Abstract

Purpose/Objective(s):

The risk of breast cancer-related lymphedema (LE) with the addition of regional lymph node irradiation (RLNR) was recently evaluated and an increased risk noted when RLNR is used. Here we analyze the association of technical radiation therapy (RT) factors in RLNR patients with the risk of LE development.

Methods and Materials:

From 2005–2012, we prospectively screened 1476 women for LE who underwent surgery for breast cancer. Among 1507 breasts treated, 172 received RLNR and had complete technical data for analysis. RLNR was delivered as supraclavicular (SC) irradiation (69%, 118/172) or SC + posterior axillary boost (PAB) (31%, 54/172). Bilateral arm volume measurements were performed pre- and postoperatively. Patients’ RT plans were analyzed for the following variables: SC field lateral border (relative to the humeral head), total dose to the SC, RT fraction size, beam energy, and type of tangent (normal vs. wide). Cox proportional hazards models were used to analyze associated risk factors for LE.

Results:

The median post-operative follow-up was 29.3 months (range 4.9–74.1). The two-year cumulative incidence of LE was 22% (95% CI: 15%, 32%) for SC and 20% (95% CI: 11%, 37%) for SC+PAB. None of the analyzed variables was significantly associated with LE risk (extent of humeral head: p=0.74 for <1/3 vs. humeral neck, p=0.41 for 1/3–2/3 vs. humeral neck; p=0.40 for fraction size 1.8 Gy vs. 2.0 Gy; p=0.57 for beam energy 6 MV vs. 10 MV; p=0.74 for tangent type wide vs. regular; p=0.66 for SC vs. SC + PAB). Only pre-treatment BMI (OR 1.09, 95% CI: 1.04–1.15, p=0.0007) and the use of axillary lymph node dissection (HR 7.08, 95% CI: 0.98–51.40, p=0.05) were associated with risk of subsequent LE development.

Conclusions:

Of the RT parameters tested, none was associated with an increased risk of LE development. This study underscores the need for future work investigating alternative RLNR risk factors for LE.

Keywords: Lymphedema, Regional Lymph Node Radiation, Breast Cancer

Summary:

Inclusion of regional lymph node radiation (RLNR) significantly increases the risk of breast cancer-related lymphedema (LE) compared to breast or chest wall radiation alone yet remains a cornerstone of radiotherapy for breast cancer. Here we analyze whether specific radiotherapy technical factors for RLNR affects subsequent development of LE among a large cohort of patients prospectively screened for LE.

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in females and the second most common cause of cancer death in women after lung cancer1. Lymphedema (LE) after treatment for breast cancer is a particularly physically and emotionally distressing morbidity2–3. Incidence rates as high as 30% have been reported for LE development after comprehensive surgery and radiotherapy (RT)4. There is interest in quantifying the risk conferred by adjuvant RT to the development of LE. In a prior report5, using a cohort of patients prospectively screened for LE, it was found that the addition of regional lymph node radiation (RLNR) to standard whole breast radiation conferred an excess risk of 1.7 (p=0.025) for the development of LE, but no difference was found between supraclavicular (SC) irradiation alone compared with the use of both SC and posterior axillary boost (PAB) fields. In this study, we analyzed dosimetric RT risk factors for the development of LE in patients treated with RLNR.

Multiple studies have established the benefit of RLNR in patients with positive lymph nodes at sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary dissection6–7. SC and PAB fields are combined with breast tangents to cover at-risk nodal levels in the axillary and SC regions, but there is substantial variability in treatment techniques employed due to differences in patient anatomy, treatment center norms, and other dosimetric considerations. The lateral border (relative to the humeral head) of the SC field is one parameter that is often adjusted during treatment planning, as are radiation fraction sizes, beam energies, and overall dose prescribed8. We hypothesized that one or more of these factors may contribute the subsequent development of LE. Therefore the purpose of this study was to analyze technical RT factors associated with the future development of LE, using a large cohort of breast cancer patients who received RLNR and were prospectively screened for lymphedema before and after definitive treatment.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Patients

We prospectively screened 1476 women for LE who underwent surgery for unilateral or bilateral breast cancer between 2005–2012. Among 1507 breasts treated, 313 (21%) received RLNR in addition to breast/chest wall irradiation. Of these, 197 (63%) received a SC field as RLNR, whereas 116 (37%) received both a SC and PAB. Complete technical data were available for 172/313 breasts and comprised this analysis. Each patient had >3 months of post-surgical follow-up.

Prospective LE assessments

Newly diagnosed breast cancer patients were prospectively screened for LE using a perometer as described in detail in a prior report5. This protocol was approved by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board. Arm volume is measured pre-operatively and at regular intervals corresponding with oncology visits during and after completion of breast cancer treatment. LE was defined as a ≥10% arm volume increase occurring >3 months post-operative based on consensus in the literature. Arm volume change was calculated at each follow-up visit. Measurements obtained ≤3 months after surgery were considered post-operative and not utilized to determine lymphedema incidence.

Radiation treatment

Of the 172 breasts in this study, all received RT at the Massachusetts General Hospital. After 2008, supraclavicular level I, II, and III axillary LN’s at our institution were contoured the majority of the time according to the RTOG atlas9. The lateral border of the SC field was defined by the treating physician. Patients’ RT plans were analyzed for the following variables: SC field lateral border (relative to the humeral head, characterized as <1/3, 1/3–2/3 or >2/3 of the head as viewed on an anterior-posterior DRR), total dose to the SC, RT fraction size, beam energy, and type of tangent (normal vs. wide). Data were abstracted from the electronic medical record and from within MOSAIQ, our departmental treatment planning and verification system.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to generate data on patient clinical and treatment characteristics. Univariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to evaluate risk factors for LE. Time-dependent covariates were included for use of systemic therapies and radiation fields such that cases were included in the unexposed group prior to initiation of a given treatment and in the exposed group thereafter10. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate and plot cumulative incidence of LE by SC lateral border11. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Description of the study cohort

Table 1 illustrates the distribution of clinical and pathologic characteristics of the study cohort. The median age of the cohort was 50.4 (range: 27.5–81.7), with a median BMI in the overweight range (26.7, range 18.8–42.8). The median tumor stage was T2 (2.5cm; range 0.05–10.5 cm). The majority of the patients (103, 60%) received mastectomy, with 149 (87%) receiving ALND and a median 16 lymph nodes (range 1–41) removed. Of 172 breast plans, 69% (118/172) included SC radiation, and 31% (54/172) included both SC + PAB.

Table 1-.

Clinical and pathologic characteristics of the study cohort.

| Median (Range) | n = 172 (100%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Characteristics | ||

| Age at diagnosis, years | 50.4 (27.5–81.7) | - |

| BMI at diagnosis, kg/m2 | 26.7 (18.8–42.8) | - |

| Pathologic Characteristics | ||

| Invasive tumor size*, cm | 2.5 (0.05–10.5) | - |

| Breast Surgery | ||

| Lumpectomy | - | 69 (40%) |

| Mastectomy | - | 103 (60%) |

| Axillary Surgery | ||

| SLNB | - | 23 (13%) |

| ALND | - | 149 (87%) |

| #LN’s removed, ALND | 16 (1–41) | - |

| # Positive LN’s, ALND | 2 (0–39) | - |

| Radiation Therapy | ||

| Whole breast/ chest wall + SC | - | 118 (69%) |

| Whole breast/ chest wall + SC +PAB | - | 54 (31%) |

| Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | - | 58 (34%) |

| No | - | 114 (66%) |

| Adjuvant Chemotherapy | ||

| Yes | - | 135 (78%) |

| No | - | 37 (22%) |

| Hormonal Therapy | ||

| Yes | - | 134 (78%) |

| No | - | 38 (22%) |

Abbreviations: BMI = Body Mass Index, ALND = Axillary lymph node dissection, SLNB = Sentinel lymph node biopsy, LN = lymph node, SC= Supraclavicular, PAB = Posterior Axillary Boost

Excludes tumor size for patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Table 2 shows the RT characteristics of the patients. The lateral border of the SC field was >2/3 of the humeral head in the majority (106, 61%) of cases. Nearly all (165, 96%) patients received regular tangents, and an en face boost (80, or 47% en face to chest wall, 77, or 45% en face to an intact or reconstructed breast). The predominant beam energy for the SC field was 6 MV (138, 80%), with nearly all patients receiving a total dose at or above 50 Gy (163, 95%).

Table 2-.

Radiation therapy characteristics of the study cohort.

| Median (Range) | n = 172 (100%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Lateral border of SC field, relative to humeral head | ||

| <1/3 | - | 34 (20%) |

| 1/3–2/3 | - | 32 (19%) |

| >2/3 | - | 106 (61%) |

| Breast tangent type | ||

| Regular | - | 165 (96%) |

| Wide | - | 7 (4%) |

| Boost type | ||

| En face to chest wall | - | 80 (47%) |

| En face to intact/reconstructed breast | - | 77 (45%) |

| Mini tangents | - | 6 (3%) |

| None | - | 9 (5%) |

| SC field energy, MV | 6 (4–15) | - |

| 4 | - | 4 (2%) |

| 6 | - | 138 (80%) |

| 10 | - | 29 (17%) |

| 15 | - | 1 (1%) |

| SC field total dose, cGy | 5040 (4200–5040) | - |

| <5000 | - | 9 (5%) |

| 5000 | - | 69 (40%) |

| 5040 | - | 94 (55%) |

| SC field fraction size, cGy | 180 (180–200) | |

| 180 | - | 102 (59%) |

| 200 | - | 70 (41%) |

Abbreviations: SC= Supraclavicular, PAB = Posterior Axillary Boost

Cumulative incidence of LE

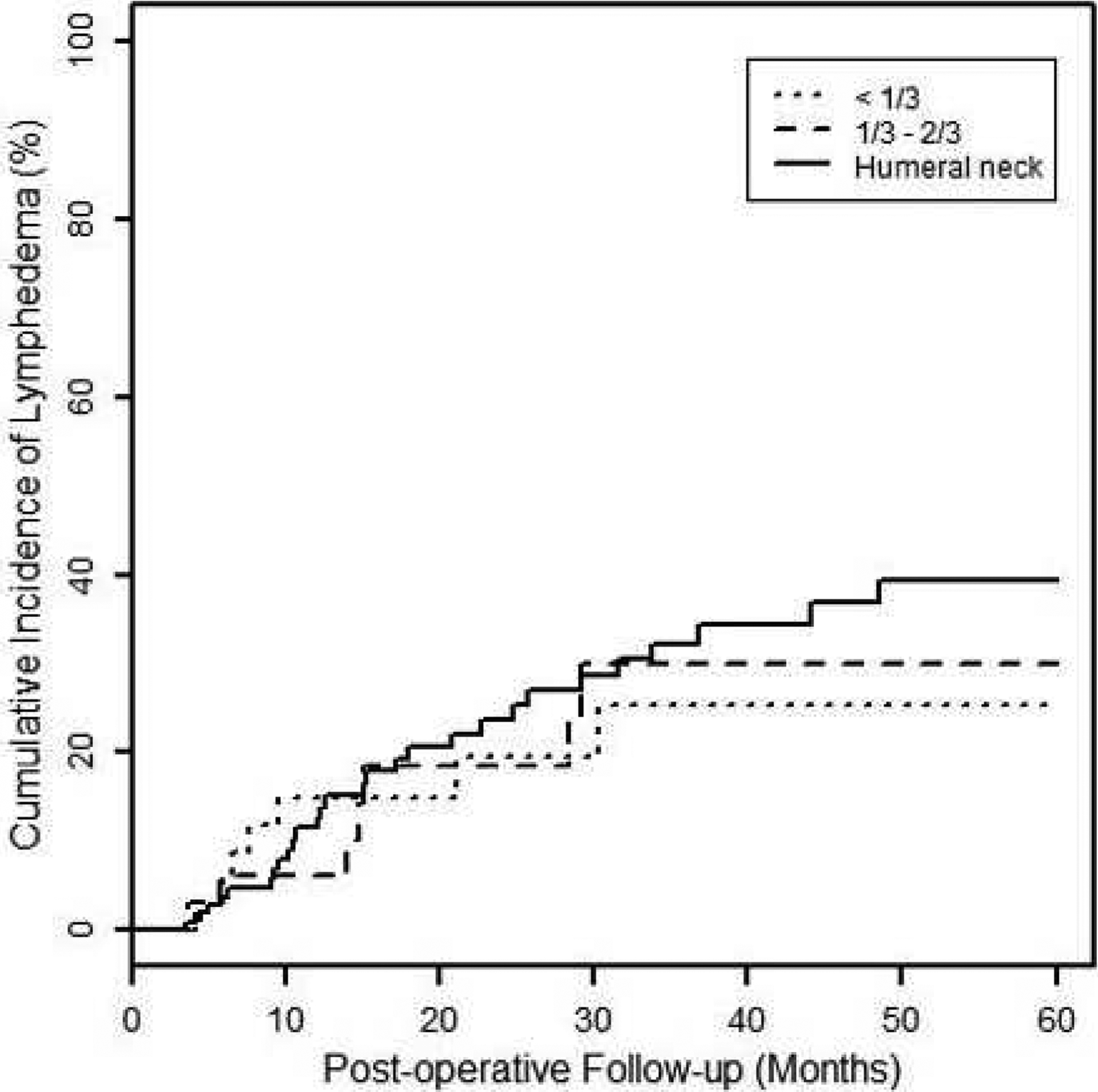

The median post-operative follow-up was 29.3 months (range 4.9–74.1). As shown in Table 3, the two-year cumulative incidence of LE was 22.27% (95% CI: 15.13%, 32.07%) and 20.98% (95% CI: 11.30%, 37.03%) for SC or SC+PAB, respectively. There was no significant difference in the incidence of LE by SC field lateral border (<1/3 humeral head: 19.50, 95% CI: 9.10%, 38.94%; 1/3–2/3 humeral head: 18.48, 95% CI: 8.05%, 39.19%; >2/3 humeral head: 23.69, 95% CI: 15.83%, 34.56%). Figure 1 plots the cumulative incidence of LE by SC field lateral border.

Table 3-.

Cumulative incidence of lymphedema at 24 months by type of regional radiotherapy.

| Cumulative Incidence of Lymphedema %, (95% Confidence Interval) |

|

|---|---|

| SC only | 22.27 (15.13–32.07) |

| SC+PAB | 20.98 (11.30–37.03) |

| SC field lateral border | |

| <1/3 humeral head | 19.50 (9.10–38.94) |

| 1/3–2/3 humeral head | 18.48 (8.05–39.19) |

| >2/3 humeral head | 23.69 (15.83–34.56) |

Abbreviations: SC= Supraclavicular, PAB = Posterior Axillary Boost

Figure 1:

Cumulative incidence of lymphedema stratified by lateral border (relative to humeral head) of supraclavicular field.

Associated risk factors for development of LE

Univariate analysis results are included in Table 4. Among the clinical and pathologic characteristics investigated, pretreatment BMI (HR 1.09, 95% CI: 1.04–1.15, p=0.0007) was statistically significantly associated with the subsequent development of LE. Type of axillary surgery, ALND versus SLNB (HR 7.08, 95% CI: 0.98–51.40, p=0.05) was also significant, with an increased risk noted among ALND patients. Among the RT variables tested, none was significantly associated with LE risk (extent of humeral head: p=0.73 for <1/3 vs. humeral neck, p=0.41 for 1/3–2/3 vs. humeral neck; p=0.40 for fraction size 180 cGy vs. 200 cGy; p=0.57 for beam energy 6 MV vs. 10 MV; p=0.74 for tangent type wide vs. regular; p=0.66 for SC vs. SC + PAB). Because there were no significant intervariable associations found on univariate analysis, a multivariate analysis was not performed.

Table 4-.

Univariate results for association of studied factors with risk of lymphedema.

| Variable | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Characteristics | |||

| Age at diagnosis | 1.00 | 0.98–1.03 | 0.76 |

| BMI | 1.09 | 1.04–1.15 | 0.0007 |

| Pathologic Characteristics | |||

| Invasive Tumor Size | 1.04 | 0.89–1.22 | 0.64 |

| Breast Surgery | |||

| Mastectomy vs. Lumpectomy | 1.39 | 0.74–2.60 | 0.31 |

| Axillary Surgery | |||

| ALND vs. SLNB | 7.08 | 0.98–51.40 | 0.05 |

| # LNs removed | 1.03 | 0.99–1.07 | 0.11 |

| # Positive LNs | 1.02 | 0.98–1.06 | 0.39 |

| Radiation Therapy | |||

| SC vs. SC + PAB | 1.15 | 0.61–2.16 | 0.66 |

| Regular vs. Wide Tangents | 0.71 | 0.10–5.17 | 0.74 |

| Chest wall vs. Intact en face boost | 1.24 | 0.66–2.30 | 0.50 |

| 6 MV vs. 10 MV SC field beam energy | 1.27 | 0.56–2.87 | 0.57 |

| 5000 cGy vs. 5040 cGy SC field total dose | 1.52 | 0.81–2.86 | 0.19 |

| 180 cGy vs. 200 cGy SC field fraction size | 0.77 | 0.42–1.42 | 0.40 |

| SC field: <1/3 vs. >2/3 of humeral head | 0.87 | 0.38–1.99 | 0.73 |

| SC field: 1/3–2/3 vs. >2/3 humeral head | 0.67 | 0.26–1.74 | 0.41 |

| Systemic Therapy | |||

| Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy | 1.04 | 0.54–1.99 | 0.92 |

| Adjuvant Chemotherapy | 0.70 | 0.33–1.46 | 0.34 |

| Hormone Therapy | 1.35 | 0.60–3.03 | 0.47 |

Abbreviations: BMI= Body Mass Index, SLNB = Sentinel lymph node biopsy, ALND = Axillary lymph node dissection, LN = Lymph node, SC = supraclavicular, PAB = posterior axillary boost

DISCUSSION

In a prior report, it was reported that the addition of RLNR to standard breast tangents increases the likelihood of the development of LE (OR 1.7, p=0.025), but no difference in risk was noted when both SC and PAB fields were added to tangents as compared to the addition of an SC field only. In this study, we sought to identify risk technical RT risk factors that explain why the addition of RLNR confers excess risk for the subsequent development of LE. Consistent with prior findings, we noted that increased pretreatment BMI confers added risk for the development of LE, and also noted that ALND increases risk, but did not find a difference among any of the RT technical risk factors investigated. We chose several commonly adjusted variables (SC field lateral border, type of boost, type of tangent, field energy/fraction size/dose) and noted no distinctions between patients who subsequently developed LE and those that did not. These findings raise the possibility of alternative RT risk factors for the subsequent development of LE after RLNR. For example, further dosimetric analysis of LE patient treatment plans may find particular anatomic regions that are susceptible to dose inhomogeneity or are dose-sensitive. Moreover particular susceptible patient subgroups, such as those based on demographics, comorbidities, or other aspects of treatment, may be uncovered by future studies powered to detect such differences.

As with the prior study, this cohort of patients was prospectively screened for LE at a single institution between 2005–2012, and consequently comprises a group of patients that received modern RT and surgical treatment techniques. Moreover they were screened for LE development using a perometer, an optoelectronic system that is capable of detecting LE with high sensitivity, at predefined time points pre- and post-operatively. However, because a relatively high proportion of our patients who developed lymphedema (87%) received an ALND, a known risk factor for the development of LE, and the cumulative incidence of LE development was high (>20%), it is possible that the effect of independent RT risk factors on LE development was obscured in this cohort. Also, because our study is limited by a relatively small final sample size (172 treatment events), it is also possible that our study did not have sufficient power to uncover relatively rare RT-related events. Our study is further limited by the patients being drawn from a single institution, which may account for similarities in how patients were treated, or may suggest a systematic cause for LE development in these patients, not accounted for by standard RT variables.

Multiple studies have established the benefit of RLNR in the treatment of women with breast cancer12 and the recent initial reports of NCIC-CTG MA.2013 and EORTC 22922–1092514 studies have noted superiority for RLNR in patients with early stage and locally-advanced cancer. These studies foreshadow a potential future increase in the number of women receiving RLNR and thus at risk for the development of LE. For example, in MA.20, high-risk women (defined by positive LN or negative LN with high risk features) who underwent breast conserving therapy were randomized to receive standard breast tangents with or without RLNR. Inclusion of RLNR improved locoregional DFS, distant DFS, and trended towards a statistically significant improvement in OS. It is likely that more women with either 1–3 positive lymph nodes or high-risk features without positive lymph nodes will be receiving RT in the future. Future studies investigating alternative risk factors for development of LE are needed. We envisage a larger RCT, drawing patients from multiple institutions with greater heterogeneity in treatment variables and outcomes. Studying such a group would facilitate in-depth dosimetric investigation with correlation to the subsequent development of LE and may minimize bias related to patients being treated at one institution. Future work aimed at early detection and assessment of patients for LE are also needed.

In conclusion, we did not find any specific RT technical parameters underpinning our prior observation that the addition of RLNR to standard breast RT confers excess risk to the future development of LE. Among our cohort, we noted that pre-treatment BMI continues to be a modifiable risk factor for the future development of LE, as well as the use of ALND. Clinicians should continue to weigh the potential benefits of RT against the risk of LE in individual patients. Larger prospective studies may be helpful in understanding what components of RLNR predispose patients to the development of LE.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society, Cancer Facts & Figures, American Cancer Society, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed RL, Prizment A, Lazovich D, et al. Lymphedema and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: the Iowa Women’s Health Study. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5689–5696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jager G, Doller W, Roth R. Quality-of-life and body image impairments in patients with lymphedema. Lymphology 2006;39:193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLaughlin SA, Wright MJ, Morris KT, et al. Prevalence of lymphedema in women with breast cancer 5 years after sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary dissection: objective measurements. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5213–5219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warren LE, Miller CL, Horick N, et al. The impact of radiation therapy on the risk of lymphedema after treatment for breast cancer: a prospective cohort study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014;88:565–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Overgaard M, Hansen PS, Overgaard J, et al. Postoperative radiotherapy in high-risk premenopausal women with breast cancer who receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group 82b Trial. N Engl J Med 1997;337:949–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ragaz J, Jackson SM, Le N, et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy in node-positive premenopausal women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med 1997;337:956–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ceilley E, Jagsi R, Goldberg S, et al. Radiotherapy for invasive breast cancer in North America and Europe: results of a survey. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005;61:365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White J, Tai A, Arthur D, et al. Breast Cancer Atlas for Radiation Therapy Planning: Consensus Definitions. Available at: http://www.rtog.org/CoreLab/ContouringAtlases/BreastCancerAtlas.aspx.

- 10.Klein JP, Moeschberger ML. Semiparametric proportional hazards regression with fixed covariates. In: Klein JP, Moeschberger ML, editors. Survival Analysis: Techniques for Censored and Truncated Data. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2003. pp. 243–293. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Non-parametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Effect of radiotherapy after mastectomy and axillary surgery on 10-year recurrence and 20-year breast cancer mortality: meta-analysis of individual patient data for 8135 women in 22 randomised trials. Lancet 2014;383:2127–2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whelan TJ, Olivotto I, Ackerman I, et al. NCIC-CTG MA.20: An intergroup trial of regional nodal irradiation in early breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011. ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings (Post-Meeting Edition). Vol 29, No 18_suppl (June 20 Supplement), LBA1003. Available at: http://meeting.ascopubs.org/cgi/content/abstract/29/18_suppl/LBA1003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poortmans PSH, Kirkove C, Budach V, et al. Irradiation of the internal mammary and medial supraclavicular lymph nodes in stage I to III breast cancer: 10 years results of the EORTC radiation oncology and breast cancer groups phase III trial 22922/10925. Eur J Cancer 2013; 47(Suppl 2). [Google Scholar]