Abstract

Malaria remains one of the world's most life-threatening diseases and, thus, it is a major public health concern all around the world. The disease can become devastating if not treated with proper medication in a timely manner. Currently, the number of viable treatment therapies is in continuous decline due to compromised effectiveness, probably owing to the complex life cycle of Plasmodium falciparum. The factors responsible for the unclear status of malaria eradication programmes include ever-developing parasite resistance to the most effective treatments used on the frontline (i.e., artemisinin derivatives) and the paucity of new effective therapeutics. Due to these circumstances, the development of novel effective drug candidates with unique modes of action is essential for overcoming the listed obstacles. As such, the discovery of novel chemical compounds based on validated pharmacophores remains an unmet need in the field of medicinal chemistry. In this area, functionalized phthalimide (Pht) analogs have been explored as potential candidates against various diseases, including malaria. Pht presents a promising bioactive scaffold that can be easily functionalized and thus utilized as a starting point for the development of new antimalarial candidates suitable for preclinical and clinical studies. In this short review, we highlight a wide range of Pht analogs that have been investigated for their activity against various strains of Plasmodium falciparum.

Potent phthalimide-based antiplasmodial compounds are active at different stages of the Plasmodium falciparum life cycle.

1. Introduction

Malaria is an epidemic issue that causes high levels of suffering around the world and ceaselessly affects millions of human lives every year. The disease is caused by a parasitic protozoan and transmitted through the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito.1 Although it is a preventable and curable disease, it ranks as one of the major health challenges in the world.2 Emerging resistance against artemisinin and its partner drugs and chemical resistance to insecticides are creating a critical situation when it comes to malaria eradication.3 To interrupt this increasing resistance against frontline antimalarials, there is an urgent need to explore efficacious antimalarials possessing acute multistage activity with minimal or no toxicity. Another associated challenge includes asymptomatic malaria infection, which creates complications relating to disease diagnosis in regions of Africa with high endemicity.4 Currently, the available vaccine, i.e., the RTS, S malaria vaccine, exhibits only ∼36% efficacy, and booster doses are essential to maintain its effectivity.5 Currently, malaria is mainly a disease present in tropical and subtropical regions because the temperature in these regions is ideal for the growth of the parasite.6 Although various control programs implemented around the world have led to a decline in new malaria cases and reduced mortality rates, an estimated 229 million cases were reported in the year 2019.

The mortality rate has decreased significantly since 2011 and has continued to show a downward trend. Likewise, the number of deaths has reduced from 536 000 in 2011 to 409 000 in 2019, as described in Fig. 1.7 Overall, this progress is not significant enough to realize the dream of eradicating malaria from the earth. The eradication of malaria is challenging due to several factors, such as the evolution of drug-resistant strains and the complex life cycle of the parasite. Among the five different species of Plasmodium parasite (P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae, and P. knowlesi) that infect human hosts, P. falciparum is mainly responsible for human malarial cases.8,9 Antimalarial drug discovery has a long history, e.g., during World War II, a German scientist, Hans Andersag, synthesized chloroquine (CQ) as the first effective antimalaria therapeutic, and this was used on a large scale along with its derivative hydroxychloroquine (HCQ).10 CQ and HCQ were highly advantageous and inexpensive first-line treatments against malaria for decades, with high efficacy, good tolerability, and minimal toxicity.11 After 20 years of continuous and extensive use, the first cases of CQ-resistant falciparum strains were reported in Southeast Asia and South America, which eventually reached African countries.12 Various enzymes might work together to aid the survival of the parasite, thus, blocking their function may be crucial for killing it. Plasmodium kinases are examples of such druggable targets due to their activity against multiple forms of P. falciparum.13

Fig. 1. Estimated numbers of worldwide malaria deaths by year (source: World Health Organization report on malaria, 2020).

In P. vivax endemic regions, CQ monotherapy or CQ combined with primaquine (PQ) remains a frontline treatment due to the sensitivity of this strain.14 Additionally, a few effective therapeutics are available for malaria, including quinolines, naphthoquinones, 8-aminoquinolines, and artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT).15 ACT is a rapid treatment and the most reliable approach; it involves the administration of ART derivatives combined with other effective partner drugs, viz., mefloquine (MQ), lumefantrine (LUM), and piperaquine (PPQ). Over time, reports on the emergence of drug resistance to ACT15 have created an alarming situation, particularly in endemic regions. This warrants the discovery of novel effective and inexpensive drugs, which are essential for combatting this disease. To reduce the risk of resistance, molecules with multistage activity are in high demand, as they can destroy the parasite in the liver stage, the asexual blood stage, the gametocyte stage, and the insect ookinete stage of the parasitic life cycle.16 Of the available approved drugs, only atovaquone (ATQ) and pyronaridine have been identified as being effective against multiple life stages of the parasite, thus demonstrating multistage antimalarial activity;17 this further advocates the development of novel, safe, and more effective drugs against malaria.

In drug design, the selection of a validated pharmacophore remains a hard task, as this drives the activity profiles of the resulting therapeutic candidates. As such, Pht compounds functionalized with various scaffolds offer great advantages due to their potential applications against several diseases, viz., schistosomiasis,18 malaria,18 leishmaniasis,19 tuberculosis,20 dengue,21etc. Pht was explored as a starting precursor for the synthesis of several PEG-scutellarin prodrugs by Luo et al.22 Notably, three drugs named thalidomide (1998),23 lenalidomide (2006),24 and pomalidomide (2013)25 possessing a Pht scaffold were approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in the human population. Muniz-Junqueira et al.26 reported that thalidomide influences the fatality rate of P. berghei as it interferes with the phagocytic function of macrophages; thus, it might decrease the severity of malaria infections. In addition to thalidomide, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide, numerous Pht functionalized compounds have been investigated, supporting their potential use in medicinal chemistry and drug discovery in the fight against malaria. Besides, our group have utilized the Pht moiety to construct antiplasmodial candidates with safe bioactivity profiles. As we feel positively toward Pht compounds, we think it is worthwhile compiling all relevant literature reports to provide a short review article summarizing recent updates on the use of Pht analogs as antiplasmodial agents, which could open up new directions for future growth in the area.

2. Malaria parasite life cycle

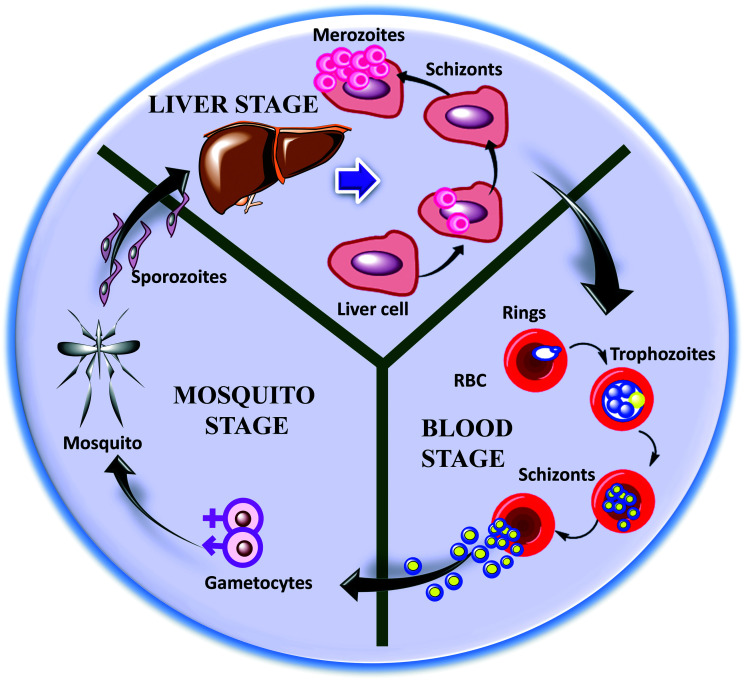

The malaria parasite life cycle is a complicated process and may vary for different species of Plasmodium.16 The Plasmodium parasite is a unicellular eukaryote that undergoes remarkable morphological transformations during the course27 of its life, including sporozoite, merozoite, trophozoite, and gametocyte stages, spanning two hosts (mosquitos and human being), as shown in Fig. 2.27,28 Infection with this pathogen starts with the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito, which injects Plasmodium sporozoites into the human host.29 Afterwards, these sporozoites settle beneath the dermis and migrate to the liver through blood or plasma (lymphatic system),30 which marks the initiation of the liver/exoerythrocytic stage of the parasite.31 In the liver, sporozoites invade hepatocytes and, after a period of 7–10 days, they start multiplying and differentiate into tissue schizonts, a process termed schizogony.16 Subsequently, these newly formed tissue schizonts produce hundreds and thousands of merozoites, followed by mammalian cell rupture. These hepatic merozoites are later released into the bloodstream where they enter the blood stage or erythrocytic stage via invading and replicating within red blood cells (RBCs). This blood stage indicates the clinical representation of malaria infection.32

Fig. 2. A pictorial presentation of the various life stages of the malaria parasite P. falciparum.

Next, these merozoites adopt a ring structure as early-stage trophs which, after maturation, are converted into trophozoites. Trophozoites cause the rapid catabolism of the hemoglobin, as they exhibit high metabolic activity, and they are easily identifiable under a microscope.33 Further, upon DNA replication and segmentation, trophozoites change into multiple schizonts and produce new merozoites, which re-invade new RBCs.27 In the early erythrocytic stage, some of asexual trophozoites initiate the sexual gametocyte stage via differentiating into male and female gametocytes, which ensures parasite transmission into the mosquito vector. Then, the development of gametocytes takes place through fertilization and maturation in the midgut of the mosquito, leading to the formation of ookinetes. Then, ookinetes move into the haemocoel and turns into oocysts, which further change into sporozoites.30 These sporozoites continue the life cycle of the malaria parasite, and the process described above begins again.

3. Pht-based compounds explored as antiplasmodial candidates

In this section, we classify Pht compounds based on other important pharmacophores that have been utilized to prepare novel analogs, and these are discussed in detail.

3.1. 4-Aminoquinoline–Pht analogs

The 4-aminoquinoline scaffold has high medicinal importance, as most approved antimalarial drugs contain it as a core moiety. A few such examples include CQ,34 HCQ,35 MQ,36 and PPQ.37 This scaffold has emerged as one of the most important scaffolds for the development of novel molecules with improved antiplasmodial efficacy. A report by Kumar et al. explored the effects of 4-aminoquinoline-based Pht compounds on antiplasmodial activity against the CQ-resistant P. falciparum strain W2.38 In order to synthesize Pht–4-aminoquinolines, the authors optimized a microwave-irradiation-supported procedure to accomplish the desired compounds, as depicted in Fig. 3A. Interestingly, microwave-irradiation reactions yielded the desired products in 89% yield within 2 min when performed in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO). On the other hand, conventional heating for 8 h afforded only 51% yield. The authors first synthesized 4-aminoquinoline precursors (3) via treating 4,7-dichloroquinoline (1) with different diamines (2) in the presence of triethylamine. Subsequently, 4-aminoquinoline precursors (3) were irradiated using microwaves with substituted phthalic anhydrides (4) to accomplish the desired Pht analogs (5a–y). A total of twenty-five Pht–aminoquinoline analogs were synthesized and then evaluated against the W2 strain of the malaria parasite, leading to four hits possessing comparable activity to CQ (IC50: 67 nM). The identified hits, 5d, 5j, 5n, and 5w, showed IC50 values of 110, 120, 120, and 100 nM, respectively. Next, their cytotoxicity effects were evaluated against J774 murine macrophage cells, showing that 5w was the least toxic compound (CC50: 29.11 μM). The TI (therapeutic index) of the most potent compound (5w) was noted to be 291, which was reasonably good. Largely, the Pht–4-aminoquinoline analogs displayed potent antiplasmodial efficacy against the W2 strain, and they may be further explored, testing their efficacy against other Plasmodium strains in cultures and animal models. For future studies, variations of the Pht moiety may be explored to improve the antiplasmodial activity and gain a higher selectivity index (SI) without any cytotoxicity.

Fig. 3. A) The synthetic route to Pht–4-aminoquinoline analogs (5a–y). The inset table shows the substituent variations, with various R groups and different numbers (n) of carbon atoms. B) The structure of AQ. C) The structure and synthetic route to Pht–N-phenyl analogs (12a–f).

3.2. N-phenyl–Pht analogs

The ubiquinone analog AQ was approved for the treatment of malaria in 1992, particularly for liver-stage infection.39 AQ was studied and it was found that it binds to the oxidation site of the cytochrome bc1 enzyme complex.40 This enzymatic complex is essential for preserving the stable membrane potential of mitochondria as it helps in the catalysis of electron transfer.41 AQ consists of two important pockets, i.e., the 1,4-naphthoquinone moiety (pocket A) and a para-substituted phenyl ring (pocket B), as presented in Fig. 3B. AQ structure-based design and the development of inhibitors against the bc1 cytochrome complex have been investigated, and the Pht scaffold was included as a crucial synthon. Cytochrome bc1 inhibitors are anticipated to exhibit antiplasmodial activity against both liver stage and blood stage infection.42 Bolzani et al.43 designed N-phenyl-based Pht analogs, where Pht and para-substituted anilines served to mimic pockets A and B of AQ, respectively. The molecular docking of these novel compounds suggested their binding towards the Qo site (oxidation site at coenzyme Q) of cytochrome bc1. The synthesis of N-phenyl–Pht analogs (Fig. 3C) began with refluxing 3-nitrophalic acid (6) and acetic anhydride to yield compound 7, which underwent reduction to yield 3-aminophalic anhydride (8). Compound 8 was treated with different para-substituted anilines (9a–e) under reflux conditions to generate N-phenyl-based analogs (10a–e). The amino group of the N-phenyl compounds (10a–e) was converted to benzyl upon treatment with benzyl bromide (11) in DMF to obtain N-phenyl–Pht analogs (12a–e).

A total of twelve novel Pht analogs were synthesized and evaluated for antiplasmodial activity against the 3D7 strain of P. falciparum, leading to the hit compounds 10f and 12f with IC50 values of 4200 nM and 6800 nM, respectively. Both hits, 10f and 12f, possess a para-methoxy substituent, thus indicating the importance of this group for killing the parasite. Next, the cytotoxicity effects of these compounds were assessed towards the HepG2 liver cell line and the CC50 values of both hits were noted to be greater than 250 μM. The TI of compound 10f was found to be >36 while that of 12f was a little higher, >59. It was noted that compound 10f exhibited stage-specific effects with activity during the later ring stages (i.e., late rings or early trophozoites). Further, the extraction of mitochondrial fractions from 3D7 parasites was carried out to perform enzymatic assays using compound 10f at a concentration of 70 μM. The results showed that the cytochrome bc1 complex is the molecular target for compound 10f, with 74% inhibitory activity. Similar to AQ, compound 10f showed a stage-specific and slow-acting mechanism against P. falciparum. However, the hit compound 10f was not evaluated for its efficacy in combination with known drugs to obtain insight into synergistic or additive effects. The substitution of phenyl rings at different positions, such as ortho and meta, could also be explored, which might deliver lead compounds with improved antiplasmodial activity without any toxic effects.

3.3. Abietane–ferruginol–Pht analogs

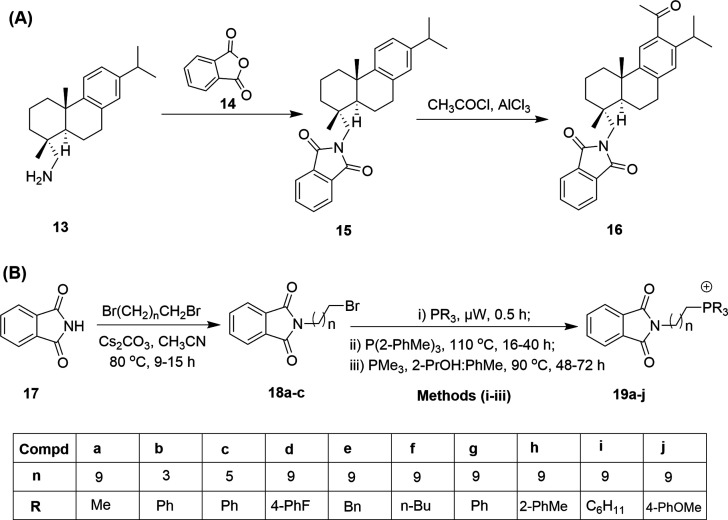

In general, the majority of therapeutics, including antimalarials, originate from natural sources such as plants.44 For instance, ferruginol, an abietane-type diterpene isolated from the Miro tree (Prumnopitys ferruginea) from New Zealand, was seen to offer favorable pharmacological properties, making this natural product an important synthon for therapeutic applications. Ferruginol was subsequently shown to display various potential bioactivities, viz. antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, antiulcer, and cardioactive properties, and activity against prostate cancer.45 Likewise, other studies have also supported the suitability of ferruginol as a high-value pharmacophore for antimalarial drug discovery.46–48 González et al.49 were encouraged by the significance of ferruginol and synthesized eleven new analogs possessing the Pht moiety as one of the important scaffold components. Initially, they screened all the analogs against two malarial strains (3D7 and K1) and compared their results with ferruginol and CQ, which were used as positive controls. Among the eleven analogs, compound 16 displayed potent activity, with EC50 values of 86 nM (3D7) and 201 nM (K1) in comparison to values of 23 nM (3D7) and 69 nM (K1) shown by CQ. On the other hand, ferruginol displayed EC50 values of 2470 nM and 1330 nM against the 3D7 and K1 strains, respectively. Compound 16 was also evaluated for its cytotoxicity (>25 μM) against the HepG2, RAJI, BJ, and HEK293 cell lines. The TI values of compound 16 were higher than 290 and 124 against the 3D7 and K1 strains, respectively.

The synthesis of the hit compound 16 was carried out via introducing the Pht group to (+)-dehydroabietylamine 13, which yielded 15, as shown in Fig. 4A.

Fig. 4. The structure and synthesis of (A) 12-acetyl-N,N-phthaloyldehydroabietylamine (15) and (B) Pht-based phosphonium ions (19a–j). The inset table shows the substituent variations for compounds 19a–j with various R groups and different numbers (n) of carbon atoms.

Further, the Friedel–Crafts acylation of 15 afforded the desired analog 16 in 88% yield. New ferruginol analogs exhibited higher inhibitory activities against P. falciparum than the parent compound ferruginol. However, the efficacy of 16 was lower than that of CQ. Overall, the hit ferruginol analog 16 can inspire further detailed structure–activity relationship studies for target identification, lead optimization, and in vivo validation studies.

3.4. Phosphonium-ion–Pht analogs

Long et al.50 synthesized phosphonium-cation-centered Pht analogs. The authors specifically selected the phosphonium cation considering its importance as a mediator of antineoplastic,51 antioxidant,52 and antimicrobial53 effects in mitochondria. Additionally, one of the phosphonium-cation-based analogs, mitoquinone (MitoQ),52 has progressed to phase II clinical trials for the treatment of fatty liver disease, Parkinson's disease, and hepatitis C. Newly synthesized phosphonium–Pht conjugates were evaluated against the P. falciparum CQ-resistant strain W2. The synthesis of novel analogs was carried out as outlined in Fig. 4B. Firstly, isoindoline-1,3-dione (17) was converted to N-alkyl Pht compounds (18a–c) upon treatment with different dibromoalkanes. The N-alkyl–Pht compounds (18a–c) were further coupled with a tertiary phosphine under different conditions (i.e., i, ii and iii shown in Fig. 4B) to generate the final phosphonium–Pht analogs (19a–j).

IC50 values were recorded to be in the range of 134.0 nM to >3500 nM in comparison to a value of 66.9 nM for CQ. Among the ten newly synthesized analogs, (10-(1,3-dioxoisoindolin-2-yl)decyl)tris(4-methoxyphenyl)phosphonium (19j) showed the most significant antiplasmodial efficacy with an IC50 value of 134 nM against W2. The authors conclude that the antiplasmodial activities of the new analogs could be attributed to the presence of the phosphonium moiety. Phosphonium lipocation analogs are mitochondrion-acting agents, as their activity is conferred by the charge-mediated accumulation of lipocations inside organelles. Lipocations also show good distribution in erythrocyte tissue, which is most susceptible to damage by infection from malarial parasites; however, additional experiments are necessary to support these observations.

3.5. Pht–cyclic amine analogs

Various studies are reported where cyclic amines, viz., pyrrolidines, piperidines, piperazines, and 4-benzylpiperidines, have been utilized to functionalize other scaffolds, resulting in antiplasmodial efficacy.54,55 In this line of research, Singh et al.56 designed and synthesized Pht–cyclic amine analogs and evaluated their antiplasmodial efficacy in P. falciparum 3D7 cultures. A set of twenty chiral Pht–cyclic-amine-based compounds was synthesized and characterized, as shown in Fig. 5. In the first step, phthalic anhydride (14) and different amino acids (20a–d) were reacted to afford N-phthaloyl-l-amino acids (21a–d), which were further coupled with cyclic amines in the presence of thionyl chloride as an activating group to yield the final compounds (22–41). Of all the synthesized analogs, 31 and 41 displayed potent antiplasmodial activity when assessed via [3H]hypoxanthine assays. Both the analogs, 31 and 41, blocked the life cycle of the parasite via inhibiting the invasion of merozoites into fresh red blood cells and they showed more activity towards the ring and trophozoite stages, therefore blocking the next cycle. Further, a reduction in IC50 values was obtained for Pht 31 and 41 after increasing the incubation period from 60 to 90 h. The IC50 value of 31 was reduced from 5000 nM to 3800 nM, whereas that of 41 was reduced from 2000 nM to 1100 nM. Thus, compound 41, possessing piperazine as a linker unit, displayed the highest potency among all the analogs.

Fig. 5. The synthetic route and structures of Pht–cyclic amine analogs (22–41).

Further, in vitro combination assays were carried out using 41 and ART against the Pf3D7 malaria strain. Variable concentrations of ART were used in combination with 41, i.e., 25 ng mL−1, 12.5 ng mL−1, and 6.25 ng mL−1; of these, 25 ng mL−1 ART with 41 displayed significant results, with an IC50 value of 1390 nM after 42 h of incubation. Certainly, the combination assay results showed the improved efficacy of analog 41, however, animal studies are necessary to validate the cell-based results. Next, all Pht analogs were tested against falcipain-2, a cysteine protease that causes hemoglobin degradation.57 Pht 23 and 35, possessing phenylalanine, significantly inhibited the activity of falcipain-2. However, the mechanism of action is not clear for these Pht analogs against P. falciparum. Common molecular targets can be anticipated in both stages (ring and trophozoite stages) to explain the antimalarial activity. Further studies could be performed to identify the molecular targets of this class of compounds, as well as their mechanisms of action.

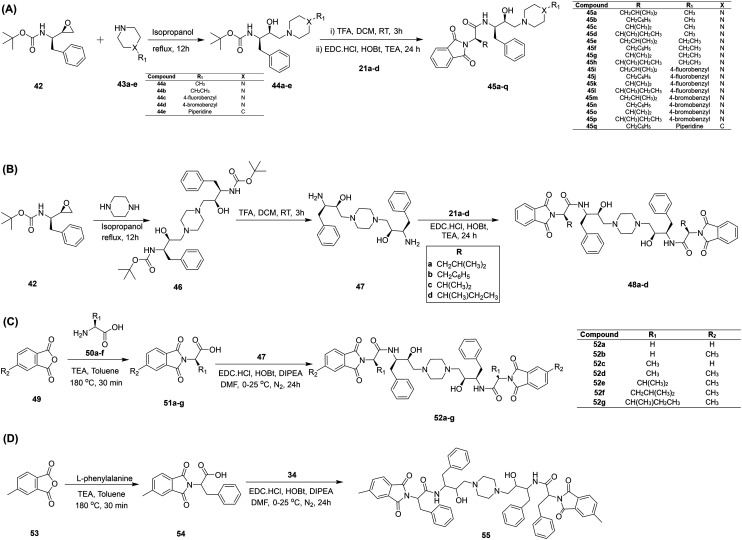

3.6. Hydroxyethylamine–Pht analogs

Hydroxyethylamine (HEA) analogs have been identified as important pharmacophores with huge application potential in medicinal chemistry.58–60 In HEA, the β-alcohol is the essential structural element, mimicking a tetrahedral intermediate during the peptide bond cleavage of aspartic proteases; thus, it plays a crucial role in the antimalarial activity.61,62 The therapeutic importance of the HEA scaffold is highly valued, as it shows potent multistage antimalarial activity with negligible cytotoxic effects, which is strongly needed for rational drug design for malaria eradication.17 Singh et al.63 designed and synthesized a series of Pht analogs possessing the HEA pharmacophore. Firstly, analogs were developed via refluxing the Boc-protected epoxide 42 with different cyclic amines (43a–e) to afford Boc-protected HEA analogs (44a–e), which were deprotected followed by coupling reactions with N-phthaloyl-l-amino acids (21a–d) to yield the desired Pht–HEA analogs (45a–q), as shown in Fig. 6A. Likewise, another set of C2 symmetrical analogs (48a–d) was synthesized as described in Fig. 6B. A total of twenty-seven HEA–Pht analogs were evaluated against plasmepsin (Plm) II and IV enzymes, which are considered potential drug targets. Compound 48d, with Ki = 990 nM, was found to be a potential inhibitor of Plm II, whereas 48c exhibited better activity against Plm IV, with a Ki value of 3300 nM. All the analogs were further tested against P. falciparum 3D7 cultures, and compound 44e showed potent activity with an IC50 value of 1160 nM. The compounds 45j (IC50 = 1330 nM), 45o (IC50 = 1250 nM), and 48b (IC50 = 1300 nM) also displayed comparable antiplasmodial efficacies. These four compounds were further evaluated against the CQ-resistant strain 7GB and showed inhibitory concentrations between 2990 nM and 3600 nM. Compound 48b, possessing C2 symmetry, was found to be the least toxic when tested against the MCF-7 cell line. Largely, the study presented HEA–Pht analogs with potent antiplasmodial activities, particularly C2 symmetric ones; thus, these could be investigated for their activity profiles in animal models.

Fig. 6. The synthesis of Pht analogs functionalized with HEA. A) Unsymmetrical analogs (45a–q); B) C2-symmetric analogs (48a–d); C) C2-symmetric optimized analogs (52a–g); and D) the C2-symmetric hit compound 55.

In another study, Singh et al.64 explored HEA-based Pht analogs with C2 symmetry against the CQ-sensitive strain 3D7, targeting Plm II and IV. New analogs with C2 symmetry were synthesized following the procedure outlined in Fig. 6B. Rational variations were implemented at the Pht moiety to afford novel Pht–HEA analogs with C2 symmetry (52a–g), as shown in Fig. 6C. All the prepared analogs were screened for their activities against Plms, and compound 52f showed significant activities, with Ki values of 1930 nM and 1990 nM against Plm II and IV, respectively. Another compound, 52g, selectively inhibited Plm IV with a Ki value of 840 nM. In cell-based assays of P. falciparum (3D7), these two analogs, 52f and 52g, exhibited IC50 values of 2270 nM and 3110 nM, respectively. These C2-symmetric Pht–HEA analogs may be utilized as apparent leads for the development of novel safe antimalarial molecules; however, additional experiments are necessary to further validate their efficacy.

Inspired by previous results relating to HEA–Pht analogs, Singh et al.65 developed a novel C2-symmetric compound 55 following a similar route, as depicted in Fig. 6D. Compound 55 was tested against CQ-sensitive (3D7), drug-susceptible (PfD6), and drug-resistant (PfDd2) strains and the IC50 values were found to be 1310 nM, 910 nM, and 600 nM, respectively. A cytotoxicity assay for 55 was also performed against two cell lines, i.e., leukemic monocytic cells (U937) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Compound 55 showed CC50 values of 11.1 μM and 26.4 μM against PBMCs and U937 cells, respectively. To identify the target, 55 was evaluated against multiple Plms. Compound 55 displayed the most potent activity against Plm II (Ki = 112 nM), followed by Plm IV (Ki = 252 nM), Plm V (Ki = 530 nM), and Plm X (Ki = 3830 nM). Next, molecular docking studies were also performed to substantiate the enzymatic assay results. Notably, the most-significant interaction of 55 was with Plm II over the other Plms, thus validating the enzymatic results, with a binding free energy value of −140.92 kcal mol−1. When combination assays were carried out, compound 55 displayed a synergistic effect with dihydroartemisinin (DHA) and mild synergistic activity with PPQ, while no synergistic effects were observed with either CQ or MQ. Further, compound 55 was assayed for activity against liver-stage malaria infection (P. berghei) and the sexual erythrocytic stage of malaria infection (gametocyte stage).

To test 55, P. berghei sporozoites were used to infect the human hepatoma cell line (HepG2 cells), and the IC50 value was found to be 2100 nM from cell cultures. The in vitro IC50 value against the gametocyte stage for 55 was noted to be 1680 nM. Inspired by the in vitro results, in vivo experiments, including blood-stage parasite load and liver-stage infection studies, were also carried out using the same compound. However, no significant results were observed toward in vivo liver-stage infection. In addition, the inhibitory effects of compound 55 against blood-stage infection in an infected mouse model were examined. Two days after infection with the P. berghei NK 65 strain, the mice were dosed with a 100 mg kg−1 concentration of compound 55 for four consecutive days. As observed, there was a decrease in the parasite load after 3 days of treatment. Overall, the mice survived for 20 days post infection. Next, a similar experiment was carried out, except with the addition of 5 mg kg−1 artemisinin. An extended survival period of 15 days post infection and a more significant reduction in parasitemia were noticed compared to the monotherapy approach. In conclusion, the Pht–HEA compound 55 could offer the possibility on inhibiting multiple stages of the malaria parasite life cycle, hence providing a lead starting point for further preclinical studies.

3.7. Benzimidazole- and triazole-based Pht analogs

In recent years, benzimidazole66 and triazole67 centered compounds have been shown to exhibit good antimalarial activities combined with great pharmacological properties. Kumar et al.68 utilized these crucial heterocycles, anticipating an interesting alliance between Pht, benzimidazole, and triazole within a molecule, and synthesized a series of thirty-one novel derivatives (62a–e′) supported by click chemistry and non-conventional microwave irradiation. The synthesis of these analogs was carried out via coupling N-phthaloyl-l-amino acids (56a–c) with benzene-1,2-diamine 57 to yield compounds (58a–c) that were further reacted with 1-bromoprop-2-yn-1-ylium 59 to produce 60a–c. Finally, compounds 60a–c were reacted with substituted azides 61 through click-chemistry under microwave irradiation to afford the desired compounds (62a–e′), as shown in Fig. 7. The synthesized compounds were evaluated against the 3D7 strain of P. falciparum, leading to three hits, 62a, 62h, and 62u, with IC50 values of 900 nM, 900 nM, and 700 nM, respectively. Likewise, these analogs, 62a, 62h, and 62u, were also tested against the CQ-resistant W2 strain and exhibited IC50 values of 700 nM, 1300 nM, and 900 nM, respectively. It was observed that the Pht derivatives 62a and 62u inhibited the ring-stage growth of the parasite and parasite maturation. Further, to identify possible partner candidates to fight against developing resistance against current antimalarial therapies, 62a, 62h, and 62u were tested as combination agents with CQ and DHA.

Fig. 7. The synthesis of Pht–benzimidazole–triazole analogs (62a–e′). The various substituents used in the compounds (62a–e′) take the form of the various R groups shown in the inset table.

A combination study indicated that all three analogs showed a synergistic effect with CQ and DHA against both 3D7 and W2 Plasmodium strains. Cytotoxicity evaluations showed that 62h was the least toxic, with a CC50 value of 28.82 μM against the U937 cell line. In addition, animal experiments were conducted with 62h and 62u using mice infected with the P. berghei NK65 strain, and the results indicated that the administration of both analogs, either alone or in combination with DHA, was successful in reducing the parasite load. To sum up, extensive structure–activity relationship studies revealed that a large alkyl group in the R1 position, such as isobutyl or sec-butyl in the case of 62a, 62h, and 62u, increases the potency, whereas analogs with the absence of a functional group in the R2 position (62u) were observed to show the highest potency against the 3D7 strain of the Plasmodium parasite. Pharmacokinetics studies and parasite target site identification using these Pht compounds can contribute to the development of potential antimalarial candidates.

3.8. Quinoline–isoniazid–Pht analogs

Recently, Kumar et al.69 designed and synthesized a library of quinoline–isoniazid–Pht triad based analogs and evaluated their antiplasmodial efficacy. Quinoline remains one of the essential chemical component of several drugs like amodiaquine, CQ, MQ, PPQ, PQ, and quinine.70 Similarly, the authors selected isoniazid considering its application as a first-line treatment for tuberculosis (TB).71 The synthesis of the precursors (66a–e) was accomplished using microwave irradiation at 150 °C for 5 min via treating a substituted Pht anhydride (63) with 4-aminoquinoline-diamines (64), as illustrated in Fig. 8A. The obtained compounds were further coupled with isoniazid (65) to afford the first set of quinoline–isoniazid–Pht triads (67a–e). The second set of triads (69a–g) was also obtained following a similar synthetic route; firstly, a substituted Pht anhydride (63) was reacted with isoniazid (65) to afford the intermediate (68), which was further coupled via the formation of several amide/ester bonds to afford the desired set of triads (Fig. 8B). The authors also synthesized a piperazyl analogue (73) and isoniazid–Pht analogs (76a–b) in order to study the influence of the flexible alkyl chain and quinoline core on the antiplasmodial activity. The synthetic pathways followed for the synthesis of 73 and 76a–b are presented in Fig. 8C and D.

Fig. 8. The synthetic routes and structures of: A) a set of quinoline–isoniazid–Pht analogs (67a–e); B) another set of quinoline–isoniazid–Pht analogs (69a–g); C) piperazinyl analogs (73); and D) isoniazid–Pht analogs (76a–b).

Next, the compounds were evaluated for their biological activity and cytotoxicity. Detailed SAR analysis revealed that 69d (n = 6) was the most potent compound in the series, displaying an IC50 value of 11 nM against the W2 strain of P. falciparum. The second set of triads (Fig. 8B) possessing an amide linkage (69a–e) and ester linkage (69f–g) showed 50% inhibition at 811 nM (69f) and 3773 nM (69g). This indicated the significance of the amide linkage compared to the ester linkage. However, the piperazyl analogs (73) and isoniazid–Pht analogs (76a–b) did not show any significant inhibition, thus highlighting the importance of the quinoline–isoniazid–Pht triad for obtaining potent antiplasmodial activity. In addition, the authors have described mechanistic insights into the potent hit compound 69d, and it was reported that the interaction of 69d with heme was better compared to CQ. Altogether, compound 69d showed significant in vitro antiplasmodial activity and it could act as a lead compound for the further development of therapeutics provided it maintains its potency in animal models without showing any cytotoxicity.

4. Conclusions and future aspects

Inevitable resistance to frontline treatments demands the effective and rapid discovery of novel, safe, and effective antimalarials. Although antimalarial drug discovery has attained significant attention, other more recent viral infections have attracted the interest of academia and industry; in turn, no effective antimalarial drugs have appeared on the market since 1996. TO change this, Pht-based compounds appear to be one of the most important leads, showing safe and effective antiplasmodial activity. Pht compounds offer easy and convenient synthesis strategies, favorable pharmacological effects, and antiplasmodial efficacy against multiple stages of the malaria parasite. Various literature reports discussed in this short review suggest that Pht compounds can demonstrate therapeutic and pharmaceutical applications and thus act as lead points for the design of novel drug candidates. A few Pht analogs have shown that this moiety can act as a precursor for the further exploration of similar compounds that are effective against various strains of P. falciparum, revealing multistage antiplasmodial activity. Of particular note, the multistage antiplasmodial efficacy exhibited by Pht analogs suggests that they are valuable synthons. The inclusion of other heterocyclic moieties, alkyl chains, amino acids, and fluoro/trifluoromethyl groups might also partly be a factor. Additionally, amino acid linkers, like leucine and phenylalanine, and piperazine cores in Pht analogs could contribute to the significant biological results. To a large degree, Pht analogs involving high-value scaffolds could emerge as potential candidates to combat malaria. Extensive combination studies involving ACT and other approved drugs may deliver a broad understanding of the potency and suitability of Pht compounds.

In this review, several Pht analogs with potent antiplasmodial activity have been discussed in detail, however, their mechanisms of action remain unclear. Additional studies focusing on target identification and validation, molecular mechanisms, and resistance evolution are essential to boost the potential of these analogs as potent therapeutic candidates for clinical application against malaria.

Abbreviations

- WHO

World Health Organization

- Pht

Phthalimide

- Plm

Plasmepsin

- CQ

Chloroquine

- HCQ

Hydroxychloroquine

- PQ

Primaquine

- AQ

Atovaquone

- PPQ

Piperaquine

- DHA

Dihydroartemisinin

- LUM

Lumefantrine

- MQ

Mefloquine

- MM

Multiple myeloma

- HEA

Hydroxyethylamine

- CC50

Cytotoxic concentration

- EC50

Effective concentration

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- U937

Leukemic monocytic cell line

- IC50

Inhibitory concentration

- nM

Nanomolar

- μM

Micromolar

- HepG2

Liver hepatocellular carcinoma cell line

- ART

Artemisinin

- h

Hour

- TI

Therapeutic index

- SI

Selectivity index

Conflicts of interest

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Science & Engineering Research Board (SERB) under the core research grant scheme (CRG/2020/005800) to BR and Poonam. MB and CU receive senior research fellowships from ICMR and CSIR, respectively.

Biographies

Biography

Meenakshi Bansal.

Meenakshi Bansal is a doctoral student working under the joint supervision of Dr. Sumit Kumar and Dr. Brijesh Rathi. She received her bachelor's degree (2015) in biochemistry and master's degree (2017) in chemistry from CCS University, Meerut. Her current research projects are focused on medicinal chemistry and drug discovery relating to parasitic diseases and are supported by ICMR.

Biography

Charu Upadhyay.

Charu Upadhyay obtained her bachelor's degree in general chemistry in 2013 and post-graduate degree in organic chemistry in 2015 from Kumaun University, Nainital, Uttarakhand. Currently, she is working as a research scholar in Dr Poonam's research group at Miranda House University of Delhi. She is a recipient of a CSIR-Junior Research Fellowship.

Biography

Poonam.

Dr. Poonam is an Assistant Professor of Chemistry at Miranda House, University of Delhi, India. She has contributed to ∼30 peer-reviewed research/review articles, two book chapters, and a number of patents. Currently, Dr. Poonam is leading a research group of several doctoral students and trainees, with their research work focused on medicinal, bioorganic, and materials chemistry. She has been a recipient of the prestigious “Distinguished Investigator Award” at the International Conference, ICBTM-2019, a UGC Travel Grant Award, a CSIR-Senior Research Fellowship, and a UGC-Science Meritorious Fellowship sponsored by Government of India.

Biography

Sumit Kumar.

Dr. Sumit Kumar obtained his PhD from University of Delhi, Delhi, India and did his post-doctorate work with the Prof. Haag Group at Free University, Berlin and Prof Parang at Chapman University, USA. Dr Kumar has been working as an assistant professor at DCRUST, Murthal in biomedicinal chemistry since 2010. During this time, he has published, reviewed, and edited papers for various journals. His research has been published in more than 26 research articles, reviews of high impact, and one book chapter, and it has been recognized with several awards and grants since 2010.

Biography

Brijesh Rathi.

Dr. Brijesh Rathi was born in a small village, Guthawali Khurd of Bulandshahr district, Uttar Pradesh. Dr Rathi obtained doctoral degree in chemistry from University of Delhi and he is now working as an Assistant Professor of Chemistry at Hansraj College, University of Delhi, India. He is a recipient of the Young Scientist Project Fellowship; an Early Career Research Award; a UGC-Raman Fellowship from the Government of India; a CAPES-Print Fellowship from the Ministry of Education, Brazil; and the prestigious Excellence Awards for In Service Teachers from University of Delhi. Dr. Rathi was a Visiting Assistant Professor at the Department of Chemistry, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA, and is now an Affiliate Professor at the University of Loyola Chicago and University of Debrecen, Hungary. Dr. Rathi holds the position of section editor for Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry, is an associate editor of Chemical Biology Letters, and has been an international reviewer for the Russian Science Foundation from 2017 onwards. Dr. Rathi leads a research group of doctoral and master students in different science streams. He has published more than 80 papers in various journals. Antiparasitic drug discovery is the primary area of his ongoing research.

References

- Mota M. M. Mello-Vieira J. Curr. Biol. 2019;29:R632–R634. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okiring J. Olwoch P. Kakuru A. Okou J. Ochokoru H. Ochieng T. A. Kajubi R. Kamya M. R. Dorsey G. Tusting L. S. Malar. J. 2019;18:144. doi: 10.1186/s12936-019-2779-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. Rogerson S. Microbiol. Aust. 2016;37:34–38. doi: 10.1071/MA16013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira M. U. Castro M. C. Malar. J. 2016;15:284. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1335-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K. L. Flanagan K. L. Prakash M. D. Plebanski M. Expert Rev. Vaccines. 2019;18:133–151. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2019.1561289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyoga S. Macharia A. W. Ndila C. M. Nyutu G. Shebe M. Awuondo K. O. Mturi N. Peshu N. Tsofa B. Scott J. A. G. Maitland K. Williams T. N. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:856. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08775-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization: World malaria report 2020, (https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015791), Accessed March 22, 2021

- McLean K. J. Straimer J. Hopp C. S. Vega-Rodriguez J. Small-Saunders J. L. Kanatani S. Tripathi A. Mlambo G. Dumoulin P. C. Harris C. T. Tong X. Shears M. J. Ankarklev J. Kafsack B. F. C. Fidock D. A. Sinnis P. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:13131. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49348-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross L. S. Fidock D. A. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;26:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Z.-N. Wu Z.-X. Dong S. Yang D.-H. Zhang L. Ke Z. Zou C. Chen Z.-S. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020;216:107672. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harinasuta T. Suntharasamai P. Viravan C. J. L. Lancet. 1965:657–660. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(65)90395-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatoon L. Baliraine F. N. Bonizzoni M. Malik S. A. Yan G. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009;81:525. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.81.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther G. J. Hillesland H. K. Keyloun K. R. Reid M. C. Lafuente-Monasterio M. J. Ghidelli-Disse S. Leonard S. E. He P. Jones J. C. Krahn M. M. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wangchuk S. Drukpa T. Penjor K. Peldon T. Dorjey Y. Dorji K. Chhetri V. Trimarsanto H. To S. Murphy A. von Seidlein L. Price R. N. Thriemer K. Auburn S. Malar. J. 2016;15:277. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1320-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman R. T. Fidock D. A. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:864–874. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poonam Gupta Y. Gupta N. Singh S. Wu L. Chhikara B. S. Rawat M. Rathi B. Med. Res. Rev. 2018;38:1511–1535. doi: 10.1002/med.21486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N. Kashif M. Singh V. Fontinha D. Mukherjee B. Kumar D. Singh S. Prudencio M. Singh A. P. Rathi B. J. Med. Chem. 2021;64:8666–8683. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c00659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. El-Sakkary N. Skinner D. E. Sharma P. P. Ottilie S. Antonova-Koch Y. Kumar P. Winzeler E. Poonam Caffrey C. R. Rathi B. Pharmaceuticals. 2020;13:25. doi: 10.3390/ph13020025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima L. A. C. Pontes E. J. W. de Oliveira C. M. V. de Oliveira F. G. B. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019;26:4323–4354. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666171023163752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phatak P. S. Bakale R. D. Dhumal S. T. Dahiwade L. K. Choudhari P. B. Siva Krishna V. Sriram D. Haval K. P. Synth. Commun. 2019;49:2017–2028. doi: 10.1080/00397911.2019.1614630. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdani S. S. Khan B. A. Hameed S. Batool F. Saleem H. N. Mughal E. U. Saeed M. Bioorg. Chem. 2020;96:103567. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J. Cheng C. Zhao X. Liu Q. Yang P. Wang Y. Luo G. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010;45:1731–1738. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asatsuma-Okumura T. Ando H. De Simone M. Yamamoto J. Sato T. Shimizu N. Asakawa K. Yamaguchi Y. Ito T. Guerrini L. Handa H. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2019;15:1077–1084. doi: 10.1038/s41589-019-0366-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asatsuma-Okumura T. Ito T. Handa H. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019;202:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2019.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soekojo C. Y. Kim K. Huang S.-Y. Chim C.-S. Takezako N. Asaoku H. Kimura H. Kosugi H. Sakamoto J. Gopalakrishnan S. K. Nagarajan C. Wei Y. Moorakonda R. Lee S. L. Lee J. J. Yoon S.-S. Kim J. S. Min C. K. Lee J.-H. Durie B. Chng W. J. Blood Cancer J. 2019;9:83. doi: 10.1038/s41408-019-0245-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muniz-Junqueira M. I. Silva F. O. de Paula-Júnior M. R. Tosta C. E. Acta Trop. 2005;94:128–138. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dooren G. G. Marti M. Tonkin C. J. Stimmler L. M. Cowman A. F. McFadden G. I. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;57:405–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florens L. Washburn M. P. Raine J. D. Anthony R. M. Grainger M. Haynes J. D. Moch J. K. Muster N. Sacci J. B. Tabb D. L. Witney A. A. Wolters D. Wu Y. Gardner M. J. Holder A. A. Sinden R. E. Yates J. R. Carucci D. J. Nature. 2002;419:520–526. doi: 10.1038/nature01107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay C. Chaudhary M. De Oliveira R. N. Borbas A. Kempaiah P. Poonam Rathi B. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery. 2020;15:705–718. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2020.1740203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N. Verma A. Fnu P. Kempaiah P. Rathi B. Chem. Biol. Lett. 2019;6:14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen E. McMillan P. J. Tilley L. Int. J. Parasitol. 2010;40:1127–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulard V. Bosson-Vanga H. Lorthiois A. Roucher C. Franetich J.-F. Zanghi G. Bordessoulles M. Tefit M. Thellier M. Morosan S. Le Naour G. Capron F. Suemizu H. Snounou G. Moreno-Sabater A. Mazier D. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7690. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snigdha S. Neha S. Charu U. Sumit K. Brijesh R. Poonam Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2018;18:2008–2021. [Google Scholar]

- Verbaanderd C. Maes H. Schaaf M. B. Sukhatme V. P. Pantziarka P. Sukhatme V. Agostinis P. Bouche G. Ecancermedicalscience. 2017;11:781. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2017.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzo C. Gareri P. Castagna A. Drug Saf. Case Rep. 2017;4:6. doi: 10.1007/s40800-017-0048-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurya S. S. Khan S. I. Bahuguna A. Kumar D. Rawat D. S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;129:175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma B. Kaur S. Legac J. Rosenthal P. J. Kumar V. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020;30:126810. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.126810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani A. Singh A. Gut J. Rosenthal P. J. Kumar V. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;143:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X. Liu X. Shan W. Liu Q. Wang C. Zheng J. Yao H. Tang R. Zheng J. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2018;8:1697. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David Hong W. Leung S. C. Amporndanai K. Davies J. Priestley R. S. Nixon G. L. Berry N. G. Samar Hasnain S. Antonyuk S. Ward S. A. Biagini G. A. O'Neill P. M. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018;9:1205–1210. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Hage S. Ane M. Stigliani J.-L. Marjorie M. Vial H. Baziard-Mouysset G. Payard M. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009;44:4778–4782. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham M. Gagaring K. Martino M. L. Vanaerschot M. Plouffe D. M. Calla J. Godinez-Macias K. P. Du A. Y. Wree M. Antonova-Koch Y. Eribez K. Luth M. R. Ottilie S. Fidock D. A. McNamara C. W. Winzeler E. A. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020;6:613–628. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.9b00482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada-Junior C. Y. Monteiro G. C. Aguiar A. C. C. Batista V. S. de Souza J. O. Souza G. E. Bueno R. V. Oliva G. Nascimento-Júnior N. M. Guido R. V. C. Bolzani V. S. ACS Omega. 2018;3:9424–9430. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.8b01062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison E. K. Brimble M. A. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019;52:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roa-Linares V. C. Brand Y. M. Agudelo-Gomez L. S. Tangarife-Castaño V. Betancur-Galvis L. A. Gallego-Gomez J. C. González M. A. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016;108:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi S. Zimmermann S. Zaugg J. Smiesko M. Brun R. Hamburger M. Planta Med. 2013;79:150–156. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1328063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samoylenko V. Dunbar D. C. Gafur M. A. Khan S. I. Ross S. A. Mossa J. S. El-Feraly F. S. Tekwani B. L. Bosselaers J. Muhammad I. Phytother. Res. 2008;22:1570–1576. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch A. Orjala J. Mutiso P. Soejarto D. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2006;34:270–272. doi: 10.1016/j.bse.2005.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- González M. A. Clark J. Connelly M. Rivas F. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;24:5234–5237. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long T. E. Lu X. Galizzi M. Docampo R. Gut J. Rosenthal P. J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:2976–2979. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.02.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millard M. Pathania D. Shabaik Y. Taheri L. Deng J. Neamati N. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13131. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. A. J. Murphy M. P. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010;1201:96–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque-Ortega J. R. Reuther P. Rivas L. Dardonville C. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:1788–1798. doi: 10.1021/jm901677h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndakala A. J. Gessner R. K. Gitari P. W. October N. White K. L. Hudson A. Fakorede F. Shackleford D. M. Kaiser M. Yeates C. Charman S. A. Chibale K. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:4581–4589. doi: 10.1021/jm200227r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza A. Pérez-Silanes S. Quiliano M. Pabón A. Galiano S. González G. Garavito G. Zimic M. Vaisberg A. Aldana I. Monge A. Deharo E. Exp. Parasitol. 2011;128:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2011.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A. K. Rajendran V. Pant A. Ghosh P. C. Singh N. Latha N. Garg S. Pandey K. C. Singh B. K. Rathi B. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015;23:1817–1827. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijwali P. S. Rosenthal P. J. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:4384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307720101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velcicky J. Mathison C. J. N. Nikulin V. Pflieger D. Epple R. Azimioara M. Cow C. Michellys P.-Y. Rigollier P. Beisner D. R. Bodendorf U. Guerini D. Liu B. Wen B. Zaharevitz S. Brandl T. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019;10:887–892. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. Sharma P. P. Shankar U. Kumar D. Joshi S. K. Pena L. Durvasula R. Kumar A. Kempaiah P. Poonam Rathi B. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020;60:5754–5770. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trabocchi A., in Small Molecule Drug Discovery, ed. A. Trabocchi and E. Lenci, Elsevier, 2020, pp. 163–195 [Google Scholar]

- Ciana C.-L. Siegrist R. Aissaoui H. Marx L. Racine S. Meyer S. Binkert C. de Kanter R. Fischli C. Wittlin S. Boss C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;23:658–662. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.11.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conceicao de S. M. Triciana G.-S. Marcele M. Claudia R. B. G. Roland K. C. das Gracas Muller de Oliveira H. M. Marcus V. N. D. S. Med. Chem. 2012;8:266–272. doi: 10.2174/157340612800493638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A. K. Rathore S. Tang Y. Goldfarb N. E. Dunn B. M. Rajendran V. Ghosh P. C. Singh N. Latha N. Singh B. K. Rawat M. Rathi B. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A. Rajendran V. Singh S. Kumar P. Kumar Y. Singh A. Miller W. Potemkin V. Poonam Grishina M. Gupta N. Kempaiah P. Durvasula R. Singh B. K. Dunn B. M. Rathi B. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018;26:3837–3844. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. Rajendran V. He J. Singh A. K. Achieng A. O. Vandana Pant A. Nasamu A. S. Pandit M. Singh J. Quadiri A. Gupta N. Poonam Ghosh P. C. Singh B. K. Narayanan L. Kempaiah P. Chandra R. Dunn B. M. Pandey K. C. Goldberg D. E. Singh A. P. Rathi B. ACS Infect. Dis. 2019;5:184–198. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lentz C. S. Sattler J. M. Fendler M. Gottwalt S. Halls V. S. Strassel S. Arriens S. Hannam J. S. Specht S. Famulok M. Mueller A.-K. Hoerauf A. Pfarr K. M. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015;59:654. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02383-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devender N. Gunjan S. Chhabra S. Singh K. Pasam V. R. Shukla S. K. Sharma A. Jaiswal S. Singh S. K. Kumar Y. Lal J. Trivedi A. K. Tripathi R. Tripathi R. P. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016;109:187–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P. Achieng A. O. Rajendran V. Ghosh P. C. Singh B. K. Rawat M. Perkins D. J. Kempaiah P. Rathi B. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:6724. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06097-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani A. Sharma A. Legac J. Rosenthal P. J. Singh P. Kumar V. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021;39:116159. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beteck R. M. Smit F. J. Haynes R. K. N'Da D. D. Malar. J. 2014;13:339. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In Meyler's Side Effects of Drugs, ed. J. K. Aronson, Elsevier, Oxford, 16th edn, 2016, pp. 341–350 [Google Scholar]