Abstract

The inability to fully recover lost muscle mass following periods of disuse atrophy predisposes older adults to lost independence and poor quality of life. We have previously shown that mechanotherapy at a moderate load (4.5 N) enhances muscle mass recovery following atrophy in adult, but not older adult rats. We propose that elevated transverse stiffness in aged muscle inhibits the growth response to mechanotherapy and hypothesize that a higher load (7.6 N) will overcome this resistance to mechanical stimuli. F344/BN adult and older adult male rats underwent 14 days of hindlimb suspension, followed by 7 days of recovery with (RE + M) or without (RE) mechanotherapy at 7.6 N on gastrocnemius muscle. The 7.6 N load was determined by measuring transverse passive stiffness and linearly scaling up from 4.5 N. No differences in protein turnover or mean fiber cross-sectional area were observed between RE and RE + M for older adult rats or adult rats at 7.6 N. However, there was a higher number of small muscle fibers present in older adult, but not adult rats, which was explained by a 16-fold increase in the frequency of small fibers expressing embryonic myosin heavy chain. Elevated central nucleation, satellite cell abundance, and dystrophin−/laminin+ fibers were present in older adult rats only following 7.6 N, while 4.5 N did not induce damage at either age. We conclude that age is an important variable when considering load used during mechanotherapy and age-related transverse stiffness may predispose older adults to damage during the recovery period following disuse atrophy.

Keywords: Aging, Disuse atrophy, Extracellular matrix, Mechanotherapy, Skeletal muscle

With advancing age, adults lose muscle mass (1), which can be accelerated by periods of disuse atrophy (2). Importantly, aging impairs the ability to completely recover lost muscle mass following atrophy, which is observed in both human (3) and animal models (4). The absence of mechanical stimuli during disuse results in reduced anabolic and increased catabolic signaling which ultimately reduces muscle size (5). Resistance exercise is considered the gold standard of therapeutic approaches to increase net protein balance and muscle size in both adult and older adult populations (6); however, it may not be practical for older adults recovering from atrophy.

There are mechanical as well as metabolic components to resistance exercise, each independently having positive impacts on muscle growth (7). Studies both in vivo (8) and in vitro (9) have shown chronic passive loading to skeletal muscle increases protein synthesis and muscle size, while more recent studies have shown passive loading enacts mechanosensitive signaling pathways to increase anabolic signaling (10). Therefore, it is possible that the external application of mechanical stimuli to muscles recovering from atrophy may activate anabolic signaling and enhance the recovery of muscle mass in older adults.

Mechanical loading in the form of cyclic compressive loading (CCL), a massage mimetic and mechanotherapy, is an anabolic stimulus in adult rats (10-month-old) recovering from disuse atrophy (11). CCL serves as an additive mechanical stimulus to the reintroduction of normal ambulation to enhance the muscle regrowth process in adult rats (11). However, CCL had no effect on the enhancement of muscle mass in older adult rats (30-month-old), under the same experimental conditions (12). Previous studies have reported a resistance to anabolic stimuli in muscles from older adult animals (13–15), similar to what we observed in response to mechanotherapy during the recovery from atrophy. The inability to enhance anabolic signaling has been proposed to be due to a blunted activation of Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling (16), reduced ribosome biogenesis (17), reduced sensitivity to amino acids (18), reduced rates of protein synthesis (19), and/or insulin sensitivity (20). However, numerous groups have reported no apparent defects in anabolic pathways (13,21), and therefore, it remains controversial whether muscle from older adult rats can activate growth signaling following an anabolic stimulus. Alternatively, it could be argued that there may be differences in the threshold needed to activate anabolic signaling and growth between older and younger adult rats recovering from disuse atrophy. Indeed, adjusting the load of mechanotherapy to account for age-related differences in the response of muscle to stimuli may allow for enhancement of muscle mass recovery in older adult rats.

A potential explanation for the attenuated regrowth response to mechanotherapy in older adult rats (12) is that muscles exhibit increased stiffness with age (22) and therefore mechanosensing is blunted. It has been shown that stiffness retards cellular responsiveness in vascular smooth muscle cells (23), cardiomyocytes (24), fibroblasts (25), and importantly, muscle cells, as elevated axial stiffness (ie, stiffness in parallel to muscle fibers) in single muscle fibers isolated from older individuals negatively correlates to contractility (26). The influence of transverse stiffness (ie, stiffness perpendicular to muscle fibers) on the responsiveness of muscle to mechanical stimuli, such as during mechanotherapy, has not yet been investigated. Therefore, we proposed that a higher load during mechanotherapy would be required to elevate anabolic responses and overcome elevated transverse stiffness in aged muscle. In this study, we determined the difference in passive stiffness between adult and older adult rats in order to calculate the load needed for mechanotherapy, which we hypothesized would enhance regrowth in older adult rats recovering from disuse atrophy.

Method

Ethical Approval

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines provided by the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals: Eighth Edition and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Kentucky.

Animals and Study Design

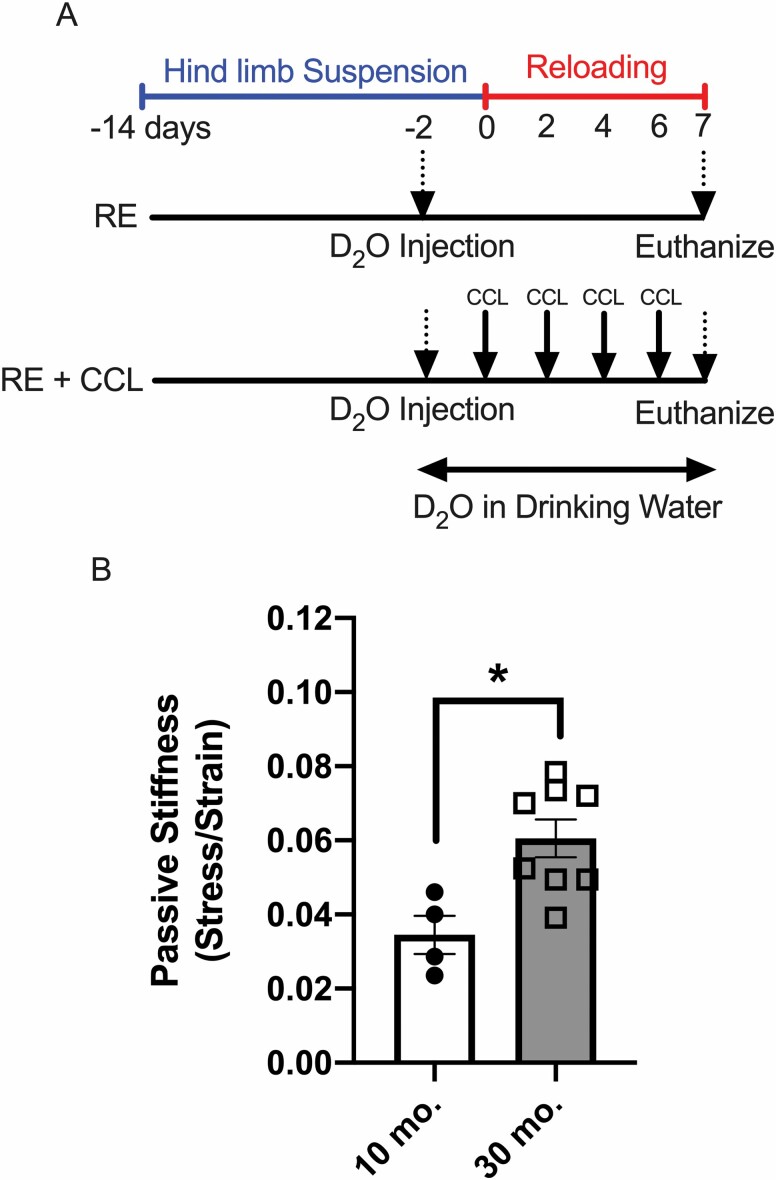

Adult (10 months) and older adult (30 months) male Fisher 344/Brown Norway rats were given access to food and water ad libitum throughout the study. Rats were kept on a 14:10 hour light/dark cycle in a temperature and humidity-controlled facility at the Division for Laboratory Animal Resources at the University of Kentucky. The study design is depicted in Figure 1A. Animal procedures used in this study have been previously described and provided in detail below (11,27,28). Adult and older adult rats were randomly assigned to either reload (RE; n = 6) after disuse atrophy without or with CCL intervention (RE + CCL; n = 6). Rats were housed 2 per cage during a 1-week acclimatization period after which they were transferred to custom-built single house cages for hind limb suspension to induce muscle atrophy. Following 14 days of hind limb suspension, rats were allowed to ambulate freely for a period of 7 days. Rats in the RE + CCL group received CCL intervention while those in the RE group were anesthetized at the same time. Deuterium oxide (D2O) was supplied to the rats in order to measure protein synthesis and breakdown during muscle regrowth, as described previously (11,27). A bolus of D2O (99%) was injected intraperitoneally (IP), equivalent to 5% of the body water pool, 2 days prior to the start of reloading. Following IP injection, rats were provided D2O-enriched drinking water (8%) for the remainder of the experimental time period. Rats were euthanized by IP injection (Somnasol, Euthanasia III Solution; 390 mg/mL) 24 hours after the last bout of CCL. Blood was collected through cardiac puncture and allowed to clot at room temperature for 30 minutes prior to centrifugation at 2000g for 10 minutes at 4°C. Serum was then aliquoted and stored at −80ºC until analysis. Gastrocnemius muscles were dissected, placed on cards at resting length, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80ºC for future experiments. Muscles from a previous group of animals that were single-housed normal weight bearing (WB), hind limb suspended (HS) for 14 days, and massaged at our previously reported lower load of CCL (RE + CCL 4.5 N) were used to determine whether a lower load of CCL induced any indices of damage (11, 12). Experiments performing a lower load of CCL (4.5 N) on rats recovering from disuse were not completed at the same time as the current study. However, all immunohistochemistry analyses of muscles from our previous study (11,12) and muscles obtained in our current study were performed at the same time.

Figure 1.

Experimental design (A). HS = hind limb suspension; RE = reloaded; RE + CCL (7.6 N) = reloaded with 7.6 N CCL; CCL = cyclic compressive loading; D2O = deuterium oxide. Passive stiffness (B) of adult (10 months) and older adult rat (30 months) gastrocnemius muscle. Values presented as mean ± SEM; n = 4–8 for all groups. *p < .05 denotes statistical significance.

Animal Procedures

Hind limb suspension

To induce disuse atrophy of hind limb muscles, rats were suspended by their tails for a period of 14 days as previously described (13,27). Briefly, rats were anesthetized via inhalation of 2% isoflurane and a suspension device was secured to the tail of each rat using gauze, cyanoacrylate glue, and casting tape. Rats were single housed in custom-made, high-walled cages and the ring of the tail device was connected to a steel rod suspended longitudinally across the cage. The rod was raised such that the rats could not touch their hind limbs to the floor of the cage while still being able to reach food and water freely. The steel rod was raised gradually for the first 24 hours to minimize stress to the rats.

Mechanotherapy of gastrocnemius muscle

The use of CCL on rats using a custom-built robotic device has been extensively described (11,12,27,29). CCL was administered every other day (total of 4 bouts) for 30 minutes each time to the right gastrocnemius muscle starting on the day of reloading (Figure 1A). Briefly, rats were anesthetized using isoflurane (5% for induction, 2% for maintenance per 500 mL oxygen) and placed left lateral recumbent on a heated pad. The right hind limb was secured using athletic tape surrounding the talocrural joint and the lateral aspect of the gastrocnemius muscle was given CCL application. The spring-loaded roller of the CCL device was designed to roll over the gastrocnemius muscle and record the normal force exerted by the muscle back on the roller and provide real-time recordings of applied loads. The load applied to the muscle was either 4.5 N or 7.6 N load and the frequency was set at 0.5 Hz. The 7.6 N load was determined by using the ratio (1.8) of passive stiffness between adult and older adult rat gastrocnemius muscle, and scaling our previously reported 4.5 N load accordingly. Rats not receiving CCL application were placed left lateral recumbent on a heated pad for a period of 30 minutes every other day to control for effects of anesthesia on muscle regrowth. Afterward, all rats were allowed to recover on a heated pad before being returned to their cages.

Passive Stiffness Measurements

In order to determine passive stiffness, a separate set of healthy WB male Fisher 344/Brown Norway rats (age 10 and 30 months) was used (n = 4–8). Briefly, rats were anesthetized using an induction chamber with 5% isoflurane and 1 L/minute oxygen and maintained via a nose cone at 2% isoflurane and 500 mL oxygen. Rats were then placed left lateral recumbent with the right hind limb secured to an aluminum platen of a device custom-fabricated for testing tissue mechanical properties in vivo. A cylindrical probe (10 mm diameter) in series with a multiaxis sensor was secured to the carriage of a servo-controlled worm drive and positioned normal to the lateral aspect of the right gastrocnemius muscle of the rat. The right gastrocnemius muscle was uniaxially compressed to a depth of 50% original tissue thickness at a rate of 83.3 μm/second using a 300-second ramp and hold test. Compressive force (F) and tissue displacement (x) were collected at 200 samples·per second. Sensor calibration was performed subsequent to data collection and confirmed the linearity of output voltage as a function of negative strain (R2 > 0.99). Data during the final 20 seconds of compressive ramp loading were extracted, converted to stress (F/A) and strain (ΔL/L), and fit with a linear trendline to determine the slope (stress/strain) and linear-range passive stiffness of the tissue (30).

Protein fractional synthesis rate

Determination of protein fractional synthesis rate was performed as previously described (12,27,31). Gastrocnemius muscles were homogenized in isolation buffer (1:10; 100 mM KCl, 40 mM Tris–HCl, 10 mM Tris Base, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM ATP, pH = 7.5) with phosphatase and protease inhibitors added (HALT, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Following homogenization, subcellular fractions were isolated using differential centrifugation (11). Protein pellets were then isolated and purified followed by incubation in 250 μL 1 M NaOH for 15 minutes at 50°C. Pellets were then hydrolyzed by incubation in 6 N HCl for 24 hours at 120°C. The pentafluorobenzyl-N,N-di(pentafluorobenzyl) derivative of alanine was then analyzed on an Agilent 7890A GC coupled to an Agilent 5975C MS (12,27,31). In order to determine total body water enrichment, a total of 125 μL of isolated serum was placed into an o-ring screw cap and inverted overnight at 80ºC. Samples were then combined with 2 μL of 10 M NaOH and 20 μL acetone along with 20 μL 0%–20% D2O standards before being capped and vortexed at low speeds overnight at room temperature. The following day, extraction was carried out using 200 μL hexane, the organic layer was transferred through anhydrous Na2SO4 into GC vials and analyzed using electron ionization mode (12,27,31).

Modeling calculations

Calculations used to determine protein synthesis rates have been previously described (11,12,27,31). Briefly, measurement of the newly synthesized fraction (f) of proteins was calculated using the enrichment of alanine-bound muscle proteins divided by precursor enrichment (p) using plasma D2O enrichment with mass isotopomer distribution analysis adjustment (32). In the event of significant change to protein mass, our previously published equations accounting for nonsteady-state conditions were used (11,12,27). Protein mass at time P(t) follows the equation:

in which Ksyn is the synthesis rate of protein mass over time, and kdeg is the degradation constant with units of inverse time using the following relationship:

Immunohistochemistry

Cross-sectional area and central nucleation

Mean fiber cross-sectional area (CSA) was determined as previously described (11,27). Muscle cross-sections (7 μm) in thickness were cut and left to dry at room temperature for 1 hour. Sections were then incubated with an anti-dystrophin antibody (1:200; Sigma, Oakville, ON) overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with an IgG2b 647-conjugated secondary antibody (1:250; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) for 1 hour. Sections were then incubated with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for approximately 10 minutes prior to cover-slipping and imaging using an upright fluorescent microscope (Axio Imager MI, Zeiss). A total of 5 regionally representative images of the medial and lateral heads of the gastrocnemius were taken with an average of 500 muscles fibers represented per muscle. Quantification of CSA was performed using MyoVision automated analysis software (33). The presence of central nuclei was determined by manually counting the total number of fibers containing centrally located nuclei per total number of fibers in the image and then averaged across 5 representative images; counting was performed by a blinded assessor.

Satellite cell abundance

Determination of satellite cell abundance was performed using protocols previously described (11). Muscle sections (7 μm) were left to dry at room temperature for 1 hour prior to fixation using 4% paraformaldehyde. Epitope retrieval was performed using sodium citrate (10 mM, pH 6.5) at 92°C. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 3% hydrogen peroxide in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by incubation with Normal Goat serum (TSA kit, T20935; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Anti-Pax7 primary antibody (1:100; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank [DHSB], Iowa City, IA) was diluted in PBS and incubated overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed and incubated with a goat anti-mouse biotinylated secondary antibody (1:1000; Invitrogen) for 1 hour, followed by incubation with streptavidin–HRP for 1 hour (1:500; Invitrogen) and TSA Alexafluor 594 (Alexa Fluor 594, #B40957; Thermo Fisher Scientific), to visualize Pax7+ satellite cells. Sections were washed and mounted using Vectashield Antifade mounting media with DAPI (Vector Laboratories) and imaged using an upright fluorescent microscope (Axio Imager MI, Zeiss). A total of 5 regionally representative images of the medial and lateral gastrocnemius heads were taken averaging approximately 500 muscle fibers per muscle. The number of Pax7+ satellite cells was determined by manually counting the number of Pax7+ and DAPI-positive and expressed relative to the total number of muscle fibers. Counting was performed by a blinded assessor.

Muscle morphology and eMyHC

Muscle sections (7 μm) were left to dry at room temperature for 1 hour prior to incubation with primary antibodies for eMyHC (1:5; DHSB), laminin (1:50; Sigma), and dystrophin (1:200; Sigma) overnight at 4°C. Sections were washed and incubated with a goat anti-mouse IgG2b 647-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen), a goat anti-mouse IgG1 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen), and a goat anti-rabbit 594-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for 1 hour prior to mounting to react with dystrophin, eMyHC, and laminin primary antibodies, respectively; sections were cover-slipped. Mosaics of the entire muscle cross-section were captured using an upright fluorescent microscope (Axio Imager MI, Zeiss) and analyzed, because eMyHC expression was regional and random sampling may have misrepresented counts of positive fibers. Due to the unique shape of fibers expressing eMyHC, automated quantification of CSA was not accurate; and therefore, the fibers were manually traced and counted relative to the total number of fibers in a muscle cross-section using Zen software (~6000–7000 fibers per section).

Statistical Analysis

Prior to statistical analyses, groups were analyzed for normality and equal variance and the data met the criteria for parametric tests. T-tests were used for comparisons of 2 groups, including analyses of passive stiffness, mean fiber CSA, and protein turnover. A one-way analysis of variance was used to determine differences between RE, RE + CCL (4.5 N), and RE + CCL (7.6 N) for eMyHC fiber size and frequency, satellite cell abundance, and central nucleation. Tukey’s post hoc test was used to determine differences between the groups when significance was detected. Statistical analysis of changes to the frequency distribution of muscle fiber size was made using a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. All statistical analyses and figures were prepared using GraphPad Prism 8 (San Diego, CA). All values are reported as mean ± SE with individual data points shown for each rat. Significance was assumed at p < .05.

Results

Passive Stiffness of Gastrocnemius Muscle Is Elevated With Age

Gastrocnemius muscles of older adult rats were significantly stiffer compared to gastrocnemius muscles of adult rats (Figure 1B). The 1.8-fold difference in passive stiffness observed in older rat gastrocnemius was used to ratiometrically scale the 4.5 N load used on adult rats to 7.6 N in the current study (11,12).

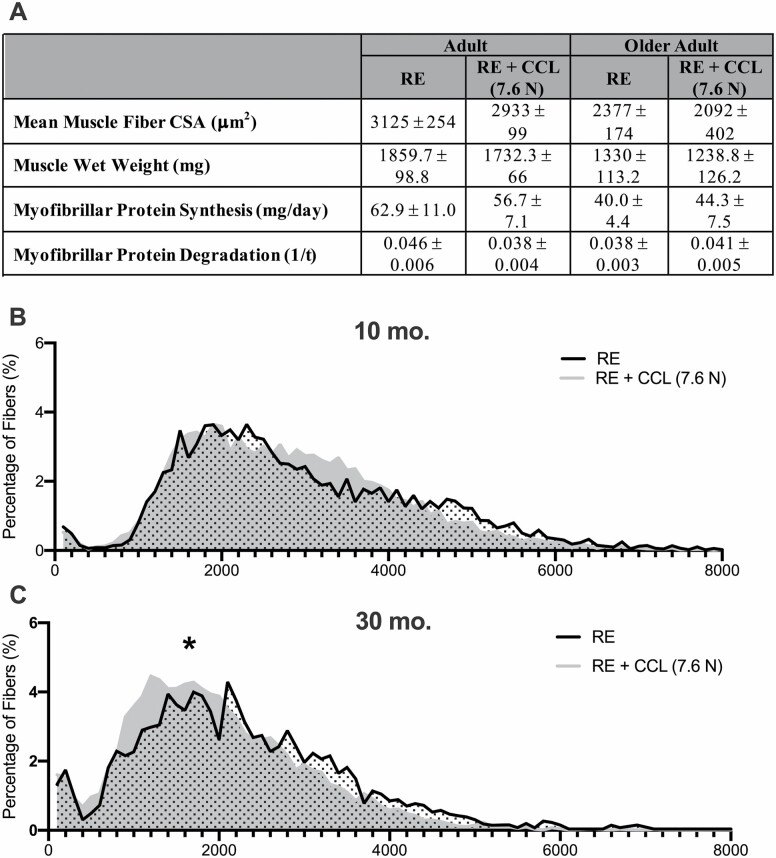

Higher CCL Does Not Induce an Anabolic Effect in Adult nor Older Adult Rats

Myofibrillar protein synthesis, myofibrillar protein degradation, muscle wet weight, and mean fiber CSA were not different between RE and RE + CCL (7.6 N) in 10- and 30-month-old rats following 7 days of regrowth (Figure 2A). The myofiber CSA distribution curve for 10-month-old rats was not different between RE and RE + CCL 7.6 N (Figure 2B), but was shifted to the left in 30-month-old rats (Figure 2C), indicating a larger number of smaller fibers in gastrocnemius muscle from older adult rats.

Figure 2.

CCL at 7.6 N is associated with a higher frequency of small fibers in older adult rats without any changes to protein turnover or mean fiber CSA. (A) Mean fiber CSA, muscle wet weights, protein synthesis, and protein degradation in 10- and 30-month-old rats recovering from atrophy with and without CCL at 7.6 N. Muscle fiber size distribution of (B) adult and (C) older adult rats. Values presented as mean ± SEM; n = 8. *p < .05 denotes statistical significance. RE = reloaded; CCL = cyclic compressive loading; CSA = cross-sectional area.

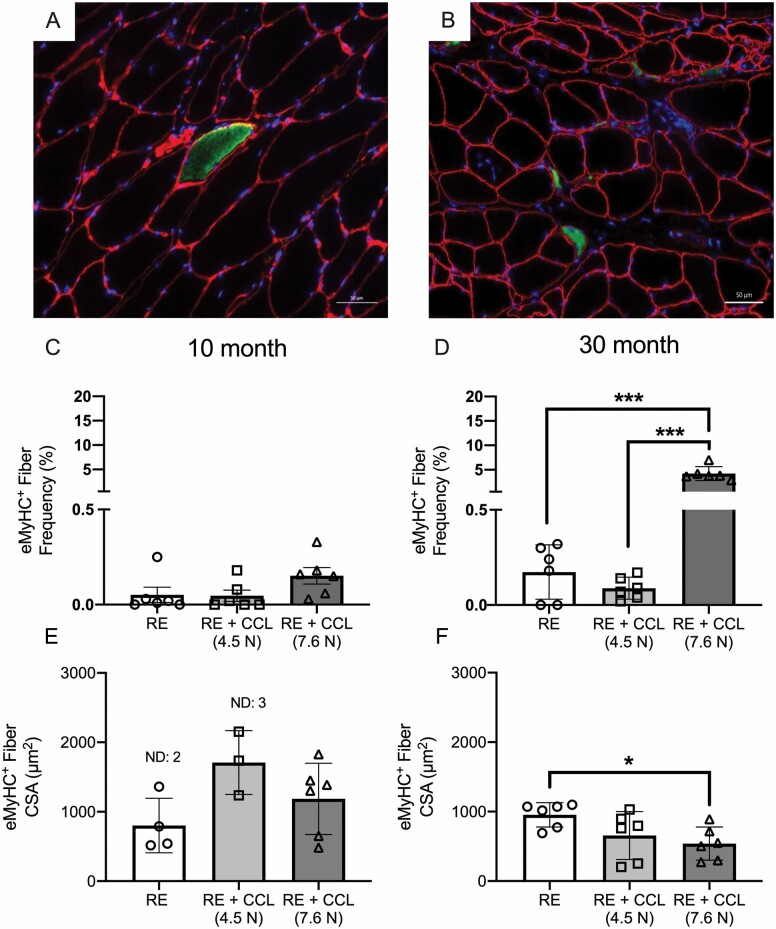

Higher CCL Is Associated With Elevated Small eMyHC Expressing Fibers in Muscles From Older Adult Rats

The observation of a higher percentage of small muscle fibers present in gastrocnemius 30-month-old RE + CCL (7.6 N) rats suggested that there might be newly developing muscle fibers. Therefore, we immunoreacted gastrocnemius cross-sections with anti-eMyHC antibody. Representative images from gastrocnemius muscle from 30-month-old RE (Figure 3A) and RE + CCL 7.6 N (Figure 3B) show that there is a marked elevation in eMyHC+ (green) fibers following CCL at 7.6 N load. Moreover, representative images of muscles from 30-month-old RE (Figure 3A) and 30-month-old RE + CCL 7.6 N (Figure 3B) show eMyHC+ fibers (green) are smaller in size in muscles that have undergone CCL (7.6 N) during reloading. Quantification indicated no differences in the frequency of eMyHC+ muscle fibers in 10-month-old RE + CCL compared to 10-month-old RE at 7.6 N load, with less than 0.25% of total fibers expressing eMyHC in either group (Figure 3C). However, in gastrocnemius muscle of 30-month-old rats, there was a 16-fold higher number of eMyHC+ muscle fibers in RE + CCL (7.6N) compared to RE (Figure 3D). Similarly, CSA of eMyHC+ muscle fibers was not different in gastrocnemius muscle of 10-month-old RE rats compared to RE + CCL (7.6 N), but was significantly lower in RE + CCL (7.6 N) at 30 months of age compared to RE (Figure 3E and F, respectively). Note that in 10-month-old rats, some gastrocnemius muscles showed no eMyHC+ fibers, while all muscles in 30-month-old rats did. To investigate whether CCL at any load induced the differences in eMyHC between adult and older adult rats, we used muscles that had received CCL at 4.5 N load from a previous study for comparison (11,12). Neither frequency nor CSA of eMyHC+ fibers was different with 4.5 N CCL in 10- or 30-month-old rats, indicating that the higher load (7.6 N) specifically induced the observed differences in the older adult rats (Figure 3C–F, respectively). For reference, the frequency and CSA for eMyHC+ fibers for WB and HS gastrocnemius for 10- and 30-month-old rats are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 3.

CCL at 7.6 N is associated with a higher frequency of small eMyHC+ muscle fibers. Representative images of eMyHC+ fiber size in (A) older adult RE and (B) older adult RE + CCL (7.6 N) gastrocnemius muscle. Quantification of eMyHC+ fiber frequency for (C) adult and (D) older adult rats recovering without or with CCL at 4.5 and 7.6 N loads. Quantification of eMyHC+ fiber size for (E) adult and (F) older adult rats recovering without or with CCL at 4.5 and 7.6 N loads. Values presented as mean ± SEM; n = 6 for all groups. *p < .05, ***p < .0001 denote statistical significance. Scale bar of images A and B is 50 μm. RE = reloaded; CCL = cyclic compressive loading; CSA = cross-sectional area.

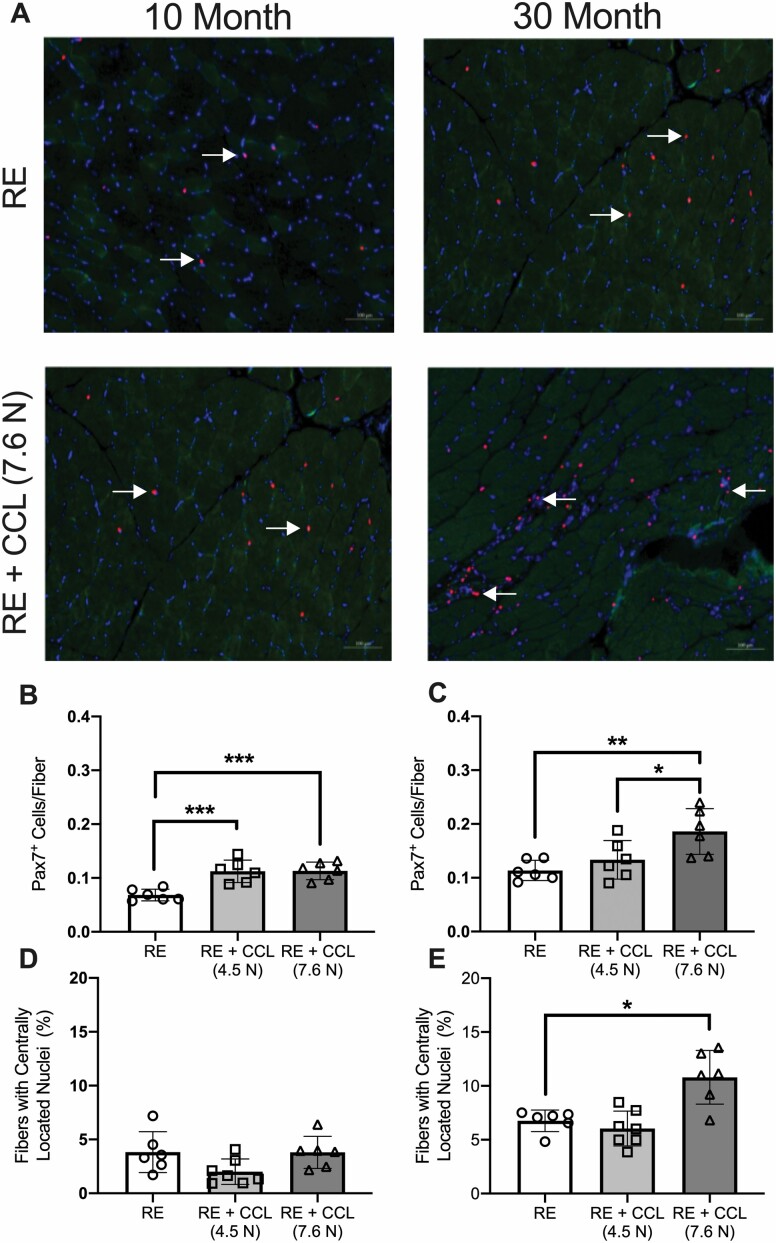

Muscles Receiving Higher CCL During Reloading Show Muscle Damage in Older Adult Rats

In order to determine whether the increase in eMyHC+ muscle fibers in 30-month-old RE + CCL (7.6 N) was reflective of muscle damage, we characterized the muscle morphology. As a comparison, we included sections from muscles that had undergone 4.5 N load CCL. Presence of laminin+/dystrophin− muscle fibers was observed only in 30-month-old RE + CCL (7.6 N) rats (Figure 4F and H, respectively; indicated by white arrows). Importantly, the absence of dystrophin protein in laminin-outlined muscle fibers was not observed in any of the groups for the 10-month-old rats (Figure 4A–C), nor in 30-month-old RE (Figure 4D) or RE + CCL (4.5 N) (Figure 4E; indicated by yellow arrows). Areas of muscle containing laminin+/dystrophin− muscle fibers in 30-month-old RE + CCL (7.6 N) rats consistently displayed elevated eMyHC+ muscle fibers (indicated by red arrow) and central nucleation, altogether indicative of muscle damage (34) (Figure 4H). Satellite cells were then identified with anti-Pax7 antibody (Figure 5A); satellite cell abundance for 10-month-old gastrocnemius muscle has been previously published and was used as a comparison only (11). Satellite cell abundance was higher with both 4.5 and 7.6 N loads in 10-month-old rats, but there was no difference between loads (Figure 5B). By contrast, satellite cell abundance in gastrocnemius muscles from 30-month-old rats was elevated with 7.6 N, but not 4. 5 N load (Figure 5C). Quantification of central nucleation indicated that there were no differences between RE and RE + CCL at either the 4.5 N or the 7.6 N load in 10-month-old rats (Figure 5D), with multiple rats having no centrally located nuclei at all. By contrast, there was a load-dependent 2-fold elevation in the number of fibers containing centrally located nuclei in 30-month-old RE + CCL (7.6 N) rats compared with RE rats (Figure 5E). For reference, central nucleation and satellite cell abundance for WB and HS for 10- and 30-month-old rats are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 4.

CCL at 7.6 N exclusively damages gastrocnemius muscles from older adult rats. Muscle sections from gastrocnemius muscle immunoreacted or stained with DAPI (blue), eMyHC (red), dystrophin (violet), and laminin (green) for adult RE (A), aged RE (B), adult RE + CCL 4.5 N (C), aged RE + CCL 4.5 N (D), adult RE + CCL 7.6 N (E), and aged RE + CCL 7.6 N (F). Scale bar is 50 μm (A–F). Magnified representative images of older adult rats receiving 4.5 N CCL (G) and 7.6 N CCL (H). Scale bar is 10 μm (G, H). White arrow indicates dystrophin−/laminin+ muscle fibers, yellow arrow indicates dystrophin+/laminin+ muscle fibers. Red arrow indicates the presence of eMyHC expression. RE = reloaded; CCL = cyclic compressive loading; DAPI = 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

Figure 5.

Higher central nucleation and satellite cell abundance are indicative of muscle damage following elevated CCL in older adult rats. (A) Representative images of satellite cell abundance (red) between 10- and 30-month-old rats, with and without 7.6 N mechanotherapy during regrowth. Satellite cell abundance in gastrocnemius muscles from (B) adult and (C) older adult rats with and without CCL. Number of fibers with centrally located nuclei between (D) adult and (E) older adult rats recovering from atrophy with and without CCL. Values presented as mean ± SEM; n = 6 for all groups. *p < .05, **p < .001, ***p < .0001 denote statistical significance. RE = reloaded; CCL = cyclic compressive loading.

Discussion

The principal finding of the current study is that increasing the load of mechanotherapy to account for age-related transverse stiffness did not improve net protein balance or enhance muscle size following 7 days of regrowth. In addition, the added load was damaging to older adult rat skeletal muscle and did not induce muscle growth. Neither the 4.5 nor the 7.6 N load of CCL had an anabolic effect during the recovery period following atrophy, even though the 4.5 N load enhanced muscle mass recovery in adult rats (11). Moreover, while the 7.6 N load was not damaging to adult rat skeletal muscle, it also did not induce a growth response. Therefore, our hypothesis was disproven and importantly we show that adult and older adult rats have distinct responses to mechanotherapy. Findings from this study suggest that age is an important variable when considering the load used during mechanotherapy and also that age-related transverse stiffness may predispose older adults to damage during the recovery period following disuse atrophy.

In the current study, we hypothesized that the elevated stiffness of aged muscle blunted the mechanical stimulus of mechanotherapy, and therefore a greater stimulus would be required to induce mechanosensitive and anabolic signaling. Indeed, in a similar study comparing the age-related responsiveness to the mechanical stimulus of reloading, it was found that regrowth was blunted in older adult compared to adult rats for fast-twitch muscles (15). It was concluded that Akt signaling was either impaired and/or delayed in aged muscle in response to loading, and it would require a greater stimulus to activate signaling (15). In our study, the application of a higher load had no effect on protein turnover nor mean fiber CSA, demonstrating that a greater stimulus alone is not an effective strategy to enhance muscle mass recovery in older adult rats at the selected timepoint. While there were no differences in protein turnover or mean fiber CSA in our study, the observation of an aberrant laminin/dystrophin membrane morphology in older adult rats is notable due to its implications for mechanotransduction and cell signaling (35). Mechanotransduction relies on the delivery of mechanical signals through the extracellular matrix (ECM) to the muscle, via mechanosensing signaling molecules such as integrin-linked protein kinase (ILK) and focal adhesion kinase (35). Increased stiffness of the ECM, including laminin, can change muscle cell signaling through a phenomenon known as stress-shielding, which is defined as asymmetrical load distribution between muscle and its associated connective tissue due to diverging mechanical characteristics between the 2 tissues (36). The stiffer ECM in aged muscle bears a disproportionate amount of mechanical load compared to adult leading to reduced mechanical signaling to the underlying musculature (36). In our data, it is possible that elevated age-related stiffness decreases the mechanosensing abilities of muscle cells. Indeed, we have previously shown that mechanosignaling molecules ILK and integrins are lower in older adult rat muscle compared to adult following a single bout of mechanotherapy (28), and it has also been shown that muscle membrane proteins such as dystrophin are decreased with age (37). While the timing of muscle harvesting in our study made it difficult to determine changes in signaling, it is possible that stress-shielding of the ECM and lower muscle mechanosignaling molecules impair the ability to receive mechanical signals important for muscle mass recovery following atrophy.

Increasing the force applied to muscles recovering from disuse was ineffective in aiding muscle mass recovery, while also damaging to muscles of older adult rats. Previous studies have reported that muscles from older adults are more susceptible to damage compared to younger adults in response to exercise and muscle contractions. Both older men (38) and women (39) show higher susceptibility to damage to varying degrees following eccentric exercise protocols, depending on the protocol used. It has been postulated that the age-related susceptibility to damage is due to lower muscle mass and consequently fewer and/or weaker sarcomeres (40,41). Specifically, Lynch et al. (42) found that the “breakage rate” following a series of lengthening contractions was higher in older adult rat muscle fibers compared to adult, which the authors concluded to be due to a weaker contractile apparatus in older adult rats. Importantly, the influence of muscle contraction is absent in the current study due to the perpendicular application of the load and also that rats were anesthetized during CCL. In the absence of active tension produced by the contractile apparatus, passive tension is produced primarily by the sarcomere protein Titin (43) and by the ECM (44), while the ECM has been reported to undergo significant changes with aging (22,40). Specifically, ECM collagens have been shown to undergo posttranslational modifications such as cross-linking (40) and advanced glycation end products (45), which contribute to an overall stiffening of muscle ECM with aging (40). A stiffer ECM has been postulated to predispose older adults to damage by compromising the compliance of the ECM (46,47). In a recent report, Pavan et al. investigated the influence of the aging ECM on muscle stiffness and compliance in older individuals by subjecting fiber bundles with and without intact ECM to elongation. It was shown that stiffness from bundles, but not fibers (without intact ECM), contributed to elevated muscle stiffness and decreased compliance in the aged (47). Reduced compliance increases the vulnerability of tissue damage following mechanical deformation (48). In our data, it is likely that a stiffer muscle, likely attributed to the ECM, predisposed older adult rats to muscle damage following CCL at a higher load, while a more compliant ECM in muscles from adult rats protected the underlying musculature from damage. Findings from the current study imply interventions validated for use in younger adult populations may not be appropriate for older adults recovering from disuse atrophy, because of the difference in material properties of muscle ECM with age. While the damage was observed following CCL at a higher load in aged muscle recovering from disuse, it is possible that the elevated load of CCL is damaging to aged muscle under normal ambulatory conditions as well, as the load used in our current study was determined using the differences in passive stiffness between adult and aged ambulatory muscles. The data presented in our present study do not allow for determinations of whether the damage will contribute to muscle dysfunction long term or whether the eMyHC+ fibers in aged muscle will contribute to enhanced muscle size at later timepoints. Future studies investigating how the age-related changes in ECM contribute to differential responses to mechanical stimuli will aid in tailoring interventions appropriately for older adults recovering from disuse atrophy.

An interesting finding from the current study is that there was no anabolic effect of CCL during the recovery period following atrophy when adult rats were subjected to the higher, 7.6 N load in contrast to the previously reported growth effect with 4.5 N load (11). Importantly, neither the 4.5 N load nor the 7.6 N load was damaging to adult rat skeletal muscle, as opposed to the 11 N load of CCL which induced edema in muscle from adult rats (29). The differences in damage-inducing and anabolic effects between adults and older adults suggest a so-called “Goldilocks” effect of massage as a mechanotherapy. Murach et al. (49) recently described the Goldilocks effect in terms of the appropriate amount of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) signaling produced by satellite cells to induce ECM remodeling and long-term hypertrophic growth. It was reported that too little or too much MMP9 signaling was insufficient to create a hospitable environment for myofiber hypertrophy. For our study results, it could be speculated that an appropriate dose of mechanical loading is required to activate mechanosensitive signaling pathways and subsequent anabolism. In other words, the dose of loading must be sufficient to activate cellular pathways without damaging the underlying musculature. The current study not only highlights this principle of loading in adult rats but also suggests that the Goldilocks effect of mechanical loading changes with age, potentially due to altered mechanical properties of the ECM in older adults. These findings have important clinical implications for the rehabilitation of older adult human muscle after disuse. As muscles from older adults are typically stiffer, increasing the force of mechanotherapy may not be an effective strategy as the therapy may become damaging. Efforts to reduce ECM stiffness may be an effective strategy to increase the usefulness of mechanotherapy for muscle mass interventions.

In conclusion, the primary finding of the current study is that increasing the load of mechanotherapy to overcome transverse muscle stiffness and enhance anabolic responses in older adult rats is ineffective at the presented timepoint. It is currently unclear whether mechanotherapy at later timepoints during recovery would be beneficial. The secondary finding is that CCL at high loads is damaging to muscles recovering from disuse in older adult rats only, as our data showed that the higher mechanical load was associated with indicators of muscle damage and regeneration. We also show that the previously reported anabolic effect of cyclic compressions in adult rats is absent with the higher load, highlighting the importance of dosage in mechanotherapy for muscle mass recovery. Taken together, our data emphasize a need to better understand age-related changes in muscle transverse stiffness in order to create therapies for older adults recovering from disuse.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants RO1AT009268 and R21AG042699 to T.A.B., B.F.M., and E.E.D.-V, University of Kentucky TL1 Predoctoral Fellowship UL1TR001998 to Z.R.H., and National Institutes of Health grant F31AT01147201 to Z.R.H.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Author Contributions

Z.R.H. was responsible for acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data and drafting and revising the manuscript; K.H., A.L.C., and M.M.L. were responsible for acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; B.F.M., T.A.B., and E.E.D.-V. were responsible for conception and design of the experiments, acquisition of data, interpretation of the results, and critically revising the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed. The current institution for M.M.L. is Southern Utah University, Department of Kinesiology and Outdoor Recreation, Cedar City, UT.

References

- 1. Larsson L, Degens H, Li M, et al. Sarcopenia: aging-related loss of muscle mass and function. Physiol Rev. 2019;99:427–511. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00061.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. English KL, Paddon-Jones D. Protecting muscle mass and function in older adults during bed rest. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13:34–39. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328333aa66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hvid LG, Suetta C, Nielsen JH, et al. Aging impairs the recovery in mechanical muscle function following 4 days of disuse. Exp Gerontol. 2014;52:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miller BF, Baehr LM, Musci RV, et al. Muscle-specific changes in protein synthesis with aging and reloading after disuse atrophy. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019;10:1195–1209. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bodine SC. Disuse-induced muscle wasting. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45:2200–2208. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fragala MS, Cadore EL, Dorgo S, et al. Resistance training for older adults: position statement from the national strength and conditioning association. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;33:2019–2052. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000003230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schoenfeld BJ. The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24:2857–2872. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e840f3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Eftestøl E, Egner IM, Lunde IG, et al. Increased hypertrophic response with increased mechanical load in skeletal muscles receiving identical activity patterns. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2016;311:C616–C629. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00016.2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aguilar-Agon KW, Capel AJ, Martin NRW, Player DJ, Lewis MP. Mechanical loading stimulates hypertrophy in tissue-engineered skeletal muscle: molecular and phenotypic responses. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:23547–23558. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goodman CA, Dietz JM, Jacobs BL, McNally RM, You JS, Hornberger TA. Yes-Associated Protein is up-regulated by mechanical overload and is sufficient to induce skeletal muscle hypertrophy. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:1491–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.04.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller BF, Hamilton KL, Majeed ZR, et al. Enhanced skeletal muscle regrowth and remodelling in massaged and contralateral non-massaged hindlimb. J Physiol. 2018;596:83–103. doi: 10.1113/JP275089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lawrence MM, Van Pelt DW, Confides AL, et al. Muscle from aged rats is resistant to mechanotherapy during atrophy and reloading. Geroscience. 2021;43:65–83. doi: 10.1007/s11357-020-00215-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. White JR, Confides AL, Moore-Reed S, Hoch JM, Dupont-Versteegden EE. Regrowth after skeletal muscle atrophy is impaired in aged rats, despite similar responses in signaling pathways. Exp Gerontol. 2015;64:17–32. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2015.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baehr LM, West DW, Marcotte G, et al. Age-related deficits in skeletal muscle recovery following disuse are associated with neuromuscular junction instability and ER stress, not impaired protein synthesis. Aging (Albany NY). 2016;8:127–146. doi: 10.18632/aging.100879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hwee DT, Bodine SC. Age-related deficit in load-induced skeletal muscle growth. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:618–628. doi: 10.1186/2044-5040-1-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fry CS, Drummond MJ, Glynn EL, et al. Aging impairs contraction-induced human skeletal muscle mTORC1 signaling and protein synthesis. Skelet Muscle. 2011;1:11. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00296.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kirby TJ, Lee JD, England JH, Chaillou T, Esser KA, McCarthy JJ. Blunted hypertrophic response in aged skeletal muscle is associated with decreased ribosome biogenesis. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2015;119:321–327. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00296.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Burd NA, Gorissen SH, van Loon LJ. Anabolic resistance of muscle protein synthesis with aging. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2013;41:169–173. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e318292f3d5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. West DWD, Marcotte GR, Chason CM, et al. Normal ribosomal biogenesis but shortened protein synthetic response to acute eccentric resistance exercise in old skeletal muscle. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1915. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rasmussen BB, Fujita S, Wolfe RR, et al. Insulin resistance of muscle protein metabolism in aging. FASEB J. 2006;20:768–769. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4607fje [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hornberger TA, Mateja RD, Chin ER, Andrews JL, Esser KA. Aging does not alter the mechanosensitivity of the p38, p70S6k, and JNK2 signaling pathways in skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2005;98:1562–1566. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00870.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Alnaqeeb MA, Al Zaid NS, Goldspink G. Connective tissue changes and physical properties of developing and ageing skeletal muscle. J Anat. 1984;139 (Pt 4):677–689. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Qiu H, Zhu Y, Sun Z, et al. Short communication: vascular smooth muscle cell stiffness as a mechanism for increased aortic stiffness with aging. Circ Res. 2010;107:615–619. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.221846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lieber SC, Aubry N, Pain J, Diaz G, Kim SJ, Vatner SF. Aging increases stiffness of cardiac myocytes measured by atomic force microscopy nanoindentation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H645–H651. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00564.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schulze C, Wetzel F, Kueper T, et al. Stiffening of human skin fibroblasts with age. Biophys J. 2010;99:2434–2442. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.08.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ochala J, Frontera WR, Dorer DJ, Van Hoecke J, Krivickas LS. Single skeletal muscle fiber elastic and contractile characteristics in young and older men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:375–381. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.4.375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lawrence MM, Van Pelt DW, Confides AL, et al. Massage as a mechanotherapy promotes skeletal muscle protein and ribosomal turnover but does not mitigate muscle atrophy during disuse in adult rats. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2020;229:e13460. doi: 10.1111/apha.13460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Van Pelt DW, Confides AL, Abshire SM, Hunt ER, Dupont-Versteegden EE, Butterfield TA. Age-related responses to a bout of mechanotherapy in skeletal muscle of rats. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2019;127:1782–1791. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00641.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Waters-Banker C, Butterfield TA, Dupont-Versteegden EE. Immunomodulatory effects of massage on nonperturbed skeletal muscle in rats. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2014;116:164–175. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00573.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang Q, Zeng H, Best TM, et al. A mechatronic system for quantitative application and assessment of massage-like actions in small animals. Ann Biomed Eng. 2014;42:36–49. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0886-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miller BF, Wolff CA, Peelor FF 3rd, Shipman PD, Hamilton KL. Modeling the contribution of individual proteins to mixed skeletal muscle protein synthetic rates over increasing periods of label incorporation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2015;118:655–661. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00987.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Busch R, Kim YK, Neese RA, et al. Measurement of protein turnover rates by heavy water labeling of nonessential amino acids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1760:730–744. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wen Y, Murach KA, Vechetti IJ Jr, et al. MyoVision: software for automated high-content analysis of skeletal muscle immunohistochemistry. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2018;124:40–51. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00762.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mackey AL, Kjaer M. The breaking and making of healthy adult human skeletal muscle in vivo. Skelet Muscle. 2017;7:24. doi: 10.1186/s13395-017-0142-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alenghat FJ, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction: all signals point to cytoskeleton, matrix, and integrins. Sci STKE. 2002;2002:pe6. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.119.pe6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Driscoll M, Blyum L. The presence of physiological stress shielding in the degenerative cycle of musculoskeletal disorders. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2011;15:335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2010.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hughes DC, Marcotte GR, Marshall AG, et al. Age-related differences in dystrophin: impact on force transfer proteins, membrane integrity, and neuromuscular junction stability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72:640–648. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fernandes JFT, Lamb KL, Twist C. Exercise-induced muscle damage and recovery in young and middle-aged males with different resistance training experience. Sports (Basel). 2019;7(6):132. doi: 10.3390/sports7060132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roth SM, Martel GF, Ivey FM, et al. High-volume, heavy-resistance strength training and muscle damage in young and older women. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2000;88:1112–1118. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.3.1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wood LK, Kayupov E, Gumucio JP, Mendias CL, Claflin DR, Brooks SV. Intrinsic stiffness of extracellular matrix increases with age in skeletal muscles of mice. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2014;117:363–369. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00256.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Close GL, Kayani A, Vasilaki A, McArdle A. Skeletal muscle damage with exercise and aging. Sports Med. 2005;35:413–427. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200535050-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lynch GS, Faulkner JA, Brooks SV. Force deficits and breakage rates after single lengthening contractions of single fast fibers from unconditioned and conditioned muscles of young and old rats. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C249–C256. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.90640.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brynnel A, et al. Downsizing the molecular spring of the giant protein titin reveals that skeletal muscle titin determines passive stiffness and drives longitudinal hypertrophy. Elife. 2018;7:40532. doi: 10.7554/eLife.40532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Marcucci L, Bondì M, Randazzo G, Reggiani C, Natali AN, Pavan PG. Fibre and extracellular matrix contributions to passive forces in human skeletal muscles: an experimental based constitutive law for numerical modelling of the passive element in the classical Hill-type three element model. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0224232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Haus JM, Carrithers JA, Trappe SW, Trappe TA. Collagen, cross-linking, and advanced glycation end products in aging human skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2007;103:2068–2076. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00670.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kostrominova TY, Brooks SV. Age-related changes in structure and extracellular matrix protein expression levels in rat tendons. Age (Dordr). 2013;35:2203–2214. doi: 10.1007/s11357-013-9514-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pavan P, et al. Alterations of extracellular matrix mechanical properties contribute to age-related functional impairment of human skeletal muscles. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(11):3992. doi: 10.3390/ijms21113992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Li W. Damage models for soft tissues: a survey. J Med Biol Eng. 2016;36:285–307. doi: 10.1007/s40846-016-0132-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Murach KA, Vechetti IJ Jr, Van Pelt DW, et al. Fusion-independent satellite cell communication to muscle fibers during load-induced hypertrophy. Function (Oxf). 2020;1:zqaa009. doi: 10.1093/function/zqaa009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.