Abstract

Background: Genetic testing at crime scenes is an instrumental molecular technique to identify or eliminate suspects, as well as to overturn wrongful convictions. Yet, genotyping alone cannot reveal the age of a sample, which could help advance the utility of crime scene samples for suspect identification. The distribution of cytosine methylation within a DNA sample can be leveraged to determine the epigenetic age of someone's blood.

Methodology: We sought to demonstrate the ability of DNA methylation markers to accurately discern the age of blood spots from an actual crime scene, a “mock” crime scene, and also from a tube of blood stored in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid for >20 years. This was achieved by quantifying methylation within known age-associated genetic loci across each DNA sample. We observed a strong linear coefficient (0.91) and high overall correlation (R2 = 0.963) between the known age of a sample and the predicted age.

Conclusion: We show that novel methods for targeted methylation and low-input whole-genome bisulfite sequencing can enable a novel and improved forensic profile of a crime scene that discerns not only who was present at the crime, but also their age. Finally, we use this model to discern the age and provenance of a blood sample that was used in a criminal investigation.

Keywords: age prediction, crime scene, bisulfite sequencing, low input sequencing, blood, epigenetics

Introduction

DNA methylation (DNAm) is a fundamental epigenetic mark on human cells that enables lineage specification for specific cell types that are tightly regulated during development.1,2 Previous studies have shown that DNAm at specific genomic loci is highly correlated with the age of cells, enabling the prediction of an “epigenetic age” for a sample of DNA.3–6 Other study has shown that the proportion of clones represented by DNAm can also reveal the progression of cancer, examine epigenetic clonality, or discern the types of cells that are present.7–9

Although these methods have proven valuable in the determination of legal responsibility in civil cases,10 they have not yet been implemented in a criminal investigation. In the case of the State of Wisconsin v. Steven Avery, blood was collected in 1996 that was later implicated in the 2005 case of Teresa Halbach's murder. In the 2005 case, new blood was discovered at the crime scene that belonged to Steven Avery. However, its provenance was unclear, and it was alleged that the blood may have been collected in 1996 instead of 2005. Given the ability of DNAm markers to discern the age of a sample, we employed new methods for DNA capture, bisulfite sequencing, and computational methods to predict the age of a sample taken from controls, the Halbach case, and remnant DNA from evidence in the same case. We observed a high level of concordance between the known and predicted age of samples and concluded that these data show the ability to eliminate contention over the provenance and age of a sample during a criminal case.

Materials and Methods

Sample preparation and purification

DNA was purified from collected blood samples using a variety of sample-type-specific extraction protocols in a negative pressure hood and clean room. Samples were extracted with the Promega Maxwell Research Sample Concentrator (RSC), which uses automated and sample-isolated columns for enriching DNA with their blood purification kit (kit #AS1010). Three negative controls were also run for all sets of samples and found no detectible DNA.

DNA extraction from samples

Samples were cut out from up to 0.5 cm2 of stained material and then cut it into smaller pieces. Pieces were then transferred to a 2-mL microcentrifuge tube, and 300 μL of tris buffer and 20 μL proteinase K were added and pulse-vortexed for 10 s. Tubes were placed in a thermomixer and incubated at 56°C with shaking at 900 rpm for 1 h. One hundred fifty microliters ethanol (96–100%) was then added to the tubes, the lids were closed, and tubes were mixed thoroughly by pulse vortexing for 15 s. Samples were then eluted and examined on a Bioanalyzer 2100 Tapestation.

Panel for DNAge™

Bisulfite conversion was performed using the EZ DNA Methylation-Lightning™ Kit (Cat. No. D5030) according to the standard protocol. Samples were then enriched for sequencing of >500 age-associated gene loci on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument using 100-bp paired-end sequencing. Blood sample DNAm values were obtained from the sequence data and used to assess the DNA age according to Zymo Research's myDNAge™ predictor.

Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing

Sample libraries were prepared from low-input (nanogram quantities of) genomic DNA, which was bisulfite treated using Zymo Research (ZR) EZ DNA Methylation—Lightning™ kit (Cat. No.: D5030). The bisulfite-converted DNA was subjected to amplification with a primer that contained part of the NGS library adapter sequence in addition to four random nucleotides, followed by two additional steps of amplification to add on the remaining adapter sequence and barcode the fragments, respectively. All PCR products were purified using the DNA Clean & Concentrator-5™ (Cat. No.: D4003). Library fragment size and concentration were checked using the Agilent 2200 TapeStation instrument. Sequence data were generated on an Illumina HiSeq X platform at New York Genome Center (NYGC) and analyzed with known epigenetic markers11 as well as those taken from the NIH's Epigenome Roadmap data.

WGBS data analysis

Bisulfite sequence data were aligned to the in silico converted hg19 genome and methylation percentage per CpG was calculated with default parameters using Bismark.12 Read groups were added to BAM files calling using Picard AddOrReplaceReadGroups. Bis-SNP was used for variant calling against the hg19 genome and using dbSNP build 135 to annotate known variants, with materials retrieved from http://people.csail.mit.edu/dnaase/bissnp2011

Clonality analysis

We used Bismark12 to align bisulfite reads to the human reference genome using build GRCh38. We then used methylKit13 and methClone4 to estimate the clonality and quality metrics for the whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) and captured data, applying a minimum threshold of 10 × coverage across the detected CpG sites and minimum base quality of 30 (99.9% accuracy) and a mapping quality of Q30. IRB Protocol #10001 was authorized by Kathleen T. Zellner & Associates, including notarized consents from each individual.

Results

DNAm age predictor validation

We first established the reliability of the DNAm age prediction from a “mock crime scene” that was the same make and model (1995 Toyota RAV4) as the one from the Avery case. We consented 49 volunteers of known age (22–80) to have blood drawn and then deposited on eight difference surface types in the car (dashboard, passenger's seat, CD case, rear-door entrance panel, console floor, driver's seat, left-passenger's seat, and ignition casing). Using a clean room and a Promega Maxwell automated DNA extraction protocol, we obtained at least 50 ng of DNA from 9 of the samples and at least 10 ng from 20 samples, with others yielding <0.01 ng/μL. We then used a customized DNA capture panel for age-specific markers from ZR as well as a low-input WGBS protocol for picogram-level input DNA. This enabled the capture and measurement of 513 epigenetic age markers for use in the study.

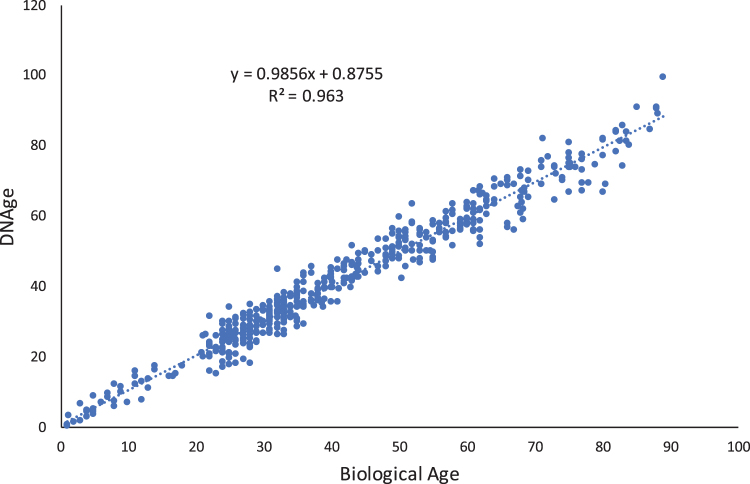

For the nine samples with high enough yield, we used the Zymo DNAge capture panel to enrich for the age-specific markers across the genome. This showed an ability to find the age of a sample with a strong linear coefficient (0.91) and high overall correlation (R2 = 0.963) between the known age of a sample and the predicted age, across a range of eight different surface types (Fig. 1). Technical repeats of the assay for replicates of the same sample yielded a technical error (delta Age or ΔAge) of ±1.2 years, and samples across a set of 195 other samples tested from other blood collections have shown that 91.77% of samples showed ΔAge ±5 years (Table 1). Across all samples tested for this collection, or previous collections, predicted age was not observed to diverge from the actual age of a donor by >10 years.

Fig. 1.

Regression analysis of DNAge predicted from epigenetic markers versus biological age per sample.

Table 1.

Summary of Testing Range and Accuracy with the DNAge Methyl-Capture Panel

| Age difference (ΔAge) | No. of samples | No. of tested samples | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| >10 Years | 0 | 195 | 0.00 |

| >5 Years | 12 | 195 | 6.15 |

| 0–5 Years | 177 | 195 | 91.77 |

| <−5 Years | 6 | 195 | 3.08 |

| <−10 Years | 0 | 195 | 0.00 |

Case sample estimation

For the 1996 sample preserved in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), we performed the same assay extraction and collection methods. The age of Steven Avery in 1996 was 34.5, and our DNAm estimate was 37.9. Given the 21 years spent in storage, this represents the first evidence of a reliable method for gauging the epigenetic age of a long-term storage sample in a forensic capacity. Also, using blood drawn from Steven Avery in 2016 that was placed in and on the mock RAV4, we estimated his age to be 52.4, whereas his age at the time was 54.9. These combined results indicate a strong ability to guess the age of a sample with an empirical error range of 2.5–3.5 years.

For the samples taken from the crime scene (A6, A8, and A9), we used the same protocol and technician to extract DNA. We identified 4.2, 6.6, and 48.4 ng of DNA from the samples and used the last sample, given that it had the highest yield, for our testing. After testing low-input samples for capture, we performed WGBS and characterized the higher-yield sample with the capture panel. We found that the predicted age for sample A9 (the passenger-seat blood spot) was 52.8 years. Given that Steven Avery was 43.4 at the time of the murder and 34.5 at the time of blood collection in 1996, this indicates that the blood from the crime scene identified as Steven Avery's blood was more likely from 2005.

We further examined our confidence in this result relative to all other tested samples. As described earlier, combined technical and biological variation of the DNAm measurement never exceeded 10 years (Table 1), even with degraded DNA from similar environments. Given our measurement in the laboratory across all samples tested with this method to date, our confidence of this one sample being beyond the expected range, with this specific method, is 1/226 (99.6%). Also, since the measurement accuracy of DNAm biochemical methods and algorithms follow a Gaussian distribution, and that the error across all samples tested to-date has been on average 3.4 years, a three-sigma standard deviation would give us 99.7% confidence that this sample is within the range of the older potential age. Since the 1996 sample is from when Steven Avery was 34.5, whereas we see a predicted age of 52.8, it would be almost impossible for the blood to be from the EDTA tube (spanning 18.3 years and beyond five sigma, or 99.99994%). Thus, the most probable interpretation of these data is that that the sample from the scene of the Halbach case is blood from Steven Avery in 2005, not in 1996.

Discussion

The findings within this study provide evidence toward the reliability of predicting the biological age of an individual's DNA using methylation estimates within epigenetic loci. This can be critically important for samples acquired from a crime scene, where the estimated age of the source of the DNA might be important evidence within a criminal investigation and legal proceedings. We show the ability of this method to estimate age with an empirical error range of 2.5–3.5 years, and never exceeding a 10-year difference in either direction. We found this to be true across several sample types, including highly degraded, low DNA input samples from a crime scene and higher quality mock controls, as well as several modalities of epigenetic interrogation, including the targeted DNAge™ panel and WGBS. We also demonstrated the accuracy of this method on a sample of blood that was 21 years old, providing evidence that older samples kept in long-term storage can be revisited and analyzed reliably. In the context of the Steven Avery case, the predicted age of the blood sample of interest, which was genotyped as belonging to Steven Avery, was found to be 52.8. Given that Mr. Avery was 43.4 years of age at the time of the murder, we demonstrated with >99.9% certainty that the provenance of the sample was the crime scene (Toyota RAV4) in 2005, rather than the EDTA-preserved tube of blood that was drawn from Mr. Avery in 1996, when he was 34.5 years old. Future study incorporating more samples and controls acquired from a range of surfaces and/or preservation media can shed further light on our ability to predict biological age using epigenetic markers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Epigenomics and Genomics Core Facilities at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Authors' Contributions

C.E.M., C.M., and D.B. conceived of and designed the study. D.B. and X.Y. extracted and prepared samples for sequencing. J.F., D.B., P.V., K.G., K.R., J.W.D., and C.M. analyzed data. All authors contributed to writing.

Sample Collection and Consent

All donors were consented for participation in the study according to the Declaration of Helsinki and were reimbursed $20.00 for their blood donation. They verified their age with a valid driver's license, and we then escorted them, with a representative from the law firm, to the executive garage so that one to two blood drops could be taken from their finger and deposited into the designated vehicle. None of the donors were HIV positive.

Author Disclosure Statement

P.V. is an employee of AbbVie, Inc. K.B. and X.Y. are employees of Zymo Research, Inc. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Information

Funding from the Irma T. Hirschl and Monique Weill-Caulier Charitable Trusts, Bert L and N Kuggie Vallee Foundation, the WorldQuant Foundation, Igor Tulchinsky, The Pershing Square Sohn Cancer Research Alliance, NASA (NNX14AH50G and NNX17AB26G), the National Institutes of Health (R01ES021006, R25EB020393, 1R21AI129851, 1R01MH117406, and U01DA053941), the NSF (1840275), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1151054), and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (G-2015-13964).

References

- 1. Smith ZD, Meissner A. DNA methylation: Roles in mammalian development. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14(3):204–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kim M, Costello J. DNA methylation: An epigenetic mark of cellular memory. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49(4):e322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Horvath S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 2013;14(10):R115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jones MJ, Goodman SJ, Kobor MS. DNA methylation and healthy human aging. Aging Cell. 2015;14(6):924–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen BH, Marioni RE, Colicino E, et al. DNA methylation-based measures of Biological age: Meta-analysis predicting time to death. Aging (Albany NY). 2016;8(9):1844–1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vidaki A, Kayser M. Recent progress, methods and perspectives in forensic epigenetics. Forensic Sci Int Genet. 2018;37:180–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li S, Garrett-Bakelman F, Perl AE, et al. Dynamic evolution of clonal epialleles revealed by methclone. Genome Biol. 2014;15(9):472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li S, Garrett-Bakelman FE, Chung SS, et al. Distinct evolution and dynamics of epigenetic and genetic heterogeneity in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Med. 2016;22(7):729–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Slieker RC, Relton CL, Gaunt TR, Slagboom PE, Heijmans BT. Age-related DNA methylation changes are tissue-specific with ELOVL2 promoter methylation as exception. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2018;11(1):25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Parson W. Age estimation with DNA: From forensic DNA fingerprinting to forensic (epi)genomics: A mini-review. Gerontology. 2018;64(4):326–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Horvath S, Langfelder P, Kwak S, et al. Huntington's disease accelerates epigenetic aging of human brain and disrupts DNA methylation levels. Aging (Albany NY). 2016;8(7):1485–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Krueger F, Andrews SR. Bismark: A flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(11):1571–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Akalin A, Kormaksson M, Li S, et al. methylKit: A comprehensive R package for the analysis of genome-wide DNA methylation profiles using high-throughput bisulfite sequencing. Genome Biol. 2012;13(10):R87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]