Abstract

Although mitogenic and differentiating factors often activate a number of common signaling pathways, the mechanisms leading to their distinct cellular outcomes have not been elucidated. In a previous report, we demonstrated that mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase (ERK) activation by the neurogenic agents fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and nerve growth factor is dependent on protein kinase Cδ (PKCδ), whereas MAP kinase activation in response to the mitogen epidermal growth factor (EGF) is independent of PKCδ in rat hippocampal (H19-7) and pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells. We now show that EGF activates MAP kinase through a PKCζ-dependent pathway involving phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and PDK1 in H19-7 cells. PKCζ, like PKCδ, acts upstream of MEK, and PKCζ can potentiate Raf-1 activation by EGF. Inhibition of PKCζ also blocks EGF-induced DNA synthesis as monitored by bromodeoxyuridine incorporation in H19-7 cells. Finally, in embryonic rat brain hippocampal cell cultures, inhibitors of PKCζ or PKCδ suppress MAP kinase activation by EGF or FGF, respectively, indicating that these factors activate distinct signaling pathways in primary as well as immortalized neural cells. Taken together, these results implicate different PKC isoforms as determinants of growth factor signaling specificity within the same cell. Furthermore, these data provide a mechanism whereby different growth factors can differentially activate a common signaling intermediate and thereby generate biological diversity.

Treatment of cells with different growth factors such as epidermal growth factor (EGF) or fibroblast-derived growth factor (FGF) often leads to distinct biological outcomes such as mitogenesis, neurogenesis, or apoptosis. Since these factors stimulate tyrosine kinase receptors that in turn activate common signaling cascades, the explanation for these differences in specificity has not been obvious. In general, two types of models have been proposed. First, it is possible that the same intermediates are utilized by both receptors, but the variations in activation kinetics, signal amplitude, or cellular localization result in different outputs. Second, it is possible that distinct intermediates are responsible for the differences in specificity. These two models can be reconciled if the same general families of signaling molecules are utilized by both receptor systems, but differences in the specific isoforms generate diversity in kinetics, amplitude, localization, or substrate selectivity.

One of the major targets of growth factor stimulation that can lead to diverse endpoints dependent on the degree of activation is the Ras/Raf/MEK/mitogen-activated protein (MAPK) kinase signaling cascade. Although activated Ras and Raf were originally identified as mediators of neoplastic transformation, recent studies have suggested that these proteins can promote cell cycle arrest, differentiation, and even apoptosis in normal cells (49, 71). For example, in NIH 3T3 cells, moderate Raf activation elicits cell proliferation, but high activation leads to reversible p21-mediated cell cycle arrest (71). Expression of activated Raf in nonimmortalized human lung fibroblasts results in rapid and irreversible cell cycle arrest and senescence mediated by the cdk4 inhibitor p16 (75). In these examples, regulation of inhibitors of the cell cycle-dependent kinases by Raf can lead to a feedback inhibition of cellular growth. Expression of other proteins such as Fos and Jun during the G1 phase of the cell cycle can also vary dependent on the duration of the MAPK (ERK) signal (12). Thus, the extent of MAPK activation may influence the outcome of growth factor signaling cascades.

Recently, we have shown that activation of ERK by FGF or nerve growth factor but not EGF requires selective activation of a specific protein kinase C (PKC) isoform, PKCδ, in neuronal cells (13). More than 10 PKC isoforms have been cloned and can be categorized according to endogenous and exogenous activators (reviewed by Dekker and Parker [15]). Phorbol esters and diacylglycerol activate classical (α, βI, βII, γ) and novel (δ, ɛ, η, θ, and ν) PKC isoforms, with the activation of the former also requiring calcium. Activation of the atypical isoforms (ι/λ and ζ) is independent of both calcium and phospholipids. Many of the PKCs, including the atypical isoform PKCζ, have been shown to be involved in ERK activation (4, 6, 7, 16, 41, 55, 64, 66).

PKCζ has been implicated in several cellular processes including apoptosis, protein synthesis, and differentiation (3, 18, 42, 46, 69, 72). Recently, this isoform was shown to be involved in the activation of p70S6K by EGF in a phosphatidylinositol-3′ kinase (PI-3 kinase) and 3′-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1)-dependent manner (51). Similarly, PKCζ cooperates with PI-3 kinase-γ to mediate Ras-independent ERK activation by a Gi protein-coupled receptor (63). PKCζ mediates platelet-derived growth factor-induced ERK activation by a Raf-1 and phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C (PC-PLC)-dependent cascade in Rat-1 cells (6, 66). PC-PLC and PKCζ are also required for lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced ERK activation in macrophages (45). Most recently, PKCζ was implicated in the activation of ERK by insulin in adipocytes (52). Finally, a dominant-negative mutant of PKCζ severely impairs activation of MAP/ERK kinase (MEK) and ERK by serum and tumor necrosis factor alpha (4). Thus, PKCζ seems to play a role in growth factor-induced ERK activation in a variety of cell types.

In this study, we investigated the role of PKCζ as a mediator of EGF-induced ERK activation in a conditionally immortalized rat hippocampal cell line (H19-7) and in primary rat embryonal hippocampal cells. The H19-7 cell line was generated by transducing rat E17 hippocampal cells with a retroviral vector expressing a temperature-sensitive simian virus 40 large T antigen (21). At the permissive temperature (33°C) when the large T antigen is expressed, cells proliferate in response to EGF. When shifted to the nonpermissive temperature (39°C) where the large T antigen is inactivated, H19-7 cells express neuronal differentiation markers upon stimulation by FGF but not EGF (21, 36, 37). Furthermore, like other conditionally immortalized neuronal cell lines (57), H19-7 cells are progenitor cells capable of migration and neuronal differentiation when grafted into the hippocampi of postnatal rats (U. Englund, R. A. Fricker, E. M. Eves, M. R. Rosner, and K. Wictorin, unpublished data). In a previous study, we demonstrated that PKCδ can mediate MEK/ERK activation and neuritogenesis in both H19-7 and PC12 cells in response to neurogenic factors (13).

We now demonstrate that a parallel but distinct cascade involving PKCζ is required for EGF-induced ERK activation and mitogenesis in H19-7 cells. PKCζ is activated by EGF in a PI-3 kinase- and PDK1-dependent manner and, like PKCδ, activates ERK upstream of MEK. Furthermore, studies with selective PKC inhibitors indicate that ERK activation by EGF or FGF requires PKCζ or PKCδ, respectively, in primary embryonal hippocampal cells. Taken together, these results demonstrate that PKCζ mediates EGF-induced ERK activation by MEK in neuronal cells and provide evidence that different PKC isoforms play a role in mediating the specific effects of various growth factors in the same cell type.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Receptor-grade EGF was purchased from Biomedical Technologies Inc. (Stoughton, Mass.). Basic FGF (bFGF) was purchased from Research Diagnostics Inc. (Flanders, N.J.). Normal goat serum (NGS) was purchased from Vector Laboratories, Inc. (Burlingame, Calif.). 5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU), 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (FrdU), phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), wortmannin, myelin basic protein (MBP), peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (IgG), LY294002, and peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). Myristolated PKCζ pseudosubstrate peptide was purchased from Quality Controlled Biochemicals (Hopkinton, Mass.). Rotterlin and chelerythrine chloride were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, Calif.). Fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-mouse was purchased from ICN/Cappel (Durham, N.C.). Anti-MAPK antiserum Ab283 was developed as previously described (36). Monoclonal antibodies 12CA5 and HA.11 (against the hemagglutinin [HA] epitope and 9E10 (against the Myc epitope) were purchased from BAbCo (Emeryville, Calif.). Monoclonal BrdU antibody Ab-2 was purchased from Oncogene Research Products (Cambridge, Mass.). High-affinity rat anti-HA monoclonal antibody 3F10 and peroxidase-conjugated, affinity-purified sheep anti-rat Fab Ig were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapolis, Ind.). Anti-phospho-MAPK (T202/Y204) and MEK1/2 (Ser217/221) polyclonal antibodies and ERK2(K52R) were purchased from New England BioLabs (Beverly, Mass.). Monoclonal antibody M5 against the FLAG epitope and X-Omat film were purchased from Eastman Kodak Co. (New Haven, Conn.). PKCζ antibody C-20 and full-length MEK (MEK-FL) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, Calif.). The PKC monoclonal antibody sampler kit was purchased from Transduction Labs (Lexington, Ky.). The anti-phospho-PKCζ antibody directed against the phosphothreonine at residue 410 (Thr410) was kindly provided by A. Toker (Boston Biomedical Research Institute, Boston, Mass.). Protein G-Sepharose (4 Fast Flow) was purchased from Pharmacia Biotech AB (Uppsala, Sweden). Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents and [γ32P]ATP (6,000 Ci/mmol) were purchased from DuPont/NEN Research Products (Boston, Mass.). The ECL-Plus Western blotting detection system was from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Piscataway, N.J.). The purified, kinase-dead MEK [MEK(K97A)] was a gift from Angus MacNichol (University of Chicago).

Plasmids.

The activated MEK2E and HA-tagged mouse ERK2 constructs were described previously (36). The FLAG-Raf construct was a gift from Andrey Shaw (Washington University). HA-tagged PKCζ constructs were described previously (59). Myc-tagged p110 was a gift from J. Downward (Imperial Cancer Research Fund, London, England). Myc-tagged PDK1 constructs were a gift from A. Toker. HA-MEK1 was a gift from M. Marshall (Indiana University). Plasmid DNAs were prepared by CsCl-ethidium bromide gradient centrifugation as previously described (36) or by purification through columns as instructed by the manufacturer (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.).

Cell culture.

The immortalized H19-7 cells were generated from embryonic rat hippocampal cells as previously described (21). Cells were maintained in 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and 400 μg of G418 at 33°C. Cells were serum starved in N2 medium overnight prior to treatment.

Dissection and culture of primary rat hippocampal cells.

Hippocampi were dissected from E16 Sprague-Dawley (Harlan Sprague Dawley, Indianapolis, Ind.) rat embryos and placed in cold 25 mM HEPES buffer plus additives as described elsewhere (47). The hippocampal pieces were triturated 15 times with a P-1000 Pipetman pipette and allowed to settle for 5 min. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 250 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was then resuspended and plated as described previously (24). Briefly, the cells were resuspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium–Ham's F-12 (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) with insulin (25 μg/ml), transferrin (100 μg/ml), 60 μM putrescine, 30 nM sodium selenite, 20 nM progesterone, and sodium pyruvate (0.11 mg/ml). The cells were plated onto polyornithine- and fibronectin-coated 12- and 6-well tissue culture dishes at 2.5 × 105 and 5 × 105 cells/well, respectively. The cultures were grown in 5% CO2 at 37°C, and fresh medium was added every other day. bFGF (10 ng/ml) was added to the medium for the first 4 days in culture to enhance proliferation, and then the cells were allowed to differentiate without bFGF for 4 days.

Immunochemistry.

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in 0.5% NGS–0.01% Triton X-100–PBS for 2 h, washed with PBS for 30 min, incubated with Texas red-conjugated secondary antibodies (Cappel, Durham, N.C.), and washed with PBS for 30 min. The cells were characterized with antibodies to nestin (Rat-401; Developmental Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, Iowa), microtubule-associated protein 2, (MAP-2) (HM-2; Sigma), and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; DAKO, Carpinteria, Calif.). Cells were assessed at 400× with an inverted fluorescence Leica microscope supplied with rhodamine filters.

Transient transfections.

Cells (2 × 106) were seeded on 100-mm-diameter plates and incubated overnight. The medium was changed to serum-free OptiMem (Gibco/BRL), and cells were transfected with a total of 20 μg of plasmid DNA and 80 μl of TransIt LT-1 as specified by the manufacturer (Pan Vera Corp., Madison, Wis.). Ten percent of the total plasmid DNA consisted of pGreen Lantern-1 (Gibco/BRL), and the percentage of green fluorescent protein-expressing cells was scored to normalize transfection efficiency between groups. Cells were split (1:2) 24 h posttransfection and kept quiescent for 16 h prior to treatment and harvesting. All experiments were done 48 h posttransfection.

Treatment of cells with phosphorothioate-modified oligonucleotides.

H19-7 cells were seeded at 2 × 105/well in six-well poly-l-lysine-coated plates and transfected with 10 μg of oligonucleotide, using 40 μl of TransIt LT-1 according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were left to incubate for 48 h and then switched to N2 medium at 39°C, and a further 30 μM (final concentration) oligonucleotide was added for 48 h prior to treatment. The antisense sequences used were 5′ GAAGGAGATGCGCTGGAA 3′ for PKCδ and 5′ GTCGGTCCTGCTGGGCAT 3′ for PKCζ (22). The antisense sequence for PKCδ is based on nucleotides 10 to 27 of the murine coding sequence, while the sequence for PKCζ is based on the start codon plus the next 15 downstream nucleotides. The appropriate sense sequence was used as control.

In vitro FLAG-Raf, HA-MEK1, HA-PKCζ, and HA-ERK2 kinase assays.

FLAG-Raf, HA-MEK1, HA-PKCζ, and HA-ERK2 were overexpressed in H19-7 cells as described above. Cells were then treated with or without the appropriate growth factor followed by two washings with ice-cold PBS. Cells were lysed with 1% Triton-based lysis buffer (TLB) containing 1% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 40 mM β-glycerophosphate, 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM NaF, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, aprotinin (1 μg/ml), leupeptin (1 μg/ml), and 20 mM p-nitrophenyl phosphate and incubated on ice for 30 min. The cell debris was removed by centrifugation (14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C), and protein concentrations were determined by the Bio-Rad (Hercules, Calif.) protein assay using bovine serum albumin as the standard. Monoclonal antibodies M5 and HA.11, against the FLAG and HA epitopes, respectively, were coupled to protein G-Sepharose beads by adding 20 μg of M5 or HA.11 to 1 ml of a 50:50 slurry of protein G-Sepharose in TLB overnight at 4°C. Lysates were precleared with 50 μl of protein G-Sepharose for 30 min at 4°C; 40 μl of the antibody-protein G-Sepharose complex was added to 300 μg of cellular lysate protein and incubated for 2 h at 4°C. Immune complexes were then washed three times with TLB and two times in kinase buffer (1× kinase buffer is 25 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM MnCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.2 mM sodium vanadate). The final pellet was resuspended in 30 μl of kinase buffer, and reactions were started by addition of 50 μM ATP, 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP, and either 100 ng of purified MEK(K97A) or 1 μg of MEK-FL (for Raf kinase assays), 1 μg of ERK2 (K52R) (for MEK kinase assays), or 5 μg MBP (for ERK and PKCζ kinase assays) and carried out for 20 min at 30°C. Reactions were stopped by addition of 10 μl of 6× concentrated sample buffer and boiling for 5 min at 100°C. Beads were pelleted by centrifugation (14,000 rpm for 5 min), and supernatants were loaded onto a 10 or 13% acrylamide separating gel. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose and subjected to autoradiography.

Western analysis.

Cell extracts (10 to 20 μg) were resolved on a 10% acrylamide separating gel by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Membrane blocking, washing, antibody incubation, and detection by ECL were performed as previously described (37). When antibodies against phosphospecific peptides were used, blots were stripped by washing six times for 5 min each with TBS-T (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) (0.1%) at room temperature (RT), 30 min at 55°C with stripping buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 2% SDS, 100 mM 2-mercaptoethanol), and finally six times for 5 min each with TBS-T at RT. The stripped blots were then reprobed with the corresponding non-phosphospecific antibody to ensure equal protein loading.

Detection of proliferating cells by BrdU staining and immunofluorescence.

H19-7 cells (105) were plated at about 30% confluency in either 6- or 12-well poly-l-lysine-coated plates and treated with oligonucleotides as described above. Cells were then starved in 0.1% FBS at 33°C for 3 days and subsequently stimulated with 10 ng of bFGF or EGF per ml in the presence of 10 μM BrdU and 1 μM FrdU for 24 h. Cells were washed once with PBS and then fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol for 20 min at RT. Cells were then washed two times with deionized water followed by a 10-min incubation at RT with 2 N HCl to expose DNA. The acid was then neutralized with 0.1 M borate buffer (pH 8.7), and cells were rinsed once more with PBS. Block buffer (5% NGS and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS) was then added and left overnight at 4°C. The BrdU antibody was diluted 1:50 in 0.1× blocking buffer, and cells were incubated for 2 h at RT. Cells were then washed three times for 10 min each with PBS at RT followed by 1:300 fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse in 0.1× blocking buffer for 2 h at RT. Cells were given a final wash of (three times for 10 min each) with PBS and stored in the dark at 4°C in 0.05% sodium azide until fluorescence microscopy analysis. Cells were assessed at 400× with an inverted fluorescence Leica microscope.

Quantification of Western blots and autoradiographs.

Following antibody treatments, membranes were incubated with the ECL-Plus Western blotting detection system (Amersham) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For 32P incorporation, membranes were exposed to a storage phosphor screen (Molecular Dynamics). To quantify the signals, membranes or the phosphor screen were scanned by a Storm 860 PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics), and image and quantification analyses were carried out using ImageQuant 5.0 software (Molecular Dynamics). All values are reported as normalized to control, which was set to 1.

RESULTS

PI-3 kinase mediates EGF- but not FGF-induced ERK activation in H19-7 cells.

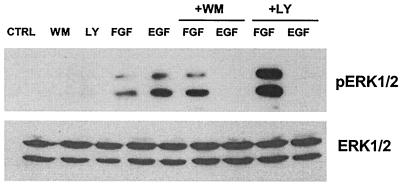

Our previous work demonstrated that the activation of ERK1 and -2 by EGF in H19-7 cells in N2 medium is inhibited by wortmannin, an inhibitor of PI-3 kinase. Since wortmannin is not a specific inhibitor of PI-3 kinase at the concentration used (200 nM) (14), a more specific inhibitor, LY294002 (68), was tested. As shown in Fig. 1, both wortmannin and LY294002 blocked EGF-induced ERK activation. In contrast, neither PI-3 kinase inhibitor suppressed ERK activation by FGF. This result confirms our previous findings that PI-3 kinase mediates EGF- but not FGF-induced ERK activation in H19-7 cells.

FIG. 1.

PI-3 kinase inhibitors selectively inhibit EGF-induced ERK activation in H19-7 cells. H19-7 cells in N2 medium at 39°C were either untreated (CTRL) or pretreated with 200 nM wortmannin (WM) or 50 μM LY290024 (LY) for 15 or 30 min, respectively. Cells were then left untreated or stimulated with 10 ng of FGF or EGF per ml for 10 min. After lysis, equal protein aliquots were resolved by SDS-PAGE (10% gel) and then immunoblotted with anti-phospho-ERK antibody. Membranes were then stripped and reprobed with anti-ERK antibody.

EGF but not FGF activates PKCζ in H19-7 cells.

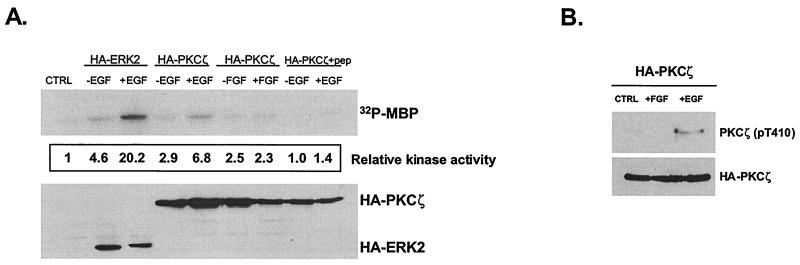

Since FGF selectively activates ERK in H19-7 cells via a PKCδ-dependent mechanism (13), we investigated the possibility that EGF activation of ERK occurs by a parallel but distinct PKC cascade. On the basis of expression and PKC inhibitor studies in H19-7 cells (13), only the atypical PKCs, ζ and ι/λ, are possible candidates. Given that EGF activates ERK in a PI-3 kinase-dependent manner and PKCζ has been shown to be a downstream effector of PI-3 kinase (28, 39, 62), we initially focused on PKCζ. To determine whether EGF stimulates PKCζ, the effect of EGF treatment on PKCζ activity was directly measured. H19-7 cells were transfected with an expression vector for HA-PKCζ and then either left untreated or stimulated with EGF or FGF. As shown in Fig. 2A, the in vitro kinase activity of HA-PKCζ, after normalization for protein expression, was higher when the enzyme was immunoprecipitated from EGF-treated cells. Addition of a PKCζ peptide inhibitor (58) to the kinase assay abrogated EGF-induced PKCζ kinase activity, indicating that the kinase reaction was specific for PKCζ. In contrast, FGF treatment of cells did not stimulate PKCζ. These results indicate that EGF but not FGF selectively activates PKCζ.

FIG. 2.

EGF selectively activates HA-PKCζ in H19-7 cells. (A) H19-7 cells were transfected with 8 μg of pcDNA3 (CTRL), 2 μg of HA-ERK2 plus 6 μg of pcDNA3, or 8 μg of HA-PKCζ. Cells were then switched to N2 medium at 39°C and left untreated or stimulated with 10 ng of FGF or EGF per ml for 10 min. Following treatment, cells were lysed, and HA-tagged constructs were immunoprecipitated with HA.11 antibody. The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE (13% gel) and assayed for ERK or PKCζ activity using MBP as a substrate as described in Materials and Methods. In one sample, 10 μM PKC peptide inhibitor (HA-PKCζ+pep) was added to the kinase mixture. Membranes were then probed for HA-tagged proteins using rat antibody 3F10. The amount of 32P incorporated into MBP was measured by PhosphorImager analysis and normalized to the amount of HA protein in each sample. The mock (CTRL) lane was arbitrarily set to 1. (B) H19-7 cells were transfected with 10 μg of HA-PKCζ. Cells were then switched to N2 medium at 39°C and left untreated or stimulated with 10 ng of FGF or EGF per ml for 10 min. Following treatment, cells were lysed, and HA-tagged constructs were immunoprecipitated with HA.11 antibody. The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE (10% gel) and immunoblotted with antibodies specific for phosphothreonine 410 (pT410) PKCζ. Membranes were then stripped and reprobed for HA-tagged proteins using rat antibody 3F10. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

Recent studies have shown that Thr410 is the site within the activation loop that must be phosphorylated for PKCζ activity (10, 39). PDK1, a downstream effector of PI-3 kinase, can phosphorylate Thr410 and activate the enzyme. To determine whether PKCζ isolated from EGF-stimulated cells is phosphorylated at this residue, H19-7 cells were transfected with HA-PKCζ and the cells were either left untreated or stimulated with EGF or FGF. HA-PKCζ was immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and then analyzed by immunoblotting with an antibody directed against the phosphorylated Thr410 residue. As shown in Fig. 2B, only the PKCζ expressed in the EGF-treated cells was phosphorylated at this site within the activation loop. These results support the previous finding that EGF but not FGF activates PKCζ in these cells.

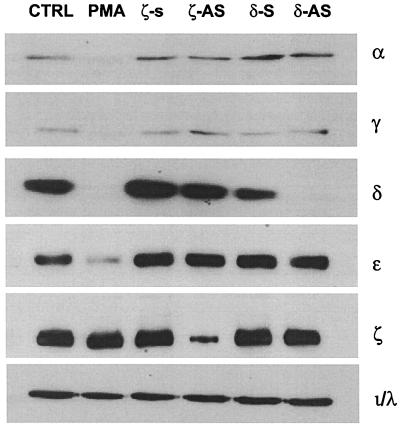

PKCζ antisense oligonucleotides are specific and do not block expression of other PKC isoforms.

To determine directly whether PKCζ mediates the activation of ERKs by EGF, we used antisense oligonucleotides (19, 33, 56). Initially, we determined whether the antisense oligonucleotides acted specifically to suppress PKCζ and not other PKC isoforms. H19-7 cells were transfected with phosphorothioate-modified antisense oligonucleotides directed against PKCζ or -δ (see Materials and Methods), and lysates were collected and analyzed for PKC expression by immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 3, treatment of cells with PKCζ antisense oligonucleotides decreased the amount of immunoreactive PKCζ by 76%, whereas other PKC isoforms were unaffected. In contrast, treatment of cells with PKCζ sense oligonucleotides had no effect on expression of any of the PKC isoforms. As a control, cells were also chronically treated with PMA, which selectively down regulates classical and novel PKC isoforms but not the atypical PKCs such as PKCζ or PKCι/λ (Fig. 3). Treatment of cells with antisense PKCδ oligonucleotides showed similar selectivity, decreasing expression of PKCδ by over 90% but leaving the other PKC isoforms unaffected. Taken together, these data show that treatment of H19-7 cells with antisense PKCζ oligonucleotides is an effective method for investigating the function of the PKCζ isoform.

FIG. 3.

Antisense oligonucleotides selectively suppress isoform-specific PKCs. H19-7 cells were pretreated with either sense (S) or antisense (AS) PKCζ- or δ phosphorothioate-modified oligonucleotides as described in Materials and Methods and then either untreated (CTRL) or stimulated with 800 nM PMA for 18 h. Cells were then lysed; the lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE (10% gel) and assayed for PKC expression by immunoblotting with anti-PKC antibodies.

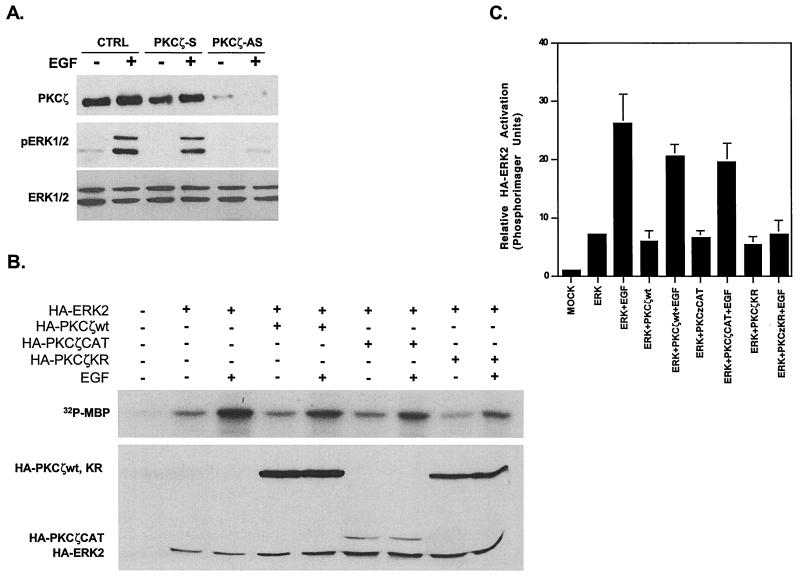

PKCζ mediates EGF-induced ERK activation in H19-7 cells.

To determine whether PKCζ plays a role in ERK induction by EGF, two approaches were used. First, H19-7 cells were transfected with PKCζ antisense or sense oligonucleotides, and ERK activation following EGF stimulation was determined by immunoblotting the cell extracts with anti-active MAPK phosphospecific antibody. This antibody recognizes the phosphorylated form of the conserved TEY motif within the activation loop in ERKs (11). Addition of the PKCζ antisense oligonucleotides decreased the levels of PKCζ expression and abrogated EGF-induced ERK activation, while control sense oligonucleotides had no effect (Fig. 4A). These results indicate that PKCζ expression is required for ERK activation by EGF.

FIG. 4.

PKCζ is required for EGF-induced ERK activation in H19-7 cells. (A) Antisense PKCζ oligonucleotides block PKCζ expression and ERK activation in H19-7 cells. Cells were pretreated with either sense (S) or antisense (AS) phosphorothioate-modified PKCζ oligonucleotides as described in Materials and Methods and then either untreated or stimulated with EGF (10 ng/ml) for 10 min. Cells were then lysed; the lysates resolved by SDS-PAGE (10% gel) and assayed for PKCζ expression by immunoblotting with anti-PKCζ antibody. Membranes were then stripped, and MAPK activation was assayed by immunoblotting with anti-phospho-ERK antibody. Finally, membranes were stripped again and assayed for ERK expression with anti-ERK antibodies. (B) PKCζKR abrogates EGF-induced HA-ERK2 activation. H19-7 cells were transfected with 10 μg of pcDNA3, 2 μg of HA-ERK2 plus 8 μg of pcDNA3, or 2 μg of HA-ERK2 plus 8 μg of HA-PKCζwt, -CAT, or -KR cDNA. Cells were then switched to N2 medium at 39°C and left untreated or stimulated with EGF (10 ng/ml) for 10 min. Following treatment, cells were lysed, and HA-tagged constructs were immunoprecipitated with HA.11 antibody. The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE (13% gel) and assayed for ERK activity using MBP as a substrate as described in Materials and Methods; 10 μM PKC peptide inhibitor was included in the kinase mixture. Membranes were then probed for HA-tagged proteins using rat 3F10 antibody. (C) Quantification of ERK activation. The amount of 32P incorporated into MBP was measured by PhosphorImager analysis and normalized to the amount of HA protein in each sample. The mock lane was arbitrarily set to 1. Data are the means ± standard deviations from three independent experiments.

As a complementary approach, cells were transfected with a kinase-inactive mutant of PKCζ (PKCδKR) to determine whether it acts as a dominant-negative inhibitor of ERK activation by EGF. Thus, HA-tagged PKCζ constructs (59) were cotransfected with HA-ERK2 into H19-7 cells, and the cells were either untreated or stimulated with EGF. Following stimulation, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were assayed for ERK kinase activity using MBP as a substrate. Since HA-PKCζ is also immunoprecipitated under these conditions, the PKCζ inhibitor peptide was also included in the kinase assay to suppress any MBP phosphorylation by PKCζ. Finally, the results of this experiment were confirmed using FLAG-tagged PKCζ (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 4B and C, EGF stimulation caused a threefold increase in normalized HA-ERK2 kinase activity relative to nonstimulated cells. Cotransfection with wild-type or the catalytic portion of PKCζ (PKCζwt or PKCζCAT) resulted in an approximately fourfold increase in EGF-induced HA-ERK2 activation compared to nonstimulated cells. Conversely, the kinase-dead PKCζKR mutant decreased the level of EGF-stimulated HA-ERK2 activation to 1.3-fold, suggesting that the kinase activity of PKCζ is required. Analysis of HA-ERK2 activation by Western blotting with anti-phospho-ERK yielded similar results (data not shown). These data confirm that activated PKCζ is an intermediate in the EGF-induced ERK activation pathway in H19-7 cells.

PKCζ is required for EGF-induced MEK activation.

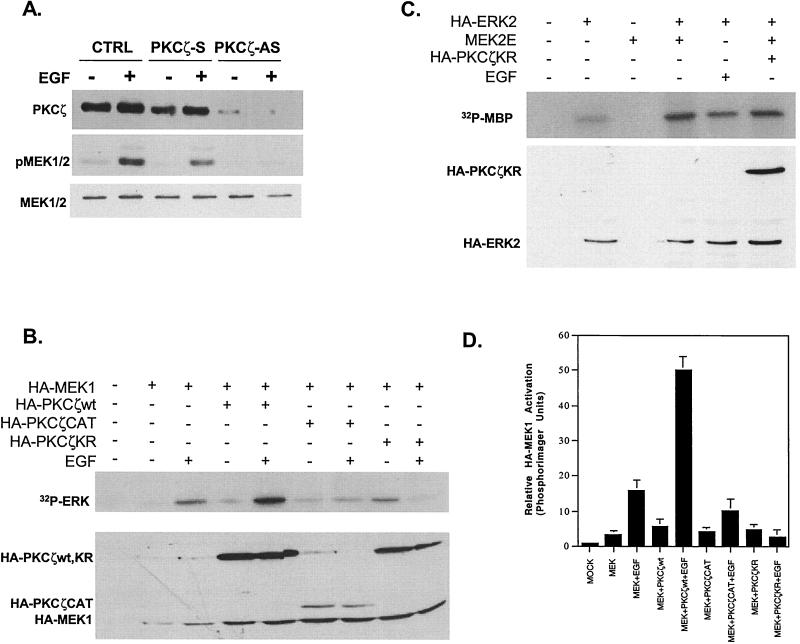

Since PKCζ mediates ERK activation, we initially determined whether PKCζ acts upstream of MEK. H19-7 cells were transfected with PKCζ antisense oligonucleotides, the cells were stimulated with EGF, and the cell extracts were immunoblotted with anti-phospho-MEK antibody to measure activated MEK as determined by phosphorylation of its activation loop. As shown in Fig. 5A, treatment of H19-7 cells with antisense but not sense PKCζ inhibited EGF-induced MEK activation, indicating that PKCζ acts upstream of MEK.

FIG. 5.

PKCζ is required for EGF-induced MEK activation. (A) Antisense PKCζ phosphorothioate-modified oligonucleotides block PKCζ expression and MEK activation in H19-7 cells. Cells were pretreated with either sense (S) or antisense (AS) PKCζ oligonucleotides as described in Materials and Methods and then either untreated or stimulated with EGF (10 ng/ml) for 10 min. Cells were then lysed; the lysates resolved by SDS-PAGE (10% gel) and assayed for PKCζ expression by immunoblotting with anti-PKCζ antibody. Membranes were then stripped, and MEK activation was assayed by immunoblotting with anti-phospho-MEK antibody. Finally, membranes were stripped again and assayed for MEK expression with anti-MEK antibodies. (B) PKCζwt enhances and PKCζKR abrogates EGF-induced HA-MEK1 activation. H19-7 cells were transfected with 10 μg of pcDNA3, 2 μg of HA-MEK1 plus 8 μg pcDNA3, or 2 μg of HA-MEK1 plus 8 μg of HA-PKCζwt, -CAT, or -KR cDNA. Cells were then switched to N2 medium at 39°C and left untreated or stimulated with EGF (10 ng/ml) for 10 min. Following treatment, cells were lysed, and HA-tagged constructs were immunoprecipitated with HA.11 antibody. The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE (10% gel) and assayed for MEK activity using kinase-dead ERK as a substrate as described in Materials and Methods; 10 μM PKC peptide inhibitor was included in the kinase mixture. Membranes were then probed for HA-tagged proteins using rat antibody 3F10. (C) PKCζ does not block activation of ERK by constitutively activated MEK. H19-7 cells were transfected with 10 μg of pcDNA3 (mock), 2 μg of HA-ERK2 plus 8 μg of pcDNA3, 2 μg of MEK2E (a constitutively active MEK) plus 8 μg of pcDNA3, 2 μg of HA-ERK2 plus 2 μg of MEK2E and 6 μg of pcDNA3, or 2 μg of HA-ERK2 plus 2 μg of MEK2E and 6 μg of HA-PKCζKR cDNA. Cells were then switched to N2 medium at 39°C and left untreated or stimulated with EGF (10 ng/ml) for 10 min. Following treatment, cells were lysed, and HA-tagged constructs were immunoprecipitated with HA.11 antibody. The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE (13% gel) and assayed for ERK activity using MBP as a substrate as described in Materials and Methods. (D) Quantification of MEK activation. The amount of 32P incorporated into ERK was measured by PhosphorImager analysis and normalized to the amount of HA protein in each sample. The mock lane was arbitrarily set to 1. Data are the means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments.

To confirm this result, MEK activity was also assayed directly. An HA-tagged MEK1 construct was cotransfected into H19-7 cells with HA-PKCζwt, PKCζKR, or PKCζCAT, and the cells were stimulated with EGF. Following immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody, HA-MEK1 activity was measured by in vitro kinase assay in the presence of the PKCζ inhibitor peptide (to inhibit any precipitated PKCζ activity) using kinase-inactive ERK(K52R) as the substrate. As above, the results of this experiment were confirmed using FLAG-tagged PKCζ (data not shown). EGF stimulated HA-MEK1 >5-fold relative to control, while cotransfection with the HA-PKCζwt enhanced HA-MEK1 activation an additional threefold, indicating that PKCζ can potentiate activation of MEK1 by EGF (Fig. 5B and D). Cotransfection with HA-PKCζCAT increased EGF-induced HA-MEK1 activity significantly less than the stimulation by PKCζwt. Finally, the kinase-inactive mutant HA-PKCζKR completely abrogated EGF-induced HA-MEK1 kinase activity. To confirm that PKCζ is not required downstream of MEK, the same PKCζ constructs were coexpressed with a constitutively active MEK (MEK2E) in H19-7 cells. In contrast to its effect on HA-MEK1, the kinase-inactive mutant PKCζKR did not block MEK2E-induced HA-ERK2 activation (Fig. 5C). Taken together with the antisense results, these data demonstrate that PKCζ mediates EGF-induced ERK activation upstream of MEK1.

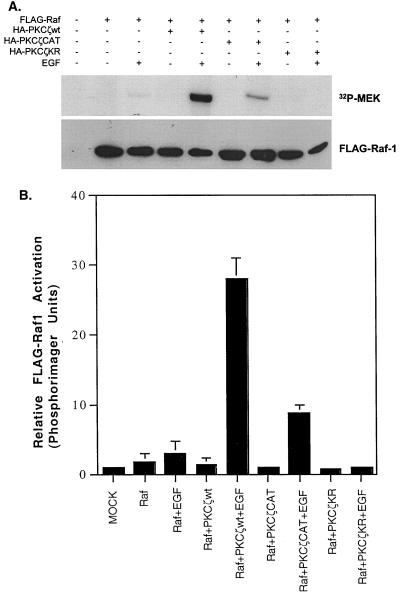

PKCζ potentiates EGF-induced Raf-1 activation.

To narrow down the potential targets of PKCζ action, we determined whether PKCζ activity potentiates or is required for stimulation of Raf-1 by EGF. A FLAG-tagged c-Raf-1 construct was cotransfected into H19-7 cells along with HA-PKCζwt, HA-PKCζCAT, or HA-PKCζKR, and the cells were stimulated with EGF. Following immunoprecipitation of FLAG-Raf-1 with anti-FLAG antibody, Raf-1 activity was assessed by in vitro kinase assay using inactive MEK as a substrate. As shown in Fig. 6, EGF is a weak activator of Raf-1 kinase activity in H19-7 cells. However, in EGF-treated cells cotransfected with HA-PKCζwt in addition to FLAG-Raf-1, Raf-1 kinase activity was enhanced 13-fold. Cotransfection of cells with HA-PKCζCAT in addition to FLAG-Raf-1 augmented EGF-induced Raf-1 kinase activity only fourfold. Consistent with the ERK and MEK1 results, expression of HA-PKCζKR completely abrogated FLAG-Raf-1 kinase activity. These data demonstrate that although EGF alone is a poor activator of Raf-1 kinase activity, the activation can be significantly enhanced by coexpression of PKCζ.

FIG. 6.

PKCζ enhances EGF-induced Raf-1 activation. (A) Effects of HA-PKCζ constructs on EGF-induced FLAG-Raf-1 activation. H19-7 cells were transfected with 10 μg of pcDNA3 (mock), 2 μg of FLAG-Raf-1 plus 8 μg of pcDNA3, or 2 μg of FLAG-Raf-1 plus 8 μg of HA-PKCζwt, -CAT, or -KR cDNA. Cells were then switched to N2 medium at 39°C and left untreated or stimulated with EGF (10 ng/ml) for 10 min. Following treatment, cells were lysed, and FLAG-tagged Raf-1 was immunoprecipitated with M5 antibody. The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE (10% gel) and assayed for Raf activity using kinase-dead MEK as a substrate as described in Materials and Methods. Membranes were then probed for FLAG-Raf-1 using M5 antibody. (B) Quantification of Raf-1 activation. The amount of 32P incorporated into MEK was measured by PhosphoImager analysis and normalized to the amount of FLAG-Raf protein in each sample. The mock lane was arbitrarily set to 1. Data are the means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments.

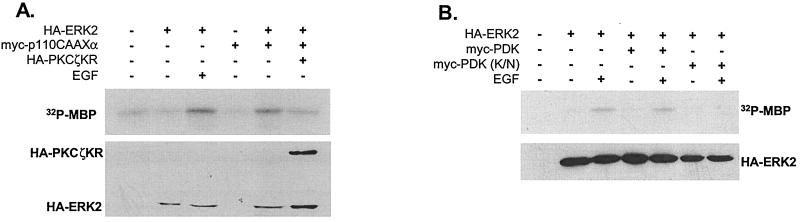

PDK1 is required for EGF-induced ERK activation.

Since EGF-induced ERK activation is PI-3 kinase and PKCζ dependent in H19-7 cells, we were interested in identifying other intermediates in this pathway. Although PKCζ can be activated by the products of PI-3 kinase (62), recent studies have shown that PKCζ is directly regulated by PDK1, which phosphorylates the Thr410 site within the activation loop (10, 39). As shown above, EGF-stimulated PKCζ is phosphorylated at this key site (Fig. 2B). Therefore, we determined whether PDK1 may be required for EGF-induced ERK activation in H19-7 cells. As shown in Fig. 7A, expression of a membrane-targeted, constitutively active PI-3 kinase (p110CAAXα) was sufficient to activate ERK, and this activation was blocked by PKCζKR suggesting that PKCζ is a downstream effector of PI-3 kinase in H19-7 cells. Consistent with the observations of Le Good et al. (39), a kinase-dead mutant of PDK1 (PDK K110N) blocked EGF-induced ERK activation (Fig. 7B). Together, these results demonstrate that the pathway controlling EGF-induced ERK activation in H19-7 cells involves PI-3 kinase, PDK1, and PKCζ.

FIG. 7.

PDK1 is required for EGF-induced ERK activation. (A) PKCζKR inhibits constitutively active PI-3 kinase-induced ERK activation. H19-7 cells were transfected with 10 μg of pcDNA3, 2 μg of HA-ERK2 plus 8 μg of pcDNA3, 2 μg of p110CAAXα (a constitutively active PI-3 kinase) plus 8 μg of pcDNA3, or 2 μg of HA-ERK2 plus 2 μg of p110CAAXα and 6 μg of pcDNA3 or HA-PKCζKR cDNA. Cells were then switched to N2 medium at 39°C and left untreated or stimulated with EGF (10 ng/ml) for 10 min. Following treatment, cells were lysed, and HA-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated with HA.11 antibody. The samples were resolved by SDS PAGE (13% gel) and assayed for ERK activity using MBP as a substrate as described in Materials and Methods. Membranes were then probed for HA-tagged proteins using rat antibody 3F10. (B) Kinase-dead PDK1 blocks EGF-induced ERK activation. H19-7 cells were transfected with 10 μg of pcDNA3, 2 μg of HA-ERK2 plus 8 μg of pcDNA3, 2 μg of HA-ERK2 plus 8 μg of myc-PDK1, or 2 μg of HA-ERK2 plus 8 μg of Myc-PDK1 K110N [myc-PDK(KN); kinase-dead PDK1] cDNA. Cells were then switched to N2 medium at 39°C and left untreated or stimulated with EGF (10 ng/ml) for 10 min. Following treatment, cells were lysed, and HA-ERK2 was immunoprecipitated with HA.11 antibody. The samples were resolved by SDS-PAGE (13% gel) and assayed for ERK activity using MBP as a substrate as described in Materials and Methods. Membranes were then probed for HA-ERK2 using rat 3F10 antibody.

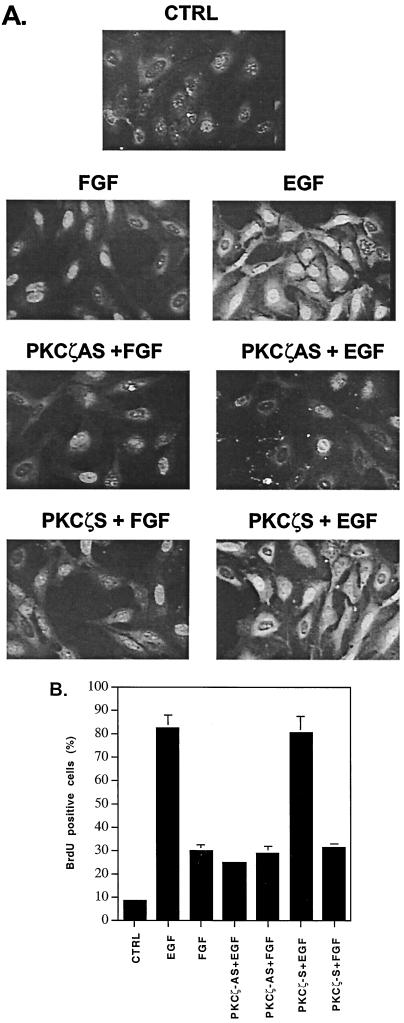

PKCζ is required for EGF-induced mitogenesis in H19-7 cells.

The ERK family of MAPK regulates cellular growth in a variety of tissues. At the permissive temperature (33°C), EGF induces a mitogenic response in H19-7 cells. Since PKCζ is a mediator of EGF-induced ERK activation, we determined whether EGF stimulation of DNA synthesis in these cells is dependent on PKCζ. To monitor DNA synthesis, we assayed for incorporation of the nucleoside analog BrdU into DNA by immunostaining with an anti-BrdU antibody. H19-7 cells were serum starved for 3 days at 33°C and then stimulated with EGF or FGF in the presence of BrdU for 24 h. As shown in Fig. 8, only 8% of the untreated control cells could be immunostained with an antibody to BrdU. FGF induced a fourfold increase (32%) in BrdU incorporation, while EGF caused 80% of the cells to incorporate BrdU, indicating that EGF is a more potent mitogen than FGF in H19-7 cells. To determine whether PKCζ mediates growth factor-stimulated DNA synthesis, almost 80% of the H19-7 cells were depleted of PKCζ by preincubation with PKCζ antisense oligonucleotides (Fig. 3). Under these conditions, only 25% of the cells incorporated BrdU following EGF stimulation. This number is probably an underestimate of the inhibition, since not all of the cells have taken up the antisense PKCζ oligonucleotides. No effect on DNA synthesis was observed when EGF-treated cells were preincubated with sense PKCζ or when FGF-treated cells were preincubated with antisense PKCζ oligonucleotides. These results indicate that PKCζ selectively mediates EGF-induced DNA synthesis.

FIG. 8.

PKCζ is required for EGF-induced DNA synthesis. (A) PKCζ antisense oligonucleotides block EGF-induced BrdU incorporation in H19-7 cells. Cells were pretreated with either sense (S) or antisense (AS) PKCζ oligonucleotides as described in Materials and Methods. H19-7 cells at 33°C were starved for 3 days in 0.1% FBS, treated with 10 μM BrdU–1 μM FrdU, and left untreated (CTRL) or stimulated with 10 ng of FGF or EGF per ml for 24 h. BrdU incorporation was detected by immunofluorescence as described in Materials and Methods. Magnification, ×400. (B) Quantification of BrdU staining. Cells with positive nuclear BrdU staining were scored in five randomly chosen fields. Data are the means ± standard deviations of three independent experiments.

Different PKC isoforms regulate ERK activation by EGF versus FGF in primary hippocampal neural cultures.

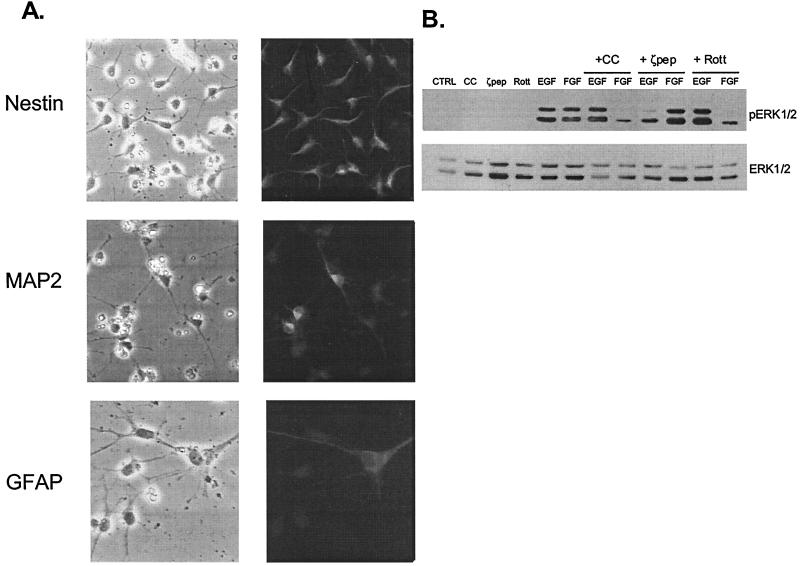

To determine whether the PKC-dependent growth factor signaling pathways identified in H19-7 cells are similarly activated in primary cells, we examined the response of E16 rat hippocampal cells to EGF versus FGF. Initially, the hippocampal cells were treated with FGF (10 ng/ml) in N2 medium for 4 days to expand the cultures and then incubated in N2 medium alone for 4 days to suppress mitogenesis. Immunostaining of the cells with antibodies for progenitor (nestin), neuronal (anti-MAP-2), or glial (anti-GFAP) markers indicated that 77% ± 0.2% of the cells expressed nestin, 17% ± 3.2% of the cells expressed MAP-2, and 2.7% ± 0.1% of the cells expressed GFAP (Fig. 9A). These results indicate that the hippocampal cells were primarily neural progenitor cells. Thus, these cells are similar to the H19-7 cells that express nestin and function as progenitors in vivo. Treatment with 10 ng of either FGF or EGF per ml for 10 min stimulated ERK activation, as shown by immunoblotting cell extracts with anti-phospho-ERK antibodies. Pretreatment with chelerythrine chloride, a selective inhibitor of the classical and novel PKCs, specifically inhibited FGF-induced ERK activation (Fig. 9B). However, pretreatment of cells with a myristoylated peptide inhibitor of PKCζ that is cell permeable (62) specifically suppressed ERK activation by EGF but had no effect on FGF-induced ERK activity. Conversely, pretreatment of cells with rottlerin, an inhibitor of PKCδ, decreased ERK activation by FGF but not EGF. Similarly, rottlerin selectively blocked ERK activation by FGF, and the PI-3 kinase inhibitor wortmannin specifically inhibited ERK activation by EGF in embryonic day 14.5 mouse cortical cultures (data not shown). These results indicate that EGF and FGF activate similar signaling cascades in primary as well as immortalized hippocampal neural cells.

FIG. 9.

PKCs are required for EGF- and FGF-induced ERK activation in primary rat E16 hippocampal cells. (A) Rat hippocampal E16 cells are neural precursors. Hippocampal cultures were fixed and prepared for immunofluorescence as described in Materials and Methods. The percentage of cells staining positive for nestin, MAP-2, or GFAP was determined as the mean ± standard deviation of three randomly chosen fields (see text). Magnification, ×400. (B) PKCζ and -δ mediate growth factor-specific ERK induction. Primary rat E16 hippocampal cells were dissected and cultured as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were pretreated with 1 μM chelerythrine chloride (CC), 30 μM myristolated PKCζ pseudosubstrate peptide (ζpep), or 5 μM rottlerin (Rott) for 1 h and then left untreated (CTRL) or stimulated with 10 ng of EGF or FGF per ml for 10 min. After lysis, equal protein aliquots were resolved by SDS-PAGE (10% gel) and then immunoblotted with anti-phospho-ERK antibody. Membranes were then stripped and reprobed with anti-ERK antibody.

DISCUSSION

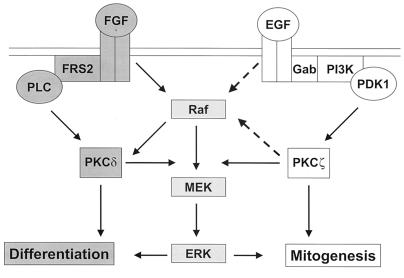

The results described here demonstrate that PKCζ is required for EGF-induced ERK activation and DNA synthesis in hippocampal H19-7 cells. The activation of PKCζ occurs by a PI-3 kinase and PDK-dependent pathway and is downstream of Ras (5, 8, 17). Furthermore, in primary E16 hippocampal cells, EGF-induced ERK activation also requires PKCζ, and FGF activation of ERK is dependent on PKCδ. These data complement our previous findings that PKCδ is required for FGF-induced ERK activation and can mediate neuritogenesis in H19-7 cells and PC12 cells. Taken together, these results demonstrate that different isoforms of PKC mediate growth factor-specific activation of ERK and lead to different biological outcomes within the same cell (Fig. 10).

FIG. 10.

ERK signaling cascade in H19-7 cells. Activation of ERK by neurogenic (FGF) and mitogenic (EGF) agents occurs by distinct but parallel PKC-dependent pathways. EGF-induced ERK activation in H19-7 cells, which may be mediated by Gab1 (22), is dependent on PI-3 kinase, PDK1, PKCζ, MEK, and possibly Raf. FGF activates PKCδ via a mechanism that could involve FRS2 and PLC (35, 48), leading to Raf/MEK activation.

PKCδ is often associated with a differentiation- or growth-suppressive function, whereas PKCζ has been implicated in cell metabolism and proliferation. For example, PKCδ promotes differentiation of myeloid progenitors into macrophages (44) and, when overexpressed, blocks growth in vascular smooth muscle, capillary endothelial, NIH 3T3, and CHO cells (26, 30, 43, 70). Src-mediated transformation in rat fibroblasts is blocked by PKCδ (40), and overexpression of PKCδ in the skin of transgenic mice prevents tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate-induced tumor promotion (50). On the other hand, PKCζ mediates Ras-independent activation of ERK by the Gi protein-coupled LPS receptor (63) as well as EGF-induced p70S6K activation (51). Sajan et al. (52) recently showed a requirement for PKCζ and PDK1 in insulin-induced activation of ERK in rat adipocytes. Insulin-stimulated glucose transport has been reported to be dependent on PKCζ (2, 61), and adenoviral delivery of recombinant human PKCζ into rat skeletal muscle stimulates glucose transport activity (20). PKCζ has also been found to activate the NF-κB/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) survival pathway in both cell lines (6, 19, 23, 38, 53, 60, 69) and in primary endothelial cells (1). Thus, recent work from several labs has suggested an important role for both PKCδ and PKCζ in a variety of cellular signaling pathways.

In contrast to many previous studies, we have used multiple approaches to demonstrate a specific role for PKCδ and PKCζ in growth factor signaling. While the dominant-negative mutant of PKCζ gave consistent results and has been used previously, this approach is not sufficient to implicate a particular isoform since various PKC dominant-negative mutants inhibit other members of the PKC family (reference 27 and data not shown). Peptides derived from the pseudosubstrate regions of particular PKC isoforms and chemical inhibitors that have 10- to 100-fold selectivity for a particular isoform such as rottlerin are very powerful tools. Perhaps the most convincing approach involves the use of antisense oligonucleotides (33, 56). Taken together, these methods provide strong evidence for a selective mobilization of different PKC isoforms by growth factors.

The mechanism by which these differential cascades are initiated is not entirely clear. Both the EGF and FGF receptors are associated through their juxtamembrane domains with distinct docking proteins, termed Gab1 and FRS2, respectively, and it is likely that the signaling molecules recruited to the receptors via these adapter proteins play an important role in initiating the specific cascades. In the case of FGF, receptor stimulation leads to complex formation between FRS2 and a variety of signaling molecules including the adapter Grb2, the Ras activator Sos, and the Shp2 tyrosine phosphatase (35). This complex has been implicated in the subsequent activation of MAPK and differentiation of PC12 cells (29). Gab1 has been found to similarly mediate EGF signaling (31). Although PKCδ (39) and PKCζ (10, 39) have both been shown to be activated by a PI-3 kinase- and PDK1-dependent pathway in some cells, our results suggest that this pathway is selectively activated by EGF but not FGF in neuronal cells. The primary target of PKCζ activation could be either Raf or MEK. Surprisingly, although overexpression of PKCζ can potentiate Raf activation by EGF, EGF barely stimulates Raf-1 in cells expressing only endogenous PKCζ. This result suggests that under physiological conditions, EGF activates the MEK/ERK cascade by a Raf-independent mechanism, and the potentiation of Raf is an artifact of PKCζ overexpression. Thus, the primary site of PKCζ action, like that of PKCδ (13), could be MEK rather than Raf. This possibility is consistent with previous studies indicating that the only PKC shown to activate MEK directly is PKCζ, and this signaling pathway is Raf independent (55). Thus, PKCs may modulate the ERK pathway by Raf-1-independent as well as -dependent pathways.

The results that we obtained suggest that the activation of ERKs by PKCζ is subject to a number of regulatory mechanisms. In several of our experiments, expression of exogenous PKCζwt was significantly more effective at activating ERK than the catalytically active form of PKCζ. One explanation for these results is that the N-terminal regulatory domain of PKCζ is required for maximal stimulation of Raf. This possibility is supported by a recent finding that the 14-3-3 site in the regulatory domain of PKCζ potentiates binding of PKCζ to Raf-1 (65). In other experiments, differences were observed in the ability of coexpressed PKCζwt to activate exogenous Raf versus exogenous ERK. There are several possible explanations for these results. Perhaps only the endogenous PKCζ is able to activate ERK. However, it is more likely that the lack of stimulation of the downstream exogenously expressed ERK is due to a limitation in the amount of endogenous upstream activators of ERK. It has recently been shown that synergistic activation of exogenously expressed JNK requires coexpression of the upstream activators MEK kinase 2 and JNK kinase 2 (9). Thus, formation of a similar complex between Raf, MEK, ERK, and PKCζwt may be required to maximally activate ERK.

The specific mechanisms by which PKC isoforms mediate growth factor activation of ERKs appear to be tissue specific. Phorbol ester-sensitive PKCs are required for EGF stimulation of Raf in NIH 3T3 and COS cells (7), and FGF stimulation of ERKs is independent of PKCδ in NIH 3T3 cells (13). In contrast, FGF requires PKCδ downstream of Raf but upstream of MEK in both H19-7 and PC12 cells (13). Similar cascades were observed in primary neuronal cells, although in these cells FGF can act as both a mitogen and a neurogenic factor (67). Thus, studies with embryonal cortical and hippocampal cultures from both mice and rats indicated that EGF activation of ERKs was suppressed by PI-3 kinase and PKCζ inhibitors, and FGF activation of ERKs and MEKs was suppressed by rottlerin and inhibitors of the novel PKCs (see Results; data not shown). Presumably, in different cell types, other modulating factors reflecting different intracellular environments act in conjunction with the specific PKC isoforms to determine the final biological outcome of growth factor stimulation.

The mechanism by which PKCs regulate MEK activation is the subject of current investigation. In one possible mechanism by which PKCδ might activate MEK, at PKC acts as a scaffold to bring a multiprotein complex together in order to mediate efficient transduction of the signal down the cascade. A number of scaffolding proteins in the MAPK cascade have now been identified, including MEK partner 1 (54), JNK-interacting protein 1 (73), and JNK/stress-activated protein kinase-associated protein 1 (32). An alternative mechanism is inactivation of an inhibitor acting on one of the intermediates in the ERK cascade. A primary candidate is the newly identified Raf kinase inhibitor protein (74). In either case, PKC kinase activity appears to be required, since the kinase-inactive mutant blocked PKC function. Finally, similar to the action of PAK1, PKC might directly phosphorylate and potentiate the activity of MEK (25). At least one group showed that LPS-stimulated PKCζ can phosphorylate MEK in vitro (45). In contrast, several groups have commented that PKCζ phosphorylates MEK weakly if at all compared to its ability to phosphorylate Raf (34, 55, 66). Further studies should resolve these possibilities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Matthew Saelzler for expert technical assistance and Jane Booker for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript. We also thank A. Toker for generously providing plasmids and antibodies.

This work was supported by National Institute of Health grants NS33858 (M.R.R.) and CA26056 (J.-W.S. and I.B.W.), Pharmacological Sciences Training grant 5 T32 GM 07151-24 (K.C.C.), a gift from the Cornelius Crane Trust for Eczema Research (M.R.R.), and an award from the National Foundation for Cancer Research (I.B.W.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Anrather J, Csizmadia V, Soares M P, Winkler H. Regulation of NF-kappaB RelA phosphorylation and transcriptional activity by p21(ras) and protein kinase Czeta in primary endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:13594–13603. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandyopadhyay G, Standaert M L, Sajan M P, Karnitz L M, Cong L, Quon M J, Farese R V. Dependence of insulin-stimulated glucose transporter 4 translocation on 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 and its target threonine-410 in the activation loop of protein kinase C-zeta. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:1766–1772. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.10.0364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berra E, Diaz-Meco M T, Dominguez I, Municio M M, Sanz L, Lozano J, Chapkin R S, Moscat J. Protein kinase C zeta isoform is critical for mitogenic signal transduction. Cell. 1993;74:555–563. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80056-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berra E, Diaz-Meco M T, Lozano J, Frutos S, Municio M M, Sanchez P, Sanz L, Moscat J. Evidence for a role of MEK and MAPK during signal transduction by protein kinase C zeta. EMBO J. 1995;14:6157–6163. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00306.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjorkoy G, Overvatn A, Diaz-Meco M T, Moscat J, Johansen T. Evidence for a bifurcation of the mitogenic signaling pathway activated by Ras and phosphatidylcholine-hydrolyzing phospholipase C. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21299–21306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.21299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjorkoy G, Perander M, Overvatn A, Johansen T. Reversion of Ras- and phosphatidylcholine-hydrolyzing phospholipase C-mediated transformation of NIH 3T3 cells by a dominant interfering mutant of protein kinase C lambda is accompanied by the loss of constitutive nuclear mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11557–11565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai H, Smola U, Wixler V, Eisenmann-Tappe I, Diaz-Meco M T, Moscat J, Rapp U, Cooper G M. Role of diacylglycerol-regulated protein kinase C isotypes in growth factor activation of the Raf-1 protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:732–741. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.2.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chao T-S O, Abe M, Hershenson M B, Gomes I, Rosner M R. Src tyrosine kinase mediates stimulation of Raf-1 and mitogen-activated protein kinase by the tumor promoter thapsigargin. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3168–3173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng J, Yang J, Xia Y, Karin M, Su B. Synergistic interaction of MEK kinase 2, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) kinase 2, and JNK1 results in efficient and specific JNK1 activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:2334–2342. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.7.2334-2342.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou M M, Hou W, Johnson J, Graham L K, Lee M H, Chen C S, Newton A C, Schaffhausen B S, Toker A. Regulation of protein kinase C zeta by PI 3-kinase and PDK-1. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1069–1077. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cobb M H, Xu S, Cheng M, Ebert D, Robbins D, Goldsmith E, Robinson M. Structural analysis of the MAP kinase ERK2 and studies of MAP kinase regulatory pathways. Adv Pharmacol. 1996;36:49–65. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60576-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook S J, Aziz N, McMahon M. The repertoire of Fos and Jun proteins expressed during the G1 phase of the cell cycle is determined by the duration of mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:330–341. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corbit K C, Foster D A, Rosner M R. Protein kinase Cδ mediates neurogenic but not mitogenic activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in neuronal cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4209–4218. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cross M J, Stewart A, Hodgkin M N, Kerr D J, Wakelam M J. Wortmannin and its structural analogue demethoxyviridin inhibit stimulated phospholipase A2 activity in Swiss 3T3 cells. Wortmannin is not a specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25352–25355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dekker L V, Parker P J. Protein kinase C—a question of specificity. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:73–77. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diaz-Meco M T, Dominguez I, Sanz L, Dent P, Lozano J, Municio M M, Berra E, Hay R T, Sturgill T W, Moscat J. Zeta PKC induces phosphorylation and inactivation of I kappa B-alpha in vitro. EMBO J. 1994;13:2842–2848. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diaz-Meco M T, Lozano J, Municio M M, Berra E, Frutos S, Sanz L, Moscat J. Evidence for the in vitro and in vivo interaction of Ras with protein kinase C zeta. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:31706–31710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diaz-Meco M T, Municio M M, Frutos S, Sanchez P, Lozano J, Sanz L, Moscat J. The product of par-4, a gene induced during apoptosis, interacts selectively with the atypical isoforms of protein kinase C. Cell. 1996;86:777–786. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80152-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dominguez I, Diaz-Meco M T, Municio M M, Berra E, Garcia de Herreros A, Cornet M E, Sanz L, Moscat J. Evidence for a role of protein kinase C zeta subspecies in maturation of Xenopus laevis oocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:3776–3783. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.9.3776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Etgen G J, Valasek K M, Broderick C L, Miller A R. In vivo adenoviral delivery of recombinant human protein kinase C-zeta stimulates glucose transport activity in rat skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22139–22142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eves E M, Tucker M S, Roback J D, Downen M, Rosner M R, Wainer B H. Immortal rat hippocampal cell lines exhibit neuronal and glial lineages and neurotrophin gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4373–4377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleming I, MacKenzie S J, Vernon R G, Anderson N G, Houslay M D, Kilgour E. Protein kinase C isoforms play differential roles in the regulation of adipocyte differentiation. Biochem J. 1998;333:719–727. doi: 10.1042/bj3330719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Folgueira L, McElhinny J A, Bren G D, MacMorran W S, Diaz-Meco M T, Moscat J, Paya C V. Protein kinase C-ζ mediates NF-κB activation in human immunodeficiency virus-infected monocytes. J Virol. 1996;70:223–231. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.223-231.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forsberg-Nilsson K, Behar T N, Afrakhte M, Barker J L, McKay R D. Platelet-derived growth factor induces chemotaxis of neuroepithelial stem cells. J Neurosci Res. 1998;53:521–530. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980901)53:5<521::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frost J A, Steen H, Shapiro P, Lewis T, Ahn N, Shaw P E, Cobb M H. Cross-cascade activation of ERKs and ternary complex factors by Rho family proteins. EMBO J. 1997;16:6426–6438. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.21.6426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fukumoto S, Nishizawa Y, Hosoi M, Koyama H, Yamakawa K, Ohno S, Morii H. Protein kinase C delta inhibits the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells by suppressing G1 cyclin expression. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13816–13822. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Paramio P, Cabrerizo Y, Bornancin F, Parker P J. The broad specificity of dominant inhibitory protein kinase C mutants infers a common step in phosphorylation. Biochem J. 1998;333:631–636. doi: 10.1042/bj3330631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomez J, Martinez C, Garcia A, Rebollo A. Association of phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase to protein kinase C zeta during interleukin-2 stimulation. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1781–1787. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hadari Y R, Kouhara H, Lax I, Schlessinger J. Binding of Shp2 tyrosine phosphatase to FRS2 is essential for fibroblast growth factor-induced PC12 cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3966–3973. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrington E O, Loffler J, Nelson P R, Kent K C, Simons M, Ware J A. Enhancement of migration by protein kinase Calpha and inhibition of proliferation and cell cycle progression by protein kinase Cdelta in capillary endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7390–7397. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holgado-Madruga M, Emlet D R, Moscatello D K, Godwin A K, Wong A J. A Grb2-associated docking protein in EGF- and insulin-receptor signalling. Nature. 1996;379:560–564. doi: 10.1038/379560a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ito M, Yoshioka K, Akechi M, Yamashita S, Takamatsu N, Sugiyama K, Hibi M, Nakabeppu Y, Shiba T, Yamamoto K I. JSAP1, a novel Jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK)-binding protein that functions as a Scaffold factor in the JNK signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7539–7548. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jobbagy Z, Olah Z, Petrovics G, Eiden M V, Leverett B D, Dean N M, Anderson W B. Up-regulation of the Pit-2 phosphate transporter/retrovirus receptor by protein kinase C epsilon. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:7067–7071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kieser A, Seitz T, Adler H S, Coffer P, Kremmer E, Crespo P, Gutkind J S, Henderson D W, Mushinski J F, Kolch W, Mischak H. Protein kinase C-zeta reverts v-raf transformation of NIH-3T3 cells. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1455–1466. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.12.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kouhara H, Hadari Y R, Spivak-Kroizman T, Schilling J, Bar-Sagi D, Lax I, Schlessinger J. A lipid-anchored Grb2-binding protein that links FGF-receptor activation to the Ras/MAPK signaling pathway. Cell. 1997;89:693–702. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80252-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuo W-L, Abe M, Rhee J, Eves E M, McCarthy S A, Yan M, Templeton D J, McMahon M, Rosner M R. Raf, but not MEK or ERK, is sufficient for differentiation of hippocampal neuronal cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1458–1470. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuo W-L, Chung K-C, Rosner M R. Differentiation of central nervous system neuronal cells by fibroblast-derived growth factor requires at least two signaling pathways: roles for Ras and Src. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4633–4643. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lallena M J, Diaz-Meco M T, Bren G, Paya C V, Moscat J. Activation of IκB kinase beta by protein kinase C isoforms. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2180–2188. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Le Good J A, Ziegler W H, Parekh D B, Alessi D R, Cohen P, Parker P J. Protein kinase C isotypes controlled by phosphoinositide 3-kinase through the protein kinase PDK1. Science. 1998;281:2042–2045. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu Z, Hornia A, Jiang Y W, Zang Q, Ohno S, Foster D A. Tumor promotion by depleting cells of protein kinase C delta. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3418–3428. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.6.3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacKenzie S, Fleming I, Houslay M D, Anderson N G, Kilgour E. Growth hormone and phorbol esters require specific protein kinase C isoforms to activate mitogen-activated protein kinases in 3T3-F442A cells. Biochem J. 1997;324:159–165. doi: 10.1042/bj3240159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mendez R, Kollmorgen G, White M F, Rhoads R E. Requirement of protein kinase C zeta for stimulation of protein synthesis by insulin. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5184–5192. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mischak H, Goodnight J A, Kolch W, Martiny-Baron G, Schaechtle C, Kazanietz M G, Blumberg P M, Pierce J H, Mushinski J F. Overexpression of protein kinase C-delta and -epsilon in NIH 3T3 cells induces opposite effects on growth, morphology, anchorage dependence, and tumorigenicity. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:6090–6096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mischak H, Pierce J H, Goodnight J, Kazanietz M G, Blumberg P M, Mushinski J F. Phorbol ester-induced myeloid differentiation is mediated by protein kinase C-alpha and -delta and not by protein kinase C-beta II, -epsilon, -zeta, and -eta. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20110–20115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Monick M M, Carter A B, Gudmundsson G, Mallampalli R, Powers L S, Hunninghake G W. A phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C regulates activation of p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinases in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human alveolar macrophages. J Immunol. 1999;162:3005–3012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murray N R, Fields A P. Atypical protein kinase C iota protects human leukemia cells against drug-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27521–27524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Novelli A, Reilly J A, Lysko P G, Henneberry R C. Glutamate becomes neurotoxic via the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor when intracellular energy levels are reduced. Brain Res. 1988;451:205–212. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90765-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Obermeier A, Bradshaw R A, Seedorf K, Choidas A, Schlessinger J, Ullrich A. Neuronal differentiation signals are controlled by nerve growth factor receptor/Trk binding sites for SHC and PLC gamma. EMBO J. 1994;13:1585–1590. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06421.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pumiglia K M, Decker S J. Cell cycle arrest mediated by the MEK/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:448–452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reddig P J, Dreckschmidt N E, Ahrens H, Simsiman R, Tseng C P, Zou J, Oberley T D, Verma A K. Transgenic mice overexpressing protein kinase Cdelta in the epidermis are resistant to skin tumor promotion by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5710–5718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Romanelli A, Martin K A, Toker A, Blenis J. p70 S6 kinase is regulated by protein kinase Cζ and participates in a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-regulated signalling complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2921–2928. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sajan M P, Standaert M L, Bandyopadhyay G, Quon M J, Burke T R, Jr, Farese R V. Protein kinase C-zeta and phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 are required for insulin-induced activation of ERK in rat adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30495–30500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sanz L, Sanchez P, Lallena M J, Diaz-Meco M T, Moscat J. The interaction of p62 with RIP links the atypical PKCs to NF-kappaB activation. EMBO J. 1999;18:3044–3053. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.3044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schaeffer H J, Catling A D, Eblen S T, Collier L S, Krauss A, Weber M J. MP1: a MEK binding partner that enhances enzymatic activation of the MAP kinase cascade. Science. 1998;281:1668–1671. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5383.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schonwasser D C, Marais R M, Marshall C J, Parker P J. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway by conventional, novel, and atypical protein kinase C isotypes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:790–798. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shih S C, Mullen A, Abrams K, Mukhopadhyay D, Claffey K P. Role of protein kinase C isoforms in phorbol ester-induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression in human glioblastoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15407–15414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shihabuddin L S, Hertz J A, Holets V R, Whittemore S R. The adult CNS retains the potential to direct region-specific differentiation of a transplanted neuronal precursor cell line. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6666–6678. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06666.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith M K, Colbran R J, Soderling T R. Specificities of autoinhibitory domain peptides for four protein kinases. Implications for intact cell studies of protein kinase function. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1837–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Soh J W, Lee E H, Prywes R, Weinstein I B. Novel roles of specific isoforms of protein kinase C in activation of the c-fos serum response element. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1313–1324. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sontag E, Sontag J M, Garcia A. Protein phosphatase 2A is a critical regulator of protein kinase C zeta signaling targeted by SV40 small t to promote cell growth and NF-kappaB activation. EMBO J. 1997;16:5662–5671. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Standaert M L, Bandyopadhyay G, Sajan M P, Cong L, Quon M J, Farese R V. Okadaic acid activates atypical protein kinase C (zeta/lambda) in rat and 3T3/L1 adipocytes. An apparent requirement for activation of Glut4 translocation and glucose transport. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14074–14078. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Standaert M L, Galloway L, Karnam P, Bandyopadhyay G, Moscat J, Farese R V. Protein kinase C-zeta as a downstream effector of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase during insulin stimulation in rat adipocytes. Potential role in glucose transport. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30075–30082. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takeda H, Matozaki T, Takada T, Noguchi T, Yamao T, Tsuda M, Ochi F, Fukunaga K, Inagaki K, Kasuga M. PI 3-kinase gamma and protein kinase C-zeta mediate RAS-independent activation of MAP kinase by a Gi protein-coupled receptor. EMBO J. 1999;18:386–395. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.2.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tian Y, Smith R D, Balla T, Catt K J. Angiotensin II activates mitogen-activated protein kinase via protein kinase C and Ras/Raf-1 kinase in bovine adrenal glomerulosa cells. Endocrinology. 1998;139:1801–1809. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.4.5865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Van Der Hoeven P C, Van Der Wal J C, Ruurs P, Van Dijk M C, Van Blitterswijk J. 14-3-3 isotypes facilitate coupling of protein kinase C-zeta to Raf-1: negative regulation by 14-3-3 phosphorylation. Biochem J. 2000;345:297–306. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3450297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Dijk M C, Hilkmann H, van Blitterswijk W J. Platelet-derived growth factor activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase depends on the sequential activation of phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C, protein kinase C-zeta and Raf-1. Biochem J. 1997;325:303–307. doi: 10.1042/bj3250303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vicario-Abejón C, Johe K K, Hazel T G, Collazo D, McKay R D G. Functions of basic fibroblast growth factor and neurotrophins in the differentiation of hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1995;15:105–114. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vlahos C J, Matter W F, Hui K Y, Brown R F. A specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002) J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5241–5248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang Y M, Seibenhener M L, Vandenplas M L, Wooten M W. Atypical PKC zeta is activated by ceramide, resulting in coactivation of NF-kappaB/JNK kinase and cell survival. J Neurosci Res. 1999;55:293–302. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19990201)55:3<293::AID-JNR4>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Watanabe T, Ono Y, Taniyama Y, Hazama K, Igarashi K, Ogita K, Kikkawa U, Nishizuka Y. Cell division arrest induced by phorbol ester in CHO cells overexpressing protein kinase C-delta subspecies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10159–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Woods D, Parry D, Cherwinski H, Bosch E, Lees E, McMahon M. Raf-induced proliferation or cell cycle arrest is determined by the level of Raf activity with arrest mediated by p21Cip1. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5598–5611. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wooten M W, Zhou G, Seibenhener M L, Coleman E S. A role for zeta protein kinase C in nerve growth factor-induced differentiation of PC12 cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:395–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yasuda J, Whitmarsh A J, Cavanagh J, Sharma M, Davis R J. The JIP group of mitogen-activated protein kinase scaffold proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7245–7254. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yeung K, Seitz T, Li S, Janosch P, McFerran B, Kaiser C, Fee F, Katsanakis K D, Rose D W, Mischak H, Sedivy J M, Kolch W. Suppression of Raf-1 kinase activity and MAP kinase signalling by RKIP. Nature. 1999;401:173–177. doi: 10.1038/43686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhu J, Woods D, McMahon M, Bishop J M. Senescence of human fibroblasts induced by oncogenic Raf. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2997–3007. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]