Abstract

Background/Objectives.

Disclosure of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) risk information to cognitively unimpaired older adults may become more common if preclinical AD is shown to be identifiable and amenable to treatment. Little, however, is known about how families will react to this information.

Design and Setting.

Semi-structured telephonic interviews.

Participants.

70 study partners (mean age = 68 (±11); 50% female; 70% spouses/significant others; 18% children, siblings; 12% friends) of cognitively unimpaired adults who learned a personalized AD dementia risk estimate and an amyloid-β PET scan result through their participation in preclinical AD research.

Measurement.

Interviewees were asked about their desire for information regarding their family member’s AD dementia risk, baseline expectations of risk, understanding of amyloid-β PET scan results, and the impact of AD dementia risk information on emotions, health behaviors and future plans, as well as on perceptions of their family member’s or friend’s memory.

Results.

Interviewees generally understood the AD dementia risk information (83%) and considered it valuable (75%). Risk information perceived as favorable elicited feelings of happiness and relief; unfavorable information elicited disappointment, as well as increased awareness of the participants’ memory and monitoring for incipient changes in cognition. While noting that AD dementia risk information was not medically actionable at this time due to the lack of disease-modifying therapies, some interviewees described changes to their family members’ and their own health behaviors and future plans.

Conclusion.

Guidelines for the disclosure of AD dementia risk estimates and biomarker results to cognitively unimpaired adults should account for the needs and interests of individuals and their family members, who may step into a pre-caregiver role.

Keywords: amyloid-β, dementia, patient education, preclinical Alzheimer’s disease, care partners, PET scan

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is now conceptualized as a continuum that begins with a “preclinical” stage in which individuals have abnormal AD biomarkers but are not cognitively impaired.1 If preclinical AD is validated and found amenable to interventions that safely and effectively delay or prevent the onset of cognitive impairment, testing for AD biomarkers and disclosure of those results will likely become part of clinical practice.2,3 This will have widespread implications, as an estimated 46.7 million Americans have preclinical AD.4,5

Receiving a preclinical AD diagnosis will arguably transform what it means to be a person living with AD: many individuals will become “patients-in-waiting,” “hover[ing] for extended periods of time…between sickness and health.”6 Studies of the experiences of cognitively unimpaired persons who learn they have AD biomarkers indicate that this is particularly sensitive health information weighted with implications for identity, privacy, and self-determination. Learning dementia risk information precipitates changes in health behaviors and future plans and raises concerns around stigma and discrimination.7–14

This suggests the need to understand the preclinical AD experience of families as well, because family members share in AD dementia risk—whether directly due to shared risk factors or indirectly due to their likelihood of becoming caregivers. Moreover, family members may be asked to monitor the patient-in-waiting for changes in cognition and function or to engage in planning for the future.15 Some may even experience stigma.16,17 One way to study family members’ experiences and inform the future of clinical practice is to take advantage of preclinical AD studies that recruit “dyads” comprised of a research participant and a “study partner.”18,19 Study partners serve as knowledgeable informants—providing investigators with information about the participant’s cognition and function—but also learn about the participant’s risk of dementia caused by AD.

Here, we report results from interviews with study partners who participated in Risk Evaluation and Education of Alzheimer’s Disease: The Study of Communicating Amyloid Neuroimaging (REVEAL-SCAN; NCT02959489).

Methods

Interviewees were study partners in REVEAL-SCAN, a multi-site randomized controlled trial examining the psychological and behavioral impact of disclosing “elevated” and “not elevated” amyloid-β neuroimaging results to cognitively unimpaired adults aged 65–80 years with at least one first-degree relative with AD. Eligibility criteria mirrored other preclinical AD studies and, by extension, a patient population likely to be screened to determine the appropriateness of disease-modifying therapies. REVEAL-SCAN participants had to enroll with a study partner. The study partner was an individual identified by the research participant who could join the participant for at least one study visit to complete the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Scale, a validated informant interview assessing the participant’s cognition and functioning.20

All REVEAL-SCAN participants received a personalized estimate of their risk of developing AD dementia by age 85 based on age, race, sex, and family history. Genetic testing results and amyloid-β PET scan results were not included in this personalized risk estimate. REVEAL-SCAN participants underwent amyloid-β PET scans and were randomized to receive scan results either at their next study visit or at a study visit 6 months later. Personalized risk estimates and amyloid-β PET scan results (“elevated” or “not elevated”) were disclosed following standardized processes.21 Study partners’ presence was not required for disclosure.

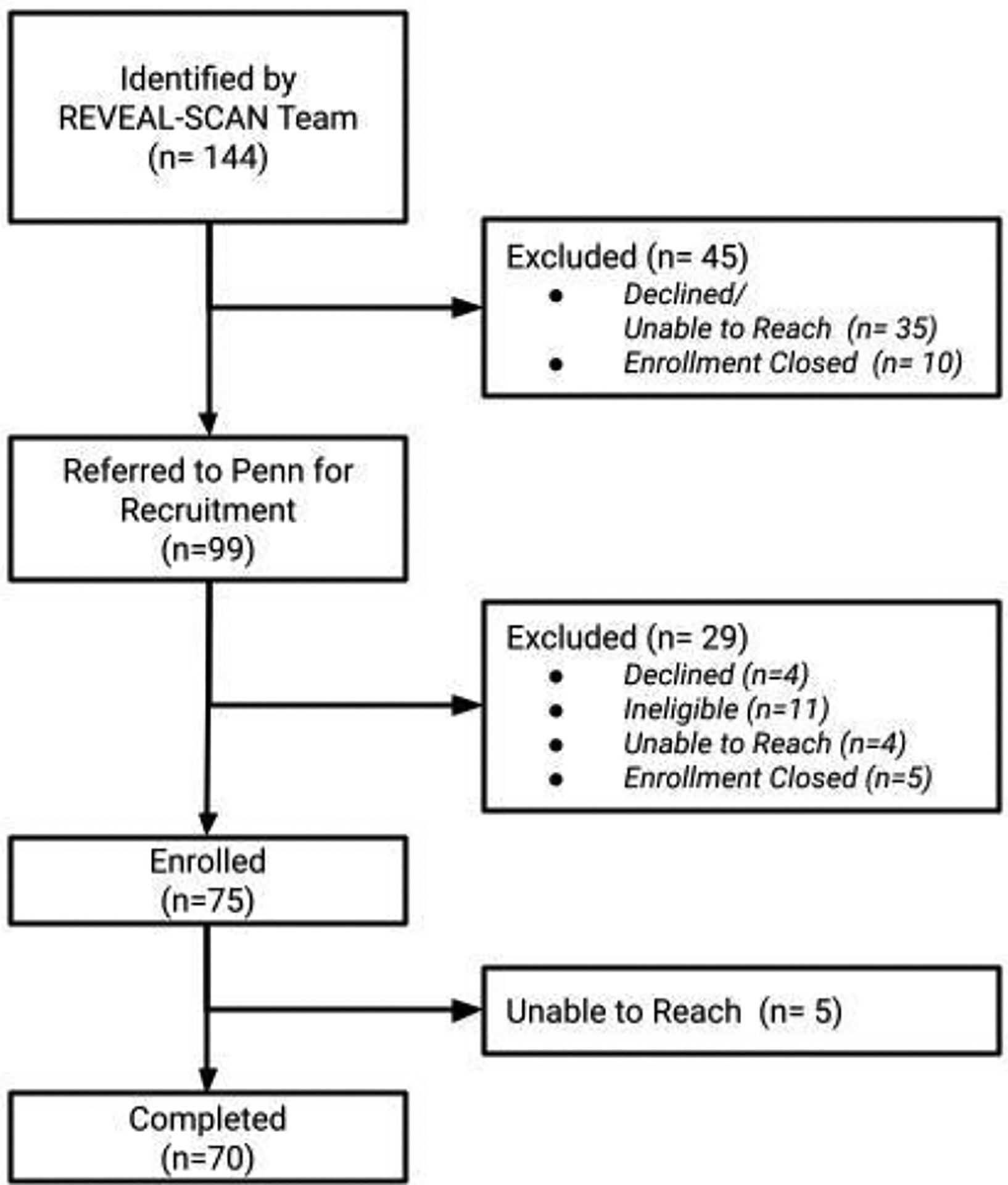

Study partners were purposively recruited for this interview study based on the REVEAL-SCAN participants’ amyloid-β PET scan results, participant-study partner relationship types, and study partner self-reported gender. Figure 1 details the recruitment flow.

Figure 1.

Recruitment flow.

A semi-structured interview guide was developed following a review of the literature. The interview guide examined: the study partner’s desire for information about the research participant’s AD dementia risk, baseline expectations, understanding of amyloid-β PET scan results, and impact of AD dementia risk information.

Telephonic interviews were conducted between July 2019 and July 2020 by one interviewer (MA) and took approximately 45 minutes. Audio recordings were professionally transcribed. NVivo qualitative analysis software (QSR International) was used to manage coding. Three authors (EL, MA, KH) reviewed a subset of transcripts to identify themes, which were formalized in a codebook. Some codes were descriptive and grounded in the data, while others were more interpretive, based on useful concepts from the literature. A subset of transcripts was double coded by team members until inter-coder reliability was achieved; differences were rectified through discussion, and the codebook was revised to account for themes not adequately captured and to adjust codes lacking clarity. Having developed a refined codebook and agreement on its application, MA coded the remaining transcripts.

The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Results

Demographics of the 70 interviewees are included in Table 1. Nearly three-quarters (70%) were spouses or significant others; the remainder were adult children, siblings, or friends. Twenty-seven had learned their partner’s “elevated” amyloid-β PET scan result, and 43 had learned a “not elevated” result. The average time between amyloid-β PET scan result disclosure and study interview was 1.5 years (minimum 1.8 months, maximum 33 months).

Table 1:

Demographic Characteristics of Interviewees (N=70)

| Characteristic | Not Elevated (n=43) |

Elevated (n=27) |

Total (n=70) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 67.9 ± 10.9 | 68.2 ± 11.5 a | 68.0 ± 11.0 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 22 (51%) | 13 (48%) | 35 (50%) |

| Female | 21 (49%) | 14 (52%) | 35 (50%) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 32 (74%) | 22 (81%) | 54 (77%) |

| Black | 11 (26%) | 4 (15%) | 15 (21%) |

| American Indian/Native Alaskan | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (1%) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 43 (100%) | 27 (100%) | 70 (100%) |

| Participant REVEAL-SCAN Arm, n (%) | |||

| Disclosure | 25 (58%) | 12 (44%) | 37 (53%) |

| Delayed Disclosure | 18 (42%) | 15 (56%) | 33 (47%) |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| Grade School | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) |

| High School | 2 (5%) | 1 (4%) | 3 (4%) |

| Some College | 5 (12%) | 3 (11%) | 8 (11%) |

| Associate Degree | 2 (5%) | 3 (11%) | 5 (7%) |

| 4 Year College Degree | 10 (23%) | 9 (33%) | 19 (27%) |

| Post Graduate Education | 23 (53%) | 11 (41%) | 34 (49%) |

| Family history of Alzheimer’s disease, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 25 (58%) | 10 (37%) | 35 (50%) |

| No | 18 (42%) | 17 (63%) | 35 (50%) |

| Relationship to Participant, n (%) | |||

| Spouse | 28 (65%) | 16 (59%) | 44 (63%) |

| Significant Other | 3 (7%) | 2 (7%) | 5 (7%) |

| Relative: Child | 5 (12%) | 4 (15%) | 9 (13%) |

| Relative: Sibling | 3 (7%) | 1 (4%) | 4 (6%) |

| Close Friend | 4 (9%) | 4 (15%) | 8 (12%) |

| Annual Household Income, n (%) | |||

| <$10,000 | 1 (2%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (3%) |

| $10,000 – $29,999 | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) |

| $30,000 – $49,999 | 4 (9%) | 9 (33%) | 13 (19%) |

| $50,000 – $69,999 | 6 (14%) | 5 (19%) | 11 (16%) |

| $70,000 – $89,999 | 9 (21%) | 2 (7%) | 11 (16%) |

| ≥ $100,000 | 20 (47%) | 9 (33%) | 29 (41%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (5%) | 1 (4%) | 3 (4%) |

| Living with Participant, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 33 (77%) | 18 (67%) | 51 (73%) |

| No | 10 (23%) | 9 (33%) | 19 (27%) |

age missing for n=1 study partner

Desire for information

Most interviewees (75%) indicated their participation in REVEAL-SCAN was motivated in part by a desire to know more about their family member’s or friend’s AD dementia risk. Some focused on the value of any information. For example, one individual expressed a desire to know his significant other’s “predisposition to [dementia], [because] if she did then we would make plans accordingly. … [I]t was just so logical that I actually felt we would be kind of stupid not to [learn] it.” More often, interviewees expressed a desire for “good stuff.” They anticipated receiving favorable information would be “a reassurance,” offer “some inner peace, some feeling of more security,” or “allay some of the fears.” Conversely, several expressed concerns about receiving information indicative of higher risk. For instance, one woman explained that prior to her husband’s enrollment in REVEAL-SCAN she had worried about “if he did test positive, what his reaction would be and mine as well…what it would mean for us going forward.”

Consistent with the expressed desire for information, all but six interviewees—evenly split between “elevated” and “not elevated”—knew their family member’s or friend’s amyloid-β PET scan result. Only a third, however, reported being present for disclosure. Those present wanted to offer “support.”

Baseline expectations for amyloid-β PET scan results

Among interviewees who learned a “not elevated” amyloid-β PET scan result, half said they had no expectations “one way or the other” at baseline. A third indicated the result was consistent with their baseline expectations, which often reflected a sense that their family member’s or friend’s “memory is quite excellent” or “sharp as a tack.”

Among those who learned an “elevated” result, a third reported having no expectations at baseline. Half said they had expected the “elevated” result, typically due to a “family history of Alzheimer’s” or “a steady decline in [her] being able to grasp words, memory, stuff like that.” One interviewee clarified, “[W]hat I was hoping and what I was expecting [were] two different things.”

About 15% of all interviewees reported being “kind of surprised” that the actual amyloid-β PET scan result diverged from their baseline expectations. Like others’ expectations, theirs were “based on family history” and perceptions of memory and thinking.

Understanding of AD dementia risk

Of the 43 interviewees who learned a “not elevated” amyloid-β PET scan result, most understood it to mean that their family member’s or friend’s AD dementia risk was average or decreased. Two mistakenly believed the “not elevated” result signified increased risk. Of the 27 interviewees who learned an “elevated” amyloid-β PET scan result, most explained it indicated an increased but uncertain risk of AD dementia. The following is a typical finding: “[T]here seems to be some relationship [between amyloid-β and AD dementia, but] it’s not 100% correlation.” Three reported the result was ambiguous. For example, “[T]hey [scientists] don’t even know positively, but they think that amyloids are an indication of Alzheimer’s.” Three misunderstood the “elevated” result: one indicated that the risk of AD dementia was “average” and two described it as decreased. Across all interviewees, misunderstandings were more common among non-spousal study partners who were not present for disclosure.

As noted above, the amyloid-β PET scan result was not figured into the personalized risk estimate but offered as a separate piece of information. Overall, interviewees distinguished the two pieces of information—though there were differences in how they understood them to relate to one another. For example, a wife explained that because her husband’s personalized risk estimate did not incorporate his “elevated” PET scan result, “[H]e has a higher risk than the [risk estimate] mathematics showed.” A husband whose wife ultimately received a “not elevated” PET scan result recounted “feeling pretty good about the fact that the [risk] estimate was she’s at low risk for getting Alzheimer’s. So I really wasn’t concerned about the amyloid test at that point.” In several cases, interviewees seemingly conflated the two pieces of information. For instance, one husband whose wife received an “elevated” amyloid-β PET scan result explained the meaning of that result in terms of the personalized risk estimate, saying, “there’s a possibility that she will develop Alzheimer’s. There’s also a possibility that she won’t since she was only 35%.”

Reactions to AD dementia risk

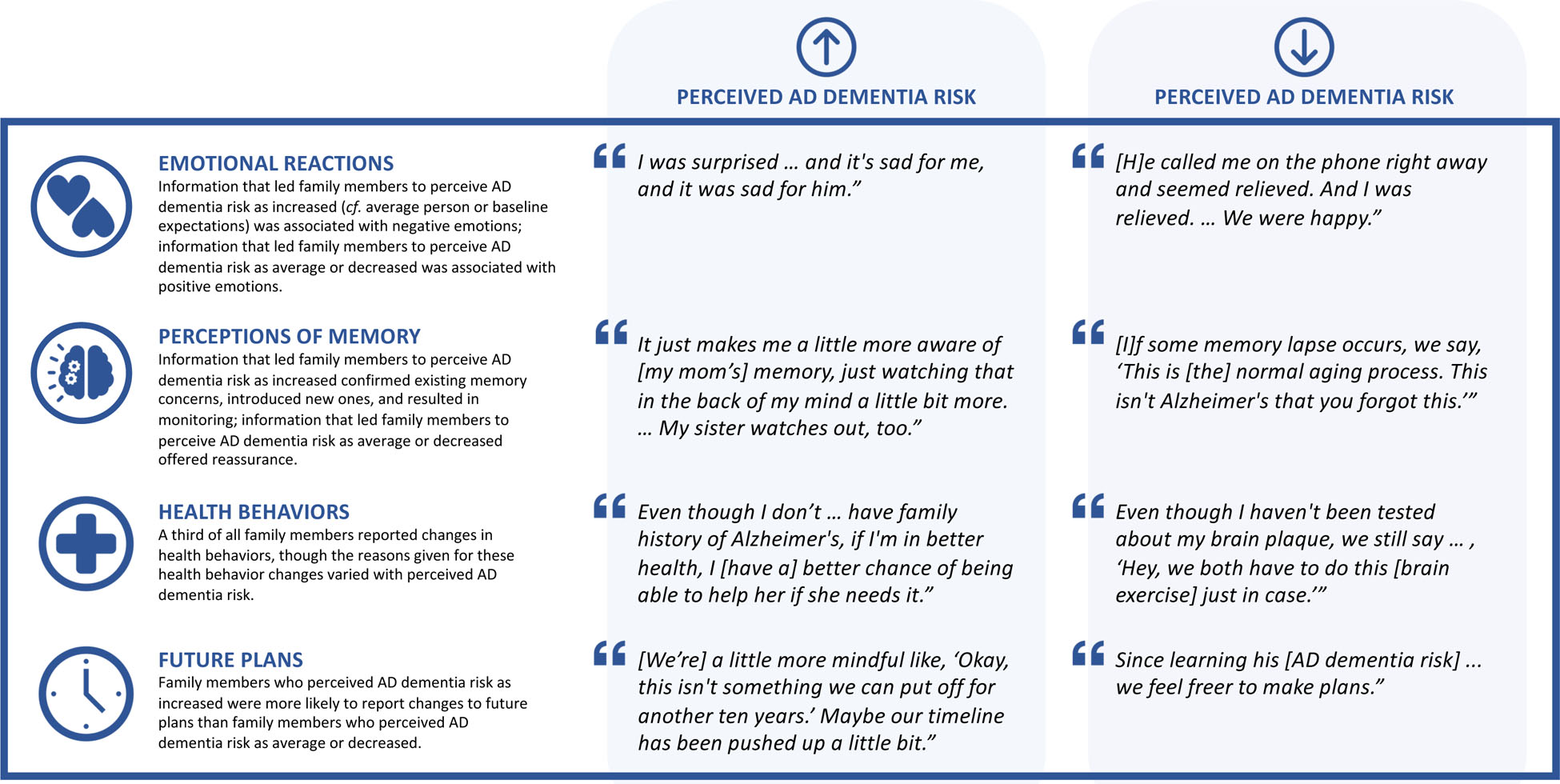

Interviewees who felt their friend or family member’s AD dementia risk was average relative to the population or decreased relative to their baseline expectations almost universally described themselves as relieved, happy (even to the point of being “ecstatic”), or both (Figure 2). A husband described how “in the back of [your] mind, you know, you think…maybe [my wife’s risk is] going to be 50%, 60%, 40%? So when it came to 28% I guess that was a little relief on my part.” One son explained how, prior to REVEAL-SCAN, he would test his mother’s cognition by saying things like “‘That’s a beautiful car. What color is that?’” He went on to note that the favorable information “helped me a lot.”

Figure 2.

Representative quotes from family members who learned a cognitively unimpaired older adult’s amyloid-β PET scan result and a personalized estimate of risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia by age 85 based on age, race, sex, and family history.

In select instances, interviewees’ positive feelings also reflected a new understanding of their own or others’ AD dementia risk. For example, one individual was “encouraged” by his brother’s AD dementia risk because it indicated his own risk might be low: “I realize I’m not him…but I don’t really have to dwell on Alzheimer’s.” A woman described how the risk information had given her mother’s “siblings some kind of hope as well.”

In contrast, many interviewees who felt their family member’s or friend’s risk of AD dementia was increased experienced negative emotions. Nearly a quarter were saddened. A wife stated, “I was sad. And it’s sad for me, and it was sad for him.” A significant other explained, “I felt, number one, … disappointed because it’s not great news.” One in 5 interviewees described feeling “a little more concerned” or “20% more worried” than before about their friend or family member developing AD dementia. A daughter added, “I think we all worry that if this is hereditary, then I could just as well be behind her doing the same [getting AD].” Other interviewees expressed resignation, asserting “[w]ell, it’s life” or “this is just part of living.”

Effect on perceptions of memory

Most interviewees (61%) denied that learning their family member’s or friend’s AD dementia risk had any effect on their perceptions of that individual’s memory; however, this was more common among those who learned a “not elevated” amyloid-β PET scan result (65% vs. 56%).

Some interviewees described having concerns about their family member’s or friend’s memory at baseline, though individuals had to have a CDR of 0 (i.e., a score indicating normal cognition and functioning) to participate in REVEAL-SCAN. A “not elevated” amyloid-β PET scan result offered reassurance and led to reframing of those baseline concerns. For instance, a husband who had “attributed memory lapses … to the onset of Alzheimer’s, the early stages” reinterpreted them as “normal aging.” By comparison, learning an “elevated” amyloid-β PET scan result served to validate concerns. One woman stated it was “not surprising” her sister was “a little off” in light of what she learned.

Additionally, after learning an “elevated” amyloid-β PET scan result, a third of interviewees described themselves as being “just a little bit more aware of” their family member’s or friend’s memory and thinking or watching for “developing symptoms.” One daughter described herself as “just watching [my mother’s memory] in the back of my mind a little bit more.” Another daughter reported, “I’m looking for it a lot closer than I otherwise would have.”

Health Behaviors

A third of all interviewees reported their family member or friend had changed health behaviors after learning their AD dementia risk. The most frequent change was increased physical exercise, followed by cognitive activities—“memory games,” “Sudoku and other kinds of puzzles,” “taking Spanish online,” or “reading … brain teaser magazines”—and dietary changes. Interviewees attributed these changes to various causes, including retirement and “getting older,” as well as the AD dementia risk information.

A third of interviewees—primarily spouses and significant others—indicated they had changed their own health behaviors. The most frequent changes were in diet, exercise, and cognitive activity; several described taking dietary supplements. Many interviewees who learned an “elevated” amyloid-β PET scan result attributed the changes to learning their family member’s or friend’s AD dementia risk information. One man, whose wife had changed her diet in response to learning her “elevated” result, explained, “If we’re living together, we might as well eat the same foods and so I eat more salads.” Another spouse explained, “[I]f I’m in better health, I [have a] better chance of being able to help her if she needs it.” For those who learned a “not elevated” result, changes were more likely to be made “just in case” or because it was “the right thing health wise.”

Future Plans

Interviewees who learned an “elevated” amyloid-β PET scan result were nearly three times as likely to report changes to their friend or family member’s future plans than interviewees who had learned a “not elevated” result (30% vs. 12%). The most common changes across both groups were in financial planning, legal planning, use of leisure time, and living arrangements. A man explained that after receiving an “elevated” result, his friend “seems to be getting everything organized.” One son described his dad “looping me in more” to financial decisions and planning “to visit [family] more often” after getting an “elevated” result. Some interviewees reported that their friends or family members who received a “not elevated” result felt “freer to make plans.”

A fifth of spouses and significant others reported that their own future plans had shifted in light of the AD dementia risk information. One wife described how the “elevated” amyloid-β PET scan result made her and her husband “a little more mindful like, ‘Okay, this isn’t something we can put off for another 10 years.’” Another wife described that after learning her husband’s “not elevated” result “we feel freer” planning for the future.

Comparing amyloid-β PET scan results to other test results

Two-thirds of interviewees described the amyloid-β PET scan result as different than other medical test results. One declared, “[I]t’s a little bit different because this is memory, and [there’s] a little bit more, I think, emotional attachment to it.”

About 1 in 5 compared the amyloid-β PET scan favorably to tests for cancer, describing cancer as “scarier” or “more serious.” They also noted the immediacy of a cancer diagnosis, whereas a diagnosis of dementia is temporally distant: “If you’re going to get Alzheimer’s you’re looking at 8 to 10 years [from now].”

About 10% of interviewees focused not on the amyloid-β PET scan result per se but on medical actionability to differentiate it from other medical test results. One wife observed, “[O]ther medical tests often have a remediation for the result if the result is not good, whereas…in this case…it’s finding out that you very likely might have a disease for which you can do nothing.” A husband echoed, “[M]edical tests are frequently things that you can do something about. … [T]here’s no cure for Alzheimer’s, … that’s the disease we don’t want to get.” Another questioned, “[W]hy do the test if there’s no treatment?”

Advice to others

Many interviewees described the opportunity to learn AD dementia risk information as “helpful.” One explained, “[H]aving knowledge is better than not having it because you have the possibility of acting on it.” Yet, they cautioned others to reflect on their capacity and desire to learn risk information, suggesting, for instance, that there is a “need to think and maybe talk to a professional about…the impact on their emotional well-being and physical well-being…and if they were prepared for that.” Interviewees also emphasized the importance of being engaged with and supportive of a family member or friend who learns their AD dementia risk. A sister elaborated, “[W]hatever the results are, try not to let it change the way [you] feel about this particular person. Don’t go out and tell anyone else about the result. And if it’s something…negative…, try to be as helpful [as possible] to the person and their well-being.”

Discussion

Prior studies have examined the effects of disclosing AD dementia risk to cognitively unimpaired persons and also to care partners of adults with mild cognitive impairment (MCI).22,23 This study is the first to examine how such disclosure affects cognitively unimpaired persons’ family members and friends; we find important parallels with past research. Our results suggest that, if adults with preclinical AD become “patients in waiting,” their family members become “pre-caregivers,” offering support in the present and anticipating future care responsibilities.15

Consistent with other studies showing that cognitively unimpaired adults generally understand the meaning of amyloid-β PET scan results, we found high levels of understanding amongst our (mostly highly educated) interviewees.7 Their emotional reactions to the amyloid-β PET scan results paralleled those of cognitively unimpaired older adults and also of care partners for individuals with MCI.9,24 They, too, fear the prospect of AD and so express relief or disappointment depending on the results.

Cognitively unimpaired adults who have received an “elevated” amyloid-β PET scan result describe that result as different from other medical test results because their mind is an important facet of their identity, and if others learn the result, they may experience stigmatization and discrimination.9,14 The individuals we interviewed also saw the amyloid-β PET scan result as different. Notably, however, they compared the amyloid-β PET scan result favorably to other medical test results, as the presence of amyloid-β did not guarantee the onset of dementia, and if cognitive impairment occurred, it was likely years away. They did not invoke stigma to the extent cognitively unimpaired persons with AD biomarkers do.

Interestingly, multiple interviewees questioned the utility of disclosing dementia risk information given the lack of medical actionability. This suggests availability of a disease-modifying therapy may affect family members’ desire for and the perceived utility of AD dementia risk information. Interviewees’ answers resonate with both current clinical practice guidelines recommending against AD biomarker testing and APOE genetic testing for cognitively unimpaired adults, as well as with ethical debates over the propriety of disclosure.25–28

Many interviewees, however, noted that AD dementia risk information—despite its lack of medical actionability—is nevertheless actionable. They valued the information, which allowed for health behavior change and pre-planning. This is consistent with research showing that cognitively unimpaired individuals use AD dementia risk information to adopt new health behaviors and plan ahead.9,29,30 Our findings are also consistent with studies showing that amyloid-β PET scan results can lead family members of patients with MCI to change health behaviors and engage in advance planning.24

Past work with cognitively unimpaired adults suggests that learning an “elevated” amyloid PET scan result can validate existing subjective cognitive complaints or raise new concerns.9 We found that AD dementia risk information can also influence family members’ and friends’ perceptions of memory and thinking. Relatedly, prior studies suggest that some cognitively unimpaired individuals share their AD biomarker results with others because they would like to be monitored for changes in cognition.14,31 Others, though, perceive monitoring as intrusive.14,32 We found disclosure of AD dementia risk information can prompt monitoring, suggesting a point of friction if patients and families do not agree on monitoring.

Limitations

This small, relatively homogenous sample was highly educated, affluent, and predominantly White, which constrains generalizability. Interviewees were recruited only after their participation in REVEAL-SCAN was complete; therefore, time from disclosure varied. There was no pre-disclosure interview, which may introduce recall bias. All REVEAL-SCAN participants underwent a standardized education and risk disclosure process; while this is a strength of the present study, results may differ when education and disclosure processes are heterogeneous.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest receiving a diagnosis of preclinical AD will be meaningful to patients and families and could lead to the emergence of a pre-caregiver role. Further research ought to examine this role in broader populations and explore how the experience evolves over time, particularly with the onset of cognitive decline. These results will assist clinicians in understanding the impact AD risk information has on family members and friends and to consider these different reactions when communicating such information.

IMPACT STATEMENT.

We certify that this work is novel. This is the first study to examine the impact on family members of learning a cognitively unimpaired older adult’s Alzheimer’s disease biomarker result and a personalized risk estimate for dementia by age 85.

KEY POINTS.

Key Points

Family members generally understood the cognitively unimpaired older adult’s dementia risk information and considered it valuable.

Alzheimer’s disease risk information perceived as favorable elicited feelings of happiness and relief; unfavorable information elicited disappointment, as well as increased awareness of cognitively unimpaired older adult’s memory and monitoring for incipient changes in cognition.

Family members encouraged others to reflect on their capacity and desire for learning a cognitively unimpaired older adult’s dementia risk information, which was viewed as different than other medical information.

Why does this matter?

Guidelines for the appropriate use and disclosure of AD biomarker results to cognitively unimpaired older adults should recognize the familial impact and account for the needs and interests of both the individual and family.

FUNDING

This research was supported by grants 1RF1-AG-047866, RF1AG047866-01A1S3, P30-AG-053760, and P30-AG-010124 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Largent is supported by the National Institute on Aging (K01-AG064123) and a Greenwall Faculty Scholar Award.

Sponsor’s Role

The funders had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to report.

Contributor Information

Emily A. Largent, Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine.

Sara J. Feldman, Department of Health Behavior and Health Education, University of Michigan School of Public Health.

Wendy R. Uhlmann, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Genetic Medicine, Department of Human Genetics, University of Michigan School of Medicine.

J. Scott Roberts, Department of Health Behavior and Health Education, University of Michigan School of Public Health.

Jason Karlawish, Department of Medicine, Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy, Department of Neurology, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2018;14(4):535–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattke S, Cho SK, Bittner T, Hlávka J, Hanson M. Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s pathology and the diagnostic process for a disease-modifying treatment: Projecting the impact on the cost and wait times. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2020;12(1):e12081. doi: 10.1002/dad2.12081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schindler SE, Bateman RJ. Combining blood-based biomarkers to predict risk for Alzheimer’s disease dementia. Nat Aging. 2021;1(1):26–28. doi: 10.1038/s43587-020-00008-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brookmeyer R, Abdalla N. Estimation of lifetime risks of Alzheimer’s disease dementia using biomarkers for preclinical disease. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2018;14(8):981–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brookmeyer R, Abdalla N, Kawas CH, Corrada MM. Forecasting the prevalence of preclinical and clinical Alzheimer’s disease in the United States. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2018;14(2):121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Timmermans S, Buchbinder M. Patients-in-Waiting: Living between Sickness and Health in the Genomics Era. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(4):408–423. doi: 10.1177/0022146510386794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mozersky J, Sankar P, Harkins K, Hachey S, Karlawish J. Comprehension of an Elevated Amyloid Positron Emission Tomography Biomarker Result by Cognitively Normal Older Adults. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(1):44–50. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grill JD, Raman R, Ernstrom K, et al. Short-term Psychological Outcomes of Disclosing Amyloid Imaging Results to Research Participants Who Do Not Have Cognitive Impairment. JAMA Neurol. Published online August 10, 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Largent EA, Harkins K, Dyck CH van, Hachey S, Sankar P, Karlawish J. Cognitively unimpaired adults’ reactions to disclosure of amyloid PET scan results. PLOS ONE. 2020;15(2):e0229137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Largent EA, Terrasse M, Harkins K, Sisti DA, Sankar P, Karlawish JHT. Attitudes toward physician-assisted death from individuals who learn they have an Alzheimer disease biomarker. JAMA Neurology. 2019;76(7):864–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grill JD, Cox CG, Harkins K, Karlawish J. Reactions to learning a “not elevated” amyloid PET result in a preclinical Alzheimer’s disease trial. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy. 2018;10(1):125. doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0452-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burns JM, Johnson DK, Liebmann EP, Bothwell RJ, Morris JK, Vidoni ED. Safety of disclosing amyloid status in cognitively normal older adults. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2017;13(9):1024–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wake T, Tabuchi H, Funaki K, et al. Disclosure of Amyloid Status for Risk of Alzheimer Disease to Cognitively Normal Research Participants With Subjective Cognitive Decline: A Longitudinal Study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2020;35:153331752090455. doi: 10.1177/1533317520904551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Largent EA, Stites SD, Harkins K, Karlawish J. “That would be dreadful”: The Ethical, Legal, and Social Challenges of Sharing Your Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarker and Genetic Testing Results with Others. Journal of Law and the Biosciences. 2021;(8):lsab004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Largent EA, Karlawish J. Preclinical Alzheimer Disease and the Dawn of the Pre-Caregiver. JAMA Neurol. Published online March 11, 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Werner P, Goldstein D, Buchbinder E. Subjective Experience of Family Stigma as Reported by Children of Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. Qual Health Res. 2010;20(2):159–169. doi: 10.1177/1049732309358330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stites SD, Gill J, Largent EA, et al. P4–200: EFFECTS OF ADVANCES IN BIOMARKER-BASED DIAGNOSIS AND DISEASE-MODIFYING TREATMENT ON ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE STIGMA. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2019;15:P1353–P1353. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.06.3862 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grill JD, Raman R, Ernstrom K, Aisen P, Karlawish J. Effect of study partner on the conduct of Alzheimer disease clinical trials. Neurology. 2013;80(3):282–288. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827debfe [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grill JD, Monsell S, Karlawish J. Are Patients Whose Study Partners Are Spouses More Likely to be Eligible for Alzheimer’s Disease Clinical Trials. DEM. 2012;33(5):334–340. doi: 10.1159/000339361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/WNL.43.11.2412-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harkins K, Sankar P, Sperling R, et al. Development of a process to disclose amyloid imaging results to cognitively normal older adult research participants. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy. 2015;7:26. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0112-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim H, Lingler JH. Disclosure of amyloid PET scan results: A systematic review. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. 2019;165:401–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erickson CM, Chin NA, Johnson SC, Gleason CE, Clark LR. Disclosure of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease biomarker results in research and clinical settings: Why, how, and what we still need to know. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring. 2021;13(1). doi: 10.1002/dad2.12150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grill JD, Cox CG, Kremen S, et al. Patient and caregiver reactions to clinical amyloid imaging. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2017;13(8):924–932. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson KA, Minoshima S, Bohnen NI, et al. Appropriate use criteria for amyloid PET: A report of the Amyloid Imaging Task Force, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2013;9(1):E1–E16. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson KA, Minoshima S, Bohnen NI, et al. Update on appropriate use criteria for amyloid PET imaging: dementia experts, mild cognitive impairment, and education. J Nucl Med. 2013;54(7):1011–1013. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.127068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grill JD, Johnson DK, Burns JM. Should we disclose amyloid imaging results to cognitively normal individuals? Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2013;3(1):43–51. doi: 10.2217/nmt.12.75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim SYH, Karlawish J, Berkman BE. Ethics of genetic and biomarker test disclosures in neurodegenerative disease prevention trials. Neurology. 2015;84(14):1488–1494. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chao S, Roberts JS, Marteau TM, Silliman R, Cupples LA, Green RC. Health Behavior Changes After Genetic Risk Assessment for Alzheimer Disease: The REVEAL Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22(1):94–97. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31815a9dcc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor DH, Cook-Deegan RM, Hiraki S, Roberts JS, Blazer DG, Green RC. Genetic Testing For Alzheimer’s And Long-Term Care Insurance. Health Affairs. 2010;29(1):102–108. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ashida S, Koehly LM, Roberts JS, Chen CA, Hiraki S, Green RC. The role of disease perceptions and results sharing in psychological adaptation after genetic susceptibility testing: the REVEAL Study. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2010;18(12):1296–1301. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berridge C, Wetle TF. Why Older Adults and Their Children Disagree About In-Home Surveillance Technology, Sensors, and Tracking. Gerontologist. Published online 2020. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]