Abstract

Lutein (L) and zeaxanthin (Z), as macular pigments, are water-insoluble, chemically unstable, and have low bioaccessibilities; they are often emulsified to overcome these limitations. This study investigated the impact of various emulsifiers (ethyl lauroyl arginate (LAE); Tween 80; and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)) on the physicochemical properties and in vitro digestibilities of L/Z-fortified oil-in-water emulsions. Droplet aggregation and creaming extents were dependent on the emulsifier type. The ζ-potentials of emulsions stabilized by LAE, Tween 80, and SDS were + 87, − 26, and − 95 mV, respectively. SDS-stabilized emulsion had the smallest particles, while the particle sizes for the LAE- and Tween 80-stabilized emulsions were larger and not significantly different. The rates of L/Z degradation were sensitive to the emulsifier type and to heat, not to light. The L/Z bioaccessibility was the highest for the Tween 80 emulsion. Surfactants should therefore be carefully selected to optimize L/Z physicochemical stability and bioaccessibility in emulsions.

Keywords: Carotenoids, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Ethyl lauroyl alginate (LAE), Polysorbate 80 (Tween 80), Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)

Introduction

Lutein and Zeaxanthin (L/Z) are major pigments that naturally occur in tomatoes, egg yolk, and marigold flowers, and they have characteristic yellow, red, and orange colors (Abdel-Aal et al. 2013). These are oxygenated carotenes pigments belonging to the xanthophyll class of carotenoids extracted from marigold flowers (Sajilata et al. 2008). However, they tend to be obtained in low yields, and require large areas of land in addition to significant labor input for their cultivation (Lin et al. 2015). Recently, several species of microalgae have been identified as alternative L/Z sources to replace marigold flowers, due to the fact that they possess high L/Z contents (Fernández-Sevilla et al. 2010).

Lutein and zeaxanthin are also well-known macular carotenoids, which can reduce the damage caused by ultraviolet (UV)-visible irradiation (Roberts et al. 2009), and can protect against macular degeneration (Abdel-Aal et al. 2013; Sajilata et al. 2008). Additionally, they are antioxidants capable of protecting the macular cells from oxidative stress by scavenging free radicals (Gumus et al. 2016; Weigel et al. 2018). However, since L/Z cannot be synthesized in the human body, it must be consumed directly through our diets (Nagao 2014; Sajilata et al. 2008) being 0–2 mg/kg body weight the optimal level of L/Z (Marefati et al. 2019), while the daily intake of L/Z is recommended as > 10 mg to maintain good eye health (Frede et al. 2014; Nwachukwu et al. 2016). Despite their potential benefits, several limitations exist for their application in food and beverage products, with examples including a poor water-solubility, chemical instability under heat and light exposure, and a low bioaccessibility (Frede et al. 2014). Thus, colloidal delivery or encapsulation systems has been reported to overcome these limitations (Boon et al. 2010).

In this context, binary and ternary O/W emulsions are suitable for dispersing lipophilic bioactive compounds into aqueous phases. Emulsion-based delivery systems can also protect L/Z from chemical degradation during processing, transport, and storage (Boon et al. 2010), ultimately resulting in the efficient delivery of L/Z with a high bioaccessibility into the digestive system. Thus, the selection of an appropriate emulsifier is key to preparing a stable O/W emulsion. Recent studies have shown that the different surfactant charges used to coat lipid droplets may have a pronounced influence on their physicochemical stabilities and in vitro digestion properties (Hur et al. 2009; Li and McClements 2014; Zhang et al. 2015). For example, ethyl lauroyl arginate (LAE), which is derived from lauric acid and L-arginine, is a cationic surfactant, and has been labelled “generally recognized as safe” (GRAS) for use in food applications (Bakal 2005). In addition, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) is an anionic surfactant approved by the Korea Food and Drug Administration (KFDA) for use in functional foods, while polysorbate 80 (Tween 80) is a representative non-ionic surfactant that is widely used in the food industry.

Thus, the aim of this study is to formulate L/Z-loaded O/W emulsions stabilized by food-grade emulsifiers possessing different surface charges, and then compare the emulsifying properties under different temperature and light conditions. Subsequently, the effects of these surfactants on the simulated digestion properties of L/Z-containing emulsions and on the bioaccessibility of L/Z in the gastric system are evaluated.

Materials and methods

Materials

Microalgae (Chlamydomonas reinhardtii) were kindly provided by Prof. Eon-Seon Jin (Hanyang University, Korea). Corn oil was acquired from a domestic supermarket. n-Hexane (95%) and acetone (99.8%) were purchased from Daejung Chemicals and Metals Co. Ltd. (Siheung, Korea). Iso-propanol (99.9%), potassium chloride (KCl, 99.0%), and sodium acetate trihydrate (98.5%) were purchased from Samchun Chemical Co. (Seoul, Korea). Acetic acid (99.7%) was purchased from Junsei Chemical (Tokyo, Japan). Tween 80 (Polysorbate 80, 99%) was purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). LAE (98%) was purchased from Avention Chemicals (Incheon, Korea). SDS (99%), pepsin, lipase, bile extract porcine and pancreatin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Preparation of the L/Z-loaded oil fraction

The preparation of the L/Z-loaded oil fraction is based on the methods described by Kim and Shin (2021). Microalgae powder and a 3:2 (v/v) hexane/isopropanol solvent mixture were combined in a 1:100 (w/v) ratio then mixed by sonication in an ultrasonic bath (Powersonics 505, Hwashin technology, Seoul, Korea) at 40 kHz and 350 W for 150 min at 35.7 °C. The sonicated mixture was then centrifuged at 3,500 × g for 10 min at 4 °C (R-514, Hanil comibi, Incheon, Korea), and the supernatant was collected and mixed with an equal volume of 0.88% KCl solution. To obtain the organic phase, the above mixture was transferred to a separating funnel and the upper phase was collected. The organic solvent was then evaporated using a rotary evaporator at 50 °C for 3 min. Finally, the extracted L/Z fraction was mixed with corn oil, wherein the final oil sample contained 2% L/Z extracts.

Preparation of the emulsions

The following method is an adaptation of the process described by Kim and Shin (2021) and Ziani et al. (2011) with modifications. Each emulsifier (1.66, 0.53, and 2.43 mM of LAE, Tween 80, and SDS, respectively) was dispersed in 10 mM acetate buffer at pH 4.0. The emulsions were prepared using 20% (w/w) oil phase and 80% (w/w) aqueous phase with an Ultra-turrax T25 homogenizer (IKA Labortechnik, Germany) at 6,000 rpm for 2 min. After this time, a probe sonicator (VCX 130, Sonic & Materials, Inc.) with a 6 mm diameter tip was used for further emulsification at 130 W and 20 kHz. To avoid the effects of temperature, the beaker containing the pre-mixed and homogenized emulsion was placed in a small box with ice. The final L/Z content was 20 mg in 250 mL of emulsion.

Emulsifying properties

To measure the emulsifying activity, the turbidity was measured spectrophotometrically at 500 nm using a slightly modified procedure by Wang et al. (2008). More specifically, an aliquot of the emulsion (20 μL) was taken immediately taken after preparation, and a further aliquot (20 μL) was taken after 2 h. Each sample was then diluted 1:100 (v/v) in a 0.1 wt% SDS solution, and the emulsifying activity index (EAI) and the emulsion stability index (ESI) were calculated accordingly to the following equations:

where A0 and A2h are the absorbances (500 nm) of the diluted emulsions at 0 and 2 h, respectively, DF is the dilution factor (100), c is the initial emulsifier concentration (0.7 g/mL), Ø is the optical path (0.01 m), and is the fraction of oil used to prepare the emulsion (0.2).

Physical stability

Determination of the ζ-potential

The emulsion droplets’ electrical charge (ζ-potential) was measured using a particle electrophoresis instrument (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern Instruments Ltd., Worcestershire, UK). To avoid multiple scattering effects, the emulsions were diluted 100-fold using a buffer solution (10 mM acetate, pH 4).

Determination of the particle size

The mean particle diameters (Z-averages) of the emulsions were evaluated using a Zetasizer Nano ZS dynamic light scattering device (Model Zen 1690, Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). The emulsions were diluted using a buffer solution (10 mM acetate buffer, pH 4) prior to analysis to avoid the effects of multiple scattering. All measurements were carried out at 23–25 °C.

Visual assessment of creaming

Fresh emulsions were poured into 5 mL glass test tubes (13 mm in diameter and 90 mm in height) prior to static dark storage at 25 °C for 15 day. Due to creaming boundaries moving over time, the extent of creaming was described by the creaming index (CI, %), calculated according to the following equation:

where the Hc is the height of the creaming layer, and Ht is the total height of the emulsion.

Chemical stability

The chemical stability of L/Z was evaluated by measuring the decrease of the L/Z content in each emulsion during 15 day of storage. Emulsions were stored at different temperatures (4, 25, and 37 °C in dark conditions. Another set of samples was stored in illuminated conditions at 25 °C. All samples were flushed with N2 prior to storage. For analysis of the L/Z content, an aliquot (100 μL) of the emulsion was added to acetone (1.9 L), and the L/Z content was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). During storage, samples of the emulsions were collected for analysis at 3 day intervals.

In vitro digestion procedure

The in vitro gastrointestinal model, which was based on a previous literature report mat 2016, was carried out to assess the influence of the interface of the emulsion on the bioaccessibility of L/Z. This study did not include the oral phase since the residence period in the oral cavity of most liquids is short (Minekus et al. 2014).

Gastric phase

To simulate the gastric phase, an aliquot (5 mL) of the emulsion was placed in a brown medium bottle and mixed with simulated salivary fluid (SSF, 5 mL), simulated gastric fluid (SGF, 7.5 mL), CaCl2 (5 μL, 0.3 M), HCl (0.2 mL, 2 M), and distilled water (0.695 mL). Subsequently, an aliquot (1.6 mL) of the pepsin solution dissolved in SGF (see above) was added (final activity = 2500 U/mL), and the total volume of the gastric phase (chyme) was 20 mL. The pH of this solution was adjusted with a 1 M HCl solution to obtain a pH of 3. The bottle containing the chyme was flushed with N2 and stirred at 250 rpm in the end-over-end mode at 37 °C for 2 h.

Small intestinal phase

For the small intestinal phase, the simulated intestinal fluid (11 mL, SIF) was added to the chyme. Subsequently, an aliquot of the bile solution (2.5 mL, 1 M) was added along with CaCl2 (40 μL, 0.3 M), NaOH (0.15 mL, 1 M), and distilled water (1.31 mL). Next, an aliquot (5 mL) of a pancreatic solution was added. This solution comprised a mixture of pancreatin (pancreatin from porcine pancreas, batch #SLBZ5739, Sigma Aldrich) and pancreatic lipase (lipase from porcine pancreas type II, batch #SLBZ7249, Sigma Aldrich) with a final lipase activity of 100 U/ml, hence, 2000 U/mL was the final lipase activity in the digest, which reached a volume of 40 mL. A 1 M NaOH solution was added to obtain a pH of 7. The bottle was then flushed with N2 and stirred at 250 rpm in the end-over-end mode at 37 °C for 2 h. The pH of the mixture was measured and recorded over 2 h to identify the volume of a 0.25 M NaOH solution (mL) required to neutralize the free fatty acids (FFA) released by lipid digestion; hence maintaining a pH of 7.0. The calculation followed the subsequent equation:

where VNaOH is the volume of titrant (L), MNaOH is the molarity of sodium hydroxide, Mlipid is the molecular weight of the oil (800 g/mol), and Wlipid is the weight of oil in the digestion system (g).

Bioaccessibility

The bioaccessibility of L/Z was evaluated after the emulsion samples had passed through the simulated gastric and small intestine phase in vitro digestion model. Aliquots (2 mL) from the digested emulsion samples were subjected to centrifugation (1200 × g for 30 min at 25°) using a bench top centrifuge (H-15FR, Kokusan Co., Saitama, Japan). After centrifugation, the bottom sediment phase and the top clear micelle phase were separated, and the micelle phase was mixed with acetone (99.9%). The bioaccessibility of L/Z remaining in the intestinal phase was then determined by HPLC and the following equation (Minekus et al. 2014):

where Cm is the L/Z concentration in the micelle phase and Ci is the initial concentration of L/Z, which is considered to be the raw digesta (Pool et al. 2013).

HPLC analysis

The emulsions were subjected to HPLC analysis. Previous to the analysis, each emulsion was diluted 20-fold in 99.7% (v/v) acetone and filtered through a 0.2 μm nylon filter. HPLC analysis was performed as described previously Baek et al. (2018)on a Shimadzu Prominence HPLC model LC-20AD (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Inc. Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a Spherisorb 5.0 μm ODS1 4.6 × 250 mm cartridge column (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). The separation of pigments started (0–15 min) by using a mixture comprising 14% 0.1 M Tris–HCl at pH 8.0, 84% acetonitrile and 2% methanol followed by a mixture containing 68% methanol and 32% acetonitrile (15–19 min). Subsequently, a post-run was performed for 6 min using the initial solvent mixture. A flow rate of 1.2 mL/min was employed throughout. The absorbance for the detection of the pigments was 445 and 670 nm. HPLC profiles were calibrated for the pigments with the use of chlorophyll and carotenoid standards (DHI, Denmark) from which the concentrations of the individual pigments were determined.

Statistical analysis

All data were reported as means ± standard deviations. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (Version 21.0, IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). The results were analyzed by ANOVA and Duncan’s multiple range tests. In addition, an independent t-test was used to compare between the control and experimental groups and the D 0 and D 15 mean diameters. Statistical significance was accepted as p < 0.05. All samples were run in triplicate.

Results and discussion

Initial properties of emulsions containing L/Z

The effect of the initial emulsion composition on the L/Z concentration in each emulsion-based delivery systems was confirmed by HPLC analysis (data not shown). L/Z was extracted from C. reinharditii and was dispersed to a final concentration (w/v) of 0.4 mg/mL in corn oil. The final emulsion contained an L/Z concentration of 80 mg/L, which was determined based on the recommended acceptable daily intake of L/Z (Frede et al. 2014; Marefati et al. 2019).

Table 1 presents the ζ-potentials of the three surfactant-stabilized emulsions. The electrical charges on the emulsion droplets stabilized by LAE, Tween 80, and SDS were determined to be approximately + 87, − 26, and − 95 mV, respectively. Although the charge of Tween 80 is expected to be small, since it is a non-ionic surfactant, previous research has found that, under neutral conditions, anionic impurities in the oil (such as FFAs) or in the surfactant, as well as a preferential adsorption of hydroxyl ions from water may be the reason for an appreciable negative charge (Hsu and Nacu, 2003). The physical and chemical stabilities of oil droplets are greatly influenced by their charge. In the case of droplets with high negative charge (as found in SDS) aggregation can be prevented due to strong electrostatic repulsion between them (Uskoković 2012). However, lipid oxidation can also be stimulated by high negative charge since the surface of the droplets could attract cationic transition metals, prompting the interaction with the carotenoids present inside (Mei et al. 1999).

Table 1.

Emulsifying activity index (EAI), emulsifying stability index (ESI), and Zeta potential for each O/W emulsion formed using LAE, Tween 80, and SDS, in addition to changes in the particle size over 15 days

| Surfactant type | EAI | ESI | Zeta potential (mV) | Particle size (μm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day 15 | ||||

| LAE | 14.608 ± 0.367 | 0.954 ± 0.022 | + 86.83 ± 5.12 | 0.357 ± 0.045 | 0.314 ± 0.067 |

| Tween 80 | 14.664 ± 0.336 | 0.980 ± 0.016 | − 25.53 ± 1.72 | 0.428 ± 0.038 | 0.344 ± 0.011* |

| SDS | 15.096 ± 0352 | 0.983 ± 0.017 | − 95.20 ± 1.97 | 0.289 ± 0.044 | 0.316 ± 0.028 |

*Significant differences (p < 0.05)

At first, the droplets of all of the prepared emulsions were relatively small (< 0.6 μm), which is suitable for the prevention of droplet aggregation and creaming, hence desired for producing commercial foods that are stable (McClements 2015). Nevertheless, the initial mean droplet diameters among the LAE-, Tween 80-, and SDS-stabilized emulsions was different (i.e., 0.36, 0.43, and 0.28 μm, respectively). Particle size measurements of the emulsions during storage indicated that LAE and SDS resulted in the formation of physically stable emulsions, and no statistically significant changes were observed in their mean particle diameters over time (p > 0.05) (Table 1). In contrast, appreciable decreases in the mean particle size were observed for the Tween 80-stabilized emulsion during storage. These results suggest that larger particles may have existed in the form of a cream in the upper phase, meaning that comparatively smaller-sized droplets would have been present in the lower phase, which has been previously attributed to oiling off and droplet coalescence under long storage (Weigel et al. 2018).

Creaming analysis of emulsions containing L/Z

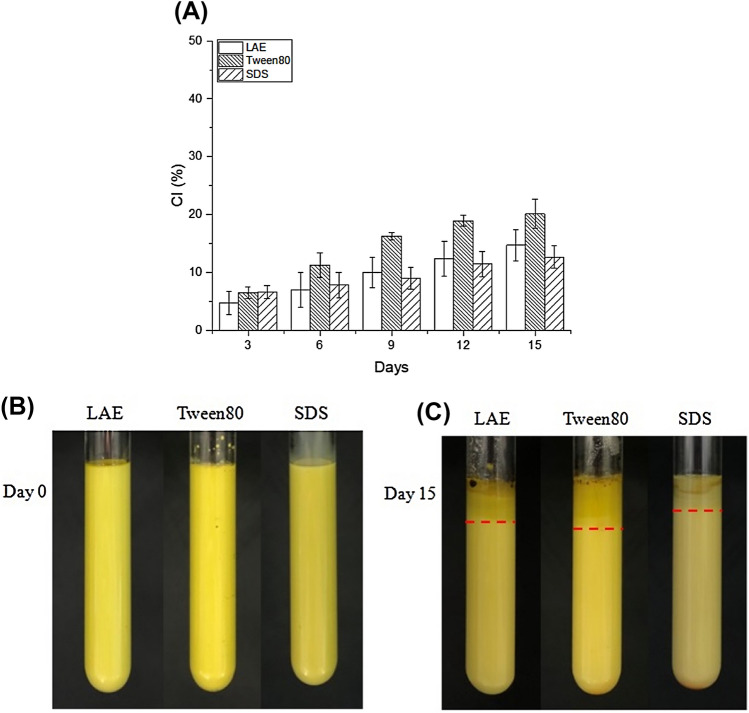

Emulsion-based delivery systems rely on their physical stabilities to be effectively applied in food and beverage products available in the market. Therefore, it is crucial that such systems remain physically stable during manufacture, transport, storage, and consumption (McClements 2015). The changes in the stabilities of the L/Z enriched emulsions were therefore measured using the creaming index (CI, %) throughout storage at 25 °C in dark conditions (Fig. 1A). In all of the emulsion types stabilized by LAE, Tween 80, and SDS, the CI increased gradually during storage. Although no significant differences were observed between the emulsions stabilized by LAE and SDS, a thicker cream layer was observed for the Tween 80-stabilized emulsion. The aforementioned observation supports this result, wherein Tween 80 stabilized the emulsion in the form of large droplets, and therefore, the large droplets in the initial system would be inclined to coalesce more briskly to give a thick cream layer (Weigel et al. 2018). Additionally, due to the fact that stable emulsions are formed in the ζ-potential range of ± 30 mV (Kumar and Dixit 2017), LAE (− 87 mV) and SDS (− 95 mV) gave physically stable emulsions, while the Tween 80 (− 25 mV) emulsion deviated from this range, and aggregates formed between its particles.

Fig. 1.

(A) Creaming of L/Z in emulsions stabilized by LAE, Tween 80, and SDS. Data represent means ± standard deviation. (B, C). Appearances of the L/Z enriched emulsions stabilized by different emulsifiers (LAE, Tween 80, and SDS) at storage days 0 and 15, respectively

The appearance of the emulsions before and after storage can be seen in Fig. 1B and Fig. 1C, respectively. The visual examination show that their appearances changed considerably. All emulsion samples demonstrated droplet creaming, although, for the emulsions stabilized by SDS and Tween 80 no oiling off was observed. In contrast, at the top of the LAE emulsion, a distinct oil layer was observed after storage, suggesting droplet coalescence caused by the inability of LAE to form sufficiently vigorous interfacial layers to protect the emulsion against this destabilization phenomenon. Possibly, the quantity of surfactant present in the emulsion was not sufficient to completely cover the surfaces of all droplets (Weigel et al. 2018). Moreover, upon measurement of the emulsifying activity index (EAI) and the emulsifying stability index (ESI), it was apparent that the LAE emulsion showed no statistically significant difference, but its corresponding values were lower than those of the Tween 80 and SDS emulsions (Table 1). In other words, the oil layer was observed because it formed a more unstable emulsion. It is suggested that forthcoming studies investigate the influence of the concentration of emulsifiers on the physical and chemical stabilities of L/Z-loaded emulsions.

Chemical stability of L/Z

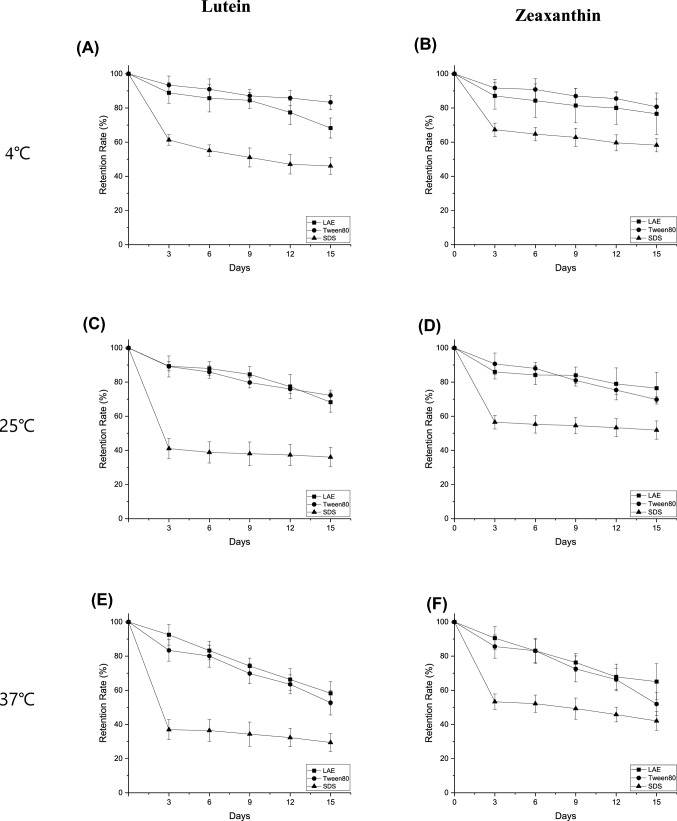

The degradation of L/Z in each oil-in-water emulsion was assessed by measuring the loss of L/Z during storage under different temperatures (Fig. 2) and light (Fig. 3) conditions. It was found that the degradation rates were fairly similar between L and Z, and that they clearly increased upon increasing the storage temperature. As shown in Figs. 2A–2B and 2E–2F, the emulsion degradation rate at 4 °C was significantly lower than that at 37 °C. Furthermore, the surfactant type had great impact on the degradation rate of L/Z in the O/W emulsions. More specifically, the degradation rates of L/Z were comparable in the LAE-, and Tween 80-stabilized emulsions after 15 days of storage under different temperature and light conditions, but was appreciably faster in the SDS emulsion during the initial 3 day. It was therefore considered that a physicochemical phenomenon that may account for a faster degradation of L/Z in the SDS-stabilized emulsion was the binding of SDS to L/Z, which would be a concentration-dependent process (Fish 2006; Takagi et al. 1982). Indeed, it was confirmed that the SDS-stabilized emulsion produced a red sediment (Fig. 3C), which perhaps contained carotenoid pigments, such as L/Z. The observation of this sediment may therefore account for the faster L/Z degradation rate observed for the SDS-emulsion exhibited.

Fig. 2.

Degradation of L/Z in emulsions stabilized by LAE, Tween 80, and SDS. Data represent means ± standard deviation. L/Z retention rates at (A, B) 4 °C, (C, D) 25 °C and (E, F); 37 °C

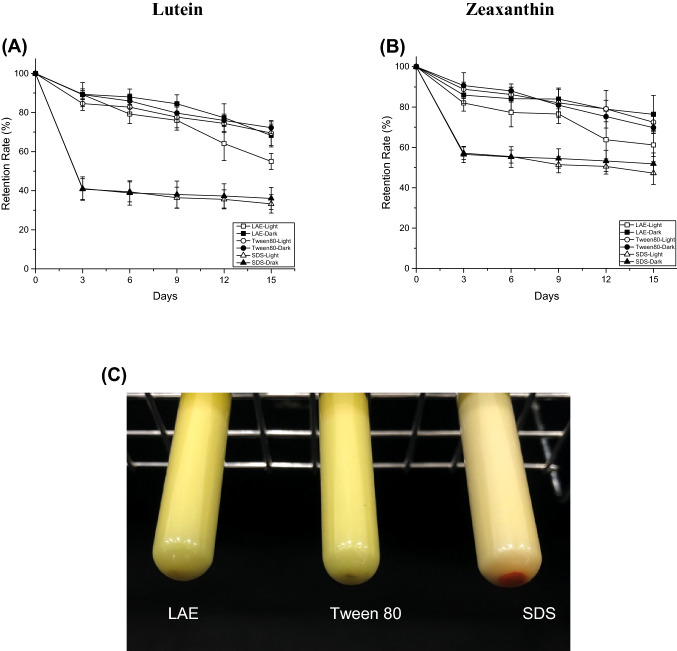

Fig. 3.

Degradation of L/Z in emulsions stabilized by LAE, Tween 80, and SDS. Data represent means ± standard deviation. (A, B) L/Z retention rates under light condition (884 Lux) at 25 °C (C) Visual image of the emulsions stored at 25 °C under dark conditions. The red sediment contains L/Z

As shown in Fig. 3, there were no significant differences in the degradation of L/Z during storage under light and dark conditions. It was expected that faster L/Z degradation would occur under light conditions, but this does not appear to be the case.

Oxidation is another factor that has the potential to influence the rate of L/Z degradation. L/Z belongs to the carotenoid class of molecules; thus oxidation of these species can occur via autoxidation or singlet oxygen which consequentially decrease the quality of food products that are enriched with carotenoids (Boon et al. 2010; Sajilata et al. 2008). Therefore, further studies are required to elucidate whether this mechanism is important, and how it varies depending on the emulsifier type.

In vitro digestion and bioaccessibility of L/Z

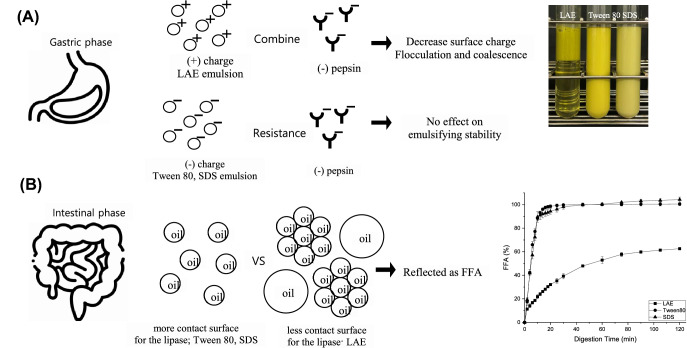

Since the delivery of bioactive compounds in vivo is challenging due to their degradation during digestion, an in vitro gastro-intestinal digestion experiment was carried out to contrast the influence of each emulsifier on the stability of the emulsion during digestion. Figure 4A shows the states of the emulsions stabilized by LAE, Tween 80, and SDS after gastric digestion. Only LAE, which coated the lipid droplets, showed phase separation. In contrast, the lipid droplets were more stable when the Tween 80 and SDS emulsifiers were used. The phase separation observed for LAE was therefore accounted for by considering that LAE exhibits a positive electric charge in the ζ-potential employed (+ 87 mV), which, combined with the negatively-charged pepsin present in the gastric fluid, results in flocculation and coalescence, followed by phase separation (Fig. 4A; LAE). In contrast, Tween 80 and SDS exhibited negative ζ-potentials similar to pepsin and would therefore be expected not to interact with it.

Fig. 4.

In vitro digestion. (A) Visual image after the gastric digestion processes. (B) Free fatty acid (FFA) release during the intestinal stage of the in vitro digestion model of L/Z-enriched emulsions stabilized by LAE, Tween 80, and SDS. Data represented by means ± standard deviation

The release of FFAs can be considered a measure of the degree of digestion of the lipid droplets by pancreatin and lipase. Thus, the degree of FFA release was calculated from the volume of sodium hydroxide added to neutralize the pH of the solution during the intestinal phase. The digestion rate (i.e., FFA release) has been reported to depend on factors such as the lipid droplet size and the interfacial structure (Minekus et al. 2014), since the coalescence and flocculation of lipid droplets reduces the surface area in contact with the digestive enzymes (Lamothe et al. 2019; Li et al. 2011; Marefati et al. 2019). As shown in Fig. 4B, a rapid increase in FFA release was observed during the initial 10 min of digestion on the lipid droplets coated with Tween 80 and SDS, which suggests that the triglycerides were quickly hydrolyzed by the lipase. Nevertheless, the LAE-stabilized emulsion showed a slow FFA release over 2 h. As described earlier and illustrated in Fig. 4A, the LAE-stabilized emulsion underwent phase separation due to flocculation and coalescence. The separated oil appeared to undergo reduced degradation in the intestinal phase, thereby suggesting that the surface area of the oil separated from the LAE-coated emulsion was not sufficiently large to allow contact with the enzymes. In contrast, the lipid droplets coated with Tween 80 and SDS were stable after gastric digestion, and their surface areas were large enough to enable sufficient contact with the enzymes.

The bioaccessibility of a substance corresponds to the fraction released from an ingested food that is present within the intestinal fluids in a form suitable for absorption. Since L/Z are a mixture of lipophilic bioactive compounds, their bioaccessibility is usually assumed to be the fraction that is solubilized within dietary mixed micelles in the small intestine. In other words, the bioaccessibility of L/Z is associated to the degree of lipid digestion and can be explained by the release of lipophilic bioactive compounds that are present in the lipid droplets (McClements 2018). According to a previous report (Joye et al. 2014), the bioaccessibility can be examined by measuring the amount of bioactive compound present in the mixed micelle phase after completion of the stage-by-stage in vitro digestion process (Table 2). The bioaccessibilities of the LAE and Tween 80 emulsions were determined to be 11 and 23%, respectively, which was correlated with a two-fold difference in the degree of lipolysis for the same emulsions. However, the SDS-stabilized emulsion, which exhibited a similar degree of lipolysis to the Tween 80 emulsion, possessed the lowest bioaccessibility. The elution of L/Z therefore appears to have been hampered by the formation of a sediment in SDS, which dissolved in the intestinal fluid, as described earlier (Fig. 3C) (Fish 2006; Takagi et al. 1982). Therefore, it can be concluded that SDS binds with L/Z to form a sediment, thereby rendering SDS an ineffective emulsion. In the future, comparisons with other negatively-charged emulsifiers should be performed to determine whether a similar behavior is observed.

Table 2.

L/Z contents during in vitro digestion after the intestinal phase (bioaccessibility, %)

| Surfactant type | Bioaccessibility % |

|---|---|

| LAE | 11.31 ± 1.54a |

| Tween 80 | 22.68 ± 0.76a |

| SDS | 9.05 ± 1.84b |

abDifferent letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05)

Our findings therefore confirmed that the ionic and non-ionic emulsifiers examined herein resulted in unique emulsifying properties and physiological effects in the gastric tract, implying that selection of the optimal emulsifier is necessary to formulate functional emulsions to deliver bioactive materials to target organs. In addition, more stable emulsion systems, such as double-layered emulsions, should be considered to exclude unexpected precipitation through charge interactions between L/Z and the emulsifier, and to maximize the physicochemical and physiological stabilities of L/Z-based emulsions.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Su-Jin Jeong, Email: sjgod4018@naver.com.

Sunbin Kim, Email: b07293@gmail.com.

Esteban Echeverria-Jaramillo, Email: estebangej@hanyang.ac.kr.

Weon-Sun Shin, Email: hime@hanyang.ac.kr.

References

- Abdel-Aal E-SM, Akhtar H, Zaheer K, Ali R. Dietary sources of lutein and zeaxanthin carotenoids and their role in eye health. Nutrients. 2013;5:1169–1185. doi: 10.3390/nu5041169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek K, Yu J, Jeong J, Sim SJ, Bae S, Jin ES. Photoautotrophic production of macular pigment in a Chlamydomonas reinhardtii strain generated by using DNA-free CRISPR-Cas9 RNP-mediated mutagenesis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2018;115:719–728. doi: 10.1002/bit.26499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakal, G., and A.D. The lowdown on lauric arginate. Food Quality and Safety. 12, 54-61. (2005)

- Boon, C.S., McClements, D.J., Weiss, J., Decker, E.A. Factors influencing the chemical stability of carotenoids in foods. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 50: 515-532. (2010) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Sevilla JM, Acién Fernández FG, Molina Grima E. Biotechnological production of lutein and its applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;86:27–40. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2420-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish WW. Interaction of sodium dodecyl sulfate with watermelon chromoplasts and examination of the organization of lycopene within the chromoplasts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:8294–8300. doi: 10.1021/jf061468+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frede K, Henze A, Khalil M, Baldermann S, Schweigert FJ, Rawel H. Stability and cellular uptake of lutein-loaded emulsions. Journal of Functional Foods. 2014;8:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2014.03.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gumus CE, Davidov-Pardo G, McClements DJ. Lutein-enriched emulsion-based delivery systems: Impact of Maillard conjugation on physicochemical stability and gastrointestinal fate. Food Hydrocoll. 2016;60:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.03.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu JP, Nacu A. Behavior of soybean oil-in-water emulsion stabilized by nonionic surfactant. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003;259:374–381. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9797(02)00207-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur SJ, Decker EA, McClements DJ. Influence of initial emulsifier type on microstructural changes occurring in emulsified lipids during in vitro digestion. Food Chem. 2009;114:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.09.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joye IJ, Davidov-Pardo G, McClements DJ. Nanotechnology for increased micronutrient bioavailability. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2014;40:168–182. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2014.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Shin WS. Formation of a novel coating material containing lutein and zeaxanthin via a Maillard reaction between bovine serum albumin and fucoidan. Food Chem. 2021;343:128437. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, A., & Dixit, C.K. Methods for characterization of nanoparticles. Advances in nanomedicine for the delivery of therapeutic nucleic acid. pp. 43–58. (2017)

- Lamothe S, Desroches V, Britten M. Effect of milk proteins and food-grade surfactants on oxidation of linseed oil-in-water emulsions during in vitro digestion. Food Chem. 2019;294:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.04.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Hu M, McClements DJ. Factors affecting lipase digestibility of emulsified lipids using an in vitro digestion model: Proposal for a standardised pH-stat method. Food Chem. 2011;126:498–505. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.11.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, McClements DJ. Modulating lipid droplet intestinal lipolysis by electrostatic complexation with anionic polysaccharides: Influence of cosurfactants. Food Hydrocoll. 2014;35:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2013.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JH, Lee DJ, Chang JS. Lutein production from biomass: Marigold flowers versus microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2015;184:421–428. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.09.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marefati A, Wiege B, Abdul Hadi N, Dejmek P, Rayner M. In vitro intestinal lipolysis of emulsions based on starch granule Pickering stabilization. Food Hydrocoll. 2019;95:468–475. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.04.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McClements, D.J. Food emulsions: principles, practices, and techniques. 3rd ed. CRC press, Boca Raton, FL, U.S.A. pp. 579 (2015)

- McClements DJ. Enhanced delivery of lipophilic bioactives using emulsions: A review of major factors affecting vitamin, nutraceutical, and lipid bioaccessibilit. Food Funct. 2018;9:22–41. doi: 10.1039/C7FO01515A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei L, McClements DJ, Decker EA. Lipid oxidation in emulsions as affected by charge status of antioxidants and emulsion droplets. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999;47:2267–2273. doi: 10.1021/jf980955p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minekus M, Alminger M, Alvito P, Ballance S, Bohn T, Bourlieu C, Carrière F, Boutrou R, Corredig M, Dupont D, Dufour C, Egger L, Golding M, Karakaya S, Kirkhus B, Le Feunteun S, Lesmes U, MacIerzanka A, MacKie A, Marze S, McClements DJ, Ménard O, Recio I, Santos CN, Singh RP, Vegarud GE, Wickham MSJ, Weitschies W, Brodkorb A. A standardised static in vitro digestion method suitable for food-an international consensus. Food Func. 2014;5:1113–1124. doi: 10.1039/C3FO60702J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao A. Bioavailability of dietary carotenoids: Intestinal absorption and metabolism. Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. 2014;48:385–392. doi: 10.6090/jarq.48.385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nwachukwu ID, Udenigwe CC, Aluko RE. Lutein and zeaxanthin: Production technology, bioavailability, mechanisms of action, visual function, and health claim status. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016;49:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2015.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pool H, Mendoza S, Xiao H, McClements DJ. Encapsulation and release of hydrophobic bioactive components in nanoemulsion-based delivery systems: Impact of physical form on quercetin bioaccessibility. Food Funct. 2013;4(1):162–174. doi: 10.1039/C2FO30042G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RL, Green J, Lewis B. Lutein and zeaxanthin in eye and skin health. Clin. Dermatol. 2009;27:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajilata MG, Singhal RS, Kamat MY. The carotenoid pigment zeaxanthin–A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2008;7:29–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2007.00028.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takagi S, Shiroishi M, Takeda K. Aggregation, Configuration and Particle Size of Lutein Dispersed by Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate in Various Salt Concentrations. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1982;46:2217–2222. [Google Scholar]

- Uskoković V. Dynamic Light Scattering Based Microelectrophoresis: Main Prospects and Limitations. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2012;33:1762–1786. doi: 10.1080/01932691.2011.625523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XS, Tang CH, Li BS, Yang XQ, Li L, Ma CY. Effects of high-pressure treatment on some physicochemical and functional properties of soy protein isolates. Food Hydrocoll. 2008;22:560–567. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2007.01.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weigel F, Weiss J, Decker EA, McClements DJ. Lutein-enriched emulsion-based delivery systems: Influence of emulsifiers and antioxidants on physical and chemical stability. Food Chem. 2018;242:395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Zhang Z, Zhang H, Decker EA, McClements DJ. Influence of emulsifier type on gastrointestinal fate of oil-in-water emulsions containing anionic dietary fiber (pectin) Food Hydrocoll. 2015;45:175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2014.11.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ziani K, Chang Y, McLandsborough L, McClements DJ. Influence of surfactant charge on antimicrobial efficacy of surfactant-stabilized thyme oil nanoemulsions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011;59(11):6247–6255. doi: 10.1021/jf200450m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]