Abstract

Background:

There is a large body of research that has identified bidirectional associations between conduct problems and cannabis use. Despite growing knowledge regarding comorbidities between conduct problems and cannabis use, it remains unclear whether these findings generalize across both males and females. The current study examined sex differences in longitudinal associations between conduct problems and cannabis use in a predominantly Hispanic sample of adolescents followed over a two-year period.

Methods:

Participants were 401 adolescents (89.8% Hispanic, 46% female; Mage = 15.5) taking part in a two-year longitudinal investigation examining the associations between neurocognitive functioning and cannabis use. The sample consisted predominantly of youth selected for risk of cannabis escalation, with 90% reporting using cannabis, nicotine, or alcohol prior to baseline. Negative binomial cross-lagged regressions and simple slope difference tests were used for all analyses.

Results:

We found support for bidirectional associations between conduct problems and cannabis use, controlling for demographics, covariates, and baseline frequencies. Simple slope difference tests revealed that there was a significant, positive association between baseline cannabis use and subsequent conduct problems among females but not males. In contrast, the association between baseline conduct problems and subsequent frequency of cannabis use did not differ as a function of sex.

Conclusions:

Our results underscore the importance of viewing cannabis use as a risk factor for maladjustment rather than solely as a consequence, particularly among female adolescents. Information gained from temporal sequencing of cannabis use and conduct problem symptoms can guide the selection of intervention programs for referred youth.

Keywords: Cannabis Use, Conduct Problems, Adolescence, Sex Differences

1. Introduction

Concurrent and lifetime comorbid psychiatric disorders are common among adolescent cannabis users, with particularly high rates of comorbid conduct problems (Roberts et al., 2007). In contrast to models of addiction that hinge on differential temporal sequencing of cannabis use and internalizing symptoms (e.g., self-medication versus substance-induced enhancement models; Khantzian, 1985; Zvolensky & Schmidt, 2003), theories regarding cannabis use and comorbid conduct problems focus primarily on joint risk rather than on the directionality of their association. For example, there is a large body of research that has identified underlying genetic, neurological, and environmental risk factors associated with both conduct problems and cannabis use (for reviews, see Blair, 2020; Chen et al., 2015). Multiple fMRI studies suggest that dysfunctions in reward processing produce behavioral bias toward immediate rewards associated with both externalizing behaviors and substance use (e.g., Hawes, Waller et al., 2020; Joseph et al., 2009; Jager et al., 2013). Notably, the average age of onset for conduct problems is much earlier than substance use problems (Kessler & Wang, 2008). Nevertheless, these findings do not preclude the possibility of a bidirectional association between cannabis use and changes in conduct problems over time.

Indeed, there is increasing empirical evidence supporting the notion that conduct problems may simultaneously be a risk factor for, and potential consequence of, cannabis use. More specifically, there is strong evidence supporting the link between early conduct problems and later cannabis use (e.g., Bevilacqua et al., 2018; Creemers et al., 2009; Defoe et al., 2018; Hawes et al., 2019; Heron et al., 2013). Multiple longitudinal studies have also found significant associations between adolescent cannabis use and increases in conduct problem symptoms in adolescence (Hawes et al., 2019; Hawes, Pacheco-Colón et al., 2020; cf. Defoe et al., 2018) and adulthood (Brook et al., 2011; Green et al., 2016; Pardini et al., 2015). Despite the growing knowledge regarding comorbidities between conduct problems and cannabis use, it remains unclear whether the aforementioned findings generalize to both males and females. Further examination of sex differences has important implications for the ongoing development of comprehensive etiological models and treatment methods for conduct problems and cannabis use disorders.

There are currently no known longitudinal studies that have examined whether sex moderates the associations between conduct symptoms and cannabis use among adolescents. However, there is some prior research to suggest that the temporal sequencing of conduct problems and cannabis use may differ across sex. Cross-sectional analyses have revealed that males and females are equally likely to experience comorbid conduct problems and cannabis use across adolescence (Miles et al., 2002) and adulthood (Moffitt et al., 2001). However, among those who meet criteria for a cannabis use disorder (CUD), females are more likely than males to meet criteria for comorbid conduct disorder (Diamond et al., 2006; Khan et al., 2013). Given the cross-sectional nature of the aforementioned studies, it is difficult to surmise whether there are sex differences in the temporal sequencing of comorbid conduct problems and cannabis use.

The etiology of comorbid conduct problems and cannabis use may look quite different for males and females. For instance, strong socialization pressures to avoid behavioral problems may reduce girls’ likelihood of childhood-onset conduct problems, resulting in adolescent-onset of conduct problems instead (Chen et al., 2015). Later onset of conduct problems could impact the directionality of comorbidities, as females’ initiation of cannabis use may occur simultaneously with, or even before, the initiation of conduct problems. Later onset of conduct problem symptoms could lead to a stronger association between cannabis use and later conduct problems among females than among males. Additionally, a prospective twin study found that genetic influences appeared to be a stronger factor in explaining the link between conduct problems and cannabis use among adolescent males, whereas environmental influences were a stronger predictor among adolescent females (Verweij et al., 2016). Given that conduct problems often emerge sooner than substance use (Kessler & Wang, 2008), stronger genetic influences found among males may also lead to a stronger association between conduct problems and later cannabis use among males than among females.

Sex-related differences in brain circuitry and development may also influence associations between conduct problems and cannabis use (Calakos et al., 2017), and may place females at greater risk for adverse cannabis-related effects. For example, McQueeny and colleagues (2011) surmised that, given sex-specific timing differences in brain development (for a review, see Giedd et al., 2012), male brains may be more resilient to the deleterious effects of cannabis use. This is consistent with findings that females are more likely to enter treatment for a CUD sooner and after less cumulative use than males (Crane et al., 2013). Given their increased likelihood to enter treatment, female cannabis users may be reporting more negative consequences associated with cannabis use. Despite this possibility, no longitudinal studies have examined whether female cannabis users are more likely to report later conduct problems compared to male cannabis users.

1.1. Current Study

The current study examined longitudinal associations between conduct problems and cannabis use in a predominantly Hispanic sample of adolescents followed over a two-year period. Prior studies using this same cohort have found evidence consistent with bidirectional associations between conduct problems and cannabis use (Hawes et al., 2019; Hawes, Pacheco-Colon et al., 2020). In the current study, we extend these findings by examining whether sex moderates these associations. We first hypothesized reciprocal relations between our two main outcomes, such that (a) baseline conduct problems would predict increases in cannabis use, and (b) baseline cannabis use would predict increases in conduct problems. However, because conduct problems often begin earlier than substance use problems (Kessler & Wang, 2008), we expected a stronger association between conduct problems and subsequent cannabis use. We also hypothesized that sex would moderate these associations. Given earlier onset of conduct problems among males (Chen et al., 2015) and that that there appears to be a stronger genetic influence between conduct problems and cannabis use among males (Verweij et al., 2016), we hypothesized that the association between baseline conduct problems and increases in cannabis use would be stronger for males. In contrast, we hypothesized that the association between baseline cannabis use and increases in conduct problems would be stronger for females based on preliminary evidence that females may experience more maladaptive consequences after cannabis use compared to males (Crane et al., 2013; McQueeny et al., 2011).

2. Materials and Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were 401 adolescents (46% female) taking part in a longitudinal investigation in the greater Miami metropolitan area (PI: RG, R01 DA033156) examining the associations between neurocognitive functioning and escalation in cannabis use over time (Duperrouzel et al., 2019; Pacheco-Colón et al., 2021). Recruitment occurred within middle and high schools throughout the city, and via flyers and word of mouth. Adolescents were between the ages of 14 and 17 at baseline (Mage = 15.40, SD = 0.72) and were predominately Hispanic (90%). By design, inclusion and exclusion criteria was chosen to maximize the risk of youth escalating in their cannabis use (Pacheco-Colón et al., 2021). The majority of the sample (90%) had used alcohol, cigarettes, cannabis, or other drugs at least once prior to study enrollment, 79% of the overall sample had tried cannabis, and 41% reported using cannabis regularly (i.e., once a week for at least three consecutive months) at some point prior to baseline, which resulted in various cannabis use trajectories (Hawes et al., 2019). However, to protect confidentiality regarding adolescents’ substance use status, a small subset of the sample (10%) had not used any substances at baseline. Thus, enrollment in the study did not automatically identify youth as substance using. Inclusion criteria also consisted of having the ability to read and write in English and being between the ages of 14 and 17. In order to avoid enrolling participants at baseline who already had cannabis use disorders, the Substance Dependence Severity Scale (Miele et al., 2000) was used to exclude those with high likelihood of meeting criteria for a cannabis use, alcohol use, or other substance use disorder. Participants were also excluded at baseline for frequent or recent use of drugs other than alcohol, cannabis, or nicotine. Participants were also excluded if they self-reported developmental disorders, significant birth complications, history of significant mood or thought disorders, traumatic brain injury, or a neurological disorder. Individuals with ADHD were not excluded from the study. Emergence of any of the aforementioned at subsequent measurement waves were not grounds for exclusion.

2.2. Procedure

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Florida International University. Adolescent assent and parental consent were obtained prior to each participant assessment and/or participant’s parent/guardian, depending upon whether the participant was 18 at the time of the assessment. Youth received monetary compensation for their participation.

Data were collected during five assessments conducted at 6-month intervals over a two-year period. Youth participated in three in-person assessments at baseline, one-year follow-up, and two-year follow-up, and two telephone assessments at the 6-month follow-up and 18-month follow-up. Only data collected at in-person assessments, which included both conduct disorder and cannabis use measures, were included in the current study (i.e., baseline and the one- and two-year follow-ups), as adolescents did not report on conduct problems during the two intervening telephone assessments.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Demographics

To control for demographics, we included information on each participant’s age and sex.

2.3.2. Adolescent Psychopathology

The Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Version IV (CDISC-IV; Shaffer et al., 2000) was administered to assess self-reported conduct disorder symptoms. The CDISC-IV is a structured interview with standardized probes and follow-up questions to gather information on adolescents’ behavior, including aggression towards other people or animals, destruction of property, deceitfulness, and theft. The CDISC-IV has previously demonstrated strong reliability and construct validity (Malgady et al., 1992). In the current study, adolescents reported on the number of conduct problem symptoms they had experienced within the last year.

2.3.3. Substance Use

The DUHQ (Pacheco-Colón et al., 2021; Rippeth et al., 2004), a detailed semi-structured interview, was used to assess frequency and amount of use of 16 different drug classes during a participant’s lifetime, the past 6 months, and the past 30 days. For the current study, we used the number of days adolescents had used cannabis within the past six-month cannabis. We also controlled for the number of days adolescents had used alcohol and nicotine within the past 6-months.

2.4. Analytic Plan

Analyses were conducted using Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). We used full-information maximum likelihood to handle missing data and a robust estimator to account for non-normality (i.e., MLR). Due to the count nature of conduct problem symptoms and cannabis use, we used a negative binomial link function to account for overdispersion in the calculation of their standard errors (Raftery, 1995). Because Mplus does not compute variances for count variables (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012), unstandardized regression coefficients are reported.

We ran cross-lagged autoregressive path models to investigate longitudinal reciprocal relations between conduct problems and cannabis use across a two-year period. We evaluated the stability of the path coefficients across time by comparing unconstrained models that allowed coefficients to vary across waves with models that constrained the autoregressive and cross-lagged coefficients across waves. We compared models using the chi-square difference test based on log-likelihood values and scaling correction factors obtained with the MLR estimator. All study analyses controlled for age and sex, as well as the influence of baseline alcohol and tobacco use. For our second aim, we created interaction terms to test whether the relations between conduct problems and cannabis use differed as a function of sex. We used simple slope difference tests to follow up on all significant interactions.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Means and correlations among variables at baseline and the final wave (i.e., the two-year follow-up) are reported in Table 1. Conduct problems and cannabis use were moderately correlated at baseline (r = .36) and at the two-year follow-up (r = .34). The correlation between conduct problems and cannabis use was stronger among females than among males at the two-year follow-up (r = .57 and .19, for females and males, respectively). No statistical differences in these correlations were found at baseline. We also found significant sex differences in the overall means, with males reporting more conduct problems (ds = .65 and .73,) and cannabis use (ds = .26 and .56) than females at baseline and at the two-year follow-up, respectively.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations at Baseline (Below Diagonal) and Two-Year Follow-up (Above Diagonal)

| Correlations | CP | CU | Alcohol | Nicotine | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| CP | - | .34*** | .16** | .29*** | .08 |

| CU | .36*** | - | .20*** | .26*** | .13** |

| Alcohol | .13* | .23*** | - | .17** | .12* |

| Nicotine | .18*** | .20*** | .11* | - | .12* |

| Age | .13** | .16** | .07 | .06 | - |

| Baseline Means (SD) | |||||

| Males | 6.01 (3.74) | 32.79 (48.23) | 4.64 (8.99) | 5.24 (19.71) | 15.47 (0.71) |

| Females | 3.73 (3.19) | 21.17 (41.18) | 5.39 (9.57) | 2.52 (14.43) | 15.33 (0.73) |

| Cohen’s d | 0.65*** | 0.26* | −0.08 | 0.16 | 0.18 |

| 95% CI | 0.45 – 0.85 | 0.06 – 0.46 | −0.28 – 0.12 | −0.04 – 0.35 | 0.02 – 0.38 |

| 2YFU Means (SD) | |||||

| Males | 5.63 (4.07) | 68.38 (70.35) | 10.12 (14.55) | 5.24 (19.71) | 17.45 (0.72) |

| Females | 3.02 (2.88) | 33.32 (52.32) | 11.11 (15.11) | 6.08 (23.11) | 17.32 (0.73) |

| Cohen’s d | .73*** | .56*** | −0.07 | 0.30** | 0.17 |

| 95% CI | .52 – .94 | .35 – .76 | −0.27 – 0.13 | 0.10 – 0.51 | −0.03 – 0.37 |

Note. N = 401. CP = Conduct problems. CU = Cannabis use. CI = Confidence interval. SD = Standard Deviation. 2YFU = Two-Year Follow-Up. Females serve as the reference group for Cohen’s d coefficients.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

3.2. Main Effects

Main effects are shown in Table 2. A chi-square difference test based on the log-likelihood indicated that coefficients could be constrained across time (χ 2[12] = 8.57, p = .739). Therefore, unstandardized coefficients were constrained to be equal across the baseline to the one-year follow-up path and the one-year follow-up to the two-year follow-up path. Overall, we found support for bidirectional associations, such that conduct problems significantly predicted changes in cannabis use (B = .100, p < .001), and cannabis use predicted increases in conduct problems (B = 0.001, p < .001), controlling for demographics, covariates, and prior frequencies. In contrast to our hypothesis, results indicated that their association did not significantly differ across directions (p = .489). That is, we did not find a stronger association between conduct problems and later cannabis use compared to the association between cannabis use and later conduct problems.

Table 2:

Unstandardized Regression Coefficients for Main and Interaction Effects Predicting Cannabis Use and Conduct Problems

| Predictors | Cannabis Use at Follow-Up |

||

| Step 1 | B | SE | p |

| Conduct Problems | 0.100 | 0.020 | < .001 |

| Cannabis Use | 0.014 | 0.001 | < .001 |

| Alcohol | 0.013 | 0.005 | .004 |

| Nicotine | 0.002 | 0.002 | .263 |

| Age | 0.191 | 0.097 | .049 |

| Sex | 0.355 | 0.130 | .006 |

| Step 2 | |||

| Conduct Problems | 0.131 | 0.039 | .001 |

| Cannabis Use | 0.014 | 0.001 | < .001 |

| Alcohol | 0.014 | 0.005 | .003 |

| Nicotine | 0.002 | 0.002 | .310 |

| Age | 0.208 | 0.101 | .041 |

| Sex | 0.575 | 0.255 | .024 |

| Conduct Problems x Sex | −0.050 | 0.044 | .253 |

| Conduct Problems at Follow-Up |

|||

| Step 1 | B | SE | p |

| Cannabis Use | 0.001 | 0.000 | < .001 |

| Conduct Problems | 0.136 | 0.007 | < .001 |

| Alcohol | 0.001 | 0.002 | .490 |

| Nicotine | 0.000 | 0.001 | .919 |

| Age | 0.021 | 0.033 | .519 |

| Sex | 0.238 | 0.049 | < .001 |

| Step 2 | |||

| Cannabis Use | 0.003 | 0.001 | < .001 |

| Conduct Problems | 0.136 | 0.007 | < .001 |

| Alcohol | 0.001 | 0.002 | .513 |

| Nicotine | 0.000 | 0.001 | .818 |

| Age | 0.022 | 0.033 | .512 |

| Sex | 0.358 | 0.064 | < .001 |

| Cannabis Use x Sex | −0.003 | 0.001 | .001 |

Note. N = 401. Unstandardized coefficients were constrained to be equal across time. Bolded results indicate significant path coefficients at p < .05. Sex was dummy coded with female as reference.

3.3. Sex Differences

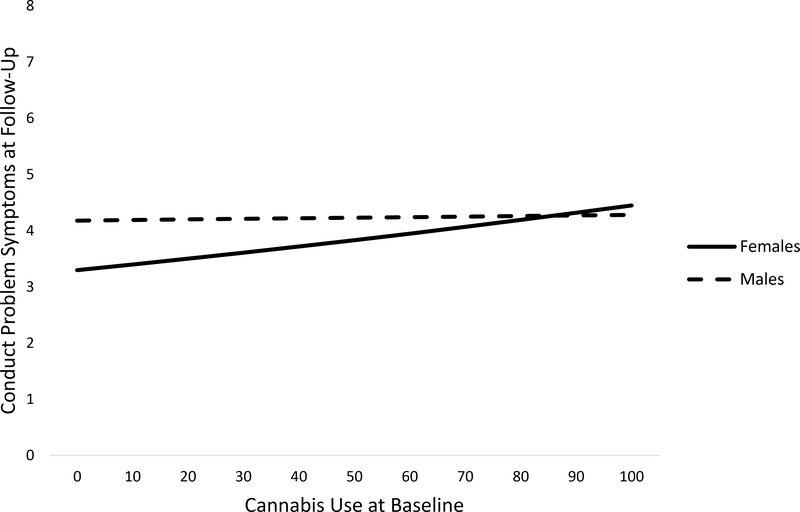

Interaction effects are shown in Table 2. Similar to the main effects model, a log-likelihood ratio test indicated that coefficients, including the interaction effects, could be constrained across time (χ 2[2] = 1.13, p = .569).The interaction between conduct problems and sex did not significantly predict changes in cannabis use (p = .253). In contrast, the interaction between cannabis use and sex significantly predicted change in conduct problems (B = −0.003, p = .001). Simple slope difference tests revealed that there was a significant, positive association between cannabis use and increases in conduct problems among females but not males (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Simple slopes of the effects of cannabis use on conduct problems by sex. Covariates are included in the model but not represented in the figure. Solid line represents significant slope (p < .05).

3.4. Post-Hoc Analyses

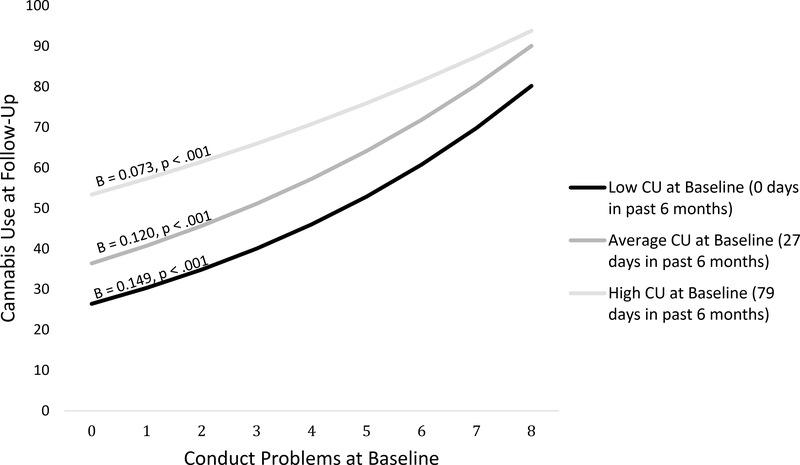

Although not an original aim of the current study, we hypothesized a posteriori that the oversampling of youth who had previously used cannabis prior to baseline may have attenuated the association between conduct problems and later frequency of cannabis use. Therefore, we followed up with a post-hoc analysis to determine whether the association between conduct problems and cannabis use was dependent upon adolescents’ baseline frequencies of cannabis use (See Table 3). A chi-square difference test based on the log-likelihood indicated that the interaction term could be constrained across time (χ 2[1] = 2.12, p = .145). The interaction between baseline cannabis use and baseline conduct problems significantly predicted cannabis use across time (p < .001). Simple slope difference tests revealed that the association between baseline conduct problems and later cannabis use was strongest among those who had not used cannabis within the six months prior to baseline and weakest at high levels (72.96 days) of baseline frequencies of cannabis use (see Figure 2).

Table 3:

Unstandardized Regression Coefficients for Interaction Effect of Cannabis Use and Conduct Problems at Baseline on Cannabis Use at Follow-Up

| Cannabis Use at Follow-Up |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | B | SE | p |

| Conduct Problems | 0.120 | 0.024 | < .001 |

| Cannabis Use | 0.018 | 0.002 | < .001 |

| Alcohol | 0.013 | 0.005 | .009 |

| Nicotine | 0.002 | 0.002 | .132 |

| Age | 0.215 | 0.102 | .035 |

| Sex | 0.319 | 0.134 | .018 |

| Conduct Problems x Cannabis Use | -0.001 | 0.000 | < .001 |

Note. N = 393. Unstandardized coefficients were constrained to be equal across time. Bolded results indicate significant path coefficients at p < .05. Sex was dummy coded with female as reference.

Figure 2.

Simple slopes of the effects of conduct problems on cannabis use at different levels of cannabis use at baseline. CU = Cannabis Use. Covariates are included in the model but not represented in the figure.

4. Discussion

The current study examined sex differences in bidirectional associations between conduct problems and cannabis use among a predominantly Hispanic sample of adolescents at risk for escalating cannabis use. Consistent with our first hypothesis and prior findings in our lab (Hawes et al., 2019; Hawes, Pacheco-Colón et al., 2020), we found support for bidirectional associations between conduct problems and cannabis use across a two-year period, controlling for prior frequencies, demographics, and confounding influences. In contrast to our hypothesis, the strength of these associations did not differ. Post-hoc analyses revealed that the association between conduct problems and later cannabis use was dependent upon baseline cannabis use frequency. Finally, analyses examining sex differences revealed mixed findings. As predicted, the association between baseline cannabis use and changes in conduct problems was significant among females but not males. In contrast, sex did not influence the association between baseline conduct problems and subsequent frequency of cannabis use.

Few longitudinal studies have examined the association between cannabis use and changes in conduct problems across adolescence. This is most likely due to age of onset for conduct problems being much earlier on average than age of onset for substance use problems (Kessler & Wang, 2008). However, gaining a better understanding of the adverse effects of cannabis use within adolescence remains critical, particularly with regards to the onset and course of comorbid mental health problems. Within the current study, we found a significant association between cannabis use and changes in conduct problems, even after accounting for baseline conduct problems. These results underscore the importance of viewing cannabis use as a risk factor for maladjustment rather than solely as a consequence. Treatment programs aimed to prevent and reduce behavior problems should include a component to address earlier and concurrent cannabis use.

Our findings are inconsistent with at least one other longitudinal study, which did not find a significant association between cannabis use and changes in conduct problems across adolescence (Defoe et al., 2018). Notably, the participant sample used in the current study consisted of adolescents who had, for the most part, already initiated substance use (i.e., nicotine, cannabis, alcohol) at baseline. In contrast, Defoe and colleagues’ sample had very low substance use at baseline. Thus, earlier initiation of substances may be a particularly salient risk factor for later conduct problems and could potentially account for the differences across studies. We recommend additional follow-up studies that prospectively examine age at cannabis use initiation as a moderator of the relations between cannabis use and changes in conduct problems across adolescence to further understand the inconsistencies across studies. This is particularly salient given the increasing availability of cannabis and declining perception that cannabis is harmful among adolescents (Johnston et al., 2016), which may lead to earlier age of initiation over time. The ongoing Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study (Garavan et al., 2018), which follows over 11,000 9- to 10-year-olds across a ten-year period, will provide an optimal opportunity to carry out such analyses.

Although not an original aim of the study, we found that the association between baseline conduct problems and later cannabis use was strongest among those who had not used cannabis at baseline, and that the association was attenuated at higher frequencies of baseline cannabis use. This may be due to ceiling effects; that is, adolescents who reported higher frequencies of cannabis use at baseline had less variability in their use over time. Nonetheless, these findings highlight the importance of interpreting one’s findings in the context of sample characteristics. Additionally, service providers should continue to assess for substance use on an ongoing basis among youth who present with conduct problems, as cannabis use may escalate more quickly among those who reported no, or infrequent use, at intake.

4.1. Sex Differences

Our findings suggest that there is a significant, positive association between frequency of cannabis use at baseline and changes in conduct problems among females but not males. There is some evidence to suggest sex differences in the neuropsychological and pharmacological effects of cannabis use, such as accelerated progression of a CUD among females compared to males (Crane et al., 2013). By definition, to meet criteria for CUD, one must experience negative consequences associated with chronic use. Our findings provide insight into some of the negative consequences that may put females at greater risk for a CUD, as our results suggest that female cannabis users are at greater risk of later conduct problems compared to males. However, because we are not aware of any other studies that have examined sex differences in these associations, our findings should be replicated with other samples.

The associations between cannabis use and later conduct problems among females may be driven, in part, by environmental factors. Prior research has indicated that environmental influences appear to be a stronger factor in explaining the link between conduct problems and cannabis use among adolescent females (Verweij et al., 2016), although the directionality of the association was not previously examined. Multiple systematic reviews have identified several unique risk factors related to conduct problems among females, such as childhood adversity, internalizing symptoms, and poor relationship quality (Hubbard & Pratt, 2002; Wong et al., 2010). Experiencing these risk factors may set about a cascading chain events among female adolescents, such as the initiation of cannabis and subsequent increases in conduct problems. For example, poor relationship quality during early adolescence may increase females’ risk for using cannabis, leading to increased exposure to delinquent peers and ultimately, increases in conduct problems. However, this has yet to be empirically tested as a function of sex. The examination of these environmental factors as potential moderators or mediators could further elucidate our understanding of sex-specific temporal sequencing of comorbid cannabis use and conduct problems among adolescents.

4.2. Limitations

Our findings must be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, our specific inclusion/exclusion criteria focused on recruiting a cohort of adolescents who were likely to escalate in their cannabis use over time. Although this provided us with additional power to detect associations between conduct problems and changes in cannabis use, our findings may not generalize to other community samples. Instead, our study could be generalized to early to mid-adolescent populations who engage in at least some substance use. Nonetheless, our sample reported somewhat limited histories of cannabis use due to their young age, and results could differ for older samples with more chronic, heavy cannabis use. Additionally, our sample was predominantly White (76.8%) of Hispanic ethnicity (89.8%), consistent with the demographic makeup of the greater Miami metropolitan area. A small percentage of youth (<5%) were screened out of the original outcome study for reports of significant depression or anxiety, as indicated by receiving treatment for that diagnosis (i.e., medication or therapy). Although resulting in only a small percentage of the overall sample, this decision may have affected our results given high rates of comorbid internalizing symptoms with conduct problems (Polier et al., 2012) and substance use (Roberts et al., 2007). Finally, we were unable to examine whether specific conduct problem symptoms were directly associated with cannabis use, such as stealing money to buy cannabis or cutting class to use cannabis. Given the link between conduct problems and cannabis use, it would be informative to examine whether there is a stronger link between specific conduct problem symptoms and cannabis use.

4.3. Conclusion

The results presented here highlight the bidirectional associations between conduct problems and cannabis use among adolescents and how these paths differ between males and females. Overall, our findings have important implications for furthering our understanding of the etiology of conduct problems and cannabis use in youth. Knowledge on which symptoms precede others, and for whom, can guide the selection of individualized prevention and intervention programs for referred youth. Further work is needed to better understand sex differences underlying the directionality of these associations across the lifespan, including the examination of environmental influences as potential moderators or mediators of our findings.

Highlights.

Bidirectional associations found between conduct problems and cannabis use among a predominantly Hispanic sample of adolescents

Association between conduct problems and later cannabis use strongest among cannabis-naïve at baseline

Cannabis use associated with later conduct problems among females but not males

Sex did not moderate associations between conduct problems and later cannabis use

Findings have important implications for our understanding of the etiology of conduct problems and cannabis use in youth

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by R01 DA031176, F31 DA047750-01A1, and 5T32DA043449-02 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bevilacqua L, Hale D, Barker ED, & Viner R (2018). Conduct problems trajectories and psychosocial outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27(10), 1239–1260. 10.1007/s00787-017-1053-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ (2020). Modeling the comorbidity of cannabis abuse and conduct disorder/conduct problems from a cognitive neuroscience perspective. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 16(1), 3–21. 10.1080/15504263.2019.1668099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Zhang CS, & Brook DW (2011). Antisocial behavior at age 37: Developmental trajectories of marijuana use extending from adolescence to adulthood. American Journal on Addictions, 20(6), 509–515. 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calakos KC, Bhatt S, Foster DW, & Cosgrove KP (2017). Mechanisms underlying sex differences in cannabis use. Current Addiction Reports, 4(4), 439–453. 10.1007/s40429-017-0174-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Drabick DAG, & Burgers DE (2015). A Developmental Perspective on Peer Rejection, Deviant Peer Affiliation, and Conduct Problems Among Youth. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 46(6), 823. 10.1007/s10578-014-0522-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane NA, Schuster RM, Fusar-Poli P, & Gonzalez R (2013). Effects of cannabis on neurocognitive functioning: Recent advances, neurodevelopmental influences, and sex differences. Neuropsychol Rev, 23, 117–137. 10.1007/s11065-012-9222-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creemers HE, van Lier PA, Vollebergh WA, Ormel J, Verhulst FC, & Huizink AC (2009). Predicting onset of cannabis use in early adolescence: The interrelation between high-intensity pleasure and disruptive behavior. The TRAILS Study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs,70(6), 850–858. 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defoe IN, Khurana A, Betancourt LM, Hurt H, &Romer D (2018). Disentangling longitudinal relations between youth cannabis use, peer cannabis use, and conduct problems: Developmental cascading links to canna-bis use disorder. Addiction, 114(3), 458–493. 10.1111/add.14456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond G, Panichelli-Mindel SM, Shera D, Dennis M, Tims F, & Ungemack J (2006). Psychiatric syndromes in adolescents with marijuana abuse and dependency in outpatient treatment. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 15(4), 37–54. 10.1300/J029v15n04_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duperrouzel JC, Hawes SW, Lopez-Quintero C, Pacheco-Colón I, Coxe S, Hayes T, & Gonzalez R (2019). Adolescent cannabis use and its associations with decision-making and episodic memory: Preliminary results from a longitudinal study. Neuropsychology, 33(5), 701–710. 10.1037/neu0000538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garavan H, Bartsch H, Conway K, Decastro A, Goldstein RZ, Heeringa S, et al. (2018). Recruiting the ABCD sample: Design considerations and procedures. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 32, 16–22. 10.1016/j.dcn.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giedd JN, Raznahan A, Mills KL, & Lenroot RK (2012). Magnetic resonance imaging of male/female differences in human adolescent brain anatomy. Biology of Sex Differences, 3(1), 1–9. 10.1186/2042-6410-3-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KM, Musci RJ, Johnson RM, Matson PA, Reboussin BA, & Ialongo NS (2016). Outcomes associated with adolescent marijuana and alcohol use among urban young adults: A prospective study. Addictive Behaviors, 53, 155–160. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes SW, Pacheco-Colon I, Ross JM, & Gonzalez R (2020). Adolescent cannabis use and conduct problems: The mediating influence of callous-unemotional traits. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(3), 613–627. https://doi-org.ezproxy.fiu.edu/10.1007/s11469-018-9958-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes SW, Trucco EM, Duperrouzel JC, Coxe S, & Gonzalez R (2019). Developmental pathways of adolescent cannabis use: Risk factors, outcomes and sex-specific differences. Substance Use and Misuse, 54(2), 271–281. 10.1080/10826084.2018.1517177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawes SW, Waller R, Byrd AL, Bjork JM, Dick AS, Sutherland MT, Riedel MC, Tobia MJ, Thomson N, Laird AR, & Gonzalez R (2020). Reward processing in children with disruptive behavior disorders and callous-unemotional traits in the ABCD Study. American Journal of Psychiatry. Advanced online publication. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.19101092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron J, Barker ED, Joinson C, Lewis G, Hickman M, Munafo M, & Macleod J (2013). Childhood conduct disorder trajectories, prior risk factors and cannabis use at age 16: Birth cohort study. Addiction, 108(12), 2129–2138. 10.1111/add.12268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard DJ & Pratt TC (2002) A meta-analysis of the predictors of delinquency among females. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation 34(3), 1–13. 10.1300/J076v34n03_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jager G, Block RI, Luijten M, & Ramsey NF (2013). Tentative evidence for striatal hyperactivity in adolescent cannabis-using boys: A cross-sectional multicenter fMRI study. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 45(2), 156–167. 10.1080/02791072.2013.785837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Miech RA, Bachman JG, & Schulenberg JE (2016). Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2015: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph JE, Liu X, Jiang Y, Lynam D, & Kelly TH (2009). Neural correlates of emotional reactivity in sensation seeking. Psychological Science, 20(2), 215–223. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02283.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, & Wang PS (2008). The descriptive epidemiology of commonly occurring mental disorders in the United States. Annual Review of Public Health, 29, 115–129. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SS, Secades-Villa R, Okuda M, Wang S, Pérez-Fuentes G, Kerridge BT, & Blanco C (2013). Sex differences in cannabis use disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 130(1–3), 101–108. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ (1985). The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: Focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. The American journal of psychiatry, 142(11), 1259–1264. 10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malgady RG, Rogler LH, & Tryon WW (1992). Issues of validity in the Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 26(1), 59–67. 10.1016/0022-3956(92)90016-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQueeny T, Padula CB, Price J, Medina KL, Logan P, & Tapert SF (2011). Gender effects on amygdala morphometry in adolescent marijuana users. Behavioural Brain Research, 224(1), 128–134. 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.05.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miele GM, Carpenter KM, Smith Cockerham M, Trautman KD, Blaine J, & Hasin DS (2000). Substance Dependence Severity Scale (SDSS): Reliability and validity of a clinician-administered interview for DSM-IV substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 59(1), 63–75. 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00111-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles DR, van den Bree MB, & Pickens RW (2002). Sex differences in shared genetic and environmental influences between conduct disorder symptoms and marijuana use in adolescents. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 114(2), 159–168. 10.1002/ajmg.10187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt T, Caspi A, Rutter M, & Silva P (2001). Sex and comorbidity: Are there sex differences in the co-occurrence of conduct disorder and other disorders? In Moffit T, Caspi A, Rutter M, & Silva P (Eds.), Sex Differences in Antisocial Behaviour: Conduct Disorder, Delinquency, and Violence in the Dunedin Longitudinal Study (pp. 135–150). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511490057.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide (Seventh ed.). Los Angeles Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco‐Colón I, Lopez‐Quintero C, Coxe S, Limia JM, Pulido W, Granja,., … & Gonzalez R (2021). Risky Decision‐Making as an Antecedent or Consequence of Adolescent Cannabis Use Findings from a Two‐Year Longitudinal Study. Addiction. Advance online publication. 10.1111/add.15626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini D, Bechtold J, Loeber R, & White H (2015). Developmental trajectories of marijuana use among men examining linkages with criminal behavior and psychopathic features into the mid-30s. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 52(6), 797–828. 10.1177/0022427815589816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polier G, Vloet T, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Laurens K, & Hodgins S (2012). Comorbidity of conduct disorder symptoms and internalising problems in children: Investigating a community and a clinical sample. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 21(1), 31–38. 10.1007/s00787-011-0229-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftery AE (1995). Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociological Methodology, 25, 111–164. 10.2307/271063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rippeth JD, Heaton RK, Carey CL, Marcotte TD, Moore DJ, Gonzalez R, Wolfson T, Grant I, & the HNRC Group. (2004). Methamphetamine dependence increases risk of neuropsychological impairment in HIV infected persons. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 10(1), 1–14. 10.1017/S1355617704101021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Roberts CR, & Xing Y (2007). Comorbidity of substance use disorders and other psychiatric disorders among adolescents: Evidence from an epidemiologic survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 88(S1), S4–S13. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, & Schwab-Stone ME (2000). NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(1), 28–38. 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verweij KJ, Creemers HE, Korhonen T, Latvala A, Dick DM, Rose RJ, Huizink AC, & Kaprio J (2016). Role of overlapping genetic and environmental factors in the relationship between early adolescent conduct problems and substance use in young adulthood. Addiction, 111(6), 1036–1045. doi: 10.1111/add.13303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong TML, Slotboom A-M, & Bijleveld CCJH (2010). Risk factors for delinquency in adolescent and young adult females: A European review. European Journal of Criminology, 7(4), 266–284. 10.1177/1477370810363374 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, & Schmidt NB (2003). Panic disorder and smoking. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(1), 29–51. 10.1093/clipsy.10.1.29 [DOI] [Google Scholar]