Abstract

Dysregulation of post‐translational modifications (PTMs) like phosphorylation is often involved in disease. NMR may elucidate exact loci and time courses of PTMs at atomic resolution and near‐physiological conditions but requires signal assignment to individual atoms. Conventional NMR methods for this base on tedious global signal assignment that may often fail, as for large intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). We present a sensitive, robust alternative to rapidly obtain only the local assignment near affected signals, based on FOcused SpectroscopY (FOSY) experiments using selective polarisation transfer (SPT). We prove its efficiency by identifying two phosphorylation sites of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β) in human Tau40, an IDP of 441 residues, where the extreme spectral dispersion in FOSY revealed unprimed phosphorylation also of Ser409. FOSY may broadly benefit NMR studies of PTMs and other hotspots in IDPs, including sites involved in molecular interactions.

Keywords: NMR spectroscopy, S4PT, tau protein, selective polarisation transfer

A new suite of 2D FOSY experiments focuses on one coupled nuclear spin system at a time, that is, a PTM site or a structural hotspot in general, with 3–5 known frequencies. With higher sensitivity and versatility than achievable by traditional experiments, FOSY solves the spectral dispersion problem and obtains only the relevant local NMR signal assignment in a few hours, as demonstrated for two phosphorylation sites in the 441‐residue IDP Tau.

Post‐translational modifications (PTMs) constitute an additional level of complexity in modulating protein function, where phosphorylation is the best studied signalling switch, being abundant and essential in the regulation of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). [1] Phosphorylation is conventionally detected and quantified by mass spectrometry, then validated by mutagenesis or antibody binding assays. This procedure is expensive, time‐consuming, and often fraught with problems especially for highly charged phosphopeptides, repetitive sequences, and proximal modification sites, all of which are hallmarks of IDPs. [2] To address these difficulties, time‐resolved heteronuclear NMR methods have been developed that also allow to derive the reaction kinetics, [3] but require prior NMR signal assignment for the entire protein. The latter is obtained from a suite of multi‐dimensional experiments [4] with often limited sensitivity, and after several days of measurement and sophisticated spectra analysis to resolve assignment ambiguities that may still prove inextricable in highly crowded spectral regions. [5] Thus, a fast, simple, and robust NMR approach for tracking PTMs like phosphorylation would be of great benefit for elucidating their role in proteins with atomic resolution. [6] To address this need, we here introduce FOcused SpectroscopY (FOSY) for local (instead of global) de novo NMR signal assignment at structural hotspots, such as PTM sites, based on a minimal set of frequency‐selective experiments that focus on their sequential vicinity and combine the ultrahigh signal dispersion of up to six‐ or seven‐dimensional (6D, 7D) spectra with the sensitivity, speed, and simplicity of 2D spectra.

Central to our method of focussing onto the few residues affected by PTMs and solving the spectral dispersion problem in only two dimensions is to use frequency selection to single out one coupled nuclear spin system (i.e. a residue) at a time. [7] FOSY uses several distinct frequency Selective Polarisation Transfer (SPT) schemes[ 7b , 8 ] (see details in the Supplementary Information), which offer an efficiency and versatility higher than achievable by conventional broadband experiments.[ 8c , 9 ] While optimising sensitivity, multiple selection of known frequencies along a chosen spin system minimises spectral complexity and makes their lengthy sampling in further indirect dimensions redundant. SPT is a known technique with several clear advantages, but its use has so far been limited to isolated two‐spin systems[ 9c , 9d , 10 ] like 1H‐15N amide groups, allowing a reduction by just two spectral dimensions. Thus, a 6D could be cut down to a 4D experiment that would still take impractically long to measure for each selected residue at a time. Here we introduce frequency Selective and Spin‐State Selective Polarisation Transfer (S4PT) as a generalized SPT approach for coupled multi‐spin systems, as in isotopically labelled amino acids, which allows to eliminate several pertaining spectral dimensions as well as detrimental evolution of competing passive spin couplings. The novel 2D FOSY spectra (Figure 1) yield a signal dispersion as in a 6D HNCOCANH [4a] and 7D HNCOCACBNH, yet with far superior sensitivity and ease of analysis.

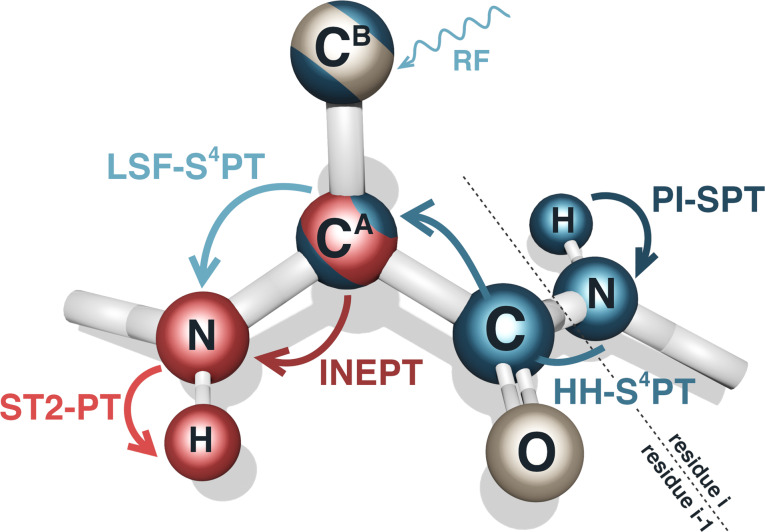

Figure 1.

Polarisation transfer pathway in the 2D FOSY hnco(CA)NH, hncoCA(N)H, and hncocacbNH experiments (see Supplementary Figure S1). Colour code for polarisation transfer steps shown by arrows: blue—frequency selective (PI‐SPT, [8a] HH‐S4PT,[ 7b , 8c ] LSF‐S4PT [8d] ), red—broadband (INEPT, ST2‐PT [11] ). Colour code for atoms according to their frequency probing: blue—known (e.g., from a 3D HNCO) and selected by SPT; red—unknown and evolved in a spectral dimension; striped red/blue—optionally selected or evolved; grey—ignored. Transfer starts with amide proton 1Hi magnetization of residue i and ends with detection on 1Hi−1 of the preceding residue i−1. As key element of FOSY experiments, we introduce frequency selective and spin‐state selective polarization transfer (S4PT) steps (detailed in the Supplementary Information) that can be specifically combined to adjust to local spin system properties like scalar coupling network, chemical shift ranges, and relaxation. [9b] The experiments start with selective polarisation transfer by population inversion (PI‐SPT) of the TROSY [11b] component of 1Hi magnetization to create antiphase polarisation with a maximal efficiency surpassing all methods for broadband polarisation transfer. [9b] A subsequent HH‐S4PT step implements separate selective heteronuclear Hartmann‐Hahn transfer for both 15N TROSY and anti‐TROSY coherences without their mixing, as required by the TROSY principle, [11b] to achieve relaxation optimised fast and direct conversion. A final LSF‐S4PT (instead of broadband INEPT) step, used only in the FOSY hncocacbNH experiment, employs longitudinal single field polarization transfer [8d] for direct conversion and concomitant selective 13CB,i−1 decoupling to probe for its amino acid type specific frequency. All FOSY experiments ensure maximal preservation of both water and aliphatic proton polarization to enable fast selective polarization recovery [4a] for the amide protons. FOSY experiments are designed primarily for IDPs having sufficiently slow T2 relaxation and amide proton exchange with water to sustain the long magnetization transfer pathways with high efficiency.

As a showcase application for the proposed FOSY approach to monitor PTMs in IDPs, we identify phosphorylated residues in vitro by proline‐dependent glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β) [12] in the 441‐residue long human hTau40 protein, which comprises 80 serines and threonines as potential phosphorylation sites. Abnormal hTau40 hyper‐phosphorylation is directly linked to its dysregulation and, possibly, aggregation that characterises neurodegenerative tauopathies, such as Alzheimer's disease. [13] As a first step of our strategy (outlined in Figure 2 a), spectral changes from GSK3β‐mediated phosphorylation of hTau40 (150 μM, uniformly labelled with 2H,13C,15N) in the most sensitive and best dispersed 3D HNCO spectrum revealed several shifted or newly appearing signals for p‐hTau40 (peaks a–g in Figure S4). Due to the abundance of proline and glycine residues in IDPs (Figure S8 in Supporting Information), we assembled a list of hTau40 sequence stretches conforming with the general motif (P/G)‐Xn‐p(S/T)‐Xn‐(P/G) where X ≠ Pro, Gly. The list can be further refined based on reported phosphorylation sites or known kinase consensus sequence motifs (Table S1). This preparatory step concludes with the acquisition of two complementary proline selective 2D experiments [11a] to identify the residues following (PX‐) or preceding (‐XP) prolines (Figure S5).

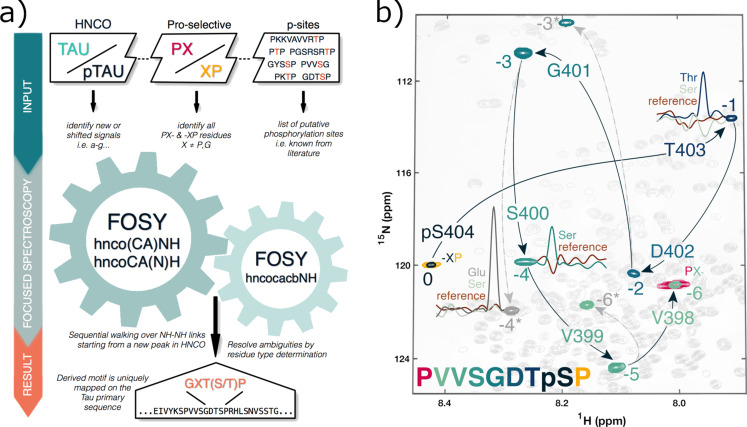

Figure 2.

FOSY NMR assignment strategy (a) and application (b) to assign a phosphorylation site in hTau40. Signal 0 newly appears after hTau40 phosphorylation by GSK3β and corresponds to a residue preceding a proline, as revealed by a proline‐selective experiment. The sequential walk (black arrows) along NH‐NH correlations is traced out by successive iterations of 2D FOSY‐hnco(CA)NH experiments. Thus connected signals are numbered by the pertaining FOSY step number, and are gradually coloured as in the associated peptide sequence (below, left). For signal −2, the 2D FOSY‐hnco(CA)NH spectrum also opens an alternative branch of signals indicated by asterisks and connected by dashed grey arrows. To resolve such ambiguities, preceding residue types were tested using the 2D FOSY‐hncocacbNH experiment, which only produces a signal (inserted 1D 1H cross‐sections) if the correct residue specific 13CB,−1 frequency is preset. The derived PXXSGXTp(S/T)P motif unambiguously maps to PVVSGDTS404P and, thus, assigns the phosphorylation site signal 0 to pS404.

To start the FOSY assignment process, we focus on signal 0 (Figure 2 b) that appears in the 3D HNCO spectrum after hTau40 phosphorylation (peak “a” in Figure S4) and likely corresponds to a phosphorylated serine (pS) or threonine (pT). The proline selective spectra show that this new signal derives from a pS or pT preceding a proline (i.e., a p(S/T)P motif, Table S1). A pair of 2D FOSY hnco(CA)NH and hncoCA(N)H experiments (Figure 1) is then recorded for signal 0 using its associated exact 1HN,0, 15NH,0, 13CO,−1 frequencies from the 3D HNCO spectrum. This yields the 15NH,−1, 1HN,−1, and 13CA,−1 frequencies of the preceding residue X and connects signal 0 with signal −1 (Figure 2 b) to compose a ‐Xp(S/T)P motif. We continue the FOSY walk to signal −2 using the 15NH,−1, 1HN,−1, and 13CO,−2 frequencies for signal −1 (the latter again derived from the 3D HNCO). This iteration is repeated until reaching a proline or glycine signal, the latter identified by the negative intensity (from constant‐time evolution) and characteristic chemical shift of its 13CA signal. For starting signal 0 we, thus, identify a GXXp(S/T)P motif that matches with either GYSS199P or GDTS404P stretch in the hTau40 sequence.

To resolve this assignment ambiguity, or in case of several peaks observed in the 2D hnco(CA)NH and hncoCA(N)H spectra due to an overlap of the initially selected frequencies (e.g., the FOSY walk from signal −2 connects with both signals −3 and −3* in Figure 2 b), we furthermore record a 2D FOSY hncocacbNH experiment (Figure 1) with five fixed frequencies (1HN,0, 15NH,0, 13CO,−1, 13CA,−1, 13CB,−1) to determine the preceding residue type. The unknown 13CB,−1 frequency to be determined is chosen from predicted residue‐type‐specific chemical shifts for random coil. [14] By producing a signal only if the correct 13CB,−1 frequency is used for selective decoupling,[ 8b , 15 ] the 2D FOSY hncocacbNH spectrum for signal 0 reveals that the associated p(S/T) residue is preceded by a threonine. Thus, GDTS404P is the correct assignment and signal 0 corresponds to pS404.

Similar 2D FOSY hncocacbNH experiments for the alternative Gly signals −3 and −3* show that only the former is preceded by a Ser (signal −4), as in the identified GDTS404P stretch, while signal −3* is preceded by a Glu (signal −4*) and, therefore, starts a false branch. Further FOSY walking leads to signals −5 and −6 that the proline‐selective spectrum shows to succeed a proline (in contrast to signal −6* on another false branch). This results in a PXXSGXTp(S/T)P motif that uniquely maps onto the hTau40 PVVSGDTS404P stretch and, thus, corroborates signal 0 assignment to pS404. Overall, the minimal set of 2D FOSY spectra (Figure S5) for unambiguous identification of the pS404 site comprises three pairs of complementary hnco(CA)NH and hncoCA(N)H for the sequential walk plus three hncocacbNH to identify the preceding residue type, altogether recorded within less than two hours. The short duration of a 2D FOSY experiment allows a very flexible allocation of the measurement time in response to the needs for a specific spin‐system, for example, by using the Targeted Acquisition approach. [16] Thus, the sensitivity of residues with a more pronounced signal attenuation from T2 relaxation, or from conformational/chemical exchange may be significantly increased by more signal accumulation, for example, by adding several short 2D FOSY experiments. As these highly selective 2D spectra contain only a single or very few peaks, their real‐time analysis is most straightforward.

Analogous identification of the second phosphorylation site pS409 by a similar minimal set of 2D FOSY spectra to compile the unique PRHLpS409 motif is illustrated in the Supporting Information (Figure S6).

Together, pS404 and pS409 account for all newly appearing and shifted signals (of nearby residues) in the HNCO spectrum of p‐hTau40, proving them to be the only two phosphorylation sites for GSK3β under our experimental conditions. Of note, while proline dependent S404 phosphorylation was known from prior studies,[ 12 , 17 ] only the extreme spectral simplification and dispersion afforded by our new FOSY approach allowed to also confirm S409 phosphorylation by GSK3β. Although, the latter was detected previously and suggested to occur in the pre‐neurofibrillar tangle state of hTau,[ 13d , 18 ] S409 phosphorylation was so far believed to require priming phosphorylation by other protein kinases. [19]

In summary, we have demonstrated the de novo identification of phosphorylation sites in IDPs by the fast and robust new FOSY NMR approach. The proposed strategy requires no lengthy prior signal assignment nor knowledge of the target sites for PTM. Key to the new approach is its local focus on the relevant modification sites to identify short motifs for unambiguous sequence mapping, which is much faster and broader applicable than the conventional approach of global NMR signal assignment limited by the size and spectral complexity of the protein. Analysis is fast and most straightforward due to the extreme simplicity of 2D FOSY spectra that still reflect the enormous signal dispersion of their conventional complex 6D and 7D counterparts. The great benefits and versatility of such frequency selective NMR approaches, here demonstrated by a proof‐of‐concept study on IDP phosphorylation, are generalizable and should enable broad new studies on a plethora of biomolecular hotspots hitherto inaccessible by NMR. [20]

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Ilya S. Kuprov for helpful discussions. The work was sponsored by Swedish Research Council to V.Y.O. (grant 2019‐03561) and Russian Science Foundation to D.M.L. and E.V.B. (grant 19‐74‐30014, in part of NMR pulse sequence design). B.M.B. gratefully acknowledges funding from the Knut och Alice Wallenberg Foundation through the Wallenberg Centre for Molecular and Translational Medicine, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. The Swedish NMR Centre of the University of Gothenburg is acknowledged for spectrometer time. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

D. M. Lesovoy, P. S. Georgoulia, T. Diercks, I. Matečko-Burmann, B. M. Burmann, E. V. Bocharov, W. Bermel, V. Y. Orekhov, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 23540.

A previous version of this manuscript has been deposited on a preprint server (https://arxiv.org/abs/2101.00605).

References

- 1.

- 1a. Walsh C. T., Garneau-Tsodikova S., G. J. Gatto, Jr. , Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 7342–7372; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2005, 117, 7508–7539; [Google Scholar]

- 1b. Bah A., Forman-Kay J. D., J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 6696–6705; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1c. Boeynaems S., Alberti S., Fawzi N. L., Mittag T., Polymenidou M., Rousseau F., Schymkowitz J., Shorter J., Wolozin B., Van Den Bosch L., Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 420–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Mitra G., Proteomics 2020, 21, 2000011; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Mair W., Muntel J., Tepper K., Tang S., Biernat J., Seeley W. W., Kosik K. S., Mandelkow E., Steen H., Steen J. A., Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 3704–3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a. Landrieu I., Lacosse L., Leroy A., Wieruszeski J.-M., Trivelli X., Sillen A., Sibille N., Schwalbe H., Saxena K., Langer T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 3575–3583; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b. Theillet F. X., Rose H. M., Liokatis S., Binolfi A., Thongwichian R., Stuiver M., Selenko P., Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 1416–1432; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3c. Mayzel M., Rosenlow J., Isaksson L., Orekhov V. Y., J. Biomol. NMR 2014, 58, 129–139; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3d. Rosenlöw J., Isaksson L., Mayzel M., Lengqvist J., Orekhov V. Y., PLoS One 2014, 9, e96199; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3e. Alik A., Bouguechtouli C., Julien M., Bermel W., Ghouil R., Zinn-Justin S., Theillet F. X., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 10411–10415; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 10497–10501. [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Lescop E., Schanda P., Brutscher B., J. Magn. Reson. 2007, 187, 163–169; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Isaksson L., Mayzel M., Saline M., Pedersen A., Rosenlöw J., Brutscher B., Karlsson B. G., Orekhov V. Y., PLoS One 2013, 8, e62947; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Motáčková V., Nováček J., Zawadzka-Kazimierczuk A., Kazimierczuk K., Žídek L., Šanderová H., Krásný L., Koźmiński W., Sklenář V., J. Biomol. NMR 2010, 48, 169–177; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4d. Bermel W., Bertini I., Felli I. C., Gonnelli L., Koźmiński W., Piai A., Pierattelli R., Stanek J., J. Biomol. NMR 2012, 53, 293–301; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4e. Narayanan R. L., Dürr U. H., Bibow S., Biernat J., Mandelkow E., Zweckstetter M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11906–11907; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4f. Pustovalova Y., Mayzel M., Orekhov V. Y., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 14043–14045; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 14239–14241. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Theillet F. X., Smet-Nocca C., Liokatis S., Thongwichian R., Kosten J., Yoon M. K., Kriwacki R. W., Landrieu I., Lippens G., Selenko P., J. Biomol. NMR 2012, 54, 217–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a. Bugge K., Brakti I., Fernandes C. B., Dreier J. E., Lundsgaard J. E., Olsen J. G., Skriver K., Kragelund B. B., Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 110; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6b. Berlow R. B., Dyson H. J., Wright P. E., FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 2433–2440; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6c. Darling A. L., Uversky V. N., Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.

- 7a. Freeman R., Chem. Rev. 1991, 91, 1397–1412; [Google Scholar]

- 7b. Kupce E., Freeman R., J. Magn. Reson. Ser. A 1993, 101, 225–228. [Google Scholar]

- 8.

- 8a. Pachler K., Wessels P., J. Magn. Reson. 1977, 28, 53–61; [Google Scholar]

- 8b. Huth J., Bodenhausen G., J. Magn. Reson. Ser. A 1995, 114, 129–131; [Google Scholar]

- 8c. Pelupessy P., Chiarparin E., Concepts Magn. Reson. 2000, 12, 103–124; [Google Scholar]

- 8d. Rey Castellanos E. R., Frueh D. P., Wist J., J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 129, 014504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.

- 9a. Chiarparin E., Pelupessy P., Bodenhausen G., Mol. Phys. 1998, 95, 759–767; [Google Scholar]

- 9b. Khaneja N., Luy B., Glaser S. J., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 13162–13166; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9c. Korzhnev D. M., Orekhov V. Y., Kay L. E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 713–721; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9d. Hansen A. L., Nikolova E. N., Casiano-Negroni A., Al-Hashimi H. M., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3818–3819; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9e. Novakovic M., Kupče Ē., Oxenfarth A., Battistel M. D., Freedberg D. I., Schwalbe H., Frydman L., Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Walinda E., Morimoto D., Shirakawa M., Sugase K., J. Biomol. NMR 2017, 68, 41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.

- 11a. Solyom Z., Schwarten M., Geist L., Konrat R., Willbold D., Brutscher B., J. Biomol. NMR 2013, 55, 311–321; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Pervushin K. V., Wider G., Wüthrich K., J. Biomol. NMR 1998, 12, 345–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Godemann R., Biernat J., Mandelkow E., Mandelkow E.-M., FEBS Lett. 1999, 454, 157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.

- 13a. Stoothoff W. H., Johnson G. V., Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2005, 1739, 280–297; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13b. Hanger D. P., Anderton B. H., Noble W., Trends Mol. Med. 2009, 15, 112–119; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13c. Guo T., Noble W., Hanger D. P., Acta Neuropathol. 2017, 133, 665–704; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13d. Rankin C. A., Sun Q., Gamblin T. C., Mol. Neurodegener. 2007, 2, 12; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13e. Hernández F., Gómez de Barreda E., Fuster-Matanzo A., Lucas J. J., Avila J., Exp. Neurol. 2010, 223, 322–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.

- 14a. Tamiola K., Acar B., Mulder F. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 18000–18003; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14b. Hendus-Altenburger R., Fernandes C. B., Bugge K., Kunze M. B. A., Boomsma W., Kragelund B. B., J. Biomol. NMR 2019, 73, 713–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ritter C., Lührs T., Kwiatkowski W., Riek R., J. Biomol. NMR 2004, 28, 289–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jaravine V., Orekhov V. Y., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 13421–13426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leroy A., Landrieu I., Huvent I., Legrand D., Codeville B., Wieruszeski J. M., Lippens G., J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 33435–33444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barthélemy N. R., Mallipeddi N., Moiseyev P., Sato C., Bateman R. J., Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lippens G., Amniai L., Wieruszeski J. M., Sillen A., Leroy A., Landrieu I., Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2012, 40, 698–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The presented pulse sequences for Bruker Avance spectrometers are available at https://github.com/lesovoydm/FOSY-NMR.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information