Abstract

Solid estimates describing the clinical course of SARS-CoV-2 infections are still lacking due to under-ascertainment of asymptomatic and mild-disease cases. In this work, we quantify age-specific probabilities of transitions between stages defining the natural history of SARS-CoV-2 infection from 1965 SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals identified in Italy between March and April 2020 among contacts of confirmed cases. Infected contacts of cases were confirmed via RT-PCR tests as part of contact tracing activities or retrospectively via IgG serological tests and followed-up for symptoms and clinical outcomes. In addition, we provide estimates of time intervals between key events defining the clinical progression of cases as obtained from a larger sample, consisting of 95,371 infections ascertained between February and July 2020. We found that being older than 60 years of age was associated with a 39.9% (95%CI: 36.2–43.6%) likelihood of developing respiratory symptoms or fever ≥ 37.5 °C after SARS-CoV-2 infection; the 22.3% (95%CI: 19.3–25.6%) of the infections in this age group required hospital care and the 1% (95%CI: 0.4–2.1%) were admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU). The corresponding proportions in individuals younger than 60 years were estimated at 27.9% (95%CI: 25.4–30.4%), 8.8% (95%CI: 7.3–10.5%) and 0.4% (95%CI: 0.1–0.9%), respectively. The infection fatality ratio (IFR) ranged from 0.2% (95%CI: 0.0–0.6%) in individuals younger than 60 years to 12.3% (95%CI: 6.9–19.7%) for those aged 80 years or more; the case fatality ratio (CFR) in these two age classes was 0.6% (95%CI: 0.1–2%) and 19.2% (95%CI: 10.9–30.1%), respectively. The median length of stay in hospital was 10 (IQR: 3–21) days; the length of stay in ICU was 11 (IQR: 6–19) days. The obtained estimates provide insights into the epidemiology of COVID-19 and could be instrumental to refine mathematical modeling work supporting public health decisions.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Risk outcomes, Disease burden, Epidemiological parameters, Contact tracing data

1. Introduction

Mathematical modeling has been one of the cornerstones in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Chinazzi et al., 2020, Ferguson et al., 2020, Guzzetta et al., 2021, Hellewell et al., 2020, Kucharski et al., 2020, Marziano et al., 2021, McCombs and Kadelka, 2020, Salje et al., 2020, Trentini et al., 2021, Vespignani et al., 2020, Wu et al., 2020a). To provide solid estimates, models need to be properly calibrated based on empirical evidence (Biggerstaff et al., 2020, He et al., 2020, Ma et al., 2020, Salje et al., 2020, Wood et al., 2021). While a lot of work has been done in this direction (Cereda et al., 2021, He et al., 2020, Hilton and Keeling, 2020, Ma et al., 2020, Park et al., 2020, Peiris et al., 2003, Riccardo et al., 2020, Zhang et al., 2020), metrics required to estimate the disease burden are still poorly quantified (Davies et al., 2020, Wu et al., 2020b). Difficulties in deriving these quantities are related to challenges in defining unbiased denominators (i.e., the infections) for computing different risk outcomes (e.g., deaths, severe disease, respiratory symptoms) upon infection (Poletti et al., 2020, Poletti et al., 2021, Verity et al., 2020). Indeed, as asymptomatic cases and infected individuals experiencing mild symptoms are, in general, more likely to remain undetected, quantitative estimates of the clinical course of the infection based only on confirmed cases could result in risk outcomes biased upward (Biggerstaff et al., 2020, Poletti et al., 2020, Poletti et al., 2021, Verity et al., 2020, Wu et al., 2020b).

In this work, we provide estimates of the probabilities of transition across the stages characterizing the clinical progression after SARS-CoV-2 infection, stratified by age and sex, as well as of the time delays between key events. To do this, we analyzed a sample of 1965 SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals who were contacts of confirmed cases. These individuals were identified irrespective of their symptoms as part of contact tracing activities carried out in Lombardy (Italy) over the period from March 10 to April 27, 2020. These individuals were daily monitored for symptoms for at least two weeks after exposure to a COVID-19 case and either tested for SARS-CoV-2 via PCR in real time or retrospectively via IgG serological assays; their clinical history was also recorded. In addition to this highly detailed sample, we relied on the epidemiological records of all the 95,371 SARS-CoV-2 PCR confirmed infections reported to the surveillance system between February and July 2020. This allowed us to provide a comprehensive quantitative assessment of all the main epidemiological parameters essential to model COVID-19 burden (see Fig. 1), thus laying the foundation for future COVID-19 modeling efforts.

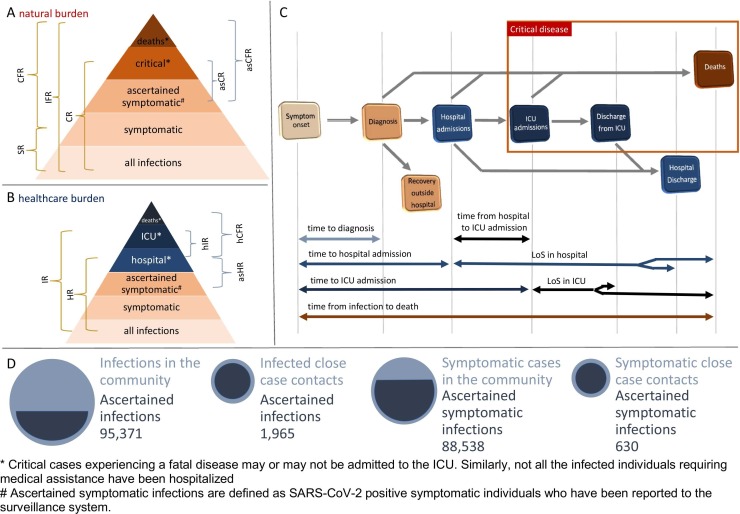

Fig. 1.

A Schematic representation of transition probabilities characterizing possible disease outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 infection. These include the symptomatic ratio (SR), the ratio of critical cases (CR), the case (CFR) and infection fatality ratios (IFR) and similar quantities that could be estimated using ascertained symptomatic infections (asCR, asCFR) as the set of exposed individuals. B Schematic representation of transition probabilities characterizing the hospital (HR) and ICU (IR) admission among infected individuals, and of similar quantities that could be estimated using ascertained symptomatic infections (asHR) or hospital patients (hCFR, hIR) as the set of exposed individuals. C Schematic representation of time to key events defining the temporal clinical progression of cases. D Schematic representation of the differences in the ascertainment rates associated with SARS-CoV-2 infections and symptomatic cases in the community and among close contacts of identified cases, with the latter representing individuals who were all tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection and daily monitored for symptoms during their quarantine or isolation period.

Estimates on age-specific risk outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 infection were validated against epidemiological records that have not been used to derive these quantities, leveraging on data from two serological surveys conducted in Italy (Stefanelli et al., 2021, Italian National Institute of Statistics ISTAT, 2020) and on the national cumulative incidence reported up to April 2021 (Istituto Superiore di Sanità,2021).

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

Lombardy represents the earliest and most affected region by the first COVID-19 epidemic wave experienced in Italy. Short after the detection of a first COVID-19 case on February 20, 2020, a ban of mass gatherings and the suspension of teaching in schools and universities was applied to the entire region. The interruption of non-essential productive activities and strict individual movement restrictions were imposed to the most affected municipalities. On March 8, 2020, after a rapid increase of cases, closure of all non-necessary businesses and industries and limitations of movements except in cases of necessity were extended to the entire region. A national lockdown was imposed on March 10, 2020. Suspended economic and social activities were gradually resumed between April 14 and May 18, 2020.

2.2. Data collection

Data analyzed here consists of the line list of SARS-CoV-2 laboratory confirmed infections ascertained in Lombardy between February 20 and July 16, 2020, and regularly updated by the regional public health authorities. Information retrieved from this dataset was complemented with contact-tracing records collected between March 10 and April 27 and with results of a serological survey targeting case contacts conducted between April 16 and June 15, 2020 (Poletti et al., 2020, Poletti et al., 2021). Data collection, integration, storage, and anonymization was managed by regional health authorities as part of surveillance activities and outbreak investigations aimed at controlling and mitigating the COVID-19 epidemic in Italy.

2.3. Definition of COVID-19 case

From February 21 to February 25, 2020, following the criteria initially defined by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), suspected COVID-19 cases were identified as:

-

1.

patients with acute respiratory tract infection OR sudden onset of at least one of the following: cough, fever, shortness of breath AND with no other aetiology that fully explains the clinical presentation AND at least one of these other conditions: a history of travel to or residence in China, OR patients among health care workers who has been working in an environment where severe acute respiratory infections of unknown etiology are being cared for;

-

2.

OR patients with any acute respiratory illness AND at least one of these other conditions: having been in close contact with a confirmed or probable COVID-19 case in the last 14 days prior to onset of symptoms, OR having visited or worked in a live animal market in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China in the last 14 days prior to onset of symptoms, OR having worked or attended a health care facility in the last 14 days prior to onset of symptoms where patients with hospital-associated COVID-19 have been reported.

Confirmed cases were defined as suspect cases testing positive with a specific real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay targeting multiple genes of SARS-CoV-2 (Cereda et al., 2021, Corman et al., 2020, Cohen and Kessel, 2020). From March 20, 2020 positivity to the nasopharyngeal swab was also granted for assays that tested a single gene. At any time, ascertained infections were defined as laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections, irrespective of clinical signs and symptoms. Inconclusive swabs were repeated to reach the diagnosis.

2.4. Ascertainment of infections among close case contacts

All ascertained SARS-CoV-2 infections were considered as potential index cases for further spread of SARS-CoV-2. Close contacts of these individuals were therefore identified through standard interviews of cases, informed of their possible exposure and quarantined within 24–48 h from a positive test result on the index case.

A close case contact was defined as a person living in the same household as a COVID-19 confirmed case; a person having had face-to-face interaction with a COVID-19 confirmed case within 2 m and for more than 15 min; a person who was in a closed environment (e.g. classroom, meeting room, hospital waiting room) with a COVID-19 confirmed case at a distance of less than 2 m for more than 15 min; a healthcare worker or other person providing direct care for a COVID-19 confirmed case, or laboratory workers handling specimens from a COVID-19 confirmed case without recommended personal protective equipment (PPE) or with a possible breach of PPE; a contact in an aircraft sitting within two seats (in any direction) of a COVID-19 confirmed case, travel companions or persons providing care, and crew members serving in the section of the aircraft where the index case was seated (passengers seated in the entire section or all passengers on the aircraft were considered close contacts of a confirmed case when severity of symptoms or movement of the case indicate more extensive exposure). Close case contacts were initially considered as contacts occurred between 14 days before and 14 days after the date of symptom onset of the index case. After March 20, 2020 the exposure period was shortened, ranging from 2 days before to 14 days after the symptom onset of the index case (World Health Organization, 2020). For individuals unable to sustain the contact tracing interview, close contacts were identified by their parents, relatives or their emergency contacts. From February 20 to February 25, 2020 all contacts of confirmed infections were tested with RT-PCR, irrespective of clinical symptoms. From February 26 onward, the traced contacts were tested with RT-PCR only in case of symptom onset.

However, on April 16, 2020, regional health authorities initiated an IgG serological survey of quarantined case contacts without history of testing against SARS-CoV-2 infection to retrospectively identify all asymptomatic positive contacts. The test used to detect SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies was the LIAISONR SARS-CoV-2 test (DiaSorin), employing magnetic beads coated with S1 & S2 antigens. The antigens used in the tests are expressed in human cells to achieve proper folding, oligomer formation, and glycosylation, providing material similar to the native spikes. The S1 and S2 proteins are both targets to neutralizing antibodies. The test provides the detection of neutralizing antibodies with 98.3% specificity and 94.4% sensitivity at 15 days from diagnosis. Performance analyses validating the accuracy of this serological test can be found in Bonelli et al. (2020). Serological test results were binary and communicated to tested participants, who were categorized as seropositive if they had developed IgG antibodies.

All case contacts, irrespectively to the presence of a laboratory diagnosis, were followed up for at least 14 days after exposure to an index case and required by national regulations to report symptoms to local public health authorities. Symptomatic cases were defined as infected subjects showing fever ≥ 37.5 °C or one of the following symptoms: dry cough, dyspnea, tachypnea, difficulty breathing, shortness of breath, sore throat, and chest pain or pressure. The definition of symptoms did not change throughout the period considered in this study. Clinical manifestations, admission to hospital or intensive care units and death among both ascertained infections and their close contacts were regularly updated by the regional health surveillance. In our study, individuals experiencing critical diseases were defined as positive patients who were either admitted to an intensive care unit or died with a diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Positive subjects who developed a critical disease are hereafter simply denoted as critical cases. Hospitalized patients with a laboratory confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection are denoted as ascertained cases admitted to hospital.

2.5. Sample selection for computing risk outcomes

A large fraction of case contacts remained untested against SARS-CoV-2 infection, due to difficulties in maintaining a high level of testing during the contact tracing operations and to the relatively low coverage of IgG serological screening conducted on traced contacts. As asymptomatic infections ascertained by surveillance systems are likely under-represented, we selected a subsample of SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals who were tested irrespectively from their symptoms. In particular, we considered infections ascertained among case contacts identified between March 10 and April 27, 2020 and belonging to clusters whose individuals were all tested and daily followed up for symptoms. A fraction of these individuals, mainly symptomatic ones, was tested by RT-PCR during contact-tracing activities. The remaining fraction was confirmed via IgG serological assays collected at least one month after exposure, thus allowing the identification of asymptomatic infections. This study design allowed us to minimize the risks of bias in the identification of infections when computing the proportion of SARS-CoV-2 infections developing symptoms and severe conditions. The resulting subsample consisted of 1965 positive subjects identified in 2458 clusters of 3947 close contacts. None of these records showed inconsistent data entries.

2.6. Statistical analysis

The aforementioned subsample of 1965 positive individuals who were identified as contacts of confirmed cases was analyzed to estimate the likelihood of developing respiratory symptoms or fever ≥ 37.5 °C (SR), of being admitted to a hospital (HR) and an ICU (IR), of developing critical disease (CR) and of dying after SARS-CoV-2 infection (IFR). The same sample was considered to estimate the case fatality ratio (CFR). Age and sex specific ratios were computed as crude percentages; 95% confidence intervals were computed by exact binomial tests. Logistic regression models were used to estimate the corresponding risk ratios (RRs) using the case age group, sex and month of identification (March or April) as model covariates. For the regression analysis, the following age-groups were considered: 0–59 years, 60–74 years, 75 + years.

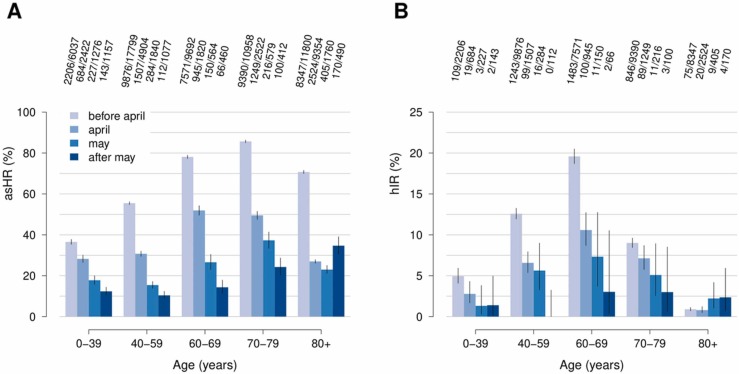

The entire sample of cases ascertained by regular surveillance activities (88,538 symptomatic individuals) was used to investigate temporal changes in the COVID-19 disease burden. In particular, we computed the age-specific crude percentage of ascertained cases admitted to hospital (asHR) and the percentage of ICU admissions among hospitalized cases (hIR) for four epidemic periods: before April, April, May and after May.

The same sample of cases was used to investigate the distribution of patients’ length of stay in hospital and in ICU, and the time interval between the following key events: from symptom onset to diagnosis, from symptom onset to hospital and/or ICU admission, from symptom onset to death, and from hospital to ICU admission. The time at diagnosis was defined as the time of testing observed for positive individuals. As 3855 out of 47,393 inpatients had inconsistent data entries on their temporal clinical progression after hospital admission, we excluded the corresponding data records when estimating time to key changes in patients’ status, such as hospital or ICU admission and discharge. Specifically, we excluded inpatients with a date of hospital admission or of death preceding the date of symptom onset, patients with a date of ICU admission or death preceding their hospitalization and patients with a negative length of stay in ICU or in hospital. Estimates for the hospital and ICU length of stay and the time between key events are provided for two epidemic periods, defined by considering the date of peak in the COVID-19 incidence experienced during the first epidemic wave in Lombardy, namely March 16, 2020. Cases were aggregated on the basis of the initial date of the considered interval. Negative binomial distributions were used to separately fit each time interval of interest. A negative binomial distribution was considered to better reflect the data characteristics: time lags expressed as integer values (delays measured in days), and a non-negligible proportion of patients with null delays (events occurring within the same day). Specifically, the negative binomial distribution was preferred over the Poisson, truncated normal, Gamma, Weibull, and Log-normal distributions, given that these alternatives were associated with a lower goodness of fit in terms of Akaike Information Criterion or they requested additional assumptions to fit the available records (e.g., the Gamma distribution is defined for strictly positive values only).

To assess the robustness of the estimated risk outcomes with respect to the change in the definition of close contact occurred on March 20, 2020, we investigated how the analyzed metrics would change when considering infections ascertained after that date only.

Since in our baseline analysis no assumptions were made on the time from the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 to hospital or to ICU admission, we also explored the effect of excluding patients reporting a delay from SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis to hospital or ICU admission greater than 30 days. Specifically, we analyzed the impact of this assumption on the estimated risk outcomes, the time intervals between key events, and the temporal changes in the probability of being admitted to hospital and ICU.

The statistical analysis was performed with the software R (version 3.6), using the “MASS” package. Fig. 1 provides a schematic representation of all metrics considered to quantify COVID-19 burden.

2.7. Validation of age-specific risk outcomes

The adopted approach was validated by applying our estimates for age-specific risk outcomes given SARS-CoV-2 infection to seroprevalence data available for Italy and comparing the obtained results with the age distribution of critical cases and deaths observed in Lombardy during the first pandemic wave and throughout Italy up to April 2021. Combining the estimated risk outcomes with a serological study conducted in a specific period would be inappropriate to estimate the absolute number of patients associated with different outcomes at a different time. However, the rationale of applying the estimated risk outcomes to independent seroprevalence data (collected at a different time) was to test whether the provided estimates could be used to reproduce the age profiles characterizing critical patients and deaths recorded over different periods.

Specifically, we computed the expected age distribution of critical cases C(a) and deaths D(a) as

and

where is the number of SARS-CoV-2 IgG positive individuals identified in the age class through serological surveys, CR(a) and IFR(a) represent our estimates for the probability of developing critical disease and the infection fatality ratio for the age class . was retrieved from: 1) a serological study conducted at the national level between May 25 and July 15, 2020 (Italian National Institute of Statistics ISTAT, 2020) and 2) results of an extensive serological screening applied between May 5 and May 15, 2020 to 77% of individuals residing in a high-incidence area (approximately 8000 residents) located in north-eastern Italy (Stefanelli et al., 2021). Resulting values for C(a) were compared to the age distribution of all critical cases recorded in Lombardy between February 20 and July 16, 2020. Values obtained for D(a) were compared to the age distribution of cumulative deaths recorded in Lombardy until July 16, 2020 and that observed at the national level between February 2020 and April 2021. The latter was obtained by using cumulative notification data stratified by age as provided by the Integrated National Surveillance System (NSS) (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, 2021). Validation of risk outcomes was carried by considering the following age-groups: 0–19, 20–39, 40–59, 60–69, 70 + years.

2.8. Ethical statement

Data collection and analysis were part of outbreak investigations during a public health emergency. Processing of COVID-19 data is necessary for reasons of public interest in the area of public health, such as protecting against serious cross-border threats to health or ensuring high standards of quality and safety of health care, and therefore exempted from institutional review board approval (Regulation EU 2016/679 GDPR).

3. Results

3.1. Sample description

We analyzed a total of 95,371 laboratory confirmed infections ascertained between February and July 2020. Of these, 88,538 (92.8%, median age 65 years, IQR: 50–81) reported respiratory symptoms or fever ≥ 37.5 °C, 47,393 (49.7%, median age 69 years, IQR: 55–80) were hospitalized, 19,020 (19.9%, median age 79 years, IQR: 70–86) developed critical disease (i.e., requiring ICU treatment or resulting in a fatal outcome) and 16,778 (17.6%, median age 81 years, IQR: 73–87) died with a diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 ( Table 1).

Table 1.

Estimated risk ratios of hospital admission, experiencing critical disease, and fatal outcome among symptomatic cases, disaggregated by age, sex, and period.

| Symptomatic cases | Hospitalized patients |

Critical cases |

Deaths |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Count | Risk ratio (95%CI) | Count | Risk ratio (95%CI) | Count | Risk ratio (95%CI) | |

| Age | |||||||

| ≥ 80 | 24,092 | 11,849 | Reference | 9325 | Reference | 9291 | Reference |

| 0–39 | 11,019 | 3361 | 0.54 (0.52–0.56) | 158 | 0.03 (0.03–0.04) | 38 | 0.01 (0.01–0.01) |

| 40–59 | 25,910 | 12,037 | 0.77 (0.75–0.79) | 1747 | 0.12 (0.12–0.13) | 733 | 0.05 (0.05–0.06) |

| 60–69 | 12,731 | 8917 | 1.22 (1.19–1.24) | 2642 | 0.35 (0.33–0.37) | 1872 | 0.24 (0.23–0.26) |

| 70–79 | 14,784 | 11,228 | 1.39 (1.37–1.41) | 5147 | 0.65 (0.63–0.68) | 4844 | 0.62 (0.60–0.64) |

| Unknown | 2 | 1 | 1.13 (0.06–1.99) | 1 | 0.86 (0.05–2.40) | 0a | – |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 46,234 | 19,318 | Reference | 7323 | Reference | 6804 | Reference |

| Male | 42,168 | 28,061 | 1.49 (1.47–1.51) | 11,682 | 1.87 (1.82–1.92) | 9966 | 1.78 (1.73–1.84) |

| Unknown | 136 | 14 | 0.20 (0.11–0.33) | 15 | 1.28 (0.75–1.97) | 8 | 0.84 (0.38–1.57) |

| Epidemic period | |||||||

| Before April | 56,288 | 37,391 | Reference | 14,473 | Reference | 12,530 | Reference |

| April | 21,022 | 6909 | 0.52 (0.51–0.54) | 3451 | 0.49 (0.47–0.51) | 3239 | 0.48 (0.46–0.50) |

| May | 6019 | 1282 | 0.36 (0.34–0.38) | 313 | 0.20 (0.18–0.22) | 276 | 0.19 (0.16–0.21) |

| After May | 3596 | 591 | 0.27 (0.25–0.29) | 44 | 0.06 (0.04–0.08) | 39 | 0.06 (0.04–0.08) |

| Unknown | 1613 | 1220 | 1.15 (1.11–1.18) | 739 | 1.56 (1.45–1.66) | 694 | 1.63 (1.51–1.76) |

RR and 95%CI were not computed for insufficiently large sample size.

By combining the regional line list of all ascertained infections with contact-tracing records collected between March 10 and April 27, 2020, we obtained a subsample of 1965 (median age 53 years, IQR: 32–64) contacts who resulted positive to SARS-CoV-2. Of these, 630 (32.1%, median age 57 years, IQR: 42.5–71) developed symptoms, 266 (13.5%, median age 64 years, IQR: 53.25–76) were hospitalized, 43 (2.2%, median age 76 years, IQR: 69–81) experienced critical disease conditions, 12 (0.6%, median age 68 years, IQR: 52.5 −72) were admitted to ICUs, and 35 (1.8%, median age 78 years, IQR: 74.5 – 82.5) resulted in a fatal outcome; 31 (1.6%, median age 79 years, IQR: 75–84) subjects died without being admitted to ICU; 4 (0.2%, median age 73.5 years, IQR: 71.25–75) died after an ICU admission ( Table 2).

Table 2.

Estimated crude percentages of symptomatic, hospitalized, ICU admitted, and critical cases among SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals who were identified as contacts of confirmed cases as well as estimated risk of death among positive individuals (i.e., infections) and symptomatic case (i.e., infected and symptomatic) individuals who were identified as contacts of confirmed cases. Results are disaggregated by age and sex.

| Positive contacts | Symptomatic cases |

Critical cases |

Deaths |

Hospitalized patients |

ICU-admitted patients |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Count | Proportion (95% CI) | Count | Proportion (95% CI) | Count | IFR (95% CI) | CFR (95% CI) | Count | Proportion (95% CI) | Count | Proportion (95% CI) | |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 0–14 | 219 | 39 | 17.8% (13–23.5%) | 0 | 0% (0–1.7%) | 0 | 0% (0–1.7%) | 0% (0–9%) | 4 | 1.8% (0.5–4.6%) | 0 | 0% (0–1.7%) |

| 15–19 | 22 | 6 | 27.3% (10.7–50.2%) | 0 | 0% (0–15.4%) | 0 | 0% (0–15.4%) | 0% (0–45.9%) | 2 | 9.1% (1.1–29.2%) | 0 | 0% (0–15.4%) |

| 20–39 | 377 | 99 | 26.3% (21.9–31%) | 2 | 0.5% (0.1–1.9%) | 0 | 0% (0–1%) | 0% (0–3.7%) | 18 | 4.8% (2.9–7.4%) | 2 | 0.5% (0.1–1.9%) |

| 40–59 | 662 | 213 | 32.2% (28.6–35.9%) | 5 | 0.8% (0.2–1.8%) | 2 | 0.3% (0–1.1%) | 0.9% (0.1–3.4%) | 89 | 13.4% (10.9–16.3%) | 3 | 0.5% (0.1–1.3%) |

| 60–69 | 331 | 106 | 32% (27–37.3%) | 5 | 1.5% (0.5–3.5%) | 3 | 0.9% (0.2–2.6%) | 2.8% (0.6–8%) | 49 | 14.8% (11.2–19.1%) | 3 | 0.9% (0.2–2.6%) |

| 70–79 | 240 | 94 | 39.2% (33–45.7%) | 17 | 7.1% (4.2–11.1%) | 16 | 6.7% (3.9–10.6%) | 17% (10.1–26.2%) | 59 | 24.6% (19.3–30.5%) | 4 | 1.7% (0.5–4.2%) |

| ≥ 80 | 114 | 73 | 64% (54.5–72.8%) | 14 | 12.3% (6.9–19.7%) | 14 | 12.3% (6.9–19.7%) | 19.2% (10.9–30.1%) | 45 | 39.5% (30.4–49.1%) | 0 | 0% (0–3.2%) |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female | 1111 | 365 | 32.9% (30.1–35.7%) | 19 | 1.7% (1–2.7%) | 16 | 1.4% (0.8–2.3%) | 4.4% (2.5–7%) | 139 | 12.5% (10.6–14.6%) | 5 | 0.5% (0.1–1%) |

| Male | 854 | 265 | 31% (27.9–34.3%) | 24 | 2.8% (1.8–4.2%) | 19 | 2.2% (1.3–3.5%) | 7.2% (4.4–11%) | 127 | 14.9% (12.6–17.4%) | 7 | 0.8% (0.3–1.7%) |

3.2. Metrics of COVID-19 burden

Age-specific transition probabilities characterizing the different outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 infection were estimated by considering infections occurred among close case contacts identified between March 10 and April 27, 2020. We found that the likelihood of developing respiratory symptoms or fever ≥ 37.5 °C after SARS-CoV-2 infection (SR) was 27.9% (95%CI: 25.4–30.4%) under 60 years of age and 39.9% (95%CI: 36.2–43.6%) above (see Table 2). We estimated that, in the first age-group, 8.8% (95%CI: 7.3–10.5%) of infected individuals required hospital care (HR) and 0.4% (95%CI: 0.1–0.9%) were admitted to ICU (IR); the corresponding proportions in positive individuals older than 60 years were 22.3% (95%CI: 19.3–25.6%) and 1% (95%CI: 0.4–2.1%), respectively. A significantly higher risk of developing critical disease after infection (CR) was found above 60 years of age when compared to younger individuals: 5.3% (95%CI: 3.7–7.2%) vs 0.5% (95%CI: 0.2–1.1%). The infection fatality ratio (IFR) ranged between 0.2% (95%CI: 0.0–0.6%) in subjects younger than 60 years to 12.3% (95%CI: 6.9–19.7%) for those aged 80 years or more. The case fatality ratio (CFR) in these two age groups was 0.6% (95%CI: 0.1–2%) and 19.2% (95%CI: 10.9–30.1%). Although the case fatality ratio was higher for subjects older than 80 years compared to cases aged 60–79 years (namely, 9.5%, 95%CI: 5.8–14.4%), a significantly lower proportion of ICU admissions was found for the oldest age segment: 1.2% (95%CI: 0.5–2.5%) vs 0% (95%CI: 0–3.2%). A detailed age-stratification of all these quantities is provided in Table 2. The strong age dependency in the risk of developing symptoms and most severe outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed by a statistical analysis based on generalized linear models applied to infected case contacts and accounting for possible confounding factors (see Table S1). The regression analysis also highlighted a significantly higher risk ratio (RR) of hospital admission (RR: 1.34, 95%CI: 1.07–1.67), critical disease (RR: 2.16, 95%CI: 1.17–3.98), and death (RR: 2.15, 95%CI: 1.08–4.27) for infected males as compared to females (Table S1).

Fig. 2 compares the age distributions of critical cases and deaths observed in Lombardy and in Italy with those resulting when applying our estimates for risk outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 infection to serological data available for the Italian context (Stefanelli et al., 2021, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, 2021, Italian National Institute of Statistics ISTAT, 2020). These findings highlight that, although estimates for CR and IFR were obtained from a relatively small sample of case contacts identified during the first pandemic phase (1965 subjects), they can well capture the age profiles characterizing the entire line list of critical patients and deaths recorded in Lombardy during the first COVID-19 wave and the age distribution of all deaths officially recorded across the entire Italian territory until 29 April 2021.

Fig. 2.

A Comparison between the age distributions of critical cases as obtained when applying estimated risk outcomes to available serological records with the one observed in Lombardy during the first COVID-19 wave. B Comparison between the age distributions of deaths as obtained when applying estimated risk outcomes to available serological records with the one observed in Lombardy during the first COVID-19 wave and the one associated to deaths occurred in Italy between February 2020 and April 2021, as reported by the Integrated National Surveillance System (NSS).

3.3. Temporal changes in the investigated risk metrics

Temporal changes in the risk of being admitted to hospital and ICUs were explored by analyzing records of the complete list of 88,538 symptomatic cases ascertained between February and July 2020 (see Table 1 and Table S2 for sample description). The analyzed data includes inpatients with inconsistencies in dates defining the temporal clinical progression after hospitalization. Crude ratios computed from ascertained symptomatic cases should be carefully interpreted because of possible biases due to higher ascertainment rates among more severe cases. However, the analysis of this large sample highlighted an increase of admission rates at different levels of intensity of care among the elderly ( Fig. 3). In particular, hospital admission ratios among ascertained symptomatic cases (asHR) aged more than 80 years increased from the 26.4% (95%CI: 25.5–27.2%) observed between April and May to 34.7% (95%CI: 30.5–39.1%) afterwards. Similarly, the ICU admission ratio among patients hospitalized (hIR) in this age group raised from the 0.9% (95%CI: 0.7–1.1%) observed between March and April to 2.3% (95%CI: 1.2–3.8%) afterwards.

Fig. 3.

A Age-specific case hospital admission ratios among ascertained symptomatic cases (asHR). B Age-specific ICU admission ratios among hospitalized cases (hIR). Bars of different colors represent crude percentages observed across different epidemic periods; vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals computed by exact binomial tests. Numbers shown in each panel represent the age-specific number of events observed in the data among exposed COVID-19 cases.

3.4. Time to key events

Time delays from symptom onset to diagnosis and death were investigated by analyzing all the 88,538 symptomatic infections ascertained in Lombardy between February and July 2020. The temporal clinical progression of inpatients was investigated by analyzing 43,538 hospitalized cases ( Table 3), after having excluded 3855 out of the 47,393 available inpatient records because of inconsistent dates of hospital or ICU admission/discharge. We estimated that, overall, the median delay between symptom onset and diagnosis was 4 (IQR: 1–10) days. The median time from symptom onset to death was 12 (IQR: 7–21) days. Hospitalization of cases occurred 5 (IQR: 2–9) days after patients’ symptom onset; admission to ICU occurred 10 (IQR: 6–15) days after symptom onset. The median time between hospital and ICU admission was 3 (IQR: 0–6) days. The median hospital length of stay was 10 (IQR: 3–21) days, while the median length of stay in ICU was 11 (IQR: 6–19) days. A negative binomial distribution was used to separately fit each time interval of interest (Fig. S1).

Table 3.

Time intervals between key events as estimated from laboratory confirmed infections ascertained in Lombardy between February 20 and July 16, 2020.

| Median days (IQR) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time between symptom onset and diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 | Time between symptom onset and death | Time between symptom onset and hospital admission | Time between symptom onset and ICU admission | Time between hospital and ICU admission | Hospital length of stay | ICU length of stay | |

| Age | |||||||

| 0–39 | 3 (0–11) | 16 (6–27) | 4 (1–8) | 8 (4–11) | 1 (0–5) | 4 (0–10) | 9 (4–15.75) |

| 40–59 | 5 (1–11) | 15 (9–26) | 6 (2–10) | 10 (6–13) | 2 (0–6) | 9 (1–18) | 11 (6–19) |

| 60–69 | 5 (1–10) | 16 (9–25) | 6 (2–10) | 11 (7–15) | 3 (0–7) | 13 (6–24) | 12 (6–20) |

| 70–79 | 5 (1–9) | 12 (7–20) | 5 (2–9) | 10 (6–16) | 4 (1–7) | 12 (5–24) | 10 (5–18) |

| ≥ 80 | 3 (0–8) | 11 (6–19) | 4 (1–8) | 9 (4–23) | 2 (0–11.5) | 10 (4–24) | 5 (3–10.75) |

| Unknown | 13 (9.5–16.5) | 0 (0–0) | 8 (8–8) | 8 (8–8) | 0 (0–0) | 14 (14–14) | 14 (14–14) |

| Epidemic period | |||||||

| Before 16 March | 7 (3–12) | 13 (8–21) | 7 (3–10) | 10 (7–15) | 3 (0–6) | 10 (3–21) | 11 (6–19) |

| After 16 March | 2 (0–7) | 11 (6–20) | 3 (1–7) | 9.5 (5–14) | 4 (0–8) | 10 (3–23) | 11 (6–20) |

| Unknown | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–4) | 8 (2–20) | 6 (3.75–13) |

| Overall | 4 (1–10) | 12 (7–21) | 5 (2–9) | 10 (6–15) | 3 (0–6) | 10 (3–21) | 11 (6–19) |

| Estimates obtained by fitting a negative binomial distribution to observed data | |||||||

| overdispersion | 0.445 | 1.638 | 0.831 | 2.036 | 0.57 | 0.746 | 1.517 |

| mean | 9.753 | 16.105 | 7.385 | 12.159 | 5.309 | 15.54 | 14.614 |

When looking at these variables across different ages, we found a shorter delay between symptom onset and death in individuals older than 70 years (11–12 days vs 15–16 days at younger ages) and a shorter length of stay in ICU among patients aged 80 years or more (5 days vs 9–12 days at younger ages). We separately analyzed these quantities for cases who developed symptoms before and after March 16, 2020, corresponding to the peak in the number of hospitalized patients in Lombardy (Fig. S2). We found a marked decrease in the time required to both diagnose and hospitalize COVID-19 patients after this date (from 7 to 2 days and from 7 to 3 days, respectively, Table 3). It is worth noting that the lag between the time of the test and the time when the test result became available remained approximately constant during the entire period considered (ranging from 2 to 4 days). Detailed estimates obtained on the temporal clinical progression of COVID-19 cases are reported in Table 3.

By considering only positive contacts ascertained after March 20, 2020, when the definition of close contact changed, a lower likelihood of experiencing critical disease and death for positive individuals older than 70 years and females was found (see Table S3). Such differences may be linked to the enhancement of the tracing and treatment procedures during the first month of the COVID-19 epidemic, which may include a faster detection and diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infections and shorter time lags between diagnosis and hospitalization of severe patients. On the other hand, our estimates did not change when excluding patients with a delay from SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis to hospital or ICU admission greater than 30 days (Tables S4 and S5, and Fig. S3).

4. Discussion and conclusions

In this work, we provided a comprehensive assessment of the parameters regulating COVID-19 burden and natural history. The proposed analysis leveraged data on the infections ascertained in Italy between February and July 2020 to estimate the time between key events and the age- and sex- specific stage-to-stage transition probabilities characterizing the clinical progression of COVID-19.

Previous studies have highlighted that a significant share of SARS-CoV-2 infections is represented by symptom-free subjects and by individuals developing mild disease (Emery et al., 2020, Lavezzo et al., 2020, Poletti et al., 2021, Salje et al., 2020, Wu et al., 2020b). Therefore, using the number of notified or confirmed COVID-19 cases as an approximation of the number of infections would likely lead to overestimate the risk of disease and severe outcomes, undermining the comparability and generalizability of the obtained results. An illustrative example of the huge uncertainty caused by this phenomenon is provided by the high variability around the available estimates of the proportion of symptomatic infections, ranging from 3% to 87% (Buitrago-Garcia et al., 2020, Byambasuren et al., 2020, Emery et al., 2020, Nikolai et al., 2020, Oran and Topol, 2020, Poletti et al., 2021). To reduce potential biases in the identification of SARS-CoV-2 infections, we estimated different risk ratios based on a sample of SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals who were identified as contacts of confirmed cases and tested irrespectively of their symptoms. A larger sample, consisting of all notified symptomatic cases, was used only to estimate the time to key events describing the clinical progression of cases and to highlight temporal changes in the risk of hospitalization and ICU admission.

Our results confirmed findings from other studies on the strong age gradient in the likelihood of developing symptoms, critical disease, and death after infection (Onder et al., 2020, Poletti et al., 2020, Salje et al., 2020, Verity et al., 2020, Yang et al., 2020). The estimated proportion of symptomatic cases among SARS-CoV-2 infections is within the range of estimates obtained in previous studies (Buitrago-Garcia et al., 2020, Nikolai et al., 2020) and particularly close to findings obtained in Emery et al. (2020). Our estimated CFR was lower compared to the one obtained in a previous study on other Italian data (Onder et al., 2020), but slightly higher than those observed in other countries (Fu et al., 2020, Li et al., 2020, Verity et al., 2020, Yang et al., 2020). The estimated age-profile of the IFR closely resembles Verity et al. (2020). However, our aggregate (population-level) estimate of the IFR is generally higher than those obtained in other studies (O’Driscoll et al., 2021, Perez-Saez et al., 2020, Salje et al., 2020, Verity et al., 2020). Such difference can be due to a variety of factors. First, Italy is one of the oldest countries in the world (average age: 45.7 years (Italian National Institute of Statistics, 2021)). Second, there may be between-country differences in the age distribution of SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals. Third, there are differences in the definition of COVID-19 death. In fact, in Italy, deaths occurring among SARS-CoV-2 positive subjects are classified as COVID-19-related deaths regardless of other conditions that might have caused the observed fatal outcome (Onder et al., 2020). This has possibly led to overestimate the number of deaths caused by SARS-CoV-2, especially in the oldest segment of the population. Nonetheless, in Italy, a laboratory confirmation for SARS-CoV-2 infection is required to define a COVID-19 death. COVID-19 deaths are mainly represented by cases ascertained before their decease, while only few cases are ascertained post-mortem. In the subsample of positive case contacts used to estimate the IFR and CFR, all deaths were confirmed before their decease.

The proportion of hospitalized patients among positive individuals older than 60 years was almost double than that observed in France (Salje et al., 2020). On the other hand, the proportion of ICU admissions and deaths among hospitalized cases was markedly lower in our sample (4.5% and 12.4% vs 19% and 18.1%, respectively), and we found a strong temporal decreasing pattern in the risk of hospital admission among ascertained symptomatic cases. This suggests that hospitalization criteria might have been highly heterogeneous across different countries and may also greatly vary over time.

The estimated time from symptom onset to laboratory diagnosis well compares with estimates obtained from Belgian patients (Faes et al., 2020). Although in line with previous findings from Belgium (Faes et al., 2020), the time from symptom onset to hospital admission we found is markedly shorter than those observed in France, in China, and in the US (Bhatraju et al., 2020, Salje et al., 2020, Zhou et al., 2020). This may be the consequence of the higher proportion of severe cases observed in Italy compared to other countries, which strictly relates to the older age-structure characterizing this country. This hypothesis is partially supported by the shorter hospital length of stay and by the longer length of stay in ICU we found, compared to estimates from China (Guan et al., 2020, Zhou et al., 2020).

The relatively low ICU admission ratio we observed among the elderly was already highlighted in previous studies (Grasselli et al., 2020, Salje et al., 2020). However, our findings clearly show that hospitalized patients aged 80 years or older faced the highest risk of fatal outcome, but also the lowest likelihood of being admitted to ICU. The increased ratio of ICU admission among inpatients we found for this age group after April 2020 suggests that elective ICU admission has been initially adopted in Lombardy due to saturation of healthcare resources. The lower delay between symptom onset and admission to hospital observed after March 16, 2020, and the progressive temporal increase in the likelihood of hospital admission among older patients strongly suggest that reducing the pressure on the regional healthcare system markedly improved its capacity to rapidly identify and treat severe patients (Trentini et al., 2021) (see Fig. S2).

Our estimates of the risk ratios of hospital and ICU admissions after infection should be interpreted cautiously. In fact, rather than being purely biological features, such quantities strongly depend on the available healthcare resources, on the temporal changes in the number of patients seeking care, and on the protocols adopted to face a brisk upsurge of COVID-19 cases. Consequently, using these estimates to investigate the healthcare burden over different phases of the pandemic could produce misleading results. Additionally, due to temporal changes in the ascertainment rates of infections, we were not able to quantify the reduced risk of severe outcomes determined by timely detection, diagnosis and treatment of cases, nor to evaluate the role played by the progressive enhancement in the treatment procedures in reducing the risk of disease. A further limitation affecting our study is the lack of data to disentangle the role played by patients’ comorbidities in shaping the risk of severe diseases. Finally, it is important to stress that estimates reported here are associated with the historical and dominant variant of the virus that circulated during 2020, in the absence of vaccination. As such, estimated metrics may not apply to new emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants (Davies et al., 2021, Kiem et al., 2020, Volz et al., 2021) and may not reflect the risk of developing COVID-19 disease among infections occurring among vaccinated individuals.

Although disease parameters may be specific for the time and place of the data collection (northern Italy’s first COVID-19 wave), we showed that estimated risk outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 infection well compare with data associated with broader time periods and geographical locations.

Metrics defining the natural history of SARS-CoV-2 infection were estimated from positive individuals who belonged to clusters of contacts, who were all tested and daily followed up for symptoms and for severe outcomes. A fraction of these individuals, mainly consisting of symptomatic ones, was tested via RT-PCR during contact-tracing activities. The remaining case contacts were retrospectively tested via IgG serological assays collected at least one month after exposure, thus allowing the identification of asymptomatic infections as well. Despite the heterogeneous testing procedure, we believe that the strengths of this study design rely on: (1) the minimization of the risks of bias in the identification of infections (contacts were identified and tested independently of their clinical signs), and (2) the daily follow-up of the infections for symptoms and critical disease in the weeks following the exposure to a confirmed infection. Therefore, the analyzed sample does not suffer the usual limitations of surveillance data (i.e., underestimation of asymptomatic individuals) and of serological data (i.e., lack of longitudinal records about the clinical history of study participants). Despite the aforementioned limitations, the provided metrics can be instrumental to refine model estimates. In particular, our findings could be used to assist the design and evaluation of forthcoming vaccination efforts and the development of appropriate strategies to control the COVID-19 pandemic until a sufficiently large proportion of the population has become immune.

Funding

AZ, MM, FT, VM, GG, PP and SM acknowledge funding from EU grant 874850 MOOD (catalogued as MOOD 016). AM acknowledges funding support from the Fondazione Romeo and Enrica Invernizzi to the Bocconi Covid Crisis Lab. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

PP, MA, SM conceived and designed the study. AZ and MG performed the analysis. MT and DC collected data. AZ, MG, MT, DC, FT, RP and PP collated linked epidemiological data. MT, DC verified all data. AZ, MG and PP wrote the first draft. All authors contributed to data interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing Interest

MA has received research funding from Seqirus. The funding is not related to COVID-19. All other authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.epidem.2021.100530.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material.

.

References

- Bhatraju P.K., Ghassemieh B.J., Nichols M., Kim R., Jerome K.R., Nalla A.K., Greninger A.L., Pipavath S., Wurfel M.M., Evans L., Kritek P.A., West T.E., Luks A., Gerbino A., Dale C.R., Goldman J.D., O’Mahony S., Mikacenic C. Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region - case series. New Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(21):2012–2022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggerstaff M., Cowling B.J., Cucunubá Z.M., Dinh L., Ferguson N.M., Gao H., Hill V., Imai N., Johansson M.A., Kada S., Morgan O., Pastore Y Piontti A., Polonsky J.A., Prasad P.V., Quandelacy T.M., Rambaut A., Tappero J.W., Vandemaele K.A., Vespignani A., Warmbrod K.L., Wong J.Y., WHO COVID-19 Modelling Parameters Group Early insights from statistical and mathematical modeling of key epidemiologic parameters of COVID-19. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26(11):e1–e14. doi: 10.3201/eid2611.201074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonelli F., Sarasini A., Zierold C., Calleri M., Bonetti A., Vismara C., Blocki F.A., Pallavicini L., Chinali A., Campisi D., Percivalle E., DiNapoli A.P., Perno C.F., Baldanti F. Clinical and analytical performance of an automated serological test that identifies S1/S2-neutralizing IgG in COVID-19 patients semiquantitatively. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020;58(9) doi: 10.1128/JCM.01224-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buitrago-Garcia D., Egli-Gany D., Counotte M.J., Hossmann S., Imeri H., Ipekci A.M., Salanti G., Low N. Occurrence and transmission potential of asymptomatic and presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020;17(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byambasuren O., Cardona M., Bell K., Clark J., McLaws M.L., Glasziou P. Estimating the extent of asymptomatic COVID-19 and its potential for community transmission: systematic review and meta-analysis. Off. J. Assoc. Med. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. Canada. 2020;5(4):223–234. doi: 10.3138/jammi-2020-0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cereda D., Manica M., Tirani M., Rovida F., Demicheli V., Ajelli M., Poletti P., Trentini F., Guzzetta G., Marziano V., Piccarreta R., Barone A., Magoni M., Deandrea S., Diurno G., Lombardo M., Faccini M., Pan A., Bruno R., Pariani E., Grasselli G., Piatti A., Gramegna M., Baldanti F., Melegaro A., Merler S. The early phase of the COVID-19 epidemic in Lombardy, Italy. Epidemics. 2021;37 doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2021.100528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinazzi M., Davis J.T., Ajelli M., Gioannini C., Litvinova M., Merler S., Pastore Y Piontti A., Mu K., Rossi L., Sun K., Viboud C., Xiong X., Yu H., Halloran M.E., Longini IM Jr, Vespignani A. The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. Science. 2020;368(6489):395–400. doi: 10.1126/science.aba9757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, AN, Kessel, B., 2020 False positives in reverse transcription PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2. medRxiv [Preprint]. Available from: 〈https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.26.20080911v1.full〉.

- Corman V.M., Landt O., Kaiser M., Molenkamp R., Meijer A., Chu D.K., Bleicker T., Brünink S., Schneider J., Schmidt M.L., Mulders D.G., Haagmans B.L., van der Veer B., van den Brink S., Wijsman L., Goderski G., Romette J.L., Ellis J., Zambon M., Peiris M., Goossens H., Reusken C., Koopmans M.P., Drosten C. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(3) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies N.G., Klepac P., Liu Y., Prem K., Jit M., CMMID COVID-19 Working Group, Eggo R.M. Age-dependent effects in the transmission and control of COVID-19 epidemics. Nat. Med. 2020;26(8):1205–1211. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0962-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies N.G., Jarvis C.I., CMMID COVID-19 Working Group, Edmunds W.J., Jewell N.P., Diaz-Ordaz K., Keogh R.H. Increased mortality in community-tested cases of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7. Nature. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03426-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery Jon C, Russell Timothy, Liu Yang, Hellewell Joel, Pearson Carl, CMMID COVID-19 Working Group, Knight Gwenan M, Eggo Rosalind M, Kucharski Adam J, Funk Sebastian, Flasche Stefan, Houben Rein MGJ. The contribution of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections to transmission on the Diamond Princess cruise ship. Elife. 2020 doi: 10.7554/eLife.58699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faes C., Abrams S., Van Beckhoven D., Meyfroidt G., Vlieghe E., Hens N., Belgian Collaborative Group on COVID-19 Hospital Surveillance Time between symptom onset, hospitalisation and recovery or death: statistical analysis of Belgian COVID-19 patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17(20):7560. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, N., Laydon, D., Nedjati Gilani, G., Imai, N., Ainslie, K., Baguelin, M., et al., 2020 Report 9: Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand. Available from: 〈https://www.imperial.ac.uk/mrc-global-infectious-disease-analysis/covid-19/report-9-impact-of-npis-on-covid-19〉.

- Fu L., Wang B., Yuan T., Chen X., Ao Y., Fitzpatrick T., Li P., Zhou Y., Lin Y.F., Duan Q., Luo G., Fan S., Lu Y., Feng A., Zhan Y., Liang B., Cai W., Zhang L., Du X., Li L., Shu Y., Zou H. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2020;80(6):656–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasselli G., Zangrillo A., Zanella A., Antonelli M., Cabrini L., Castelli A., Cereda D., Coluccello A., Foti G., Fumagalli R., Iotti G., Latronico N., Lorini L., Merler S., Natalini G., Piatti A., Ranieri M.V., Scandroglio A.M., Storti E., Cecconi M., Pesenti A., COVID-19 Lombardy ICU Network Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected With SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1574–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X., Liu L., Shan H., Lei C.L., Hui D., Du B., Li L.J., Zeng G., Yuen K.Y., Chen R.C., Tang C.L., Wang T., Chen P.Y., Xiang J., Li S.Y., Wang J.L., Liang Z.J., Peng Y.X., Wei L., Liu Y., Hu Y.H., Peng P., Wang J.M., Liu J.Y., Chen Z., Li G., Zheng Z.J., Qiu S.Q., Luo J., Ye C.J., Zhu S.Y., Zhong N.S., China Medical Treatment Expert Group for COVID-19 Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. New Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzetta G., Riccardo F., Marziano V., Poletti P., Trentini F., Bella A., Andrianou X., Del Manso M., Fabiani M., Bellino S., Boros S., Urdiales A.M., Vescio M.F., Piccioli A., COVID-19 Working Group, Brusaferro S., Rezza G., Pezzotti P., Ajelli M., Merler S. Impact of a nationwide lockdown on SARS-CoV-2 transmissibility, Italy. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021;27(1):267–270. doi: 10.3201/eid2701.202114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Lau E., Wu P., Deng X., Wang J., Hao X., Lau Y.C., Wong J.Y., Guan Y., Tan X., Mo X., Chen Y., Liao B., Chen W., Hu F., Zhang Q., Zhong M., Wu Y., Zhao L., Zhang F., Cowling B.J., Li F., Leung G.M. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020;26(5):672–675. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellewell J., Abbott S., Gimma A., Bosse N.I., Jarvis C.I., Russell T.W., Munday J.D., Kucharski A.J., Edmunds W.J., Centre for the Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases COVID-19 Working Group, Funk S., Eggo R.M. Feasibility of controlling COVID-19 outbreaks by isolation of cases and contacts. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;8(4):e488–e496. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30074-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton J., Keeling M.J. Estimation of country-level basic reproductive ratios for novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19) using synthetic contact matrices. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020;16(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità, 2021 Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Available from: 〈https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/open-data/covid_19-iss.xlsx〉 Accessed April 29, 2021.

- Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), 2020 Primi risultati dell’indagine di sieroprevalenza sul SARS-CoV-2. 2020 Aug, 3. Available from: 〈https://www.istat.it/it/files//2020/08/ReportPrimiRisultatiIndagineSiero.pdf〉 Accessed May 05, 2021.

- Italian National Institute of Statistics, 2021. Demographic indicators. Available from: 〈http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=DCIS_INDDEMOG1&Lang=en〉 Accessed March 22, 2021.

- Kiem C., Massonnaud C., Levy-Bruhl D., Poletto C., Colizza V., Bosetti P., et al., 2020 Evaluation des stratégies vaccinales COVID-19 avec un modèle mathématique populationnel (Doctoral dissertation, Haute Autorité de Santé; Institut Pasteur Paris; Santé publique France). Available from: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/pasteur-03087143.

- Kucharski A.J., Russell T.W., Diamond C., Liu Y., Edmunds J., Funk S., Eggo R.M., Centre for Mathematical Modelling of Infectious Diseases COVID-19 Working Group Early dynamics of transmission and control of COVID-19: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(5):553–558. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30144-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavezzo E., Franchin E., Ciavarella C., Cuomo-Dannenburg G., Barzon L., Del Vecchio C., Rossi L., Manganelli R., Loregian A., Navarin N., Abate D., Sciro M., Merigliano S., De Canale E., Vanuzzo M.C., Besutti V., Saluzzo F., Onelia F., Pacenti M., Parisi S.G., Carretta G., Donato D., Flor L., Cocchio S., Masi G., Sperduti A., Cattarino L., Salvador R., Nicoletti M., Caldart F., Castelli G., Nieddu E., Labella B., Fava L., Drigo M., Gaythorpe K., Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team, Brazzale A.R., Toppo S., Trevisan M., Baldo V., Donnelly C.A., Ferguson N.M., Dorigatti I., Crisanti A., Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team Suppression of a SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in the Italian municipality of Vo’. Nature. 2020;584(7821):425–429. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2488-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.Q., Huang T., Wang Y.Q., Wang Z.P., Liang Y., Huang T.B., Zhang H.Y., Sun W., Wang Y. COVID-19 patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate, and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(6):577–583. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S., Zhang J., Zeng M., Yun Q., Guo W., Zheng Y., Zhao S., Wang M.H., Yang Z. Epidemiological parameters of COVID-19: case series study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(10) doi: 10.2196/19994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marziano V., Guzzetta G., Rondinone B.M., Boccuni F., Riccardo F., Bella A., Poletti P., Trentini F., Pezzotti P., Brusaferro S., Rezza G., Iavicoli S., Ajelli M., Merler S. Retrospective analysis of the Italian exit strategy from COVID-19 lockdown. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2021;118(4) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2019617118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCombs A., Kadelka C. A model-based evaluation of the efficacy of COVID-19 social distancing, testing and hospital triage policies. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020;16(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolai L.A., Meyer C.G., Kremsner P.G., Velavan T.P. Asymptomatic SARS Coronavirus 2 infection: invisible yet invincible. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;100:112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.08.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Driscoll M., Ribeiro Dos Santos G., Wang L., Cummings D., Azman A.S., Paireau J., Fontanet A., Cauchemez S., Salje H. Age-specific mortality and immunity patterns of SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2021;590(7844):140–145. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2918-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onder G., Rezza G., Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1775–1776. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oran D.P., Topol E.J. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection: a narrative review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020;173(5):362–367. doi: 10.7326/M20-3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M., Cook A.R., Lim J.T., Sun Y., Dickens B.L. A systematic review of COVID-19 epidemiology based on current evidence. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9(4):967. doi: 10.3390/jcm9040967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiris J.S., Chu C.M., Cheng V.C., Chan K.S., Hung I.F., Poon L.L., Law K.I., Tang B.S., Hon T.Y., Chan C.S., Chan K.H., Ng J.S., Zheng B.J., Ng W.L., Lai R.W., Guan Y., Yuen K.Y., HKU/UCH SARS Study Group Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet. 2003;361(9371):1767–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13412-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Saez J., Lauer S.A., Kaiser L., Regard S., Delaporte E., Guessous I., Stringhini S., Azman A.S., Serocov-POP Study Group Serology-informed estimates of SARS-CoV-2 infection fatality risk in Geneva, Switzerland. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;21(4):E69–E70. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30584-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poletti P., Tirani M., Cereda D., Trentini F., Guzzetta G., Marziano V., Buoro S., Riboli S., Crottogini L., Piccarreta R., Piatti A., Grasselli G., Melegaro A., Gramegna M., Ajelli M., Merler S. Age-specific SARS-CoV-2 infection fatality ratio and associated risk factors, Italy, February to April 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(31) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.31.2001383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poletti P., Tirani M., Cereda D., Trentini F., Guzzetta G., Sabatino G., Marziano V., Castrofino A., Grosso F., Del Castillo G., Piccarreta R., Andreassi A., Melegaro A., Gramegna M., Ajelli M., Merler S., ATS Lombardy COVID-19 Task Force Association of age with likelihood of developing symptoms and critical disease among close contacts exposed to patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in Italy. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccardo F., Ajelli M., Andrianou X.D., Bella A., Del Manso M., Fabiani M., Bellino S., Boros S., Urdiales A.M., Marziano V., Rota M.C., Filia A., D’Ancona F., Siddu A., Punzo O., Trentini F., Guzzetta G., Poletti P., Stefanelli P., Castrucci M.R., Ciervo A., Di Benedetto C., Tallon M., Piccioli A., Brusaferro S., Rezza G., Merler S., Pezzotti P., COVID-19 Working Group Epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19 cases and estimates of the reproductive numbers 1 month into the epidemic, Italy, 28 January to 31 March 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(49) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.49.2000790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salje H., Tran Kiem C., Lefrancq N., Courtejoie N., Bosetti P., Paireau J., Andronico A., Hozé N., Richet J., Dubost C.L., Le Strat Y., Lessler J., Levy-Bruhl D., Fontanet A., Opatowski L., Boelle P.Y., Cauchemez S. Estimating the burden of SARS-CoV-2 in France. Science. 2020;369(6500):208–211. doi: 10.1126/science.abc3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanelli P., Bella A., Fedele G., Pancheri S., Leone P., Vacca P., Neri A., Carannante A., Fazio C., Benedetti E., Fiore S., Fabiani C., Simmaco M., Santino I., Zuccali M.G., Bizzarri G., Magnoni R., Benetollo P.P., Merler S., Brusaferro S., Rezza G., Ferro A. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in an area of northeastern Italy with a high incidence of COVID-19 cases: a population-based study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021;27(4):633.e1–633.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentini F., Guzzetta G., Galli M., Zardini A., Manenti F., Putoto G., Marziano V., Gamshie W.N., Tsegaye A., Greblo A., Melegaro A., Ajelli M., Merler S., Poletti P. Modeling the interplay between demography, social contact patterns, and SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the South West Shewa Zone of Oromia Region, Ethiopia. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s12916-021-01967-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentini F., Marziano V., Guzzetta G., Tirani M., Cereda D., Poletti P., Piccarreta R., Barone A., Preziosi G., Arduini F., Della Valle P.G., Zanella A., Grosso F., Castillo G., Castrofino A., Grasselli G., Melegaro A., Piatti A., Andreassi A., Gramegna M., Ajelli M., Merler S. The pressure on healthcare system and intensive care utilization during the COVID-19 outbreak in the Lombardy region: a retrospective observational study on 43,538 hospitalized patients. Am J Epidemiol. 2021 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwab252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verity R., Okell L.C., Dorigatti I., Winskill P., Whittaker C., Imai N., Cuomo-Dannenburg G., Thompson H., Walker P., Fu H., Dighe A., Griffin J.T., Baguelin M., Bhatia S., Boonyasiri A., Cori A., Cucunubá Z., FitzJohn R., Gaythorpe K., Green W., Hamlet A., Hinsley W., Laydon D., Nedjati-Gilani G., Riley S., van Elsland S., Volz E., Wang H., Wang Y., Xi X., Donnelly C.A., Ghani A.C., Ferguson N.M. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(6):669–677. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30243-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vespignani A., Tian H., Dye C., Lloyd-Smith J.O., Eggo R.M., Shrestha M., Scarpino S.V., Gutierrez B., Kraemer M., Wu J., Leung K., Leung G.M. Modelling covid-19. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2020;2(6):279–281. doi: 10.1038/s42254-020-0178-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz E., Mishra S., Chand M., Barrett J.C., Johnson R., Geidelberg L., Hinsley W.R., Laydon D.J., Dabrera G., O’Toole Á., Amato R., Ragonnet-Cronin M., Harrison I., Jackson B., Ariani C.V., Boyd O., Loman N.J., McCrone J.T., Gonçalves S., Jorgensen D., Myers R., Hill V., Jackson D.K., Gaythorpe K., Groves N., Sillitoe J., Kwiatkowski D.P., COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) Consortium, Flaxman S., Ratmann O., Bhatt S., Hopkins S., Gandy A., Rambaut A., Ferguson N.M. Assessing transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Nature. 2021;593:266–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03470-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood S.N., Wit E.C., Fasiolo M., Green P.J. COVID-19 and the difficulty of inferring epidemiological parameters from clinical data. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021;21(1):27–28. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30437-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2020. Contact tracing in the context of COVID-19: interim guidance, 10 May 2020. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332049.

- Wu J.T., Leung K., Leung G.M. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):689–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.T., Leung K., Bushman M., Kishore N., Niehus R., de Salazar P.M., Cowling B.J., Lipsitch M., Leung G.M. Estimating clinical severity of COVID-19 from the transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China. Nat. Med. 2020;26(4):506–510. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0822-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Chen X., Deng X., Chen Z., Gong H., Yan H., Wu Q., Shi H., Lai S., Ajelli M., Viboud C., Yu P.H. Disease burden and clinical severity of the first pandemic wave of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Nat. Commun. 2020;11(1):5411. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19238-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Litvinova M., Liang Y., Wang Y., Wang W., Zhao S., Wu Q., Merler S., Viboud C., Vespignani A., Ajelli M., Yu H. Changes in contact patterns shape the dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Science. 2020;368(6498):1481–1486. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., Xiang J., Wang Y., Song B., Gu X., Guan L., Wei Y., Li H., Wu X., Xu J., Tu S., Zhang Y., Chen H., Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material.