Abstract

A combination of olanzapine and samidorphan was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder. Population pharmacokinetic models for olanzapine and samidorphan were developed using data from 11 clinical studies in healthy subjects or patients with schizophrenia. A 2‐compartment disposition model with first‐order absorption and elimination and a lag time for absorption adequately described concentration‐time profiles of both olanzapine and samidorphan. Age, sex, race, smoking status, and body weight were identified as covariates that impacted the pharmacokinetics of olanzapine. A moderate effect of body weight on samidorphan pharmacokinetics was identified by the model but was not considered clinically meaningful. The effects of food, hepatic or renal impairment, and coadministration with rifampin on the pharmacokinetics of olanzapine and samidorphan, as estimated by the population pharmacokinetic analysis, were consistent with findings from dedicated clinical studies designed to evaluate these specific covariates of interest. Food intake did not have a clinically relevant effect on the pharmacokinetics of olanzapine or samidorphan. Consistent with the known metabolic pathways for olanzapine (primarily via uridine 5′‐diphospho‐glucuronosyltransferase–mediated direct glucuronidation and cytochrome P450 [CYP]‐mediated oxidation) and for samidorphan (predominantly mediated by CYP3A4), coadministration of olanzapine and samidorphan with rifampin, a strong inducer of CYP3A4 and an inducer of uridine 5′‐diphospho‐glucuronosyltransferase enzymes, significantly decreased the systemic exposure of both olanzapine and samidorphan. Severe renal impairment or moderate hepatic impairment resulted in a modest increase in olanzapine and samidorphan exposure.

Keywords: antipsychotic, bipolar I disorder, covariates, opioid antagonist, pharmacokinetics, population pharmacokinetics, schizophrenia

The atypical antipsychotic olanzapine has been in use for the past 20 years and provides an effective treatment option for patients with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 Because the 2 disorders typically require lifelong pharmacologic management, tolerability is of paramount importance. Although olanzapine is considered to be one of the most effective atypical antipsychotic agents, its clinical utility has been limited by weight gain and metabolic effects associated with its use. 8

One potential strategy that has emerged in the management of olanzapine‐associated weight gain involves targeting the endogenous opioid system, which plays a role in weight gain and metabolism. 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 A combination of olanzapine/samidorphan (OLZ/SAM), administered as a single tablet, was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder. Samidorphan is a new molecular entity that acts as an opioid receptor antagonist. 13 , 14 , 15 The addition of samidorphan to olanzapine mitigates olanzapine‐associated weight gain while preserving the antipsychotic efficacy of olanzapine. Data from completed clinical studies indicated that treatment with OLZ/SAM (olanzapine 5‐20 mg in combination with samidorphan 5‐20 mg) and olanzapine (5‐20 mg) resulted in similar improvements in antipsychotic symptoms, 16 , 17 but treatment with OLZ/SAM resulted in significantly less weight gain compared with olanzapine. 16 , 18 , 19

The pharmacokinetics of olanzapine and of samidorphan have been evaluated after oral administration of either compound alone or in combination. 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 Pharmacokinetic parameters of olanzapine and samidorphan when administered in combination as OLZ/SAM 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 were comparable with previously published data when each component was administered alone, 20 , 21 indicating that combining olanzapine with samidorphan does not affect the pharmacokinetics of either component. In addition, food intake did not have a clinically relevant impact on the rate and extent of olanzapine and samidorphan absorption. 24 Consistent with the known metabolic pathways for olanzapine (primarily via uridine 5′‐diphospho‐glucuronosyltransferase–mediated direct glucuronidation and cytochrome P450 [CYP]‐mediated oxidation) and samidorphan (predominantly mediated by CYP3A4), 21 , 29 , 30 systemic exposures to both olanzapine and samidorphan were decreased when OLZ/SAM was coadministered with rifampin, a strong CYP3A4 inducer and an inducer of uridine 5′‐diphospho‐glucuronosyltransferase enzymes. 25 Modest increases in olanzapine and samidorphan exposures were observed in subjects with moderate hepatic impairment or severe renal impairment. 26 The objectives of the current analyses were to develop population pharmacokinetic (PopPK) models for olanzapine and samidorphan that describe plasma concentration vs time profiles of each compound, to identify covariates that contribute to the interindividual variability of olanzapine and samidorphan pharmacokinetic parameters, and to quantify the impact of intrinsic and extrinsic factors on the steady‐state exposures of olanzapine and samidorphan after oral administration of OLZ/SAM.

Methods

Data Sources and Software

Each study contributing to this analysis was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and with the International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. Study protocols, amendments, and informed consent forms were reviewed by each clinical site's independent ethics committee or institutional review board before any subject was enrolled. All subjects provided written informed consent before study participation. The final PopPK models for olanzapine and samidorphan included concentration‐time data from 10 studies of OLZ/SAM (9 phase 1 studies with intense sampling and 1 phase 3 study with sparse sampling) in healthy subjects and in patients with schizophrenia (Table S1). One additional phase 1 study of samidorphan alone was also included in the final PopPK model for samidorphan.

Data were pooled and analyzed by nonlinear mixed‐effects modeling using NONMEM software version 7.3.0 (Farmingdale, New York). Simulated bioequivalence derivations, data presentation, and construction of plots were generated using R version 3.4.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), Excel version 2016 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, Washington), and Phoenix WinNonlin version 8 (Certara, Princeton, New Jersey) software, as appropriate.

Pharmacokinetic Assay

Except for the 1 samidorphan alone study (Table S1), plasma concentrations of olanzapine and samidorphan were analyzed using a validated liquid chromatography system coupled with detection by tandem mass spectrometry method with a lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of 0.250 ng/mL for both olanzapine and samidorphan. 28

For the samidorphan alone study, plasma concentrations of samidorphan were analyzed using a validated liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry method with an LLOQ of 0.250 ng/mL. 22

Model Development

PopPK model development consisted of establishing a base model and a final model for olanzapine and samidorphan separately. Base models were informed by the first 5 completed studies that covered the intended therapeutic doses of OLZ/SAM, obtained from both healthy subjects and patients with schizophrenia. 18 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 28 A previously described PopPK model for olanzapine, a 2‐compartment model with first‐order absorption and elimination, served as the starting point for olanzapine model development. 31 Primary base models for both olanzapine and samidorphan were selected that appropriately describe the plasma concentration vs time profiles of each compound observed in these clinical studies. Structural and variance model parameters were estimated for the base models, which were then expanded and reestimated to include final data from additional studies. 17 , 22 , 26 , 27 , 32 Subjects treated with placebo were not included in the PopPK analysis. Models were fitted via Monte Carlo importance sampling expectation maximization (IMP) assisted by mode a posteriori (IMPMAP) method with the number of random samples per subject used for the expectation step of the estimation (ISAMPLE) of 500. The following were the settings for the instruction for the NONMEM estimation ($EST) steps for both olanzapine and samidorphan:

IMP was selected as the estimation method, as first‐order conditional estimation method with interaction was associated with problems completing the covariance step. Additionally, comparable results were obtained between IMP and IMPMAP. An ISAMPLE = 500 was sufficient to achieve both model optimization and good precision on parameter estimates. M3 methodology 33 was used, allowing for postdose concentrations below the LLOQ to be included in the analysis.

Interindividual variability was incorporated exponentially, as described by the equation: , where Pi is the expected distribution of the individual parameter values, TVp is the typical population value, and η i_P is the random quantity at the individual level. For residual variability, differences between observed data (Yobs ) and model predictions of the dependent variable (Ypred ) were regarded as random quantities and were modeled in terms of epsilon (ε) variables, as follows: , where Yobs,ij is the jth observed value of the dependent variable in the ith individual, Ypred,ij is the jth predicted value of Y in the ith individual, and describes the difference between Yobs,ij and Ypred,ij (with a mean of 0 and variance of 2 ).

Baseline demographic covariates examined in the models included age, sex, race, participant type (ie, healthy volunteer or patient with schizophrenia), body weight, lean body weight, body mass index (BMI), and BMI category (≤25 kg/m2 or >25 kg/m2). The clinical laboratory covariates examined included serum albumin, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and alkaline phosphatase. Total bilirubin, estimated creatinine clearance based on the Cockcroft‐Gault equation, 34 and estimated glomerular filtration rate based on a Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation were also assessed for inclusion. 35 Additional covariates, including formulation (OLZ/SAM bilayer tablet or tablet of olanzapine or samidorphan), renal function (normal; mild, moderate, or severe renal impairment) as measured by creatinine clearance or estimated glomerular filtration rate, and dose were assessed. Furthermore, the effects of coadministration with rifampin 25 or in the presence of moderate hepatic or severe renal impairment, as evaluated in the phase 1 clinical organ impairment studies, were examined. 26 Finally, smoking status (nonsmoker, not recorded, or smoker), food status (fed and fasted), and effects of concomitant CYP inducers or inhibitors of CYP3A4 or CYP1A2 were also evaluated. Covariate selection for inclusion in the model was based on ≥1 of the following criteria: plots of individual estimates (Pi or η i_P ) vs covariates demonstrated a trend, a statistically significant covariate effect as determined by univariate analysis of variance or regression analysis (for categorical and continuous covariates, respectively), a physiological or pharmacological rationale, or information from prior analyses or published sources.

The effects of covariates on model parameters were assessed using a full covariate model, with a backwards elimination approach. A covariate was considered statistically significant when its deletion from the full model increased the objective function value (OFV) <10.83 points (P = .001; degree of freedom = 1). The magnitudes of the effects of significant covariates on associated model parameters were assessed over relevant ranges (eg, minimum and maximum values in the data set); confidence intervals were also calculated.

Continuous covariates (COV) were centered at their typical values (TVCOV ), with TVP expressed as:, where is the estimated parameter representing the typical value of model parameter P when the individual covariate (COVi ) is equal to TVCOV , and θ COV,P is the estimated parameter representing the influence of covariate COV on model parameter P. For categorical covariates, each category must have been represented in at least 10% of the population to be evaluated. Categorical covariates (CAT) were tested and incorporated in the model as a series of index variables taking on values of 0 or 1. Index variables were included in the model according to the following equation:, where is the estimated parameter representing the typical value of model parameter P when the individual categorical covariate index variable (CAT1 i ) is equal to 0, and is the estimated parameter representing the relative influence of categorical covariate index variable on model parameter P when CAT1 i is equal to 1.

Model Evaluation

Model goodness‐of‐fit was assessed by a variety of plots and computed metrics. Goodness‐of‐fit plots of the observed vs model‐predicted concentrations and individual weighted residuals vs population predictions and time since last dose were examined for departures from linearity and homoscedasticity, which were diagnostic of model misspecifications. Change in OFV (ΔOFV) was also evaluated to compare competing hierarchical models. ΔOFV required for a given probability was adjusted with stochastic estimation methods (eg, IMPMAP). Simulations from posterior prediction‐corrected visual predictive checks (pcVPCs) were used to evaluate whether the final models and associated parameters were consistent with observed data.

Model Application

The final PopPK models were applied to predict the impact of significant covariates on steady‐state exposures of olanzapine and samidorphan. For each covariate and reference individual, 500 steady‐state plasma concentration–time profiles were simulated following once‐daily administration of OLZ/SAM 10 mg/10 mg; maximum concentration at steady state (Cmax,ss) and area under the curve during a daily dosing interval (AUCtau) were derived. Each “covariate individual” was compared with the reference individual using a standard analysis of variance bioequivalence approach (Phoenix WinNonlin). Simulated Cmax,ss and AUCtau outputs are presented as forest plots.

Results

The final PopPK model for olanzapine included 601 evaluable subjects contributing 9905 concentration records; a total of 5.6% of the olanzapine concentrations were below the LLOQ. The final PopPK model for samidorphan included 521 subjects with 9321 concentration records; a total of 11.5% of the samidorphan concentrations were below the LLOQ. Summarized demographic and clinical characteristics for the subjects included in the final PopPK models are presented in Table 1. Subjects included in the final olanzapine data set had a median age of 36 years, with a median BMI of 25.5 kg/m2; subjects included in the final samidorphan data set had a median age of 34 years, with a median BMI of 25.6 kg/m2.

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Subjects Included in the Final Population Pharmacokinetic Models

| Covariate | Statistic or Category | Olanzapine | Samidorphan |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects, n | 601 | 521 | |

| Age, y | Median (min‐max) | 36 (18‐73) | 34 (18‐73) |

| Sex, n (%) | Women | 190 (32) | 151 (29) |

| Men | 411 (68) | 370 (71) | |

| Race, n (%) | Native American | 6 (1) | 8 (2) |

| Asian | 3 (0) | 3 (1) | |

| Black | 255 (42) | 258 (50) | |

| Hawaiian | 1 (0) | … | |

| Other | 7 (1) | 6 (1) | |

| White | 329 (55) | 246 (47) | |

| Participant type, n (%) | Healthy | 245 (41) | 295 (57) |

| With schizophrenia | 356 (59) | 226 (43) | |

| Body weight, kg | Median (min‐max) | 76.9 (44.0‐141.0) | 76.4 (46.5‐130.0) |

| Lean body weight, kg | Median (min‐max) | 53.5 (32.0‐81.7) | 53.5 (34.2‐79.8) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | Median (min‐max) | 25.5 (17.9‐39.2) | 25.6 (17.9‐39.1) |

| Albumin, g/dL | Median (min‐max) | 4.4 (3.2‐5.8) | 4.4 (3.2‐5.8) |

| ALP, U/L | Median (min‐max) | 71.0 (0.0‐167.0) | 69.0 (0.0‐167.0) |

| ALT, U/L | Median (min‐max) | 17.0 (5.0‐110.0) | 17.0 (6.0‐110.0) |

| AST, U/L | Median (min‐max) | 18.0 (8.0‐244.0) | 18.0 (8.0‐244.0) |

| Bilirubin, mg/dL | Median (min‐max) | 0.400 (0.006‐2.570) | 0.400 (0.006‐2.570) |

| CrCl, mL/min | Median (min‐max) | 117 (23.0‐260.0) | 117 (23.0‐229.0) |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | Median (min‐max) | 104 (20.0‐187.0) | 105 (20.0‐187.0) |

| Formulation, n (%) | Bilayer tablet a | 388 (65) | 404 (78) |

| Tablet b | 213 (35) | 117 (22) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | Nonsmoker | 142 (24) | 114 (22) |

| Not reported | 173 (29) | 223 (43) | |

| Smoker | 286 (48) | 184 (35) | |

| Hepatic function, n c | Moderate impairment | 10 | 10 |

| Renal function group, CrCl, n (%) d | Normal | 510 (85) | 445 (85) |

| Mild impairment | 78 (13) | 64 (12) | |

| Moderate impairment | 10 (2) | 9 (2) | |

| Severe impairment | 3 (0) | 3 (1) | |

| Renal function group, eGFR, n (%) d | Normal | 454 (76) | 408 (78) |

| Mild impairment | 135 (22) | 102 (20) | |

| Moderate impairment | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | |

| Severe impairment | 10 (2) | 10 (2) | |

| Body mass index category, kg/m2, n (%) | ≤25 | 277 (46) | 236 (45) |

| >25 | 324 (54) | 285 (55) |

ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CrCl, creatinine clearance; eGFR, estimated GFR; GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

Olanzapine and samidorphan coformulated in a single bilayer tablet, with 1 layer containing olanzapine and 1 layer containing samidorphan.

Immediate‐release tablet containing olanzapine alone or samidorphan alone.

Subjects with moderate hepatic impairment were defined as those having a Child‐Pugh score of 7‐9 (class B) at the time of screening.

Renal function impairment classified as follows (units are mL/min or mL/min/1.73 m2 for CrCl and eGFR, respectively): normal, ≥90; mild, 60‐89; moderate, 30‐59; severe, 15‐29; end‐stage renal disease, <15.

The final PopPK models for olanzapine and for samidorphan were both a 2‐compartment disposition model with first‐order absorption and elimination, and a lag time for absorption (Figure S1). The model contained 6 structural parameters (rate of absorption, lag time for absorption, apparent clearance [CL/F], apparent volume of central compartment [Vc/F], apparent volume of peripheral compartment, and intercompartmental clearance [Q/F]). The final olanzapine PopPK model contained 10 covariates, which consisted of 3 continuous covariates (body weight on CL/F, body weight on Vc/F, and age on Vc/F) and 7 categorical covariates (Table 2). The final samidorphan PopPK model contained 8 covariates, which consisted of 2 continuous covariates (body weight on CL/F, body weight on Vc/F) and 6 categorical covariates (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of Categorical Covariate Effects in the Final Population Pharmacokinetic Models

| Parameter | Effect | Change |

|---|---|---|

| Olanzapine | ||

| CL/F | Inducer effect of rifampin (in the presence vs absence of rifampin) in a clinical study 25 | +80% |

| Moderate hepatic impairment vs normal hepatic function in a clinical study 25 | −12% a | |

| Severe renal impairment vs normal renal function in a clinical study 25 | −20% | |

| Smokers vs nonsmokers/not recorded | +30% | |

| Female vs male sex | −14% | |

| Black vs non‐Black | −10% | |

| Bioavailability | Fed vs fasted | −6% |

| Samidorphan | ||

| CL/F | Inducer effect of rifampin (in the presence vs absence of rifampin) in a clinical study 25 | +170% |

| Moderate hepatic impairment vs normal hepatic function in a clinical study 25 | −19% | |

| Severe renal impairment vs normal renal function in a clinical study 25 | −43% | |

| ALAG | Difference for study ALK3831‐A305 b | +10‐fold |

| Nonbilayer tablet vs bilayer tablet | +41% | |

| Ka | Fed vs fasted | −90% |

ALAG, absorption lag time; CL/F, apparent clearance; Ka, first‐order rate of absorption.

Effect fixed in the model.

Dose time not recorded in ALK3831‐A305, so imputed dose timing used. Consequently, the change in ALAG for this study in comparison to population ALAG was estimated. ALK3831‐A305 had a 4‐week treatment period, and participants received oral study drug once daily. Pharmacokinetic samples were taken predose on the first day of treatment, and subsequently during weeks 2 and 4 of the treatment period.

Key parameter estimates for the final olanzapine and samidorphan PopPK models are presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively. In the final olanzapine model, several components were fixed rather than estimated (ie, lag time for absorption was fixed at 0.782 hour; interindividual variability for apparent volume of peripheral compartment and Q/F were fixed at 50% to reduce model instability and minimize stochastic noise in OFV). The final olanzapine model contained covariate effects for body weight on CL/F and Vc/F (fixed at theoretical allometric exponents of 0.75 and 1.0, 36 respectively) and for the effect of moderate hepatic impairment on CL/F, which was fixed at a 12% reduction, based on the observed effect in a clinical study. 26 Model estimates of CL/F and Vc/F for olanzapine were 15.5 L/h and 656 L, respectively. The interindividual variability for CL/F and Vc/F was estimated at 43.2% and 35.6%, respectively. In the final samidorphan model, the interindividual variability for Q/F was fixed at 50% to reduce model instability and minimize stochastic noise in OFV. The model contained covariate effects for body weight on CL/F and Vc/F, fixed at theoretical allometric exponents of 0.75 and 1.0, 36 respectively. The model‐derived CL/F and Vc/F for samidorphan were 35.4 L/h and 297 L, respectively, with interindividual variability for CL/F and Vc/F estimated at 29.4% and 23.3%.

Table 3.

Parameters of the Final Olanzapine Population Pharmacokinetic Model

| Parameter (Units) | Estimate | %RSE | 95% CI | CV% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL/F (L/h) | 15.5 | 2.85 | 14.6‐16.4 | … |

| Vc/F (L) | 656 | 2.23 | 627‐685 | … |

| Ka (h) | 0.861 | 5.70 | 0.765‐0.957 | … |

| ALAG (h) a | 0.782 (fixed) | … | … | … |

| Vp/F (L) | 225 | 9.42 | 183‐267 | … |

| Q/F (L/h) | 6.15 | 18.4 | 3.94‐8.36 | … |

| WT on CL/F b | 0.75 (fixed) | … | … | … |

| WT on Vc/F b | 1.0 (fixed) | … | … | … |

| Rifampin inducer effect (in the presence vs absence of rifampin) on CL/F | 1.80 | 4.45 | 1.64‐1.96 | … |

| Smoking (smokers vs nonsmokers) on CL/F | 1.30 | 3.64 | 1.21‐1.39 | … |

| Food (fed vs fasted) on F | 0.943 | 2.26 | 0.901‐0.985 | … |

| Age on Vc/F | 0.356 | 11.8 | 0.273‐0.439 | … |

| Moderate hepatic impairment (moderate hepatic impairment vs normal hepatic function) on CL/F a | 0.875 (fixed) | … | … | … |

| Severe renal impairment (severe renal impairment vs normal renal function) on CL/F | 0.801 | 5.67 | 0.712‐0.890 | … |

| Race (Black vs non‐Black) on CL/F | 1.10 | 3.22 | 1.03‐1.17 | … |

| Sex (women vs men) on CL/F | 0.862 | 3.56 | 0.802‐0.922 | … |

| Interindividual variability | ||||

| CL/F | 0.171 | 10.0 | 0.137‐0.205 | 43.2 |

| Vc/F | 0.127 | 17.5 | 0.084‐0.171 | 35.6 |

| Ka | 0.209 | 50.2 | 0.003‐0.415 | 48.2 |

| ALAG | 0.319 | 9.53 | 0.259‐0.379 | 61.3 |

| VpF | 0.223 fixed | … | … | 50.0 |

| Q/F | 0.223 fixed | … | … | 50.0 |

| Interoccasion variability in Ka | 0.630 | 14.2 | 0.455‐0.805 | 93.7 |

| Residual variability in σ2 prop | 0.0462 | 6.26 | 0.0405‐0.0519 | 21.5 |

σ2, variance of residual error quantity ε; ALAG, absorption lag time; CI, confidence interval; CL/F, apparent clearance; CV, coefficient of variation; F, bioavailability; IIV, interindividual variability; Ka, rate of absorption; Q/F, intercompartmental clearance; RSE, relative standard error; Vc/F, apparent volume of central compartment; Vp/F, apparent volume of peripheral compartment; WT, time‐changing body weight.

Fixed at estimate from previous stable model where effect was reliably estimated.

Fixed at allometric exponent.

Where estimate >0.15, CV calculated as rather than square root of .

Table 4.

Parameters of the Final Samidorphan Population Pharmacokinetic Model

| Parameter (Units) | Estimate | %RSE | 95% CI | CV% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL/F (L/h) | 35.4 | 1.65 | 34.3‐36.5 | … |

| Vc/F (L) | 297 | 1.63 | 288‐306 | … |

| Vp/F (L) | 124 | 8.87 | 102‐146 | … |

| Ka (h) | 6.61 | 14.2 | 4.77‐8.45 | … |

| ALAG (h) | 0.323 | 5.57 | 0.288‐0.358 | … |

| Q/F (L/h) | 12.1 | 7.89 | 10.2‐14.0 | … |

| WT on CL/F a | 0.75 (fixed) | … | … | … |

| WT on Vc/F a | 1.0 (fixed) | … | … | … |

| Rifampin inducer effect (in the presence vs absence of rifampin) on CL/F | 2.70 | 3.06 | 2.54‐2.86 | … |

| Moderate hepatic impairment (moderate hepatic impairment vs normal hepatic function) on CL/F | 0.810 | 9.04 | 0.667‐0.953 | … |

| Severe renal impairment (severe renal impairment vs normal renal function) on CL/F | 0.570 | 5.96 | 0.503‐0.637 | … |

| Food (fed vs fasted) on Ka | 0.107 | 36.9 | 0.0296‐0.184 | … |

| Change in ALAG b , c | 10.1 | 11.0 | 7.92‐12.3 | … |

| Formulation (samidorphan tablet vs OLZ/SAM bilayer tablet) on ALAG | 1.41 | 5.80 | 1.25‐1.57 | … |

| Interindividual variability | ||||

| CL/F | 0.087 | 11.9 | 0.066‐0.107 | 29.4 |

| Vc/F | 0.054 | 19.0 | 0.034‐0.075 | 23.3 |

| Ka | 1.76 | 16.8 | 1.18‐2.34 | 219 |

| ALAG | 0.131 | 24.8 | 0.067‐0.195 | 36.2 |

| Vp/F | 0.681 | 24.5 | 0.354‐1.010 | 98.8 |

| Q/F | 0.223 fixed | … | … | 50.0 |

| Residual variability in σ2 prop | 0.061 | 6.87 | 0.053‐0.069 | 24.7 |

σ2, variance of residual error quantity ε; ALAG, absorption lag time; CI, confidence interval; CL/F, apparent clearance; CV, coefficient of variation; F, bioavailability; IIV, interindividual variability; Ka, rate of absorption; OLZ/SAM, combination of olanzapine and samidorphan; Q/F, intercompartmental clearance; RSE, relative standard error; Vc/F, apparent volume of central compartment; Vp/F, apparent volume of peripheral compartment; WT, time‐changing body weight.

Fixed at allometric exponent.

Fixed at estimate from previous stable model where effect was reliably estimated.

Dose time was not recorded in ALK3831‐A305, so imputed dose timing was used. Consequently, the change in ALAG for this study in comparison to population ALAG was estimated. ALK3831‐A305 had a 4‐week treatment period, and participants received oral study drug once daily. Pharmacokinetic samples were taken before dosing on the first day of treatment and subsequently during weeks 2 and 4 of the treatment period.

Where estimate >0.15, CV calculated as rather than square root of .

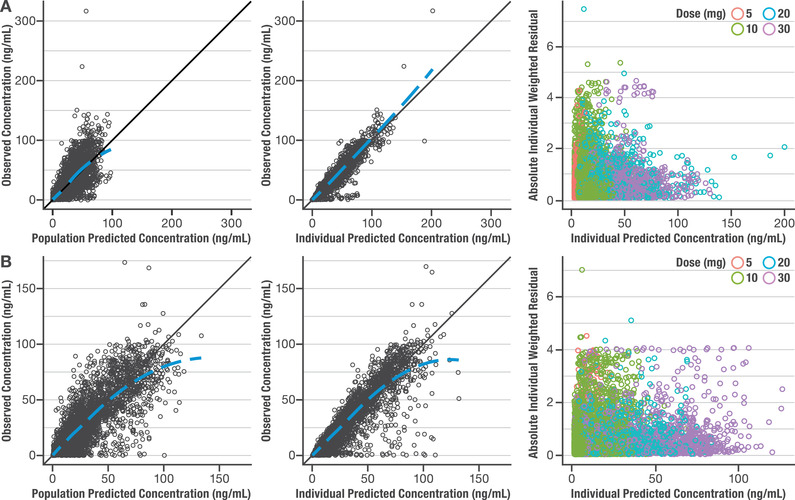

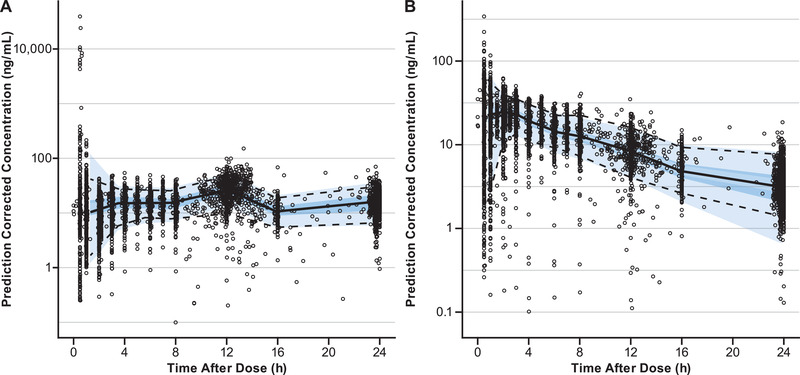

The final models were evaluated by goodness‐of‐fit plots and pcVPC. Goodness‐of‐fit plots of the final olanzapine and samidorphan models (Figure 1A and 1B, respectively) indicated that observed concentrations were well described by the model predictions. Based on stratified versions of these plots, there is no apparent prediction bias due to the study or dose‐effect observed (data not shown). By pcVPC, the majority of observed olanzapine and samidorphan concentrations were contained within the final PopPK model‐predicted 90% prediction intervals (Figure 2A and 2B), indicating the final models adequately described the PopPK of olanzapine and samidorphan. The models described observed olanzapine and samidorphan concentrations well across the doses (5‐30 mg for both olanzapine and samidorphan) and study populations (healthy subjects and patients with schizophrenia) evaluated in clinical studies, indicating that the pharmacokinetics of both olanzapine and samidorphan were linear across the clinical dose range, with no notable difference between healthy subjects and patients with schizophrenia.

Figure 1.

Goodness‐of‐fit and individual weighted residual plots for final population pharmacokinetic models. Observed vs population or individual predicted concentration and individual weighted residual vs individual predicted concentration plots for olanzapine (A) and samidorphan (B).

Figure 2.

Prediction‐corrected visual predictive check of population pharmacokinetic models for olanzapine (A) and samidorphan (B ) over a 24‐hour dosing interval. Open circles indicate observed concentrations; the solid line represents the median observed concentration; dashed lines indicate the 5th and 95th percentiles of observed concentrations. The dark blue–shaded region is the 95% prediction interval of the median predicted concentration; the light blue–shaded regions are the 5th and 95th percentiles of predicted concentrations.

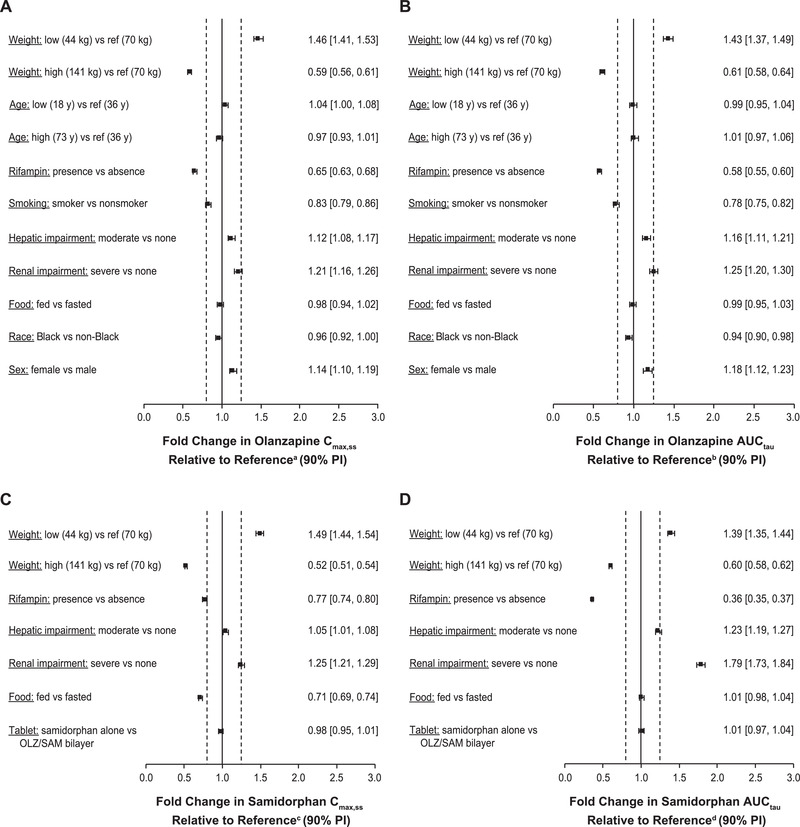

Application of the final PopPK models for the prediction of the effects of significant covariates on steady‐state exposure (Cmax,ss and AUCtau) of olanzapine and samidorphan indicated that olanzapine exposure was affected by age, sex, race, smoking, and body weight (Figure 3A and 3B). Samidorphan exposure was not affected by age, sex, race, or smoking. A modest impact of body weight on samidorphan exposure was predicted (ratio of AUCtau of 1.39 to 0.60 over the range of 44‐141 kg [relative to 70 kg]) but was not considered clinically meaningful (Figure 3C and 3D).

Figure 3.

Population pharmacokinetic model–predicted covariate effects on steady‐state (A) olanzapine Cmax,ss, (B) olanzapine AUCtau, (C) samidorphan Cmax,ss, and (D) samidorphan AUCtau.

aReference Cmax,ss for olanzapine is 31.7 ng/mL.

bReference AUCtau for olanzapine is 635 ng · h/mL.

cReference Cmax,ss for samidorphan is 33.4 ng/mL.

dReference AUCtau for samidorphan is 284 ng · h/mL.

The solid vertical line represents no impact of the covariate using a healthy individual with the following characteristics as a reference subject: age, 36 years; weight, 70 kg; non‐Black, nonsmoking man, with normal hepatic and renal function receiving once‐daily oral OLZ/SAM 10 mg/10 mg in a fasted condition. Dashed vertical lines are at 0.8‐ and 1.25‐fold of this value.

AUCtau, area under the plasma concentration‐time curve over the daily dosing interval at steady state; Cmax,ss, maximum concentration at steady state; PI, prediction interval.

Discussion

In this analysis, data from more than 500 healthy subjects and patients with schizophrenia were used to develop PopPK models for olanzapine and samidorphan that allowed for the determination of population characteristics that influenced the pharmacokinetic parameters of each compound across several doses, including the intended therapeutic dose range of OLZ/SAM. The final PopPK models for olanzapine and samidorphan were both a 2‐compartment disposition model with first‐order absorption and elimination and a lag time for absorption. These models adequately described observed olanzapine and samidorphan concentrations and indicated linear pharmacokinetics for both compounds across the 5‐ to 30‐mg dose range studied. These results are consistent with previously published PopPK analyses for olanzapine 20 , 31 , 37 and phase 1 studies with samidorphan. 21 , 22 The current analysis, conducted using data from clinical studies with the combination product OLZ/SAM, confirmed that the addition of samidorphan did not alter the pharmacokinetics of olanzapine, which supports the clinical findings that samidorphan mitigated olanzapine‐associated weight gain while preserving the antipsychotic efficacy of olanzapine. Generally, the covariates identified here using the final PopPK models (ie, compartmental analyses) were consistent with published data and individual studies evaluating specific covariates of interest (eg, hepatic or renal impairment, food effect). However, as discussed below, the exact magnitudes of the covariate effects based on PopPK analysis were not identical to those published results analyzed by model‐independent computations (ie, non‐compartmental analysis). These differences may be explained by the larger number of subjects in the PopPK analysis (pooled studies with different designs and populations) and associated greater variability than in individual clinical studies. As such, the differences in the exact magnitudes of the covariate effects did not result in any changes in dosing recommendations based on the results from individual studies evaluating specific covariates of interest.

The current PopPK analysis indicated that the pharmacokinetics of olanzapine, including population estimates of CL/F, were affected by age, sex, race, smoking, and body weight, consistent with published data for olanzapine. 20 , 37 , 38 In one published PopPK analysis, olanzapine CL/F was found to be higher in Black subjects (26% higher than non‐Black subjects) and in smokers (55% higher than nonsmokers), and lower in women (38% lower than men). 38 In the current analysis, the final olanzapine PopPK model indicated higher CL/F in Black subjects (10% higher than non‐Black subjects) and smokers (30% higher than nonsmokers, including 29% of subjects with missing smoking status), and a 14% lower CL/F in women than in men (Table 3). However, given the wide therapeutic range of olanzapine plasma concentrations 39 and the wide PopPK variability of olanzapine, dose modifications based on sex, race, and smoking status are generally not needed. 20 , 40 In addition, a meta‐analysis suggested that treatment with olanzapine was efficacious, regardless of a patient's age, sex, race, and smoking habits. 41 Body weight was identified as a significant covariate in the final PopPK model for olanzapine, which is consistent with a published PopPK analysis for olanzapine. 37 However, the magnitude of change in olanzapine exposure due to body weight is predicted to be small (ie, the ratio of Cmax ranged from 0.59 to 1.46 and the ratio of AUCtau ranged from 0.61 to 1.43 over the weight range of 44 to 141 kg, relative to the reference of 70 kg [Figure 3A and 3B]). Again, given the wide therapeutic range of olanzapine plasma concentrations 39 and the wide PopPK variability of olanzapine, these small changes due to body weight are not considered clinically meaningful.

The effects of hepatic and renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of olanzapine, as estimated by the current PopPK analysis, were consistent with findings observed in clinical studies specifically designed to evaluate the effects of these covariates. In a clinical study evaluating the impact of hepatic impairment, the area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to infinity of olanzapine following a single dose of OLZ/SAM was 1.7‐fold higher in subjects with moderate hepatic impairment relative to healthy, age‐ and sex‐matched controls. 26 In the current PopPK analysis, steady‐state AUCtau of olanzapine was predicted to be 1.16‐fold higher in subjects with moderate hepatic impairment compared with subjects with normal hepatic function (Figure 3B), which understated the effect relative to the results observed in the clinical study. In subjects with severe renal impairment, the CL/F of olanzapine decreased 33% relative to healthy, age‐ and sex‐matched controls. 26 The final PopPK model here estimated a 20% decrease in olanzapine CL/F in subjects with severe renal impairment (Table 3). Given that the interindividual variability estimate of CL/F was 43% in the final olanzapine model, the estimated effect based on PopPK analysis was considered comparable to that observed in the clinical study.

The final PopPK model for olanzapine predicted a 1.8‐fold higher olanzapine CL/F in the presence of rifampin (Table 3), which is comparable to the 1.9‐fold higher CL/F reported in a clinical drug‐drug interaction study. 25 Similarly, the final PopPK model for olanzapine estimated a 6% reduction in olanzapine bioavailability for subjects in a fed state vs those who were fasted (Table 3), consistent with the 7% reduction reported in a clinical food‐effect study. 24

Body weight, as with olanzapine, was identified as a significant covariate in the final PopPK model for samidorphan; however, the magnitude of change in samidorphan exposure due to body weight difference is predicted to be up to 49% (ie, the ratio of Cmax ranged from 0.52 to 1.49 and the ratio of AUCtau ranged from 0.60 to 1.39 over the weight range of 44 to 141 kg, relative to the reference of 70 kg [Figure 3C and 3D]) and is not considered clinically meaningful, based on the known exposure‐response relationship for samidorphan on mitigation of weight gain. 16 , 19 In addition, the model estimated the effects of covariates (ie, moderate hepatic impairment, severe renal impairment, inducer effect of rifampin, food effect) that had been assessed in clinical studies. 24 , 25 , 26 In a clinical study evaluating the impact of hepatic impairment, samidorphan area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time 0 to infinity following a single dose of OLZ/SAM was 1.5‐fold higher in subjects with moderate hepatic impairment compared with healthy, age‐ and sex‐matched controls. 26 Consistent with the results observed in the clinical study, the final samidorphan PopPK model predicted a 1.23‐fold higher steady‐state AUCtau of samidorphan following once‐daily administration of OLZ/SAM (Figure 3D). The final samidorphan PopPK model also predicted a 43% reduction in samidorphan CL/F in subjects with severe renal impairment (Table 4), consistent with a 56% reduction observed in the clinical study. 26

The final PopPK model for samidorphan predicted a 2.7‐fold higher samidorphan CL/F in the presence of rifampin (Table 4), which is consistent with a 3.7‐fold higher samidorphan CL/F observed in the clinical study. 25 Furthermore, simulations from the final samidorphan PopPK model estimated a 29% reduction in steady‐state Cmax of samidorphan for subjects in the fed state compared with those who were fasted, which is higher than the 15% reduction reported in a clinical food effect study with OLZ/SAM. 24

At initiation, olanzapine is typically titrated to improve tolerability, and the maintenance dose required is based on the individual patient's clinical response. Patient‐level covariate effects may help predict the final maintenance dose, and interindividual variation may provide another rationale for up‐titration, but both would have minimal impact on current clinical practice. Covariate effects may be more meaningful in helping physicians to anticipate the need for a change in the maintenance dose when the value of a covariate changes for a given patient over time (eg, initiation or discontinuation of smoking, requirement of concomitant medications such as rifampin, or development of renal or hepatic impairment).

In conclusion, PopPK models for olanzapine and samidorphan were developed based on data from phase 1 and phase 3 studies. Covariates that described interindividual variability in pharmacokinetic parameters were identified and incorporated into the models. Age, sex, race, smoking status, and body weight were identified as covariates that impacted the pharmacokinetics of olanzapine, consistent with published data for olanzapine. Pharmacokinetics of samidorphan was not affected by age, sex, race, or smoking status. A modest effect of baseline body weight on samidorphan exposure was identified by the model but was not considered clinically meaningful. Finally, the effects of food, hepatic or renal impairment, and coadministration with rifampin on the pharmacokinetics of olanzapine and samidorphan, as estimated by the PopPK analysis, were consistent with the findings from dedicated phase 1 studies designed to evaluate these specific covariates of interest.

Author Contributions

All authors designed the research. L.S., R.M., and B.M.S. performed the research. R.M. analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the drafting, critical review, and revision of the manuscript. All authors granted approval of the final manuscript for submission.

Conflicts of Interest

L.S. and B.R. are employees of Alkermes, Inc. R.M. and B.M.S. are employees of ICON. All authors met the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors and Good Publication Practice 3 authorship criteria.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Alkermes, Inc. Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Gina Daniel, PhD, and John H. Simmons, MD, of Peloton Advantage, LLC, an OPEN Health company, and funded by Alkermes, Inc.

Data Sharing

The data collected in this study are proprietary to Alkermes, Inc. Alkermes, Inc. is committed to public sharing of data in accordance with applicable regulations and laws.

Supporting information

Supporting information

References

- 1. Zyprexa [package insert] . Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zyprexa [orginial package insert] . Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lopez‐Munoz F, Shen WW, D'Ocon P, Romero A, Alamo C. A history of the pharmacological treatment of bipolar disorder. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(7):2143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(12):1209‐1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple‐treatments meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2013;382(9896):951‐962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yildiz A, Nikodem M, Vieta E, Correll CU, Baldessarini RJ. A network meta‐analysis on comparative efficacy and all‐cause discontinuation of antimanic treatments in acute bipolar mania. Psychol Med. 2015;45(2):299‐317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cipriani A, Barbui C, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: a multiple‐treatments meta‐analysis. Lancet. 2011;378(9799):1306‐1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berkowitz RL, Patel U, Ni Q, Parks JJ, Docherty JP. The impact of the clinical antipsychotic trials of intervention effectiveness (CATIE) on prescribing practices: an analysis of data from a large midwestern state. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(4):498‐503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Czyzyk TA, Romero‐Pico A, Pintar J, et al. Mice lacking delta‐opioid receptors resist the development of diet‐induced obesity. Faseb J. 2012;26(8):3483‐3492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Czyzyk TA, Nogueiras R, Lockwood JF, et al. Kappa‐opioid receptors control the metabolic response to a high‐energy diet in mice. Faseb J. 2010;24(4):1151‐1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tabarin A, Diz‐Chaves Y, Carmona Mdel C, et al. Resistance to diet‐induced obesity in mu‐opioid receptor‐deficient mice: evidence for a “thrifty gene.” Diabetes. 2005;54(12):3510‐3516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gallagher CJ, Gordon CJ, Langefeld CD, et al. Association of the mu‐opioid receptor gene with type 2 diabetes mellitus in an African American population. Mol Genet Metab. 2006;87(1):54‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shram MJ, Silverman B, Ehrich E, Sellers EM, Turncliff R. Use of remifentanil in a novel clinical paradigm to characterize onset and duration of opioid blockade by samidorphan, a potent mu‐receptor antagonist. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(3):242‐249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wentland MP, Lou R, Lu Q, et al. Syntheses of novel high affinity ligands for opioid receptors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19(8):2289‐2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bidlack JM, Knapp BI, Deaver DR, et al. In vitro pharmacological characterization of buprenorphine, samidorphan, and combinations being developed as an adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorder. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2018;367(2):267‐281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martin WF, Correll CU, Weiden PJ, et al. Mitigation of olanzapine‐induced weight gain with samidorphan, an opioid antagonist: a randomized double‐blind phase 2 study in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(6):457‐467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Potkin SG, Kunovac J, Silverman BL, et al. Efficacy and safety of a combination of olanzapine and samidorphan in adult patients with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: outcomes from the randomized, phase 3 ENLIGHTEN‐1 study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(2):19m12769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Silverman BL, Martin W, Memisoglu A, DiPetrillo L, Correll CU, Kane JM. A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled proof of concept study to evaluate samidorphan in the prevention of olanzapine‐induced weight gain in healthy volunteers. Schizophr Res. 2018;195:245‐251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Correll CU, Newcomer JW, Silverman B, et al. Effects of olanzapine combined with samidorphan on weight gain in schizophrenia: a 24‐week phase 3 study. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(12):1168‐1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Callaghan JT, Bergstrom RF, Ptak LR, Olanzapine Beasley CM.. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;37(3):177‐193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Turncliff R, DiPetrillo L, Silverman B, Ehrich E. Single‐ and multiple‐dose pharmacokinetics of samidorphan, a novel opioid antagonist, in healthy volunteers. Clin Ther. 2015;37(2):338‐348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pathak S, Vince B, Kelsh D, et al. Abuse potential of samidorphan: a phase I, oxycodone‐, pentazocine‐, naltrexone‐, and placebo‐controlled study. J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;59(2):218‐228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sun L, McDonnell D, Liu J, von Moltke L. Bioequivalence of olanzapine given in combination with samidorphan as a bilayer tablet (ALKS 3831) compared with olanzapine‐alone tablets: results from a randomized, crossover relative bioavailability study. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2019;8(4):459‐466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sun L, McDonnell D, Liu J, von Moltke L. Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of a combination of olanzapine and samidorphan. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2019;8(4):503‐510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sun L, McDonnell D, Yu M, Kumar V, von Moltke L. A phase I open‐label study to evaluate the effects of rifampin on the pharmacokinetics of olanzapine and samidorphan administered in combination in healthy human subjects. Clin Drug Investig. 2019;39(5):477‐484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sun L, Yagoda S, Du Y, Von Moltke L. Effect of hepatic and renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of olanzapine and samidorphan given in combination as a bilayer tablet. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:2941‐2955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sun L, Yagoda S, Xue H, et al. Combination of olanzapine and samidorphan has no clinically relevant effects on ECG parameters, including the QTc interval: results from a phase 1 QT/QTc study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2020;100:109881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sun L, McDonnell D, von Moltke L. Pharmacokinetics and short‐term safety of ALKS 3831, a fixed‐dose combination of olanzapine and samidorphan, in adult subjects with schizophrenia. Clin Ther. 2018;40(11):1845‐1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kassahun K, Mattiuz E, Nyhart E Jr., et al. Disposition and biotransformation of the antipsychotic agent olanzapine in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25(1):81‐93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Korprasertthaworn P, Polasek TM, Sorich MJ, et al. In vitro characterization of the human liver microsomal kinetics and reaction phenotyping of olanzapine metabolism. Drug Metab Dispos. 2015;43(11):1806‐1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yin A, Shang D, Wen Y, Li L, Zhou T, Lu W. Population pharmacokinetics analysis of olanzapine for Chinese psychotic patients based on clinical therapeutic drug monitoring data with assistance of meta‐analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;72(8):933‐944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sun L, Yagoda S, Yao B, Graham C, von Moltke L. Combination of olanzapine and samidorphan has no clinically significant effect on the pharmacokinetics of lithium or valproate. Clin Drug Investig. 2020; 40(1):55‐64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ahn JE, Karlsson MO, Dunne A, Ludden TM. Likelihood based approaches to handling data below the quantification limit using NONMEM VI. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2008;35(4):401‐421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16(1):31‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(6):461‐470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Anderson BJ, Holford NH. Mechanistic basis of using body size and maturation to predict clearance in humans. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2009;24(1):25‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lobo ED, Robertson‐Plouch C, Quinlan T, Hong Q, Bergstrom RF. Oral olanzapine disposition in adolescents with schizophrenia or bipolar I disorder: a population pharmacokinetic model. Paediatr Drugs. 2010;12(3):201‐211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bigos KL, Pollock BG, Coley KC, et al. Sex, race, and smoking impact olanzapine exposure. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;48(2):157‐165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mauri MC, Paletta S, Di Pace C, et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of atypical antipsychotics: an update. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2018;57(12):1493‐1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Citrome L, Stauffer VL, Chen L, et al. Olanzapine plasma concentrations after treatment with 10, 20, and 40 mg/d in patients with schizophrenia: an analysis of correlations with efficacy, weight gain, and prolactin concentration. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29(3):278‐283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ortega I, Perez‐Ruixo JJ, Stuyckens K, Piotrovsky V, Vermeulen A. Modeling the effectiveness of paliperidone ER and olanzapine in schizophrenia: meta‐analysis of 3 randomized, controlled clinical trials. J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;50(3):293‐310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information