Abstract

Aim

To better understand the functionality of job crafting and its relationship with personality and job autonomy in the context of non‐Western health care as an adaptive problem‐solving work behaviour that is related to creativity.

Background

Job crafting could be a strategy nurses use to solve problems as health care organisations become more unpredictable.

Methods

This cross‐sectional study sampled 547 nurses from seven hospitals in Lebanon. Data were analysed using structural equation modelling (SEM).

Results

The job crafting dimensions of increasing structural job resources and increasing challenging job demands partially mediated the relationship between creativity and subjective well‐being, and they fully mediated the relationship between job autonomy and subjective well‐being. Creativity, job autonomy, and agreeableness were related to the approach job crafting dimensions, and two of these job crafting dimensions were in turn related to subjective well‐being.

Conclusion

Creative nurses tend to job craft more and this is associated with their subjective well‐being. Nurses high on extraversion and emotional stability experienced higher subjective well‐being.

Implications for Nursing Management

Nursing administration and leaders may want to create an environment fostering creativity and encouraging approach‐oriented job crafting.

Keywords: creativity, job autonomy, job crafting, Lebanon, nursing, personality, subjective well‐being

1. INTRODUCTION

Strategies that enhance work engagement and prevent burnout are essential for improving nursing working conditions (Laschinger et al., 2006). One such strategy is job crafting, which represents employee‐initiated work behaviours aimed at achieving a better fit between the employees' needs and preferences and their work (Tims et al., 2016). Given the many positive outcomes linked to job crafting (JC) (for a review, check Rudolph et al., 2017), it is necessary to explore JC in the context of nursing to understand how this profession can benefit from it.

Ample research has documented who is more likely to engage in JC (antecedents) and how beneficial or harmful JC can be to individuals and their workplace (Rudolph et al., 2017). There are, however, notable gaps. First, there are only a few studies that have used non‐WEIRD samples (e.g. Bell & Njoli, 2016). Job crafting originated in prototypically WEIRD contexts (Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic) (Henrich et al., 2010), where individual uniqueness is desirable, and adherence to hierarchy is not relevant. Such factors may facilitate JC—but are not equally present in all cultural contexts, where hierarchy is more valued or self‐expression more restricted. Second, no research has empirically investigated the relationship between JC and creativity although it has long been argued to be a theoretical underpinning of JC (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001), nor is there evidence on how personality in the Arab World is related to JC. Third, JC has never been explored in relation to non‐work‐related outcomes such as subjective well‐being (SWB).

In this study, we aim to assess JC in relationship to creativity and personality, as personal characteristics, and to job autonomy as a job characteristic that can optimize patient care (Kramer & Schmalenberg, 2003). We conduct our study in Lebanon, which is a non‐WEIRD context different in many ways from previously studied contexts.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. Job crafting

Job crafting is characterized by self‐initiated employee changes that accommodate employees' unique needs and preferences (Peeters et al., 2014). In this study, we adopt Tims and Bakker (2010)'s conceptualization of JC in terms of crafting job demands and resources: (1) increasing structural job resources (ISTJR), (2) decreasing hindering job demands (DHJD), (3) increasing social job resources (ISOJR) and (4) increasing challenging job demands (ICJD). We focus on the approach crafting JC dimensions (1, 3 & 4), since evidence on the benefits of the avoidance crafting dimension has been inconsistent (for a review, check Rudolph et al., 2017).

We expand our understanding of JC theoretically by showing that it is empirically related to creativity and personality in the Levant region and that it has benefits beyond the workplace that are linked to the individual's SWB. From a more practical point of view, our study also assesses the role of job autonomy for JC, since low autonomy has been shown to be one of the major reason's nurses leave their jobs (Sinclair, 2020).

2.2. Job crafting and creativity

Creativity has been frequently used to define JC, as the latter is a set of creative actions demonstrated by employees at work (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Only few studies, however, have tested the relationship between JC and creativity and have done so only with creativity as an outcome variable, not an antecedent (Demerouti et al., 2015). Job crafting can be a choice that individuals make in response to an unfavourable or negative situation, or one that is a misfit between their needs and preferences and their job. Through JC, people can actively improve work conditions, search for new ways of doing things, and advocate changes to for improvements, all of which are forms of employee creativity (Zhou & George, 2001). Accordingly, we predict that creativity is positively related to all three JC dimensions (H1).

2.3. Job crafting and personality

There is some evidence on the relationship between personality traits and JC (for a review, check Rudolph et al., 2017), but they are mostly restricted to Western contexts. Given the positive impact that JC can have, we argue it is relevant to understand personality as an antecedent of JC, as one of the most relevant conceptualizations of individual differences in general (Barrick & Mount, 1991), and one of the main predictors of SWB (Diener et al., 1999). Table 1 outlines the rationale for hypothesized relations between each of the seven API 1 personality facets and the approach dimensions of JC (H2:H8).

TABLE 1.

Relationships between job crafting and the arab personality inventory dimensions

| Personality Facet | Rationale | ISTJR | ISOJR | ICJD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intellect | Individuals who score high on intellect describe themselves as more rational, knowledgeable, and cultured (Zeinoun et al., 2017). We expect the relationship between the job crafting dimensions and intellect to be similar to that with openness, since the latter has been shown to be important for the development of proactive work behaviours (Grant & Ashford, 2008). | +ve (H2a) | +ve (H2b) | +ve (H2c) |

| Conscientiousness | Associations between conscientiousness and ISTJR and ICJD have been shown to be positive and that between ISOJR and conscientiousness has been shown to be small (Rudolph et al., 2017). | +ve (H3a) | ∅ (H3b) | +ve (H3c) |

| Extraversion | Wu and Li (2017) previously suggested that extraversion is key to facilitating proactive behaviour. Previous research has also found that extraversion is positively related to expanding resources and ICJD (Rudolph et al., 2017). | +ve (H4a) | +ve (H4b) | +ve (H4c) |

| Emotional Stability | High emotional stability has been shown to be positively related to ISTJR (Roczniewska & Bakker, 2016) and ICJD (Rudolph et al., 2017). Shaping one's job, even socially is more likely to happen among employees who are more emotional stable. | +ve (H5a) | +ve (H5b) | +ve (H5c) |

| Agreeableness | Tornau and Frese (2013) have shown that agreeableness is positively related to personal initiative. Since overall job crafting has been positively linked to agreeableness (Rudolph et al., 2017), we expect to find similar relationships between agreeableness and the approach job crafting dimensions. | +ve (H6a) | +ve (H6b) | +ve (H6c) |

| Conventionality | Conventionality in the Arab Personality Inventory relates to religiousness, following norms, being self‐righteous, and is the opposite of being a rule breaker (Zeinoun et al., 2017). Conventional employees will more likely abide by pre‐existing work processes and might thus be less likely to introduce changes to their jobs. | −ve (H7a) | −ve (H7b) | −ve (H7c) |

| Honesty–integrity | The personality factor honesty–integrity in the API is close to honesty–humility factor in Ashton and Lee (2001)’s six‐dimensional model of personality the HEXACO (Honesty‐Humility (H), Emotionality (E), Extraversion (X), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness (C) and Openness to Experience (O)). Generally, these individuals tend to avoid manipulating and taking advantage of others for their own benefit (Lee & Ashton, 2004). They also avoid deviation from a predefined job description and consequently not engage in job crafting. | −ve (H8a) | −ve (H8b) | −ve (H8c) |

The references mentioned in this table can be found in the reference list at the end of Appendix S1.

Abbreviations: +ve, positive relationship; ∅, no relationship; ICJD, Increasing Challenging Job Demands; ISOJR, Increasing Social Job Resources; ISTJR, Increasing Structural Job Resources; −ve, negative relationship.

2.4. Job crafting and job autonomy

Rudolph et al. (2017) found that all approach crafting dimensions are positively related to job autonomy. We expect to replicate this finding in our study and therefore expect job autonomy to be positively related to all three JC dimensions (H9a, b, &c).

2.5. Subjective well‐being

2.5.1. Job Crafting and SWB

Little is known about how work‐related variables such as JC influence overall life satisfaction, especially in health care where the high‐risk nature of the work can have implications for many domains of the employee's life. Job crafting helps employees establish a more positive self‐image, which influences satisfaction with the self (Diener & Diener, 2009). Accordingly, we hypothesize that JC is positively related to SWB (H10).

2.5.2. Personality and SWB

Personality is an important factor in predicting a person's SWB (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998). Previous research has shown that extraversion relates to positive affect, and low emotional stability to negative affect (Costa & McCrae, 1980). Accordingly, we argue that extraversion (H11a) and emotional stability (H11b) are positively linked to SWB. For the other personality facets, the evidence is less clear. Agreeableness and conscientiousness were argued to have an indirect relationship with well‐being (McCrae & Costa, 1991). Previous studies found no relationship between HEXACO's Honesty–Humility (closely related to API's Honesty–integrity) and SWB (e.g. Visser & Pozzebon, 2013). Similarly, openness to experience was found to be unrelated to SWB (DeNeve & Cooper, 1998), which McCrae and Costa (1991) speculated could be due to this facet being linked to increases in both negative and positive affect. Intellect is subsumed under openness to experience (John & Srivastava, 1999); we therefore expect the same (non‐) relation between Intellect and SWB. Conventionality indicates that a person is more religious and has less‐accepting attitudes to modern lifestyles. It is specific to the Arab Levant region (see the Appendix S1 for more information about the study's context) and the personality model utilized (API). Conventionality per se might not have any impact on how individuals rate the satisfaction with their lives and consequently SWB. Due to the lack of empirical evidence for a relationship between conscientiousness, agreeableness, honesty–integrity, intellect, conventionality and SWB, we refrain from specifying direct hypotheses.

2.5.3. Creativity and SWB

Amabile et al. (2005) indicated that positive affect has a strong and dynamic relationship with creativity (they either occur before one another or simultaneously). Goff (1993) argued that creativity is essential for personal adjustments that in turn positively influence person's satisfaction with life. We therefore hypothesize that creativity is positively linked to SWB (H12).

2.5.4. Job autonomy and SWB

Individuals seek control over their environment as this is necessary for their well‐being (Bond & Bunce, 2003). Job autonomy increases employees' sense of control and encourages them to actively enhance their situation at work to achieve greater personal meaning (Wu et al., 2015). We predict that job autonomy is positively related to SWB (H13).

2.6. Job crafting as a lynchpin of relations

2.6.1. Personality, job crafting and SWB

Personality explains a substantial amount of the variation in SWB scores (32%–56%, Hayes & Joseph, 2003); however, it is unclear how personality would be linked to well‐being. We propose JC as a psychological mechanism, a mediator, linked to both well‐being and personality. Personality facets might relate differently to SWB and in some cases may only be indirectly related to SWB via mediation. Extraversion and emotional stability are directly linked to higher SWB and we argue they are linked to all three JC dimensions. Accordingly, we hypothesize that all three JC dimensions play a role in at least partially mediating the relationship between these two personality facets and SWB (H14a &b).

2.6.2. Creativity, job crafting and SWB

Goff (1993) argued that creativity coupled with personal adjustments can positively impact a person's satisfaction with life. Accordingly, we argue that all three JC dimensions play a role in partially mediating the relationship between creativity and SWB (H15).

2.6.3. Job autonomy, job crafting and SWB

Previous research has indicated that job autonomy is related to JC (Rudolph et al., 2017) and to life satisfaction (Prottas, 2008). Accordingly, we hypothesize that all three approach JC dimensions play a role in partially mediating the relationship between job autonomy and SWB (H16).

3. METHOD

3.1. Sample and procedure

After obtaining ethical approval, data were collected from nurses working in seven hospitals in Lebanon using surveys. A detailed description of the context of the study is provided in the Appendix S1. Out of 994 surveys, 547 were completed and returned. This is a response rate of 55%, which is relatively high compared to other studies conducted in a similar context (Kalisch et al., 2013; Marini et al., 2009). The surveys took around 25 min to complete. The demographic characteristics are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Demographic characteristics

| Characteristic (mean ± SD) | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 124 | 24.27 |

| Female | 384 | 75.15 |

| Age (30.65 ± 7.05) | ||

| <20 | 7 | 1.37 |

| 20–30 | 236 | 46.18 |

| 31–40 | 157 | 30.72 |

| >40 | 40 | 7.83 |

| Position | ||

| Registered nurse | 351 | 68.69 |

| Practical nurse | 119 | 23.29 |

| Other nursing positions | 29 | 5.67 |

| Highest education | ||

| Diploma in nursing | 95 | 18.59 |

| Baccalaureate a Technical (BT) in nursing | 71 | 13.89 |

| Technique Supérieure b (TS) in nursing | 49 | 9.59 |

| License Technique b (LT) in nursing | 76 | 14.87 |

| Bachelor of Sciences (BS) in nursing | 146 | 28.57 |

| Masters (MS) in nursing | 41 | 8.02 |

| Other | 18 | 3.52 |

| Organisational tenure (7.64 ± 5.86) | ||

| <1 year | 29 | 5.67 |

| 1–5 years | 179 | 35.03 |

| 6–10 years | 146 | 28.57 |

| 11–20 years | 110 | 21.53 |

| >20 years | 22 | 4.30 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full‐time | 478 | 93.54 |

| Part‐time | 22 | 4.30 |

Some numbers are less than 511 due to missing values.

Equivalent to the last year of high school.

Technical degrees.

3.2. Measures

Personality was measured using the API‐Short (Unpublished data). Job crafting was measured using the JC scale (Tims et al., 2012). Job autonomy was measured using a subscale of Autonomy at Work Scale (Hackman & Oldman, 1975). To measure the affective dimension SWB, we administered the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988). To assess the cognitive dimension of SWB, we measured life satisfaction using the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) (Diener, 2000; Diener et al., 1985). To measure creativity, 2 we used the self‐report scale developed by Miron et al. (2004). Participants responded on a five‐point Likert scale in all the scales. All scales had very good reliabilities (see Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Instruments’ Cronbach's α

| Instrument | Sub‐scale | Cronbach's α | Example Items | Scale Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Arab Personality Inventory (API) | Honesty–integrity | 0.85 | ‘I sometimes like it when others feel sorry for me’; ‘I am exploitative’ | Not Applicable at all to Totally Applicable |

| Emotional stability | 0.80 | ‘I am generally firm with others’; ‘I am a stubborn person’ | ||

| Agreeableness | 0.88 | ‘I am fair to/with others’; ‘I encourage others for the better’ | ||

| Conscientiousness | 0.91 | ‘I am generally firm with others’; ‘I am a brave person’ | ||

| Extraversion | 0.83 | ‘I am entertaining to those around me’; ‘I am a sociable person’ | ||

| Intellect | 0.82 | ‘I think realistically about situations’; ‘I am intelligent’ | ||

| Conventionality | 0.67 | ‘I am generally obedient’; | ||

| Job Crafting (JC) | Increasing structural job resources | 0.88 | ‘I try to develop my capabilities’; ‘I try to develop myself professionally’ | Never to Very Often |

| Increasing social job resources | 0.86 | ‘I ask my supervisor to coach me’; ‘I ask whether my supervisor is satisfied with my work’ | ||

| Increasing challenging job demands | 0.85 | ‘When an interesting project comes along, I proactively offer myself’; ‘When there is not much to do at work, I see it as a chance to start new projects’ | ||

| Job Autonomy | Job Autonomy | 0.78 | ‘I can choose my work tasks’; ‘I can choose the way I perform the work tasks’ | Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree |

| Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) | Positive Affect | 0.88 | ‘Excited’; ‘Interested’ | Very Slightly or Not at All to Extremely |

| Negative Affect | 0.88 | ‘Distressed’; ‘Upset’ | ||

| Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) | SWLS | 0.87 | ‘In most ways my life is close to my ideal’; ‘I am satisfied with my life’ | Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree |

| Creativity | Creativity | 0.90 | ‘I have a lot of creative ideas’; ‘I prefer tasks that enable me to think creatively’ | Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree |

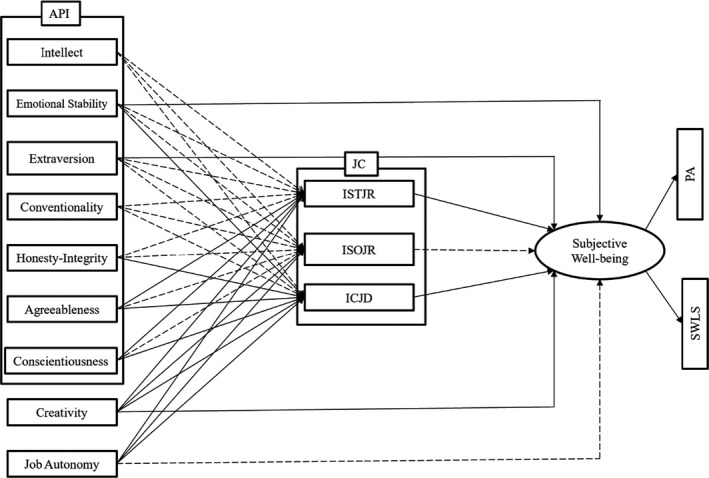

After removing the cases that had missingness rates higher than 25%, to reduce bias (Tab achnick & Fidell, 2012), we ended up with a sample size of 511. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 4. We conducted structural equation modelling (SEM) using MPlus (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). We used multiple imputation in MPlus to impute remaining missing values before conducting the analysis. Figure 1 shows the theoretical model that we tested. All paths in the model were freely estimated. Subjective well‐being was modelled as one latent variable, and all other variables were modelled as manifest variables. We first tested whether the structure we adopted for SWB (as a latent factor of PA and SWLS) and that of the API (as a more recent tool) is applicable in our sample to test construct validity. The tested structures were found to have adequate fit (the model fit information is presented in the Appendix S2).

TABLE 4.

Means, standard deviations, and zero‐order correlations

| Variables | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | ISTJR | 4.19 (0.69) | (0.88) | |||||||||||||

| 2. | ISOJR | 3.27 (0.93) | 0.28** | (0.86) | ||||||||||||

| 3. | ICJD | 3.65 (0.77) | 0.51** | 0.48** | (0.85) | |||||||||||

| 4. | Positive Affect | 3.57 (0.70) | 0.48** | 0.21** | 0.44** | (0.88) | ||||||||||

| 5. | Satisfaction with Life | 4.52 (1.36) | 0.12** | 0.08 | 0.19** | 0.27** | (0.87) | |||||||||

| 6. | Creativity | 3.73 (0.74) | 0.43** | 0.20** | 0.48** | 0.45** | 0.24** | (0.90) | ||||||||

| 7. | Autonomy | 3.55 (0.87) | 0.31** | 0.25** | 0.31** | 0.25** | 0.27** | 0.25** | (0.78) | |||||||

| 8. | honesty‐integrity | 3.98 (0.87) | 0.24** | −0.16** | 0.05 | 0.12** | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.03 | (0.85) | ||||||

| 9. | Emotional Stability | 3.12 (0.78) | 0.028 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.14** | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.37** | (0.80) | |||||

| 10. | Agreeableness | 4.28 (0.67) | 0.56** | 0.18** | 0.38** | 0.40** | 0.12** | 0.32** | 0.26** | 0.40** | 0.01 | (0.88) | ||||

| 11. | Conscientiousness | 4.48 (0.67) | 0.54** | 0.13** | 0.35** | 0.35** | 0.15** | 0.29** | 0.27** | 0.33** | −0.02 | 0.68** | (0.91) | |||

| 12. | Extraversion | 3.93 (0.64) | 0.42** | 0.14** | 0.34** | 0.44** | 0.16** | 0.38** | 0.24** | 0.14** | −0.13** | 0.59** | 0.56** | (0.83) | ||

| 13. | Intellect | 3.93 (0.58) | 0.54** | 0.18** | 0.41** | 0.49** | 0.13** | 0.43** | 0.29** | 0.20** | −0.10* | 0.71** | 0.65** | 0.63** | (0.82) | |

| 14. | Unconventionality | 4.08 (0.54) | 0.44** | 0.13** | 0.27** | 0.33** | 0.15** | 0.25** | 0.24** | 0.33** | −0.01 | 0.69** | 0.61** | 0.46** | 0.57** | (0.67) |

Values on the diagonal in parentheses are alpha coefficients.

All values are based on the raw unimputed data.

Abbreviations: ICJD, Increasing Challenging Job Demands; ISOJR, Increasing Social Job Resources; ISTJR, Increasing Structural Job Resources; M, Mean; SD, standard deviation.

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2‐tailed).

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2‐tailed).

FIGURE 1.

Proposed theoretical model. API, Arab Personality Inventory; JC, Job Crafting; ISTJR, Increasing Structural Job Resources; ISOJR, Increasing Social Job Resources; ICJD, Increasing Challenging Job Demands

4. RESULTS

4.1. Hypotheses testing

The hypotheses were tested with SEM whereby the hypothesized model included paths from the seven personality factors, creativity and job autonomy to the three JC dimensions, which in turn had paths to SWB (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Resulting standardized paths of the hypothesized partial mediation model. API, Arab Personality Inventory; JC, Job Crafting; ISTJR, Increasing Structural Job Resources; ISOJR, Increasing Social Job Resources; ICJD, Increasing Challenging Job Demands; SWB, Subjective Well‐being; SWLS, Satisfaction with Life Scale; PA, Positive Affect. Dashed arrows indicate pathways that are not significant

4.1.1. Full versus partial mediation

We compared two mediation models: (a) a partial mediation model with direct paths from extraversion, emotional stability, creativity and the three dimensions of JC to SWB in addition to all the indirect paths going through the subdimensions JC to SWB; and (b) a full mediation model in which only indirect relationships (via the three subdimensions of JC) between the antecedents and SWB are included. The partial mediation model fit the data better than the full mediation one (see fit indices in Table 5). Accordingly, we chose the partial mediation model as it allows for more relationships to be modelled.

TABLE 5.

Model fit information

| Model | χ 2 | df | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Mediation Model | 126.38, p < .001 | 20 | 0.102, 90% CI: 0.085, 0.119 | 0.887 | 0.689 | 5,662.986 | 5,853.623 |

| Partial Mediation Model | 64.108, p < .001 | 16 | 0.077, 90% CI: 0.058; 0.098 | 0.949 | 0.824 | 5,605.030 | 5,812.612 |

Abbreviations: AIC, Akaike information criterion; BIC, The Bayesian information criterion; CFI, Comparative fit index; df, degrees of freedom; RMSEA, root‐mean‐square error of approximation; TLI, Tucker–Lewis index; χ 2, Chi‐squared.

4.1.2. Direct relationships

As expected, all three JC dimensions were significantly positively related to job autonomy and self‐reported creativity. The results also indicated that only ISTJR and ICJD were significantly related to conscientiousness (see also Table 1).

As predicted, ICJD and ISOJR were significantly negatively related to honesty‐integrity, but ISTJR was not (unlike what we expected). Only ICJD was significantly related to emotional stability. The JC dimensions ISTJR and ICJD were significantly related to SWB. Finally, intellect, extraversion and conventionality were unrelated to the three dimensions of JC.

As for the direct relationships between the antecedents and the outcome variable, our results (standardized coefficients) showed that extraversion, emotional stability and creativity were significantly and directly related to SWB. However, no significant direct relationship was detected between job autonomy and SWB (see Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Direct effects

| Effect on SWB | Effect on ISTJR | Effect on ISOJR | Effect on ICJD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Estimate | Estimate | Estimate | ||||

| API Emotional Stability | 0.11* | API Conscientiousness | 0.28** | API Conscientiousness | 0.01 | API Conscientiousness | 0.1* |

| API Extraversion | 0.29** | API Emotional Stability | 0.035 | API Emotional Stability | 0.07 | API Emotional Stability | 0.08* |

| Job Autonomy | 0.09 | API honesty‐integrity | 0.008 | API honesty‐integrity | −0.29** | API honesty‐integrity | −0.11* |

| Creativity | 0.22** | API Intellect | 0.111 | API Intellect | −0.01 | API Intellect | 0.06 |

| ISTJR | 0.22** | API Extraversion | −0.026 | API Extraversion | −0.02 | API Extraversion | 0.02 |

| ISOJR | 0 | API Conventionality | 0.012 | API Conventionality | 0 | API Conventionality | −0.04 |

| ICJD | 0.2* | API Agreeableness | 0.23** | API Agreeableness | 0.23** | API Agreeableness | 0.18* |

| Job Autonomy | 0.2* | Job Autonomy | 0.12** | Job Autonomy | 0.14** | ||

| Creativity | 0.22** | Creativity | 0.11* | Creativity | 0.33** | ||

Abbreviations: API, Arab Personality Inventory; ICJD, Increasing Challenging Job Demands; ISOJR, Increasing Social Job Resources; ISTJR, Increasing Structural Job Resources; SWB, Subjective Well‐being.

*p < .05; **p < .01.

4.1.3. Indirect relationships

Our results (see Table 7) showed a significant indirect relationship between job autonomy, creativity and SWB through ISTJR and ICJD, but not through ISOJR. We discuss reasons for and implications of these relationships below.

TABLE 7.

Indirect effects

| Effect of API Emotional Stability on SWB | Effect of API Extraversion on SWB | Effect of Job Autonomy on SWB | Effect of Creativity on SWB | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Estimate | Estimate | Estimate | ||||

| via ISTJR | 0.01 | via ISTJR | −0.00 | via ISTJR | 0.01* | via ISTJR | 0.03* |

| via ISOJR | 0 | via ISOJR | 0 | via ISOJR | 0 | via ISOJR | 0 |

| via ICJD | 0.01 | via ICJD | 0 | via ICJD | 0.02* | via ICJD | 0.05* |

Abbreviations: API, Arab Personality Inventory; ICJD, Increasing Challenging Job Demands; ISOJR, Increasing Social Job Resources; ISTJR, Increasing Structural Job Resources; SWB, Subjective Well‐being.

*p < .05; **p < .01.

5. DISCUSSION

In this study, we set out to investigate how individual‐level factors, namely personality, and job‐level factors, namely job autonomy relate to JC. We also assessed the potential benefits that JC may have for nurses by investigating the relation between JC and well‐being. We furthermore empirically tested the relationship between JC and creativity, which has been proposed to be a prerequisite of JC (although no direct evidence has been reported). Finally, we examined whether the concept of JC is structurally valid a non‐WEIRD sample.

We find that JC is an important mediator through which creativity and job autonomy relate to factors beyond the workplace: both associated with SWB among our sample of nurses. While we find that the scales exhibit good structural properties in Lebanon, and although some relations were in line with previous research conducted in WEIRD, more individualistic contexts, we also find that some relations were not in line with previous research. We showcase the differential role that each of the three JC dimensions in our study has in the relationship between personality, job autonomy, creativity and SWB. Our theoretical contribution is threefold. First, investigate the concept of JC in a non‐Western context. Second, we provide the first empirical evidence on the relationship between creativity and JC. Third, we show that JC has benefits that go beyond the employee's work context.

5.1. The role of job crafting for nurses

Unlike what we expected, extraversion was unrelated to all JC dimensions. This might be specific to the nursing profession: extraverted aspects such as assertiveness and dominance may not be conducive in the nursing environment where nurses need to act in accordance with many expectations in terms of regulations and teamwork. Our study also found that emotional stability was related to only ICJD.

The link we found between emotional stability and ICJD might be better understood in the light of its relationship with one of the main problems that nurses suffer from: burnout. Bakker et al. (2004) found that job demands were the most important antecedents of the emotional exhaustion component of burnout. This might be a reason why nurses who score high on emotional stability choose to increase their challenging demands because they would also be able to execute them properly. Unlike what was expected, honesty‐integrity was not related ISTJR. It might be the case that engaging in this JC dimension does not involve overstepping any self‐designated boundary employees might have set for themselves.

As expected, personality was associated with SWB: honesty‐integrity and agreeableness predict SWB indirectly through ICJD. Scoring high on these facets could be related to an increased the sensitivity to environmental alterations, such as ICJD, making them happier with their lives. Extraversion and emotional stability are directly associated with SWB. Scoring high on the latter two personality facets may predispose individuals to be happier in life regardless of work experiences (McCrae & Costa, 1991).

5.2. Creativity and job crafting among nurses

Job crafting has been described before as a set of creative work behaviours demonstrated by employees (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Proactive behaviours such as JC may be relevant for the translation of creative ideas into action (for a similar argument on voice, see Frese, 2000). Nurses who score high on creativity are more likely (and able) to engage in approach crafting, which provides insight on how JC can be one of the adaptive and problem‐solving techniques that creative nurses engage in.

Our mediation model provides insight into creativity in the nursing context as we suggest that it is linked to SWB through JC. We also learn more about how JC can go beyond the boundaries of work and spillover to the nurse's personal life. This is particularly important given the emotionally and physically demanding nature of their profession and how taxing this can be to their well‐being (Diefendorff et al., 2011).

5.3. The functionality of job crafting in a non‐WEIRD context

Our study explores the relationships between personality, creativity, job autonomy, and JC in a non‐WEIRD context, Lebanon. Nurses who engage it ISTJR and ICJD score higher on SWB. Work‐related benefits of JC for the employee and organisation are well documented (see Rudolph et al., 2017), and these results show that JC is also associated with life outside of work. Engaging in ISTJR and ICJD might be satisfying needs that have a direct relation with the employee's overall SWB. A closer examination of Lebanon as the sample context might help us better understand why we did not find a similar relation between ISOJR and SWB.

Since feedback seeking behaviour (ISOJR) is mostly about self‐development (seeking advice and mentorship), it might not be related to life satisfaction since it is less valued in a collectivistic culture such as Lebanon. This is in line with the reasoning that life domains that are congruent with one's main values are relatively more important for one's life satisfaction (Oishi et al., 1999), which may not apply here.

Interestingly, while JC is directly associated with SWB, job autonomy is not. We found job autonomy to relate to SWB only through the engagement in ISTJR and ICJD. One possible reason could be that in a more collectivistic culture such as Lebanon, where social interactions at work are common, shaping one's job socially is not perceived as a way of exercising one's job autonomy. These two JC dimensions seem to be the active catalysts in the relationship between job autonomy and SWB although job autonomy has long been touted as a job characteristic that has direct positive effects on employees' work attitudes (e.g. job satisfaction) and behaviours (e.g. creative performance; Deci et al., 2017; Hackman & Oldman, 1975).

5.4. Limitations

First, our data are correlational and can therefore not examine causal directionality. That is, although our results show that personality, creativity and autonomy are predictive of SWB, the opposite may also apply. Second, self‐selection bias might have influenced our study. For example, overworked nurses close to burnout may not have had the time or motivation to participate. Finally, we suggest culture‐specific pathways, but the present data do not directly allow for testing the role of culture for JC and related variables in a comparative design.

6. CONCLUSION

In this study, we find clear evidence that engaging in job crafting (JC) in the nursing context has benefits that go beyond the workplace since it is positively associated with subjective well‐being (SWB). This possible spillover to nurses' personal lives highlights how an emotionally demanding profession, such as nursing, could benefit from JC. Our study finds empirical support that creativity is related to the approach dimension of JC, which might be one of the ways through which nurses use creativity to adapt their work behaviour. Our results show that while agreeableness, conscientiousness, honesty‐integrity and emotional stability predict the engagement in JC among nurses, other personality dimensions do not. Finally, our study further enriches our understanding of job autonomy by highlighting that it has a positive influence on one's life only if JC is considered as a mediator. We find some evidence that JC partially applies in a non‐WEIRD context, but we also see that many aspects are different from previous research.

7. PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS FOR NURSING MANAGEMENT

Our results have managerial implications relating to the selection and training of nurses. Health care organisations may benefit from including personality and creativity as part of their selection criteria, as our results indicated that they are related to engagement in JC. This is particularly relevant considering that engaging in JC behaviours can have a positive influence on the work well‐being and performance of nurses (Gordon et al., 2018). Furthermore, our results suggest that engaging in JC is significantly related to higher SWB. High SWB has been linked to lower levels of burnout among nurses (Qu & Wang, 2015). Alternatively, health care organisations can design targeted training programmes that focus on empowering nurses with the tools needs to shape their jobs while still maintaining standard clinical procedures.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. They also declare that they agree with the content of this manuscript.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The present study was approved by Tilburg Ethics Review Board (EC‐2017.EX99) and the American University of Beirut Ethical Review board (OSB.LD.16).

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Ghazzawi R, Bender M, Daouk‐Öyry L, van de Vijver FJR, Chasiotis A. Job crafting mediates the relation between creativity, personality, job autonomy and well‐being in Lebanese nurses. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29:2163–2174. 10.1111/jonm.13357

Fons J.R. van de Vijver passed away in June 2019 when the manuscript was in the final stage of preparation for submission.

Footnotes

Since we investigate a non‐Western sample, we opted for a culturally appropriate personality conceptualization and assessment by Zeinoun et al. (2017). We thereby avoid a blind exportation of Western instruments (Van de Vijver & Leung, 2001). The Arab Personality Inventory (API) maps onto the Big Five, but assesses seven rather than five dimensions (conscientiousness, intellect, emotional stability, extraversion, agreeableness, honestly/integrity and conventionality).

We sought to assess creativity using an adapted version of the brick test and self‐report measure. We excluded the first since our sample did not provide sufficiently many responses on the task (only 31% were complete).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The authors will make all the raw data and the steps followed in the analysis available on Dataverse (https://dataverse.org/). This will be in form of a data package attachment that can be shared. Making the data available on dataverse is standard procedure at the Department of Social Psychology at Tilburg University, and is required by our data management officers. This will include a metadata file, listing all relevant information, the materials, the raw data file, the (annotated) syntax or code used to produce the results reported in the publication.

REFERENCES

- Amabile, T. M. , Barsade, G. , Mueller, S. , & Staw, M. (2005). Affect and creativity at work. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50, 367–403. 10.2189/asqu.2005.50.3.367 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A. B. , Demerouti, E. , & Verbeke, W. (2004). Using the job demands‐resources model to predict burnout and performance. Human Resource Management: Published in Cooperation with the School of Business Administration, the University of Michigan and in Alliance with the Society of Human Resources Management, 43, 83–104. 10.1002/hrm.20004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrick, M. R. , & Mount, M. K. (1991). The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta‐analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44, 1–26. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb00688.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell, C. , & Njoli, N. (2016). The role of big five factors on predicting job crafting propensities amongst administrative employees in a South African tertiary institution. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 14, 1–11. 10.4102/sajhrm.v14i1.702 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bond, F. W. , & Bunce, D. (2003). The role of acceptance and job control in mental health, job satisfaction, and work performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 1057. 10.1037/0021-9010.88.6.1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P. T. , & McCrae, R. R. (1980). Influence of extraversion and neuroticism on subjective well‐being: Happy and unhappy people. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 668. 10.1037/0022-3514.38.4.668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L. , Olafsen, A. H. , & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self‐determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 19–43. 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti, E. , Bakker, A. B. , & Gevers, J. M. (2015). Job crafting and extra‐role behavior: The role of work engagement and flourishing. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 91, 87–96. 10.1016/j.jvb.2015.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeNeve, K. M. , & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta‐analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well‐being. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 197. 10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diefendorff, J. M. , Erickson, R. J. , Grandey, A. A. , & Dahling, J. J. (2011). Emotional display rules as work unit norms: A multilevel analysis of emotional labor among nurses. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16, 170. 10.1037/a0021725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well‐being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55, 34. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. , & Diener, M. (2009). Cross‐cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self‐esteem. In Diener E. (Ed.), Culture and well‐being: The collected works of Ed Diener (pp. 71–91). Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. , Emmons, R. A. , Larsen, R. J. , & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. , Suh, E. M. , Lucas, R. E. , & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well‐being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276. 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frese, M. (2000). The changing nature of work. In Chmiel N. (Ed.), Introduction to work and organizational psychology (pp. 424–439). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Goff, K. (1993). Creativity and life satisfaction of older adults. Educational Gerontology: An International Quarterly, 19, 241–250. 10.1080/0360127930190304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, H. J. , Demerouti, E. , Le Blanc, P. M. , Bakker, A. B. , Bipp, T. , & Verhagen, M. A. (2018). Individual job redesign: Job crafting interventions in healthcare. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 104, 98–114. 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A. M. , & Ashford, S. J. (2008). The dynamics of proactivity at work. Research in organizational behavior, 28, 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hackman, R. J. , & Oldman, G. R. (1975). General job satisfaction scale. In Cook J. D., Hepworthe S. J., Wall T. D., & Warr P. B. (Eds.), The experience of work: A compendium and review of 249 measures and their use (pp. 12–36). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, N. , & Joseph, S. (2003). Big 5 correlates of three measures of subjective well‐being. Personality and Individual Differences, 34, 723–727. 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00057-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich, J. , Heine, S. J. , & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33, 61–83. 10.1017/S0140525X0999152X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John, O. P. , & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In Pervin L. A., & John O. P. (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research, (Vol. 2, pp. 102–138). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch, B. J. , Doumit, M. , Lee, K. H. , & Zein, J. E. (2013). Missed nursing care, level of staffing, and job satisfaction: Lebanon versus the United States. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 43, 274–279. 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31828eebaa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M. , & Schmalenberg, C. E. (2003). Magnet hospital nurses describe control over nursing practice. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 25, 434–452. 10.1177/0193945903025004008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laschinger, H. K. S. , Wong, C. A. , & Greco, P. (2006). The impact of staff nurse empowerment on person‐job fit and work engagement/burnout. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 30, 358–367. 10.1097/00006216-200610000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. , & Ashton, M. C. (2004). Psychometric properties of the HEXACO personality inventory. Multivariate behavioral research, 39(2), 329–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini, S. D. , Hasman, A. , & Huijer, H. A. S. (2009). Information technology for medication administration: Assessing bedside readiness among nurses in Lebanon. International Journal of Evidence‐Based Healthcare, 7, 49–58. 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2008.00119.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae, R. R. , & Costa, P. T. Jr (1991). Adding Liebe und Arbeit: The full five‐factor model and well‐being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17, 227–232. 10.1177/014616729101700217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miron, E. , Erez, M. , & Naveh, E. (2004). Do personal characteristics and cultural values that promote innovation, quality, and efficiency compete or complement each other? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 175–199. 10.1002/job.237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K. , & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus user’s guide. In. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi, S. , Diener, E. F. , Lucas, R. E. , & Suh, E. M. (1999). Cross‐cultural variations in predictors of life satisfaction: Perspectives from needs and values. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 980–990. 10.1177/01461672992511006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters, M. C. W. , De Jonge, J. , & Taris, T. W. (2014). An introduction to contemporary work psychology. Wiley‐Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Prottas, D. (2008). Do the self‐employed value autonomy more than employees? Research across four samples. Career Development International, 13, 33–45. 10.1108/13620430810849524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qu, H.‐Y. , & Wang, C.‐M. (2015). Study on the relationships between nurses' job burnout and subjective well‐being. Chinese Nursing Research, 2, 61–66. 10.1016/j.cnre.2015.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roczniewska, M. , & Bakker, A. B. (2016). Who seeks job resources, and who avoids job demands? The link between dark personality traits and job crafting. The Journal of Psychology, 150(8), 1026–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, C. W. , Katz, I. M. , Lavigne, K. N. , & Zacher, H. (2017). Job crafting: A meta‐analysis of relationships with individual differences, job characteristics, and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 102, 112–138. 10.1016/j.jvb.2017.05.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, S. K. (2020). Understanding Why Nurses Leave — And how to get nurses to stay. Retrieved from https://www.medpagetoday.com/nursing/nursing/87742 [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B. G. , & Fidell, L. S. (2012). Using multivariate statistics (Vol. 6). Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Tims, M. , & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36, 1–9. 10.4102/sajip.v36i2.841 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tims, M. , Bakker, A. B. , & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80, 173–186. 10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tims, M. , Derks, D. , & Bakker, A. B. (2016). Job crafting and its relationships with person–job fit and meaningfulness: A three‐wave study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 92, 44–53. 10.1016/j.jvb.2015.11.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Vijver, F. , & Leung, K. (2001). Personality in cultural context: Methodological issues. Journal of Personality, 69, 1007–1031. 10.1111/1467-6494.696173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser, B. A. , & Pozzebon, J. A. (2013). Who are you and what do you want? Life aspirations, personality, and well‐being. Personality and Individual Differences, 54, 266–271. 10.1016/j.paid.2012.09.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D. , Clark, L. A. , & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063. 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wrzesniewski, A. , & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Academy of Management Review, 26, 179–201. 10.5465/amr.2001.4378011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.‐H. , & Li, W.‐D. (2017). Individual differences in proactivity: A developmental perspective. In Parker S. K., & Bindl U. K. (Eds.), Proactivity at work: Making things happen in organizations. New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.‐H. , Luksyte, A. , & Parker, S. K. (2015). Overqualification and subjective well‐being at work: The moderating role of job autonomy and culture. Social Indicators Research, 121, 917–937. 10.1007/s11205-014-0662-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeinoun, P. , Daouk‐Öyry, L. , Choueiri, L. , & Van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2017). A mixed‐methods study of personality conceptions in the Levant: Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and the West Bank. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113, 453. 10.1037/pspp0000148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J. , & George, J. M. (2001). When job dissatisfaction leads to creativity: Encouraging the expression of voice. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 682–696. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

The authors will make all the raw data and the steps followed in the analysis available on Dataverse (https://dataverse.org/). This will be in form of a data package attachment that can be shared. Making the data available on dataverse is standard procedure at the Department of Social Psychology at Tilburg University, and is required by our data management officers. This will include a metadata file, listing all relevant information, the materials, the raw data file, the (annotated) syntax or code used to produce the results reported in the publication.