Abstract

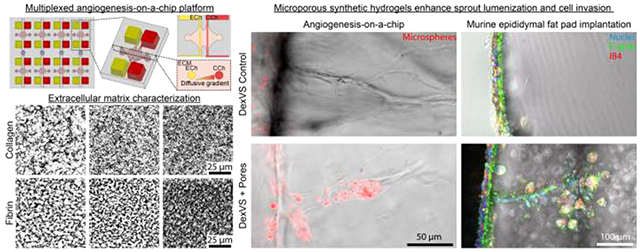

Vascularization of large, diffusion-hindered biomaterial implants requires an understanding of how extracellular matrix (ECM) properties regulate angiogenesis. Sundry biomaterials assessed across many disparate angiogenesis assays have highlighted ECM determinants that influence this complex multicellular process. However, the abundance of material platforms, each with unique parameters to model endothelial cell (EC) sprouting presents additional challenges of interpretation and comparison between studies. In this work we directly compared the angiogenic potential of commonly utilized natural (collagen and fibrin) and synthetic dextran vinyl sulfone (DexVS) hydrogels in a multiplexed angiogenesis-on-a-chip platform. Modulating matrix density of collagen and fibrin hydrogels confirmed prior findings that increases in matrix density correspond to increased EC invasion as connected, multicellular sprouts, but with decreased invasion speeds. Angiogenesis in synthetic DexVS hydrogels, however, resulted in fewer multicellular sprouts. Characterizing hydrogel Young’s modulus and permeability (a measure of matrix porosity), we identified matrix permeability to significantly correlate with EC invasion depth and sprout diameter. Although microporous collagen and fibrin hydrogels produced lumenized sprouts in vitro, they rapidly resorbed post-implantation into the murine epididymal fat pad. In contrast, DexVS hydrogels proved comparatively stable. To enhance angiogenesis within DexVS hydrogels, we incorporated sacrificial microgels to generate cell-scale pores throughout the hydrogel. Microporous DexVS hydrogels resulted in lumenized sprouts in vitro and enhanced cell invasion in vivo. Towards the design of vascularized biomaterials for long-term regenerative therapies, this work suggests that synthetic biomaterials offer improved size and shape control following implantation and that tuning matrix porosity may better support host angiogenesis.

Statement of significance

Understanding how extracellular matrix properties govern angiogenesis will inform biomaterial design for engineering vascularized implantable grafts. Here, we utilized a multiplexed angiogenesis-on-a-chip platform to compare the angiogenic potential of natural (collagen and fibrin) and synthetic dextran vinyl sulfone (DexVS) hydrogels. Characterization of matrix properties and sprout morphometrics across these materials points to matrix porosity as a critical regulator of sprout invasion speed and diameter, supported by the observation that nanoporous DexVS hydrogels yielded endothelial cell sprouts that were not perfusable. To enhance angiogenesis into synthetic hydrogels, we incorporated sacrificial microgels to generate microporosity. We find that microporosity increased sprout diameter in vitro and cell invasion in vivo. This work establishes a composite materials approach to enhance the vascularization of synthetic hydrogels.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Cell Migration, Cell Proliferation, Microfluidics, ECM, Endothelial Cells, Chemotaxis, Hydrogels, Microvasculature, Sprouting Morphogenesis, Matrix porosity

Graphical abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

The vascularization challenge remains a major hurdle to the clinical translation of engineered tissue repair and organ replacement therapies [1,2]. A major focus has been placed on engineering microscale vessels within implantable biomaterials, as nearly all tissues in vivo are supplied with oxygen and nutrients by a hierarchical vascular network of larger diameter arterioles and venules bridged by dense microscale capillary beds [3]. An emerging strategy to engineer microvasculature lies in the design of implantable biomaterials that support angiogenesis, the invasive biological process by which pre-existing microvasculature extends. Biomaterials capable of initiating angiogenesis from the host vasculature and recruiting invasive microvessels could ensure circulation between the host and implant. Angiogenesis is generally accepted to be a multi-step process involving 1) chemokine gradients that promote tip cell formation, 2) collective migration of multicellular sprouts through a surrounding 3D extracellular matrix (ECM), and 3) subsequent microvessel maturation that commences with neovessel lumenization [4,5]. Although the timely formation of perfused host microvasculature should enhance the viability of cell-laden biomaterials [6], the angiogenic process driven too rapidly or in a dysregulated fashion negatively impacts microvasculature quality and function [7,8]. The informed design of biomaterials that support functional angiogenesis therefore critically requires an understanding of how specific soluble and physical microenvironmental cues regulate this complex process [7,9].

In vitro models that can help extend our understanding of how the microenvironment regulates angiogenesis require two essential components: 1) the surrounding 3D material through which multicellular endothelial sprouts navigate, and 2) an appropriate culture platform that defines physical and soluble boundary conditions and enables facile assessment of the angiogenic process [10-12]. The first angiogenic biomaterial hydrogels were formed from reconstituted ECM proteins harvested and purified from animals. In particular, reconstituted type I collagen and fibrin hydrogels have long been used to model stromal and wound healing ECM, respectively [13-15]. To examine how matrix properties influence angiogenesis, a common perturbation for naturally-derived hydrogels (e.g. collagen and fibrin) is to modulate protein concentration. Across a variety of studies, increasing matrix density results in decreased endothelial cell (EC) sprouting [7,16-18]. However, increased matrix density simultaneously decreases porosity, while increasing stiffness and ligand density – this perturbation which covaries multiple matrix attributes hinders our understanding of the microenvironmental cues governing key steps in angiogenic sprouting. Towards understanding how individual matrix properties influence angiogenesis, numerous biomaterials have been designed to possess orthogonally tunable properties [11,19]. A wide range of synthetic and semi-synthetic hydrogel systems, including functionalized polyethylene glycol, hyaluronic acid, alginate, and dextran, have been created to examine the influence of matrix stiffness, porosity, degradability, viscoelasticity, and ligand engagement on cell behavior [20-26]. Despite the wealth of available synthetic biomaterials, robust angiogenesis and resulting microvessel formation within synthetic hydrogels has proved challenging relative to angiogenesis in naturally-derived biomaterials such as collagen and fibrin. We posit that the identification of critical matrix properties that regulate angiogenesis in natural materials and then imbuing synthetic hydrogels with these features is critical to achieving control over synthetic biomaterial implant vascularization.

The second essential element is the culture platform used to drive the angiogenic process and quantitatively assess resulting microvasculature that forms. The culture platform houses the biomaterial and may define its architecture, dictates the cellular constituents and their initial positions, imposes external mechanical and soluble boundary conditions, and defines the directionality and imaging plane of formed vasculature which is critical to robust morphometrics. An ongoing challenge to selecting an ideal angiogenic biomaterial stems from cross-comparison between studies, where each study employs distinct angiogenesis platforms (e.g. 2D scratch assays, 3D spheroid outgrowth, or microfluidics), each yielding unique parameters to model and interpret EC sprouting morphogenesis [12]. EC outgrowth assays from microcarrier beads or cell spheroids embedded within 3D ECM have been instrumental in recapitulating 3D sprouting morphogenesis [27,28]. However, across studies, the methods to induce EC outgrowth has varied considerably as sprouting morphogenesis has been shown to be sensitive to the addition of exogenous chemokines and undefined cell-secreted factors from the addition of secondary support cells. Furthermore, the addition of secondary support cells have varied in cell identity (e.g. fibroblasts, mesenchymal stem cells, or cancer cells) as well as location as a 2D feeder layer, embedded in 3D, or intermixed with ECs in spheroids [16,29-31]. More recently, advances in biomicrofluidics and efforts to develop tissue-on-a-chip platforms have generated models of human engineered microvessels fully embedded within user-defined ECM in which EC sprouting can be initiated with well-defined gradients of pro-angiogenic factors [7,32-34]. While previous microfluidics-based angiogenesis assays suffer from complicated and low-throughput device assembly, our group has recently established a multiplexed, single-layer fabrication approach affording higher throughput investigation of large parameter spaces such as the wide array of available biomaterials [7].

The following work directly compares commonly utilized biomaterials in a microfluidics-based platform that recapitulates key features of physiologic angiogenesis, namely a chemokine-directed 3D invasion of ECs from a lumenized parent vessel into a surrounding, user-defined biomaterial. Employing type I collagen, fibrin, and synthetic dextran hydrogels, we directly compare 3D EC sprouting morphogenesis within these distinct biomaterials varying in material properties. As a quantitative measure of matrix porosity, we developed a fluorescent recovery after photobleaching method to extract an intrinsic material property related to matrix pore size and structure - matrix permeability. Interestingly, we found that matrix permeability significantly correlates with EC invasion depth and sprout diameter. While the nanoscale pore size of dextran hydrogels restricted EC proliferation and sprout diameter resulting in non-lumenized sprouts in vitro, upon implantation, we note better retention of the size and shape of synthetic hydrogel implants in the mouse epididymal fat pad as compared to collagen and fibrin grafts which rapidly resorb. To enhance pore size within synthetic dextran hydrogels, we employed a composite materials approach embedding pore-generating, sacrificial gelatin microgels. Synthetic hydrogels imbued with microporosity resulted in increased sprout diameter and the formation of lumenized, multicellular EC sprouts. Through the direct comparison of natural and synthetic hydrogels, we identified matrix permeability as a critical regulator of angiogenesis and introduce a new materials approach to tune porosity and enhance the angiogenic potential of synthetic biomaterials.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Reagents.

All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received, unless otherwise stated.

2.2. Microfluidic device fabrication.

3D printed moulds were designed in AutoCAD and printed via stereolithography from Protolabs (Maple Plain, MN). Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, 1:10 crosslinker:base ratio) devices were replica casted from 3D printed moulds, cleaned with isopropyl alcohol and ethanol, and bonded to glass coverslips with a plasma etcher. Devices were treated with 0.01% (w/v) poly-l-lysine and 0.5% (w/v) L-glutaraldehyde sequentially for 1 hour each to promote ECM attachment to the PDMS housing, thus preventing potential hydrogel compaction from cell-generated forces. 300 μm diameter stainless steel acupuncture needles (Lhasa OMS, Weymouth, MA) were dip-coated with 1% (w/v) gelatin to reduce hydrogel fracture, inserted into each device, and sterilized. Hydrogel precursor solution was then injected into each device and polymerized around each set of needles. Hydrogels were hydrated in EGM2 media at 37°C overnight (or greater than 12 hours) to dissolve the gelatin layer and needles were removed to form 3D hollow channels fully embedded within a crosslinked hydrogel and positioned 400 μm away from PDMS and glass boundaries.

2.3. Dextran vinyl sulfone polymer synthesis.

Dextran (molecular weight 86,000 Da, MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) was modified with vinyl sulfone groups as in [35-37]. Dextran (5 g) was dissolved in 0.1 M sodium hydroxide solution (250 mL) at room temperature. Divinyl sulfone (3.875 ml, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was added and the reaction was carried out for 4 minutes with vigorous stirring (1500 RPM) at room temperature. The reaction was terminated by adjusting the pH to 5.0 with the addition of hydrochloric acid. The reaction product was dialyzed against milli-Q water for 3 days with two solvent exchanges daily. The dialyzed reaction product was then lyophilized for 3 days to obtain the pure product, which was then characterized by 1H-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy in D2O. The degree of vinyl sulfone functionalization was calculated as the ratio of the proton integral (6.91 ppm) and the anomeric proton of the glucopyranosyl ring (5.166 and 4.923 ppm); here a vinyl sulfone/dextran repeat unit ratio of 0.16 was determined.

2.4. Hydrogel formulations.

Dextran vinyl sulfone hydrogels were formed via a thiol-ene click reaction at 3.25 %w/v (pH 7.4, 37°C, 1 hour) solubilized in PBS containing 50 mM HEPES with 12.5 mM MMP-labile crosslinker (GCRDVPMS↓MRGGDRCG, Genscript, Piscataway, NJ) in the presence of argininyl-glycyl-aspartic acid (RGD, CGRGDS, 2 mM, Genscript), heparin-binding peptide (GCGAFAKLAARLYRKA, 1 mM, Genscript), and cysteine (0.5 mg ml−1). As indicated in experiments, collagen (100 μg ml−1) or fibrinogen (100 μg ml−1) proteins were incorporated in the dextran vinyl sulfone precursor solution during crosslinking. For microporous DexVS hydrogels, 31 μl of a gelatin microgel solution (22.8 x 106 microgels/ml density) were added for every 100 μl of total hydrogel volume resulting in a 7.3% volume occupied by microgels. Gelatin microgels were then melted at 37°C with excess PBS over 24 hours. Type I rat tail collagen hydrogels (Corning, Corning, NY) were prepared on ice with a reconstitution buffer (10 mM HEPES, 0.035 %w/v sodium bicarbonate), M199, and titrated to a pH of 7.6 with 1 M NaOH and brought to a final concentration of 2, 3, or 6 mg ml−1 collagen with Milli-Q water. Collagen hydrogels were crosslinked for 30 minutes at 37°C. Fibrin hydrogels were prepared with fibrinogen from bovine plasma dissolved in PBS at 50 mg ml−1 stock concentrations. Fibrinogen (2.5, 5, and 15 mg ml−1) was prepared on ice in PBS and crosslinked with thrombin (6 units per mg of fibrinogen) for 20 minutes at 37°C. All hydrogels were hydrated in EGM2 media after crosslinking.

2.5. Microfluidic droplet generator.

Gelatin microgels were generated from a droplet-based microfluidic device. The pattern was designed in AutoCAD, and a master mold was fabricated using a SU-8 negative photoresist (Kayaku, Westborough, MA). PDMS (1:10 crosslinker:base ratio) was cast, cleaned, and bonded to glass. An aqueous phase containing 2.5 %w/v gelatin was prepared in addition to an oil phase comprised of 1 %w/v perfluoropolyethylene (Ran Biotechnologies, Beverly, MA) in HFE-7500 (3M, St. Paul, MN), a perfluorinated mineral oil. A syringe pump was used to flow the aqueous and oil phases through the microfluidic device at 0.5 and 1.0 mL/hr, respectively, to generate water-in-oil droplets with a high degree of monodispersity (Fig. 8a-d). During droplet generation, the syringe containing the aqueous phase was warmed with a heating lamp, and the microfluidic device was placed on a hotplate set to 75°C. The resulting emulsion was collected, refrigerated at 4°C for 30 minutes to ensure gelation of the aqueous phase, and then broken by the addition of PBS and 20 %v/v perfluorooctanol (PFO, Alfa Aesar, Haverhill, MA). Oil phase components and PFO were washed from the microgels via centrifugation for 3 minutes at 400 g and replaced with PBS. Microgels swelled from 20 μm to 27.85 μm diameter after the liquid-oil phase emulsion was broken and achieved equilibrium swelling in PBS. A 1:10 dilution of the resulting suspension was loaded onto a hemocytometer to count microgel density.

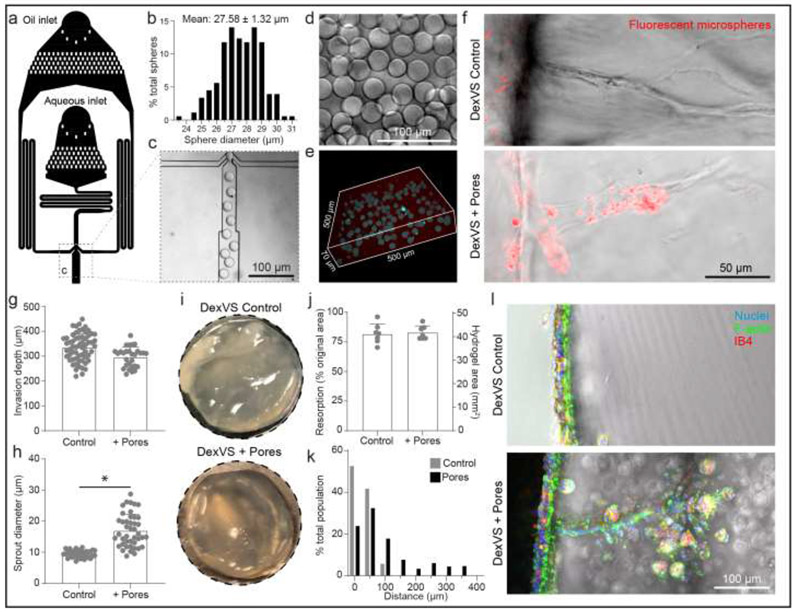

Figure 8∣. Sacrificial gelatin microgels to enhance microporosity increase sprout diameter in vitro and cell invasion in vivo.

a, Schematic of microfluidic droplet generator with oil and aqueous inlets. b, Histogram of gelatin microgel diameter. c, Inset of oil and aqueous junction. d-e, Image of a solution of gelatin microgels (d) and encapsulated in 3D DexVS hydrogel (e). f, Images of endothelial cell invasion into control and microporous DexVS hydrogels in vitro after 3 days of sprouting. g-h, Quantifications of invasion depth (n ≥ 29) and sprout diameter (n ≥ 33) from in vitro sprouting conditions in (f). i, Images of hydrogel explants after 7 days implantation into fat pad. j, Quantification of hydrogel resorption and final hydrogel area (n = 7). k, Histogram of cell migration invasion distance into implanted hydrogels. I, Images of vibratome sections of cell invasion. Nuclei (blue), F-actin (green), Isolectin B4 (red). All data presented as mean ± s.d.; * indicates a statistically significant comparison with P<0.05 (two-sided student’s t-test).

2.6. Device cell seeding and culture.

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs; Lonza, Switzerland) were cultured in endothelial growth media (EGM2, Lonza). HUVECs were passaged upon achieving confluency at a 1:4 ratio and used in studies from passages 4 to 9. A 20 μl solution of suspended HUVECs was added to one reservoir of the endothelial channel and inverted for 30 minutes to allow cell attachment to the top half of the channel followed by a second seeding with the device upright for 30 minutes to allow cell attachment to the bottom half of the channel. HUVEC solution density was varied with ECM composition as attachment efficiency was dependent on ECM composition. HUVEC seeding densities were determined experimentally to achieve parent vessels with consistent cell densities across each hydrogel formulation (Fig. 1). Collagen: 1.5 M ml−1 for 2 mg ml−1, 2M ml−1 for 3 mg ml−1, and 5 M ml−1 for 6 mg ml−1. Fibrin: 5 M ml−1 for 2.5 mg ml−1, 10 M ml−1 for 5 mg ml−1, and 15 M ml−1 for 15 mg ml−1. DexVS: 20 M ml−1. HUVECs reached confluency and self-assembled into stable parent vessels over 24 hours. Media and chemokines were refreshed every 24 hours and devices were cultured with continual reciprocating flow utilizing gravity-driven flow on a seesaw rocker plate at 0.33 Hz.

Figure 1∣. Multiplexed angiogenesis-on-a-chip.

a, Schematic of microfluidic-based device to study 3D endothelial cell sprouting from an endothelialized parent channel. Endothelial channel (ECh) and chemokine channel (CCh) b-c, Representative images of x-y projection (top) and x-z orthogonal slice (bottom) of parent channels formed within collagen (b) and fibrin (c) hydrogels of varying matrix density. F-actin (cyan), nuclei (magenta), VE-cadherin (yellow). d, Quantifications of diameter (n = 10) and cell density (n ≥ 28) of parent channels from conditions in (b-c). All data presented as mean ± s.d.

2.7. Mechanical testing.

Young’s modulus of each hydrogel was measured using atomic force microscopy (AFM; Nanosurf, Liestal, Switzerland) in contact mode. Indentations were made at a loading rate of 2 μm/s with silicon nitride cantilevers (AppNano, Mountain View, CA) with a nominal spring constant of 0.046 N/m and a 5 μm diameter spherical glass bead. Force-displacement curves were taken at a minimum of 3 regions on each hydrogel and fit to the Hertz model assuming a Poisson’s ratio of 0.5 to estimate the elastic modulus.

2.8. Quantification of hydrogel permeability.

For fibrin and collagen hydrogels: Following fabrication of microfluidic devices and hydrogels as described above, 125 μg/ml 70 kDa conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, D-1823) in PBS was added to each of the 4 ports on the device and incubated overnight at 37°C to allow the fluorescent dextran to permeate the gel. FITC-dextran containing PBS was then removed from all ports, and glass reservoirs (4 mm inner diameter, 20 mm in height, Chemglass, Vineland, NJ, CG-700-05L) were inserted into the ports of the endothelial channel (ECh). A hydrostatic pressure gradient across the hydrogel was applied by adding fresh 70 kDa FITC dextran solution to the glass reservoirs and maintaining the chemokine channel (CCh) at atmospheric pressure. The pressure induced by a given height of fluid was calculated using the equation for hydrostatic pressure

| (1) |

Where P is the hydrostatic pressure, ρ is the density of the fluid (assumed to be that of water, 103 kg/m3), g is the acceleration due to gravity, and h is the height of fluid in the reservoir. The fluid velocity between the two channels was measured using a modified fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) procedure [38]. Using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus FV3000), a 124 μm diameter circle of FITC-dextran was bleached for 2.161 seconds in the interstitial region between the two channels using a 488 nm, 20 mW laser at 60% power at 20x magnification. Immediately after bleaching, the bleached region and a surrounding region of interest (ROI) was imaged every second for a total of 30s. The velocity of the fluid was measured using a custom MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) script to measure displacement of the center of mass of the bleached circle as a function of time. With the known input pressure and measured fluid velocity, the permeability of the hydrogel was calculated using Darcy’s Law in one dimension [39]:

| (2) |

Where k is the permeability of the gel, μ is the viscosity of the fluid (assumed to be the viscosity of water at 37°C, 10−3 Pa s), L is the distance between the channels in the direction of flow (4 mm), v is the velocity of flow across the gel, and ΔP is the difference in pressure across the two channels calculated from (equation 1).

For DexVS hydrogels: Given the low hydraulic permeability values of dextran hydrogels reported previously [20], the Peclet number for experimentally feasible pressure gradients is << 1, precluding the use of FRAP for determining fluid velocity magnitude. Therefore, we modified a mass flux-based approach we developed previously [40] to measure the fluid velocity magnitude for a given pressure gradient and thus determine the hydraulic permeability. Briefly, the total mass flux of fluorescent dextran into a ROI bounded by a source channel with a constant concentration of fluorescent dextran can be determined by measuring the change in fluorescence intensity within the ROI and the fluorescence intensity of the source channel, as previously described [40]. Therefore, to determine the flux due to convection and the fluid velocity magnitude, we first measured flux into the DexVS hydrogel with an imposed pressure gradient (Jtot = total flux), followed by measuring flux with uniform pressure (Jdiff = diffusive flux). Fluid velocity magnitude can then be determined from the definition of mass flux [39]

| (3) |

where I0 is the total pixel intensity within the source channel (assumed to be constant, and verified experimentally as described below), L is the length of the source channel, D is the diameter of the channel, and z is the optical thickness as determined by the point spread function of optical setup.

Two sequential flux measurements were made to determine Jtot and Jdiff. First, 125 μg/ml 70 kDa dextran conjugated with Texas Red (TR, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, D-1830) in PBS was added to the glass reservoirs to induce a 400 Pa pressure drop across the hydrogel, as described above. The input channel was centered in the field of view and imaged at 4x magnification every 5 minutes for 2 hours to determine Jtot. Subsequently, the glass reservoirs were removed, TR-dextran was removed from all ports, and 50 μl of 125 μg/ml 70 kDa FITC-dextran in PBS was added to all ports to maintain constant pressure. The ROI was then re-imaged with the same parameters as the total flux measurement to determine diffusive flux.

The two time-resolved image sets were then analyzed using ImageJ to determine total flux and diffusive flux, respectively. Briefly, a rectangular ROI along the length of the channel was drawn in the hydrogel adjacent to the source channel. The change in total pixel intensity within the ROI was measured over time for TR-dextran and FITC-dextran along with the intensity in the source channel (to justify the constant concentration assumption). With these measurements, Jtot and Jdiff were calculated as previously described [40], and equation 3 was used to determine fluid velocity magnitude. With the measured velocity magnitude and known input pressure gradient, equation 2 was used to determine the hydraulic permeability.

2.9. Mouse implantation.

Hydrogels for mouse implantation were formed in 8 mm diameter PDMS gaskets with 100 μl of hydrogel precursor solution resulting in cylindrical-shaped implants upon PDMS gasket removal. Hydrogels were hydrated for 16 hours in VEGF165 (100 ng ml−1, Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) to promote EC invasion. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines for survival surgery in rodents and the IACUC Policy on Analgesic Use in Animals Undergoing Surgery were followed for all the procedures. Animal experiments for this work were performed in accordance with the protocol approved by the IACUC at the University of Michigan (PRO00007716). Male mice (F1 C57Bl/6XCBA) 12–16 weeks old were anesthetized by isoflurane and treated with Carprofen (5mg/kg, subcutaneously, Rimadyl, Zoetis) for analgesia. The intraperitoneal space and the epididymal fat pad were exposed through a midline incision and secured using an abdominal retractor. The hydrogels (one on each side) were wrapped within fat tissue, sutured in place with 10-0 Nylon sutures, and returned to the abdominal cavity. The muscle and skin layers of the abdominal wall were closed with 5/0 absorbable sutures (AD Surgical). The mice recovered in a clean warmed cage and received another dose of Carprofen 24 hours post recovery or as needed. Hydrogels were retrieved after 7 days. Upon explant, isolated hydrogels were imaged and measured for their cross-sectional area and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution.

2.10. Vibratome processing.

Vibratome sections were processed using a VF-310-0Z Compresstome (Precisionary Instruments, Natick, MA) per manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, hydrogel explant samples were affixed to a specimen column and embedded with 2% w/v agarose. Sections were taken at 200 μm thickness with a speed and oscillation setting of 3 and 4, respectively.

2.11. Fluorescent staining.

Samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with a PBS solution containing Triton X-100 (5% v/v), sucrose (10% w/v), and magnesium chloride (0.6% w/v) for 1 hour each at room temperature. AlexaFluor 488 phalloidin (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) was utilized to visualize F-actin. 4’, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1 μg ml−1) was utilized to visualize cell nucleus. For proliferation studies, EdU was applied for the final 24 hours prior to fixation for each study. EdU fluorescent labelling was performed following the manufacturer’s protocol (ClickIT EdU, Life Technologies). DyLight 649 labelled Ulex Europaeus Agglutinin-1 (UEA, 1:200, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) was utilized to visualize endothelial cell morphology in samples stained with EdU due to EdU ClickIT incompatibility with phalloidin staining. To visualize VE-cadherin, samples were sequentially blocked in bovine serum albumin (0.3% w/v), incubated with primary mouse monoclonal anti-VE-cadherin (1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and incubated with secondary AlexaFluor 647 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (1:1000, Life Technologies) each for 1 hour at room temperature. To visualize mouse endothelial cells in explant hydrogels, samples were stained with Griffonia Simplicifolia Lectin I isolectin B4, DyLight 649 (1:200, Vector Labs).

2.12. Microscopy and image analysis.

Fluorescent images were captured on a Zeiss LSM800 confocal microscope. Parent vessel endothelial cell density and EdU proliferation was quantified by counting DAPI and EdU positive cell nuclei. Invasion depth was quantified as the distance from the parent vessel edge to the tip cell and measured in FIJI. Invasion depth measurements were performed at 100 μm intervals along the parent vessel. Sprout diameter measurements were taken 50 μm away from the parent vessel edge.

2.13. Single vs. multicellular sprout analysis.

Single cell and multicellular sprout analyses were performed manually in FIJI utilizing fluorescent markers of nuclei and UEA (Supplementary Fig. 2a-c). This analysis was performed utilizing single z-slices within a 300 μm z-stack. Single cells were quantified as the number of isolated single cells without connections to other cells. Sprouts were quantified as the number of connected multicellular sprouts with UEA connections from the parent vessel edge to tip cell and a length greater than half the maximum invasion depth per condition. The parent vessel edge was clearly distinguished utilizing single z-slice views.

2.14. FITC diffusion.

To model the diffusion profile of S1P (379 g/mol), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; 389 g/mol) was selected due to the similarity in molecular weight. 50 μl of PBS was first added to the right-hand channel of the angiogenesis-on-a-chip model and then 50 μl of FITC (20 μg/ml diluted in PBS) was added to the left-hand channel such that FITC diffusion flowed from left to right. Timelapse imaging was performed at 5 second intervals to capture fluorescent FITC diffusion through each hydrogel condition.

2.15. Fluorescent microsphere perfusion.

To assess sprout lumenization, a 50 μl solution of 1 μm diameter fluorescent microspheres (1:10,000, ThermoFisher) was added to the endothelial cell channel with 10 μl of PBS added to the chemokine channel to promote microsphere perfusion into sprouts. Sprouts that contained fluorescent microspheres were considered to be lumenized.

2.16. Statistics.

Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), two-sided Student’s t-test, or Pearson’s Correlation where appropriate, with significance indicated by p<0.05. Pearson’s Correlation was performed on sample mean values for each group without accounting for total sample size. Sample size is indicated within corresponding figure legends and all data are presented as mean ± standard deviation.

2.17. Data availability.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Generation of consistent parent vessels in collagen and fibrin hydrogels

We employed a multiplexed, organotypic model that recapitulates 3D EC sprouting morphogenesis from a stable, quiescent endothelium to assess angiogenesis into commonly used natural biopolymer-based hydrogels as a function of matrix density (Fig. 1a) [7]. Specifically, we investigated collagen and fibrin hydrogels over a range of matrix densities explored previously in various models of angiogenesis [16,41]. To fabricate patent arteriole-scale channels, hydrogel precursor solution was injected into micromolded silicone devices and polymerized around acupuncture needles (300 μm diameter) (Fig. 1a). Needle removal yielded hollow channels fully embedded within the user-defined hydrogel, where each device contained a pair of channels connected to media reservoirs. One channel was seeded with a suspension of ECs that adhered and self-assembled into the parent vessel, with VE-cadherin localized to cell-cell junctions 24 hours after seeding (Fig. 1b-c). The resultant parent vessels across collagen and fibrin hydrogel demonstrated no difference in vessel diameter and cell density (Fig. 1b-d). To isolate the interactions between ECs and the ECM, the parent vessels modeled in this work did not include supporting mural cells; however, these devices have the potential to incorporate mural cells outlining the endothelialized channel as demonstrated in previous work [42].

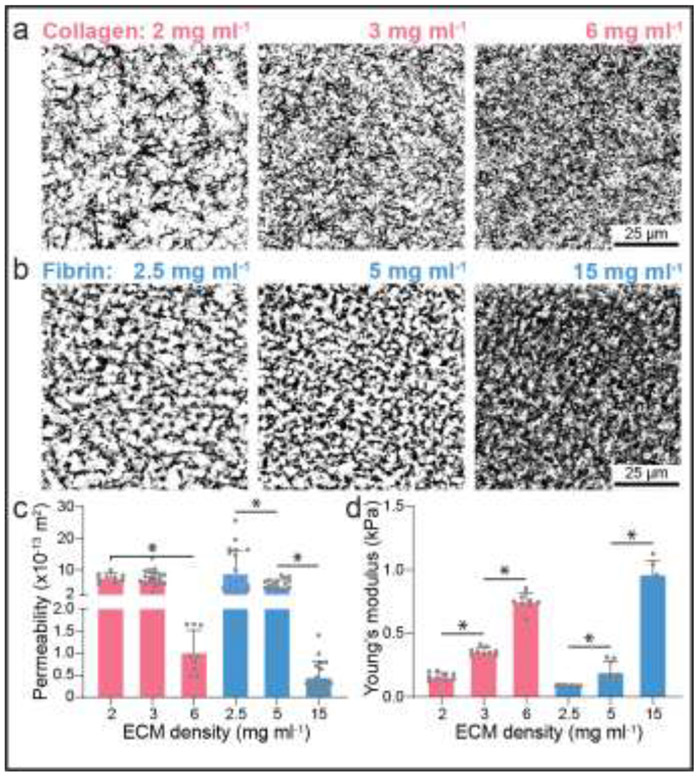

We next characterized properties of collagen and fibrin hydrogels as a function of matrix density (i.e. protein concentration of the gel precursor solution). Utilizing fluorescently labelled ECM proteins, we qualitatively observed increases in matrix density concurrent with decreases in pore size (Fig. 2a-b). Image analysis approaches have been used to assess matrix porosity, but these methods rely on assumptions of equivalence in fluorophore conjugation efficiency and distribution between different ECM proteins. As such, we employed a fluorescent recovery after photobleaching method to assess matrix permeability as a measurable output of matrix porosity. Briefly, devices with each hydrogel composition were saturated with fluorescently labelled 70 kDa dextran overnight. Next, a hydraulic pressure head was applied across the two channels (ECh and CCh) and a region of interest (ROI) was photobleached using a confocal microscope and subsequently imaged to calculate the fluid velocity into the ROI. With a known hydraulic pressure difference and measured fluid velocity, permeability was calculated using Darcy’s law (Equation 2). Employing this assay, we find that increasing matrix density results in decreased levels of permeability (Fig. 2c). Additionally, performing nanoindentation with an atomic force microscope and assuming Hertzian contact, we found increases of matrix stiffness with matrix density confirming previous findings (Fig. 2d) [41,43]. Having characterized two key matrix properties of fibrin and collagen hydrogels previously implicated in angiogenesis [9], we next sought to directly compare angiogenic sprouting in these two biomaterials as a function of matrix density.

Figure 2∣. Matrix stiffness and pore size as a function of matrix density.

a-b, Representative images (max intensity projection) of fluorescently labelled collagen (a) and fibrin (b) hydrogels of varying matrix density. c-d, Matrix permeability (c) and stiffness (d) as a function of matrix density for collagen and fibrin hydrogels; n ≥ 9 (c) and n ≥ 6 (d). All data presented as mean ± s.d.; * indicates a statistically significant comparison with P<0.05 (one-way analysis of variance).

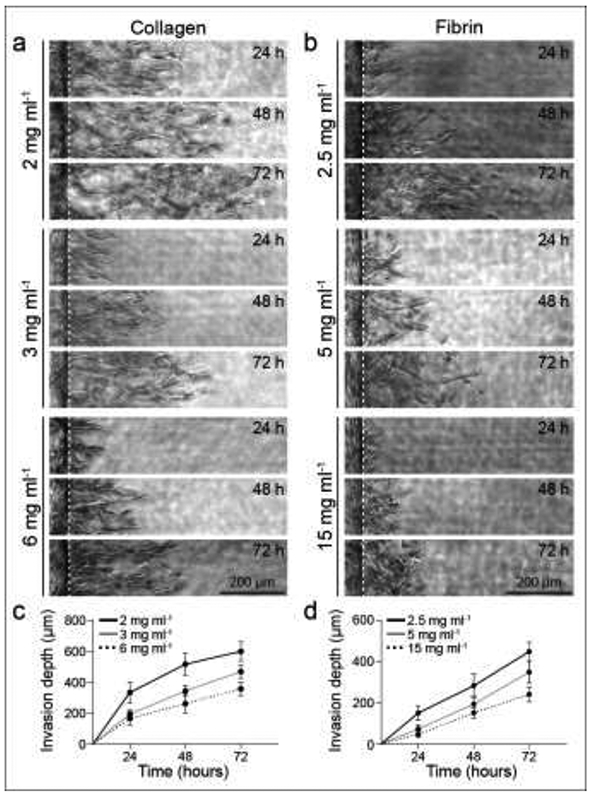

To induce 3D EC invasion into each ECM composition, we utilized well-established pro-angiogenic factors (250 nM sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) and 50 ng ml−1 phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)) that promote EC migration and proliferation [7,20,33]. S1P chemoattractant was added only to the CCh, thus generating a diffusive gradient to initiate EC invasion into the ECM, while pro-mitogenic PMA was supplemented to EGM2 media in both the ECh and CCh (Fig. 1a). To confirm the generation of an S1P gradient, we tracked FITC diffusion from the CCh through each hydrogel condition. Early timepoints of FITC diffusion displayed a logarithmic profile while the gradient formed (5-90 seconds) (Supplementary Fig. 1a-b). However, FITC diffusion profiles became more linear with time (60-685 seconds). Although the linear diffusion profile was achieved at varying timepoints across the hydrogel conditions, this timescale is orders of magnitude smaller than the duration of the cell invasion response (hours to days) (Supplementary Fig. 1c-d). We tracked EC sprout invasion depth over 3 days across each ECM composition, and as expected, invasion depth increased incrementally with culture time (Fig. 3a-d). Across both collagen and fibrin hydrogels, increases in matrix density resulted in decreased invasion depth by 3 days of culture (Fig. 3c-d, Fig. 4c).

Figure 3∣. EC sprouting time course.

a-b, Representative time course images (brightfield) of invading endothelial cells into collagen (a) and fibrin (b) hydrogels with varying matrix densities as indicated. White dashed lines indicate parent vessel edge. c-d, Quantifications of invasion depth over 72 hours for collagen (c) and fibrin (d) hydrogels with varying matrix densities; n ≥ 16. All data presented as mean ± s.d.

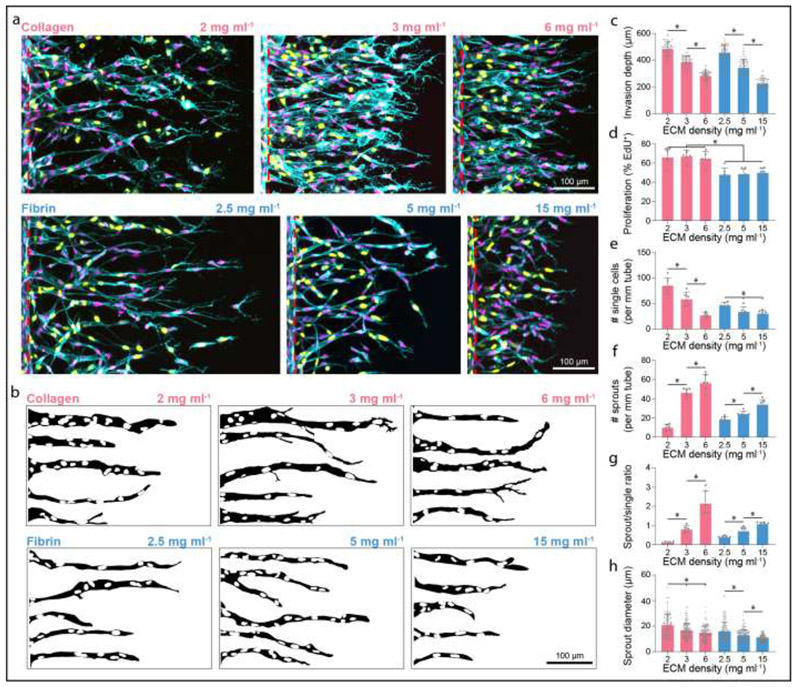

Figure 4∣. Sprout morphometrics in collagen and fibrin hydrogels.

a, Representative images (max intensity projections) of invading endothelial cells into collagen (top) and fibrin (bottom) hydrogels with varying matrix densities as indicated. UEA (cyan), nuclei (magenta), EdU (yellow), red dashed lines indicate parent vessel edge. b, Representative sprout outlines from conditions in (a). c-h, Quantifications of invasion depth (n ≥ 60), proliferation (n = 6), morphology of invading endothelial cells as single cells or multicellular sprouts (n = 6), and sprout diameter (n ≥ 100). All data presented as mean ± s.d.; * indicates a statistically significant comparison with P<0.05 (one-way analysis of variance).

3.2. Endothelial cell sprout morphology in natural and synthetic biomaterials

In addition to sprout invasion depth, we imaged sprouts at the final day 3 timepoint by confocal fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4a-c) and quantified EC proliferation and sprout morphometrics as a function of matrix density. We found that matrix density did not influence proliferation rates, as assayed by EdU incorporation, perhaps due to soluble PMA’s potent enhancement of proliferation in line with our prior findings (Fig. 4d) [7]. However, invaded ECs were more proliferative in collagen compared to fibrin hydrogels (Fig. 4a, d). Prior work from our group has demonstrated that sprout multicellularity portends functional angiogenesis, namely perfusable neovessels with appropriate barrier function [7]. Performing similar morphologic analyses here, ECs were categorized as isolated single cells or multicellular sprouts, and the ratio of sprouts to single cells served as a metric of invasion multicellularity (Supplementary Fig. 2a-c). Due to variations in invasion depth across conditions, we defined sprouts as contiguous multicellular structures with a length greater than half the max invasion depth. We quantified all invaded single cells, which were most abundant at the leading invasive front. Analyzing the morphology of invaded ECs, increasing matrix density in both collagen and fibrin hydrogels resulted in a decrease in the number of single cells, increase in multicellular sprouts, and therefore an increase in sprout:single ratio (Fig. 4a-b, e-g and Supplementary Fig. 2b). Furthermore, increasing matrix density of both collagen and fibrin hydrogels resulted in decreased sprout diameters (Fig. 4a-b, h and Supplementary Fig. 2b). In general, sprouts formed in fibrin hydrogels were smaller in diameter compared to collagen, potentially due to less cell proliferation and thus reduced lateral expansion of the sprout stalk [44].

3D collective cell migration during EC sprouting is necessary but not sufficient for the formation of functional, patent neovessels. To assess whether sprouts in each condition were in fact lumenized, we perfused 1 μm diameter fluorescent microspheres through the endothelial channel and analyzed whether microspheres flowed into invading sprouts. Interestingly, the number of lumenized sprouts increased with matrix density in collagen hydrogels, correlating with the observed increase in multicellular sprouts (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 3a-b). However, in fibrin hydrogels, increasing matrix density resulted in less lumenized sprouts, despite increased numbers of multicellular sprouts (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 3a-b). As sprout diameter was overall diminished in fibrin hydrogels compared to collagen, it is possible that despite more collective EC invasion with decreasing fibrin density, these multicellular sprouts did not reach a sufficient diameter to lumenize (Fig. 4f, h and Supplementary Fig. 3a-b).

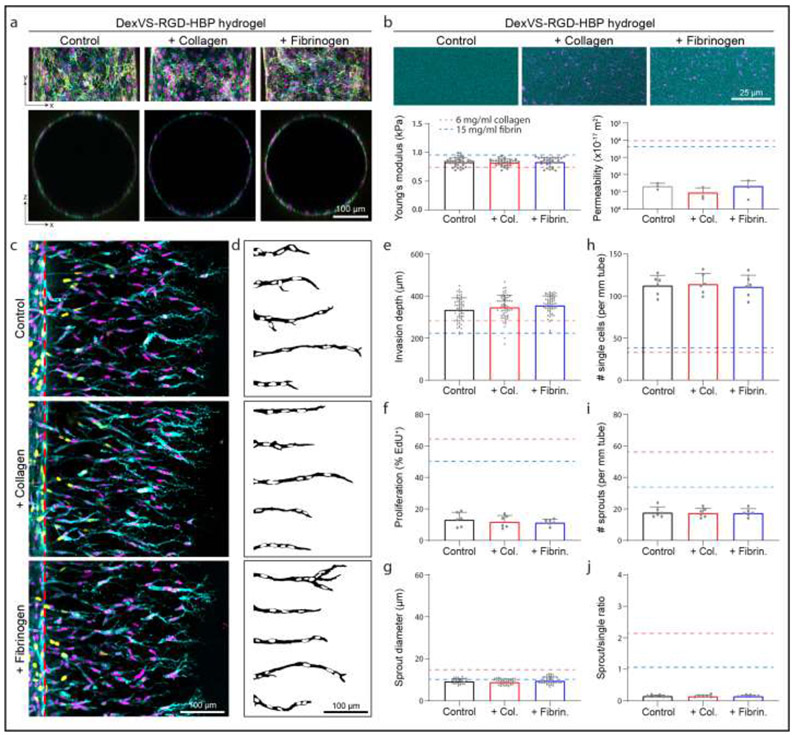

Altering matrix density in collagen and fibrin hydrogels yields concurrent changes in stiffness, porosity, and adhesive ligand density. To further investigate how matrix density in natural hydrogels influences EC sprouting morphogenesis, we next employed synthetic hydrogels that provide orthogonal control over material properties. In previous work, we found that increasing matrix stiffness in synthetic dextran-based hydrogels reduces multicellular sprouting [20]. Thus, here we generated synthetic dextran hydrogels on the lower end of matrix stiffness (while still affording robust hydrogel formation) and altered ligand presentation to probe its influence on EC sprouting morphogenesis. We functionalized dextran, a protein-resistant polysaccharide, with pendant vinyl sulfone groups amenable to peptide conjugation via thiol-ene click chemistry [36]. Unlike other synthetic hydrogel polymers (e.g. polyethylene glycol and hyaluronic acid), dextran-based hydrogels are non-swelling and afford integration with microfluidic devices to maintain the desired device geometries [20]. Dextran vinyl sulfone (DexVS) was crosslinked with an MMP-labile peptide, and functionalized with cell adhesive RGD and heparin-binding peptide. Hydrogel functionalization with heparin-binding peptide enables the incorporation of heparin and subsequently, heparin-binding proteins including collagen and fibrinogen [45]. Parent vessels formed within DexVS hydrogels had equivalent cell density to pure collagen and fibrin hydrogels and were unaffected by enrichment with collagen or fibrin (Fig. 1b-d, 5a). Additionally, enrichment with collagen or fibrinogen did not influence the stiffness nor permeability of DexVS hydrogels (Fig. 5b). The Young’s moduli of DexVS hydrogels was comparable to 6 mg/ml collagen and 15 mg/ml fibrinogen, however, permeability was more than 2 orders of magnitude lower than either natural material (Fig. 2c-d, Fig. 5b). Analyzing sprout morphometrics after 3 days of S1P- and PMA-driven sprouting, we found that the incorporation of collagen or fibrinogen into synthetic DexVS hydrogels did not influence invasion depth, proliferation, sprout multicellularity, or diameter (Fig. 5c-j). Compared to sprouts in 6 mg/ml collagen or 15 mg/ml fibrin, sprouts in DexVS hydrogels infrequently contained proliferating ECs, possessed limited multicellularity and an abundance of single invading cells, and had smaller diameters (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Figure 5∣. Sprout morphometrics in DexVS hydrogels.

a, Representative images of x-y projection (top) and x-z orthogonal slice (bottom) of parent channels formed within DexVS hydrogels enriched with ECM proteins. F-actin (cyan), nuclei (magenta), VE-cadherin (yellow). b, Fluorescent images and quantifications of matrix stiffness and permeability. c, Representative images (max intensity projections) of invading endothelial cells into DexVS hydrogels enriched with ECM proteins as indicated. UEA (cyan), nucleus (magenta), EdU (yellow), red dashed lines indicate parent vessel edge. d, Representative sprout outlines from conditions in (d). e-j, Quantifications of invasion depth (n ≥ 60), proliferation (n = 6), sprout diameter (n ≥ 33), and morphology of invading endothelial cells as single cells or multicellular sprouts (n = 6). Dashed lines in (b, e-j) indicate values from 6 mg/ml collagen and 15 mg/ml fibrin studies. All data presented as mean ± s.d.

3.3. Enhancing angiogenesis in synthetic DexVS hydrogels

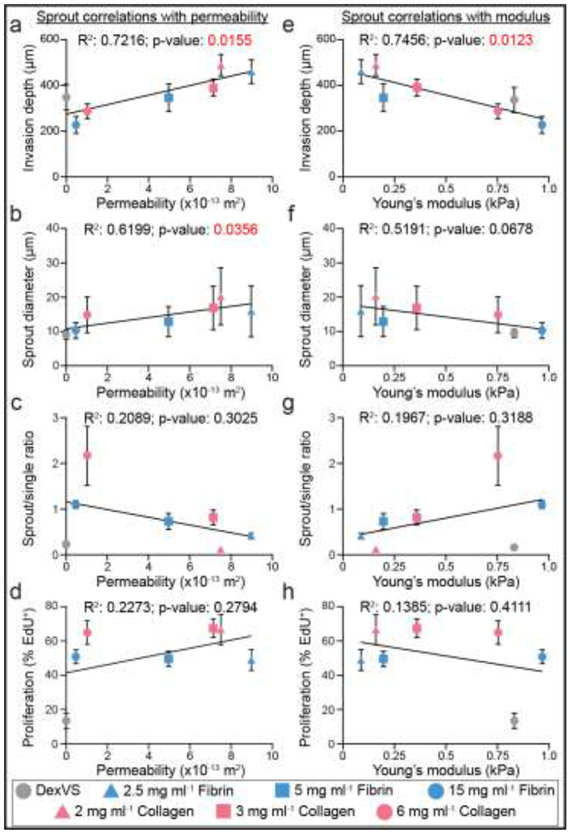

To examine relationships between key sprout morphometrics and matrix porosity or stiffness, we performed Pearson’s correlation analyses between matrix permeability and modulus with sprout invasion depth, diameter, multicellularity, and proliferation (Fig. 6a-h). Of all analyses across collagen, fibrin and DexVS hydrogels, we found matrix permeability to significantly, positively correlate with both invasion depth and sprout diameter (Fig. 6a-b). Young’s modulus significantly anti-correlated only with invasion depth (Fig. 6e). This correlation is in line with the previous observations that matrix density and crosslinking (which both contribute to hydrogel stiffness) hamper angiogenic invasion. Performing these analyses with only natural-derived material conditions resulted in significant correlations between matrix permeability with invasion depth and Young’s modulus with invasion depth (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Figure 6∣. Pearson’s correlations between matrix permeability and modulus with sprout morphometrics.

a-d, Pearson’s correlations between matrix permeability and sprout morphometrics. e-h, Pearson’s correlations between matrix stiffness and sprout morphometrics. R2 and p-values indicated within each plot.

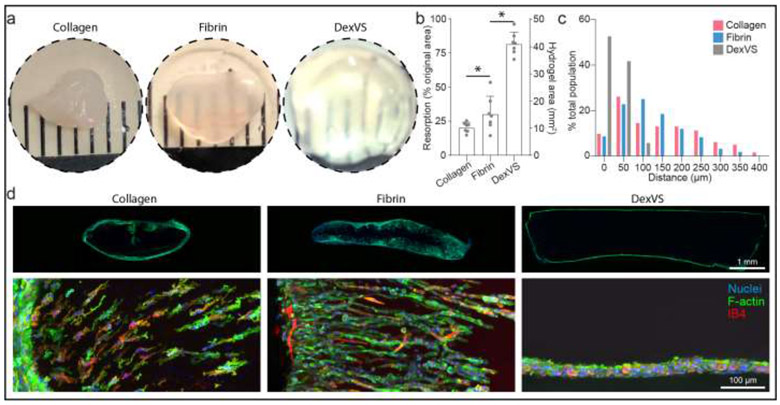

We next investigated whether matrix porosity would have a similar influence on cell invasion in an in vivo context. We implanted collagen, fibrin, and DexVS hydrogels into murine epididymal fat pads and assessed cell invasion into hydrogel implants retrieved after 7 days. Hydrogels of the highest matrix density explored in these studies were selected for implantation (collagen: 6 mg/ml, fibrin: 15mg/ml), as their moduli were most similar to DexVS hydrogels. After 7 days of implantation, collagen and fibrin hydrogel implants contained numerous invading cells with a subset of isolectin B4 (IB4) positive ECs, while DexVS implants possessed cells exclusively restricted to the hydrogel periphery (Fig. 7c-d and Supplementary Fig. 6). Cell invasion is a requirement for angiogenesis, and these results support previous observations that both natural materials are angio-conductive. Flowever, we found that even when formulated at high density, collagen and fibrin hydrogels rapidly resorbed in vivo, evident in a marked reduction in the projected area of initially cylindrical implants (Fig. 7a-b). In contrast, synthetic DexVS hydrogels resorbed more slowly and better maintained initial implant cross-sectional area and overall geometry (Fig. 7a-b). As degradation mechanism and kinetics of synthetic hydrogels can be readily tuned, this class of biomaterials is attractive for applications that require longer-term shape/size control.

Figure 7∣. In vivo cell migration response.

a, Images of hydrogel explants after 7 days implantation into fat pad. b, Quantification of hydrogel resorption and final hydrogel area (n = 7). c, Histogram of cell migration invasion distance into implanted hydrogels. d, Images of vibratome sections of whole implants (top row) and cell invasion (bottom row). Nuclei (blue), F-actin (green), Isolectin B4 (red). All data presented as mean ± s.d.; * indicates a statistically significant comparison with P<0.05 (one-way analysis of variance).

As the resorption rate of natural materials cannot be easily tuned without influencing properties that inhibit EC invasion, we instead focused on improving lumenized sprout formation in DexVS hydrogels by introducing microporosity into an otherwise nanoporous bulk hydrogel. We employed an established technique to generate gelatin microgels with defined diameter using a microfluidic droplet generator (Fig. 8a) [46]. 20 μm diameter gelatin microgels were generated and swelled to 27.85 ± 1.32 μm upon equilibrium swelling in PBS after the liquid-oil emulsion phase was broken. This diameter was selected based on prior work utilizing photoablation of collagen hydrogels and were of similar caliber to lumenized sprout diameters (Fig. 8b-d) [47]. To incorporate gelatin microgels into DexVS hydrogels, we added a chilled solution of gelatin microgels into the precursor hydrogel to occupy 7.3% v/v space and subsequently melted the gelatin microgels upon incubation at 37°C, leading to micro-scale pore formation throughout the synthetic hydrogel (Fig. 8e). Performing in vitro sprouting studies over 3 days, we found that DexVS hydrogels imbued with microporosity increased endothelial sprout diameter, but not invasion depth (Fig. 8f-h). Larger sprout diameters in microporous DexVS coincided with sprout lumenization, as evidenced by the entry of fluorescent microspheres (∅=1 μm) into sprouts upon addition to the parent vessel. In stark contrast, microspheres did not enter sprouts in nanoporous DexVS controls (Fig. 8f and Supplementary Fig. 7). Lastly, to assess the impact of gel porosity on endothelial invasion in vivo, we implanted control or microporous DexVS hydrogels for 7 days in murine epididymal fat pad. We noted no difference in the degree of resorption between control and porous DexVS hydrogels, with both maintaining overall implant shape and size (Fig. 8i-j). However, cell invasion was enhanced in microporous DexVS hydrogels, with some cells positive for IB4 (Fig. 8k-l, Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 8). Overall, utilizing a composite materials approach to enhance porosity of synthetic DexVS hydrogels with gelatin microgels increased sprout diameter and lumenization in vitro and cell invasion in vivo.

DISCUSSION

To identify physical properties of biomaterials that influence angiogenesis, we utilized a recently established multiplexed angiogenesis-on-a-chip platform to compare EC sprouting morphogenesis in natural and synthetic hydrogels. We measured the Young’s modulus and hydraulic permeability of type I collagen, fibrin, and DexVS hydrogels while also quantifying morphometrics of EC sprouting into these materials. We found that matrix permeability significantly positively correlated with EC invasion depth and sprout diameter, while hydrogel stiffness significantly anti-correlated with EC invasion depth. Nanoporous synthetic DexVS hydrogels with low permeability prevented sprout lumenization in vitro and cell infiltration in vivo, although implanted DexVS hydrogels maintained their initial shape better than natural materials – a critical feature for the long-term function of tissue engineered implants. To address the impaired sprouting and limited cell infiltration of this synthetic hydrogel, we developed a composite materials approach to generate microporosity using sacrificial gelatin microgels. Incorporating microporosity into nanoporous DexVS hydrogels enhanced sprout diameter in our in vitro angiogenesis model and enhanced cell invasion upon hydrogel implantation in vivo. These studies highlight porosity as a critical physical feature of hydrogels required for the invasion of angiogenic sprouts and establish a promising approach that will extend the application space of synthetic hydrogels. These efforts add to the rapidly growing set of critical design features and strategies to tune synthetic hydrogel properties that can address the outstanding challenge of vascularizing implantable, engineered tissues and organs.

Natural biopolymers such as type I collagen and fibrin hydrogels have been extensively explored for supporting neovascularization [7,16,41]. These materials readily support the recruitment of cells that mediate wound repair (e.g. mesenchymal, endothelial, and immune cells) followed by subsequent matrix resorption and remodeling that replaces the implanted material with cell-produced matrix. Rapid revision and replacement of the implant may be ideal in contexts such as wound repair, but these features are likely suboptimal for tissue or organ replacement therapies that require long-term persistence of the biomaterial-based implant. For example, recent advances in biomaterial and stem cell technologies indicate promise for engineering β-cell-containing, extra-pancreatic implants to treat type I diabetes [48,49]. However, the post-implantation survival, vascular integration, and long-term function of such implants requires careful balance between (1) hydrogel degradation to support host angiogenesis and (2) maintenance of mechanical stability to support incorporated parenchymal cells such as stem cell-derived β-cells or donor islets [50]. By virtue of their tunable degradative mechanisms and kinetics, synthetic hydrogels provide a potential route to striking such a balance. However, angiogenesis within synthetic hydrogels has in general been limited due to the nanoscale pore size of this class of materials, which hampers cell migration.

Towards the development of synthetic hydrogels that robustly support neovascularization, we employed a composite hydrogel approach to decouple hydrogel porosity from crosslinking and stiffness. We utilized cell-scale sacrificial gelatin microgels to produce hydrogel micropores (27 μm diameter, 7.3 % v/v) within synthetic DexVS hydrogels. Microporous DexVS hydrogels supported sprout lumenization in our in vitro model of angiogenesis and promoted cell invasion following implantation to the mouse fat pad. However, microporous DexVS hydrogels still require further optimization as the cell invasion response was not as efficient when compared to collagen and fibrin hydrogel implants. Future studies exploring the large parameter space of porogen properties (e.g. size, shape, and volume fraction) will be essential to realizing the full potential of this approach.

A variety of strategies have previously been implemented to enhance the porosity of synthetic hydrogels. Gas-foaming and salt-leaching techniques within PLGA scaffolds produce pore sizes on the larger length-scale (100-500 μm); such approaches have indicated heparin or growth factor functionalized PLGA scaffolds promotes localized angiogenesis [51,52]. At smaller length-scales, microporous annealed particle (MAP) hydrogels consisting of annealed microgels with interconnected pore space have shown promise for enhancing angiogenesis during dermal wound repair [21]. With either of these techniques, the resulting pores are heterogenous. Salt-leaching or gas foaming result in heterogeneously sized pores while the pore space in MAP gels lying between microgels possess poorly defined shapes. An overall challenge in connecting porosity to angiogenesis lies in both consistently generating and accurately measuring porosity and pore properties. Aspects including pore size, volume fraction, connectivity, shape, and even orientation all likely converge to dictate the cell response [53-56]. For example, consider the impact of equal volume fractions of disconnected larger diameter pores versus smaller, interconnected pores on cell invasion. Here, we developed an alternative approach to changing hydrogel porosity by quantifying matrix permeability, which incorporates both pore size and geometry to produce an effective resistance. Indeed, matrix permeability has been well-characterized as a biologically significant parameter governing cartilage deformation, lymphatic drainage and cytoskeletal dynamics [57-60]. In this work, matrix permeability significantly correlated with EC invasion depth and sprout diameter, and may be an additional matrix property to consider in the design of pro-angiogenic biomaterials to promote collective cell invasion, a process that has recently been linked to a fluid-like phase transition [55].

Beyond matrix porosity, other matrix properties have been shown to influence cell behavior including during sprouting morphogenesis. This work also identified matrix stiffness to significantly anti-correlate with EC invasion depth (Fig. 6e), while previous work modulating collagen hydrogel stiffness has shown conflicting responses [41,44,61-63]. Increasing matrix stiffness via glutaraldehyde reduces sprout response while increasing matrix stiffness with ribose preglycation increases the sprout response. Underlying these methods to increase collagen stiffness are changes to the susceptibility of matrix degradation, where glutaraldehyde introduces non-enzymatically degradable crosslinks thus hampering cell-mediated proteolysis. Indeed, previous work from our group utilizing synthetic dextran-based hydrogels has parsed the roles of matrix stiffness and degradability highlighting that multicellular sprouting requires a balance between these two parameters [20]. In addition to stiffness, viscoelastic and non-linear mechanical properties have recently been demonstrated to influence cell migration and vasculogenic self-assembly of EC networks [26,64].

Lastly, one should take into account that most studies only define and characterize initial ECM properties; however, cell-mediated processes such as proteolysis, matrix synthesis, and contractility dynamically alter the biochemical and biophysical properties of ECM immediately upon contact between cells and material [65]. The inclusion of mural support cells or stromal fibroblasts in such microphysiologic devices presented here may provide a platform to assess how heterotypic cell interactions between cell types and the matrix influence angiogenesis. For example, more migratory and proteolytically active stromal cells may produce local changes to matrix porosity to enhance angiogenesis. In contrast, myofibroblasts that excessively deposit and crosslink matrix may produce more dense and stiff matrix environments that inhibit angiogenesis. These dynamic changes to the ECM are likely accelerated and even more complex in vivo, where cell densities and the number of different cell populations are comparatively greater. Characterization of these dynamic ECM changes and their influence on angiogenesis requires the integration of recent enabling technologies such as metabolic labelling of secreted proteins to examine matrix deposition and ligand presentation [66], FRET-based protease microgels to assess matrix proteolysis [67], magnetic bead microrheology to spatially map matrix stiffness [68,69], and acoustically responsive scaffolds to spatiotemporally control the generation of pores [70]. Integrating such technologies with tunable synthetic biomaterials will elucidate new cell-matrix interactions that govern sprouting angiogenesis towards enhancing the vascularization of biomaterial implants for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (HL124322, EB030474) and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (1-INO-2020-916-A-N). W.Y.W acknowledges financial support from the University of Michigan Rackham Merit Fellowship and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (DGE1256260). S.A.H. acknowledges financial support from the National Institutes of Health (T32HL69768). C.D.D. acknowledges financial support from the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (F31HL152501) and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (DGE1256260). M.A.W. acknowledges financial support from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (DGE1256260).

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Rouwkema J, Koopman BFJM, Blitterswijk CAV, Dhert WJA, Malda J, Supply of nutrients to cells in engineered tissues, Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev 26 (2009) 163–178. 10.5661/bger-26-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Novosel EC, Kleinhans C, Kluger PJ, Vascularization is the key challenge in tissue engineering, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 63 (2011) 300–311. 10.1016/j.addr.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pellegata AF, Tedeschi AM, De Coppi P, Whole organ tissue vascularization: Engineering the tree to develop the fruits, Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol 6 (2018) 56. 10.3389/fbioe.2018.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Francavilla C, Maddaluno L, Cavallaro U, The functional role of cell adhesion molecules in tumor angiogenesis, Semin. Cancer Biol 19 (2009) 298–309. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Potente M, Gerhardt H, Carmeliet P, Basic and Therapeutic Aspects of Angiogenesis, Cell. 146 (2011) 873–887. 10.1016/J.CELL.2011.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cheng G, Liao S, Wong HK, Lacorre DA, Di Tomaso E, Au P, Fukumura D, Jain RK, Munn LL, Engineered blood vessel networks connect to host vasculature via wrapping-and-tapping anastomosis, Blood. 118 (2011) 4740–4749. 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wang WY, Lin D, Jarman EH, Polacheck WJ, Baker BM, Functional angiogenesis requires microenvironmental cues balancing endothelial cell migration and proliferation, Lab Chip. 20 (2020) 1153–1166. 10.1039/c9lc01170f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Siemann DW, The unique characteristics of tumor vasculature and preclinical evidence for its selective disruption by Tumor-Vascular Disrupting Agents, Cancer Treat. Rev 37 (2011) 63–74. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Crosby CO, Zoldan J, Mimicking the physical cues of the ECM in angiogenic biomaterials, Regen. Biomater 6 (2019) 61–73. 10.1093/rb/rbz003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Caliari SR, Burdick JA, A practical guide to hydrogels for cell culture., Nat. Methods 13 (2016) 405–14. 10.1038/nmeth.3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Li L, Eyckmans J, Chen CS, Designer biomaterials for mechanobiology, Nat. Mater 16 (2017) 1164–1168. 10.1038/nmat5049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nowak-Sliwinska P, Alitalo K, Allen E, Anisimov A, Aplin AC, Auerbach R, Augustin HG, Bates DO, van Beijnum JR, Bender RHF, Bergers G, Bikfalvi A, Bischoff J, Böck BC, Brooks PC, Bussolino F, Cakir B, Carmeliet P, Castranova D, Cimpean AM, Cleaver O, Coukos G, Davis GE, De Palma M, Dimberg A, Dings RPM, Djonov V, Dudley AC, Dufton NP, Fendt SM, Ferrara N, Fruttiger M, Fukumura D, Ghesquière B, Gong Y, Griffin RJ, Harris AL, Hughes CCW, Hultgren NW, Iruela-Arispe ML, Irving M, Jain RK, Kalluri R, Kalucka J, Kerbel RS, Kitajewski J, Klaassen I, Kleinmann HK, Koolwijk P, Kuczynski E, Kwak BR, Marien K, Melero-Martin JM, Munn LL, Nicosia RF, Noel A, Nurro J, Olsson AK, Petrova TV, Pietras K, Pili R, Pollard JW, Post MJ, Quax PHA, Rabinovich GA, Raica M, Randi AM, Ribatti D, Ruegg C, Schlingemann RO, Schulte-Merker S, Smith LEH, Song JW, Stacker SA, Stalin J, Stratman AN, Van de Velde M, van Hinsbergh VWM, Vermeulen PB, Waltenberger J, Weinstein BM, Xin H, Yetkin-Arik B, Yla-Herttuala S, Yoder MC, Griffioen AW, Consensus guidelines for the use and interpretation of angiogenesis assays, Springer Netherlands, 2018. 10.1007/s10456-018-9613-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Scott JE, Proteoglycan-fibrillar collagen interactions, Biochem. J 252 (1988) 313–323. 10.1042/bj2520313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, Lakins JN, Egeblad M, Erler JT, Fong SFT, Csiszar K, Giaccia A, Weninger W, Yamauchi M, Gasser DL, Weaver VM, Matrix Crosslinking Forces Tumor Progression by Enhancing Integrin Signaling, Cell. 139 (2009) 891–906. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tonnesen MG, Feng X, Clark RAFF, Angiogenesis in wound healing, J. Investig. Dermatology Symp. Proc 5 (2000) 40–46. 10.1046/j.1087-0024.2000.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ghajar CM, Chen X, Harris JW, Suresh V, Hughes CCW, Jeon NL, Putnam AJ, George SC, The effect of matrix density on the regulation of 3-D capillary morphogenesis., Biophys. J 94 (2008) 1930–41. 10.1529/biophysj.107.120774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Shamloo A, Heilshorn SC, Matrix density mediates polarization and lumen formation of endothelial sprouts in VEGF gradients, Lab Chip. 10 (2010) 3061–3068. 10.1039/c005069e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Vernon RB, Sage EH, A novel, quantitative model for study of endothelial cell migration and sprout formation within three-dimensional collagen matrices, Microvasc. Res 57 (1999) 118–133. 10.1006/mvre.1998.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Vining KH, Mooney DJ, Mechanical forces direct stem cell behaviour in development and regeneration, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 18 (2017) 728–742. 10.1038/nrm.2017.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Trappmann B, Baker BM, Polacheck WJ, Choi CK, Burdick JA, Chen CS, Matrix degradability controls multicellularity of 3D cell migration, Nat. Commun 8 (2017) 371. 10.1038/s41467-017-00418-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Griffin DR, Weaver WM, Scumpia PO, Di Carlo D, Segura T, Accelerated wound healing by injectable microporous gel scaffolds assembled from annealed building blocks, Nat. Mater 14 (2015) 737–744. 10.1038/nmat4294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sokic S, Papavasiliou G, Controlled Proteolytic Cleavage Site Presentation in Biomimetic PEGDA Hydrogels Enhances Neovascularization In Vitro, Tissue Eng. Part A 18 (2012) 2477–2486. 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wisdom KM, Adebowale K, Chang J, Lee JY, Nam S, Desai R, Rossen NS, Rafat M, West RB, Hodgson L, Chaudhuri O, Matrix mechanical plasticity regulates cancer cell migration through confining microenvironments, Nat. Commun 9 (2018) 1–13. 10.1038/s41467-018-06641-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Li S, Nih LR, Bachman H, Fei P, Li Y, Nam E, Dimatteo R, Carmichael ST, Barker TH, Segura T, Hydrogels with precisely controlled integrin activation dictate vascular patterning and permeability, Nat. Mater 16 (2017). 10.1038/nmat4954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Martino MM, Brkic S, Bovo E, Burger M, Schaefer DJ, Wolff T, Gürke L, Briquez PS, Larsson HM, Gianni-Barrera R, Hubbell JA, Banfi A, Extracellular matrix and growth factor engineering for controlled angiogenesis in regenerative medicine, Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol 3 (2015) 45. 10.3389/fbioe.2015.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wei Z, Schnellmann R, Pruitt HC, Gerecht S, Hydrogel Network Dynamics Regulate Vascular Morphogenesis, Cell Stem Cell. 27 (2020) 798–812.e6. 10.1016/j.stem.2020.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Heiss M, Hellström M, Kalén M, May T, Weber H, Hecker M, Augustin HG, Korff T, Endothelial cell spheroids as a versatile tool to study angiogenesis in vitro, FASEB J. 29 (2015) 3076–3084. 10.1096/fj.14-267633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Boucher JM, Clark RP, Chong DC, Citrin KM, Wylie LA, Bautch VL, Dynamic alterations in decoy VEGF receptor-1 stability regulate angiogenesis, Nat. Commun 8 (2017) 1–15. 10.1038/ncomms15699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kosyakova N, Kao DD, Figetakis M, López-Giráldez F, Spindler S, Graham M, James KJ, Won Shin J, Liu X, Tietjen GT, Pober JS, Chang WG, Differential functional roles of fibroblasts and pericytes in the formation of tissue-engineered microvascular networks in vitro, Npj Regen. Med 5 (2020) 1–12. 10.1038/s41536-019-0086-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Turturro MV, Christenson MC, Larson JC, Young DA, Brey EM, Papavasiliou G, MMP-Sensitive PEG Diacrylate Hydrogels with Spatial Variations in Matrix Properties Stimulate Directional Vascular Sprout Formation, PLoS One. 8 (2013) e58897. 10.1371/journal.pone.0058897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Margolis EA, Cleveland DS, Kong Y, Beamish JA, Wang WY, Baker B, Putnam A, Stromal Cell Identity Modulates Vascular Morphogenesis in a Microvasculature-on-a-Chip Platform, Lab Chip. (2021). 10.1039/d0lc01092h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Akbari E, Spychalski GB, Song JW, Microfluidic approaches to the study of angiogenesis and the microcirculation, Microcirculation. 24 (2017) e12363. 10.1111/micc.12363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Nguyen D-HT, Stapleton SC, Yang MT, Cha SS, Choi CK, a Galie P, Chen CS, Biomimetic model to reconstitute angiogenic sprouting morphogenesis in vitro., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110 (2013) 6712–6717. 10.1073/pnas.1221526110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Polacheck WJ, Kutys ML, Yang J, Eyckmans J, Wu Y, Vasavada H, Hirschi KK, Chen CS, A non-canonical Notch complex regulates adherens junctions and vascular barrier function, Nature. 552 (2017) 258–262. 10.1038/nature24998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yu Y, Chau Y, One-step “click” method for generating vinyl sulfone groups on hydroxyl-containing water-soluble polymers, Biomacromolecules. 13 (2012) 937–942. 10.1021/bm2014476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Matera DL, DiLillo KM, Smith MR, Davidson CD, Parikh R, Said M, Wilke CA, Lombaert IM, Arnold KB, Moore BB, Baker BM, Microengineered 3D pulmonary interstitial mimetics highlight a critical role for matrix degradation in myofibroblast differentiation, Sci. Adv 6 (2020) eabb5069. 10.1126/sciadv.abb5069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Matera DL, Wang WY, Smith MR, Shikanov A, Baker BM, Fiber Density Modulates Cell Spreading in 3D Interstitial Matrix Mimetics, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 5 (2019) 2965–2975. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b00141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bonvin C, Overney J, Shieh AC, Dixon JB, Swartz MA, A multichamber fluidic device for 3D cultures under interstitial flow with live imaging: Development, characterization, and applications, Biotechnol. Bioeng 105 (2010) 982–991. 10.1002/bit.22608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Deen WM, Analysis of Transport Phenomena, Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Polacheck WJ, Kutys ML, Tefft JB, Chen CS, Microfabricated blood vessels for modeling the vascular transport barrier, Nat. Protoc 14 (2019) 1425–1454. 10.1038/s41596-019-0144-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bordeleau F, Mason BN, Lollis EM, Mazzola M, Zanotelli MR, Somasegar S, Califano JP, Montague C, LaValley DJ, Huynh J, Mencia-Trinchant N, Negrón Abril YL, Hassane DC, Bonassar LJ, Butcher JT, Weiss RS, Reinhart-King CA, Matrix stiffening promotes a tumor vasculature phenotype, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 114 (2017) 492–497. 10.1073/pnas.1613855114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Alimperti S, Mirabella T, Bajaj V, Polacheck W, Pirone DM, Duffield J, Eyckmans J, Assoian RK, Chen CS, Three-dimensional biomimetic vascular model reveals a RhoA, Rac1, and N -cadherin balance in mural cell–endothelial cell-regulated barrier function, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 114 (2017) 8758–8763. 10.1073/pnas.1618333114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Duong H, Wu B, Tawil B, Modulation of 3D fibrin matrix stiffness by intrinsic fibrinogen-thrombin compositions and by extrinsic cellular activity, Tissue Eng. - Part A 15 (2009) 1865–1876. 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Wang WY, Jarman EH, Lin D, Baker BM, Dynamic Endothelial Stalk Cell–Matrix Interactions Regulate Angiogenic Sprout Diameter, Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol 9 (2021) 620128. 10.3389/fbioe.2021.620128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Martino MM, Briquez PS, Ranga A, Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA, Heparin-binding domain of fibrin(ogen) binds growth factors and promotes tissue repair when incorporated within a synthetic matrix, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 110 (2013) 4563–4568. 10.1073/pnas.1221602110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Mao AS, Shin JW, Utech S, Wang H, Uzun O, Li W, Cooper M, Hu Y, Zhang L, Weitz DA, Mooney DJ, Deterministic encapsulation of single cells in thin tunable microgels for niche modelling and therapeutic delivery, Nat. Mater 16 (2017) 236–243. 10.1038/nmat4781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Arakawa C, Gunnarsson C, Howard C, Bernabeu M, Phong K, Yang E, DeForest CA, Smith JD, Zheng Y, Biophysical and biomolecular interactions of malaria-infected erythrocytes in engineered human capillaries, Sci. Adv 6 (2020) eaay7243. 10.1126/sciadv.aay7243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Headen DM, Woodward KB, Coronel MM, Shrestha P, Weaver JD, Zhao H, Tan M, Hunckler MD, Bowen WS, Johnson CT, Shea L, Yolcu ES, García AJ, Shirwan H, Local immunomodulation with Fas ligand-engineered biomaterials achieves allogeneic islet graft acceptance, Nat. Mater 17 (2018) 732–739. 10.1038/s41563-018-0099-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Weaver JD, Headen DM, Hunckler MD, Coronel MM, Stabler CL, García AJ, Design of a vascularized synthetic poly(ethylene glycol) macroencapsulation device for islet transplantation, Biomaterials. 172 (2018) 54–65. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Bowers DT, Song W, Wang LH, Ma M, Engineering the vasculature for islet transplantation, Acta Biomater. 95 (2019) 131–151. 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Chung HJ, Kim HK, Yoon JJ, Park TG, Heparin immobilized porous PLGA microspheres for angiogenic growth factor delivery, Pharm. Res 23 (2006) 1835–1841. 10.1007/s11095-006-9039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Elcin AE, Elcin YM, Localized angiogenesis induced by human vascular endothelial growth factor-activated PLGA sponge, Tissue Eng. 12 (2006) 959–968. 10.1089/ten.2006.12.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ilina O, Gritsenko PG, Syga S, Lippoldt J, La Porta CAM, Chepizhko O, Grosser S, Vullings M, Bakker GJ, Starruß J, Bult P, Zapperi S, Käs JA, Deutsch A, Friedl P, Cell–cell adhesion and 3D matrix confinement determine jamming transitions in breast cancer invasion, Nat. Cell Biol 22 (2020) 1103–1115. 10.1038/s41556-020-0552-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Tien J, Ghani U, Dance YW, Seibel AJ, Karakan MÇ, Ekinci KL, Nelson CM, Matrix Pore Size Governs Escape of Human Breast Cancer Cells from a Microtumor to an Empty Cavity, IScience. 23 (2020) 101673. 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Kang W, Ferruzzi J, Spatarelu C-P, Han YL, Sharma Y, Koehler S, Butler J, Roblyer D, Zaman M, Guo M, Chen Z, Pegoraro A, Fredberg J, Tumor invasion as non-equilibrium phase separation, BioRxiv. (2020) 2020.04.28.066845. 10.1101/2020.04.28.066845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Dumont CM, Carlson MA, Munsell MK, Ciciriello AJ, Strnadova K, Park J, Cummings BJ, Anderson AJ, Shea LD, Aligned hydrogel tubes guide regeneration following spinal cord injury, Acta Biomater. 86 (2019) 312–322. 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.12.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Quinn TM, Dierickx P, Grodzinsky AJ, Glycosaminoglycan network geometry may contribute to anisotropic hydraulic permeability in cartilage under compression, J. Biomech 34 (2001) 1483–1490. 10.1016/S0021-9290(01)00103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Swartz MA, Kaipainen A, Netti PA, Brekken C, Boucher Y, Grodzinsky AJ, Jain RK, Mechanics of interstitial-lymphatic fluid transport: Theoretical foundation and experimental validation, J. Biomech 32 (1999) 1297–1307. 10.1016/S0021-9290(99)00125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Mitchison TJ, Charras GT, Mahadevan L, Implications of a poroelastic cytoplasm for the dynamics of animal cell shape, Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 19 (2008) 215–223. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Moeendarbary E, Valon L, Fritzsche M, Harris AR, Moulding DA, Thrasher AJ, Stride E, Mahadevan L, Charras GT, The cytoplasm of living cells behaves as a poroelastic material, Nat. Mater 12 (2013) 253–261. 10.1038/nmat3517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Lee PF, Bai Y, Smith RL, Bayless KJ, Yeh AT, Angiogenic responses are enhanced in mechanically and microscopically characterized, microbial transglutaminase crosslinked collagen matrices with increased stiffness, Acta Biomater. 9 (2013) 7178–7190. 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Berger AJ, Linsmeier KM, Kreeger PK, Masters KS, Decoupling the effects of stiffness and fiber density on cellular behaviors via an interpenetrating network of gelatin-methacrylate and collagen, Biomaterials. 141 (2017) 125–135. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Kuzuya M, Satake S, Ai S, Asai T, Kanda S, Ramos MA, Miura H, Ueda M, Iguchi A, Inhibition of angiogenesis on glycated collagen lattices, Diabetologia. 41 (1998) 491–499. 10.1007/s001250050937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Davidson CD, Jayco DKP, Wang WY, Shikanov A, Baker BM, Fiber Crimp Confers Matrix Mechanical Nonlinearity, Regulates Endothelial Cell Mechanosensing, and Promotes Microvascular Network Formation, J. Biomech. Eng 142 (2020). 10.1115/1.4048191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Van Helvert S, Storm C, Friedl P, Mechanoreciprocity in cell migration, Nat. Cell Biol 20 (2018) 8–20. 10.1038/s41556-017-0012-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Loebel J, Mauck C, Burdick RL, Local nascent protein deposition and remodeling guide mesenchymal stromal cell mechanosensing and fate in three-dimensional hydrogels, Nat. Mater in press (2019) 1. 10.1038/s41563-019-0307-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Shin DS, Tokuda EY, Leight JL, Miksch CE, Brown TE, Anseth KS, Synthesis of Microgel Sensors for Spatial and Temporal Monitoring of Protease Activity, ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 4 (2018) 378–387. 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Juliar BA, Keating MT, Kong YP, Botvinick EL, Putnam AJ, Sprouting angiogenesis induces significant mechanical heterogeneities and ECM stiffening across length scales in fibrin hydrogels, Biomaterials. 162 (2018) 99–108. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Krajina BA, LeSavage BL, Roth JG, Zhu AW, Cai PC, Spakowitz AJ, Heilshorn SC, Microrheology reveals simultaneous cell-mediated matrix stiffening and fluidization that underlie breast cancer invasion, Sci. Adv 7 (2021) eabe1969. 10.1126/sciadv.abe1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]