Abstract

Clostridioides difficile (CD) is one of the top five urgent antibiotic resistance threats in USA. There is a worldwide increase in MDR of CD, with emergence of novel strains which are often more virulent and MDR. Antibiotic resistance in CD is constantly evolving with acquisition of novel resistance mechanisms, which can be transferred between different species of bacteria and among different CD strains present in the clinical setting, community, and environment. Therefore, understanding the antibiotic resistance mechanisms of CD is important to guide optimal antibiotic stewardship policies and to identify novel therapeutic targets to combat CD as well as other bacteria. Epidemiology of CD is driven by the evolution of antibiotic resistance. Prevalence of different CD strains and their characteristic resistomes show distinct global geographical patterns. Understanding epidemiologically driven and strain-specific characteristics of antibiotic resistance is important for effective epidemiological surveillance of antibiotic resistance and to curb the inter-strain and -species spread of the CD resistome. CD has developed resistance to antibiotics with diverse mechanisms such as drug alteration, modification of the antibiotic target site and extrusion of drugs via efflux pumps. In this review, we summarized the most recent advancements in the understanding of mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in CD and analysed the antibiotic resistance factors present in genomes of a few representative well known, epidemic and MDR CD strains found predominantly in different regions of the world.

Introduction

Antibiotics are no longer the ‘miracle cure’ they once were in saving lives from bacterial infections, with resistance being reported in all countries of the world.1 In what can unfortunately be called a ‘post-antibiotic era’ today,1 antibiotic resistance is one of the biggest threats to global health, food security and development.2 Since the beginning of use of antibiotics in humans and animals in the 20th century, a constant trend was seen globally that the release of each new antibiotic was followed a few years or decades later by the emergence of bacterial strains resistant to that antibiotic.1Clostridioides difficile (CD), the bacterium which causes the most common healthcare-associated infection in the USA, has been recognized by the CDC as one of the top five urgent antibiotic resistance threats in USA.1 Understanding the mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in CD is of paramount importance in designing therapeutic strategies to circumvent the resistance, guide clinical antibiotic therapy and develop novel effective antibiotics.

CD is a Gram-positive, spore-forming and toxin-producing anaerobic bacterium. CD infection (CDI) manifests as a wide range of clinical presentations, from mild diarrhoea to life-threatening pseudomembranous colitis, toxic megacolon, sepsis and death.3,4 In 2017, CDI caused 223 900 estimated hospitalizations, 12 800 deaths and $1 billion attributable healthcare costs.1,5 CDI is a leading cause of nosocomial antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and poses a grave threat especially to immunocompromised patients and older people, with a high incidence of recurrence even after successful treatment.4

The relationship between antibiotic use and CDI is complex. Use of antibiotics has been identified as the most significant risk factor for the development of CDI.4 On one hand, use of broad-spectrum antibiotics such as cephalosporins, clindamycin and fluoroquinolones disrupts the endogenous intestinal microbiota, which facilitates the colonization of the gastrointestinal tract by CD and establishment of CDI;3 on the other hand, antibiotics are the main therapeutic option available for CDI. Currently, only a few antibiotics are found to be effective in treating CDI. Vancomycin and fidaxomicin are recommended as first-line therapy to treat an initial episode of CDI and for recurrences.6 While no longer recommended as first-line therapy, metronidazole is used to treat non-severe CDI in adults and children.6 Since recently, rifamycins such as rifaximin are also being explored as adjunctive therapy against CDI.6 Unfortunately, resistance or decreased susceptibility to all these antibiotics have recently been reported,6–12 presenting a grave challenge to patients and clinicians with the lack of therapeutic options currently available to treat CDI.

Since the early 21st century, there has been an alarming increase in the incidence, severity and recurrence in cases of CDI globally, predominantly with the emergence of epidemic strains such as PCR ribotype (RT) 027 (BI/NAPI/027).13 These epidemic strains are also resistant to multiple antibiotics. Antibiotic resistance appears to drive outbreaks of CDI with high morbidity and mortality, as widespread usage of a particular antibiotic is often followed up by the emergence of resistant and epidemic strains. For example, a period of high usage of fluoroquinolones in North America was followed by the emergence and spread of fluoroquinolone-resistant RT027 strains, and this led to the global emergence of CDI in the early 2000s.14,15 Moreover, restricting the prescription of fluoroquinolones has been associated with a decrease in infections caused by fluoroquinolone-resistant CD isolates, and has been suggested to explain the decline of CDI in UK.16 While the epidemic ribotypes RT027 and RT078 are predominantly found in Europe and North America, the strain DH/NAP11/106 has now surpassed others as the most common cause of CDI in adults in USA.17 The epidemiology of CD shows distinct geographical distributions. RT017, which is suggested to have originated in Asia, is the most common ribotype found in this continent.18,19

CD has developed resistance to antibiotics with a wide variety of mechanisms such as alteration of the antibiotic, modification of the antibiotic target site and extrusion of the drugs via efflux pumps. Additionally, innate properties of CD such as biofilm and dormant spore formation improve its survival in environments containing antibiotics and increase its tolerance to antibiotics. Numerous genes and mutations of these genes encode mediators of these resistance mechanisms. CD has a highly mobile genome with a high number of mobile genetic elements such as conjugative and mobilizable transposons, prophages and IStrons.20 These mobile elements, especially transposons, contain several known and putative mediators of antibiotic resistance.20 Therefore, horizontal gene transfer may play an important role in dissemination of antibiotic resistance between CD and other species of bacteria, as well as among different CD strains. Hence, understanding the resistance mechanisms in CD is important for devising methods to overcome antibiotic resistance. Additionally, CD is known to have low genome conservation with high genome variability between different strains.21,22 Therefore, study of strain specific factors that drive antibiotic resistance is necessary to gain a comprehensive understanding of the resistance mechanisms of CD.

In this work, we have reviewed the most recent known information on the mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in CD (Table 1, Figures 1 and 2). We have also analysed the antibiotic resistance factors present in the genomes of a few representative epidemic CD strains found throughout the globe (Table 2).

Table 1.

Summary of mechanisms of antibiotic resistance of C. difficile

| Antibiotic | Mechanism of antimicrobial action | Proposed mechanism/s of resistance |

|---|---|---|

| Vancomycin | Inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis by binding to the d-Ala-d-Ala C-terminus of uracil diphosphate-N-acetylmuramyl-pentapeptide late peptidoglycan precursor23,24 | Alteration of vancomycin binding site in peptidoglycan precursors. Mediated by mutations in vanGCD operon enzymes: Ser313Phe and Thr349Ile in VanSCD and Thr115Ala in VanRCD7 (clinical isolates) |

| Metronidazole | Bacterial DNA breakage and cytotoxicity31 | Inhibiting reductive activation of metronidazole by impairing oxidoreductive metabolic pathways

|

| Fidaxomicin | Inhibits bacterial transcription by inhibiting bacterial RNA polymerase43 | Induced mutations in RNA polymerase subunit β: Gln1073Arg, Val1143Asp, Val1143Gly and Val1143Phe mediated by A3221G, T3428A, T3428G and G3427C of rpoB, respectively, and putative transcriptional regulator MarR: frameshift after amino acid 117 encoded by ΔT34928,44,109 (laboratory-generated mutants) |

| Rifamycins | Inhibits bacterial transcription by binding to the β subunit of RNA polymerase, RpoB12 | Potential impairment of drug binding by mutations in the RRDR of RpoB: Arg505Lys (commonest), His502Asn, His502Tyr, Ser488Tyr, Ser550Phe, Ser550Tyr, Asp492Tyr, Ser507Leu, Gln489Leu, Gly510Arg and Leu584Phe45 (clinical isolates) |

| Clindamycin/ MLSB family | Inhibits bacterial protein synthesis. Clindamycin inhibits peptide bond formation between the A- and P-site tRNAs during translation47 |

|

| Cephalosporins | Inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis by acylating the PBP transpeptidases in bacterial cell wall, thereby inhibiting the transpeptidase-mediated cross-linking reaction of peptidoglycan synthesis55 | |

| Fluoroquinolones | Inhibits bacterial DNA replication and transcription by inhibiting bacterial DNA gyrase, thus negative supercoiling58 |

|

| Tetracycline | Inhibits bacterial protein synthesis by binding to the 30S ribosomal subunit and blocking the association of aminoacyl-tRNA at the A-site58,67 | Prevention of binding of drug to the ribosome by production of ribosomal protectant proteins Tet(M), Tet(W) and Tet(44), usually located on mobile or conjugative elements, such as the conjugative elements of the Tn916 family (e.g. Tn6190) and Tn616468,69 (clinical strains) |

| Chloramphenicol | Inhibits bacterial protein synthesis by binding to the 50S ribosomal subunit at A2451 and A2452 residues and preventing the binding of tRNA to the P-site of the larger ribosomal subunit thus the elongation of polypeptide chain58 | Enzyme-mediated antibiotic modification and inactivation: relocation of an acetyl group from acetyl CoA to the primary hydroxyl group of chloramphenicol by catD-encoded chloramphenicol acetyltransferase enzyme, at the mobile regions Tn4453a and Tn4453b transposons71,72 (clinical isolates) |

| Linezolid | Inhibits bacterial protein synthesis by binding to bacterial 23S rRNA of the 50S subunit and preventing the formation of the 70S ribosomal unit73 | Target methylation and subsequent disruption of drug-target interaction: methylation of 8-methyladenosine at A2503 position in 23S rRNA of the large ribosomal subunit by cfr-encoded rRNA methyltransferase Cfr53 (clinical isolates) |

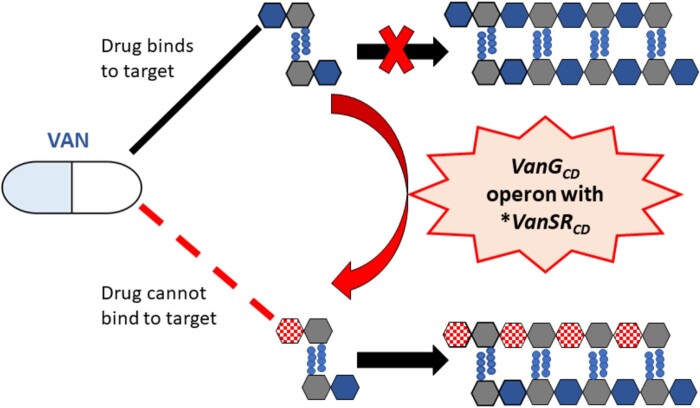

Figure 1.

Mechanisms of vancomycin resistance. Vancomycin (VAN) acts by binding with high affinity to the d-Ala-d-Ala C-terminus of uracil diphosphate-N-acetylmuramyl-pentapeptide and prevents the transglycosylation reaction which adds late precursors to the nascent peptidoglycan chain, thus inhibiting bacterial cell wall synthesis.23,24 Vancomycin resistance in C. difficile is associated with mutations in VanSCD sensor histidine kinase and VanRCD response regulator of the vanG operon-like gene cluster, vanGCD, which alter peptidoglycan precursors and thereby the vancomycin binding site7 (I. Wickramage and X. Sun, unpublished data). *, mutated. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

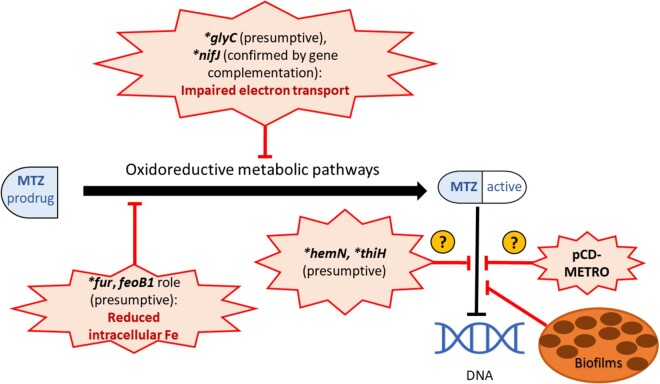

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of metronidazole resistance. Metronidazole (MTZ) acts by inducing DNA strand breakage and cytotoxicity, causing bacterial cell death.31 It is administered as an inactive prodrug that is activated under reductive conditions inside the cell.31C. difficile (CD) resistance to MTZ may be achieved by factors that prevent the generation of the active form of the drug, which are possibly mediated by multigenetic mechanisms involved in oxidoreductive and iron-dependent metabolic pathways.32–34 While the high copy number plasmid pCD-METRO is associated with CD MTZ resistance, its mechanism is unknown.11 CD growing in biofilms have shown increased tolerance to MTZ.40 *, mutated. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the print version of JAC.

Table 2.

Antibiotic resistance genes detected in some epidemic strains of C. difficile through genomic analysis via the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD)

| C. difficile strain and GenBank accession no. | RT | RGI criteria for gene search | ARO term; SNP | Detection criteria | AMR gene family | Drug class | Resistance mechanism | Identity of matching region (%) | Length of reference sequence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD630 (CP010905.2) | 012 | perfect | cdeA | protein homologue model | MATE transporter | fluoroquinolone, acridine dye | antibiotic efflux | 100.0 | 100.00 |

| strict | vanRG | protein homologue model | glycopeptide resistance gene cluster, vanR | glycopeptide | antibiotic target alteration | 77.87 | 99.15 | ||

| strict | vanXYG | protein homologue model | glycopeptide resistance gene cluster, vanXY | glycopeptide | antibiotic target alteration | 58.82 | 105.51 | ||

| strict | ermB (2 hits) | protein homologue model | Erm 23S ribosomal RNA methyltransferase | streptogramin, lincosamide, macrolide | antibiotic target alteration | 97.55 | 98.79 | ||

| R20291 (FN545816.1) | 027 | strict | cdeA | protein homologue model | MATE transporter | fluoroquinolone, acridine dye | antibiotic efflux | 99.09 | 100.00 |

| strict | vanRG | protein homologue model | glycopeptide resistance gene cluster, vanR | glycopeptide | antibiotic target alteration | 77.87 | 99.15 | ||

| strict | vanXYG | protein homologue model | glycopeptide resistance gene cluster, vanXY | glycopeptide | antibiotic target alteration | 58.82 | 105.51 | ||

| CD196 (NC_013315.1) | 027 | strict | vanRG | protein homologue model | glycopeptide resistance gene cluster, vanR | glycopeptide | antibiotic target alteration | 77.87 | 99.15 |

| strict | vanXYG | protein homologue model | glycopeptide resistance gene cluster, vanXY | glycopeptide | antibiotic target alteration | 58.82 | 105.51 | ||

| strict | Clostridioides difficile 23S rRNA with mutation conferring resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin; C656T | rRNA gene variant model | 23S rRNA with mutation conferring resistance to macrolide antibiotics | macrolide, lincosamide | antibiotic target alteration | 99.07 | 99.93 | ||

| M120 (NC_017174.1) | 078 | perfect | ant(6)-Ia 110 | protein homologue model | ANT(6) | aminoglycoside | antibiotic inactivation | 100.0 | 100.00 |

| perfect | ant(9)-Ia | protein homologue model | ANT(9) | aminoglycoside | antibiotic inactivation | 100.0 | 111.16 | ||

| perfect | ant(6)-Ib | protein homologue model | ANT(6) | aminoglycoside | antibiotic inactivation | 100.0 | 100.00 | ||

| strict | cdeA | protein homologue model | MATE transporter | fluoroquinolone, acridine dye | antibiotic efflux | 97.51 | 100.00 | ||

| strict | tet(W/N/W) | protein homologue model | tetracycline-resistant ribosomal protection protein | tetracycline | antibiotic target protection | 68.5 | 100.00 | ||

| strict | tet(W/N/W) | protein homologue model | tetracycline-resistant ribosomal protection protein | tetracycline | antibiotic target protection | 68.45 | 100.16 | ||

| DH/NAP11/106 (NZ_CP022524) | 106 | strict | vanRG | protein homologue model | glycopeptide resistance gene cluster, vanR | glycopeptide | antibiotic target alteration | 77.87 | 99.15 |

| strict | vanXYG | protein homologue model | glycopeptide resistance gene cluster, vanXY | glycopeptide | antibiotic target alteration | 58.82 | 105.51 | ||

| strict | Clostridioides difficile 23S rRNA with mutation conferring resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin; C656T | rRNA gene variant model | 23S rRNA with mutation conferring resistance to macrolide antibiotics | macrolide, lincosamide | antibiotic target alteration | 99.97 | 99.97 | ||

| CF5 (NC_017173) | 017 | strict | vanRG | protein homologue model | glycopeptide resistance gene cluster, vanR | glycopeptide | antibiotic target alteration | 77.87 | 99.15 |

| strict | vanXYG | protein homologue model | glycopeptide resistance gene cluster, vanXY | glycopeptide | antibiotic target alteration | 59.22 | 105.51 | ||

| strict | Clostridioides difficile 23S rRNA with mutation conferring resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin; C656T | rRNA gene variant model | 23S rRNA with mutation conferring resistance to macrolide antibiotics | macrolide, lincosamide | antibiotic target alteration | 99.03 | −99.93 | ||

| M68 (NC_017175.1) | 017 | perfect | tetM | protein homologue model | tetracycline-resistant ribosomal protection protein | tetracycline | antibiotic target protection | 100.0 | 100.00 |

| perfect | aac(6')-Ie-aph(2'')-Ia | protein homologue model | APH(2''), AAC(6') | aminoglycoside | antibiotic inactivation | 100.0 | 100.00 | ||

| perfect | catI | protein homologue model | CAT | phenicol | antibiotic inactivation | 100.0 | 100.00 | ||

| strict | ermB | protein homologue model | Erm 23S ribosomal RNA methyltransferase | macrolide, lincosamide, streptogramin | antibiotic target alteration | 98.78 | 98.79 | ||

| strict | Clostridioides difficile 23S rRNA with mutation conferring resistance to erythromycin and clindamycin; C656T | rRNA gene variant model | 23S rRNA with mutation conferring resistance to macrolide antibiotics | macrolide, lincosamide | antibiotic target alteration | 98.93 | 99.93 |

ARO; antibiotic resistance ontology, AMR; antimicrobial resistance; CAT, chloramphenicol acetyltransferase.

Antibiotics used for the treatment of CDI

Vancomycin

Vancomycin is now recommended as first-line therapy for initial, recurrent and fulminant CD infections.6 This glycopeptide antibiotic was released for usage in 1958 and has usually been reserved as a last resort drug for the treatment of severe infections caused by select organisms.6,23 While it was initially considered a wonder drug, which was immune to antimicrobial resistance, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus species were first reported in 1988, followed by Staphylococcus aureus in 2002.6,23 While vancomycin has been successful in treating CDI for many years, until recently being reserved for severe or recurrent cases, CD strains with resistance or reduced susceptibility to vancomycin have emerged in recent years, posing a grave concern.6–9

Vancomycin elicits its bactericidal activity by binding with high affinity to peptidoglycan precursors and inhibiting the bacterial cell wall synthesis. It forms a network of hydrogen bonds with the d-Ala-d-Ala C-terminus of uracil diphosphate-N-acetylmuramyl-pentapeptide and prevents the transglycosylation reaction which adds late precursors to the nascent peptidoglycan chain. It thereby inhibits the subsequent transpeptidation-based cross-linking, which is necessary for the formation of a mature peptidoglycan layer.23,24 Resistance to vancomycin has been reported to occur in enterococci through the presence of operons of enzymes known as Van operons.24 The enzymes encoded by these operons act by either synthesizing low-affinity peptidoglycan precursors where the d-Ala C-terminus has been replaced by d-Lac or d-Ser, or by cleaving the high affinity precursors thus eliminating the vancomycin binding site.24vanG is an inducible chromosomal operon that has been described to induce vancomycin resistance in enterococci and consists of two sets of genes called a sensor operon and a resistance operon that work together to produce the altered peptidoglycan precursor d-Ala-D-Ser. The sensor operon constitutes a two-component regulatory system with a membrane-bound sensor histidine kinase (VanS) and a response regulator (VanR) transcriptional activator, which in response to vancomycin stimulates the expression of downstream resistance genes. The resistance operon consists of VanT, a serine racemase that converts l-Ser to d-Ser; VanG, a d-Ala-D-Ser ligase; and VanY, a D, D-carboxypeptidase that removes d-Ala residues from the C-terminus of peptidoglycan precursors.24 A vanG operon-like gene cluster, named vanGCD, has been detected in about 85% of CD clinical isolates.25 However, the presence of this functional gene cluster was not shown to mediate vancomycin resistance in CD.26,27 But recently, mutations in genes of this cluster were found to be associated with vancomycin resistance in some novel CD strains reported in Israel7 and USA,7 (I. Wickramage and X. Sun, unpublished data) which had genomic sequences and antibiotic resistance patterns that have not been previously observed. Two RT027 clinical isolates from Texas that were resistant to vancomycin revealed a different mutation each in VanSCD, Ser313Phe and Thr349Ile.7 Other clinical isolates that showed resistance to vancomycin, also of RT027, from Texas (n = 7) and Israel (n = 2) showed the substitution Thr115Ala in VanRCD.7 Our study also detected this mutation, encoded by the SNP A343G in the receptor domain of vanRCD, in two novel RT027 CD strains isolated in Florida from CDI diagnosed patients (I. Wickramage and X. Sun, unpublished data). The vancomycin-resistant clinical isolates that carried these mutations in VanSCD and VanRCD showed constitutive expression of the VanG operon resistance genes,7 and the increased vancomycin MICs for these strains could be reversed by gene silencing of vanGCD.7 These mutated strains also showed reduced binding of vancomycin to the maturing cell wall. Through homology modelling-based analysis of the Thr115Ala substitution in VanRCD, it is proposed that the mutated position 115 of this protein, through interaction with a conserved flexible loop in the effector domain, stabilizes the dimeric, DNA-binding conformation of VanRCD, thereby enhancing its ability to transcriptionally activate the resistance genes of the operon. The change from polar threonine to non-polar alanine may energetically facilitate the hydrophobic interactions with lipophilic loop residues (Figure 1).7

Other mechanisms and mutations have also been suggested to explain vancomycin resistance in CD. Genetic changes were identified in a CD strain and clinical isolates serially passaged in vitro under increasing concentrations of vancomycin and were detected to have reduced susceptibility to this antibiotic after multiple passages.28 In the previously described CD strain thus passaged, a novel mutation Pro108Leu was detected in MurG N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase, which catalyses the conversion of peptidoglycan precursor lipid I to lipid II, an important step in bacterial cell wall synthesis. The same strain also revealed two other mutations—Glu327stop substitution in the putative RNA/single-stranded DNA exonuclease CD3659 and the deletion of a single amino acid in a stretch of alanines between positions 292 and 295 in the l-Ser deaminase encoded by the sdaB gene.28 One of the clinical isolates that developed low susceptibility to vancomycin after exposure to increasing drug concentrations displayed the G733T SNP in the rpoC gene, which encodes the Asp244Tyr substitution in the β′ subunit of RNA polymerase.28 This genetic change possibly mediates resistance by affecting multiple gene expression pathways.28 However, the causality of these mutations on vancomycin resistance in CD has not been verified by testing in naive hosts, and the MurG Pro108Leu substitution is also detected in the phenotypically vancomycin-susceptible CD630 reference strain.

CD may also use intrinsic barriers to survive in adverse environments containing antibiotics, such as formation of biofilms and spores. CD cells growing in vitro in biofilms have been shown to have higher percentages of survival under exposure to high concentrations of vancomycin than those grown planktonically.29 Also, biofilm formation was demonstrated to be induced in the presence of subinhibitory and inhibitory concentrations of vancomycin in vitro.29 Spores can survive antibiotic therapy and when treatment is completed or the antibiotic concentration in the body falls below an inhibitory threshold, they may germinate and cause a relapse of CDI. While vancomycin has successful bactericidal activity against vegetative forms of CD, it has no effect on spores.30 Therefore, sporulation has been found to play a role in the tolerance of some CD strains to vancomycin.

Metronidazole

Although for about 30 years metronidazole was recommended as first-line therapy for CDI, recent evidence has shown that it has inferior clinical benefits compared with vancomycin.6 Therefore, currently, metronidazole is reserved for use for an initial episode of non-severe CDI in settings where access to vancomycin or fidaxomicin is limited, and in paediatric patients.6 Low levels of resistance of CD to metronidazole have been reported in many countries.11

Metronidazole is a bactericidal nitroimidazole class of antibiotic, which is administered as a prodrug.31 Inside the cell, it is activated by the reduction of its nitro group in anaerobic enzymatic reactions with low redox potentials. This leads to generation of free radicals, leading to cytotoxicity and cell death in anerobic bacteria.31 The process of reductive activation itself may be cytotoxic, as metronidazole acts as an alternative electron acceptor and inhibits the proton motive force and ATP production.31

Metronidazole resistance in CD may involve multigenetic mechanisms that are possibly involved in oxidoreductive and iron-dependent metabolic pathways.32 Proteins that are involved in electron transfer reactions play important roles in the reduction of metronidazole to generate the active form of the drug.33 Genomic and proteomic analyses of the CD clinical isolate CD26A54_R, which maintained metronidazole resistance by serial passages under sublethal concentrations of metronidazole, identified mutations in genes involved in electron transport such as the glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase-encoding gene glyC (Ala229Thr) and the pyruvate-flavodoxin oxidoreductase (PFOR)-encoding gene nifJ (Gly423Glu).33,34 Another in vitro study supported the importance of PFOR in CD metronidazole resistance, where laboratory-generated mutations in the catalytic domains of PFOR gave rise to metronidazole resistance in CD that was reversed with gene complementation.32

Impairment of intracellular iron content has been implicated in CD resistance to metronidazole. In a laboratory-generated CD mutant, the truncation of feoB1 gene, which encodes a ferrous iron transporter, led to reduced intracellular iron content and a low level of resistance to metronidazole.32 The authors reasoned that a decrease in intracellular iron shifts cells toward flavodoxin-mediated oxidoreductase reactions, thus impairing the cellular action of metronidazole.32 Proteomic analysis of the metronidazole-resistant CD26A54_R isolate, generated as described above, showed a significant increase in expression the ferrous iron transport B (FeoB) protein in the absence of metronidazole, suggesting that metronidazole-resistant strains may be defective in iron uptake and/or regulation.33 In Helicobacter pylori, laboratory-generated mutations in the ferric uptake regulator Fur protein, a regulatory protein that controls the transcription of numerous genes in response to iron availability and oxidative stress, have been implicated in metronidazole resistance.35 Mutational disruption of the fur gene alters binding of Fur to superoxide dismutase and reduces cellular oxidative stress and subsequent metronidazole activation.34,35 Genomic analysis of the previously described serially passaged metronidazole-resistant CD26A54_R strain revealed a point mutation in the fur gene (Glu41Lys), which was absent in the metronidazole-susceptible variant of this strain CD26A54_S.34 However, the exact role of this mutation in metronidazole resistance in CD is not understood.

Several other presumptive mechanisms of CD resistance to metronidazole have been suggested based on in vitro studies. However, these proposed mechanisms have not been validated in naive hosts. Mutations found only in the resistant variant of the serially passaged CD strain CD26A54 (CD26A54_R)—such as the frameshift mutation Tyr214fs in the hemN gene encoding oxygen-independent coproporphyrinogen III oxidase, which produces a product involved in haem biosynthesis, and Ser328Phe in the thiH gene, which encodes a thiamine biosynthesis protein peptidase—have been proposed to contribute to nutrient limitation, which may lead to the aberrant growth seen in the culture of this strain.34 But the role of altered growth in CD metronidazole resistance is unclear.

CD has been observed to be heteroresistant to metronidazole, where the culture of a CD isolate consists of subpopulations with variable susceptibility to this antibiotic.36,37In vitro studies showed that subjecting initially metronidazole-resistant CD clinical isolates to a freeze-thaw cycle rendered them metronidazole susceptible,33,36 while maintaining slow growing subpopulations.36 Although in other anaerobic bacteria such as Bacteroides species heteroresistance has been associated with the presence of nim genes, which encode nitroimidazole reductases that render the drug inactive,38 the presence of nim genes has not been implicated in CD metronidazole resistance.36 Interestingly, induction of metronidazole resistance is seen with prolonged in vitro exposure to subinhibitory concentrations of this drug.33,36 However, the clinical significance of inducible heteroresistance of CD to metronidazole remains unclear.

Even though several plasmids of various sizes had been described in CD, until recently they were considered to not encode for any virulence or antibiotic resistance factors.39 Recently, a novel 7 kb high copy number plasmid, named pCD-METRO, was identified in strains belonging to diverse ribotypes in several countries, and was correlated to metronidazole resistance in CD.11 However, the exact gene(s) in this plasmid that confer the resistance are currently unknown (Figure 2). While the authors propose that this plasmid may have been acquired via horizontal gene transfer, they failed to identify a potential donor organism from the NCBI sequence data.11

Some virulence factors of CD such as formation of biofilms have been found to be associated with increased tolerance to metronidazole.40 CD cells growing in biofilms displayed survival under a 100-fold higher concentration of metronidazole than the cells growing in a liquid media culture.40 Moreover, exposure to subinhibitory concentrations of metronidazole was found to significantly increase the in vitro biofilm formation in some CD strains.41 The efflux pump CD2068 of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter class was also shown to reduce susceptibility of CD to metronidazole, together with other antibiotics.42

Fidaxomicin

Fidaxomicin was approved by the US FDA for the treatment of CDI in 2011 and is recommended for treating initial episodes and recurrences of CDI.6,43 Some studies suggest superior clinical benefits by fidaxomicin compared with vancomycin.6

Fidaxomicin is a macrolide antibiotic that elicits its bactericidal action by inhibiting bacterial RNA polymerase, and thereby transcription and subsequent protein synthesis.43 It has a narrow spectrum of activity with higher potency displayed for inhibiting RNA polymerase of clostridial species rather than other bacteria.43 Therefore, it poses a lower risk for disruption of the gut microflora, an important characteristic for a successful antibiotic that is used to treat CDI when taking the pathogenesis of CDI into consideration. It also achieves a high concentration in the intestine with minimal systemic absorption and a prolonged post-antibiotic effect.10,43 Resistance of CD to fidaxomicin is not widely known, although a single CD strain isolated from a patient experiencing a recurrence of CDI showed reduced susceptibility.10 Induced mutations in RNA polymerase subunit β—namely A3221G of rpoB leading to Gln1073Arg substitution of RpoB28 and genetically engineered mutations T3428A, T3428G and G3427C of rpoB resulting in Val1143Asp, Val1143Gly and Val1143Phe, respectively44—were found to be associated with CD resistance to fidaxomicin in two separate studies, and the latter three mutations were found in conjunction with reduced in vitro fitness and in vivo virulence.44 These alterations in the RNA polymerase likely impair its interaction with fidaxomicin. Moreover, a thymine deletion at the 349th position of marR, a gene encoding a homologue to the MDR-associated transcriptional regulator MarR, resulting in a frameshift of the resulting protein after amino acid 117, was found in a CD strain rendered fidaxomicin resistant via serial in vitro passages.28 The role of these alterations in clinical resistance to fidaxomicin in CD is yet to be verified.

Rifamycins

Rifamycins such as rifaximin and rifampicin are being tried as adjunct therapy for CDI.6 They inhibit bacterial RNA synthesis by binding to the β subunit of RNA polymerase, RpoB, at a site and step of RNA synthesis distinct from those of fidaxomicin.12,43 Although CD rifamycin resistance has been reported in several countries,12 there have been no reports of overlapping resistance between fidaxomicin and rifamycins.

Mutations in the rifamycin resistance-determining region (RRDR) of RpoB found in clinical isolates of CD have been found to be associated with rifamycin resistance,45 possibly leading to impairment of drug binding. The most common mutation Arg505Lys, as well as other mutations such as His502Asn, His502Tyr, Ser488Tyr, Ser550Phe, Ser550Tyr, Asp492Tyr, Ser507Leu, Gln489Leu, Gly510Arg and Leu584Phe, have been described in numerous strains resistant to rifamycins.45 However, most of these mutations did not impose fitness cost to the bacteria in vitro,45 suggesting that other unknown mechanisms may also contribute to rifamycin resistance in CD.

Antibiotics highly associated with pathogenesis of CDI

Clindamycin and other members of the macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLSB) family of antibiotics

Clindamycin is a lincosamide antibiotic with broad spectrum activity and belongs to the MLSB family of antibiotics.46 The drugs in this family act by disrupting bacterial protein synthesis, which is achieved with clindamycin by inhibiting peptide bond formation between the A- and P-site tRNAs during translation.47 Orally administered clindamycin is excreted in bile and gets highly concentrated in stools, disrupting the bacterial species diversity of the intestinal microbiota.46 Clindamycin administration is considered a highly important risk factor for the development of CDI.46

Erythromycin ribosomal methylase genes such as erm(B) are considered to mediate resistance of CD to antibiotics of the MLSB family such as clindamycin and erythromycin, despite the in vitro fitness cost.48,49 The protein encoded by this gene, ErmB, methylates the ribosome at a specific site of 23S rRNA and prevents the binding of the antibiotics.48 This gene is usually located on mobilizable genetic elements, such as Tn5398 or E4 elements related to the conjugative transposon Tn6194, thus is capable of interspecies horizontal transfer.48,49 Tn5398 has been reported to be transferred between CD strains and between CD and Bacillus subtilis by conjugation and homologous recombination.48,50–52 The CD reference strain CD630, which is a well-known erythromycin-resistant strain, contains two copies of erm(B) in its genome (Table 2). Other genes such as cfrB, cfrC and cfrE encoding a 23S rRNA methyltransferase have been implicated in resistance of CD to MLSB antibiotics.53 Efflux pumps may also play a role in CD resistance to the MLSB family of antibiotics. The expression of the CD cme gene, which encodes a secondary multidrug transporter of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS), was shown to confer erythromycin resistance in Enterococcus faecalis.54

Cephalosporins

Cephalosporins are bactericidal, β-lactam type antibiotics, which act by acylating the penicillin-binding protein (PBP) transpeptidases in bacterial cell wall, thereby inhibiting the transpeptidase-mediated cross-linking reaction of peptidoglycan synthesis, consequently resulting in the lysis of bacterial cells.55 They are also considered to contribute a very high risk for the development of CDI.56 While the mechanism of the widespread CD resistance to cephalosporins is not fully understood, some CD strains are known to encode β-lactamase enzymes, such as class D β-lactamases and putative β-lactamase encoded by genes such as CD630_04580, which destroy the β-lactam ring rendering the drugs inactive.20,56,57 Efflux pumps may also play a role in CD resistance to cephalosporins. The second-generation cephalosporin cefoxitin was found to be potentially extruded from CD cells via the ABC transporter CD2068, thus showing reduced susceptibility together with other antibiotics.42

Fluoroquinolones

Fluoroquinolones mediate their bactericidal action by inhibiting the bacterial DNA gyrase, topoisomerase II, thereby preventing the action of this enzyme of formation of a negative supercoil in the DNA, which is necessary for replication or transcription.58 Widespread use of fluoroquinolones and the subsequent development of fluoroquinolone resistance are associated with the emergence of epidemic RT027 strains.14,15

Resistance in CD was detected to be higher for the second-generation fluoroquinolone ciprofloxacin than for the fourth-generation fluoroquinolones moxifloxacin and gatifloxacin.59,60 Therefore, the newer generations of fluoroquinolones may provide a therapeutic alternative for treating CDI.59 Mutations in the quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDR) of gyrA and/or gyrB genes result in several amino acid substitutions, which render CD resistant to fluoroquinolones.59,61,62 The commonest of these mutations is the amino acid substitution Thr82Ile in GyrA.59–61 A recent study showed that the Thr82Ile substitution in GyrA resulted in no detectable fitness cost in CD.63 This suggests that even in the absence of antibiotic selective pressure this substitution can be maintained. The propensity of fluoroquinolone-susceptible CD strains to acquire mutations and develop reduced susceptibility was studied using five clinical parent strains of CD that were susceptible to moxifloxacin (MIC = 1 mg/L) and levofloxacin (MIC = 2 mg/L).60 CLSI’s tentative susceptibility breakpoint for moxifloxacin in anerobic organisms is given as ≤2 mg/L , 64 while the EUCAST epidemiological cut-off value for moxifloxacin in CD is 4 mg/L.65 These values have not been enumerated for levofloxacin. The fluoroquinolone-susceptible parent CD strains were grown under 2 mg/L of moxifloxacin or 4 mg/L of levofloxacin.60 Subsequently, colonies were selected, sequenced, their MICs determined, and were further passaged under double the concentration of moxifloxacin and levofloxacin compared with the MIC levels. Isolates thus selected in the presence of increasing concentrations of moxifloxacin and levofloxacin showed higher MICs for moxifloxacin (MIC = 8–128 mg/L) and levofloxacin (MIC = 8–32 mg/L) and also exhibited substitutions in GyrA and/or GyrB, which were previously not detected in the parent strains.60 This work suggests the potential of suboptimal concentrations of fluoroquinolones to select for GyrA and/or GyrB mutant fluoroquinolone-resistant CD isolates. While in vivo studies are needed to support these findings, this stresses the need for optimal dosing of antibiotics to prevent the development of antibiotic resistance.

Different types of efflux pumps have also been implicated in CD resistance to fluoroquinolones. The previously described ABC transporter CD2068 appeared to mediate MDR to ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin.42 Additionally, overexpression of the CD cdeA gene, which encodes the sodium-dependent efflux pump of the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) subfamily of secondary multidrug transporters, was observed to induce fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli.66

Other antibiotics

Tetracycline

Tetracyclines inhibit bacterial protein synthesis by binding to the 30S ribosomal subunit and blocking the association of aminoacyl-tRNA at the A-site.58,67 The tetracycline-resistant CD strains produce ribosomal protectant proteins such as Tet(M), Tet(W) and Tet(44), which prevent the binding of the antibiotics to the ribosome.68,69 The majority of these tetracycline resistance genes encoding ribosomal protectant proteins in CD are located on mobile or conjugative elements, such as tet(M)-containing conjugative elements of the Tn916 family (e.g. Tn6190) and tet(44)-containing Tn6164.68,69 Tetracycline resistance in CD is usually mediated by its most widespread gene class tet(M).69 To date, these resistance mechanisms have not been shown to mediate resistance in CD to newer tetracyclines such as tigecycline and omadacycline. The tigecycline-resistance genes tet(X3) and tet(X4) recently detected in Gram-negative bacteria and the acquired mutations in Tet proteins that reduce susceptibility to tigecycline have not been reported in CD.70

Chloramphenicol

Chloramphenicol elicits its bacteriostatic activity by binding to the 50S ribosomal subunit at A2451 and A2452 residues and inhibiting bacterial protein synthesis by preventing the binding of tRNA to the P-site of the larger ribosomal subunit, thus the elongation of polypeptide chain.58 CD resistance to chloramphenicol is achieved via enzyme-mediated antibiotic modification. CD has two copies of the catD gene, which encodes the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase enzyme, at the mobile regions Tn4453a and Tn4453b transposons.71 This enzyme relocates an acetyl group from acetyl CoA to the primary hydroxyl group of chloramphenicol, rendering the drug inactive and unable to bind to the ribosome to elicit its antibiotic action.72

Linezolid

Linezolid, a bacteriostatic oxazolidinone type of antibiotic recently introduced to the market, inhibits bacterial protein synthesis by binding to the 23S rRNA of the 50S ribosomal subunit, thus preventing the formation of the 70S ribosomal unit.73 Linezolid is currently not recommended for the treatment of CDI.6 However, a retrospective study over a period of 4 years on a cohort of patients who developed ventilator-associated pneumonia following major heart surgery suggested a potential protective role of linezolid against the development of CDI.74

Genes that encode the rRNA methyltransferase Cfr—cfrB, cfrC and cfrE—have been detected among clinical isolates of CD and these isolates exhibited higher MICs of linezolid.53 The Cfr protein catalyses the methylation of 8-methyladenosine at A2503 position in 23S rRNA of the large ribosomal subunit. This disrupts the interaction between the target and the antibiotic.53

Genomic analysis of antibiotic resistance in C. difficile: new insights into CDI evolution

The recent advancements in rapid and affordable WGS technologies and the availability of bioinformatics tools and online accessible databases have provided important information on current and emerging antibiotic resistance trends in CD and new insights on CDI dynamics of evolution.

The number of CD strains resistant to several classes of antibiotics is increasing worldwide. About 60% of clinical CD strains have been reported as MDR in Europe,75 representing one of the major threats to vulnerable patient populations, particularly in the intensive care units and the long-term care settings.

Besides the well-known RT027, several other CD RTs causing severe infections and outbreaks are reported as MDR, including RT012, RT017 and recent emerging types such as RT106, RT018, RT356 and RT078.18,76–81

Some CD types, such as RT017, display a higher prevalence of antibiotic resistance than other RTs. Genomic analysis of RT017 CD strains of recent isolation demonstrates that these strains have acquired new mechanisms of antibiotic resistance compared with the reference strain M68, isolated in 2003.22,82,83

Almost all (93%–100%) RT017 CD strains from China, Korea and Europe are resistant to MLSB antibiotics.84–87 In strain M68, this resistance has been associated with an erm(B) gene located on Tn6194, while a novel erm(G) gene, located on a mobile genetic element, capable of interspecies horizontal transfer, has recently been reported in RT017 CD strains.88 Interestingly, 8%–12% of recent RT017 strains have also developed high MIC values of imipenem, rarely observed in the CD population.85,89 In these strains, resistance to imipenem has been associated with two missense mutations (Ala555Thr and Tyr721Ser) near the active site of the pbp1 and pbp3 genes.90 Similarly, resistance to linezolid, very uncommon in CD (1%–6%),91,92 has been described in RT017 strains that have acquired mobile genetic elements carrying a cfr methyltransferase gene.93 Furthermore, more than 80% of RT017 strains have been reported resistant to fluroquinolones for alteration of the GyrB62,82,94 and a similar percentage have acquired a Tn916-like element, resulting in resistance to tetracycline.82,95 Finally, RT017 CD has been reported to have a higher prevalence of resistance (about 32%) to rifaximin than other RTs84,87 due to missense mutations in the rpoB gene.96 The high propensity of RT017 CD for acquiring antibiotic resistance and the high prevalence of MDR strains, particularly in Asia, where antibiotics are poorly regulated, raises several concerns about a further expansion of this ribotype not only in that region but also in other countries with a consequent increase of associated hospital outbreaks.

Surveillance data indicate that the incidence of CDI in the community (CA-CDI) has globally increased and now CA-CDIs accounts for 41% of all CDI cases in the USA,97 30% in Australia98 and 14% in Europe.99

Differently from the healthcare-associated RT027, diffusion of RT078, the most common cause of CA-CDI, is probably via other routes/sources outside the hospitals.100 CD reservoirs have been identified in animals (particularly farm animals), the natural environment (soil, water) and food (animal food and vegetables).101 Genomic analysis has demonstrated that CD RTs common to humans and farm animals share a recent evolutionary history and support CDI as a zoonotic disease with a consequent spillover of CD into the environment and food. In particular, genomic analysis has evidenced a potential bidirectional spread of RT078 CD strains between pigs and farmers.102 Tetracycline, widely used in animal husbandry, has a key role in driving RT078 CD diffusion. In fact, phylogenetic analysis performed on hundreds of international RT078 genomes has demonstrated a global spread of this RT, with multiple independent clonal expansions associated with the acquisition of tetracycline resistance.103 In particular, phenotypic and genotypic analysis of 185 RT078 strains has demonstrated that 48% of them contain one or more tetracycline resistance genes [tet(M), tet-40, tet(O) and tet-44], often associated with mobile genetic elements [Tn6190 for tet(M) and Tn6164 for tet-44].80 Among strains analysed, 36.1% were also resistant to MLSB but only 13% of them showed an erm(B) gene, prevalently associated with Tn6194; the remaining strains were negative for the other erm classes and for ribosomal proteins (L4/L22) and 23S rRNA gene mutations, suggesting the presence of an alternative mechanism. Among the other resistance loci identified, one or more aminoglycoside/streptothricin resistance genes were observed in 45% of the strains, while the aph3-III–sat4A–ant6-Ia cassette was reported in 40% of strains. Furthermore, all strains were positive for the β-lactamase-inducing PBP gene blaR and the efflux resistance gene cme.

Recent genomic investigations indicate that, besides toxigenic CD strains, non-toxigenic (NT) CD strains could also represent a source of antibiotic resistance determinants. Resistance and MDR have been reported in NT strains of human and animal origin and, in particular, several NT RT010 strains were found to be MDR and resistant to metronidazole.104,105 Interestingly, this resistance in RT010 has been correlated with the presence of the plasmid pCD-METRO.11 Furthermore, Tn6215-like elements have been reported in 33% of human and environmental RT010 strains.106 The Tn6215 is a peculiar mobilizable transposon, conferring resistance to MLSB and able to transfer between CD strains using different mechanisms (conjugation-like mechanism, phage ΦC2 transduction and a transformation-like mechanism).52,107 Since NT CD strains can colonize animals and humans and are widely diffused in the natural environment, they could have an important role in the spreading of antibiotic resistance among the CD population.

All data indicate that antibiotic resistance in CD is constantly evolving, with consequent important impacts on epidemiology of CDI. Recent studies strongly suggest that there is a potential circulation of CD strains between reservoirs where, depending on the selective forces present, antibiotic resistance determinants may be acquired, reinforcing the concept that CD resistome is shared between the environment and clinic. In alignment with the One Health surveillance framework of CDI, genomic analysis and the application of online tools for real-time detection and tracking of antibiotic resistance determinants may represent a useful weapon to expand monitoring across CD reservoirs, besides phenotypic surveillance, in order to guide the development of optimal antibiotic stewardship policies to prevent and limit mobilization of the genetic reservoir of resistance among the CD population.

Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in representative strains of the prevalent epidemic ribotypes

We identified the antibiotic resistance factors found in the genomes of a few selected representative CD RT strains, using the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD) Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI) software, with perfect or strict criteria for resistome prediction based on homology and SNP models108 to study CD strain-specific resistance factors (Table 2). Strains were selected based on their epidemic nature and to represent the most common ribotypes found in different areas of the world. While the presence of a resistance gene or a mutation itself is not indicative of phenotypic resistance, it is important to be aware of the potential resistance-mediating genes present in epidemiologically prevalent strains, to be vigilant for future emergence of resistance via occurrence of mutations or changes in gene expression. Moreover, predicting potential resistance patterns will be useful in guiding antibiotic stewardship policies and for identification of novel therapeutic targets to combat CDI.

Conclusions

Antibiotic resistance of CD is an urgent problem faced all over the world today. There is a global increase in MDR of CD, with emergence of novel strains that are often more virulent and MDR. Antibiotic resistance in CD is perpetually evolving with acquisition of novel resistance-determining mechanisms. These resistance-mediating factors can be transferred between different species of bacteria and among different strains of CD present in the clinical setting, community and in the environment, including animal reservoirs, food sources, soil and water. Community-acquired CDI is now increasing worldwide, and environmental sources of CD are considered to be important for this phenomenon, especially with zoonotic spillover and bidirectional transfer. Non-toxigenic CD strains are also now emerging as an important source of antibiotic resistance and MDR of CD, as these strains are widely diffused in the natural environment and can colonize both humans and animals, thus can vastly contribute to spreading CD antibiotic resistance.

Prevalence of different strains of CD and their characteristic antibiotic resistance patterns show distinct geographical patterns in different areas of the world. Epidemiological characteristics of CDI are largely determined by antibiotic resistance, driven by variable stringencies of regulation of antibiotic use in different regions of the world. Understanding epidemiologically driven and strain-specific characteristics of antibiotic resistance is important for effective surveillance of antibiotic resistance and for limiting spread of resistance-determining factors, not only between different strains of CD but also among various bacterial species.

Understanding the mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in CD and vigilant monitoring of CD for new genotypic and phenotypic characteristics and evolution of antibiotic resistance are also important for identifying potential therapeutic targets. Using targets thus identified, new and improved therapies need to be developed to prevent and curb antibiotic resistance of CD. Supplementing phenotypic methods of antibiotic resistance detection with genome analysis, bioinformatic tools and use of online databases is vital for efficient detection and monitoring of CD antibiotic resistance and evolution. Effective antibiotic stewardship, with prescription and usage of optimal doses of antibiotics for the optimal duration of time and avoiding unnecessary use of antibiotics, is essential to prevent and control the development of CD antibiotic resistance.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ann Mathew in our lab for providing useful references.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grant (R01-AI132711 and R01-AI149852).

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

References

- 1.CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019. US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2019.

- 2.WHO. Antibiotic Resistance. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antibiotic-resistance#:∼:text=Antibiotic%20resistance%20is%20one%20of,animals%20is%20accelerating%20the%20process.

- 3. Farooq PD, Urrunaga NH, Tang DM. et al. Pseudomembranous colitis. Dis Mon 2015; 61: 181–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC. Clostridioides difficile (C. diff). https://www.cdc.gov/cdiff/what-is.html.

- 5. Guh AY, Mu Y, Winston LG. et al. Trends in U.S. burden of Clostridioides difficile infection and outcomes. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1320–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S. et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66: e1–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shen WJ, Deshpande A, Hevener KE. et al. Constitutive expression of the cryptic vanGCd operon promotes vancomycin resistance in Clostridioides difficile clinical isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother 2020; 75: 859–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tickler IA, Goering RV, Whitmore JD. et al. Strain types and antimicrobial resistance patterns of Clostridium difficile isolates from the United States, 2011 to 2013. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 4214–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Snydman DR, McDermott LA, Jacobus NV. et al. U.S.-based national sentinel surveillance study for the epidemiology of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrheal isolates and their susceptibility to fidaxomicin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59: 6437–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goldstein EJ, Citron DM, Sears P. et al. Comparative susceptibilities to fidaxomicin (OPT-80) of isolates collected at baseline, recurrence, and failure from patients in two phase III trials of fidaxomicin against Clostridium difficile infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55: 5194–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boekhoud IM, Hornung BVH, Sevilla E. et al. Plasmid-mediated metronidazole resistance in Clostridioides difficile. Nat Commun 2020; 11: 598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O'Connor JR, Galang MA, Sambol SP. et al. Rifampin and rifaximin resistance in clinical isolates of Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008; 52: 2813–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. O'Connor JR, Johnson S, Gerding DN.. Clostridium difficile infection caused by the epidemic BI/NAP1/027 strain. Gastroenterology 2009; 136: 1913–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McDonald LC, Killgore GE, Thompson A. et al. An epidemic, toxin gene-variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 2433–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. He M, Miyajima F, Roberts P. et al. Emergence and global spread of epidemic healthcare-associated Clostridium difficile. Nat Genet 2013; 45: 109–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dingle KE, Didelot X, Quan TP. et al. Effects of control interventions on Clostridium difficile infection in England: an observational study. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17: 411–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kociolek LK, Gerding DN, Hecht DW. et al. Comparative genomics analysis of Clostridium difficile epidemic strain DH/NAP11/106. Microbes Infect 2018; 20: 245–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Imwattana K, Knight DR, Kullin B. et al. Clostridium difficile ribotype 017 - characterization, evolution and epidemiology of the dominant strain in Asia. Emerg Microbes Infect 2019; 8: 796–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Imwattana K, Putsathit P, DR K. et al. Molecular characterization of, and antimicrobial resistance in, Clostridioides difficile from Thailand, 2017-2018. Microb Drug Resist 2021; doi:10.1089/mdr.2020.0603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sebaihia M, Wren BW, Mullany P. et al. The multidrug-resistant human pathogen Clostridium difficile has a highly mobile, mosaic genome. Nat Genet 2006; 38: 779–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Scaria J, Ponnala L, Janvilisri T. et al. Analysis of ultra low genome conservation in Clostridium difficile. PLoS One 2010; 5: e15147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. He M, Sebaihia M, Lawley TD. et al. Evolutionary dynamics of Clostridium difficile over short and long time scales. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107: 7527–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stogios PJ, Savchenko A.. Molecular mechanisms of vancomycin resistance. Protein Sci 2020; 29: 654–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Courvalin P. Vancomycin resistance in gram-positive cocci. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42: S25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ammam F, Marvaud JC, Lambert T.. Distribution of the vanG-like gene cluster in Clostridium difficile clinical isolates. Can J Microbiol 2012; 58: 547–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ammam F, Meziane-Cherif D, Mengin-Lecreulx D. et al. The functional vanGCd cluster of Clostridium difficile does not confer vancomycin resistance. Mol Microbiol 2013; 89: 612–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Peltier J, Courtin P, El Meouche I. et al. Genomic and expression analysis of the vanG-like gene cluster of Clostridium difficile. Microbiology (Reading) 2013; 159: 1510–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leeds JA, Sachdeva M, Mullin S. et al. In vitro selection, via serial passage, of Clostridium difficile mutants with reduced susceptibility to fidaxomicin or vancomycin. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014; 69: 41–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dapa T, Leuzzi R, Ng YK. et al. Multiple factors modulate biofilm formation by the anaerobic pathogen Clostridium difficile. J Bacteriol 2013; 195: 545–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baines SD, O'Connor R, Saxton K. et al. Activity of vancomycin against epidemic Clostridium difficile strains in a human gut model. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009; 63: 520–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dingsdag SA, Hunter N.. Metronidazole: an update on metabolism, structure-cytotoxicity and resistance mechanisms. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018; 73: 265–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Deshpande A, Wu X, Huo W. et al. Chromosomal resistance to metronidazole in Clostridioides difficile can be mediated by epistasis between iron homeostasis and oxidoreductases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2020; 64: e00415–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chong PM, Lynch T, McCorrister S. et al. Proteomic analysis of a NAP1 Clostridium difficile clinical isolate resistant to metronidazole. PLoS One 2014; 9: e82622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lynch T, Chong P, Zhang J. et al. Characterization of a stable, metronidazole-resistant Clostridium difficile clinical isolate. PLoS One 2013; 8: e53757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Choi SS, Chivers PT, Berg DE.. Point mutations in Helicobacter pylori's fur regulatory gene that alter resistance to metronidazole, a prodrug activated by chemical reduction. PLoS One 2011; 6: e18236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pelaez T, Cercenado E, Alcala L. et al. Metronidazole resistance in Clostridium difficile is heterogeneous. J Clin Microbiol 2008; 46: 3028–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moura I, Spigaglia P, Barbanti F. et al. Analysis of metronidazole susceptibility in different Clostridium difficile PCR ribotypes. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68: 362–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gal M, Brazier JS.. Metronidazole resistance in Bacteroides spp. carrying nim genes and the selection of slow-growing metronidazole-resistant mutants. J Antimicrob Chemother 2004; 54: 109–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Amy J, Bulach D, Knight D. et al. Identification of large cryptic plasmids in Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile. Plasmid 2018; 96-97: 25–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Semenyuk EG, Laning ML, Foley J. et al. Spore formation and toxin production in Clostridium difficile biofilms. PLoS One 2014; 9: e87757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vuotto C, Moura I, Barbanti F. et al. Subinhibitory concentrations of metronidazole increase biofilm formation in Clostridium difficile strains. Pathog Dis 2016; 74: ftv114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ngernsombat C, Sreesai S, Harnvoravongchai P. et al. CD2068 potentially mediates multidrug efflux in Clostridium difficile. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 9982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mullane K. Fidaxomicin in Clostridium difficile infection: latest evidence and clinical guidance. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2014; 5: 69–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kuehne SA, Dempster AW, Collery MM. et al. Characterization of the impact of rpoB mutations on the in vitro and in vivo competitive fitness of Clostridium difficile and susceptibility to fidaxomicin. J Antimicrob Chemother 2018; 73: 973–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Dang UT, Zamora I, Hevener KE. et al. Rifamycin resistance in Clostridium difficile is generally associated with a low fitness burden. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60: 5604–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Buffie CG, Jarchum I, Equinda M. et al. Profound alterations of intestinal microbiota following a single dose of clindamycin results in sustained susceptibility to Clostridium difficile-induced colitis. Infect Immun 2012; 80: 62–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wilson DN. Ribosome-targeting antibiotics and mechanisms of bacterial resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol 2014; 12: 35–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Farrow KA, Lyras D, Rood JI.. Genomic analysis of the erythromycin resistance element Tn5398 from Clostridium difficile. Microbiology (Reading) 2001; 147: 2717–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wasels F, Spigaglia P, Barbanti F. et al. Clostridium difficile erm(B)-containing elements and the burden on the in vitro fitness. J Med Microbiol 2013; 62: 1461–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mullany P, Wilks M, Tabaqchali S.. Transfer of macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B (MLS) resistance in Clostridium difficile is linked to a gene homologous with toxin A and is mediated by a conjugative transposon, Tn5398. J Antimicrob Chemother 1995; 35: 305–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wust J, Hardegger U.. Transferable resistance to clindamycin, erythromycin, and tetracycline in Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1983; 23: 784–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wasels F, Spigaglia P, Barbanti F. et al. Integration of erm(B)-containing elements through large chromosome fragment exchange in Clostridium difficile. Mob Genet Elements 2015; 5: 12–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stojkovic V, Ulate MF, Hidalgo-Villeda F. et al. cfr(B), cfr(C), and a new cfr-like gene, cfr(E), in Clostridium difficile strains recovered across Latin America. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019; 64: e01074-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lebel S, Bouttier S, Lambert T.. The cme gene of Clostridium difficile confers multidrug resistance in Enterococcus faecalis. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2004; 238: 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pandey N, Cascella M.. Beta Lactam Antibiotics. StatPearls Publishing, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Toth M, Stewart NK, Smith C. et al. Intrinsic class D β-lactamases of Clostridium difficile. mBio 2018; 9: e01803-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sandhu BK, Edwards AN, Anderson SE. et al. Regulation and anaerobic function of the Clostridioides difficile β-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019; 64: e01496-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rang HD, Ritter JM, Flower RJ. et al. Rang and Dale’s Pharmacology. Elsevier Inc., 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dridi L, Tankovic J, Burghoffer B. et al. gyrA and gyrB mutations are implicated in cross-resistance to ciprofloxacin and moxifloxacin in Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2002; 46: 3418–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Spigaglia P, Barbanti F, Louie T. et al. Molecular analysis of the gyrA and gyrB quinolone resistance-determining regions of fluoroquinolone-resistant Clostridium difficile mutants selected in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53: 2463–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ackermann G, Tang YJ, Kueper R. et al. Resistance to moxifloxacin in toxigenic Clostridium difficile isolates is associated with mutations in gyrA. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001; 45: 2348–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Drudy D, Quinn T, O'Mahony R. et al. High-level resistance to moxifloxacin and gatifloxacin associated with a novel mutation in gyrB in toxin-A-negative, toxin-B-positive Clostridium difficile. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006; 58: 1264–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wasels F, Kuehne SA, Cartman ST. et al. Fluoroquinolone resistance does not impose a cost on the fitness of Clostridium difficile in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59: 1794–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.CLSI. Methods for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Anaerobic Bacteria; Approved Standard—Seventh Edition: M11-A7.2007.

- 65.EUCAST. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters, Version 9.0.2019.

- 66. Dridi L, Tankovic J, Petit JC.. CdeA of Clostridium difficile, a new multidrug efflux transporter of the MATE family. Microb Drug Resist 2004; 10: 191–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chopra I, Roberts M.. Tetracycline antibiotics: mode of action, applications, molecular biology, and epidemiology of bacterial resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2001; 65: 232–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Corver J, Bakker D, Brouwer MS. et al. Analysis of a Clostridium difficile PCR ribotype 078 100 kilobase island reveals the presence of a novel transposon, Tn6164. BMC Microbiol 2012; 12: 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Spigaglia P, Barbanti F, Mastrantonio P.. Tetracycline resistance gene tet(W) in the pathogenic bacterium Clostridium difficile. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008; 52: 770–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sholeh M, Krutova M, Forouzesh M. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile derived from humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2020; 9: 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lyras D, Storie C, Huggins AS. et al. Chloramphenicol resistance in Clostridium difficile is encoded on Tn4453 transposons that are closely related to Tn4451 from Clostridium perfringens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1998; 42: 1563–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Leslie AG, Moody PC, Shaw WV.. Structure of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase at 1.75-A resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1988; 85: 4133–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Papich MG. Saunders Handbook of Veterinary Drugs. Elsevier Inc., 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Valerio M, Pedromingo M, Munoz P. et al. Potential protective role of linezolid against Clostridium difficile infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2012; 39: 414–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Spigaglia P, Mastrantonio P, Barbanti F.. Antibiotic resistances of Clostridium difficile. Adv Exp Med Biol 2018; 1050: 137–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Freeman J, Vernon J, Pilling S. et al. Five-year Pan-European, longitudinal surveillance of Clostridium difficile ribotype prevalence and antimicrobial resistance: the extended ClosER study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2020; 39: 169–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ramirez-Vargas G, Quesada-Gomez C, Acuna-Amador L. et al. A Clostridium difficile lineage endemic to Costa Rican hospitals is multidrug resistant by acquisition of chromosomal mutations and novel mobile genetic elements. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61: e02054-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Barbanti F, Spigaglia P.. Characterization of Clostridium difficile PCR-ribotype 018: a problematic emerging type. Anaerobe 2016; 42: 123–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Seo MR, Kim J, Lee Y. et al. Prevalence, genetic relatedness and antibiotic resistance of hospital-acquired clostridium difficile PCR ribotype 018 strains. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2018; 51: 762–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Knight DR, Kullin B, Grace O, Androga GO. et al. Evolutionary and genomic insights into Clostridioides difficile sequence type 11: a diverse zoonotic and antimicrobial-resistant lineage of global One Health importance. mBio 2019; 10: e00446-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Roxas BAP, Roxas JL, Claus-Walker R. et al. Phylogenomic analysis of Clostridioides difficile ribotype 106 strains reveals novel genetic islands and emergent phenotypes. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 22135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Imwattana K, Knight DR, Kullin B. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Clostridium difficile ribotype 017. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2020; 18: 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Wu Y, Liu C, Li W-G. et al. Independent microevolution mediated by mobile genetic elements of individual Clostridium difficile isolates from clade 4 revealed by whole genome sequencing. mSystems 2019; 4: e00252-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Putsathit P, Maneerattanaporn M, Piewngam P. et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Clostridium difficile isolated in Thailand. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2017; 6: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lee JH, Lee Y, Lee K. et al. The changes of PCR ribotype and antimicrobial resistance of Clostridium difficile in a tertiary care hospital over 10 years. J Med Microbiol 2014; 63: 819–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Freeman J, Vernon J, Morris K. et al. Pan-European longitudinal surveillance of antibiotic resistance among prevalent Clostridium difficile ribotypes. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015; 21: 248 e9–248 e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Freeman J, Vernon J, Pilling S. et al. The ClosER study: results from a three-year pan-European longitudinal surveillance of antibiotic resistance among prevalent Clostridium difficile ribotypes, 2011-2014. Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24: 724–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Isidro J, Menezes J, Serrano M. et al. Genomic study of a Clostridium difficile multidrug resistant outbreak-related clone reveals novel determinants of resistance. Front Microbiol 2018; 9: 2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Gao Q, Wu S, Huang H. et al. Toxin profiles, PCR ribotypes and resistance patterns of Clostridium difficile: a multicentre study in China, 2012-2013. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2016; 48: 736–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Isidro J, Santos A, Nunes A. et al. Imipenem resistance in Clostridium difficile ribotype 017, Portugal. Emerg Infect Dis 2018; 24: 741–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Ackermann G, Adler D, Rodloff AC.. In vitro activity of linezolid against Clostridium difficile. J Antimicrob Chemother 2003; 51: 743–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Alcala L, Martin A, Marin M. et al. The undiagnosed cases of Clostridium difficile infection in a whole nation: where is the problem? Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18: E204–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Marin M, Martin A, Alcala L. et al. Clostridium difficile isolates with high linezolid MICs harbor the multiresistance gene cfr. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59: 586–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Drudy D, Harnedy N, Fanning S. et al. Emergence and control of fluoroquinolone-resistant, toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive Clostridium difficile. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007; 28: 932–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Dong D, Chen X, Jiang C. et al. Genetic analysis of Tn916-like elements conferring tetracycline resistance in clinical isolates of Clostridium difficile. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2014; 43: 73–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Cairns MD, Preston MD, Hall CL. et al. Comparative genome analysis and global phylogeny of the toxin variant Clostridium difficile PCR ribotype 017 reveals the evolution of two independent sublineages. J Clin Microbiol 2017; 55: 865–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Khanna S, Pardi DS, Aronson SL. et al. The epidemiology of community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Slimings C, Armstrong P, Beckingham WD. et al. Increasing incidence of Clostridium difficile infection, Australia, 2011-2012. Med J Aust 2014; 200: 272–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Bauer MP, Notermans DW, van Benthem BH. et al. Clostridium difficile infection in Europe: a hospital-based survey. Lancet 2011; 377: 63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Eyre DW, Davies KA, Davis G. et al. Two distinct patterns of Clostridium difficile diversity across Europe indicating contrasting routes of spread. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67: 1035–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Lim SC, Knight DR, Riley TV.. Clostridium difficile and one health. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020; 26: 857–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Knetsch CW, Kumar N, Forster SC. et al. Zoonotic transfer of Clostridium difficile harboring antimicrobial resistance between farm animals and humans. J Clin Microbiol 2018; 56: e01384-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Dingle KE, Didelot X, Quan TP. et al. A role for tetracycline selection in recent evolution of agriculture-associated Clostridium difficile PCR ribotype 078. mBio 2019; 10: e02790-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Barbanti F, Spigaglia P.. Microbiological characteristics of human and animal isolates of Clostridioides difficile in Italy: results of the Istituto Superiore di Sanita in the years 2006-2016. Anaerobe 2020; 61: 102136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Spigaglia P. Recent advances in the understanding of antibiotic resistance in Clostridium difficile infection. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2016; 3: 23–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Moradigaravand D, Gouliouris T, Ludden C. et al. Genomic survey of Clostridium difficile reservoirs in the East of England implicates environmental contamination of wastewater treatment plants by clinical lineages. Microb Genom 2018; 4: e000162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Goh S, Hussain H, Chang BJ. et al. Phage φC2 mediates transduction of Tn6215, encoding erythromycin resistance, between Clostridium difficile strains. mBio 2013; 4: e00840-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Alcock BP, Raphenya AR, Lau TTY. et al. CARD 2020: antibiotic resistome surveillance with the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res 2020; 48: D517–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Schwanbeck J, Riedel T, Laukien F. et al. Characterization of a clinical Clostridioides difficile isolate with markedly reduced fidaxomicin susceptibility and a V1143D mutation in rpoB. J Antimicrob Chemother 2019; 74: 6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Marsh JW, Pacey MP, Ezeonwuka C. et al. Clostridioides difficile: a potential source of NpmA in the clinical environment. J Antimicrob Chemother 2019; 74: 521–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]