Abstract

Background:

The extent to which heightened distress during the COVID-19 pandemic translated to increases in severe mental health outcomes is unknown. We examined trends in psychiatric presentations to acute care settings in the first 12 months after onset of the pandemic.

Methods:

This was a trends analysis of administrative population data in Ontario, Canada. We examined rates of hospitalizations and emergency department visits for mental health diagnoses overall and stratified by sex, age and diagnostic grouping (e.g., mood disorders, anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders), as well as visits for intentional self-injury for people aged 10 to 105 years, from January 2019 to March 2021. We used Joinpoint regression to identify significant inflection points after the onset of the pandemic in March 2020.

Results:

Among the 12 968 100 people included in our analysis, rates of mental health–related hospitalizations and emergency department visits declined immediately after the onset of the pandemic (peak overall decline of 30% [hospitalizations] and 37% [emergency department visits] compared to April 2019) and returned to near prepandemic levels by March 2021. Compared to April 2019, visits for intentional self-injury declined by 33% and remained below prepandemic levels until March 2021. We observed the largest declines in service use among adolescents aged 14 to 17 years (55% decline in hospitalizations, 58% decline in emergency department visits) and 10 to 13 years (56% decline in self-injury), and for those with substance-related disorders (33% decline in emergency department visits) and anxiety disorders (61% decline in hospitalizations).

Interpretation:

Contrary to expectations, the abrupt decline in acute mental health service use immediately after the onset of the pandemic and the return to near prepandemic levels that we observed suggest that changes and stressors in the first 12 months of the pandemic did not translate to increased service use. Continued surveillance of acute mental health service use is warranted.

There has been widespread concern about the mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.1 Social isolation, financial strain, school closures and the stress of possible infection and its consequences all serve as risk factors for new onset or exacerbation of existing mental illnesses and substance use disorders. Survey data and polling suggest that people are endorsing higher rates of distress, substance use, anxiety and depressive symptoms during the pandemic. 2,3 In multiple jurisdictions, early data demonstrate a universal decline in routine preventive health visits and acute care use for physical health concerns, likely driven by fear of infection risk and decreased accessibility of health services.4–6 Whether there have been changes in service use for acute mental health and substance use disorders (including visits for intentional self-injury when individuals may be experiencing distress but have not yet been diagnosed with a mental disorder) is still largely unknown. Understanding this gap is important for health system planning and service delivery.

One large population-based study in the United States showed that following an initial brief decline, emergency department visits for mental health conditions and suicide attempts across all age groups increased in the first 28 weeks after the onset of the pandemic.7 Another large pediatric study in the United States showed an acute decline in mental health hospitalizations in the first 3 months after the onset of the pandemic compared to the previous decade.8 These contrasting data suggest that there may be variation in the extent to which different age or diagnostic groups have been affected. Outside of the United States, few reports have been published at a population level on acute mental health care service use after the onset of the pandemic, and different jurisdictions and health systems may have had varying responses.9,10

The objective of this study was to describe trends in service use for acute mental health and substance use disorders before and during the first 12 months after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (April 2020 to March 2021) in Ontario, the most populous province in Canada. Specifically, we described trends in emergency department visits and hospitalizations for mental health and substance use disorders, as well as emergency department visits for intentional self-injury across the lifespan. Given the reported distress2 and concerns about the impact of the pandemic on well-being, we hypothesized that mental health–related acute care visits would increase in the early phases of the pandemic.

Methods

Study design and setting

In this trend analysis of administrative population data, we included all people between the ages of 10 years (the age after which most mental health system use occurs11) and 105 years who were living in Ontario, Canada, who had a valid health card, and for whom information on sex and age was available, from Jan. 1, 2019, to Mar. 31, 2021. This study followed the Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely Collected Health Data (RECORD) reporting guideline.12

Data sources

We used the Registered Persons Database — the central population registry file that enables linkage across population-based health administrative data sets — to identify all Ontario residents who were insured under Ontario’s universal health coverage and to ascertain age and sex information at the time of their acute care visit.

We used the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System to identify emergency department visits for mental health or substance use disorders, and we used the Canadian Institute for Health Information’s Discharge Abstract Database and Ontario Mental Health Reporting System to capture psychiatric hospitalizations. The National Ambulatory Care Reporting System and the Discharge Abstract Database use the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, with Canadian enhancements (ICD-10-CA), and the Ontario Mental Health Reporting System uses the multiaxial Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5).13 For all emergency department visits, we included only unscheduled visits, because in rural settings, primary care is occasionally provided via the emergency department; such visits are coded as “scheduled” and were excluded.

ICES data are valid for sociodemographic characteristics, physician billings claims and primary hospital diagnoses. 14 Data sets were linked using unique coded identifiers and analyzed at ICES, an independent, nonprofit research institute.

Outcomes

We identified emergency department visits and hospitalizations for mental health and substance use disorders using a primary diagnosis of ICD-10-CA codes F06 to F99. Any DSM-5 codes in the Ontario Mental Health Reporting System, (excluding 290.x and 294.x, neurocognitive disorders without mental health and addictions–related diagnosis) were considered hospitalizations for mental health or substance use disorders. We further classified emergency department visits and hospitalizations for mental health and substance use disorders according to the most common broad diagnostic categories based on the primary or main diagnosis: substance-related and addictive disorders; schizophrenia spectrum and psychotic disorders; anxiety disorders; mood disorders; and trauma and stressor-related disorders (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/4/E988/suppl/DC1). For emergency department visits and hospitalizations, we also identified visits for intentional self-injury, where diagnostic codes included ICD-10-CA codes X60 to X84, Y10 to Y19 and Y28.

The codes we used to identify mental health visits are widely used for mental health system performance measurement in Ontario and elsewhere in Canada. The specific diagnostic grouping codes have been validated for some diagnostic groups, but not all.15–20 Among visits to the emergency department for self-injury, we further measured the proportion that resulted in a hospitalization, an intensive care unit admission, or death during the index emergency department visit as proxies for illness severity.

Statistical analysis

We calculated crude monthly rates for emergency department visits and hospitalizations for mental health or substance use disorders (per 1000 people) and emergency department visits for self-injury (per 10 000 people) from Jan. 1, 2019, to Mar. 31, 2021 — overall and stratified by sex, age and diagnostic grouping (determined a priori). We used Joinpoint analysis software21 version 4.7.0.0 to identify significant inflection points in 2020 in the time trends for overall emergency department visits and hospitalizations for mental health and substance use disorders, and we tested statistical significance using the Monte Carlo permutation method.21 An α value of 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Ethics approval

Data use was authorized under section 45 of Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act, which does not require research ethics board review.

Results

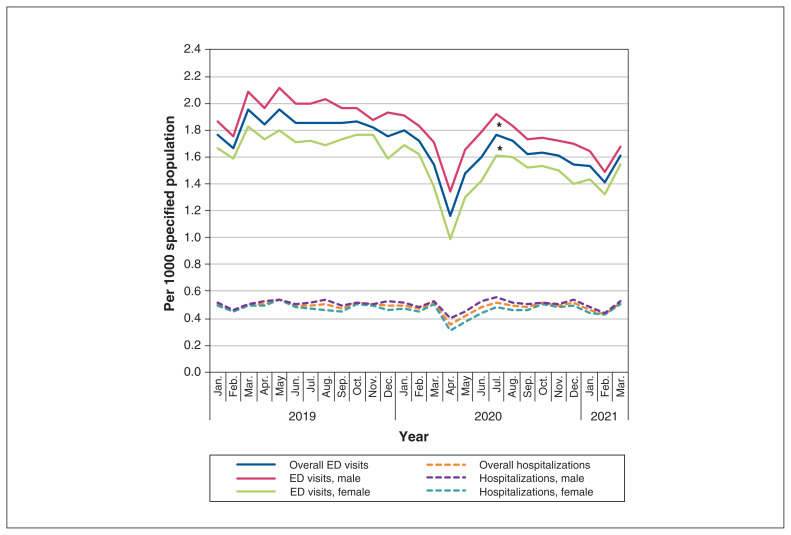

Among the 12 968 100 people living in Ontario (Table 1 and Appendix 2 eFigure 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/4/E988/suppl/DC1), we observed a decrease in emergency department visits for mental health and substance use disorders in March and April 2020, followed by a rapid return to almost prepandemic rates in July 2020 (Figure 1). Rates dropped by 37%, from 1.66 to 1.05 visits per 1000 population in April 2020 compared to April 2019 (Table 2). Joinpoint regression analysis showed significant changes in slope in July 2020 (p ≤ 0.05). We also observed a sharp decrease of 30% in hospitalizations for mental health and substance use disorders in April 2020 (from 0.51 per 1000 in April 2019 to 0.35 per 1000 in April 2020) and a return to prepandemic levels in June 2020 (Figure 1, Table 2).

Table 1:

Ontario population included in study

| Category | Jul. 1, 2019 n = 12861929 |

Jul. 1, 2020 n = 12968100 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | ||

| 10–13 | 644504 | 641219 |

| 14–17 | 626125 | 630603 |

| 18–21 | 651962 | 641377 |

| 22–24 | 541009 | 531054 |

| 25–44 | 3884488 | 3938038 |

| 45–64 | 3975434 | 3962333 |

| 65–105 | 2538407 | 2623476 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 6278495 | 6320837 |

| Female | 6583434 | 6647263 |

Figure 1:

Emergency department visits and hospitalizations related to mental health and substance use disorders per 1000 population aged 10 to 105 years. Joinpoint regression analysis identified a statistically significant change in slope at July 2020 (*p ≤ 0.05) among overall and male visits to emergency departments. We observed a decrease in hospitalizations related to mental health and substance use disorders for both sexes in April 2020. Joinpoint regression analysis did not yield any significant changes in slope. Note: ED = emergency department.

Table 2:

Emergency department visits and hospitalizations for mental health and substance use disorders and intentional self-injury by age and diagnosis, April 2019 to April 2020

| Category | Mean N monthly visits* (January 2019 to March 2021) | Per population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 2019 | April 2020 | % Relative change | ||

| Emergency department visits by age | Per 1000 population | |||

| All ages | 21926 | 1.66 | 1.05 | −37 |

| 10–13 yr | 461 | 1.01 | 0.29 | −71 |

| 14–17 yr | 1617 | 3.27 | 1.36 | −58 |

| 18–21 yr | 2347 | 3.84 | 2.36 | −38 |

| 22–24 yr | 1769 | 3.70 | 2.19 | −41 |

| 25–44 yr | 9269 | 2.47 | 1.75 | −30 |

| 45–64 yr | 4957 | 1.32 | 0.88 | −33 |

| 65–105 yr | 1506 | 0.66 | 0.37 | −44 |

| Hospitalizations by age | Per 1000 population | |||

| All ages | 6294 | 0.51 | 0.35 | −30 |

| 10–13 yr | 156 | 0.28 | 0.09 | −69 |

| 14–17 yr | 594 | 1.16 | 0.52 | −55 |

| 18–21 yr | 584 | 0.95 | 0.64 | −33 |

| 22–24 yr | 459 | 0.91 | 0.63 | −32 |

| 25–44 yr | 2459 | 0.63 | 0.50 | −20 |

| 45–64 yr | 1508 | 0.39 | 0.29 | −28 |

| 65–105 yr | 535 | 0.21 | 0.14 | −32 |

| Intentional self-injury by age | Per 10 000 population | |||

| All ages | 1839 | 1.61 | 1.08 | −33 |

| 10–13 yr | 58 | 1.18 | 0.51 | −56 |

| 14–17 yr | 282 | 5.17 | 3.16 | −39 |

| 18–21 yr | 273 | 4.48 | 3.12 | −30 |

| 22–24 yr | 168 | 4.21 | 2.35 | −44 |

| 25–44 yr | 632 | 1.86 | 1.26 | −32 |

| 45–64 yr | 335 | 0.85 | 0.67 | −22 |

| 65–105 yr | 92 | 0.36 | 0.30 | −15 |

| Emergency department visits by diagnosis | Per 1000 population | |||

| Substance-related and addictive disorders | 6819 | 0.56 | 0.38 | −32 |

| Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders | 2289 | 0.17 | 0.16 | −6 |

| Mood disorders | 3242 | 0.29 | 0.13 | −55 |

| Anxiety disorders | 3984 | 0.34 | 0.21 | −37 |

| Trauma and stressor-related disorders | 2770 | 0.25 | 0.13 | −47 |

| Hospitalizations by diagnosis | Per 1000 population | |||

| Substance-related and addictive disorders | 1424 | 0.11 | 0.09 | −22 |

| Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders | 1389 | 0.11 | 0.09 | −14 |

| Mood disorders | 1707 | 0.15 | 0.08 | −43 |

| Anxiety disorders | 231 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −61 |

| Trauma and stressor-related disorders | 469 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −32 |

Mean monthly visits are the total number of visits in each stratum divided by the number of study months.

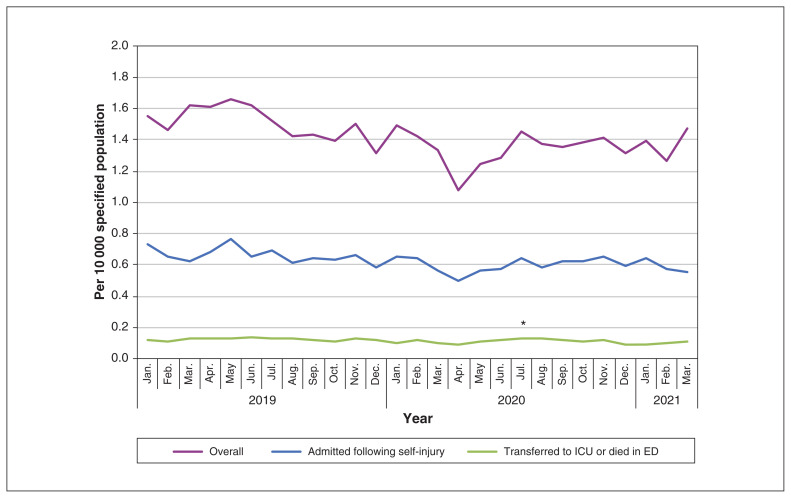

The rate of emergency department visits for intentional self-injury dropped by 33% in April 2020 compared to April 2019 and had returned to near prepandemic levels by August 2020 (Figure 2, Table 2). The proportion of emergency department visits for intentional self-injury that resulted in hospitalization or in intensive care unit admission or death was lower after March 2020 and remained well below prepandemic levels through March 2021 (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Emergency department visits for intentional self-injury, as well as admission rates and ICU or death rates per 10 000 population aged 10 to 105 years. We observed a decrease in emergency department visits for intentional self-injury in April 2020 among those who were admitted following self-injury and among those who were transferred to the ICU or died in the emergency department. Joinpoint regression analysis identified a statistically significant change in slope in July 2020 (*p ≤ 0.05) among those who were transferred to the ICU or died in the emergency department. Note: ED = emergency department, ICU = intensive care unit.

Sex differences

Although females generally had lower rates of emergency department visits and hospitalizations than males, patterns by sex mirrored those of the main analysis (Figure 1, Appendix 2 eTable 1). For both sexes, emergency department visits remained below 2019 levels, but hospitalizations had returned to prepandemic levels by June 2020.

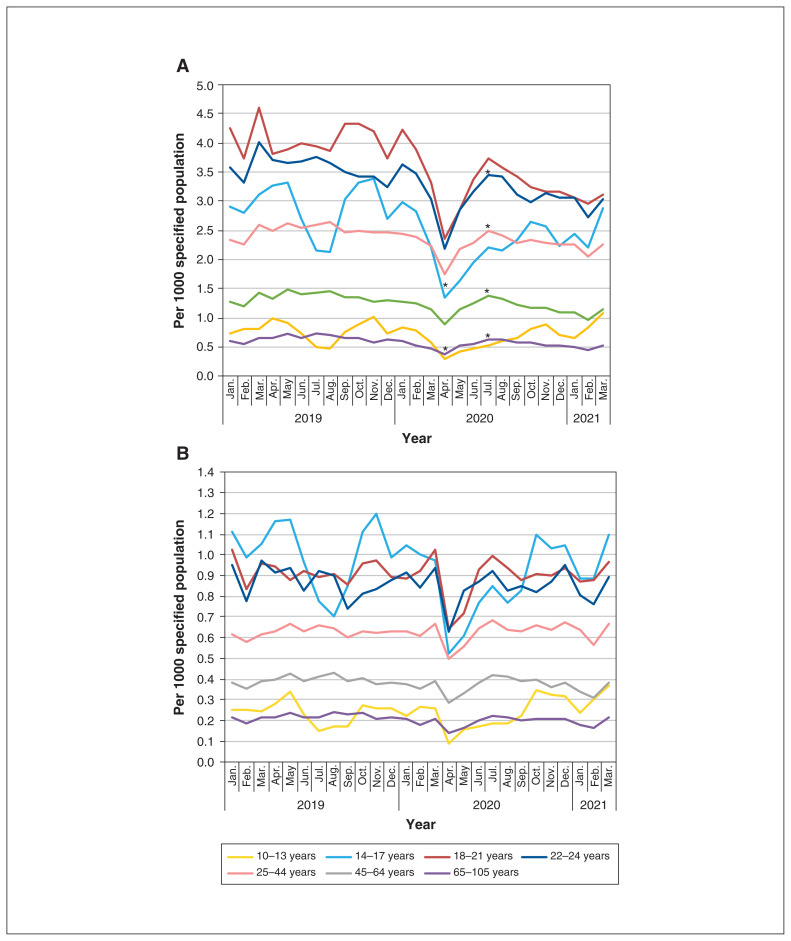

Age differences

By age, the observed decrease in emergency department visits for April 2020 was greatest among youth between the ages of 10 and 21 years; among those aged 14 to 21 years, health service use did not return to prepandemic levels by March 2021 (Figure 3, Tables 2 and 3). Mental health and addictions–related hospitalizations among children and youth (10 to 24 years) decreased by 32% (22- to 24-year-olds) to 69% (10- to 13-year-olds) in April 2020 compared to April 2019 (Table 2) and had not returned to prepandemic levels by March 2021, except for those aged 10 to 13 years (Figure 3, Table 3).

Figure 3:

(A) Emergency department visits and (B) hospitalizations related to mental health and substance use disorders per 1000 population aged 10 to 105 years, by age. For emergency department visits, joinpoint regression analysis identified statistically significant changes in slope in April 2020 (*p ≤ 0.05) for those aged 10 to 17 years and in July 2020 for those aged 18 to 21 years and those aged 25 to 105 years. For hospitalizations, we observed a decrease among all age groups in April 2020. Joinpoint regression analysis did not yield any significant changes in slope.

Table 3:

Monthly rates of acute mental health use by age group, April 2020 to March 2021

| Acute mental health use | Apr. | May | Jun. | Jul. | Aug. | Sep. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. | Jan. | Feb. | Mar. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency department visits per 1000 population | ||||||||||||

| All ages | 1.16 | 1.47 | 1.60 | 1.76 | 1.71 | 1.62 | 1.63 | 1.61 | 1.55 | 1.54 | 1.41 | 1.61 |

| 10–13 yr | 0.29 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.82 | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.84 | 1.08 |

| 14–17 yr | 1.34 | 1.63 | 1.95 | 2.21 | 2.16 | 2.32 | 2.64 | 2.57 | 2.22 | 2.43 | 2.21 | 2.89 |

| 18–21 yr | 2.36 | 2.85 | 3.38 | 3.73 | 3.57 | 3.41 | 3.24 | 3.17 | 3.18 | 3.06 | 2.95 | 3.11 |

| 22–24 yr | 2.18 | 2.86 | 3.18 | 3.45 | 3.42 | 3.11 | 2.99 | 3.14 | 3.06 | 3.05 | 2.73 | 3.04 |

| 25–44 yr | 1.75 | 2.18 | 2.28 | 2.49 | 2.40 | 2.28 | 2.33 | 2.29 | 2.26 | 2.26 | 2.04 | 2.25 |

| 45–64 yr | 0.89 | 1.13 | 1.24 | 1.37 | 1.34 | 1.22 | 1.18 | 1.16 | 1.08 | 1.09 | 0.97 | 1.15 |

| 65–105 yr | 0.37 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.53 |

| Hospitalizations per 1000 population | ||||||||||||

| All ages | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.52 |

| 10–13 yr | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.37 |

| 14–17 yr | 0.52 | 0.61 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 1.10 | 1.03 | 1.05 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 1.10 |

| 18–21 yr | 0.64 | 0.72 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.96 |

| 22–24 yr | 0.63 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.92 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.95 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.89 |

| 25–44 yr | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.56 | 0.67 |

| 45–64 yr | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.38 |

| 65–105 yr | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.21 |

| Intentional self-injury per 10 000 population | ||||||||||||

| All ages | 1.08 | 1.24 | 1.29 | 1.45 | 1.38 | 1.36 | 1.38 | 1.41 | 1.31 | 1.39 | 1.27 | 1.47 |

| 10–13 yr | 0.51 | 0.41 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.84 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 1.37 | 0.95 | 1.28 | 1.31 | 1.56 |

| 14–17 yr | 3.16 | 3.36 | 3.39 | 3.92 | 3.54 | 4.00 | 5.09 | 4.80 | 4.41 | 4.98 | 4.65 | 6.00 |

| 18–21 yr | 3.12 | 3.80 | 4.16 | 4.83 | 4.01 | 4.02 | 3.60 | 3.49 | 3.74 | 3.92 | 3.79 | 3.89 |

| 22–24 yr | 2.35 | 2.98 | 3.13 | 3.20 | 3.24 | 3.14 | 2.67 | 3.33 | 2.96 | 2.79 | 2.90 | 3.13 |

| 25–44 yr | 1.26 | 1.47 | 1.50 | 1.63 | 1.64 | 1.54 | 1.61 | 1.57 | 1.52 | 1.62 | 1.42 | 1.62 |

| 45–64 yr | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.94 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.72 | 0.77 | 0.64 | 0.78 |

| 65–105 yr | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.31 |

Among adults aged 25 and older, the rate of hospitalizations dropped by 20% to 32% in April 2020 and had returned to prepandemic levels by June 2020. For emergency department visits for intentional self-injury, we observed the greatest year-over-year decrease among those aged 10 to 24 years (30% to 56%), and rates had generally returned toward prepandemic levels by July 2020.

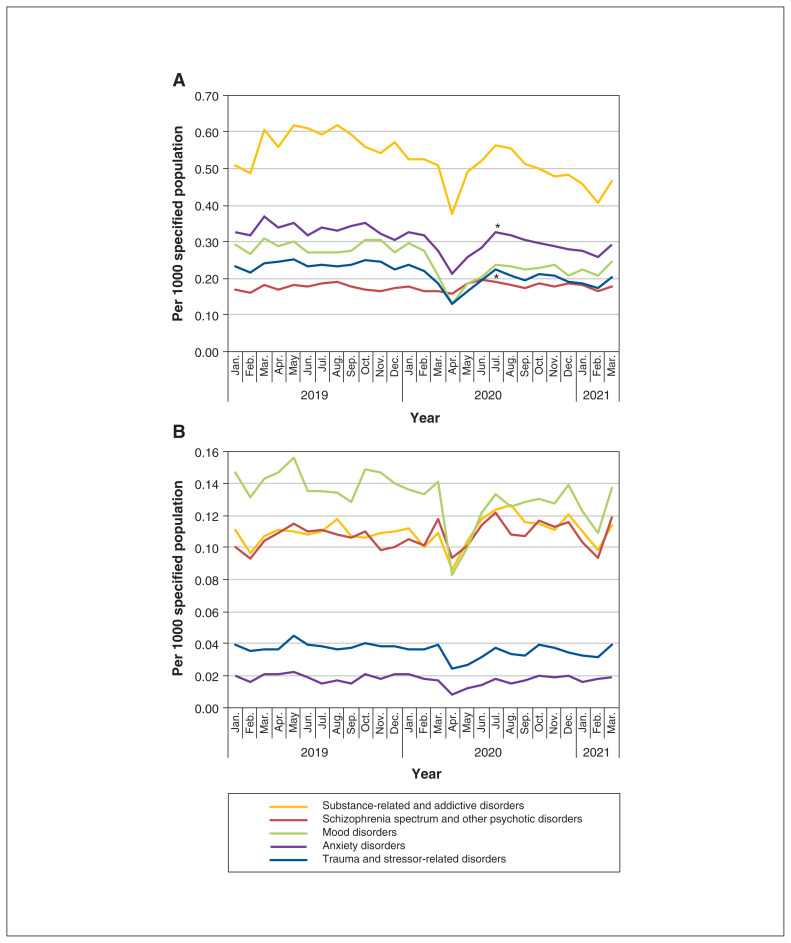

Diagnostic grouping

We observed decreases in emergency department visit rates across most diagnostic groups, except for those with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. For people with these conditions, we found a significant inflection point (p ≤ 0.05) with an increase in July 2020. (Figure 4, Table 2). For all diagnostic groupings except schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, visit rates returned toward prepandemic levels in the fall of 2020 but had not reached prepandemic levels as of March 2021.

Figure 4:

(A) Emergency department visits and (B) hospitalizations related to mental health and substance use disorders per 1000 population aged 10 to 105 years, by diagnosis. Joinpoint regression analysis identified statistically significant changes in slope in July 2020 (*p ≤ 0.05) in emergency department visits for anxiety, schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders, and trauma and stressor-related disorders. We observed a decrease in hospitalizations across all diagnostic categories in April 2020, but joinpoint regression analysis did not yield any significant changes in slope.

Hospitalizations were most common for mood disorders, and this diagnostic group had the greatest absolute drop in hospitalization rate, which had not returned to prepandemic levels by June 2020 (Figure 4). Trauma and stressor-related hospitalizations, while less common, followed a pattern similar to that of mood disorders. For the 2 other most prevalent hospitalization types by diagnosis (schizophrenia spectrum and psychotic disorders, and substance-related and addictive disorders), rates dropped after March 2020 and had returned to prepandemic levels by June 2020.

Interpretation

Our study found that the rates of service use for acute mental health and substance use disorders (in the form of emergency department visits, hospitalizations and visits for intentional self-injury) experienced a drop immediately following the onset of the pandemic and related public health measures, followed by a return toward (but not up to) prepandemic levels within 12 months. We observed exceptions among youth aged 14 to 24 years (for whom rates of emergency department visits and hospitalizations did not return to prepandemic levels by March 2021) and for those who were admitted to an intensive care unit or died during the emergency department visit following intentional self-injury.

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic came concerns about infection and related consequences; social isolation as part of public health measures; school closures; impacts on economies with related financial stress; and other factors that could contribute to increased incidence of and worsening of existing mental illnesses and addictions. There was also a substantial shift in the way mental health and addictions services are delivered, with a rapid transition from mostly in-person care to virtual care.6,22 The persistently low rate of hospitalizations and intensive care unit admissions or deaths for self-injury that we observed following the pandemic suggests that there may have been a reduction in the lethality of presentations, changes in admission thresholds, changes in the suitability of and inclination to use ambulatory care instead of acute care for some mental health disorders, or alterations in system capacity.

Taken together, our findings suggest that the concerns about mental health and substance use disorders2 associated with the COVID-19 pandemic did not translate into increased emergency department visits, hospitalizations or emergency department visits for intentional self-injury, at least in the 12 months following the onset of the pandemic in Ontario, Canada. The absence of increased acute mental health and addictions service use after March 2020 does not mean that the pandemic had no mental health impact, nor is it in keeping with what was observed during this same period in the United States or New Zealand in terms of suicide attempts and visits for substance use disorders.7,23 Indeed, most services for mental health and substance use disorders are provided in ambulatory and community settings; there may have been increased demand for ambulatory services, with a shift in the case mix toward conditions suited to outpatient care (e.g., anxiety) that we did not capture in our acute care–focused outcomes.22 Our finding of no increase in acute care use above the prepandemic baseline — different from other jurisdictions, which have observed increases during this period24 — could also have been because people chose to avoid using acute care services such as emergency departments and hospitals, perhaps out of fear, as has been observed for physical health conditions4,5,25–27 and for mental health conditions in children.10 If true, such avoidance of acute treatment could be another adverse consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The factors that contributed to the persistent reduction in rates of acute care use in younger populations are less clear. Adolescents have lost contact with many protective adults such as teachers, coaches and clinicians, who may notice early signs of distress and mental illness. There is a substantial school-related seasonality to acute service use for mental health and substance use disorders among youth; service use drops substantially in the summer months and during holidays when children are not in school. If teachers and other nonparental adults are critical to case ascertainment for mental health and substance use disorders among children and youth, the shift to virtual schooling, where students are no longer in classrooms and observed by teachers or peers, may partly explain the persistent reduction in rates of acute care use after the onset of the pandemic. Whether this reflects a short-term reduction in true demand or whether the school setting serves as a critical environment for the recognition of distress in this population is unknown.

Among those who had emergency department visits for intentional self-injury, our finding of reduced admission and, more importantly, intensive care unit admissions or deaths may suggest a change in admission threshold or that the lethality of intentional self-injury presentations was reduced following the onset of the pandemic. These findings are in contrast to a rise in suicide attempts among youth in the United States through the summer and fall of 2020, but similar to what has been observed in Western Australia.28,29 Despite widespread reports of an increased population-wide mental illness burden associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, 2 our findings showed no increase in acute care service use for mental health and substance use disorders after the onset of the pandemic, and, in the case of youth, a persistent reduction. It is possible, and perhaps even likely, the mental health effects of the pandemic may be slower to present or more chronic in nature.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. We measured trends only through the first year of the pandemic. It is difficult to project trends beyond the time frame of our study; further monitoring will be important. Our diagnostic categories were based on health administrative data and, as such, reflect diagnoses based on the routine delivery of care and hospital coding, and not on validated assessments. Thus, analyses were limited to broad diagnostic groupings. We did not report on ambulatory care use for mental health issues, where much of the purported pandemic-related need may have been met. With the rapid shift to virtual modes of mental health care delivery, it is possible that access to services improved, offsetting the demand for acute care.6,30

Conclusion

There has been justified concern about the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of populations. In our study, we found an abrupt drop in use of acute mental health services immediately following the onset of the pandemic in Ontario, followed by a return to prepandemic levels in adults and rates slightly below prepandemic levels among youth 14 to 24 years old. Our findings suggest that distress from the early phases of the pandemic has not translated into increased acute service use for mental health and substance use disorders in the short term. The need for ongoing monitoring of acute mental health services trends — and indeed all mental health services trends — is critical for health system planning and service delivery as the pandemic and its expected effects on population mental health continues.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests: Natasha Saunders reports receiving an editorial honorarium from Archives of Diseases in Childhood and an honorarium from the M.S.I. Foundation, outside the submitted work. Simone Vigod reports receiving royalties from Up To Date, outside the submitted work.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Natasha Saunders, Alene Toulany and Paul Kurdyak conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the results, drafted the initial manuscript and revised the manuscript. Bhumika Deb and Rachel Strauss, Simone Vigod, Astrid Guttmann and Maria Chiu interpreted the results and revised the manuscript. Anjie Huang, Kinwah Fung and Simon Chen had access to, analyzed, and verified the data, interpreted the results and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health (MOH). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOH is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of CIHI.

Data sharing: The data set from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. Data-sharing agreements prohibit ICES from making the data set publicly available, but access may be granted to those who meet prespecified criteria for confidential access, available at https://www.ices.on.ca/DAS. The full data set creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/4/E988/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:817–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cost KT, Crosbie J, Anagnostou E, et al. Mostly worse, occasionally better: impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021 Feb 26; doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01744-3. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mental health during COVID-19 outbreak: poll #5 of 13 in series. Ottawa: Health Canada; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams TC, MacRae C, Swann OV, et al. Indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on paediatric healthcare use and severe disease: a retrospective national cohort study. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106:911–7. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-321008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams R, Jenkins DA, Ashcroft DM, et al. Diagnosis of physical and mental health conditions in primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e543–50. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30201-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glazier RH, Green ME, Wu FC, et al. Shifts in office and virtual primary care during the early COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada. CMAJ. 2021;193:E200–10. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.202303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holland KM, Jones C, Vivolo-Kantor AM, et al. Trends in US emergency department visits for mental health, overdose, and violence outcomes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:372–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pelletier JH, Rakkar J, Au AK, et al. Trends in US pediatric hospital admissions in 2020 compared with the decade before the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2037227. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munich J, Dennett L, Swainson J, et al. Impact of pandemics/epidemics on emergency department utilization for mental health and substance use: a rapid review. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:615000. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.615000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finkelstein Y, Maguire B, Zemek R, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on patient volumes, acuity, and outcomes in pediatric emergency departments: a nationwide study. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37:427–34. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000002484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amartey AMC, Gatov EAG, Lebenbaum M, et al. The mental health of children and youth in Ontario: 2017 scorecard. Toronto: ICES; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fifth edition. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams J, Young W. Summary of studies on the quality of health care administrative databases in Canada. In: Goel V, Williams JI, Anderson GM, et al., editors. Patterns of health care in Ontario, the ICES practice atlas. Ottawa: Canadian Medical Association; 1996. pp. 399–45. [Google Scholar]

- 15.The mental health of children and youth in Ontario: a baseline scorecard. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kurdyak P, Gandhi S, Holder L, et al. Incidence of access to ambulatory mental health care prior to a psychiatric emergency department visit among adults in Ontario, 2010–2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e215902. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiu M, Guttmann A, Kurdyak P. Mental health and addictions system performance in Ontario: an updated scorecard, 2009–2017. Healthc Q. 2020;23:7–11. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2020.26340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurdyak P, Lin E, Green D, et al. Validation of a population-based algorithm to detect chronic psychotic illness. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60:362–8. doi: 10.1177/070674371506000805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doktorchik C, Patten S, Eastwood C, et al. Validation of a case definition for depression in administrative data against primary chart data as a reference standard. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19:9. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1990-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mental illness hospitalization. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2018. [accessed 2021 Feb 2]. Available: indicatorlibrary.cihi.ca/display/HSPIL/Mental+Illness+Hospitalization. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joinpoint Trend Analysis Software. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute; [accessed 2021 Feb 2]. Available https://surveillance.cancer.gov/joinpoint/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saunders NR, Fu L, Strauss R, et al. Uptake of virtual mental health care among children and adolescents through the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadian Association of Health Services and Policy Research Conference 2021; May 17–18, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joyce LR, Richardson SK, McCombie A, et al. Mental health presentations to Christchurch Hospital Emergency Department during COVID-19 lockdown. Emerg Med Australas. 2021;33:324–30. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.13667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpson SA, Loh RM, Cabrera M, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychiatric emergency service volume and hospital admissions. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2021 May 29; doi: 10.1016/j.jaclp.2021.05.005. S2667-2960(21)00096-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cordoba M, Anteby R, Zager Y, et al. The effect of the COVID-19 outbreak on trauma-related visits to a tertiary hospital emergency department. Isr Med Assoc J. 2021;23:82–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinman M, de Sousa JHB, Tustumi F, et al. The burden of the pandemic on the non-SARS-CoV-2 emergencies: a multicenter study. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;42:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.12.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stohr E, Aksoy A, Campbell M, et al. Hospital admissions during Covid-19 lock-down in Germany: differences in discretionary and unavoidable cardiovascular events. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0242653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yard E, Radhakrishnan L, Ballesteros MF, et al. Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12–25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, January 2019–May 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:888–94. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7024e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dragovic M, Pascu V, Hall T, et al. Emergency department mental health presentations before and during the COVID-19 outbreak in Western Australia. Australas Psychiatry. 2020;28:627–31. doi: 10.1177/1039856220960673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lau J, Knudsen J, Jackson H, et al. Staying connected in the COVID-19 pandemic: telehealth at the largest safety-net system in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood) 2020;39:1437–42. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.