Abstract

The outbreak of COVID-19 has led to the large-scale usage of chlorinated disinfectants in cities. Disinfectants and disinfection by-products (DBPs) enter rivers through urban drainage and surface runoff. We investigated the variations in residual chlorine, DBPs, and different aquatic organisms in the Hanjiang, Fuhe, and Qinglinghe Rivers in Wuhan during the COVID-19 pandemic. The sampling sites were from the wastewater treatment plant outlets to the downstream drinking water treatment plant intakes. Total residual chlorine and DBPs (dichloromethane and trichloromethane) detected in the river water ranged from 0 to 0.84 mg/L and 0 to 0.034 mg/L, respectively. The residual chlorine and DBPs showed a gradual reduction pattern related to water flow, and the concentration at intakes did not exceed the Chinese drinking water source quality standards. Phytoplankton and zooplankton densities were not significantly correlated with residual chlorine and DBPs. The fluctuations in phytoplankton resource use efficiency (RUE) and zooplankton RUE in the Fuhe River, with the highest residual chlorine, and the Qinglinghe River with the highest DBPs, were higher than those in the Hanjiang River. For benthic macroinvertebrates, the number of functional feeding groups in the Hanjiang River was higher than that in the Fuhe and Qinglinghe Rivers. The water and sediment bacterial communities in the Hanjiang River differed significantly from those in the Fuhe and Qingling Rivers. The denitrification function involved in N metabolism was stronger in the Fuhe and Qinglinghe Rivers. Structural equation modelling revealed that residual chlorine and DBPs impacted the diversity of benthos through direct and indirect effects on plankton. Although large-scale chlorine-containing disinfectants use occurred during the investigation, it did not harm the density of the detected aquatic organisms in water sources. With the regular use of chlorinated disinfectants for indoor and outdoor environments in response to the SARS-CoV-2 globally, it is still necessary to study the long-term and accumulated responses of water ecosystems exposed to chlorine-containing disinfectants.

Keywords: River ecosystem, Disinfection residue, Phytoplankton, Zooplankton, Benthic macroinvertebrates, Bacterial community

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

The outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was declared by the World Health Organization as a public health emergency of international concern and was recognised as a pandemic (https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019). Consequently, there has been an intensification in the need to manage urban drainage and the health of receiving water bodies (Kataki et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020a). The primary and secondary treatment of wastewater in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) can remove viruses to some extent, and disinfection is key to prevent infectious pathogens from entering the environment (Chen et al., 2021). Chlorine-containing disinfectants are commonly used for disinfection in WWTPs and drinking water treatment plants (DWTPs) because of their efficiency and cost-effectiveness (Collivignarelli et al., 2018; Srivastav et al., 2020). Since February 2020, the China Ministry of Ecology and Environment has issued guidelines for hospital wastewater disinfection. It was suggested to use liquid chlorine, chlorine dioxide, or bleach for disinfection at a concentration of 50 mg/L (as available chlorine). The contact time for disinfection should be no less than 1.5 h, with residual chlorine limits should be no less than 6.5 mg/L (as free chlorine) (http://www.mee.gov.cn/xxgk2018/xxgk/xxgk06/202002/t20200201_761163.html).

The concentrations of chlorine-containing disinfectants must be controlled within a reasonable range to achieve complete disinfection and minimise residual chlorine. A study in Italy reported that free residual chlorine ranging from 0.17 to 0.20 mg/L would balance the E. coli limit values and acute toxicity of Daphnia magna, Vibrio fischeri, and Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata (Collivignarelli et al., 2017). Scholars in China reported that residual chlorine (>0.5 mg/L) could maintain biological stability, as assessed by assimilable organic carbon and biodegradable organic carbon in the reclaimed water (Ren and Chen, 2021). Artificial neural network modelling and automated control have also been developed to improve disinfection quality and reduce chlorine disinfectant consumption (Khawaga et al., 2019; Kadoya et al., 2020). Increasing the disinfectant concentration will result in lower levels of viral RNA, but the level of disinfection by-product (DBP) residues is higher, which will lead to an ecological risk from the effluent water (Zhang et al., 2020b). Therefore, researchers have been looking for a balance between the disinfection effect and the toxicity of residual chlorine.

The effluent's biological and genetic toxicity is often reported to be higher after chlorine disinfection (Zhong et al., 2019; Le Roux et al., 2017). The disinfection of sewage is vital in controlling the spread of many diseases that are caused by microorganisms but it can also produce harmful levels of DBPs, which are closely related to human health disorders, such as anaemia, reproductive system defects, central nervous system problems, and carcinogenesis (Srivastav et al., 2020). The formation of DBPs is affected by the concentration and type of chlorine and precursor compounds (Luo et al., 2020; Yoon et al., 2020). In addition to natural organic matter, emerging pollutants, including pharmaceuticals, personal care products, endocrine disruptors, artificial sweeteners, insecticide by-products, and pesticides, are continuously introduced into the aquatic environment (Ao et al., 2021). These compounds can serve as DBP precursors, and their potential toxicity could be enhanced after chlorination (Zhang et al., 2019). The global use of chlorine disinfectants also increases microbial chlorine resistance, potentiating the exposure to difficult-to-treat resistant pathogens (Ekundayo et al., 2021).

Through water circulation and disinfection of tap water and food processing, residual chlorine and DBPs can cause human health problems through drinking water and food (Maheshwari et al., 2020; Simpson and Mitch, 2021). Upstream wastewater enters the drinking water source of downstream cities along the receiving river (Richardson and Plewa, 2020). Soluble microbial products discharged into surface water can affect the formation of DBPs in DWTPs (Zhang et al., 2020c).

The impact of disinfectants and DBPs on aquatic organisms and water ecosystems via water transmission from WWTPs to the water sources of DWTPs has been has been of concern to researchers since large-scale disinfection in China, especially in Wuhan City, during the spread of COVID-19 (Zhang et al., 2020a). However, we currently know very little about this. Therefore, we surveyed the Hanjiang, Fuhe, and Qinglinghe Rivers in Wuhan City during the COVID-19 pandemic. The sample sites of each river were from WWTP where the sewage water originated from three COVID-19 designated hospitals, including Leishenshan Hospital, Huoshenshan Hospital, and Jinyintan Hospital outlets to the downstream DWTP intakes. The residual chlorine and typical DBPs and the community structure of phytoplankton, zooplankton, bacterioplankton, benthos, and sediment bacteria were analysed to evaluate the impact of WWTP discharge on aquatic ecosystems.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area and sampling

This study was conducted in Wuhan City (113°41′E to 115°05′ E and 29°58′ N to 31°22′ N), the largest city in central China, with an area of 8494 km2 and a population of approximately 12,000,000. Wuhan is in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River, where it and its largest branch, the Hanjiang River, converge across the city. The Shiyang, Sanjintan, and Huangjiahu WWTPs were chosen, with sewage treatment capacities of 100,000, 500,000, and 400,000 m3/d, respectively. The three WWPTs are responsible for treating the final effluent of Huoshenshan Hospital, Jinyintan Hospital, and Leishenshan Hospital, which are designated hospitals for the reception and treatment of COVID-19 patients. The receiving water bodies of the effluent of the three WWTPs are the Hanjiang River, the Fuhe River, and the Qinglinghe River. The corresponding DWTPs approximately 10 km downstream of the three rivers are the Baihezui, Dijiao, and Baishazou DWTPs.

Field sampling was conducted in May 2020 at 12 fixed sites along the river areas between each pair of WWTPs and DWTPs (Fig. 1 ). The sites along each river were designed approximately 100, 1000, 3000, and 10,000 m downstream of the outlet of each WWTP. Surface water and surface sediment samples were collected at each site to measure the conventional physical and chemical indicators, residual chlorine, and DBPs. Phytoplankton and zooplankton were collected using plankton nets, fixed with Lugol's iodine solution, and returned to the laboratory for qualitative and quantitative species analyses. Benthic macroinvertebrates were collected using a Peterson mud harvester, washed in situ with a 40-mesh screen, selected with tweezers, and stored in a 4% formalin solution for microscopic examination and weighing. Approximately 500 mL of each water sample was filtered using qualitative filter paper followed by Millipore 0.22-μm hydrophilic nylon membranes. The membrane discs and fresh sediment were separately placed in sterilised centrifuge tubes and stored at −80 °C until DNA extraction.

Fig. 1.

A map indicating the locations of the rivers and the sampling site locations.

2.2. Measurements of environmental factors

Water parameters including pH, dissolved oxygen (DO), oxidation-reduction potential (ORP), and electrical conductivity (EC) were determined online using a YSI-Pro Plus Multi-Parameter Water Quality Meter (YSI Incorporated, Yellow Springs, Ohio, USA). Turbidity was measured using an Aquafluor™ (TURNER DESIGNS, CA, USA). Concentrations of chemical oxygen demand (CODcr), total phosphorus (TP), total nitrogen (TN), ammonia (NH4 +-N), and nitrate (NO3 −-N) were determined as previously described (Bai et al., 2020). The sediment TN and TP were determined using the persulfate digestion method. The sediment organic matter (SOM) was determined as loss on ignition.

The chlorine concentration (including total residual chlorine and free chlorine) was measured using a Q-CL501B residual chlorine and total chlorine analyser (Shenzhen Sinsche Technology Co. Ltd., Shenzhen City, China). The measurement was based on the DPD (N,N-diethyl-1,4-phenylenediamine) colorimetric method. DBPs including trichloromethane (TCM), dichloromethane (DCM), and tribromethane (TBM) in water and sediment samples were detected by purge and trap/gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (Shimadzu GCMS-QP2020, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) as described by the Chinese standard HJ 639-2012 and HJ 605-2011. The detected limits of TCM, DCM and TBM in water samples were 0.0004 mg/L, 0.0005 mg/L and 0.0005 mg/L, and the corresponding limits in sediment samples were 0.0011 mg/kg, 0.0015 mg/kg and 0.0015 mg/kg.

2.3. Plankton resource use efficiency (RUE)

RUE could eliminate the difference in biomass caused by nutrient concentrations in different communities. Phytoplankton resource use efficiency (RUEpp) was calculated as phytoplankton biomass per unit TP, and zooplankton resource use efficiency (RUEzp) was calculated as zooplankton biomass per unit phytoplankton biomass (Filstrup et al., 2014).

2.4. DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and sequencing

Bacterial DNA in water and sediment was extracted with the OMEGA E.Z.N.A. TM Mag-bind soil DNA kit and the DNA integrity and concentrations were measured using agarose gel and the Qubit3.0 DNA Test Kit. The hypervariable bacterial regions V3–V4 of the 16S rDNA gene were PCR-amplified using 2 × Hieff® Robust PCR Master Mix. The reaction mix (30 μl) contained 10–20 ng of template DNA, 25 μl of 2 × Hieff® Robust PCR Master Mix (Yeasen Biotech Co. Ltd., Shanghai City, China), 1 μl of each primer. After PCR amplification, the DNA library was sequenced using Illumina bridge PCR with Primer F and Index-PCR Primer R. Subsequently, 250 bp paired-end sequencing was carried out on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform to generate the raw reads. The reads were spliced according to the overlapping relationship, and the sequence quality was qualified and filtered, followed by OTU cluster analysis and species classification analysis.

2.5. Statistical analyses

Spearman correlation analysis between environmental factors and between bacterial taxa and environmental factors was conducted using the PASW Statistics 18.0 software package. The analysis and plots of the Bray-Curtis algorithm, non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS), analysis of similarities (ANOSIM), linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe), and heatmap for water and sediment bacterial communities were conducted with the assistance of the R platform. To examine the direct and indirect effects of residual chlorine and DBPs on the diversity of aquatic communities, structural equation modelling (SEM) was performed using Amos 24.0 software. The maximum likelihood calculation was used to fit the covariance matrix to the model with Chi-square (P > 0.05), the root of the mean square error of approximation (RMSEA, < 0.05), and the comparative fit index (CFI, > 0.95). Figures were plotted using the OriginPro 9.0 and CANOCO 4.5 softwares.

3. Results

3.1. Residual chlorine and DBPs levels

Free chlorine, total residual chlorine, DCM and TCM have been detected in the water bodies of the three rivers, but there was no TBM detected in the water samples. No DBPs were detected in the sediment samples. The Qinglinghe River had the highest concentration of total residual chlorine and free chlorine, with average concentrations of 0.530 mg/L and 0.518 mg/L, respectively. The Fuhe River had the highest concentrations of DCM and TCM, with an average concentration of 0.0014 mg/L and 0.0012 mg/L, respectively. The concentrations of disinfectants and DBPs in the Hanjiang River were the lowest of the three rivers. Thus, the tailwater discharge from the WWTPs had a greater impact on the Qinglinghe and Fuhe Rivers (Fig. 2a–d).

Fig. 2.

The concentrations of disinfectants and DBPs in the receiving river water bodies along with the water flow. HJ, FH, and QLH represent the Hanjiang River, Fuhe River, and Qinglinghe River, respectively. a–d) The concentrations of total residual chlorine, free chlorine, dichloromethane, and trichloromethane in each river, e–h) the total residual chlorine, free chlorine, dichloromethane, and trichloromethane concentrations along with the water flow.

For the total residual chlorine and free chlorine concentrations, an overall downward trend was observed along the direction of the water flow. However, there was an increase 3 km downstream from the WWTP in the Fuhe River. Free chlorine increased from 0.06 mg/L to 0.26 mg/L, and total residual chlorine increased from 0.08 mg/L to 0.32 mg/L. The concentrations of free chlorine and total residual chlorine in the Qinglinghe River were significantly higher than those of the other two rivers, which may be caused by the lower flow of the Qinglinghe River and the larger discharge of tailwater. DCM and TCM decreased from the WWTP to 3 km downstream along the Fuhe River. However, increases in the two DBPs were found near the Dijiao DWTP (Fig. 2e–h).

3.2. Relationship between disinfectant residue (and DBPs) and water (and sediment) environmental indicators

Indicators of pH, DO, ORP, conductivity, turbidity, CODcr, TP, TN, NH4 +-N, and NO3 −-N concentrations in the water are shown in Fig. S1. Among the three rivers, the average turbidity and CODcr were higher in the Qinglinghe River, and the average concentrations of TP, TN, NH4 +-N, and NO3 −-N were higher in the Fuhe River. Nutrient indicators in each river showed a gradual reduction along with the water flow. The pH near the WWTP was relatively low and increased with distance downstream, for all three rivers. The dissolved oxygen 1–3 km downstream of the WWTP in the Fuhe River decreased from 6.76 mg/L to 3.58 mg/L, and there is a certain increase of ORP, electrical conductivity, TP, TN, NH4 +-N, and NO3 −-N in this river section.

The average concentrations of organic matter (OM), TP, and TN in the sediment of the Qinglinghe River were 2.94, 2.80, and 2.33 times that of the Hanjijang River. The corresponding values in the Fuhe River were 3.64, 1.54, and 2.12 times that of the Hanjiang River. The physical and chemical sediment indexes showed greater volatility in the Qinglinghe and Fuhe Rivers than in the Hanjiang River along the water flow (Fig. S2). The concentrations of OM, TN, and TP at 1 km and 3 km downstream of the WWTPs in the Qinglinghe and Fuhe Rivers were higher than those at the other sites.

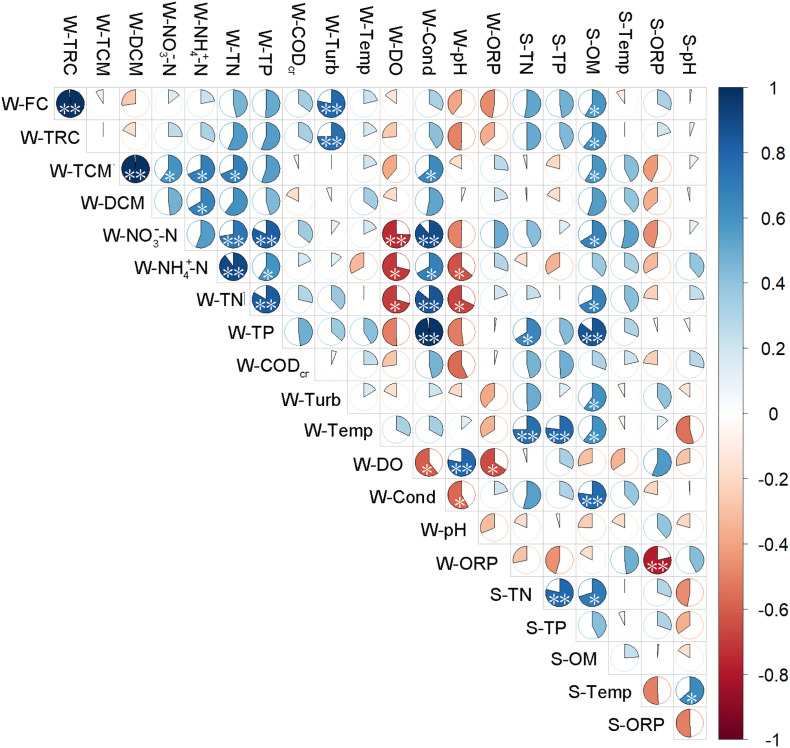

The Pearson correlation between the disinfectant and DBPs in water and the physicochemical indicators of water and sediment are shown in Fig. 3 . Free chlorine was positively correlated with total residual chlorine (P < 0.01), and both were positively correlated with water turbidity and sediment OM. TCM was positively correlated with DCM (P < 0.01), water NH4 +-N (P < 0.05), water NO3 −-N (P < 0.05), water TN (P < 0.05), conductivity (P < 0.05), and sediment OM (P < 0.05). DCM was positively correlated with water NH4 +-N (P < 0.05). Correlation analysis showed that the concentrations of disinfectants and DBPs were often higher in areas with higher water nutrient levels.

Fig. 3.

The correlation between disinfectant and DBPs in water and the physical and chemical indicators of water and sediment. The first letter W and S represent the water sample and sediment sample. FC, TRC, TCM, DCM, represent free chlorine, total residual chlorine, trichloromethane and dichloromethane, respectively. Significant differences between each paired sample are shown by asterisks (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

3.3. Phytoplankton

A total of 135 species belonging to 83 genera from 8 phyla were identified. The relative abundance and biomass percentage of phytoplankton are shown in Fig. 4a and b. Cyanophyta was dominant in abundance, whereas Dinoflagellate were dominant in biomass. The total number of phytoplankton species in the Hanjiang, Fuhe, and Qinglinghe Rivers were 63, 89, and 101, respectively (Fig. 4c). The phytoplankton biomass in the Hanjiang, Fuhe, and Qinglinghe Rivers ranged from 0.01 to 0.04 mg/L, 0.45 to 3.15 mg/L, and 0.04 to 66.87 mg/L, respectively (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4.

Phytoplankton distribution at the phylum level. HJ, FH, and QLH represent the Hanjiang River, Fuhe River, and Qinglinghe River, respectively. The numbers 1–4 represent the sampling sites from WWTP to DWTP in sequence. a) The relative abundance of all identified species numbers. b) Biomass percentages of all identified species. c) Number of each phylum at different sampling sites. d) Biomass percentages of each phylum at the different sampling sites.

The algae cell density in the Hanjiang, Fuhe, and Qinglinghe Rivers ranged from 1.62 × 104 to 2.08 × 105 cells/L, 1.29 × 106 to 6.84 × 106 cells/L, and 9.54 × 104 to 4.17 × 107 cells/L, respectively (Fig. S3a). The Qinglinghe River had the highest phytoplankton biomass and algal cell density, followed by the Fuhe and Hanjiang Rivers. The algal cell density of the three rivers decreased gradually along the water flow, except for the two sites. The dominant phylum in the Hanjiang River changed from Cyanophyta to Bacillariophyta from Shiyang WWTP to Baihezui DWTP (Fig. S3b). Cyanophyta cell density decreased from 65.26% to 33.33%, and Bacillariophyta increased from 29.21% to 55.56%. The dominant species changed from Oscillatoria sp. and Pseudoanabaena sp. to Oscillatoria sp. and Navicula sp. The dominant phylum in the Fuhe River changed from Cyanophyta to Cryptophyta from Sanjintan WWTP to Dijiao DWTP (Fig. S3c). Cyanophyta cell density decreased from 45.19% to 10.02%, and Cryptophyta increased from 0.42% to 63.37%. The dominant species changed from Leptolyngbya sp. to Cryptomonas erosa. The dominant phylum in the Qinglinghe River changed from Cyanophyta to Bacillariophyta from Huangjiahu WWTP to Baishazhou DWTP (Fig. S3d). The percentage of Cyanophyta cell density decreased from 63.78% to 36.16%, and Bacillariophyta increased from 18.16% to 50.63%. The dominant species changed from Merismopedia sp. to Melosira granulata.

The Qingling River had the highest RUEpp, followed by the Fuhe and Hanjiang Rivers (Fig. 5a). Bacillariophyta mainly contributed to the RUE of the Hanjiang River, and the dominant contribution did not change along with water flow. The RUE of the Fuhe and Qinglinghe Rivers were dominant from the phylum Chlorophyta to Cryptophyta and from Dinophyta to Bacillariophyta along with water flow (Fig. 5b–d), indicating that the adjusted productivity of the phytoplankton community remained unchanged only in the Hanjiang River.

Fig. 5.

Resource use efficiency (RUE) of the phytoplankton community. HJ, FH, and QLH represent the Hanjiang River, Fuhe River, and Qinglinghe River, respectively. The numbers 1–4 represent the sampling sites from WWTP to DWTP in sequence. a) RUE of each phylum at different sampling sites; b–d) RUE contribution of each phylum for the Hanjiang, Fuhe, and Qinglinghe Rivers, respectively.

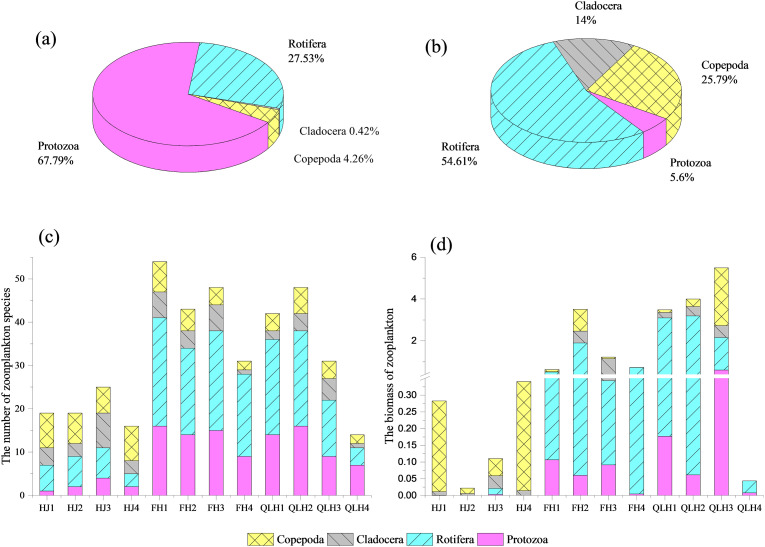

3.4. Zooplankton

A total of 96 species of zooplankton were identified, including 30 protozoa, 44 rotifers, 12 cladocera, and ten copepods. The relative abundance and biomass percentages of zooplankton are shown in Fig. 6a and b, respectively. Protozoa were dominant in abundance, while rotifers were dominant in biomass. The total zooplankton species in the Hanjiang, Fuhe, and Qinglinghe Rivers were 39, 81, and 67, respectively (Fig. 6c). The zooplankton biomass in the rivers of Hanjiang, Fuhe, and Qinglinghe ranged from 0.02 to 0.34 mg/L, 0.63 to 3.51 mg/L, and 0.04 to 5.49 mg/L, respectively (Fig. 6d).

Fig. 6.

The taxonomic composition of zooplankton. HJ, FH, and QLH represent the Hanjiang River, Fuhe River, and Qinglinghe River, respectively. The number 1–4 represent the sampling sites from WWTP to DWTP in sequence. a) Relative abundance of all the identified species numbers. b) Biomass percentages of all identified species. c) Number of taxa at different sampling sites. d) Biomass percentages of each phylum at different sampling sites.

The zooplankton density in the Hanjiang, Fuhe, and Qinglinghe Rivers ranged from 2.6 to 92.8 ind./L, 690.5 to 2976.04 ind./L, and 6018.2 to 14,206.5 ind./L, respectively (Fig. S4a). The Qinglinghe River had the highest zooplankton biomass and density, followed by the Fuhe and Hanjiang Rivers. The dominant taxon in the Hanjiang River was copepoda, except for HJ3, which is about 3 km downstream of the Shiyang WWTP (Fig. S4b). The dominant taxon in the Fuhe River changed from protozoa to rotifera from the Sanjintan WWTP to Dijiao DWTP samples (Fig. S4c). The percentage of protozoa density decreased from 85.44% to 13.03%, and that of rotifera increased from 13.24% to 86.89%. The dominant species changed from Leprotintinnus sp. to Polyarthra vulgaris. The dominant taxon in the Qinglinghe River changed from rotifera to protozoa from the Huangjiahu WWTP to the Baishazhou DWTP (Fig. S4d). The percentage of rotifera density decreased from 40.38% to 16.67%, and that of protozoa increased from 58.82% to 83.33%. The dominant species changed from Arcella sp. to Tintinnopsis wangi.

The Hanjiang River had the highest RUEzp, followed by the Fuhe and Qingling rivers (Fig. 7a). Copepoda mainly contributed to the RUEzp of the Hanjiang River, and the dominant contribution did not change with the water flow. The RUEzp of the Fuhe and Qingling Rivers is dominant from rotifera to cladocera and from rotifera to copepoda from the WWTP to 3 km downstream, respectively (Fig. 7b–d), indicating that the adjusted productivity of the zooplankton community remained unchanged only in the Hanjiang River. The RUEzp was 1–2 orders of magnitude higher than the RUEpp in the HJ River, indicating that the top-down effect of zooplankton was stronger in HJ.

Fig. 7.

Resource use efficiency (RUE) of the zooplankton community. HJ, FH, and QLH represent the Hanjiang River, Fuhe River, and Qinglinghe River, respectively. The numbers 1–4 represent the sampling sites from WWTP to DWTP in sequence. a) The RUE of each taxon at different sampling sites; b–d) the RUE contribution of each taxon for the Hanjiang, Fuhe, and Qinglinghe Rivers, respectively.

3.5. Benthic macroinvertebrates

The benthic macroinvertebrates identified belonged to the phyla Annelida, Mollusca, and Arthropoda. They accounted for 25%, 35%, and 40% of the total number, respectively (Fig. 8a). The Hanjiang, Qinglinghe, and Fuhe Rivers were dominated by annelids, arthropods, and molluscs, respectively.

Fig. 8.

The distribution of different groups of benthic macroinvertebrates in the three rivers. a) Number and percentage of each phylum. HJ, FH, and QLH represent the Hanjiang River, Fuhe River, and Qinglinghe River, respectively. b) Functional feeding groups. c) Zoobenthos density of different tolerance levels. d) Zoobenthos biomass of different tolerance levels.

According to the functional feeding groups in the three rivers, the identified zoobenthos were classified into scrapers, gatherer-collectors, filter-collectors, and predators (Fig. 8b). The Hanjiang, Qinglinghe, and Fuhe Rivers were dominated by filter-collectors, gatherer-collectors, and scrapers, respectively. The Hanjiang River had the most abundant functional feeding groups, and all four groups were detected. The density and biomass of zoobenthos in the Hanjiang River were 128 ind./m2 and 19.09 g/m2, respectively. Sensitive species were found only in the Hanjiang River. The density and biomass of zoobenthos in the Qinglinghe River were 80 ind./m2 and 0.2 g/m2, and only pollution-tolerant species were found there. The density and biomass of zoobenthos in the Fuhe River were 128 ind./m2 and 343.122 g/m2, respectively. Moreover, medium-tolerant species were found there.

The three rivers were all in polluted states when evaluated using the Shannon-Wiener diversity index. The Fuhe River was the most severely polluted when evaluated using the Pielou evenness index. The benthic pollution index showed that the rivers were in a moderately polluted state (Table S1).

3.6. Bacterial communities in water and sediment

A total of 2,062,281 high-quality 16S rDNA sequence reads were obtained from sediment and water samples using the Illumina HiSeq platform. After equalising the high-quality reads, the equalised reads were assigned to 6778 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% similarity. All the OTUs were clustered into 18 phyla or unclassified (relative abundance >0.1%), with 45.29% classified as Proteobacteria (Fig. S5), followed by Actinobacteria (16.32%), Bacteroidetes (8.87%), Chloroflexi (4.75%), and Verrucomicrobia (3.85%). Acinetobacter (5.38%) and Pseudomonas (3.01%) were the most abundant genera. The abundance of each phylum in Hanjiang River was unique among the three rivers, both in the sediment and water samples. Verrucomicrobia was more abundant, and Chloroflexi was less abundant in the Hanjiang River sediment than those in the Fuhe and Qinglinghe sediment (Fig. S5a). Proteobacteria were more abundant, and Bacteroidetes and Cyanobacteria were less abundant in the Hanjiang water than those in the Fuhe and Qinglinghe water (Fig. S5b).

The OTUs of sediment and water samples were clustered by the Bray-Curtis algorithm using a weighted calculation method, considering the presence or absence of species and the abundance of species. Hanjiang was a separate branch in both sediment and water samples, while Fuhe and Qinglinghe were interlaced (Fig. 9a). NMDS at both the genus and order levels showed that Hanjiang was a distinct group and the difference between river sediment was larger than that between the water samples (Fig. 9b–c). ANOSIM revealed a significant difference in the community structure between Hanjiang and Fuhe and between Hanjiang and Qinglinghe at the OTU level (Fig. 9d–e). When analysed at the genus, family, order, class, and phylum levels (Table S2).

Fig. 9.

The distance and similarity between different samples. The first letter of the sample name represents sediment (S) or water (W). HJ, FH, and QLH represent the Hanjiang River, Fuhe River, and Qinglinghe River, respectively. The numbers 1–4 represent the sampling sites from WWTP to DWTP in sequence. a) The Bray-Curtis algorithm at the OTU level. b) NMDS analysis at the genus level. c) NMDS analysis at the order level. d) ANOSIM (Analysis of similarities) boxplot of sediment samples at the OTU level. e) ANOSIM boxplot of water samples at the OTU level.

More biomarkers were found in the sediment samples than in the water samples, as revealed by Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) (Fig. S7a–b). Based on the LAD scores, the list of top biomarker taxa in the HJ sediment was class Alphaproteobacteria and phylum Verrucomicrobia (Fig. S7a). The relative abundances of class Alphaproteobacteria in Hanjiang were 2.60 and 2.08 times that in Fuhe and Qinglinghe. The relative abundances of phylum Verrucomicrobia in Hanjiang were 4.58 and 6.72 times higher than those in Fuhe and Qinglinghe. The biomarker taxa in the Hanjiang water were all from the phylum Proteobacteria, including the genus Pseudomonas in family Pseudomonadaceae and genus Aquabacterium in the family Burkholderiales_incertae_sedis (Fig. S7b). The relative abundances of genus Pseudomonas in Hanjiang were 8.30 and 36.11 times greater than Fuhe and Qinglinghe, respectively. The relative abundances of genus Aquabacterium in Hanjiang were 12.66 and 21.75 times higher than those in Fuhe and Qinglinghe.Key enzymes involved in nitrogen and sulphur metabolism showed more significant differences between the three rivers in the water than in the sediment samples (Fig. 10a–d). The nitrate reduction pathways from nitrite were stronger in Fuhe and Qinglinghe water than in Hanjiang water (Fig. 10a). The sulphate reduction was stronger in Hanjiang water, while the synthesis of sulphur-containing amino acids was stronger in Fuhe and Qinglinghe water (Fig. 10b). Assimilatory nitrate reduction in the sediment showed a tendency contrary to that in water (Fig. 10c).

Fig. 10.

Nitrogen and sulphur metabolism KEGG pathways in water and sediment. The nodes in the figure represent compounds, the boxes represent enzyme information. The column plots represent the abundance of the genes. The colour of the column shows a significant difference between groups, while grey fill is not significant. HJ, FH, and QLH are the Hanjiang, Fuhe, and Qinglinghe Rivers, respectively.

Spearman correlation analysis was performed between the bacterial taxa and environmental factors among the dominant phyla and genera. The taxa that were significantly correlated with at least one environmental factor are shown in the bubble map. The content of sediment organic matter (OM%) was significantly related to the largest number of taxa in the sediment samples, while TP was significantly related to the largest number of taxa in the water samples (Fig. 11a–b). Sediment OM% and water TP were the environmental factors with the highest degree of explanation for species information tested by RDA (Fig. S8).

Fig. 11.

Spearman correlation analysis between bacterial taxa and environmental factors. The colour and the size of each bubble represents the correlation coefficient. The analysis is made at the phylum and genus level separately. a) and b) are sediment samples and water samples.

3.7. Synthetic effects illustrated by SEM

Based on the SEM results, residual chlorine and DBPs affect sediment biota directly and indirectly (Fig. 12 ). The increase in residual chlorine (standardised path coefficient = 0.84; P < 0.001) and DBPs (standardised path coefficient = 0.76; P < 0.001) had extremely significant effects on the increase in the benthic pollution index. For indirect effects, bacterioplankton and zooplankton were involved in shaping sediment bacteria and benthic invertebrate assemblages. Bacterioplankton were significantly positively linked to sediment bacteria (standardised path coefficient = 0.52; P < 0.05). The diversity of bacterioplankton (standardised path coefficient = −0.37; P < 0.05) and zooplankton (standardised path coefficient = −0.34; P < 0.05) had significant negative effects on the benthic pollution index. However, residual chlorine had a positive effect on the zooplankton diversity (standardised path coefficient = 0.53; P < 0.05). Therefore, the indirect effects of residual chlorine on benthic invertebrates through zooplankton were weaker than the direct effects of these regulatory pathways.

Fig. 12.

Structural equation model (SEM) illustrating how residual chlorine and DBPs influenced the sediment biota directly and indirectly through planktonic organisms in the waterbody. The Shannon diversity index represented bacterioplankton, phytoplankton, zooplankton, and sediment bacteria, and the benthic pollution index represented the benthic invertebrates. The red and blue arrows indicate the negative and positive effects, respectively, and the dashed arrows represent non-significant effects (P > 0.05). The numbers on the arrows are the standardised coefficients, representing the strength of one factor's effect on another. The width of arrows is weighted according to standardised path coefficients. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

4.1. Chlorine disinfectants and DBPs in natural water bodies

Chlorine disinfectants such as Cl2, ClO2, and NaClO are widely used in drinking water and urban sewage treatment plants. During the spread of SARS-CoV-2, sodium hypochlorite 24 h continuous drip disinfection was used in 26 sewage treatment plants in Wuhan city, with a cumulative amount of 177.36 t for enhanced tailwater disinfection and 33.69 t for sludge disinfection (Sun et al., 2020). Direct runoff and indirect sewage effluents will eventually end up in lakes and rivers, threatening aquatic ecosystems (Zhang et al., 2020a). During the spread of SARS in 2003, excessive disinfection significantly affected the ecology of Taiwan's freshwater rivers (http://www.h2o-china.com/news/25339.html). Our study indicated an attenuation along the way from the sewage outlet to the inlet of DWTP, and a survey in Shanghai City (Chu et al., 2020) showed a similar trend. The concentrations of total residual chlorine near the DWTPs were lower than the threshold of 0.3 mg/L (the standard for drinking water quality in China). The concentration of total residual chlorine and free chlorine increased 3 km downstream of the outlet of the Sanjintan WWTP in the Fuhe River. A large amount of domestic garbage source pollution was found about 100 m away from this site during the survey, and the disinfection of garbage could be the possible reason for this increase. Dissolved organic matter (DOM) released by domestic sewage has a higher molecular weight, which serves as a precursor of DBPs (Prasert et al., 2021). Negative impact of residual chlorine may persist in the lower reaches of the receiving river through the formation of chloramines and other DBPs (Yamamoto et al., 1988; Li and Mitch, 2018). TCM and DCM increased 10 km downstream of the outlet of the Sanjintan WWTP, which indicated that DBPs might response at the lower reaches of the site where residual chlorine increase.

DBP formation depends on the quantity and quality of DOM, the sources of which include terrestrial foliar litter, atmospheric dry and wet deposition, algae, microplastics, etc. (Chen et al., 2020; He et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2020). Trihalomethanes (THMs) are a group of DBPs commonly detected in chlorinated waters, and their formation is influenced by temperature and pH. The summer season and higher pH conditions are beneficial to the formation and accumulation of THMs (Dominguez-Tello et al., 2015; Fooladvand et al., 2011). Although the NaClO concentration used in sewage treatment plants is positively correlated with the concentration of formed TCM and DCM (Nuershalati et al., 2020), the concentrations detected in the three rivers in this study were an order of magnitude lower than the limits specified by Chinese and American standards (China, 2006, USEPA, 2006), under the Technical Guidelines for the Operation and Management of Urban Drainage for the Prevention and Control of the SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan City. The dilution effect of the river water may correlated to the decrease of TCM and DCM. The concentrations of these two DBPs were the lowest in the Hanjiang River, which has the largest flow among the three rivers.

4.2. Potential secondary environmental and ecological risks caused by chlorine disinfectants

Due to the direct impact of chlorine disinfectants and the formation of DBPs, scholars called on the governments of China and other affected countries to conduct aquatic ecological integrity assessments during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Zhang et al., 2020a). Adverse effects on the early development of Cyprinus carpio and acute toxicity following chlorine exposure in black tiger shrimp and mussels have been reported (Verma et al., 2007; Lin and Husnah, 2002; Rajagopal et al., 2003). The abnormality and damage were possibly caused by altered protein metabolism, impairment of the gluconeogenic pathway, and subsequently the glycolytic pathway, and alteration of membrane transport and neurotransmission (Verma et al., 2007). A strong inhibitory effect on Chlorella sp. growth was observed at 0.20 mg/L of residual chlorine (Jin et al., 2014). In this study, although the residual chlorine concentration in the water samples was higher than 0.20 mg/L, the inhibition of total phytoplankton cell density, RUEpp, and diversity were not apparent. The 24-h LC 50 values of the total residual chlorine for glochidia were between 70 and 220 μg/L, 2.5 to 37 times higher than that for cladocerans (Valenti et al., 2010). However, positive correlations were found between free chlorine and Rotifera RUE (P = 0.001), Protozoa density (P = 0.003), Rotifera density (P = 0.028), and Cladocera density (P = 0.047). Rotifera provided food for benthic macroinvertebrates, which might have caused the indirect impact of residual chlorine on benthic macroinvertebrates. Ecosystems have a buffer and recovery capability against external pressure; therefore, acute toxicity and short-term inhibitory effects in natural water bodies do not appear when a single contaminant concentration reaches the critical value of the biological response under experimental conditions. However, long-term and accumulated effects are still worthy of attention.

Apart from the impact on aquatic organisms, a positive association between an increased risk of bladder cancer, colorectal cancer, poor pregnancy outcomes, with long-term exposure to chlorinated water has been shown (Jr et al., 2007; Bove et al., 2002). The discharge of chlorine-containing tailwater can lead to the loss of nitrifying microorganisms, destroying the ammonia nitrogen-nitrite-nitrate cycle system in river water, affect the natural water nitrogen cycle process, and cause harm to the aquatic environment and aquatic organisms (Chu et al., 2020). Through the metabolic transformation of diversified microorganisms and the transmission of the food chain, negative effects will be buffered through the self-stable regulatory mechanism of the ecosystem. Functional diversity is better than structural diversity in maintaining the stability of aquatic ecosystems. Structural diversity was not significantly affected, but functional diversity showed signs of decline. This requires further attention and further assessment to determine whether this decline is recoverable.

4.3. Impacts and suggestions for the overall river ecosystem

Potential risks caused by chlorine disinfectants and DBPs have increased with the increasing use of pharmaceutical and personal care products. Irbesartan, the medicine for treatment of high blood pressure, transformed into five completely new DBPs, the highest toxicity of which reached 12 times than that of irbesartan (Romanucci et al., 2020). DBP indicators are regulated and strictly limited in the regulatory guidelines of many countries and organisations (China, 2006; USEPA, 2006; Canada, 2019; World Health Organization, 2017). Total THMs are among the most important indicators governing the design and operation of many drinking water treatment plants and distribution systems (Kennedy et al., 2021). Therefore, their impact on aquatic ecosystems has received continued attention. For aquatic organisms, the direct impact of residual chlorine and DBPs on benthic organisms is far greater than their indirect transmission through aquatic organisms. Other indirect impacts are not included in the model, such as important consumer fish in the aquatic food chain.

Apart from evaluating ecological integrity in the receiving water, the protection of the drinking water sources and aquifers also needs to be considered. The protection and restoration of drinking water sources are key methods for DBP source control. Despite the residual chlorine was found higher than the standard for drinking water quality in China at some sites downstream the WWTPs, the ecosystems and drinking water sources were not significantly negatively impacted, which is inseparable from the setting of the ecological buffer zone around the drinking water sources. Therefore, continuous protection is an effective method for drinking water safety and an important guarantee for using an ecological buffer zone to strengthen the impact resistance of the water ecosystem and maintain a self-organised balance.

5. Conclusions

The variations in residual chlorine and DBPs and different types of aquatic organisms were studied from the three WWTPs to the downstream drinking water sources of DWTPs during the COVID-19 epidemic when large-scale chlorine-containing disinfectant was used. The residual chlorine and DBPs gradually decreased along the water flow, which met the quality standards of the drinking water sources. The community structure of phytoplankton, zooplankton, benthic macroinvertebrates, and bacteria in the water and sediment changed variously. The Hanjiang River has the largest volume among the three rivers. Therefore, due to the dilution effect, the concentrations of residual chlorine and DBPs were lowest in the Hanjiang water, and the fluctuation of various aquatic organisms was the lowest in the Hanjiang River. The diversity of benthic macroinvertebrates was influenced by the direct effects of residual chlorine and DBPs and the indirect effects of bacterioplankton and zooplankton. Although there was no significant inhibition of the density of phytoplankton and zooplankton, the long-term and accumulated effects on aquatic organisms are still worthy of further investigation.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Chuan Wang: Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Qianzheng Li: Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Fangjie Ge: Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Ze Hu: Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis. Peng He: Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis. Disong Chen: Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis. Dong Xu: Validation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Pei Wang: Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis. Yi Zhang: Validation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Liping Zhang: Validation. Zhenbin Wu: Validation, Methodology. Qiaohong Zhou: Validation, Methodology.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. XDA23040401), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51809257), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2018M630891; No. 2019T120705), and the Open Project Fund of Hubei Key Laboratory of Regional Development and Environmental Response (Hubei University) (No. 2020(C)001).

Editor: Sergi Sabater

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151711.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Ao X.W., Eloranta J., Huang C.H., Santoro D., Sun W.J., Lu Z.D., Li C. Peracetic acid-based advanced oxidation processes for decontamination and disinfection of water: a review. Water Res. 2021;188 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G.L., Zhang Y., Yan P., Yan W.H., Kong L.W., Wang L., Wang C., Liu Z.S., Liu B.Y., Ma J.M., Zuo J.C., Li J., Bao J., Xia S.B., Zhou Q.H., Xu D., He F., Wu Z.B. Spatial and seasonal variation of water parameters, sediment properties, and submerged macrophytes after ecological restoration in a long-term (6 year) study in Hangzhou west lake in China: submerged macrophyte distribution influenced by environmental variables. Water Res. 2020;186 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bove Frank, Shim Youn, Perri Zeitz. 2002. Drinking water contaminants and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canada H. Water and Air Quality Bureau, Healthy Environments and Consumer Safety Branch, Health Canada; Ottawa: 2019. Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality Summary Table. [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Hayward K., Khan S.J., Örmeci B., Pillay S., Rose J.B., Thanikal J.V., Zhang T. Role of wastewater treatment in COVID-19 control. 2021;56(90) [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Rucker A.M., Su Q., Blosser G.D., Liu X.J., Conner W.H., Chow A.T. Dynamics of dissolved organic matter and disinfection byproduct precursors along a low elevation gradient in woody wetlands - an implication of hydrologic impacts of climate change on source water quality. Water Res. 2020;181 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China . 2006. Standards for Drinking Water Quality. Beijing. [Google Scholar]

- Chu W.H., Shen J., Luan X.M., Xiao R., Xu Z.X. Water & Wastewater Engineering. 46(6) 2020. Study on secondary risk of water environment under enhanced disinfection of wastewater treatment plant during epidemic prevention and control; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Collivignarelli M.C., Abba A., Alloisio G., Gozio E., Benigna I. Disinfection in wastewater treatment plants: evaluation of effectiveness and acute toxicity effects. 2017;9(10):1704. [Google Scholar]

- Collivignarelli M.C., Abba A., Benigna I., Sorlini S., Torretta V. Overview of the main disinfection processes for wastewater and drinking water treatment plants. 2018;10(1):86. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Tello A., Arias-Borrego A., Garcia-Barrera T., Gomez-Ariza J.L. Seasonal and spatial evolution of trihalomethanes in a drinking water distribution system according to the treatment process. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015;187(11):1–19. doi: 10.1007/s10661-015-4885-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekundayo T.C., Igwaran A., Oluwafemi Y.D., Okoh A.I. Global bibliometric meta-analytic assessment of research trends on microbial chlorine resistance in drinking water/water treatment systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2021;278 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filstrup C.T., Hillebrand H., Heathcote A.J., Harpole W.S., Downing J.A. Cyanobacteria dominance influences resource use efficiency and community turnover in phytoplankton and zooplankton communities. Ecol. Lett. 2014;17(4):464–474. doi: 10.1111/ele.12246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fooladvand M., Ramavandi B., Zandi K., Ardestani M. Investigation of trihalomethanes formation potential in Karoon River water,Iran. 2011;178(1–4):63–71. doi: 10.1007/s10661-010-1672-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J.J., Wang F.F., Zhao T.T., Liu S.G., Chu W.H. Characterization of dissolved organic matter derived from atmospheric dry deposition and its DBP formation. Water Res. 2020;171 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.115368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S., Sun Y., Xu Z.L., Bi Y.M., Sun L.F. Effects of residual chlorine discharged in water on the growth of phytoplankton. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2014;34(19):5425–5433. [Google Scholar]

- Jr B.G., Rogerson P.A., Vena J.E. Case control study of the geographic variability of exposure to disinfectant byproducts and risk for rectal cancer. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2007;6(1):18. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-6-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadoya S.S., Nishimura O., Kato H., Sano D. Regularized regression analysis for the prediction of virus inactivation efficiency by chloramine disinfection. 2020;6(12):3341–3350. [Google Scholar]

- Kataki S., Chatterjee S., Vairale M.G., Sharma S., Dwivedi S.K. Concerns and strategies for wastewater treatment during COVID-19 pandemic to stop plausible transmission. 2021;164 doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy A., Flint L., Aligata A., Hoffman C., Arias-Paic M. Regulated disinfection byproduct formation over long residence times. Water Res. 2021;188 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khawaga R.I., Jabbar N.A., Al-Asheh S., Abouleish M. Model identification and control of chlorine residual for disinfection of wastewater. 2019;32 [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux J., Plewa M.J., Wagner E.D., Nihemaiti M., Dad A., Croue J.P. Chloramination of wastewater effluent: toxicity and formation of disinfection byproducts. J. Environ. Sci. 2017;58:135–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2017.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.K., Romera-Castillo C., Hong S., Hur J. Characteristics of microplastic polymer-derived dissolved organic matter and its potential as a disinfection byproduct precursor. Water Res. 2020;175 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.F., Mitch W.A. Drinking water disinfection byproducts (DBPs) and human health effects: multidisciplinary challenges and opportunities. 2018;52(4):1681–1689. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b05440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.K., Husnah Toxicity of chlorine to different sizes of black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon) in low-salinity shrimp pond water. 2002;33(14):1129–1135. [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y.C., Feng L., Liu Y.Z., Zhang L.Q. Disinfection by-products formation and acute toxicity variation of hospital wastewater under different disinfection processes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020;238 [Google Scholar]

- Maheshwari A., Abokifa A., Gudi R.D., Biswas P. Optimization of disinfectant dosage for simultaneous control of lead and disinfection-byproducts in water distribution networks. J. Environ. Manag. 2020;276 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuershalati N., Li C., Zhou K., Cao J.S. Study on disinfection by- products and treatment technology of tail water in urban sewage treatment plants. 2020;49(02):24–27. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . fourth edition. 2017. Guidelines for Drinking- Water Quality. incorporating the first addendum, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- Prasert T., Ishii Y., Kurisu F., Musikavong C., Phungsai P. Characterization of lower Phong river dissolved organic matters and formations of unknown chlorine dioxide and chlorine disinfection by-products by orbitrap mass spectrometry. Chemosphere. 2021;265 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopal S., Venugopalan V.P., Velde G.V.D., Jenner H.A. Tolerance of five species of tropical marine mussels to continuous chlorination. Mar. Environ. Res. 2003;55(4):277–291. doi: 10.1016/s0141-1136(02)00272-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X.L., Chen H.B. Effect of residual chlorine on the interaction between bacterial growth and assimilable organic carbon and biodegradable organic carbon in reclaimed water. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;752 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson S.D., Plewa M.J. To regulate or not to regulate? What to do with more toxic disinfection by-products? 2020;8 [Google Scholar]

- Romanucci V., Siciliano A., Guida M., Libralato G., Saviano L., Luongo G., Previtera L., Di Fabio G., Zarrelli A. Disinfection by-products and ecotoxic risk associated with hypochlorite treatment of irbesartan. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;712 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson A.M.A., Mitch W.A. 2021. Chlorine and ozone disinfection and disinfection byproducts in postharvest food processing facilities: a review. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastav A.L., Patel N., Chaudhary V.K. Disinfection by-products in drinking water: occurrence, toxicity and abatement. Environ. Pollut. 2020;267 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.Q., Huang X., Li G.H. Influence analysis and suggestion of disinfectants on the wastewater treatment plant and water environment during epidemic period. Technol. Water Treat. 2020;46(9):7–10. 41. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA . 2006. National Primary Drinking Water Regulations: Stage 2 Disinfectants and Disinfection By-products Rule. Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Valenti T.W., Cherry D.S., Currie R.J., Neves R.J., Jones J.W., Mair R., Kane C.M. Chlorine toxicity to early life stages of freshwater mussels (Bivalvia: Unionidae) Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010;25(9):2512–2518. doi: 10.1897/05-527r1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma A.K., Pal A.K., Manush S.M., Das T., Dalvi R.S., Chandrachoodan P.P., Ravi P.M., Apte S.K. Persistent sub-lethal chlorine exposure elicits the temperature induced stress responses in Cyprinus carpio early fingerlings. 2007;87(3):229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K., Fukushima M., Oda K. Disappearance rates of chloramines in river water. Water Res. 1988;22(1):79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H., Lim Y., Maeng S., Hong Y., Byun S., Kim H.C., Kim B., Kim S. Impact of DBPs on the fate of zebrafish; behavioral and lipid profile changes. 2020;11(6):391–398. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D.Y., Ling H.B., Huang X., Li J., Li W.W., Yi C., Zhang T., Jiang Y.Z., He Y.N., Deng S.Q., Zhang X., Wang X.Z., Liu Y., Li G.H., Qu J.H. Potential spreading risks and disinfection challenges of medical wastewater by the presence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viral RNA in septic tanks of Fangcang Hospital. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;741 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Tang W., Chen Y., Yin W. Disinfection threatens aquatic ecosystems. Science. 2020;368(6487):146–147. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S.S., Lin T., Chen H., Chen W., Xu H., Tao H. DNA pyrimidine bases in water: insights into relative reactivity, byproducts formation and combined toxicity during chlorination. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;717 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T.Q., He G.L., Dong F.L., Zhang Q.Z., Huang Y. Chlorination of enoxacin (ENO) in the drinking water distribution system: degradation, byproducts, and toxicity. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;676:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.04.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y., Gan W.H., Du Y., Huang H., Wu Q.Y., Xiang Y.Y., Shang C., Yang X. Disinfection byproducts and their toxicity in wastewater effluents treated by the mixing oxidant of ClO2/Cl2. Water Res. 2019;162:471–481. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material