Abstract

Background

An incomplete circle of Willis (CoW) has been associated with a higher risk of stroke and might affect collateral flow in large vessel occlusion (LVO) stroke. We aimed to investigate the distribution of CoW variants in a LVO stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA) cohort and analyze their impact on 3‐month functional outcome.

Methods

CoW anatomy was assessed with time‐of‐flight magnetic resonance angiography (TOF‐MRA) in 193 stroke patients with acute middle cerebral artery (MCA)‐M1‐occlusion receiving endovascular treatment (EVT) and 73 TIA patients without LVO. The main CoW variants were categorized into four vascular models of presumed collateral flow via the CoW.

Results

82.4% (n = 159) of stroke and 72.6% (n = 53) of TIA patients had an incomplete CoW. Most variants affected the posterior circulation (stroke: 77.2%, n = 149; TIA: 58.9%, n = 43; p = 0.004). Initial stroke severity defined by the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) on admission was similar for patients with and without CoW variants. CoW integrity did not differ between groups with favorable (modified Rankin Scale [mRS]): 0–2) and unfavorable (mRS: 3–6) 3‐month outcome. However, we found trends towards a higher mortality in patients with any type of CoW variant (p = 0.08) and a higher frequency of incomplete CoW among patients dying within 3 months after stroke onset (p = 0.119). In a logistic regression analysis adjusted for the potential confounders age, sex and atrial fibrillation, neither the vascular models nor anterior or posterior variants were independently associated with outcome.

Conclusion

Our data provide no evidence for an association of CoW variants with clinical outcome in LVO stroke patients receiving EVT.

Keywords: anatomical variants, circle of Willis, collaterals, stroke, TOF‐MRA

An incomplete circle of Willis (CoW) has been associated with a higher risk of stroke and might affect collateral flow in large vessel occlusion (LVO) stroke. We aimed to investigate the distribution of CoW variants in a LVO stroke and transient ischemic attack cohort and analyze their impact on 3‐month functional outcome

INTRODUCTION

The circle of Willis (CoW) is a polygonal arterial anastomotic system located at the skull base connecting the anterior with the posterior circulation as well as both cerebral hemispheres, thereby ensuring the maintenance of cerebral blood flow (CBF) [1, 2]. Anatomical variants of the CoW are frequent with reported occurrence greater than 50% in the healthy population [2, 3]. Most variants affect the posterior circulation with an average of 40% and more [1, 3, 4]. In patients with an intact CoW and gradual progression of occlusive atherosclerotic cerebrovascular disease, collateral flow via the CoW is provided via the communicating anterior (Acom) and posterior arteries (Pcom) [2]. However, CoW variants may affect the risk of stroke as well as the collateral flow via the CoW during stroke. A study from van Seeters et al. [4] found that in healthy individuals with atherosclerotic disease but no prior vascular events, an incomplete anterior CoW was associated with an increased risk of future anterior circulation stroke with the highest risk in those with combined incomplete posterior and anterior circulation, whereas a posterior circulation variant alone was not. Due to the anastomotic system of an intact CoW, an acute intracranial vessel occlusion might be at least partially compensated by collateral flow via the CoW, but less tolerated within an incomplete CoW. However, so far, there have been no studies analyzing the impact of ipsilateral and contralateral CoW variants on outcome in patients with middle cerebral artery (MCA)‐M1‐occlusion stroke.

In our study, we aimed to assess the frequency and distribution of CoW variants in a LVO stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA) cohort and to evaluate the role of CoW variants for clinical outcome in stroke. Therefore, we analyzed a large homogenous cohort of ischemic stroke patients with MCA‐M1‐occlusion, all subjected to mechanical thrombectomy within 6 h of symptom onset, and categorized them into groups with any, anterior or posterior CoW variants and according to vascular models of presumed collateral flow via the CoW (see Methods section). Demographic and clinical parameters such as stroke severity, etiology and 3‐month modified Rankin Scale (mRS) were compared between groups. Furthermore, we assessed the distribution of CoW variants within 73 TIA patients without intracranial vessel occlusion to evaluate the extent of variants in a cohort with a similar vascular risk profile.

METHODS

Patient data

In this retrospective data analysis, we used encrypted clinical and imaging data from ischemic stroke patients treated with endovascular treatment (EVT) consecutively between January 2012 and August 2017 at the Stroke Center of the University Hospital Berne, Switzerland. Additionally, a cohort of TIA patients (n = 100) presenting between June 2010 and October 2015 at the Stroke Center of the University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland, was analyzed. The study was performed according to the ethical guidelines of the Canton of Berne with approval of the local ethics committee of Berne (KEK: 231/14) and Zurich (KEK: 2014–0304). All stroke patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as primary imaging diagnostic, whereas TIA patients received either computed tomography (CT) or MRI scan with MRI performed within 24 h after onset. Stroke patients were included if acute ischemic stroke due to an MCA‐M1‐occlusion was confirmed by magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), diffusion and time‐of‐flight magnetic resonance angiography (TOF‐MRA) images were complete with sufficient quality, EVT was attempted, and mRS score at 3 months’ follow‐up was available. Stroke patients were excluded if prior territorial infarction or additional intra‐ or extracranial vessel occlusions other than extension of the M1‐occlusion to the internal carotid artery (ICA) could be detected on MRI/MRA. In the TIA cohort, patients were excluded if MRI or MRA was missing or if the final diagnosis was other than TIA. Patient characteristics for stroke patients included demographic information (age, sex, independent prior stroke), vascular risk factors (atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, current smoking, coronary heart disease, peripheral artery disease, prior stroke or TIA), previous medication (antiplatelet therapy, oral anticoagulation, statin or antihypertensive therapy), baseline stroke admission information (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] on admission, blood pressure, levels of glucose, glycosylated hemoglobin [HbA1c], C‐reactive protein [CRP] and international normalized ratio [INR]), collateral status, stroke therapy and etiology. The percentages of missing values were as follows: age (0%), sex (0%), independent prior stroke (10.4%), atrial fibrillation (0.52%), diabetes mellitus (0%), arterial hypertension (0%), dyslipidemia (1%), current smoking (9.3%), coronary heart disease (0%), peripheral artery disease (9.3%), prior stroke or TIA (0%), NIHSS on admission (0%), 3‐month mRS (0%), collateral status (1.6%), stroke etiology according to TOAST (Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment) criteria (0%), onset to groin puncture (2.6%), Thrombolysis In Cerebral Infarction (TICI) scale (0%), general anesthesia (3.1%) and CoW variants and vascular models (0%).

Circle of Willis assessment and vascular models

The anatomy of the CoW was assessed on TOF‐MRA acquired at the time of hospital admission for stroke patients or on a follow‐up MRI within 24 h after symptom onset for TIA patients, respectively. The MRI analyses of stroke patients were performed on 1.5T or 3T MRI systems from one vendor (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) and for TIA patients on 3T MRI systems (Skyra 3T Siemens Healthineers). The MRA of stroke patients consisted of 139 slices obtained with a three‐dimensional (3D) TOF‐MRA technique (flip angle 25 degrees, 1 signal acquired, slice thickness of 0.5 mm). The MRA of TIA patients comprised 200 slices obtained with a 3D TOF‐MRA technique (flip angle 20 degrees, 1 signal acquired, slice thickness of 0.6 mm, and six slaps with an overlap of 19% were used). Images were reconstructed and analyzed in the axial, coronal or sagittal plane with a maximum intensity projection (MIP) or source‐imaging algorithm.

The CoW of stroke patients was assessed by two independent raters experienced in neuroradiologic image analysis (LPW and NL) after prior training of the readout by a board‐certified senior neuroradiologist (SWi). In diverging cases, a consensus decision was reached after a second imaging analysis, if necessary with the assistance of a board‐certified senior neuroradiologist (SWi). The anterior circulation was considered as differing if the Acom or the A1 segment of the anterior cerebral artery (ACA) was hypoplastic (<0.8 mm with rounded values, <0.75 mm in absolute values) and considered as incomplete if the Acom or one A1 segment was undetectable (aplastic). The posterior circulation was categorized as differing if one or both Pcom arteries or P1‐segments of the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) were hypoplastic (<0.8 mm with rounded values, <0.75 mm in absolute values) [3, 4] and classified as incomplete if one or both Pcom arteries or PCAs were undetectable (aplastic) including cases with a full fetal PCA origin.

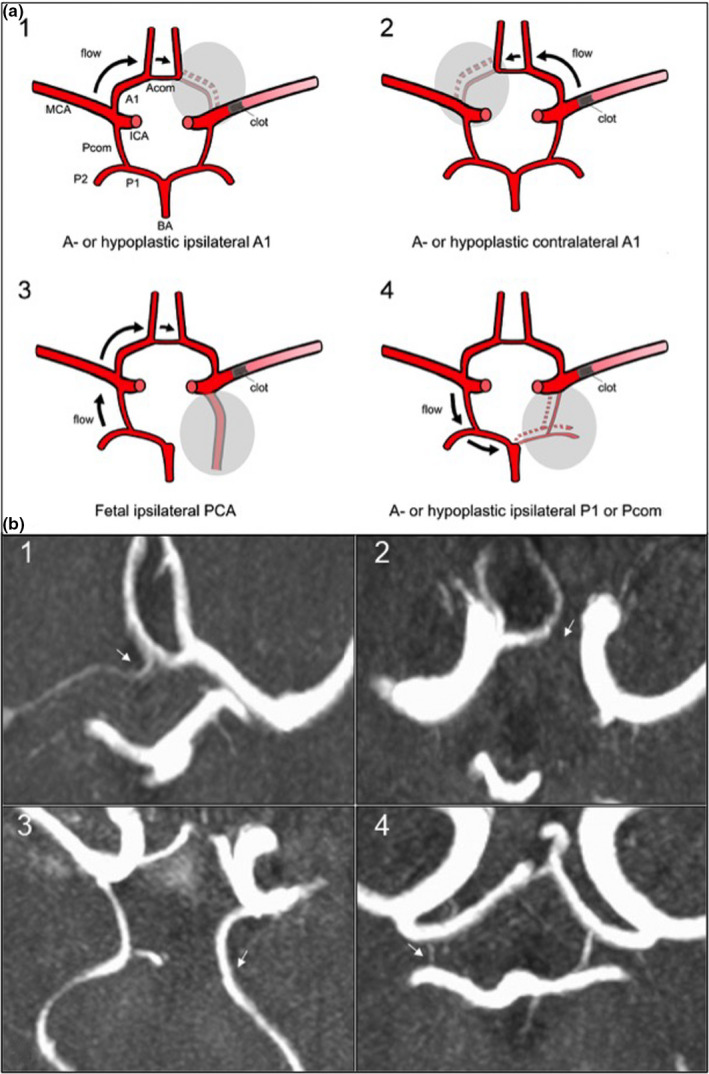

After assessing CoW variants, we categorized the CoW of patients into four vascular models, which we developed according to previously reported hypotheses of collateral flow via the CoW [5, 6]. A schematic visualization of the models and the presumed collateral blood flow dynamics via the CoW is shown in Figure 1a with exemplary findings of these models on TOF‐MRA images demonstrated in Figure 1b. Model 1 has a missing or hypoplastic ACA‐A1‐segment ipsilateral to the side of MCA‐M1‐occlusion with presumed collateral flow via the Acom towards the differing A1‐segment and stroke side thereby likely to provide better collateral flow via leptomeningeal collaterals (LMC) [6, 7]. Model 2 describes a missing or hypoplastic A1‐segment contralateral to stroke and M1‐occlusion with an expected reverse flow via the Acom to the impaired A1‐segment possibly leading to a reduction of collateral flow via the CoW to the stroke side [7]. Model 3 has a fetal PCA ipsilateral to stroke and M1‐occlusion side with a presumed collateral blood flow via the contralateral Pcom, A1 and Acom. Model 4 corresponds to an impaired posterior circulation including a‐ or hypoplastic Pcom or P1‐segments ipsilateral to stroke and M1‐occlusion with a hypothesized worse clinical outcome due to reduced collateral flow from the ipsilateral Pcom to the anterior circulation [7].

FIGURE 1.

Scheme of vascular models of circle of Willis (CoW) variants (a) and visualization in time‐of‐flight magnetic resonance angiography (TOF‐MRA). (b) Axial magnetic resonance images of acute ischemic stroke patients performed on admission showing the CoW in 3D‐multi‐slab TOF‐angiography in the maximum intensity projection (MIP). CoW variant indicated with a white arrow on each image. 1: Hypoplastic A1‐segment ipsilateral to M1‐occlusion on the right side; 2: aplastic A1‐segment contralateral to M1‐occlusion on the right side; 3: full fetal PCA ipsilateral to M1‐occlusion on the left side; 4: hypoplastic Pcom ipsilateral to M1‐occlusion on the right side. Abbreviations: Acom, anterior communicating artery; ICA, internal carotid artery; MCA, middle cerebral artery; PCA, posterior cerebral artery; Pcom, posterior communicating artery

Outcome measures

Outcome measures were assessed for the cohort of stroke patients. The mRS for 3‐month functional impairment after stroke was defined as the primary outcome, whereas mortality defined as death occurring within the first 3 months after stroke onset was set as the secondary outcome. Favorable outcome was defined as mRS 0–2, unfavorable outcome as mRS 3–6.

Statistical analysis

For the descriptive analyses, median and interquartile range (IQR) were used for continuous variables, whereas categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages of total. The Mann−Whitney U test was applied for two‐group exploratory comparisons of continuous variables and the Fisher`s exact test for comparisons of categorical variables. Two different logistic regression models were fitted to model favorable outcome defined as 3‐month mRS 0–2 and to estimate the strength of association of the four vascular models as well as anterior, posterior and all CoW variants on primary outcome with adjustment for clinical confounders (age, sex and atrial fibrillation). In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, we adjusted for the clinically most relevant risk factors, which were significant in the univariate analysis (Table 1) and added sex as a common clinical confounder. NIHSS on admission was excluded from the logistic regression analysis as it could be influenced by collateral flow and CoW variants, thereby potentially mediating outcome. Statistical model I included all vascular models, anterior and posterior variants, and statistical model II only the vascular models simultaneously. An interaction term between the vascular models 1–4 was included in each model, but removed if there was no evidence for an interaction (i.e., the corresponding p value of the interaction term was >0.05). Missing values were considered as missing completely at random, therefore a complete case analysis was conducted.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of stroke patients

| Characteristic | All (n = 193) | Outcome | Mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Favorable a (n = 104) | Unfavorable b (n = 89) | p | Alive (n = 162) | Dead (n = 31) | p | ||

| Demographic factors | |||||||

| Age, median (IQR) | 73.4 (61–82) | 68.7 (57–77) | 79.7 (68–86) | <0.001 | 70.9 (60–79) | 83.4 (79–88) | <0.001 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 118 (61.1) | 62 (59.6) | 56 (62.9) | 0.66 | 100 (61.7) | 18 (58.1) | 0.69 |

| Independent prior stroke, n (%) | 160 (92.5) | 93 (96.9) | 67 (87) | <0.05 | 139 (95.2) | 21 (77.8) | <0.01 |

| Vascular risk factors, n (%) | |||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | 84 (43.8) | 37 (35.9) | 47 (52.8) | <0.05 | 66 (41.0) | 18 (58.1) | 0.11 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 33 (17.1) | 11 (10.6) | 22 (24.7) | <0.05 | 26 (16.1) | 7 (22.6) | 0.43 |

| Arterial hypertension | 128 (66.3) | 58 (55.8) | 70 (78.7) | <0.01 | 106 (65.4) | 22 (71) | 0.68 |

| Dyslipidemia | 112 (58.6) | 64 (61.5) | 48 (55.2) | 0.38 | 100 (62.1) | 12 (40) | <0.05 |

| Current smoking | 40 (22.9) | 27 (27.6) | 13 (16.9) | 0.11 | 37 (24.8) | 3 (11.5) | 0.20 |

| Coronary heart disease | 30 (15.5) | 17 (16.4) | 13 (14.6) | 0.84 | 24 (14.8) | 6 (19.4) | 0.59 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 6 (3.4) | 1 (1) | 5 (6.3) | 0.09 | 4 (2.7) | 2 (7.4) | 0.23 |

| Prior stroke or TIA | 27 (13.9) | 15 (14.2) | 12 (13.5) | 1.00 | 22 (13.6) | 5 (16.1) | 0.78 |

| Previous medication, n (%) | |||||||

| Antiplatelets | 61 (31.6) | 27 (26.0) | 34 (38.2) | 0.09 | 48 (29.6) | 13 (41.9) | 0.21 |

| Oral anticoagulants | 20 (10.4) | 10 (9.6) | 10 (11.2) | 0.81 | 15 (9.3) | 5 (16.1) | 0.33 |

| Statins | 41 (21.4) | 21 (20.4) | 20 (22.5) | 0.73 | 36 (22.4) | 5 (16.1) | 0.63 |

| Antihypertensives | 111 (57.5) | 52 (50.0) | 59 (66.3) | <0.05 | 91 (56.2) | 20 (64.5) | 0.43 |

| Clinical parameters, median (IQR) | |||||||

| NIHSS on admission | 12 (8–17) | 11 (8–15) | 15 (10–19) | 0.001 | 12 (8–16) | 16 (8–20) | <0.05 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 152 (133–168) | 146 (131–161) | 158 (136–173) | <0.05 | 150 (133–167) | 160 (144–175) | 0.1 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 82 (70–95) | 81 (70–92) | 82 (69–96) | 0.76 | 81 (70–93) | 85 (75–100) | 0.25 |

| Onset to groin puncture in min | 217 (163–391) | 210 (160–316) | 240 (165–447) | 0.34 | 212 (163–364) | 245 (159–476) | 0.57 |

| TICI score after EVT c , n (%) | |||||||

| 0 | 10 (5.2) | 2 (1.9) | 8 (9) | <0.05 | 7 (4.3) | 3 (9.7) | 0.076 |

| 1 | 8 (4.2) | 2 (1.9) | 6 (6.7) | 4 (2.5) | 4 (12.9) | ||

| 2a | 24 (12.4) | 13 (12.5) | 11 (12.4) | 21 (13) | 3 (9.7) | ||

| 2b | 68 (35.2) | 34 (32.7) | 34 (38.2) | 58 (35.8) | 10 (32.3) | ||

| 3 | 83 (43) | 53 (51) | 30 (33.7) | 72 (44.4) | 11 (35.5) | ||

| General anesthesia | 88 (46.6) | 45 (45.5) | 41 (46.6) | 0.88 | 71 (45.5) | 15 (48.4) | 0.85 |

| LMC status, n (%) | |||||||

| Weak or no (0) | 20 (10.4) | 9 (8.7) | 11 (12.4) | 0.43 | 18 (11.1) | 2 (6.5) | 0.71 |

| Moderate (1) | 68 (35.2) | 35 (33.7) | 33 (37.1) | 58 (35.8) | 10 (32.3) | ||

| Good (2) | 102 (52.9) | 60 (57.7) | 42 (47.2) | 84 (51.9) | 18 (58.1) | ||

| CoW incomplete/differing, n (%) | 159 (82.4) | 85 (81.7) | 74 (83.2) | 0.85 | 130 (80.3) | 29 (93.6) | 0.119 |

| Vascular models, n (%) | |||||||

| 1 (ipsilateral a‐/hypoplastic A1) | 15 (7.8) | 9 (8.7) | 6 (6.7) | 0.79 | 13 (8) | 2 (6.5) | 1.00 |

| 2 (contralateral a‐/hypoplastic A1) | 12 (6.2) | 7 (6.7) | 5 (5.6) | 1.00 | 10 (6.2) | 2 (6.5) | 1.00 |

| 3a (ipsilateral full fetal PCA) | 11 (5.7) | 8 (7.7) | 3 (3.4) | 0.23 | 9 (5.6) | 2 (6.5) | 0.69 |

| 3b (two‐sided full fetal PCA) | 2 (1) | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 0.50 | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 1.00 |

| 4 (ipsilateral a‐/hypoplastic PCA/Pcom) | 105 (54.4) | 60 (57.7) | 45 (50.6) | 0.39 | 86 (53.1) | 19 (61.3) | 0.44 |

| 4a (ipsilateral hypoplastic PCA/Pcom) | 73 (37.8) | 40 (38.5) | 33 (37.1) | 0.88 | 61 (37.7) | 12 (38.7) | 1.00 |

| 4b (ipsilateral aplastic PCA/Pcom) | 32 (16.6) | 20 (19.2) | 12 (13.5) | 0.33 | 25 (15.4) | 7 (22.6) | 0.31 |

| 4c (two‐sided a‐/hypoplastic PCA/Pcom) | 89 (46.1) | 48 (46.2) | 41 (46.1) | 1.00 | 73 (45.1) | 16 (51.6) | 0.56 |

| 4d (ipsilateral a‐/hypoplastic Pcom) | 95 (49.2) | 55 (52.9) | 40 (44.9) | 0.31 | 78 (48.2) | 17 (54.8) | 0.56 |

Abbreviations: CoW, circle of Willis; DSA, digital subtraction angiography; EVT, endovascular treatment; IQR, interquartile range; LMC, leptomeningeal collateral; mRS, modified Rankin scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; PCA, posterior cerebral artery; Pcom, communicating posterior artery; TIA, transient ischemic attack; TICI, Thrombolysis In Cerebral Infarction. Bold values mark statistically significant values.

(mRS ≤ 2).

(mRS ≥ 3–6).

LMC status assessed during initial DSA; TICI scale: 0, no perfusion; 1, penetration with minimal perfusion; 2a, partial perfusion <2/3 of the entire vascular territory; 2b, complete filling of the expected vascular territory, but with a perceptibly slower filling rate; 3, complete perfusion.

All calculations were performed using STATA 14.1 and R 3.6.0 (R Core Team, 2019). The study was reported according to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for observational studies [8].

RESULTS

Stroke and TIA patient data and baseline characteristics

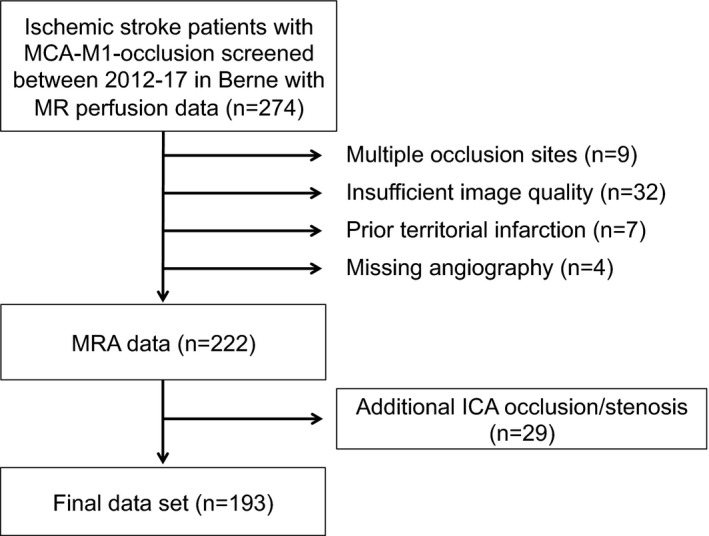

We screened 274 acute ischemic stroke patients with MCA‐M1‐occlusion and included 193 into the analysis (Figure 2). A total of 52 patients were excluded either because of insufficient image quality due to excessive head movement or other imaging artifacts (n = 32), additional LVO other than extension of the occlusion to the ICA (n = 9), prior territorial infarction (n = 7) or missing angiography (n = 4). Furthermore, 29 cases with extra‐ or intracranial ICA‐occlusion as a possible confounder for outcome analyses were excluded, leading to an overall dataset of 193 stroke patients available for the analysis of CoW variants. Additionally, we screened a cohort of 100 patients who presented with suspicion of a TIA. Twenty‐seven cases were excluded due to a final diagnosis other than TIA or missing MRI data, leading to a set of 73 patients diagnosed with a TIA without diffusion restriction or intracranial vessel occlusion on follow‐up MRI.

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart of study population. Abbreviations: ICA, internal carotid artery; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography

As presented in Table 1, the median age of stroke patients was 73.4 (IQR: 61–82) years, 61.1% (n = 118) were females and 92.5% (n = 160) were independent prior to stroke. Among the vascular risk factors, arterial hypertension with 66.3% (n = 128) and dyslipidemia with 58.6% (n = 112) were the most frequent. The median NIHSS on admission was 12 (IQR: 8–17). 48.7% (n = 94) of patients underwent intravenous thrombolysis, all patients were referred to EVT. Most patients (54.4%, n = 105) were assigned to vascular model 4 (ipsilateral a‐ or hypoplastic PCA or Pcom) with 49.2% (n = 95) of all CoW variants being an ipsilateral a‐ or hypoplastic Pcom (see Table 1). In the anterior circulation, an a‐ or hypoplastic A1‐segment (vascular model 1) was observed in 7.8% (n = 15) on the ipsilateral side and in 6.2% (n = 12) on the contralateral side of the M1‐occlusion (Table 1).

Distribution of CoW variants in stroke and TIA patients

Some 82.4% (n = 159) of ischemic stroke patients with MCA‐M1‐occlusion showed a differing or incomplete CoW including a‐ or hypoplastic vessels of the anterior (ACA‐A1 or Acom) or posterior circulation (PCA‐P1 or Pcom) as shown in Table 2. From these, 39.9% (n = 77) had variants of the anterior circulation and 77.2% (n = 149) a differing or incomplete posterior circulation (Table 2). Among anterior CoW variants, a differing Acom was the most frequent finding (n = 59, 30.6% of all CoW variants), whereas a hypoplastic P1 or Pcom was most often observed in posterior CoW variants (n = 114, 59%) (see Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Distribution of circle of Willis variants in stroke and transient ischemic attack patients

| Stroke cohort |

All (n = 193) |

TIA cohort |

All (n = 73) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CoW, n (%) | |||

| Incomplete/differing a | 159 (82.4) | Incomplete/differing a | 53 (72.6) |

| Anterior CoW, n (%) | |||

| A1 or Acom incomplete/differing | 77 (39.9) | A1 or Acom incomplete/differing | 33 (45.2) |

| A1 or Acom hypoplastic | 65 (33.7) | A1 or Acom hypoplastic | 30 (41.1) |

| A1 or Acom aplastic | 15 (7.8) | A1 or Acom aplastic | 3 (4.1) |

| A1‐asymmetry | 26 (13.5) | A1‐asymmetry | 10 (13.7) |

| A1‐asymmetry (ipsilateral) | 15 (7.8) | A1‐asymmetry (ipsilateral) | NA |

| A1 hypoplastic (ipsilateral) | 9 (4.7) | A1 hypoplastic | 8 (11) |

| A1 aplastic (ipsilateral) | 6 (3.1) | A1 aplastic | 2 (2.7) |

| Acom differing | 59 (30.6) | Acom differing | 23 (31.5) |

| Acom hypoplastic | 54 (28.0) | Acom hypoplastic | 22 (30.1) |

| Acom aplastic | 5 (2.6) | Acom aplastic | 1 (1.4) |

| Azygos variant | 2 (1) | Azygos variant | 1 (1.4) |

| Posterior CoW, n (%) | |||

| P1 or Pcom incomplete/differing | 149 (77.2) | P1 or Pcom incomplete/differing | 43 (58.9) |

| P1 or Pcom incomplete/differing (ipsilateral) | 105 (54.4) | P1 or Pcom incomplete/differing (ipsilateral) | NA |

| P1 or Pcom hypoplastic | 114 (59.1) | P1 or Pcom hypoplastic | 32 (43.8) |

| P1 or Pcom hypoplastic (ipsilateral) | 74 (38.3) | P1 or Pcom hypoplastic (ipsilateral) | NA |

| P1 or Pcom aplastic | 55 (28.5) | P1 or Pcom aplastic | 12 (16.4) |

| P1 or Pcom aplastic (ipsilateral) | 31 (16.1) | P1 or Pcom aplastic (ipsilateral) | n.a. |

| P1 or Pcom one‐sided differing | 60 (31.1) | P1 or Pcom one‐sided differing | 29 (39.7) |

| P1 or Pcom two‐sided differing | 89 (46.1) | P1 or Pcom two‐sided differing | 14 (19.2) |

| Pcom differing (ipsilateral) | 95 (49.2) | Pcom differing | 39 (53.4) |

| Pcom hypoplastic (ipsilateral) | 64 (33.2) | Pcom hypoplastic | 28 (38.4) |

| Pcom aplastic (ipsilateral) | 31 (16.1) | Pcom aplastic | 12 (16.4) |

| Full fetal PCA | 21 (10.9) | Full fetal PCA | 4 (5.5) |

| Full fetal PCA (ipsilateral) | 11 (5.7) | Full fetal PCA (ipsilateral) | NA |

| Partial fetal PCA | 54 (28.0) | Partial fetal PCA | 16 (21.9) |

| Partial fetal PCA (ipsilateral) | 38 (19.7) | Partial fetal PCA (ipsilateral) | NA |

Abbreviations: Acom, anterior communicating artery; CoW, circle of Willis; NA, not applicable; PCA, posterior cerebral artery; Pcom, posterior communicating artery; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Including all CoW variants.

In TIA patients without intracranial vessel occlusion, we found a total amount of 72.6% (n = 53) of CoW variants as also presented in Table 2 (vs. 82.4% [n = 159] in stroke patients, p = 0.088). From these, 45.2% (n = 33) were anterior circulation variants (vs. 39.9% [n = 77] in stroke patients, p = 0.486). Posterior circulation variants were detected less frequently in TIA patients (58.9% [n = 43] vs. 77.2% [n = 149] in stroke patients, p = 0.004). A detailed list of the distribution of the different CoW variants of both patient cohorts can be found in Table 2. The median age of TIA patients was 73 years (IQR: 64–78 years, compared to stroke patients, p = 0.582). There were more women in the stroke group (61.1% [n = 118] vs. 39.7% [n = 29] in TIA patients, p = 0.002). When adjusting stroke and TIA patients for sex, we found no evidence for a differing amount of all CoW variants or anterior variants, while the difference in posterior variants between stroke and TIA patients remained (p = 0.0076).

Association of CoW variants with clinical parameters in stroke and TIA patients

When comparing stroke patients with a complete CoW to patients with any CoW variant or only anterior or posterior variants, the median age of all groups with CoW variants was higher compared to the group without variants (normal CoW: 68.7 [IQR: 56–80] years; all CoW variants: 74.5 [IQR: 62–82] years, p = 0.22). Within the group of posterior variants, there was evidence for a higher median age of stroke patients with variants (74.7 [IQR: 64–82] years vs. 67.7 [IQR: 55–79] years) (see Table S1). In TIA patients, we found a median age of 74 years (IQR: 65–80) in patients with any CoW variant compared to 69 years (IQR: 55–77) in patients with a normal CoW (p = 0.19) as shown in Table S1). Regarding stroke severity, there was no evidence for a differing NIHSS on admission between groups with different CoW variants. Furthermore, there was no evidence for a difference between the groups with and without variants for neither the LMC status assessed during the initial digital subtraction angiography (DSA), nor success of recanalization assessed by the TICI scale (Table S1).

Outcome analysis of CoW variants in stroke patients

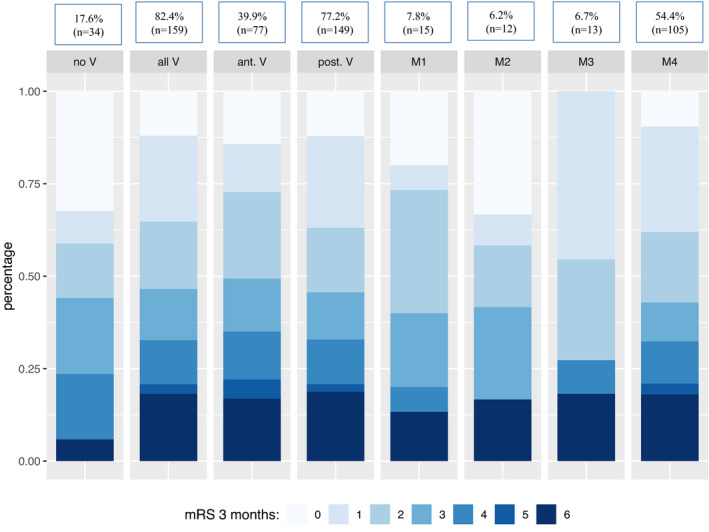

In patients with any CoW variant there was a trend towards a higher mortality compared to patients with an intact CoW (18.2% vs. 5.9%, p = 0.08), in particular in patients with posterior circulation variants (p = 0.058) (see Table S1). When stratifying the group of all CoW variants (n = 159) within the stroke cohort for outcome and mortality, respectively, there was a tendency towards more incomplete CoW among patients dying within 3 months after stroke onset (93.6% [n = 29] vs. 80.3% [n = 130], p = 0.119) (see Table 1). However, there was no evidence for a differing outcome after 3 months. An illustration of the distribution of 3‐month mRS stratified for patients with a complete CoW, all, anterior or posterior variants and the four vascular models is presented in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of 3‐month modified Rankin scale (mRS) among circle of Willis (CoW) variants. No V = no CoW variants, all V = all CoW variants, ant. V = all anterior circulation variants, post. V = all posterior circulation variants, M1 = model 1 (ipsilateral a‐ or hypoplastic A1), M2 = model 2 (contralateral a‐ or hypoplastic A1), M3 = model 3 (ipsilateral fetal posterior cerebral artery), M4 = model 4 (ipsilateral a‐ or hypoplastic P1 or posterior communicating artery)

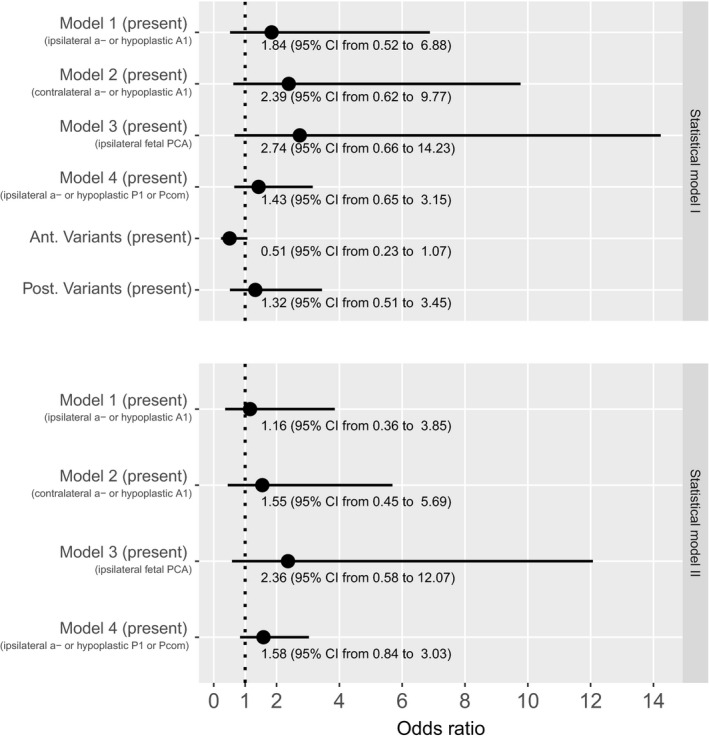

Since we assumed that an imbalance of clinical variables such as slightly older age in patients with CoW variants might affect our outcome comparison, we conducted a logistic regression analysis in order to evaluate the association of CoW variants on favorable clinical outcome adjusted for clinical confounders. When analyzing the four vascular models and also adding anterior and posterior variants as exploratory variables (statistical model I), we did not find enough evidence to claim that either one of the vascular models or the variants had a reliable effect on outcome (the estimated change in odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals are shown in Figure 4). We additionally performed the analysis including only the four vascular models (statistical model II) and again there was no evidence for an association of the included variables with favorable outcome. In both statistical models, there was no evidence for an interaction between the vascular models 1–4.

FIGURE 4.

Estimated changes in odds ratio of favorable outcome and 95% confidence intervals for statistical models I and II. Odds ratios >1 indicate that the association increases the chance for favorable outcome. Abbreviations: Ant., anterior; PCA, posterior cerebral artery; Pcom, posterior communicating artery; Post., posterior

DISCUSSION

CoW variants are frequent and their presence and shape have been associated with ischemic stroke previously [4, 6, 9]. However, it is unknown if CoW variants affect outcome in MCA‐M1‐occlusion stroke after EVT.

Our aim was to assess the frequency and distribution of CoW variants in a MCA‐M1‐occlusion stroke and TIA cohort without intracranial vessel occlusion and to investigate the potential impact of CoW variants on stroke outcome. Our hypothesis was that an acute intracranial vessel occlusion might be partially compensated by collateral flow via the CoW in the setting of a complete CoW, but less tolerated in an incomplete CoW. However, some conditions such as a missing A1‐segment ipsilateral to an acute MCA‐M1‐occlusion (model 1) could be beneficial by providing additional collateral flow via a well‐established Acom and LMC towards the missing A1‐segment and stroke side [6, 7]. This led to the development of four vascular models of presumed flow compensation in cases of MCA‐M1‐occlusion stroke (Figure 1) according to previously described flow dynamics in patients with LVO [5, 6, 7]. We found that a high (82.4%) proportion of patients with MCA‐M1‐occlusion stroke had an incomplete or hypoplastic CoW affecting predominantly the posterior circulation (77.2%), which is in line with previous data [10].

Despite a trend towards a higher mortality in patients with any CoW variant in our study, the presence of any type of CoW variant was not independently associated with 3‐month functional outcome after adjusting for potential clinical confounders, particularly age. Furthermore, none of the vascular models of presumed collateral flow in different conditions of missing CoW segments could be confirmed in our outcome analysis. In line with our results, a recent study analyzing ipsilateral CoW variants in patients with MCA‐ or ICA‐occlusion found no evidence for an effect of these CoW variants on clinical outcome [11]. However, in that analysis, contralateral CoW variants as well as Acom variants were not included [11]. In line with our results, a study by Shaban et al. [12] could not find an association between the presence of a fetal PCA and stroke severity or early outcome in a heterogenic cohort including different stroke etiologies.

Similar to other studies, we found that older age was associated with a higher frequency of CoW variants in patients with stroke [3, 9, 11, 12] which is likely to affect outcome analyses, if not adjusted. Results from a twin study by Forgo et al. [1] suggest that environmental rather than genetic effects determine CoW variants after demonstrating a high rate of discordance of CoW variants in monozygote twins. Another anatomical study demonstrated that some hypoplastic arteries have inward vascular remodeling consistent with atherosclerotic arterial occlusion [13] which might explain to some extent the higher frequency of CoW variants in older individuals.

Except for fewer posterior variants in the TIA cohort, we found no evidence for a difference in frequency and distribution of CoW variants in TIA compared to stroke patients. The difference in posterior variants remained after adjusting both cohorts for sex. Although some imbalance in the rather small sample size of TIA patients might contribute to this finding, we cannot rule out that certain CoW variants, such as posterior variants, render patients more susceptible to MCA‐M1‐occlusion stroke.

The strengths of our study are the clinically well‐characterized patient cohort with a homogenous intracranial vessel status, including only patients with stroke due to MCA‐M1‐occlusion and no additional extra‐ or intracranial vessel stenosis or occlusion. Furthermore, the CoW was assessed by two blinded and independent physicians with neuroradiological expertise trained and supervised by a board‐certified neuroradiologist. Additionally, we analyzed data from a TIA cohort in order to assess the distribution of CoW variants in a similar vascular patient cohort without any intracranial vessel occlusion.

Limitations of the study are the small sample size of subgroups among the different CoW variants and classification into vascular models and subgroups of variants, which affect the power of our study. Furthermore, MRA may underestimate the size of vessels within the CoW compared to DSA as imaging gold standard [4]. Due to the small size of CoW segments, the true number of patients with a complete CoW might be higher. Nevertheless, the amount of different CoW variants we found was in accordance with other studies using different methods [9, 10]. Furthermore, the restriction to an LVO stroke cohort might have influenced or overlapped the effect of CoW variants on outcome.

In conclusion, our study shows that CoW variants are a frequent finding in ischemic stroke patients with MCA‐M1‐occlusion. There was no evidence for an association of CoW variants with 3‐month functional disability. However, the level of evidence indicates a trend towards a higher mortality in patients with any type of CoW variant and a higher frequency of incomplete CoW among patients dying within 3 months after stroke onset represent valuable hints to validate these results in future studies. In addition, the role of CoW variants for intracranial vessel occlusions other than MCA‐M1 and the association of the LMC status among the different subgroups of CoW variants with outcome could be addressed in further studies with larger patient cohorts.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

SWi has received a research grant from the Promedica Foundation, travel honoraria from Bayer and has received speaker honoraria from Siemens. JMH has received a travel grant from Pfizer. JK has received travel grants from Pfizer and Stryker and academic grants from the SAMW/Bangerter Foundation and the Swiss Stroke Society. SWe has received speaker honoraria from Amgen, travel honoraria from Bayer, a research grant from Boehringer Ingelheim and academic grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, the UZH (Clinical Research Priority Program Stroke), the Swiss Heart Foundation and the Olga Mayenfish Foundation. LPW, NL, CM, UH, KS, MEA, TD, LDP, UF, MRH, ARL, JG, MA and RW report no disclosures. All authors do not report any conflicts of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Laura P. Westphal: Data curation (equal); Formal analysis (lead); Investigation (lead); Methodology (equal); Visualization (equal); Writing‐original draft (lead). Niklas Lohaus: Data curation (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Sebastian Winklhofer: Methodology (equal); Supervision (equal); Validation (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Christian Manzolini: Data curation (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Ulrike Held: Methodology (lead); Supervision (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Klaus Steigmiller: Methodology (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Janne M. Hamann: Data curation (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Mohamad El Amki: Visualization (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Tomas Dobrocky: Data curation (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Leonidas D. Panos: Data curation (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Johannes Kaesmacher: Data curation (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Urs Fischer: Writing‐review & editing (equal). Mirjam R. Heldner: Data curation (equal); Writing‐review & editing (equal). Andreas R. Luft: Writing‐review & editing (equal). Jan Gralla: Writing‐review & editing (equal). Marcel Arnold: Writing‐review & editing (equal). Roland Wiest: Writing‐review & editing (equal). Susanne Wegener: Conceptualization (lead); Formal analysis (equal); Funding acquisition (lead); Supervision (lead); Writing‐review & editing (lead).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Anonymized data will be shared on request from any qualified investigator.

Supporting information

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF PP00P3_170683) and the UZH Clinical Research Priority Program (CRPP) Stroke is acknowledged.

Westphal LP, Lohaus N, Winklhofer S, et al. Circle of Willis variants and their association with outcome in patients with middle cerebral artery‐M1‐occlusion stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2021;28:3682–3691. 10.1111/ene.15013

REFERENCES

- 1. Forgo B, Tarnoki AD, Tarnoki DL, et al. Are the variants of the circle of Willis determined by genetic or environmental factors? Results of a twin study and review of the literature. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2018;21:384‐393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Krishnaswamy A, Klein JP, Kapadia SR. Clinical cerebrovascular anatomy. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;75:530‐539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Krabbe‐Hartkamp MJ, Van Der Grond J, De Leeuw FE, et al. Circle of Willis: morphologic variation on three‐dimensional time‐of‐flight MR angiograms. Radiology. 1998;207:103‐111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Van Seeters T, Hendrikse J, Biessels GJ, et al. Completeness of the circle of Willis and risk of ischemic stroke in patients without cerebrovascular disease. Neuroradiology. 2015;57:1247‐1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liebeskind DS. Collaterals in acute stroke: beyond the clot. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2005;15:553‐573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hendrikse J, Hartkamp MJ, Hillen B, et al. Collateral ability of the circle of Willis in patients with unilateral internal carotid artery occlusion: border zone infarcts and clinical symptoms. Stroke. 2001;32:2768‐2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhu G, Yuan Q, Yang J, Yeo JH. The role of the circle of Willis in internal carotid artery stenosis and anatomical variations: a computational study based on a patient‐specific three‐dimensional model. Biomed Eng Online. 2015;14:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453‐1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhou H, Sun J, Ji X, et al. Correlation between the integrity of the circle of Willis and the severity of initial noncardiac cerebral infarction and clinical prognosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hamming AM, Van Walderveen MAA, Mulder IA, et al. Circle of Willis variations in migraine patients with ischemic stroke. Brain Behav. 2019;9:e01223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Seifert‐Held T, Eberhard K, Christensen S, et al. Circle of Willis variants are not associated with thrombectomy outcomes. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2021;6:310‐313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shaban A, Albright KC, Boehme AK, Martin‐Schild S. Circle of Willis variants: fetal PCA. Stroke Res Treat. 2013;2013:105937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alpers BJ, Berry RG, Paddison RM. Anatomical studies of the circle of Willis in normal brain. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1959;81:409‐418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data will be shared on request from any qualified investigator.