Abstract

Background

Financial incentives may aid recruitment to clinical trials, but evidence regarding risk/burden-driven variability in participant preferences for incentives is limited. We developed and tested a framework to support real-world decisions on recruitment budget.

Methods

We included two phases: an Anchoring Survey, to ensure we could capture perceived unpleasantness on a range of life events, and a Vignette Experiment, to explore relationships between financial incentives and participants’ perceived risk/burden and willingness to participate in high- and low-risk/burden versions of five vignettes drawn from common research activities. We compared vignette ratings to identify similarly rated life events from the Anchoring Survey to contextualize ratings of study risk.

Results

In our Anchoring Survey (n=643), mean ratings (scale 1=lowest risk/burden to 5=highest risk/burden) indicated that the questions made sense to participants, with highest risk assigned to losing house in a fire (4.72), and lowest risk assigned to having blood pressure taken (1.13). In the Vignette Experiment (n=534), logistic regression indicated that amount of offered financial incentive and perceived risk/burden level were the top two drivers of willingness to participate in four of the five vignettes. Comparison of event ratings in the Anchoring Survey with the Vignette Experiment ratings suggested reasonable concordance on severity of risk/burden.

Conclusions

We demonstrated feasibility of a framework for assessing participant perceptions of risk for study activities and discerned directionality of relationship between financial incentives and willingness to participate. Future work will explore use of this framework as an evidence-gathering approach for gauging appropriate incentives in real-world study contexts.

Keywords: Financial Incentives, Motivation, Clinical Trials as Topic, Participant Recruitment

Introduction

The health advances of tomorrow are made possible by completion of high-quality research. While many factors must align, recruitment and retention of participants are essential elements in all clinical trials. Recruitment, however, remains a significant challenge -- major analyses found that about one in five studies were either terminated early because of inability to meet enrollment goals or were completed far short of accrual goals.1–4 These findings emphasize that recruitment is both challenging and important.

Many potential barriers to trial participation can come into play from the participant’s perspective including lack of awareness of research opportunities and considerations that might be characterized as risk and burden, including time burden, transportation and other expenses, and perceived risk of study procedures.5–9 Moderate evidence exists that monetary compensation helps to overcome some of these barriers and that participants place value on the concept of financial incentives in clinical research,10–13 but requires investigators to navigate the line between offering a financial incentive that makes research participation more feasible for participants while avoiding undue influence.5,14,15 Moreover, researchers may be constrained by limited budget16 and little guidance on estimating the optimal amount to budget for incentives.17 Beyond earmarking money in the study budget, researchers have suggested pursuing funds from institutional coffers, managed care plans, or small ad hoc grants to pay for a financial incentive.5

Determining appropriate incentive amounts is also an area with relatively limited evidence and significant uncertainty. Researchers may often feel limited in knowledge about intended participants’ perception of risk/burden from the intended research population18–20 and participants’ expectations.21 Some data also suggests that the appropriate amount of financial incentive, as defined by prospective participants, can vary by factors such as respondent income or age and the perceived risk of the study.13,22,23 Furthermore, researchers may need to contend with variability in institutional review board (IRB) assessments of acceptable incentives and avoidance of coercion.20

Determining financial incentive size can be based on different conceptualizations of its purpose, including a market-based or wage-based estimate of time and burden, reimbursement for incurred expenses, or an appreciation-based token reward. 24 In the present research, we focus on two factors that can inhibit volunteering for a trial that can be influenced by a financial incentive. One factor is the participant perception of the risk that participation entails, with higher-risk studies calling for greater financial incentive.9,25,26 Participant burden is the second factor we believe is important in setting the size of a financial incentive, including negative factors (e.g., risk, burden) associated with the study that all participants will experience.27

The Recruitment Innovation Center, funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, focuses on developing innovative, informatics-driven approaches and evidence-based recruitment solutions to minimize or prevent issues that hamper successful trial completion. We undertook the current project to enhance the collective evidence base regarding optimal approaches to determining financial incentives. The current two-component study was designed to test our ability to develop and deploy an information gathering tool to support decisions on budget for recruitment in the real world, empowered and informed by participants sharing their insights and values on a range of situations. We share lessons learned and plans for extension to actual trials.

Methods

Our goal in the current work was to develop an evidence-based framework to gather input on expected financial incentives from the perspective of potential clinical trial participants. Our ultimate vision is to create an operational model for distilling relevant information about clinical trial expectations into lay language, then asking lay individuals representing the anticipated population of trial participants to provide input on their willingness to join the trial based on numerous factors, including financial incentives.

Our initial efforts in this relatively unexplored area required two sub-studies. First, we needed to ensure we could adequately capture meaningful input from individuals regarding self-reported feelings of unpleasantness or undesirability. To accomplish this, we deployed a survey requesting input on a broad range of negative life events (Anchoring Survey). This approach enabled use of the resulting data to build context that we could later employ as a frame of reference (i.e., an anchoring dataset) for understanding participant evaluations of the risk/burden of activities related to potential clinical trial participation, by comparing the relative risk/burden of study activities with risk/burden of various negative life events.

Next, we used experimental vignettes to gauge whether participants’ assessment of the impact of financial incentive levels varied by perceived risk and/or burden associated with common study activities (Vignette Experiment). In the present study, we did not differentiate between risk (e.g. potential adverse effects) and burden (e.g. time, travel expenses) since they are heavily confounded in real life but label our combined variable as risk/burden to represent these interrelated concepts.

Appendix A and B include the survey instruments used in the Anchoring Survey and the Vignette Experiment. All data were collected and managed using the REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) secure web-based data collection platform hosted at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.28 Both substudies were reviewed and approved by the Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board as exempt research (IRB #181223 and #191118).

Participants

Participants for both surveys were drawn from ResearchMatch, a national, non-profit, volunteer-to-researcher matching platform which includes a community of more than 150,000 volunteers.29 In both surveys, we asked individuals to self-report a brief set of demographic characteristics including race and ethnicity, sex, annual household income, age group, and educational attainment.

Anchoring Survey

Our objective for the Anchoring Survey was to collect responses from a diverse population of respondents regarding their evaluation of the unpleasantness or negativity of various events of daily life, to enable anchoring in the Vignette Experiment by comparing participation in trial to these negative life events. Our initial selection of negative life events was reviewed by the Recruitment Innovation Center Community Advisory Board (CAB), a group of community members representing various geographic regions and diverse communities across the U.S. who provide feedback on recruitment and retention issues. The CAB encouraged us to add events from the Urban Hassles Scale.30

Our final selection of events were drawn from multiple sources, including the Kanner Hassles Scale,31 the Urban Hassles Scale,30 as well as items reflecting a range of common clinical trial procedures and health-related events. We presented the items in random order. We limited the list of life events to a total of 68 to balance a diversity of event types and range of negativity, while not being burdensome on the respondent; the survey was estimated to take 10 minutes to complete. The survey included an equal mix of high, medium and low negative events. Respondents were asked to rate the unpleasantness or undesirability for each event using a five-point scale, ranging from 1, not at all bad, to 5, extremely bad.

For the Anchoring Survey, we sent invitations based on demographics collected by ResearchMatch, focusing on those demographics that might be most related to financial incentives. These included sex (male/female), age (≤ 40 or > 40) and race (White, Black or African American, and a pooled group of the remaining self-reported race categories available in ResearchMatch (American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, Multiracial, or Other)). Our target sample size was 600 respondents and invitations were sent in waves to balance responses among the demographic categories. Participants in this first survey had the option to enter their names into a drawing, with 20 participants selected at random to receive a $50 Amazon gift card.

Vignette Experiment

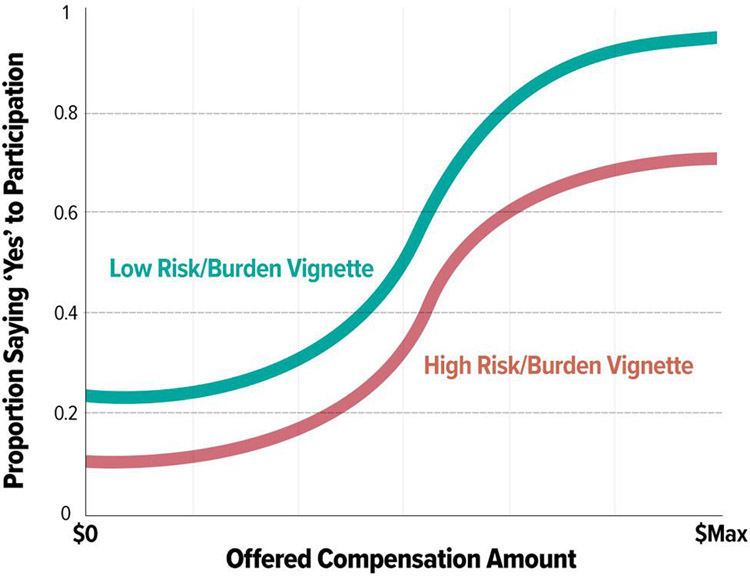

In our second phase, we gathered participant perspectives on issues related to incentives for study participation using the experimental vignette method.32 Our goal was to develop a replicable survey model capable of creating ‘likelihood of participation’ versus ‘incentive amount’ estimate curves (Figure 1) for any given research vignette by surveying individuals matching the general population of interest for a research study.

Figure 1:

What We Expected to Find. Estimating effects of incentives on participant agreement to participate in a study.

Creating a ‘real world’ methodological model to support this framework required additional considerations. First, it was necessary to constrain the offered payment amounts to a reasonable range (e.g., lowest offered amount = $0; highest offered amount = $Max). Determining the amount of payment for volunteering in the studies presented in the vignettes was informed by reviewing real world studies via ClinicalTrials.gov33 and available internal and external34 compensation materials. Next, it was important to choose discrete incentive amounts within that reasonable range for each vignette/incentive to allow meaningful point estimates from the population (e.g., probability of participation at any given offered amount = mean number of positive responses from the group of individuals offered that given amount during the survey process).

Given our goal in this project to create a generalizable methods framework to support any study where a clear vignette can be written and a population of representative study participants can be identified, we wanted to test the model on multiple vignette types representing common study activities. We asked three experienced research coordinators to brainstorm and define five separate common domain areas (e.g., having a radiologic procedure) and within each domain area define a ‘low concern’ scenario (e.g., the new medication has no known side effects) and a ‘high concern’ scenario (e.g., the new medication is known to frequently induce nausea). We then worked to describe each low and high risk/burden vignette for each of the five domains in lay language suitable for presentation. We intentionally designed these scenarios to represent common study procedure descriptions to facilitate generalizability and to allow respondents, including those with and without medical conditions, to evaluate risk/burden. We further refined the vignettes using feedback from the CAB and the Recruitment Innovation Center team.

Realizing that realistic incentive amounts would be dependent on perceived risk and/or burden for each domain, we asked study coordinators to suggest a reasonable amount of payment for each high and low risk vignette based on historical experience with active research studies, using the resources described above. Table 1 provides a listing of each vignette domain, lay language for both low and high vignette descriptions, and the financial incentives suggested by our research coordinator team.

Table 1:

Overview of the Five Vignettes Employed in the Vignette Experiment

| Vignette type | Risk/burden level | Vignette details | Reasonable amount for an incentive |

|---|---|---|---|

| Notes | Low | You will keep daily notes of how much water you drink for one week. You will need to make only one clinic visit to go over your notes with a staff member. | $10 |

| Notes | High | You will keep daily notes of drug use and sexual activity for 3 months. You will make a clinic visit each month for 3 months to go over your notes with a staff member. | $25/month (total $75) |

| Drug | Low | You will take a safe drug once a day for one week. You may have slight dry mouth as a side effect of the drug. | $5.00/dose (total $35) |

| Drug | High | You will take a safe drug twice a day for a month. You will probably feel very nauseated (sick to your stomach) as a side effect of the drug. | $5.00/dose (total $300) |

| Xray/CT | Low | You will have one chest x-ray. The amount of radiation from this x-ray is very low. It is same amount of radiation that most people in the country get in 10 days. You will need to make only one clinic visit. | $25 |

| Xray/CT | High | You will receive 3 chest CT-scans. A CT-scan uses a series of x-rays to create pictures of your bones, organs, and other tissues. These 3 scans will expose you to the same amount of radiation that most people in the country get in 5 years. You will have to get the CT scan every 4 months for a year. | $55/scan (total $165) |

| Blood/Muscle | Low | You will have one tube (3 teaspoons) of blood taken from your arm. You will need to come into the clinic once a month for 3 months to have your blood draw. Like most blood draws, this could cause you a little pain or stress. | $25/draw (total $75) |

| Blood/Muscle | High | You will have a cut made to get a small amount of muscle tissue from your thigh. This is a very painful procedure that may leave a small scar. You will have to get this done at the clinic each month for 3 months. | $100/biopsy (total $300) |

| Sleep | Low | You will wear a sleep monitor on your wrist. The monitor fits like a watch. You will have to wear it every night for 30 days. The monitor must be charged every day. | $80 |

| Sleep | High | You will spend the night in a clinic for a sleep study. During the visit, a staff member will attach tubes and wires on top of your skin. This is done so that body activities can be measured while you sleep. You will probably lose several hours of sleep during the visit. | $200 |

A final consideration was to select a population of interest and define a total number of participants required to test all vignettes (both high and low versions) across a representative range of incentives offering amounts designed to match each vignette domain. For generalizability, we wanted to ensure a reasonable representation of study participants based on common diversity criteria, including by gender (male, female, other), race (White, Black, other), and self-reported household income (< $65K, > $65K). We chose a nominal target of at least 10 participants to create a probability of participation at any given offered compensation amount for any given vignette descriptor (Figure 1) and tried to balance the invitation of participants in a manner that ensured we were representing race, gender, income in all price levels in all vignettes.

To reduce the number of overall participants needed to help inform our study, we presented each participant with all five vignette scenarios in random order, ensuring that all were drawn from either the ‘low’ or ‘high’ domain version for any given participant. Thus, the design treated risk/burden as a between-subjects variable while type of vignette was a within-subjects variable.

Given we were looking for coarse separation statistics and participation prediction directionality rather than fine-grain planning estimates, we chose to calculate and offer 11 discrete price points for each vignette domain area (regardless of low/high variation), using a simple linear formula to calculate offered price points where price point 1 (PP1) was $0 and price point 11 (PP11) was $Max (determined by doubling the reasonable amount for each high risk/burden vignette, as suggested by coordinators and recorded in Table 1), with each of the intermediate price points calculated using the simple equation: PPN = (N-1) * $Max / 10.

To ensure representation of the various demographic combinations, we created a lookup table structure coded to include each desired representation permutation (female, male, other | Black, White, other | low-income, high-income, no answer-income), then generated permutation representation for our target pool of potential participants. Next, we wrote an R-script to create vignette high/low representation (alternating low/high for each full demographic profile, using the permutations noted above, to ensure balanced representation across demographics as the study progressed), randomized ordering (sampling from 1–5 with no replacement), and per-vignette price-point randomization (random sampling bin from 1–11 with no replacement) with full assignment and recording for each future participant represented in the randomization lookup table. This lookup table was consulted programmatically within REDCap after demographics were collected on screen 1 of the Vignette Experiment to provide: 1) participant-specific high/low classification for use across all five offered vignette domains; 2) randomized presentation ordering of vignette domains; and finally, individual offering prices for use after presentation of a specific vignette. Once a specific demographic permutation was used, the action was recorded so that the ‘next participant with this demographic profile’ was assigned a new ordering + price point set of permutations. Thus, each participant received a “personalized” random order of vignettes.

For deployment of the Vignette Experiment, we extended basic functionality of REDCap to perform special randomization functionality specific to the goals of this project. Extended functionality included storage and utilization of the pre-prepared lookup table used to inform vignette presentation order and per-participant incentive amounts for each vignette. The External Module code is available in GitHub.35

For each vignette, survey respondents were presented with an incentive amount as described above and first asked to indicate whether they would participate in the study (yes/no) and rate the amount of burden (time/effort) to join the study (scale: 1 not at all a burden – 5 an extremely large burden). Next, we asked them to rate the amount of perceived discomfort or inconvenience associated with participation in the study (scale: 1 not at all bad – 5 extremely bad); this was the same question asked in the Anchoring Survey. We used this data to anchor the abstract mean score for each vignette to the ratings of a real-life event from the Anchoring Survey. Our analysis identified the items that Anchoring Survey respondents rated closest (above and below) to the mean score found in the Anchoring Survey.

We also asked respondents to select from a pre-selected set of options the biggest perceived risk for taking part in the study (see Appendix B for response options), where available options included appropriate and inappropriate choices for each vignette to estimate respondents’ ability to discern the most significant risk in each scenario. During analysis, we coded these responses for each vignette correct, incorrect, or whether the respondent checked the no risk category. Finally, we asked them to rate how bad the biggest risk they selected was (scale: 1 not at all bad – 5 extremely bad) and rate the likelihood of the biggest risk they selected happening (scale: 1 not at all likely – 5 extremely likely).

We estimated that the survey would take approximately 10 minutes to complete. After completing the survey, respondents also had the option to enter their names into a drawing for a $50 Amazon gift card, with 15 participants selected at random to receive a gift card.

Data analysis:

For the Anchoring Survey, the sample size of 600 was intended to include approximately 50 responses in each of the eight potential demographic combinations (male or female; age ≤ 40 or > 40; race White or African American); while we sought responses from all race and ethnicity groups available in ResearchMatch, we did not include a specific sample target for the others beyond these two. We employed descriptive statistics to summarize characteristics for each of the 68 negative life events (mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum). To assess individual item bias by the five demographic variables, we employed non-parametric tests to look at all the items at once, as many of the items were not normally distributed. To evaluate differences in total item means based on demographics, we conducted one-way ANOVA. We used a Bonferroni corrected threshold for significance of p < 0.00014 (0.05/(68*5)).

The sample size for the Vignette Experiment was designed to provide a minimum of 10 participants per price point cell for each low- and high- risk/burden vignette. Given participants were randomized to receive either all low- or all high- risk/burden vignettes with randomized price points for each of the presented vignettes, we realized the randomization process could lead to some imbalance in individual price points as the study progressed. Given this, we doubled our recruitment target goal to sample 440 participants (20 participants * 11 Price points * 2 Burden Levels).

The primary null hypothesis was that there is no statistically significant association between offered financial incentive and self-reported willingness to participate in the study. For the univariate analysis, a chi-square test was used for the nominal variables, a chi-square for a trend was used for the ordinal variables.

Loess smoothed curves were used to examine the effect of incentive amount on study participation rate for each vignette type and vignette level of risk/burden. Logistic regression models were used to assess the impact of factors on participation in a study for each of the five vignettes. The factors included in each model were vignette level, price, race, income, gender, and age. Odds ratios were computed to display the likelihood of participating in various vignettes bases on these factors. Results from these models were used to determine the strongest drivers of participation within each vignette. Analyses were conducted with R (version 3.6.1) and IBM SPSS (version 26).

Results

Anchoring Survey

We sent a total of 17,235 invitations in waves to ResearchMatch volunteers, receiving 724 expressions of interest. From this pool, we received responses to the Anchoring Survey from 643 participants for a response rate of 89%; demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 2. For this framework proof of concept work in the Anchoring Survey, we were interested in broad representation of the general population rather than the ability to discern subpopulation differences.

Table 2:

Respondent demographic data, Anchoring Survey (n=643)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age | |

| 18–29 | 74 (11.5) |

| 30–49 | 242 (37.6) |

| 50–64 | 210 (32.7) |

| 65–74 | 75 (11.7) |

| 75 and older | 29 (4.5) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.2) |

| Missing | 12 (1.9) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 314 (48.8) |

| Male | 310 (48.2) |

| Other | 3 (0.5) |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (0.5) |

| Neither | 1 (0.2) |

| Missing | 12 (1.9) |

| Race/Ethnicity * | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 47 (7.3) |

| Asian or Asian American | 78 (12.1) |

| Black, African American, African | 211 (32.8) |

| Hispanic, Latino, Spanish | 46 (7.2) |

| Middle Eastern, North Africa | 7 (1.1) |

| Native Hawaiian, other Pacific Islander | 5 (0.8) |

| White, Caucasian | 281 (43.7) |

| None of these fully describe me | 30 (4.7) |

| Prefer not to answer | 16 (2.5) |

| Missing | 12 (1.9) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Grades 5 – 8 (Middle School) | 1 (0.2) |

| Grades 9 – 11 | 1 (0.2) |

| Grade 12 or GED | 48 (7.5) |

| College 1 – 3 years | 153 (23.8) |

| College 4 years or more | 207 (32.2) |

| Advanced degree | 217 (33.7) |

| Prefer not to answer | 4 (0.6) |

| Missing | 12 (1.9) |

| Household income | |

| Less than $10,000 | 27 (4.2) |

| $10,000 – $24,999 | 58 (9.0) |

| $25,000 – $34,999 | 63 (9.8) |

| $35,000 – $49,999 | 82 (12.8) |

| $50,000 – $74,999 | 119 (18.5) |

| $75,000 – $99,999 | 73 (11.4) |

| $100,000 – $149,999 | 92 (14.3) |

| $150,000 – $199,999 | 34 (5.3) |

| $200,000 or more | 20 (3.1) |

| Prefer not to answer | 63 (9.8) |

| Missing | 12 (1.9) |

Key:

numbers do not tally as participants were able to select more than one answer in this category

Almost all respondents (n=637, 99.1%) completed all 68 items on our negative life events survey; two respondents had no valid responses. As illustrated in Figure 2, mean participant responses to the 68 items indicated that participants were able to interpret and answer the questions in ways that distinguished the relative risk/burden of the items in an expected manner, as reflected in both directionality and smoothness of mean response rate. Examples of the events with highest-rated risk/burden (mean±SD)) included “losing your home in a fire” (4.72±0.68), “getting into a major car accident (with injuries)” (4.5±0.76), and “not having enough money to pay for housing” (4.47±0.79). Items rated in the mid-range for risk/burden (mean±SD) included “having stitches done” (2.43±1.01), “getting sick with a cold” (2.37±0.88) and “having a family member with minor health problems” (2.34±0.89). Examples with the lowest-rated risk/burden (mean±SD) included “taking out the trash” (1.14±0.44), “having an eye exam” (1.14±0.46), and “having your blood pressure taken (1.13±0.51).

Figure 2: Participant ratings for negative life events.

The rating scale for these events ranged from 1, not at all bad, to 5, extremely bad. Dots represent mean rating for each item, with bars illustrating the standard deviation.

We saw few differences in responses across demographic stratification variables. We found no significant differences in total item mean scores by sex (F(1, 623)=0.192, p=0.662), income (F(8, 567)=1.951, p=0.051), or age (F(4, 625)=2.012, p=0.091). After removing the two lowest categories of education, with one respondent each, results indicated that those with some college tended to rate items as more stressful (mean 2.51) compared to those reporting an advanced degree (mean 2.37, p=0.012). In a subgroup analysis by race (which combined respondents selecting more than one category (n=78) into a new single multiracial category, and excluded those who selected “None of these fully describe me” or “Prefer not to answer”), we found that Black respondents rated items as more stressful (mean 2.53) compared with White respondents (mean 2.35, p=0.001).

Vignette Experiment

We sent a total of 10,001 invitations in waves to ResearchMatch volunteers, receiving 579 expressions of interest. From this pool, we received responses to the Vignette Experiment from 534 participants, for a response rate of 92%; Table 3 summarizes the demographics of this sample. Table 4 shows the results based on participants’ responses to each vignette. The results are presented in the low and high risk/burden pairs of vignettes. Overall, these results were concordant with expected directionality. The presented average dollar incentive for each pair of vignettes was equivalent as designed.

Table 3:

Respondent demographic data, Vignette Experiment (N=534)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age (534 responses) | |

| 18–29 | 98 (18.4) |

| 30–49 | 131 (24.5) |

| 50–64 | 124 (23.2) |

| 65–74 | 138 (25.8) |

| 75+ | 39 (7.3) |

| Prefer not to answer | 4 (1) |

| Sex (534 responses) | |

| Female | 295 (55.2) |

| Male | 235 (44.0) |

| Neither | 3 (0.6) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.1) |

| Race/Ethnicity (534 responses) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (0.2) |

| Asian or Asian American | 1 (0.2) |

| Black, African American, or African | 163 (30.5) |

| Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish | 11 (2.1) |

| Middle Eastern or North African | 1 (0.2) |

| White or Caucasian | 346 (64.8) |

| None of these fully describe me | 7 (1.3) |

| Prefer not to answer | 4 (0.7) |

| Education (534 responses) | |

| Grades 9–11 | 4 (0.7) |

| Grade 12 or GED | 25 (4.7) |

| College 1–3 years | 170 (31.8) |

| College 4 years or more | 169 (31.6) |

| Advanced degree | 163 (30.5) |

| Prefer not to answer | 0.01 (3) |

| Income (533 responses) | |

| <$35,000 | 128 (24.0) |

| $35,000–$64,999 | 127 (23.8) |

| $65,000 – $99,999 | 125 (23.5) |

| >$100,000 | 115 (21.6) |

| Prefer not to answer | 38 (7.1) |

Table 4:

Overall Vignette Experiment results

| Vignette description (risk/burden level) | % would agree to participate | Mean price among patient agreeing to participate | Mean burden (1=not at all – 5 extremely large) | % correctly identified biggest risk of vignette | % reporting no risk | Mean how bad the specific risk is (1=not at all – 5 extremely bad) | Mean likelihood that risk could happen (1=not at all – 5 extremely likely) | Mean unpleasant (1=not at all – 5 extremely bad) | Most similar common negative event(s) from Anchoring Survey (mean rating) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a. Spend a night in sleep clinic, get wires attached, lose several hours of sleep (high risk/burden) | 82% ns | $204 ns | 2.16 *** | 30% Large loss of sleep | 18% | 1.87 ns | 3.09 *** | 1.95 *** | Thirsty for an hour (1.91); having a dry mouth (1.81) |

| 1b. Wear a sleep monitor on wrist for 30 days and charge it daily (low risk/burden) | 87% | $206 | 1.70 | 21 % A little loss of sleep | 71% | 1.76 | 2.39 | 1.44 | Finger stick for blood by nurse (1.41), getting a flu vaccine injection (1.47) |

| 2a. Take a safe drug twice a day for a month, probably feel very nauseated (high risk/burden) | 39% *** | $348 ns | 2.98 *** | 83 % Upset stomach | 7% | 3.10 *** | 3.60 *** | 3.13 *** | Not being able to get a loan/credit (3.12); Missing an important meeting (3.27) |

| 2b. Take a safe drug daily for a week, may have minor dry mouth as a side effect (low risk/burden) | 81% | $336 | 1.68 | 78 % Dry mouth | 16% | 1.80 | 2.63 | 1.78 | Getting bitten by a mosquito, (1.76); being woken before your alarm went off (1.81) |

| 3a. Cut into thigh muscle, very painful and will scar, at clinic monthly for 3 months (high risk/burden) | 27% *** | $350 ns | 3.39 *** | 74 % A lot of pain | 5% | 3.36 *** | 3.83 *** | 3.46 *** | Having severe nausea (3.35); breaking your arm (3.75) |

| 3b. Blood drawn from the arm once a month for 3 months. May have a little pain (low risk/burden) | 84% | $327 | 2.04 | 57 % A little pain | 36% | 1.56 | 2.42 | 1.73 | Getting a paper cut (1.73); getting bitten by a mosquito (1.76) |

| 4a. Keep notes of sexual and drug activities for 3 months. Discuss with staff at clinic monthly (high risk/burden) | 62% *** | $90 p=0.04 | 2.23 ** | 40% Feeling judged or awkward | 53% | 2.21 *** | 2.59 ns | 1.89 *** | Being thirsty for an hour (1.91); filling out forms for 30 min (1.85) |

| 4b. Keep a daily record of how much water you drink for one week. Discuss with staff at clinic once (low risk/burden) | 83% | $80 | 1.91 | 5% Feeling judged or awkward | 90% | 1.52 | 2.13 | 1.48 | Having blood taken by a finger stick by a nurse (1.41), having blood drawn from your arm by a nurse (1.49) |

| 5a. 3 CT Scans every 4 months for one year at clinic. Same radiation as people get in 5 years. (high risk/burden) | 50% *** | $176 ns | 2.51 *** | 0.50 Too much radiation | 15% | 2.86 *** | 3.36 *** | 2.27 *** | Having trouble making a decision (2.26); too many things to do (2.33) |

| 5b. One clinic visit for one chest x-ray. Very low radiation (low risk/burden) | 85% | $174 | 1.70 | 0.58 A little radiation | 27% | 1.61 | 2.71 *** | 1.47 | Having blood taken by a finger stick by a nurse (1.41), having blood drawn from your arm by a nurse (1.49) |

| Mean, all 5 high risk/burden vignettes | 52% *** | $209 ns | 2.65 | NA | 20% | 2.75 | 3.38 | 2.54 | Being hungry for a day (2.54); having minor surgery (2.48) |

| Mean, all 5 low risk/burden vignettes | 84% | $224 | 1.81 | NA | 48% | 1.67 | 2.56 | 1.58 | Feel hot for a brief time (1.69); completing a food diary for a week (1.52) |

Note: significance testing compared high and low risk/burden versions of the vignettes

p <0.01

p<0.001

ns not statistically significant p>0.05; NA not applicable

We expected that a higher percentage of respondents would agree to participate in the low risk/burden vignette than the high one (Figure 1). This expectation was confirmed for all the vignettes except for the vignette dealing with sleep, for which a similar proportion of participants indicated willingness to participate for both the high- and low- risk/burden version of this vignette.

Among mean rating of risk/burden each respondent provided for each vignette, all the high vignettes were rated as significantly higher in risk/burden than the low vignettes. Mean ratings of how bad the risk/burden was perceived were significantly different for all vignettes between the low- and high-risk/burden version, with the exception of the sleep vignettes.

We asked respondents to identify from the list which was the biggest risk in taking part in the study. Vignettes appeared less successful in communicating the type of risk to the respondent; a large percentage of respondents reported no risk, though the vignettes each included some amount of risk. In all vignettes, however, the percentage of respondents stating “no risk” percentage was significantly lower in the lower risk/burden vignettes, with the exception of the sleep vignette.

All the high risk/burden vignette risks were rated as more likely to occur than the low risk event, except for the keeping notes vignette, for which the low and high risk events were rated as similarly likely to occur. As expected, respondents thought that the high risk/burden vignettes were more unpleasant (bad) than the low vignettes.

To aid in framing the risk/burden of the vignettes, we analyzed similarities between the ratings of unpleasantness provided in the Vignette Experiment with the data collected in the Anchoring Survey, comparing the average rating from the Vignette Experiment with the nearest lower and higher rating from the Anchoring Survey. The vignette with the highest negative value was cutting a muscle causing a lot of pain monthly for three months. Participants’ mean rating of the risk/burden of this vignette compares with the events in the Anchoring Survey of breaking your arm or severe nausea. This vignette also had the lowest volunteering rate (27%). The mildest vignette was wearing a sleep monitor on your wrist for 30 days and charging every day. This had the highest volunteering rate of 87%. Participants’ mean rating of the risk/burden of this vignette was comparable to events in the Anchoring Survey of getting a flu shot or a finger stick for a blood draw. In summary, the data strongly confirm our design that the high risk/burden vignettes be perceived as more burdensome, riskier, and unpleasant than the low risk/burden vignettes.

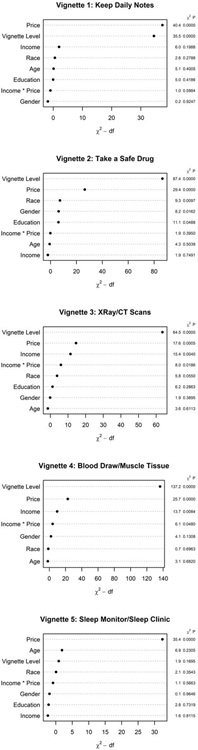

Logistic regression models assessing the relative influence of various independent variables on study participation showed that in every case, with the exception of the sleep study, vignette risk/burden level (high/low) had the strongest effect on odds of participation. Figure 3 illustrates the adjusted effects, including directionality and effect size, of each subject level predictor on odds of participation for each vignette. In every vignette, the incentive price point offer was also important in decision making regarding study participation. Considering the demographic variables, males and African Americans were more prone to agree to participate in a drug study, as compared with females and non-African American respondents. Other than those observations listed above, we saw no differences in predictive power by gender, race, age, or income level.

Figure 3: Predicting study participation by vignette.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from logistic regression models are illustrated for various factors affecting study participation in each vignette.

Complementing the analysis of directionality and effect size represented in Figure 3, Figure 4 illustrates the most important drivers of participation within each vignette. The figure includes the highest ranked factors at the top of each graph, with those below reflecting decreasing order of rank to indicate relative weight on participant decision making. Incentive amount and vignette risk level (high/low) were the most influential drivers of participation in all vignettes, with the exception of the sleep study. In the sleep vignette, incentive price predominated over all other factors; in this vignette type, age was the second most important driver, and risk was the third in importance. Overall, we did not find interaction between price and self-reported income to be a key factor in decision to participate.

Figure 4: Key drivers of participation in each vignette.

The panels illustrate the relative importance of factors associated with participation for each vignette as measured by logistic regression model chi-square statistic. The left y axis indicates the variables of interest; the x axis indicates the importance of the variable based on the chi-square minus degrees of freedom (df); and the right y axis indicates the chi-square p values.

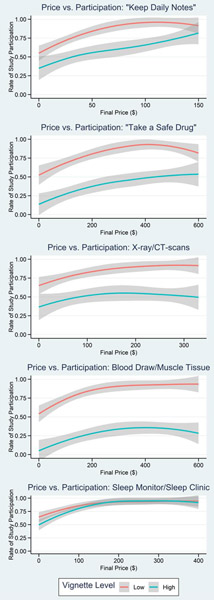

Figure 5 illustrates the effect of incentive price on participation by high/low vignette level, showing a gradual increase in participation with increasing price point for all vignettes. We observed generally lower participation for all high-risk vignettes with the exception of sleep, which approached 100% at upper price bounds for both vignette risk levels. For the low risk/burden vignettes, likelihood of participation approached 100% toward the upper bounds of final price in all vignettes. In the high risk/burden vignettes, at upper bounds of final price the likelihood of participation approached 50% for the drug and the CT vignettes, 25% for the muscle biopsy scenario, and 75% for the diary.

Figure 5: Effect of price on participation, high vs. low vignette level.

Loess smoothed curves illustrate the effect of incentive amount (Final Price) on study participation rate for each vignette type and vignette level.

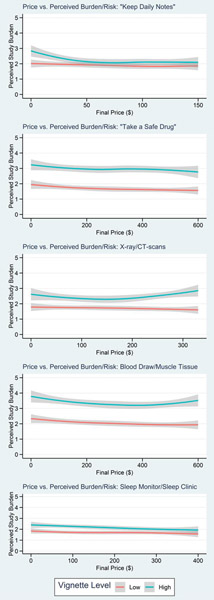

Figure 6 shows the effect of incentive price on risk perception by high/low vignette level, indicating no notable effects of price on perceived risk/burden of the vignettes with the high risk version of each vignette perceived as higher risk/burden even as price increased.

Figure 6: Effect of price on perceived risk, high vs. low vignette level.

Loess smoothed curves illustrate the effect of incentive amount on perceived study risk/burden for each vignette type and vignette level.

Discussion

In this two-component project, we demonstrated that we are able to create and test an approach for contextualization of risk to aid in the determination of the amount of financial incentive appropriate for various study characteristics. By combining participant ratings of negative life events in the Anchoring Survey with more granular participant assessment of risk and financial incentives specific low and high risk/burden research scenarios in the Vignette study, we have developed a methodology and framework that, when further refined, can be used to inform participant compensation advice for new studies. This framework for assessment of financial incentives related to risk/burden level could thus be a powerful tool for the Recruitment Innovation Center and others advising clinical trial investigators on participation incentive amounts for specific studies and research populations. Use of this framework to gather information directly from potential participants related to specific clinical trials will allow us and other investigators to design study-specific approaches to incentives that demonstrate an intentional approach to respect for participant perspectives and for the value that they contribute by participating in a trial.

The data yielded by the Anchoring Survey made us confident in our ability to ask questions appropriately and gather information from a sample similar to potential research participants based on perception of risk/burden. Given the organization of mean participant ratings corresponding with the wide range of negative life events, the Anchoring Survey results helped us understand and contextualize responses in the Vignette Experiment.

We noted some significant differences in ratings of burden between categories based on demographics, for example the effects of race and sex on ratings within the drug vignette experiment. While our study was not powered to detect overall subgroup differences, we were successful in achieving reasonable representation of key demographic characteristics.

Results of the Vignette Experiment showed the expected directionality of participant rating of risk/burden in all cases. Price (i.e., financial incentive amount) and vignette risk/burden level were key drivers of respondents’ agreement to participate in four of the five vignettes, supporting our belief in the important connection between these two characteristics in the overall path to recruitment success. The general preference for higher amounts of financial incentive is concordant with other assessments of participant decisions related to hypothetical research scenarios.9,17,36 Further, we note that results suggested that increasing amount of financial incentives did not unduly sway participants toward agreeing to participate in a hypothetical studies with disregard for risk level, as the overall rate of participation was noticeably lower for the high vs. low risk scenario, even at the highest incentive amount, for four of the vignettes.

A concern raised by the use of financial incentives for trial participation has been that large incentives could potentially provide undue influence to participate even when a trial was not in the best interest of an individual.24,37 We did not see evidence of undue influence in responding to any of our vignettes. Specifically, we found no relationship between the size of incentive and ratings of risk/burden or interaction of income and incentive with stated willingness to participate. Further, this data suggests that participant income was not the main driver of willingness to participate in the various vignettes at the assigned price points. These findings are concordant with our previous exploration of “return of value” as an approach to recognizing and respecting the contributions of research participants, which found that financial incentives were valued but consistently ranked below other potential research benefits from all demographic subgroups.11

Mean ratings of perceived risk/burden were significantly different between the high and low risk vignette versions for four of the five vignettes, suggesting that participants were able to differentiate overall risks. The analysis did, however, detect some noise in participants’ selection of the biggest risk for each vignette, with lower than anticipated proportions of respondents selecting the correct risk for many of the vignettes. Some have suggested previously that many participants may not understand the risks of studies, in proportions roughly similar to those we observed in the current work. For example, a review of 23 studies found that in 14 studies, less than 50% of the participants could identify risks or side effects.38 In an interview study with input from 155 participants in 40 different clinical trials, almost 25% reported no risks or disadvantages to study participation despite being explicitly asked about these issues.39 It is also possible that this represents survey fatigue, suggesting that in future implementations of the framework we will need to further explore these issues.

Participant responses to the sleep study were noticeably different than the other vignettes, with no signal related to participation or unpleasantness for high vs. low risk and other similarities suggesting that participants perceived negligible differences between the two versions of this scenario. This may be attributable to not enough distinction between the high and low risk study activities, generally low perception of risk related to the sleep vignette activities, or other nuances in the way participants perceive risk related to this kind of research. For example, previous research into participant opinions regarding sleep study procedures indicates some conflicting data, finding preference for wearable monitors over lab sleep studies among some,40 while others express concern about potential discomfort with actigraphy and the accuracy of its data.41 Future work that evaluates participant preferences in the context of specific “real world” research studies will facilitate deeper understanding of factors driving participation in studies involving sleep-related procedures.

While a previous study exploring participant perceptions of hypothetical research scenarios found that increasing the amount of financial incentive seemed to lead to increased perception of risk and associated vigilance,19 our analysis did not reveal a notable effect of increasing price on increasing perception of risk, suggesting that this important issue remains open for further research.

Limitations

We acknowledge several limitations of the current work. Response rates were low, though similar to other online surveys using ResearchMatch and other similarly broad invitation measures.42–45 We are also unable to assess how well the results of the vignette responses will translate to real-world decision making. For example, behavioral economics theory suggests that survey research offering a set of alternatives, such as we did with these experimental vignettes, can result in ‘hypothetical bias,’ in which preferences expressed in the survey do not accurately reflect real-life choices.46 While there are great advantages to using real life studies as used by Halpern et al.,9, in contrast to vignettes, there are also major logistic and cost issues in implementing what has been called Study Within A Trial (SWAT) method; these methods are being refined and may present a more practical option in the future.47 Response to a hypothetical scenario may be different from a participant’s judgment of risk/burden when considering enrollment in a real-world study, where a more complex decision will involve additional details such as study purpose, multiple procedures, and other context.

Moreover, internal motivators among participants such as altruism may be more powerful than money in driving research participation, so an extrinsic incentive such as monetary compensation could unintentionally backfire by decreasing intrinsic motivation. A financial payment could also decrease the perceived pro-social value of volunteering, as potential participants may believe their ‘good deed’ is devalued by accepting a cash reward.48 For this study, we believe offering of a minor financial incentive in our surveys, in the form of a chance to win a gift card, introduced minimal bias related to incentives but we cannot rule out some effects on results.

The community from which our survey populations were drawn may have introduced selection bias. ResearchMatch participants are very likely to think favorably about biomedical research and are more likely to be familiar with requests to participate in studies based on information similar to what the vignettes provided. Our sample also was weighted toward higher education levels, though our methods for optimizing readability and simplifying choice options likely minimized the impact of this factor. While ResearchMatch also includes both healthy volunteers and individuals reporting various medical conditions, we did not query participants’ medical status during the invitation process, and thus cannot assess any differences between groups by condition. Further work in the context of specific studies will explore these issues. Given that the purpose of this study was to develop a framework and not necessarily to find optimal compensation amounts for generalized study components, we felt the risk of selection bias issues was minimal.

Respondents in the Anchoring Survey may have also been asked to participate in the Vignette Experiment. We considered this risk but decided not to exclude Anchoring Survey participants from being invited to the Vignette Experiment, as the questions asked in the second survey were significantly different and there was a reasonable washout period between the surveys that reduced any likelihood of Anchoring Survey participants remembering any detail of the questionnaire or study intentions.

Regarding sizing of financial incentives, we cannot distinguish between ‘near’ adjoining dollar amounts within the span of prices included. Here, we were looking first at distinguishing between low/high vignettes and between very small and very large (but realistic) dollar amounts for the same vignette. We focused on exploring the functional relationship between risk/burden and amount of financial incentive, rather than finding the “ideal” incentive amount for each type of research. Future work will need to further explore using this technique to make more precise estimates of appropriate financial incentives amount.

We also note missing data issues for unpleasantness variable in the vignettes, which affected a random proportion of the vignette responses due to a technical issue. Because of the way we designed operational components of the survey implementation, for any given vignette domain (high and low), about 20% of respondents were not asked the unpleasantness rating question; this was randomly distributed so represents a power issue but not a bias issue.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Our intent in this two-component study was to create a technically sound framework for finding specific patient populations and asking them to help inform participant financial incentives for a specific vignette. We established this framework and, using the experimental vignette method, demonstrated that these methods can distinguish between high/low risk and between vignette domain types, and discerned directionality of relationship between amount of financial incentive and willingness to participate. Future plans within the Recruitment Innovation Center are to apply this evidence-gathering tool in the context of a real-world study, including finding a representative study population, developing vignette components for that specific study, and exploring expected participation rate based on varying financial incentive. This will allow further refinement of the framework in support of helping research teams establish realistic financial incentives for any study and study population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We appreciate the thoughtful insights and feedback shared by the Recruitment Innovation Center Community Advisory Board (including ad hoc workgroup members Guadalupe Campos, Grant Jones, Steve Mikita, JD, and Danielle Pardue, JD) and the formatting and design assistance from Meredith O’Brien and Chad Lightner.

Funding:

This project was supported by award no. U24TR001579 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) and the National Library of Medicine (NLM). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of NCATS, NLM, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Carlisle B, Kimmelman J, Ramsay T, MacKinnon N. Unsuccessful Trial Accrual and Human Subjects Protections: An Empirical Analysis of Recently Closed Trials. Clin Trials. 2015. February;12(1):77–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stensland KD, McBride RB, Latif A, Wisnivesky J, Hendricks R, Roper N, Boffetta P, Hall SJ, Oh WK, Galsky MD. Adult Cancer Clinical Trials That Fail to Complete: An Epidemic? J Natl Cancer Inst [Internet]. 2014. September 1 [cited 2020 Jan 10];106(9). Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article/106/9/dju229/911080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Djulbegovic B, Kumar A, Soares HP, Hozo I, Bepler G, Clarke M, Bennett CL. Treatment success in cancer: new cancer treatment successes identified in phase 3 randomized controlled trials conducted by the National Cancer Institute-sponsored cooperative oncology groups, 1955 to 2006. Arch Intern Med. 2008. March 24;168(6):632–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soares HP, Kumar A, Daniels S, Swann S, Cantor A, Hozo I, Clark M, Serdarevic F, Gwede C, Trotti A, Djulbegovic B. Evaluation of new treatments in radiation oncology: are they better than standard treatments? JAMA. 2005. February 23;293(8):970–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahon E, Roberts J, Furlong P, Uhlenbrauck G, Bull J. Barriers to Clinical Trial Recruitment and Possible Solutions: A Stakeholder Survey [Internet]. 2015. [cited 2020 Jan 10]. Available from: http://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/barriers-clinical-trial-recruitment-and-possible-solutions-stakeholder-survey?pageID=2

- 6.Kim S-H, Tanner A, Friedman DB, Foster C, Bergeron C. Barriers to Clinical Trial Participation: Comparing Perceptions and Knowledge of African American and White South Carolinians. Journal of Health Communication. 2015. July 3;20(7):816–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Treschan TA, Scheck T, Kober A, Fleischmann E, Birkenberg B, Petschnigg B, Akça O, Lackner FX, Jandl-Jager E, Sessler DI. The Influence of Protocol Pain and Risk on Patients’ Willingness to Consent for Clinical Studies: A Randomized Trial. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2003. February;96(2):498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agoritsas T, Deom M, Perneger TV. Study design attributes influenced patients’ willingness to participate in clinical research: a randomized vignette-based study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011. January;64(1):107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halpern SD, Chowdhury M, Bayes B, Cooney E, Hitsman BL, Schnoll RA, Lubitz SF, Reyes C, Patel MS, Greysen SR, Mercede A, Reale C, Barg FK, Volpp K, Karlawish J, Stephens-Shields AJ. The Effectiveness and Ethics of Incentives for Research Participation: Two Embedded Randomized Recruitment Trials [Internet]. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network; 2020. October. Report No.: ID 3690899. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3690899 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Treweek S, Pitkethly M, Cook J, Fraser C, Mitchell E, Sullivan F, Jackson C, Taskila TK, Gardner H. Strategies to improve recruitment to randomised trials. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2018. [cited 2020 Jan 9];(2). Available from: 10.1002/14651858.MR000013.pub6/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkins CH, Mapes BM, Jerome RN, Villalta-Gil V, Pulley JM, Harris PA. Understanding What Information Is Valued By Research Participants, And Why. Health Affairs. 2019. March 1;38(3):399–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan EM, Bennett T, Gillies K. Assessing effective interventions to improve trial retention: do they contain behaviour change techniques? Trials. 2020. December;21(1):213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stunkel L, Grady C. More than the money: a review of the literature examining healthy volunteer motivations. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011. May;32(3):342–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelinas L, White SA, Bierer BE. Economic vulnerability and payment for research participation. Clinical Trials. 2020. June;17(3):264–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Largent EA, Lynch HF. Paying Participants in COVID-19 Trials. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020. July 6;222(3):356–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fogel DB. Factors associated with clinical trials that fail and opportunities for improving the likelihood of success: A review. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2018. August 7;11:156–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bentley JP, Thacker PG. The influence of risk and monetary payment on the research participation decision making process. J Med Ethics. 2004. June;30(3):293–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slomka J, McCurdy S, Ratliff EA, Timpson S, Williams ML. Perceptions of Financial Payment for Research Participation among African-American Drug Users in HIV Studies. J Gen Intern Med. 2007. October;22(10):1403–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cryder CE, John London A, Volpp KG, Loewenstein G. Informative inducement: study payment as a signal of risk. Soc Sci Med. 2010. February;70(3):455–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Breitkopf CR, Loza M, Vincent K, Moench T, Stanberry LR, Rosenthal SL. Perceptions of Reimbursement for Clinical Trial Participation. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2011. September;6(3):31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jansen LA, Wall S. Reconsidering paternalism in clinical research. Bioethics. 2018;32(1):50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walter JK, Burke JF, Davis MM. Research participation by low-income and racial/ethnic minority groups: how payment may change the balance. Clin Transl Sci. 2013. October;6(5):363–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Devine EG, Knapp CM, Sarid-Segal O, O’Keefe SM, Wardell C, Baskett M, Pecchia A, Ferrell K, Ciraulo DA. Payment expectations for research participation among subjects who tell the truth, subjects who conceal information, and subjects who fabricate information. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015. March;41:55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grady C, Dickert N, Jawetz T, Gensler G, Emanuel E. An analysis of U.S. practices of paying research participants. Contemp Clin Trials. 2005. June;26(3):365–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menikoff J Just compensation: paying research subjects relative to the risk they bear. Am J Bioeth. 2001;1(2):56–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones E, Liddell K. Should healthy volunteers in clinical trials be paid according to risk? Yes. BMJ. 2009. October 22;339:b4142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koen J, Slack C, Barsdorf N, Essack Z. Payment of trial participants can be ethically sound: moving past a flat rate. S Afr Med J. 2008. December;98(12):926–929. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009. April;42(2):377–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harris PA, Scott KW, Lebo L, Hassan N, Lightner C, Pulley J. ResearchMatch: a national registry to recruit volunteers for clinical research. Acad Med. 2012. January;87(1):66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Romano PS, Bloom J, Syme SL. Smoking, social support, and hassles in an urban African-American community. Am J Public Health. 1991. November;81(11):1415–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanner AD, Coyne JC, Schaefer C, Lazarus RS. Comparison of two modes of stress measurement: daily hassles and uplifts versus major life events. J Behav Med. 1981. March;4(1):1–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atzmüller C, Steiner PM. Experimental vignette studies in survey research. Methodology: European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences. 2010;6(3):128–138. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Home - ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. [cited 2018 Nov 20]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/

- 34.Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University Institutional Review Board. Guidelines for compensation of research subjects [Internet]. Available from: https://www.einstein.yu.edu/docs/administration/institutional-review-board/policies/Compensation.pdf

- 35.Vanderbilt REDCap Group. vanderbilt-redcap/survey_randomization [Internet]. 2019. [cited 2019 Nov 15]. Available from: https://github.com/vanderbilt-redcap/survey_randomization

- 36.What do patients value as incentives for participation in clinical trials? A pilot discrete choice experiment - Akke Vellinga, Colum Devine, Min Yun Ho, Colin Clarke, Patrick Leahy, Jane Bourke, Declan Devane, Sinead Duane, Patricia Kearney, [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 13]. Available from: 10.1177/1747016119898669 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Largent EA, Lynch HF. Paying Research Participants: The Outsized Influence of “Undue Influence.” IRB. 2017;39(4):1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mandava A, Pace C, Campbell B, Emanuel E, Grady C. The quality of informed consent: mapping the landscape. A review of empirical data from developing and developed countries. J Med Ethics. 2012. June;38(6):356–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lidz CW, Appelbaum PS, Grisso T, Renaud M. Therapeutic misconception and the appreciation of risks in clinical trials. Soc Sci Med. 2004. May;58(9):1689–1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garg N, Rolle AJ, Lee TA, Prasad B. Home-based diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in an urban population. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014. August 15;10(8):879–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith MT, McCrae CS, Cheung J, Martin JL, Harrod CG, Heald JL, Carden KA. Use of Actigraphy for the Evaluation of Sleep Disorders and Circadian Rhythm Sleep-Wake Disorders: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and GRADE Assessment. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018. 15;14(7):1209–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giuse NB, Koonce TY, Kusnoor SV, Prather AA, Gottlieb LM, Huang L-C, Phillips SE, Shyr Y, Adler NE, Stead WW. Institute of Medicine Measures of Social and Behavioral Determinants of Health. Am J Prev Med. 2017. February;52(2):199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.A very low response rate in an on‐line survey of medical practitioners. [cited 2021 Jul 13]; Available from: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00232.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Batty GD, Gale CR, Kivimäki M, Deary IJ, Bell S. Comparison of risk factor associations in UK Biobank against representative, general population based studies with conventional response rates: prospective cohort study and individual participant meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020. February 12;368:m131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davis AM, Hanrahan LP, Bokov AF, Schlachter S, Laroche HH, Waitman LR, GPC Height Weight Research Team. Patient Engagement and Attitudes Toward Using the Electronic Medical Record for Medical Research: The 2015 Greater Plains Collaborative Health and Medical Research Family Survey. JMIR Res Protoc. 2019. March 12;8(3):e11148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.behavioralecon. Preference [Internet]. behavioraleconomics.com | The BE Hub. [cited 2020 Jan 9]. Available from: https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/resources/mini-encyclopedia-of-be/preference/ [Google Scholar]

- 47.Treweek S, Bevan S, Bower P, Briel M, Campbell M, Christie J, Collett C, Cotton S, Devane D, El Feky A, Galvin S, Gardner H, Gillies K, Hood K, Jansen J, Littleford R, Parker A, Ramsay C, Restrup L, Sullivan F, Torgerson D, Tremain L, von Elm E, Westmore M, Williams H, Williamson PR, Clarke M. Trial Forge Guidance 2: how to decide if a further Study Within A Trial (SWAT) is needed. Trials. 2020. January 7;21(1):33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.behavioralecon. Incentives [Internet]. behavioraleconomics.com | The BE Hub. [cited 2020 Jan 9]. Available from: https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/resources/mini-encyclopedia-of-be/incentives/ [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.