Abstract

The Egr family of zinc finger transcription factors, whose members are encoded by Egr1 (NGFI-A), Egr2 (Krox20), Egr3, and Egr4 (NGFI-C) regulate critical genetic programs involved in cellular growth, differentiation, and function. Egr1 regulates luteinizing hormone beta subunit (LHβ) gene expression in the pituitary gland. Due to decreased levels of LHβ, female Egr1-deficient mice are anovulatory, have low levels of progesterone, and are infertile. By contrast, male mutant mice show no identifiable defects in spermatogenesis, testosterone synthesis, or fertility. Here, we have shown that serum LH levels in male Egr1-deficient mice are adequate for maintenance of Leydig cell steroidogenesis and fertility because of partial functional redundancy with the closely related transcription factor Egr4. Egr4-Egr1 double mutant male mice had low steady-state levels of serum LH, physiologically low serum levels of testosterone, and atrophy of androgen-dependent organs that were not present in either Egr1- or Egr4-deficient males. In double mutant male mice, atrophic androgen-dependent organs and Leydig cell steroidogenesis were fully restored by administration of exogenous testosterone or human chorionic gonadotropin (an LH receptor agonist), respectively. Moreover, a normal distribution of gonadotropin-releasing hormone-containing neurons and normal innervation of the median eminence in the hypothalamus, as well as decreased levels of LH gene expression in Egr4-Egr1-relative to Egr1-deficient male mice, indicates a defect of LH regulation in pituitary gonadotropes. These results elucidate a novel level of redundancy between Egr4 and Egr1 in regulating LH production in male mice.

Mammalian reproductive capacity is regulated by hormonal influences that coordinate germ cell maturation and steroidogenesis. The gonadotropins, luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), are the principle hormones produced by gonadotropes in the pituitary gland that control the feed-forward regulatory pathways involved in male and female gonadal function and development. LH and FSH are heterodimeric glycoproteins composed of a common α subunit and distinct β subunits. Expression of the α and β subunits, as well as secretion of the heterodimeric proteins, is controlled by gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) secreted by the hypothalamus (for a review, see reference 4). Comparatively little is understood about the intrinsic molecular mechanisms involved in regulating the production and release of gonadotropins by the pituitary gland. However, we have previously demonstrated that the zinc-finger transcription factor Egr1 is essential for regulating LHβ gene expression since Egr1-deficient mice have low levels of LHβ in the pituitary and low levels of LH in serum (5). In vitro studies have further established that the expression of Egr1 is coupled to intracellular signal transduction pathways that are specifically engaged by GnRH receptor activation (20). Thus, Egr1-mediated transcription provides an essential molecular link between GnRH receptor activation and transcriptional regulation of the LHβ gene within pituitary gonadotropes.

The Egr family of transcription factors consists of four closely related proteins encoded by Egr1 (NGFI-A, krox24, and zif-268), Egr2 (Krox20), Egr3, and Egr4 (NGFI-C and pAT133). A defining feature of the Egr family is a highly conserved DNA-binding domain composed of three zinc finger motifs that bind a 9-bp response element within gene promoter regions to facilitate transcriptional activation (for a review, see reference 10). Gene targeting experiments in mice have revealed essential functions of Egr transcription factors in a variety of developmental processes. For example, in two independent gene-targeting experiments, Egr1 has been shown to play a critical role in regulating the LHβ gene in the pituitary (5, 16), and in one mouse strain, this appears to primarily effect female fertility (5). In addition, Egr2 plays a critical role in hindbrain development (11, 13) and peripheral nerve myelination (15), whereas Egr3 is essential for muscle spindle morphogenesis and normal proprioception in mice (18). Finally, male but not female mice deficient in Egr4 are infertile due to a defect in male germ cell maturation (19). Thus, Egr1 and Egr4 have sexually dimorphic functions in female and male fertility, respectively, and primarily function at different levels of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis.

Egr transcription factors are coexpressed in many different tissues, suggesting that they may have some redundant functions. In the mutant mice generated in our laboratory, Egr1 is essential to maintain adequate LHβ expression in female pituitaries whereas in males, its absence leads only to a moderate decrease that is not sufficient to disrupt Leydig cell steroidogenesis or fertility (5). This observation suggests that additional regulatory mechanisms may functionally compensate for Egr1 in order to maintain moderate but physiologically sufficient levels of LH in males. Indeed, recent studies using a GnRH-responsive gonadotrope cell line have shown that both Egr1 and Egr4 induction are strongly coupled to receptor activation (3). Moreover, this appears to be a specific feature of Egr1 and Egr4, as levels of Egr2 and Egr3 were not appreciably coupled to GnRH receptor activation in two different stimulation paradigms (3).

To examine whether Egr4 can compensate for Egr1 in regulating LH in males, we generated Egr1 (5) and Egr4 (19) double mutant mice. In this report, we demonstrate that male mice deficient in both Egr4 and Egr1 have quantitatively lower levels of LHβ gene expression than either single gene mutant, low steady-state levels of serum LH, and physiologically low serum levels of testosterone. Consequently, in double mutant male mice, androgen-dependent organs are markedly atrophic and spermatogenesis is completely disrupted. Administration of either human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (an LH receptor [LHr] agonist) or testosterone results in the restoration of androgen-dependent organs to their normal size. These results clearly demonstrate that low androgen synthesis in double mutant male mice is an indirect consequence of low LH. Thus, male mice with impaired function of Egr1 can maintain adequate levels of LH and spermatogenesis due to a partially redundant transcriptional regulatory capacity mediated by Egr4.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Egr mutant mouse strains.

Egr4 and Egr1 mutant mouse strains maintained on a C57BL/6-129/SvJ hybrid genetic background were mated to obtain double Egr4-Egr1 homozygous mutant mice. The design of the mutant alleles and phenotypic characterization of the resulting single homozygous mutant mice have been previously described (5, 19).

Histology and immunohistochemistry.

Mice were deeply anesthetized (with ketamine [87 mg/kg of body weight] and xylazine [13 mg/kg], both administered intraperitoneally [i.p.]), subjected to transcardiac perfusion with 4% phosphate-buffered paraformaldehyde (pH = 7.4), and for microscopic sections, the tissues were processed in paraffin using standard methods. Immunohistochemistry for GnRH using the monoclonal antibody LR-1 (a generous gift from Robert Benoit, Montreal General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec, Canada) was performed using standard immunoperoxidase procedures. Serial sections spanning the entire rostral-caudal extent of the hypothalamus were obtained and processed for GnRH immunohistochemistry. Tissue sections from wild-type, Egr1, Egr4, and Egr4-Egr1 mutant mice were examined to compare the distribution and number of GnRH-positive neurons in the hypothalamus. All procedures were approved by the Animal Studies Committee of Washington University, Northwestern University, and the National Institutes of Health.

Gene expression analysis.

Pituitary gene expression was performed using 10% of the RNA isolated from total gland lysates. The samples were subjected to reverse transcription (RT) and the resulting cDNA was normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase using semiquantitative PCR by cycling in a logarithmic range of amplification (semiquantitative RT-PCR). Testicular gene expression analysis was performed using semiquantitative RT-PCR on 5% of the RNA obtained from each testis regardless of its size. Thus, the amount of RNA in each RT reaction was closely correlated with the testicular weight. Since there was marked germ cell loss in both Egr4 and Egr4-Egr1 mutant testes, this method was preferred in order to compare gene expression for an entire testis. By contrast, samples normalized to the total amount of RNA (or to a reference gene) would skew the representation of RNA in favor of cells that were not affected by the mutation. Since it is known that a specific cell population is lost in Egr4 mutant testis (i.e., early-mid-pachytene spermatocytes [19]), the unskewed RNA representation was preferred to more accurately determine relative gene expression in the remaining cells (i.e., in the entire testis). The gene expression comparisons were performed using RT-PCR on samples obtained by pooling RNA from the testes of three animals of each genotype. The cDNA samples were amplified by PCR with gene-specific primers at cycle numbers corresponding to the logarithmic phase of amplification (15 to 21 cycles) and Southern blotted using the amplified products as probes. The amplification products were quantified on a phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics), and the results were expressed as changes relative to the wild-type values.

Serum RIA.

Mice were housed and bred in a barrier facility with a 12-h light-dark cycle. For LH and FSH quantification, serum from adult male mice (>10 weeks and <35 weeks of age) were obtained at random times during the day from wild-type, Egr4, Egr1, and Egr4-Egr1-deficient mice (n = 6, each genotype). Radioimmunoassay (RIA) was performed using standardized murine reagents obtained from the National Hormone and Pituitary Program sponsored by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture according to suggested protocols. Serum samples were obtained from adult male mice at random times during the day from wild-type (n = 10), Egr4, Egr1, and Egr4-Egr1 mutant mice (n = 6, each genotype) for serum testosterone assay. Free serum testosterone levels were determined using a Coat-A-Count kit (Diagnostic Products Corporation, Los Angeles, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Exogenous hormone manipulation.

To examine Leydig cell steroidogenic capacity and end-organ androgen sensitivity, Egr4-Egr1 double mutant male mice received daily i.p. injections of either hCG (0.005 IU/kg/of body weight/day for 17 days; Sigma) or testosterone propionate (25 mg/kg/day for 29 days; Sigma), respectively.

RESULTS

Phenotypic characterization of Egr4-Egr1 double homozygous mutant mice.

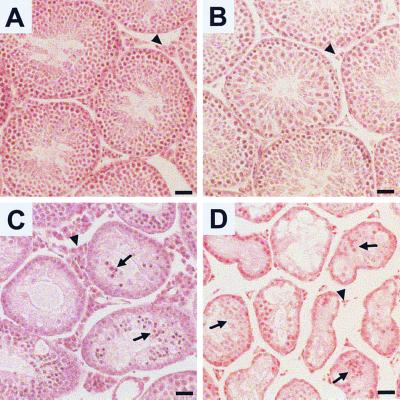

Egr4-Egr1 double homozygous mutant mice were born at the expected frequency and showed no developmental dysmorphisms or behavioral abnormalities. However, they weighed consistently less than wild-type mice (wild type, 30.3 ± 1.8 g; Egr4-Egr1 double mutant, 24.2 ± 0.4 g [n = 6, each genotype; Student's t test, P < 0.01]) (unless otherwise noted, values are reported as means ± standard deviations). By contrast, both Egr4 and Egr1 single homozygous mutant mice weighed similar to wild-type mice (n = 6; single factor analysis of variance, P = 0.58). As expected, test matings demonstrated that both male and female Egr4-Egr1-deficient mice were infertile. Gross and histological examination of the female genitourinary system showed only changes that have been previously identified in Egr1-deficient females (anovulatory ovaries and atrophic uteri) (5). In adult male mice (>10 weeks of age), the weights of Egr1-deficient testes were similar to those for wild-type mice (wild type [n = 10], 116 ± 4 mg; Egr1-deficient [n = 10], 119.1 ± 4.1 mg [Student's t test, P = 0.6]), Egr4-deficient testes were 43% of wild-type weights (wild type [n = 63] 96.4 ± 1.7 mg; Egr4 null [n = 37], 41.9 ± 2.3 mg [Student's t test, P < 0.001]), and Egr4-Egr1-deficient testes were 25% of wild-type weights (Egr4-Egr1 [n = 10], 24.0 ± 2.3 mg [Student's t test, P < 0.001]). The testicular weight changes correlated well with decreased germ cell viability during spermatogenesis (Fig. 1). Compared to wild-type testes (Fig. 1A), Egr1-deficient testes showed no histopathological abnormalities with the exception of Leydig cell atrophy (Fig. 1B). Egr4-deficient testes showed marked germ cell apoptosis (Fig. 1C) and Leydig cell hyperplasia (Fig. 1C) as previously described (19). However, Egr4-Egr1-deficient testis showed markedly small-caliber seminiferous tubules, nearly absent germ cells, scant germ cell apoptosis, prominent intratubular Sertoli cell aggregation (Fig. 1D) and marked Leydig cell atrophy (Fig. 1D).

FIG. 1.

Histopathology of Egr-deficient testes. (A) Adult wild-type testes contain seminiferous tubules filled with maturing germ cells. The steroid-producing Leydig cells (arrowhead) are located in the interstitial spaces between the tubules. (B) In testes from Egr1-deficient mice, spermatogenesis proceeds normally. However, Leydig cells (arrowhead) are notably atrophic. (C) The testes from adult Egr4-deficient mice show marked disruption of spermatogenesis, high levels of germ cell apoptosis (arrow), and marked Leydig cell hyperplasia (arrowhead). (D) The testes from adult Egr4-Egr1-deficient mice contain small atrophic seminiferous tubules filled with very few maturing germ cells. The majority of cells within the seminiferous tubules consist of aggregated Sertoli cells (arrows). Leydig cells are markedly atrophic (arrowhead). (Bar = 50 μm.)

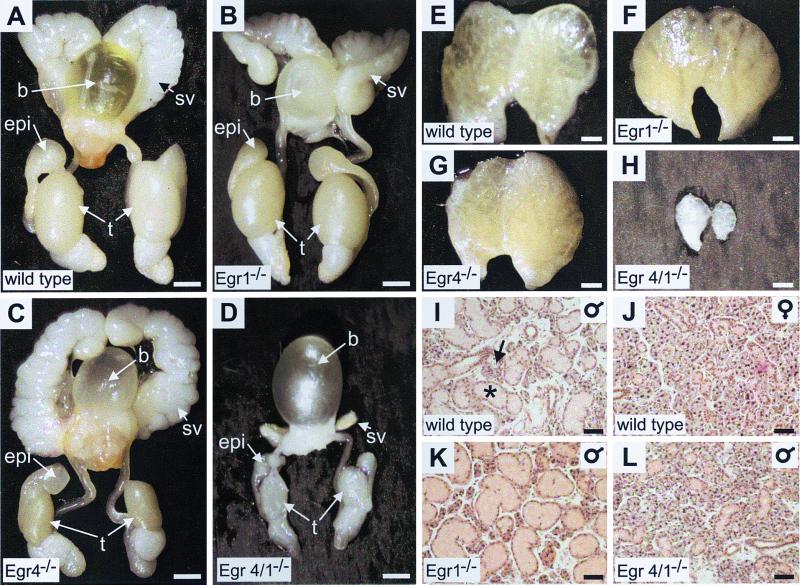

Except for the fact that Egr4-deficient mice had small testes due to ineffective spermatogenesis (Fig. 2C), androgen-dependent organs in wild-type (Fig. 2A, E, and I), Egr1-deficient (Fig. 2B, F, and K), and Egr4-deficient (Fig. 2C and G) mice had no gross abnormalities. However, adult Egr4-Egr1-deficient male mice (Fig. 2D, H, and L) showed features consistent with androgen insufficiency. The androgen-dependent seminal vesicles, prostate, epididymis, testes (Fig. 2D), and preputial pheromone gland (Fig. 2H) were markedly atrophic. The androgen-sensitive and sexually dimorphic submaxillary gland was also affected. The seromucinous submaxillary gland consists of a mixture of serous (Fig. 2I) and mucinous (Fig. 2I) acini. In mice, the serous component of the gland is androgen sensitive (7); thus, in males it is prominent, whereas in females it is atrophic due to the low levels of circulating androgens (compare Fig. 2I [wild-type male] to Fig. 2J [wild type female]). The submaxillary gland had a normal histological appearance in both Egr4- and Egr1-deficient male mice (compare Fig. 2K and I), but in double mutant males it was histologically indistinguishable from the wild-type female gland (compare Fig. 2L and J). These results strongly indicated either a deficiency in androgen synthesis or androgen insensitivity.

FIG. 2.

Egr4-Egr1-deficient mice have an androgen insufficiency phenotype that is not present in mice deficient in either single gene. Phenotypic analysis of androgen-dependent organs in the adult genitourinary system (A to D), preputial pheromone gland (E to H), and submaxillary gland (I to L) are shown. (B and F) In Egr1-deficient mice, seminal vesicles, epididymis, prostate, and preputial glands are similar to adult wild-type organs (A and E). (C) In adult Egr4-deficient mice, only the testes weighed less (43% of wild-type weight) due to disrupted spermatogenesis as has been previously described (19). Other androgen-dependent organs, including seminal vesicles (C), epididymis, prostate, and preputial glands (G) are similar to wild-type organs (A and E). However, in Egr4-Egr1-deficient mice, the testes weighed 24% of the wild-type weight and the seminal vesicles (D), prostate, epididymis, and preputial gland (H) were markedly atrophic. (I to L) In mice, the seromucinous submaxillary gland has a sexually dimorphic glandular architecture with a serous component that is androgen dependent. Thus, the morphology of the submaxillary gland is related to serum testosterone levels such that wild type male glands (I) have a prominent serous (asterisk) and less prominent mucinous (arrow) component, whereas in wild-type females (J), the serous component is atrophic due to low circulating levels of androgens. Adult male Egr1- or Egr4-deficient mice (K) (latter not shown) had a glandular architecture similar to that of wild-type males (I). However, Egr4-Egr1-deficient adult male mice (L) had a glandular architecture indistinguishable from that of wild-type females (J), consistent with low serum androgen levels. (A to E, bar = 2.5 mm; E to H, bar = 1 mm; I to L, bar = 100 μm).

Male Egr4-Egr1-deficient androgen-dependent organs and testicular leydig cells respond to exogenous testosterone and LH administration.

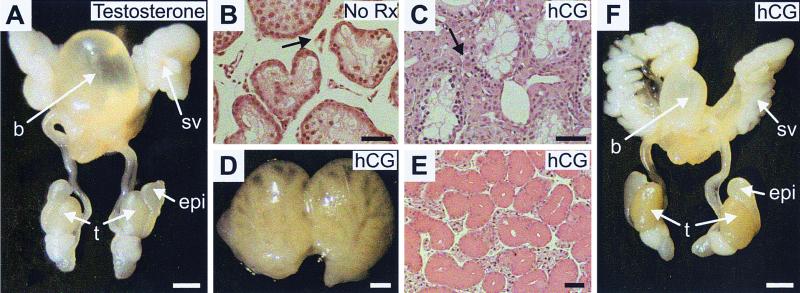

To determine whether the androgen insufficiency phenotype resulted from androgen insensitivity, male double mutant mice received daily injections of testosterone (29 days). Testosterone administration restored the androgen-dependent organs (seminal vesicles, epididymis, prostate, preputial gland, and submaxillary gland) to the wild type size (Fig. 3A and data not shown). However, there was no effect on the testicular size (Fig. 3A) or spermatogenesis (not shown).

FIG. 3.

Competent androgen responsiveness and Leydig cell steroidogenesis in Egr4-Egr1-deficient male mice. (A) In adult male Egr4-Egr1-deficient mice, testosterone treatment is capable of restoring the seminal vesicles, prostate, and epididymis to their wild-type configurations. (B) In testes from untreated adult Egr4-Egr1 mice, Leydig cells (arrow) appear atrophic and inactive, whereas after treatment with hCG (LH) (C), they show a clear response characterized by hypertrophy and hyperplasia (arrow). The Leydig cell response to hCG treatment is further characterized by complete restoration of the androgen-dependent organ changes present in untreated animals. Adult Egr4-Egr1-deficient preputial (D), submaxillary (E), and seminal (F) vesicles and epididymis and prostate are all restored to their wild-type configurations after treatment with hCG. Note that neither testosterone nor hCG treatment has any effect on testicular size (spermatogenesis). (A and F, bar = 2.5 mm; B and C, bar = 25 μm; D, bar = 1 mm; E, bar = 100 μm).

The fact that male androgen-dependent organs could respond to testosterone indicated that the phenotype in Egr4-Egr1-deficient male mice was a consequence of low androgen synthesis rather than androgen insensitivity. A low level of androgen synthesis could be due to a variety of defects, including inadequate stimulation of Leydig cells due to low levels of LH in serum, defects in LHr signaling, or defects in androgen biosynthetic pathways within Leydig cells. To examine the integrity of LHr signaling and androgen biosynthetic capacity within Leydig cells, hCG was administered daily for 17 days to double mutant mice. hCG administration was capable of activating Leydig cells, leading to marked Leydig cell hypertrophy (compare Fig. 3B and C). Moreover, all of the androgen-dependent male organs, including preputial (Fig. 3D), submaxillary (Fig. 3E), and seminal vesicles and epididymis (Fig. 3F) were restored to their wild-type size and configuration, indicating adequate production of testosterone by stimulated double mutant Leydig cells. Interestingly, hCG treatment had no effect on testicular size (Fig. 3F) or spermatogenesis (not shown). These results demonstrated that Leydig cell LHr signaling as well as androgen synthetic capacity and release was intact in male double mutant mice.

Normal GnRH and abnormal LH in Egr4-Egr1-Deficient male mice.

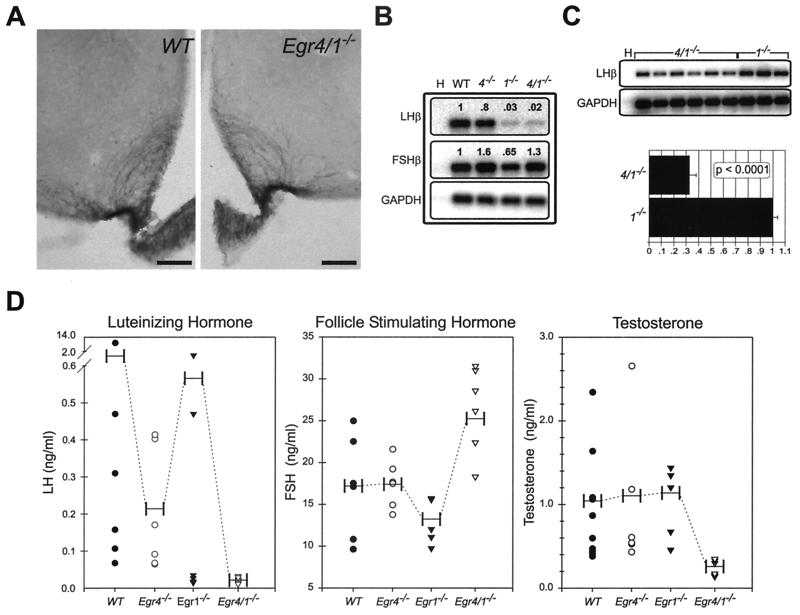

GnRH is produced by neurons that are diffusely distributed in the hypothalamus. It is released into the hypophyseal-pituitary portal system by axon terminals projecting to the median eminence of the forebrain. Since it was possible that the androgen insufficiency phenotype in double mutant males was due to defects in GnRH-containing neurons, we examined their integrity in the hypothalamus using immunohistochemistry. No qualitative differences in the distribution, number, or morphology of GnRH-positive neurons were noted between wild-type and double mutant adult male mice. These observations were substantiated by a normal-appearing plexus of GnRH-reactive axons and terminals in their primary target in the median eminence of Egr4-Egr1 double mutant male mice (Fig. 4A).

FIG. 4.

Low serum LH levels in Egr4-Egr1-deficient male mice are associated with low serum testosterone levels. (A) Immunohistochemical studies show no alterations in the integrity of GnRH-positive neurons in the hypothalamus (not shown) or their terminals that innervate the median eminence. (B) In the pituitary gland, semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis from pooled samples (n = 3, each genotype) demonstrates extremely low levels of LHβ expression in both Egr1- and Egr4-Egr1-deficient mice that are below the dynamic range of the assay. The levels of FSHβ expression are essentially unaffected (H) (no template water control). (C) Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of adult male pituitaries (Egr4-Egr1 deficient, n = 6; Egr1 deficient, n = 3) at increased PCR cycle numbers, but still within the logarithmic range of amplification, demonstrate that LHβ is threefold higher in Egr1-deficient relative to Egr4-Egr1-deficient mice (H) (no template water control). (D) LH serum levels are also different between adult Egr1- and Egr4-Egr1-deficient male mice. In Egr1-deficient mice, there appears to be some pulsatile release of LH, but in Egr4-Egr1-deficient mice, only low steady-state levels are observed. FSH levels are mildly elevated in Egr4-Egr1-deficient adult male mice. Low steady-state levels of LH dramatically affect serum testosterone levels in Egr4-Egr1-deficient mice. Apparently, in male Egr1-deficient mice, there is adequate pulsatile release of LH to maintain testosterone synthesis by Leydig cells (horizontal bars represent mean values).

In adult male pituitary glands, the expression of FSHβ was only slightly altered from wild-type levels in Egr4-, Egr1-, and Egr4-Egr1-deficient animals (Fig. 4B). However, LHβ was markedly decreased in pooled samples from Egr1- and Egr4-Egr1-deficient pituitaries (n = 3, each genotype; 3 and 2% of wild-type levels, respectively) well below the dynamic range of the RT-PCR assay (Fig. 4B). We next examined the expression of LHβ in pituitaries from independent samples from Egr4-Egr1 (n = 6)- and Egr1 (n = 3)-deficient adult male mice. By increasing the number of PCR cycles but still maintaining logarithmic amplification, we observed that the expression of LHβ was threefold higher in Egr1-relative to Egr4-Egr1-deficient males (Fig. 4C). These observations were corroborated by serum LH levels, which showed a clear difference between Egr1- and Egr4-Egr1-deficient males (Fig. 4D). The serum RIA levels for LH, FSH, and testosterone showed wide variability, an indirect result of the pulsatile secretion of the hormones into the serum. Whereas several LH measurements were below the normal range in Egr1-deficient mice, some measurements were well within the normal range (Fig. 4D). These results indicated that some degree of pulsatile release of LH was present in male Egr1-deficient mice and that it was apparently sufficient to maintain steroidogenesis and fertility. In Egr4-Egr1-deficient male mice, however, all of the measurements clustered well below the normal range, indicating low steady-state levels and a complete lack of pulsatile serum LH release. Levels of LH in serum in adult male Egr4-deficient mice were within normal range. Levels of FSH in serum were within the normal range in all adult male mice with the exception of a slight increase in the Egr4-Egr1 double mutant mice. This may have reflected upregulation by feedback mechanisms enhanced by low serum testosterone and markedly decreased levels of spermatogenesis. Serum testosterone levels were markedly low in Egr4-Egr1-deficient male mice and normal in Egr1- and Egr4-deficient male mice, entirely consistent with the androgen insufficiency phenotype observed only in double mutant males.

Testicular gene expression analysis.

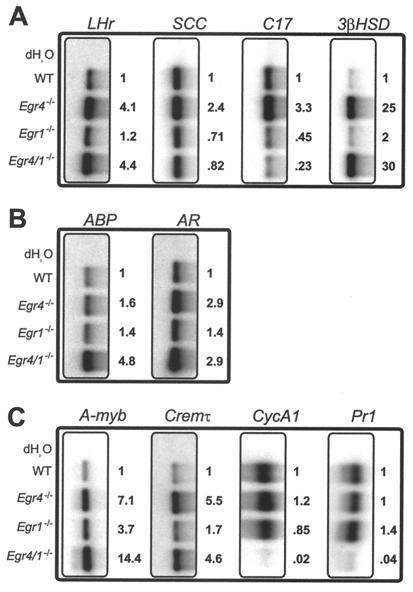

Testicular expression analysis of 10 genes involved in LH signaling or steroidogenesis (Fig. 5A), androgen signaling (Fig. 5B) and spermatogenesis (Fig. 5C) revealed multiple changes in mutant testes compared to adult wild-type male mice. The changes in gene expression most likely reflected alterations in homeostatic regulatory pathways within the testes. For example, the expression of LHr appeared to be inversely correlated with spermatogenesis. In both Egr4- and Egr4-Egr1-deficient mice in which spermatogenesis was highly disrupted, LHr was upregulated approximately fourfold, whereas in Egr1-deficient mice there was no change compared to wild type. Similarly, the steroidogenic enzyme 3-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3βHSD) was also inversely correlated with spermatogenesis. Whereas Egr1-deficient mice showed very little change in expression of 3βHSD, in both Egr4- and Egr4-Egr1-deficient males, there was upregulation by 25-fold and 30-fold, respectively. By contrast, expression of the steroidogenic enzyme side chain cleavage (SCC) was best correlated with serum LH levels. In Egr1- and Egr4-Egr1-deficient males, SCC expression was decreased slightly (71 and 82%, respectively), and in Egr4-deficient mice it was increased slightly (2.4-fold). Although not detected in the serum LH RIA experiments, the increased levels of SCC expression in Egr4-deficient mice may have reflected slightly increased levels of LH. This was suggested by the marked Leydig cell hyperplasia observed in Egr4-deficient testes (Fig. 1C). Finally, expression of the steroidogenic enzyme 17-α-hydroxylase (C17) was also best correlated with serum LH levels. In Egr4-deficient testes, C17 was upregulated 3.3-fold relative to that in wild-type testes. However, in Egr4- and Egr4-Egr1-deficient mice, it was reduced to 45 and 23%, respectively (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Testicular gene expression analysis. In wild-type and Egr4-, Egr1-, and Egr4-Egr1-deficient testes, genes involved in Leydig cell steroidogenesis (A), androgen binding (B), and spermatogenesis (C) showed altered levels of expression in mutant mice (see text for discussion). RT-PCR analysis was used to determine the relative levels of gene expression (see Materials and Methods).

Androgen binding protein (ABP) and androgen receptor (AR) are expressed primarily by Sertoli cells in the testis. The expression of ABP was inversely correlated with serum testosterone levels and was upregulated by 4.8-fold in Egr4-Egr1-deficient mice. However, AR appeared inversely correlated with spermatogenesis and was upregulated by 2.9-fold in both Egr4- and Egr4-Egr1-deficient mice (Fig. 5B).

The transcription factors A-myb and Cremτ regulate genes critical for spermatogenesis (1, 9, 17). In Egr4- and Egr4-Egr1-deficient testis, A-myb was upregulated 7.1-fold and 14.4-fold, respectively, whereas Cremτ was upregulated 5.5-fold and 4.6-fold, respectively (Fig. 5C).

Cyclin A1 (CycA1) is expressed in meiotic spermatocytes and is critical for spermatogenesis (6). The expression of CycA1 was decreased to 2% in Egr4-Egr1-deficient testis, most likely reflecting the near complete loss of maturing germ cells. Similarly, protamine 1 (Pr1) is expressed in elongating spermatocytes and was decreased to 4% in Egr4-Egr1-deficient testis.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that combined disruption of Egr4 and Egr1 in male mice leads to androgen insufficiency most likely due to a primary defect in the regulation of LHβ gene expression in pituitary gonadotropes. Moreover, males with only a single gene deficiency of either Egr4 or Egr1 did not have the low steady-state levels of LH and testosterone in serum that were identified in double mutant males. In Egr1-deficient males, LHβ expression was threefold higher than in Egr4-Egr1-deficient males. Moreover, there was evidence of pulsatile release of LH that was completely abolished in the Egr4-Egr1-deficient males, leading to very low steady-state levels of serum LH. Thus, Egr4 appears to functionally compensate, at least in part, for Egr1-dependent LH production and/or release in male mice. In Egr4-Egr1-deficient males, the defect was most likely localized to LHβ gene regulation based upon quantitatively lower levels in double mutant males, and the fact that atrophic androgen-dependent organs were completely restored to their wild-type configurations by administration of either hCG or testosterone. We were not able to identify any abnormalities in the distribution of GnRH-containing neurons in the hypothalamus or their terminal axons in the median eminence, suggesting that the upstream regulatory pathways involving gonadotrope stimulation were intact. Since pulsatile release of GnRH into the pituitary portal system is critical for appropriate gonadotrope stimulation, we cannot rule out the possibility that synchronous GnRH release is disrupted despite a normal distribution of GnRH-containing neurons and innervation of the median eminence. We favor the hypothesis that the defect is localized to pituitary gonadotropes since Egr4 is expressed in the pituitary and, similar to Egr1, is induced in vitro by GnRH receptor activation, which leads to increased transcription of the LHβ gene (3).

Egr4-Egr1-deficient male mice showed a defect in spermatogenesis that was substantially more severe than that present in the Egr4-deficient mice. The testes from double mutant males were smaller, and the seminiferous tubules contained a paucity of germ cells and large aggregates of Sertoli cells. In Egr4-deficient testes, a substantial degree of spermatogenesis was present, characterized by massive germ cell apoptosis (19) and nearly normal expression levels of the germ cell markers CycA1 and Pr1. Accordingly, in Egr4-Egr1-deficient males, complete spermatogenic arrest was substantiated by extremely low levels of CycA1 and Pr1. The complete spermatogenic arrest was not adequately explained by the combination of low testosterone and loss of Egr4-mediated transcriptional regulation, since there was no evidence of spermatogenic rescue after either hCG or testosterone administration in Egr4-Egr1-deficient mice. Rather, these results suggest that other intrinsic regulatory pathways are disrupted within Egr4-Egr1-deficient testes. Egr4 is expressed within maturing germ cells and plays a critical role in spermatogenesis, while Egr1 is expressed at high levels in Leydig cells, where its function is unknown (19). Egr1 does not appear to have a direct role in regulating steroidogenesis within Leydig cells, however, since there is no evidence of impaired steroidogenesis in Egr1-deficient males and steroidogenesis can be restored in Egr4-Egr1-deficient mice after hCG administration. It is possible that gene misregulation in Leydig cells (mediated by Egr1) and in germ cells (mediated by Egr4) disrupts critical intrinsic regulatory pathways leading to complete spermatogenic arrest in the absence of both transcription factors. In fact, feed-forward and feedback regulatory pathways between Leydig, Sertoli, and germ cells are thought to contribute to homeostatic conditions required for normal spermatogenesis (2, 8, 12). This hypothesis was supported by molecular evidence for homeostatic misregulation in Egr mutant testes. For example, upregulation of LHr and 3βHSD, both expressed primarily in Leydig cells, appeared to best correlate with decreased spermatogenesis, consistent with altered regulation of germ cell-Leydig cell homeostatic mechanisms. Similarly, AR and ABP, expressed primarily in Sertoli cells, were upregulated under conditions of decreased spermatogenesis (Egr4- and Egr4-Egr1-deficient testes). Finally, regulatory pathways involving intrinsic germ cell-specific transcriptional mechanisms were also upregulated when spermatogenesis was disrupted. The transcription factors A-myb and Cremτ, expressed specifically in germ cells, were markedly upregulated, presumably reflecting compensatory transcriptional responses to ineffective spermatogenesis.

It is not easy to reconcile the phenotypic differences that have been reported between our Egr1-deficient mouse (5) and an independently generated mutant mouse (16). In some ways, the mouse generated by Topilko et al. is similar to the Egr4-Egr1-double homozygous mutant male mouse characterized in this study, both of which have decreased levels of testosterone in serum, defects in spermatogenesis, infertility, and low body weight. However, the Topilko et al. Egr1-deficient mouse does not appear to have androgen-dependent organ atrophy or defective spermatogenesis to the degree that exists in our male Egr4-Egr1-deficient mouse. The phenotypic differences are possibly explained by a difference in genetic background since there are substantial polymorphisms between 129/Sv (Pasteur) and 129/SvJ (Jackson) mouse strains (14). However, differences in genetic background do not appear to be an important factor in the fertility of our Egr1-deficient mouse. We have backcrossed our Egr1-deficient mouse to a C57BL/6 strain (>10 backcross generations) and have not identified any fertility or steroidogenic defects in these mice.

These results clearly demonstrate that Egr4 can partially compensate for the function of Egr1 in regulating male Leydig cell steroidogenesis. The data most strongly support a defect in LHβ gene regulation that is severe enough to compromise its production at physiologically sufficient levels in Egr4-Egr1 double mutant mice. Although Egr1 appears to play a dominant role, Egr4 has a critical role as a redundant transcription factor required for sustaining male fertility when Egr1 is mutated in the germline.

TABLE 1.

Primer sequences used for RT-PCR gene expression analysis

| Target | Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| LHr | Sense | 5′-ATTATGCTCGGAGGATGGATTTTT-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-AAGCCGTTTTTGGAGTTGAAGGT-3′ | |

| ABP | Sense | 5′-TCAGCAATGGCCCAGGACAAGAG-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-GCTAGTGCGGGGAGAGGCTGAGAG-3′ | |

| SCC | Sense | 5′-AGATCCCTTCCCCTGGTGACAATG-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-CCCAGGCGCTCCCCAAATACAACA-3′ | |

| C17 | Sense | 5′-GGGACCAGCCAGATCAGTTCATG-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-AACCTCAGCCTGTGCATCCATCC-3′ | |

| 3βHSD | Sense | 5′-ACAGCAAAAGGATGGCCGAGAAGG-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-AGGAGGAAGGCAAGCCAGTAGAGC-3′ | |

| AR | Sense | 5′-TGGTTTTCAATGAGTACCGCATGC-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-TCTTGGGCACTTGCCAGAGATG-3′ | |

| A-Myb | Sense | 5′-CCGTTGGGCCGAGATTGCTAAGTT-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-TCTGCGAATTCTGGGATGGTCTGT-3′ | |

| Crem-τ | Sense | 5′-TTTCCTCTGATGTGCCTGGTATTC-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-CAGCACTGCGACTCGACTCTCAAG-3′ | |

| CycA1 | Sense | 5′-CCGCCCGACGTGGATGAGTTTGT-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-CTTGCTGCGGTCGATGGGGGATAC-3′ | |

| Pr1 | Sense | 5′-ATGGCCAGATACCGATGCTGCCGC-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-CTAGTATTTTTTACACCTTATGGT-3′ |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank L. Cabalka Tourtellotte, G. Gavrilina, T. Gorodinsky, C. Bollinger, and Clare Fadden for excellent technical assistance. Robert A. Benoit (Montreal General Hospital) generously provided the LR-1 antibody.

This work was supported by NIH grants MH1426-02 (W.G.T.) and CA49712-10 (J.M.) and by a grant from the Association for the Cure of Cancer of the Prostate (CapCURE) (J.M.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Blendy J A, Kaestner K H, Weinbauer G F, Nieschlag E, Schutz G. Severe impairment of spermatogenesis in mice lacking the CREM gene. Nature. 1996;380:162–165. doi: 10.1038/380162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boujrad N, Ogwuegbu S O, Garnier M, Lee C H, Martin B M, Papadopoulos V. Identification of a stimulator of steroid hormone synthesis isolated from testis. Science. 1995;268:1609–1612. doi: 10.1126/science.7777858. . (Erratum, 270:365.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dorn C, Ou Q, Svaren J, Crawford P A, Sadovsky Y. Activation of luteinizing hormone beta gene by gonadotropin-releasing hormone requires the synergy of early growth response-1 and steroidogenic factor-1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13870–13876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.13870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gharib S D, Wierman M E, Shupnik M A, Chin W W. Molecular biology of the pituitary gonadotropins. Endocrinol Rev. 1990;11:177–199. doi: 10.1210/edrv-11-1-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee S L, Sadovsky Y, Swirnoff A H, Polish J A, Goda P, Gavrilina G, Milbrandt J. Luteinizing hormone deficiency and female infertility in mice lacking the transcription factor NGFI-A (Egr-1) Science. 1996;273:1219–1221. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5279.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu D, Matzuk M M, Sung W K, Guo Q, Wang P, Wolgemuth D J. Cyclin A1 is required for meiosis in the male mouse. Nat Genet. 1998;20:377–380. doi: 10.1038/3855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyon M F, Hendry I, Short R V. The submaxillary salivary glands as test organs for response to androgen in mice with testicular feminization. J Endocrinol. 1973;58:357–362. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0580357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin-du Pan R C, Campana A. Physiopathology of spermatogenic arrest. Fertil Steril. 1993;60:937–946. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56388-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nantel F, Monaco L, Foulkes N S, Masquilier D, LeMeur M, Henriksen K, Dierich A, Parvinen M, Sassone-Corsi P. Spermiogenesis deficiency and germ-cell apoptosis in CREM-mutant mice. Nature. 1996;380:159–162. doi: 10.1038/380159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Donovan K J, Tourtellotte W G, Milbrandt J, Baraban J M. The EGR family of transcription-regulatory factors: progress at the interface of molecular and systems neuroscience. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:167–173. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(98)01343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider-Maunoury S, Topilko P, Seitandou T, Levi G, Cohen-Tannoudji M, Pournin S, Babinet C, Charnay P. Disruption of Krox-20 results in alteration of rhombomeres 3 and 5 in the developing hindbrain. Cell. 1993;75:1199–1214. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90329-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skinner M K, Norton J N, Mullaney B P, Rosselli M, Whaley P D, Anthony C T. Cell-cell interactions and the regulation of testis function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;637:354–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb27322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swiatek P J, Gridley T. Perinatal lethality and defects in hindbrain development in mice homozygous for a targeted mutation of the zinc finger gene Krox20. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2071–2084. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.11.2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Threadgill D W, Yee D, Matin A, Nadeau J H, Magnuson T. Genealogy of the 129 inbred strains: 129/SvJ is a contaminated inbred strain. Mamm Genome. 1997;8:390–393. doi: 10.1007/s003359900453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Topilko P, Schneider-Maunoury S, Levi G, Baron-Van Evercooren A, Chennoufi A B, Seitanidou T, Babinet C, Charnay P. Krox-20 controls myelination in the peripheral nervous system. Nature. 1994;371:796–769. doi: 10.1038/371796a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Topilko P, Schneider-Maunoury S, Levi G, Trembleau A, Gourdji D, Driancourt M A, Rao C V, Charnay P. Multiple pituitary and ovarian defects in Krox-24 (NGFI-A, Egr-1)-targeted mice. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:107–122. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.1.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toscani A, Mettus R V, Coupland R, Simpkins H, Litvin J, Orth J, Hatton K S, Reddy E P. Arrest of spermatogenesis and defective breast development in mice lacking A-myb. Nature. 1997;386:713–717. doi: 10.1038/386713a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tourtellotte W G, Milbrandt J. Sensory ataxia and muscle spindle agenesis in mice lacking the transcription factor Egr3. Nat Genet. 1998;20:87–91. doi: 10.1038/1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tourtellotte W G, Nagarajan R, Auyeung A, Mueller C, Milbrandt J. Infertility associated with incomplete spermatogenic arrest and oligozoospermia in Egr4 deficient mice. Development. 1999;126:5061–5071. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.22.5061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tremblay J J, Drouin J. Egr-1 is a downstream effector of GnRH and synergizes by direct interaction with Ptx1 and SF-1 to enhance luteinizing hormone β gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2567–2576. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]