Abstract

Background:

Serious psychological distress (SPD) is common among adults who smoke cigarettes and among adults with substance use disorders (SUD). It is unknown whether the burden of SPD is even greater among individuals with both cigarette smoking and SUDs. This study examined the intersectionality of SPD, cigarette smoking, and SUD over time.

Methods:

Data came from annual, cross-sectional, nationally representative samples of the United States (US) National Survey on Drug Use and Health (individuals age 12+). Past-month SPD prevalences were estimated each year from 2008-2018 for adults age 18+ with current daily, current non-daily, former, and never cigarette smoking by SUD status (combined n=441,286). Logistic regression models examined linear time trends of SPD.

Results:

In 2018, SPD was significantly more prevalent among adults in each smoking group with SUD versus those without SUD (daily 29.1% vs. 9.0%, non-daily 23.2% vs. 8.6%, former 19.5% vs. 3.2%, never 16.4% vs. 4.3%). After adjusting for sociodemographics, SPD prevalence increased over time across smoking statuses with a larger change for persons with SUD (AOR=1.07; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.09) vs. no SUD (AOR=1.03; 95% CI: 1.02. 1.04).

Conclusions:

SPD was more than twice as common among adults with SUD who smoke cigarettes compared to those without SUD who do not smoke cigarettes, with the highest prevalence among adults with both SUD and daily smoking. While SPD has increased over time, differences depended on SUD status beyond the effect of cigarette smoking. These results provide further evidence for treating smoking and mental health problems together.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Tobacco Use, Substance Use Disorders, Serious Psychological Distress, Intersectionality

1. Introduction

Serious psychological distress (SPD), a proxy indicator of serious mental illness through the assessment of depression and anxiety symptoms (Kessler et al., 2002; Swartz and Jantz, 2014), is increasing in the United States (US) (McGinty et al., 2020; Zvolensky et al., 2018) and is associated with negative health consequences including premature mortality and chronic health conditions (Alhussain et al., 2017; Hamer et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2012; McGuire et al., 2009; Muhuri, 2013; Sung et al., 2011). Based on the increasing prevalence of mental health problems and negative consequences of poor mental health, it is critical to identify groups with higher prevalences of mental health problems that could be targeted with interventions. In 2018, 13.7% of US individuals (more than 34 million people) reported smoking cigarettes (Creamer, 2019) and 3% (more than 8 million people) reported substance use disorders (SUDs) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019).

Mental health problems are a significant contributor to the US and global burden of disease (Vos et al., 2017; Whiteford et al., 2013). Independently, research has found that SPD is more common among adults who smoke cigarettes versus those do not smoke cigarettes (McGinty et al., 2020; Zvolensky et al., 2018), with SPD becoming more common among smokers over time (Zvolensky et al., 2018), and that SPD is more common among adults with substance use disorders (SUDs), compared to adults without SUDs (Danielsson et al., 2016; Kelly et al., 2015; Lasser et al., 2000; Weinberger et al., 2017). While cigarette smoking has been decreasing over time (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services et al., 2020), the prevalence of SUDs has remained generally stable (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019). Cigarette smoking is highly comorbid with both SPD and SUD; it is of interest whether SPD is decreasing in conjunction with declines in cigarette smoking for persons with SUD and persons without SUD.

Researchers are increasing their focus on intersectionality, or how multiple vulnerabilities may intersect in their relationship to health behaviors and psychological symptoms (Higgins et al., 2015; López and Gadsden, 2016). Studies have separately shown that SPD is more common among people who smoke cigarettes and among people who have SUDs (Kessler et al., 2005). Further, because mental disorders, cigarette smoking, and SUD often co-occur, smoking and SUD might have a synergistic or multiplicative relationship with regard to SPD (Lasser et al., 2000; Weinberger et al., 2017; Zvolensky et al., 2018). However, to date, the intersectionality of cigarette smoking and SUD in relation to SPD (i.e., whether the prevalence of SPD is greater for those with both cigarette smoking and SUDs, compared with those with either or neither cigarette smoking or SUDs) has not yet been empirically examined.

This study examined the relationship of cigarette smoking and SUD in relation to SPD in US adults. The first aim was to estimate the prevalence of SPD in 2018 (i.e., the most recent data year) by both cigarette smoking and SUD status. We hypothesized that those with both smoking and SUD would report the highest prevalence of SPD compared to smoking alone, SUD alone, or neither smoking or SUD. The prevalence of SPD by smoking and SUD was examined overall and by sociodemographics (Dube et al., 2009; Kiviniemi et al., 2011). The second aim was to investigate time trends in SPD by cigarette smoking status, stratified by SUD status, from 2008 to 2018. We hypothesized that SPD would decrease over time and that those declines in SPD would be less prominent for persons with SUD compared to those without SUD.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source & Sample

Data came from annual, cross-sectional, nationally representative samples of the US National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH; individuals age 12+). The NSDUH has multiple modules on health and drug use, and employs multistage probability sampling and audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2018). The current analyses included adults age 18+ who reported current daily, current non-daily, former, and never cigarette smoking (total sample 2018 n=42,963, total sample 2008-2018 combined n=441,286).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcome: Serious Psychological Distress (SPD)

Past-month SPD was measured using the 6-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6). The K6 measures nonspecific psychological distress and has shown high sensitivity and specificity for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-4th edition (DSM-IV) diagnoses of serious mental illness other than SUD (e.g., mood, anxiety, psychotic disorders) (Kessler et al., 2002). In six questions, adult respondents were asked how often they experienced symptoms of psychological distress during the past 30 days (i.e., feeling nervous, hopeless, restless or fidgety, so sad or depressed that nothing could cheer you up, that everything was an effort, and feeling down on yourself, no good, or worthless). Each question was scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0=none of the time and 4=all the time); total scores of ≥13 were considered positive for SPD (Streck et al., 2020).

2.2.2. Exposure: Cigarette Smoking

Four cigarette smoking status groups were included in these analyses: never smoking, former smoking, current daily smoking, and current nondaily smoking. Lifetime smoking was defined as smoking ≥100 lifetime cigarettes and never smoking was defined as smoking <100 lifetime cigarettes consistent with the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention’s definitions (Creamer, 2019). For respondents with lifetime cigarette use, current smoking was classified as smoking ≥1 cigarette in the past month and former smoking was classified as not smoking any cigarettes in the past 12 months. Respondents who smoked within the past 12 months, but <1cigarette in the past month were included in the never smoking group. For respondents with current smoking, daily smoking was defined as smoking 30 days in the past month; non-daily smoking was defined as smoking cigarettes less than 30 days in the past month consistent with past literature (e.g., Parker and Weinberger, 2020; Zvolensky et al., 2018). The median number of cigarettes per day for persons with daily smoking was 10.5 and non-daily smoking was 3.5.

2.2.3. Moderator: Substance Use Disorder

Respondents were classified as having a past-year SUD if they met criteria for one or more SUDs (i.e., substance abuse and/or dependence) assessed according to DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The NSDUH assesses SUDs for cannabis, hallucinogens, inhalants, methamphetamine, tranquilizers, cocaine, heroin, prescription pain relievers, simulants, sedatives, and alcohol. Respondents with no past-year SUDs were classified as not having SUDs.

2.2.4. Sociodemographics

Sociodemographics included: sex (male/female), age (18-25 years, 26-34 years, 35-49, 50+ years), race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic (NH) White, NH Black, Hispanic, NH Other [NH Native American/Alaskan Native, NH Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, NH Asian, NH more than one race]), annual income (<$20,000, $20,000-$49,999, $50,000-$74,999, ≥$75,000), and marital status (married, widowed/divorced/separated, never married).

2.2.5. Statistical Analyses

For Aim 1, past-month SPD prevalence in 2018 was estimated for individuals with current daily, current non-daily, former, and never cigarette smoking by SUD status (SUD, No SUD) for the overall sample and by sociodemographic subgroups. For Aim 2, logistic regression models tested the association between cigarette smoking status and past-month SPD from 2008-2018. Additional logistic regression models examined linear time trends of SPD with 1) continuous year as the predictor that were stratified by SUD status (presence vs. absence) and 2) a two-way interaction between year and SUD status adjusted by cigarette status. Models with year-by-cigarette smoking status assessed differential time trends among smoking statuses, stratified by SUD status. Finally, in postestimation exploratory analysis, a three-way interaction was estimated to test whether the rapidity of SPD changes over time differed by cigarette smoking and/or SUD status. These analyses began with unadjusted models followed by models that adjusted for sociodemographics found in Table 1; they were conducted in Stata version 16 to account for complex sampling (Stata Corp, 2019).

Table 1.

Prevalence of serious psychological distressa by cigarette smoking status and substance use disorders (SUD; weighted %, standard error).b Data from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (adults age 18+, n=42,963).

| Never cigarette smoking (n = 28,108) |

Former cigarette smoking (n = 6,703) |

Non-daily cigarette smoking (n = 3,195) |

Daily cigarette smoking (n = 4,957) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUD | No-SUD | SUD | No-SUD | SUD | No-SUD | SUD | No-SUD | |

| Total sample | 16.4 (1.1) | 4.3 (0.1) | 19.5 (2.0) | 3.2 (0.3) | 23.2 (2.0) | 8.6 (0.9) | 29.1 (2.3) | 9.0 (0.7) |

| Sex/Gender | ||||||||

| Female | 24.9 (2.3) | 4.8 (0.2) | 29.4 (4.2) | 4.5 (0.5) | 17.5 (2.2) | 11.9 (1.3) | 35.0 (3.8) | 11.8 (1.1) |

| Male | 10.3 (1.1) | 3.7 (0.2) | 15.2 (2.3) | 2.2 (0.3) | 33.9 (4.3) | 5.9 (1.1) | 25.9 (2.8) | 6.1 (0.6) |

| Age, years | ||||||||

| 18-24 | 23.0 (1.4) | 11.0 (0.4) | 25.2 (4.3) | 12.8 (1.4) | 30.4 (2.4) | 16.5 (2.0) | 35.6 (3.7) | 15.1 (1.8) |

| 25-34 | 16.4 (2.7) | 4.7 (0.3) | 20.2 (4.1) | 5.6 (0.7) | 25.0 (4.4) | 8.9 (1.6) | 32.8 (3.8) | 14.1 (1.4) |

| 35-49 | 11.3 (2.4) | 3.2 (0.3) | 20.0 (3.8) | 3.3 (0.5) | 15.4 (3.4) | 7.0 (1.1) | 29.7 (3.9) | 8.6 (0.9) |

| 50+ | 7.3 (3.1) | 2.3 (0.3) | 17.0 (4.0) | 2.5 (0.4) | 19.8 (6.2) | 6.7 (1.1) | 20.3 (5.8) | 6.1 (1.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 15.5 (1.4) | 4.2 (0.2) | 17.2 (2.6) | 3.3 (0.3) | 23.5 (2.5) | 10.5 (1.4) | 29.6 (2.6) | 9.0 (0.8) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 21.6 (3.4) | 4.5 (0.4) | 31.0 (12.0) | 2.2 (0.8) | 22.7 (5.0) | 6.0 (1.6) | 21.0 (6.0) | 8.0 (1.9) |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 16.6 (3.8) | 4.2 (0.6) | 19.1 (7.0) | 1.7 (0.7) | 18.1 (5.3) | 7.7 (2.4) | 29.8 (6.9) | 7.0 (1.8) |

| Hispanic | 15.7 (2.8) | 4.8 (0.3) | 25.3 (7.0) | 4.1 (0.9) | 24.9 (5.5) | 4.8 (1.2) | 32.5 (7.1) | 11.7 (2.1) |

| Annual Income | ||||||||

| <$20,000 | 24.6 (3.0) | 7.8 (0.5) | 29.3 (8.6) | 8.3 (1.2) | 31.5 (4.2) | 11.8 (2.0) | 32.1 (4.0) | 16.7 (2.0) |

| $20,000-$49,999 | 20.7 (2.4) | 5.0 (0.3) | 28.7 (4.6) | 3.2 (0.4) | 28.8 (5.1) | 7.9 (1.4) | 30.5 (3.5) | 8.4 (1.0) |

| $50,000-$74,999 | 15.7 (2.6) | 3.7 (0.4) | 14.3 (6.0) | 3.3 (0.8) | 17.5 (4.6) | 7.4 (1.9) | 28.7 (6.9) | 5.4 (1.2) |

| $75,000+ | 9.8 (1.3) | 2.9 (0.2) | 13.2 (3.2) | 2.0 (0.4) | 14.0 (2.8) | 6.8 (1.3) | 22.9 (3.6) | 5.3 (0.8) |

| Marital Status | ||||||||

| Married | 15.9 (2.7) | 28.3 (1.9) | 12.1 (3.4) | 2.2 (0.4) | 8.1 (2.1) | 5.5 (1.3) | 25.0 (4.0) | 7.3 (1.0) |

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 12.1 (3.0) | 12.5 (1.5) | 27.6 (5.8) | 4.2 (0.7) | 28.5 (5.0) | 9.6 (1.9) | 27.3 (5.5) | 8.9 (1.2) |

| Never married | 71.9 (3.8) | 59.1 (2.2) | 23.5 (3.2) | 6.1 (1.0) | 27.7 (2.8) | 10.7 (1.3) | 32.0 (3.1) | 11.6 (1.2) |

Serious Psychological Distress was assessed using the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6) screening instrument and defined as a score of 13 or higher.

Percentages may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

3. Results

In 2018, SPD was significantly more prevalent among persons with vs. without SUD among those with daily (29.1% vs. 9.0%), non-daily (23.2% vs. 8.6%), former (19.5% vs. 3.2%), and never (16.4% vs. 4.3%) cigarette smoking (p-values<0.001) (Table 1). Generally, SPD was greater in adults with SUD versus no SUD overall (21.1% vs. 4.8%; p<0.001) and across most sociodemographics (Table 1). That is, SPD was more than twice as prevalent among persons with SUD compared to persons without SUD for all cigarette smoking statuses. Patterns also demonstrated that SPD was highest for persons with current smoking (daily or non-daily) compared to persons with former or never smoking (p-value<0.001) (Table 1).

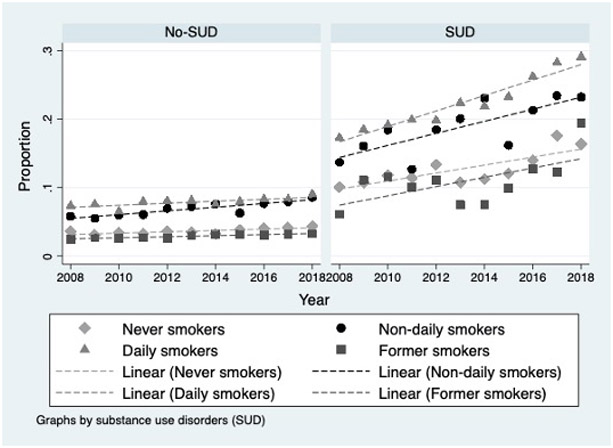

In adjusted models, across all cigarette smoking statuses, the prevalences of SPD significantly increased between 2008 and 2018 for all adults, especially those with SUD (AOR=1.07; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.09; adults with no SUD AOR=1.03; 95% CI: 1.02, 1.04). Increases in SPD over time were higher for those with SUD versus no SUD (p-value<0.001). SPD prevalence increased over time for those with both SUD and daily smoking (AOR=1.08; 95% CI: 1.06, 1.11) and SUD and non-daily smoking (AOR=1.07; 95% CI: 1.05, 1.10), as well as those with SUD and either former smoking (AOR=1.08; 95% CI: 1.04, 1.12) or never smoking (AOR=1.06; 95% CI: 1.04, 1.09). The increase in SPD over time was more rapid among those with non-daily smoking than daily smoking for persons without SUD (p-value=0.05), but not for those with SUD (p-value=0.79; Figure 1). In the three-way interaction models, increases in SPD over time were not significantly different for persons by cigarette smoking and SUD status (p-value=0.52). Still, in the two-way interaction, SPD estimates for persons with SUD were significantly different than those for those with no SUD (p-value<0.001), beyond the effect of cigarette status.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of serious psychological distress by cigarette smoking status, stratified by substance use disorders from 2008 to 2018. Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (adults age 18+, n=441,286).

4. Discussion

SPD varied significantly by SUD status and cigarette smoking status such that SPD was between three and five times higher for those with SUD compared to those without SUD across all smoking statuses. These patterns were found for the full sample as well as nearly every sex, age, race/ethnicity, income, and marital status subgroup. While SPD increased from 2008 to 2018 among US adults, the prevalence of SPD was highest for those with SUD and daily cigarette smoking with a quarter or more these adults reporting SPD. SPD increased over time for all smoking statuses. Increases in SPD over time were higher for persons with SUD than persons without SUD. For those without SUD, the fastest increases in SPD prevalence across years were observed among those with non-daily smoking compared to daily smoking.

These results extend our knowledge from the limited prior studies of SPD and cigarette smoking. There has been an increase in the proportion of people who smoke who use cigarettes on a non-daily basis (Hassmiller et al., 2003) and non-daily smoking is increasing among people with mental health and substance use in the US (Weinberger et al., 2018). A prior report evaluating SPD by smoking status over a 6-year period in the US found that the increase in SPD over time was more rapid among persons with non-daily smoking than daily smoking (Zvolensky et al., 2018); we found this to be the case only among persons without SUD.

Our findings also suggest more elevated SPD among smokers versus non-smokers, consistent with studies conducted among adults, pregnant individuals, and members of the LGBTQ+ community (Leung et al., 2011; Sivadon et al., 2014; Varescon et al., 2013), and that SPD increased across survey years with greater increases among those with SUDs. The prevalence of SPD being significantly higher among people with vs without SUD is consistent with two cohort studies which have demonstrated a unidirectional relationship between SUD and SPD, including risk for long term psychological distress (Danielsson et al., 2016; Green et al., 2012). While there are correlates of SPD (e.g., health and medical co-morbidities; (Weissman et al., 2015)) and environmental factors (e.g., increases in stress over time; (American Psychological Association, 2019)) that may play a role in increasing SPD, the reasons for the increase in SPD over time, and higher prevalence of SPD among those with SUD are still not clear and an important area for future research. This study also extends previous work to examine the intersection of SPD, cigarette smoking, and SUD over an 11-year period. Adding more recent years, we found that SUD is driving the differences in SPD over time for all smoking statuses. In other words, increases over time were similar for daily and non-daily smokers compared to former or never smokers within each SUD category (i.e., SUD vs. non-SUD), but different between each SUD category. These findings suggest the benefits of continuing to examine the relationship of multiple risk factors in relation to mental health variables like SPD to identify groups in most need of intervention efforts.

Among the strengths of this study is the generalizability of its findings, given that data are nationally representative of US adults. However, the NSDUH does not include some subgroups such as those in prisons, hospitals, and treatment centers and the relationship of cigarette smoking and SUD to SPD would need to be examined in these subgroups. Importantly, this was a cross-sectional rather than a longitudinal study, so results limit our knowledge regarding the timing and directionality of SPD, cigarette smoking, and SUD (e.g., changes in SPD following changes in cigarette and/or substance use). In addition, due to the data available, cigarette smoking and SPD were measured for the past month, while SUD was measured for the past year. It should also be noted that this study focused on cigarettes and did not examine other tobacco products that might be related to SPD (Weinberger et al., 2020).

Rapid increases in SPD among those with non-daily smoking but no SUD, and the highest prevalences of SPD existing among those with both cigarette smoking and SUD, may reflect an opportunity for targeted outreach to improve mental health. Since SPD, cigarette smoking, and SUD all confer increased risk of negative health consequences, it may be beneficial to target persons with mental health problems by addressing their cigarette smoking and SUD in mental health treatment. One way would be incorporating a broad psychiatric symptom assessment into cigarette smoking cessation or SUD treatment programs as SPD is associated with psychological diagnoses and is considered a proxy for serious mental illness (Kessler et al., 2010, 2003; Payton, 2009). Alternatively, when assessing and treating individuals for cigarette smoking and SUD, providers might also screen for psychiatric symptoms.

While SPD and SUD have been associated with poorer cigarette smoking quit ratios (Parker et al., 2020; Streck et al., 2020), those who use drugs (e.g., cannabis) and achieve smoking cessation evidence decreases in mental health symptoms (Hser et al., 2017). It will be useful to prospectively examine whether treatment for cigarette smoking and/or SUD leads to improvements in mental health outcomes or whether integrating mental health treatment into smoking cessation and SUD programs would improve mental health outcomes. Future research in clinical samples should explore whether treatments targeting serious mental illness have differential outcomes by demographic subgroups. Public health interventions to reduce the prevalence and consequences of SPD may benefit from targeting individuals who use of tobacco and other substances and integrating efforts into tobacco and substance use treatment settings.

In conclusion, SPD prevalence has increased over time, and adults with a comorbid SUD vs. no SUD exhibited the steepest increases after accounting for the effect of cigarette status. The highest prevalence of SPD was among persons with daily cigarette smoking and SUD, which indicates that disparities in SPD have not decreased and remain for persons with smoking, especially for those with SUD. Future studies that can more closely examine the reasons or mechanisms by which SPD is increasing in this population may help to provide targets for treatment and prevention.

HIGHLIGHTS.

We examined the intersectionality of SPD, cigarette smoking, and SUD for US adults.

SPD was more prevalent among adults in each smoking group with SUD vs without SUD.

SPD increased over time for all smoking statuses, especially individuals with SUD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alhussain K, Meraya AM, Sambamoorthi U, 2017. Serious Psychological Distress and Emergency Room Use among Adults with Multimorbidity in the United States. Psychiatry J 2017. 10.1155/2017/8565186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, 1994. DSM-IV: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition. ed. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association, 2019. Stress in America: Stress and Current Events, Stress in America™ Survey. American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2018. 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological summary and definitions. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Creamer MR, 2019. Tobacco Product Use and Cessation Indicators Among Adults — United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 68. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6845a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsson A-K, Lundin A, Allebeck P, Agardh E, 2016. Cannabis use and psychological distress: An 8-year prospective population-based study among Swedish men and women. Addictive Behaviors 59, 18–23. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Caraballo RS, Dhingra SS, Pearson WS, McClave AK, Strine TW, Berry JT, Mokdad AH, 2009. The relationship between smoking status and serious psychological distress: findings from the 2007 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Int J Public Health 54 Suppl 1, 68–74. 10.1007/s00038-009-0009-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green KM, Zebrak KA, Robertson JA, Fothergill KE, Ensminger ME, 2012. Interrelationship of Substance Use and Psychological Distress over the Life Course among a Cohort of Urban African Americans. Drug Alcohol Depend 123, 239–248. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer M, Chida Y, Molloy GJ, 2009. Psychological distress and cancer mortality. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 66, 255–258. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassmiller KM, Warner KE, Mendez D, Levy DT, Romano E, 2003. Nondaily smokers: who are they? Am J Public Health 93, 1321–1327. 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Kurti AN, Redner R, White TJ, Gaalema DE, Roberts ME, Doogan NJ, Tidey JW, Miller ME, Stanton CA, Henningfield JE, Atwood GS, 2015. A Literature Review on Prevalence of Gender Differences and Intersections with Other Vulnerabilities to Tobacco Use in the United States, 2004–2014. Prev Med 80, 89–100. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser Y-I, Mooney LJ, Huang D, Zhu Y, Tomko RL, McClure E, Chou C-P, Gray KM, 2017. Reductions in Cannabis Use Are Associated with Improvements in Anxiety, Depression, and Sleep Quality, But Not Quality of Life. J Subst Abuse Treat 81, 53–58. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BC, Rendina HJ, Vuolo M, Wells BE, Parsons JT, 2015. A Typology of Prescription Drug Misuse: A Latent Class Approach to Differences and Harms. Drug Alcohol Rev 34, 211–220. 10.1111/dar.12192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SLT, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM, 2002. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 32, 959–976. 10.1017/s0033291702006074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, Epstein JF, Gfroerer JC, Hiripi E, Howes MJ, Normand S-LT, Manderscheid RW, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM, 2003. Screening for Serious Mental Illness in the General Population. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60, 184–189. 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE, 2005. Prevalence, Severity, and Comorbidity of Twelve-month DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Arch Gen Psychiatry 62, 617–627. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Bromet E, Cuitan M, Furukawa TA, Gureje O, Hinkov H, Hu C-Y, Lara C, Lee S, Mneimneh Z, Myer L, Oakley-Browne M, Posada-Villa J, Sagar R, Viana MC, Zaslavsky AM, 2010. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) survey initiative. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 19 Suppl 1, 4–22. 10.1002/mpr.310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiviniemi MT, Orom H, Giovino GA, 2011. Psychological Distress and Smoking Behavior: The Nature of the Relation Differs by Race/Ethnicity. Nicotine Tob Res 13, 113–119. 10.1093/ntr/ntq218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH, 2000. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. JAMA 284, 2606–2610. 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung J, Gartner C, Dobson A, Lucke J, Hall W, 2011. Psychological Distress is Associated with Tobacco Smoking and Quitting Behaviour in the Australian Population: Evidence from National Cross-Sectional Surveys. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 45, 170–178. 10.3109/00048674.2010.534070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M-T, Burgess JF, Carey K, 2012. The association between serious psychological distress and emergency department utilization among young adults in the USA. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 47, 939–947. 10.1007/s00127-011-0401-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López N, Gadsden VL, 2016. Health Inequities, Social Determinants, and Intersectionality. NAM Perspectives, 10.31478/201612a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Han H, Barry CL, 2020. Psychological Distress and Loneliness Reported by US Adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA 324, 93. 10.1001/jama.2020.9740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire LC, Strine TW, Vachirasudlekha S, Anderson LA, Berry JT, Mokdad AH, 2009. Modifiable characteristics of a healthy lifestyle and chronic health conditions in older adults with or without serious psychological distress, 2007 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Int J Public Health 54, 84–93. 10.1007/s00038-009-0011-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhuri PK, 2013. Serious Psychological Distress and Mortality among Adults in the U.S. Household Population: Highlights, in: The CBHSQ Report. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US), Rockville (MD). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MA, Weinberger AH, 2020. Opioid Use Disorder Trends from 2002 to 2017 by Cigarette Smoking Status in the United States. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 10.1093/ntr/ntaa189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MA, Weinberger AH, Villanti AC, 2020. Quit ratios for cigarette smoking among individuals with opioid misuse and opioid use disorder in the United States. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 108164. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payton AR, 2009. Mental health, mental illness, and psychological distress: same continuum or distinct phenomena? J Health Soc Behav 50, 213–227. 10.1177/002214650905000207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivadon A, Matthews AK, David KM, 2014. Social Integration, Psychological Distress, and Smoking Behaviors in a Midwest LGBT Community. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc 20, 307–314. 10.1177/1078390314546952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stata Corp, 2019. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX. [Google Scholar]

- Streck JM, Weinberger AH, Pacek LR, Gbedemah M, Goodwin RD, 2020. Cigarette Smoking Quit Rates Among Persons With Serious Psychological Distress in the United States From 2008 to 2016: Are Mental Health Disparities in Cigarette Use Increasing? Nicotine Tob Res 22, 130–134. 10.1093/ntr/nty227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54). enter for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Sung H-Y, Prochaska JJ, Ong MK, Shi Y, Max W, 2011. Cigarette Smoking and Serious Psychological Distress: A Population-Based Study of California Adults. Nicotine Tob Res 13, 1183–1192. 10.1093/ntr/ntr148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz JA, Jantz I, 2014. Association Between Nonspecific Severe Psychological Distress as an Indicator of Serious Mental Illness and Increasing Levels of Medical Multimorbidity. Am J Public Health 104, 2350–2358. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health, Office on Smoking and Health, 2020. Smoking Cessation: A Report of the Surgeon General - Executive Summary. Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- Varescon L, Leignel S, Gérard C, Aubourg F, Detilleux M, 2013. Self-Esteem, Psychological Distress, and Coping Styles in Pregnant Smokers and Non-Smokers. Psychol Rep 113, 935–947. 10.2466/13.20.PR0.113x31z1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos T, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abd-Allah F, Abdulkader RS, Abdulle AM, Abebo TA, Abera SF, Aboyans V, Abu-Raddad LJ, Ackerman IN, Adamu AA, Adetokunboh O, Afarideh M, Afshin A, Agarwal SK, Aggarwal R, Agrawal A, Agrawal S, Ahmadieh H, Ahmed MB, Aichour MTE, Aichour AN, Aichour I, Aiyar S, Akinyemi RO, Akseer N, Al Lami FH, Alahdab F, Al-Aly Z, Alam K, Alam N, Alam T, Alasfoor D, Alene KA, Ali R, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Alkerwi A, Alla F, Allebeck P, Allen C, Al-Maskari F, Al-Raddadi R, Alsharif U, Alsowaidi S, Altirkawi KA, Amare AT, Amini E, Ammar W, Amoako YA, Andersen HH, Antonio CAT, Anwari P, Ärnlöv J, Artaman A, Aryal KK, Asayesh H, Asgedom SW, Assadi R, Atey TM, Atnafu NT, Atre SR, Avila-Burgos L, Avokphako EFGA, Awasthi A, Bacha U, Badawi A, Balakrishnan K, Banerjee A, Bannick MS, Barac A, Barber RM, Barker-Collo SL, Bärnighausen T, Barquera S, Barregard L, Barrero LH, Basu S, Battista B, Battle KE, Baune BT, Bazargan-Hejazi S, Beardsley J, Bedi N, Beghi E, Béjot Y, Bekele BB, Bell ML, Bennett DA, Bensenor IM, Benson J, Berhane A, Berhe DF, Bernabé E, Betsu BD, Beuran M, Beyene AS, Bhala N, Bhansali A, Bhatt S, Bhutta ZA, Biadgilign S, Bicer BK, Bienhoff K, Bikbov B, Birungi C, Biryukov S, Bisanzio D, Bizuayehu HM, Boneya DJ, Boufous S, Bourne RRA, Brazinova A, Brugha TS, Buchbinder R, Bulto LNB, Bumgarner BR, Butt ZA, Cahuana-Hurtado L, Cameron E, Car M, Carabin H, Carapetis JR, Cárdenas R, Carpenter DO, Carrero JJ, Carter A, Carvalho F, Casey DC, Caso V, Castañeda-Orjuela CA, Castle CD, Catalá-López F, Chang H-Y, Chang J-C, Charlson FJ, Chen H, Chibalabala M, Chibueze CE, Chisumpa VH, Chitheer AA, Christopher DJ, Ciobanu LG, Cirillo M, Colombara D, Cooper C, Cortesi PA, Criqui MH, Crump JA, Dadi AF, Dalal K, Dandona L, Dandona R, das Neves J, Davitoiu DV, de Courten B, De Leo DD, Defo BK, Degenhardt L, Deiparine S, Dellavalle RP, Deribe K, Des Jarlais DC, Dey S, Dharmaratne SD, Dhillon PK, Dicker D, Ding EL, Djalalinia S, Do HP, Dorsey ER, dos Santos KPB, Douwes-Schultz D, Doyle KE, Driscoll TR, Dubey M, Duncan BB, El-Khatib ZZ, Ellerstrand J, Enayati A, Endries AY, Ermakov SP, Erskine HE, Eshrati B, Eskandarieh S, Esteghamati A, Estep K, Fanuel FBB, Farinha CSES, Faro A, Farzadfar F, Fazeli MS, Feigin VL, Fereshtehnejad S-M, Fernandes JC, Ferrari AJ, Feyissa TR, Filip I, Fischer F, Fitzmaurice C, Flaxman AD, Flor LS, Foigt N, Foreman KJ, Franklin RC, Fullman N, Fürst T, Furtado JM, Futran ND, Gakidou E, Ganji M, Garcia-Basteiro AL, Gebre T, Gebrehiwot TT, Geleto A, Gemechu BL, Gesesew HA, Gething PW, Ghajar A, Gibney KB, Gill PS, Gillum RF, Ginawi IAM, Giref AZ, Gishu MD, Giussani G, Godwin WW, Gold AL, Goldberg EM, Gona PN, Goodridge A, Gopalani SV, Goto A, Goulart AC, Griswold M, Gugnani HC, Gupta Rahul, Gupta Rajeev, Gupta T, Gupta V, Hafezi-Nejad N, Hailu GB, Hailu AD, Hamadeh RR, Hamidi S, Handal AJ, Hankey GJ, Hanson SW, Hao Y, Harb HL, Hareri HA, Haro JM, Harvey J, Hassanvand MS, Havmoeller R, Hawley C, Hay SI, Hay RJ, Henry NJ, Heredia-Pi IB, Hernandez JM, Heydarpour P, Hoek HW, Hoffman HJ, Horita N, Hosgood HD, Hostiuc S, Hotez PJ, Hoy DG, Htet AS, Hu G, Huang H, Huynh C, Iburg KM, Igumbor EU, Ikeda C, Irvine CMS, Jacobsen KH, Jahanmehr N, Jakovljevic MB, Jassal SK, Javanbakht M, Jayaraman SP, Jeemon P, Jensen PN, Jha V, Jiang G, John D, Johnson SC, Johnson CO, Jonas JB, Jürisson M, Kabir Z, Kadel R, Kahsay A, Kamal R, Kan H, Karam NE, Karch A, Karema CK, Kasaeian A, Kassa GM, Kassaw NA, Kassebaum NJ, Kastor A, Katikireddi SV, Kaul A, Kawakami N, Keiyoro PN, Kengne AP, Keren A, Khader YS, Khalil IA, Khan EA, Khang Y-H, Khosravi A, Khubchandani J, Kiadaliri AA, Kieling C, Kim YJ, Kim D, Kim P, Kimokoti RW, Kinfu Y, Kisa A, Kissimova-Skarbek KA, Kivimaki M, Knudsen AK, Kokubo Y, Kolte D, Kopec JA, Kosen S, Koul PA, Koyanagi A, Kravchenko M, Krishnaswami S, Krohn KJ, Kumar GA, Kumar P, Kumar S, Kyu HH, Lal DK, Lalloo R, Lambert N, Lan Q, Larsson A, Lavados PM, Leasher JL, Lee PH, Lee J-T, Leigh J, Leshargie CT, Leung J, Leung R, Levi M, Li Yichong, Li Yongmei, Li Kappe D, Liang X, Liben ML, Lim SS, Linn S, Liu PY, Liu A, Liu S, Liu Y, Lodha R, Logroscino G, London SJ, Looker KJ, Lopez AD, Lorkowski S, Lotufo PA, Low N, Lozano R, Lucas TCD, Macarayan ERK, Magdy Abd El Razek H, Magdy Abd El Razek M, Mahdavi M, Majdan M, Majdzadeh R, Majeed A, Malekzadeh R, Malhotra R, Malta DC, Mamun AA, Manguerra H, Manhertz T, Mantilla A, Mantovani LG, Mapoma CC, Marczak LB, Martinez-Raga J, Martins-Melo FR, Martopullo I, März W, Mathur MR, Mazidi M, McAlinden C, McGaughey M, McGrath JJ, McKee M, McNellan C, Mehata S, Mehndiratta MM, Mekonnen TC, Memiah P, Memish ZA, Mendoza W, Mengistie MA, Mengistu DT, Mensah GA, Meretoja TJ, Meretoja A, Mezgebe HB, Micha R, Millear A, Miller TR, Mills EJ, Mirarefin M, Mirrakhimov EM, Misganaw A, Mishra SR, Mitchell PB, Mohammad KA, Mohammadi A, Mohammed KE, Mohammed S, Mohanty SK, Mokdad AH, Mollenkopf SK, Monasta L, Montico M, Moradi-Lakeh M, Moraga P, Mori R, Morozoff C, Morrison SD, Moses M, Mountjoy-Venning C, Mruts KB, Mueller UO, Muller K, Murdoch ME, Murthy GVS, Musa KI, Nachega JB, Nagel G, Naghavi M, Naheed A, Naidoo KS, Naldi L, Nangia V, Natarajan G, Negasa DE, Negoi RI, Negoi I, Newton CR, Ngunjiri JW, Nguyen TH, Nguyen QL, Nguyen CT, Nguyen G, Nguyen M, Nichols E, Ningrum DNA, Nolte S, Nong VM, Norrving B, Noubiap JJN, O’Donnell MJ, Ogbo FA, Oh I-H, Okoro A, Oladimeji O, Olagunju TO, Olagunju AT, Olsen HE, Olusanya BO, Olusanya JO, Ong K, Opio JN, Oren E, Ortiz A, Osgood-Zimmerman A, Osman M, Owolabi MO, Pa M, Pacella RE, Pana A, Panda BK, Papachristou C, Park E-K, Parry CD, Parsaeian M, Patten SB, Patton GC, Paulson K, Pearce N, Pereira DM, Perico N, Pesudovs K, Peterson CB, Petzold M, Phillips MR, Pigott DM, Pillay JD, Pinho C, Plass D, Pletcher MA, Popova S, Poulton RG, Pourmalek F, Prabhakaran D, Prasad NM, Prasad N, Purcell C, Qorbani M, Quansah R, Quintanilla BPA, Rabiee RHS, Radfar A, Rafay A, Rahimi K, Rahimi-Movaghar A, Rahimi-Movaghar V, Rahman MHU, Rahman M, Rai RK, Rajsic S, Ram U, Ranabhat CL, Rankin Z, Rao PC, Rao PV, Rawaf S, Ray SE, Reiner RC, Reinig N, Reitsma MB, Remuzzi G, Renzaho AMN, Resnikoff S, Rezaei S, Ribeiro AL, Ronfani L, Roshandel G, Roth GA, Roy A, Rubagotti E, Ruhago GM, Saadat S, Sadat N, Safdarian M, Safi S, Safiri S, Sagar R, Sahathevan R, Salama J, Saleem HOB, Salomon JA, Salvi SS, Samy AM, Sanabria JR, Santomauro D, Santos IS, Santos JV, Santric Milicevic MM, Sartorius B, Satpathy M, Sawhney M, Saxena S, Schmidt MI, Schneider IJC, Schöttker B, Schwebel DC, Schwendicke F, Seedat S, Sepanlou SG, Servan-Mori EE, Setegn T, Shackelford KA, Shaheen A, Shaikh MA, Shamsipour M, Shariful Islam SM, Sharma J, Sharma R, She J, Shi P, Shields C, Shifa GT, Shigematsu M, Shinohara Y, Shiri R, Shirkoohi R, Shirude S, Shishani K, Shrime MG, Sibai AM, Sigfusdottir ID, Silva DAS, Silva JP, Silveira DGA, Singh JA, Singh NP, Sinha DN, Skiadaresi E, Skirbekk V, Slepak EL, Sligar A, Smith DL, Smith M, Sobaih BHA, Sobngwi E, Sorensen RJD, Sousa TCM, Sposato LA, Sreeramareddy CT, Srinivasan V, Stanaway JD, Stathopoulou V, Steel N, Stein MB, Stein DJ, Steiner TJ, Steiner C, Steinke S, Stokes MA, Stovner LJ, Strub B, Subart M, Sufiyan MB, Sunguya BF, Sur PJ, Swaminathan S, Sykes BL, Sylte DO, Tabarés-Seisdedos R, Taffere GR, Takala JS, Tandon N, Tavakkoli M, Taveira N, Taylor HR, Tehrani-Banihashemi A, Tekelab T, Terkawi AS, Tesfaye DJ, Tesssema B, Thamsuwan O, Thomas KE, Thrift AG, Tiruye TY, Tobe-Gai R, Tollanes MC, Tonelli M, Topor-Madry R, Tortajada M, Touvier M, Tran BX, Tripathi S, Troeger C, Truelsen T, Tsoi D, Tuem KB, Tuzcu EM, Tyrovolas S, Ukwaja KN, Undurraga EA, Uneke CJ, Updike R, Uthman OA, Uzochukwu BSC, van Boven JFM, Varughese S, Vasankari T, Venkatesh S, Venketasubramanian N, Vidavalur R, Violante FS, Vladimirov SK, Vlassov VV, Vollset SE, Wadilo F, Wakayo T, Wang Y-P, Weaver M, Weichenthal S, Weiderpass E, Weintraub RG, Werdecker A, Westerman R, Whiteford HA, Wijeratne T, Wiysonge CS, Wolfe CDA, Woodbrook R, Woolf AD, Workicho A, Xavier D, Xu G, Yadgir S, Yaghoubi M, Yakob B, Yan LL, Yano Y, Ye P, Yimam HH, Yip P, Yonemoto N, Yoon S-J, Yotebieng M, Younis MZ, Zaidi Z, Zaki MES, Zegeye EA, Zenebe ZM, Zhang X, Zhou M, Zipkin B, Zodpey S, Zuhlke LJ, Murray CJL, 2017. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet 390, 1211–1259. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Gbedemah M, Wall MM, Hasin DS, Zvolensky MJ, Chaiton M, Goodwin RD, 2017. Depression Among Non-Daily Smokers Compared to Daily Smokers and Never-Smokers in the United States: An Emerging Problem. Nicotine Tob Res 19, 1062–1072. 10.1093/ntr/ntx009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Streck JM, Pacek LR, Goodwin RD, 2018. Nondaily Cigarette Smoking Is Increasing Among People With Common Mental Health and Substance Use Problems in the United States: Data From Representative Samples of US Adults, 2005–2014. J Clin Psychiatry 79, 0–0. 10.4088/JCP.17m11945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger AH, Zhu J, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wyka K, Goodwin RD, 2020. Cigarette Use, E-Cigarette Use, and Dual Product Use Are Higher Among Adults With Serious Psychological Distress in the United States: 2014–2017. Nicotine Tob Res 22, 1875–1882. 10.1093/ntr/ntaa061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman JF, Pratt LA, Miller EA, Parker JD, 2015. Serious Psychological Distress Among Adults: United States, 2009-2013. NCHS Data Brief 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Flaxman AD, Johns N, Burstein R, Murray CJ, Vos T, 2013. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet 382, 1575–1586. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Jardin C, Wall MM, Gbedemah M, Hasin D, Shankman SA, Gallagher MW, Bakhshaie J, Goodwin RD, 2018. Psychological Distress Among Smokers in the United States: 2008–2014. Nicotine Tob Res 20, 707–713. 10.1093/ntr/ntx099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]