz V L J, Crawford C E, Jackson P K, Bronson R T, Mulligan R C. Neonatal lethality and lymphopenia in mice with a homozygous disruption of the c-abl proto-oncogene. Cell. 1991;65:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90011-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Verheij M, Bose R, Lin X H, Yhao B, Jarvis W D, Grant S, Birrer M J, Szabo E, Zon L I, Kyriakis J M, Haimovitz-Friedman A, Fuks Z, Kolesnick R N. Requirement for ceramide-initiated SAPK/JNK signalling in stress-induced apoptosis. Nature. 1996;380:75–79. doi: 10.1038/380075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Widmann C, Gerwins P, Johnson N L, Jarpe M B, Johnson G L. MEK kinase 1, a substrate for DEVD-directed caspases, is involved in genotoxin-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2416–2429. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Widmann C, Gibson S, Johnson G L. Caspase-dependent cleavage of signaling proteins during apoptosis. A turn-off mechanism for anti-apoptotic signals. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7141–7147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.7141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wilhelm D, Bender K, Knebel A, Angel P. The level of intracellular glutathione is a key regulator for the induction of stress-activated signal transduction pathways including Jun N-terminal protein kinases and p38 kinase by alkylating agents. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4792–4800. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xia Z, Dickens M, Raingeaud J, Davis R J, Greenberg M E. Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science. 1995;270:1326–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xu S, Cobb M H. MEKK1 binds directly to the c-Jun N-terminal kinases/stress-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32056–32060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu S, Robbins D J, Christerson L B, English J M, Vanderbilt C A, Cobb M H. Cloning of rat MEK kinase 1 cDNA reveals an endogenous membrane-associated 195-kDa protein with a large regulatory domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5291–5295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yan M, Dai T, Deak J C, Kyriakis J M, Zon L I, Woodgett J R, Templeton D J. Activation of stress-activated protein kinase by MEKK1 phosphorylation of its activator SEK1. Nature. 1994;372:798–800. doi: 10.1038/372798a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yuan Z M, Huang Y, Ishiko T, Nakada S, Utsugisawa T, Kharbanda S, Sung P, Shinohara A, Weichselbaum R, Kufe D. Regulation of Rad51 function by c-Abl in response to DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3799–3802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.3799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yuan Z M, Huang Y, Whang Y, Sawyers C, Weichselbaum R, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. Role for the c-Abl tyrosine kinase in the growth arrest response to DNA damage. Nature. 1996;382:272–274. doi: 10.1038/382272a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yuasa T, Ohno S, Kehrl J H, Kyriakis J M. Tumor necrosis factor signaling to stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK)/Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38. Germinal center kinase couples TRAF2 to mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK kinase kinase 1 and SAPK while receptor interacting protein associates with a mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase upstream of MKK6 and p38. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22681–22692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zanke B W, Boudreau K, Rubie E, Winnett E, Tibbles L A, Zon L, Kyriakis J, Liu F-F, Woodgett J R. The stress-activated protein kinase pathway mediates cell death following injury induced by cis-platinum, UV irradiation or heat. Curr Biol. 1996;6:606–613. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00547-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang S, Han J, Sells M A, Chernoff J, Knaus U G, Ulevitch R J, Bokoch G M. Rho family GTPases regulate p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase through the downstream mediator Pak1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:23934–23936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.23934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]