Graphical abstract

Keywords: COVID-19, Vaccine acceptance, Thailand, Expatriate

Abstract

Background

COVID-19 pandemic is a worldwide problem. Vaccination as primary prevention is necessary. Thailand is in the initial phase of the vaccination program. However, the demand for this vaccine among Thais and expatriates living in Thailand is still unknown. This study aims to assess acceptance, attitude, and determinants for COVID-19 vaccination among Thai people and expatriates living in Thailand.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in Thailand during May 2021. An online survey (REDcap) was distributed through online social media platforms. Adult (>18 years old) Thai and expatriates living in Thailand were invited. Any person who already received any COVID-19 vaccine was excluded from this study.

Result

One thousand sixty-six responses were collected in this survey. A total of 959 were available for analysis. Six hundred thirty-seven 637 responses were from Thais and 322 responses from expatriates living in Thailand. The acceptance rate was significantly higher among expatriates than local people (57.8% vs 41.8%, p-value < 0.001). The acceptance rate increased up to 89.0–91.3% if they could select the vaccine brand, and 80.7–83.2% when they were recommended by the health care professionals. Both groups had a similar mean attitude score toward COVID-19 vaccination. Being Thai, health care worker, good compliance to social distancing, accepting serious side effects at level 1 per 100,000, and having a good attitude toward COVID-19 vaccination were associated with vaccine acceptance.

Conclusion

Thailand's COVID-19 vaccination program could improve the acceptance rate by informing the public about vaccine efficacy, vaccine benefit, and vaccine safety. Moreover, supplying free of charge high efficacy alternative vaccines and letting all people living in Thailand make their own vaccine choices could increase the acceptance rate.

1. Introduction

The current COVID-19 pandemic has been a major problem involving more than 175 million cases worldwide [1]. The advent of the COVID-19 vaccination, as part of the primary prevention, could help reduce disease transmission and promote herd immunity. Recently, emergency use authorization (EUA) for this vaccine was implemented in many countries, including Thailand. Due to vaccine scarcity, the Thailand COVID-19 vaccination program primarily prioritized the reduction of severe cases and mortality to maintain the integrity of country’s healthcare system. Therefore, the initial targets were frontline healthcare workers (HCW), people with comorbidities, and the elderly. As the vaccine gains availability, it will be distributed to the public to restore the country’s economy and social activities. Nonetheless, recent evidence showed that only 6.25% of Thailand’s population received this vaccine. [2], [3] Moreover, around 2.6 million expatriates currently staying in Thailand were at lower priority regarding the free government-administered vaccination because most vaccines were reserved for locals. [4] Expatriates are a subgroup of long-term travelers who live outside their native country for a specific reason, usually for occupational purposes frequently staying for longer than six months. [5] According to the 2010 Thailand national census, non-Thais made up 4.1% (2.7 million) of the population. 57,000 came from the United States, 200,000 from Europe, 13,000 from Australia/New Zealand, and the remainder were Asian [6].

COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate varies between countries from 23.6% to 97%. [7].

Rather high COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate was found in Thailand neighboring countries (eg. Indonesia and Malaysia) by 93–94% [7], [8]. These numbers were even higher compared to China’s (72–91.3%) which was the first country to report the disease [9], [10]. Among healthcare workers (HCWs), the priority in most countries was 76.4% among Chinese HCWs [9]. Similarly, the US HCWs also had an acceptance rate of 57.5% which was even lower than their Chinese counterparts [11]. Half of the HCWs in some countries need more evidence regarding vaccine safety before considering receiving the vaccines. Physicians were found to have 1.6 fold more acceptance rate compared to other healthcare professions including nurses, paramedics, and pharmacists (80% vs. 31.6–33.6%) [11], [12]. The lower vaccine acceptance rate poses a problem as it would be insufficient to prevent disease transmission. Studies have found various concerns regarding this vaccine. Approximately 28.4% of the people are worried about the vaccine’s side effects, efficacy, and safety since many vaccines are produced using new techniques or technologies within a short time. Some vaccines still need more evidence to verify their safety and efficacy before the conventional approval of vaccines [10], [11], [13], [14]. Other factors were found to affect the vaccine acceptance rate. An Indonesian study reported that an increase in the vaccine's efficacy from 50% to 95% can boost the acceptance rate from 63% to 90% [15]. Vaccine production from the EU, the efficacy of about 90%, and around 1 per 100,000 severe side effects were found to increase the acceptance rate (from 27.4% to 61.3%) by a study in France [14]. Awareness of individual susceptibility to COVID-19, history of previous influenza vaccine, a suggestion from physicians, and prior COVID-19 test can improve the vaccine acceptance rate by 1.9–4.7 fold [9], [15], [16], [17] Moreover, other factors including increasing age, a ratio of infected people in the population and the disease’s mortality rate were found to increase the acceptance rate [11], [18]. People who previously rejected annual influenza vaccination were more likely to reject the COVID-19 vaccination [11]. Negative information about the vaccine can decrease acceptance by 15% [17]. There was also a decline in acceptance rate by 9.4% among the people in China and Hong Kong during the third wave of outbreak compared to the initial outbreak due to the escalating report about the vaccines’ side effects [19].

Currently, Thailand is still in the initial phase of the COVID-19 vaccination program. Information regarding the demand for vaccines among Thai people and long-term expatriates living in Thailand is still unknown. This study aims to evaluate acceptance, attitude, and determinants for COVID-19 vaccination among Thai people and expatriates living in Thailand. This finding could guide the strategy for the vaccination, solution for any potential threats of vaccine hesitancy, and promote a positive attitude toward vaccination. Communication strategy, shaped by academic evidence, would then be implemented for different groups of people to facilitate the acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccination in Thailand.

2. Method

2.1. Setting and study design

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in Thailand during May 2021. An online survey was distributed through online social media platforms. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at [Chiang Mai University].[20], [21] REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies, providing 1) an intuitive interface for validated data capture; 2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; 3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages, and 4) procedures for data integration and interoperability with external sources. The main location of distribution is Chiang Mai, Thailand (the 2nd largest province in Thailand) and Bangkok (Thailand's national capital). The questionnaire was divided into four main parts including demographic data, attitude towards COVID-19, attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination, and potential factors affecting COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. The questionnaire was derived from a similar study for face validity. It was tested in a 30-population size pilot study and proven by experts for reliability and validity. The inclusion criteria were adult (>18 years old) Thai and expatriates living in Thailand for at least six months cumulatively. Any person who already received any COVID-19 vaccine would be excluded from this study.

The study size was calculated using the N4studies’ sample size calculation formula using data from compatible studies. The parameter used for the calculation were set as follows, a ratio of vaccine acceptance in the expatriate group (P1) at 0.57 [11], the ratio of vaccine acceptance in the Thai people group (P2) at 0.67 [15], the ratio between P1 and P2 at 1:2, alpha error at 0.05, and beta error at 0.2. The calculated N was 275 for expatriates and 550 for Thais. 10% dropout rate was added which resulted in N of P1 and P2 at 300 and 605, respectively.

2.2. Questionnaire

Participants’ demographic data were collected for the evaluation of the general characteristics of the study groups. Citizenship status was also collected for the designation of participants into the studied groups (Thai people and expatriates living in Thailand). Attitude towards COVID-19 disease including the risk of infection, the general risk of COVID-19 transmission in the country, perceived severity of COVID-19, fear of COVID-19, COVID-19 impact on work, and COVID-19 impact on income was collected. Collection of different aspects of attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine including willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccine in different situations (eg. overall, if it was recommended by health care professionals or employers, if it was free of charge, and if it was available to select vaccine brands) and willingness to recommend COVID-19 to friends and families was done. For potential factors of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, data on most influential people for the vaccine acceptance, concerns for the vaccine, preference of vaccine manufacturer, need for confirmation of the vaccine safety, vaccine efficacy threshold for acceptance, and acceptable rate of mild and serious vaccine side effects was collected.

In this study, acceptance of COVID-19 vaccination was defined as the willingness to receive the vaccine in terms of the proportion of the study population. Attitude towards COVID-19 vaccination and COVID 19 disease were measured using the Likert scale which was classified into five levels from the highest degree (5) to the lowest degree (1).

2.3. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to report the outcomes. Categorical data were described using frequency and percentage. For continuous data describing, mean and standard deviation (S.D.) were used. Because of the normal distribution of data, independent t-test and odds ratios were used for comparison of each baseline characteristic between studied groups. Likert scale data from the attitude variables were categorized into categorical data. A good attitude was defined as strongly agree and agree. The poor attitude was defined as neural, disagree, and strongly disagree. Lastly, binomial logistic regression analysis was used for the univariate and multivariable analysis.

2.4. Ethics consideration

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University (Ethics approval number: COM-2564–08080).

3. Results

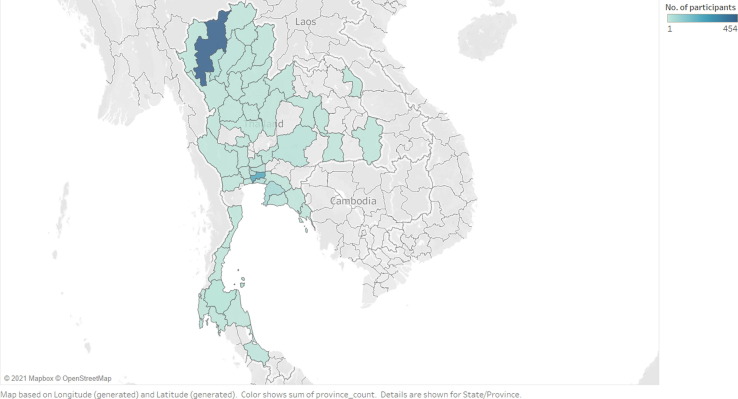

A total of 1,066 responses were collected in this survey. Of those responses, 959 were available for analysis. All missing variables were removed. Of 959 responses, 637 responses came from Thai people and 322 responses came from expatriates living in Thailand. The distribution of survey participants divided by living area is shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

The distribution of survey participants divided by living area.

In the survey among Thai respondents, the mean age was 42 years old (SD 13.9), 66.2% were female (n = 422), 33.8% male (n = 215), 91.3% had bachelor’s degree and above, 60.4% were single, 24.3% were health care workers In the Northern part of Thailand such as Chiang Mai, and Lampang, 42.7% resided and 39.9% resided in Bangkok and Bangkok metropolitan area. The monthly income for 57% was>30,000 THB (>960 USD), 21.5% had underlying medical conditions including diabetes (16.2%), cardiovascular diseases including hypertension (12.5%), and chronic airway disease (11.8%). Those with friends and colleagues infected with COVID-19 were 6.3–6.6% Twenty four point two percent had a test for COVID-19 and 48.8% had a history of influenza vaccination last season.

Among expatriates living in Thailand, the mean age was 56 years old (SD 15.1) with 74.5% males (n = 240) and 25.5% females (n = 82). A bachelor’s degree and above was had by 72.45, with 56.5% married, 30.1% single, 52.2% retired and 23.3% were employees. Those from Europe were 47.2%, 34.8% came from United States of America and Canada, 10.9% came from Australia and New Zealand. Underlying medical conditions for 25.6% included hypertension (46.3%), diabetes (26.8%), and chronic airway diseases (22.0%). Having a friend infected with COVID-19 was 25.2%, 20.2% had been tested for COVID-19, 35.7% had a history of influenza vaccination. (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Demographics data.

| Characteristics | Thai, n(%) | Expatriates n(%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 18-30 years old | 139 (21.8) | 12 (3.7) | <0.001** |

| 31-40 years old | 209 (32.8) | 40 (12.4) | |

| 41-50 years old | 102 (16.0) | 50 (15.5) | |

| 51-60 years old | 100 (15.7) | 66 (20.5) | |

| >61 years old | 87 (13.7) | 154 (47.8) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 215 (33.8) | 240 (74.5) | <0.001** |

| Female | 422 (66.2) | 82 (25.5) | |

| Education | |||

| Less than high School | 9 (1.4) | 5 (1.6) | <0.001** |

| High School | 53 (8.3) | 84 (26.1) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 317 (49.8) | 112 (34.8) | |

| Post graduate level | 258 (40.5) | 121 (37.6) | |

| Marital | |||

| Single | 385 (60.4) | 97 (30.1) | <0.001** |

| Married | 212 (33.3) | 182 (56.5) | |

| Divorced | 25 (3.9) | 39 (12.1) | |

| widowed | 15 (2.4) | 4 (1.2) | |

| Occupation | |||

| Health care worker | 155 (24.3) | 5 (1.6) | <0.001** |

| Civil Servant | 53 (8.3) | 5 (1.6) | |

| Employee | 112 (17.6) | 75 (23.3) | |

| Entrepreneur | 46 (7.2) | 31 (9.6) | |

| Student | 53 (8.3) | 6 (1.9) | |

| Retired | 72 (11.3) | 168 (52.2) | |

| Other | 146 (22.9) | 32 (9.9) | |

| Country of birth | |||

| US/Canada | 0 (N) | 112 (34.8) | |

| Europe | 0 (N) | 152 (47.2) | |

| Asia | 637 (100) | 16 (5.0) | |

| Australia/New Zealand | 0 (N) | 35 (10.9) | |

| Africa | 0 (N) | 5 (1.6) | |

| South America | 0 (N) | 2 (0.6) | |

| Underlying medical conditions | 136 (21.4) | 82 (25.5) | 0.147 |

| Knew someone with COVID-19 | |||

| Yourself | 4 (0.6) | 6 (0.6) | 0.990 |

| Friend | 42 (6.6) | 81 (25.2) | <0.001** |

| Family member | 7 (1.1) | 41 (12.7) | <0.001** |

| Colleagues | 40 (6.3) | 33 (10.2) | 0.029* |

| History of testing for COVID-19 | 154 (24.2) | 65 (20.2) | 0.165 |

| History of receiving flu vaccine | 311 (48.8) | 115 (35.7) | <0.001** |

| Compliance to social distance | |||

| Low | 5 (0.8) | 3 (0.9) | 0.345 |

| Moderate | 236 (37.0) | 104 (32.3) | |

| high | 396 (62.2) | 215 (66.8) | |

| Compliance to mask wearing | |||

| Low | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.9) | <0.001** |

| Mod | 37 (5.8) | 36 (11.2) | |

| High | 600 (94.2) | 283 (87.9) | |

| Compliance to hand washing | |||

| Low | 9 (1.4) | 10 (3.1) | 0.029* |

| Moderate | 129 (20.3) | 82 (25.5) | |

| High | 499 (78.3) | 230 (71.4) | |

| Trust in Thai health care service system | |||

| Low | 128 (20.1) | 35 (10.9) | 0.001** |

| Moderate | 322 (50.5) | 173 (53.7) | |

| High | 187 (29.4) | 114 (35.4) | |

* P-value < 0.05; ** P-value < 0.01.

All respondents reported high compliance to social distancing (62.2–66.8%), high compliance to wearing masks (87.9–94.2%), high compliance to hand washing (71.4–78.3%). Half of the respondents had moderate trust in the Thai health care service system.

Attitude score towards COVID-19 disease was significantly different among Thais and expatriates (Mean score 36.5 vs 34.1, p-value < 0.001). While attitude scores towards COVID-19 vaccination were similar among both groups (mean score 27.2 vs 27.3, p-value 0.682) (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Attitude score towards COVID-19 disease and COVID-19 vaccination among Thais and Expatriates living in Thailand.

| Attitude | n | Mean | SD | Men difference | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude towards COVID-19 | Thai | 637 | 36.5 | 4.66 | 2.413 | <0.001** |

| Expat | 322 | 34.1 | 6.70 | |||

| Attitude towards vaccine | Thai | 637 | 27.2 | 4.70 | −0.144 | 0.682 |

| Expat | 322 | 27.3 | 5.93 |

** P-value < 0.01.

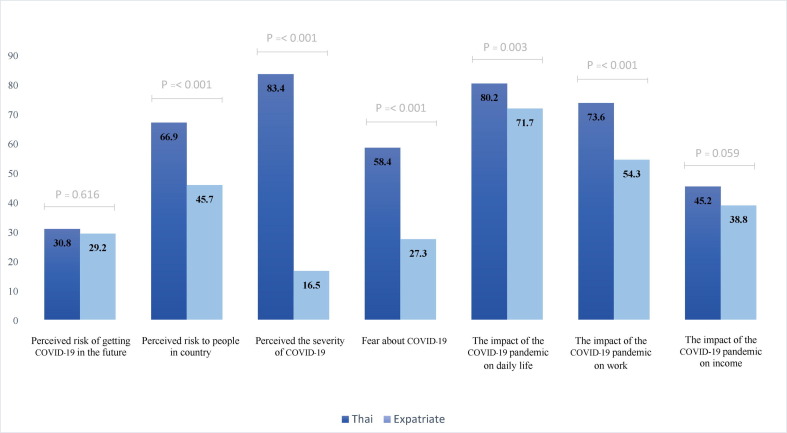

Participants’ attitudes toward COVID-19 are shown in Fig. 2 that compares result from Thais and expatriates living in Thailand, Thai respondents perceived significantly higher risk of getting COVID-19 in Thailand (66.9% VS 45.7%, p-value < 0.001), higher severity of COVID-19 (83.4% VS 16.5%, p-value < 0.001), fear about COVID-19 (58.4% VS 27.3%, p-value < 0.001). Both Thais and expatriates perceived similar risks of getting COVID-19 in the future (30.8% VS 29.2%, p-value 0.616). The current COVID-19 had significant impact for Thai people on daily life (80.2% VS 71.7%, p-value 0.003), on work (73.6% VS 54.3%, p-value < 0.001), but similar impact on income (45.2% vs 38.8%, p-value 0.059).

Fig. 2.

The proportion of participant with good attitude toward COVID-19 disease.

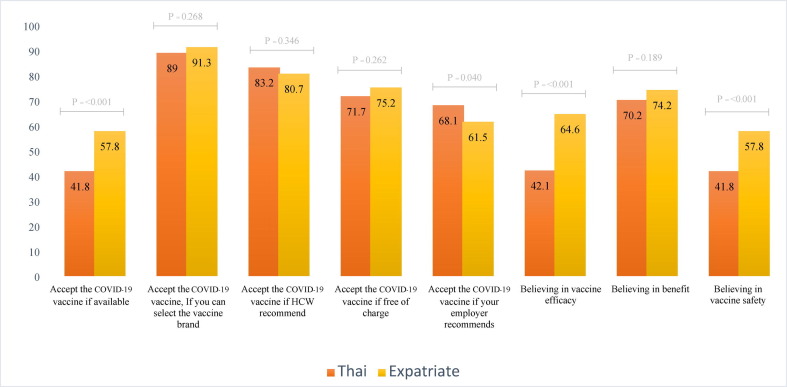

Fig. 3 Expatriates significantly believed in COVID-19 efficacy (64.6% vs 42.1%, p-value < 0.001), vaccine safety (57.8% vs 41.8%, p-value < 0.001). But both groups had approximately 70.2–74.2% in the benefit of the COVID-19 vaccine. Of all participants, 57.8% of expatriates working in Thailand would take it while 41.8% of Thais would accept the available vaccine in Thailand. Unsurprisingly, up to 89–91.3% of participants would accept the COVID-19 vaccine if they can select the vaccine brand. Moreover, the participants would accept the COVID-19 vaccine with the following conditions: recommended by health care personnel (83.5–84.5%), free of charge (71.7–75.2%), recommended by their employers (61.5–68.1%).

Fig. 3.

The proportion of participant with good attitude towards COVID-19 vaccine.

In order to accept COVID-19 vaccination, 87.9% of Thai people made the decision on their own, 65% from vaccine experts and 58.4% from family members. While expatriate’s decisions differed as follows 82.9% from family members, 68.3% their own trust, and 50% from vaccine experts. Thai people had significantly higher concerns than expatriates in many aspects including possible adverse events after vaccination (87% VS 51.2%, p-value < 0.001), vaccine safety (71.1% VS 34.5%, p-value < 0.001), vaccine efficacy (61.5% vs 48.8%, p-value < 0.001), immunity after vaccination (41.6% VS 39.4%, p-value 0.520). But expatriates had different points of concerns such as vaccine manufacturer (48.4% VS 33.3%, p-value < 0.001) and political involvements (38.8% VS 22.6%, p-value < 0.001) (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine acceptance.

| Factors | Thai (n,%) | Expat (n,%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| The biggest influence on getting vaccine | |||

| Myself | 560 (87.9) | 220 (68.3) | <0.001** |

| Family member | 372 (58.4) | 55 (17) | <0.001** |

| Scientist | 254 (39.9) | 140 (43.5) | 0.284 |

| Expert vaccine | 414 (65.0) | 161 (50.0) | <0.001** |

| Government | 78 (12.2) | 55 (17.1) | 0.041* |

| Friend or People I work | 45 (7.1) | 13 (4.0) | 0.063 |

| Community | 22 (3.5) | 20 (6.2) | 0.049* |

| Concerns among responders | |||

| Adverse | 554 (87.0) | 165 (51.2) | <0.001** |

| Vaccine efficacy | 392(61.5) | 157(48.8) | <0.001** |

| Immunity after vaccine | 265 (41.6) | 127 (39.4) | 0.520 |

| Research on vaccine | 205 (32.2) | 67 (20.8) | <0.001** |

| Vaccine authorization | 112 (17.6) | 25 (7.8) | <0.001** |

| Vaccine safety | 453 (71.1) | 111 (34.5) | <0.001** |

| Vaccine manufacturer | 212 (33.3) | 156 (48.4) | <0.001** |

| Political involve | 144 (22.6) | 125 (38.8) | <0.001** |

| Vaccine manufacturer preference | |||

| Domestic | 39 (6.1) | 4 (1.2) | <0.001** |

| Imported | 272 (42.7) | 176 (54.7) | |

|

236 (87.1) | 116 (66.3) | |

|

25 (9.2) | 41(23.4) | |

|

5 (1.8) | 1 (0.6) | |

|

5 (1.8) | 17 (9.7) | |

| No preference | 326 (51.2) | 142 (44.1) | |

| Delay vaccination | |||

| Yes | 358 (56.2) | 121 (37.6) | <0.001** |

|

116 (32.4) | 22 (18.2) | |

|

129 (36.0) | 47 (38.8) | |

|

71 (19.8) | 31 (25.6) | |

|

42 (11.7) | 21 (17.4) | |

| No | 146 (22.9) | 87 (27.0) | |

| Not sure | 133 (20.0) | 114 (35.4) | |

| Level of vaccine efficacy | |||

| Any level | 39 (6.1) | 20(6.2) | 0.369 |

| At least 30% | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | |

| At least 50% | 98 (15.4) | 36 (11.2) | |

| At least 70% | 257 (40.3) | 146 (45.3) | |

| At least 90% | 242 (38.0) | 119 (37.0) | |

| Level of serious side effect | |||

| In 10,000 | 30 (4.7) | 32 (9.9) | <0.001** |

| In 100,000 | 136 (21.4) | 112 (34.8) | |

| In 1,000,000 | 471 (73.9) | 178 (55.3) | |

| Level of mild side effect | |||

| In 10 | 94 (14.8) | 121 (37.6) | <0.001** |

| In 100 | 252 (39.6) | 103 (32.0) | |

| > 1 in 100 | 291 (45.7) | 98 (30.4) | |

* P-value < 0.05; ** P-value < 0.01.

Thai respondents prefer imported COVID-19 vaccine which mainly came from the USA (87.1%) and European manufacturers (9.2%). Similarly, expatriate respondents prefer imported vaccines from the USA (66.3%) and Europe (23.4%). Up to 80% of all respondents would accept the COVID-19 vaccine with an efficacy level of at least 70% and above. The reduction of serious side effects after vaccination including anaphylaxis, stroke-like symptoms from 1 in 1,000,000 to 1 in 100,000 can increase the vaccine acceptance by 52.5% for Thai and 20.5% for expatriates. Thai respondents accept the level of>1 in 100 for mild side effects such as low-grade fever, fatigue, pain at the injection site by 45.7%, while expatriates were more likely to accept the mild side effects at the level of 1 in 100 at 32%. Approximately 36.0–38.8% of respondents would delay this vaccine at least three months due to safety reasons.

Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance were Thai people (aOR = 3.12, 95% CI = 1.13–8.59), age of 41–50 years old (aOR = 6.11, 95% CI = 1.13–33.01), being health care worker (aOR = 5.64, 95% CI = 1.50–21.33), moderate to high compliance to social distancing (aOR 42.44–48.98), good attitude score towards COVID-19 vaccination (aOR 2.20, 95% CI = 1.89–2.57) and accept low level of serious side effects (1 in 100,000) (aOR 9.22, 95% CI = 2.07–40.97) (Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among Thais and Expatriates living in Thailand.

| variable |

Crude OR |

Adjusted OR |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95 %CI) | P value | |

| Country of Birth | ||||

| Expat (reference) | ||||

| Thai | 1.07 (0.74–1.54) | 0.713 | 3.12 (1.13–8.59) | 0.028* |

| Age group | ||||

| 18-30 yrs. (reference) | ||||

| 31-40 yrs. | 1.22 (0.75–1.97) | 0.430 | 0.59 (0.17–1.96) | 0.385 |

| 41-50 yrs. | 3.09 (1.59–6.00) | <0.001** | 6.11 (1.13–33.01) | 0.035* |

| 51-60 yrs. | 2.41 (1.31–4.41) | 0.005** | 2.20 (0.48–10.19) | 0.313 |

| >60yrs. | 2.05 (1.21–3.48) | 0.007** | 3.00 (0.42–21.05) | 0.274 |

| Occupation | ||||

| Others (reference) | ||||

| Health care worker | 1.959 (1.01–3.79) | 0.046* | 5.64 (1.50–21.33) | 0.011* |

| Civil servant | 0.90 (0.33–2.43) | 0.900 | 3.25 (0.40–26.37) | 0.270 |

| Employee | 0.50 (0.26–0.96) | 0.500 | 1.13 (0.38–3.36) | 0.824 |

| Entrepreneur | 0.28 (0.13–0.57) | <0.001** | 1.12 (0.26–4.77) | 0.879 |

| Student | 0.22 (0.10–0.47) | <0.001** | 0.41 (0.09–1.87) | 0.250 |

| Retired | 0.75 (0.39–1.45) | 0.397 | 3.48 (0.59–20.73) | 0.170 |

| History of flu vaccine | 2.57 (1.74–3.78) | <0.001** | 1.01 (0.46–2.21) | 0.985 |

| History of vaccine refusal | 0.38 (0.24–0.61) | <0.001** | 0.60 (0.22–1.63) | 0.318 |

| Compliance to social distancing | ||||

| Low (reference) | ||||

| Moderate | 5.42 (1.31–22.33) | 0.019* | 48.98 (2.34–1,023.85) | 0.012* |

| High | 5.43 (1.34–22.09) | 0.018* | 42.44 (2.08–865.90) | 0.015* |

| Trust in health care | ||||

| Low (reference) | ||||

| Moderate | 2.23 (1.47–3.38) | <0.001** | 0.68 (0.29–1.60) | 0.373 |

| High | 4.41 (2.61–7.46) | <0.001** | 1.52 (0.44–5.27) | 0.506 |

| Vaccine preference | ||||

| No (Reference) | ||||

| Imported | 0.61 (0.43–0.88) | 0.008** | 1.02 (0.46–2.26) | 0.960 |

| Domestic | 0.47 (0.22–1.00) | 0.049* | 1.13 (0.19–6.84) | 0.894 |

| Acceptance level | ||||

| Any level (Reference) | ||||

| At least 50% | 3.35 (1.11–10.12) | 0.032* | 5.37 (0.69–41.64) | 0.108 |

| At least 70% | 1.35 (0.72–3.75) | 0.233 | 2.69 (0.58–12.55) | 0.209 |

| At least 90% | 0.40 (0.18–0.87) | 0.021* | 0.73 (0.17–3.18) | 0.679 |

| Acceptance level of serious side effect | ||||

| 1 in 10,000 (reference) | ||||

| 1 in 100,000 | 1.28 (0.57–2.87) | 0.545 | 9.22 (2.07–40.97) | 0.004** |

| 1 in 1,000,000 | 0.80 (0.38–1.66) | 0.545 | 4.35 (0.94–20.22) | 0.061 |

| Acceptance level of mild side effect | ||||

| 1 in 10 (reference) | ||||

| 1 in 100 | 0.71 (0.41–1.22) | 0.217 | 0.72 (0.25–2.09) | 0.543 |

| 1 in > 100 | 0.39 (0.24–0.66) | 0.45 (0.06–1.31) | 0.145 | |

| Attitude score towards COVID-19 | 1.14 (1.10–1.18) | <0.001** | 1.05 (0.97–1.14) | 0.213 |

| Attitude towards vaccine score | 2.00 (1.78–2.24) | <0.001** | 2.20 (1.89–2.57) | <0.001** |

* P-value < 0.05; ** P-value < 0.01.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among Thais and expatriates living in Thailand. The acceptance rate was significantly higher among expatriates living in Thailand than local Thai people (57.8% VS 41.8%, p-value < 0.001). While the mean attitude score toward COVID-19 disease among Thais was higher than expatriates (36.5 VS 34.1, p-value < 0.001). Both groups had a similar mean attitude score toward COVID-19 vaccination. Vaccine acceptance was affected by a combination of factors and fluctuated throughout time.

Recently, Thailand suffered from the third wave of COVID-19. According to the COVID-19 situations in Thailand, we have between 10,000 and 20,000 new cases each day, with delta variant (69.1%), alpha variant (28.2%), and beta variant (2.7%)[22], [23]. Due to vaccine shortages, Thailand's Covid-19 immunization campaign focused on reducing severe cases and death to preserve the country's healthcare system. As a result, frontline healthcare professionals, those with comorbidities, and the elderly were the first to be targeted. Because most vaccines were reserved for Thais, expatriates were given lesser priority when it came to free government-provided immunization.[22], [23] The low acceptance rate, low vaccination coverage (3.5%), and static vaccination program were major challenges for Thailand to achieve herd immunity.[24] Thus, COVID-19 may continuously cause a big impact on health care service systems, the economy, and social activities. There were five COVID-19 vaccines registered and approved under EUA in Thailand. Only CoronaVac (manufactured in China) and AstraZeneca (locally made under a technology transfer deal) were two major sources of vaccine supplies.

The vaccine acceptance among expatriates residing in Thailand (57.8%) was similar to the previous studies done in Western countries such as the US (52.0–57.5%), Italy (53.7%), and France (58.9%) [7], [25], while Thai people had lower acceptance rate (41.8%). The majority of Thai and other global citizens decided on their own. [11] Participants who had a high-risk rating of disease severity and prevalence were more likely to obtain the COVID-19 vaccination, which is now available on the market, although the vaccine's effectiveness was insufficient to prevent symptomatic COVID-19 infection. Expectedly, less than half (41.8–42.1%) of Thai respondents believed in CoronaVac efficacy and safety. The efficacy of this vaccine was approximately 51% for preventing symptomatic COVID-19.[26] which is lower when compared to other vaccines in the market. Moreover, reports of unusual stroke-like side effects or other focal neurological symptoms after CoronaVac vaccination could increase hesitancy for vaccine acceptance. Surprisingly, the vaccine acceptance rate increased up to 89.0–91.3% for both groups if they can select the vaccine by themselves. Our study revealed that 66.3–87.1% of respondents prefer imported vaccines, especially from the US which reported high efficacy (94–95% for symptomatic prevention) [27], [28]. The change of willingness was similar to the study in Indonesia and France which reported an increase from 63% to 90% and 27.4% to 61.3% respectively when the vaccine efficacy changes from 50% to 95%. [15], [29].

Health care workers' recommendations showed a better vaccine acceptance by 80.7–83.2%. A value recommendation from a primary doctor in China, Congo, and Indonesia, is associated with a 1.6–2.3-fold increase in accepting vaccination against COVID-19. [12], [15], [30]. Perceived risk of COVID-19 infection and its severity in their living area increase vaccine willingness by 1.9–2.2 folds among Chinese and Indonesian populations. [15], [19], [31] Interestingly, misinformation or negative information could lower the intention for vaccinating among the UK, US, and China by 1.5–2.4%.[17], [32], [33] Thus, trained and educated clinicians should accurately communicate the risks and benefits of each vaccine on an individual level especially those with hesitancy. [19], [34], [35] Employer recommendation could be other options to help increase willingness to receive vaccines. 61.5–68.1% of this study would accept vaccines if their employers recommended. This result was similar to a global survey across 19 countries which reported a rate of acceptance of 60.1% [25].

The acceptance level of serious side effects at the rate of 1 in 100,000 was associated with 9.2 folds when compared to 1 in 10,000. 78.3% of Thais and 82.3% of expatriates living in Thailand would accept vaccines with at least 70% efficacy. Thai people had a 3.1 times higher rate to accept vaccination than expatriates. But approximately 36.0–38.8% of Thais could wait at least three months until the vaccine safety was confirmed. A study among the Chinese population and HCW in Saudi Arabia reported a similar result (47.8–50.3%) for delaying immunization. [16], [19] Participants who believed the benefits of the COVID-19 vaccine outweighed the risks would accept the currently available vaccine, while those who were still indecisive could wait at least one to three months until the benefit and safety of the vaccine were proven. Therefore, the Thai government should provide more alternative vaccine options with at least 70% to prevent symptomatic infection and have 1 in 100,000 serious side effects to increase the public acceptability on the COVID-19 vaccine confidence. Major concerns among Thai responders were adverse event after vaccination which was significantly higher than expatriates (87.0% vs 51.2%, p-value 0.001) followed by vaccine safety (71.1% vs 34.5%, p-value < 0.001), and vaccine efficacy (61.5% vs 48.8% p-value < 0.001). Results were similar to the US health care personnel study which revealed 47% of participants were concerned about adverse events/side effects after taking the vaccine [11]. Moreover, 63.2% of working people in Hong Kong and China doubt vaccine effectiveness which put the COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate at only 34.8%-44.2%. Moreover, the acceptance rate in China is decreased by 23% between two different epidemic phases due to safety concerns. [10], [30].

Adults 40 years old and above tended to obtain vaccinations sooner compared to younger adults, which is similar to the result from many studies [8], [11], [13], [36], [37]. Vaccination acceptability was 5.6 times (95% CI 1.50–21.33, p-value 0.011) higher among HCWs. Participants who were vaccinated with influenza last season had 2.6 times (95% CI 1.7–3.8, p-value < 0.001) higher rate to accept vaccination. Mainland Chinese populations showed similar results with an OR of 1.9 [19] Although, the acceptance rate in this study was low, most participants still had high compliance for personal protection such as wearing a mask (87.9–94.2%), social distancing (62.2–66.8%), and handwashing (71.4–78.3%) (10) Disease exposure was not demonstrated to be a significant predictor of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in our study. To increase COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Thailand, alternative vaccines with at least 70% efficacy and low serious adverse events should be provided. Sufficient public information on vaccine registration, efficacy, benefit, safety, and improved vaccine accessibility to all people living in Thailand could help increase the acceptance.

This research attempted to reach out to all Thais and expatriates in Thailand, however, participants came from 48 provinces across the country (62 %). The majority of participants were from Bangkok, Bangkok metropolitan area, and Chiang Mai, which are the most densely settled areas for expatriates. The limitation of this study was convenience sampling. Anti-vaxxer or pro-vaxxer may be a common pattern among those who agreed to participate in this study. As a result, they could distribute this online questionnaire to the same group of interested people.

Future research should collect more data from participants living in other parts of Thailand especially in Phuket, Pattaya, and the Northeastern areas. Social media's impact on vaccination acceptance. Stratified sampling by living region and age group would give more accurate information. Focusing on high-risk groups, such as the elderly or persons with chronic health conditions, may provide a better perspective and approach to changing COVID-19 vaccination preferences. Moreover, the level of COVID-19 vaccination concern among Thais should be examined to assist policymakers in developing effective strategies to increase COVID-19 vaccine acceptability.

5. Conclusion

Low vaccination acceptance has posed a significant challenge to achieving herd immunity and preventing the spread of COVID-19 infection in Thailand. The Thailand COVID-19 immunization campaign could be successful if evidence-based communication on vaccine efficacy, vaccine benefit, and vaccine safety are implemented, as well as delivering alternative high-efficacy vaccines free of charge to all people living in Thailand. Providing sufficient information to meet public expectations, particularly about the vaccination registration procedure and availability of vaccines, could boost vaccine accessibility and public trust. Health-education programs by healthcare providers were a key factor in improving public perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccination and minimizing vaccine concerns.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper: [Amornphat Kitro (first author) reports financial support and administrative support were provided by Chiang Mai University Faculty of Medicine. Amornphat Kitro (first author) reports a relationship with Chiang Mai University Faculty of Medicine that includes: employment.].

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by the Faculty of Medicine Research Fund, Chang Mai University (Grant number.COM-2564-08080). We wish to express our appreciation to Chiang Mai Expat Club, Pattaya City Expat Club, Health Promotion Unit, Chiang Mai University for their kind cooperation.

Contributors

Conceptualization, A.K.; methodology, A.K., W.S., K.W.; formal analysis and investigation, A.K., W.S., R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K.; writing—review and editing, A.K., C.P., P.R., M.S., R.S.; funding acquisition, A.K.; resources, A.K., P.A., V.S.; supervision, R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Faculty of Medicine Research Fund, Chang Mai University, Chiang Mai province, Thailand (Grant number.COM-2564-08080).

References

- 1.WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jun 14]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int

- 2.Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations - Statistics and Research [Internet]. Our World in Data. [cited 2021 Jun 14]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations

- 3.Thai guideline for covid-19 vaccination Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health. [cited 2021 Jun 14]. Available from: https://ddc.moph.go.th/uploads/files/1729520210301021023.pdf

- 4.International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination [Internet]. [cited 2021 Apr 6]. Available from: http://www.rlpd.go.th/rlpdnew/images/rlpd_1/HRC/CERD%201_3.pdf

- 5.Lin H. Chen, Davidson H. Hamer. Long-Term Travelers & Expatriates - Chapter 9 - 2020 Yellow Book | Travelers’ Health | CDC. [cited 2021 Sep 6]. Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/travel-for-work-other-reasons/long-term-travelers-and-expatriates

- 6.Thailand Population and Housing Census 2010 - National statistical office. [cited 2021 Sep 6]. Available from: http://www.nso.go.th/sites/2014en

- 7.Sallam M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Worldwide: A Concise Systematic Review of Vaccine Acceptance Rates. Vaccines. 2021 Feb;9(2):160. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lazarus J.V., Ratzan S.C., Palayew A., Gostin L.O., Larson H.J., Rabin K., et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):225–228. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu C, Wei Z, Pei S, Li S, Sun X, Liu P. Acceptance and preference for COVID-19 vaccination in health-care workers (HCWs). medRxiv. 2020 Apr 14;2020.04.09.20060103.

- 10.Wang K., Wong E.L.-Y., Ho K.-F., Cheung A.W.-L., Yau P.S.-Y., Dong D., et al. Change of Willingness to Accept COVID-19 Vaccine and Reasons of Vaccine Hesitancy of Working People at Different Waves of Local Epidemic in Hong Kong, China: Repeated Cross-Sectional Surveys. Vaccines. 2021;9(1):62. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaw J., Stewart T., Anderson K.B., Hanley S., Thomas S.J., Salmon D.A., et al. Assessment of US Healthcare Personnel Attitudes Towards Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Vaccination in a Large University Healthcare System. Clin Infect Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kabamba Nzaji M., Kabamba Ngombe L., Ngoie Mwamba G., Banza Ndala D.B., Mbidi Miema J., Luhata Lungoyo C., et al. Acceptability of Vaccination Against COVID-19 Among Healthcare Workers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Pragmatic Obs Res. 2020 Oct;29(11):103–109. doi: 10.2147/POR.S271096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong M.C.S., Wong E.L.Y., Huang J., Cheung A.W.L., Law K., Chong M.K.C., et al. Acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine based on the health belief model: A population-based survey in Hong Kong. Vaccine. 2021;39(7):1148–1156. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verger P., Scronias D., Dauby N., Adedzi K.A., Gobert C., Bergeat M., et al. Attitudes of healthcare workers towards COVID-19 vaccination: a survey in France and French-speaking parts of Belgium and Canada, 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2021;26(3):2002047. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.3.2002047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harapan H., Wagner A.L., Yufika A., Winardi W., Anwar S., Gan A.K., et al. Acceptance of a COVID-19 Vaccine in Southeast Asia: A Cross-Sectional Study in Indonesia. Front Public Health. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qattan A.M.N., Alshareef N., Alsharqi O., Al Rahahleh N., Chirwa G.C., Al-Hanawi M.K. Acceptability of a COVID-19 Vaccine Among Healthcare Workers in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Front Med. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.644300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang K.C., Fang Y., Cao H.e., Chen H., Hu T., Chen Y.Q., et al. Parental Acceptability of COVID-19 Vaccination for Children Under the Age of 18 Years: Cross-Sectional Online Survey. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2020 Dec 30;3(2):e24827. doi: 10.2196/24827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caserotti M., Girardi P., Rubaltelli E., Tasso A., Lotto L., Gavaruzzi T. Associations of COVID-19 risk perception with vaccine hesitancy over time for Italian residents. Soc Sci Med. 2021;272:113688. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J., Jing R., Lai X., Zhang H., Lyu Y., Knoll M.D., et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination during the COVID-19 Pandemic in China. Vaccines. 2020 Sep;8(3):482. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8030482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Minor B.L., Elliott V., Fernandez M., O'Neal L., et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thailand: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data [Internet]. [cited 2021 Sep 6]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int

- 23.Surveillance report on CoVID-19 Variant of Concerns (VOCs) on 17-23 July 2021. Department of Medical Science, Thailand [Internet]. [cited 2021 Sep 6]. Available from: https://www3.dmsc.moph.go.th/post-view/1227

- 24.Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations - Statistics and Research [Internet]. Our World in Data. [cited 2021 Jun 4]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations

- 25.Khubchandani J., Sharma S., Price J.H., Wiblishauser M.J., Sharma M., Webb F.J. COVID-19 Vaccination Hesitancy in the United States: A Rapid National Assessment. J Community Health. 2021;46(2):270–277. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00958-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccines-SAGE-recommendation-Sinovac-CoronaVac-2021.1-eng [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jun 4]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/341454/WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccines-SAGE-recommendation-Sinovac-CoronaVac-2021.1-eng.pdf?fbclid=IwAR00T7VsOx1EOYw_MuK8luGORYVyD14NtWCUpOeYHXAS3ZSuc0zWiB2SXec

- 27.WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccines-SAGE_evaluation-BNT162b2-2020.1-eng.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jun 4]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/338096/WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccines-SAGE_evaluation-BNT162b2-2020.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- 28.WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccines-SAGE_recommendation-mRNA-1273-2021.1-eng.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jun 4]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/338862/WHO-2019-nCoV-vaccines-SAGE_recommendation-mRNA-1273-2021.1-eng.pdf?sequence=5&isAllowed=y

- 29.Schwarzinger M., Watson V., Arwidson P., Alla F., Luchini S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a representative working-age population in France: a survey experiment based on vaccine characteristics. Lancet. Public Health. 2021;6(4):e210–e221. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00012-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J., Lu X., Lai X., Lyu Y., Zhang H., Fenghuang Y., et al. The Changing Acceptance of COVID-19 Vaccination in Different Epidemic Phases in China: A Longitudinal Study. Vaccines. 2021 Mar;9(3):191. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bish A., Yardley L., Nicoll A., Michie S. Factors associated with uptake of vaccination against pandemic influenza: A systematic review. Vaccine. 2011;29(38):6472–6484. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loomba S, Figueiredo A de, Piatek SJ, Graaf K de, Larson HJ. Measuring the Impact of Exposure to COVID-19 Vaccine Misinformation on Vaccine Intent in the UK and US. medRxiv. 2020 Oct 26;2020.10.22.20217513.

- 33.Williams L., Gallant A.J., Rasmussen S., Brown Nicholls L.A., Cogan N., Deakin K., et al. Towards intervention development to increase the uptake of COVID-19 vaccination among those at high risk: Outlining evidence-based and theoretically informed future intervention content. Br J Health Psychol. 2020;25(4):1039–1054. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finney Rutten L.J., Zhu X., Leppin A.L., Ridgeway J.L., Swift M.D., Griffin J.M., et al. Evidence-Based Strategies for Clinical Organizations to Address COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(3):699–707. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Opel D.J., Salmon D.A., Marcuse E.K. Building Trust to Achieve Confidence in COVID-19 Vaccines. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2025672. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherman S.M., Smith L.E., Sim J., Amlôt R., Cutts M., Dasch H., et al. COVID-19 vaccination intention in the UK: results from the COVID-19 vaccination acceptability study (CoVAccS), a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2020 Nov 26:1–10. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1846397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Mohaithef M., Padhi B.K. Determinants of COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance in Saudi Arabia: A Web-Based National Survey. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020 Nov;20(13):1657–1663. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S276771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]