Abstract

Background

Vaccination is the primary strategy to reduce influenza burden. Influenza vaccine effectiveness (VE) can vary annually depending on circulating strains.

Methods

We used a test-negative case-control study design to estimate influenza VE against laboratory-confirmed influenza-related hospitalizations among children (aged 6 months–17 years) across 5 influenza seasons in Atlanta, Georgia, from 2012–2013 to 2016–2017. Influenza-positive cases were randomly matched to test-negative controls based on age and influenza season in a 1:1 ratio. We used logistic regression models to compare odds ratios (ORs) of vaccination in cases to controls. We calculated VE as [100% × (1 – adjusted OR)] and computed 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around the estimates.

Results

We identified 14 596 hospitalizations of children who were tested for influenza using the multiplex respiratory molecular panel; influenza infection was detected in 1017 (7.0%). After exclusions, we included 512 influenza-positive cases and 512 influenza-negative controls. The median age was 5.9 years (interquartile range, 2.7–10.3), 497 (48.5%) were female, 567 (55.4%) were non-Hispanic Black, and 654 (63.9%) children were unvaccinated. Influenza A accounted for 370 (72.3%) of 512 cases and predominated during all 5 seasons. The adjusted VE against influenza-related hospitalizations during 2012–2013 to 2016–2017 was 51.3% (95% CI, 34.8% to 63.6%) and varied by season. Influenza VE was 54.7% (95% CI, 37.4% to 67.3%) for influenza A and 37.1% (95% CI, 2.3% to 59.5%) for influenza B.

Conclusions

Influenza vaccination decreased the risk of influenza-related pediatric hospitalizations by >50% across 5 influenza seasons.

Keywords: adolescent, immunization, influenza vaccine effectiveness, pediatric

A test-negative case-control study estimated inactivated influenza vaccine effectiveness after adjustment at 51.3% (95% confidence interval, 34.8% to 63.6%) against laboratory-confirmed influenza-related hospitalizations among children across 5 influenza seasons in Atlanta, Georgia.

Influenza is responsible for morbidity and occasional mortality in children, particularly those aged <5 years [1]. Influenza vaccination can prevent influenza infection and its complications and is recommended for children aged ≥6 months [2]. The effectiveness of influenza vaccination in preventing influenza-like illness (ILI) varies substantially from year to year. Factors that can affect influenza vaccine effectiveness (VE) include the antigenic match between vaccine strain and circulating influenza strains and the timing of seasonal influenza vaccination due to potential intraseason waning of influenza VE [3-7]. Other factors, such as manufacturing, distribution-related events, and vaccine stability, have been thought to contribute to the poor VE seen with live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) against A(H1N1)pdm09 in the 2013–2014 through 2015–2016 influenza seasons [8-10]. Even when influenza vaccination fails to prevent influenza-related hospitalization, it may modify influenza severity with impact in some seasons on the duration of hospitalization, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and death [11, 12].

Although influenza VE in prevention of ILI is determined yearly, data about the impact of influenza vaccination on prevention of influenza-related hospitalization or attenuation of outcomes are very limited in both adults and children [13-18]. To help address this knowledge gap, we conducted a retrospective, observational study using a test-negative case-control design of children hospitalized at 2 pediatric hospitals in Atlanta, Georgia, between 1 October 2012 and 30 April 2017. The primary endpoint was inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) VE in prevention of pediatric hospitalizations.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective test-negative case-control study including children aged 6 months to <18 years admitted to the Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta (CHOA), Georgia, during the 2012–2013 to 2016–2017 influenza seasons. Each influenza season was defined as the period from 1 October to 30 April of the subsequent year. CHOA is one of the largest pediatric healthcare systems in the country, with >200 000 emergency department visits and >25 000 inpatient hospital admissions each year. We restricted our study to those children residing in Health District 3 of Georgia (Fulton, DeKalb, Gwinnett, Cobb, Douglas, Clayton, Rockdale, and Newton counties) to ensure patients were not referred only for critical illness. The study was reviewed and approved by the CHOA Institutional Review Board.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Eligible patients were children aged 6 months to <18 years at admission with acute respiratory illness (ARI) at the time of the influenza testing based on ≥1 of the following symptoms: nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, sore throat, hoarseness, cough, sputum production, dyspnea, wheezing; or an admitting diagnosis suggestive of ARI (pneumonia, upper respiratory infection, bronchitis, lower respiratory infection, bronchiolitis, influenza, cough, asthma, viral illness, respiratory distress, respiratory failure); or congestive heart failure exacerbation. Patients were excluded if they did not have documented symptoms, if they were vaccinated <14 days prior to testing, if they had missing immunization records, if they had taken influenza antiviral medications in the 7 days prior to testing, or if they had repeat encounters where the same pathogen was detected within 30 days. Cases were children who met the inclusion criteria and tested positive for influenza, and controls were defined as children who met inclusion criteria but tested negative for influenza using a multiplex respiratory molecular panel during the same influenza season. Children aged <2 years were matched by age in months with 6-month intervals. Older children were matched by year of age.

Data Collection

Patients tested for respiratory pathogens using a multiplex respiratory molecular panel (BioFire FilmArray, bioMérieux, France) within the first 3 days of admission were retrospectively identified. A comprehensive chart review was conducted using a standardized case report form built into REDCap [19] to capture demographic and clinical features (see Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 1).

Influenza vaccination information was collected for each patient using Georgia Registry of Immunization Transactions and Services (GRITS) records. Under the Georgia Immunization Registry Law, all immunizations given in the State of Georgia are required to be entered into this database, which has been shown to accurately capture administered vaccines [20]. Complete vs partial influenza vaccination status was defined based on Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommendations (see Supplementary Methods). Children aged <9 years who received only 1 vaccine dose in the current season (and no known prior vaccine doses) and children who were vaccinated <14 days before disease onset were considered partially vaccinated.

Statistical Analyses

VE was assessed using a test-negative case-control design overall and during each season of the 2012–2013 through 2016–2017 influenza seasons using 1 or more current season influenza vaccine doses as the main exposure. Cases and controls were matched on age and influenza season with a 1:1 ratio. Influenza VE was estimated as [100% × (1 – adjusted OR)], with OR being the odds of influenza vaccination among influenza-positive cases divided by the odds of vaccination among influenza-negative controls. Due to the insufficient number of LAIV vaccinations, we limited our estimates of VE to IIV, resulting in an analyzable population of 490 cases and 490 controls receiving either IIV or no vaccination. Influenza VE was estimated for overall and subtypes A and B but not for other subtypes.

We used frequencies and percentages or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for categorical or continuous variables, respectively. Demographic and clinical characteristics and other potential confounders were compared between cases and controls and between vaccinated and unvaccinated participants using the Fisher exact test for categorical characteristics and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous characteristics. Adjusted ORs with Wald 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using unconditional multiple logistic regression models, which are appropriate for populations matched on basic demographic variables [21]. We considered P values of < .05 and 95% CI, excluding 1, as statistically significant. Model covariates included clinically significant features and potential confounders identified in bivariate analyses with either case status or vaccination status at a significance level of 0.05 (see Supplementary Methods).

Sensitivity and Subgroup Analyses

Sensitivity analyses were conducted by applying the final multiple logistic regression model to a redefined study cohort. Subgroup analyses were conducted by introducing a stratifying variable into the model as an independent covariate and in an interaction term with case status. Statistically significant differences in the VE estimates across strata were identified using the 2-tailed P value at a significance level of < .05 of this interaction term. Sensitivity and subgroup analyses were prespecified (see Supplementary Methods and Tables 2 and 3).

In addition, we conducted a sham analysis estimating influenza VE in a cohort of human metapneumovirus (HMPV)-positive/flu-negative cases and HMPV-negative/flu-negative controls to evaluate for residual confounding and confirm lack of association between flu vaccination and HMPV infection.

RESULTS

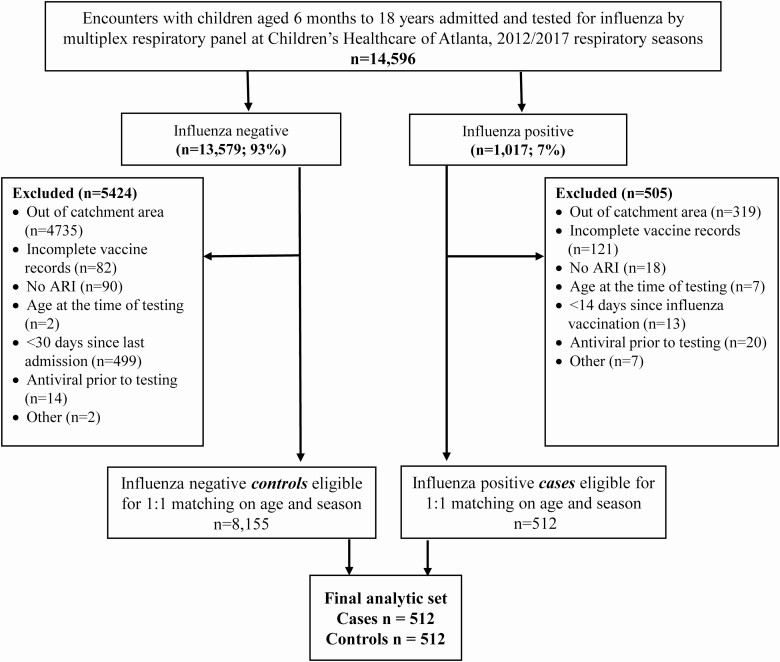

We identified 14 596 hospitalizations for children who were tested for influenza using a multiplex respiratory molecular panel during the 2012–2013 to 2016–2017 influenza seasons (Figure 1). After exclusions, we included 512 influenza-positive cases and 512 influenza-negative controls in the entire cohort. The median age was 5.9 years (IQR, 2.7–10.3); 497 (48.5%) were female, 567 (55.4%) were non-Hispanic Black, 212 (20.7%) were non-Hispanic White, and 175 (17.1%) were Hispanic (Table 1). The most common underlying comorbidities were respiratory disorders including asthma/reactive airway disease (463, 45.2%). Fever was the most common presenting symptom (832, 81.3%); 677 (66.1%) reported more than 3 symptoms, and the median duration of symptoms at presentation was 3 days (IQR, 2–6). The median length of stay was 4 days (IQR, 3–5); 228 (22.3%) patients had a radiographic diagnosis of pneumonia, 340 (33.2%) were admitted to the ICU, and 67 (6.5%) required mechanical ventilation. Influenza A was predominant in all seasons; 370 of 512 (72.3%) tested positive for influenza A, and 143 of 512 (27.9%) tested positive for influenza B (1 case was coinfected with influenza A and B). There were no differences in age, sex, or ethnicity among influenza-positive and influenza-negative patients. Children who tested positive for influenza were less likely to have been born prematurely (among those aged <2 years; 14.6% vs 29.7%; P = .011), more likely to present with fever (91.4% vs 71.1%, P < .001), and have shorter hospital stay (median of 3 days [IQR, 3–5] vs 4 days [IQR, 3–6], P < .001) compared with those who tested negative for influenza (Table 1). Oseltamivir use was more common (87.3% vs 1.0%, P < .001) and ICU admission was less likely (27.1% vs 39.3%, P < .001) among children with influenza.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram for study enrollment (see Supplementary Materials for additional details). ARI defined as the presence of ≥1 of the following symptoms: nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, sore throat, hoarseness, cough, sputum production, dyspnea, wheezing; an admitting diagnosis suggestive of ARI (pneumonia, upper respiratory infection, bronchitis, lower respiratory infection, bronchiolitis, influenza, cough, asthma, viral illness, respiratory distress, respiratory failure); or congestive heart failure exacerbation. Abbreviation: ARI, acute respiratory illness.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Study Participants by Case Status

| Cases vs Controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total (N = 1024) | Cases (N = 512) | Controls (N = 512) | P Valuea | |

| Demographics | |||||

| Hospital | Hospital 1 | 523 (51.1) | 252 (49.2) | 271 (52.9) | .260 |

| Hospital 2 | 501 (48.9) | 260 (50.8) | 241 (47.1) | ||

| Age at presentation, y | Median | 5.9 | 5.8 | 6 | .981 |

| IQR | 2.7–10.3 | 2.7–10.2 | 2.6–10.4 | ||

| Age group, y | 0 to <5 | 438 (42.8) | 219 (42.8) | 219 (42.8) | .945 |

| 5 to <9 | 272 (26.6) | 138 (27.0) | 134 (26.2) | ||

| 9+ | 314 (30.7) | 155 (30.3) | 159 (31.1) | ||

| Sex | Female | 497 (48.5) | 242 (47.3) | 255 (49.8) | .453 |

| Male | 527 (51.5) | 270 (52.7) | 257 (50.2) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | Hispanic | 175 (17.1) | 92 (18.0) | 83 (16.2) | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 567 (55.4) | 311 (60.7) | 256 (50.0) | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 212 (20.7) | 78 (15.2) | 134 (26.2) | ||

| Otherb | 70 (6.8) | 31 (6.1) | 39 (7.6) | ||

| Season | 2012–2013 | 266 (26.0) | 133 (26.0) | 133 (26.0) | >.999 |

| 2013–2014 | 118 (11.5) | 59 (11.5) | 59 (11.5) | ||

| 2014–2015 | 252 (24.6) | 126 (24.6) | 126 (24.6) | ||

| 2015–2016 | 148 (14.5) | 74 (14.5) | 74 (14.5) | ||

| 2016–2017 | 240 (23.4) | 120 (23.4) | 120 (23.4) | ||

| Vaccination | |||||

| Type | Inactivated influenza vaccine | 347 (33.9) | 137 (26.8) | 210 (41.0) | <.001 |

| Live attenuated influenza vaccine | 23 (2.2) | 12 (2.3) | 11 (2.1) | ||

| None | 654 (63.9) | 363 (70.9) | 291 (56.8) | ||

| Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices vaccination status | Complete | 145 (14.2) | 54 (10.5) | 91 (17.8) | <.001 |

| Partial | 225 (22.0) | 95 (18.6) | 130 (25.4) | ||

| None | 654 (63.9) | 363 (70.9) | 291 (56.8) | ||

| Medical history | |||||

| Blood disorder | Yes | 169 (16.5) | 94 (18.4) | 75 (14.6) | .130 |

| Cardiac disorder | Yes | 85 (8.3) | 34 (6.6) | 51 (10.0) | .069 |

| Endocrine disorder | Yes | 31 (3.0) | 14 (2.7) | 17 (3.3) | .716 |

| Immunocompromised | Yes | 134 (13.1) | 69 (13.5) | 65 (12.7) | .781 |

| Kidney disorder | Yes | 29 (2.8) | 17 (3.3) | 12 (2.3) | .452 |

| Liver disorder | Yes | 19 (1.9) | 11 (2.1) | 8 (1.6) | .644 |

| Hematologic malignancy | Yes | 31 (3.0) | 14 (2.7) | 17 (3.3) | .716 |

| Solid organ malignancy | Yes | 21 (2.1) | 6 (1.2) | 15 (2.9) | .075 |

| Metabolic disorder | Yes | 16 (1.6) | 6 (1.2) | 10 (2.0) | .451 |

| Neurologic disorder | Yes | 243 (23.7) | 111 (21.7) | 132 (25.8) | .142 |

| Prematurityc | Yes | 45 (22.1) | 15 (14.6) | 30 (29.7) | .011 |

| Respiratory disorder | Yes | 463 (45.2) | 216 (42.2) | 247 (48.2) | .060 |

| Rheumatologic disorder | Yes | 7 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) | 6 (1.2) | .124 |

| Any medical history | Yes | 788 (77.0) | 393 (76.8) | 395 (77.1) | .941 |

| Clinical presentation | |||||

| Body mass index | Median | 16.6 | 16.8 | 16.5 | .168 |

| IQR | 15.0–19.4 | 15.1–19.4 | 14.8–19.5 | ||

| Days from vaccination to symptom onset | Median | 85 | 86 | 84 | .658 |

| IQR | 54.0–125.0 | 56.0–132.0 | 53.0–124.0 | ||

| Days of symptoms | Median | 3 | 3 | 3 | .496 |

| IQR | 2.0–6.0 | 2.0–6.0 | 2.0–6.0 | ||

| Fever | Yes | 832 (81.3) | 468 (91.4) | 364 (71.1) | <.001 |

| Days of feverd | Median | 2 | 2 | 2 | .880 |

| IQR | 1.0–4.0 | 1.0–4.0 | 1.0–4.0 | ||

| Highest recorded temperature (ºC)d | Median | 39 | 39.1 | 38.9 | .002 |

| IQR | 38.3–39.6 | 38.6–39.6 | 38.2–39.5 | ||

| >3 symptomse | Yes | 677 (66.1) | 349 (68.2) | 328 (64.1) | .187 |

| Microbiologyf | |||||

| Influenza A | Positive | 370 (36.1) | 370 (72.3) | 0 (0.0) | <.001 |

| Influenza B | Positive | 143 (14.0) | 143 (27.9) | 0 (0.0) | <.001 |

| Human metapneumovirus | Positive | 58 (5.7) | 5 (1.0) | 53 (10.4) | <.001 |

| Adenovirus | Positive | 20 (2.0) | 6 (1.2) | 14 (2.7) | .112 |

| Chlamydophila pneumoniae | Positive | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | >.999 |

| Coronavirus Coronavirus 229E | Positive | 7 (1.1) | 4 (1.2) | 3 (0.9) | >.999 |

| Coronavirus HKU1 | Positive | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | >.999 |

| Coronavirus NL63 | Positive | 17 (1.7) | 3 (0.6) | 14 (2.7) | .012 |

| Coronavirus OC43 | Positive | 15 (2.3) | 4 (1.2) | 11 (3.4) | .114 |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | Positive | 6 (0.8) | 2 (0.5) | 4 (1.1) | .686 |

| Parainfluenza 1 | Positive | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | .500 |

| Parainfluenza 2 | Positive | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | .500 |

| Parainfluenza 3 | Positive | 6 (0.6) | 3 (0.6) | 3 (0.6) | >.999 |

| Parainfluenza 4 | Positive | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.6) | .249 |

| Rhinovirus/Enterovirus | Positive | 168 (16.4) | 25 (4.9) | 143 (27.9) | <.001 |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | Positive | 99 (9.7) | 15 (2.9) | 84 (16.4) | <.001 |

| Antiviral use while hospitalized | |||||

| Oseltamivir | Yes | 452 (44.1) | 447 (87.3) | 5 (1.0) | <.001 |

| Days of treatmentg | Median | 6 | 6 | 1 | <.001 |

| IQR | 5.0–6.0 | 5.0–6.0 | 1.0–1.0 | ||

| Outcome | |||||

| Days of hospitalization | Median | 4 | 3 | 4 | <.001 |

| IQR | 3–5 | 3–5 | 3–6 | ||

| Intensive care unit admission | Yes | 340 (33.2) | 139 (27.1) | 201 (39.3) | <.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | Yes | 67 (6.5) | 28 (5.5) | 39 (7.6) | .206 |

| Radiographic pneumoniah | Yes | 228 (22.3) | 123 (24.0) | 105 (20.5) | .202 |

Abbreviations: HMPV, human metapneumovirus; IQR, interquartile range.

aCases and controls compared using the Fisher exact test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables.

bOther races included American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, multiple races, and unknown.

cPrematurity history unavailable for participants aged >2 years at admission.

dDays of fever and maximum temperature only defined for participants with fever.

eParticipants may be missing data for 1 or multiple symptoms.

fMicrobiology notes: One case coinfected with influenza A and B. A total of 101 participants were positive for multiple pathogens, with a maximum of 3 pathogens identified. Coronavirus Coronavirus 229E, coronavirus HKU1, and coronavirus OC43 results were missing in 378 participants (189 cases, 189 controls). Chlamydophila pneumoniae results were missing in 375 participants (187 cases, 188 controls), and Mycoplasma pneumoniae results were missing in 265 participants (133 cases, 132 controls).

gDays of treatment only defined for participants who received treatment.

hRadiographic pneumonia identified by presence of International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification, code.

The majority of the children included in the final analyses were not vaccinated against influenza during the enrollment season (654, 63.9%); 23 children (2.2%) received LAIV, and 347 (33.9%) received IIV (Table 1). Children who were vaccinated did not differ in age, sex, ethnicity, or body mass index from those who were unvaccinated for the enrollment season (Supplementary Table 2B). Vaccination rates with IIV were similar between the seasons (P = .27), whereas LAIV coverage differed by season (P = .01). Those who received IIV had more concomitant medical comorbidities (85.3% vs 74.0%, P < .001), whereas those who received LAIV were less likely to have a concomitant comorbidity (34.8% vs 74.0%, P < .001) than those who were unvaccinated. Children who were vaccinated with IIV were less likely to have radiologically confirmed pneumonia (17.9% vs 23.7%, P = .036) or ICU admission (26.2% vs 36.7%, P < .001) compared with those who were unvaccinated.

Vaccine Effectiveness

Among the 490 cases and 490 controls used to estimate IIV effectiveness, 132 (26.9%) of influenza-positive cases and 209 (42.7%) of influenza-negative controls were vaccinated with seasonal IIV. The adjusted VE of IIV against influenza-related pediatric hospitalizations from 2012–2017 was 51.3% (95% CI, 34.8% to 63.6%; Table 2). The adjusted influenza VE was 54.7% (95% CI, 37.4% to 67.3%) for influenza A and 37.1% (95% CI, 2.3% to 59.5%) for influenza B. Due to few cases of influenza among those who received LAIV, VE was not determined for LAIV.

Table 2.

Inactivated Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Against Hospitalization Among Children Aged 6 Months to 17 Years, 2012–2013 to 2016–2017

| Estimated Vaccine Effectiveness, a % (95% Confidence Interval)) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inactivated Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness by Characteristic | Cases Who Were Vaccinated, No./Total No. (%) | Controls Who Were Vaccinated, No./Total No. (%) | Unadjusted | Adjustedb |

| Overall | 132/490 (26.9) | 209/490 (42.7) | 50.4 (35.2 to 62.1) | 51.3 (34.8 to 63.6) |

| Influenza B–infected casesc | 43/139 (30.9) | 209/490 (42.7) | 39.8 (10.0 to 59.7) | 37.1 (2.3 to 59.5) |

| Influenza A–infected casesc | 89/352 (25.3) | 209/490 (42.7) | 54.5 (38.6 to 66.3) | 54.7 (37.4 to 67.3) |

| By age group, y | ||||

| 0 to <5 | 49/214 (22.9) | 98/214 (45.8) | 64.8 (46.7 to 76.8) | 64.3 (44.1 to 77.1) |

| 5 to <9 | 42/127 (33.1) | 47/122 (38.5) | 21.2 (–32.5 to 53.1) | 17.1 (–44.6 to 52.5) |

| 9+ | 41/149 (27.5) | 64/154 (41.6) | 46.6 (13.6 to 67.0) | 52.2 (19.5 to 71.6) |

| By season | ||||

| 2012–2013 | 39/128 (30.5) | 43/128 (33.6) | 13.4 (–46.5 to 48.8) | 12.0 (–54.4 to 49.9) |

| 2013–2014 | 7/56 (12.5) | 26/56 (46.4) | 83.5 (57.4 to 93.6) | 83.6 (55.3 to 94.0) |

| 2014–2015 | 29/116 (25.0) | 52/116 (44.8) | 59.0 (28.4 to 76.5) | 62.3 (31.9 to 79.1) |

| 2015–2016 | 18/70 (25.7) | 41/70 (58.6) | 75.5 (49.9 to 88.0) | 74.4 (45.4 to 88.0) |

| 2016–2017 | 39/120 (32.5) | 47/120 (39.2) | 25.2 (–27.0 to 56.0) | 24.4 (–33.6 to 57.1) |

| Immunocompromised | ||||

| Yes | 31/67 (46.3) | 43/63 (68.3) | 59.9 (18.1 to 80.4) | 43.5 (–23.3 to 74.1) |

| No | 101/423 (23.9) | 166/427 (38.9) | 50.7 (33.7 to 63.3) | 52.4 (34.9 to 65.2) |

| Cases and controls admitted to the intensive care unit | 26/134 (19.4) | 65/192 (33.9) | 53.0 (20.7 to 72.1) | 51.3 (14.7 to 72.1) |

| Cases and controls with radiographic pneumoniad | 22/114 (19.3) | 39/97 (40.2) | 64.4 (34.1 to 80.8) | 65.5 (32.3 to 82.4) |

| Time of the season | ||||

| Early | 61/245 (24.9) | 109/252 (43.3) | 56.5 (36.3 to 70.3) | 58.1 (36.8 to 72.2) |

| Late | 71/245 (29.0) | 100/238 (42.0) | 43.7 (17.9 to 61.4) | 43.4 (15.1 to 62.3) |

| Cases and controls hospitalized during peak influenza circulatione | 130/465 (28.0) | 194/446 (43.5) | 49.6 (33.6 to 61.7) | 50.6 (33.4 to 63.4) |

aCalculated as (1 – odds ratio [OR]) × 100%, where OR is the odds of vaccination among cases compared with the odds of vaccination among controls.

bAdjusted for demographic characteristics (age at admission in years, sex, race/ethnicity, study hospital, and season), neurologic disorder, and chronic conditions with significant bivariate associations with vaccination or case status as identified in Table 1 (blood disorder, cardiac disorder, immunocompromised status, kidney disorder, hematologic malignancy, solid organ malignancy, and respiratory disorder).

cOne case coinfected with influenza A and B included in both subgroups.

dDefined by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, codes before October 2015 and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification, codes beginning in October 2015.

ePeriod within each season when >4% of all sampling was positive.

Sensitivity Analyses

Restricting cases to those negative for all noninfluenza viruses did not substantially change VE estimates, nor did restricting cases and controls to those hospitalized during peak influenza circulation (Table 2) Considering only complete vaccinations per the ACIP, VE was estimated at 55.3% (95% CI, 31.7% to 70.7%); VE was similar for partial vaccinations at 46.8% (95% CI, 23.8% to 62.8%). Among cases and controls hospitalized within 3 days of symptom onset, VE was 39.7% (95% CI, 8.9% to 60.1%). When we restricted our analysis to those who were admitted to the ICU and those who had radiographically confirmed pneumonia, the overall adjusted influenza VE was 51.3% (95% CI, 14.7% to 72.1%) and 65.5% (95% CI, 32.3% to 82.4%), respectively. Influenza vaccination was not effective in preventing HMPV-related hospitalizations in influenza-negative children (7.6%; 95% CI, –23.5% to 30.9%).

Subgroup Analyses

Influenza VE varied by season and was highest in the 2013–2014 season (83.6%; 95% CI, 55.3% to 94.0%) and lowest in the 2012–2013 season (12.0%; 95% CI, –54.4% to 49.9%; Table 3). VE point estimates tended to be higher in children aged <5 years (64.3%; 95% CI, 44.1% to 77.1%) and lower in children aged 5–9 years (17.1%; 95% CI, –44.6% to 52.5%), but were imprecise, especially in the older age group owing to small numbers. A post hoc analysis of VE in children aged <9 years was 50.7% (30.1% to 65.2%). Estimates of VE differed by clinical presentation (P = .027) and were similar for children who presented with ARI and fever with cough or without cough (57.7%; 95% CI, 36.9% to 71.6% vs 70.6; 95% CI, 37.6% to 86.2%, respectively). There was not a significant difference between the VE estimates in patients with vs without immunocompromising comorbidities (43.5%; 95% CI, –23.3% to 74.1% vs 52.4%; 95% CI, 34.9% to 65.2%). Influenza VE did not differ substantially by the time of diagnosis within the season (early season: 58.1%; 95% CI, 36.8% to 72.2%; late season: 43.4%; 95% CI, 15.1% to 62.3%). The impact of prior seasonal IIV on VE estimates could not be determined due to insufficient numbers.

Table 3.

Sensitivity Analyses of Vaccine Effectiveness of Inactivated Influenza Vaccine

| Estimated Vaccine Effectiveness,a % (95% Confidence Interval) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity Analysis of Vaccine Effectiveness by Definition | Cases Who Were Vaccinated, No./Total No. (%) | Controls Who Were Vaccinated, No./Total No. (%) | Unadjusted | Adjustedb |

| Complete vaccination per ACIP | 51/409 (12.5) | 87/368 (23.6) | 54.0 (32.8 to 68.5) | 55.3 (31.7 to 70.7) |

| Partial vaccination per ACIP | 81/439 (18.5) | 122/403 (30.3) | 47.9 (28.1 to 62.2) | 46.8 (23.8 to 62.8) |

| Cases and controls hospitalized during peak influenza circulationc | 130/465 (28.0) | 194/446 (43.5) | 49.6 (33.6 to 61.7) | 50.6 (33.4 to 63.4) |

| Cases and controls hospitalized ≤3 days after symptom onset | 85/255 (33.3) | 97/227 (42.7) | 33.0 (3.0 to 53.7) | 39.7 (8.9 to 60.1) |

Abbreviation: ACIP, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

aCalculated as (1 – odds ratio [OR]) × 100%, where OR is the odds of vaccination among cases compared with the odds of vaccination among controls.

bAdjusted for demographic characteristics (age at admission, sex, race/ethnicity, study hospital, and season), neurologic disorder, and chronic conditions with significant bivariate associations with vaccination or case status as identified in Table 1 (blood disorder, cardiac disorder, immunocompromised status, kidney disorder, hematologic malignancy, solid organ malignancy, and respiratory disorder).

cPeriod within each season when >4% of all sampling was positive.

DISCUSSION

We estimated that IIV effectiveness against influenza-related hospitalizations among children was 51.3% (95% CI, 34.8% to 63.6%) and varied by season. Our findings are consistent with previously reported estimates of VE against influenza-related hospitalizations. The New Vaccine Surveillance Network recently estimated influenza VE against pediatric influenza-associated hospitalizations as 41% (95% CI, 20% to 56%) during the 2018–2019 flu season [22]. Our findings are also similar to those from Chung et al who reported VE as 51% (95% CI, 44% to 57%) against medically attended outpatient acute respiratory infections in children for the 2015–2018 influenza seasons, with a slightly lower point estimate in partially vaccinated children at 41% (95% CI, 25% to 54%) [17]. These data contrast with those from a recent study that found no protection against influenza-related hospitalizations in partially vaccinated children between 2015 and 2018 [18]. Similar to other studies, those with comorbidities were more likely to receive the influenza vaccine, possibly related to more frequent healthcare encounters resulting in increased opportunities for vaccination [14, 23, 24].

Influenza VE can be impacted by many factors such as receipt of prior seasonal influenza vaccinations, timing of influenza vaccination relative to the onset of disease, age, comorbidities, and antigenic match between the vaccine strain and antigenically drifted circulating influenza strains [25-27]. We did not find clear evidence of intraseason waning of vaccine effectiveness, although there may have been a tendency for VE to be lower late in the season. Multiple studies have examined the impact of timing of influenza vaccination during the season on VE, as studies have suggested the possibility of intraseason waning of influenza VE [3-7]. In addition, our sample size was not large enough to determine the impact of IIV administration in the prior season on the current season’s VE. There has been increasing interest in the association of prior vaccination with subsequent VE, although studies have found variable results thus far [26, 28, 29].

We found substantial variability in influenza VE by season and age group. Overall seasonal influenza VE from 2012 to 2017 ranged from 12.0% to 83.6%, but the individual season point estimates should be interpreted with caution due to the large confidence intervals. Notably, our point estimates of influenza VE were highest in 2 H1N1 predominant seasons (2013–2014, 2015–2016). As the composition of the influenza vaccine is determined far in advance, changes in the circulating viruses due to antigenic drift or mismatches to the circulating viruses can influence VE for that particular season [30, 31]. We also saw marked seasonal variability, although the reasons for such differences are uncertain. Age-related differences and contributing factors to these differences for vaccine-induced protection among children are not well understood [32]. Host factors such as prevalence and types of underlying comorbidities in different age groups can impact the vaccine-induced protection and needs further study.

Importantly, we also identified evidence for protection of influenza vaccination against influenza-related ICU admission and pneumonia. These findings suggest the potential for influenza vaccination to attenuate influenza disease severity in children. Similar findings have been observed in some studies of adults in the FluSurv-NET surveillance network that showed, in some seasons, that adults who received influenza vaccine had reduced ICU length of stay (LOS), hospital LOS, and decreased risk of pneumonia and death [11, 12]. In another study, it was found that influenza vaccination protected against influenza-related ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, and deaths in adults aged ≥65 years [15]. It is possible that residual unidentified confounders could have contributed to our findings, but we think this less likely as children are generally less medically complex than adults. In our study, we were unable to analyze the potential impact of influenza vaccination on mechanical ventilation and death in children due to low numbers. We also could not identify influenza VE in immunocompromised children, although this may have been due to insufficient power to detect a difference [14]. Additional data are needed to confirm these findings.

Importantly, we also used HMPV controls to assess for potential unrecognized confounding. Our choice of HPMV rather than a different respiratory virus (eg, respiratory syncytial virus) was due to the closer correlation of the age distribution of HMPV and influenza admissions. A large number of HMPV cases provided substantial power to identify any such confounding and has been used previously [14]. Importantly, we observed no influenza VE against HMPV admissions, which suggests against confounding in our influenza VE estimates (eg, by testing biases that might exist due to knowledge of influenza vaccination status).

Limitations of our study include the inherent limitations of test-negative study designs, such as our lack of ability to control the extent of exposure for cases and controls. However, we selected our cases and controls from the same source population, and our controls were selected independently from their influenza vaccination status. Potential vaccine-status misclassifications due to lack of reporting into GRITS could have resulted in bias in our estimates toward the null. In addition, the multiplex respiratory molecular panel may not have the sensitivity or specificity of dedicated molecular testing, resulting in underestimating VE. As this was a single-center study, we were unable to assess the impact of influenza vaccination on mortality due to its rare occurrence, although it has been reported that up to 80% of pediatric deaths occur in unvaccinated children [33]. Due to the small number of children who received LAIV, we were also unable to determine LAIV VE. This study was retrospective in design and, despite our efforts, may have had unidentified testing biases. We found that although the majority of influenza-positive cases received oseltamivir, it was usually started at or after the time of ICU admission. Thus, influenza antivirals had less potential to impact outcomes compared with other studies in which improved outcomes with early initiation of oseltamivir were observed [34]. Although our study included a large number of cases and controls, the subgroups consisted of smaller numbers of children, which could have resulted in detection of spuriously significant events in the sensitivity and subgroup analyses or missing outcomes for which it may be underpowered to detect.

In conclusion, influenza vaccination provides significant protection against pediatric hospitalization, including potential ICU admission and pneumonia. Benefit was also observed in partially vaccinated children. Our data support annual influenza vaccination recommendations for all children without a known contraindication.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank the Emory Vaccine Treatment and Evaluation Unit (VTEU) administrative and finance core for their support, including Nadine Rouphael, Dean Kleinhenz, Hannah Huston, and Michele Paine McCullough. The authors are grateful for the support of Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, including Drs Robert Jerris and Mark Gonzalez, and the Center for Childhood Immunizations and Vaccines. They also thank Melinda Tibbals, Michael Cooper, and Chris Roberts from the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

Financial support. This work was supported by awards from the Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, NIAID, at the National Institutes of Health to the Emory Vaccine and Treatment Evaluation Unit (contract HHSN272201300018I). We also acknowledge the REDCap support for this project provided by UL1 TR000424.

Potential conflicts of interest. E. J. A. has received personal fees from AbbVie, Pfizer, and Sanofi Pasteur for consulting; serves on a safety monitoring board for Sanofi and Kentucky BioProcessing, Inc; and his institution receives funds to conduct clinical research unrelated to the research presented here from MedImmune, Regeneron, PaxVax, Pfizer, GSK, Merck, Novavax, Sanofi-Pasteur, Janssen, and Micron. C. A. R. has received royalties to Emory University from Meissa Vaccines, Inc; reports clinical trials research funding from BioFire, MedImmune, PaxVax, Micron, Janssen, and Pfizer outside the submitted work; and is co-inventor of a pending patent (US20180333477A1) for respiratory syncytial virus vaccine technology that incorporates stabilized prefusion F protein, licensed to Meissa Vaccines, Inc, with royalties paid to Emory University. B. L. reports grants and advisory board service from Takeda Pharmaceuticals and personal fees from the World Health Organization outside the submitted work. All remaining authors: No reported conflicts of interest.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. Influenza-associated hospitalizations in the United States. JAMA 2004; 292:1333-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grohskopf LA, Alyanak E, Broder KR, Walter EB, Fry AM, Jernigan DB. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices—United States, 2019-20 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep 2019; 68: 1-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Belongia EA, Sundaram ME, McClure DL, Meece JK, Ferdinands J, VanWormer JJ. Waning vaccine protection against influenza A (H3N2) illness in children and older adults during a single season. Vaccine 2015; 33:246-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferdinands JM, Fry AM, Reynolds S, et al. Intraseason waning of influenza vaccine protection: evidence from the US Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network, 2011-12 through 2014-15. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64:544-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Petrie JG, Ohmit SE, Truscon R, et al. Modest waning of influenza vaccine efficacy and antibody titers during the 2007-2008 influenza season. J Infect Dis 2016; 214: 1142-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Castilla J, Martinez-Baz I, Martinez-Artola V, et al. Decline in influenza vaccine effectiveness with time after vaccination, Navarre, Spain, season 2011/12. Euro Surveill 2013; 18:20388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pebody R, Andrews N, McMenamin J, et al. Vaccine effectiveness of 2011/12 trivalent seasonal influenza vaccine in preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza in primary care in the United Kingdom: evidence of waning intra-seasonal protection. Euro Surveill 2013; 18:20389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caspard H, Gaglani M, Clipper L, et al. Effectiveness of live attenuated influenza vaccine and inactivated influenza vaccine in children 2-17 years of age in 2013-2014 in the United States. Vaccine 2016; 34: 77-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caspard H, Mallory RM, Yu J, Ambrose CS. Live-attenuated influenza vaccine effectiveness in children from 2009 to 2015-2016: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017; 4: ofx111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chung JR, Flannery B, Thompson MG, et al. Seasonal effectiveness of live attenuated and inactivated influenza vaccine. Pediatrics 2016; 137:e20153279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arriola C, Garg S, Anderson EJ, et al. Influenza vaccination modifies disease severity among community-dwelling adults hospitalized with influenza. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:1289–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Garg S, O’Halloran A, Cummings CN, et al. Age-related differences in influenza type/subtype among patients hospitalized with influenza, FluSurv-NET—2017–2018. IDWeek. San Francisco, CA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ferdinands JM, Gaglani M, Martin ET, et al. Prevention of influenza hospitalization among adults in the United States, 2015-2016: results from the US Hospitalized Adult Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (HAIVEN). J Infect Dis 2019; 220: 1265-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grijalva CG, Zhu Y, Williams DJ, et al. Association between hospitalization with community-acquired laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia and prior receipt of influenza vaccination. JAMA 2015; 314:1488-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nichols MK, Andrew MK, Hatchette TF, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness to prevent influenza-related hospitalizations and serious outcomes in Canadian adults over the 2011/12 through 2013/14 influenza seasons: a pooled analysis from the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) Serious Outcomes Surveillance (SOS Network). Vaccine 2018; 36: 2166-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Campbell AP, Ogekeh EC, McGowan C, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against laboratory-confirmed influenza in children hospitalized with respiratory illness in the United States, 2016–2017 and 2017–2018 seasons. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6: S26-S7. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chung JR, Flannery B, Gaglani M, et al. Patterns of influenza vaccination and vaccine effectiveness among young US children who receive outpatient care for acute respiratory tract illness. JAMA Pediatr 2020; 174:705-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Segaloff HE, Leventer-Roberts M, Riesel D, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization in fully and partially vaccinated children in Israel: 2015-2016, 2016-2017, and 2017-2018. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69: 2153-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42:377-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cortese MM, Leblanc J, White KE, et al. Leveraging state immunization information systems to measure the effectiveness of rotavirus vaccine. Pediatrics 2011; 128:e1474-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kuo CL, Duan Y, Grady J. Unconditional or conditional logistic regression model for age-matched case-control data? Front Public Health 2018; 6:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Campbell AP, Ogokeh C, Lively JY, et al. Vaccine effectiveness against pediatric influenza hospitalizations and emergency visits. Pediatrics 2020; 146:e20201368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Collins JP, Campbell AP, Openo K, et al. Outcomes of immunocompromised adults hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza in the United States, 2011-2015. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 70:2121-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Collins JP, Campbell AP, Openo K, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of immunocompromised children hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed influenza in the United States, 2011-2015. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2019; 8:539-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lewnard JA, Cobey S. Immune history and influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccines (Basel) 2018; 6:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McLean HQ, Caspard H, Griffin MR, et al. Association of prior vaccination with influenza vaccine effectiveness in children receiving live attenuated or inactivated vaccine. JAMA Netw Open 2018; 1:e183742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ray GT, Lewis N, Klein NP, et al. Intraseason waning of influenza vaccine effectiveness. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 68:1623-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Belongia EA, Skowronski DM, McLean HQ, Chambers C, Sundaram ME, De Serres G. Repeated annual influenza vaccination and vaccine effectiveness: review of evidence. Expert Rev Vaccines 2017; 16:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Skowronski DM, Chambers C, De Serres G, et al. Serial vaccination and the antigenic distance hypothesis: effects on influenza vaccine effectiveness during A(H3N2) epidemics in Canada, 2010-2011 to 2014-2015. J Infect Dis 2017; 215: 1059-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kelly HA, Sullivan SG, Grant KA, Fielding JE. Moderate influenza vaccine effectiveness with variable effectiveness by match between circulating and vaccine strains in Australian adults aged 20-64 years, 2007-2011. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2013; 7: 729-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Skowronski DM, Janjua NZ, De Serres G, et al. Low 2012-13 influenza vaccine effectiveness associated with mutation in the egg-adapted H3N2 vaccine strain not antigenic drift in circulating viruses. PLoS One 2014; 9:e92153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. McLean HQ, Thompson MG, Sundaram ME, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in the United States during 2012-2013: variable protection by age and virus type. J Infect Dis 2015; 211: 1529-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Flannery B, Reynolds SB, Blanton L, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against pediatric deaths: 2010-2014. Pediatrics 2017; 139:e20164244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lytras T, Mouratidou E, Andreopoulou A, Bonovas S, Tsiodras S. Effect of early oseltamivir treatment on mortality in critically ill patients with different types of influenza: a multiseason cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2019; 69:1896-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.