Abstract

Strong leadership capabilities are essential for effective health services, yet definitions of leadership remain contested. Despite the acknowledged contextual specificity of leadership styles, most leadership theories draw heavily from Western conceptualizations. This cultural bias may attenuate the effectiveness of programmes intended to transform healthcare practice in Sub-Saharan Africa, where few empirical studies on health leadership have been conducted. This paper examines how effective leadership by doctors was perceived by stakeholders in one particular context, Sierra Leone. Drawing together extensive experience of in-country healthcare provision with a series of in-depth interviews with 27 Sierra Leonean doctors, we extended a grounded-theory approach to come to grips with the reach and relevance of contemporary leadership models in capturing the local experiences and relevance of leadership. We found that participants conceptualized leadership according to established leadership models, such as transformational and relational theories. However, participants also pointed to distinctive challenges attendant to healthcare provision in Sierra Leone that required specific leadership capabilities. Context-specific factors included health system breakdown, politicization in the health sector and lack of accountability, placing importance on skills such as persistence, role modelling and taking initiative. Participants also described pressure to behave in ways they deemed antithetical to their personal and professional values and also necessary in order to continue a career in the public sector. The challenge of navigating such ethical dilemmas was a defining feature of leadership in Sierra Leone. Our research demonstrates that while international leadership models were relevant in this context, there is strong emphasis on contingent or situational leadership theories. We further contribute to policy and practice by informing design of leadership development programmes and the establishment of a more enabling environment for medical leadership by governments and international donors.

Keywords: Leadership, leadership capability, leadership development, clinical leadership, health system context, Sierra Leone, Sub-Saharan Africa

Key messages.

Leadership was considered essential to an effective health system in Sierra Leone, and concepts of leadership were generally aligned with international leadership theory.

Participants did however feel that distinctive context-specific factors in the health sector in Sierra Leone put particular emphasis on certain leadership capabilities, such as persistence and role modelling.

The challenge of navigating the politics and professional demands of providing care with limited resources was a commonly held experience. That negotiation between personal ideals and everyday realities required courage and difficult decisions about when to compromise and when to leave the system.

While there is a role for leadership development programmes, improving leadership practice will also require those features of the health system environment that constrain courageous and effective decision-making to be addressed.

Introduction

In the 1970s, Ralph Stogdill famously noted ‘there are almost as many different definitions of leadership as there are persons who have attempted to define the concept’ (in Drath et al., 2008). Fifty years later, definitions of the term continue to proliferate across the academic and popular literature. A central conceptual question is whether leadership should be viewed as a personal characteristic, as a role or as a process—as an attribute of individual action (individualized leadership) or a feature of group social practice (collective or shared leadership) (Yukl, 2009). Another theoretical debate in leadership is its close relationship with understandings of management, with the two described as ‘a conceptual knot that is difficult to untangle’ (Fernandez et al., 2010). Situational leadership theorizes that leadership styles should be adapted depending on the context (Northouse, 2015, p. 95). A further leadership question is whether models of effective leadership should be considered universal or whether specific cultural traditions, values, ideologies and norms—that may vary between regions, countries or communities—have important influences. The Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) study, based on responses to ∼17 000 questionnaires from middle managers of 951 organizations in 62 nations, found that while some leader behaviour dimensions were universal, others varied by culture (House et al., 2002). Common leadership theories that are referred to in this paper are summarized in Box 1.

Box 1. Selected common leadership models and their definitions.

| Leadership model | Definition |

|---|---|

| Collective/Shared | A dynamic, interactive influence process among individuals in groups for which the objective is to lead one another to the achievement of group or organizational goals or both. (Pearce and Conger, 2003) |

| Individualized | Effective performance by an individual, group, or organization is assumed to depend on leadership by an individual with the skills to find the right path and motivate others to take it. (Yukl, 1999, p. 292) |

| Managerial | A hybrid form of leadership that emphasises management roles including setting goals and plans, organizing and staffing, and solving problems and monitoring results (Fernandez et al., 2010; Sementelli, 2020) |

| Situational | To be an effective leader requires that a person adapt his or her style to the demands of different situations (Northouse, 2015, p. 95) |

| Relational | Leadership as an interpersonal phenomenon associated with collaboration, empathy, trust and empowerment (Cummings et al., 2018 in Cleary, Du Toit et al., 2018) |

| Servant/Humble | Placing the good of followers over their own self-interests and emphasizing follower development. Demonstrating strong moral behaviour towards followers, the organisation and other stakeholders (Northouse, 2015, p. 228) |

| Transformational | Raising the aspirations of followers, such that the leader’s and the followers’ goals are fused in pursuit of a higher purpose. Consists of charisma, inspiration, individualized consideration and intellectual stimulation (Currie and Lockett, 2007) |

Regardless of its conceptualization, strong leadership capabilities are essential for effective health services (World Health Organization, 2007, p. 3) and have been described as a ‘vital element of health system development and reform’ (Gilson, 2016, p. 187). Reviews have shown that leadership is positively associated with a range of important organizational factors including individual work satisfaction, turnover and performance (Gilmartin and D’Aunno, 2007).

To-date, however, the study of leadership has been heavily skewed towards Western conceptualizations, potentially undercutting the impact of programmes intended to transform healthcare practice into other settings (Blunt and Jones, 1997). Haruna argues, for instance, that Western models of leadership fail to grasp the lived reality in Sub-Saharan Africa or the continent’s historical, social, cultural or moral experiences (2009). It is clear however that although ‘context is essential to the conceptualization of African leadership, little empirical research has been conducted on leadership, particularly in the area of health’ (Curry et al., 2012). Two recent reviews on leadership in healthcare, from Belrhiti et al. (2018) and Cummings et al. (2018), further confirm this, with each only identifying two studies from Sub-Saharan Africa compared to 24 and 45 studies from the USA.

There is, however, evidence of a growing interest in the study of the leadership development of health professional in Sub-Saharan Africa over the last two decades (Doherty et al., 2018; Kebede et al., 2012; Kwamie et al., 2014; Najjuma et al., 2016). Many of these leadership programmes, however, lacked a clear conceptual framework for how leadership was understood in their specific context (Johnson et al., 2021). We build upon those insights by addressing gaps in the literature around healthcare leadership in Sub-Saharan Africa through an exploratory, in-depth qualitative study in one specific setting. We are primarily concerned with context-specific evidence on how stakeholders in the health sector understood the concept of leadership and perceived the impacts and characteristics of effective leadership by doctors in Sierra Leone. In this paper, we use Pfadenhauer et al. (2017) definition of context as reflecting ‘a set of characteristics and circumstances that consist of active and unique factors, within which the implementation is embedded…It is an overarching concept, comprising not only a physical location but also roles, interactions and relationships at multiple levels.’

We focus specifically on doctors not to privilege them over other professional groups that also play central roles in leadership in healthcare, but rather on the premise that doctors (as with other groups) have distinctive professional identities, training pathways and job roles that might influence how they perceive leadership. Furthermore, doctors occupy specific senior positions of authority in the government health system, including as the head of hospitals and the professional branch of the Ministry of Health and Sanitation.

The objectives of the study were to:

Describe how stakeholders in the health sector understood the concept of leadership and perceived the impacts and characteristics of effective leadership by doctors in Sierra Leone.

Inform the design of leadership development programmes in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Inform the development of health policies to create an enabling environment for effective leadership to be nurtured and adopted.

Provide specific contextualized findings to inform policy and practice in Sierra Leone.

Sierra Leone was selected as the setting for our enquiry as it shares many historical and health system features with other countries in the region, including colonialism, conflict and significant exposure to the international aid sector (see Box 2). It also held advantages for our research in being a small country, making it feasible to elicit a national perspective through the research, as well as its recent experience of a major Ebola outbreak, which can offer particular insights for other countries that have been affected by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

Box 2. Key demographic, health system and historical features of Sierra Leone.

Sierra Leone, situated on the coast of West Africa, has a population of seven million, of which just under a quarter live in or around the capital city of Freetown (Statistics Sierra Leone, 2016).

Sierra Leone's formal health system includes 21 district hospitals and three tertiary hospitals in the public sector, there are numerous small- or medium-sized mission and private hospitals (Ministry of Health and Sanitation Government of Sierra Leone, 2017). After gaining independence from British colonial rule in 1961, the Sierra Leone's democratic governance became increasingly authoritarian. Between 1991 and 2002 the country experienced a civil war, during which time many health professionals emigrated, while those that stayed often had their training interrupted. After the war, Sierra Leone returned to democracy and has experienced several peaceful transfers of power between two political parties.

The country's medical school, the College of Medicine and Allied Health Sciences, was established in 1988. Before then, medical training was carried out abroad (such as in other parts of Africa, Europe, China or the former Soviet Union). In 2016, Sierra Leone reported having 156 junior and middle grade doctors and 41 medical specialists. 18% of these were women and 82% men (Ministry of Health and Sanitation Government of Sierra Leone, 2016). With just three doctors in the public sector per 100,000 population, compared to the WHO's minimum recommended standard of 100 doctors per 100,000 population, the country's health sector is considered to be critically understaffed (Ministry of Health and Sanitation Government of Sierra Leone, 2017; World Health Organization, 2020)

Classified as a low-income country, the country's health system is heavily dependent on foreign donors, who contribute ∼24% of total health expenditure compared to 7% from government funds (Ministry of Health and Sanitation Governement of Sierra Leone, 2013). Public sector salaries are low, with medical officers earning ∼$400 per month (which increases to $700 when including additional government allowances). Doctors commonly work in the private sector alongside their government posting. Corruption has long been endemic in the public sector, although this is considered to have improved in recent years, with Sierra Leone ranked 119th out of 198 countries in the most recent Corruption Perception Index (Transparency International, 2020).

The Ministry of Health and Sanitation has a Chief Medical Officer (CMO), who is the professional head and a doctor, and a Permanent Secretary, who is the administrative head and is a non-medical civil servant. The professional division oversees functions such as the management of hospitals and labs, health worker training, disease surveillance and drugs supply. The CMO plays a key role in deciding where doctors are posted and acts as a gatekeeper for some international postgraduate training scholarships. The administrative division oversees functions such as finances and human resources. (Ministry of Health and Sanitation Government of Sierra Leone, 2017)

Management of primary and secondary care facilities, including their budgets, is devolved to elected district councils, although the Ministry still controls critical decisions around staffing, equipment and drugs supply. Government primary care facilities are generally staffed and led by nurses and community health officers, whereas secondary and tertiary hospitals are led by a medical doctor with a matron and hospital manager or administrator in senior posts. There is no formal training programme for hospital managers or administrators in the country and most people in these posts have backgrounds as secretaries or clerks.

After graduating, doctors commonly bifurcate into two main career pathways: clinical or public health. As Sierra Leone is still in the process of establishing its own specialist medical training, doctors wanting to work as clinicians will either remain as medical officers or, most likely, will apply to go abroad for further training to become specialists, which is often funded by international agencies. Senior clinicians may become heads of department at health facilities or in the medical school, or medical superintendents of hospitals. Alternatively, doctors may study for a Masters in Public Health and take up roles in District Health Management or as programme managers in the Ministry of Health and Sanitation. However, many doctors continue to emigrate abroad permanently, often to Europe or the USA.

The country experienced a major Ebola outbreak from 2014 to 2016 which, alongside its social and economic impacts, led to significant loss of life amongst health professionals and further interruption in their training (Walsh and Johnson, 2018).

The Government of Sierra Leone has itself recognized the importance of strengthening governance, leadership and management, including it as one of five strategic priorities in its human resources for health strategy, which commits to ‘investments in the leadership and management capacity at all levels of the [Ministry of Health & Sanitation] and in public health facilities’ (Ministry of Health and Sanitation Government of Sierra Leone, 2017, p. 37). Despite health leadership being a government priority and a history of health workforce research studies in the country, these specific issues have not previously been explored (Raven et al., 2018; Witter et al., 2017).

Methods

This study applied prospective, descriptive qualitative study methodology using in-depth interviews. Interviews were conducted in two phases: an exploratory phase (14 interviews conducted between October 2019 and February 2020) followed by a second phase (13 additional interviews conducted between February and April 2021) where the initial findings were shared for feedback and consultation.

Participants were selected purposefully to achieve coverage of diverse backgrounds within the medical profession, in order to give a more holistic set of views on this issue. This included a range of seniorities to ensure that perspectives from all levels of the professional hierarchy were captured, since seniority can indicate experience, the types and degree of authority of position and the generation in which a participant trained and worked. Participants were also recruited to ensure that the sample included experience across clinical care and public health, as well as the public and private sectors. Doctors who had left the country were also included in order to capture a wider range of views.

OJ and FS identified the initial participants, based on their roles and experience of leadership. A snowballing technique was used to identify doctors who other participants believed had experiences in leadership and who were reflective about leadership by doctors in Sierra Leone.

Participants were approached by phone call, text message or email and invited to participate. Participation was entirely voluntary, and no incentives were offered. Interviews were conducted in convenient private spaces, such as offices or public restaurants. Written informed consent was gained from every participant.

A topic guide was used to orient discussions and is listed in Supplementary Appendix 1. This was developed collaboratively by the authors and piloted with one initial interview, after which no changes were made. Interviews were conducted by the lead author (OJ), lasted between 25 minutes and 2 hours in length (median duration = 44 minutes) and conducted in English, which is widely used for professional communication in Sierra Leone. Most interviews were conducted in person over a 2-week period in October 2019, with the remainder being carried out virtually between October 2019 and February 2020. Questions were open-ended and exploratory in nature. The term ‘leadership’ was deliberately not defined by the interviewer so that participant understandings of leadership could be ascertained inductively. Similarly the interviewer did not attempt to define ‘management’ and allowed the participant to include management concepts or skills in their discussion of leadership if they chose.

The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Virtual interviews were conducted using Zoom, Skype or Whatsapp.

A total of 14 initial interviews were conducted. Existing methods were used to calculate the sample size based on saturation, which suggest that early saturation can be reached at six interviews and can be safely expected at 12 interviews (Guest et al., 2006). We oversampled in order to increase the representation of women in our sample. In practice, we found that saturation was reached after the 11th interview, after which no new issues emerged.

The interview data were complemented by observational experience from the lead author, who had previously spent 3 years embedded in a government hospital in Sierra Leone and had worked closely with the University and Ministry of Health and Sanitation over a 12-year period. FS trained as a doctor in Sierra Leone and has over 20 years’ experience in the health sector.

Their observations preceded this study and were not systematically recorded apart from in a book on Sierra Leone’s Ebola response written by the lead author (Walsh and Johnson, 2018). The role of these observations in the analysis was primarily to provide a deeper contextual understanding of issues raised by participants. For example, participants were able to reference previous shared experiences with the interviewer to make complex or nuanced points and to share detailed case studies involving individuals, groups and facilities.

To reduce potential bias, confidentiality was emphasized in interviews and some participants were selected who had no previous relationship with the interviewer or familiarity with his previous roles. We found that participants spoke openly during their interviews about extremely sensitive topics and were quick to challenge the interviewer if something had been misunderstood. FS, whose experience of healthcare provision drew from a different institutional context and were far more extensive than that of OJ, was able to provide a second independent viewpoint that further helped to reduce any bias brought to the analysis by OJ’s observation.

Verbatim interview transcripts were uploaded onto Nvivo 12 software. The lead author reviewed each transcript in detail, assigning codes to relevant sections of data, using a grounded theory approach and drawing on the work of Corbin and Strauss (2008). Analysis was conducted in stages using a systematic, inductive process in order to generate insights that were grounded in the views that were expressed by participants, following the constant comparative method (Glaser, 1965). For example, ‘doing more, talking less’ was identified as emerging theme in an early interview and then compared to the emphasis placed on the importance of ‘delivery’ in a later interview. Keeping in mind the contextual specificity in which these themes were articulated, their shared significance prompted the analytical decision to merge ‘delivery’ and ‘doing more, talking less’ into a higher order code: ‘delivers’ which following further interviews provided the basis for generating a more formal theory of effective leadership in this context. Codes were then sorted into concepts such as ‘relational leadership’ or ‘systems don’t work’. Concepts were then clustered together in categories such as ‘perceptions of effective leadership’ or ‘contextual challenges’ that broadly align with the headings in the results section.

Running notes were taken throughout relating to the concepts and categories that the author was identifying. The data were shared routinely with co-authors and individual or group discussions were held with the lead author to review the codes, concepts and categories and to develop and reflect on the theories being developed. As each transcript was reviewed, data was compared to sections that had already been coded in order to determine whether the same concept was apparent. Where existing codes were inadequate, new codes were added or existing codes were re-defined. Later participants were presented at the end of their interviews with emerging concepts and theories and asked to comment.

Ambiguous data were referred to the wider team for input during regular review meetings. The final codes were also reviewed, including their key properties and relationships, to ensure that there was consensus on the unifying themes that emerge.

Initial findings were shared with two participants of the study that were identified to represent the perspective of a senior and a junior doctor, selected based on their accessibility, since the conversation had to happen remotely due to COVID. This enabled an iterative and recursive approach that provided critical insights into the data.

The findings were also triangulated through interviews with an additional 13 doctor, who corroborated and informed the analysis.

Of the 27 people interviewed in the first and second phases, six participants were early-career doctors (i.e. had not yet started specialist training), five were middle-grade doctor (currently undertaking specialist training or in registrar posts) and sixteen were senior doctors (clinical specialists or professors). Four were primarily based in Ministry of Health and Sanitation, four in University, fifteen were in government hospitals, two in private hospitals, one at an non-governmental organization (NGO) and two were primarily based abroad1. Many participants simultaneously held multiple professional roles across these institutions or had worked across different types of roles previously and also had their own private clinics or worked at NGO or private hospitals. As such they were broadly representative of the medical profession in Sierra Leone. Of the senior doctors, all had previously run government hospitals, hospital departments, departments at the Ministry of Health and Sanitation or departments at the universities. Of the junior- or middle-grade doctors, most had previously held leadership roles in the medical students’ or junior doctors’ association. Twenty six had received at least 1 year of training abroad. Nineteen were men and eight were women. Verbatim quotes in the results section reference the participants’ seniority and gender but further context could not be provided without risking that the individual could be identified.

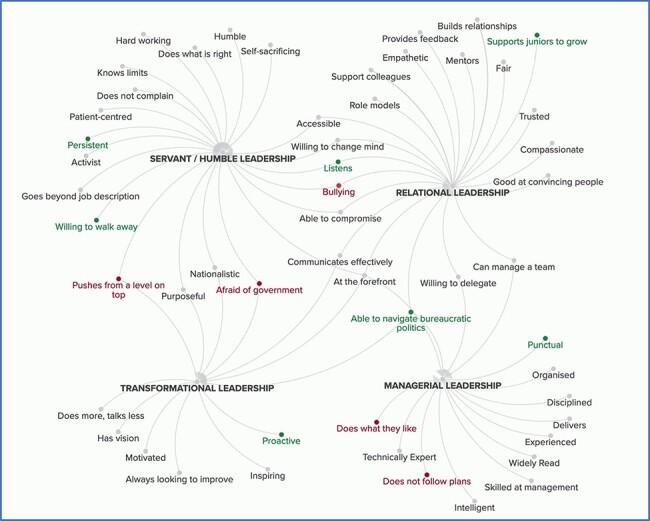

For two major topics of the study, the perceived qualities of effective leadership and the context in which that leadership took place, the relevant codes were placed onto a visual map so that the relationship between themes could be shown. Codes that appeared thematically similar were placed close together on the map. Themes were identified related to each cluster of codes, and these themes were added as labels to the visual map. For example, with the visual map of the qualities of effective leadership, the themes identified were models of leadership (such as transformational or relational leadership).

This process of visual mapping drew on methodologies for concept mapping in qualitative research, which can assist with reducing data, analysing themes and presenting findings (Dailey, 2004; Trochim et al., 1994). Our visual mapping process was distinct from concept mapping, however, in that we did not attempt to construct a hierarchy or show relationships between the codes, since these features were not apparent in our data. Rather, the focus here was on clustering a set of emergent concerns through an iterative and reflexive process in order to identify key themes. Kumu visual mapping software was used to create the graphics (Kumu Inc, 2021).

The main author had training as a medical doctor, and our analysis draws from expertise in anthropology, psychology and global health.

Results

Data from our study provides insights on several aspects of the perception of leadership by doctors in Sierra Leone. General reflections included how doctors defined and understood leadership, the perceived strength of leadership by doctors in Sierra Leone, and how this can impact on the health system. Specific themes were also identified around how participants described effective leadership by doctors in Sierra Leone and some the contextual challenges that are experienced. Finally, the issue of navigating leadership dilemmas is described.

General views on leadership

All participants drew on an individualized concept of leadership that emphasized the role of the single leader, rather than describing leadership as a shared phenomenon or the emergent property of a collective. A number of participants did however speak of the importance of creating consensus and of taking a participatory approach by engaging team members in decision-making processes.

Leadership was also viewed by a majority as being centred on authority or position:

I would define leadership as a state where authority is given to someone to manage an entity (Senior doctor, male).

However, two participants (both early-career doctors) explicitly pushed back on this emphasis on authority, criticizing that viewpoint and instead arguing that leadership was available to everyone, regardless of their role in an organization:

If I were to use one word to show leadership, it’s service.. Unlike if you think that leadership is about authority or control. And then you will miss it altogether (Early-career doctor, male).

But the thing is, everyone should lead, everyone can lead, that’s the point… So, for me, we are all leaders… But then, we are seeing it as an appointment, a position that you can come and make whatever you want to make, at times to the detriment of others (Early-career doctor, male)

Leadership was defined by most participants as being centred on managing people, with other descriptions relating to driving change, setting a vision, having influence or being of service.

A majority of participants thought that leadership by doctors currently fell short. However, several also felt that it was improving, that doctors were doing the best they could in the circumstances and that leadership training should be introduced.

Even doctors think they are poor leaders and poor managers, and therefore that doctors should not lead in anything (Junior doctor, male).

Sometimes we’re there and we’re doing the job but we’re not doing it well, because we’re not trained, so in a way I would not blame us for doing the wrong things (Middle-grade doctor, female)

So, it is something that each and every layer of the health sector should be exposed to structurally, with a structured programme. It could be in one group or it could be done in phases, but I think it is necessary that at each level, some form of leadership training should be done (Senior doctor, male).

Participants gave a range of examples of the impact that they perceived leadership by doctors to have.

We know how crucial leadership is, in terms of the medical system, because if it’s absent then patients suffer and sometimes even us, the workers, end up that way too (Junior doctor, male).

These examples can broadly be placed into three categories (see Table 1): the quality of patient care, impacts on the health workforce and the development of new services.

Table 1.

Examples of the impacts of leadership by doctors in Sierra Leone

| Quality of patient care |

‘Because of the leadership role that we provided, we saw improved clinical outcomes. Because most of the treatment centres, the Ebola treatment centres that were in the country at that time… when patients were taken to those centres they mix your drink, your ORS [oral rehydration solution], and just put it by you, give you your food and put it by you, if you eat it that’s your business. But with us at [hospital name], because of leadership and what actually we stood for, we told the nurse, or whoever brings in the food, that you must make sure that this patient eats before you leave the centre.’ Senior doctor, male ‘[The head of the hospital’s] own leadership style is he has sustained regular meetings … And with that, everybody almost knows what is happening in other departments… It has turned down the number of rumours we get about people and the way they behave to patients a lot.’ Early career doctor, male ‘There’s hardly anybody amongst us who is working in any of the private hospitals, because the head of the hospital will show up in our wards, in our department, at any time.. That is different from the other hospitals… And that one has a huge impact on patient care. Because, at the end of the day, what if patients develop complications in the afternoon?’ Early career doctor, male |

| Impacts on the health workforce |

‘Nurses will complain that maybe sometimes the way that doctors talk to them, the way they.. So, it’s like, it’s not there.. So, that is very difficult, because if the nurse is not happy, maybe you will say something, they will not comply. At the end of the ladder, who suffers? The patient suffers.’ Senior nurse, female ‘The impact is that there are so many people going into [clinical specialty] now…People love his style so much, they love his way of doing things, that they want to come in.’ Middle-grade doctor, female |

| Development of new services |

‘There were issues in revenue collection in the hospital. And one of the things that I thought would improve revenue collection in the hospital was getting a central bank… And eventually we convinced them. And we have a bank now. And the amount of revenue collected has improved significantly.’ Senior doctor, male ‘I actually set up the [specialist clinical service] at that time and it was something that was new and it was a novel idea to bring in. And once I came up with the idea, I had to pilot it through the Ministry for acceptance as well as for financial support. At that stage, it was very important that I show some degree of leadership… We were able to start the unit and it developed quite rapidly. So, I think the leadership, not just from that specific example I’ve given you but from so many other service developments.’ Senior doctor, male |

Leadership was seen to affect the performance and behaviour of staff when it came to the frontline delivery of care, including the culture within a particular health facility, for example by influencing communication, coordination, teamwork and punctuality. These were all considered to have a direct impact on the quality of patient care.

Participants also spoke of how leadership by doctors exerted a broader influence on the health workforce, indirectly affecting patient care. This could be through encouraging ethical (or unethical) behaviour amongst staff, by giving feedback and by creating a learning environment. Examples were also given of how advocacy by doctors improved the working conditions of health workers and of how leadership could affect whether other doctors chose to emigrate or to stay in the country, as well as the morale of health staff. Role modelling by senior doctors was described as an important influence on the clinical specialties taken up by early-career doctors.

Finally, a number of instances were reported of how leadership by doctors resulted in the establishment of new clinical services or new health training programmes, which was seen to play a significant role in strengthening the health system.

Perceptions of effective leadership by doctors

In their interviews, participants were asked to give examples of effective and ineffective leadership by doctors in Sierra Leone and to describe effective medical leadership.

After mapping the codes visually (see Figure 1), we were able to identify four main clusters of codes that were conceptually similar to four major leadership models (described in Box 1). Negative leadership qualities were also identified. Supporting examples from the interviews are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Visual map of effective leadership. Common ideas (‘codes’) from the interview data are represented by grey dots. Related ideas have been clustered together and then linked to major theories on leadership (bold) green dot denotes high frequency or emphasis and red as negative characteristics

Table 2.

Examples of the four main themes of effective leadership by doctors in Sierra Leone

| Managerial | ‘The qualities of an ideal doctor-leader would be somebody who is able to create a system…so you have your calendar for the week or for the month, you have your team, you and the team going according to that calendar’ Senior doctor, female |

| Transformational | ‘A leader is someone who has vision to see far ahead. I think that we’re going to need something like this in ten years, so how do we start working on getting that now.’ Middle-grade doctor, female |

| Servant/ Humble | ‘And he’s hard-working. Yes. He’s quite hardworking. And [another doctor], hard-working, honest and humble’ Junior doctor, male |

| Relational | ‘Even the least person, whatever he tells you, this is a good idea, you know? Let the person feel that he is important in the entire operation.’ Senior doctor, male |

Managerial skills included being organized, well-informed and ensuring performance, with particular emphasis placed on punctuality and the ability to navigate bureaucratic politics (which we also considered a relational skill). While management skills are sometimes described as distinct from leadership, we included them here to reflect how participants viewed effective leadership. Transformational leadership was cited as having a vision for the future, motivating and inspiring others, having a commitment to the nation and, in particular, being proactive. A servant or humble leadership approach included knowing your limits, working hard, sacrificing and doing what is right. Above all else, participants spoke of the importance of being persistent in pushing for change, being willing to walk away from your job if pressured into doing something improper and listening to others (which we also considered a relational quality). Finally, relational leadership included building trust, showing empathy and compassion, being able to convince others, communicating effectively and being willing to change your mind. Many participants emphasized the importance of supporting junior staff to grow.

Certain leadership characteristics were considered to have a negative impact on the health system. Participants spoke of leaders not following their plans, of bullying, of being too afraid of government and, in particular, of failing to hold themselves or others accountable such that anyone could do what they liked. This is explored further in the next section.

There are loads and loads of examples of bad leadership, lack of accountability, so basically the people you’re leading don’t feel accountable to you, so because of that they just do what they want to do, or lack of motivation from the leader, lack of respect from the leader from the people they are leading, especially doctors, consultants, shouting at the junior doctors and embarrassing them and making them feel intimidated and, loads of examples (Senior doctor, female).

Sometimes you face threats, threats of either losing your job, threats of being victimised in the system as a junior doctor (Junior doctor, male).

The role of context in health leadership in Sierra Leone

Participants were fairly consistent in holding the view that the main features of effective leadership conformed to international models of leadership but that there were specific contextual challenges to Sierra Leone that had to be navigated.

Well, there are things that are similar. For instance, people need to be inspired to be good leaders. It is difficult to be a good leader out of a vacuum. So, you need to be inspired. And I think that is true for every society. But the way in which you are inspired is what is different from place to place (Junior doctor, male).

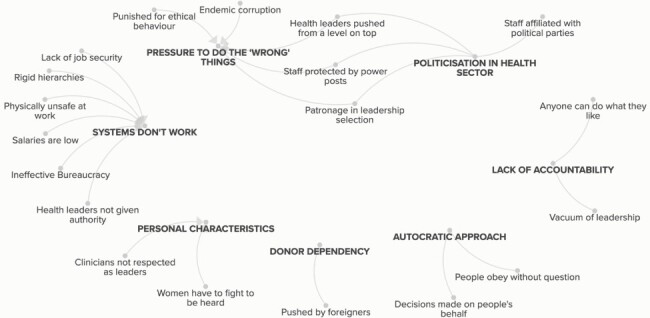

These conceptual factors are presented visually in Figure 2, which illustrates seven major themes: systems don’t work, pressure to do the ‘wrong’ things, politicization in health sector, lack of accountability, autocratic approach, donor dependency and personal characteristics. Examples given by participants are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Visual map of distinctive contextual factors. Seven key themes (in bold) were identified from the codes

Table 3.

Examples of the role of context in leadership by doctors in Sierra Leone

| Systems don’t work |

‘Another part of understanding the context in which we are working is if you say you want everything to be put in place before you do your work, you will never do your job. So sometimes you have to make do with what you have and understand that things are not happening the way they ought to be because some people are just bad, but it’s a systemic problem.’ Junior doctor, male ‘The instruments are broken, we write to the Ministry [Raises voice] You’ve written, you’ve re-written, you’ve re-re-written… but nothing is happening.’ Senior nurse, female |

| Pressure to do the ‘wrong’ things |

‘I knew a very senior colleague who was posted as a medical superintendent… I think the practice that used to be in these places was that they have to share a certain percentage [of the budget with individuals at District Council and Ministry], you understand? … So, at the end of the day, you just have a small percentage going for running the hospital, you understand? And this person was entirely against that. And so, the first time he got his first budget being funded, he didn’t share anything, he put everything into running the hospital. He didn’t survive that year.’ Junior doctor, male ‘So, because you don’t take money [illegally from patients], they won’t give you cases to operate on.’ Junior doctor, male |

| Politicization in health sector |

‘In terms of political interference… people expect that if you are in charge of a particular organisation, the politicians expect that you should be able to do what they say. And, unfortunately, I think some people are so protective of their jobs that they are sometimes too willing to accede to the wishes of politicians, or orders from above.’ Senior doctor, male ‘In Sierra Leone, yes, even the colours you wear sometimes are associated with something. So, it’s very difficult, I feel like it makes the job even more difficult, because you have to be very careful with what you do. I always that that as medical professionals, we have to think about politics.’ Middle-grade doctor, female |

| Lack of accountability |

‘There is no yearly appraisal system, which means anyone can do whatever he likes, and no one will ask you. I mean you can, as long as you keep going, you’re fine, but no one will measure your impact.’ Junior doctor, male ‘Lack of accountability, so basically, the people you’re leading don’t feel accountable to you, so because of that they just do what they want to do.’ Middle-grade doctor, female |

| Autocratic approach | ‘When somebody is supposed to be a leader, people that he or she is leading obey without question. I think that goes down to chieftaincy style of rule, and that kind of thing, such that they don’t feel confident to bring in ideas, but they think that you should know, you are the leader… So, if you don’t go out of your way to tell people that their opinion counts, then it’s likely that you’re going to be autocratic and do things your own way.’ Senior doctor, male |

| “Our deference to authorities [is] ingrained in our culture. For instance, as a “good son”, I am not expected to tell my father that his view on something is erroneous even though I may be preview to the fact. I am expected to be quiet about it out of respect. Thus, it is expected of me to give the same reverence to people in authority (and the authorities demand it if I fail to).” Junior doctor, male | |

| Donor dependency | ‘We have gone into this donor dependency syndrome, where we think that this is a big issue and we need some sort of external help. Whereas if we had been innovative, we could have solved it ourselves. So that’s the issue. So, people don’t think anymore’ Junior doctor, male |

| Personal characteristics |

‘In Sierra Leone… I have the feeling that people pay less attention to women that to men, so unfortunately you have to be a bit bolder… I had to stand up in some meetings and say “Look I’m talking, can you listen to me? This is my decision that I’m taking and that’s it. You cannot override it”’ Senior doctor, female ‘We have a lot of young people who are leaders and then old people who feel like we cannot tell them or advise them, I think we have that issue right now in Sierra Leone… People just don’t believe that you as a small kid or as a young lady doctor or a man can tell them what they don’t know. They feel like they know it all.’ Middle-grade doctor, Female ‘If you do public health you are a leader, if you do not do public health you are not a leader. And if you do public health you should be in the Ministry, and if you haven’t done public health you should stay in the hospital. And if you’ve done public health you should lead, maybe even to lead anywhere, but if you are doing clinical work you shouldn’t lead anything because you don’t have any qualities. But the thing is, everyone should lead, everyone can lead, that’s the point.’ Junior doctor, male |

System breakdown was a practical challenge of leadership that many participants spoke about, where even basic resources were in short supply and systems rarely worked as intended. Low salaries for health workers and a lack of job security impacted on motivation and morale and often led staff to work multiple jobs. Entrenched bureaucracy made it difficult to get things done, and doctors in charge of departments or hospitals often lacked the authority to make basic decisions such as reprimanding or firing staff. In some instances, health workers spoke of fearing for their physical safety in hospitals.

Pressure from within the system to do the ‘wrong’ thing was a second important theme. Sometimes this pressure came above, from supervisors or politicians, around how funding was distributed or who was appointed to jobs. This pressure could also come from below or from peers, where requests might be made to hire family members or to allow informal payments to be demanded from patients and shared amongst staff. As well as risking social isolation, resisting this pressure was seen to potentially compromise a person’s career prospects or even result in them losing their jobs, thereby limiting their ability to continue contributing to the health system.

Deep politicization in the health sector overlapped with pressure to do the ‘wrong’ things. Some health professionals were seen to be openly aligned with political parties. This could cause sub-groups to form within teams based on political divisions, resistance to implementing changes advocated by the political opposition, or biased selection of well-connected doctors to leadership positions. Many health workers might also have connections with someone in the ruling party (the so-called power posts) who would protect them from reprimand even when found guilty of misconduct.

A broader lack of accountability in the health sector further contributed to challenges with how staff were appointed or reprimanded. Not only were people in positions of authority unable to hold members of their team accountable, but they themselves were not held accountable by their supervisors for their performance or leadership.

Autocratic approaches to leadership were described negatively by participants and as resulting from both the traditional chieftaincy form of governance in Sierra Leone and by approaches to parenting. This was linked to inadequate consultation during decision-making and a followership style of not speaking truth to power.

Dependency on foreign donors to finance health programmes was perceived as contributing to a lack of proactiveness in problem solving amongst doctors in Sierra Leone, as well as a broader lack of accountability for government.

Personal characteristics was a final theme, including specific challenges faced by female and young doctors, as well as by clinicians, in trying to lead. There was consensus among female participants that women tended to be overlooked in the health sector, including in decision-making and appointments, although none of the participants raised the issue spontaneously. While identity is one aspect of the gender bias they described, it was clearly also an issue of discrimination. Participants also described how younger doctors were often obstructed by seniors when seeking to take on new responsibilities or introduce change. Finally, clinicians described not being respected as leaders if they had not undertaken public health training, creating a major divide within the profession.

As well as describing the contextual challenges, participants also discussed how these could be overcome through particular leadership capabilities, often drawing on their own experiences through lengthy examples. These capabilities are summarized in Figure 3, with examples listed in Table 4.

Figure 3.

Key leadership capabilities to navigate contextual challenges in Sierra Leone. Leadership capabilities (brown boxes) are positioned next to the contextual challenges (orange boxes) they help to overcome.

Table 4.

Examples of leadership capabilities used to overcome contextual challenges faced by doctors in Sierra Leone

| Systems don’t work | ‘When you are working in a setting like Sierra Leone, things don’t happen overnight so fast, not because people are wicked but because systems are not there, processes are not clear, nobody exactly knows how things should move from Point A to Point B, so people are always learning. And, so, you have to help them help you, rather than insist that or think that they are bad people to start with.’ Junior doctor, male |

| Pressure to do the ‘wrong’ things |

‘As a leader, you are seen as somebody who can make things happen, even if it’s not particularly legal or it’s not by the books. And in terms of political interference, it’s more or less the same thing…. And if you want to be a strong leader, you have to resist that. And, unfortunately, I think some people are so protective of their jobs that they are sometimes too willing to accede to the wishes of politicians, or orders from above.’ Senior doctor, male ‘When I get emails, I just send it out to everybody and say “Okay, this is what we have” instead of just working behind it, so that at the end of the day, if you copy those ones into decision making, they already know that information is out there so they’re usually careful with how they push to one side.’ Middle-grade doctor, female |

| Politicization in health sector | ‘You should free your mind from all political.. A leader should be apolitical, we know that’s not ideal anyway, because we know that everyone in some way has their side where they favour, okay? But if you want to be very, very effective, those are the things you should avoid entirely’ Senior doctor, male |

| Lack of accountability |

‘He has never asked us to come to hospital early. But he is always at the hospital at 7am in the morning. So, it tells you as a doctor at the hospital that if the [head of the hospital] is coming to work at seven in the morning, I need to be there at least at eight in the morning, because he may want to see me.’ Senior doctor, male ‘Working in the Sierra Leone setting, especially for the Ministry of Health, you have to have the passion… because there’s no motivation or remuneration or anything that comes with it.’ Middle grade doctor, female ‘You make him feel like he has some role in the management of the hospital, you know? You always tell them that this is not a one man show, everybody’s contribution is equally important, even to the last cleaner.’ Senior doctor, male |

| Autocratic approach | ‘Well, in general, there are two types of leaders. You have leaders who they think they know it all, so they just instruct. They say, you should do this, you should do this, I am the boss. And then you have leaders who think that they are part of the people, they think that they should work together. So usually the leaders that will succeed are those who feel that they are part of the people, they work together, they think that many heads are better than one head.’ Senior doctor, male |

| Donor dependency | ‘Because people were dying [during the Ebola outbreak], they became proactive and they took things in their own hands.. And to achieve all of these things, I mean to save the country. I think it pushed them to go ahead and start it’ Junior doctor, male |

| Personal Characteristics | ‘We are getting a lot more numbers now than usual [of doctors in the public sector], and because it’s a lot more numbers, there’s a lot more consulting, being able to spread your wings a little, because you know there are people who will back me up if something goes wrong.’ Middle-grade doctor, female |

Where systems do not work as expected, participants emphasized the need for persistence and the ability to build relationships with colleagues to cut through ‘red tape’. But when facing pressure to behave unethically, doctors must navigate when to resist, requiring courage and skills in negotiation. Transparent communication, ensuring that information about certain topics was widely shared, was one tactic suggested to provide protection from inappropriate interference. Similarly, remaining neutral was considered essential in dealing with the politicization of the health sector, to not become associated with a political faction, even when a doctor had a surname or prominent relative that linked them to one.

Working in a setting with limited accountability was seen to require a strong intrinsic motivation, along with the ability to motivate others and be an effective role model by being punctual, organized and providing supportive supervision. Empathy also played a role in preventing autocratic styles of leadership from taking root, such as by listening to staff, showing humility, engaging team members in decision-making and supporting. Intrinsic motivation must also translate into being proactive to overcome donor dependency, and participants linked this to the importance of being driven by a wider sense of nationalism and service.

Finally, where personal characteristics was a barrier to doctors being perceived as leaders, participants emphasized the importance of doctors being vocal and standing up for themselves, as well as building networks with peers for mutual support.

Navigating leadership dilemmas

A prominent internal conflict that many participants described was trying to work with integrity while also surviving within the system. The pressures they experienced included expectations to improperly demand payments from patients, to redirect money from public funds towards individuals in government or to give special treatment to staff who were politically well-connected.

A key leadership approach that was emphasized was courage, which was driven by a recognition that doing the right thing would often lead to retribution.

Sometimes you face threats, threats of either losing your job, threats of being victimised in the system as a junior doctor. I remember when we started [an advocacy activity], and there were threats from our senior colleagues saying “You have to stop this, if you don’t stop this then you will repeat your postings”… I remember a colleague was denied a scholarship that he won (Junior doctor, male).

If the pressure became too great or the demand was too egregious, participants gave examples of doctors who had ‘walked away’—which could be from a particular role, from working in the public sector or to leave the country entirely. In some cases, forcing doctors out who attempt to lead seems to have been a deliberate tactic by their colleagues or seniors.

I was the first of the new generation of specialists that came back, and they had their ways of doing things and they had complete control, and this new young boy coming in, and they said ‘he's going to tip the apple cart so they said no, let's get rid of him first’. So they said they're going to send me to [rural district hospital] (Senior doctor, male).

It was also apparent that it was much easier for doctors who had specialist postgraduate training and foreign passports to walk away from their jobs than those that did not and that even the threat of leaving seemed to give them power to resist pressure more easily.

I think that for a lot of people, their job is everything, they need the job, they need the money, so because of that they compromise, and the powers that be, when they know that’s all you depend on … I can leave, I can go and do private practice, I can go abroad, I can do whatever I want. So, I think when they know that you depend on your job, then I think they are more likely to take advantage (Senior doctor, male).

Perhaps the central leadership challenge for doctors in Sierra Leone is therefore that, one way or another, they have to navigate these pressures and decide when to accommodate and when to resist.

To be honest with you, it’s a difficult question, but to be honest with you, in my very clear opinion, I think if you are entirely free from those things, you will not survive (Junior doctor, male).

You may have to, I won’t really call it compromise, but I think you probably may have to accommodate certain things which should not be illegal, but perhaps you can alter things to accommodate the wishes of some people, provided that is not going to be strictly out of your plan, okay? In other words, you can bend but you cannot and should not bend to the point of breaking (Senior doctor, male).

In summary, our study found that participants viewed leadership as an individualized phenomenon linked to authority, and largely had the opinion that leadership by doctors was currently a weakness in Sierra Leone. Medical leadership as seen as having an important impact on the health system through its effects on the quality of patient care influences on the health workforce and the development of new services. Participants described effective leadership according to the four major themes of managerial, servant/humble, transformational and relational approaches. The importance of overcoming specific contextual challenges was emphasized, along with leadership dilemmas that requires careful navigation.

Discussion

Our study explored perceptions around effective leadership by doctors in Sierra Leone, including how leadership is conceptualized and the impact that leadership has on the health system and on wider society. In doing so, we address important gaps in the literature about leadership in healthcare in Sub-Saharan African that can inform efforts to strengthen leadership.

Our analysis provides insights into three main areas. First, we consider how this study can inform debates around ‘African leadership’ and whether international models of leadership are relevant outside of the regions where they were developed. Second, we explore how situational leadership theory is relevant to our findings, including the need to broaden classical frameworks of situational leadership and how situational leadership can be considered to complement rather than compete with other international leadership models. Third, we discuss the importance of identifying and addressing contextual challenges to effective leadership, which make leadership development a necessary but insufficient approach to strengthening leadership in health systems.

In exploring whether there were perceived to be distinctive characteristics of effective leadership by doctors in this particular setting, Sierra Leone, our study touches on a broader debate about whether leadership is influenced by culture, and furthermore, whether there is a particular style of ‘African leadership’. In their critique of Western leadership models, which they argue are ethnocentric and present a North American view of the workplace, Blunt and Jones make a proposal for a particular profile of African leadership. They suggest, for example, that in Africa, family wealth can be legitimately acquired at the expense of the organization, and as such vision may be out of place. Due to how power is centralized, Blunt and Jones argue that the role of the leader is primarily to implement directives they receive from their seniors. They note the role age plays in leadership identity, positing that African societies are egalitarian within age groups but hierarchical between them (Blunt and Jones, 1997).

Our study both supports and contradicts this theory. Some features described by Blunt and Jones were identified by our participants as being how things currently operate in the health system in Sierra Leone, such as relating to corruption, centralized decision-making and the suppression of leadership by younger doctors. However, these approaches were explicitly rejected in terms of how they thought effective leadership should be practiced. Instead of viewing vision as out of place, participants in our study emphasized its importance and largely embraced transformational approaches to leadership. Autocratic approaches to leadership were acknowledged but criticized as damaging and to be avoided.

Blunt and Jones’s profile has also been critiqued by Bolden, who described it as a ‘negative and generalized picture’. Bolden’s research identified a very different framing of African leadership as being grounded in ‘ubuntu’, a concept of interdependence that puts more emphasis on collective leadership (Bolden, 2009). A similar view was adopted by Haruna, who argued that African leadership studies focused too much on bureaucratic and managerial leadership, which he argued overemphasizes the concept of individualistic leadership in a way that does not account for lived experience on the continent. Instead he advocates for community-based leadership models (Haruna, 2009). Again, this theory was not supported by our study, where participants largely described an individualistic framing for leadership and advocated for managerial capabilities as important for effective leadership—although it is worth noting the emphasis that participants placed on the importance of engaging colleagues in decision-making and trying to reach consensus, which hint at value being placed on a more collective leadership approach.

Instead, participants in our study largely challenged the notion of a unique preferred African leadership style, with their descriptions of an ideal leadership approach conforming closely to established international models of leadership. While participants emphasized the need to navigate the context of the health system in Sierra Leone, by and large the contextual factors described were not innately ‘African’ but related to issues (such as donor dependency or systems not working) that are experienced in other regions and are likely to change over time. Indeed, one participant in our research commended after their interview that they felt it was inappropriate to even ask whether there was anything distinctive about effective leadership in Sierra Leone. Bolden describes a strikingly similar scenario from his research where in one interview ‘the question itself [was] considered inappropriate and “African leadership” perceived as holding discriminatory undertones’ (Bolden, 2009).

The alignment of our participants views on effective leadership with international models might in part be explained by how markedly internationalized the medical profession is. Sierra Leone’s health system has its foundations in British colonial structures (see Box 2) and, notably, of the 14 doctors we interviewed, 13 had undertaken some medical training abroad. There is perhaps not enough evidence from our study, however, to conclude that perceptions of effective leadership by doctors is shaped more by the global norms of their profession than by the norms of Sierra Leonean society; indeed, such a finding would contradict a main conclusion of the GLOBE study, which saw stronger correlations in leadership views within particular countries and regions than across particular industries (House et al., 2004).

The second key finding of our study was that, while their leadership ideals conformed to international models, participants stressed that specific contextual challenges faced by doctors in Sierra Leone required particular leadership capabilities to navigate. This emphasize on adapting to context broadly aligns with situational leadership theory. On its face, this may appear to set up a contradiction between support for generalized and localized models of leadership. However, we would argue that a situational approach to leadership can instead be considered complementary with generalized international models of leadership. Where those generalized models of leadership (transformational, relational, etc.) describe the ‘what’ of how participants thought effective leadership should ideally look, situational leadership theory explains ‘how’ those models needed to be translated to accommodate for the context of Sierra Leone’s health system. Drath et al. (2008) similarly integrated generalized and situational leadership theories into a single model in their ‘direction, alignment and commitment’ approach, whereby individual and collective beliefs (in our case, generalized models) are translated into leadership practice through the medium of the context and leadership culture (situational leadership).

While our study therefore draws heavily on situational leadership theory, it also expands its most common definition. Classical situational leadership theories, developed by Fiedler, Blanchard and others, focused on the need to adapt leadership styles based on the nature of the task and the relationship between leaders and their followers (Singer and Singer, 1990). Our study builds on situational leadership theory by showing that, for doctors in Sierra Leone, leadership style must also be adapted based on the relationship leaders have with their peers and superiors, as well as other influential people with whom they have an informal relationship. This is demonstrated by contextual challenges such as the pressure to do the ‘wrong’ things and the politicization of the health sector.

This emphasis on context raises the question of to what extent the findings of our study are relevant to other settings. While the specific findings maybe not be generalizable, our research shows the importance of conducting in-depth study on a particular health system’s context prior to the design or implementation of policies or programmes to strengthen healthcare leadership. Furthermore, by mapping key leadership skills against the contextual factors they relate to, such as the importance of initiative in settings that are heavily donor-dependent, the findings may be extrapolated to settings where contextual challenges are similar.

Another important finding from our research is that the pressure put on doctors to do the ‘wrong’ thing causes many to leave the country’s health system entirely. If doctors that are practicing effective leadership routinely feel they have no choice but to leave the public health sector in order to maintain their integrity that will clearly prevent them from continuing to fight for change within the system. This serves as a reminder that introducing leadership development programmes for health professionals might be a necessary but ultimately insufficient intervention to strengthen leadership unless the systemic barriers to effective leadership, including those related to power and politicization, are also addressed.

Limitations

The study was based primarily on qualitative interviews with 14 participants, with follow up interviews with a further 14 doctors, and the relatively small sample size could have resulted in additional concepts or perspectives being missed. However, the sample was diverse and saturation was reached, suggesting that the findings are broadly representative. Furthermore, the analysis was informed by years of observation in the country’s health sector by OJ and FS. The sample only included medical doctors, and representation from other health professional cadres and non-health professionals might have elicited a more holistic picture of leadership by doctors.

A snowballing approach was used to recruit participants, which can introduce bias by directing participant selection to a particular in-group or social or professional network, but can also, by nature of its organic formation, help illuminate internal social dynamics and interrelationships of those groups (Noy, 2008). We sought to mitigate the inherent limitations of this approach by initially targeting participants who we believed would hold diverse perspectives (including different levels of seniority and those who were considered allied to the Ministry of Health and Sanitation and those who were perceived to challenge the establishment). We were also explicit when seeking advice on recruiting additional participants about the diverse range of roles, experiences and perspectives that were our criteria for selection.

The study focused specifically on leadership by doctors, rather than other health professionals. This was neither to privilege the importance of leadership by this cadre of health professional nor to suggest that doctors lead independently of their colleagues, but rather to recognize the distinctive training, identities and roles that doctors experience. These findings are therefore specific to medical doctors and further research would be required to assess whether they are generalizable to other health professionals.

The findings of the study are specific to Sierra Leone and may not be generalizable to other countries. However, by identifying some of the contextual factors about the health sector in Sierra Leone that influenced leadership, the study may allow for researchers to consider whether some findings are relevant to other settings where similar dynamics are observed.

Implications for policy and practice

This study has implications for policy and practice around healthcare leadership, in particular around the design of leadership development programmes and the establishment of a more enabling environment for medical leadership by national governments and international health donors.

Our research can inform the design and delivery of leadership development programmes, for doctors in Sierra Leone and more broadly. The key leadership capabilities we identify should be targeted for improvement in curriculum design. Such programmes should also address the issue of dualling identities that doctors hold between clinical practice and public health and reinforce the voices of women in leadership. Furthermore, leadership programmes should also engage senior doctors, who act as role models and gate keepers for younger generations and influence whether their strengthened leadership capabilities can be put into practice.

Importantly, such leadership programmes must take into account the challenges that doctors face when trying to lead, and the courage and risks this involves. Our research shows that careful navigation and judicious accommodation by doctors in how they lead may be necessary to survive in the health system, while recognizing that at other times it is important to stand firm. Teaching a more textbook approach to decision-making, where there are simple rights and wrongs, may not reflect the realities on the ground or help doctors to steer through the dilemmas that they face. By supporting repeated cohorts of doctors to develop their leadership, a network may form that achieves critical mass and provides a level of protection to doctors who are advocating for change.

This research can also assist policymakers in addressing the contextual challenges that act as barriers to effective leadership, be that the lack of strong systems or the dynamics of donor dependency. Critical to this is establishing a culture where effective and courageous medical leadership is protected and encouraged by senior officials in government and the health sector, rather than shut down or punished.

Future research

This study shows the value of conducting in-depth case studies in specific contexts to inform local development of training programmes and health policies, as well as to provide insights into leadership by doctors more broadly. Additional such studies in other countries and settings, as well as amongst other cadres of health professional, would establish whether the findings of this research are generalizable or whether effective leadership should be viewed as a highly situational phenomenon that will always needed to be grounded in the local context.

Furthermore, the findings of this study should be built on by translating them into the design of a leadership development programme in Sierra Leone and evaluating its effectiveness, to establish whether such studies can impact on improving outcomes in the health system.

Finally, our research also identified the risks faced by doctors in trying to lead, including the compromises they may need to make or the pressures they may experience pushing them to leave the country. The critical issue of how courage is understood—whether as speaking up or ‘walking away’—requires more nuanced theoretical elaboration and should be explored in greater empirical detail. Similarly, further research is needed to understand how the barriers to leadership, including those related to power and politicization, can be addressed.

Conclusion

This study provides an in-depth case study on perceptions of effective leadership by doctors in Sierra Leone—which is the first such analysis to our knowledge. The findings can inform both our theoretical understanding of leadership in this setting and give practical insights into leadership programmes and policies. Further research should aim to evaluate the presence and pattern of the themes we identified in other Sub-Saharan African countries and thereby develop a more widely generalizable evidence base.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Mohamed Boie Jalloh and David Gbao in providing valuable feedback on early drafts of this paper.

Endnotes

One participant was split between Ministry and University so is counted in each category.

Contributor Information

Oliver Johnson, Centre for Implementation Science, Health Services and Population Research Department, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, David Goldberg Centre, De Crespigny Park, London SE5 8AF, UK; Centre for Health Policy, School of Public Health, University of Witwatersrand, 60 York Road, 2193 Johannesburg, South Africa.

Foday Sahr, Department of Microbiology, College of Medicine and Allied Health Sciences, University of Sierra Leone, 12 Victoria Street, Kossoh Town, Freetown, Sierra Leone; Joint Medical Unit (34 Military Hospital), Wilberforce Barracks, Wilberforce Village, Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Kerrin Begg, School of Public Health and Family Medicine, University of Cape Town, Falmouth Building, Anzio Road, Cape Town 7925, South Africa.

Nick Sevdalis, Centre for Implementation Science, Health Services and Population Research Department, Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience, King’s College London, David Goldberg Centre, De Crespigny Park, London SE5 8AF, UK.

Ann H Kelly, Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, School of Global Affairs, Faculty of Social Science & Public Policy, King’s College London, London WC2R 2LS, UK.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Health Policy and Planning online

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, OJ. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Funding

NS, AHK and OJ are supported by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Research Unit on Health System Strengthening in Sub-Saharan Africa, King’s College London (GHRU 16/136/54) using UK aid from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. NS’ research is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) South London at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. NS is a member of King’s Improvement Science, which offers co-funding to the NIHR ARC South London and is funded by King’s Health Partners (Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, King’s College London and South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust), Guy’s and St Thomas’ Charity and the Maudsley Charity. NS’ research is further supported by the ASPIRES research programme (Antibiotic use across Surgical Pathways - Investigating, Redesigning and Evaluating Systems), funded by the Economic and Social Research Council. AHK also receives support from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, investigating the Design and Use of Diagnostic Devices in Global Health (DiaDev), under grant agreement No 715450. Finally, she receives support from MRC-AHRC as part of their GCRF programme for HAPPEE, a project on preventing pre-eclampsia complications through community engagement and education, (ref: MC_PC_MR/R024510/1).

Ethical approval

The study received ethical approval from both the Psychiatry, Nursing and Midwifery Research Ethics Subcommittee at King’s College London, UK (LRS-18/19-10994) and the Sierra Leone Ethics and Scientific Review Committee.

Conflict of interest statement

NS is the director of the London Safety and Training Solutions Ltd., which offers training in patient safety, implementation solutions and human factors to healthcare organizations. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Belrhiti Z, Giralt AN, Marchal B. 2018. Complex leadership in healthcare: a scoping review. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 7: 1073–84.doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blunt P, Jones ML. 1997. Exploring the limits of Western leadership theory in East Asia and Africa. Personnel Review 26: 6–23.doi: 10.1108/00483489710157760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolden R. 2009. African leadership: surfacing new understandings through leadership development. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 9: 69–86.doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary S, Du Toit A, Scott V, Gilson L. 2018. Enabling relational leadership in primary healthcare settings: Lessons from the DIALHS collaboration. Health Policy and Planning 33: ii65–ii74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. 2008. Basics of Qualitative Research (3rd Ed.): Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.doi: 10.4135/9781452230153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings GG, Tate K, Lee S. et al. 2018. Leadership styles and outcome patterns for the nursing workforce and work environment: a systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies 85: 19–60.doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie G, Lockett A. 2007. A critique of transformational leadership: Moral, professional and contingent dimensions of leadership within public services organizations. Human Relations 60: 341–370. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]