Abstract

The public's risk perception of public health emergencies will determine their behavior choices to a certain extent. Research on public risk perception of emergencies is an integral part of crisis management. From the perspective of the whole life cycle, this article takes the COVID-19 epidemic as an example. It conducts empirical analysis to study the influencing factors of public risk perception of public health emergencies. The results show that: (1) the public's risk perception is affected by individual factors, event characteristics, social influencing factors, and individual relationship factors. (2) The more the public is familiar with the epidemic, the lower the risk of the epidemic. The more the public can control the loss of the epidemic risk, the perceived epidemic risk will be reduced. The more the public trusts the supreme power of the government, the lower the risk of the epidemic in their hearts is. The higher the closeness of the risk and impact of the epidemic to individuals, the higher the level of risk perception is. (3)The public's risk perception will evolve with the development of the situation, and there are differences in recognition of government departments' control measures at different stages of public health emergencies. The relevant departments should effectively guide the public's risk response behavior in combination with the life cycle of public health emergencies. The research conclusions of this article clarify the dynamic evolution of risk perception and provide a specific reference for the emergency management of public health emergencies.

Keywords: Public health emergencies, Whole life cycle, Risk perception, Public behavior, COVID-19

1. Introduction

The impacts of major public health emergencies are continuously broadening with an increased severity, leading to a series of systemic risks with a high degree of complexity, uncertainty, and ambiguity. The negative impacts of the novel coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19) on the social system are gradually appearing. According to the forecast of the IMF's 2021 World Economic Outlook Report, the global economic contraction in 2020 is about 4.4% [1]. The World Tourism Cities Federation issued the “World Tourism Cities Development Report 2020″ and pointed out that in 2020, the global international tourist tourists dropped by 73% compared with 2019 [2]. The annual report of the World Trade Statistical Review released by the WTO shows that global trade fell by 5.3% in 2020 [3]. The actions were undertaken by the government play a critical role in coping with the adverse effects of COVID-19. The government should have an in-depth knowledge of how the public understands the pandemic and react accordingly. Furthermore, individual cognition also influences pandemic prevention and social behavior [4].

Risk perception plays a critical role in the public's behavioral response in emergencies. Excessive risk perception will not only make residents feel anxious, uneasy, and other negative emotions [5]. Shanghai Spirit According to a survey conducted by the Health Center at the beginning of March 2020, approximately 35% of the respondents were psychologically distressed and had noticeable emotional stress reactions under the influence of the epidemic [6]. In addition, irrational group behaviors may even occur, such as panic buying masks and toilet paper in various parts of the world during the epidemic. These incidents not only hindered the anti-epidemic work in the event of a public health crisis but also increased the difficulty of the overall anti-epidemic work in society. Therefore, to effectively adjust the people's risk perception level, it is necessary to monitor people's risk perceptions and explore the factors during the whole life cycle of emergencies, which is part of emergency management in public health emergencies.

Risk perception is a concept that describes the public's subjective and intuitive judgments and personal attitudes towards risk. At present, there have been many types of research on public risk perception in emergencies, mainly focusing on theoretical research on risk perception. The basic concepts of public risk perception under troubles can be principally divided into considerations from the level of internal influence and external influence. Mostly took “influencing factors-risk perception level” as the path to explore the influence of risk information, media, group attitudes, emotions, and other factors on risk perception [[7], [8], [9], [10]]. Existing studies point out that the public's risk perception manifests an individual's psychological state of objective evaluation of target risks [[11], [12], [13]]. At the level of external influence, the public's perception of risk belongs to the process of responding to risk information [14,15]. That risk transformation follows the evolutionary chain of “objective risk-subjective perception-behavioral choice” [16]. The research on the influencing factors of public risk perception under emergencies included two aspects which are the individual's own influencing factors and the external influencing factors.

In terms of individual characteristics, it is found that demographic factors including gender, age, work, and residence during the pandemic have a significant effect on risk perception. The risk perception scores of people aged 18–28 are lower than those of older respondents who have a job and have a higher level of education have significantly higher risk perception scores than other respondents [[17], [18], [19]]. Demographic factors are the main determinants of COVID-19 risk perception. People at high risk of illness are more likely to perceive the risk and take specific actions [20]. There are also differences in the risk perception factors of different occupations. For example, taxi drivers rely more on traditional media to obtain information on the epidemic, while pharmacists believe that social media play a critical role [21,22]. It is mainly due to differences in risk perception caused by different levels of knowledge. The research found that there is a positive correlation between knowledge and risk perception [23].

As far as external influence factors are concerned, the probability of occurrence, the degree of harm, and the uncertainty of the consequences of risks also affect risk perception. Internet public opinion essentially constructs the public's risk perception and becomes an essential reference for taking response actions [24]. Mass media always has great importance in shaping public risk perception. The study found that obtaining COVID-19 information through the media will affect the public's risk perception. Some information has increased the public's risk perception level, while others have reduced the level [25]. For example, the surge in cases will increase the public's perception of risk to a certain extent [26]. During the pandemic, the media's key role in spreading disease awareness and educating the public on preventive behavior has been generally recognized [27]. The attention and trust of government media are essential determinants. More people are willing to obtain information about the epidemic through official channels. Higher protection behavior is related to perceived severity [28,29]. Politics and the media may play an essential role in determining the formation of risk perceptions. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the higher the proportion of Trump voters in a county, the lower the risk perception [30,31]. The position of political parties and institutional trust will have a decisive effect on the prevention and control of the public. Cultural factors are also the reasons for the differences in public risk perception. Research has found that the spread of COVID-19, cultural background, and current political situations are the reasons for international differences in risk perception [32]. In addition, social community safety support improves residents' risk perception, damage identification, and criticality identification, but harms novelty identification. Community safety support can enable the public to understand the risk information of the COVID-19 pandemic [33].

During public health emergencies, the public's risk perception often presents different levels due to changes in their perceptions of the evolution of crises. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences conducts continuous investigations on social mentality during the epidemic. The survey shows that as the epidemic situation worsens and control escalate, the public's attention to COVID-19 has increased significantly which from 67.6% to 89.1%. The degree of panic has dropped from 4.2 to 2.8, and other negative emotions have also been eased [34]. Studies have shown that the risk perception factors are diverse. Individuals ' risk perception level will be affected by many factors such as psychology, society, culture, system, and oneself, which play an essential role in the dissemination of risk information. However, risk perception will dynamically evolve as emergencies evolve. Therefore, there are specific differences in risk perception at different stages of the whole life cycle of emergencies. The current empirical research on risk perception in emergencies mainly collects data through static questionnaire surveys after the incident, lacking a dynamic perspective to explore the influencing factors of risk perception. There has been very little research on the differences in risk perception at different stages of the whole life cycle of emergencies.

Thus, this article aims at investigating the influencing factors of public risk perception of the whole life cycle of COVID-19. From the perspective of the whole life cycle, the influence of individual factors, event characteristic factors, social influencing factors, and individual relationship factors on public risk perception are explored. Through a dynamic study, the evolution of public risk perception of the whole life cycle is measured to analyze the evolution law of public risk perception in emergencies more comprehensively and scientifically.

2. Research hypothesis and conceptual framework

Based on the previous studies, the influencing factors of risk perception include two aspects of the individual's own influencing factors and external influence factors. In terms of individual characteristics, the study found that gender, age, occupation, disaster experience, and personal risk knowledge level will significantly affect the risk perception [35]. Existing research has proved the path relationship between public risk perception and willingness to respond to emergencies. However, the public's risk perception will change with the reality. The situation, gender, media channels have an impact on the public's risk perception. In addition, some scholars have found that at different stages of the epidemic, residents' different perceptions of the epidemic will lead to changes in risk perception, which will affect residents' epidemic prevention and control behaviors [36].

Due to a large number of occupations, the inclusion of several options will have a single deviation. The occupational factors and health conditions will directly impact residents' awareness of the epidemic [37,38]. Therefore, this article mainly considers the impact of residents’ understanding of the epidemic on risk perception and will conduct further detailed research on social attributes such as occupational characteristics in the follow-up. Based on the above analysis, the specific hypotheses are proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 1

The influence of an individual's own factors on risk perception

H1a

People of different genders have significant differences in the risk perception of the epidemic

H1b

People of different ages have significant differences in the risk perception of the epidemic

H1c

Different levels of education have significant differences in the risk perception of the epidemic

H1d

Different understanding of the COVID-19 epidemic affects the risk perception of the epidemic

The external influence factors are mainly event risk, media orientation, expert opinion, group perception, information source, and credibility. “Risk determinism” locates the research object at the source of risk perception and believes that risk is the decisive factor affecting public risk perception [39]. Studies have shown that the intensity and type of risk perception brought by different facilities are different. The risk perception of risks with high uncertainty and long-term consequences is more minor, while the probability of occurrence, the degree of harm, and the effects of the risk are smaller. Characteristics such as uncertainty also affect risk perception [40]. Based on this, we propose the following specific hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2

The impact of event characteristic factors on risk perception

H2a

The more understanding the cause of the epidemic, the more accurate risk perception ability will be.

H2b

The more information about the type, level, and scope of an epidemic event, the more accurate risk perception ability will be.

In addition, social media exposure is positively correlated with the formation of risk perception [41]. Internet public opinion primarily constructs the public's risk perception and becomes an essential reference for responding actions [42]. It is found that social media exposure is positively correlated with risk perception [43]. During COVID-19, social media has more significant influence than traditional media and had a massive impact on the formation of residents' opinions and risk perception [44]. People with high overall trust perceive fewer COVID-19-related risks than people with low general confidence, and people with high social confidence perceive more risks than people with low social confidence [43]. During the epidemic, social media provided experts and the public with an opportunity to quickly disseminate information to many individuals, which in turn affected individuals' perceptions of risks and mitigation measures [44]. Based on this, we propose the following specific hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3

The influence of social influencing factors on risk perception

H3a

Different levels of trust governments have significant differences in the risk perception of the epidemic

H3b

The dissemination of false information about the epidemic will affect the public's risk perception and judgment

H3c

Positive media reports will affect the public's risk perception judgment

H3d

Expert opinions will affect the public's risk perception judgment

H3e

The herd effect will affect the public's risk perception judgment

Moreover, emotions and individual relationship factors will also affect risk perception to a certain extent. Risk perception and negative emotional state are positively correlated, and people's uncontrollable feelings of disasters will cause their risk perception [10,45]. During the epidemic, community information platforms and community workers will generate a large amount of media information, leading an increase in public risk perception [46]. Based on this, we propose the following specific hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4

The influence of individual relationship factors on risk perception

H4a

The lower the public's sense of control, the higher the risk perception

H4b

The greater the cost faced by the public, the higher the risk perception

H4c

A large amount of epidemic prevention and rescue information reduces public risk perception

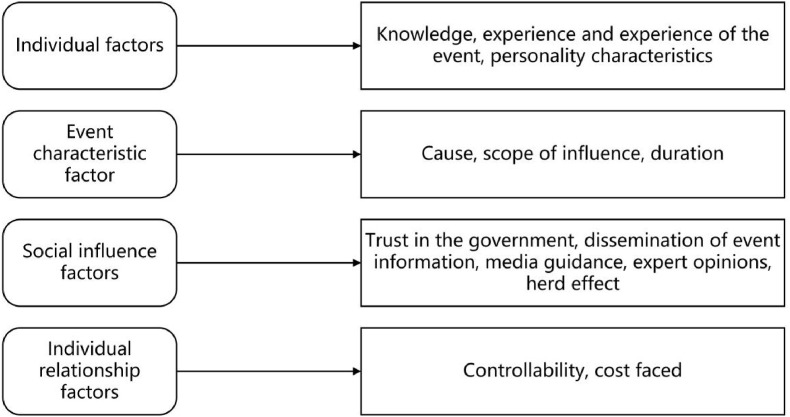

Fig. 1 shows the establishment of a logical conceptual model of individual risk perception based on the relationship between these four influencing factors. The factors of the event influence the objective risk perception. The four factors constitute subjective risk perception which will lead to different perceptions of the public's risk: some overestimate the risk and react fiercely, or some underestimate the risk and neglect to prevent it.

Fig. 1.

Logical conceptual model of individual risk perception.

The following is based on this logical conceptual framework to classify and analyze the main factors affecting individual risk perception of public health emergencies.

By selecting 13 influencing factors, the influencing factors of individuals' perception of the risk of public health emergencies are preliminarily obtained, as shown in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Influencing factors of individual risk perception in COVID-19.

At this time, risk communication included exchanging information and opinions among individuals, groups, and institutions can reduce the negative impact of information proliferation. In any risk communication, information is filtered through the receiver's selective lens, and risk perception is dominant [47]. On the one hand, appropriate, timely, and data-based health information is significant to increases the public's willingness to comply. On the other hand, authoritative institutions also play a crucial role in risk communication [48]. When a crisis occurs, the social acceptance of the risk response organization means that the authority has accumulated enough reputation to improve the effectiveness of risk communication when faced with information asymmetry and information mixing.

3. Methods

3.1. Questionnaire design

A total of three sets of questionnaires were issued in this survey to investigate and analyze the influencing factors of public risk perception, the public's individual risk perception, and the public risk perception from the perspective of the whole life cycle. For the investigation of public risk perception influencing factors, the survey sample data was preprocessed. Because the risk perception process of the COVID-19 epidemic event is mainly controlled by the individual's risk perception influencing factors, the size of the risk perception is governed by the previous research in this article. 13 influencing factors were used as indicators of risk perception scores. Questionnaires were distributed on the WeChat platform using Questionnaire Star in a “snowball” way. Two hundred ninety-five questionnaires were returned. Among them, nine “I do not promise” were invalid questionnaires, and Two hundred eighty-six valid questionnaires, SPSS software performs statistical analysis. The main socio-demographic characteristics participating in the survey are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Main socio-demographic characteristics.

| Attributes | Proportion of people | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 33.64% |

| Female | 66.36% | |

| Age | ≤20 | 7.10% |

| 21~30 | 24.47% | |

| 31~40 | 30.25% | |

| 41~50 | 23.77% | |

| ≥50 | 11.42% | |

| Education level | Below high school | 23.08% |

| High school | 6.51% | |

| Technical secondary school or college | 20.71% | |

| Undergraduate | 19.53% | |

| Postgraduate | 30.18% | |

To ensure the internal consistency and reliability of the questionnaire, we conducted a reliability test on the questionnaire. The Cronbach's alpha is 0.873, and the Cronbach's alpha based on standardized items is 0.878, which shows this scale is ideal and has high reliability.

To analyze the public's risk perception, we designed a set of questionnaires and conducted a questionnaire survey of people who have experienced the pneumonia epidemic caused by COVID-19 in China. Questionnaires were distributed on the WeChat platform by Questionnaire Star in “snowball”, and 314 questionnaires were returned. Among them, two “I do not promise” were invalid questionnaires and 312 valid questionnaires. The SPSS software was used for statistical analysis. To ensure the internal consistency and reliability of the questionnaire, we conducted a reliability test on the questionnaire. The result's Cronbach's alpha is 0.799, and the Cronbach's alpha based on standardized items is 0.877, which shows this scale is ideal and has high reliability.

Regarding the influencing factors of public risk perception from the perspective of the whole life cycle, we combined with the results of the analysis of the impact of individual risk perception under public health emergencies and designed a set of questionnaires to conduct a questionnaire on people who have experienced the novel coronavirus infection in China survey. Questionnaires were distributed on the WeChat platform by Questionnaire Star in “snowballing”, and Three hundred thirty-eight questionnaires were returned, of which 338 were valid questionnaires, and 0 were invalid questionnaires. The SPSS software was used for statistical analysis. To understand the investigation and analysis of the dynamic evolution of public risk perception influencing factors, five options were designed for all the above indicators, namely: disagree entirely, disagree, neutral, relatively agree, and agree entirely. To ensure the internal consistency and reliability of the questionnaire, we conducted a reliability test on the questionnaire that the result's Cronbach's alpha is 0.932, and the Cronbach's alpha based on the standardized item is 0.932, so this scale is ideal has high reliability.

3.2. Setting of variables

The three sets of questionnaires issued in this survey selected different variables to investigate and analyze the influencing factors of public risk perception, the individual's risk perception, and the public risk perception from the perspective of the whole life cycle. Latent variables cannot be measured directly and can only be calculated indirectly using observed variables. This paper selects four factors that affect public risk perception as exogenous latent variables; public risk perception as endogenous latent variables and subjective indicators for evaluation. Considering the difficulty and limitations of data acquisition, this study conducted operational processing of each group of independent variables through questionnaire surveys based on the existing literature. Table 2 -Table 4 shows the specific methods and measurement methods of the active processing of each variable of the three groups of questionnaires.

Table 2.

Variables of public risk perception influencing factors.

| Variable |

Measuring |

Variable assignment |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Risk perception | The public's risk perception level in COVID-19 | ||

| Independent variable | Individual factors | Gender | The gender of the public participating in the survey | Male = 1; female = 0 |

| Age | The age of the public participating in the survey | ≤20 = 1; 21~30 = 2; 31~40 = 3; 41~50 = 4; ≥50 = 5 | ||

| Education level | Educational qualifications of the public participating in the survey | Bachelor degree and above = 1; high school = 2; junior high school and below = 3 | ||

| Awareness of the COVID-19 | The public's understanding of the symptoms of new coronavirus infection | 0~9 continuous variable | ||

| Event characteristic factor | Cause of the COVID-19 | The public's understanding of the cause of the epidemic | 0~9 continuous variable | |

| The level of understanding of the COVID-19 incident information | The public's understanding of epidemic treatment methods | 0~9 continuous variable | ||

| The public's understanding of the spreading method and mechanism of the COVID-19 | 0~9 continuous variable | |||

| Social influence factors | Trust in the government | The public's trust in the information released by the government | 0~9 continuous variable | |

| Rumors spread | The influence of dissemination of false information | 0~9 continuous variable | ||

| Media reports | The impact of news media's announcement of epidemic information | 0~9 continuous variable | ||

| The impact of positive news reports on public risk perception | 0~9 continuous variable | |||

| The impact of news media's announcement of epidemic information | 0~9 continuous variable | |||

| Expert advice | The impact of experts' release of epidemic information | 0~9 continuous variable | ||

| Herd effect | The impact of information posted on social media | 0~9 continuous variable | ||

| The impact of the government's mandatory measures for COVID-19 prevention and control on public risk perception | 0~9 continuous variable | |||

| Individual relationship factors | Controllable | Possibility of own infection | 0~9 continuous variable | |

| Possibility of cure after infection | 0~9 continuous variable | |||

| Possibility of infection among local people | 0~9 continuous variable | |||

| The price faced | The COVID-19 threatens the lives and health of the public | 0~9 continuous variable | ||

Note: 0 means completely do not understand, 9 means understand entirely.

Table 4.

Variables of public risk perception influencing factors of the whole life cycle.

| Variable |

Measuring |

Variable assignment |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Risk perception | The public's risk perception level from the perspective of the whole life cycle | |

| Independent variable | Influencing factors of public risk perception during the COVID-19 monitoring and early warning period | Disseminate relevant public health knowledge | 0~5 continuous variable |

| Need to establish a rapid response channel for COVID-19 | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

| Need to carry out information collection and analysis of epidemic early warning and plan | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

| Influencing factors of public risk perception during the COVID-19 identification and control period | Need to promptly guide and prevent the spread of rumors during the period of COVID-19 epidemic identification and control | 0~5 continuous variable | |

| Need to strengthen information transparency | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

| Need to improve risk information perception and capture capabilities | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

| Need to improve risk information identification and processing capabilities | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

| Influencing factors of public risk perception during emergency control period | Need to cultivate good social sentiment and improve effective information channels | 0~5 continuous variable | |

| Need to provide information needs for each stage of the COVID-19 | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

| Influencing factors of public risk perception in the aftermath management period | Need to improve their crisis management capabilities | 0~5 continuous variable | |

| Need to encourage public participation and improve the ability of collaborative governance of social risks | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

| Need to strengthen disease control knowledge management | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

Note: 0 means disagree entirely, 5 means agree entirely.

In the first set of questionnaires, as shown in Table 2, 13 observed variable indicators were set to measure the four aspects of risk perception (own individual factors, event characteristic factors, social influencing factors, and individual relationship factors). For all the above indicators, ten options are designed, namely: know very little, know very little, know less, know the general, know a lot, know more, know a lot, know a lot, know completely, and assign them accordingly. The value of the score is from 0 to 9. This article takes gender, age, education level, transmission route and mechanism, treatment methods, and causes of the epidemic as independent variables, and takes risk perception as the dependent variable, and conducts regression analysis on the two.

Risk perception is an interactive process involving individuals and organizations such as the government, media, and society. Regarding the influencing factors of the public's individual risk perception, this article considers the influencing factors of the public's individual risk perception from the national level, media level, local government, and social level, as shown in Table 3. For all the above indicators, five options are designed, namely: not at all, relatively not, generally, relatively, and complete.

Table 3.

Variables of the public's individual risk perception influencing factors.

| Variable |

Measuring |

Variable assignment |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Risk perception | The public's individual risk perception level under emergencies | |

| Independent variable | National level | Preventive management measures | 0~5 continuous variable |

| Control policy measures | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

| Own way of coping | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

| Follow the measures and contribute your own strength | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

| Policies are effective in safeguarding the interests of the country and the people | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

| Media level | Attitudes towards reporting of the COVID-19 | 0~5 continuous variable | |

| The most frequent way to receive information about COVID-19 | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

| Feelings about reports of COVID-19 | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

| Number of COVID-19 information that was proven to be misrepresented | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

| Which media reported on the COVID-19 is believed | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

| How to deal with doubts about the report | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

| Local government and social level | Attitudes of the central or local governments in issuing epidemic announcements | 0~5 continuous variable | |

| The local government releasing the epidemic information timely or not in time | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

| Local governments and social institutions actively cooperate with central policies | 0~5 continuous variable | ||

Note: 0 means disagree entirely, 5 means agree entirely.

Public risk perception is a process of collecting, selecting, understanding, and responding to crisis information. From the perspective of the whole life cycle, this article divides the emergency life cycle into the epidemic monitoring and early warning period, the epidemic identification and control period, the emergency control period, and the aftermath management period. From the different stages of the emergency, it studies the influencing factors of public risk perception. Table 4 shows the variable manipulation methods of the influencing factors of public risk perception from the perspective of the whole life cycle.

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of influencing factors of public risk perception

4.1.1. Hypothesis 1: the influence of individual's factors on risk perception

Table 5 shows that in terms of gender, the β-value corresponding to the dummy variable is −5.526, and the p-value is 0.018, which is statistically significant, assuming that H1a holds. Regarding age, the β -value corresponding to the dummy variable is −2.253, and the p-value is 0.035, which is statistically significant, so it is assumed that H1b holds. Regarding the education level, the β-value corresponding to the dummy variable is 0.646, and the p-value is 0.660, which is not statistically significant, so the hypothesis H1c does not hold. Regarding the degree of event awareness, the β-value corresponding to the dummy variable is 8.356, and the p-value is less than 0.001, which is of statistical significance. Hypothesis H1d holds.

Table 5.

Linear regression model of individual's factors on risk perception.

| Model | Unstandardized coefficients |

Standardized coefficients |

t | Sig. | Collinearity diagnostics |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| (Intercept) | 74.416 | 7.872 | 9.453 | 0 | |||

| Gender | −5.526 | 2.319 | −0.117 | −2.383 | 0.018 | 0.986 | 1.014 |

| Age | −2.253 | 1.064 | −0.106 | −2.117 | 0.035 | 0.943 | 1.061 |

| Education | 0.646 | 1.466 | 0.022 | 0.441 | 0.66 | 0.937 | 1.068 |

| Understanding | 8.356 | 0.732 | 0.558 | 11.412 | 0 | 0.991 | 1.009 |

The analysis results verify these three hypotheses (H1a, H1b, H1c) that the public's gender, age, and knowledge of the event will affect their risk perception. However, there is an exception in the specific assumption (H1c). In terms of education level, there is no breakdown of academic qualifications, and the hypothetical result of higher risk perception of people with high education is higher risk perception.

4.1.2. Hypothesis 2: the impact of event characteristic factors on risk perception

Table 6 shows that in terms of transmission routes and mechanisms, the β-value corresponding to the dummy variable is 4.767. The p-value is less than 0.001, which is of statistical significance, indicating that the dummy variable is positively correlated with risk perception. It shows that the more understanding the epidemic event, the more precise the risk perception ability is, the more accurate the hypothesis H2a is. In terms of treatment methods, the β-value corresponding to the dummy variable is 2.548, and the p-value is 0.001, which is of statistical significance. Regarding the cause of the epidemic, the β-value corresponding to the dummy variable is 1.619, and the p-value is 0.044, which is statistically significant, indicating that the more information about the type, level, and scope of the epidemic event, the more accurate risk perception ability will be, therefore, it is assumed that H2b holds.

Table 6.

Linear regression model of event characteristic factors on risk perception.

| Model | Unstandardized coefficients |

Standardized coefficients |

t | Sig. | Collinearity diagnostics |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| (Intercept) | 58.557 | 5.674 | 10.32 | 0 | |||

| Way for spreading | 4.767 | 0.92 | 0.311 | 5.183 | 0 | 0.622 | 1.608 |

| Treatment method | 2.548 | 0.727 | 0.246 | 3.506 | 0.001 | 0.453 | 2.206 |

| Cause of COVID-19 | 1.619 | 0.799 | 0.148 | 2.025 | 0.044 | 0.419 | 2.388 |

4.1.3. Hypothesis 3: the influence of social influencing factors on risk perception

Table 7 shows that in terms of the government's announcement of epidemic information, the β-value corresponding to the dummy variable is 2.300, and the p-value is less than 0.001, which is statistically significant. It is assumed that H3a is valid. Regarding the news media's announcement of the epidemic situation, the β-value corresponding to the dummy variable is 1.743, and the p-value is 0.007, which is of statistical significance. In disseminating false information, the β-value corresponding to the dummy variable is 2.357, and the p-value is less than 0.001, so it is assumed that H3b holds. Regarding positive news reports, the β-value corresponding to the dummy variable is 1.723, and the p-value is less than 0.001, so it is assumed that H3c holds. Regarding experts' publishing of epidemic information, the β-value corresponding to the dummy variable is 0.712, and the p-value is 0.199, which does not indicate that the experts' opinions will affect the public's risk perception judgment, so the hypothesis H3d is not valid. Regarding herd effect, the β-value corresponding to the dummy variable is 2.398, and the p-value is less than 0.001, so it is assumed that H3e holds (see Table 8).

Table 7.

Linear regression model of social influencing factors on risk perception.

| Model | Unstandardized coefficients |

Standardized coefficients |

t | Sig. | Collinearity diagnostics |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| (Intercept) | 17.436 | 4.24 | 4.112 | 0 | |||

| The government announces the COVID-19 epidemic information | 2.3 | 0.628 | 0.167 | 3.662 | 0 | 0.355 | 2.819 |

| News media announces epidemic information | 1.743 | 0.645 | 0.128 | 2.7 | 0.007 | 0.327 | 3.054 |

| Positive report | 1.723 | 0.327 | 0.188 | 5.273 | 0 | 0.576 | 1.735 |

| Dissemination of false information | 2.357 | 0.317 | 0.274 | 7.446 | 0 | 0.545 | 1.835 |

| Social media information | 1.312 | 0.361 | 0.117 | 3.634 | 0 | 0.711 | 1.406 |

| Experts release epidemic information | 0.712 | 0.554 | 0.051 | 1.286 | 0.199 | 0.472 | 2.119 |

| Herd effect | 2.398 | 0.365 | 0.24 | 6.564 | 0 | 0.551 | 1.817 |

| Mandatory measures for government epidemic prevention and control | 2.043 | 0.578 | 0.117 | 3.537 | 0 | 0.673 | 1.486 |

Table 8.

Linear Regression model of risk perception with individual relationship factors.

| Model | Unstandardized coefficients |

Standardized coefficients |

t | Sig. | Collinearity diagnostics |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Tolerance | VIF | |||

| (Intercept) | 47.295 | 3.573 | 13.237 | 0 | |||

| Possibility of own infection | 1.125 | 0.436 | 0.132 | 2.579 | 0.01 | 0.351 | 2.851 |

| Possibility of cure after infection | 2.714 | 0.38 | 0.22 | 7.15 | 0 | 0.97 | 1.031 |

| Local people may be infected | 1.264 | 0.444 | 0.145 | 2.849 | 0.005 | 0.353 | 2.833 |

| Threat to life and health | 1.641 | 0.361 | 0.188 | 4.549 | 0 | 0.536 | 1.866 |

| Negative impact on life and work | 1.376 | 0.44 | 0.153 | 3.129 | 0.002 | 0.384 | 2.607 |

| Threat to people in the area | 1.458 | 0.376 | 0.176 | 3.88 | 0 | 0.445 | 2.248 |

| A large amount of epidemic prevention and control and rescue information affects life and work | 3.157 | 0.333 | 0.329 | 9.469 | 0 | 0.759 | 1.318 |

4.1.4. Hypothesis 4: the influence of individual relationship factors on risk perception

In summary, the following conclusions can be drawn:

-

(1)

The more the public is familiar with the epidemic, the lower the risk of the epidemic. The more the public understands the cause of the epidemic, information about the epidemic, preventive measures, and rescue situations, the more they will experience the risks of the epidemic more intuitively.

-

(2)

The more the public can control the loss of the epidemic risk, the perceived epidemic risk will be significantly reduced. If government departments try to raise the controllable level of the epidemic to a high level, especially the accuracy of the forecast of the epidemic, it will help the public to have a more rational judgment on the risk perception of the epidemic.

-

(3)

The more the public trusts the leadership of the government, the lower the risk of the epidemic in their hearts. The government's accurate judgment of the epidemic and the resettlement of the quarantined people will profoundly influence the public's trust in the government.

-

(4)

The higher the closeness of the risk and impact of the epidemic to individuals, the higher the level of risk perception. Therefore, the fear of surrounding people will directly affect people's risk perception of the epidemic.

A summary of the conducted hypothesis tests is provided in Table 9 .

Table 9.

Summary of the hypothesis tests.

| Hypothesis | result |

|---|---|

| H1a: People of different genders have significant differences in the risk perception of the epidemic | √ |

| H1b: People of different ages have significant differences in the risk perception of the epidemic | √ |

| H1c: Different levels of education have significant differences in the risk perception of the epidemic | ╳ |

| H1d: Different understanding of the COVID-19 epidemic affects the risk perception of the epidemic | √ |

| H2a: The more you understand the cause of the epidemic, the more accurate your risk perception ability will be | √ |

| H2b: The more information you have about the type, level, and scope of an epidemic event, the more accurate your risk perception ability will be | √ |

| H3a: Different levels of trust governments have significant differences in the risk perception of the epidemic | √ |

| H3b: The dissemination of false information about the epidemic will affect the public's risk perception and judgment | √ |

| H3c: Positive media reports will affect the public's risk perception judgment | √ |

| H3d: Expert opinions will affect the public's risk perception judgment | ╳ |

| H3e: The herd effect will affect the public's risk perception judgment | √ |

| H4a: The lower the public's sense of control, the higher the risk perception | √ |

| H4b: The greater the cost faced by the public, the higher the risk perception | √ |

| H4c: A large amount of epidemic prevention and rescue information reduces public risk perception | √ |

4.2. Investigation and analysis of public individual risk perception

Table 10 shows the descriptive statistical results of the questionnaire survey results of the public's individual risk perception. Through the analysis of individual social questionnaires based on social risk assessment, the following conclusions can be drawn: Most of the public fully agree with the social management measures introduced by the government to prevent the COVID-19 epidemic. Concerning the various national policies and effects to control the COVID-19 epidemic, most of the public fully agrees. After the introduction of relevant guidelines for the COVID-19 epidemic prevention and control, most of the public have formed their ways of responding to the COVID-19 epidemic. Most of the people expressed their willingness to comply with the COVID-19 epidemic prevention and control measures and are willing to contribute their own strength. The majority of the people fully agree that the policies and standards for the prevention and control of the COVID-19 epidemic are highly effective in safeguarding the country's interests and the people. The majority of the public fully agree that local governments and social institutions (such as health, education, transportation, propaganda, etc.) actively cooperating with the implementation of relevant central policies. Most of the public is more concerned about and very concerned about the reports of the COVID-19 epidemic. Regarding the COVID-19 epidemic, the public's most common ways to receive information are automatic push by the media, browsing the media for information, and multi-channel comparison between private and official information. The public believes that most of the reports on the COVID-19 epidemic are relatively straightforward. Among all the COVID-19 epidemic news received by the majority of the public, the number of proved to be misrepresented or rumored is four or less for the “COVID-19 epidemic” reporting media, the public trusts the central media more (People's Daily, CCTV News, etc.) and government's briefings (such as government websites, official WeChat Weibo, press conferences, etc.). If most of the public is skeptical about the “COVID-19 epidemic” report, the handling method is to consult the central media and the government website. For the “COVID-19 epidemic” announcements issued by the central or local governments, most of the public believes more and fully believes. The public feels that the provincial release of the COVID-19 epidemic information is relatively timely and very timely. Most of the public feels that the provincial government's degree of openness and transparency of the COVID-19 epidemic information is fairly transparent and very transparent.

Table 10.

Results of public's individual survey.

| Range | Min | Max | Mean | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preventive management measures | 4 | 1 | 5 | 4.6 | 0.7 |

| Control policy measures | 3 | 2 | 5 | 4.71 | 0.54 |

| Own way of coping | 3 | 2 | 5 | 4.64 | 0.55 |

| Follow the measures and contribute your own strength | 4 | 1 | 5 | 4.72 | 0.55 |

| Policies are effective in safeguarding the interests of the country and the people | 4 | 1 | 5 | 4.82 | 0.46 |

| Local government social institutions actively cooperate with central policies | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4.73 | 0.49 |

| Attitudes towards reporting of the epidemic | 4 | 1 | 5 | 4.45 | 0.69 |

| Ways to receive the most epidemic information | 4 | 1 | 5 | 2.76 | 1.71 |

| Feelings about the COVID-19 report | 4 | 1 | 5 | 4.14 | 0.82 |

| Number of COVID-19 information that was proven to be misrepresented | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1.86 | 1.18 |

| Which media reported on the COVID-19 is believed | 4 | 1 | 5 | 3.97 | 1.07 |

| How to deal with doubts about the report | 4 | 1 | 5 | 4.08 | 1.27 |

| Attitudes of the central or local governments in issuing COVID-19 epidemic announcements | 4 | 1 | 5 | 4.55 | 0.61 |

| The local government releasing the COVID-19 epidemic information timely or not in time | 3 | 2 | 5 | 4.41 | 0.69 |

| Local governments and social institutions actively cooperate with central policies | 3 | 2 | 5 | 4.4 | 0.69 |

4.3. Analysis of influencing factors of public risk perception from the perspective of the whole life cycle

There are two reasons to explain why the information of public health emergencies disseminates widely. Firstly, to help internet users improve their ability to review information on emergencies, achieve the purpose of balancing and screening “virus” information. We need to develop tools or platforms that are easy to use, easy to learn, easy to obtain. We have practical operability so that the public can get information when they receive adequate information. Secondly, we need the help of others or third parties. We need to analyze the wrong reasons for the failure of information to help users or the public understand their characteristics and the reasons for being easily misled.

All indicators in this questionnaire are designed with five options, and the neutral value is 3. Therefore, the comparative average analysis is adopted, and the test value = 3 is selected. A single-sample T-test is carried out for the public's recognition of the risk perception control measures of relevant departments in different periods to explore how relevant departments are in the process of the dynamic evolution of public risk perception in emergencies. Effectively manage risks, and the inspection results are shown in Table 11 and Fig. 3 .

Table 11.

Results of Single-sample inspection.

| Life cycle | Measures | T-value = 3 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | Sig. | SEM | Difference 95% confidence interval |

|||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| Influencing factors of public risk perception during the COVID-19 monitoring and early warning period | Disseminate relevant public health knowledge | 86.426 | 0.000 | 4.07715 | 3.9844 | 4.1699 |

| Need to establish a rapid response channel for COVID-19 | 107.438 | 0.000 | 4.16320 | 4.0870 | 4.2394 | |

| Need to carry out information collection and analysis of epidemic early warning and plan | 89.317 | 0.000 | 3.45697 | 3.3808 | 3.5331 | |

| Influencing factors of public risk perception during the COVID-19 identification and control period | Need to promptly guide and prevent the spread of rumors during the period of COVID-19 epidemic identification and control | 75.886 | 0.000 | 4.24332 | 4.1333 | 4.3533 |

| Need to strengthen information transparency | 78.606 | 0.000 | 3.88427 | 3.7871 | 3.9815 | |

| Need to improve risk information perception and capture capabilities | 75.074 | 0.000 | 3.95549 | 3.8519 | 4.0591 | |

| Need to improve risk information identification and processing capabilities | 87.214 | 0.000 | 4.24332 | 4.1476 | 4.3390 | |

| Influencing factors of public risk perception during emergency control period | Need to cultivate good social sentiment and improve effective information channels | 95.102 | 0.000 | 4.23442 | 4.1468 | 4.3220 |

| Need to provide information needs for each stage of the COVID-19 | 94.637 | 0.000 | 4.23739 | 4.1493 | 4.3255 | |

| Influencing factors of public risk perception in the aftermath management period | Need to improve their crisis management capabilities | 104.581 | 0.000 | 4.41543 | 4.3324 | 4.4985 |

| Need to encourage public participation and improve the ability of collaborative governance of social risks | 125.985 | 0.000 | 4.35905 | 4.2910 | 4.4271 | |

| Need to strengthen disease control knowledge management | 108.602 | 0.000 | 4.47181 | 4.3908 | 4.5528 | |

Fig. 3.

Box-plot and mean value plot of risk perception factors.

According to the single-sample statistical results in Table 11 , it shows that during the epidemic monitoring and early warning period, the public needs to popularize relevant public health knowledge, establish rapid response channels for the epidemic, and carry out information collection and preparation of epidemic warnings and plans based on their risk perceptions for government departments. The average recognition of measures such as analysis is 4.07, 4.16, and 3.45 respectively. During the epidemic identification and control period, the public needs to promptly guide, prevent the spread of rumors, strengthen information transparency, and improve risk information perception and control. The average recognition of measures such as capturing capabilities and using expert knowledge to enhance information identification and processing capabilities is 4.24, 3.88, 3.95, and 4.24.

During the emergency control period, the average public recognition of government departments' need to cultivate good social sentiments and improve effective information channels during the emergency control period, and provide information needs for each epidemic stage, which are 4.23 and 4.23. In the aftermath management period, the average public recognition of government departments' need to improve their crisis management capabilities during the aftermath of the epidemic, the need to encourage public participation to enhance the ability to manage social risks, and the need to strengthen disease control knowledge management which are 4.41, 4.35, and 4.47. At the same time, according to Table 11, the single-sample test results show that when the selected test value is equal to 3, the P-value of all measures recognition is less than 0.05, indicating that the public is consistent with the different management and control actions to varying stages of the life cycle of public health emergencies. The neutral test value of 3 is additional. The average value of public acceptance of these measures is significantly higher than the test value of 3, indicating that the public's risk perception will evolve with the development of the situation. Different stages of health incidents differ in the degree of recognition of government departments' management and control measures. Government departments combine the public's risk perceptions to conduct risk management and control at different life cycle stages of emergencies, improving management effectiveness.

5. Limitations of the study

This article is innovative in exploring the influencing factors of public risk perception of public health emergencies from the perspective of the whole life cycle. It provides a new research path for scientifically guiding public risk response behaviors under public health emergencies. Because of the complexity of influencing factors, there are some shortcomings in the selection of questionnaire subjects. The overall age of the research subjects is relatively younger, and there is more miniature data collection for older groups. The factors that affect risk perception of the whole life cycle are not considered comprehensively. In the future, we should focus more on optimization of the relevant logic model to make the selection of samples more uniform and comprehensive consideration more careful. Furthermore, the research on the factors affecting public risk perception at different stages of the whole life cycle is not detailed enough. The protective measures taken by the public will also change from tentative to standard, irrational circumvention to rational defensive behavior. In the next step, the impact of the spread of epidemic information, individual organizations and group environmental factors, epidemic prevention and control measures, and epidemic changes on the evolution of public risk perception and the transformation of behavioral response patterns should be studied.

6. Conclusions

By establishing a logical conceptual model of individual risk perception, this paper proposes specific hypotheses based on the individual's factors, event characteristic factors, social influence factors, and individual relationship factors and takes the COVID-19 as an example. Through regression analysis to explore the affecting factors of public risk perception in public health emergencies. And then, the public's individual risk perception was investigated. The dynamic evolution of risk perception from the perspective of the whole life cycle was explored and further drew relevant conclusions through statistical analysis. The empirical research of this article organically combines the life cycle of public health emergencies, risk perception, and response behaviors to help analyze the psychological and behavioral changes of the public under public health emergencies. A phased study of public risk perception has yielded the following enlightenment:

During the monitoring and early warning period, relevant public health knowledge should be popularized, and social risk awareness should be enhanced. It is necessary to establish rapid response channels, improve timely risk early warning mechanisms, carry out information collection, analyze for early warning and contingency plans, and improve the foresight of emergency response.

During the identification control period, timely guidance should be taken to prevent the window-breaking effect of rumors and strengthen information transparency. Information ability plays a vital role in identifying false information. Relevant departments should establish an urban intelligent nervous system to improve risk information perception and capture capabilities and rely on expert knowledge to improve risk information identification and processing capabilities, show a rapid response mechanism for sensitive detection of abnormal information, strengthen information transparency and regulate public behavior.

During the emergency control period, an excellent social mood should be cultivated, and practical information channels should be improved. Relevant departments need to meet the public's level information needs, use high-quality information, avoid blindness of the public, and cultivate good social sentiments.

During the aftermath management period, it is necessary to improve its own crisis handling capabilities and improve the system. Encourage public participation to enhance the ability to coordinate social risk management; strengthen disease control knowledge management, and enhance knowledge storage and reuse capabilities.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Jing Wang reports financial support was provided by National Office for Philosophy and Social Sciences of China.

Acknowledgment

This paper is supported by the National Office for Philosophy and Social Sciences of the People's Republic of China(16CGL063).

References

- 1.International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook 2021. https://www.imf.org/zh/Publications/WEO/Issues/2021/03/23/world-economic-outlook-april-2021/

- 2.World Tourism Cities Federation . 2020. World Tourism Cities Development Report.http://cn.wtcf.org.cn/20210906/abde4b2a-d8ab-a73e-246b-60c3a528ac95.html/ 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Trade Organization . 2021. World Trade Statistical Review 2021.https://www.wto.org/search/search_e.aspx?search=basic&searchText=Global+trade+data+and+outlook&method=pagination&pag=0&roles=%2cpublic%2c/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuan J., Zou H., Xie K., Dulebenets M.A. An assessment of social distancing obedience behavior during the COVID-19 post-epidemic period in China: a cross-sectional survey. Sustainability. 2021;13:8091. doi: 10.3390/su13148091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo Fuzhou, Ju shaowei, Wang Layin. Emergency strategy analysis for chain disaster of MajorEpidemic-derived social panic--A SD experimentation based on“COVID19”Outbreak. Journal of Catastrophology. 2021 http://www.zaihaixue.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiu Jianyin, Shen Bin, Wang Zhen, Xie Bin, Xu Yifeng. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. https://gpsych.bmj.com/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rickard Laura N. Pragmatic and (or) constitutive? On the foundations of contemporary risk communication research. Risk Anal.: an official publication of the Society for Risk Analysis. 2021;41:466–479. doi: 10.1111/risa.13415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vosoughi Soroush, Roy Deb, Aral Sinan. The spread of true and false news online. Science. 2018;359:1146–1151. doi: 10.1126/science.aap9559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He Guizhen, Mol Arthur P.J., Zhang Lei, Lu Yonglong. Nuclear power in China after Fukushima: understanding public knowledge, attitudes, and trust. J. Risk Res. 2014;17:435–451. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2012.726251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong Yaping, Liu Weihua, Lee Tsorng Yeh, Zhao Huan, Ji Ji. Risk perception, knowledge, information sources and emotional states among COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China. Nurs. Outlook. 2021;69:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2020.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Lin, David B. Klenosky. Residents' perceptions and attitudes toward waste treatment facility sites and their possible conversion: a literature review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2016;20:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2016.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bubeck P., Botzen W.J.W., Aerts J.C.J.H. A review of risk perceptions and other factors that influence flood mitigation behavior. Risk Anal. 2012;32:1481–1495. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2011.01783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wachinger Gisela, Renn Ortwin, Begg Chloe, Kuhlicke Christian. The risk perception paradox—implications for governance and communication of natural hazards. Risk Anal. 2013;33:1049–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2012.01942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiuchang Wei. The present and future research on public risk perception evolution and protective action decision amid public health emergencies. Bulletin of National Natural Science Foundation of China. 2020;34:776–785. https://zkjj.cbpt.cnki.net/WKG/WebPublication/index.aspx?mid=zkjj [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avvisati Gala, Bellucci Sessa Eliana, Colucci Orazio, Marfè Barbara, Marotta Enrica, Nave Rosella, Peluso Rosario, Ricci Tullio, Tomasone Mario. Perception of risk for natural hazards in campania region (southern Italy) International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2019;40 doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2019.101164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao Shan, Li Weimin. Transitional mechanism from environmental risk to social risk. Chinese Public Administration. 2020;7:127–133. http://fdjpkc.fudan.edu.cn/2015lhlx06/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abu Emmanuel Kwasi, et al. Risk perception of COVID-19 among sub-Sahara Africans: a web-based comparative survey of local and diaspora residents. BMC Publ. Health. 2021;21 doi: 10.1186/S12889-021-11600-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zewdie Birhanu, et al. Risk perceptions and attitudinal responses to COVID-19 pandemic: an online survey in Ethiopia. BMC Publ. Health. 2021;21 doi: 10.1186/S12889-021-10939-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leila Jahangiry, Fatemeh Bakhtari, Zahara Sohrabi, Parvin Reihani, Sirous Samei, Koen Ponnet, Ali Montazeri. Risk perception related to COVID-19 among the Iranian general population: an application of the extended parallel process model. BMC Publ. Health. 2020;20 doi: 10.1186/S12889-020-09681-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inge Kirchberger, Berghaus Thomas M., von Scheidt Wolfgang, Jakob Linseisen, Christine Meisinger. COVID-19 risk perceptions, worries and preventive behaviors in patients with previous pulmonary embolism. Thromb. Res. 2021:202. doi: 10.1016/J.THROMRES.2021.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.James Kenneth, et al. COVID-19 related risk perception among taxi operators in Kingston and St. Andrew, Jamaica. Journal of transport & health. 2021;22 doi: 10.1016/J.JTH.2021.101229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karasneh Reema, et al. Media's effect on shaping knowledge, awareness risk perceptions and communication practices of pandemic COVID-19 among pharmacists. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jum’ah Ahmad A., et al. Perception of health and educational risks amongst dental students and educators in the era of COVID‐19. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2020;25:506–515. doi: 10.1111/EJE.12626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang Sun, Ting Li. Study on the emergency management for internet public opinion from the perspective of risk construction. Chinese Public Administration. 2019;9:118–122. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Miao, Zhang Hongzhong, Huang Hui. Media exposure to COVID-19 information, risk perception, social and geographical proximity, and self-rated anxiety in China. BMC Publ. Health. 2020;20 doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09761-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alyssa Bilinski, et al. Better late than never: trends in COVID-19 infection rates, risk perceptions, and behavioral responses in the USA. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2021;36 doi: 10.1007/S11606-021-06633-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karasneh Reema, et al. Media's effect on shaping knowledge, awareness risk perceptions and communication practices of pandemic COVID-19 among pharmacists. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2020;17:1897–1902. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ning L., te al. 2020. The Impacts of Knowledge, Risk Perception, Emotion and Information on Citizens' Protective Behaviors during the Outbreak of COVID-19: a Cross-Sectional Study in China. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gong Ni, Jin Xiaoyuan, Liao Jing, Li Yundong, Zhang Meifen, Cheng Yu, Xu Dong. Authorized, clear and timely communication of risk to guide public perception and action: lessons of COVID-19 from China. BMC Publ. Health. 2021;21 doi: 10.1186/S12889-021-11103-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barrios J.M., Hochberg Y.V. Risk perceptions and politics: evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Financ. Econ. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gratz Kim L., et al. Annals of behavioral medicine : a publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine; 2021. Adherence to Social Distancing Guidelines throughout the COVID-19 Pandemic: the Roles of Pseudoscientific Beliefs, Trust, Political Party Affiliation, and Risk Perceptions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akihiro Shiina, et al. Perception of and anxiety about COVID-19 infection and risk behaviors for spreading infection: an international comparison. Ann. Gen. Psychiatr. 2021;20 doi: 10.1186/S12991-021-00334-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng Yun, Fang Sha, Yin Jie. The effects of community safety support on COVID-19 event strength perception, risk perception, and health tourism intention: the moderating role of risk communication. Manag. Decis. Econ. : MD. 2021 doi: 10.1002/MDE.3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chinese Academy of Social Sciences . 2020. Survey on Changes in Social Mentality during the Epidemic.http://www.sociology2010.cass.cn/shxsw/swx_plbd/swx_sprd/202004/t20200402_5109166.html/ [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ahmad Rana Irfan, et al. COVID-19 risk perception and coping mechanisms: does gender make a difference? International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2021:55. doi: 10.1016/J.IJDRR.2021.102096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marta Caserotti, et al. Associations of COVID-19 risk perception with vaccine hesitancy over time for Italian residents. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021:272. doi: 10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2021.113688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.James Kenneth, et al. COVID-19 related risk perception among taxi operators in Kingston and St. Andrew, Jamaica. Journal of transport & health. 2021;22 doi: 10.1016/J.JTH.2021.101229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karasneh Reema, et al. Media's effect on shaping knowledge, awareness risk perceptions and communication practices of pandemic COVID-19 among pharmacists. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2021;17:1897–1902. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Xiguang, Su Jing, Wen Sanmei. Differences in public risk perception in the early stages of A outbreak—a study on the impact of COVID-19 health information adoption. Global Journal of Media Studies. 2020;22:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hou Guanghui, Wang Yuandi. Why the crisis of neighbor avoidance is intensifying——an integrated attribution model. Journal of Public Management. 2014;11:80–92. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doo-Hun Choi, Yoo Woohyun, Noh Ghee-Young, Park Keeho. The impact of social media on risk perceptions during the MERS outbreak in South Korea. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017;72:422–431. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang Sun, Ting Li. Study on the emergency management for internet public opinion from the perspective of risk construction. Chinese Public Administration. 2019;9:118–122. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peng Li, Li Wenhui. A study on intergovernmental diffusion network of interconnected risks in disastrous weather. Chinese Public Administration. 2018;2:114–119. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malecki Kristen M.C., Keating Julie A., Nasia Safdar. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America; 2021. Crisis Communication and Public Perception of COVID-19 Risk in the Era of Social Media; p. 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Janet Z., Chu Haoran. Who is afraid of the Ebola outbreak? The influence of discrete emotions on risk perception. J. Risk Res. 2018;21:834–853. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2016.1247378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He Shan, et al. Analysis of risk perceptions and related factors concerning COVID-19 epidemic in chongqing, China. J. Community Health. 2021;46:278–285. doi: 10.1007/S10900-020-00870-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siegrist Michael, Joseph Árvai. vol. 40. Risk analysis : an official publication of the Society for Risk Analysis; 2020. pp. 2191–2206. (Risk Perception: Reflections on 40 Years of Research). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Furati K.M., Sarumi I.O., Khaliq A.Q.M. Fractional model for the spread of COVID-19 subject to government intervention and public perception. Appl. Math. Model. 2021;95:89–105. doi: 10.1016/j.apm.2021.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]