Abstract

Eukaryotic algae are photosynthetic organisms capable of exploiting sunlight to fix carbon dioxide into biomass with highly variable genetic and metabolic features. Information on algae metabolism from different species is inhomogeneous and, while green algae are, in general, more characterized, information on red algae is relatively scarce despite their relevant position in eukaryotic algae diversity. Within red algae, the best‐known species are extremophiles or multicellular, while information on mesophilic unicellular organisms is still lacunose. Here, we investigate the photosynthetic properties of a recently isolated seawater unicellular mesophilic red alga, Dixoniella giordanoi. Upon exposure to different illuminations, D. giordanoi shows the ability to acclimate, modulate chlorophyll content, and re‐organize thylakoid membranes. Phycobilisome content is also largely regulated, leading to almost complete disassembly of this antenna system in cells grown under intense illumination. Despite the absence of a light‐induced xanthophyll cycle, cells accumulate zeaxanthin upon prolonged exposure to strong light, likely contributing to photoprotection. D. giordanoi cells show the ability to perform cyclic electron transport that is enhanced under strong illumination, likely contributing to the protection of Photosystem I from over‐reduction and enabling cells to survive PSII photoinhibition without negative impact on growth.

1. INTRODUCTION

Organisms performing oxygenic photosynthesis exploit sunlight to fix CO2 into biomass thanks to the activity of photosystem (PS) I and II, two multiprotein supercomplexes located in the thylakoid membranes. Both photosystems involved in oxygenic photosynthesis are composed of a core complex responsible for the charge separation and electron transfer reactions that are highly conserved among photosynthetic organisms, both prokaryotic and eukaryotic. Photosystems also include an antenna system to increase the light‐harvesting capacity. Antenna proteins diverged during evolution, possibly also due to adaptation to different ecological niches. In cyanobacteria and red algae, the ability to capture light is increased by soluble protein complexes, called phycobilisomes (PBS), that bind pigments like phycocyanin and phycoerythrin. In most eukaryotes, instead, the antenna system is composed of hydrophobic light harvesting complexes (LHC) proteins, localized in the thylakoid membranes and bind chlorophyll (Chl) and carotenoids (Car). In different eukaryotic groups, the LHC themselves diversified into various subfamilies, such as LHCA/B found in green algae and plants or LHCF in diatoms (Büchel, 2015).

Photosynthetic activity is highly influenced by environmental factors like illumination intensity, temperature, CO2, and nutrient availability. Many environmental conditions can drive the photosystems to saturation and over‐reduction, with the possible production of various Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) causing oxidative damage of the photosynthetic apparatus (photoinhibition) (Li et al., 2009; Murata et al., 2007; Szabó et al., 2005). To thrive in highly variable environmental conditions, photosynthetic organisms evolved multiple mechanisms to modulate photosynthetic activity depending on the environmental conditions, limiting over‐reduction and ROS formation. These regulatory mechanisms have different activation timescales, enabling responses to short‐term and long‐term dynamics of the environmental factors (Eberhard et al., 2008; Walters, 2005). The long‐term acclimation response involves modulation of the composition of the photosynthetic apparatus according to irradiance intensity, regulating Chl and Car content (Falkowski & LaRoche, 1991; Walters, 2005). On a shorter timescale, photosynthetic organisms instead activate mechanisms for the modulation of light harvesting efficiency, such as non‐photochemical quenching (NPQ), driving the dissipation of excess excitation energy as heat (Li et al., 2009). Strong illumination also activates the xanthophyll cycle, where zeaxanthin is synthesized from pre‐existing violaxanthin, further contributing to the protection from ROS (Havaux et al., 2007). Photosynthetic electron transport is also regulated by the presence of alternative electron transport mechanisms, such as cyclic electron flow (CEF) and pseudo‐cyclic electron flow (Shikanai, 2014), that were shown to be particularly important to protect PSI from over‐reduction and damage (Allahverdiyeva et al., 2015; Storti et al., 2020).

All photosynthetic organisms present multiple regulatory mechanisms, a clear indication that modulation of photosynthesis is essential. On the other hand, not all mechanisms are conserved in all organisms, and interesting differences are observed in different species, possibly in correlation with evolutionary history and colonization of specific ecological niches (Alboresi et al., 2019; Goss & Lepetit, 2015; Quaas et al., 2014). The exploration of the diversity of regulatory responses in various phylogenetic groups thus represents a valuable source of information for a better understanding of their molecular mechanisms and biological role.

In this context, microalgae are particularly interesting since they are highly diverse, with more than 200,000 estimated species colonizing a wide range of ecosystems (Bleakley & Hayes, 2017). Eukaryotic algae originated from a primary endosymbiosis event approximately 1600 million years ago (Mya), which gave origin to Rhodophyta (red algae), Chlorophyta (green algae), and Glaucophyta (Gaignard et al., 2019). Diverse clades of photosynthetic organisms, including heterokontophytes, dinoflagellates, and haptophytes, originated through secondary and tertiary endosymbioses, thus further increasing the biodiversity of these organisms. Most of these latter endosymbiosis events involved phototrophic red microalgae, which thus have a central place in the evolution of photosynthetic organisms (Keeling, 2013).

Red algae (Rhodophyta) are estimated to include more than 7000 species, consisting of both micro and macroalgae (Guiry & Guiry, 2021). According to the more recent classification, the phylum Rhodophyta is divided into two subphyla, Cyanidiophytina and Rhodophytina (Yoon et al., 2006). The former includes unicellular red microalgae living in extreme environments, such as Cyanidioschyzon merolae or Galdieria sulphuraria. Rhodophytina is, instead, divided into six classes, three of them including microalgae: Porphyridiophyceae, Rhodellophyceae, and Stylonematophyceae.

Red algae present chlorophyll a (Chl a) (Gaignard et al., 2019; Gantt et al., 2003) and β‐carotene as the major carotenoid (Schubert et al., 2006). Differently from other eukaryotes, red algae still present phycobilisomes as antenna proteins connected to PSII (Gantt et al., 2003; Marquardt & Rhiel, 1997; Wolfe et al., 1994). Like other eukaryotes, however, red algae also show transmembrane antennas LHC proteins, called LHCR, associated with Photosystem I (PSI) (Bhattacharya et al., 2013; Brawley et al., 2017; Neilson & Durnford, 2010). Even though structural biology allows obtaining high‐resolution structural models and new information on the composition of photosynthetic complexes (Antoshvili et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2020; Pi et al., 2018), the knowledge concerning the in vivo regulation of photosynthesis in red algae is still limited (Eggert et al., 2007; Kowalczyk et al., 2013; Krupnik et al., 2013; Magdaong & Blankenship, 2018).

To increase available information on the biodiversity of photosynthetic organisms and, in particular, of the red lineage, we investigated a recently identified unicellular mesophilic red alga Dixoniella giordanoi (Sciuto et al., 2021) belonging to the Rhodellophyceae. We assessed the response of its photosynthetic apparatus to illumination dynamics with different timescales, investigating its acclimation to different light intensities as well as the capacity of activating NPQ response, xanthophyll cycle, and effective cyclic electron transport.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Culture conditions

Dixoniella giordanoi was isolated from Adriatic Sea samples and identified as a new species of the genus Dixoniella (Sciuto et al., 2021). Here it was grown in sterile‐filtered f/2 medium (Guillard & Ryther, 1962), using sea salts 32 g/L from SIGMA, 40 mM Tris HCl pH 8, SIGMA Guillard's (f/2) marine water enrichment solution ×1. Growth experiments were performed in Erlenmeyer flasks with orbital shaking, starting from a preculture at exponential phase grown at 100 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 illuminated with white LED lamps. The preculture was diluted to a final OD750 equal to 0.2, corresponding to approximately 0.9 × 106 cells/mL in a final volume of 30 mL. OD was measured using 1 cm length cuvettes. Constant illumination of 20, 100, and 400 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 was provided with white LED lamps. The temperature was kept at 22°C ± 1°C in a growth chamber. Algal growth was maintained for 4 days and daily monitored by cell counting. Maximal growth rates (expressed as day−1) were calculated as the slope of the exponential phase of growth curves. For preliminary transmission electron microscope observations and Western blot analysis, algae were grown using f/2 medium enriched with nitrogen, phosphate and iron sources (0.75 g/L NaNO3, 0.05 g/L NaH2PO4, and 0.0063 g/L FeCl3 · 6H2O final concentrations), in 5 cm diameter Drechsel's bottles with a 250 mL working volume and bubbling of air enriched with 5% CO2.

2.2. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

Cells were collected by centrifugation (10 min, 17,000g) and fixed overnight at 4°C in 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 6.9) and post‐fixed for 2 h in 1% osmium tetroxide in the same buffer. The specimens were dehydrated in a graded series of ethyl alcohol and propylene oxide and embedded in Araldite. Ultrathin sections (80–100 nm) were cut with an ultramicrotome (Ultracut; Reichert‐Jung, Vienna, Austria) and stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate; they were then analyzed under a transmission electron microscope (Tecnai G2; FEI, Hillsboro, Oregon) operating at 100 kV.

2.3. Pigment extraction and analysis

Chlorophyll a and total carotenoids were extracted from D. giordanoi cultures after 4 days of growth. Cells were centrifuged for 10 min at 17,000g. Hydrophobic pigments were extracted from centrifuged cells at 4°C using a 1:1 biomass to solvent ratio of 100% N,N′‐dimethylformamide for at least 24 h under dark conditions. Pigment concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically using extinction coefficients (Porra et al., 1989; Wellburn, 1994).

2.4. High‐performance liquid chromatography pigment extraction and analysis

Pigments were extracted from D. giordanoi cultures after 4 days of growth. Cells were harvested by 10 min centrifugation at 10,000g at room temperature, and the supernatant was carefully discarded. Cells were disrupted with a Mini Bead Beater (Biospec Products). Four cycles were performed: rupture at 3500 OPM for 10 s in the presence of glass beads (150–212 mm diameter) and acetone 80% followed by 30 s in ice. The extracted pigments were then centrifuged at 20,000g for 10 min, and the supernatant was kept for the analyses. The content of individual carotenoids was determined using an High‐performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; 1100 series, Agilent), equipped with a reversed‐phase column (5 μm particle size; 25 × 0.4 cm; 250/4 RP 18 Lichrocart) as described in Färber and Jahns (1998). The peaks of each sample were identified through the retention time and absorption spectrum (Jeffrey et al., 1997).

2.5. Phycobiliprotein extraction and analysis

Phycobiliproteins were extracted from D. giordanoi cultures after 4 days of growth. Cells were harvested by 10 min centrifugation at 10,000g at room temperature and washed twice in phosphate buffer (0.01 M Na2HPO4 and 0.15 M NaCl). Cell rupture was performed by three freeze–thaw cycles in liquid nitrogen in dark conditions to avoid phycobiliprotein photodegradation. Disrupted cells were resuspended in phosphate buffer (1:1), and phycobiliprotein concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically as described in Bennett and Bogobad (1973).

2.6. SDS‐PAGE electrophoresis and Western blotting

Samples were collected from cultures in the late exponential phase. Cells were disrupted with a Mini Bead Beater (Biospec Products, Oklahoma) at 3500 rpm for 20 s in the presence of glass beads (150–212 mm diameter), B1 buffer (400 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, and 20 mM Tricine–KOH, pH 7.8), 0.5% milk powder, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DNP‐e‐amino‐n‐caproic acid, and 1 mM benzamidine. The ruptured cells were then solubilized in a buffer (×3) contained 30% glycerol, 125 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 0.1 M dithiothreitol, and 9% SDS at RT for 20 min. SDS‐PAGE analysis was performed with a Tris‐glycine buffer system as previously described (Laemmli, 1970) with acrylamide at a final concentration of 12%. Western blot analysis was performed by transferring the proteins to nitrocellulose (Bio Trace, Pall Corporation, Auckland, New Zealand) and detecting them with alkaline phosphatase‐conjugated antibodies. The antibodies recognized the PSI subunits PsaA and PsaD (Agrisera), D2, LHCX1, VCP, and LHCII proteins (antibodies produced by immunizing New Zealand rabbits with purified spinach protein [D2, LHCII] or recombinant N. gaditana proteins [VCP and LHCX1]; Meneghesso et al., 2016).

2.7. In vivo monitoring of photosynthetic parameters

Chlorophyll fluorescence was determined in vivo using Dual PAM 100 from Waltz. The parameters Fv/Fm, NPQ, and Y(II) were estimated using a light curve protocol, where the cells were stepwise exposed to increasing light intensity every 1 min, from 0 to 2006 μmol of photons m−2 s−1, after 20 min of dark adaptation. Fv/Fm, NPQ, and Y(II) were calculated as (Fm − F0)/F0, (Fm − Fm′)/Fm′, and (Fm′ − F)/Fm′, respectively (Walz, 2006). Far‐red light was switched on during the measurements unless otherwise stated. When actinic light was set off, NPQ was calculated only by a series of saturating pulses (6000 μmol of photons m−2 s−1, 600 ms) every 1 min. NPQ was also estimated by incubating cells with nigericin (10 μM) for 10 min before the measure. The PSII antenna size was measured according to the fluorescence induction kinetics using a JTS‐10 spectrophotometer in the fluorescence mode. Two milliliters of samples with a final concentration of 5 × 106 cell/mL were incubated with DCMU (3,4‐dichlorophenyl‐1,1‐dimethylurea, 10 μM) for 10 min after 20 min of dark adaptation. The induction kinetics was measured upon excitation with 80 or 150 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 of actinic light at 630 nm. In the presence of this inhibitor, an average of 1 photon per PSII center is absorbed at time t, corresponding to 2/3 of the fluorescence increase. This parameter was estimated to evaluate the number of absorbed photons by photosystems II, i.e. the antenna size. The electron flows were estimated, measuring P700 absorption at 705 nm in intact cells. The analysis was carried out exposing cells (at ~5 × 106 cells/mL) to saturating actinic light (2050 μmol of photons m−2 s−1, 630 nm) for 15 s to maximize P700 oxidation and reach a steady state. P700 + re‐reduction in the dark kinetics were then monitored after the light was switched off. The total electron flow (TEF) was estimated measuring the P700 + re‐reduction rates in untreated cells (Meneghesso et al., 2016; Simionato et al., 2013). The same procedure was repeated in samples treated with DCMU (10–80 μM) to evaluate the contribution of cyclic electron flow (CEF) and with DCMU in combination with DBMIB (dibromothymoquinone, 100–300 μM). In all cases, re‐reduction kinetics of P700 + were quantified as the rate constant 1/τ after fitting with a single exponential. By multiplying these rate constants the fraction of P700 oxidized (which was obtained by comparison with DCMU and DBMIB‐poisoned cells), the number of electrons transferred per unit of time was evaluated.

2.8. Oxygen evolution

The evolution of oxygen through increasing light intensities was measured using the O2k FluoroRespirometer (Oroboros Instruments; Doerrier et al., 2018). The measuring chambers were magnetically stirred at 750 rpm, and the oxygen concentration of the chambers was measured with a frequency of 2 s. The light source was a blue LED (emitting wavelength range 439–457 nm with the peak at 451 nm) attached to the chamber of the instrument (provided by Oroboros Instruments, manufactured by Osram Oslon). The 2 mL chambers were filled with a growth medium containing 5 mM NaHCO3 and let equilibrate to experimental temperature (22°C). Then, a small fraction of the medium was replaced with an aliquot of the cell suspension to reach a final concentration in the chamber of 0.5 × 106 cells/mL. The chambers were then closed, and the oxygen consumption rate at dark was calculated. The light was turned on at 25 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 until stabilization of the oxygen flow (5–10 min). This was done recursively for the following light intensities: 25, 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, 800, 900, and 1000 μmol of photons m−2 s−1. The reported values of oxygen evolution rates at each intensity correspond to the median of 40–50 points in the stable region of oxygen flow minus the oxygen flow at dark (respiration).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Photosynthetic apparatus composition in Dixoniella giordanoi

Dixoniella giordanoi cells highlighted the presence of a single chloroplast characterized by a multilobate shape, occupying the largest part of cell volume, as typically found in red algae (Figure 1A). Within the chloroplasts, the thylakoids are unstacked for the presence of disk‐shaped multiple phycobilisomes, present with an alternated arrangement on the thylakoid membranes (Figure 1B). Starch granules were visible outside of the chloroplast. Indeed, differently from green algae and plants, red algae carbohydrate reserves, called floridean starch, are found in the cytoplasm and not in the organelles (Viola et al., 2001). An eccentric nucleus with associated Golgi dictyosomes was also visible (Figure 1C). The peculiar position of Golgi bodies near the outer membrane of the nuclear envelope is indeed a characteristic feature of only a few red algae genera, like Dixoniella, Glaucosphaera, and Neorhodella (Scott et al., 2011).

FIGURE 1.

Transmission electron microscopy of D. giordanoi cells. (A) Complete view of a cell. Specific features and organelles are marked as n, nucleus; g, Golgi apparatus; ch, chloroplast; st, starch. (B,C) show details of thylakoids and dictyosomes of the Golgi apparatus, respectively. The white arrows indicate phycobilisomes associated with the thylakoids

Western blot analysis performed to evaluate the composition of the photosynthetic apparatus allowed the detection of PsaA and D2 proteins, core subunits of, respectively, PSI and PSII even using antibodies raised against green algae and plants proteins, respectively, confirming the conservation of the sequences of these multiprotein complexes in photosynthetic organisms (Figure 2A). The presence of RuBisCO was also detected, corroborating the high conservation of the protein sequence. The presence of transmembrane antennas LHC protein was also tested using antibodies raised against proteins from highly divergent proteins, namely LHCX1 and VCP antenna from the heterokont Nannochloropsis gaditana and LHCII from plants. In neither case, there was any recognition in D. giordanoi samples confirming that, unlike the core complex of photosystems, antenna complexes show larger variability among the different groups of photosynthetic organisms.

FIGURE 2.

Composition of D. giordanoi photosynthetic apparatus. (A) Western blotting targeting different components of the photosynthetic apparatus from PSII (D2), PSI (PsaA), RuBisCO, and antenna complexes (LHCX1, VCP, and LHCII). Different dilutions of total cell extracts were loaded. The ×1 corresponds to 1 μg of Chl for each D. giordanoi sample, except for the case of PsaA, where 2 μg were loaded. As positive control (C+) total proteins extracted from the moss Physcomitrella patens were loaded for the targeting of D2, PsaA, RuBisCO, and LHCII. Extracts from Nannochloropsis gaditana were used as a positive control for LHCX1 and VCP. The dashed line indicates the removal of a lane not essential for the picture. (B) Absorption spectrum of isolated PBS fraction. Three absorption peaks are identified as phycoerythrin (PE), phycocyanin (PC), and allophycocyanin (APC) from their absorption maximum

Different protocols available in the literature were tested and optimized to isolate a phycobilisome (PBS) enriched soluble fraction from hydrophobic thylakoids. Even though the PBSs were not completely purified, absorption analysis of the soluble protein fraction revealed the presence of three distinct absorption peaks identifiable as typical of phycoerythrin (PE, peak at 562 nm), phycocyanin (PC, 615 nm), and allophycocyanin (APC, 652 nm), respectively (Figure 2B).

3.2. Response of Dixoniella giordanoi to growth under different light conditions

In nature, the light intensity is highly dynamic, with changes that can occur with different kinetics spanning from seconds to weeks. To cope with light variability, photosynthetic organisms evolved multiple regulatory mechanisms with different activation timescales, enabling responses to short‐term and long‐term variations. Here D. giordanoi ability to respond to different illumination was assessed by exposing batch cultures to three light intensities of 20, 100, and 400 μmol of photons m−2 s−1, hereafter called LL, ML, and HL (Low, Medium, and High Light), respectively. Cultures exposed to LL showed the lowest growth rate, equal to 0.22 ± 0.03 day−1, suggesting that this light intensity was limiting (Figure 3A). Indeed, cells exposed to ML showed faster growth (0.46 ± 0.07 day−1). A further four times increase in light intensity yielded a further small increase in growth rate (0.60 ± 0.05 day−1), suggesting that light saturation was reached.

FIGURE 3.

D. giordanoi growth under different light regimes. (A) Growth curve for D. giordanoi cells exposed for 4 days to LL, ML, and HL (20, 100, and 400 μmol of photons m−2 s−1), shown as black squares, red circles, and blue triangles, respectively. The fitting of experimental data is shown as dashed lines. Average ± sd are reported (n > 4). (B) Photosystem II quantum yield quantified from Fv/Fm, of D. giordanoi after 4 days of growth in LL, ML, and HL (black, red, and blue, respectively). a, b, and c indicate differences statistically significant from ML, HL, and LL, respectively (one‐way ANOVA, p < 0.05, n > 4, ±sd). Fv/Fm values after 24 h of dark recovery are represented with grey bars (n = 3, ±sd)

To assess how the photosynthetic apparatus responded to different light intensities, the maximum PSII quantum yield was estimated by Fv/Fm. (Figure 3(B); Murata et al., 2007). PSII quantum yield was 17% and 38% lower in ML and HL compared with LL. If cells were left in the dark for 24 h, the Fv/Fm completely recovered in all cases, suggesting that the lower values were attributable to the photoinhibition of PSII experienced at ML and especially HL that is recovered, allowing enough time for damage repair.

3.3. Acclimation of Dixoniella giordanoi to different illumination

Photosynthetic organisms exposed to different light regimes often respond by modulating the photosynthetic apparatus composition and functionality. Indeed, chlorophyll (Chl) content in D. giordanoi was strongly altered by growth under different illumination regimes. Chl content was higher in LL cells with approximately 40% and 70% lower content in ML and HL, respectively (Table 1). The relative content of carotenoids, on the contrary, increased with the light intensity, as shown by the increase of Carotenoid/Chlorophyll ratio (Car/Chl), suggesting the relatively increased accumulation of these pigments with antioxidant activity. HPLC analysis showed that zeaxanthin and β‐carotene are the main carotenoids in D. giordanoi in all light conditions. The relative content of zeaxanthin was progressively higher in cultures exposed to higher light intensity, while β‐carotene remained stable.

TABLE 1.

Pigment composition of D. giordanoi cells grown under different light regimes

| LL | ML | HL | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chl a content (pg/cell) | 1.01 ± 0.17 a | 0.57 ± 0.13 b | 0.32 ± 0.13 b |

| Car/Chl ratio (pg/pg) | 0.41 ± 0.03 a | 0.61 ± 0.09 b | 0.78 ± 0.08 b |

| Zea/Chl a (mol) | 0.28 ± 0.01 a | 0.43 ± 0.09 b | 0.67 ± 0.14 b |

| Beta/Chl a (mol) | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.10 | 0.29 ± 0.06 |

| Phycocyanin (pg/cell) | 3.11 ± 0.90 a | 0.74 ± 0.25 b | 0.19 ± 0.16 a , b |

| Allophycocyanin (pg/cell) | 0.64 ± 0.35 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | n.d. |

| Phycoerythrin (pg/cell) | 1.37 ± 0.46 a | 0.28 ± 0.11 b | n.d. |

Note: Pigment composition of D. giordanoi cells assessed after 4 days of growth at LL, ML, and HL (20, 100, and 400 μmol of photons m−2 s−1). Chl content per cell, Car/Chl ratio, and phycobiliproteins (phycocyanin, allophycocyanin, and phycoerythrin) content per cell are reported (n = 3). n.d., not detectable for values smaller than 0.05 pg/cell.

indicate statistically differences from ML and LL samples, respectively (one‐way ANOVA, p < 0.05, n = 3, ±sd).

Phycobilisomes (PBS) content was also strongly affected by light intensity, as evidenced by the decrease by 75%–80% in ML cells compared with LL for all three pigments classes: phycocyanin, allophycocyanin, and phycoerythrin. The decrease was even larger in HL cells, which showed a 95% lower content of PBS than LL acclimated cells (Table 1). Taken together, these data indicate that D. giordanoi showed a strong acclimation response with modulation of Chl, carotenoids, and PBS content.

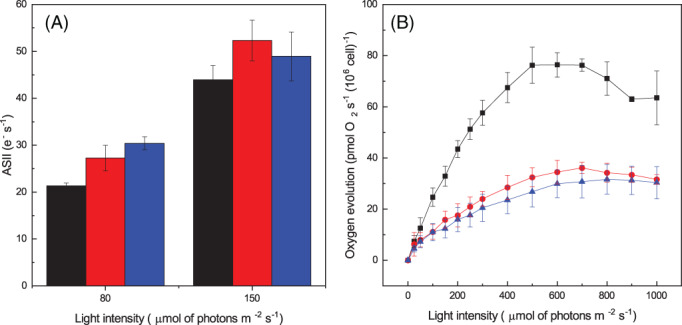

The assessment of functional PSII antenna size using red light at 630 nm, thus poorly absorbed by PBS, showed no major differences between LL, ML, and HL cells, suggesting that LHC content was not significantly regulated (Figure S1; Figure 4A).

FIGURE 4.

Acclimation of D. giordanoi cells to different light illumination. (A) Average PSII antenna size for all samples. Fluorescence measurements were taken with 10 million DCMU‐treated cells in the presence of 80 or 150 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 of actinic light at 630 nm. (B) Oxygen evolution activity of acclimated cells exposed to increasing light intensity. Measurements were taken with 1 million cells. For both the pictures, LL, ML, and HL cells are represented in black, red, and blue, respectively. Data are reported as the average of three biological replica ±sd

Acclimation of photosynthetic activity was further assessed by measuring the oxygen evolution activity in cells exposed to increasing light intensities (Figure 4B). Comparing data measured with an equal cell concentration, with the lowest light intensities, LL cells showed a higher oxygen evolution activity compared with ML and HL, suggesting a higher light harvesting efficiency of these cells. Since blue excitation light is not well absorbed by PBS, the difference is likely underestimated. Oxygen evolution activity increased until reaching saturation at 500 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 and showed a decrease, likely because of photoinhibition, at higher light intensities. ML and HL cells instead reached saturation at higher illumination (7–800 μmol of photons m−2 s−1), and photosynthetic activity did not decrease if the light was further increased.

All cells showed a similar oxygen evolution capacity per Chl amount (Figure S2), suggesting all cells, including HL cells have similar photosynthetic activity. This observation also suggests a similar light harvesting efficiency of Chl binding pigments, consistent with antenna size estimations (Figure S2).

The effect of light acclimation on D. giordanoi cell ultrastructure was assessed using transmission electron microscopy (Figure 5). Thylakoid membrane content and their organization were strongly affected by light intensity. In LL cells, thylakoid membranes were arranged in parallel arrays that included regularly spaced phycobilisomes. In ML cells and, to an even larger extent, in HL cells, thylakoids showed drastically reduced size, occupying a smaller part of cell volume, and were less organized. The number of phycobilisomes was also clearly lower in ML than in LL, and only a few were visible in HL cells. ML and especially HL cells also showed a large part of cell volume occupied by starch reserves. This indicates that an increasing fraction of carbon fixed was converted into reserve carbohydrates suggesting that photosynthetic activity was in excess in comparison to cells' ability to use light energy for growth, with other factors becoming limiting. The comparison of LL cells with ML and HL also showed a progressive reduction of chloroplast lobes volume, while the pyrenoid, containing Rubisco, remained well visible, consistent with a decrease in light harvesting efficiency while maintaining carbon fixation capacity.

FIGURE 5.

Ultrastructure of D. giordanoi cells acclimated to LL, ML, and HL. Panel (A) shows images of the whole cells. Specific features and organelles are marked as p, pyrenoid; ch, chloroplast lobes; st, starch. In (B) details of thylakoid membranes are shown. The white arrows indicate phycobilisomes associated with the thylakoids

3.4. Photosynthesis regulatory mechanisms in Dixoniella giordanoi

Photosynthetic organisms modulate not only the composition but also the activity of the photosynthetic apparatus in response to the illumination regimes. Photochemical capability can be deducted by measuring the effective quantum yield of PSII, Y(II), in cells illuminated with an actinic light intensity of different intensity. As shown in Figure 6, Y(II) progressively decreased with the increase of illumination because of the increased saturation of photochemical capacity. While Y(II) dropped rapidly in cells grown in LL and ML, HL cells maintained photochemical capability under strong illumination and did not show complete saturation even with the strongest illumination tested, showing that D. giordanoi cultures acclimated to high light can exploit a large fraction of absorbed light for photochemistry even under strong illumination.

FIGURE 6.

Photosynthetic regulation of D. giordanoi to different light intensities. Chl fluorescent kinetics were used to calculate PSII quantum yield expressed as Y(II) of acclimated cells and illuminated with a progressively stronger light. LL, ML, and HL cells are represented in black, red, and blue, respectively. During the measurements, the far‐red light was switched on. Data are expressed as the average of three biological replica ±sd

Fluorescence measurements can also be exploited to assess regulatory mechanisms of photosynthesis and, for instance cell ability to activate thermal dissipation of excess energy quantifiable as NPQ. Figure 7(A) shows that D. giordanoi LL cells can activate a measurable NPQ when exposed to illumination of different intensities, but this capacity is lower in ML cells and even further decreased in HL cells. The addition of nigericin, a molecule dissipating membrane ΔpH, does not inhibit NPQ in Dixoniella, suggesting the response is not pH‐dependent (Figure S3).

FIGURE 7.

Non photochemical quenching in D. giordanoi. (A) NPQ was measured exposing acclimated cells to increasing light intensity. During the measurements, the far‐red light was switched on. (B) NPQ of acclimated cells exposed to saturating pulses every minute with actinic light off (far‐red off). For both figures, LL, ML, and HL cells are represented in black, red, and blue, respectively. Data are shown as the average of three biological replica ±sd. (C) Fluorescence traces of LL cells illuminated by a first saturating pulse followed by a second one after 1, 5 10, 20, 40, 60, or 130 min (in dark yellow, magenta, cyan, blue, green, red, and black, respectively). (D) The graph reports the kinetics of NPQ relaxation after one saturating pulse. The fitting of experimental data is shown as a dotted line

Earlier reports showed in other red microalgae that saturating pulses alone could induce a detectable NPQ (Delphin et al., 1998). Indeed, Dixoniella cells simply exposed to a series of saturating pulses with the actinic light off showed the progressive decrease of fluorescence maxima and thus an apparent NPQ, that is not significantly different from the response with the light on (Figure 7(B); Figure S4). A single saturating pulse is indeed sufficient to induce an NPQ value equal to 0.4 (Figure 7B), which takes a significant over 40 min, to be relaxed (Figure 7(C,D)). Overall, the results show that an apparent NPQ is activated in D. giordanoi, but it has some peculiar characteristics different from those normally observed in other algae and plants.

3.5. Regulation of photosynthetic electron transport

Chlorophyll fluorescence signal in intact cells primarily originates from PSII, and thus, the previous analyses are mainly indicative of its activity and regulation. PSI activity can instead be assessed by monitoring the P700 redox state in vivo. To this aim, cells were first exposed to actinic light inducing oxidation of PSI reaction center, generation of P700 + that can be monitored from a differential absorption signal at 705 nm (Simionato et al., 2013). After cells were exposed to illumination for 5 min and reached steady‐state photosynthesis, the light was switched off, allowing for the reduction of P700 +. The kinetics of P700 reduction depends on the rate of electron transports from PSII and cytochrome b6f to PSI and thus allows estimating the total electron flow (TEF), i.e. the sum of all the electron transport processes through PSI. The same measurements were repeated in the presence of inhibitors of PSII and cytochrome b6f (DCMU and DBMIB, respectively) to assess the relative contribution of the linear (LEF) and cyclic (CEF) electron pathways to this total electron transport. As shown in Figure 8(A), PSII inhibition through DCMU strongly reduced electron transport, suggesting that linear electron transport through PSII and PSI is the main pathway in D. giordanoi, as commonly observed in various photosynthetic organisms. Treatment with both DCMU and DBMIB, thus inhibiting both PSII and Cyt b6f, showed a further decrease in P700 reduction kinetics, suggesting that there is a significant contribution of cyclic electron flow around PSI to electron transport (Figure 8A). Similar experiments were repeated for cells acclimated to different conditions to assess the contribution of linear and cyclic electron transport to photosynthesis. Cells exposed to higher light intensities showed a small decrease in linear electron transport capability, but this was at least partially compensated by a relative increase of cyclic electron transport, whose activity was stronger in high light acclimated cells (Figure 8B).

FIGURE 8.

Regulation of photosynthetic electron transport in D. giordanoi. (A) Representative P700 redox kinetics from cells grown in ML. Cells acclimated to 100 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 (ML) were exposed to saturating light intensity (2050 μmol of photons m−2 s−1) for 15 s before the dark recovery kinetics. Reduction of P700 + after switching light off is followed by monitoring differential absorption at 705 nm. Untreated cells, cells treated with DCMU, and cells treated with DCMU+DBMIB are shown as black squares, red circles, and blue triangles, respectively. (B) Rates of cyclic electron flow (CEF, white) and total electron flow (TEF, gray) were evaluated from P700 + reduction kinetics after illumination in LL, ML, and HL acclimated cells. a, b, and c indicate differences statistically significant from ML, HL, and LL, respectively (one‐way ANOVA, p < 0.05, n = 3, ±sd)

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Acclimation to different illumination by modulation of Chl and phycobilisomes content

Photosynthesis involves a complex set of redox reactions occurring in an oxygen‐rich environment that are prone to the generation of reactive species. Many environmental parameters like temperature, irradiance, CO2, and nutrients availability strongly influence photosynthesis requiring a continuous modulation. To thrive in such a dynamic and complex environment, photosynthetic organisms evolved multiple regulatory mechanisms to maintain photosynthetic efficiency while also protecting from the danger of over‐excitation and over‐reduction. Functional genomic studies with model organisms, Arabidopsis thaliana and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii in particular, allowed isolation and characterization of specific mutants resulting in the identification of several genes involved in the regulation of photosynthesis (Eberhard et al., 2008; Li et al., 2009). Mutant generation can, however, also drive to pleiotropic or compensatory effects that may impair a full understanding of biological function. A clear example can be found in the case of cyclic electron transport that depends on multiple mechanisms with significant functional overlap and where single mutants generally have mild phenotypes, leading to an underestimation of their biological relevance. On the contrary, when multiple mutations are combined, phenotypes are much more severe, showing how regulation of electron transport is indeed essential for photosynthesis (Munekage et al., 2004; Storti et al., 2020).

While all photosynthetic organisms present several regulatory mechanisms modulating activity, they are not all conserved in all species. Exploring biological diversity is thus a powerful approach to identify organisms showing specific combinations of regulatory mechanisms or unexpected features (Berne et al., 2018), complementing functional genetic studies. Algae with their large biodiversity are particularly interesting in this context since they are a source of variability that can be exploited for the understanding of the distribution of regulatory mechanisms (Shimakawa et al., 2018), motivating the analysis of under‐investigated groups like the mesophilic red algae studied here.

D. giordanoi cultures under different light intensities respond to environmental conditions through the reorganization of the photosynthetic apparatus and the modulation of its photosynthetic efficiency (Figure 3B). D. giordanoi cells cultivated under high light intensity show a decrease in the cell Chl content and a reduction of the number of thylakoid membranes (Table 1; Figure 4), a commonly observed response (Falkowski & LaRoche, 1991; Walters, 2005). D. giordanoi also shows a strong modulation of the content of PBS that in HL acclimated cells decrease by 95% and become barely detectable (Table 1; Figure 5). Such modulation is much more extreme of what was observed for LHC antennas both in plants and algae that even upon exposure to extreme illumination retain a relatively large antenna system (>50%; Ballottari et al., 2007; Bonente et al., 2012; Meneghesso et al., 2016). The light‐harvesting phycobilisomes are important to increase light absorption under low light intensities and, because of their presence, red algae can efficiently harvest radiation between 490 and 650 nm. This ability represents a significant competitive advantage in environments characterized by low sunlight availability, such as deep waters (Larkum, 2016). On the other hand, in case of exposition to strong illumination, the presence of PBS becomes detrimental, pushing D. giordanoi cells to almost remove the PBS antenna system completely.

Red algae antenna system also includes transmembrane LHC, as in other eukaryotes. The functional analysis of the antenna size (Figure 4A) and the oxygen evolution activity normalized per Chl content (Figure S2) using wavelengths poorly absorbed by PBS suggest that the LHC content is instead not significantly modulated between LL, ML, and HL cells. This suggests that acclimation response is dominated by two main responses: the modulation of the overall number of photosynthetic complexes and thus the Chl content per cell the regulation of PBS accumulation, while the LHC/reaction center ratio remains rather constant.

4.2. Dixoniella giordanoi activates a peculiar fluorescence quenching as other unicellular red algae

NPQ consists of the thermal dissipation of excess energy and it is a regulatory mechanism widespread in photosynthetic organisms. Plants and many species of algae can activate NPQ thanks to specific proteins, PSBS or LHCX (Li et al., 2000; Peers et al., 2009). An NPQ mechanism with different properties is present in cyanobacteria as well, although it depends on the presence of another protein, OCP (Kirilovsky & Kerfeld, 2016). No gene encoding for these proteins has been found in red microalgae genomes sequenced so far, thus questioning the presence of an NPQ response in these organisms.

Here we show that it is possible to observe a fluorescence quenching in D. giordanoi (Figure 7A), but with peculiar properties compared with what is observed in plants, other eukaryotic algae, or even cyanobacteria. This response is detectable in D. giordanoi independently from the presence of actinic light and it is induced by the simple application of saturating flashes during the measurement (Figure 7B). A similar phenomenon was previously observed in other red algal species (Delphin et al., 1998), suggesting this is a specific feature of at least multiple species of this phylogenetic group.

The effect of the inhibitor nigericin suggests this NPQ is not dependent on the generation of a ΔpH (Figure S3). While inhibitors' activity with unknown species must be taken with caution, this hypothesis is fully consistent with the observation that quenching induced by a single saturation pulse takes at least 40 min to relax (Figure 7D). The metabolic effect of a single saturation pulse (6000 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 for 600 ms) is expected to be negligible but, even if this is not the case, any eventual ΔpH generated should be fast consumed and cannot last for several minutes. On the contrary, the long resilience of this effect must be attributed to some signaling and regulatory phenomena activated by light but independent from the metabolic effect.

Mechanistically, one possible explanation for this quenching would be the functional disconnection of some PBS from the PSII, which would cause a reduction in absorption and thus a potential decrease in fluorescence emission signal. A light‐induced dissociation of PBS from PSII has been observed in the red alga Porphyridium cruentum by single‐molecule spectroscopy (Liu et al., 2008) and, indeed, PBS mobility has been suggested to be a typical feature of mesophilic red algae, differently from extremophiles (Krupnik et al., 2013). This hypothesis would be consistent with the observation that the quenching response is smaller in HL cells, where PBS content is also reduced.

Alternative hypotheses such as an NPQ activated in the reaction center, as suggested for the extremophilic red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae (Krupnik et al., 2013), or the modulation of excitation energy spillover between photosystems (Kowalczyk et al., 2013) are, however, possible.

4.3. Dixoniella giordanoi accumulates zeaxanthin under strong illumination without a xanthophyll cycle

D. giordanoi, like other red algae, accumulates zeaxanthin together with β‐carotene (Table 1—Schubert et al., 2006; Serive et al., 2017). However, there are no other detectable xanthophylls, and violaxanthin and antheraxanthin are missing, suggesting the absence of a xanthophyll cycle. This is consistent with findings from other red algae (Marquardt, 1998; Schubert et al., 2006; Serive et al., 2017) and with the available knowledge on red algae genomes that do not contain the genes coding for the enzymes involved in the xanthophyll cycle, violaxanthin de‐epoxidase (VDE) and zeaxanthin epoxidase (ZE) (Bhattacharya et al., 2013; Coesel et al., 2008; Nozaki et al., 2007; Weber et al., 2004). Functional ZE genes have been identified in Compsopogon coeruleus, Adagascaria erythrocladioides, and Calliarthron tuberculosum, but they are all red seaweeds and the corresponding gene was never identified in unicellular organisms. Furthermore, these red algal ZE introduces only a single epoxy group into zeaxanthin, yielding antheraxanthin instead of violaxanthin (Dautermann & Lohr, 2017).

While the xanthophyll cycle is absent in D. giordanoi, data from pigment composition of cells grown under different illumination show that zeaxanthin is specifically over‐accumulated in response to strong illumination, while β‐carotene content remained stable (Table 1). Since the proteins potentially binding these carotenoids, LHC, are not increased in HL cells, these additional zeaxanthin molecules are likely found free in the thylakoid membranes. The accumulated zeaxanthin likely contributes to protection from an excess illumination in D. giordanoi cells acclimated to HL, similarly to what was observed in plants where zeaxanthin free in the thylakoid membranes is acting as an antioxidant, scavenging ROS (Havaux et al., 2007).

The xanthophyll cycle enables the modulation of zeaxanthin accumulation within minutes depending on illumination conditions. While D. giordanoi can still modulate the accumulation of zeaxanthin, the kinetics of synthesis/degradation is much slower. If cells acclimated to HL are exposed back to lower illumination it can be expected that they will retain the zeaxanthin, negatively impacting the light use efficiency. While the accumulation of zeaxanthin likely contributes to the protection from an excess of illumination in D. giordanoi, the absence of a xanthophyll cycle can represent a disadvantage when growing conditions are dynamic, impairing its fast synthesis and degradation when light intensity changes. At least in plants, it has been shown that this capacity for fast modulation of xanthophyll composition has a strong impact on photosynthetic productivity in a variable environment (Kromdijk et al., 2016).

4.4. Cyclic electron flow in Dixoniella giordanoi is increased under strong illumination

D. giordanoi cells show a significant capability for cyclic electron flow, which is also increased in cells acclimated to HL (Figure 8). This suggests that modulation of photosynthetic electron transport is playing a role in the D. giordanoi response to strong illumination. In plants, cyclic electron flow is particularly important to protect PSI from over‐reduction (Tiwari et al., 2016), while NPQ and xanthophyll cycle are more important for limiting damage from over‐excitation to PSII (Peers et al., 2009; Tian et al., 2019). D. giordanoi cells show signs of PSII photoinhibition, as evidenced by the lower Fv/Fm (Figure 3B) if exposed to high or even intermediate light intensity (HL/ML). Despite this damage, however, ML and HL cells are still growing much faster than LL cells that show higher PSII activity. This suggests that PSI in D. giordanoi is well protected, likely with the contribution of cyclic electron transport, and capable of maintaining its activity. The loss of PSII activity is thus at least partially compensated by cyclic around PSI and this is sufficient to support a fast growth (Larosa et al., 2018).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Nicolò Fattore: Performed most experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the article. Simone Savio: Performed most experiments, analyzed the data. Antoni M. Vera‐Vives: Performed oxygen evolution measurements. Mariano Battistuzzi: Performed HPLC analyses. Isabella Moro: Performed TEM analyses. Nicoletta La Rocca: Analyzed the data. Tomas Morosinotto: Designed the research, analyzed the data, wrote the article. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Supporting information

Figure S1 Modulation of the functional antenna size in PSII. Representative traces of the fluorescence kinetics of DCMU‐treated cells in the presence of 80 (A) or 150 (B) μmol of photons m−2 s−1 of actinic light at 630 nm. LL, ML, and HL cells are represented in black, red, and blue, respectively.

Figure S2. Oxygen evolution of acclimated cells. Oxygen evolution activity of acclimated cells exposed to increasing light intensity. Measurements were normalized with the amount of chlorophyll. LL, ML, and HL cells are represented in black, red, and blue, respectively. Data are reported as the average of three biological replica sd.

Figure S3. NPQ measurements of acclimated cells. (A) NPQ of LL, ML, and HL cells exposed to increasing light intensity with far‐red off. (B) The same measurements were taken with nigericin‐treated cells. For both the pictures, LL, ML, and HL cells are represented in black, red, and blue, respectively. Data are reported as the average of three biological replica sd.

Figure S4. Fluorescence traces of D. giordanoi cells. The figure reports the fluorescence traces of acclimated cells exposed to a series of saturating pulses with actinic light off (far‐red off). LL, ML, and HL cells are represented in black, red, and blue, respectively.

Fattore, N. , Savio, S. , Vera‐Vives, A.M. , Battistuzzi, M. , Moro, I. , La Rocca, N. et al. (2021) Acclimation of photosynthetic apparatus in the mesophilic red alga Dixoniella giordanoi . Physiologia Plantarum, 173(3), 805–817. Available from: 10.1111/ppl.13489

Edited by: A. Krieger‐Liszkay

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- Alboresi, A. , Storti, M. & Morosinotto, T. (2019) Balancing protection and efficiency in the regulation of photosynthetic electron transport across plant evolution. The New Phytologist, 221, 105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allahverdiyeva, Y. , Suorsa, M. , Tikkanen, M. & Aro, E.‐M.E.‐M. (2015) Photoprotection of photosystems in fluctuating light intensities. Journal of Experimental Botany, 66, 2427–2436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoshvili, M. , Caspy, I. , Hippler, M. & Nelson, N. (2019) Structure and function of photosystem I in Cyanidioschyzon merolae. Photosynthesis Research, 139, 499–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballottari, M. , Dall'Osto, L. , Morosinotto, T. & Bassi, R. (2007) Contrasting behavior of higher plant photosystem I and II antenna systems during acclimation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 282, 8947–8958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, A. & Bogobad, L. (1973) Complementary chromatic adaptation in a filamentous blue‐green alga. The Journal of Cell Biology, 58, 419–435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berne, N. , Fabryova, T. , Istaz, B. , Cardol, P. & Bailleul, B. (2018) The peculiar NPQ regulation in the stramenopile Phaeomonas sp. challenges the xanthophyll cycle dogma. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta ‐ Bioenergetics, 1859, 491–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, D. , Price, D.C. , Xin Chan, C. , Qiu, H. , Rose, N. , Ball, S. et al. (2013) Genome of the red alga Porphyridium purpureum . Nature Communications, 4, 1941. 10.1038/ncomms2931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley, S. & Hayes, M. (2017) Algal proteins: extraction, application, and challenges concerning production. Foods (Basel, Switzerland), 6, 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonente, G. , Pippa, S. , Castellano, S. , Bassi, R. & Ballottari, M. (2012) Acclimation of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii to different growth irradiances. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 287, 5833–5847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawley, S.H. , Blouin, N.A. , Ficko‐Blean, E. , Wheeler, G.L. , Lohr, M. , Goodson, H.V. et al. (2017) Insights into the red algae and eukaryotic evolution from the genome of Porphyra umbilicalis (Bangiophyceae, Rhodophyta). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114, E6361–E6370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büchel, C. (2015) Evolution and function of light harvesting proteins. Journal of Plant Physiology, 172, 62–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coesel, S. , Oborník, M. , Varela, J. , Falciatore, A. & Bowler, C. (2008) Evolutionary origins and functions of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathway in marine diatoms. PLoS One, 3, e2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dautermann, O. & Lohr, M. (2017) A functional zeaxanthin epoxidase from red algae shedding light on the evolution of light‐harvesting carotenoids and the xanthophyll cycle in photosynthetic eukaryotes. The Plant Journal, 92, 879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delphin, E. , Duval, J.C. , Etienne, A.L. & Kirilovsky, D. (1998) ΔpH‐dependent photosystem II fluorescence quenching induced by saturating, multiturnover pulses in red algae. Plant Physiology, 118, 103–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doerrier, C. , Garcia‐Souza, L.F. , Krumschnabel, G. , Wohlfarter, Y. , Mészáros, A.T. & Gnaiger, E. (2018) High‐resolution FluoRespirometry and OXPHOS protocols for human cells, Permeabilized fibers from small biopsies of muscle, and isolated mitochondria. Methods in Molecular Biology, 1782, 31–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard, S. , Finazzi, G. & Wollman, F.‐A. (2008) The dynamics of photosynthesis. Annual Review of Genetics, 42, 463–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggert, A. , Raimund, S. , Michalik, D. , West, J. & Karsten, U. (2007) Ecophysiological performance of the primitive red alga Dixoniella grisea (Rhodellophyceae) to irradiance, temperature and salinity stress: growth responses and the osmotic role of mannitol. Phycologia, 46, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Falkowski, P.G. & LaRoche, J. (1991) Acclimation to spectral irradiance in algae. Journal of Phycology, 27, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Färber, A. & Jahns, P. (1998) The xanthophyll cycle of higher plants: influence of antenna size and membrane organization. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta ‐ Bioenergetics, 1363, 47–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaignard, C. , Gargouch, N. , Dubessay, P. , Delattre, C. , Pierre, G. , Laroche, C. et al. (2019) New horizons in culture and valorization of red microalgae. Biotechnology Advances, 37, 193–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantt, E. , Grabowski, B. & Cunningham, F.X. (2003) Antenna systems of red algae: phycobilisomes with photosystem ll and chlorophyll complexes with photosystem I. In: Green, B.R. & Parson, W.W. (Eds.) Light harvesting antennas in photosynthesis. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 307–322. [Google Scholar]

- Goss, R. & Lepetit, B. (2015) Biodiversity of NPQ. Journal of Plant Physiology, 172, 13–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillard, R.R.L. & Ryther, J.H. (1962) Studies of marine planktonic diatoms: I. Cyclotella nana hustedt, and Detonula confervacea (cleve) Gran. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 8, 229–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiry, M.D. , Guiry, G. (2021) Algaebase: Listing the World's Algae. Available from: https://www.algaebase.org/ [Accessed: 29 June 2021]

- Havaux, M. , Dall'osto, L. & Bassi, R. (2007) Zeaxanthin has enhanced antioxidant capacity with respect to all other xanthophylls in Arabidopsis leaves and functions independent of binding to PSII antennae. Plant Physiology, 145, 1506–1520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, S.W. , Mantoura, R.F.C. & Wright, S.W. (1997) Phytoplankton pigments in oceanography: guidelines to modern methods. Monographs on oceanographic methodology. Paris: UNESCO Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Keeling, P.J. (2013) The number, speed, and impact of plastid endosymbioses in eukaryotic evolution. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 64, 583–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirilovsky, D. & Kerfeld, C.A. (2016) Cyanobacterial photoprotection by the orange carotenoid protein. Nature Plants, 2, 16180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, N. , Rappaport, F. , Boyen, C. , Wollman, F.‐A. , Collén, J. & Joliot, P. (2013) Photosynthesis in Chondrus crispus: the contribution of energy spill‐over in the regulation of excitonic flux. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1827, 834–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kromdijk, J. , Głowacka, K. , Leonelli, L. , Gabilly, S.T. , Iwai, M. , Niyogi, K.K. et al. (2016) Improving photosynthesis and crop productivity by accelerating recovery from photoprotection. Science, 354, 857–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupnik, T. , Kotabová, E. , van Bezouwen, L.S. , Mazur, R. , Garstka, M. , Nixon, P.J. et al. (2013) A reaction center‐dependent photoprotection mechanism in a highly robust photosystem II from an extremophilic red alga, Cyanidioschyzon merolae . The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 288, 23529–23542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli, U.K. (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature, 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkum, A.W. (2016) Photosynthesis and light harvesting in algae. In: Borowitzka, M.A. , Beardall, J. & Raven, J.A. (Eds.) The physiology of microalgae. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 67–87. [Google Scholar]

- Larosa, V. , Meneghesso, A. , La Rocca, N. , Steinbeck, J. , Hippler, M. , Szabò, I. et al. (2018) Mitochondria affect photosynthetic electron transport and photosensitivity in a green alga. Plant Physiology, 176, 2305–2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.P. , Björkman, O. , Shih, C. , Grossman, A.R. , Rosenquist, M. , Jansson, S. et al. (2000) A pigment‐binding protein essential for regulation of photosynthetic light harvesting. Nature, 403, 391–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z. , Wakao, S. , Fischer, B.B. & Niyogi, K.K. (2009) Sensing and responding to excess light. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 60, 239–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.‐N. , Elmalk, A.T. , Aartsma, T.J. , Thomas, J.‐C. , Lamers, G.E.M. , Zhou, B.‐C. et al. (2008) Light‐induced energetic decoupling as a mechanism for phycobilisome‐related energy dissipation in red algae: a single molecule study. PLoS One, 3, e3134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J. , You, X. , Sun, S. , Wang, X. , Qin, S. & Sui, S.‐F. (2020) Structural basis of energy transfer in Porphyridium purpureum phycobilisome. Nature, 579, 146–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magdaong, N.C.M. & Blankenship, R.E. (2018) Photoprotective, excited‐state quenching mechanisms in diverse photosynthetic organisms. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 293, 5018–5025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, J. (1998) Effects of carotenoid‐depletion on the photosynthetic apparatus of a Galdieria sulphuraria (Rhodophyta) strain that retains its photosynthetic apparatus in the dark. Journal of Plant Physiology, 152, 372–380. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, J. & Rhiel, E. (1997) The membrane‐intrinsic light‐harvesting complex of the red alga Galdieria sulphuraria (formerly Cyanidium caldarium): biochemical and immunochemical characterization. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta ‐ Bioenergetics, 1320, 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Meneghesso, A. , Simionato, D. , Gerotto, C. , La Rocca, N. , Finazzi, G. & Morosinotto, T. (2016) Photoacclimation of photosynthesis in the Eustigmatophycean Nannochloropsis gaditana. Photosynthesis Research, 129, 291–305. 10.1007/s11120-016-0297-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munekage, Y. , Hashimoto, M. , Miyake, C. , Tomizawa, K. , Endo, T. , Tasaka, M. et al. (2004) Cyclic electron flow around photosystem I is essential for photosynthesis. Nature, 429, 579–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata, N. , Takahashi, S. , Nishiyama, Y. & Allakhverdiev, S.I. (2007) Photoinhibition of photosystem II under environmental stress. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1767, 414–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neilson, J.A.D. & Durnford, D.G. (2010) Structural and functional diversification of the light‐harvesting complexes in photosynthetic eukaryotes. Photosynthesis Research, 106, 57–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki, H. , Takano, H. , Misumi, O. , Terasawa, K. , Matsuzaki, M. , Maruyama, S. et al. (2007) A 100%‐complete sequence reveals unusually simple genomic features in the hot‐spring red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae. BMC Biology, 5, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peers, G. , Truong, T.B. , Ostendorf, E. , Busch, A. , Elrad, D. , Grossman, A.R. et al. (2009) An ancient light‐harvesting protein is critical for the regulation of algal photosynthesis. Nature, 462, 518–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi, X. , Tian, L. , Dai, H.E. , Qin, X. , Cheng, L. , Kuang, T. et al. (2018) Unique organization of photosystem I–light‐harvesting supercomplex revealed by cryo‐EM from a red alga. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115, 4423–4428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porra, R.J. , Thompson, W.A. & Kriedemann, P.E. (1989) Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous equations for assaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents: verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta ‐ Bioenergetics, 975, 384–394. [Google Scholar]

- Quaas, T. , Berteotti, S. , Ballottari, M. , Flieger, K. , Bassi, R. , Wilhelm, C. et al. (2014) Non‐photochemical quenching and xanthophyll cycle activities in six green algal species suggest mechanistic differences in the process of excess energy dissipation. Journal of Plant Physiology, 172, 92–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert, N. , García‐Mendoza, E. & Pacheco‐Ruiz, I. (2006) Carotenoid composition of marine red algae. Journal of Phycology, 42, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar]

- Sciuto, K. , Moschin, E. , Fattore, N. , Morosinotto, T. & Moro, I. (2021) Description of Dixoniella giordanoi sp. nov., a new cryptic species inside the primitive genus Dixoniella (Rhodellophyceae, Rhodophyta). Phycologia. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J. , Yang, E.C. , West, J.A. , Yokoyama, A. , Kim, H.J. , Loiseaux De Goër, S. et al. (2011) On the genus Rhodella, the emended orders Dixoniellales and Rhodellales with a new order Glaucosphaerales (Rhodellophyceae, Rhodophyta). Algae, 26, 277–288. [Google Scholar]

- Serive, B. , Nicolau, E. , Bérard, J.B. , Kaas, R. , Pasquet, V. , Picot, L. et al. (2017) Community analysis of pigment patterns from 37 microalgae strains reveals new carotenoids and porphyrins characteristic of distinct strains and taxonomic groups. PLoS One, 12, e0171872. 10.1371/journal.pone.0171872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikanai, T. (2014) Central role of cyclic electron transport around photosystem I in the regulation of photosynthesis. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 26, 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimakawa, G. , Murakami, A. , Niwa, K. , Matsuda, Y. , Wada, A. & Miyake, C. (2018) Comparative analysis of strategies to prepare electron sinks in aquatic photoautotrophs. Photosynthesis Research, 139, 401–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simionato, D. , Block, M.A.M.A. , La Rocca, N. , Jouhet, J. , Maréchal, E. , Finazzi, G. et al. (2013) The response of Nannochloropsis gaditana to nitrogen starvation includes de novo biosynthesis of triacylglycerols, a decrease of chloroplast galactolipids, and reorganization of the photosynthetic apparatus. Eukaryotic Cell, 12, 665–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storti, M. , Segalla, A. , Mellon, M. , Alboresi, A. & Morosinotto, T. (2020) Regulation of electron transport is essential for photosystem I stability and plant growth. The New Phytologist, 228, 1316–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabó, I. , Bergantino, E. & Giacometti, G.M. (2005) Light and oxygenic photosynthesis: energy dissipation as a protection mechanism against photo‐oxidation. EMBO Reports, 6, 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L. , Nawrocki, W.J. , Liu, X. , Polukhina, I. , van Stokkum, I.H.M. & Croce, R. (2019) pH dependence, kinetics and light‐harvesting regulation of nonphotochemical quenching in Chlamydomonas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116, 8320–8325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari A., Mamedov F., Grieco M., Suorsa M., Jajoo A., Styring S. et al. (2016) Photodamage of iron–sulphur clusters in photosystem I induces non‐photochemical energy dissipation. Nature Plants, 2(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viola, R. , Nyvall, P. & Pedersén, M. (2001) The unique features of starch metabolism in red algae. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 268, 1417–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters, R.G. (2005) Towards an understanding of photosynthetic acclimation. Journal of Experimental Botany, 56, 435–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walz, H. (2006) Dual‐PAM‐100 measuring system for simultaneous assessment of P700 and chlorophyll fluorescence. Germany: Heinz Walz GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, A.P.M. , Oesterhelt, C. , Gross, W. , Bräutigam, A. , Imboden, L.A. , Krassovskaya, I. et al. (2004) EST‐analysis of the thermo‐acidophilic red microalga Galdieria sulphuraria reveals potential for lipid a biosynthesis and unveils the pathway of carbon export from rhodoplasts. Plant Molecular Biology, 55, 17–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellburn, A.R. (1994) The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as total carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. Journal of Plant Physiology, 144, 307–313. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, G.R. , Cunningham, F.X. , Durnfordt, D. , Green, B.R. & Gantt, E. (1994) Evidence for a common origin of chloroplasts with light‐harvesting complexes of different pigmentation. Nature, 367, 566–568. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, H.S. , Müller, K.M. , Sheath, R.G. , Ott, F.D. & Bhattacharya, D. (2006) Defining the major lineages of red algae (Rhodophyta). Journal of Phycology, 42, 482–492. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 Modulation of the functional antenna size in PSII. Representative traces of the fluorescence kinetics of DCMU‐treated cells in the presence of 80 (A) or 150 (B) μmol of photons m−2 s−1 of actinic light at 630 nm. LL, ML, and HL cells are represented in black, red, and blue, respectively.

Figure S2. Oxygen evolution of acclimated cells. Oxygen evolution activity of acclimated cells exposed to increasing light intensity. Measurements were normalized with the amount of chlorophyll. LL, ML, and HL cells are represented in black, red, and blue, respectively. Data are reported as the average of three biological replica sd.

Figure S3. NPQ measurements of acclimated cells. (A) NPQ of LL, ML, and HL cells exposed to increasing light intensity with far‐red off. (B) The same measurements were taken with nigericin‐treated cells. For both the pictures, LL, ML, and HL cells are represented in black, red, and blue, respectively. Data are reported as the average of three biological replica sd.

Figure S4. Fluorescence traces of D. giordanoi cells. The figure reports the fluorescence traces of acclimated cells exposed to a series of saturating pulses with actinic light off (far‐red off). LL, ML, and HL cells are represented in black, red, and blue, respectively.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author.