Abstract

Myo-inositol is mainly found in astroglia and its levels has been shown to be reduced in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) of patients with schizophrenia. We investigate the status of astroglial integrity indexed by ACC myo-inositol at the onset and over the first 6 months of treatment of first episode schizophrenia. We employed 7 T magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) and quantified myo-inositol spectra at the dorsal ACC in 31 participants; 21 patients with schizophrenia with median lifetime antipsychotic exposure of less than 3 days, followed up after 6 months of treatment, and 10 healthy subjects scanned twice over the same period. We studied the time by group interaction for myo-inositol after adjusting for gender and age. We report significant reduction in myo-inositol concentration in the ACC in schizophrenia at an early, untreated state of acute illness that becomes insignificant over time, after instituting early intervention. This trajectory indicates that dynamic astroglial changes are likely to operate in the early stages of schizophrenia. MRS myo-inositol may be a critical marker of amelioration of active psychosis in early stages of schizophrenia.

Subject terms: Neurochemistry, Predictive markers, Schizophrenia

Introduction

Astrocytes appear to have many roles that are critical for the pathophysiology of schizophrenia1–3. In addition to their contribution to the redox balance in the brain4,5, they also clear extracellular glutamate from synaptic space6,7, maintain synaptic integrity and support myelination8–10, all of which are critical pieces in the mechanistic pathways suspected in schizophrenia10–12.

In vivo imaging of astrocytic function has been challenging as direct measures of astroglial activity are elusive. While not a direct marker of cellular activity, magnetic resonance spectroscopy (1H-MRS) allows the measurement of myo-inositol, a compound that is particularly abundant in astroglia than any other brain cells13,14. When astrocyte cells are activated due to excessive demands, increase in MRS myo-inositol resonance occurs15,16. An increase in myo-inositol also occurs as a response to brain injury17,18, in the form of astrogliosis19,20. The presence of lower than normal levels of myo-inositol may indicate an insufficient astroglial activity, and thus a state of vulnerability for redox imbalance, excitotoxicity, as well as a reduced ability to mount an appropriate astroglial-mediated inflammatory defence in the face of adversity1. A longitudinal reduction in myo-inositol levels over the course of an illness may indicate progressive astroglial pathology (see Supplementary Materials for more discussion on myo-inositol as a proxy for astroglial integrity).

In our previous work, we synthesized MRS studies reporting myo-inositol resonance in schizophrenia and reported a significant but small effect-size reduction of myo-inositol in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) in patients with schizophrenia21. To date, most of the studies have investigated patients with long-term exposure to antipsychotics. The only exception is Théberge et al.22, who did not observe any baseline differences in myo-inositol in unmedicated patients when examining small 1.5 cc voxels using a 4 T MRS approach reported to have a 35% smallest detectable difference for myo-inositol. The 10-months follow-up data in their study was available only for 13 patients, thus limiting the ability to detect longitudinal changes.

In this study, we tested if (1) astroglial dysfunction deficit indexed by ACC MRS measure of myo-inositol is present in early stages of psychosis and (2) whether this deficit progressively worsens or improves in the first 6 months of treatment. In line with our previous work, we expect to observe a significant reduction in MRS myo-inositol levels in patients with first episode schizophrenia compared to a cohort of healthy controls and that this deficit would improve significantly over the first 6 months of treatment. To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal report of myo-inositol from 7 T MRS in schizophrenia.

Results

Demographic data

Demographic and clinical data of subjects are shown in Table 1. As reported previously, the DUP (mean) was 29 weeks (SD = 26 weeks) and the duration of antipsychotic use was < 3 days prior to the first scan session. SOFAS scores were significantly different between the 2 groups (t(29) = 12.466, P < 0.001). The time in between baseline and follow-up (FUP) scan was 5.9 months (SD = 1.3 months) for patients and 7.3 months (SD = 1.9 months) for healthy controls (HC).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics.

| Characteristic | Patient group (N = 21) | Healthy controls (N = 10) | t/χ2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 16/5 | 5/5 | 2.13 | 0.145 |

| Marital status (Mar/S) | 1/20 | 1/9 | 0.31 | 0.58 |

| Inpatient at baseline (Y/N) | 11/10 | |||

| Family Hx (Y/N/DN) | 10/6/5 | |||

| AP exposure at baseline (M/SD; days) | 2.95/3.11 | |||

| Total DDD-days at baseline scan (M/SD) | 2.25/4.74 | |||

| Total DDD-days at FUP scan (M/SD) | 145.68/97.56 | |||

| DUP (M/SD/median; weeks) | 29.38/26.65/18 | |||

| Ethnicity (Black/White/Other) | 2/18/1 | 0/5/5 | 4.51 | 0.034a |

| Age (M/SD) | 22.33/5.29 | 21.60/3.37 | − 0.47 | 0.645 |

| SOFAS at baseline scan (M/SD) | 42.33/12.84 | 83.70/5.62 | 12.47 | 0.000 |

| SOFAS at FUP scan (M/SD) | 61.25/9.85 | 85.10/3.21 | 9.83 | 0.000 |

| PANSS-8 total at baseline scan (M/SD) | 24.67/5.30 | |||

| PANSS-8 total at FUP scan (M/SD) | 14.35/4.77 | |||

| Smoker (yes/no) | 6/15 | 0/10 | 3.54 | 0.060 |

| Cannabis user (yes/no) | 13/8 | 0/10 | 10.66 | 0.001 |

| Time between scans (M/SD; months) | 5.93/1.25 | 7.67/1.90 | 2.63 | 0.021 |

Mar married, S single, Y yes, N no, Hx history, DN don’t know, AP antipsychotic, M mean, SD standard deviation, DDD defined daily dose, FUP follow-up, DUP duration untreated psychosis.

P values for differences between groups were calculated using chi-square analyses for categorical variables and independent t tests for continuous variables.

aWhite vs non-White comparison.

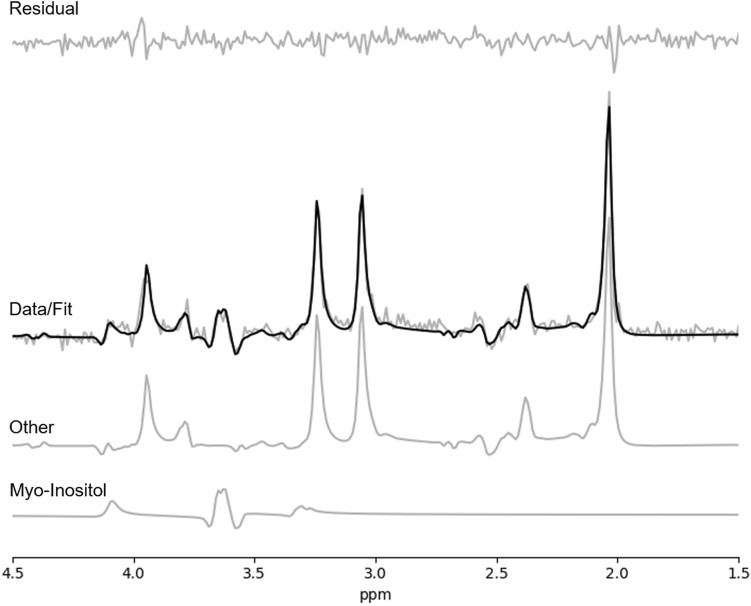

Cramer-Rao lower bounds (CRLB) values indicating the quality of myo-inositol measurement was quantified for both groups. Myo-inositol CRLB values for HC and FES were 4% (SD = 1%) for both baseline and FUP. Thus the 2 groups had acceptable qualitative metrics for myo-inositol estimation at both time points. A sample of fitted spectrum is presented in Fig. 1. We present the concentrations and CRLBs of metabolites other than myo-inositol in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 1.

Sample fitted spectrum of a single participant. Fit spectrum (bolded) is overlaid on the raw spectrum with the residual spectrum displayed above. The myo-inositol spectra and the sum of the remaining 16 template-included metabolites (labeled as ‘other’) are displayed below.

Myo-inositol levels

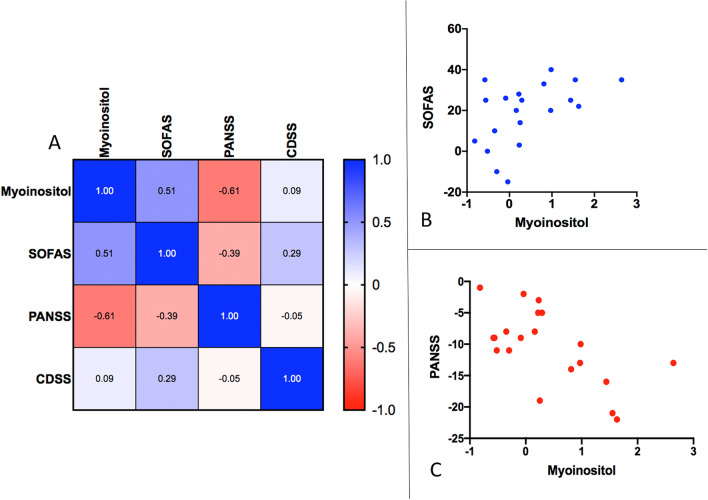

Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant group × time interaction (F(1,27) = 6.40, P = 0.018, partial eta-squared pη2 = 0.19) as well as a group effect (F(1,27) = 8.08, P = 0.008, pη2 = 0.23), between FES (M = 4.72 mM, SD = 0.64 mM) and HC (M = 5.44 mM, SD = 0.65 mM) but no effect on time (F(1,27) = 0.05, P = 0.83). Parameter estimates revealed that at baseline, FES had lower myo-inositol than healthy controls (t(29) = 4.88, P < 0.001), but this difference was not present at follow-up (t(29) = 0.78, P = 0.44). A simple contrast of time in each group revealed no significant effect in both the healthy control group (F(1,7) = 0.34, P = 0.58; 8.2% decrease) and in patients (F(1,18) = 0.28, P = 0.60; 8.9% increase) (Fig. 2). Younger age and female gender were associated with lower levels at both time points (F(1,27) = 8.1–11.2, pη2 = 0.14–0.36, P = 0.06–0.001).

Figure 2.

Means of myo-inositol [mM] for healthy controls (HC, blue) and patients (FES, red) at baseline and follow-up scan sessions. Subject-level myo-inositol changes are shown in light blue for healthy controls and pink for patients. Asterisk denotes significant difference between means (Note: y-axis values do not begin at 0 for improving data visualization).

Lastly, the time interval between scans in months was not related to myo-inositol concentration differences (FUP-baseline) in either group (HC: r = 0.005, P = 0.90; FES: r = − 0.096, P = 0.68). Nevertheless, to address spurious differences in change scores that may arise due to time differences in between scans, we generated time-adjusted, i.e. annualized myo-inositol concentration values. Annualized change scores in myo-inositol change were significantly different between the two groups (t(29) = − 2.50, P = 0.018) and indicated a 0.19 mM/year (SD = 0.37 mM) increase in patients and a 0.12 mM/year (SD = 0.15 mM) reduction in healthy controls.

Myo-inositol and clinical measures

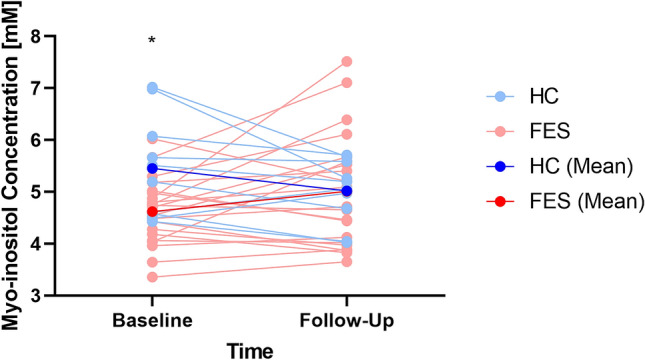

As myo-inositol concentration increased in patients, PANSS-8 scores reduced significantly (Spearman’s rho = − 0.61, P = 0.004) and SOFAS increased marginally (rho = 0.44, P = 0.05), but changes in myo-inositol did not track changes in depressive burden measured using CDSS (rho = 0.001, P = 0.90) (Fig. 3). There was no significant correlation between annualized myo-inositol concentration changes and DUP (rho = 0.05, P = 0.83). We also did not see any correlation between baseline (unadjusted) myo-inositol concentration and DUP (rho = 0.30, P = 0.22), SOFAS (rho = − 0.27, P = 0.23), CDSS (rho = − 0.10, P = 0.65), or PANSS-8 total (rho = 0.18, P = 0.43).

Figure 3.

Relationship between longitudinal change in myo-inositol levels and illness burden. (A) Heat map of linear correlations among change values (baseline to 6-months follow-up). (B) Correlation plot of the relationship between SOFAS and myo-inositol change scores. (C) Correlation plot of the relationship between PANSS-8 and myo-inositol change scores. Images were generated using GraphPad Prism version 9 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA, www.graphpad.com). CDSS Calgary depression scale in schizophrenia, PANSS-8 positive and negative symptom scale—8 item version, SOFAS Social and Occupational Functioning Scale.

There was no significant relationship between baseline antipsychotic exposure defined daily dose (DDD) myo-inositol levels (rho = − 0.15, P = 0.51) and DDD at follow-up and myo-inositol (rho = − 0.06, P = 0.81) as well as between DDD at follow-up and annualized myo-inositol change (rho = − 0.14, P = 0.56). See the Supplementary Materials for the association between the change scores in myo-inositol and glutamate, a putative marker of the metabolic integrity of excitatory neurons.

To examine the effect of injectables vs. oral atypical antipsychotics on follow-up levels of myo-inositol, we studied the effects of using long-acting injectables (n = 8) vs. oral antipsychotics (n = 11). There was no significant difference in myo-inositol levels at 6-months (LAI users mean (SD) = 4.67(0.96); non-users mean (SD) = 5.35(1.20); t(17) = − 1.38, P = 0.19). To examine the effect of partial agonists vs. D2-blockers on clinical outcome, we studied the effects of using partial agonists (aripiprazole and brexpiprazole, n = 10) vs. other D2-antagonists (n = 9) on the myo-inositol levels at 6-months. There was no significant difference in myo-inositol levels at 6-months (partial agonists mean (SD) = 4.98(0.89); D2-antagonists mean (SD) = 5.16(1.41); t(17) = -0.34, P = 0.74). A detailed list of patient antipsychotic drug information can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Discussion

We report 3 major observations in this study: (1) astroglial dysfunction indexed by reduced ACC MRS myo-inositol resonance is present in early stages of psychosis and (2) this effect of diagnosis is limited to the untreated stage of illness and (3) improvement in myo-inositol levels relate to decreasing burden of psychotic symptom severity and improving social and occupational functioning. Taken together, this longitudinal report of myo-inositol resonance from 7 T MRS in first episode schizophrenia supports a role for early astroglial dysfunction that may track symptom burden and functional outcomes of the illness. As reported in the Supplementary Materials, the longitudinal changes in myo-inositol are also statistically associated with the changes in glutamate levels. This indicates that a shared process may underlie the changes in neuro-metabolites that are subject to astroglial regulation in early stages of schizophrenia.

In contrast to Chiappelli et al.23, we did not observe a relationship between myo-inositol resonance and depressive burden in our sample. Our sample excluded patients with affective psychosis and exclusively consisted of untreated individuals, unlike the sample recruited by Chiappelli and colleagues. In contrast, we noted a significant correlation between symptom and function improvement and increasing myo-inositol values. Plitman et al.24 did not observe a similar relationship between symptom burden and myo-inositol levels, though their measurement was restricted to associative striatum. It is likely that the critical changes in astroglia are regionally distinct, and likely involve ACC preferentially25–27.

We report a significant group effect indicating myo-inositol reduction in FES; this is consistent with the meta-analysis of numerous MRS studies reporting a reduction of small effect-size in established schizophrenia21. The lack of group differences in myo-inositol levels that we report in patients at follow-up may indicate a process of normalisation with clinical improvement in early stages. Notable fluctuations can occur in in myo-inositol levels over time, even in the absence of a disease process, as demonstrated by an equivalent magnitude of the effect of time in the healthy control group. Given that the main source of myo-inositol in human brain is the phosphoinositide pathway involving the cell membranes28, many physiological conditions that affect the membrane properties can affect myo-inositol concentration (e.g., plasma sodium levels29, osmolality30, diet patterns31, sleep deprivation32, exercise habits33). Changes in the biophysical properties of the cell membrane induces rapid and reversible changes in brain myo-inositol at a much shorter time scale than the one employed in our study34. In this context, the clinical correlations reported here are best considered as one of many factors that influence these fluctuations in the patient group. On the other hand, in disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, a longitudinal increase in myo-inositol occurs in relation to increased severity of neurodegenerative changes35,36. Further longitudinal studies with multiple time points of measurements over longer periods of time are warranted to clarify this issue in psychosis.

Some of the notable strengths of our study include the use of 7 T scanner, and recruiting highly symptomatic, mostly drug-naïve individuals. Some of the limitations include the use of a single voxel (dorsal ACC) and a single time point (6 months) for follow-up; as a result, we cannot exclude the possibility of increased or preserved levels of myo-inositol in other brain regions or at ACC at the later stages of the illness. It is worth noting that myo-inositol participates in several neuronal and astroglial cellular processes, involving glucose and lipid metabolism and ion channel functions37. Intracellular myo-inositol levels can be altered by a wide variety of metabolic impairments37 as well as the use of mood stabilisers38. Our interpretation of myo-inositol resonance as a reflection of astroglial integrity is in line with the majority of MRS literature to date39–41; nevertheless, it should be only considered as a proxy marker of astroglial integrity. Furthermore, astrocyte count and thus myo-inositol resonance, may reduce with antipsychotic exposure, as shown in macaques exposed to haloperidol or olanzapine42. This effect is controversial, as antipsychotic-induced increase in astroglial density has been reported in rats43 and rhesus monkeys44. Drug-induced astrocyte depletion, if present in our sample, would have further reduced the myo-inositol levels at 6-months follow-up; but we observed lower values in patients than controls at the baseline, before exposure to antipsychotics was established. This is further supported by the lack of treatment-induced changes on MRS myo-inositol levels reported in a recent meta-analysis across various stages of schizophrenia45. Finally, though our sample size, especially for healthy controls was limited, this was sufficient to detect the postulated Group × Time interaction.

In summary, this longitudinal 7 T MRS study of ACC confirms the presence of reduced myo-inositol in the early stages of schizophrenia, that may progressively improve in patients who also show symptomatic improvement. This supports the possibility of a putative astroglial deficit predating the first presentation of psychosis, likely of early developmental46 or of inflammatory47 origin, but showing a trend of reversal with early intervention. Further, this also raises the need for experimental studies targeting the putative astroglial dysfunction, as this may improve clinical and functional outcomes in psychosis.

Methods

This sample has been previously reported48, and comprises 21 volunteers with first-episode schizophrenia (FES) and 10 healthy volunteers. Healthy controls were recruited by word-of-mouth and group-matched for age, gender, and parental socio-economic status. Both groups were studied around the same time (Supplementary Table S1). Patients were required to have < 14 days of lifetime exposure to antipsychotics and satisfy a consensus diagnosis of first-episode schizophrenia by 3 psychiatrists after 6 months of program entry, based on the DSM-5 criteria49 and Leckman’s best estimate procedure50. Any participant whose 6-month diagnoses were bipolar or major depressive disorder with psychoses, as well as suspected drug-induced psychoses, were excluded from the study. All patients were recruited from the PEPP (Prevention and Early Intervention for Psychosis Program) at London Health Sciences Centre and received routine care, in line with the Canadian standards for early intervention in psychosis51. Healthy volunteers were screened to ensure to have no personal history of mental illness and no family history of psychotic disorder. None of the participants had a significant head injury, major medical illness, or MRI contraindications. All subjects provided written, informed consent according to the guidelines of the Human Research Ethics Board for Health Sciences at Western University, London, Ontario. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Western University Research Ethics Board of the University of Western Ontario.

MRS acquisition and analysis

MRS measurements were acquired using a Siemens MAGNETOM 7 T head-only MRI scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) and a site-built head coil (8-channel transmit, 32-channel receive) at the Centre for Functional and Metabolic Mapping of Western University (London, Ontario). This acquisition has been employed in our prior MRS studies48,52,53. Further details of the acquisition and spectral fitting are described in the Supplementary Materials.

Clinical assessment

The following clinical assessments were undertaken on the same day of scanning:

Psychotic symptom severity measured using PANSS-854,55 scale.

The overall social and occupational functioning at the time of first presentation using SOFAS56.

Depressive burden measured using Calgary Depression Scale in Schizophrenia (CDSS).

In addition, we also assessed the duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) using multiple sources of information provided by the patient, the referring sources, and caregivers as well as by reviewing clinical charts. We used the first emergence of positive psychotic symptoms as the starting point for calculating the DUP, in line with prior work57.

Statistical analyses

All statistical tests were computed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 2658. Group demographic differences were calculated using t tests and chi-square tests for continuous and dichotomous variables, respectively. Repeated measures ANOVA was used to assess group × time interaction (primary hypothesis), as well as group effect and time effect, with parameter estimates examined to test individual group effects. As age and gender are known modifiers of myo-inositol levels, they were entered as covariates in the ANOVA model. When correlating changes in myo-inositol to clinical features, all changes scores were calculated as (follow-up—baseline), in the same direction for all variables.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. Trevor Szekeres, Mr. Scott Charlton, Mr. Joseph Gati for their assistance in data acquisition and archiving. We thank all research team members of the NIMI lab and all the staff members of the PEPP London team, particularly Drs. Kara Dempster, Julie Richard, Priya Subramanian and Hooman Ganjavi for their assistance in patient recruitment and supporting clinical care. We gratefully acknowledge the participants and their family members for their contributions. Requests for data should be addressed to Dr. Lena Palaniyappan.

Author contributions

P.J. acquired the MRS scans, performed the MRS quantification and analysis, supervised by J.T. M.M. recruited patients, collected, and compiled demographic data and assisted in acquiring the scans. L.P. obtained the research funds and designed the project with J.T. L.P. conceived the analysis and wrote the first draft with P.J. All authors contributed to the writing and have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by CIHR Foundation Grant (375104/2017) to LP; AMOSO Opportunities fund to LP; partial salary support of PJ by NSERC Discovery Grant (RGPIN-2016-05055) to JT, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry Dean’s Scholarship to PJ; Parkwood Institute Studentship to MM. Data acquisition was supported by the Canada First Excellence Research Fund to BrainSCAN, Western University (Imaging Core); Innovation fund for Academic Medical Organization of Southwest Ontario (Opportunities Fund); Bucke Family Fund, The Chrysalis Foundation and The Arcangelo Rea Family Foundation (London, Ontario). Compute Canada Resources (Application No. 1530) were used in the storage and analysis of imaging data. LP acknowledges salary support from the Tanna Schulich Chair of Neuroscience and Mental Health.

Competing interests

LP reports personal fees from Otsuka Canada, SPMM Course Limited, UK, Canadian Psychiatric Association; book royalties from Oxford University Press; investigator-initiated educational grants from Janssen Canada, Sunovion and Otsuka Canada outside the submitted work. All other authors report no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-01773-7.

References

- 1.Bernstein HG, Steiner J, Bogerts B. Glial cells in schizophrenia: Pathophysiological significance and possible consequences for therapy. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2009;9:1059–1071. doi: 10.1586/ern.09.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison PJ. Neuropathology of schizophrenia. Psychiatry. 2005;4:18–21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnieder TP, Dwork AJ. Searching for neuropathology: Gliosis in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry. 2011;69:134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bélanger M, Allaman I, Magistretti PJ. Brain energy metabolism: Focus on Astrocyte-neuron metabolic cooperation. Cell Metab. 2011;14:724–738. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dringen R, Pfeiffer B, Hamprecht B. Synthesis of the antioxidant glutathione in neurons: Supply by astrocytes of CysGly as precursor for neuronal glutathione. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:562–569. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-02-00562.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rose CF, Verkhratsky A, Parpura V. Astrocyte glutamine synthetase: Pivotal in health and disease. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2013;41:1518–1524. doi: 10.1042/BST20130237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schousboe A, Scafidi S, Bak LK, Waagepetersen HS, McKenna MC. Glutamate Metabolism in the Brain Focusing on Astrocytes. Springer; 2014. pp. 13–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bélanger M, Magistretti PJ. The role of astroglia in neuroprotection. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2009;11:281–295. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.3/mbelanger. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volterra A, Meldolesi J. Astrocytes, from brain glue to communication elements: The revolution continues. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;6:626–640. doi: 10.1038/nrn1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Windrem MS, et al. Human iPSC glial mouse chimeras reveal glial contributions to schizophrenia. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xia M, Abazyan S, Jouroukhin Y, Pletnikov M. Behavioral sequelae of astrocyte dysfunction: Focus on animal models of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2016;176:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan LE, et al. Pathway analyses implicate glial cells in schizophrenia. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e89441. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glanville NT, Byers DM, Cook HW, Spence MW, Palmer FBSC. Differences in the metabolism of inositol and phosphoinositides by cultured cells of neuronal and glial origin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Lipids Lipid Metab. 1989;1004:169–179. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(89)90265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hattingen E, et al. Myo-inositol: A marker of reactive astrogliosis in glial tumors? NMR Biomed. 2008;21:233–241. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filibian M, et al. In vivo imaging of glia activation using 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy to detect putative biomarkers of tissue epileptogenicity. Epilepsia. 2012;53:1907–1916. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothermundt M, et al. Glial cell activation in a subgroup of patients with schizophrenia indicated by increased S100B serum concentrations and elevated myo-inositol. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007;31:361–364. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris JL, Choi IY, Brooks WM. Probing astrocyte metabolism in vivo: Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the injured and aging brain. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:202. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kierans AS, et al. Myoinositol and glutamate complex neurometabolite abnormality after mild traumatic brain injury. Neurology. 2014;82:521–528. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geiszler PC, et al. Dynamic metabolic patterns tracking neurodegeneration and gliosis following 26S proteasome dysfunction in mouse forebrain neurons. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:4833. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23155-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pardon MC, et al. Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy discriminates the response to microglial stimulation of wild type and Alzheimer’s disease models. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:19880. doi: 10.1038/srep19880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das TK, et al. Putative astroglial dysfunction in schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of H-MRS studies of medial prefrontal myo-inositol. Front. Psychiatry. 2018 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Théberge J, et al. Longitudinal grey-matter and glutamatergic losses in first-episode schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2007;191:325. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.033670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiappelli J, et al. Evaluation of myo-inositol as a potential biomarker for depression in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:2157–2164. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plitman E, et al. Elevated myo-inositol, choline, and glutamate levels in the associative striatum of antipsychotic-naive patients with first-episode psychosis: A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study with implications for glial dysfunction. Schizophr. Bull. 2016;42:415–424. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katsel P, et al. Astrocyte and glutamate markers in the superficial, deep, and white matter layers of the anterior cingulate gyrus in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1171–1177. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams MR, et al. Astrocyte decrease in the subgenual cingulate and callosal genu in schizophrenia. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2013;263:41–52. doi: 10.1007/s00406-012-0328-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarasov VV, et al. Alterations of astrocytes in the context of schizophrenic dementia. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;10:1612. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fisher SK, Novak JE, Agranoff BW. Inositol and higher inositol phosphates in neural tissues: Homeostasis, metabolism and functional significance. J. Neurochem. 2002;82:736. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soupart A, Silver S, Schroëder B, Sterns R, Decaux G. Rapid (24-hour) reaccumulation of brain organic osmolytes (particularly myo-inositol) in azotemic rats after correction of chronic hyponatremia. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002;13:1433. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000017903.77985.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silver SM, Schroeder BM, Sterns RH. Brain uptake of myoinositol after exogenous administration. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002;13:1255. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1351255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raider K, et al. A high fat diet alters metabolic and bioenergetic function in the brain: A magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Neurochem. Int. 2016;97:172. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urrila AS, et al. Frontal cortex myo-inositol is associated with sleep and depression in adolescents: A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Neuropsychobiology. 2017;75:21. doi: 10.1159/000478861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schranz AL, et al. Brain metabolite levels in sedentary women and non-contact athletes differ from contact athletes. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2020.593498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rango M, et al. Myoinositol content in the human brain is modified by transcranial direct current stimulation in a matter of minutes: A 1H-MRS study. Magn. Reson. Med. 2008;60:782. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang W, et al. High brain myo-inositol levels in the predementia phase of Alzheimer’s disease in adults with Down’s syndrome: A 1H MRS study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1999;156:1879–1886. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.12.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voevodskaya O, et al. Brain myoinositol as a potential marker of amyloid-related pathology: A longitudinal study. Neurology. 2019;92:e395–e405. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chhetri DR. Myo-inositol and its derivatives: Their emerging role in the treatment of human diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2019;10:1172. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.01172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harwood AJ. Lithium and bipolar mood disorder: The inositol-depletion hypothesis revisited. Mol. Psychiatry. 2005;10:117–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang L, Munsaka SM, Kraft-Terry S, Ernst T. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy to assess neuroinflammation and neuropathic pain. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8:576–593. doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9460-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haris M, Cai K, Singh A, Hariharan H, Reddy R. In vivo mapping of brain myo-inositol. Neuroimage. 2011;54:2079–2085. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woodcock EA, Hillmer AT, Mason GF, Cosgrove KP. Imaging biomarkers of the neuroimmune system among substance use disorders: A systematic review. Mol. Neuropsychiatry. 2019;5:125–146. doi: 10.1159/000499621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Konopaske GT, et al. Effect of chronic antipsychotic exposure on astrocyte and oligodendrocyte numbers in macaque monkeys. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;63:759–765. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vernon AC, et al. Reduced cortical volume and elevated astrocyte density in rats chronically treated with antipsychotic drugs—Linking magnetic resonance imaging findings to cellular pathology. Biol. Psychiatry. 2014;75:982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Selemon LD, Lidow MS, Goldman-Rakic PS. Increased volume and glial density in primate prefrontal cortex associated with chronic antipsychotic drug exposure. Biol. Psychiatry. 1999;46:161–172. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kubota M, Moriguchi S, Takahata K, Nakajima S, Horita N. Treatment effects on neurometabolite levels in schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies. Schizophr. Res. 2020;222:122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dietz AG, Goldman SA, Nedergaard M. Glial cells in schizophrenia: A unified hypothesis. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:272–281. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30302-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Almeida PGC, Nani JV, Oses JP, Brietzke E, Hayashi MAF. Neuroinflammation and glial cell activation in mental disorders. Brain Behav. Immun. Health. 2020;2:100034. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2019.100034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jeon P, et al. Progressive changes in glutamate concentration in early stages of schizophrenia—A longitudinal 7-Tesla MRS study. Schizophr. Bull. Open. 2021;2:1–9. doi: 10.1093/schizbullopen/sgaa072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.First MB, Williams JBW, Karg RS, Spitzer RL. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Research Version. American Psychiatric Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leckman JF, Sholomskas D, Thompson D, Belanger A, Weissman MM. Best estimate of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis: A methodological study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1982;39:879–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290080001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Addington D, Anderson E, Kelly M, Lesage A, Summerville C. Canadian practice guidelines for comprehensive community treatment for schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Can. J. Psychiatry. 2017;62:662–672. doi: 10.1177/0706743717719900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park MTM, et al. Hippocampal neuroanatomy in first episode psychosis: A putative role for glutamate and serotonin receptors. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2021;110:110297. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jeon P, et al. Glutathione as a molecular marker of functional impairment in patients with at-risk mental state: 7-Tesla 1H-MRS study. Brain Sci. 2021;11:941. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11070941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin CH, et al. Early improvement in PANSS-30, PANSS-8, and PANSS-6 scores predicts ultimate response and remission during acute treatment of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2018;137:98–108. doi: 10.1111/acps.12849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andreasen NC, et al. Remission in schizophrenia: Proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2005;162:441. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, Ugolini S, Pioli R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV social occupational functioning assessment scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2000;101:323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singh SP, et al. Determining the chronology and components of psychosis onset: The Nottingham Onset Schedule (NOS) Schizophr. Res. 2005;80:117–130. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. 2019 (2019).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.