Abstract

The Saudi Society of Clinical Pharmacy (SSCP) is a scientific and professional society in the field of clinical pharmacy that operates under the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties governance. The SSCP believes that there is a need to define and describe many aspects related to the clinical pharmacy profession in Saudi Arabia. Moreover, there is an increasing demand for promoting the concept of clinical pharmacy and developing a consensus regarding the scope of practice and clinical pharmacist's required postgraduate education and training in Saudi Arabia. This paper is intended to present several position statements by the SSCP that define the concept of clinical pharmacy, describe the required education and training, and highlight clinical pharmacists' scope of practice in Saudi Arabia. This paper calls for further investigations that examine the impact of clinical pharmacists on individual and population health levels.

Keyword: Clinical pharmacy, Definition, Education, Training, Saudi Arabia

1. Introduction

The clinical pharmacy profession went through several phases of advancements over the past few decades. It encountered numerous challenges starting from undergraduate education, postgraduate education and training, specialization, and recognition. Some of these challenges emerged due to poor perception of clinical pharmacy's fundamental concept, lack of efficient training centers and qualified clinical pharmacists, the uncertainty of the required qualifications, and descriptions of services integration models(Carter, 2016).

The concept of clinical pharmacy was first introduced in the mid-1960s in the United States (U.S.). Since its early stages of development, clinical pharmacy practice in the U.S. has continued to grow(Miller Russell, 1981). Decades after its establishment, the Board of Regents at the American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) developed a definition of clinical pharmacy in 2008. This definition came to shape the clinical pharmacy core competencies in the U.S(American College of Clinical Pharmacy, 2008). Numerous countries have attempted to follow the clinical pharmacy model in the U.S. Saudi Arabia (SA) was among the countries that attempted to adopt and implement the U.S. model of clinical pharmacy since the 1970s.

In SA, King Saud University, the first pharmacy school in the gulf region, was established in 1959. Since its establishment, the Bachelor of Pharmacy (BPharm) degree was the only offered degree for decades until the first Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) degree was introduced at King Abdulaziz University. Compared to the BPharm, the PharmD curriculum has more emphasis on pharmacy practice and includes an additional advanced experiential training year focused on providing direct patient care in various healthcare settings(Alhamoudi and Alnattah, 2018). Subsequently, pharmacy education in SA continued to emerge, and more pharmacy schools were established. Up until 2020, there were 30 pharmacy schools in SA (Badreldin et al., 2020).

In addition to the educational advancements, multiple efforts have contributed to the advancements in the clinical pharmacy postgraduate education and training, including establishing the Master of Clinical Pharmacy and the Postgraduate Pharmacy Practice and Specialized Residency programs. Up until 2020, there were more than 20 nationally accredited residency programs with more than 80 residents (Badreldin et al., 2020). With that in mind, the demand for clinical pharmacists and clinical pharmacy services is increasing in line with the expansion in the healthcare systems and the development of specialized centers (Albekairy et al., 2015). One of the national transformation goals of the 2030 Vision is to excel in health care provision. Therefore, it is crucial to align the concept and the direction of the clinical pharmacy profession with the intended objectives of the 2030 Vision. This could be achieved via establishing a solid base of the clinical pharmacy profession concept, including definitions and care provision models.

Major professional societies worldwide raised the issue of poor understanding of the clinical pharmacists' role and responsibilities by other stakeholders. The Saudi Society of Clinical Pharmacy (SSCP) is a professional and scientific society established in 2019 under the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties (SCFHS) governance. The SSCP aims to provide scientific guidance, recommendations, and insights for clinical pharmacists working in SA and represent the clinical pharmacy profession at the national and international levels(The Saudi Society of Clinical Pharmacy, 2020). The SSCP recognizes the variation in the pharmacy education, training, regulatory infrastructures, and practice-related issues in SA compared to North America and other regions. For example, in North America, there are no national classification systems for pharmacists based on their specialties. In addition, pharmacists are not ranked based on their education and training records. In contrast, in SA, the SCFHS recognizes pharmacists' specialties according to their education and training. Moreover, the SCFHS ranks pharmacists into different ranks based on the previously mentioned education and training backgrounds to either pharmacist, senior pharmacist, or pharmacy consultant. Thus, the SSCP believes that there is a need to define and describe many aspects related to the clinical pharmacy profession in SA.

This paper is intended to present several position statements by the SSCP that define the concept of clinical pharmacy, describe the required education and training, and highlight clinical pharmacists' scope of practice in SA. These positions could serve as a reference to all pharmacy leaders and other stakeholders such as the Pharmacy Scientific and Professional Boards, Saudi Health Council, Ministry of Education, and Ministry of Health. Furthermore, the SSCP plans to publish several other position statements that define clinical pharmacists' core competencies, roles and responsibilities, credentialing and privileges, and detailed practice settings.

2. Methods

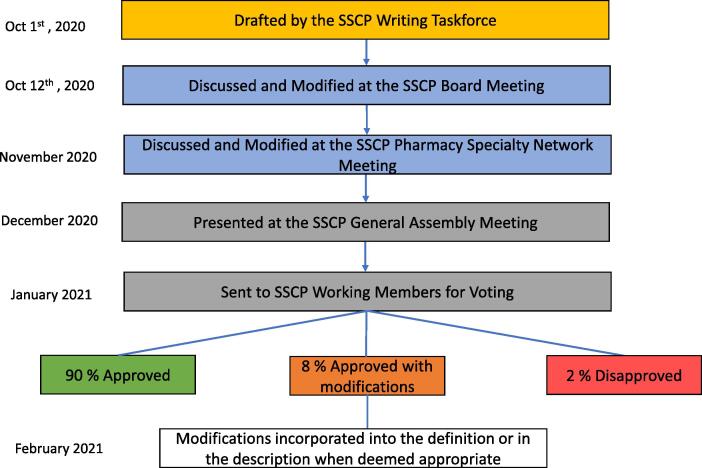

In September 2020, the SSCP established an expert writing taskforce of 15 clinical pharmacy specialists to draft the SSCP position statements. The taskforce consisted of six clinical pharmacy consultants, six clinical pharmacy academicians, and three pharmacy policymakers. The taskforce represented several healthcare sectors, practice settings, and geographical regions. Voting system methodology was used to obtain a consensus agreement and approve the proposed definition and position statements. A cutoff of 80% of SSCP active members was used to obtain the consensus agreement and final approval on the proposed definition.

The task force initially met to write the first draft of the position statements. Then, it was discussed and refined during the SSCP Board meeting on October 12th, 2020. A subsequent meeting was called in November 2020 with the SSCP Pharmacy Specialty Networks (PSN) board members, consisting of 25 members representing different clinical pharmacy specialties, including infectious disease, cardiology, internal medicine, ambulatory, and critical care. The SSCP PSN board members voted on the proposed definition of clinical pharmacy, and further refinement was made. Following this, the SSCP President presented the proposed definition during the SSCP General Assembly Meeting in December 2020. Then, the proposed definition was shared with all SSCP active members for public comments and voting through email. The members' suggestions were also incorporated in the definition. Finally, the final definition was presented in the SSCP Board meeting for final approval in February 2021. The detailed process and timeline of drafting and approving the clinical pharmacy definition are highlighted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The process of drafting and approving the clinical pharmacy definition.

Two main terminologies were utilized throughout the position statement. The first terminology was “Recommend,” which was used to refer to any position in accordance with the established best practices in North America and was inline with the current national regulations related to the pharmacy profession. The second terminology was “Advise,” which was used to refer to any position in accordance with the established best practices in North America and is currently not implemented nationally or not included in current national regulations and may provide future guidance.

3. Definition of clinical pharmacy

The disparities among many pharmacy sectors and other stakeholders on clinical pharmacy definition have been an area of debate universally. This has created several challenges at different levels, including licensing, classification, employment, and clinical pharmacists' job descriptions. The ACCP defined clinical pharmacy in an attempt to reflect on their profession's core elements as “a health science discipline in which pharmacists provide patient care that optimizes medication therapy and promotes health, wellness, and disease prevention (American College of Clinical Pharmacy, 2008).

The SSCP believes that the clinical pharmacy definition should embrace the required education and training, general role and responsibilities, and clinical pharmacists' scope of practice. More importantly, it should shape the essential competencies for clinical pharmacists in SA. It tacitly covers all medication-related aspects, including medication safety, efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and patient-centeredness, at both patient and population levels. For these reasons, the SSCP defines clinical pharmacy as: “The pharmacy profession's division in which the licensed pharmacist obtains the required postgraduate training or education or to optimize patient outcomes via providing cost-effective, evidence-based comprehensive medication management, promoting disease prevention, and assuring continuity of care at the individual and population levels.”

4. Required pharmacy education and training

4.1. Description

In SA, two pharmacy degrees are currently offered by pharmacy colleges to graduate pharmacists: a BPharm and a PharmD. In 2019, the SCFHS mandated to pass the Saudi Pharmacist Licensure Examination (SPLE) for all pharmacy degrees graduates to practice as a licensed pharmacists in SA (Saudi Commission for Health Specialties, 2019). The SPLE assesses the graduate's competencies that are needed for entry-level pharmacy practice. There are currently several colleges of pharmacy in SA that offer either BPharm, PharmD, or both. However, most colleges are either offering a PharmD degree currently or switching to PharmD as the terminal pharmacy degree. Pharmacy programs in SA must meet the National Qualification Framework. Moreover, pharmacy colleges need to attain national accreditation for their graduate and postgraduate academic programs by the National Centre for Academic Accreditation and Assessment which assures that major competencies are met. Some pharmacy colleges received international certifications by North American accreditation bodies such as the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) and the Canadian Council for Accreditation of Pharmacy Programs (CCAPP) (Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education, 2020, The Canadian Council for Accreditation of Pharmacy Programs, 2020).

Both the PharmD and the BPharm are considered pharmacy degrees that qualify their graduates to practice as pharmacists after passing the licensure exam offered by the SCFHS. None of them should be labeled as a clinical pharmacy degree, and all academic institutions are advised to refrain from calling their respective academic institution as clinical pharmacy colleges. Moreover, all institutions are advised to refrain from classifying PharmD or BPharm graduates as clinical pharmacists without proper postgraduate education or training. Nonetheless, graduates from both degrees are required to receive additional postgraduate education or training to practice as clinical pharmacists. Due to the heavy emphasis on clinical pharmacy in the PharmD curriculum, the SSCP advises to pursue PharmD as the terminal professional degree of choice, which better prepares the graduate for enrolment in postgraduate education or training programs to become a clinical pharmacist. It is important not to neglect that BPharm graduates could still be enrolled in postgraduate education or training programs to become clinical pharmacists. Also, it is important to highlight that many entry-level academic pharmacy degrees could be earned from international institutions. The Saudi authorities should recognize all pharmacy degrees prior to being able to set for the SPLE exam to be able to practice as a pharmacist in SA. As stated previously, the SPLE is designed to assess graduate's competencies that are needed for entry-level pharmacy practice.

There are several postgraduate training and education pathways that pharmacists could pursue to practice as a clinical pharmacist. These pathways include the master of clinical pharmacy and postgraduate pharmacy practice residency training programs. Nonetheless, both The ACCP and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) have advocated for the postgraduate pharmacy practice residency training to practice as a clinical pharmacist (Murphy et al., 2006). Saudi Arabia has adopted the pharmacy residency program model available in the U.S. However, unlike the U.S., where the pharmacy practice residency program lasts for 12 months, the SCFHS requires a minimum of two-year-long postgraduate pharmacy practice residency training. The first postgraduate pharmacy practice residency year focuses on acquiring the skills and knowledge in various hospital pharmacy operations such as outpatient pharmacy, inpatient pharmacy, drug information, and pharmacy administration. In contrast, the second year focuses on direct patient care clinical rotations. Postgraduate diploma certification is awarded after the resident has achieved a passing score on all rotations and the final Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) and written exams (Saudi Commission for Health Specialties; Scientific Council of Pharmacy, 2017). Following that, graduates could pursue specialized postgraduate residency training in order to practice as a specialized clinical pharmacist. The specialized postgraduate residency training duration is 12 months, similar to the U.S. specialized postgraduate residency programs (PGY-2). However, in SA, the resident has to achieve a passing grade in all rotations and the final SCFHS exams to obtain their specialization certification. All pharmacy practice residency sites in SA must be accredited by the SCFHS. Saudi Arabia is the first country outside the U.S. to have a residency program accredited by the ASHP (Al-Qadheeb et al., 2012).

An alternative pathway to practice as a clinical pharmacist in SA is via pursuing the master of clinical pharmacy degree, especially given the limited number of residency seats currently available in SA (Badreldin et al., 2020). Unlike SA and other countries, these programs are not available in the U.S. The curriculum varies drastically from one program to another (Alhamoudi and Alnattah, 2018). For the master's degree in clinical pharmacy to prepare graduates to become competent general clinical pharmacists, the SSCP advises that the curriculum shall incorporate a minimum of 6 months of clinical rotations that encompass direct patient care duties similar to pharmacy practice residents. Overall, the SSCP advises pursuing a structured residency training as the preferred route of training to practice as a general clinical pharmacist. The SSCP recommends pursuing a structured general and a specialized postgraduate residency as a minimum requirement to practice as a specialized clinical pharmacist.

An additional pathway for clinical pharmacists to advance their research skills is to pursue fellowship training or doctoral degrees. Most fellowship programs are research-focused, but very few might incorporate some clinical practice training that might qualify the graduates to practice as clinical pharmacists (Mueller et al., 2015). The SSCP advises seeking postgraduate education or training such Doctorate of Philosophy degree or fellowship to advance the clinical pharmacists' research skills.

4.2. Position statements

Position 1: The SSCP recommends that in order to practice as a pharmacist in SA, one should first obtain a pharmacy degree either from a national or international pharmacy school that is recognized by the national authorities and qualifies the graduate for licensure by the SCFHS.

Position 2: The SSCP recommends seeking a Doctor of Pharmacy degree that meets the national standards as the pharmacy degree of choice.

Position 3: The SSCP recommends that in order to practice as a general clinical pharmacist in SA, one should pursue a structured postgraduate pharmacy practice residency training or a postgraduate Master of Clinical Pharmacy either from a national or international institution that is recognized by the national authorities.

Position 4: The SSCP advises pursuing an accredited pharmacy practice residency training as the preferred postgraduate training.

Position 5: The SSCP advises for any master's in clinical pharmacy degree to be at least two years, including a minimum of six months of clinical training that encompasses direct patient care in addition to didactic coursework to prepare the graduates to practice as general clinical pharmacists.

Position 6: The SSCP recommends that in order to practice as a specialized clinical pharmacist in SA, one should pursue a structured, specialized postgraduate pharmacy practice residency training either from a national or international institution that is recognized by the national authorities.

Position 7: The SSCP advises all academic and healthcare institutions to avoid designating PharmD graduates as clinical pharmacists without completing further postgraduate pharmacy practice training or education.

Position 8: The SSCP advises all academic institutions to avoid naming schools of pharmacy as schools of clinical pharmacy.

Position 9: The SSCP advises to seek fellowship training or a doctor of philosophy degree in order to advance the clinical pharmacists' research skills.

5. Clinical pharmacy practice

5.1. Description

Clinical pharmacists are trained healthcare professionals who are capable of serving at the individual and population levels. As clinical pharmacy services become ingrained in healthcare systems, their practice settings are also becoming more structured. Generally, clinical pharmacists could serve at the individual level, mainly in primary, secondary, or tertiary healthcare settings(Bronkhorst et al., 2020). At the individual level, they could serve as pharmacotherapy experts in numerous specialties such as drug information, nutrition support, emergency medicine, critical care, internal medicine, infectious diseases, surgery, oncology, hematology, cardiology, nephrology, organ transplant, pediatrics, and medication safety (Bronkhorst et al., 2020). Also, they could serve in the ambulatory care settings to run individual clinics and provide comprehensive medication therapy management services (Anne Marie Bott et al., 2019). Under collaborative practice agreements, clinical pharmacists are authorized to prescribe and administer medications, perform physical assessments, and order laboratory or radiological investigations. The SSCP believes that there is a need to extend the coverage of clinical pharmacy practice to hospices, long-term care facilities, home health care, rural areas, and correctional facilities.

When it comes to the population level, clinical pharmacists are equipped with many skill-sets that qualify them to have vital roles in institutional, national, and international regulatory, academic, and healthcare authorities(Bhatt, 2014, Kuhn et al., 2019). For example, they could participate in developing evidence-based disease prevention and management guidelines and clinical pathways. They could also work as public health policymakers and alongside other policymakers to plan and execute transformative population health policies. Moreover, they could work alongside national and international agencies to meet healthcare concerns, such as environmental risk and emergency preparedness services. Clinical pharmacists may participate in population-based studies such as pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics and disseminate new knowledge to the community. However, such analyses usually require further research experience obtained through Ph.D. degrees or fellowship training. The detailed practice settings will be discussed in a separate paper. That being said, the SSCP believes that there is a tremendous need to quantify and assess the impact of clinical pharmacy services in SA on healthcare outcomes and society

5.2. Position statements

Position 1: The SSCP recommends that clinical pharmacists serve at the individual and population levels.

Position 2: The SSCP recommends that clinical pharmacists should be positioned to serve as integral members of the multidisciplinary team members.

Position 3: SSCP recommends that clinical pharmacists should be positioned to run individual clinics in their area of specialty and provide comprehensive medication therapy management under collaborative practice agreements.

Position 4: The SSCP advises to conduct research that investigates the direct and indirect impact of clinical pharmacists in SA.

6. Conclusion

This position statement aims to unify the definition and streamline the concept of clinical pharmacy in SA. This position statement also aims to highlight the required education and training and the scope of practice in SA. The position statement calls for further research on the impact of clinical pharmacy services on individual and population levels.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education, 2020. Programs with Certification Status By Country..

- Albekairy, A.M., Khalidi, N., Alkatheri, A.M., Althiab, K., Alharbi, S., Aldekhael, S., Qandil, A.M., Alknawy, B., 2015. Strategic initiatives to maintain pharmaceutical care and clinical pharmacists sufficiency in Saudi Arabia. SAGE Open Med. 3, 205031211559481. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312115594816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Alhamoudi A., Alnattah A. Pharmacy education in Saudi Arabia: The past, the present, and the future. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018;10(1):54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qadheeb N.S., Alissa D.A., Al-Jedai A., Ajlan A., Al-Jazairi A.S. The First International Residency Program Accredited by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Am. J. Pharm. Ed. 2012;76(10):190. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7610190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Clinical Pharmacy The Definition of Clinical Pharmacy. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28 doi: 10.1592/phco.28.6.816. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anne Marie Bott, C., John Collins, C., Stephanie Daniels-Costa, C., Kristen Maves, C., Amanda Runkle, C., Amy Simon, C., Kyle Sheffer, C., Randy Steers, C., Jacklyn Finocchio, L., Luke Stringham, L., Gina Sutedja, L., 2019. Clinical Pharmacists Improve Patient Outcomes and Expand Access to Care. Federal Practitioner 36, 471–475. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Badreldin H.A., Alosaimy S., Al-jedai A. Clinical pharmacy practice in Saudi Arabia: Historical evolution and future perspective. J. American College Clin. Pharm. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jac5.1239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt P. Being a clinical pharmacist: Expectations and outcomes. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2014;46(1):1. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.124882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronkhorst E., Gous A.G.S., Schellack N. Practice Guidelines for Clinical Pharmacists in Middle to Low Income Countries. Front. Pharmacol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter B.L. Evolution of Clinical Pharmacy in the USA and Future Directions for Patient Care. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(3):169–177. doi: 10.1007/s40266-016-0349-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn C., Groves B.K., Kaczor C., Sebastian S., Ramtekkar U., Nowack J., Toth C., Valenti O., Gowda C. Pharmacist Involvement in Population Health Management for a Pediatric Managed Medicaid Accountable Care Organization. Children. 2019;6(7):82. doi: 10.3390/children6070082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Russell, R., 1981. History of Clinical Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 21. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb05699.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mueller E.W., Bishop J.R., Kanaan A.O., Kiser T.H., Phan H., Yang K.Y. Research Fellowship Programs as a Pathway for Training Independent Clinical Pharmacy Scientists. Pharmacotherapy: J. Human Pharmacol. Drug Therapy. 2015;35(3):e13–e19. doi: 10.1002/phar.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy J.E., Nappi J.M., Bosso J.A., Saseen J.J., Hemstreet B.A., Halloran M.A., Spinler S.A., Welty T.E., Dobesh P.P., Chan L.-N., Garvin C.G., Grunwald P.E., Kamper C.A., Sanoski C.A., Witkowski P.L. American College of Clinical Pharmacy’s Vision of the Future: Postgraduate Pharmacy Residency Training as a Prerequisite for Direct Patient Care Practice. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(5):722–733. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.5.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Commission for Health Specialties, 2019. Saudi Pharmacist Licensure Examination (SPLE) Applicant Guide.

- Saudi Commission for Health Specialties; Scientific Council of Pharmacy, 2017. Candidate Information for Clinical Pharmacy Residency Programs 2017, 2nd ed.

- The Canadian Council for Accreditation of Pharmacy Programs, 2020. International Pharmacy Degree Programs Accredited by CCAPP.

- The Saudi Society of Clinical Pharmacy, 2020. The Saudi Society of Clinical Pharmacy Home Page [WWW Document]. URL https://sscp.org.sa/ (accessed 7.29.21).