Abstract

Tumors growing in a sheet-like manner on the surface of organs and tissues with complex topologies represent a difficult-to-treat clinical scenario. Their complete surgical resection is difficult due to the complicated anatomy of the diseased tissue. Residual cancer often responds poorly to systemic therapy and locoregional treatment is hindered by the limited accessibility to microscopic tumor foci. Here we engineered a peptide-based surface-fill hydrogel (SFH) that can be syringe- or spray-delivered to surface cancers during surgery or used as a primary therapy. Once applied, SFH can shape change in response to alterations in tissue morphology that may occur during surgery. Implanted SFH releases nanoparticles composed of miRNA and intrinsically disordered peptides that enter cancer cells attenuating their oncogenic signature. With a single application, SFH shows efficacy in four preclinical models of mesothelioma demonstrating a therapeutic impact of local application of tumor-specific miRNA, which might change the treatment paradigm for mesothelioma and possibly other surface cancers.

Introduction

Cancers spreading across complex anatomic surfaces, covering them in a sheet-like manner, represent formidable clinical scenarios beyond the typical challenges posed by most solid spherically-shaped tumors. For example, mesothelioma1, stage IVa thymoma2, disseminated ovarian cancer3, and colorectal cancer metastasizing to the peritoneum4 are surface malignancies without truly effective treatments. Surgical resection is required for any meaningful survival as part of multi-modality therapy5–7, but is exceedingly difficult. In contrast to spherical masses, achieving tumor-free margins is technically precluded because of these cancers’ unique anatomy, leading to inevitable local recurrence. Further, systemically administered chemotherapy often cannot access sites of residual cancer, especially for disseminated peritoneal cancers where the peritoneal-plasma barrier is difficult to breach8. Treating residual cancer during the resection surgery with a therapy that could be applied locally by the surgeon has immense potential to be clinically impactful9. To be effective, such a therapy would need to reach microscopic tumor foci hidden within the tortuous tissue surfaces remaining after resection.

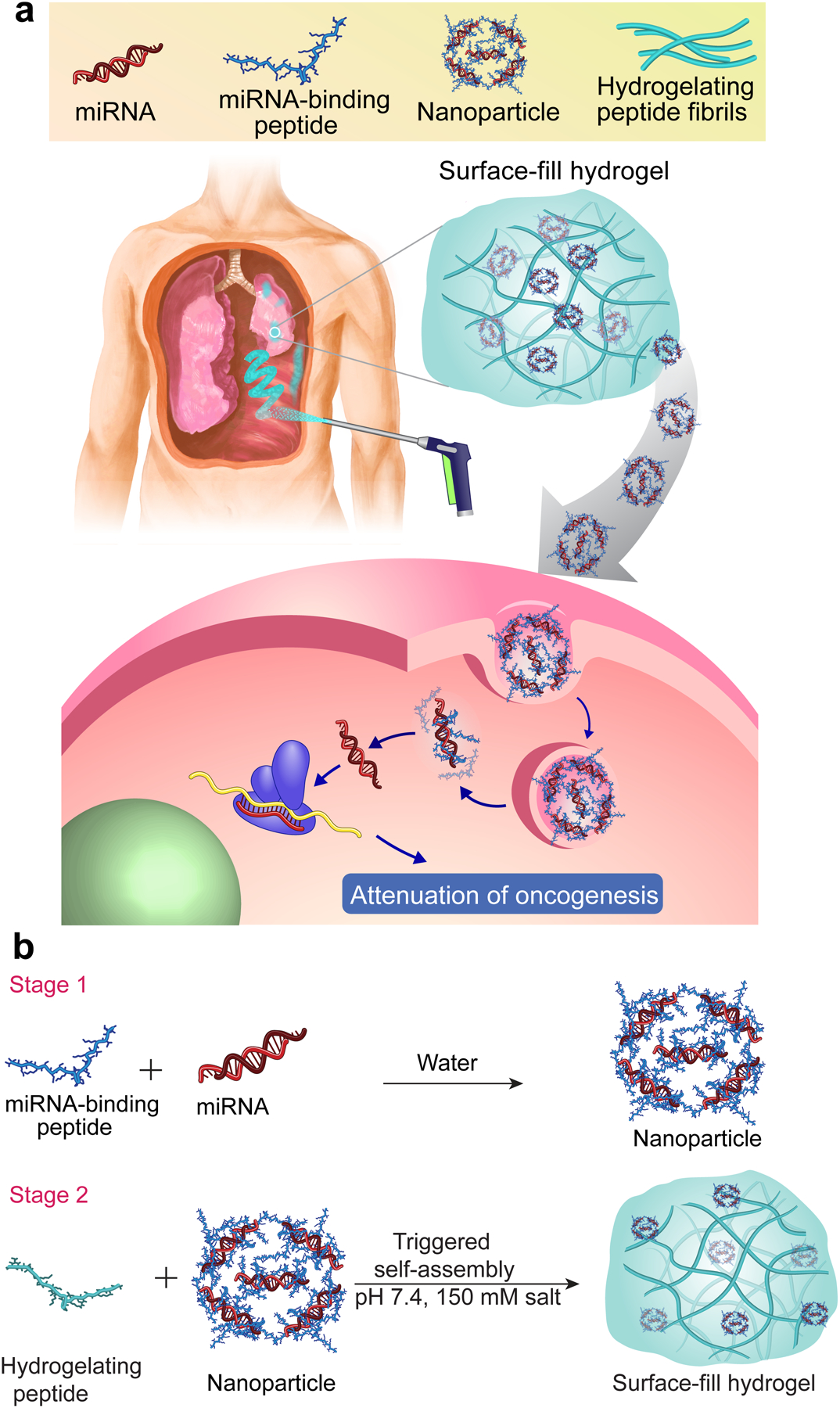

This adjuvant therapy perspective was the impetus to develop a new materials platform, a surface-fill hydrogel (SFH) that can be sprayed or syringe-injected to large anatomically complex surfaces and deliver therapy, Fig. 1a. SFH demonstrates shear-thin/recovery mechanical behavior that allows it to fill small gaps and crevices during its application, and shape-change after it has been applied to accommodate tissue anatomy alterations. Seminal to the design of the SFH are encapsulated miRNA nanoparticles that can be released from the hydrogel network, enter cells and attenuate the oncogenic signature of cancer. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short, noncoding RNA that regulate genes by simultaneously targeting multiple mRNA transcripts. They non-coding RNAs that can influence signaling pathways which are dysregulated in cancer10, 11 and are actively being leveraged as potential therapeutics12. SFH nanoparticles are prepared by condensing highly negatively charged miRNA with de novo designed positively charged intrinsically disordered peptide amphiphiles. Resulting nanoparticles are encapsulated into a fibrillar hydrogel network formed by a self-assembling peptide that defines the macroscopic mechanical attributes of the material, Fig. 1b.

Fig. 1. Application of surface-fill hydrogel to complex surface cancer.

a, Surface-fill hydrogel (SFH) can be sprayed (or syringe-injected) into the pleural cavity as a primary treatment or adjuvant after surgical debulking of mesothelioma. SFH uniformly covers and fills complex tissue surfaces to effectively deliver miRNA nanoparticles to tumor cell foci. Cell entry and endosomal escape allows miRNA-mediated attenuation of genes important to oncogenesis. b, Two-stage process to prepare SFH. Nanoparticles are prepared in Stage 1 by complexing chemically modified double stranded miRNA to intrinsically disordered peptide. In stage 2, particles are subsequently encapsulated into a fibrillar hydrogel prepared by the triggered assembly of a second distinct peptide.

We study the physical, biological, and preclinical efficacy of SFH in the context of pleural mesothelioma, a recalcitrant, asbestos-related surface malignancy. Its worldwide incidence continues to rise unexpectedly and prognosis remains dismal with a median survival of about 12 months13. This cancer occurs on surfaces of the pleural cavity, the space between the thoracic organs and the chest wall. Surgical resection of pleural mesothelioma involves lung deflation to access the pleural space followed by mechanically stripping the tumor sheet. Lung inflation restores native anatomic relationships after the procedure. Resection of primary tumor leaves behind residual microscopic tumor leading to cancer recurrence in up to 75% of patients14. To improve and prolong the beneficial effect of surgery, several intracavitary adjuvants have been investigated, including heated chemotherapy, photodynamic light or immunotherapy, but these remain experimental without widespread adoption15,16. Further, the therapeutic approach to and limitations thereof related to peritoneal mesothelioma, occurring on the surface lining between the abdominal wall and internal organs, is similar15, 17. Thus, new primary treatments against unresected native tumor and/or adjuvant therapies coupled with resection surgery for both pleural and peritoneal cancers would be clinically impactful and possibly alter treatment paradigms15, 18. We19, 20 and others21 have identified miRNAs that antagonize the oncogenic signature of pleural mesothelioma. For example, miRNA-215p, defined as miRNA-215 throughout, mitigates mesothelioma proliferation by activating p53-dependent apoptosis (90% of pleural mesothelioma cases retain wild-type p5322) and silencing multiple cell cycle-associated genes. In addition, miRNA-206 is among the most under-expressed miRNAs in human pleural mesothelioma23 that functions as a tumor suppressor by interfering with cell cycle pathways and inducing G1/S phase arrest. Therefore, miRNA-215 and miRNA-206 represent a novel class of anti-cancer agent that could potentially be used as a surgical adjuvant if it could be effectively delivered to debulked tissue surfaces, or conceivably, employed as a new primary treatment against the native tumor. As will be shown, SFH can locally deliver miRNA-215 and miRNA-206 affecting sustained therapeutic effects with a single administration in multiple preclinical models of mesothelioma. Importantly, SFH allows the demonstration that a locoregional, type-specific molecular therapy is efficacious against surface cancers, a distinct class of tumor that continues to defy modern treatments.

Design of peptide/miRNA nanoparticle.

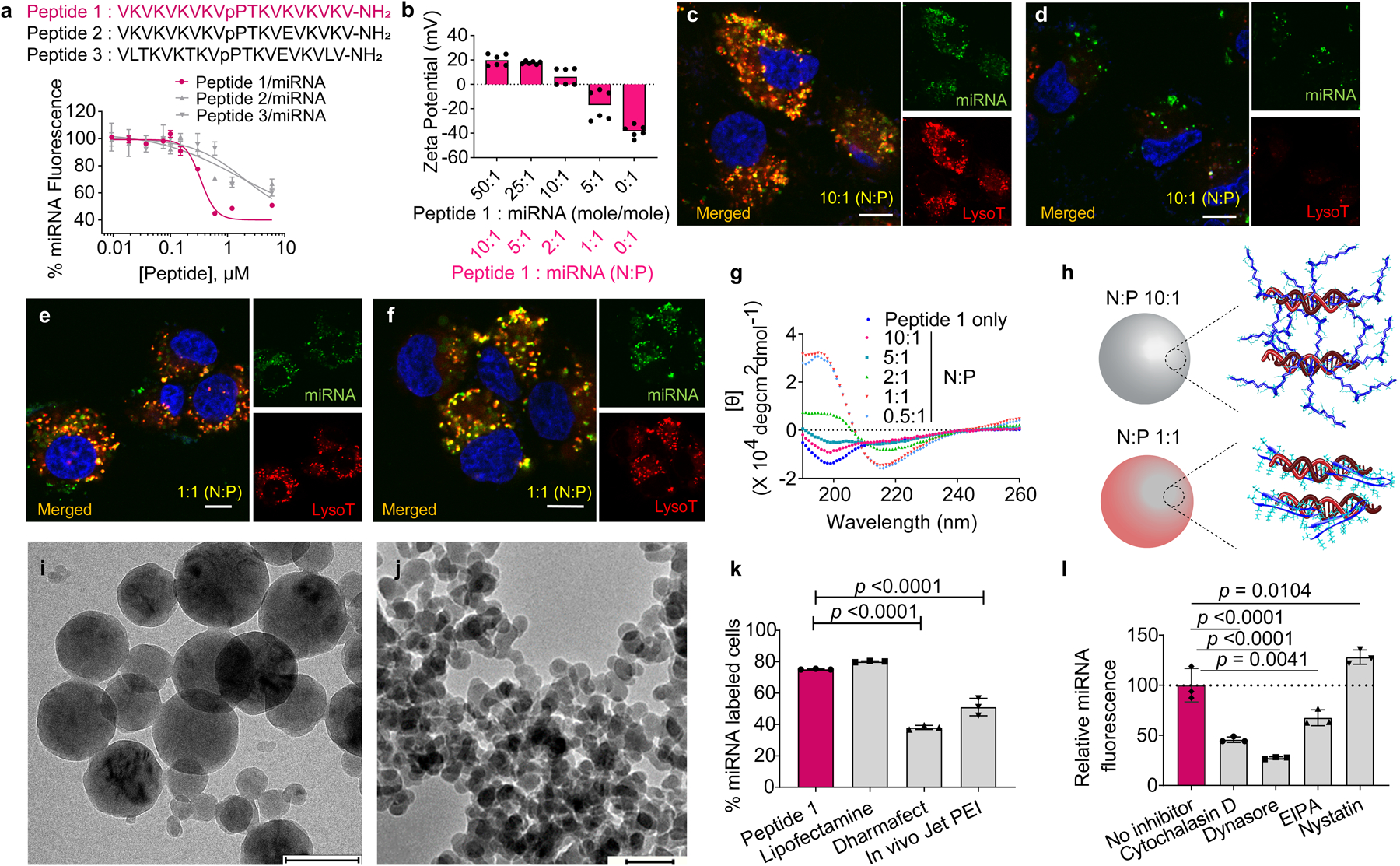

Apart from systemic delivery of miRNA24, 25, there is current interest in developing materials that can locally deliver miRNA26 for a wide variety of clinical applications such as myocardial infarction27, bone regeneration28, wound-healing29 and cancer30, 31. Seminal to the design of our SFH are miRNA nanoparticles that can be released from the implanted material, enter cells and deliver their payload. Herein, we report a new type of RNA nanoparticle based on intrinsically disordered peptide. Particle development began with a small family of differentially charged cationic amphiphilic peptides that were synthesized (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2) and studied for their ability to cooperatively bind chemically-modified double-stranded miRNA mimics to form particles, Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. S3. Peptides 1–3 with charge states of +9, +7 and +5 at neutral pH, respectively were initially designed in our lab to self-assemble into fibrillar hydrogels in saline buffer adopting a β-hairpin conformation in their assembled state32. However, in pure water the peptides are freely soluble, monomeric, and intrinsically disordered. Here, we take advantage of their disordered state to form complexes with oppositely charged RNA. Using FAM (6-carboxyfluorescein)-labeled scrambled miRNA as a model, Fig. 2a shows that the most highly charged Peptide 1 (+9) cooperatively binds to form complexes with an EC50 ~300 nM and was thus studied further. Typically, in order to selectively target distinct cell populations, nanoparticles are functionalized with ligands that bind to target cell-surface receptors33, 34. Although effective, this can add complicating steps to the synthesis and limit scaled production of a given nanoparticle35. In contrast, incorporating additional functionality to our particles is not necessary to achieve selectivity with respect to a desired biological outcome. Although both cancer and non-cancer cells can uptake the SFH nanoparticles, biological action is only potentiated in mesothelioma cells because of their dysregulated genetic profile. Only in the cancer cells are the levels of miRNA-215 very low, facilitating genetic instability that is permissive to cancer progression. Normal mesothelial cells express basal levels of miRNA-215 and as will be shown, receiving more has no appreciable cytotoxic affect19. Thus, meaningful selectivity is achieved via the inherent biology of pleural mesothelioma cancer. Although nanoparticle functionalization is not needed, the biophysical properties of our RNA nanoparticle could influence its uptake. The charge ratio (amine: phosphate, N:P) and corresponding molar ratio of Peptide 1 to miRNA can be varied to alter the charge state of the resulting particles from +20 to −17 mV, Fig. 2b. Variation of charge ratio also affect the hydrodynamic diameters of the resulting particles and their miRNA encapsulation efficiency, as measured by DLS and agarose gel retardation assays, Supplementary Fig. S4. Particles range in size from 50 – 200 nm (Supplementary Fig. S4a) and while 10:1 (N:P) particles offer a quantitative encapsulation of miRNA, ~ 50% encapsulation is observed when the charge ratio is reduced to 1:1, Supplementary Fig. S4b,c. The influence of particle physicochemical character on cell entry and trafficking in H2052 mesothelioma cells is shown in Figs. 2c–f. Panel (c) shows that positively charged particles (N:P 10:1, +20 mV) rapidly enter cells through endocytosis and traffic to acidic endosomes as evidenced by the colocalization of miRNA (green) and LysoTracker-red. After 4h, the miRNA escapes the endosome as indicated by the loss of colocalization (d). Since Lysotracker is a pH-sensitive dye, the weaker red fluorescence at 4 h indicates the concomitant spreading of the LysoTracker from the acidic endosomes to the neutral cytosol. This observation is similar to previous reports.36, 37 Similar results were obtained using orthogonal probes, Cy3-miRNA (red) and LysoTracker-blue, Supplementary Fig. S5. In separate studies where calcein and 10:1 (N:P) particles are co-incubated with cells, endocytosed calcein is released into the cytoplasm, supporting the assertion that the nanoparticles can facilitate endosomal escape38, Supplementary Fig. S6.

Fig. 2. Engineering, physical characterization and transfection efficacy of miRNA nanoparticles.

a, Sequences of candidate peptides for miRNA particle formulation and binding isotherms for each peptide using FAM-labeled scrambled miRNA. Data = mean ± SD, n = 3 independent samples. b, Zeta potentials of miRNA particles prepared from different mole ratios (and corresponding charge ratio, N:P values) in water at 25 °C. n = 6 measurements over 2 independent experiments. Confocal microscopy of H2052 mesothelioma cells treated for 0.5 h (c) and 4 h (d) with particles containing FAM-miRNA (green, 40 nM final concentration) complexed with Peptide 1 at N:P = 10:1. Corresponding images of cells treated for 0.5 h (e) and 4 h (f) with 1:1 (N:P) particles. Nuclei are stained blue and acidic endosomes are stained red. Scale bar 10 μm for each image. Panels c – f are representative of 3 independent experiments. g, Circular dichroism spectra of Peptide 1 alone and in complex with scrambled miRNA at various N:P ratios, recorded in water at 37 °C. [θ] denotes Mean Residue Ellipticity. Data is representative of 2 independent experiments. h, Models showing conformational state of Peptide 1 bound to miRNA in both 10:1 and 1:1 (N:P) particles. i, Cryo-electron micrographs of 10:1 (N:P) Peptide 1: scrambled miRNA particles. Scale bar 200 nm. j, Cryo-electron micrographs of 1:1 (N:P) Peptide 1: scrambled miRNA particles. Scale bar 100 nm. Uncropped micrograph (Figure S26a). Panels i & j are representative of 2 independent experiments. k, miRNA transfection efficiency of 10:1 (N:P) particles into H2052 cells after 1 h exposure compared to commercially available agents. Data = mean ± SD, n = 3 independent samples, representative of 2 independent experiments. Significant difference was assessed by Ordinary one-way ANOVA & Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. l, cellular transfection of 10:1 (N:P) particles into H2052 cells as a function of endocytic inhibitors. Median fluorescence intensities are normalized to miRNA internalization in the absence of inhibitor. Data = mean ± SD, n = 3 independent samples, representative of 2 independent experiments. Significant difference was assessed by Ordinary one-way ANOVA & Dunnett’s multiple comparison test.

In contrast, although negatively charged particles (N:P 1:1, −17 mV) are able to enter cells, they do not escape acidic endosomes, Figs. 2e,f. Surprisingly, we found that not only does particle charge/size influence cellular trafficking, but also the conformation of Peptide 1 bound to RNA within the particles. CD spectroscopy probes the conformation of Peptide 1 within particles of different charge ratios, Fig. 2g. The peptide adopts an intrinsically disordered state within the positively charged 10:1 (N:P) particle. In contrast, the same peptide adopts a folded β-hairpin structure within the negatively charged 1:1 (N:P) particle. Here, the smaller number of peptides are provided with adequate RNA surface area onto which they can bind and fold, Fig. 2h. In a control experiment, we found that 10:1 (N:P) positively charged particles formulated with a folded variant of Peptide 1 (cyclic-Peptide 1) partitioned to cell surfaces but were unable to internalize into cells, Supplementary Fig. S7. Thus, particle charge state/size, miRNA encapsulation efficiency and the peptide’s conformation are important for cell entry and trafficking. Particles display spherical morphologies by cryo EM, with the 10:1 (N:P) having an average diameter ~150 nm (range ~100–200 nm), Fig. 2i, Supplementary Fig. S8a–d and the 1:1 (N:P) particles showing an average diameter of 50 nm (range 40–60 nm), Fig. 2j. The 10:1 (N:P) particles are capable of transfecting H2052 cells as well as commercially available lipofectamine and better than Dharmafect and Jet PEI, as determined by flow cytometry, Fig. 2k, Supplementary Fig. S9a, b and by qPCR, Supplementary Fig.S9c,d. Our nanoparticles enter cells by endocytosis that is largely clathrin mediated, Fig. 2l, Supplementary Fig. S10.

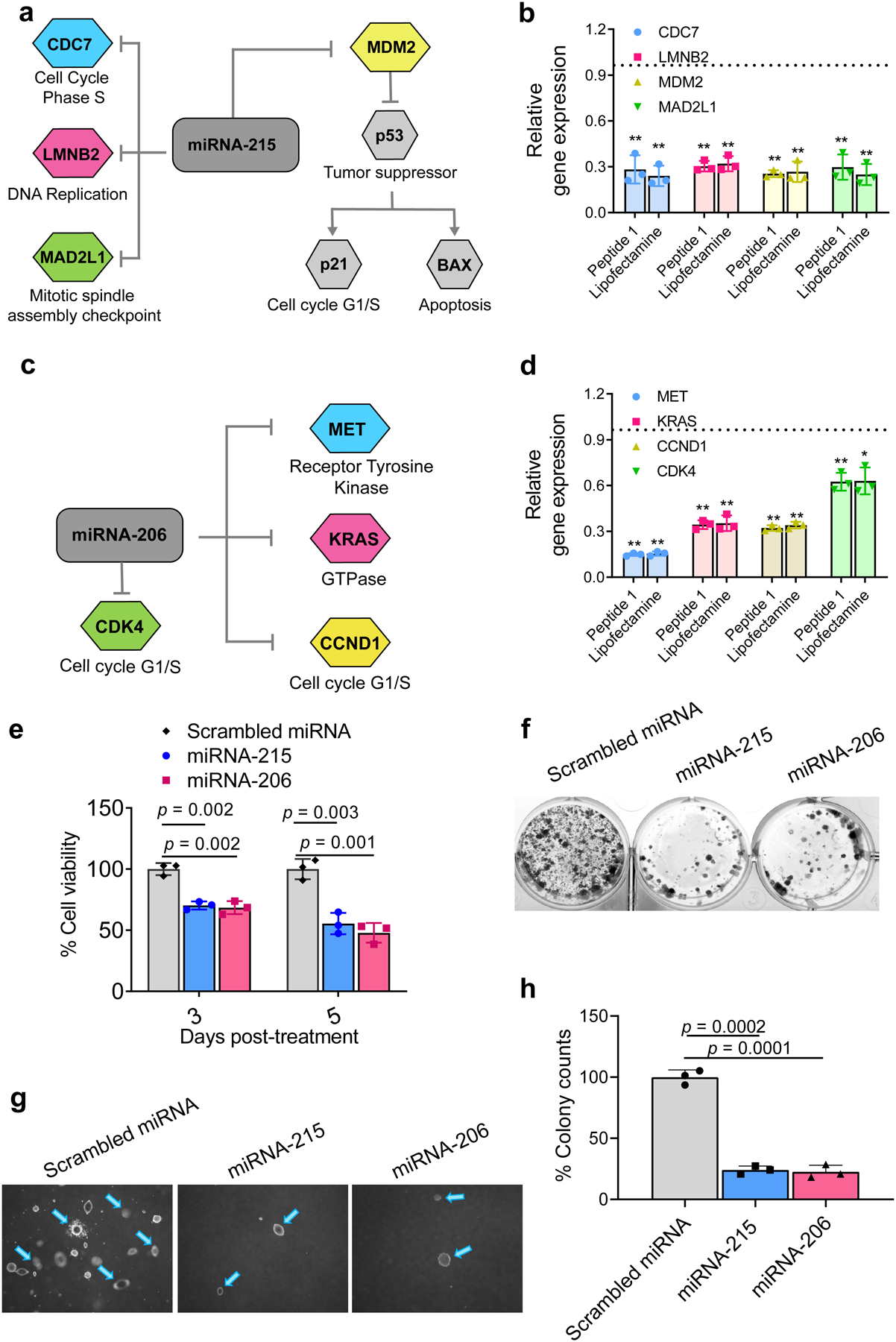

We recently reported that miRNA-215 silences MAD2L1, CDC7, and LMNB2, key genes involved in proliferation as well as MDM2, the master regulator of p53, Fig. 3a.19 Attenuation of these genes grossly affect the oncogenic signature of mesothelioma19. Nanoparticles (10:1, N:P) formulated with double-stranded miRNA-215 mimic are capable of entering cells and significantly silencing these key genes (Fig. 3b). Though the ability of the 10:1 nanoparticles to enter cells is not vastly different from the 1:1 nanoparticles (Supplementary Fig. S11a), the later shows almost no efficacy in silencing target genes, Supplementary Fig. S11c. This is most likely due to the inefficient escape of the 1:1 particles from the endosome, in contrast to the 10:1 nanoparticles, Fig 2c–f, Supplementary Fig. S11b. In fact, co-incubating cells with Bafilomycin A138, 39, an endosomal acidification inhibitor, significantly limits the 10:1 nanoparticles’ ability to silence genes exemplifying the importance of endosomal escape, Supplementary Fig. S12. We’ve shown in separate work that an additional set of genetic regulators of mesothelioma progression (MET, KRAS, CCND1 and CDK4) can be attenuated by successful delivery of miRNA-206, Fig. 3c20. 10:1 (N:P) nanoparticles were equally capable in attenuating the expression of these genes when formulated similarly with double-stranded miRNA-206 mimic, Fig. 3d. Silencing efficacy of the nanoparticles was comparable to that for Lipofectamine, Figs. 3b & 3d. Silencing of key genes results in a time-dependent decrease in cell viability, Fig. 3e. miRNA-215 and miRNA-206 nanoparticles are also capable of inhibiting 2D-colony formation (Fig. 3f) and anchorage-independent 3D-growth of mesothelioma cells, Figs. 3g,h. Control experiments show that nanoparticles formulated with scrambled miRNA mimic are non-cytotoxic in H2052 mesothelioma cells, Supplementary Fig. S13a,b. Importantly, nanoparticles delivering miRNA-215 or miRNA-206 mimics do not significantly alter the viability of NP4 cells, a non-cancerous mesothelial cell line derived from human pleural biopsy explants, Supplementary Fig. S13c.40

Fig. 3. Peptide 1/miRNA-215 and Peptide 1/miRNA-206 nanoparticles attenuate the oncogenic signature of mesothelioma in vitro.

a, miRNA-215 silences key genes important to mesothelioma oncogenesis. b, miRNA-215 nanoparticles decrease expression levels of target genes relative to scrambled miRNA particles in H2052 cells 48 h post-treatment compared to Lipofectamine under similar conditions. Data = mean ± SD, n = 3 independent experiments, **p <0.01, two-tailed student’s t test. c, miRNA-206-targetted genes. d, miRNA-206 nanoparticles decrease expression levels of target genes relative to scrambled miRNA particles in H2052 cells 48 h post-treatment compared to Lipofectamine under similar conditions. Data = mean ± SD, 3 independent experiments, **p <0.01, *p <0.05, Significant difference was assessed by two-tailed student’s t test. e, H2052 cell viability at day 3 and 5 post-treatment with the nanoparticles delivering miRNA-215 and miRNA-206. Data = mean ± SD, n = 3 independent experiments, Significant difference was assessed by two-tailed student’s t test. f, Clonogenicity of H2052 cells treated with the nanoparticles delivering miRNA-215 and miRNA-206, 2 weeks post-treatment. Representative image is shown for n = 3 independent samples. g, Anchorage-independent 3D growth of cells 6 weeks after treatment with the nanoparticles delivering miRNA-215 and miRNA-206. h, Quantification of 3D colony formation, Data = mean ± SD, n = 3 independent samples. Significant difference was assessed by two-tailed student’s t test.

Formulation and mechanical characterization of SFH.

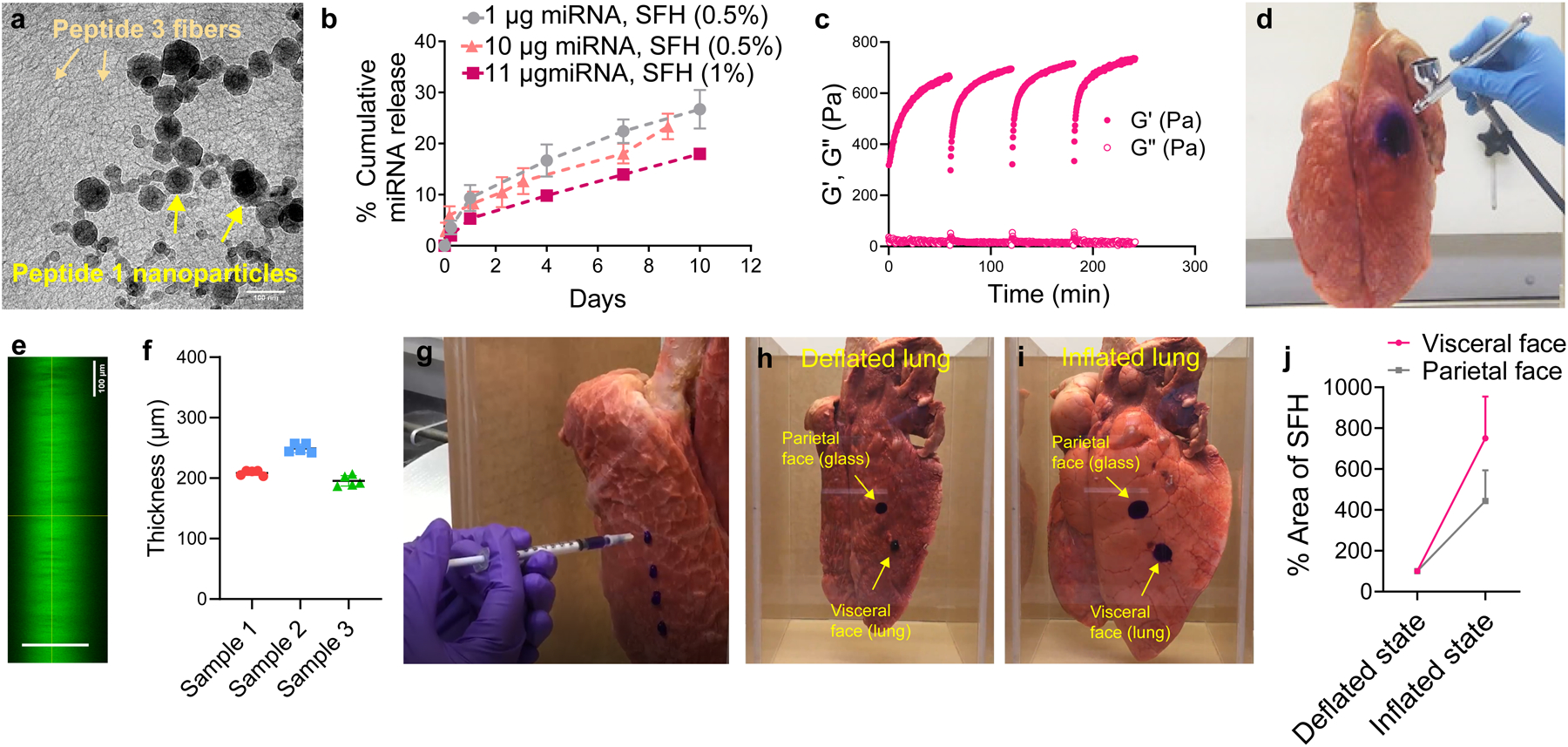

Surface-fill hydrogels are easily prepared by adding a saline buffered suspension of miRNA nanoparticles to an ice-chilled buffered solution (pH 7.4) of self-assembling Peptide 3 and warming the resulting mixture to 37°C. The increase in temperature facilitates hydrophobically-driven peptide self-association41 leading to the formation of a fibrillar gel that encapsulates the nanoparticles as shown by cryo-EM, Fig. 4a. 10:1 nanoparticles were stable in water, the medium for peptide 1/miRNA complexation, for up to 100 min which is within the time-span required to encapsulate the particles within the fiber network of SFH, Supplementary Fig. S14a. Once encapsulated, transmittance experiments indicate that the particles do not aggregate for at least one week, the last time point assessed, Supplementary Fig. S14b. Further, at least 20 μg of miRNA can be encapsulated within 100 μL volume of SFH without initiating any significant aggregation of the nanoparticles, Supplementary Fig. S14b. This is also corroborated from the cryo EM images of SFH collected at day 1 and day 7 post-preparation, Supplementary Fig. S14c & d.

Fig. 4. Formulation and physical characterization of SFH.

a, Cryo-TEM of 1 wt% SFH showing miRNA nanoparticles embedded within the fibrillar gel network formed by self-assembled Peptide 3. Fibers and nanoparticles are labeled. Scale bar 100 nm. Representative of 2 independent experiments. Uncropped micrograph (Figure S26b) b, miRNA particle release from 0.5 and 1 wt% SFH over time. Data = mean ± SD, n = 3 independent samples, representative of 3 independent experiments. c, Time-sweep shear thin-recovery oscillatory rheology of SFH. Storage and loss moduli (G’ and G”) were first monitored for 1 h, after which SFH underwent 3 consecutive shear-thin/recovery cycles. Data representative of 3 independent experiments. d, SFH is sprayed onto the surface of a porcine lung. The material is shear-thinned into microdroplets when sprayed and recovers on the surface of the lung. SFH is doped with Crystal Violet to aid in visualization. e, Confocal microscopic z-stack image of SFH (doped with calcein) sprayed onto a glass surface. f, Quantification of the thickness of sprayed SFH from panel e by measuring the distance (shown with green line) between the bottom of the image (region below the glass slide) and the top of the image (region above the gel). g, SFH is syringe-injected onto the surface of a porcine lung. Supplementary Video 1 shows that SFH adheres and expands with the lung tissue during lung inflation. Supplementary Video 2 shows syringe-based injection and tissue-site localization of SFH. h, SFH syringe-delivered to deflated lung and glass chamber surfaces modeling its application to the visceral and parietal surfaces of the pleural cavity after mesothelioma debulking. i, Spread-fill behavior of SFH during lung re-inflation and tissue contact with the parietal wall; also shown in Supplementary Video 3, 4 and 5. j, quantification of spread area for both the visceral and parietal surface-applied SFH as a function of lung status, Data = mean ± SD, n = 3 independent experiments.

We chose to encapsulate the miRNA nanoparticles into a positively charged fibrillar network. Repulsive forces between the positively charged miRNA nanoparticle and the like-charged gel network drive the release of intact particles as shown using scrambled miRNA particles as a model, Supplementary Fig. S14e. SFH can deliver its payload over an extended time period at a rate that is modestly dependent on the wt% of Peptide 3 used in the formulation, but independent of RNA concentration Fig 4b. SFH formulated with miRNA-215 particles release cargo that is biologically active demonstrating that the encapsulation procedure is passive, Supplementary Fig. S15a,b. The electropositive charge state of the fibrillar gel proved to be crucial for the delivery of intact particles. When positively charged miRNA particles were encapsulated into a negatively charged fibrillar gel, Peptide 1 within the particles disassociates and partitions to the negatively charged fibers. Consequently, free miRNA is quickly released, which is unable to enter cells, Supplementary Fig. S16. The mechanical rigidity (G’) of SFH can be tuned by simply adjusting the amount of Peptide 3 used for self-assembly, Supplementary Fig. S17. SFH displays shear-thin/recovery through multiple cycles of applied strain (Fig. 4c) indicating that it can be sprayed to tissues of complex surface anatomy as shown in Fig 4d and Supplementary Video 1 where a 1 wt% SFH is being delivered to the surface of porcine lung. Confocal microscopy shows that spraying 0.2 mL of SFH leads to the formation of 200–250 μm thick films, Fig. 4e,f. In addition, SFH is also amenable to syringe delivery to the surface of lung, Fig. 4g, Supplementary Video 2. The material is also able to adapt to its anatomical surroundings by flow-filling in response to strain. Clinically, we envision that after mesothelioma debulking surgery, as an example, SFH delivered to both the chest wall (parietal surface) and the deflated lung (visceral surface) defining the pleural cavity can shape-change during lung re-inflation to better fill complex tissue surface features and more effectively deliver the miRNA particles. This is modeled experimentally in Figs. 4h–j, Supplementary Video 3, 4 and 5, where SFH is applied to deflated porcine lung and the opposing face of a glass confinement chamber. Lung inflation expands the tissue against the chamber wall with concomitant spread-filling of the material.

In vivo efficacy of SFH.

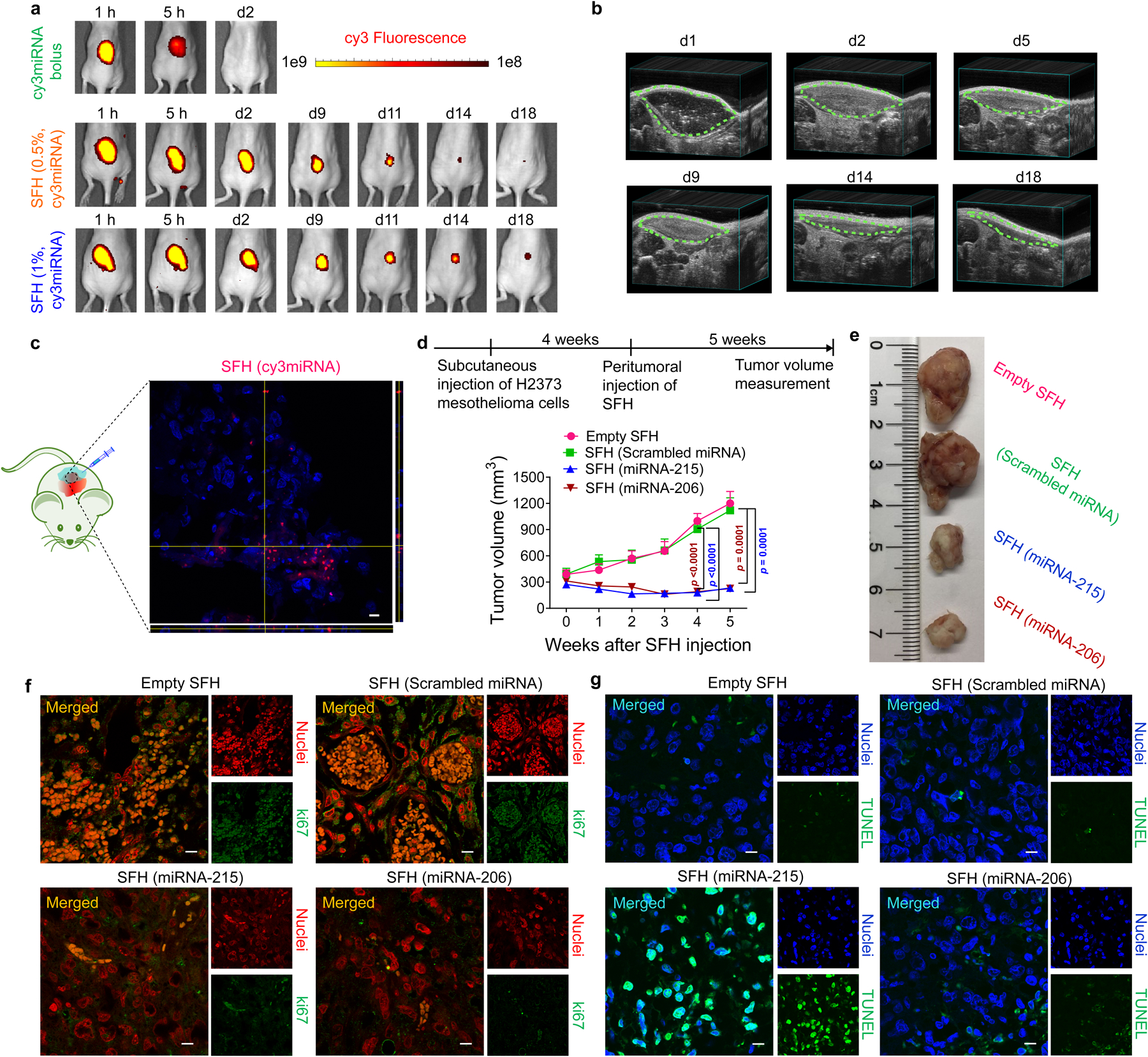

SFH is capable of time-dependent localized delivery of Cy3-labeled miRNA nanoparticles. Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. S18a show that a bolus of free miRNA is cleared within one day versus subcutaneously injected SFH, which mediates delivery over two weeks localized to the implant site. The duration of delivery is defined by both the passive diffusion of particles from the gel network and the active biodegradation of the implanted material. Ultrasound imaging shows that SFH is degraded over the same time course as miRNA depletion, and histology shows that the main route of degradation is phagocytosis, Figs 5b, Supplementary Fig. S18b,c,S23. Immunocompromised nu/nu mice receiving subcutaneous, intraperitoneal, or intrapleural SFH maintained bodyweight and there were no signs of toxicity as assessed by histopathology of vital organs, Supplementary Fig. S19. Safety and tolerability of SFH with encapsulated miRNA-215 and miRNA-206 were further confirmed by analyzing the weights of vital organs, complete blood count, blood chemistry and quantification of immune cell invasion in immunocompetent C57BL/6J mice, Supplementary Fig. S20–23. SFH can locally deliver Cy3-miRNA into cells when injected peritumorally into mice bearing H2373 mesothelioma xenografts with no observable delivery to other organs, Fig.5c, Supplementary Fig. S24a–d. The ability of SFH to deliver its cargo locally is further supported by the lack of miRNA detected in circulating plasma over a week post-subcutaneous administration, Supplementary Fig. S24e.

Fig. 5. In vivo delivery and anti-cancer effects of SFH.

a, Local release of Cy3-labeled miRNA nanoparticles from 0.5 and 1 wt% SFH in athymic nu/nu mice versus free miRNA. Data representative of 3 independent animals for SFH groups and 2 animals for miRNA bolus group. b, Biodegradation of 1 wt% SFH monitored by ultrasound. Data representative of 3 independent animals. c, Peritumorally injected SFH delivers miRNA locally to cells in a subcutaneous xenograft. Intracellular fluorescence is observed from H2373 mesothelioma tumor cross-sections from NSG mice at 24 h post injection. Corresponding z-stacks are also shown. Scale bar 10 μm. Data representative of 2 independent experiments. d, Subcutaneous xenograft H2373 tumor volume as a function of time and SFH composition. NSG mice (n = 5 for therapeutic miRNA treated groups, n = 4 for rest) received a single injection of the different SFHs. Data = mean ± SEM. Statistics at week 4 & 5 were derived from surviving mice; for week 4, n = 4 animals for empty SFH group and scrambled miRNA group, n = 5 for rest; for week 5, n = 3 for empty SFH & scrambled miRNA-treated groups, n = 4 for rest, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test. e, Images of tumors resected from treated mice on week 4 post-SFH injection. Immunohistochemical evaluation of tumor tissue resected from mice treated with various SFH compositions for (f) Ki67, a nuclear marker of proliferative capacity and (g) apoptosis using TUNEL staining. Tumors were collected at 4 weeks post-SFH treatment. Nuclei in panel f were stained with DAPI and pseudo-colored red in ImageJ to aid visualization. Nuclei in panel g are blue. Scale bar 10 μm in each image. Data for (f,g) representative of 2 independent experiments.

We chose 1 wt% SFH for all our in vivo efficacy studies since this delivered miRNA for a slightly longer duration than 0.5 wt% SFH, Fig. 5a. The therapeutic efficacy of SFH was assessed in four preclinical models of mesothelioma using miRNA-215 and miRNA-206 nanoparticles. In the first three models of increasing complexity, SFH was evaluated as a primary treatment to native, bulk tumor and thus represents challenging clinical scenarios. In the fourth model, SFH was applied as an adjuvant after tumor resection to study its ability to thwart tumor recurrence. The first model was a subcutaneous xenograft model using large (~300 mm3) H2373 tumors. Figs. 5d,e shows that a single injection of SFH peritumorally to mice effectively reduces tumor growth when either miRNA-215 or -206 is delivered. Tumor tissue isolated from mice receiving SFH (miRNA-215) contained elevated levels of miRNA-215 over 2 weeks post-material injection with concomitant silencing of target genes (MDM2, CDC7, MAD2L1, LMNB2), Supplementary Fig. S25. Further, cells within resected tumor tissue showed low expression of Ki-67, a nuclear proliferation marker, when either miRNA-215 or-206 was delivered as compared to animals receiving SFH with scrambled or no miRNA, Fig 5f. TUNEL staining showed that miRNA-215-treated tissue contained a significant population of apoptotic cells, consistent with its predominant mechanism of activating p5319 whereas the effect of miRNA-206 treatment was less pronounced in this assay because its predominant anti-tumor mechanism is via cell cycle arrest, Fig. 5g. Taken together, these results show that SFH can effectively deliver miRNA to tumor in vivo.

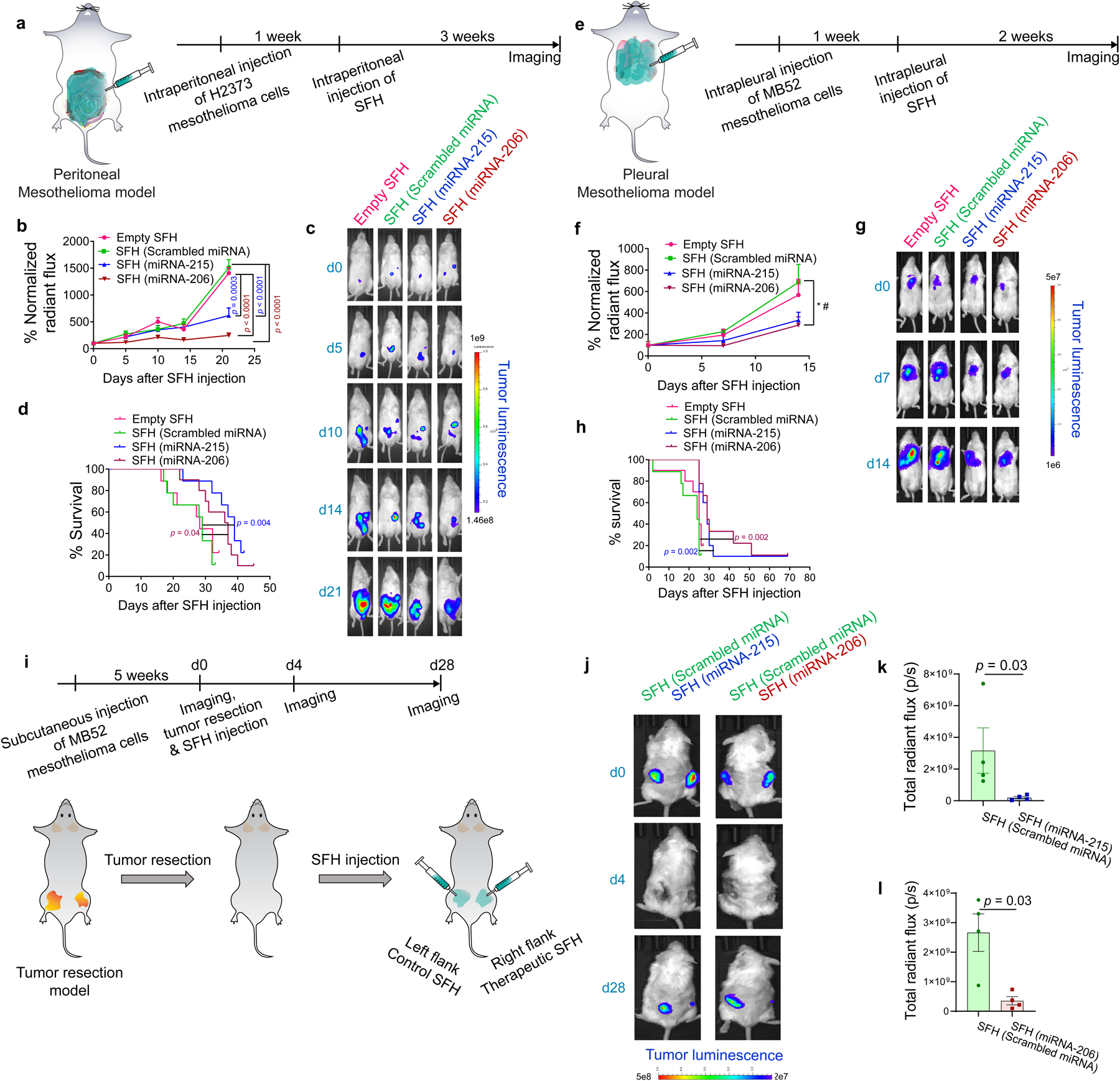

SFH efficacy was next studied using a disseminated orthotopic peritoneal model where cancer is spread throughout the gut and involving organs having complex surface topology. Here, luciferase-expressing H2373 cells are introduced into the peritoneum and allowed to disseminate over 1 week, Fig.6a. This model approximates the anatomical presentation of human peritoneal mesothelioma. A single application of SFH delivering either miRNA-215 or -206 significantly retards tumor progression and leads to enhanced survival, Figs. 6b–d.

Fig. 6. Mesothelioma xenograft models demonstrate therapeutic potential.

a, Intraperitoneal mesothelioma model. Luciferase-expressing H2373 cells introduced to the peritoneal cavity of NSG mice (n = 10 animals for miRNA-206 group; n = 9 for rest) established tumor after 1 week. Tumor progression was monitored for 3 weeks after a single injection of SFH. b, Tumor progression as a function of SFH composition. ROI radiant flux at each time was normalized to day 0 for each treatment group. Statistics at day 21 derived from surviving mice; n = 7 for empty SFH and scrambled miRNA-treated group, n = 8 for miRNA-215-treated group and n = 9 for rest; One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test. c,d, Tumor luminescence and survival curves of mice treated with SFHs, Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. e, Intrapleural mesothelioma model. Luciferase-expressing MB52 cells introduced in the pleural cavity of NSG mice (n = 10 animals for empty SFH & miRNA-215 group and n = 9 for rest) established tumor after 1 week. Tumor progression was monitored for 2 weeks after a single injection of SFH. f, Tumor progression as a function of SFH composition. ROI radiant flux at each time point was normalized to day 0 for each treatment group. Statistics at day 14 derived from surviving mice, n = 9 for empty SFH & miRNA-206 groups, n = 10 for miRNA-215 group and n = 8 for rest; * p = 0.035, One-way ANOVA, # p = 0.045, Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test between scrambled miRNA and miRNA-206 groups. g,h Tumor luminescence and survival curves of mice treated with SFHs, Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. i, Mesothelioma xenograft resection model. Luciferase-expressing MB52 cells were subcutaneously injected into the left and right flanks of NSG mice. After 5 weeks (tumor volume ~200 mm3), tumors were resected and SFH of indicated compositions were syringe-administered to the resection sites. j, Tumor luminescence of mice treated with SFHs. k & l, Total radiant flux at tumor ROI for different treatment groups at day 28 post-administration of SFH, n = 4 animals, two-tailed Mann Whitney test. Data = mean ± SEM for b,f,k,l.

The third animal model was the most clinically aggressive where MB52 cells were introduced into the pleural cavity of mice to approximate human pleural mesothelioma. After bulk tumor development within 1 week, SFH was administered intrapleurally without lung deflation, Figs. 6e–h. A single injection of SFH delivering either miRNA-215 or-206 nanoparticles reduced cancer progression and improved survival where 21% of mice lived well past the median overall survival timepoint. Most strikingly, the degree of efficacy associated with a single SFH treatment was statistically significant in two orthotopic models representing the worst clinical scenario of aggressive, intact bulk tumor. Lastly, we assessed the performance of SFH treatment when applied as an adjuvant to surgical resection. Bilateral flank xenografts of luciferase-expressing MB52 cells were established in mice and then tumors were completely resected leaving no visible tumor behind in the surgical site to approximate microscopic residual disease. During wound closure, one flank was treated with SFH delivering miRNA-215 or -206, while the other flank was treated with SFH delivering scrambled miRNA serving as the control. After one month, those sites receiving adjuvant SFH-miRNA (miRNA-215 or-206) therapy registered only faint tumor recurrence by bioluminescence, whereas SFH-scrambled-treated sites showed aggressive regrowth of bulky tumor, Figs. 6i–l. Thus, there is great promise of clinically effective results if this system can be developed for human use to treat microscopic cancer foci.

Conclusions

Cancers that occur on complex anatomic surfaces represent a unique and clinically challenging scenario. Treating primary tumor with systemically administered drugs is often not significantly beneficial. Thus, surgical resection represents an important aspect of multimodality treatment even though achieving clean tissue margins is technically impractical and residual microscopic tumor foci ultimately cause disease recurrence. SFH was engineered to be used either as a primary treatment or as an adjuvant therapeutic complementing surgical resection, especially in procedures leaving large areas of topologically complex tissue. In either clinical modality, SFH is engineered to effectively coat complex surfaces via spray or syringe delivery, respond to changes in tissue morphology via spread-filling, and deliver miRNA nanoparticles capable of entering cancer cells and releasing their gene-silencing payload. Herein, SFH efficacy was demonstrated for mesothelioma, a cancer that intrinsically resists traditional therapeutics and characterized by dismal prognosis. In addition to new materials development, our work provides proof-of-concept that mesothelioma can be affected by the local delivery of tumor-specific miRNA agents. This is a significant cancer related finding that lays the foundation to change the treatment paradigm for mesothelioma and, in due time, other surface cancers such as ovarian carcinoma42 and gliomas43.

Methods

Preparation of nanoparticles and SFH

To prepare nanoparticles for 100 μL of SFH (0.5 wt%) containing a total of 1 μg of miRNA, stocks of Peptide 1 (10 mg/mL.) and miRNA (1 mg/mL, Supplementary Table S1) were first prepared in RNase free water. Then, 1.28 μL of Peptide 1 stock and 1 μL of miRNA stock were separately diluted with RNase free water to final volumes of 12.5 μL. The two solutions were combined resulting in a suspension (25 μL) which was agitated (70rpm) at 37 °C for 30 min to form the particles. SFH is prepared by mixing the particle suspension (25 μL) with ice-chilled 2X HBS (25 μL, 50 mM HEPES 300 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) and adding the resulting suspension to an ice-chilled solution of hydrogelating peptide 3 (50 μL, 1 wt%, 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.4). The resulting suspension was mixed and incubated at 37 °C overnight affording 100 μL of 0.5 wt%, SFH (25 mM HEPES, 75 mM NaCl) containing nanoparticles (molar ratio, 50:1 [peptide1:miRNA]; N:P, 10:1) and a total of 1 μg miRNA. Depending on the experiment, different formulations of SFH were prepared by adjusting the concentrations of miRNA, Peptide 1, and Peptide 3.

Physical characterization of nanoparticles

Nanoparticle zeta potentials were measured using a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments Ltd., software: Malvern Panalytical-7.13) at 25 °C using a constant 1.56 μg miRNA for particle preparation. Nanoparticles were diluted with water to 1 mL before measurement. For the 1:1 (N:P) particle the zeta potential was calculated using the equation below, solving for zeta potentialparticle, to account for uncomplexed RNA in the sample solution: Zeta Potentialobserved = complexed fraction of miRNA (zeta potentialparticle) + uncomplexed fraction of miRNA (zeta potentialfree miRNA).

RNA encapsulation efficiencies were determined using an electrophoretic mobility shift assay. Aqueous stock solutions of Peptide 1 and scrambled miRNA were mixed to afford nanoparticles having N:P ratios of 10:1, 5:1, 2:1 and 1:1 keeping the total amount of miRNA constant (1.56 μg) for each particle type. Resulting suspensions were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C with agitation, then loaded onto a 2% (w/v) agarose gel prepared with Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer (Thermo Fisher) containing ethidium bromide at 0.3 μg/mL. A similar concentration of uncomplexed miRNA was also loaded as the control and molecular weight standard. Bands resulting from encapsulated and unencapsulated fractions of miRNA for each particle type were resolved in Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer at 80 V for 1 h and visualized using a Gel Documentation System (Bio-Rad). For each nanoparticle type, the uncomplexed miRNA band was quantified for intensity using ImageJ and normalized against the intensity of the control uncomplexed miRNA band of known concentration to calculate miRNA encapsulation efficiency using the equation: % Encapsulation efficiency = 100 − [(Observed intensity of uncomplexed miRNA band from nanoparticle / Intensity of uncomplexed control miRNA of known concentration) × 100].

Hydrodynamic diameters of nanoparticles (N:P ratios = 10:1, 5:1, 2:1 and 1:1, each type containing a total of 7.8 μg miRNA) were determined using a Zetasizer Nano ZS90 (Malvern Instruments Ltd., software: Malvern Panalytical-7.13) at 25 °C. For the stability analysis, DLS readings were acquired in water over 100 min post particle preparation. Number-weighted size distribution was derived from correlograms using the analysis algorithm within the Malvern software and number mean size was plotted as a function of time.

Cryo-electron micrographs of 10:1 and 1:1 (N:P) nanoparticles containing scrambled miRNA were collected on an FEI Tecnai T12 microscope. Samples were prepared using an FEI Vitrobot and ~ 3 μL of the particle suspension applied to a c-flat holey carbon grid (hole size 2 μm).

Intracellular nanoparticle localization

H2052 cells (5×104) were seeded on 35 mm glass-bottom petri dishes 4 days before transfection. 10:1 (N:P) nanoparticles were prepared from FAM or cy3-labeled scrambled miRNA and diluted with optiMEM (Thermo Fisher) to obtain a final miRNA concentration of 40 nM which was added to cells. To determine the nanoparticle intracellular distribution (Fig 2c–f), cells were treated with lysotracker (100 nM final concentration) for 30 min before imaging. Lysotracker Red and Lysotracker Blue were used for cells treated with FAM-labeled miRNA and cy3-labeled miRNA, respectively. Cells were incubated with 2 μg/mL Hoechst 33342 for 30 min immediately before imaging whenever nuclei staining was required. Imaging was performed on a Zeiss LSM710 confocal microscope as detailed in the Supplementary Information.

In vitro Transfection Efficiency

H2052 cells (1.2×105) were seeded on 6 well plates 24 h before particle treatment. 10:1 N:P nanoparticles comprised of FAM-labeled miRNA were diluted with optiMEM to maintain a final miRNA concentration of 40 nM and then incubated with cells for 1 h. Cells were then washed with cold PBS, trypsinized (15 min) and collected by centrifugation. Pellets were washed and resuspended in 500 μL PBS before analyzing by flow cytometery (flow cytometer: BD LSRIITM, data acquisition: FACSDiva 8.0.1; data analysis: FlowJo version 10). Complexes of commercial transfection agents (Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Thermo), In vivo-jet PEI (Polyplus-transfection® SA) and DharmaFECT™ (Dharmacon)) and an equivalent amount of miRNA were prepared according to the manufacturers’ instructions and analyzed similarly.

Physical characterization of SFH

Cryo-TEM of 1 wt% SFH containing 10:1 N:P nanoparticles having a total of 3 μg of scrambled miRNA was performed on a FEI Tecnai T20 microscope (200 kV) with a magnification of 50,000x that resulted in a pixel size of 4.41 Å at the specimen plane. Images were acquired with an Eagle 2kx2k CCD camera (FEI) using a defocus of 3–5 μm. SFH (3 μL) was applied to Quantifoil R2/2 grids and after 20 seconds incubation, excess sample was blotted using filter paper leaving a thin layer of gel. To prevent sample drying, 3 μL buffer solution was applied and the grid was immediately plunge-frozen using an FEI Vitrobot. Freezing conditions: 95% humidity, 0 s wait time, 6 s blot time and 0 blot force.

Rheological characterization of 0.5 and 1.0 wt% SFH containing 10:1 N:P nanoparticles having a total of 1 μg of scrambled miRNA was conducted on a TA Instruments AR-G2 rheometer (data acquisition: TRIOS v5.1.1.46572 & Rheology Advantage v5.8.2; data analysis: Trios 4.4.1.41651) at 37 °C using an 8 mm stainless steel parallel geometry. SFH samples (100 μL) were prepared in flexiPERM® chambers (Greiner Bio-One) and incubated at 37 °C overnight. SFH samples were then transferred to the center of the rheometer plate (pre-equilibrated at 37 °C) and the upper geometry was lowered to a gap height of 0.5 mm. A dynamic time sweep experiment was performed for 60 minutes at a constant angular frequency of 6 rad/s and 0.2 % strain. After which, samples were subjected to 1000% shear for 30 seconds (at frequency 6 rad/s) followed by a 60-minute dynamic time sweep (6 rad/sec, 0.2% strain). Samples were exposed to multiple cycles of low strain/high strain/low strain sweeps to evaluate their shear-thin recovery properties.

Porcine Lung - Delivery of SFH as spray

1.0 wt% SFH containing 10:1 N:P nanoparticles having a total of 1 μg of scrambled miRNA was doped (1% v/v) with a dye solution of crystal violet (50 mg/mL in DMSO) two days before the experiment. Then, 0.5 mL of the SFH sample was transferred to the fluid cup of a gravity-feed airbrush equipped with a 0.3 mm nozzle (Airbrush MAS KIT-VC16-B22 Portable Mini Airbrush Air Compressor Kit). The sample was then allowed to equilibrate for two days at 37 °C. A pre-fixed swine lung (BioQuest™ Inflatable Lungs Kit-Fisher Scientific) connected to an inflation assembly apparatus provided to inflate the lung on demand. Compressed air delivered through the airbrush shear-thins the gel and allows it to be sprayed onto the front surface of the lung where SFH recovers, coating the lung surface. After SFH delivery, the lung was expanded and contracted to demonstrate the shape-change properties of the material.

Porcine Lung - Spread/fill behavior of SFH

Dye-loaded SFH was prepared as described above, transferred to a syringe equipped with a 27G needle and allowed to incubate at 37 °C overnight. A pre-fixed swine lung connected to an inflation assembly apparatus was placed within a custom-built plexi-glass chamber with a detachable front plate. For each experiment, 0.2 mL of the SFH sample was syringe-injected onto the front surface of the lung (visceral face) and on the inner side of the front plate that faces the lung (parietal face). The lung was then allowed to inflate gradually by slowly increasing the flow rate of air which resulted in lung expansion until it contacted the opposing plexi-glass plate, which resulted in SFH volume spreading. Once the lung reached the inflation limit, the air flow was gradually reduced until complete deflation was achieved. The entire process was repeated (n =3) and video-recorded. Screenshots were collected before inflation and after maximum inflation. The areas of visceral and parietal applied gels were measured before and after lung expansion assuming a circular region of interest. A = 3.14 × (radius of the circle)2.

In vivo studies

Athymic nu/nu mice (female, 6–8 weeks old), NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) mice (male or female, 6–12 weeks old) and C57BL/6J mice (female, 5–7 weeks old) were used for this study. All animals were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment at ambient temperature (24 ± 2 °c), air humidity 40 – 70% and 12 h dark/12 h light cycle. All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee, NIH. Frederick National Laboratory is accredited by AAALAC International and follows the Public Health Service Policy for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animal care was provided in accordance with the procedures outlined in the “Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (National Research Council; 2011; National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.).

Mesothelioma xenograft model: subcutaneous

Biodistribution

2×106 H2373 cells were subcutaneously administered in NSG mice (6–8-week-old). Mice were continuously monitored for tumor growth. At each time point, mice were shaved, and a slide caliper was used to measure the length and width of the tumors. Tumor volume was calculated as 0.5×length×width2. To determine the tissue-distribution of delivered miRNA, 200 μL of 1 wt% SFH with a total of 20 μg of cy3 labeled scrambled miRNA was injected peritumorally when tumors reached an average volume of ~ 100 mm3. Mice similarly injected with empty SFH were taken as control to correct for tissue autofluorescence. Whole-body images were acquired 24 h post-injection to monitor cy3 fluorescence. Animals were then sacrificed; tumors and vital organs were collected and imaged.

To evaluate intratumoral localization of injected cy3 miRNA, frozen tumors were used to generate 5 μm thick sections which were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS. 1–2 drops of Prolong Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Life Technologies) was added to stain the nuclei and the sections were imaged using an LSM710 confocal microscope (data collection: Zen 2012 SP5, Zeiss and data processing: Fiji-ImageJ version 1.52p).

To determine the concentration of miRNA in the circulation, blood was sampled at 2 h, day 1 and day 7 post-administration from mice receiving a single subcutaneous injection of 0.2 mL SFH containing 10:1 (N:P) particles with cy3 miRNA. Another group of mice were similarly administered with empty SFH and blood samples were collected simultaneously. Plasma was isolated and fluorescence was measured using a plate reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT) set at 532 nm and 570 nm as excitation and emission wavelengths, respectively.

Tumor growth inhibition

For tumor growth inhibition studies, NSG mice bearing H2373 mesothelioma tumors were randomly divided into four treatment groups (n = 4–5 in each). When tumors reached an average volume of ~ 300 mm3, mice were peritumorally administered with 200 μL of empty SFH or SFH loaded with nanoparticles containing 20 μg miRNA. 1 wt% Peptide 3 was used to formulate all SFH samples. Only a single injection was performed. One animal from each group was sacrificed on week 4, tumors excised and imaged, while the remaining animals were monitored for another week until the average tumor volume for the control groups reached 1000 mm3. Tumors were fixed with formalin and sectioned for immunohistochemistry. Mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation when any of the tumors began to ulcerate, mice became moribund or if tumor growth hindered eating, urination, or defecation.

Immunohistochemistry

To determine extent of apoptosis induced by different formulations, a TUNEL assay kit (Promega) was used. Briefly, paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated using an ethanol gradient. Sections were incubated with the TUNEL enzyme mixture for 1 h following the manufacturer’s instructions and nuclei were stained using Prolong Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI. The sections were imaged using an LSM710 confocal microscope (data collection: Zen 2012 SP5, Zeiss; data processing: Fiji-ImageJ version 1.52p).

Expression of proliferation marker ki67 was monitored using immunohistochemistry. Rehydrated tumor sections were immersed in sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and heated at 95 °C for 20 min to retrieve antigen. Sections were blocked using goat serum (10% in Tris Buffered Saline), incubated with rat anti-mouse Ki67 (Clone SolA15) antibody (eBiosciences, catalog # 14-5698-82, 1:100 in blocking buffer) for 1 h followed by a 30-min incubation with Alexa-Fluor 488 anti-rat secondary antibody (Invitrogen catalog # A-11006, 1:500 in Tris Buffered Saline). Nuclei were stained using Prolong Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI. The sections were imaged using an LSM710 confocal microscope (data collection: Zen 2012 SP5, Zeiss) and the nuclei were pseudo-colored to red during image processing using Fiji-ImageJ version 1.52p.

qPCR for gene expression analysis in vivo

In a separate experiment, mice bearing subcutaneous H2373 tumors with an average volume of ~ 100 mm3 were peritumorally administered with 200 μL of 1 wt% SFH containing scrambled miRNA and miRNA-215, respectively (with 10 μg miRNA loaded per 100 μL of the SFH). Three animals from each group was sacrificed on week 1 and the remaining three animals on week 2. Tumors were excised, and total RNA was isolated using a standard protocol. Gene expression was analyzed using qPCR as described before. For miRNA analysis, reverse transcription was performed using the TaqMan advanced miRNA cDNA synthesis kit. U6 snRNA was used as an endogenous control to determine the expression of miR-215. β-actin was used as a reference gene to analyze the gene expressions of miR-215 target genes LMNB2, CDC7, MDM2 and MAD2L1.

Mesothelioma xenograft models: orthotopic

For peritoneal mesothelioma tumor growth inhibition studies, 1×106 H2373 cells stably expressing luciferase reporter vector pGL4.51[luc2/CMV/Neo] (Promega) were intraperitoneally administered in NSG mice (6–8-week-old). One week after tumor cell inoculation, mice were randomly divided into four treatment groups (n = 9–10 in each). 400 μL of empty SFH as well as SFH containing different nanoparticle formulations (with 10 μg miRNA loaded per 100 μL of the SFH) were administered intraperitoneally. 1 wt% Peptide 3 was used to formulate all SFH samples. Tumor growth in the peritoneal cavity was monitored weekly for three weeks by measuring luminescence in In-Vivo Imaging System (IVIS Lumina Series III, PerkinElmer). Living Image software (version 4.3.1) was used for image acquisition and analysis. A total 200 μL (15 mg/mL) of D-luciferin potassium salt solution (Regis Technologies) was administered into the intraperitoneal cavity of mice immediately before imaging and mice were continuously observed to track survival.

For pleural mesothelioma tumor growth inhibition studies 1×106 MB52 (Epithelioid Mesothelioma cell line-52) cells stably expressing luciferase gene were injected into the pleural space (thoracic cavity) of NSG mice (6–8- week-old) using a 30G needle. One week after tumor cell inoculation, mice were randomly divided into four treatment groups (n = 9–10 in each). 100 μL of empty SFH as well as SFH containing different miRNAs (with 10 μg miRNA in each) were administered intrapleurally. 1 wt% Peptide 3 was used to formulate all SFH samples. Tumor growth in the pleural cavity was monitored weekly for two weeks by measuring luminescence as described previously. Mice were continuously monitored to track survival.

Mesothelioma xenograft model: surgical resection

3×106 MB52-luciferase cells were injected on left and right flank of NSG mice (6–8- week-old). Mice were continuously monitored for tumor growth. Tumor volumes reached an average of 200 mm3 after 5 weeks. Tumor burden was also confirmed by luminescence signal, measured according to the protocol described above. At this point, tumors were resected using sterile instruments by maintaining mice in anaesthetized conditions using isoflurane. Briefly, mice were first anaesthetized in an induction chamber using isoflurane (3%), and then during surgery anaesthesia was maintained (1% isoflurane) via a nose cone. Although there was no visible tumor left behind, we postulated that MPM cell line-derived xenografts would likely recur, similar to their in vivo counterparts which are biologically aggressive and defy macroscopic resection. Mice were randomly divided into two groups (n = 4). For the first group of mice, 200 μL each of SFH (scrambled miRNA) and SFH (miRNA-215) was administered into the surgical bed of the left flank and the surgical bed of the contralateral flank, respectively. The second group of mice were administered with 0.2 mL each of (scrambled miRNA) and SFH (miRNA-206) into the left and right resection bed, respectively. For each group, 10 μg miRNA was loaded per 100 μL of the SFH. Tumor growth in the resection locations was monitored for 4 weeks by measuring luminescence as described above.

Detailed methods for the remaining experiments described in the paper can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis to compare data between two groups was performed using two-tailed Student’s t-tests, with either Microsoft Excel or GraphPad Prism 7.0 or 8.0 version. One-way ANOVA was used to compare among multiple groups along with Tukey’s or Dunnett’s post-hoc test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Mice were randomly divided into groups.

Extended Data

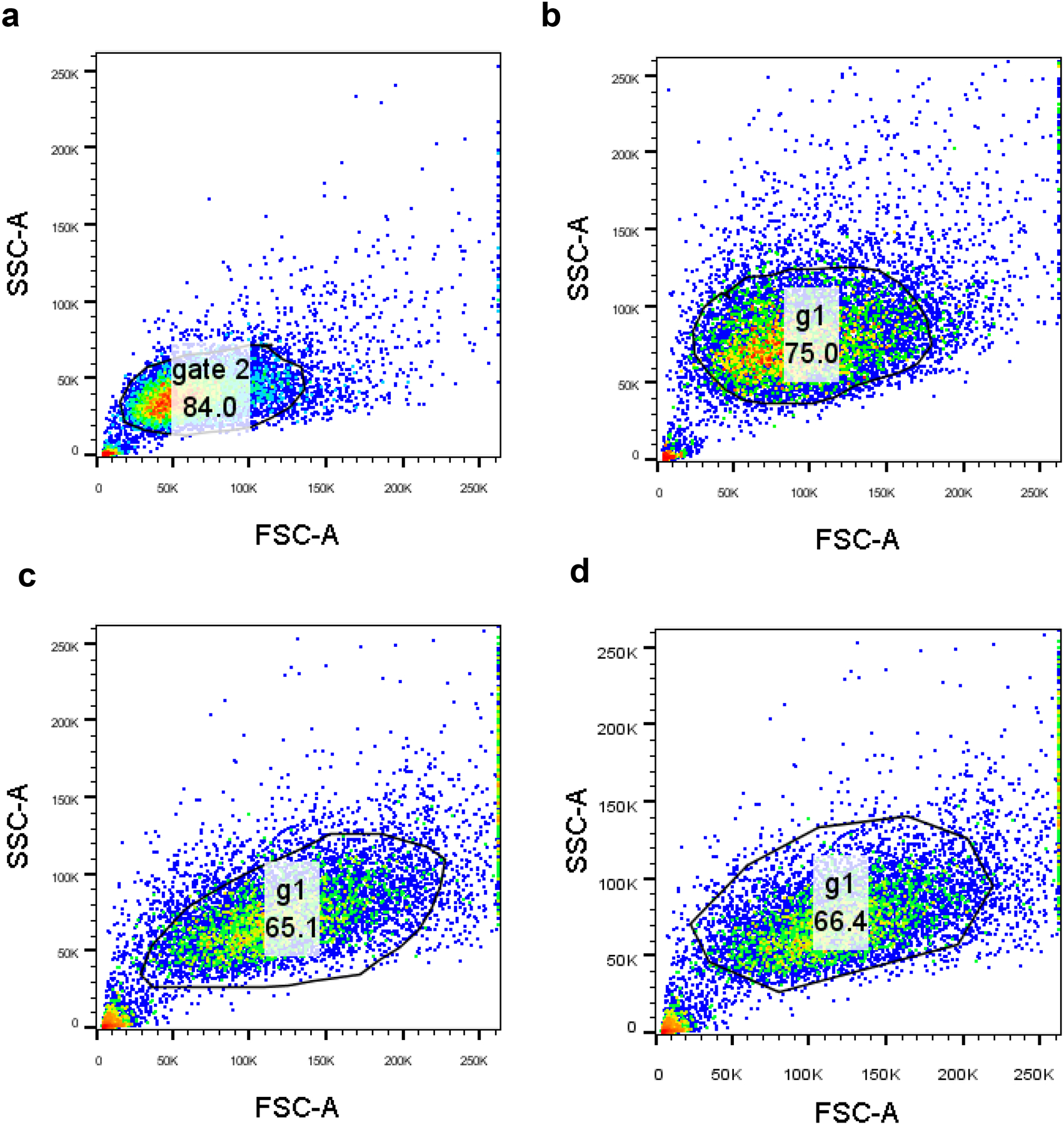

Extended Data Fig. 1. Gating strategies used for the analysis of flow cytometry data.

Panel a, gating strategy used for the experiments shown in Figure 2l and Supplementary Figure S10a,c; b, gating strategy used for the experiments shown in Supplementary Figure S11a; c, gating strategy used for the experiments shown in Figure 2k and Supplementary Figure S9a; d, gating strategy used for the experiments shown in Supplementary Figure S9b. In each case, cell only samples were gated first using FSC and SSC parameters to exclude cell debris and large aggregates. The same gating strategy was applied across all samples in the set. This live population was then used for analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study was provided through the intramural program of the National Cancer Institute, specifically ZIABC011313 (JPS) and ZIABC011657 (CDH). The authors acknowledge Dr. Gary Pauly from the Chemical Biology Laboratory, NCI Frederick (NCI-CBL) for help with videography. We thank Dr. Tania Lizeth López-Silva for help in figure preparation and Ms. Patricia Beard from the NCI-CBL for administrative help. Dr. Simone Difilippantonio from the Laboratory Animal Sciences Program at the NCI Frederick is acknowledged for help with animal experiments.

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement

JPS, PM, CDH and AS have filed a patent covering this work. All the other authors do not have competing interests.

Data Availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Hassan R et al. Major cancer regressions in mesothelioma after treatment with an anti-mesothelin immunotoxin and immune suppression. Sci Transl Med 5, 208ra147 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher JH & Child CG 3rd Myasthenia gravis developing acutely after partial removal of a thymoma. N Engl J Med 252, 891–893 (1955). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motohara T et al. An evolving story of the metastatic voyage of ovarian cancer cells: cellular and molecular orchestration of the adipose-rich metastatic microenvironment. Oncogene 38, 2885–2898 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zajac O et al. Tumour spheres with inverted polarity drive the formation of peritoneal metastases in patients with hypermethylated colorectal carcinomas. Nat Cell Biol 20, 296–306 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bueno R, Opitz I & Taskforce IM Surgery in Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol 13, 1638–1654 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolfe GI et al. Randomized trial of thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. New England Journal of Medicine 375, 511–522 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winner KRK et al. Spatial modeling of drug delivery routes for treatment of disseminated ovarian cancer. Cancer research 76, 1320–1334 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacquet P & P.H., S. Peritoneal-plasma barrier. In: Sugarbaker PH (eds) Peritoneal Carcinomatosis: Principles of Management., Vol. 82. (Springer, Boston, MA, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenblum D, Joshi N, Tao W, Karp JM & Peer D Progress and challenges towards targeted delivery of cancer therapeutics. Nat Commun 9, 1410 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu J et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature 435, 834–838 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rupaimoole R & Slack FJ MicroRNA therapeutics: towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 16, 203–222 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ling H, Fabbri M & Calin GA MicroRNAs and other non-coding RNAs as targets for anticancer drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 12, 847–865 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zalcman G et al. Bevacizumab for newly diagnosed pleural mesothelioma in the Mesothelioma Avastin Cisplatin Pemetrexed Study (MAPS): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 387, 1405–1414 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldini EH et al. Updated patterns of failure after multimodality therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 149, 1374–1381 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bertoglio P, Aprile V, Ambrogi MC, Mussi A & Lucchi M The role of intracavitary therapies in the treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Dis 10, S293–S297 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lucchi M et al. A phase II study of intrapleural immuno-chemotherapy, pleurectomy/decortication, radiotherapy, systemic chemotherapy and long-term sub-cutaneous IL-2 in stage II-III malignant pleural mesothelioma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 31, 529–533; discussion 533–524 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu R et al. Nanoparticle tumor localization, disruption of autophagosomal trafficking, and prolonged drug delivery improve survival in peritoneal mesothelioma. Biomaterials 102, 175–186 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taioli E et al. Second Primary Lung Cancers Demonstrate Better Survival with Surgery than Radiation. Semin Thorac Cardiov 28, 195–200 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh A et al. MicroRNA-215–5p Treatment Suppresses Mesothelioma Progression via the MDM2-p53-Signaling Axis. Mol Ther (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh A, Pruett N, Pahwa R, Mahajan AP, Schrump DS, Hoang CD microRNA-206 Suppresses Mesothelioma Progression via the Ras Signaling Axis. Molecular Therapy: Nucleic Acid 10.1016/j.omtn.2021.04.001 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Zandwijk N et al. Safety and activity of microRNA-loaded minicells in patients with recurrent malignant pleural mesothelioma: a first-in-man, phase 1, open-label, dose-escalation study. Lancet Oncol 18, 1386–1396 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bueno R et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis of malignant pleural mesothelioma identifies recurrent mutations, gene fusions and splicing alterations. Nat Genet 48, 407–416 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu Y et al. miR-1 induces growth arrest and apoptosis in malignant mesothelioma. Chest 144, 1632–1643 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui X et al. Enhanced Chemotherapeutic Efficacy of Paclitaxel Nanoparticles Co-delivered with MicroRNA-7 by Inhibiting Paclitaxel-Induced EGFR/ERK pathway Activation for Ovarian Cancer Therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 10, 7821–7831 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kasinski AL et al. A combinatorial microRNA therapeutics approach to suppressing non-small cell lung cancer. Oncogene 34, 3547–3555 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y, Gao DY & Huang L In vivo delivery of miRNAs for cancer therapy: challenges and strategies. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 81, 128–141 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang LL et al. Local and sustained miRNA delivery from an injectable hydrogel promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation and functional regeneration after ischemic injury. Nat Biomed Eng 1, 983–992 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X, Li Y, Chen YE, Chen J & Ma PX Cell-free 3D scaffold with two-stage delivery of miRNA-26a to regenerate critical-sized bone defects. Nat Commun 7, 10376 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saleh B et al. Local Immunomodulation Using an Adhesive Hydrogel Loaded with miRNA-Laden Nanoparticles Promotes Wound Healing. Small, e1902232 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conde J, Oliva N, Atilano M, Song HS & Artzi N Self-assembled RNA-triple-helix hydrogel scaffold for microRNA modulation in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Mater 15, 353–363 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gilam A et al. Local microRNA delivery targets Palladin and prevents metastatic breast cancer. Nat Commun 7, 12868 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagy-Smith K, Moore E, Schneider J & Tycko R Molecular structure of monomorphic peptide fibrils within a kinetically trapped hydrogel network. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, 9816–9821 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conniot J et al. Immunization with mannosylated nanovaccines and inhibition of the immune-suppressing microenvironment sensitizes melanoma to immune checkpoint modulators. Nat Nanotechnol 14, 891–901 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen G et al. A biodegradable nanocapsule delivers a Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complex for in vivo genome editing. Nat Nanotechnol 14, 974–980 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng Z, Al Zaki A, Hui JZ, Muzykantov VR & Tsourkas A Multifunctional nanoparticles: cost versus benefit of adding targeting and imaging capabilities. Science 338, 903–910 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ren K et al. A DNA dual lock-and-key strategy for cell-subtype-specific siRNA delivery. Nat Commun 7, 13580 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen W, Deng W & Goldys EM Light-Triggerable Liposomes for Enhanced Endolysosomal Escape and Gene Silencing in PC12 Cells. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 7, 366–377 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen J et al. Metal-Phenolic Coatings as a Platform to Trigger Endosomal Escape of Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 13, 11653–11664 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gillespie EJ et al. Selective inhibitor of endosomal trafficking pathways exploited by multiple toxins and viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, E4904–4912 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pruett N, Singh A, Shankar A, Schrump DS & Hoang CD Normal mesothelial cell lines newly derived from human pleural biopsy explants. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 319, L652–L660 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagy-Smith K et al. Molecular, local, and network-level basis for the enhanced stiffness of hydrogel networks formed from coassembled racemic peptides: predictions from Pauling and Corey. ACS central science 3, 586–597 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun B et al. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy of ovarian cancer by hydrogel depot of paclitaxel nanocrystals. J Control Release 235, 91–98 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shankar GM et al. Genotype-targeted local therapy of glioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115, E8388–E8394 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.