Abstract

Australia experienced two public health emergencies in 2020 – the catastrophic bushfires and the global coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Whilst these were separate events, both have similar drivers arising from human pressures on the natural environment. Here we report on relative personal concerns of Australians in a survey implemented during the global COVID-19 pandemic.

The study design was a cross sectional online survey administered between 11 August and 11 November 2020. The setting was an Australia-wide online population involving 5483 individuals aged ≥18 residing in Australia. Recruitment occurred in two stages: unrestricted self-selected community sample through mainstream and social media (N = 4089); and purposeful sampling using an online panel company (N = 1055). The sample was predominantly female (N = 3187); mean age of 52.7 years; and approximately representative of adults in Australia for age, location, state and area disadvantage (IRSD quintiles). Climate change was very much a problem for 66.3% of the sample, while COVID-19 was ranked at the same level by only 25.3%. Three times as many participants reported that climate change was very much a problem than COVID-19, despite responding at a time when Australians were experiencing Stage 2 through 4 lockdowns. Demographic differences relating to relative personal concerns are discussed. Even in the midst of the uncertainty of a public health pandemic, Australians report that climate change is their most significant personal problem. Australia needs to apply an evidence-based public health approach to climate change, like it did for the pandemic, which will address the climate change concerns of Australians.

Keywords: Climate change, Public health, Coronavirus

1. Introduction

In 2020, Australians faced the catastrophic black summer bushfires and the global coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. The bushfires on Australia's eastern seaboard during the summer of 2019–20 were fuelled by ongoing drought, extreme heat, low rainfall and strong winds; conditions arising from climate change. Approximately 80% of Australians were either directly or indirectly impacted by the bushfires [1]. Shortly after the last fire was extinguished, Australia was struck with a second public health emergency with the spread of infections and subsequent pandemic arising from the zoonotic coronavirus disease (COVID-19). These were separate events, but with similar drivers arising from human pressures on the natural environment, and both generated large scale uncertainty and instability in nearly all parts of the Australian community [2].

Whilst studies consistently show the majority of Australians are very concerned about the impacts of climate change [3,4], there is limited peer reviewed evidence about the significance of climate change issues compared to other concerns. Furthermore, there is limited evidence arising from climate surveys that are nationally representative across age, location, and socio-economic profiles. This paper reports on one primary outcome measure from a nation-wide online survey on climate change and mental health in Australia, implemented during the global COVID-19 pandemic, and achieved a relatively large sample that is approximately representative of key socio-demographic characteristics of the Australian population.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Data and sample description

The representative sample included 5483 individuals aged 18+ residing in Australia in an online survey which provided data from 11th August to 11th November 2020. Over this period, residents in various Australian states and territories experienced a range of restrictions relating to the COVID-19 pandemic. These restrictions were particularly severe in Victoria following an increase in community transmission rates from 8th June, resulting in local and state-wide lockdowns from 20th June until 8th November [5].

We aimed to collect a sample from a representative sample of adults in the Australian population by age, gender, location (major cities vs not), state/territory and area disadvantage (using the Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage (IRSD) quintiles which is a general socio-economic index that summarises a range of information about the economic and social conditions of people and households within the area). To achieve this, participants were recruited in two stages: (1) unrestricted self-selection community sampling by the Australian public responding to survey links advertised via news (predominately the national broadcaster with a link to the survey on the ABC website, see below) and social media (N = 4089), and (2) purposive sampling using an online panel company that could target groups in their national panel to improve convergence of the overall survey sample with the key socio-demographic characteristics of the Australian population mentioned above, which resulted in a further (n = 1055). Participants completed an online survey that was advertised via several avenues including the national broadcasting as part of a national science week, as well as social media (Twitter, Facebook, Reddit). The survey took approximately ten minutes to complete. Participants were not provided with any incentive to take part, aside from the survey panel who received their usual reimbursement in accordance with ISO 26362 and industry requirements. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project No: 2020-224).

2.2. Measures

Participants completed demographic questions, including age, gender, and post-code. The key measure reported here is problem ranking or personal issues. To measure the perceived personal impact of climate change relative to other potential problems, participants were asked to identify how much of a personal problem a range of issues were from a provided list. The question and items were modelled on the Australia Talks National Survey [3]. The 2019 survey (N = 54,000) revealed that only four items out of a menu of 27 were considered somewhat or very much a problem for most individuals, including climate change (72%), saving for retirement (62%), health (56%), and ageing (50%). Consequently, we asked participants in the present study to respond to the following question: “How much of a problem are the following issues for you personally?”. Participants responded on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (not a problem) to 4 (very much a problem). We included the same items that were identified by most Australians from the 2019 survey, including climate change, retirement, health, and ageing. We added two items based on the expected impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, including COVID-19 and secure employment. Participants were not required to answer every item, since forced answer questions can have a significant impact on dropout rate and lower the quality of responses [6]

2.3. Data analysis

We analysed the data using descriptive statistics calculating frequency of responses to compare differences between demographic groups. From post-code data we derived participant's current state of residence, remoteness using the Modified Monash Model (MMM) [7] and socioeconomic disadvantage using the Index of Socioeconomic Disadvantage (IRSD) from the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) data [8]. The MMM is based on distance to high population density areas, from 1 (Metropolitan) to 7 (Very remote), while the IRSD is based on several indexes of social disadvantage including low-income, unemployment, and disability, resulting in a quintile score from 1 (Highest Disadvantage) to 5 (Lower Disadvantage). Respondent characteristics associated with response type were identified by multinomial logistic regression analysis and relative risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals provided. Relative risk ratios over 4.0 indicate large effect differences (i.e., one group has over 4 times the risk compared to another group); therefore, heat map shading will indicate relative risk ratios between 4.0 and 8.9 as light grey, and over 9.0 as dark grey.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

We achieved a sample approximately representative of adults in Australia for age, location (major cities vs not), state (Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland and other) and area disadvantage (IRSD quintiles). Although for gender, we achieved more women than men (60/40), see Table 1 . The sample had a mean age of 52.71 years (SD = 19.96). Table 1 summarises the main characteristics of participants, alongside comparative data on the Australia population values where available. This shows that women, those from 55 to 74 years of age, and from IRSD 1 and 5, were somewhat over-represented. In contrast, males, those from 18 to 24 years of age, and individuals from IRSD 3 and 4, were somewhat under-represented.

Table 1.

Demographics for the n = 5483 surveys

| Frequency | Percent | AUS pop. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | [9] | ||

| Male | 2,194 | 40.0 | 50 |

| Female | 3,187 | 58.1 | 50 |

| Non-Binary, trans, and gender diverse | 54 | 1.0 | |

| Prefer not to say or none of the above | 48 | 0.9 | |

| Age Group | [9] | ||

| 18–24 years | 281 | 5.1 | 9 |

| 25–34 years | 811 | 14.8 | 15 |

| 35–44 years | 707 | 12.9 | 13 |

| 45–54 years | 861 | 15.7 | 13 |

| 55–64 years | 1,181 | 21.5 | 12 |

| 65–74 years | 1,186 | 21.6 | 9 |

| 75+ years | 444 | 8.1 | 7 |

| Missing | 12 | 0.2 | |

| State | |||

| Victoria | 1,659 | 30.3 | 25 |

| New South Wales | 1,887 | 34.4 | 31 |

| Queensland | 921 | 16.8 | 20 |

| Other | 956 | 17.4 | 24 |

| Missing | 60 | 1.09 | |

| IRSD | [8] | ||

| 1 (Highest disadvantage) | 1,075 | 19.6 | 17 |

| 2 | 935 | 17.1 | 17 |

| 3 | 781 | 14.2 | 21 |

| 4 | 969 | 17.7 | 20 |

| 5 (Lowest disadvantage) | 1,641 | 29.9 | 25 |

| Missing | 82 | 1.5 | |

| Location – Remoteness | [10] | ||

| Major cities | 3,717 | 67.8 | 72 |

| Inner regional | 1,269 | 23.1 | 18 |

| Other | 417 | 7.6 | 10 |

| Missing | 80 | 1.5 |

3.2. Problem ranking

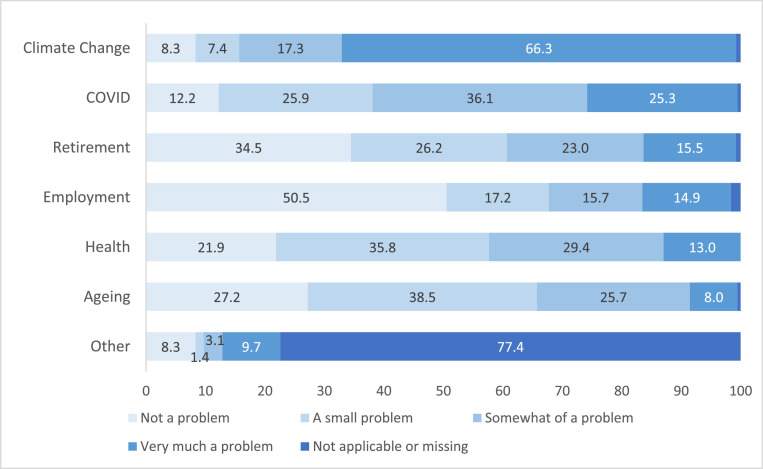

Fig. 1 shows relative concerns of respondents on a 6 item scale. Climate change was very much a problem for 66.3% of the sample, while COVID-19 was ranked at the same level by only 25.3%. Three times as many participants reported that climate change was very much a problem than COVID-19, despite responding at a time when Australians were experiencing stage 2 through 4 lockdowns (August – November 2020). In contrast, Retirement (15.4%), Employment (14.9%) and Health (13.0%) were very much a problem for significantly fewer respondents with Ageing being the least problem (8%). Notably, when very much a problem and somewhat of a problem are combined, COVID-19 was a personal problem for 61.4% of respondents. Likewise, 83.6% of respondents reported climate change was a personal problem.

Fig. 1.

Problem ranking.

Table 2 provides a detailed breakdown of climate change as a personal problem by key demographic characteristics. This shows that climate change was reported as very much a problem for more women (75.2%) than men (54.9%). With respect to age groups, people in the middle age ranges 34–44 (75.6%), 45–54 (73.5%) and 55–64 (72.3%) frequently indicated climate change as very much a problem for them personally. In younger age groups - 18–24 years (58.4%) and 25–34 years (58.1%) - and older age groups 65–74 years (65.1%) and 74+ (51.3%) this level of problem rating was less common but remained a majority position. Notably, the majority of all those sampled still reported climate change was very much a problem for them. Table 2 shows by state, Victorian respondents were more likely to report climate change as very much a problem (74.6%), with New South Wales lower at 65.9% and Queensland at 60.0%. For other states and territories of Australia, 62.26% of survey participants reported climate change being very much a problem. Table 2 demonstrates there was a fairly even distribution of climate change being very much a problem across major cities (67.4%), inner regional (66.6%) and other areas (outer regional, rural, remote) (63.9%). There was a significant difference between IRSD 1 (highest socio-economic disadvantage) with 44.07% reporting climate change being very much a problem than for all other IRSD categories with all being well above 50% (IRSD 2–63.5%, IRSD 3–71.4%, IRSD 4–77%, IRSD – 77.6%). Notably however, IRSD 1 reported that climate change was still ranked as somewhat a problem for 24.7%.

Table 3.

How much of this issue is a problem for you personally? COVID-19

(First row has frequencies and second row has column percentages. Note: Not all individuals answered every sub-item).

| (b) COVID-19 - how much of this issue is a problem for you personally? | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not a Problem | A Small Problem | Somewhat of a Problem | Very Much a Problem | Total | ||

| Total | 670 | 1420 | 1978 | 1386 | 5454 | |

| % | 12.3 | 26.0 | 36.3 | 25.4 | 100 | |

| Gender | Men | 350 | 599 | 701 | 531 | 2181 |

| % | 16.1 | 27.5 | 32.1 | 24.4 | 100 | |

| Women | 298 | 798 | 1242 | 833 | 3171 | |

| % | 9.4 | 25.2 | 39.2 | 26.3 | 100 | |

| Age | 18–24 years | 35 | 60 | 106 | 79 | 280 |

| % | 12.5 | 21.4 | 37.9 | 28.2 | 100 | |

| 25–34 years | 88 | 186 | 298 | 232 | 804 | |

| % | 10.9 | 23.13 | 37.1 | 28.9 | 100 | |

| 35–44 years | 60 | 199 | 267 | 180 | 706 | |

| % | 8.5 | 28.2 | 37.8 | 25.5 | 100 | |

| 45–54 years | 104 | 218 | 316 | 221 | 859 | |

| % | 12.1 | 25.4 | 36.8 | 25.7 | 100 | |

| 55–64 years | 152 | 305 | 420 | 301 | 1178 | |

| % | 12.9 | 25.9 | 35.7 | 25.6 | 100 | |

| 65–74 years | 147 | 324 | 427 | 281 | 1179 | |

| % | 12.5 | 27.5 | 36.2 | 23.8 | 100 | |

| 75+ years | 83 | 124 | 139 | 91 | 437 | |

| % | 19.0 | 28.4 | 31.8 | 20.8 | 100 | |

| State | Victoria | 121 | 385 | 654 | 497 | 1657 |

| % | 7.3 | 23.3 | 39.5 | 30.0 | 100 | |

| New South Wales | 203 | 480 | 686 | 503 | 1872 | |

| % | 10.8 | 25.6 | 36.7 | 26.9 | 100 | |

| Queensland | 171 | 274 | 302 | 167 | 914 | |

| % | 18.7 | 30.0 | 33.0 | 18.3 | 100 | |

| Other | 158 | 269 | 316 | 208 | 951 | |

| % | 16.6 | 28.3 | 33.2 | 21.9 | 100 | |

| Location | Major cities | 394 | 934 | 1386 | 980 | 3694 |

| % | 10.7 | 25.3 | 37.5 | 26.5 | 100 | |

| Inner regional | 178 | 342 | 434 | 311 | 1265 | |

| % | 14.1 | 27.0 | 34.3 | 24.6 | 100 | |

| Other | 79 | 128 | 130 | 78 | 415 | |

| % | 19.0 | 30.8 | 31.3 | 18.8 | 100 | |

| IRSD | Highest | 208 | 255 | 316 | 286 | 1065 |

| % | 19.5 | 23.9 | 29.7 | 26.9 | 100 | |

| 2 | 122 | 265 | 316 | 229 | 932 | |

| % | 13.1 | 28.4 | 33.9 | 24.6 | 100 | |

| 3 | 81 | 206 | 289 | 200 | 776 | |

| % | 10.4 | 26.6 | 37.2 | 25.8 | 100 | |

| 4 | 85 | 246 | 375 | 259 | 965 | |

| % | 8.8 | 25.5 | 38.9 | 26.8 | 100 | |

| Lowest | 155 | 430 | 654 | 395 | 1634 | |

| % | 9.5 | 26.3 | 40.0 | 24.2 | 100 | |

Table 2.

How much of this issue is a problem for you personally? Climate Change

(First row has frequencies and second row has column percentages. Note: Not all individuals answered every sub-item).

| (a) Climate Change - how much of this issue is a problem for you personally? | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not a Problem | A Small Problem | Somewhat of a Problem | Very Much a Problem | Total | ||

| Total | 456 | 403 | 946 | 3636 | 5441 | |

| % | 8.4 | 7.4 | 17.4 | 66.8 | 100 | |

| Gender | Men | 309 | 247 | 428 | 1199 | 2183 |

| % | 14.2 | 11.3 | 19.6 | 54.9 | 100 | |

| Women | 132 | 148 | 502 | 2374 | 3156 | |

| % | 4.2 | 4.7 | 15.9 | 75.2 | 100 | |

| Age | 18–24 years | 27 | 40 | 49 | 163 | 279 |

| % | 9.7 | 14.3 | 17.6 | 58.4 | 100 | |

| 25–34 years | 51 | 103 | 183 | 468 | 805 | |

| % | 6.3 | 12.8 | 22.7 | 58.1 | 100 | |

| 35–44 years | 31 | 40 | 101 | 533 | 705 | |

| % | 4.4 | 5.7 | 14.3 | 75.6 | 100 | |

| 45–54 years | 52 | 37 | 138 | 629 | 856 | |

| % | 6 | 4.3 | 16.1 | 73.5 | 100 | |

| 55–64 years | 89 | 57 | 178 | 846 | 1170 | |

| % | 7.6 | 4.9 | 15.2 | 72.3 | 100 | |

| 65–74 years | 134 | 71 | 207 | 767 | 1179 | |

| % | 11.4 | 6 | 17.6 | 65 | 100 | |

| 75+ years | 70 | 55 | 87 | 223 | 435 | |

| % | 16 | 12.6 | 20 | 51.3 | 100 | |

| State | Victoria | 81 | 78 | 259 | 1230 | 1648 |

| % | 4.9 | 4.7 | 15.7 | 74.6 | 100 | |

| New South Wales | 175 | 151 | 313 | 1232 | 1871 | |

| % | 9.4 | 8.1 | 16.7 | 65.9 | 100 | |

| Queensland | 110 | 89 | 167 | 550 | 916 | |

| % | 12 | 9.7 | 18.2 | 60 | 100 | |

| Other | 82 | 81 | 194 | 589 | 946 | |

| % | 8.7 | 8.6 | 20.5 | 62.3 | 100 | |

| Location | Major cities | 267 | 266 | 672 | 2488 | 3693 |

| % | 7.2 | 7.2 | 18.2 | 67.4 | 100 | |

| Inner regional | 134 | 85 | 200 | 835 | 1254 | |

| % | 10.7 | 6.8 | 16 | 66.6 | 100 | |

| Other | 44 | 46 | 60 | 265 | 415 | |

| % | 10.6 | 11.1 | 14.5 | 63.9 | 100 | |

| IRSD | Highest | 182 | 172 | 263 | 448 | 1065 |

| % | 17.1 | 16.2 | 24.7 | 42.1 | 100 | |

| 2 | 100 | 81 | 167 | 580 | 928 | |

| % | 10.8 | 8.7 | 18 | 62.5 | 100 | |

| 3 | 58 | 47 | 115 | 549 | 769 | |

| % | 7.5 | 6.1 | 15 | 71.4 | 100 | |

| 4 | 34 | 45 | 143 | 742 | 964 | |

| % | 3.5 | 4.7 | 14.8 | 77 | 100 | |

| Lowest | 71 | 51 | 244 | 1268 | 1634 | |

| % | 4.4 | 3.1 | 14.9 | 77.6 | 100 | |

Table 3 provides a detailed breakdown of COVID-19 as a personal problem by key demographic characteristics. This shows a consistently higher rate of COVID-19 being reported as somewhat of a problem vs. very much a problem across all demographic characteristics. Notably approximately a quarter of participants across all characteristics reported COVID-19 as a small problem. Differences between gender and age groups were not as distinct as those observed in the climate change data. However, COVID-19 concern was slightly higher (when combining very much a problem and somewhat of a problem) for younger age groups, lowest disadvantaged areas, major cities and inner regional areas as well as Victoria and New South Wales.

Table 4 shows the significant differences in the type of people reporting differential results to the question about the problem of climate change (Table 4a) and COVID-19 (Table 4b). These results confirm that for climate change, those reporting it as very much a problem response were significantly more likely to be women, aged 25–74 (especially those aged 35–44 followed by 45–54), those residing outside of major cities, in the lowest disadvantaged areas and in the three largest states (Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland). For the problem of COVID-19, the relative risk for a very much a problem response were significantly greater than not a problem for women, older people, those residing outside of major cities, in the lowest disadvantaged areas, and in the two largest states (Victoria and New South Wales). Table 4 confirms that the magnitude of concern differences were much greater climate change than for COVID-19.

Table 4.

Multinomial logistic regressions testing predictors of responses: relative risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals. (***Significantly different from 1, p < 0.001, **Significantly different from 1, p < 0.01, *Significantly different from 1, p < 0.05). Heat map shading shows the largest differences with relative risks ratios over 9.0 as dark grey, and between 4.0 and 8.9 as light grey.

| (a) Climate change. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How much of this issue is a problem for you personally? | ||||

| A Small Problem | Somewhat a Problem | Very_Much_a_Problem | ||

| vs | vs | vs | ||

| Not a Problem | Not a Problem | Not a Problem | ||

| Gender (women) | 1.12 | 3.8*** | 17.98*** | |

| (0.89–1.42) | (3.14–4.61) | (15.09–21.43) | ||

| Age | 18–24 (ref) | – | – | – |

| 25–34 years | 2.02*** | 3.59*** | 9.18*** | |

| (1.44–2.82) | (2.63–4.89) | (6.87–12.55) | ||

| 35–44 years | 1.29 | 3.26*** | 17.19*** | |

| (0.81–2.06) | (2.18–4.87) | (11.97–24.70) | ||

| 45–54 years | 0.71 | 2.65*** | 12.10*** | |

| (0.47–1.08) | (1.93–3.65) | (9.11–16.05) | ||

| 55–64 years | 0.64** | 2.00*** | 9.51*** | |

| (0.46–0.89) | (1.55–2.58) | (7.64–11.83) | ||

| 65–74 years | 0.53*** | 1.54*** | 5.72*** | |

| (0.40–0.71) | (1.24–2.58) | (4.76–6.88) | ||

| 75+ years | 0.79 | 1.24 | 3.19*** | |

| (0.55–1.11) | (0.91–1.70) | (2.43–4.17) | ||

| Location (outside major cities) | 0.74** | 1.46*** | 6.18*** | |

| (0.58–0.92) | (1.21–1.77) | (5.27–7.24) | ||

| IRSD quintile (highest to | 0.95 | 1.34*** | 1.98*** | |

| lowest disadvantage) | (0.91–1.00) | (1.29–1.40) | (1.91–2.06) | |

| Other (ref) | – | – | – | |

| Queensland | 0.81 | 1.52** | 5.00*** | |

| (0.61–1.07) | (1.19–1.93) | (4.07–6.14) | ||

| NSW | 0.86 | 1.79*** | 7.04*** | |

| (0.69–1.07) | (1.49–2.15) | (6.01–8.25) | ||

| Victoria | 0.96 | 3.20*** | 15.19*** | |

| (0.71–1.37) | (2.49–4.10) | (12.12–19.01) | ||

| (b) COVID-19 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How much of this issue is a problem for you personally? | ||||

| A Small Problem | Somewhat a Problem | Very_Much_a_Problem | ||

| vs | vs | vs | ||

| Not a Problem | Not a Problem | Not a Problem | ||

| Gender (women) | 2.68*** | 4.17*** | 2.80*** | |

| (2.34–3.06) | (3.67–4.73) | (2.45–3.19) | ||

| Age | 18–24 (ref) | – | – | – |

| 25–34 years | 2.11*** | 3.39*** | 2.64*** | |

| (1.64–2.72) | (2.67–4.30) | (2.06–3.37) | ||

| 35–44 years | 3.32*** | 4.45*** | 3.00*** | |

| (2.49–4.43) | (3.36–5.89) | (2.24–4.01) | ||

| 45–54 years | 2.10*** | 3.03*** | 2.12*** | |

| (1.66–2.65) | (2.43–3.79) | (1.68–2.68) | ||

| 55–64 years | 2.01*** | 2.76*** | 1.98*** | |

| (1.65–2.44) | (2.30–3.33) | (1.63–2.41) | ||

| 65–74 years | 2.20*** | 2.90*** | 1.91*** | |

| (1.81–2.68) | (2.41–3.50) | (1.57–2.33) | ||

| 75+ years | 1.49** | 1.67*** | 1.1 | |

| (1.13–1.97) | (1.28–2.20) | (0.81–1.48) | ||

| Location (outside major cities) | 1.83*** | 2.19*** | 1.51*** | |

| (1.57–2.13) | (1.89–2.54) | (1.29–1.77) | ||

| IRSD quintile (highest to | 1.28*** | 1.40*** | 1.27*** | |

| lowest disadvantage) | (1.24–1.32) | (1.37–1.44) | (1.23–1.30) | |

| Other (ref) | – | – | – | |

| Queensland | 1.60*** | 1.77*** | 0.98 | |

| (1.32–1.94) | (1.46–2.13) | (0.79–1.21) | ||

| NSW | 2.36*** | 3.38*** | 2.48*** | |

| (2.01–2.79) | (2.89–3.95) | (2.11–2.92) | ||

| Victoria | 3.18*** | 5.40*** | 4.11*** | |

| (2.59–3.90) | (4.45–6.56) | (3.37–5.01) | ||

4. Discussion

We report key findings from a nation-wide survey study in Australia which included an examination of levels of concern about climate change relative to other personal issues. Our results pertain to people reporting during the global COVID-19 pandemic and significant restrictions across Australia, in particular, the state of Victoria. Among respondents, and during the time of peak impact of the pandemic on Australians, climate significantly exceeded concern about the COVID-19 pandemic and all other listed concerns. This result is consistent with the findings of other surveys, such as the 2021 Edelman Trust Barometer (n = 1350 Australians, Oct – Nov 2020) that found that Australians were more fearful of climate change than being infected with COVID-19, and that the next biggest issue was the need to confront climate change. In the Edelman survey, 66% of participants reported they were concerned about climate change and 36% were fearful of the effects of climate change. Concern had grown since the previous survey with 32% increase in reporting that addressing climate change is more important now than ever before. Further, more than a third of people said they were more afraid of climate change than they were of contracting COVID-19 disease [4]. The findings of the current study were also consistent with ABC Talks 2019 national survey, which found climate change was the leading worry in that year, with 72% of respondents reporting that it would affect their lives [3]. This demonstrates again a consistent and ongoing concern across the Australian population about the impact of climate change on their lives.

The year 2020 was a time of great uncertainty and instability for many Australians [11]. The pandemic posed multiple threats to human health including risk of contracting the coronavirus disease, unemployment associated with business closures, and higher risk to population such as the aged (coronavirus disease impact on nursing homes and disproportionate burden of COVID-19 mortality for elderly) could arguably influence perceptions of immediate risk and vulnerability. However, the impact of government interventions such as economic stimulus payments (e.g. wage subsidy for employees and businesses via JobKeeper Payment) and the expansion of mental health and Telehealth services may have mitigated the perceived impact of COVID-19 on Australians [12]. Likewise, high levels of trust in Australian institutions, particularly healthcare, business and government [4], may play a role in lower perception of risk.

Whilst climate change is a concern for the vast majority of Australians, some Australian's are more concerned than others by virtue of demographic characteristic. We observe that climate change concern appears to be significantly more of a personal problem for women and people in the middle year age groups. The current study findings are consistent with research by the Climate Institute that finds women are particularly concerned about the impact of climate change (60% women compared to 47% males) [13]. With respect to age, the higher concern in the middle years may be associated with the experiences of parenthood, whereby assessment and perceptions of future risk are influenced by concern for security of children [14]. However, given previous research on young people aged 15–24 years in Victoria, Australia [15] and a study of eco-reproductive concerns among US younger adults (age 27 – 45 years) [16], we may have anticipated younger age ranges reporting higher rates of personal concern about climate change. The data also indicates there are high levels of concern across Australia but there is significantly higher levels of concern in Victoria and New South Wales. This observation is likely to be explained by the 2019–2020 catastrophic bushfires on the south eastern seaboard that directly impacted these two states. There also appears to be a social-economic gradient for climate change, being perceived as more of a problem for the most socio-economic advantaged to less of a problem for those most disadvantaged. A possible explanation for these findings is that individuals from more disadvantaged backgrounds may experience a greater range of problems, which means that climate change is less of concern in contrast. Additionally, higher education may be associated with greater awareness of environmental issues, which may be reflected in higher concern about climate change. These explanations are consistent with research that suggests social background, including tertiary education attainment and social class, are predictors of environmental behaviours and attitudes in Australia [17].

Even in the midst of the uncertainty of a public health pandemic, participants in an Australian study report that climate change is their most significant personal problem. The high level, widespread and persistent level of concern (regardless of social-demographic characteristics) identified in this paper suggests that climate change is a defining public health issue in Australia. Australian medical colleges and health organisations recognise the climate emergency and that health professionals have a critical role in managing and responding to the threats of climate change to health. What is absent in Australia is clear national government policy which communicates and responds to climate change as a public health issue [18].

By way of a strength the findings are based on a large sample of adults aged 18 years or older, capturing the views of people across Australia including people from a range of social-demographic profiles during a critical year for public health. Making for a limitation, the online recruitment of a self-selected community sample means some response bias is to be expected though the purposive secondary recruitment strategy will somewhat ameliorate this.

4.1. Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic is thought to be related to ecological disruption and exacerbated by climate change. Given that Australians continue to endure the cascading and multiple stressors of a changing climate, action on climate and the COVID-19 must form part of the way forward [18]. Australia needs to apply an evidence-based public health approach to recovery, like it did during the pandemic, that will address the climate change concerns of Australians whilst setting a clear pathway for a healthy and green recovery from COVID-19.

Author contribution statement

Rebecca Patrick Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing - original draft Conceptualisation, Methodology, Investigation Rhonda Garad Conceptualisation, Methodology, Writing – Reviewing & Editing Tristan Snell Investigation, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing Joanne Enticott Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis Graham Meadows Writing – reviewing and editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Dr Rebecca Patrick is President and Board member of the Climate and Health Alliance Australia.

Dr Rhonda Garad serves as an elected Local Government, Greens Councillor in Victoria, Australia.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Institute for Health Transformation, Deakin University, Australia

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100032.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Hughes L, Steffen W, Mullins G, et al. Climate Council of Australia Ltd.; 2020. Summer of crisis.https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Crisis-Summer-Report-200311.pdf Accessed July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong F, Capon T, McFarlane R. The Conversation; 2020. Coronavirus is a wake-up call: our war with the environment is leading to pandemics.https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-is-a-wake-up-call-our-war-with-the-environment-is-leading-to-pandemics-135023 Accessed July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Australian Broadcasting Corporation . 2020. What Australians really think about climate action.https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-02-05/australia-attitudes-climate-change-action-morrison-government/11878510 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edelman . 2021. Trust barometer 2021 Australia, research.https://www.edelman.com.au/trust-barometer-2021-australia [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health and Human Services . 2021. Media hub - coronavirus (COVID-19)https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/media-hub-coronavirus-disease-covid-19 Accessed May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Décieux J.P.P., Mergener A., Sischka P. Implementation of the forced answering option within online surveys: do higher item response rates come at the expense of participation and answer quality? Psihologija. 2015;48:311–326. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Australian Bureau of Statistics . 2019. Modified Monash model.https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/health-workforce/health-workforce-classifications/modified-monash-model Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Australian Bureau of Statistics . 2018. 2033.0.55.001 – census of population and housing: socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016.https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2033.0.55.001~2016~Main%20Features~SOCIO-ECONOMIC%20INDEXES%20FOR%20AREAS%20(SEIFA)%202016~1 Accessed Apr 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Australian Bureau of Statistics . 2019. 3101.0 – Australian demographic statistics, Jun 2019.https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/0/1cd2b1952afc5e7aca257298000f2e76#:~:text=At%2030%20June%202019%2C%20the,106.0%20males%20per%20100%20females Accessed Apr 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Australian Bureau of Statistics . 2019. Regional population: Statistics about the population and components of change (births, deaths, migration) for Australia's capital cities and regions.https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/regional-population/latest-release Accessed Apr 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blackdog Institute . 2020. Mental health ramifications of COVID-19: the Australian context.https://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/20200319_covid19-evidence-and-reccomendations.pdf Accessed Mar 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Australian Bureau of Statistics . 2021. 2021 household impacts of COVID-19 survey, insights into the prevalence and nature of impacts from COVID-19 on households in Australia.https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/household-impacts-covid-19-survey/latest-release Accessed Apr 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Climate Institute . JWS Research; NSW, Australia: 2014. Climate of the Nation 2014 Australian attitudes on climate change: are Australians climate dinosaurs?https://australiainstitute.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/2014-Climate-of-the-Nation-web.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekholm S, Olofsson A. Parenthood and worrying about climate change: the limitations of previous approaches. Risk Anal. 2017;37:305–314. doi: 10.1111/risa.12626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McDonald D, Havens C. Sustainability Victoria; 2019. Linking climate change and health impacts. Social research exploring awareness among Victorians and our healthcare professionals of the health effects of climate change. Research snapshot.https://www.sustainability.vic.gov.au/research-data-and-insights/research/climate-change/health-impacts-of-climate-change [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider-Mayerson M, Leong KL. Eco-reproductive concerns in the age of climate change. Clim Change. 2020;163:1007–1023. doi: 10.1007/s10584-020-02923-y. Accessed Dec 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tranter B. Social and political influences on environmentalism in Australia. J Sociol. 2021;50:331–348. doi: 10.1177/1440783312459102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patrick R, Armstrong F, Capon A, et al. Health promotion in the Anthropocene: the ecological determinants of health. Med J Aust. 2021;214(8 Suppl):S22–S26. doi: 10.1002/hpja.278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.