Abstract

Background:

To assess GABAA receptor subtypes involved in benzodiazepine tolerance and dependence, we evaluated the ability of subtype-selective and non-selective ligands to substitute for (i.e., produce “cross-tolerance”) or precipitate withdrawal during chronic alprazolam treatment.

Methods:

Four female rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) were implanted with chronic intravenous catheters and administered alprazolam (1.0 mg/kg every 4 h). Following 14+ days of chronic alprazolam, acute administration of selected doses of non-selective and subtype-selective ligands were substituted for, or administered with, alprazolam, followed by quantitative behavioral observations. The ligands included alprazolam and midazolam (positive modulators, non-selective), zolpidem (positive modulator, preferential affinity for α1-containing GABAA receptors), HZ-166 (positive modulator, preferential efficacy at α2- and α3-containing GABAA receptors), and βCCT (antagonist, preferential affinity for α1-containing GABAA receptors).

Results:

Acutely, alprazolam and midazolam both induced observable ataxia along with a mild form of sedation referred to as “rest/sleep posture” at a lower dose (0.1 mg/kg, i.v.), whereas at a higher dose (1.0 mg/kg, i.v.), induced deep sedation and observable ataxia. With chronic alprazolam treatment, observable ataxia and deep sedation were reduced significantly, whereas rest/sleep posture was unchanged or emerged. Zolpidem showed a similar pattern of effects, whereas no behaviors engendered by HZ-166 were changed by chronic alprazolam. Administration of βCCT, but not HZ-166, resulted in significant withdrawal signs.

Conclusions:

These results are consistent with a role for α1-containing GABAA receptor subtypes in tolerance and dependence observed with chronic alprazolam, although other receptors may be involved in the withdrawal syndrome.

Keywords: Benzodiazepine, Tolerance, Dependence, Alprazolam, GABAA Subtype, Primate

1. Introduction

Considerable preclinical and clinical research has established that chronic exposure to benzodiazepines (BZs) results in both tolerance to the effects of the drugs, as well as the development of physical dependence, as defined by the appearance of withdrawal signs following treatment stoppage or administration of an antagonist (for reviews, see Griffiths and Weerts 1997; Licata and Rowlett 2008). The withdrawal syndrome that defines BZ dependence symptomatically is not considered life threatening; however, it is a clinically significant event that likely contributes to maintenance of BZ misuse and related use disorders (Griffiths and Weerts 1997; O’Brien 2005). Although tolerance and dependence are significant impediments to BZ therapy and likely are major contributors to misuse and abuse of BZs, the pharmacological and molecular basis of these phenomena remain poorly understood (cf. Wafford 2005; Licata and Rowlett 2008; Gravielle 2016).

We have developed procedures in rhesus monkeys to provide reliable metrics for drug-induced behaviors as well as alteration of species-typical behaviors by drugs (Duke et al., 2018; 2020; Huskinson et al., 2020). Applying these procedures to BZ pharmacology, we found that by parsing out sedative effects based on reaction to stimuli and arousal, a relatively mild form of sedation (rest/sleep posture) appeared to involve α2 and/or α3 subunit-containing receptors (α2GABAA, α3GABAA), whereas the most robust form of sedation (deep sedation) primarily involved α1GABAA receptors (Duke et al. 2018). These results support the idea that a combination of quantitative observation and rigorous pharmacological approaches may help inform knowledge about GABAA receptor mechanisms underlying clinically relevant effects of BZs and related compounds.

As a follow-up study to our investigation of acute behavioral effects of BZs, we established a rhesus monkey model of BZ-induced tolerance and physical dependence (Duke et al., 2020). In this study, chronic treatment with alprazolam (6 mg/kg/day, 1 mg/kg/4 h) resulted in rapid tolerance to some behaviors (e.g., deep sedation) but no tolerance to others (e.g., rest/sleep posture). Physical dependence was observed via both spontaneous and precipitated withdrawal, the latter by administering the BZ-site antagonist, flumazenil. Collectively, these findings with acute treatments and chronic alprazolam suggest rapid tolerance to α1GABAA receptor subtype-mediated effects, whereas α2/3GABAA subtype-mediated effects showed tolerance at a slower rate, if at all. However, the study by Duke et al. (2020) did not address these hypotheses more directly, e.g., by evaluating the extent to which compounds with subtype selectivity would engender similar tolerance patterns (or lack of tolerance patterns) as alprazolam.

With respect to physical dependence, using an acute dependence model in squirrel monkeys, Fischer et al. (2013) demonstrated that an injection of a relatively large dose of the α1GABAA subtype-preferring ligand, zolpidem, resulted in physical dependence-like behavior (i.e., flumazenil suppression of food-maintained operant responding), whereas doses of the α2/3GABAA subtype-preferring ligand, HZ-166, did not engender this effect. Moreover, administration of the α1GABAA subtype-preferring antagonists, βCCT and 3-PBC, induced evidence of precipitated withdrawal following treatments with a relatively high dose of zolpidem (Fischer et al., 2013). These data suggest an association between α1GABAA subtypes and BZ-induced physical dependence, at least under conditions of an acute administration of a positive modulator.

The overall goal of the present study was to evaluate the hypothesis that behavioral effects of BZs associated with α1GABAA receptor subtypes (i.e., associated with α1GABAA-preferring, but not α2/3GABAA-preferring modulators; blocked by βCCT), but not α2/3GABAA subtypes (i.e., associated with α2/3GABAA-preferring but not α1GABAA-preferring modulators; not blocked by βCCT) demonstrate tolerance following chronic alprazolam treatment, and that withdrawal-associated behaviors are associated specifically with the α1GABAA receptor subtype (i.e., can be precipitated by βCCT treatment). Using the rhesus monkey model established by Duke et al. (2020), we conducted two types of studies in non-dependent and dependent monkeys: “tolerance/cross-tolerance” studies, in which one of the daily infusions of alprazolam was replaced with a test drug/compound, and “precipitated withdrawal” studies, in which the test drug/compound was administered following a daily alprazolam infusion. Drugs or compounds with selectivity for α1GABAA or α2/3GABAA subtypes were administered using both approaches and at selected doses. Tolerance and withdrawal were assessed using the modified frequency scoring system and withdrawal sign scoring system, respectively, as described by Duke et al. (2018; 2020).

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects and surgery

Four adult female rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) weighing between 6 and 9 kg were housed in individual home cages under free-feeding conditions prior to the study, and during the study had access to food for 1 h in the AM and 1 h in the PM. Water was available ad libitum. All monkeys participated in the experiments described in Duke et al (2020). Rooms were maintained on a 12-h light/12-h dark schedule (lights on at 0630 h). Animals in this study were maintained in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th ed, 2011). Research protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Harvard Medical School.

Monkeys were prepared with chronic indwelling venous catheters following the general surgical procedures described by Platt et al. (2011). The external end of the catheter was fed through a fitted jacket and tether system attached to a fluid swivel (Lomir Biomedical, Malone, NY) attached to the cages. The catheters were flushed daily with heparinized saline (100 IU/ml) and the exit site of the catheter was inspected routinely.

2.2. Drug preparation

The drugs used in this study were administered intravenously via syringe or syringe pump. The base forms of alprazolam (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), midazolam and zolpidem (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) were dissolved in propylene glycol (50–80%), ethanol (5–10%), and sterile water. HZ-166 (8-ethynyl-6-(2’-pyridine)-4H-2,5,10b-triaza-benzo[e]azulene-3-carboxylic acid ethyl ester; Knutson et al., 2020) and βCCT (β-carboline-3-carboxylate-tert-butyl ester) were synthesized at the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and dissolved in 20% ethanol, 60% propylene glycol, and 20% sterile water. Dose selection is described in detail below in Results. All drug solutions were filter-sterilized prior to infusion (0.2 μm pore syringe filters).

2.3. Observation procedures

The behavior of each monkey was scored using a focal animal approach as described in Platt and colleagues (2002) and modified for rhesus monkeys (see Rüedi-Bettschen et al. 2013; Duke et al. 2018; 2020; Huskinson et al. 2020). Briefly, a trained observer blind to the drug treatments observed a specific monkey for 5 minutes and recorded each instance that a particular behavior occurred during 15-second intervals. Scores for each behavior were calculated as the number of 15-second bins in which the behavior occurred (e.g., a maximum score would be 20). For sedation measures, structured exposure to stimuli were included in the observation sessions (Duke et al. 2018). When a monkey was observed to have closed eyes, an assessment of the animal’s responsiveness to the stimuli was determined. Specifically, the observer presented three stimuli: 1) walked at a normal pace towards the cage, 2) spoke the animal’s name, and 3) moved the lock used to secure the door of the cage. If the monkey responded immediately (i.e., opened eyes and oriented to the observer), rest/sleep posture was scored. If the monkey attended more slowly (i.e., > 3 seconds following stimuli) and was observed to be assuming an atypical posture that differed from the characteristic rest/sleep posture (e.g., unable to keep an upright posture), the observer scored moderate sedation. If the monkey did not open eyes across the 15-s interval after all three stimuli, the observer noted the loss of ability to respond to external stimuli and made an assessment of deep sedation. As noted above, the assessment of sedation was initiated during the 5-min sampling period if the animal presented, at any time during that period, with its eyes closed. The result of this assessment was recorded for each remaining 15-sec interval of the 60-sec epoch unless eyes opened. Afterwards, eyes closing again reinitiated the assessment. If eyes remained closed, then the assessment was repeated at the beginning of the next 60-sec epoch. The order in which animals were observed and the observer performing the scoring each day was randomized. Four observers participated in the scoring throughout the duration of the study; each observer underwent a minimum of 20 hours of training and met an inter-observer reliability criterion of ≥ 90% agreement with all other observers. For test observation samplings, the five-minute sampling period occurred once in the morning (~10:00). During chronic treatment, this corresponded to a regularly-scheduled injection of alprazolam.

During precipitated withdrawal tests, a set of behaviors were scored that were identified previously as associated with spontaneous and precipitated withdrawal following chronic BZ treatments in baboons (Lukas and Griffiths 1982; Lamb and Griffiths 1984; Weerts et al. 1998; 2005) and adapted to rhesus monkeys (Duke et al., 2020). We identified six behaviors common to these baboon studies (see Table 1, nose rub, lip droop, vomit/retch, rigid posture, tremor/jerk, seizure) and have included an additional category called “prone/lean posture”, in which the monkey assumed postures associated with “rest”, i.e., leaning against the wall or laying down on the floor of the cage, but had eyes open and was apparently alert (Duke et al., 2020). Scoring of withdrawal signs occurred as a presence or absence checklist following different time points following an injection, and were conducted in addition to the regularly scheduled alprazolam injections. Scoring occurred at ~10:00, immediately after a scheduled alprazolam injection, followed by test ligand injection (i.e., time 0), and at 7.5, 15, and 30 min after the injections.

Table 1.

Definitions of withdrawal-related behaviors.

| Behavior | Definition |

|---|---|

| Prone/Lean Posture | Laying chest facing down on bottom of cage and/or leaning against side of cage, eyes open. |

| Nose Rub | Repeated displacement of nose/muzzle from midline by either limb or cage bar. |

| Lip Droop | Extended and flaccid lower lip. |

| Vomit/Retch | Disgorging stomach contents through the mouth or making an effort to do so (often accompanied by “gagging” sound); may not expel vomitus but its presence is assumed by extension of cheek pouch and/or chewing/swallowing. |

| Rigid Posture | Grasping cage with arms extended, appears to flex and/or stretch torso |

| Tremor/Jerk | Involuntary, rhythmic muscle contraction leading to shaking/jerking movements in one or more parts of the body |

| Seizure | Tonic, clonic, or both: Tonic is indicated by contraction of muscle groups, usually taking the form of extension of back and neck followed by limbs; Clonic is indicated by mild, repetitive tremor followed by brief, violent, rhythmic flexor spasms over entire body. |

Adapted from Lukas and Griffiths (1982); Lamb and Griffiths (1984); Weerts et al. (1998, 2005).

2.4. Study design

The study was conducted in 3 phases (Table 2). During phase 1, acute tests were conducted with all ligands in Table 3 over a period of approximately 6 weeks (i.e., single day tests in different monkeys on different days). Once completed and with at least 2 days drug-free, monkeys began chronic alprazolam treatment, and after at least 14 days, phase 2 tests were initiated. For phase 2 tests, the ligands were re-tested in the same order (and same dose order) as occurred in phase 1 and chronic alprazolam treatment condition. However, the alprazolam injection scheduled for 10:00 AM was replaced by an injection of test ligand, followed by behavioral observation. For phase 3, the test ligands were re-tested as occurred in phases 1 and 2, except during this phase the tests occurred in the presence of alprazolam, i.e., the scheduled injection of alprazolam occurred, followed immediately by i.v. injection of test ligand.

Table 2.

Study design

| Phase | Chronic Treatment | Tests | Alprazolam during Test (Yes/No) | Phenomenon Tested |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | Alprazolam, Test Ligands*, Vehicles (once/day every 2+ days) | No | Acute Effects, Controls for Phases 2 & 3 |

| 2 | Alprazolam (6 mg/kg/day) | Alprazolam, Test Ligands*, Vehicles (once/day every 2+ days) | No | Tolerance, Cross-Tolerance |

| 3 | Alprazolam (6 mg/kg/day) | Alprazolam, Test Ligands*, Vehicles (once/day every 2+ days) | Yes | Precipitated Withdrawal |

See Table 3 for test ligands and test order.

Table 3.

Properties of test drugs and compounds used in the present study

| Drug/compound | Selectivity | Dose tested (mg/kg, i.v.) | Expected acute behavioral effects1 | βCCT sensitive |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| alprazolam | none | 0.1 | Rest/sleep posture | No |

| Observable ataxia | Yes | |||

| 1.0 | Deep sedation, | Yes | ||

| Observable ataxia | Yes | |||

| Midazolam2 | none | 0.1 | Rest/sleep posture | No |

| Observable ataxia | Yes | |||

| 1.0 | Deep sedation | Yes | ||

| Observable ataxia | Yes | |||

| zolpidem | α1GABAA preferential affinity | 3.0 | Increased tac/oral | Yes |

| Observable ataxia | Yes | |||

| 5.6 | Deep sedation | Yes | ||

| Decreased tac/oral | No | |||

| HZ-166 | α2/α3GABAA preferential efficacy | 10.0 | Rest/sleep posture | No |

| Decreased tac/oral | No | |||

| βCCT | α1GABAA Preferential affinity | 1.0 | No effect | N/A |

| 3.0 | No effect | N/A |

Based on quantitative behavioral observation in rhesus monkeys (Duke et al., 2018; 2020).

Midazolam results with βCCT are predicted but not tested. Effects of midazolam alone were based on unpublished data. All other predictions based on Duke et al. (2018; 2020).

For all test injections, each drug/compound, in the order shown in Table 3, was injected into the catheter via a syringe followed by a 2-mL saline flush. Stock solutions for each test drug or compound were prepared and doses were administered by varying the volume of injection (vehicle volumes were also varied from lowest to highest volumes for each monkey, in double determinations). For chronic administration (phases 2 and 3), alprazolam was administered 24 h per day, 7 days per week, as a single injection into the catheter every 4 h via a syringe pump (0.2 ml/s infusion rate, duration 1–3 s depending on the monkey’s weights), which was programmed via Med Associates (St. Albans, VT) equipment in an adjacent room. During phase 2, the pump was turned off prior to the 10:00 AM injection, the test ligand plus flush administered, followed by replacement of fluid in the syringe by alprazolam solution and re-attachment to the syringe pump. During phase 3, the same procedure was followed as in phase 2, except that the alprazolam injection via syringe pump occurred, followed by the injection via syringe as described above.

2.5. Data analysis

Our previous research demonstrated that modified frequency scores are normally distributed, so parametric statistics were conducted in order to facilitate cross-study comparisons (Rüedi-Bettschen et al. 2013; Duke et al. 2018; 2020; Huskinson et al., 2020). Except for the βCCT study, the primary hypothesis tested was that depending on dose of drug/compound, a given behavioral effect would differ between the “pre-chronic alprazolam” condition vs. the “during chronic alprazolam” condition. This hypothesis was tested by conducting a series of Bonferroni t-tests, using the overall mean square error as the denominator of the t-statistics in order to control for family-wise error rates. In addition, repeated measures ANOVAs with condition and dose as independent variables were conducted. For withdrawal tests, the withdrawal-associated behaviors during the modified frequency sampling period were summated into a single score, which was analyzed as a function of day of dose and time after injection, by repeated measures ANOVA and Bonferroni t-tests. To represent the distribution of individual behaviors (thereby allowing a qualitative comparison to previous results with flumazenil and spontaneous withdrawal), for each significant dose and time point, we averaged each behavior that contributed to the total and plotted these data in a stacked bar chart. For all statistics, the family-wise error rate (alpha) was constrained to p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Replacement of scheduled alprazolam injections with test ligands

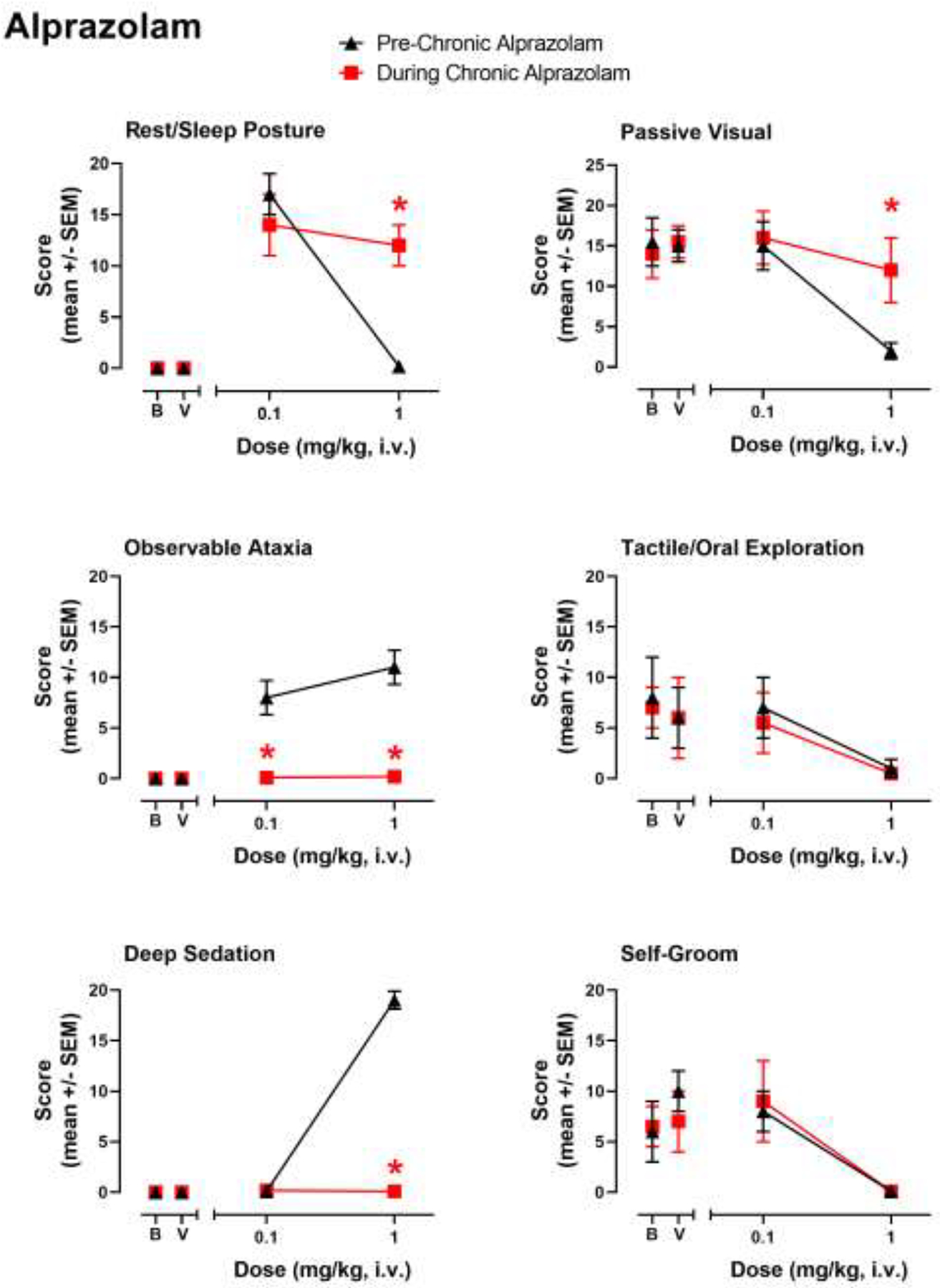

The first tests performed during chronic alprazolam treatment were substitution of a programmed dose of alprazolam with one of two test doses of alprazolam, compared with the same doses evaluated prior to chronic alprazolam treatment. These initial tests served to define tolerance (or lack thereof) to specific behavioral effects of alprazolam, as reported in detail previously (Duke et al., 2020). To represent these data, Figures 1–4 have sedative-motor effects that showed changes previously for alprazolam shown in the left three panels, with species-typical effects in the right three panels. With respect to rest/sleep posture (a mild form of sedation), acute treatment of 0.1 mg/kg (i.v.), but not 1.0 mg/kg (i.v.) in the pre-chronic condition resulted in near maximal rest/sleep posture scores (Fig. 1, top left panel). During chronic treatment of alprazolam, rest/sleep posture was unchanged at 0.1 mg/kg but was increased significantly at 1.0 mg/kg compared with the pre-chronic alprazolam condition (Fig. 1, top left panel; Bonferroni t-test p<0.05). In contrast, observable ataxia that was engendered by both doses of alprazolam prior to chronic treatment was eliminated completely when tested in the chronic treatment phase (Fig. 1, middle left panel; Bonferroni t-tests p<0.05). For deep sedation, consistent with our prior studies (Duke et al., 2018; 2020), this measure was evident at near maximal levels in monkeys prior to chronic alprazolam treatment at the highest dose tested, but completely eliminated during the chronic treatment phase (Fig. 1, bottom left panel; Bonferroni t-test p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Evaluation of sedative-motor effects (deep sedation, observable ataxia, rest/sleep posture) and species-typical behavior (passive visual, tactile/oral exploration, self-groom) in rhesus monkeys (N=4) prior to chronic alprazolam treatment (“Pre-Chronic Alprazolam”) tests and after ≥14 days of 6 mg/kg/day alprazolam (“During Chronic Alprazolam”). Alprazolam was administered i.v. and behavior was determined via focal observation sampling (5 min interval) conducted following the daily (~10:00 AM) injection. Observations were conducted by trained experimenters (see text for details) unaware of the treatments. Chronic alprazolam (1.0 mg/kg, i.v.) was administered via syringe pump 7 days per week, every 4 hours (6 mg/kg/day), via chronic venous catheters. Data are mean modified frequency scores ± SEM. “B”, baseline behavior scores with no injection, taken prior to any drug/compound exposures; “V” tests following vehicle injections. *Note that asterisks are acute (Pre-Chronic Alprazolam) test results vs. the same tests conducted during chronic administration (During Chronic Alprazolam), Bonferroni t-tests, p< 0.05.

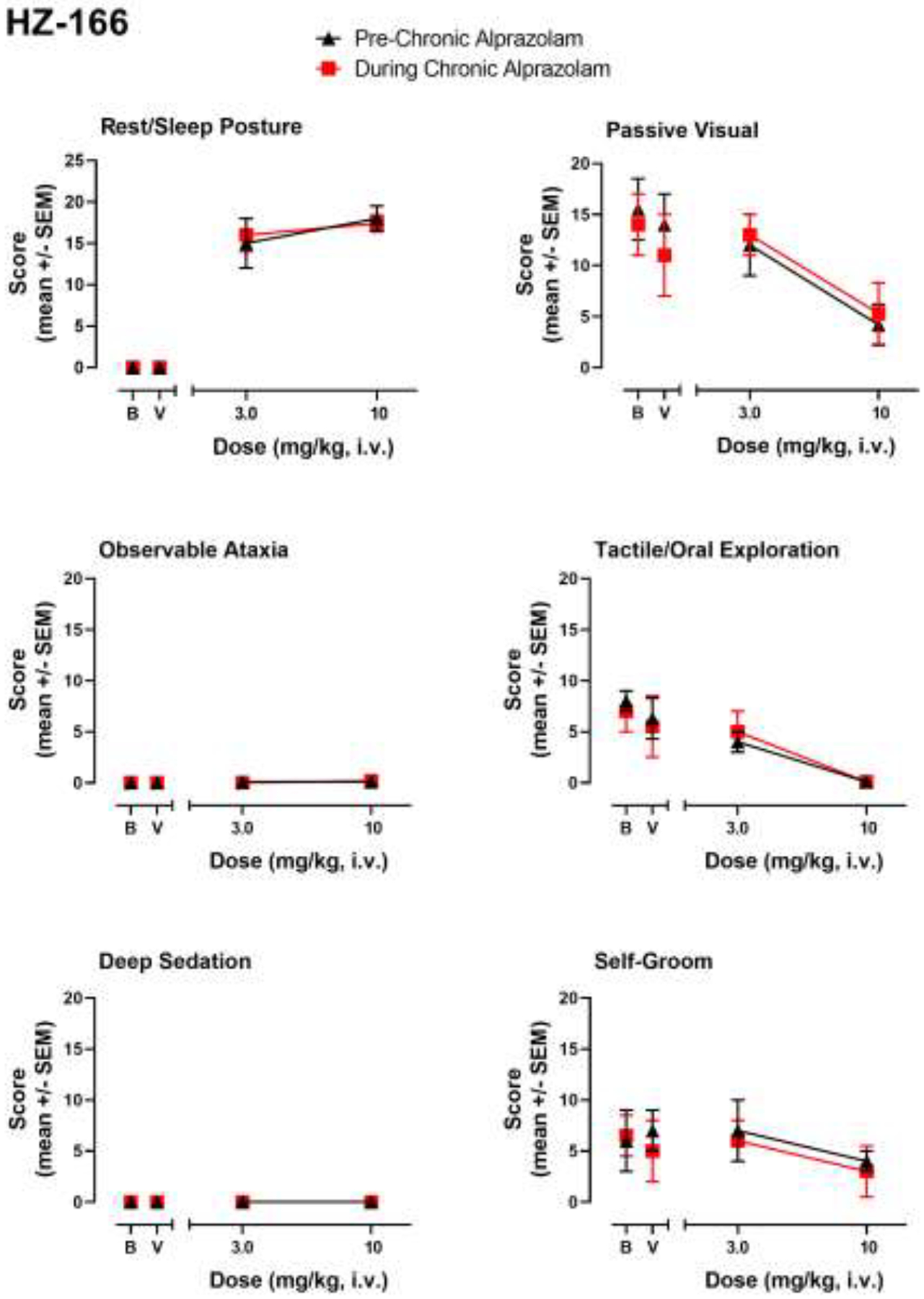

Figure 4.

HZ-166-induced sedative-motor effects (deep sedation, observable ataxia, rest/sleep posture) and changes in species-typical behavior (passive visual, tactile/oral exploration, self-groom) in rhesus monkeys (N=4) prior to chronic alprazolam treatment (“Pre-Chronic Alprazolam”) tests and after ≥14 days of 6 mg/kg/day alprazolam (“During Chronic Alprazolam”). HZ-166 is an α2/3GABAA-subtype-preferring positive modulator. Other details as described in the caption for Figure 1.

In addition to sedative-motor effects, we previously have shown changes in species-typical behavior with acute alprazolam treatment (Duke et al., 2018; 2020); and in the present study we observed decreases in passive-visual exploration, tactile/oral exploration, and self-groom engendered by the higher dose (1.0 mg/kg, i.v.) of alprazolam tested (Fig. 1, right panels). Also consistent with Duke et al. (2020), the only significant change we recorded for species-typical behavior during chronic alprazolam treatment was an increase in passive visual exploration at the 1.0 mg/kg dose (Fig. 1, top right panel; Bonferroni t-test, p<0.05).

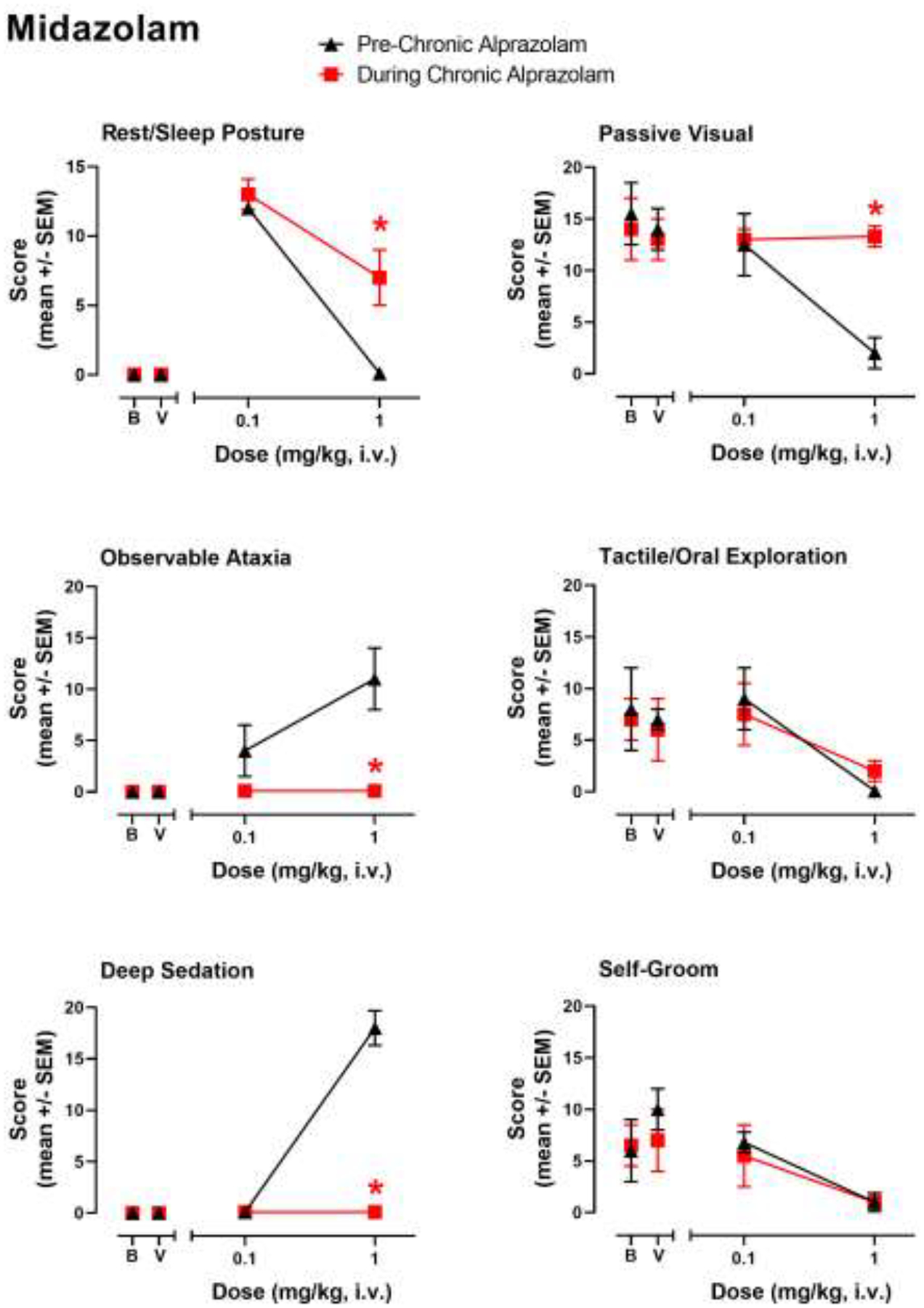

In order to establish the extent to which cross-tolerance occurs between chronic alprazolam and a related BZ, we evaluated the 1,5-benzodiazepine midazolam in monkeys prior to and during chronic alprazolam treatment. As can be seen in Fig. 2, the tests with midazolam revealed a pattern of results strikingly similar to that of alprazolam. In this regard, rest/sleep posture was engendered by a relatively low (0.1 mg/kg, i.v.) but not higher (1.0 mg/kg, i.v.) dose of midazolam prior to chronic alprazolam treatment, but this measure was increased at the higher dose when re-evaluated during the chronic treatment phase (Fig. 2, top left panel; Bonferroni t-test p<0.05). Similarly, midazolam-induced observable ataxia was eliminated by chronic alprazolam treatment (1.0 mg/kg midazolam dose only, Fig. 2, middle left panel; Bonferroni t-test p<0.05). Deep sedation that occurred at the higher dose tested of midazolam in the pre-chronic alprazolam condition was eliminated during chronic alprazolam treatment (Fig. 2, bottom left panel; Bonferroni t-test p<0.05). For species-typical behavior, as with alprazolam the only significant difference was an increase in passive-visual exploration engendered by the 1.0 mg/kg dose of midazolam relative to the pre-chronic condition (Fig. 2, top right panel; Bonferroni t-test p<0.05). In summary, these results suggest cross-tolerance (i.e., decrease in behavioral effects similar to that observed with alprazolam) for observable ataxia and deep sedation.

Figure 2.

Evaluation of midazolam-induced sedative-motor effects (deep sedation, observable ataxia, rest/sleep posture) and changes in species-typical behavior (passive visual, tactile/oral exploration, self-groom) in rhesus monkeys (N=4) prior to chronic alprazolam treatment (“Pre-Chronic Alprazolam”) tests and after ≥14 days of 6 mg/kg/day alprazolam (“During Chronic Alprazolam”). Midazolam was administered i.v. instead of alprazolam (~10:00 AM) and behavior was determined via focal observation sampling (5 min interval). Other details as described in the caption for Figure 1.

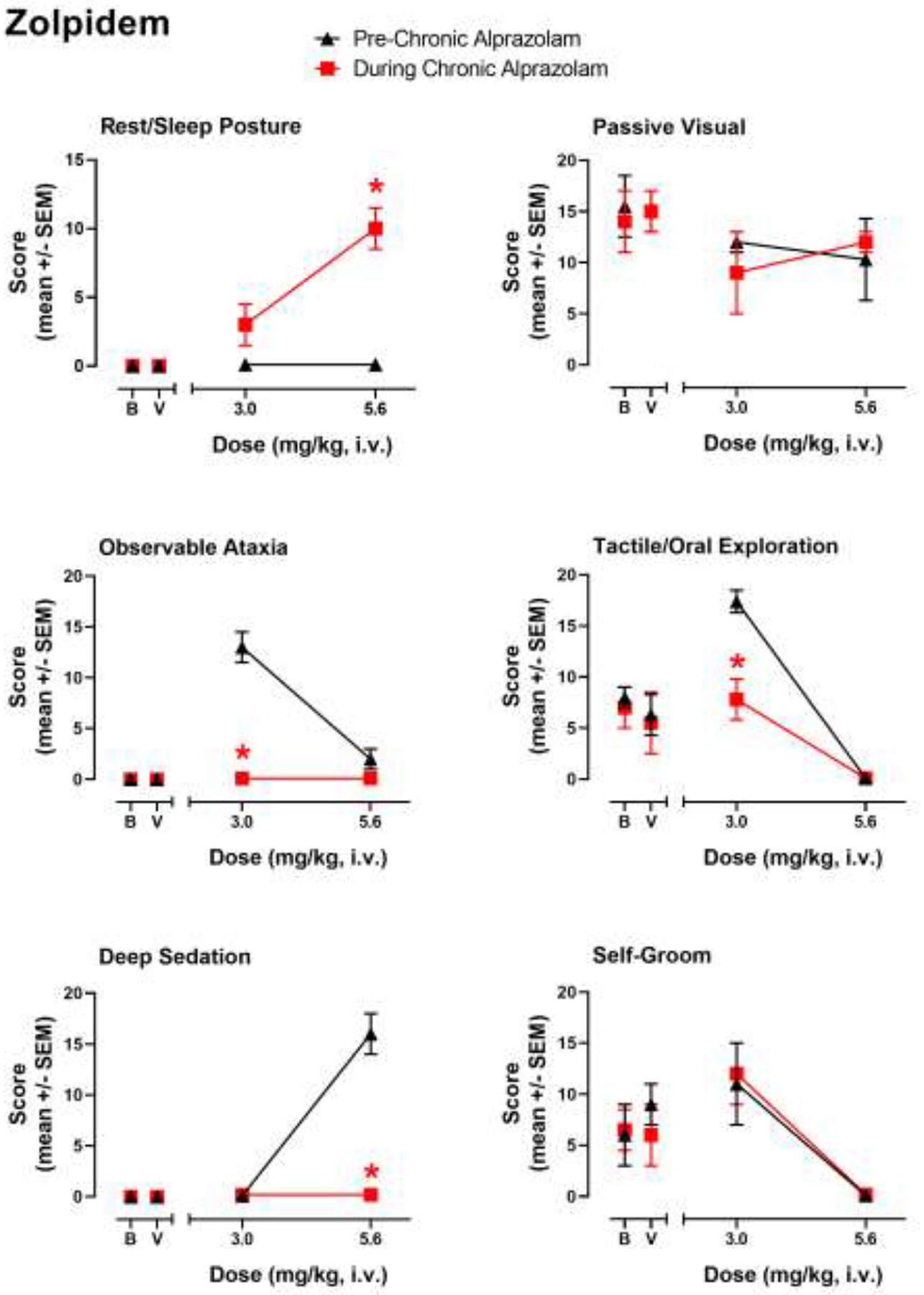

Evaluation of the subtype-preferring compounds resulted in a different overall pattern of behavioral effects during chronic alprazolam, due in part to a differing profile of effects observed prior to chronic alprazolam treatment (see also Duke et al., 2018). For example, in the present study the α1GABAA subtype-preferring drug zolpidem did not engender rest/sleep posture at the doses tested, increased observable ataxia scores at a dose of 3.0 mg/kg, i.v., and engendered significant deep sedation at a higher dose of 5.6 mg/kg, i.v. Interestingly, the higher dose (5.6 mg/kg) of zolpidem, when substituted for alprazolam in the chronic treatment phase, engendered significant rest/sleep posture (Fig. 3, top left panel; Bonferroni t-test p<0.05)—an effect that was not observed at any dose in our prior research (Duke et al., 2018). However, as with alprazolam and midazolam, observable ataxia at the lower dose of zolpidem (3.0 mg/kg) and deep sedation engendered by the higher dose (5.6 mg/kg) were both eliminated completely by chronic alprazolam treatment (Fig. 3, middle and bottom left panels; Bonferroni t-tests p<0.05). Changes in species-typical behavior were also unique to zolpidem, with no acute effects on passive-visual exploration prior to, or during, chronic alprazolam treatment at either dose of zolpidem (Fig. 3, top right panel), but a robust increase in tactile/oral exploration induced at 3.0 mg/kg zolpidem prior to chronic treatment that was attenuated to vehicle and baseline levels during chronic treatment (Fig. 3, middle right panel; Bonferroni t-test p<0.05). As with alprazolam and midazolam, the attenuation of both tactile/oral exploration and self-groom by the higher dose of zolpidem observed pre-chronic alprazolam treatment was not altered by chronic alprazolam treatment (Fig. 3, bottom right panel). Therefore, as with the non-selective modulators, evidence for cross-tolerance was obtained for observable ataxia and deep sedation only.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of zolpidem-induced sedative-motor effects (deep sedation, observable ataxia, rest/sleep posture) and changes in species-typical behavior (passive visual, tactile/oral exploration, self-groom) in rhesus monkeys (N=4) prior to chronic alprazolam treatment (“Pre-Chronic Alprazolam”) tests and after ≥14 days of 6 mg/kg/day alprazolam (“During Chronic Alprazolam”). Zolpidem is an α1GABAA-subtype-preferring positive modulator. Other details as described in the caption for Figure 1.

In contrast to other ligands, the α2/3GABAA-preferring modulator HZ-166 only engendered rest/sleep posture and suppressed tactile/oral exploration (at the highest dose tested, 10 mg/kg, i.v.) in monkeys prior to chronic alprazolam treatment, although similar to the other ligands, HZ-166 significantly reduced passive visual and tactile/oral exploration (Fig. 4). As can be seen in Fig. 4, no differences in any behavior were observed as a result of chronic alprazolam treatment. Because this compound did not induce behavioral effects that demonstrated tolerance associated with chronic alprazolam treatment under the conditions of the present study, no conclusions are suggested for the occurrence of cross-tolerance.

3.2. Precipitated withdrawal

During approximately week 6 of chronic alprazolam treatment, i.v. injections of midazolam, zolpidem, HZ-166, and the α1GABAA antagonist βCCT or its vehicle were given in sessions in the morning immediately after the automatic alprazolam injection. All withdrawal-related scores (Table 1) were summed to create a single “combined score”. Withdrawal scores were mostly absent with midazolam, zolpidem, and HZ-166, so the data were averaged across 0 and 7.5 min time points and shown in Table 4. All time point data are shown for βCCT in Fig. 5.

Table 4.

Tests of precipitated withdrawal in rhesus monkeys (n=4) treated chronically with alprazolam (6 mg/kg/day).

| Drug/compound | Dose in mg/kg, i.v. | Condition (Phase1) | Combined Withdrawal Score (mean ± SEM)2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| midazolam | Vehicle | Prior to chronic alprazolam (1) | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Vehicle | Chronic alprazolam (3) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | |

| 0.1 | Prior to chronic alprazolam (1) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | |

| 0.1 | Chronic alprazolam (3) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | |

| 1.0 | Prior to chronic alprazolam (1) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | |

| 1.0 | Chronic alprazolam (3) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | |

| zolpidem | Vehicle | Prior to chronic alprazolam (1) | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Vehicle | Chronic alprazolam (3) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | |

| 3.0 | Prior to chronic alprazolam (1) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | |

| 3.0 | Chronic alprazolam (3) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | |

| 5.6 | Prior to chronic alprazolam (1) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | |

| 5.6 | Chronic alprazolam (3) | 2.0 ± 2.0 | |

| HZ-166 | Vehicle | Prior to chronic alprazolam (1) | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| Vehicle | Chronic alprazolam (3) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | |

| 3.0 | Prior to chronic alprazolam (1) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | |

| 3.0 | Chronic alprazolam (3) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | |

| 10 | Prior to chronic alprazolam (1) | 0.0 ± 0.0 | |

| 10 | Chronic alprazolam (3) | 2.5 ± 0.5 |

For description of Phases, see Table 2.

Data are number of withdrawal signs (see Table 1) recorded and averaged for 0 and 7.5 minutes after injection of test drug or compound, averaged across monkeys. No scores were significantly different from vehicle (alprazolam/no alprazolam) treatment, p<0.05.

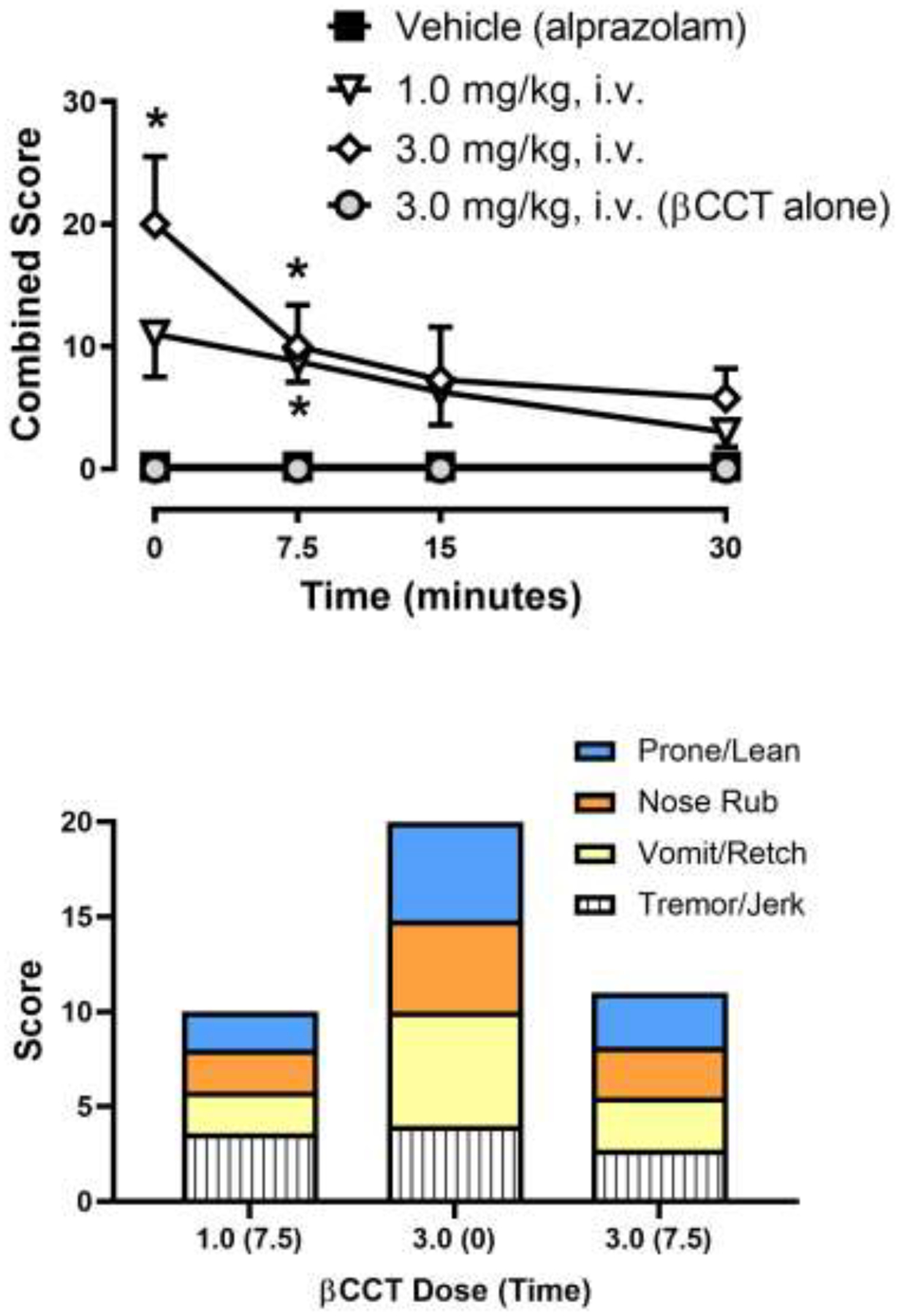

Figure 5.

Effects of the α1GABAA antagonist βCCT during chronic alprazolam treatment (1.0 mg/kg/4 h, or 6.0 mg/kg/day, i.v.) in rhesus monkeys (N=4). Top panel: Time-dependent effects of βCCT, βCCT vehicle (note that chronic alprazolam injections continued during these tests), or the 3.0 mg/kg dose of βCCT tested prior to chronic alprazolam treatment (“βCCT alone”). Data are mean ± SEM for a combined score of all withdrawal-related behaviors (see Table 2). *Note that p< 0.05 vs. Vehicle (alprazolam) treatment (Bonferroni t-tests). Bottom panel: Distribution of individual withdrawal-associated behaviors (see Table 1) that constituted the average combined score at the time points after βCCT injections that were statistically significant compared to corresponding vehicle data. Each individual behavior is the mean across monkeys (error bars are not shown for clarity).

As shown in Table 4, no withdrawal signs were recorded for midazolam at either dose, its vehicle administered after an alprazolam injection during chronic alprazolam treatment, or after vehicle and the two midazolam doses tested alone prior to chronic alprazolam (only the highest dose of midazolam in the pre-chronic condition is shown, which resulted in no withdrawal signs—as was the case with the lower dose). This pattern of effects was also true for zolpidem vehicle and the 3.0 mg/kg dose. The higher dose of zolpidem resulted in a few instances of prone/lean posture in two monkeys, but no effects in the others and this effect was not significantly different from vehicle or the doses administered prior to chronic treatment (Table 4, Bonferroni t-tests, p>0.05). Similarly, HZ-166 treatment resulted in some instances of prone/lean posture at the 10 mg/kg dose, but the effects were not significantly different from vehicle or this dose tested alone, prior to chronic treatment. These results indicate that none of the positive modulators tested could precipitate withdrawal to a significant degree in monkeys treated chronically with alprazolam under the present conditions.

As shown in the top panel of Fig. 5, βCCT engendered withdrawal signs at both doses at the early time points (Fig. 5, top panel; Bonferroni t-tests, p<0.05). Specifically, the 1.0 mg/kg dose of βCCT resulted in a significant increase in withdrawal signs at the 7.5 minute pre-treatment interval, whereas the 3.0 mg/kg βCCT dose resulted in withdrawal signs at 0 and 7.5 min after the injection, relative to vehicle tests. Importantly, no evidence of withdrawal-associated behaviors was obtained with βCCT tested alone at either dose, prior to chronic alprazolam treatments (Fig. 5, data shown for 3.0 mg/kg dose only but also true for the 1.0 mg/kg dose). Evaluating the distribution of specific behaviors that constituted the withdrawal signs (Fig. 5, bottom panel; data shown for statistically significant results only) revealed a relatively consistent pattern across time and dose. In this regard, βCCT tended to engender a relatively equal distribution of prone/lean posture, nose rub, vomit/retch, and tremor/jerk (Fig. 5, bottom panel), irrespective of dose and time point. Therefore, in contrast to the positive modulators tested in this study, the α1GABAA-prefering antagonist βCCT induced withdrawal-associated signs that resembled those in quantity and distribution of signs that were essentially identical to that reported previously for flumazenil, as well as spontaneous withdrawal (Duke et al., 2020).

4. Discussion

Tolerance and physical dependence have been shown following chronic BZ treatment in several species used in preclinical research, including non-human primates and rodents, since early studies by Yanagita and colleagues (e.g., Yanagita and Takahashi, 1973). However, the precise GABAA receptor mechanisms underlying tolerance and dependence have yet to be uncovered fully (for reviews, see Wafford, 2005; Gravielle, 2016). Here, we describe a study in which non-selective and subtype-selective BZ ligands were either replaced or were given concomitantly with alprazolam, in monkeys receiving alprazolam injections chronically. Both species-typical and drug-related behaviors were recorded using an approach previously shown to delineate different types of sedation, as well as to differentiate behaviors associated with apparent receptor subtypes (Duke et al., 2018; 2020; Huskinson et al., 2020).

A primary hypothesis guiding the present study is that tolerance develops rapidly to α1GABAA subtype-associated effects (e.g., deep sedation, observable ataxia) whereas behaviors associated with α2GABAA and/or α3GABAA receptors (e.g., rest/sleep posture, suppression of tactile/oral exploration) persist with chronic treatment. This hypothesis was developed based on findings that (1) an α1GABAA subtype-preferring ligand, zolpidem, engendered deep sedation and observable ataxia that was blocked by βCCT, an α1GABAA subtype-preferring antagonist; (2) ligands with α2/α3GABAA receptors engendered rest/sleep posture and suppression of tactile/oral exploration that was not blocked by βCCT; (3) βCCT blocked deep sedation and observable ataxia, but not rest/sleep posture or tactile/oral exploration suppression, induced by alprazolam; and (4) tolerance developed to deep sedation and observable ataxia, but not rest/sleep posture or suppression of tactile/oral exploration (and other species-typical behaviors) following chronic alprazolam treatment. To address this hypothesis, our first step was to establish the extent to which cross-tolerance can be demonstrated with a related, albeit structurally different, BZ ligand. Test doses of the 1,5-benzodiazepine midazolam were chosen to be those that engendered effects similar to those of alprazolam in observation studies with non-dependent monkeys (unpublished findings). When substituted for alprazolam injection, both doses of midazolam induced a profile of behavioral effects remarkably similar to that of alprazolam overall, consistent with a cross-tolerance for α1GABAA-associated but not α2/3GABAA-associated effects. These results provided the platform for evaluating subtype-selective compounds with distinct effects in non-dependent monkeys.

Because of the potential key role for α1GABAA receptors in the development of tolerance (van Rijnsoever et al., 2004; Vinkers et al., 2012; Ferreri et al., 2015; Foitzick et al., 2020), we evaluated selected doses of the α1GABAA-preferring modulator, zolpidem, and demonstrated that effects previously sensitive to blockade by βCCT (α1GABAA antagonist; Duke et al., 2018) were decreased (deep sedation, observable ataxia, increases in tactile/oral exploration) by chronic alprazolam. Regarding the increase in tactile/oral exploration engendered by the lower dose of zolpidem, the reduction in this effect following chronic alprazolam treatment is noteworthy because alprazolam itself did not engender a similar effect over a range of doses (Duke et al., 2018). In contrast, zolpidem-induced effects not sensitive to βCCT blockade (self-groom and tactile/oral exploration decreases) were unaltered by chronic alprazolam treatments, and strikingly, rest/sleep posture emerged at the highest zolpidem dose tested. This latter finding is similar to that observed with the relatively high dose of alprazolam (1.0 mg/kg, i.v.) used to induce tolerance and dependence, in that deep sedation dissipates after 3–5 days, concomitant with an increase in rest/sleep posture (Duke et al., 2020). We hypothesized that rest/sleep posture was “masked” due to deep sedation engendered by α1GABAA receptor stimulation by non-selective BZs, and this may be the case with zolpidem as well, given this ligand’s high degree of intrinsic efficacy at α2/3GABAA subtypes.

As an additional test of the idea that rest/sleep posture, as well as suppression of tactile/oral exploration and self-groom, are associated specifically with α2/3GABAA receptors and show persistence with chronic alprazolam treatment, we conducted a study with the α2/3GABAA-preferring ligand, HZ-166 (Rivas et al., 2009; Fischer et al., 2010), in which this compound replaced a scheduled daily alprazolam injection. Consistent with our previous findings (Duke et al., 2018), in monkeys in the pre-chronic condition HZ-166 engendered rest/sleep posture and attenuated tactile/oral exploration and self-groom, with no alterations in these behaviors by chronic alprazolam treatment. Altogether, these data support the hypothesis that behaviors associated with α1GABAA vs. α2/3GABAA receptor subtypes differentially show tolerance/cross-tolerance, with the former subtype’s behavioral effects associated with tolerance, whereas preferential activity at the latter subtypes are associated with behavioral effects of BZs that are relatively persistent.

Although our research in monkeys supports previous genetic research with mice, a study using “knock-in” mouse technology suggested a requirement for the α5GABAA receptor subtype in tolerance to diazepam’s sedative effects (van Rijnsoever et al. 2004). More recently, Vinkers et al. (2012) used GABAA receptor subtype-selective ligands to show that the development of tolerance required concomitant activation of α1GABAA and α5GABAA receptors. We have yet to investigate the role of α5GABAA receptors in the chronic effects of BZ ligands, however, our acute studies did not raise the possibility that α5GABAA receptors were associated with specific behaviors, although of course this possibility was not completely ruled out (Duke et al. 2018). More directly, a recent in vitro model of tolerance did not clearly demonstrate changes associated with the α5GABAA subtype, either with receptor expression or downstream mechanisms (Foitzick et al., 2020), indicating a clear need for further investigation under a broader range of conditions.

Physical dependence following chronic BZ exposure is a major impediment to use of these drugs as pharmacotherapies (Griffiths and Weerts 1997; Licata and Rowlett 2008). Moreover, physical dependence likely contributes to ongoing misuse/abuse of BZs, because drug taking may come to be maintained by the alleviation of withdrawal (i.e., negative reinforcement) and avoidance of detoxification may be a major reason for resistance to drug abstinence as well as high relapse rates (O’Brien 2005). The chronic treatment regimen used in the present study was shown previously to result in both spontaneous withdrawal and withdrawal precipitated by the BZ site antagonist, flumazenil (Duke et al., 2020; note that spontaneous withdrawal, which occurs after complete cessation of chronic drug treatment, was not evaluated in the present study). For both types of withdrawal, the signs were essentially identical, consisting of abnormal postures, behaviors indicative of gastrointestinal distress, and tremors. Importantly, these signs are shared with human patients in BZ withdrawal (Griffiths and Weerts 1997; O’Brien 2005) as well as with baboons following precipitated and spontaneous withdrawal (Lukas and Griffiths 1982; Lamb and Griffiths 1984; Weerts et al. 1998; 2005; for review, see Griffiths and Weerts 1997).

Precipitated withdrawal in monkeys following a single injection of a BZ (i.e., acute dependence) has been demonstrated (Spealman 1986; Fischer et al. 2013), and using this model, Fischer et al. (2013) provided evidence that withdrawal appears to involve the α1GABAA receptor subtype; a finding congruent with findings from prior research. For example, the α1GABAA subtype-preferring drugs zolpidem and zaleplon have been shown to induce physical dependence after chronic treatment in baboons (Weerts et al. 1998; Ator et al. 2000). Moreover, compounds lacking efficacy at α1GABAA subtypes had at least reduced propensities to result in physical dependence compared with conventional BZs (Mirza and Nielson 2006; Ator et al. 2010). Based on these observations, our second major hypothesis was that α1GABAA receptors mediate the expression of withdrawal signs in monkeys treated with chronic alprazolam. Consistent with this idea, administration of the α1GABAA antagonist βCCT following an alprazolam injection in chronically-treatment monkeys resulted in significant increases in withdrawal signs. Moreover, the distribution of the signs recorded (prone/lean posture, nose rub, vomit/retch, tremors) were entirely consistent with those observed previously with flumazenil and drug cessation, suggesting that a similar withdrawal syndrome was observed with both precipitated and spontaneous withdrawal.

Although the recapitulation of a characteristic set of withdrawal signs by βCCT administration supports the idea of α1GABAA subtype mediation of dependence, another finding provides some ambiguity in this regard. Specifically, the precipitated withdrawal test with HZ-166 did not result in withdrawal signs, resembling more the results with the positive modulators midazolam and zolpidem. Based on electrophysiological studies in vitro, HZ-166 has been described as a partial modulator of α1GABAA and α5GABAA subtypes, but a full modulator (i.e., diazepam-like) at α2GABAA and α3GABAA subtypes (Rivas et al., 2009; Fischer et al., 2010). Given the less-than-maximal effects of HZ-166 at the α1GABAA subtype, we anticipated that this compound likely would result in a mild form of withdrawal, but this was not the case. It should be noted that a small number of withdrawal signs were observed in two monkeys but with no statistical significance for the group. There are at least three explanations for these discrepant findings. First, given the presence of a minimal number of signs recorded, but failing to reach significance, it may be the case that longer amounts of exposure and/or higher doses would reveal a more pronounced withdrawal. Second, it is possible that HZ-166’s level of intrinsic efficacy at α1GABAA receptors was sufficient to engender cross-tolerance, rather than withdrawal. Countering this somewhat are the observations that HZ-166 lacked sedative-motor effects associated with α1GABAA subtype activation (Fischer et al., 2010; Duke et al., 2018). The third possible explanation is that in addition to α1GABAA subtypes, other GABAA subtypes (e.g., α2GABAA, α3GABAA subtypes) may play a key role in the development and persistence of BZ withdrawal. These hypotheses await further experimentation.

Alprazolam (Xanax®) is a commonly prescribed anxiolytic, but unfortunately, is also consistently reported as one of the more frequently misused/abused BZs in the US (e.g., Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2013). At present, the primary approach to treatment for addiction to BZs like alprazolam consists of detoxification, which is both difficult to achieve and associated with high rates of relapse. Our results are consistent with chronic alprazolam treatment resulting in physical dependence, as well as tolerance to some behavioral effects (e.g., deep sedation). Moreover, our findings support the hypothesis that a specific GABAA receptor subtype (α1GABAA receptors) is involved with the development of tolerance to specific behavioral effects and withdrawal signs following chronic BZ treatment, although the “door is left open” for involvement of other subtypes. Knowledge of distinct roles of GABAA receptor subtypes underlying alprazolam-induced tolerance and dependence should help inform the development of improved anxiolytic medications, as well as potential treatments for BZ addiction.

Highlights.

Chronic exposure to benzodiazepines can result in tolerance and physical dependence

Tolerance may be mediated primarily by GABAA receptors containing α1 subunits

Dependence involves α1-containing receptors but may include other GABAA subtypes

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Annemarie Duggan, Shana Langer, and Kristen Bano for participating in this research as behavioral scorers, and to Donna Reed for non-technical services.

Role of Funding Source

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants DA043204 (JKR), DA011792 (JKR), AA029023 (Platt), and NS076517 (Cook). Chemistry resources for the Cook group were provided by the National Science Foundation, Division of Chemistry (Grant CHE-1625735). We also acknowledge the UW-Milwaukee Shimadzu Laboratory for Advanced and Applied Analytical Chemistry and support from the Milwaukee Institute of Drug Discovery, as well as the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Research Foundation.

Acknowledgments of Funding and Grants:

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants DA043204, DA011792, AA029023, and NS076517; and the National Science Foundation, Division of Chemistry (Grant CHE-1625735). We also acknowledge the UW-Milwaukee Shimadzu Laboratory for Advanced and Applied Analytical Chemistry and support from the Milwaukee Institute of Drug Discovery, as well as the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of Competing Interest

No conflict declared.

References

- Ator NA, Atack JR, Hargreaves RJ, Burns HD, Dawson GR (2010) Reducing abuse liability of GABAA/benzodiazepine ligands via selective partial agonist efficacy at α1 and α2/3 subtypes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 332: 4–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke AN, Meng Z, Platt DM, Atack JR, Dawson GR, Reynolds DS, Tiruveedhula VVNPB, Li G, Stephen MR, Sieghart W, Cook JM, Rowlett JK (2018) Evidence that sedative effects of benzodiazepines involve unexpected GABAA receptor subtypes: Quantitative observation studies in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 366: 145–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke AN, Platt DM, Rowlett JK (2020) Tolerance and dependence following chronic alprazolam treatment: Quantitative observation studies in female rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology 237: 1183–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreri MC, Gutierrez ML, Gravielle MC (2015) Tolerance to the sedative and anxiolytic effects of diazepam is associated with different alterations of GABAA receptors in rat cerebral cortex. Neuroscience 310: 152–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer BD, Licata SC, Edwankar RV, Wang Z-J, Huang S, He X, Yu J, Zhou H, Johnson EM Jr, Cook JM, Furtmuller R, Ramerstorfer J, Sieghart W, Roth BL, Majumder S, Rowlett JK (2010) Anxiolytic-like effects of 8-acetylene imidazobenzodiazepines in a rhesus monkey conflict model. Neuropharmacology 59:612–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer BD, Teixeira LP, van Linn ML, Namjoshi OA, Cook JM, Rowlett JK (2013) Role of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor subtypes in acute benzodiazepine physical dependence-like effects: Evidence from squirrel monkeys responding under a schedule of food presentation. Psychopharmacology 227: 347–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foitzick MF, Medina NB, Garcia LCI, Gravielle MC (2020) Benzodiazepine exposure induces transcriptional down-regulation of GABAA receptor α1 subunit gene via L-type voltage-gated calcium channel activation in rat cerbrocortical neurons. Neurosci Lett 721: 134801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravielle MC (2016) Activation-induced regulation of GABAA receptors: Is there a link with the molecular basis of benzodiazepine tolerance? Pharmacol Res 109: 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths RR, Weerts EM (1997) Benzodiazepine self-administration in humans and laboratory animals – implications for problems of long-term use and abuse. Psychopharmacology 134:1–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huskinson SL, Platt DM, Brasfield M, Follett ME, Prisinzano TE, Blough BE, Freeman KB (2020) Quantification of observable behaviors induced by typical and atypical kappa-opioid receptor agonists in male rhesus monkeys. Psychopharmacology 237:2075–2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson DE, Smith JL, Ping X, Jin X, Golani LK, Li G, Tiruveedhula VVNPB, Rashid F, Mian Y, Jahan R, Sharmin D, Cerne R, Cook JM, Witkin JM (2020) Imidazodiazepine anticonvulsant, KRM-II-81, produces novel, non-diazepam-like antiseizure effects. ACS Chem Neurosci, 11: 2624–2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb RJ, Griffiths RR (1984) Precipitated and spontaneous withdrawal in baboons after chronic dosing with lorazepam and CGS 9896. Drug Alcohol Depend 14: 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licata SC, Rowlett JK (2008) Abuse and dependence liability of benzodiazepine-type drugs: GABAA receptor modulation and beyond. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 90: 74–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas SE, Griffiths RR (1982) Precipitated withdrawal by a benzodiazepine receptor antagonist (Ro 15–1788) after 7 days of diazepam. Science 217: 1161–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza NO, Nielsen EØ (2006) Do subtype-selective γ-aminobutyric acidA receptor modulators have a reduced propensity to induce physical dependence in mice? J Pharmacol Exp Ther 316: 1378–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien CP (2005) Benzodiazepine use, abuse, and dependence. J Clin Psychiatry 66(Suppl 2): 28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt DM, Rowlett JK, Spealman RD, Cook J, Ma C (2002) Selective antagonism of the ataxic effects of zolpidem and triazolam by the GABAA/α1-preferring antagonist β-CCT in squirrel monkeys. Psychopharmacology 164: 151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt DM, Carey G, Spealman RD (2011). Models of neurological disease (substance abuse): self-administration in monkeys. In: Current Protocols in Pharmacology 56:10.5.1–10.5.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spealman RD (1986) Disruption of schedule-controlled behavior by Ro 15–1788 one day after acute treatment with benzodiazepines. Psychopharmacology 88: 398–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2013) Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13–4760, DAWN Series D-39 Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- van Rijnsoever C, Tauber M, Choulli MK, Keist R, Rudolph U, Möhler H, Fritschy JM, Crestani F (2004) Requirement of α5-GABAA receptors for the development of tolerance to the sedative action of diazepam in mice. J Neurosci 24: 6785–6790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinkers CH, van Oorschot R, Nielsen EO, Cook JM, Hansen HH, Groenink L, Olivier B, Mirza NR (2012) GABAA receptor a subunits differentially contribute to diazepam tolerance after chronic treatment. PLoS ONE 7: e43054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wafford KA (2005) GABAA receptor subtypes: any clues to the mechanism of benzodiazepine dependence? Curr Opinion Pharmacol 5: 47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerts EM, Ator NA, Kaminski BJ, Griffiths RR (2005) Comparison of the behavioral effects of bretazenil and flumazenil in triazolam-dependent and non-dependent baboons. Eur J Pharmacol 519: 103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weerts EM, Ator NA, Grech DM, Griffiths RR (1998). Zolpidem physical dependence assessed across increasing doses under a once-daily dosing regimen in baboons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 285: 41–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagita T, Takahashi S (1973) Dependence liability of several sedative-hypnotic agents evaluated in monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 185: 307–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]